Adam Thierer's Blog, page 8

July 12, 2021

Is the FTC’s Antitrust Enforcement Still Focused on Consumers?

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) voted on July 1 to withdraw its pubic affirmation of consumer welfare as the guiding principle for antitrust enforcement. While this change is symbolic at this point, it weakens the agency’s public commitment to an objective consumer-based approach to antitrust. The result opens the door to politicized and unprincipled antitrust enforcement that will ultimately hurt rather than benefit consumers.

The FTC is the nation’s primary consumer protection agency, focused on ensuring a healthy market that avoids the dangers of monopolistic practices. The statement on the agency’s antitrust enforcement had been uncontroversial up to this point. A bipartisan group of commissioners passed the statement in 2015—during the Obama Administration—and the statement primarily clarified that the FTC’s antitrust enforcement under Section 5 of the FTC Act concerning the agency’s authority over unfair and deceptive trade practices was guided by consumer welfare. In other words, the FTC would focus on those acts that cause or are likely to cause harm to consumers, based on objective economic analysis rather than the effects of business moves on competition itself or other policy standards. The statement sought to provide clarity to consumers and businesses, and in fact, the sole vote against it was on the basis that the statement was too abbreviated to provide meaningful guidance.

Despite these uncontroversial origins, on Thursday at a hastily announced open meeting, the current FTC voted 3-2 to withdraw this statement. The withdrawal of the FTC’s statement is the latest signal that antitrust policy, particularly at the FTC, is shifting away from focusing on consumers and using the consumer welfare standard. Instead, there are now real concerns the FTC will enforce antitrust policy in a way that promotes competitors or ideology at consumers’ expense.

Most specifically, rejecting the consumer welfare standard signals the FTC may apply its enforcement power in more subjective ways based in changing political motives and policy preference, as was seen in earlier eras of antitrust enforcement. For example, if not focused on the consumer welfare standard, the FTC could act against some of the largest tech companies to break them up or prevent mergers even though consumers were not harmed—or were even helped—by these changes in the market. This shift would have three specific, if related, implications.

First, it would undermine confidence among consumers in the FTC’s actions. It is far less clear now by what standards antitrust enforcement will be guided and if they are truly objective. As a result, it is unclear what the purpose behind enforcement is.

Second, such expansive enforcement could diminish the options available to consumers. Without the consumer welfare standard, aggressive antitrust enforcement could lead to regulatory interventions in competitive and dynamic markets apart from a data-based and consumer-focused analysis. The result of such unnecessary enforcement could be to raise costs or eliminate products, preventing consumers from having access to products they enjoy or face higher prices, not because of unfair or anti-competitive behavior but because of political animus against a particular industry.

Finally, this shift away from the consumer welfare standard is likely to result in inefficient markets. Unprincipled or politically motivated enforcement could result in some products and services never making it to consumers. In other cases, markets may find certain “competitors” kept alive past their value, or other markets could remain with few choices because companies fear that entrance would be considered anticompetitive. Without the consumer welfare standard, misguided notions of concentration or “bigness” could result in a less beneficial market and instead benefit competitors with inferior products that would not have otherwise survived—all to the detriment of consumers.

When regulators move away from an objective, consumer-focused approach to antitrust, it is ultimately the consumers who are harmed in the form of higher prices, inferior products, and less innovation. As Commissioner Christine Wilson stated prior to the vote, “If the Commission is no longer focused on consumer welfare then consumers will be harmed.”

June 29, 2021

Remembering the ‘Japan Inc.’ Industrial Policy Scare of the 1980s & 1990s

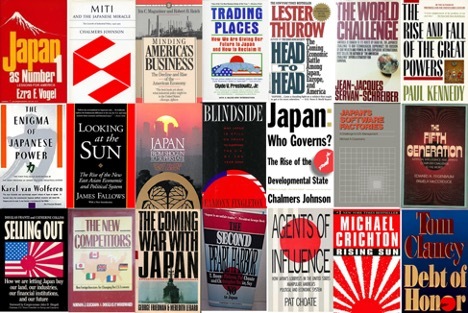

Discourse magazine has just published my latest essay, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse.” It is a short history of the hysteria surrounding the growth of Japan in the 1980s and early 1990s and its various industrial policy efforts. I begin by noting that, “American pundits and policymakers are today raising a litany of complaints about Chinese industrial policies, trade practices, industrial espionage and military expansion. Some of these concerns have merit. In each case, however, it is easy to find identical fears that were raised about Japan a generation ago.” I then walk through many of the leading books, opeds, movies, and other things from that past era to show how that was the case.

“Hysteria” is not too strong a word to use in this case. Many pundits and politicians were panicking about the rise of Japan economically and more specifically about the way Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) was formulating industrial policy schemes for industrial sectors in which they hoped to make advances. This resulted in veritable “MITI mania” here in America. “U.S. officials and market analysts came to view MITI with a combination of reverence and revulsion, believing that it had concocted an industrial policy cocktail that was fueling Japan’s success at the expense of American companies and interests,” I note. Countless books and essays were being published with breathless titles and predictions. I go through dozens of them in my essay. Meanwhile, the debate in policy circles and Capitol Hill even took on an ugly racial tinge, with some lawmakers calling the the Japanese “leeches.” and suggesting the U.S. should have dropped more atomic bombs on Japan during World War II. At one point, several members of Congress gathered on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol in 1987 to smash Japanese electronics with sledgehammers.

All this hysteria about Japan and MITI bore little semblance to reality. In fact, as I note in the essay, the MITI industrial planning model fell apart after it made a host of horrible bad bets and the stock market tanked in the late 1980s. Corruption also became a huge problem within many state-led efforts. A 2000 report by the Policy Research Institute within Japan’s Ministry of Finance concluded that “the Japanese model was not the source of Japanese competitiveness but the cause of our failure.” MITI was renamed the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry at about the same time, and its mission shifted more toward market-oriented reforms.

In fact, as I note in the essay, the MITI industrial planning model fell apart after it made a host of horrible bad bets and the stock market tanked in the late 1980s. Corruption also became a huge problem within many state-led efforts. A 2000 report by the Policy Research Institute within Japan’s Ministry of Finance concluded that “the Japanese model was not the source of Japanese competitiveness but the cause of our failure.” MITI was renamed the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry at about the same time, and its mission shifted more toward market-oriented reforms.

Industrial policy came to be viewed as a bit of a joke in America after that, but now it is back with a vengeance, thanks largely to the rise of Chinese economic power. Thus, because “we hear echoes from the Japan Inc. era debates in today’s policy discussions about China and industrial policy planning,” I end my essay with some lessons from the ‘Japan Inc.’ era for today’s industrial policy debates:

This similarity demonstrates the first lesson we can learn from the previous era: It is important to separate serious geopolitical and economic analysis from breathless fear-mongering and borderline xenophobia. The former has a serious place in policy discussions; the latter needs to be called out and shunned. After all, there are many legitimate worries about rising Chinese power, particularly when it involves Chinese Communist Party efforts to squash human rights domestically or to engage in industrial espionage, trade mercantilism and military adventurism abroad. Separating serious matters from trivial or imaginary ones is crucial, especially to help keep peace between nations. Avoiding hysteria is especially pertinent today with a wave of anti-Asian sentiment and attacks on the rise in the U.S.

A second lesson from the Japan Inc. experience relates to today’s renewed interest in industrial policy: Forecasting the future of nations and economies—and trying to plan for it—is a tricky business. A huge range of variables affects global competitiveness and technological advancement. A nonexhaustive list of some of the most important factors would include legal and political stability, physical and intellectual property rights, tax burdens, competition policy, trade and investment laws, monetary policy, research and development efforts, and even demographic factors and access to certain natural resources. Understanding how these and other factors all work together is an inexact science. When targeted industrial policy mechanisms are added to the mix, it becomes even harder to untangle which variables are making the most difference.

Both in the past and today, a less visible group of scholars has suggested that an embrace of entrepreneurialism and free trade was the fundamental factor driving Japanese economic expansion in the past and China’s amazing growth today. Openness to markets, they say, drove the enormous economic expansions—which also happened during times of much-needed catch-up modernization in both countries. But these perspectives have usually been shouted out of the room by louder voices, who either bombastically blast or praise industrial policy mechanisms as the prime mover in the economic rejuvenation of both nations.

We need to tamp down on the magical thinking that governments can easily achieve technological innovation and economic growth by simply spinning a few industrial policy gauges. A few big bets may pay off, but that doesn’t justify governments engaging in casino economics regularly. History more often shows that grandiose industrial policy schemes simply result in cost overruns, cronyism and even corruption.

I also conclude by noting that:

Perhaps the most ironic indictment of industrial policy punditry lies in the way all the earlier books and essays about Japanese planning not only failed to forecast the many flops associated with it, but also did not foresee China as a potential future economic juggernaut. Korea, Singapore and Taiwan were mentioned as potential Asian challengers, but no one gave China much consideration. What might that tell us about the ability of experts to predict the future course of countries and economies? It is a reminder of the wisdom of another great Yogi Berra quote: “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

You can read the entire piece, as well as several others listed below, over at Discourse.

________________________

Recent writing on industrial policy:Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Does the US Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for AI & High-Tech?” Presentation for IHS Papers Workshop: Does America Need a New Industrial Policy?, forthcoming, July 23, 2021.Adam Thierer, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse,” Discourse, June 28, 2021.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.Matthew D. Mitchell and Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea,” Discourse, April 6, 2021.Adam Thierer, “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy,'” Technology Liberation Front, September 3, 2020.June 25, 2021

How a Section 230 Repeal Could Mean ‘Game Over’ for the Gaming Community

By: Jennifer Huddleston and Juan Martin Londoño

This year the E3 conference streamed live over Twitch, YouTube, and other online platforms—a reality that highlights the growing importance of platforms and user-generated content to the gaming industry. From streaming content on Twitch, to sharing mods on Steam Workshop, or funding small developing studios on services such as Patreon or Kickstarter, user-generated content has proven vital for the gaming ecosystem. While these platforms have allowed space for creative interaction—which we saw on the livestreams chats during E3—the legal framework that allows all of this interaction is under threat, and changes to a critical internet law could spell Game Over for user-created gaming elements.

This law, “Section 230,” is foundational to all user-generated content on the internet. Section 230 protects platforms from lawsuits over both the content they host as well as their moderation decisions, giving them the freedom to curate and create the kind of environment that best fits its customers. This policy is under attack, however, from policymakers on both sides of the aisle. Some Democrats argue platforms are not moderating enough content, thus allowing hate speech and voter suppression to thrive, while some Republicans believe platforms are moderating too much, which promotes “cancel culture” and the limitation of free speech.

User-generated content and the platforms that host it have contributed significantly to the growth of the gaming industry since the early days of the internet. This growth has only accelerated during the pandemic, as in 2020 the gaming industry grew 20 percent to a whopping $180 billion market. But changing Section 230 could seriously disrupt user-generated engagement with gaming, making content moderation costlier and riskier for some of gamers’ favorite platforms.

An increased legal liability could mean a platform such as Twitch would face higher compliance costs due to the need to increase its moderation and legal teams. This cost would likely be transferred to creators through a revenue reduction or to viewers through rate hikes—resulting in less content and fewer users. Further, restrictions on moderation could lead to undesirable content and ultimately fewer users and advertisers—leading to more profit losses and less content. Ultimately, platforms might not be able to sustain themselves, leading to fewer platforms and opportunities for fans to engage. Platforms such as Twitch already face these problems, but for now they can determine the best solutions without heavy-handed government intervention or costly legal battles.

The impact of changing Section 230 goes beyond video content and could impact some increasingly popular fan creations that are further invigorating the industry. For example, the modding community, composed of gaming fans that modify existing games to create new experiences, often uses various online platforms to share their mods with other players. Modding has kept certain games relevant even years after their release, or propelled games’ popularity by introducing new ways to play them. Such is the case of Grand Theft Auto V’s roleplaying mod, or Arma III’s PlayerUnknown Battlegrounds mod, the inspiration of games such as Fortnite and Call of Duty: Warzone.

These modified games are often hosted on platforms such as Steam Workshop, Github, or on independently run community websites. These platforms are often free of charge, either as a complimentary service of a bigger product – in the case of Steam – or are supported purely by ad revenue and donations. Like streaming platforms and message boards, without Section 230 these services would face increased compliance costs or be unable to remove excessively violent, sexually explicit, or hateful content. The result could be that these new twists on old favorites never make it to consumers, as platforms are unable to host these creations and remain viable as businesses.

Changing or removing Section 230 protections would upend the complex and dynamic gaming environment on display during E3. It took decades of growth for gaming to establish itself as the new king of entertainment and it has defended itself from a variety of technopanics throughout the years. Pulling the plug on Section 230 could mean “Game Over” for the user-generated content that brings gamers so much fun.

June 17, 2021

Innovation policy in Arizona

I write about telecom and tech policy and have found that lawmakers and regulators are eager to learn about new technologies. That said, I find that good tech policies usually die of neglect as lawmakers and lobbyists get busy patching up or growing “legacy” policy areas, like public pensions, income taxes, Medicare, school financing, and so forth. So it was a pleasant surprise this spring to see Arizona lawmakers prioritize and pass several laws that anticipate and encourage brand-new technologies and industries.

Flying cars, autonomous vehicles, telehealth–legislating in any one of these novel legal areas is noteworthy. New laws in all of these areas, plus other tech areas, as Arizona did in 2021, is a huge achievement and an invitation to entrepreneurs and industry to build in Arizona.

Re: AVs and telehealth, Arizona was already a national leader in autonomous vehicles and Gov. Ducey in 2015 created the first (to my knowledge) statewide AV task force, something that was imitated nationwide. A new law codifies some of those executive orders and establishes safety rules for testing and commercializing AVs. Another law liberalizes and mainstreams telehealth as an alternative to in-person doctor visits.

A few highlights about new Arizona laws on legal areas I’ve followed more closely:

Urban air mobility and passenger dronesArizona lawmakers passed a law (HB 2485) creating an Urban Air Mobility study committee. 26 members of public and private representatives are charged with evaluating current regulations that affect and impede the urban air mobility industry and making recommendations to lawmakers. “Urban air mobility” refers to the growing aviation industry devoted to new, small aircraft designs, including eVTOL and passenger drones, for the air taxi industry. Despite the name, urban air mobility includes intra-city (say, central business district to airport) aviation as well as regional aviation between small cities.

The law is well timed. The US Air Force is giving eVTOL aircraft companies access to military airspace and facilities this year, in part to jumpstart the US commercial eVTOL industry, and NASA recently released a new study (PDF) about regional aviation and technology. NASA and the FAA last year also endorsed the idea of urban air mobility corridors and it’s part of the national strategy for new aviation.

The federal government partnering with cities and state DOTs in the next few years to study air taxis and to test the corridor concept. This Arizona study committee might be to identify possible UAM aerial corridors in the state and cargo missions for experimental UAM flights. They could also identify the regulatory and zoning obstacles to, say, constructing or retrofitting a 2-story air taxi vertiport in downtown Phoenix or Tucson.

Several states have drone advisory committees but this law makes Arizona a trailblazer nationally when it comes to urban air mobility. Very few states have made this a legislative priority: In May 2020 Oklahoma law created a task force to examine autonomous vehicle and passenger drones. Texas joined Oklahoma and Arizona on this front–this week Gov. Abbot signed a similar law creating an urban air mobility committee.

Smart corridor and broadband infrastructure constructionInfrastructure companies nationwide are begging state and local officials to allow them to build along roadways. These “smart road” projects include installing 5G antennas, fiber optics, lidar, GPS nodes, and other technologies for broadband or for connected and autonomous vehicles. To respond to that trend, Arizona passed a law (HB 2596) on May 10 that allows the state DOT–solely or via public-private partnership–to construct and lease out roadside passive infrastructure.

In particular, the new law allows the state DOT to construct, manage, and lease out passive “telecommunication facilities”–not simply conduit, which was allowed under existing law. “Telecommunication facilities” is defined broadly:

Any cable, line, fiber, wire, conduit, innerduct, access manhole, handhole, tower, hut, pedestal, pole, box, transmitting equipment, receiving equipment or power equipment or any other equipment, system or device that is used to transmit, receive, produce or distribute by wireless, wireline, electronic or optical signal for communication purposes.

The new Section 28-7383 also allows the state to enter into an agreement with a public or private entity “for the purpose of using, managing or operating” these state-owned assets. Access to all infrastructure must be non-exclusive, in order to promote competition between telecom and smart city providers. Access to the rights-of-way and infrastructure must also be non-discriminatory, which prevents a public-private partner from favoring its affiliated or favored providers.

Leasing revenues from private companies using the roadside infrastructure are deposited into a new Smart Corridor Trust Fund, which is used to expand the smart corridor network infrastructure. The project also means it’s easier for multiple providers to access the rights-of-way and roadside infrastructure, making it easier to deploy 5G antennas and extend fiber backhaul and Internet connectivity to rural areas.

It’s the most ambitious smart corridor and telecom infrastructure deployment program I’ve seen. There have been some smaller projects involving the competitive leasing of roadside conduit and poles, like in Lincoln, Nebraska and a proposal in Michigan, but I don’t know of any state encouraging this statewide.

For more about this topic of public-private partnerships and open-access smart corridors, you can read my law review article with Prof. Korok Ray: Smart Cities, Dumb Infrastructure.

Legal protections for residents to install broadband infrastructure on their propertyFinally, in May, Gov. Ducey signed a law (HB 2711) sponsored by Rep. Nutt that protects that resembles and supplements the FCC’s “over-the-air-reception-device” rules that protect homeowner installations of wireless broadband antennas. Many renters and landowners–especially in rural areas where wireless home Internet makes more sense–want to install wireless broadband antennas on their property, and this Arizona law protects them from local zoning and permitting regulations that would “unreasonably” delay or raise the cost of installation of antennas. (This is sometimes called the “pizza box rule”–the antenna is protected if it’s smaller than 1 meter diameter.) Without this state law and the FCC rules, towns and counties could and would prohibit antennas or fine residents and broadband companies for installing small broadband and TV antennas on the grounds that the antennas are an unpermitted accessory structure or zoning violation.

The FCC’s new 2021 rules are broader and protect certain types of outdoor 5G and WiFi antennas that serve multiple households. The Arizona law doesn’t extend to these “one-to-many” antennas but its protections supplement those FCC rules and clearer than FCC rules, which can directly regulate antennas but not town and city officials. Between the FCC rules and the Arizona law, Arizona households and renters have new, substantial freedom to install 5G and other wireless antennas on their rooftops, balconies, and yard poles. In rural areas especially this will help get infrastructure and small broadband antennas installed quickly on private property.

Too often, policy debates by state lawmakers and agencies are dominated by incremental reforms of longstanding issues and established industries. Very few states plant the seeds–via policy and law–for promotion of new industries. Passenger drones, smart corridors, autonomous vehicles, and drone delivery are maturing as technologies. Preparing for those industries signals to companies and their investors that innovation, legal clarity, and investment is a priority for the state. Hopefully other states will take Arizona’s lead and look to encouraging the industries and services of the future.

June 3, 2021

Podcast on Economic Liberty & the Right to Earn a Living

I was my pleasure to appear on the latest episode of the Dissed podcast to discuss economic liberty and the right to earn a living. The show was hosted by Anastasia Boden and Elizabeth Slattery of the Pacific Legal Foundation and it included legal scholars Hadley Arkes, Timothy Sandefur, and Clark Neily. I appear in the second half of the program.

I’ve spent many years writing about the relationship between innovation, entrepreneurialism, economic liberty, and the right to earn a living. My latest book (Evasive Entrepreneurs) and previous one (Permissionless Innovation) devoted considerable attention to this. But I tried to bring it all down to just a few hundred words in my 2018 essay, “The Right to Pursue Happiness, Earn a Living, and Innovate.”

I’ve reprinted that down below, but please make sure to click over to the Dissed page and listen to that excellent podcast.

________________

The Right to Pursue Happiness, Earn a Living, and Innovate

by Adam Thierer

[originally appeared on The Bridge, September 20, 2018]

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

That memorable line from America’s Declaration of Independence makes it clear that we are at liberty to pursue lives of our own choosing. Our path in this world is ours to make. It is not predestined by government.

It is time to think more expansively about the right to pursue happiness. Specifically, it is time we acknowledge that our freedom to pursue happiness is the basis of many other corresponding rights, including the right to innovate and the right to earn a living.

Our right to pursue happiness aligns with our corresponding rights to speak, learn, and move about the world. Our constitutional heritage secured these rights and made it clear that we possess them simply by nature of being human beings. So long as we do not bring harm to others, we are generally free to act as we wish. These rights also serve as the basis of more specific freedoms: the freedom to tinker and try, or to innovate more generally.

Knowledge isn’t a mere collection of words that have existed since the dawn of time, and growth isn’t merely a matter of luck or destiny. Knowledge comes from acts of trial-and-error experimentation, and growth comes from innovation.

Repressing innovation has profound consequences. When critics decry a particular innovation or propose limiting entrepreneurial acts, they are challenging our freedom to know and learn more about the world and pursue a better future. By challenging our freedom to experiment with new and better ways of doing things, critics are essentially condemning us to the status quo.

Worse yet, denying people the freedom to innovate deprives society of the wisdom and prosperity that accompanies innovation, which is the foundation of human flourishing.

In sum, if you are not free to innovate, you are not free to pursue happiness.

So, let us resolve to clearly establish that the freedom to pursue happiness and the freedom to innovate are, in reality, the exact same right. Our freedom to try, to tinker, to learn, and to know are all just the same as our “freedom to innovate” and our freedom to pursue happiness however we see fit to pursue it.

Fostering a social and political culture that protects entrepreneurialism, the freedom to innovate, and the right earn a living is a moral imperative because it has enormous consequences for the well-being of current and future generations. To the extent this freedom is denied, the burden of proof—and the consequences for this denial—lies with those critics who would wish it so.

April 17, 2021

Conservatives & Common Carriage: Contradictions & Challenges

Over at Discourse magazine I’ve posted my latest essay on how conservatives are increasingly flirting with the idea of greatly expanding regulatory control of private speech platforms via some sort of common carriage regulation or new Fairness Doctrine for the internet. It begins:

Conservatives have traditionally viewed the administrative state with suspicion and worried about their values and policy prescriptions getting a fair shake within regulatory bureaucracies. This makes their newfound embrace of common carriage regulation and media access theory (i.e., the notion that government should act to force access to private media platforms because they provide an essential public service) somewhat confusing. Recent opinions from Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as well as various comments and proposals of Sen. Josh Hawley and former President Trump signal a remarkable openness to greater administrative control of private speech platforms.

Given the takedown actions some large tech companies have employed recently against some conservative leaders and viewpoints, the frustration of many on the right is understandable. But why would conservatives think they are going to get a better shake from state-regulated monopolists than they would from today’s constellation of players or, more importantly, from a future market with other players and platforms?

I continue on to explain why conservatives should be skeptical of the administrative state being their friend when it comes to the control of free speech. I end by reminding conservatives what President Ronald Reagan said in his 1987 veto of legislation to reestablish the Fairness Doctrine: “History has shown that the dangers of an overly timid or biased press cannot be averted through bureaucratic regulation, but only through the freedom and competition that the First Amendment sought to guarantee.”

Read more at Discourse, and down below you will find several other recent essays I’ve written on the topic.

“FCC’s O’Rielly on First Amendment & Fairness Doctrine Dangers““A Good Time to Re-Read Reagan’s Fairness Doctrine Veto““Sen. Hawley’s Radical, Paternalistic Plan to Remake the Internet““How Conservatives Came to Favor the Fairness Doctrine & Net Neutrality““Sen. Hawley’s Moral Panic Over Social Media““The White House Social Media Summit and the Return of ‘Regulation by Raised Eyebrow’““The Not-So-SMART Act““The Surprising Ideological Origins of Trump’s Communications Collectivism“April 13, 2021

A Return of the Trustbusters Could Harm Consumers

Is it a time for the return of the trustbusters? Some politicians seem to imply that today’s tech giants have become modern day robber barons taking advantage of the American consumer and, as a result, they argue that it is time for a return of aggressive antitrust enforcement and for dramatic changes to existing antitrust interpretations to address the concerns associated with today’s big business.

This criticism is not limited to one side of the aisle, with Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Josh Hawley (R-MO) both proposing their own dramatic overhauls of antitrust laws and the House Judiciary Committee majority issuing a report that greatly criticizes the current technology market. In both cases these new proposals create presumptive bans on mergers for companies of certain size and lower the burdens on the government for intervening and proving its case. I have previously analyzed the potential impact of Senator Klobuchar’s proposal, and Senator Hawley’s proposal raises many similar concerns when it comes to its merger ban and shift away from existing objective standards.

Proponents on both sides of the aisle argue changing current antitrust standards is needed to fight big business, but sadly these modern-day trustbusters may not be the heroes they see themselves as. In fact, such a shift would harm American consumers and small businesses well beyond the tech sector.

The Trustbusters-Era Standards Would Fail Consumers

The original trustbusters of the late 19th and early 20th century created a system that was not always clear and could be abused by regulators subjectively determining what was and was not anti-competitive behavior. The result was that, in this earlier era, businesses and consumers could never be certain what behaviors would be considered violations.

The shift to the consumer welfare standard helped fixed that problem by providing an objective framework using economic analysis to weigh the risk and benefits of behavior and judging it based on its impact on consumers and not specific competitors. Unfortunately, these new proposals would shift away from this objective focus and return to a presumption that big is bad. This shift would be bad news not only for big business but for smaller businesses and consumers as well. Small businesses would lose an important exit strategy option with the presumptive ban on mergers with large companies, and consumers would miss out on benefits such as price reductions, improvements, and innovations that these mergers could bring.

While much of the debate around antitrust changes focuses on large tech firms such as Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon, changing antitrust laws would impact far more of the economy than just tech. Both the Hawley and Klobuchar proposals would bar mergers unless there is strong evidence proving their value (a “regulatory presumption” against mergers), but this presumption would impact industries such as pharmaceuticals, finance, and agriculture that also frequently have mergers and acquisitions that benefit consumers by helping to expand the distribution of a product or improve on an existing service. In fact, companies including L’Oreal and Nike could find any mergers or acquisitions presumptively prohibited under the limits in these proposals.

Existing Standards Can Adapt to Dynamic Markets Like Tech

Existing standards are still able to address the concerns associated with this dynamic and changing markets as well as more established markets. For example, the Antitrust Modernization Commission concluded, “There is no need to revise the antitrust laws to apply different rules to industries in which innovation, intellectual property, and technological change are central features.”

Sometimes regulators’ sense of the market in technology may prove to be wrong by the evolution of a technology or the disruption caused by a dramatic shift in the industry. For example, debates used to be focused on MySpace and AOL , which have now become things of internet nostalgia. Today’s tech giants are facing growing challenges not only from each other in many cases, but also from many newer entrants, from ClubHouse and TikTok to Zoom and Shopify. Removing the need to firmly establish the existing standards of an antitrust case would risk unnecessary intervention into the market or, more likely, could prevent actions that benefit consumers.

Some question whether this economic analysis-based standard can handle the zero-price services offered by many technology companies. While price is often the easiest focus, this standard also considers issues such as quality and innovation, making it elastic enough to address potential concerns even if the price is zero. Still, this does not mean that the definition of harm under the consumer welfare standard should be expanded to address any litany of concerns that cannot be objectively shown to have market harm.

Trustbusters’ Concerns with Tech Are Unlikely to Be Solved by Antitrust

Antitrust is also a poor tool to address concerns such as data privacy or content moderation, and using it to do so could allow for future abuse for other political ends. There is no guarantee that smaller companies would respond to existing market demands around issues such as content moderation any differently than the current large players. Additionally, when it comes to privacy and targeted advertising, smaller platforms would have to find new ways to gain revenue and might be forced to monetize the platform more to stay afloat without being able to rely on the revenue from a larger parent company. Finally, there is no guarantee that these smaller companies would be more innovative or dynamic particularly as existing teams and talents are divided by break ups and walls are erected to prevent entry into certain markets.

The good news is some policymakers have realized that these problems exist and argued for preserving the existing framework and addressing these other concerns with appropriately targeted policies. For example, Sen. Mike Lee recently defended the consumer welfare standard and was critical of the negative impact “radically alter[ing] our antitrust regime” could have while still questioning some recent decisions around content moderation.

Conclusion

Many have hoped for a return of bipartisan cooperation in Washington, but unfortunately bad ideas can also emerge on both sides of the aisle. Shifting away from the consumer welfare standard would ultimately harm consumers at a time when innovation and economic recovery are especially critical.

April 8, 2021

Targeting vs. Generality in Economic Development & Industrial Policy

Over at Discourse magazine, my Mercatus Center colleague Matt Mitchell and I have a new essay on, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea.” We argue that, despite having a long history of disappointments and failures, that isn’t stopping many policymakers from proposing it industrial policies again. We compare national industrial policy efforts alongside state-based economic development policies, noting their many similarities. In both cases, the crucial issue comes down to targeting versus generality in terms of how policymakers go about encouraging innovation and economic growth. We note how:

The building blocks of the general approach—a mix of broadly applicable tax, spending, regulatory and legal rules—are often rejected because they seem less exciting than targeting specific companies or industries for help. Pundits and policymakers are fond of using machine-like metaphors to suggest they can “fine-tune” innovation or “dial-in” economic development according to a precise formula they believe they have concocted. They also savor the attention that goes along with ribbon-cutting ceremonies and the big headlines often generated by political targeting efforts.

We discuss the spectrum of economic development options (depicted in chart below) in more detail and explain the many pitfalls associated with some of the most highly targeted efforts. “The predicament for policymakers is that, while it is wiser to focus on the generalized approaches, the temptation will remain strong to jump to targeted gambles that may grab headlines but are far more risky and costly,” we argue. Head over to Discourse to read the entire thing.

March 29, 2021

Another NFT Explainer

I don’t understand the hype surrounding Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). As someone who has studied copyright and technology issues for years, maybe because it doesn’t seem very new to me. It’s just a remixing of some ideas and technologies that have been around for decades. Let me explain.

For at least 100 years, “ownership” of real property has been thought of as a “bundle of rights.” As a simple example, you may “own” the land your house sits on, but the city probably has a right to build and maintain a sidewalk across your yard and the general public has a right to walk across your property on that sidewalk. The gas company has the right to walk into your side yard to read your gas meter. Pilots have a right to fly over your house. Some other company or companies may have rights to any water and minerals in the ground below your house. Your homeowners association may even have a right to dictate what color you paint the exterior of your house.

This same “bundle of rights” concept also applies to copyright. Unless explicitly granted by contract, buying an original painting doesn’t mean you have the right to take a photograph of the painting and sell prints of the photograph. If you buy a DVD, you have the right to watch the DVD privately and you have the right to sell the DVD when you’re no longer interested in it. (That second right is called the “first sale doctrine” and there have been numerous Supreme Court cases and laws defining it’s exact boundaries.) But unless explicitly granted by contract, purchasing a DVD doesn’t mean you have the right to set up a projector and big screen and charge members of the public to watch it. That requires a “public performance” right.

When you buy most NFTs, you get very few of the rights that typically come with ownership. You might only get the right to privately exhibit the underlying work. And if you decide to later resell the NFT, the contract (which is embedded in digital code of the NFT) may stipulate that the original artist gets a 10% royalty on every future sale of the work.

The second thing you need to understand is the concept of “artificial scarcity.” As a simple example, in the art world, it’s common for photographers and painters to sell numbered, “limited edition” prints of their works. There’s no technological reason why they couldn’t print 1,000 copies of their work, or even register the print with a “print on demand” service that will continue making and selling prints as long as there are people who want to buy them. But limiting the number of prints made (even if each print is identical to any other print), is likely to raise the price. This is artificial scarcity. Most NFTs are an edition of one. Even if there are other exact copies of the underlying artwork sold as NFTs, each NFT is unique. This is like an artist selling numbered prints but not putting a limit on how many numbered prints they make. Each numbered print is technically unique because each has a different number. But without some artificial scarcity, the value of any one print may stay very low.

So if buying a NFT doesn’t get you any real rights and the scarcity is purely artificial, why are NFTs selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars? Here’s where all the technology really makes a difference. If you spend millions on a Picasso painting, you’re taking a lot of risks. First, you’re taking the risk that it’s a forgery, which would drop the value to near-zero. Second is the risk that the painting will be stolen from you. Insurance can help deal with both problems, but that adds more complications. If you’re buying the painting as an investment, these complications reduce the “liquidity” of the asset. Liquidity is the ease with which an asset can be converted into cash without affecting the market value of the asset. Put more simply, liquidity is how easily the asset can be sold. Cash has long been considered the most liquid asset, but NFTs are arguably much /more/ liquid than cash. NFTs don’t require anything physical to trade hands. And even electronic currency transfers take time and are subject to government oversight. NFTs are so new, they’re barely regulated. But by using blockchain technology, they can be easily and safely bought and sold anonymously. NFTs are a money launderers dream. It’s unclear if NFTs are actually being used to launder money, but it’s a concern.

The other reason I think NFTs are so popular is speculation. Because NFTs are so liquid and because there basically doesn’t even need to be an underlying work, the initial cost to “mint” (create) a NFT is near zero. And by using blockchain systems, NFTs can be resold with little overhead. (Though they can also be configured to ensure a certain overhead, e.g. that 10% of every resale goes to the original artist.) These characteristics, along with the newness of NFTs make it a popular marketplace for speculators, people who purchase assets with the intent of holding them for only a short time and then selling them for a profit.

NFTs started to enter the public consciousness in February 2021, after the 10-year old “Nyan cat” animation sold for over half a million dollars. This is also just a few weeks after the Gamestop stock short squeeze made a compelling case that average investors, working in concert, could upset the stock market and make millions. So it’s no wonder that there is rampant speculation in NFTs.

In conclusion, NFTs will be a tremendous benefit to digital artists, who did not previously have a way to easily prove the authenticity of their works (which is of tremendous importance to investors) or to provide a digital equivalent to numbered prints in the physical art world. But the hype about NFTs is just that. It’s driven by speculators and you’d be crazy to think of this as a worthy investment opportunity.

March 25, 2021

Thoughts on Content Moderation Online

Content moderation online is a newsworthy and heated political topic. In the past year, social media companies and Internet infrastructure companies have gotten much more aggressive about banning and suspending users and organizations from their platforms. Today, Congress is holding another hearing for tech CEOs to explain and defend their content moderation standards. Relatedly, Ben Thompson at Stratechery recently had interesting interviews with Patrick Collison (Stripe), Brad Smith (Microsoft), Thomas Kurian (Google Cloud), and Matthew Prince (Cloudflare) about the difficult road ahead re: content moderation by Internet infrastructure companies.

I’m unconvinced of the need to rewrite Section 230 but like the rest of the Telecom Act—which turned 25 last month–the law is showing its age. There are legal questions about Internet content moderation that would benefit from clarifications from courts or legal scholars.

(One note: Social media common carriage, which some advocates on the left, right, and center have proposed, won’t work well, largely for the same reason ISP common carriage won’t work well—heterogeneous customer demands and a complex technical interface to regulate—a topic for another essay.)

The recent increase in content moderation and user bans raises questions–for lawmakers in both parties–about how these practices interact with existing federal laws and court precedents. Some legal issues that need industry, scholar, and court attention:

Public Officials’ Social Media and Designated Public ForumsDoes Knight Institute v. Trump prevent social media companies’ censorship on public officials’ social media pages?

The 2nd Circuit, in Knight Institute v. Trump, deemed the “interactive space” beneath Pres. Trump’s tweets a “designated public forum,” which meant that “he may not selectively exclude those whose views he disagrees with.” For the 2nd Circuit and any courts that follow that decision, the “interactive space” of most public officials’ Facebook pages, Twitter feeds, and YouTube pages seem to be designated public forums.

I read the Knight Institute decision when it came out and I couldn’t shake the feeling that the decision had some unsettling implications. The reason the decision seems amiss struck me recently:

Can it be lawful for a private party (Twitter, Facebook, etc.) to censor members of the public who are using a designated public forum (like replying to President Trump’s tweets)?

That can’t be right. We have designated public forums in the physical world, like when a city council rents out a church auditorium or Lions Club hall for a public meeting. All speech in a designated public forum is accorded the strong First Amendment rights found in traditional public forums. I’m unaware of a case on the subject but a court is unlikely to allow the private owner of a designated public forum, like a church, to censor or dictate who can speak when its facilities are used as a designated public forum.

The straightforward implication from Knight Institute v. Trump seems to be that neither politicians nor social media companies can make viewpoint-based decisions about who can comment on or access an official’s social media account.

Knight Institute creates more First Amendment problems than it solves, and could be reversed someday. But to the extent Knight Institute v. Trump is good law, it seems to limit how social media companies moderate public officials’ pages and feeds.

Cloud neutralityHow should tech companies, lawmakers, and courts interpret Sec. 512?

Wired recently published a piece about “cloud neutrality,” which draws on net neutrality norms of nondiscrimination towards content and applies them to Internet infrastructure companies. I’m skeptical of the need or constitutionality of the idea but, arguably, the US has a soft version of cloud neutrality embedded in Section 512 of the DMCA.

The law conditions the copyright liability safe harbor for Internet infrastructure companies only if:

the transmission, routing, provision of connections, or storage is carried out through an automatic technical process without selection of the material by the service provider.

Perhaps a copyright lawyer can clarify, but it appears that Internet infrastructure companies may lose their copyright safe harbor if they handpick material to censor. To my knowledge, there is no scholarship or court decision on this question.

State ActionWhat evidence would a user-plaintiff need to show that their account or content was removed due to state action?

Most complaints of state action for social media companies’ content moderation are dubious. And while showing state action is hard to prove, in narrow circumstances it may apply. The Supreme Court test has said that when there is a “sufficiently close nexus between the State and [a] challenged action,” the action of a private company will be treated as state action. For that reason, content removals made after non-public pressure or demands from federal and state officials to social media moderators likely aren’t protected by the First Amendment or Section 230.

Most examples of federal and state officials privately jawboning social media companies will never see the light of day. However, it probably occurs. Based on Politico reporting, for instance, it appears that state officials in a few states leaned on social media companies to remove anti-lockdown protest events last April. It’s hard to know exactly what occurred in those private conversations, and Politico has updated the story a few times, but examples like that may qualify as state action.

Any public official who engages in non-public jawboning resulting in content moderation could also be liable to a Section 1983 claim–civil liability for deprivation of an affected user’s constitutional rights.

Finally, what should Congress do about foreign state action that results in tech censorship in the US? A major theme of the Stretechery interviews ist that many tech companies feel pressure to set their moderation standards based on what foreign governments censor and prohibit. Content removal from online services because of foreign influence isn’t a First Amendment problem, but it is a serious free speech problem for Americans.

Many Republicans and Democrats want to punish large tech companies for real or perceived unfairness in content moderation. That’s politics, I suppose, but it’s a damaging instinct. For one thing, the Section 230 fixation distract free-market and free-speech advocates from, among other things, alarming proposals for changes to the FEC that empower it to criminalize more political speech. The singular focus on Section 230 repeal-reform distracts from these other legal questions about content moderation. Hopefully the Biden DOJ or congressional hearings will take some of these up.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower