Adam Thierer's Blog, page 10

September 3, 2020

On Defining “Industrial Policy”

In his debut essay for the new Agglomerations blog, my former colleague Caleb Watney, now Director of Innovation Policy for the Progressive Policy Institute, seeks to better define a few important terms, including: technology policy, innovation policy, and industrial policy. In the end, however, he decides to basically dispense with the term “industry policy” because, when it comes to defining these terms, “it is useful to have a limiting principle and it’s unclear what the limiting principle is for industrial policy.”

I sympathize. Debates about industrial policy are frustrating and unproductive when people cannot even agree to the parameters of sensible discussion. But I don’t think we need to dispense with the term altogether. We just need to define it somewhat more narrowly to make sure it remains useful.

First, let’s consider how this exact same issue played out three decades ago. In the 1980s, many articles and books featured raging debates about the proper scope of industrial policy. I spent my early years as a policy analyst devouring all these books and essays because I originally wanted to be a trade policy analyst. And in the late 1980s and early 1990s, you could not be a trade policy analyst without confronting industrial policy arguments.

This was the era of what some called “Japan, Inc.” and Japan-bashing. South Korea and Taiwan were also part of that discussion, but the primary focus was “the Japan Model” and whether it represented the optimal industrial policy for the modern economy. That “Japan Model” sounds much like what is heard today when pundits reference China and its industrial policy model: Generous (and highly targeted) R&D investments, government-led public-private consortia, industrial trade policies (a combination of export assistance plus restrictions on imports and foreign investment), and other forms of targeted government support for specific sectors or technological developments.

In the 1980s Japan’s economy started expanding rapidly and many Japanese multinationals began making major investments in US businesses and properties. The Japanese government played an active role in facilitating much of this. Suddenly, lots of people in the US were debating the wisdom of America falling in line and adopting its own industrial policy to counter Japan. Panic was in the air in academic and legislative circles. Lawmakers were literally smashing Japanese electronics with sledgehammers on the stairs of the US Capitol. Meanwhile, pundits were publishing a steady steam of pessimistic books with titles asking, Can America Compete?, while others suggested that the US was Trading Places with Japan.

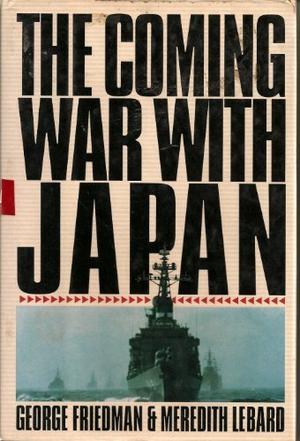

Japan-loathing probably reached its apex around 1991 or ’92 with the publication of the non-fiction book, The Coming War with Japan, and then Michael Crichton’s fictional book (and then adapted movie), Rising Sun. Japan’s new economic model was going to steamroll US innovators and allow them to dominate the global economy for decades to come.

Three decades later, we know how all this played out. The US never went to war again with Japan. We just kept trading peacefully with them, thankfully. Meanwhile, the “Japan, Inc.” industrial policy model didn’t quite pan out the way they hoped (or that US pundits feared). In a 2007 report, Marcus Noland of the Peterson Institute for International Economics summarized Japan’s industrial policy results in bleak terms:

Japan faces significant challenges in encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship. Attempts to formally model past industrial policy interventions uniformly uncover little, if any, positive impact on productivity, growth, or welfare. The evidence indicates that most resource flows went to large, politically influential “backward” sectors, suggesting that political economy considerations may be central to the apparent ineffectiveness of Japanese industrial policy.

But I don’t want to get diverted into the specifics of why Japan’s industrial policy didn’t work. Rather, I just want to make the simple point that Japan definitely had an industrial policy that we can still evaluate today. We should not abandon all use of the term industrial policy because, once defined in a more focused fashion, it remains a useful concept worthy of serious academic study and deliberation.

Jump back to the mid-80s and flip through the individual contributions to this AEI book on The Politics of Industrial Policy. It features hot debates over the exact issue we’ve still trying to figure out today. Essays by Aaron Wildavsky, Thomas McCraw, and James Fallows generally argued for a broad conception of what industrial policy should include. Others such as economist Herbert Stein insisted upon a much narrower reading of the term.

Jump back to the mid-80s and flip through the individual contributions to this AEI book on The Politics of Industrial Policy. It features hot debates over the exact issue we’ve still trying to figure out today. Essays by Aaron Wildavsky, Thomas McCraw, and James Fallows generally argued for a broad conception of what industrial policy should include. Others such as economist Herbert Stein insisted upon a much narrower reading of the term.

Into that debate stepped economic historian Ellis W. Hawley with a wonderful essay on industrial policy efforts in the pre-New Deal era. Hawley began his essay with what I still regard as the best understanding of what “industry policy” really means in practice. Here is Hawley’s definition:

By industrial policy I mean a national policy aimed at developing or retrenching selected industries to achieve national economic goals. In this usage, I follow those who distinguish such a policy, both from policies aimed at making the macroeconomic environment more conducive to industrial development in general and from the totality of microeconomic interventions aimed at particular industries. To have an industrial policy, a nation must not only be intervening at the microeconomic level but also have a planning and coordinating mechanism through which the intervention is rationally related to national goals, a general pattern of microeconomic targets is decided upon, and particular industrial programs are worked out and implemented.

I think Hawley’s conception of industrial policy get it just right. Crucially, he clearly distinguished industrial policy from “policy” more generally. And he also specifies the requirement that “a planning and coordinating mechanism” is necessary and that targets are established.

This is why I always thought it would have been better had we long ago agreed to use the term “industrial planning” as opposed to “industrial policy.” Alas, that was never the case, nonetheless targeted and directed efforts to plan for specific future industrial outputs and outcomes is at the heart of a proper understanding of industrial policy. These are the limiting principles that allow us to continue to use the term in a rational way.

Returning to Caleb Watney’s essay then, I would suggest that he is abandoning the term industrial policy much too quickly. Moreover, he is simply shifting this controversy over to concepts like “tech policy” and “innovation policy.” Even if we sunset the use of industrial policy in policy discussions, we’ll still encounter the exact same definitional debates whenever those other terms becomes the new catchphrases.

I also disagree with how Caleb plots these terms on a Venn diagram. He has almost everything touched in some way by “industrial policy,” including what he thinks of as “innovation policy,” which is just one of many bubbles inside the bigger one.

I want to suggest the opposite framing: A more narrowly-defined conception of industrial policy actually fits inside a larger “innovation policy” bubble. Innovation Policy then incorporates many of those other things that some people put in the industrial policy bucket. But even then, I’m not sure I would not include things like climate policy or pandemic policy as inside that definition on a Venn diagram as I would other things, like trade policy and especially intellectual property policy.

Regardless of how we plot these things on Venn diagrams, I believe it crucial we adopt a far narrower understanding of industrial policy. If we cannot define it in such a fashion, then Caleb is right: the term really should be discarded altogether. But the problem is, it just won’t go away. Pundits and politicians will continue to use it regularly and, generally speaking, they will probably use it more along the lines of how I have defined it here. If we are going to have any sensible discussion about these things, we need to agree to a narrow reading of the term and stick with it. But I thank Caleb for expanding the discussion in a thought-provoking way. I encourage you to read his essay and continue the debate.

August 29, 2020

On Doctorow’s “Adversarial Interoperability”

Interoperability is a topic that has long been of interest to me. How networks, platforms, and devices work with each other–or sometimes fail to–is an important engineering, business, and policy issue. Back in 2012, I spilled out over 5,000 words on the topic when reviewing John Palfrey and Urs Gasser’s excellent book, Interop: The Promise and Perils of Highly Interconnected Systems.

I’ve always struggled with the interoperability issues, however, and often avoided them became of the sheer complexity of it all. Some interesting recent essays by sci-fi author and digital activist Cory Doctorow remind me that I need to get back on top of the issue. His latest essay is a call-to-arms in favor of what he calls “adversarial interoperability.” “[T]hat’s when you create a new product or service that plugs into the existing ones without the permission of the companies that make them,” he says. “Think of third-party printer ink, alternative app stores, or independent repair shops that use compatible parts from rival manufacturers to fix your car or your phone or your tractor.”

Doctorow is a vociferous defender of expanded digital access rights of many flavors and his latest essays on interoperability expand upon his previous advocacy for open access and a general freedom to tinker. He does much of this work with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which shares his commitment to expanded digital access and interoperability rights in various contexts.

I’m in league with Doctorow and EFF on some of these things, but also find myself thinking they go much too far in other ways. At root, their work and advocacy raise a profound question: should there be any general right to exclude on digital platforms? Although he doesn’t always come right out and say it, Doctorow’s work often seems like an outright rejection of any sort of property rights in networks or platforms. Generally speaking, he does not want the law to recognize any right for tech platforms to exclude using digital fences of any sort.

Where to Draw the Lines?

As someone who has authored a book about the importance of permissionless innovation, I need to be able to answer questions about where these lines between open versus closed systems are drawn. Definitions and framing matter, however. I use “permissionless innovation” as a descriptor for one possible policy disposition when considering where legal and regulatory defaults should be set. Another conception of permissionless innovation is more of an engineering ideal; a general freedom to connect, tinker, modify, etc. (I speak more about these conceptions in my latest book, Evasive Entrepreneurs.) Of course, someone advocating permissionless innovation as a policy default will sometimes be confronted with the question of what the law should say when someone behaves in an “evasive” fashion in the latter conception of permissionless innovation.

Doctorow would generally answer that question by saying that law should not be rigged to favor exclusion through laws like the DMCA (and specifically the law’s anti- circumvention provisions), Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, patent law, and various other rules and laws. “[T]he current crop of Big Tech companies has secured laws, regulations, and court decisions that have dramatically restricted adversarial interoperability.”

Generally speaking, I agree. I’m not a fan of technocratic laws or regulations that seek to micro-manage interoperability and which stack the deck in favor of exclusionary conduct with steep penalties for evasion. But does that mean adversarial interoperability should be permitted in all cases? Should there exist any sort of common law presumption one way or the other when a user or competitor seeks access to an existing private platform or device?

Specifics matter here and I don’t have time to get into all the case studies that Doctorow goes through. Some are no-brainers, like the infamous Lexmark case involving refillable printer ink cartridges. Other cases are far more complicated, at least for me. Does Epic, creator of Fortnite, have a right of adversarial interoperability that it can exercise against Apple and their AppStore? As Dirk Auer suggests in a new essay, this episode looks more like a straightforward pricing dispute. Epic is making it out to be much more than that, suggesting Apple is guilty of unfair and exclusionary practices that require a legal remedy.

Why not take that logic further and just say Apple’s App Store us tantamount to a natural monopoly or digital essential facility that Epic and everyone else is entitled to on whatever terms they want? For that matter, why not apply the same logic to Epic’s Fortnite platform or even its Unreal Engine? Does every other gaming developer have a right to piggyback on the juggernaut that Epic has built?

This gets to the core question about Doctorow’s concept of adversarial interoperability: Exactly what should common law and the courts say platform owners make access rights a simple pricing matter and say: “You pay or you are out.” Like Doctorow and EFF, I don’t want Apple to benefit from any special favors from laws like DMCA. Where we differ is that I would still leave the door open for Apple to exercise various other common law contractual rights or property rights in court.

I suspect Doctorow would deny any such claims by Apple or anyone else. If so, I would like to see him spell out in more precise terms exactly what Apple’s property rights and contractual rights are in this instance. Or, again, should we just treat the App Store as a digital commons with unfettered open access rights for developers? If so, would Apple be required to still manage the resource once it is a quasi-commons?

I think that would end miserably, but would like to hear Doctorow’s preferred approach before saying more. I suspect a lot rides on the distinction between “open” verses “proprietary” standards, but compared to Doctorow and EFF, I am willing to embrace a world of both open and proprietary systems, and many hybrids in between. I don’t want the law favoring one type over the other, but that means I need to endorse a generalized property right for digital operators such that they can still exclude others (even in the absence of artificial regulatory rights like DMCA creates). Again, I suspect Doctorow would reject that standard, preferring a generalized right of access, even if that means the platforms become de facto commons.

More Radical Steps

Elsewhere, Doctorow has said is that some of these questions would be better addressed through more aggressive antitrust regulation. Mere data portability or mandatory interoperability isn’t enough for him. “Data portability is important,” Doctorow says, “but it is no substitute for the ability to have ongoing access to a service that you’re in the process of migrating away from.”

In his latest online book on “How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism,” Doctorow suggests that it is time to “make Big Tech small again” through an “anti-monopoly ecology movement.” That “means bans on mergers between large companies, on big companies acquiring nascent competitors, and on platform companies competing directly with the companies that rely on the platforms.” And he desires a host of other remedies.

So, here we have the convergence of interoperability policy and antitrust policy, with a layer of property confiscation layered on top apparently. “Now it’s up to us to seize the means of computation, putting that electronic nervous system under democratic, accountable control,” he insists in his latest manifesto.

What’s funny about this is that Doctorow begins most of his essays by pointing out all the ways that politics is the problem when it comes to access issues, only to end by suggesting that a lot more political meddling is the required solution. He repeatedly laments how large tech players have so often been able to convince lawmakers and regulators to pass special laws or regulations that work to their favor. Yet, in his We-Can-Build-A-Better-Bureaucrat model of things, all those old problems will apparently disappear when we get the right people in power and get rid of those nefarious capitalist schemers.

Thus, what really animates Doctorow’s advocacy for adversarial interoperability is a deep suspicion of free market capitalism and property rights in particular. In this worldview, interoperability really just becomes a Trojan Horse meant to help bring down the entire capitalist order. Am I exaggerating? “As to why things are so screwed up? Capitalism.” Those are his exact words from the conclusion of his latest book.

Adversarial Innovation & Evolutionary Interop

Still, Doctorow raises many legitimate issues about interconnection and digital access rights. But we need a better approach to work though these questions than the one he suggests.

In my lengthy review of the Palfrey and Gasser Interop book, I tried to sketch out an alternative framework for thinking seriously about these issues. I referred to my preferred approach as “experimental interoperability” or “evolutionary interoperability.” I described this as the theory that ongoing marketplace experimentation with technical standards, modes of information production and dissemination, and interoperable information systems, is almost always preferable to the artificial foreclosure of this dynamic process through state action. The former allows for better learning and coping mechanisms to develop while also incentivizing the spontaneous, natural evolution of the market and market responses.

Adversarial interoperability is important, but not nearly as important as adversarial innovation and facilities-based competition. Stated differently, access rights to existing systems is an important value, but the incentives we have in place to encourage entirely new systems is what really matters most. At some point, a generalized right of access to existing systems discourages the sort of platform-building that could help give rise to the sort of creative destruction we have seen at work repeatedly in the past and that we still need today. Taken too far, adversarial interoperability threatens to undermine this goal. Why seek to build a better alternative platform if you can just endlessly free ride off someone else’s by force of law?

Thus, I prefer to work at the margins and think through how to balance these competing claims of access / interoperability rights versus contractual / property rights. My take will be too utilitarian for not only Doctorow but also for some libertarians, who want clear answers to all these questions based upon their preferred natural law-oriented constructions of rights. The problem with that approach is that it leads to all-or-nothing extremes (complete digital property rights, or virtually none) and that approach is fundamentally unworkable and destructive. We need to work harder about how to balance these rights and values in pro-competitive, pro-innovation fashion.

There is No Such Thing as Optimal Interoperability

In sum, there is no such thing as “optimal interoperablity.” Sometimes proprietary or “closed” systems will offer the public features and options that they will find preferable to “open” ones. “There are many reasons why consumers might prefer ‘closed’ systems – even when they have to pay a premium for them,” argues Dirk Auer in a separate essay. It could be greater convenience, security, or other things. Palfrey and Gasser correctly noted in their book that, “the state is rarely in a position to call a winner among competing technologies” (p. 174). Moreover, they concluded:

“Lawmakers need to keep in view the limits of their own effectiveness when it comes to accomplishing optimal levels of interoperability. Case studies of government intervention, especially where complex information technologies are involved, show that states tend to be ill suited to determine on their own what specific technology will be the best option for the future (p. 175)

A thousand amens to that! The law should not artificially foreclose experimentation with many different types of platforms, standards, devices and the interoperability that exists among them.

August 27, 2020

Symposium: Hirschman’s “Exit, Voice & Loyalty” at 50

[image error]This month’s Cato Unbound symposium features a conversation about the continuing relevance of Albert Hirschman’s Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, fifty years after its publication. It was a slender by important book that has influenced scholars in many different fields over the past five decades. The Cato symposium features a discussion between me and three other scholars who have attempted to use Hirschman’s framework when thinking about modern social, political, and technological developments.

My lead essay considers how we might use Hirschman’s insights to consider how entrepreneurialism and innovative activities might be reconceptualized as types of voice and exit. Response essays by Mikayla Novak, Ilya Somin, and Max Borders broaden the discussion to highlight how to think about Hirschman’s framework in various contexts. And then I returned to the discussion this week with a response essay of my own attempting to tie those essays together and extend the discussion about how technological innovation might provide us with greater voice and exit options going forward. Each contributor offers important insights and illustrates the continuing importance of Hirschman’s book.

I encourage you to jump over to Cato Unbound to read the essays and join the conversations in the comments.

August 8, 2020

The Conservative Crack-Up Over the Fairness Doctrine & FCC Regulation

There is a war going on in the conservative movement over free speech issues and FCC Commissioner Mike O’Reilly just became a causality of that skirmish. Neil Chilson and I just posted a new essay about this over on the Federalist Society blog. As we note there:

Plenty of people claim to favor freedom of expression, but increasingly the First Amendment has more fair-weather friends than die-hard defenders. Michael O’Rielly, a Commissioner at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), found that out the hard way this week.

Last week, O’Rielly delivered an important speech before the Media Institute highlighting a variety of problematic myths about the First Amendment, as well as “a particularly ominous development in this space.” In a previous political era, O’Rielly’s remarks would have been mainstream conservative fare. But his well-worded warnings are timely with many Democrats and Republicans – including some in the White House – looking to resurrect analog-era speech mandates and let Big Government reassert control over speech decisions in the United States.

Shortly after delivering his remarks, the White House yanked O’Rielly’s nomination to be reappointed to the agency. It was a shocking development that was likely motivated by growing animosities between Republicans on the question of how much control the federal government–and the FCC in particular–should exercise over speech platforms, including platforms that the FCC has no authority to regulate.

For the 30 years that I have been covering media and technology policy, I’ve heard conservatives rail against the Fairness Doctrine, Net Neutrality and arbitrary Big Government only to see many of them now reverse suit and become the biggest defenders of these things as it pertains to speech controls and FCC regulation. It will certainly be interesting to see what a potential future Biden Administration does with the various new regulations that some in the GOP are seeking to impose.

But all hope is not lost. There are still brave voices in Republican and conservative circles who continue to stand up the the First Amendment, freedom of speech, and limits on federal regulatory meddling with speech platforms and outcomes. Commissioner O’Reilly basically lost his job because he acted as the equivalent of an intellectual whistle-blower; he called out the ideological rot seen in recent statements and actions by the White House, Senator Josh Hawley, and many other Republicans.

There is nothing remotely “conservative” about calls for reinvigorating the Fairness Doctrine and FCC speech controls. That represents repressive regulation that betrays the First Amendment and which will ultimately backfire badly and come back to haunt conservatives down the road.

Read my new essay with Neil for more details. And down below I have listed all my recent writing on this topic.

Additional Reading:

“FCC’s O’Rielly on First Amendment & Fairness Doctrine Dangers“

“Sen. Hawley’s Radical, Paternalistic Plan to Remake the Internet“

“How Conservatives Came to Favor the Fairness Doctrine & Net Neutrality“

“Sen. Hawley’s Moral Panic Over Social Media“

“The White House Social Media Summit and the Return of ‘Regulation by Raised Eyebrow’“

“The Not-So-SMART Act“

“The Surprising Ideological Origins of Trump’s Communications Collectivism“

August 5, 2020

Existential Risk & Emerging Technology Governance

“The world should think better about catastrophic and existential risks.” So says a new feature essay in The Economist. Indeed it should, and that includes existential risks associated with emerging technologies.

The primary focus of my research these days revolves around broad-based governance trends for emerging technologies. In particular, I have spent the last few years attempting to better understand how and why “soft law” techniques have been tapped to fill governance gaps. As I noted in this recent post compiling my recent writing on the topic;

soft law refers to informal, collaborative, and constantly evolving governance mechanisms that differ from hard law in that they lack the same degree of enforceability. Soft law builds upon and operates in the shadow of hard law. But soft law lacks the same degree of formality that hard law possess. Despite many shortcomings and criticisms, compared with hard law, soft law can be more rapidly and flexibly adapted to suit new circumstances and address complex technological governance challenges. This is why many regulatory agencies are tapping soft law methods to address shortcomings in the traditional hard law governance systems.

I argued in recent law review articles as well as my latest book, despite its imperfections, I believe that soft law has an important role to play in filling governance gaps that hard law struggles to address. But there are some instances where soft law simply will not cut it. As I noted in Chapter 7 of my new book, there may be very legitimate existential threats out there that we should be spending more time addressing because the scope, severity, and probability of severe risk are present. Hard law solutions will still be needed in such instances, even if they may be challenged by many of the same factors that are fueling the shift toward soft law for other sectors or issues.

Of course, we are immediately confronted with a definitional challenge: What exactly counts as an “existential risk”? I argue that it is important that we spend more time discussing this question because far too many people today throw around the term “existential risk” when referencing risks that are noting of the sort. For example, increased social media use may indeed be a threat to data security and personal privacy, but those risks are not “existential” in the same way chemical or nuclear weapons proliferation are threats to our existence. This gets to the heart of the matter: the root of “existential” is existence. By definition, an existential risk needs to have some direct bearing on the future of humanity’s ability to survive. Efforts to conflate lesser risks into existential ones cheapen the very meaning of the term.

This shouldn’t be controversial, but somehow it is. Countless pundits today want to suggest that almost every new technological development might somehow pose an existential threat to humanity. But it just isn’t the case. That does not mean their concerns are not important, or potentially deserving of some government attention. It simply means that we need to take risk prioritization more seriously. If everything is an existential risk, than nothing is an existential risk. We must have some sort of ranking of risks if we hope to have a rational conversation about how to use scare societal resources to address matters of public concern.

These issues are discussed at far greater length in the sections of my book (pgs. 228-240) that you will find embedded down below. How should society deal with “killer robots” or the accelerated development of genetic editing capabilities? What kind of coordinated compliance regime might help address rouge actors who seek to use new technological capabilities for nefarious purposes? What can we learn from past global enforcement efforts for chemical and nuclear weapons? These are just some of the questions I take on in this section of the book and plan to spend more time addressing in coming years. Scan these pages from the book to see my initial thoughts on these matters. But I am really just scratching the surface here. I’ll have much more to say on these matters in coming months and years. It’s a massively complicated topic.

August 4, 2020

Wayne Brough Reviews “Evasive Entrepreneurs”

My thanks to Dr. Wayne Brough, President at Innovation Defense Foundation, for reviewing my new book, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance, over at the AIER website. Brough says of the book:

Adam Thierer has created a thoughtful and surprisingly timely book examining the interplay between entrepreneurs, innovation, and regulators. Thoughtful because he tackles tough questions of innovation and governance in a dynamic market. Timely because the coronavirus pandemic has forced policymakers to seriously reconsider the cumulative regulatory burden and how it may impede the economic recovery. Whether it’s V-shaped or a slower, longer recovery, decades worth of regulatory underbrush has taken its toll on economic activity while providing few, if any, benefits.

He also does a nice job summarizing the key theme of both this latest book and my previous one on Permissionless Innovation:

Thierer takes to task the anti-growth mentality and the political movements against innovation and growth, highlighting the long tradition of hostility toward innovation, from the early 19th-century Luddites up through today’s technophobes advocating restrictions on new technologies such as artificial intelligence. Much of this is driven by the precautionary principle, which Thierer views as an inappropriate guide for regulators. The precautionary principle is a highly risk-averse standard that provides regulators an excuse to stifle innovation for the slightest perceived hazard.

But Dr. Brough rightly takes me to task for not addressing intellectual property issues in either book. He’s right. I did indeed chicken out of bringing IP policy into these books for a variety of reasons. After I co-edited a big book on IP wars in 2002 (Copy Fights), I made so many enemies for trying to walk the moderate middle path that I largely abandoned the field forevermore. I just got tired of the Holy Wars fought over the topic, and every time I tried to play the role of peacemaker in those wars, I just got shot at by both sides in the intellectual crossfire. I was simultaneously being accused of being an “IP anarchist” and “a whore for Big Content,” by people on either side of those wars. At one point, a board member of the Cato Institute suggested I should be removed from my job for not being enough of an IP opponent while, at the exact same time, a Cato adjunct fellow was suggesting I was already far too radical of an IP opponent. I certainly couldn’t be both! It was comical, but also exhausting and incredibly frustrating. And so I raised the white flag of surrender and walked off the IP battlefield around 2005.

But I also did not bring IP policy into either of my latest books simply because I needed to pick my battles and focus on the issues I know best. When you go down the IP rabbit hole, there’s no escaping that endless descent. Both books would have needed to be significantly longer to incorporate nuanced discussions of how copyright and patents affect innovation outcomes.

Regardless, I very much understand the concerns that Dr. Brough raises in his review about how, “the efficacy of intellectual property laws is inextricably tied to innovation, for better or worse,” and how, “[s]ome of the most disruptive innovation has occurred in the shadow of intellectual property laws that still struggle to keep pace with the rate of technological change.” He’s correct, and entire books have been written on the topic… including my old one!

Anyway, you can read the opening chapter of my new book here, or buy the entire thing here. And my thanks again to Wayne Brough for taking the time to read and review it.

July 31, 2020

Latest Soft Law Development: DoT’s NETT Council Report

On July 23rd, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) released Pathways to the Future of Transportation, which was billed as “a policy document that is intended to serve as a roadmap for innovators of new cross modal technologies to engage with the Department.” This guidance document was created by a new body called the Non-Traditional and Emerging Transportation Technology (NETT) Council, which was formed by U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao last year. The NETT Council is described as “an internal deliberative body to identify and resolve jurisdictional and regulatory gaps that may impede the deployment of new technologies.”

On July 23rd, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) released Pathways to the Future of Transportation, which was billed as “a policy document that is intended to serve as a roadmap for innovators of new cross modal technologies to engage with the Department.” This guidance document was created by a new body called the Non-Traditional and Emerging Transportation Technology (NETT) Council, which was formed by U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao last year. The NETT Council is described as “an internal deliberative body to identify and resolve jurisdictional and regulatory gaps that may impede the deployment of new technologies.”

The creation of NETT Council and the issuance of its first major report highlight the continued growth of “soft law” as a major governance trend for emerging technology in the US. Soft law refers to informal, collaborative, and constantly evolving governance mechanisms that differ from hard law in that they lack the same degree of enforceability. A partial inventory of soft law methods includes: multistakeholder processes, industry best practices or codes of conduct, technical standards, private certifications, agency workshops and guidance documents, informal negotiations, and education and awareness efforts. But this list of soft law mechanisms is amorphous and ever-changing.

Soft law systems and processes are multiplying at every level of government today: federal, state, local, and even globally. Such mechanisms are being tapped by government bodies today to deal with fast-moving technologies that are evolving faster than the law’s ability to keep up.

The US Department of Transportation has become a leading candidate for Soft Law Central at the federal level. The agency has been tapping a variety of soft law mechanisms and approaches to deal with driverless cars and drone policy issues in particular. (See the essays listed down below for more details).

The NETT Council represents the next wave of this governance trend. We might consider it an effort to bring a greater degree of formality and coordination to the agency’s soft law efforts. The DoT’s overview of the NETT Council explains its purpose as follows:

Inventors and investors approach USDOT to obtain necessary safety authorizations, permits, and funding and often face uncertainty about how to coordinate with the Department. The NETT Council will address these challenges by ensuring that the traditional modal silos at DOT do not impede the safe deployment of new technology. Furthermore, it will give project sponsors a single point of access to discuss plans and proposals.

In its new guidance document, the NETT Council seeks to outline how it will work to develop “the principles informing the [DoT] policies in transformative technologies,” as well as “the overarching regulatory framework for non-traditional and emerging transportation technologies.” A lot of stress is placed on “how the Council will engage with innovators and entrepreneurs” to strike the balance between continued safety and increased innovation.

Although much of the document simply discusses existing agency regulatory authority, the Council also identifies how the agency and its subdivisions will seek a more flexible governance approach going forward. A premium is placed on expanding dialogue among affected parties. The section discussing environmental review requirements is indicative of this, noting: “The Department encourages innovators, project sponsors or proponents to engage in a dialogue with the NETT Council when the proponent anticipates seeking Federal financial assistance or an authorization.”

“Any innovator can approach the NETT Council with its ideas,” the document says in another section, although engagement level may vary by issue and department. It continues on to note that, “during the formation stage, the NETT Council would likely be willing to have an informational meeting and establish a point of contact to maintain a level of awareness for Department staff regarding the new project.” “Successful collaboration tends to be characterized by industry initiation and leadership with a limited and defined federal role,” it notes. Several examples are highlighted.

In addition to the importance of early dialogue between innovators and regulators, the document stresses the dangers associated with regulatory uncertainty. It also includes some discussion about the problems associated with a lack of regulatory flexibility in some instances “and the potential deterrent to innovation caused by attempting to ‘shoehorn’ a particular technology into a regulatory regime that does not fit.” There is also some discussion of how international or private sector standards might help provide governance solutions in some instances.

Again, these are all examples of soft law mechanisms. To be clear, the NETT Council is not proposing the abandonment of hard law enforcement efforts. To the contrary, the document repeatedly reiterates what those powers are and how they might be used. But it is equally clear that the DoT realizes that the old regulatory systems are being severely strained by the “pacing problem,” or the notion that technological developments are often moving considerably faster than traditional regulatory processes.

The NETT Council report is a welcome effort to broaden the dialogue about what sort of governance systems might make the more sense going forward for emerging technologies. This is a pressing problem for the DoT because of the convergence of digital and analog sectors and technologies. AI and machine-learning technologies are invading the crusty old world of transportation networks and regulations. Momentous changes are happening. Law will need to adapt. Soft law systems will increasingly be tapped to help out if for no other reason than there isn’t a better backup plan. If America hopes to be a leader in transportation innovation, new governance approaches will be essential.

Below you will find some additional essays on the growing soft law-ization of technological governance in the US. Many of them are about transportation technologies and recent developments at the federal and state levels. I also recommend this new essay by John Villasenor over at Brookings on “Soft law as a complement to AI regulation.” Finally, if you want to do a deep dive in the nature of soft law and the full range of governance issues associated with it, then you absolutely must follow the work being done by Gary Marchant and his impressive team of colleagues at Arizona State University. Begin with this essay on “Soft Law Governance Of Artificial Intelligence,” and then get your hands on this huge book on the topic that Marchant co-edited. It’s the best thing I have read on soft law and alternative governance systems for emerging technologies.

In the meantime, give the new DoT NETT Council report a glance because, for better or worse, this is what the future of technological governance looks like.

__________________

Adam Thierer, “ Soft Law in ICT Sectors: A Brief History ,” forthcoming Jurimetrics, (2021).

Ryan Hagemann, Jennifer Skees, and Adam D. Thierer, “ Soft Law for Hard Problems: The Governance of Emerging Technologies in an Uncertain Future ,” Colorado Technology Law Journal, (2018).

Ryan Hagemann, Jennifer Huddleston Skees & Adam Thierer, “‘Soft Law’ Is Eating the World: Driverless Car Edition,” The Bridge, Oct 11, 2018

Jennifer Huddleston & Trace Mitchell, “ Continuing DOT’s Automated Vehicle Soft-Law Approach Will Encourage Innovation and Promote Safety ,” Mercatus Center Public Comment, November 30, 2018.

Jennifer Huddleston & Adam Thierer, “ Pennsylvania’s Innovative Approach to Regulating Innovation ,” The Bridge, September 5, 2018.

Ryan Hagemann, “ New Rules for New Frontiers: Regulating Emerging Technologies in an Era of Soft Law ,” Washburn Law Journal, Vol. 57, No. 2 (Spring 2018).

Adam Thierer, “The Pacing Problem and the Future of Technology Regulation,” The Bridge, August 8, 2018.

July 29, 2020

Can Biohacking & DIY Citizen Science Help Find a COVID Vaccine?

In an amazing new MIT Technology Review piece, Antonio Regalado discusses how, “Some scientists are taking a DIY coronavirus vaccine, and nobody knows if it’s legal or if it works.” It is another powerful example of how “citizen-science” and medical self-experimentation (or “biohacking”) is increasingly being used to improve health outcomes, enhance human capabilities, or fight against deadly diseases like COVID. Regalado reports that:

Nearly 200 covid-19 vaccines are in development and some three dozen are at various stages of human testing. But in what appears to be the first “citizen science” vaccine initiative, Estep and at least 20 other researchers, technologists, or science enthusiasts, many connected to Harvard University and MIT, have volunteered as lab rats for a do-it-yourself inoculation against the coronavirus. They say it’s their only chance to become immune without waiting a year or more for a vaccine to be formally approved.

Among those who’ve taken the DIY vaccine is George Church, the celebrity geneticist at Harvard University, who took two doses a week apart earlier this month. The doses were dropped in his mailbox and he mixed the ingredients himself.

Regalado notes that this is all happening despite legal and ethical questions:

By distributing directions and even supplies for a vaccine, though, the Radvac group is operating in a legal gray area. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires authorization to test novel drugs in the form of an investigational new drug approval. But the Radvac group did not ask the agency’s permission, nor did it get any ethics board to sign off on the plan.

Chapter 2 of my latest book (Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance) features a discussion of DIY health efforts, citizen-science and biohacking. Average citizens are using new technological capabilities to address health needs, often beyond the confines of the law. Here’s the beginning of that discussion, which starts on p. 79 of the manuscript:

DIY health services and medical devices are on the rise thanks to the combined power of open-source software, 3D printers, cloud computing, and digital platforms that allow information sharing between individuals with specific health needs. Average citizens are using these new technologies to modify their bodies and abilities, often beyond the confines of the law.

Welcome to the occasionally scary but oftentimes awe-inspiring world of biohacking. Biohackers are essentially “prosumers,” the term many used a decade ago to describe the way average citizens were taking advantage of new communications and computing technologies to become both producers and consumers of news, information, and entertainment. Pro-sumers evaded traditional industry norms and government regulations that had previously made it difficult for citizens to communicate freely. The same phenomenon is now shaking up the world of health and medicine as pro-sumers use new technological capabilities to take their health into their own hands and likely evade many traditional norms and regulations when doing so.

In other words, we can’t just put the genie back in the bottle with sweeping, repressive regulatory controls. Here’s an essay that Jordan Reimschisel and I wrote last year on “Biohacking, Democratized Medicine, and Health Policy” highlighting the many thorny policy issues in play here, as well as possible governance responses.

In another essay, Jordan and I argued that one of the most important and constructive policy responses would be stepped-up risk education and health literacy initiatives. We need constructive approaches to citizen-science and biohacking to make sure we address serious risks but simultaneously avoid blocking beneficial forms of health and medical innovation that our country desperately needs, especially at this time.

July 28, 2020

Some Recent Essays on the Importance of Innovation & the Fight over Technological Progress

I was speaking at a virtual conference recently and was discussing my life’s work, which for 30 years has been focused on the importance of innovation and intellectual battles over what we mean progress. I whipped up a short list of some things I have written over just the past 5 years on this topic and thought I would just re-post them here:

UNDERSTANDING THE CHALLENGE WE FACE:

The Radicalization of Modern Tech Criticism

Is It ‘Techno-Chauvinist’ & ‘Anti-Humanist’ to Believe in the Transformative Potential of Technology?

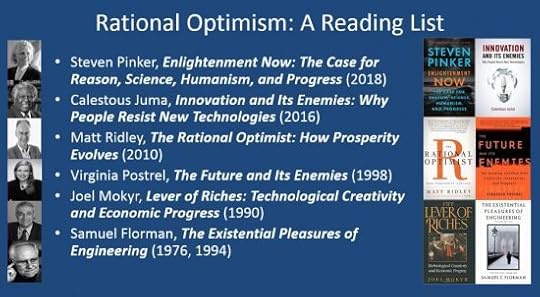

HOW WE MUST RESPOND = “Rational Optimism” / Right to Earn a Living / Permissionless Innovation

How To Defend a Culture of Innovation During the Technopanic

How Technology Expands the Horizons of Our Humanity

Deep Technologies & Moonshots: Should We Dare to Dream?

The Right to Pursue Happiness, Earn a Living, and Innovate

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom

ADDITIONAL READING:

Is There a Science of Progress?

Technological Innovation and Economic Growth: A Brief Report on the Evidence

5 Books that Shaped My Thinking on Innovation

Innovation and the Trouble with the Precautionary Principle

NEW BOOK (tying together all the essays and papers listed above):

Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance: How Innovation Improves Economies and Governments

Evasive Entrepreneurs vs. Ridiculous Liquor Rules

Few things unify people in America more than beer and liquor regulations. On one side you have the forces of repression, who either favor strong liquor taxes and regulations on moralistic grounds, or because they favor curtailing competition and choice for a variety of reasons. On the other side you have those of us looking to end the insanity of quasi-Prohibitionary rules that do nothing to boost public health but do plenty to annoy the living hell out of us (and cost us plenty). And the really interesting thing is that these two groups contain plenty of people of radically different political persecutions. Liquor regulations are the greatest destroyer of political partisanship ever!

Few things unify people in America more than beer and liquor regulations. On one side you have the forces of repression, who either favor strong liquor taxes and regulations on moralistic grounds, or because they favor curtailing competition and choice for a variety of reasons. On the other side you have those of us looking to end the insanity of quasi-Prohibitionary rules that do nothing to boost public health but do plenty to annoy the living hell out of us (and cost us plenty). And the really interesting thing is that these two groups contain plenty of people of radically different political persecutions. Liquor regulations are the greatest destroyer of political partisanship ever!

For those of us who favor liberalization, as I write in my latest AIER column:

The good news is that evasive entrepreneurs and an increasingly technologically-empowered public will keep pushing back and hopefully whittle away at the continuing vestiges of Prohibition Era stupidity. Where there’s a will, there’s a way, and when people want a drink, crafty entrepreneurs will usually find a way to deliver.

I talk a walk back through history and discuss how efforts to evade ridiculous liquor controls have been a longstanding feature of the American experience. People can be remarkably creative when seeking to circumvent silly rules–both before, during, and after Prohibition. Indeed, the insanity continues today. I document several examples of how:

In the wake of the COVID lockdowns, some state and local governments relaxed liquor carryout and delivery laws to give bars, breweries, and distilleries a chance to weather the forced closings. Unfortunately, many of those laws also required those establishments to sell food as part of every transaction if they wanted to sell or serve drinks. The results were comical in many states as evasive entrepreneurs devised creative regulatory work-arounds to deal with these “gotta-eat-to-drink” edicts.

I provide examples of this happening in Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, and DC with dumb rules like that. Finally, I also come clean about my own bootlegger past! Read on.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower