Adam Thierer's Blog, page 23

September 10, 2018

Is Facebook Now Over-moderating Content?

Reading professor Siva Vaidhyanathan’s recent op-ed in the New York Times, one could reasonably assume that Facebook is now seriously tackling the enormous problem of dangerous information. In detailing his takeaways from a recent hearing with Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, Vaidhyanathan explained,

Ms. Sandberg wants us to see this as success. A number so large must mean Facebook is doing something right. Facebook’s machines are determining patterns of origin and content among these pages and quickly quashing them.

Still, we judge exterminators not by the number of roaches they kill, but by the number that survive. If 3 percent of 2.2 billion active users are fake at any time, that’s still 66 million sources of potentially false or dangerous information.

One thing is clear about this arms race: It is an absurd battle of machine against machine. One set of machines create the fake accounts. Another deletes them. This happens millions of times every month. No group of human beings has the time to create millions, let alone billions, of accounts on Facebook by hand. People have been running computer scripts to automate the registration process. That means Facebook’s machines detect the fakes rather easily. (Facebook says that fewer than 1.5 percent of the fakes were identified by users.)

But it could be that, in their zeal to trapple down criticism from all sides, Facebook instead has corrected too far and is now over-moderating. The fundamental problem is that it is nearly impossible to know the true amount of disinformation on a platform. For one, there is little agreement on what kind of content needs to be policed. It is doubtful everyone would agree what constitutes fake news and separates it from disinformation or propaganda and how all of that differs from hate speech. But more fundamentally, even if everyone agreed to what should be taken down, it is still not clear that algorithmic filtering methods would be able to perfectly approximate that.

Detecting content that violates a hate speech code or a disinformation standard leads into a massive operationalization problem. A company like Facebook isn’t going to be perfect. It could produce a detection regime that was either underbroad or overbroad. It is of course only minimal evidence, but I have been seeing a lot of my friends on Facebook post about how their own posts have been taken down and it was clear they were non-political.

Over-moderation could explain why many conservatives have been worried about Twitter and Facebook engaging in soft censorship. Paula Bolyard made a convincing case in the Washington Post,

There have been plenty of credible reports over the past two years claiming anti-conservative bias at the Big Three Internet platforms, including the 2016 revelation that Facebook had routinely suppressed conservative outlets in the network’s “trending” news section. Further, when Alphabet-owned YouTube pulls down and demonetizes mainstream conservative content from sites such as PragerU, it certainly gives the impression that the company has its thumb on the scale.

Bolyard hints at one of the biggest problems in the conversation today. Users cannot peer behind the veil and are thus forced to impute intentions about how the network operates in practice. Here is how Sarah Myers West, a postdoc researcher at the AI Now Institute, described the process,

Many social network users develop “folk theories” about how platforms work: in the absence of authoritative explanations, they strive to make sense of content moderation processes by drawing connections between related phenomena, developing non-authoritative conceptions of why and how their content was removed

West goes on to cite a study of moderation efforts, which found that users thought Facebook was “powerful, perceptive, and ultimately unknowable.” Both Vaidhyanathan and Bolyard could pushing similar folk theories. They are both astute in their comments and offer a lot to consider, but everyone in this discussion, including the operators at Facebook and Twitter, is hobbled by a fundamental knowledge problem.

Still, each platform has to create its own means of detecting this content, which will need to conform to the specifics of the platform. Evelyn Douek’s report on the Senate Hearing, which you should absolutely go read, helps to fill out some of the details on this point,

[Twitter CEO Jack] Dorsey stated that Twitter does not focus on whether political content originates abroad in determining how to treat it. Because Twitter, unlike Facebook, has no “real name” policy, Twitter cannot prioritize authenticity. Dorsey instead described Twitter as focusing on the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to detect “behavioural patterns” that suggest coordination between accounts or gaming the system. In a sense, this is also a proxy for a lack of authenticity, but on a systematic rather than an individual scale. Twitter’s focus, according to Dorsey, is on how people game the system in the “shared spaces [on Twitter] where anyone can interject themselves,” rather than the characteristics of profiles that users choose to follow.

Dorsey seems to set up a comparison between the two companies. Facebook’s method of detecting nefarious content deals with the profile, as an authenticated person, in relation to the content that is shared. Twitter, on the other hand, is looking for people to game the system in the “shared spaces [on Twitter] where anyone can interject themselves.” It might be a misread, but Dorsey suggests that Twitter is emphasizing the actions of users, which would lead to a more structural approach.

It goes without saying that Facebook’s social network is different from Twitter’s, leading to different approaches in moderation. Facebook creates dyadic connections. The relationships on Facebook run both ways. Becoming friends means we are in a mutual relationship. Twitter, however, allows for people to follow others without reciprocity. The result are distinct network structures. Pew, for example, was able to distinguish between six different broad structures, including polarized crowds, tight crowds, brand clusters, community clusters, broadcast networks, and support networks. Combined, these features make it difficult for both researchers and operators to understand the scope of the problem and how solutions are working, or not working.

So what are the broad incentives pushing platforms to either over-moderate or under-moderate content? Here is what I could come up with:

If content moderation is too broad, it will spark the ire of content creators who might get inadvertently caught up in a filter.

More content going over the network means more users and more engagement, and thus more advertising dollars, making the platform sensitive to over-moderation.

Content has both an extensive marginal and an intensive marginal. Facebook will want to expand the overall amount of content to attract people, but they will want to keep the content on the network high quality. Low quality will drive people and advertisers to exit, so they might have an incentive to over moderate.

Given the current political environment and the California privacy bill, it might make better long term sense to over-moderate or at least engage in the perception of over-moderation to reduce the chance of legal or regulatory pressures in the future.

The technical filtering solutions could have ambiguous effects on moderation. It could be that a platform simply is not that good at content moderation and has been under providing it.

Or, the filtering system could be providing an expansive program that has swept up too many people and too much content.

Given that people think these platforms are “powerful, perceptive, and ultimately unknowable,” the platforms might err on the side of under-moderation simply to reduce the overall experience of content moderation.

Content moderation at scale is difficult. And messy. In creating a technical regime to deal with this problem, we shouldn’t expect platforms to get it perfect. While many have criticized platforms for under-moderation, they might now being over-moderating. Still, there is a massive knowledge problem in trying to understand if the current level of moderation is optimal.

September 7, 2018

Deep Technologies & Moonshots: Should We Dare to Dream?

We hear a lot today about the importance of “disruptive innovation,” “deep technologies,” “moonshots,” and even “technological miracles.” What do these terms mean and how are they related? Are they just silly clichés used to hype techno-exuberant books, articles, and speeches? Or do these terms have real meaning and importance?

This article explores those questions and argues that, while these terms are confronted with definitional challenges and occasional overuse, they retain real importance to human flourishing, economic growth, and societal progress.

Basic Concepts

Don Boudreaux defines moonshots as, “radical but feasible solutions to important problems” and Mike Cushing has referred to them as “innovation that achieves the previously unthinkable.” “Deep technology” is another buzzword being used to describe such revolutionary and important innovations. Swati Chaturvedi of investment firm Propel[x] says deep technologies are innovations that are “built on tangible scientific discoveries or engineering innovations” and “are trying to solve big issues that really affect the world around them.”

“Disruptive technology” or “game-changing innovations” are other terms that are often used in reference to technologies and inventions with major societal impacts. “Transformative technologies” is another increasingly popular term, albeit one focused mostly on health and wellness-related innovations.

However one defines them and whatever one calls them, it is clear, as a 2015 report from the World Economic Forum (WEF) argued, that, “the list of potentially disruptive technologies keeps getting longer.” “Inventions previously seen only in science fiction,” the WEF report said, “will enable us to connect and invent in ways we never have before.”

More concretely, when people use these terms in reference to existing technologies, or ones currently on the drawing board, they often mention innovations like:

Artificial intelligence / machine learning / robotics

3D printing / additive manufacturing

Self-repairing / self-building objects

Driverless cars / flying cars (VTOL), supersonic transport

Private space travel / lunar mining

Clean power / alternative energy production

Genetic editing & life extension technologies

Implantable tech / human augmentation

Hyper-connected devices / wearable fitness / sensor tech / IoT

Precision medicine

Neural networks

Quantum computing

Nanotechnology / synthetic biology

Immersive technology (AT & VR)

This is just a partial list of the type of technologies that experts mention when discussing “moonshots,” deep tech,” and other “disruptive” or “transformative innovations.” What unifies them more than anything else is the potential for major improvements in human well-being. Significant advancements in these areas could lead to substantial jumps in human welfare, health, and longevity.

Definitional Limitations

These terms have some problems and limitations, however. For example,“moonshots” conjures up thoughts of large, expensive government programs that are centrally-directed in a top-down fashion. Writing in The New Atlantis last year, Mark P. Mills argued that the notion of “technological miracles” can be taken to unrealistic extremes and he specifically cautioned against getting caught up in “moonshot fallacies” as well as “Moore’s Law fallacy.”

The “moonshot fallacy” is commonly heard in policy discussions whenever a policymaker or pundit insists that, “If we can put a man on the moon, then we can…” fill in the blank with your prefered aspirational goal du jour. But as Mills points out, this sort of talk often represents highly unrealistic, wishful thinking. “It is true that engineers have achieved amazing feats when tasked with particular, practical goals. But not all goals are equally achievable,” he correctly argues.

“Moore’s Law fallacy” refers to the fact that innovation in the physical world of atoms is usually much harder and more costly than innovation in the digital world of bits. “If energy technology had followed a Moore’s Law trajectory, today’s car engine would have shrunk to the size of an ant while producing a thousandfold more horsepower,” Mills observes. The time horizons for big change are almost always going to be significantly longer in the physical world even with the increasing digitization in society and “software eating the world.”

“Disruptive technology” is also a problematic term because its common use is quite different from Clayton M. Christensen’s original explanation of the term in his widely-cited Harvard Business Review articles from 1995 and then 2015. “The original notion of disruption aimed to describe why great firms can fail,” Josh Gans explained in his recent book, The Disruption Dilemma. “Today, use of the term has gotten out of control,” he says. “As a concept, disruption has become so persuasive this it is at risk of becoming useless.”

Gans makes a good point. Not everything can be disruptive. Moreover, some techno-evangelists get carried away with such rhetoric regarding the “disruptive,” “transformative,” and “miracle”-working” potential of various technologies.

But Sometimes Dreams Come True

Despite these definitional controversies or rhetorical excesses from some overly-exuberant tech boosters, these terms retain real meaning and significance.

It is easy to ridicule dreamers, but quite a bit of life-changing innovation begins as a dream of some sort. Without a doubt, a great many “moonshots” will never get off the ground, and many “deep” technologies will end up sinking into the ocean of irrelevant or failed technologies. But that’s OK! It is in the process of risk-taking, experimentation, and failure that wisdom is generated and meaningful improvements in social and economic well-being come about.

It’s easy to talk about “trial-and-error” without thinking much about the “error” part of the process. It is only through constant experimentation and failure that we learn how to do things more efficiently and create or improve goods and services.

Perhaps the most straightforward definition of “technology” is Ian Barbour’s: “the application of organized knowledge to practical tasks by ordered systems of people and machines.” But organized knowledge requires lots of trials and lots of errors–by both people and machines–in order to find workable solutions to the tasks we hope to accomplish.

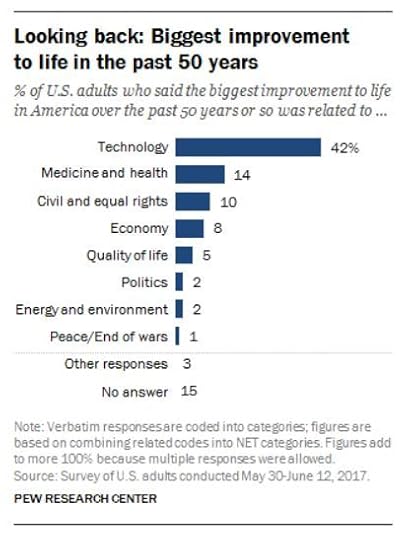

It would seem that most people appreciate how much technological innovation has improved their lives. A 2017 Pew Research Center poll asked, “What would you say was the biggest improvement to life in America over the past 50 years or so?” An overwhelming percentage of respondents (42%) said technology had contributed more than any other factor. That was three times as many people as the second-place answer, “medicine and health” (14%) (much of which could also be considered technological innovation). ”Politics” came in a distant 6th place with just 2% of respondents believing that it has changed life for the better.

It would seem that most people appreciate how much technological innovation has improved their lives. A 2017 Pew Research Center poll asked, “What would you say was the biggest improvement to life in America over the past 50 years or so?” An overwhelming percentage of respondents (42%) said technology had contributed more than any other factor. That was three times as many people as the second-place answer, “medicine and health” (14%) (much of which could also be considered technological innovation). ”Politics” came in a distant 6th place with just 2% of respondents believing that it has changed life for the better.

To the extent that we would like to see more technological improvements, we need more “dreamers” who hope to change the world. Entrepreneurs are the key to this process because, by their very nature, they refuse to settle for the status quo. They dream of a world that can work differently; one in which they can improve their own lot and (whether intentionally or not) improve the lot of humanity simultaneously. “What entrepreneurs do,” venture capitalist Vinod Khosla argues, “is they imagine what feels impossible to most people, and take it all the way from impossible, to improbable, to possible but unlikely, to plausible, to probable, to real!”

That is why entrepreneurialism is so important, and it is also why shouldn’t roll our eyes when people dream about “moonshots” and the ways in which “deep technology” might “disrupt” and “transform” society for the better.

While we should always keep both feet firmly rooted on the ground, there is nothing wrong with looking skyward and dreaming of a better future. Indeed, as a society, we should seek to foster a culture of innovation that rewards entrepreneurial dreaming and daring, because in seeking to make the world a better place, progress and prosperity become reality.

Additional Reading

Donald J. Boudreaux, “What’s Your Moonshot?” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Mercatus Original Video, November 16, 2017, https://www.mercatus.org/videos/whats-your-moonshot.

Joseph L. Bower & Clayton M. Christensen, “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 1995, https://hbr.org/1995/01/disruptive-technologies-catching-the-wave.

Clayton M. Christensen, Michael E. Raynor & Rory McDonald, “What Is Disruptive Innovation?” Harvard Business Review,December 2015, https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation.

Tyler Cowen, “Is Innovation Over? The Case against Pessimism,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2016, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/review-essay/2016-02-15/innovation-over.

Swati Chaturvedi, “So What Exactly is ‘Deep Technology’?” LinkedIn, July 28, 2015, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/so-what-exactly-deep-technology-swati-chaturvedi.

Mike Cushing, “Moonshot Projects – Innovation or Wishful Thinking?” Enterprise Innovation, http://www.enterpriseinnovation.com/articles/moonshot-projects-innovation-or-wishful-thinking.

Vinod Khosla, “We Need Large Innovations,” Medium, January 1, 2018, https://medium.com/@vkhosla/we-need-large-innovations-58e3eaaf8138.

Josh Gans, The Disruption Dilemma (MIT Press, 2016), https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/disruption-dilemma.

Mark P. Mills, “Making Technological Miracles,” The New Atlantis, (Spring 2017): 37-55, http://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/making-technological-miracles.

Albert H. Segars, “Seven Technologies Remaking the World,” MIT Sloan Management Review, March 9, 2018, https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/seven-technologies-remaking-the-world.

Adam Thierer, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, (Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2016), https://www.mercatus.org/publication/permissionless-innovation-continuing-case-comprehensive-technological-freedom

Adam Thierer and Trace Mitchell, “The Many Forms of Entrepreneurialism,” The Bridge, August 30, 2018, https://www.mercatus.org/bridge/commentary/many-forms-entrepreneurialism

Adam Thierer, “Making the World Safe for More Moonshots,” The Bridge, February 5, 2018, https://www.mercatus.org/bridge/commentary/making-world-safe-more-moonshots

World Economic Forum, Deep Shift: Technology Tipping Points and Societal Impact (Geneva, Switzerland: September 2015), 3, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GAC15_Technological_Tipping_Points_report_2015.pdf.

September 6, 2018

The Problem with Calls for Social Media “Fairness”

There has been an increasing outcry recently from conservatives that social media is conspiring to silence their voices. Leading voices including President Donald Trump and Senator Ted Cruz have started calling for legislative or regulatory actions to correct this perceived “bias”. But these calls for fairness miss the importance of allowing such services to develop their own terms and for users to determine what services to use and the benefit that such services have been to conservatives.

Social media is becoming a part of our everyday lives and recent events have only increased our general awareness of this fact. More than half of American adults login to Facebook on a daily basis. As a result, some policymakers have argued that such sites are the new public square. In general, the First Amendment strictly limits what the government can do to limit speakers in public spaces and requires that such limits be applied equally to different points of view. At the same time, private entities are generally allowed to set terms regarding what speech may or may not be allowed on their own platforms.

The argument that modern day websites are the new public square and must maintain a neutral view point was recently rejected in a lawsuit between PraegerU and YouTube. Praeger believed that its conservative viewpoint was being silenced by YouTube decision to place many of its videos in “restricted mode.” In this case, the court found that YouTube was still acting as a private service rather than one filling a typical government role. Other cases have similarly asserted that Internet intermediaries have First Amendment rights to reject or limit ads or content as part of their own rights to speak or not speak. Conservatives have long been proponents of property rights, freedom of association, and free markets. But now, faced with platforms choosing to exercise their rights, rather than defend those values and compete in the market some “conservatives” are arguing for legislation or utilizing litigation to bully the marketplace of ideas into giving them a louder microphone. In fact, part of the purpose behind creating the liability immunity (known as Section 230) for such services was the principle that a variety of platforms would emerge with different standards and new and diverse communities could be created and evolve to serve different audiences.

A similar idea of a need for equal content was previously used by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and known as “the fairness doctrine”. This doctrine required equal access for groups or individuals wanting to express opposing views on public issues. In the 1980s Reagan era Republicans led the charge against this doctrine arguing that it violated broadcasters’ First Amendment rights and actually went against the public interest. In fact, many have pointed out that the removal of the fairness doctrine is what allowed conservative talk radio hosts like Rush Limbaugh to become major political forces. In the 2000s, when liberals suggested bringing back the fairness doctrine, conservatives were aghast and viewed it was an attack on conservative talk radio. Even now, President Trump has used social media as a way to deliver messaging and set his political agenda in a way that has never been done before. If anything, there are lower barriers to creating a new medium on the Internet than there are on the TV or radio airwaves. As a 2016 National Review article states if conservatives are concerned with how they are being treated by existing platforms, “The goal should not be to create neutral spaces; it should be to create non-neutral spaces more attractive than existing non-neutral spaces.” In other words rather than complaining that the odds are against them and demanding “equal time”, conservatives should try to compete by building more attractive platforms that promote the content moderation ideals they believe are best. But perhaps, the problem is they realize that ultimately difficult or unpopular content moderation decisions must be faced by any platform.

Content moderation is no easy task. Even for small groups differing beliefs can quickly result in grey areas that require difficult calls by an intermediary. For social media and other Internet intermediaries, when dealing with such issue on a scale of millions and a global diversity of what is and isn’t acceptable, content moderation becomes exponentially complicated. It is unsurprising that a rate of human and machine learning errors exist in making such decisions. AI might seem like a simple solution but such filters aren’t aware of the context in many cases. For example, a recently pointed out the difficulty that those with last names like Weiner and Butts face when trying to register for accounts on websites with AI filters to prevent offensive language. Leaving the task of content moderation to humans is both incredibly difficult on the moderators and may result in inconsistent results due to the large volume of content that must be moderated and differing interpretations of community standards. As Jason Koebler and Joseph Cox point out in their Motherboard article on the challenge of content moderation on a global scale that Facebook is dealing with, “If you take a single case, and then think of how many more like it exist across the globe in countries that Facebook has even less historical context for, simple rules have higher and higher chances of unwanted outcomes.” It is quite clear that if we as a society can’t decide on our own definitions of things like hate speech or bullying in many cases, how we can expect a third party public or private to make such decision in a way that satisfies every perspective?

The Internet has helped the world truly create a marketplace of ideas. The barriers to entry are rather low and the medium is constantly evolving. Because of social media and the Internet more generally conservative voices are able to reach a wider audience than before. Conservatives should be careful what they wish for with calls for “fairness,” because such power could actually prevent future innovation or new platforms and extend the status quo instead.

September 4, 2018

The Economist on Innovation Arbitrage

In recent essays and papers, I have discussed the growth of “innovation arbitrage,” which I defined as, “The movement of ideas, innovations, or operations to those jurisdictions that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity.” A new Economist article about “Why startups are leaving Silicon Valley,” discusses innovation arbitrage without calling it such. The article notes that, for a variety of reasons, Valley innovators and investors are looking elsewhere to set up shop or put money into new ventures. The article continues:

Other cities are rising in relative importance as a result. The Kauffman Foundation, a non-profit group that tracks entrepreneurship, now ranks the Miami-Fort Lauderdale area first for startup activity in America, based on the density of startups and new entrepreneurs. Mr Thiel is moving to Los Angeles, which has a vibrant tech scene. Phoenix and Pittsburgh have become hubs for autonomous vehicles; New York for media startups; London for fintech; Shenzhen for hardware. None of these places can match the Valley on its own; between them, they point to a world in which innovation is more distributed.

If great ideas can bubble up in more places, that has to be welcome. There are some reasons to think the playing-field for innovation is indeed being levelled up. Capital is becoming more widely available to bright sparks everywhere: tech investors increasingly trawl the world, not just California, for hot ideas. There is less reason than ever for a single region to be the epicentre of technology. Thanks to the tools that the Valley’s own firms have produced, from smartphones to video calls to messaging apps, teams can work effectively from different offices and places.

That’s the power of innovation arbitrage at work. Alas, the Economist article ends on a sour note, arguing that “innovation everywhere is becoming harder” because tech firms are becoming too big and anti-immigrant policies (especially in the US) are turning away some of the best and brightest minds. The latter is a real problem and one that is of the Trump Administration’s own making. By turning away the next generation of exciting innovators and limiting exciting start-up opportunities, America is shooting itself in the foot by undermining competitiveness and our competitive advantage among nations more generally. Which speaks to the first point made in the Economist article: If we want more competition to the big dogs, we need a lot more puppies. We’re not going to get them with backwards immigration policies. But nor will we get them by hobbling the biggest tech innovators. We shouldn’t be punishing success; we should be praising it.

We should recall Joseph Schumpeter’s essential insights in this regard. First, never underestimate how, in his words, “an untried technological possibility” can usher in one wave of “creative destruction” after another. Many critics talk about today’s “tech titans” (like Google, Facebook, Apple, and Amazon) as if they have always stalked the land. In reality, if you jump back in time just 15 years, it was Microsoft, MySpace, AOL Time Warner, Blackberry, and Motorola which allegedly possessed unassailable market power. And then creative destruction rolled into town. It happened before and it can happen again.

Schumpeter’s second insight was even more crucial and closely linked to his first. As I described it in a previous essay:

[Schumpeter] explained that uneven entrepreneurial gains — even supranormal short-term profits — must be tolerated if innovation is to occur. Innovators will only take risks if they can expect the potential for big gains from it. Attempts to curtail those potential benefits through hasty regulatory interventions or antitrust threats will sap the entrepreneurial spirit from the marketplace, limit technological innovation, and diminish the possibility of greater market dynamism and consumer choice over the long-haul.

“In this respect,” Schumpeter concluded, “perfect competition is not only impossible but inferior,” precisely because it would sabotage “the most powerful engine of that progress … those entrepreneurial profits which are the prizes offered by capitalist society to the successful innovator.”

Thus, if you want still more disruptive innovation and creative destruction, you absolutely cannot sabotage entrepreneurs by eliminating the quest for the prize of profitability. Innovators need to know that when they take big risks, big rewards are possible. If they see innovative acts punished, they will look elsewhere. Indeed, that’s one reason that innovation arbitrage happens with increasing regularity today.

That doesn’t mean we throw out antitrust law entirely. There can still be circumstances where market power is abused and needs to be addressed, but simply making big profits does not automatically qualify as an abuse of consumer welfare.

August 31, 2018

The Many Forms of Entrepreneurialism

by Adam Thierer & Trace Mitchell

[originally published on The Bridge on August 30, 2018.]

_____________________________________

What is an entrepreneur?

While it may seem straightforward, this question is deceptively complex. The term can be used in many different ways to describe a variety of individuals who engage in economic, political, or even social activities. Entrepreneurs affect almost every aspect of modern society. While most people probably have a general sense of what is meant when they hear the term entrepreneur, it can be difficult to provide a precise definition. This is due in no small part to the fact that some of the primary thinkers who have given substance to the term have placed their focus on different aspects of entrepreneurialism.

How Economists Talk About Entrepreneurs

Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter thought that the purpose of an entrepreneur was “to reform or revolutionize the pattern of production by exploiting an invention.” Schumpeterian entrepreneurs are highly creative, disruptive innovators who challenge the status quo in order to bring about new economic opportunities. American economist Israel Kirzner viewed the defining characteristic of entrepreneurs as “alertness.” Kirznerian entrepreneurs are individuals who are able to identify the ways in which a market could be moved closer to its equilibrium, such as recognizing a gap in knowledge between different economic actors.

In the time since Schumpeter and Kirzner helped lay the groundwork, a number of George Mason University-affiliated scholars have made major contributions to our understanding of entrepreneurialism. Don Boudreaux, Jerry Ellig and Daniel Lin, and Virgil Storr, Stefanie Haeffele and Laura Grube, have offered a merged view of Schumpeterian and Kirznerian entrepreneurialism, showing the significant overlap between the two approaches.

In this new way of looking at the issue, entrepreneurs are crucial to innovation, economic growth, and societal change. They are dynamic actors who respond to incentives and market signals. “Greater discovery and innovation are the benchmarks of dynamic competition,” note Ellig and Lin, “not the driving down of price to marginal cost.”

Productive and Unproductive Entrepreneurs

But are all of these dynamic entrepreneurs good for society? Among modern economists and political scientists, there is a general consensus that Schumpeterian-Kirznerian entrepreneurs are individuals who either find or create value within society. In recent decades, therefore, scholars have focused on applying those insights more broadly and developing a more robust way to categorize different types of entrepreneurial activity.

Another American economist, William Baumol, drew an important distinction between productive and unproductive entrepreneurs. He described productive entrepreneurs as people engaged in enterprising activity that generates value within society, such as the creation of new and innovative technologies. However, he also found that entrepreneurs could be unproductive if they did not create value or actively harmful if they destroyed value. “Indeed, at times the entrepreneur may even lead a parasitical existence that is actually damaging to the economy.” For Baumol, entrepreneurs are not defined as individuals who develop new methods of creating value but rather “persons who are ingenious and creative in finding ways that add to their own wealth, power, and prestige.”

Entrepreneurs in the Political Arena

An individual who is highly skilled at lobbying a particular governmental agency might be considered an entrepreneur, but that does not mean they are necessarily contributing value to society overall. Some scholars refer to this as political entrepreneurialism. Economists Peter Boettke and Christopher Coyne define political entrepreneurs as, “individuals who operate in political institutions and who are alert to profit opportunities created by those institutions.” Utah State University professors Randy Simmons, Ryan Yonk and Diana Thomas observe how such entrepreneurs seek specific rewards or privileges from political institutions and interactions through “alertness to previously unnoticed rent-seeking opportunities.” ‘Rent-seeking’ is an economic concept where one person or group is able to derive certain benefits from a particular institutional arrangement without actually creating value for others.

Our Mercatus Center colleague Matthew Mitchell has documented the “long list of privileges that governments occasionally bestow upon particular firms or particular industries.” Mitchell offers a taxonomy of the sort of privileges that political entrepreneurs seek. They include: “monopoly status, favorable regulations, subsidies, bailouts, loan guarantees, targeted tax breaks, protection from foreign competition, and noncompetitive contracts.”

All of these privileges could qualify as a form of Baumol’s “unproductive entrepreneurship” or, in the extreme, what he called destructive entrepreneurialism. Professors Sameeksha Desai, Zoltan Acs and Utz Weitzel define destructive entrepreneurship as “wealth-destroying (such as the destruction of inputs for production activities).” Whereas unproductive entrepreneurship “seeks to redistribute from one individual to another individual,” Boettke and Coyne note, “destructive entrepreneurship reduces the total surplus in an attempt by the entrepreneur to increase his own wealth.” Outright theft and violent conflict over resources are examples of destructive entrepreneurship.

When policymakers reward political destructive or unproductive entrepreneurs, it has profound effects on the well-being of ordinary people and entire nations.

Evasive and Regulatory Entrepreneurs

Not all political entrepreneurs are necessarily out to gain privileges from government at the expense of others, however. Some entrepreneurs are more interested in simply gaining greater freedom to innovate. Scholars have used the terms evasive entrepreneurs or regulatory entrepreneurs to describe such actors. Researchers Niklas Elert and Magnus Henrekson define evasive entrepreneurialism as “profit-driven business activity in the market aimed at circumventing the existing institutional framework by using innovations to exploit contradictions in that framework.” GMU economists Christopher Coyne and Peter Leeson argue that “[e]vasive activities include the expenditure of resources and efforts in evading the legal system or in avoiding the unproductive activities of other agents.” Regulatory entrepreneurs, according to legal scholars Elizabeth Pollman and Jordan Barry, are innovators who “are in the business of trying to change or shape the law” and are “strategically operating in a zone of questionable legality or breaking the law until they can (hopefully) change it.” Evasive or regulatory entrepreneurs generally adopt a “permissionless innovation” approach to both business and political activities.

Generally speaking, evasive and regulatory entrepreneurs are synonymous, although regulatory entrepreneurialism implies a more active intent to change policy through entrepreneurial acts. Evasive entrepreneurs might also be ignorant of what the law says, whereas regulatory entrepreneurs, by definition, understand how the law negatively affects their efforts and seek to change policy through their actions.

However, both evasive and regulatory entrepreneurs are distinct from what economists Alexandre Padilla and Nicolas Cachanosky call indirectly productive entrepreneurs. They argue that regulation often creates unintended consequences which lead to new entrepreneurial opportunities. Indirectly productive entrepreneurs seize upon these opportunities by finding ways to mitigate the costs associated with specific regulations. Unlike regulatory entrepreneurs, who desire to change policy, or evasive entrepreneurs, who seek to avoid it, indirectly productive entrepreneurs create value by reducing the harm caused by policies. For example, the Transportation Safety Administration (TSA) has a policy prohibiting passengers from bringing liquids on an airplane unless they are kept in a container that is smaller than 3.4 ounces. As a response, several indirectly productive entrepreneurs have created “TSA Approved” containers for shampoo, mouthwash, and other toiletries that make it easier for passengers to comply with the regulation.

Social Entrepreneurs

There is also a growing acknowledgment that entrepreneurial behavior can transcend economic or political activities. Mercatus scholars have defined social entrepreneurs as individuals who engage in “innovative, social value-creating activity that can occur within or across the nonprofit, business, or government sectors.” Social entrepreneurial activities are not typically in pursuit of compensation or profit, but that need not always be the case and “the distinction between social and commercial entrepreneurship is not dichotomous, but… a continuum ranging from purely social to purely economic,” they note.

Some sort of social mission drives this type of entrepreneurship, and social entrepreneurialism will often incorporate what MIT economist Eric von Hippel refers to as “free innovation.” He defines a free innovation as “a functionally novel product, service, or process that (1) was developed by consumers at private cost during their unpaid discretionary time (that is, no one paid them to do it) and (2) is not protected by its developers, and so is potentially acquirable by anyone without payment—for free.” A good example of free innovation would be social entrepreneurs using 3D printers and open source designs to voluntarily create prosthetics for children with limb deficiencies.

Conclusion

As this brief survey reveals, there are many different forms of entrepreneurialism. Individuals can act in an entrepreneurial fashion in pursuit of many different objectives: profits, fame, social or legal change, or even personal or organizational privileges that come at the expense of others. Clearly, not all forms of entrepreneurialism produce socially beneficial outcomes. Policymakers should seek to foster and reward Schumpeterian-Kirznerian entrepreneurs given the positive implications for innovation and economic growth and avoid falling into the trap of rewarding political entrepreneurs, who instead seek to game laws and regulations to their own advantage.

Given the extensive research and academic literature inherent to this subject, we’ve curated a list of selected readings below.

_____________________________________

Further Reading

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 370-384. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00107.x

Baumol, W. (1968). Entrepreneurship in Economic Theory. The American Economic Review,58(2), 64-71. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1831798?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Baumol, W. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive and Destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 893-921. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2937617?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

Boettke, P. J., & Coyne, C. J. (2009). Context Matters: Institutions and Entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 135-209. Retrieved from https://www.nowpublishers.com/article/Details/ENT-018.

Boudreaux, D. (1994), Schumpeter and Kirzner on Competition and Equilibrium. In P. Boetkke & D. Prychitko (Eds.), The Market Process: Essays in the Contemporary Austrian Economics (pp. 52-61). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Retrieved from http://cafehayek.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Heres-a-paper-that-I-wrote-back-in-1986-or-1987.-In-it-I-attempt-to-explain-how-non-price-competition-can-be-equilibrating..pdf

Coyne, C. J., & Leeson, P. T. (2004). The Plight of Underdeveloped Countries. Cato Journal, 24(3), 235-249. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=869123

Desai, S., & Acs, Z. J. (2007). A theory of destructive entrepreneurship. Jena Economic Research Papers no. 85, Friedrich-Schiller University and Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena, Germany, October, Retrieved from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/25657/1/553834517.PDF

Dees, J. G. (2001), ‘The meaning of Social Entrepreneurship’. The Fuqua School of Business, Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship.

Desai, S., Acs, Z.J., and Weitzel, U. (2013), “A model of destructive entrepreneurship: insight for conflict and post-conflict recovery,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 20–40, Retrieved from https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/170796/170796.pdf

Elert, N. & Henrekson, M. (2016). Evasive Entrepreneurialism. Small Business Economics, 47(1), 95-113. Retrieved from http://www.ifn.se/wfiles/wp/wp1044.pdf.

Ellig, J. & Lin, D. (2001). A Taxonomy of Dynamic Competition Theories. In J. Ellig (Ed.), Dynamic Competition and Public Policy: Technology, Innovation, and Antitrust Issues (pp. 16-44). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/dynamic-competition-and-public-policy/taxonomy-of-dynamic-competition-theories/C536918DD453ADB34A47F48EDA6D21B7.

Hippel, E. V. (2017). Free Innovation. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Retrieved from https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/free-innovation.

Kirzner, I. M. (2009). The Alert and Creative Entrepreneur: A Clarification. Small Business Economics, 32(2), 145-152. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11187-008-9153-7

Lucas, D. S. & Fuller, C. S. (2015). Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive—Relative to What? Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 7, 45-49. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352673417300033.

Mitchell, M. D. (2012). The Pathology of Privilege: The Economic Consequences of Government Favoritism. Mercatus Center. Retrieved from https://www.mercatus.org/publication/pathology-privilege-economic-consequences-government-favoritism.

Murphy, K.M., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1991) “The Allocation of Talent: Implications for Growth,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2): 503-530. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w3530

Murphy, K.M., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1993) “Why is rent-seeking so costly to growth?” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 83 (2): 409-414. Retrieved from https://scholar.harvard.edu/shleifer/publications/why-rent-seeking-so-costly-growth

Padilla, A. & Cachanosky, N. (2016). Indirectly Productive Entrepreneurship. Journal of Enterprise and Public Policy, 5(2), 161–175. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2584741.

Pollman, E. & Barry, J. M. (2017). Regulatory Entrepreneurship. Southern California Law Review, 90, 383-448. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2741987.

Schumpeter, J. (1942, 2008). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (3rd ed.). New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Capitalism-Socialism-Democracy-Joseph-Schumpeter/dp/0061561614.

Simmons, R. T., Yonk, R. M., & Thomas, D. W. (2011). Bootleggers, Baptists, and Political Entrepreneurs: Key Players in the Rational Game and Morality Play of Regulatory Politics. The Independent Review, 15(3), 367-381. Retrieved from http://www.independent.org/pdf/tir/tir_15_03_3_simmons.pdf.

Storr, V., Haeffele, S., & Grube, L. (2015). The Entrepreneur as a Driver of Social Change. In Community Revival in the Wake of Disaster (pp. 11-31) New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from

https://www.palgrave.com/us/book/9781137286086

Thierer, A. (2018). Evasive Entrepreneurialism and Technological Civil Disobedience: Basic Definitions, The Bridge. Retrieved from https://www.mercatus.org/bridge/commentary/evasive-entrepreneurialism-and-technological-civil-disobedience-basic-definitions

Thierer, A. (2016). Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom. Retrieved from https://www.mercatus.org/publication/permissionless-innovation-continuing-case-comprehensive-technological-freedom

Thierer, A. (2017). You’re in Joseph Schumpeter’s economy now. Learn Liberty, Retrieved from http://www.learnliberty.org/blog/youre-in-joseph-schumpeters-economy-now

August 30, 2018

We’re All Media Marxists Now! Conservatives Move to Socialize the Soapbox

Thirteen years ago I penned an essay entitled, “Your Soapbox is My Soapbox!” It was condensed from a 2005 book I had released at the same time called Media Myths. My research and writing during that period and for fifteen years prior to that was focused on the dangers associated with calls by radical Left-leaning media scholars and policy activists for a veritable regulatory revolution in the way information and communication technology (ICT) platforms were operated. They pushed this revolution using noble-sounding rhetoric like “fairness in coverage,” “right of reply,” “integrity of public debate,” “preserving the public square,” and so on. Their advocacy efforts were also accompanied by calls for a host of new regulatory controls including a “Bill of Media Rights” to grant the public a litany of new affirmative rights over media and communications providers and platforms.

But no matter how much the so-called “media access” movement sought to sugarcoat their prescriptions, in the end, what those Left-leaning scholars and advocates were calling for was sweeping state control of media and communications technologies and platforms. In essence, they wanted to socialize private soapboxes and turn them into handmaidens of the state.

Here’s the way I began my old “soapbox” essay:

Imagine you built a platform in your backyard for the purpose of informing or entertaining your friends of neighbors. Now further imagine that you are actually fairly good at what you do and manage to attract and retain a large audience. Then one day, a few hecklers come to hear you speak on your platform. They shout about how it’s unfair that you have attracted so many people to hear you speak on your soapbox and they demand access to your platform for a certain amount of time each day. They rationalize this by arguing that it is THEIR rights as listeners that are really important, not YOUR rights as a speaker or the owner of the soapbox.

That sort of scenario could never happen in America, right? Sadly, it’s been the way media law has operated for several decades in this country. This twisted “media access” philosophy has been employed by federal lawmakers and numerous special interest groups to justify extensive and massively unjust regime of media regulation and speech redistributionism. And it’s still at work today.

That was 2005. What’s amazing today is that this same twisted attitude is still on display, but it is conservatives who are now the ring-leaders of the push to socialize soapboxes!

Conservatives were squarely against such soapbox socialism when I penned my earlier essay and book. During that time, they feared that the media access movement would devolve into a political witch hunt aimed at singling them out and eliminating the many new popular personalities and platforms that offered the public Right-of-center voices and viewpoints.

But it’s a new day in America and conservatives have now flipped this script and are using the media access movement playbook to call for massive state control over private media and technology platforms in the name of eradicating supposed “bias” against them and their views.

Apparently everyone’s a Media Marxist these days, beginning with President Trump! Claiming that there is some sort of grand anti-conservative conspiracy afoot, President Trump and many of his defenders are pushing for greater government control of the media and tech companies. The White House is apparently “taking a look” at the idea of regulating Google because it is part of the “fake news media.” (Over at TechDirt, Zach Graves has a thorough debunking of such nonsense.) Of course, this follows Trump’s seemingly endless jihad against older media outlets, especially large newspapers and cable news enterprises that he disfavors.

Meanwhile, a new White House “We the People” petition to “Protect Free Speech in the Digital Public Square” already has almost 40,000 signatures. “The internet is the modern public square,” the manifesto begins. It continues on to claims that “the free and open internet has become a controlled, censored space, monopolized by a few unaccountable corporations” and that “[b]y banning users from their platforms, those corporations can effectively remove politically unwelcome Americans from the public square.” It concludes with the following call to action: “The President should request that Congress pass legislation prohibiting social media platforms from banning users for First Amendment-protected speech. The power to block lawful content should be in the hands of individual users – not [Facebook’s] Mark Zuckerberg or [Twitter’s] Jack Dorsey.”

Such rhetoric and proposals are indistinguishable from what the Left-leaning media access advocates were calling for in the past.

Is “media Marxism” too strong a term to use in this regard? Well, the textbook definition of Marxism involves state control of the means of production. In the case of information platforms, control of the means of production would involve the forcible surrender of some combination of the underlying editorial control that the owners have over their speech platforms as well as potential state control of the algorithms and other technical foundations of digital platforms.

And so let’s hear from former White House strategist Steve Bannon commenting to CNN on what he thinks needs to be done next:

>> Bannon said Big Tech’s data should be seized and put in a “public trust.” Specifically, Bannon said, “I think you take [the data] away from the companies. All that data they have is put in a public trust. They can use it. And people can opt in and opt out. That trust is run by an independent board of directors. It just can’t be that [Big Tech is] the sole proprietors of this data…I think this is a public good.” Bannon added that Big Tech companies “have to be broken up” just like Teddy Roosevelt broke up the trusts.”

>> Bannon attacked the executives of Facebook, Twitter and Google. “These are run by sociopaths,” he said. “These people are complete narcissists. These people ought to be controlled, they ought to be regulated.” At one point during the phone call, Bannon said, “These people are evil. There is no doubt about that.”

>> Bannon said he thinks “this is going to be a massive issue” in future elections. He said he thinks it will probably take until 2020 to fully blossom as a campaign issue, explaining, “I think by the time 2020 comes along, this will be a burning issue. I think this will be one of the biggest domestic issues.” Bannon said the “#MeToo movement has brought the issue of consent front and center” and argued that “this is going to bring the issue of digital consent front and center.”

On one hand, Bannon no longer works in Trump’s White House, so perhaps it isn’t fair to say that his views and prescriptions are tantamount to the President’s views. But Bannon was saying similar things while he was in the White House with Trump and the President’s surrogates have been continuously upping their rhetoric to suggest that they are serious about moving against the ICT sector in some fashion.

So, apparently we now inhabit a Bizaro World where the Hard Right has replaced the Hard Left in the U.S. in the never-ending drama of speech control. In past decades, some conservatives favored media regulation, of course. In fact, in the heyday of the Fairness Doctrine, many leading conservative voices insisted that regulation was needed to counter supposed “liberal bias” in broadcasting. It was only when Rush Limbaugh and many other conservatives came along in the late 1980s / early 1990s and gained a significant audience on talk radio that conservative sympathy for the Fairness Doctrine completely disappeared. In fact, conservatives then became vociferous critics of the Doctrine and demanded a stake be driven through its heart. Eventually, they did just that. But even during the time when some conservative pundits supported the Fairness Doctrine, that support was fairly limited and tepid. And you almost never heard conservatives supporting radical state control of the press as a solution to perceived bias.

Yet, here we are now with Trump and many of his allies floating proposals to treat information platforms as the equivalent of essential facilities or “public squares” which would have some sort of amorphous fiduciary obligations or “public interest” responsibilities to serve the public however politicians and bureaucrats in Washington see fit. That could entail anything from “search neutrality” to a new Fairness doctrine / right of reply mandate to a full-blown antirust breakup.

Like the Hard Left before them, the Hard Right has apparently come to view ICT platforms as just another part of the socio-political superstructure to be controlled from above to achieve their own ends. Trump and his allies have repeatedly referred to the press as the “enemy of the American people.” (His latest tweet using that phrase has already racked up almost 84,000 likes.) That’s totalitarian talk, and it softens the ground for the sort of takeover that Bannon and others desire. The “Fake News” that President Trump and his surrogates decry includes not just traditional journalism outlets but all forms of information production and dissemination. Trump wants them all to bend the knee before him. Because they won’t, apparently they are to be punished.

If Trump and his allies get their way, America would join the ranks of repressive states around the globe who seek to control speech platforms for their own ends. That sort of totalitarian impulse is repugnant to the values of a democratic republic that values open inquiry, freedom of speech and expression, press freedom, and the freedom to know about and report on the world around us.

As I concluded my earlier “soapbox” essay back in 2005:

This arrogant, elitist, anti-property, anti-freedom ethic is what drives the media access movement and makes it so morally repugnant. Freedom doesn’t begin by fettering the press with more chains, it begins by removing those that already exist and then erecting a firm wall between State and Press. The media access crowd has succeeded in breaching that wall with seven decades of misguided and unjust regulation of the press. The movement back toward a truly free press begins by understanding the error in their thinking, rejecting that reasoning, and then embracing, once again, the original vision of the First Amendment as a bulwark against government control of speech and the press.

In closing, this is a good moment for those on the moderate Left to reflect upon what they have enabled by sketching out and defending this intellectual blueprint for media control. The Left helped make the bed that Donald Trump is now getting cozy in. Many Hard Left scholars repeatedly told us that it was with the very best of intentions that they advocated more state control of the ICT sectors. There’s no bringing those radicals around to seeing the mistake they made. They will just double down on their proposals and claim that once “their team” gets back in power, all will be fine. It is utter poppycock, but they won’t care one bit.

The moderate Left, however, should be more sensible than that because they have been the great defenders of the First Amendment and freedom of speech in modern American history. And they understand that the danger of the slippery slope is very real when it comes to speech controls and how they might undermine our First Amendment heritage. When the moderate Left allows radical media theorists and regulatory advocacy groups to push extreme media control measures, however, they are creating speech control mechanisms that are very susceptible to being overtaken by their enemies and then used against them later on. And now we have a President who is doing exactly that.

It is a truly horrifying moment in the history of the American Republic. Hopefully we get through it and learn something from it.

August 28, 2018

Here’s why state net neutrality laws may encourage ISP filtering

A few states have passed Internet regulations because the Trump FCC, citing a 20 year US policy of leaving the Internet “unfettered by Federal or State regulation,” decided to reverse the Obama FCC’s 2015 decision to regulate the Internet with telephone laws.

Those state laws regulating Internet traffic management practices–which supporters call “net neutrality”–are unlikely to survive lawsuits because the Internet and Internet services are clearly interstate communications and FCC authority dominates. (The California bill also likely violates federal law concerning E-Rate-funded Internet access.)

However, litigation can take years. In the meantime ISP operators will find they face fewer regulatory headaches if they do exactly what net neutrality supporters believe the laws prohibit: block Internet content. Net neutrality laws in the US don’t apply to ISPs that “edit the Internet.”

The problem for net neutrality supporters is that Internet service providers, like cable TV providers, are protected by the First Amendment. In fact, Internet regulations with a nexus to content are subject to “strict scrutiny,” which typically means regulations are struck down. Even leading net neutrality proponents, like the ACLU and EFF, endorse the view that ISP curation is expressive activity protected by First Amendment.

As I’ve pointed out, these First Amendment concerns were raised during the 2016 litigation and compelled the Obama FCC to clarify that its 2015 “net neutrality” Order allows ISPs to block content. As a pro-net neutrality journalist recently wrote in TechCrunch about the 2015 rules,

[A] tiny ISP in Texas called Alamo . . . wanted to offer a “family-friendly” edited subset of the internet to its customers.

Funnily enough, this is permitted! And by publicly stating that it has no intention of providing access to “substantially all Internet endpoints,” Alamo would exempt itself from the net neutrality rules! Yes, you read that correctly — an ISP can opt out of the rules by changing its business model. They are . . . essentially voluntary.

The author wrote this to ridicule Judge Kavanaugh, but the joke is clearly not on Kavanuagh.

In fact, under the 2015 Order, filtered Internet service was less regulated than conventional Internet service. Note that the rules were “essentially voluntary”–ISPs can opt out of regulation by filtering content. The perverse incentive of this regulatory asymmetry, whereby the FCC would regulate conventional broadband heavily but not regulate filtered Internet at all, was cited by the Trump FCC as a reason to eliminate the 2015 rules.

State net neutrality laws basically copy and paste from the 2015 FCC regulations and will have the same problem: Any ISP that forthrightly blocks content it doesn’t wish to transmit–like adult content–and edits the Internet is unregulated.

This looks bad for net neutrality proponents leading the charge, so they often respond that the Internet regulations cover the “functional equivalent” of conventional (heavily regulated) Internet access. Therefore, the story goes, regulators can stop an ISP from filtering because an edited Internet is the functional equivalent of an unedited Internet.

Curiously, the Obama FCC didn’t make this argument in court. The reason the Obama FCC didn’t endorse this “functional equivalent” response is obvious. Let’s play this out: An ISP markets and offers a discounted “clean Internet” package because it knows that many consumers would appreciate it. To bring the ISP back into the regulated category, regulators sue, drag the ISP operators into court, and tell judges that state law compels the operator to transmit adult content.

This argument would receive a chilly reception in court. More likely is that state regulators, in order to preserve some authority to regulate the Internet, will simply concede that filtered Internet drops out of regulation, like the Obama FCC did.

As one telecom scholar wrote in a Harvard Law publication years ago, “net neutrality” is dead in the US unless there’s a legal revolution in the courts. Section 230 of the Telecom Act encourages ISPs to filter content and the First Amendment protects ISP curation of the Internet. State law can’t change that. The open Internet has been a net positive for society. However, state net neutrality laws may have the unintended effect of encouraging ISPs to filter. This is not news if you follow the debate closely, but rank-and-file net neutrality advocates have no idea. The top fear of leading net neutrality advocates is not ISP filtering, it’s the prospect that the Internet–the most powerful media distributor in history–will escape the regulatory state.

August 27, 2018

“Tech Vouchers”: Putting consumers in control of the FCC’s $4.5 billion rural telecom fund

The US government has spent about $100 billion on rural telecommunications in the last 20 years. (That figure doesn’t include the billions of dollars in private investment and state subsidies.) It doesn’t feel like it in many rural areas.

The lion’s share of rural telecom subsidies come from the FCC’s “high-cost” fund, which is part of the Universal Service Fund. The high-cost fund currently disburses about $4.5 billion per year to rural carriers and large carriers serving rural areas.

Excess in the high-cost program

Bill drafters in Congress and the CBO, after the passage of the 1996 Telecom Act creating the Fund, expected the USF program subsidies to decrease over time. That hasn’t happened. The high-cost fund has increased from $800 million in 1997 to $4.5 billion today.

The GAO and independent scholars find evidence of waste in the rural fund, which traditionally funded rural telephone (voice) service. For instance, former FCC chief economist Prof. Tom Hazlett and Scott Wallsten estimate that “each additional household is added to voice networks at an annual USF cost of about $25,000.” There are at least seven high-cost programs and each has its own complex nomenclature and disbursement mechanisms.

These programs violate many best practices for public finance. Shelanski and Hausman point out, for instance, that a huge distortion for decades has been US regulators’ choice to tax (demand-elastic) long-distance phone services to fund the (demand-inelastic) local phone services. The rural fund disbursement mechanisms also tempt providers to overinvest in goldplated services or, alternatively, inflate operational costs. Wallsten found that about 59 cent for every dollar of rural subsidy goes to carriers’ overhead.

To that end, the high-cost program appears to be supporting fewer households despite the program’s increasing costs. I found in Montana, for instance, that from 1999 to 2009 subsidies to carriers rose 40 percent even while the number of subsidized rural lines fell 30 percent. The FCC’s administrative costs for the four USF programs also seem high. According to the FCC’s most recent report, administrative costs are about $172 million annually, which is more than what 45 states received in high-cost funds in 2016.

A proposal: give consumers tech vouchers

A much more transparent and, I suspect, more effective way of satisfying Congress’ requirement that rural customers have “reasonably comparable” rates to urban customers’s rates for telecom services is to give “tech vouchers.” Vouchers are used in housing, heating, and food purchases in the US, and the UK is using them for rural broadband.

My colleague Trace Mitchell and I are using Census and FCC data to calculate about how much rural households could receive if the program were voucher-ized. Assuming all high-cost funds disbursed to states in 2016 were converted into broadband vouchers, these are our estimates.

If vouchers were distributed equally among rural households today, every rural household in the US (about 20% of US households) would receive about $15 per month to spend on the broadband provider and service of their choice. Low-income rural households could tack on the $9.25 USF Lifeline subsidy and any state subsidies they’re eligible for.

Perfect equality probably isn’t the best way to subsidize rural broadband. The cost of rural service is driven primarily by the housing density, and providing telecom to a rural household in the American West and Great Plains is typically more expensive than providing telecom to a rural household in the denser Northeast, and this is borne out in the FCC’s current high-cost disbursements. For instance, Vermont and Idaho have about the same number of rural households but rural carriers in Idaho receive about 2x as much as rural carriers in Vermont.

However, some disparities are hard to explain. For example, despite South Carolina’s flatter geography than and similar rural population as North Carolina, North Carolina carriers receive, on a per-household basis, only about 40% what South Carolina carriers receive. Alabama and Mississippi have similar geographies and rural populations but Alabama carriers receive only about 20% of what Mississippi carriers receive.

A tiered system of telecom vouchers smooths the disparities, empowers consumers, and simplifies the program. We’ve sorted the states into six tiers based on how much the state received on a per-household basis in 2016. This ranking puts large, Western states in the top tier and denser, Northeastern states in the bottom tier.

In our plan, every rural household in five hardest-to-serve Tier 1 states (Alaska, Kansas, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota) would receive a $45 monthly discount on the Internet service of their choice, whether DSL, cable, fixed wireless, LTE, or satellite. As they do in the UK, eligible rural households would enter a coupon code when they receive their telecom services bill and the carrier would reduce the price of service accordingly.

Similarly, every rural household in:

Tier 2 states (ten states) would receive a $30 monthly discount.

Tier 3 states (ten states) would receive a $19 monthly discount.

Tier 4 states (ten states) would receive a $13 monthly discount.

Tier 5 states (ten states) would receive a $6 monthly discount.

Tier 6 states (five states) would receive a $3 monthly discount.

$3 per month per rural household doesn’t sound like much but, for each of these states (Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Rhode Island), this is more than the state currently receives in rural funds. In Connecticut, for instance, the current high-cost funding amounts to about 25 cents per rural household per month.

Under this (tentative) scheme, the US government would actually save $25 million per year from the current disbursements. And these are conservative numbers since they assume 100% participation from every rural household in the US. It’s hard to know what participation would look like but consider Lifeline, which is essentially a phone and broadband voucher program for low-income households. At $9.25 per month, 28% of those eligible for Lifeline participate. This is just a starting point and needs more analysis, but it seems conceivable that the FCC could increase the rural voucher amounts above, expect 50% participation, and still save the program money.

Conclusion

As Jerry Hausman and Howard Shelanski have said, “It is well established that targeted subsidies paid from general income tax revenues are often the most efficient way to fund specific activities.” Current law doesn’t allow allow for tech vouchers from general income taxes, but the FCC could allow states to convert their current high-cost funds into tech vouchers for rural households. Vouchers would be more tech-neutral, less costly to administer, and, I suspect, more effective and popular.

Code Is Speech: 3D-Printed Guns Edition

Is code speech? That is one of the timeless questions that comes up again and again in the field of Internet law and policy. Many books and countless papers and essays have touched on this topic. Personally, I’ve always thought it was a bit silly that this is even a serious question. After all, if code isn’t speech, what the heck is it?

We humans express ourselves in many creative ways. We speak and write. We sing and dance. We paint and sculpt. And now we code. All these things are forms of human expression. Under American First Amendment jurisprudence, expression is basically synonymous with speech. We very tightly limit restrictions on speech and expression because it is a matter of personal autonomy and also because we believe that there is a profound danger of the proverbial slippery slope kicking in once we allow government officials to start censoring what they regard as offensive speech or dangerous expression.

Thus, we when creative people come up with creative thoughts and use computers and software to express them in code, that is speech. It is fundamentally no different than using a pencil and pad of paper to write a manifesto, or using a guitar and microphone to sing a protest song. The authorities might not like the resulting manifesto or protest song–in fact, they might feel quite threatened by it–but that fact also makes it clear why, in both cases, that expression is speech and that speech is worth defending. Moreover, the methods or mediums of speech production and dissemination–pencils, paper, guitars, microphones, etc.–are what Ithiel de Sola Pool referred to as “Technologies of Freedom.” They help people extend their voices and to communicate with the world, while also learning more about it.

Which brings us to the 3D printers and the code behind the open source blueprints that many people share to fabricate things with 3D printers. Washington Post reporter Meagan Flynn was kind enough to call me last week and ask me to comment for a story she was putting together about the ongoing legal fights over 3D-printed firearms in generally and the efforts of Cody Wilson and Defense Distributed in particular. Wilson is a self-described crypto-anarchist who has landed in hot water with federal and state officials for making available open source blueprints for the 3D-printed firearms freely available to the public. Federal efforts aimed at stopping Wilson and Defense Distributed haven’t worked and now state attorneys general are seeking to impose legal restrictions on him.

Flynn’s WashPo article offered an outstanding overview of everything that is happening on this front, so I won’t rehash it all here. But I wanted to reproduce my portions of her story here and just add a few more thoughts. Here’s the block of the story that mentioned my thoughts:

Adam Thierer, who specializes in the intersection of free speech and technology at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, said the debate over the computer code for the 3-D-printable guns is the same song he heard during the Crypto Wars — but more like a remix. Guns, of course, pose different risks than encryption technology. Thierer said he thinks the Defense Distributed code is almost certainly speech, but the question is whether the government can demonstrate a compelling interest to regulate it.

The problem with the states’ argument, he contended, is that it would be a “stretch” for the judge to decide that the computer code itself skirts the states’ gun laws, as those laws generally center on possession of actual guns. It would be easier for the states to regulate 3-D-printed guns themselves through new laws, he said, rather than seeking to regulate the code that creates them. “They would have to make the argument that the speech itself is essentially the device,” he said. “Nothing is stopping them from regulating firearms. But the underlying speech is not in their purview. There has to be a distinction made between the speech and the byproduct of speech.”

In our recent essay, “3D Printers, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Tech Regulation,” Andrea O’Sullivan and I offered more extensive discussion of the legal issues at play here. And in a 2016 law review article entitled, “Guns, Limbs, and Toys: What Future for 3D Printing?” my co-author Adam Marcus and I discussed several examples of how additive manufacturing and the “maker” revolution are making the governance of various emerging technologies quite challenging.

The key points my co-authors and I try to make in these articles is that:

These controversies aren’t going away; they are only going to expand as “evasive entrepreneurs” find new interesting ways to use 3D printers to express themselves.

Regardless of what is being produced with 3D printers, the code and blueprints behind them are speech and deserve protection. And under American free speech jurisprudence, such code will almost certainly win such protections from courts when legislators or regulators seek to censor or regulate them.

The better way to regulate 3D printing is to focus on the physical manifestations of speech/expression. That is, focus on the user and the use, not the speech behind it. As Marcus and I put it in our law review article, “the proper focus of regulation should remain on the user and uses of firearms, regardless of how they are manufactured.” The U.S. has an extensive array of federal and state firearm regulations, and they can and should continue to apply to 3D-printed weapons. Likewise, a 3D-printed prosthetic limb is still a medical device, and the Food and Drug Administration can regulate it according if it sees fit. But in neither case should the underlying speech (i.e., the code) behind such inventions be censored.

August 21, 2018

Should We Teach Children to Be Entrepreneurs, or How to Pay Licensing Fees?

Yesterday was National Lemonade Day. Over at the Mercatus Bridge blog, Jennifer Skees and I used the opportunity to highlight the increasing regulatory crackdown on kids operating ventures without first seeking the proper permits from local authorities. We ask, “wouldn’t it be better to teach them the value of hard work and entrepreneurial effort instead of threatening them with penalties for not getting costly permits to do basic jobs?” Here’s our answer:

_______________

Today is National Lemonade Day. For many Americans a lemonade stand was their first experience in entrepreneurship. But unfortunately, this time honored tradition that teaches the value of hard work, entrepreneurship, and innovation may be under threat from overzealous grown-ups.

Should we really force kids to get licenses to start lemonade stands, sell bottles of water outside a ballpark, or mow lawns for a little extra money? And wouldn’t it be better to teach them the value of hard work and entrepreneurial effort instead of threatening them with penalties for not getting costly permits to do basic jobs?

Recent news stories have highlighted examples of kids being confronted with local regulations that essential tell them not to be entrepreneurial until they’ve gotten someone’s blessing–or else face fines or other penalties for those efforts.