Adam Thierer's Blog, page 6

May 2, 2022

New Report: “Governing Emerging Technology in an Age of Policy Fragmentation and Disequilibrium”

[image error]The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) has kicked off a new project called “Digital Platforms and American Life,” which will bring together a variety of scholars to answer the question: How should policymakers think about the digital platforms that have become embedded in our social and civic life? The series, which is being edited by AEI Senior Fellow Adam J. White, highlights how the democratization of knowledge and influence in the Internet age comes with incredible opportunities but also immense challenges. The contributors to this series will approach these issues from various perspectives and also address different aspects of policy as it pertains to the future of technological governance.

It is my honor to have the lead paper in this new series. My 19-page essay is entitled, Governing Emerging Technology in an Age of Policy Fragmentation and Disequilibrium, and it represents my effort to concisely tie together all my writing over the past 30 years on governance trends for the Internet and related technologies. The key takeaways from my essay are:

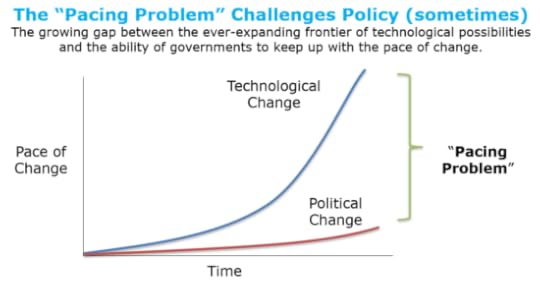

Traditional governance mechanisms are being strained by modern technological and political realities. Newer technologies, especially digital ones, are developing at an ever-faster rate and building on top of each other, blurring lines between sectors.Congress has failed to keep up with the quickening pace of technological change. It also continues to delegate most of its constitutional authority to agencies to deal with most policy concerns. But agencies are overwhelmed too. This situation is unlikely to change, creating a governance gap.Decentralized governance techniques are filling the gap. Soft law—informal, iterative, experimental, and collaborative solutions—represents the new normal for technological governance. This is particularly true for information sectors, including social media platforms, for which the First Amendment acts as a major constraint on formal regulation anyway.No one-size-fits-all tool can address the many governance issues related to fast-paced science and technology developments; therefore, decentralized governance mechanisms may be better suited to address newer policy concerns.My arguments will frustrate many people of varying political dispositions because I adopt a highly pragmatic approach to technological governance. No matter what your preferred ideal state of affairs looks like in terms of technological governance, you’re bound to be disappointed by the way high-tech policy is unfolding today. Many people desire bright-letter hard law that has government(s) establishing comprehensive, precautionary regulation of various tech sectors. Others prefer a clearly defined but more light-touch policy regime for emerging technology. Alas, neither of these preferred hard law dispositions describe the world we live in today, nor will either of them likely govern the future. My essay outlines a variety of reasons why such hard law approaches are breaking down today, including general legislative dysfunctionalism, the endless delegation of power from Congress to regulatory agencies or the states, and the the intensifying “pacing problem” (i.e., the fact that technological change is happening at a must faster rate than policy change).

In light of this, I argue:

it is smart to think practically about alternative governance frameworks when traditional hard-law approaches prove slow or ineffective in addressing governance needs. It is also wise to consider alternative governance frameworks that might address the occasional downsides of disruptive technologies without completely foreclosing ongoing innovation opportunities the way many hard-law solutions would.

I also show that, whether anyone cares to admit it or not, we already live in a world of multiplying “soft law” mechanisms and decentralized governance approaches. I use the example of how these new governance trends are unfolding for autonomous vehicles, but note how we see decentralized governance approaches being utilized in many other sectors. This is equally true across the Atlantic where the United Kingdom is increasingly experimenting with new governance approached for emerging technologies.

What counts as “soft law” or “decentralized governance” is an open-ended and ever-changing topic of discussion. But I note that it, at a minimum, it includes: multi-stakeholder processes, experimental “sandboxes,” industry best practices or codes of conduct, technical standards, private certifications, agency workshops and guidance documents, informal negotiations, and education and awareness building efforts. I unpack these ideas in the essay in more detail.

For social media, soft law approaches are the current governance norm, even as hard law regulatory proposals continue to multiply rapidly. But I note that despite all that pressure for more formal regulatory governance of social media platforms, the First Amendment presents a formidable barrier to most of those proposals. Thus, soft law will continue to be the dominant governance approach here. I also conclude by predicting that that soft law will become the dominant approach for artificial intelligence, too, even as regulatory proposals multiply there as well.

I’ll have more to say about my paper and other papers in the AEI series in coming weeks and month. For now, I encourage you to jump over to the website AEI has set up for the series and take a look at my new paper.

_____________________________

Additional Reading :

Ryan Hagemann, Jennifer Huddleston Skees, and Adam Thierer, “Soft Law for Hard Problems: The Governance of Emerging Technologies in an Uncertain Future,” Colorado Technology Law Journal 17 (2018): 37–130, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3118539.Adam Thierer, “Soft Law in U.S. ICT Sectors: Four Case Studies,” Jurimetrics 61, no. 1 (Fall 2020): 79–119, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3777490.Adam Thierer, “Congress as a Non-Actor in Tech Policy,” Medium, February 4, 2020, https://medium.com/@AdamThierer/congress-as-a-non-actor-in-tech-policy-5f3153313e11.Adam Thierer, “The Pacing Problem and the Future of Technology Regulation,” Bridge, August 8, 2018, https://www.mercatus.org/bridge/commentary/pacing-problem-and-future-technology-regulation.Adam Thierer, “Artificial Intelligence Governance in the Obama–Trump Years,” IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, Vol, 2, Issue 4, (2021), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4013880.Adam Thierer, “Left and Right Take Aim at Big Tech—and the First Amendment,” Hill, December 8, 2021, https://thehill.com/opinion/technology/584874-left-and-right-take-aim-at-big-tech-and-the-first-amendment.Adam Thierer, “The Classical Liberal Approach to Digital Media Free Speech Issues,” Technology Liberation Front, December 8, 2021, https://techliberation.com/2021/12/08/the-classical-liberal-approach-to-digital-media-free-speech-issues.Adam Thierer, “The Great Deplatforming of 2021,” Discourse, January 14, 2021, https://www.discoursemagazine.com/politics/2021/01/14/the-great-deplatforming-of-2021.May 1, 2022

The Future of Progress Studies

If you haven’t yet had the chance to check out the new Progress Forum, I encourage you to do so. It’s a discussion group for progress studies and all things related to it. The Forum is sponsored by The Roots of Progress. Even though the Forum is still in pre-launch phase, there are already many interesting threads worth checking out. I was my honor to contribute one of the first on the topic, “Where is ‘Progress Studies’ Going?” It’s an effort to sort through some of the questions and challenges facing the Progress Studies movement in terms of focus and philosophical grounding. I thought I would just reproduce the essay here, but I encourage you to jump over to the Progress Forum to engage in discussion about it, or the many other excellent discussions happening there on other issues.

________________

Where is “Progress Studies” Going?

by Adam Thierer

What do we mean by “Progress Studies” and how can this field of study be advanced? I’ve been thinking about that question a lot since Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen published their 2019 manifesto in The Atlantic on why “We Need a New Science of Progress.” At present, there is no overarching “unified field theory” of what Progress Studies entails or what underpins it, and that may be holding up progress on Progress Studies. I recently attended an important conference on the “Moral Foundations of Progress Studies,” co-hosted by The Roots of Progress and the Salem Center at UT Austin, where I discovered that many others were grappling with these same issues.

While a broad range of people are interested in Progress Studies, their moral priors differ, sometimes significantly. For example, the UT Austin conference included scholars from diverse disciplines (philosophy, psychology, economics, political science, history, and others) whose thinking was rooted in different philosophical traditions (utilitarianism, effective altruism, individualism, and various hybrids). Everyone shared the goal of advancing human well-being, but participants had different conceptions of the moral foundations of well-being, and even some disagreement about what well-being meant in concrete terms. There were also differing perspectives about what the “studies” part of Progress Studies should entail. Specifically, does it include progress advocacy, including the potential for specific policy recommendations?

Comprehension vs. AdvocacyPart of the confusion over the nature and goals of Progress Studies can be traced back to Collison and Cowen’s foundational essay. On one hand, their goal was progress comprehension. “Progress itself is understudied,” Collison and Cowen argued. They lamented that “there is no broad-based intellectual movement focused on understanding the dynamics of progress.”

But Collison and Cowen went further. Their goal was not merely to inspire the development of a field of study that could give us a better understanding of the prerequisites of progress, but also to formulate a plan for advancing progress. They argued that “mere comprehension is not the goal,” and advocated for “the deeper goal of speeding it up.” They went on to say, “the implicit question is how scientists [and others] should be acting” and that Progress Studies should be viewed as, “closer to medicine than biology: The goal is to treat, not merely to understand.” The presupposition here is that progress is important and that we need to take steps to get a lot more of it. Again, we can think of this part of Progress Studies as progress advocacy. And advocacy can entail both advocating for progress generally as well as specific types of policy advocacy.

This raises an interesting question we debated at the UT Austin conference: Can you study something and advocate for it at the same time? Some felt you really cannot separate them, while others believed that the broader questions about how progress has worked could be kept separate from any advocacy efforts. Of course, this same tension between comprehension and advocacy comes up in many other fields.

What Progress Studies Can Learn from STSIn this sense, Progress Studies might learn some important lessons by examining the older but loosely related field of Science and Technology Studies (STS). STS incorporates a wide variety of mostly “soft science” academic disciplines, such as law, philosophy, sociology, and anthropology. These scholars analyze the relationship between technology, society, culture, and politics.

One conclusion from studying STS is obvious: comprehension and advocacy frequently get blurred. Many of the STS scholars who engage in critical studies of the history of technology seamlessly transition into anti-technology advocates, even as many of them claim they are “just studying” the issues. As I’ve noted elsewhere:

When thinking about of technology, STS scholars commonly employ words like “anxiety,” “alienation,” “degradation,” and “discrimination.” Consequently, most of them suggest that the burden of proof lies squarely on scientists, engineers, and innovators to prove that their ideas and inventions will bring worth to society before they are deployed. In other words, STS scholars generally fall in the precautionary principle camp, and their policy prescriptions have grown increasingly radical over time.

Meanwhile, as I discussed in my latest book, many STS scholars describe themselves as “humanists” while implicitly suggesting that those who promote technological progress are somehow callous oafs who only care about the cold calculus of profit-seeking and creating shiny new gadgets we don’t need.

While some STS scholars continue to do important and largely objective work, many others routinely show their more radical leanings in books, essays, and social media posts. Most worrying is their newfound love of Luddism, as they spin revisionist histories of “Why Luddites Matter,” insisting that “There’s Nothing Wrong with Being a Luddite,” and that “I’m a Luddite. You Should Be One Too.” Neil Richards, a law professor and leading STS scholar declares bluntly on Twitter: “Less metaverse, less crypto, less disruptive innovation. More regulation, more ethics, more humanity.” In other words, public policy defaults should be set squarely to the Precautionary Principle and anyone opposed to that is unethical and anti-human. Taken to the extreme, STS scholars marry up this Luddite revisionism with the retrograde philosophy of “degrowth” and produce book chapters with titles like, “Methodological Luddism: A Concept for Tying Degrowth to the Assessment and Regulation of Technologies.”

The Progress Studies movement might consider framing its work as a response to the growing extremism of the STS movement. STS scholars have become so remarkably hostile to the very notion that science and technology are central to human advancement that the field might today better be labeled Anti-Science & Technology Studies. Yet, these are the scholars that dominate many academic departments where students are learning about technological progress. Progress Studies scholars can push back against that radicalism and offer level-headed, empirical responses to it.

Ensuring A Big TentTo improve its chances of success, the Progress Studies movement should seek to broaden its appeal by avoiding a dogmatic party line on its moral foundations while ensuring that multiple disciplines and viewpoints are incorporated into it.

In terms of philosophical underpinnings, those interested in Progress Studies can take different approaches to the moral foundations of progress and human well-being. Many philosophers get frustrated when others fail to hammer out all the detailed nuances of the metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics of these matters. I understand that urge, but I’ve now spent over 30 years covering technology policy and have been constantly surprised about how many people can come together and agree on a broad set of principles about the importance of progress without sharing a common philosophical framework.

The same is true as it pertains to policy prescriptions. We need to ensure a “big tent” in this way, too. It is already the case that many people engaged in Progress Studies have very different perspectives on issues like intellectual property and industrial policy, for example. I have many friends on different sides of these issues. Importantly, there are not even clear sides on these issues but rather a very broad spectrum of viewpoints. Progress Studies scholars will likely always disagree on the finer points of both types of “IP” policy. Nonetheless, they can remain more unified in stressing the common goal of moving the needle on progress in a positive direction and highlighting the continuing importance of flexible experimentation with policies aimed at enhancing innovation and growth.

To the extent there is any litmus test for the Progress Studies movement, that’s it: advancing opportunities for innovation and growth is paramount. Regardless of how one grounds their moral philosophy, or goes about constructing a theory of rights, many people can agree that granting humans the freedom to explore, experiment, and be entrepreneurial has important benefits for individuals, families, organizations, and entire nations. Openness to change is what unifies us. Stagnation and “steady state” thinking—and the Precautionary Principle-based policies that flow from such reasoning—are the enemy.

Thus, the Progress Studies movement can focus on both studying progress and advancing it at the same time, even if some will devote more effort to one priority than the other. And we shouldn’t forget that these two objectives are reinforcing: Comprehension informs advocacy and vice-versa. Progress is a never-ending process of trial-and-error. It’s all about learning by doing. We try, we fail, we learn, and we try again. This is as true for the individuals attempting to make progress in the real-world as it is for scholars studying it and seeking to promote it.

Let us get on with this important work, regardless of what motivates us to do it.

April 29, 2022

“Building Again” Must Be More than Just Rhetoric

As I note in my latest regular column for The Hill, it seems like everyone these days is talking about the importance of America “building again.” For example, take a look at this compendium of essays I put together where scholars and pundits have been making the case for “building again” in various ways and contexts. It would seem that the phrase is on everyone’s lips. “These calls include many priorities,” I note, “but what unifies them is the belief that the nation needs to develop new innovations and industries to improve worker opportunities, economic growth and U.S. global competitive standing.”

What I fear, however, is that “building again” has become more of a convenient catch line than anything else. It seems like few people are willing to spell out exactly what it will take to get that started. My new column suggests that the most important place to start is “to cut back the thicket of red tape and stifling bureaucratic procedures that limit the productiveness of the American workforce.” I cite recent reports and data documenting the enormous burden that regulatory accumulation imposes on American innovators and workers. I then discuss how to get reforms started at all levels of government to get the problem under control and help us start building again in earnest. Jump over to The Hill to read the entire essay.

April 26, 2022

Book Review: “Questioning the Entrepreneurial State”

An important new book launched this week in Europe on issues related to innovation policy and industrial policy. “Questioning the Entrepreneurial State: Status-quo, Pitfalls, and the Need for Credible Innovation Policy” (Springer, 2022) brings together more than 30 scholars who contribute unique chapters to this impressive volume. It was edited by Karl Wennberg of the Stockholm School of Economics and Christian Sandström of the Jönköping (Sweden) International Business School.

An important new book launched this week in Europe on issues related to innovation policy and industrial policy. “Questioning the Entrepreneurial State: Status-quo, Pitfalls, and the Need for Credible Innovation Policy” (Springer, 2022) brings together more than 30 scholars who contribute unique chapters to this impressive volume. It was edited by Karl Wennberg of the Stockholm School of Economics and Christian Sandström of the Jönköping (Sweden) International Business School.

As the title of this book suggests, the authors are generally pushing back against the thesis found in Mariana Mazzucato’s book The Entrepreneurial State (2011). That book, like many other books and essays written recently, lays out a romantic view of industrial policy that sees government as the prime mover of markets and innovation. Mazzucato calls for “a bolder vision for the State’s dynamic role in fostering economic growth” and innovation. She wants the state fully entrenched in technological investments and decision-making throughout the economy because she believes that is the best way to expand the innovative potential of a nation.

The essays in Questioning the Entrepreneurial State offer a different perspective, rooted in the realities on the ground in Europe today. Taken together, the chapters tell a fairly consistent story: Despite the existence of many different industrial policy schemes at the continental and country level, Europe isn’t in very good shape on the tech and innovation front. The heavy-handed policies and volumes of regulations imposed by the European Union and its member states have played a role in that outcome. But these governments have simultaneously been pushing to promote innovation using a variety of technocratic policy levers and industrial policy schemes. Despite all those well-intentioned efforts, the EU has struggled to keep up with the US and China in most important modern tech sectors.

As Wennberg and Sandström note in their introductory chapter:

Grand schemes toward noble outcomes have a disappointing track record in human political and economic history. Conventional wisdom regarding authorities’ inability to selectively pinpoint certain technologies, sectors, or firms as winners, and the fact that large support structures for specific technologies are bound to distort incentives and result in opportunism, seem to have been forgotten.

In summarizing the chapters, they conclude that, “while the idea of aiming high and leveraging large portions of society’s resources to address some fundamental human challenges may sound appealing to many, such ideas have limited scientific credibility.”

Why do governments frequently fail in attempts to be entrepreneurial? Johan P. Larsson gets at the heart of the matter in his chapter when noting how, “[t]he state entrepreneur is not subject to real risk, often faces no market, and cannot be properly evaluated. It pays no price for being wrong and it struggles in assigning responsibility.” Which leads to two questions that are rarely asked, he notes: “[F]irst, how do we ensure that the state pays a price for being wrong? And second, when is that price high enough for us to know it is time to cut our losses?”

The authors of another chapter (Murtinu, Foss & Klein) concur and note how, “even well-intentioned and strongly motivated public actors lack the ability to manage the process of innovation.” “As stewards of resources owned by the public,” they note, “government bureaucrats do not exercise the ultimate responsibility that comes with ownership.” In other words, the state faces problems of misaligned incentives.

Several authors in the book highlight the various public choice problems often associated with large-scale industrial policy initiatives, including rent-seeking and capture. Wennberg and Sandström note how this results in less disruption as established players don’t seek to challenge existing market or technological status quos but instead simply seek to benefit from it. “[S]upport structures, platforms for private-public cooperation, and large volumes of technology-specific money usually end up in the hands of established interest groups,” they note. “Hence, they are not very likely to question these policies but will rather go along with the ride.”

John-Erik Bergkvist and Jerker Moodysson devote an entire chapter to this problem and offer a grim assessment of how past industrial policy schemes have exacerbated it:

Assuming that policies and programs are shaped by the interest groups that are affected by the policies, we highlight the risk that policymaking may end up as support for established interest groups rather than supporting the emergence of those who could act as institutional entrepreneurs or disruptors. Policies and programs may thus be captivated by dominant actors in the established regime, who have superior financial and relational resources. The result would then be that innovation policies sustain the established socio-technical structures of industries rather than contributing to the emergence of new structures.”

Other organizations are incentivized to support the status quo when big money is on the line. One of the most interesting chapters in the book was co-authored by Wennberg and Sandström along with Elias Collin. They examine the conflicts of interest inherent in many evaluations of industrial policy programs by various third parties, including academics and consultants who receive generous state contracts:

the overwhelming majority of evaluations are positive or neutral and that very few evaluations are negative. While this is the case across all categories of evaluators, we note that consulting firms stand out as particularly inclined to provide positive evaluations. The absence of negative or critical reports can be related to the fact that most of the studies do not rely upon methods that make it possible to discuss effects. This discrepancy between so many positive evaluations on the one hand and comparatively weak evaluation methods on the other hand leads us to suspect that evaluators are not sufficiently independent. Consultants and scholars that are funded by a government agency in order to evaluate the agency’s policies and programs are put in a position where it is difficult to maintain objectivity.

This is one reason why industrial policy continues to have such currency in European policy discussions despite a long track record of failure, as documented throughout this new book. The biggest problem for Europe lies in its layers of regulatory bureaucracy and heavy-handed treatment of entrepreneurs.

Later in the book, Zoltan J. Acs offers a grim account of just how bad things have been for Europe on the digital technology front in recent decades, despite the many state-led efforts to promote the sector. “The European Union protected traditional industries and hoped that existing firms would introduce new technologies. This was a policy designed to fail,” Acs argues. “What has been the outcome of E.U. policy in limiting entrepreneurial activity over recent decades?” he asks. Acs concludes that:

It is immediately clear… that the United States and China dominate the platform landscape. Based on the market value of top companies, the United States alone represents 66% of the world’s platform economy with 41 of the top 100 companies. European platform-based companies play a marginal role, with only 3% of market value.

He says that the United Kingdom’s “Brexit” from the European Union was a logical move, “because E.U. regulations were holding back the U.K.’s strong DPE (digital platform economy).” “If the United Kingdom was to realize its economic potential, it had to extricate itself from the European Union,” Acs says, due to the “dysfunctional E.U. bureaucracy.” No amount of industrial policy support is going to allow European firms to overcome those burdens. In fact, many of Europe’s industrial policy programs create the very disincentives that retard innovation and discourage entrepreneurialism in key sectors.

Several of the authors in the collection stress how the better role for the state is usually to set the table for innovation and growth without trying to determine everything that is served on the plate. As Wennberg and Sandström summarize:

the best policies to promote innovation are those that promote productive economic activity more generally: property rights protection, open and contestable markets, a stable monetary system, and legal rules that favor competition and entrepreneurship. Policy should promote an institutional environment in which innovation and entrepreneurship can flourish without trying to anticipate the specific outcomes of those processes—an impossible task in the face of uncertainty, technological change, and a dynamic, knowledge-based economy.

That’s good advice, as is everything found throughout the book. I encourage all those interested in these issues to take a hard look at it because it is particularly relevant even here in the Unites States, as Congress is currently considering a massive new 3,000-page, $350 billion industrial policy bill that I’ve labelled “The Most Corporatist & Wasteful Industrial Policy Ever.” There doesn’t seem to be anything stopping the momentum of this effort with both liberals and conservatives lining up to pass out the pork. I wish I could put a copy of Questioning the Entrepreneurial State in all their hands and ask them to read every word of it before they gamble hundreds of billions on such foolish efforts.

______________________

Additional Reading:

Adam Thierer, “Thoughts on the America COMPETES Act: The Most Corporatist & Wasteful Industrial Policy Ever,” January 26, 2022.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Does the US Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for AI & High-Tech?” Mercatus Center Research Paper, November 17, 2021.Adam Thierer, “The Coming Industrial Policy Hangover,” The Hill, February 16, 2022.Podcast: “What’s Wrong with Industrial Policy,” Hold These Truths with Rep. Dan Crenshw, February 16, 2022.Tad DeHaven and Adam Thierer, “The Military-Industrial Complex Offers a Cautionary Tale for Industrial Policy Planning,” Discourse, March 25, 2022.Adam Thierer, “Government Planning and Spending Won’t Replicate Silicon Valley,” Discourse, August 18, 2021.Adam Thierer, “To Promote Tech Hubs Across the Country, Governments Should Focus on Improving the General Business Environment,” Discourse, September 9, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy as ‘Casino Economics‘,” The Hill, July 12, 2021.Adam Thierer, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse,” Discourse, June 28, 2021.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.Matthew D. Mitchell and Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea,” Discourse, April 6, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy Advocates Should Learn from Don Lavoie,” Discourse, November 5, 2021.Adam Thierer, “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy,’” Technology Liberation Front, September 3, 2020.Adam Thierer, “Skeptical Takes on Expansive Industrial Policy Efforts,” Technology Liberation Front, March 15, 2021.April 18, 2022

Slide Presentation on “The Future of Innovation Policy”

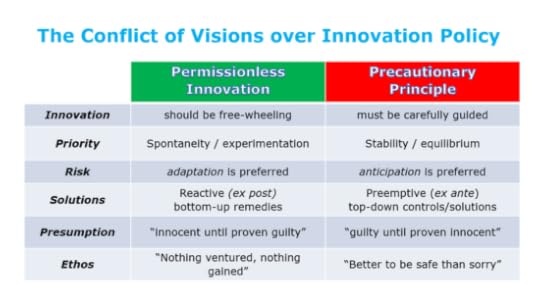

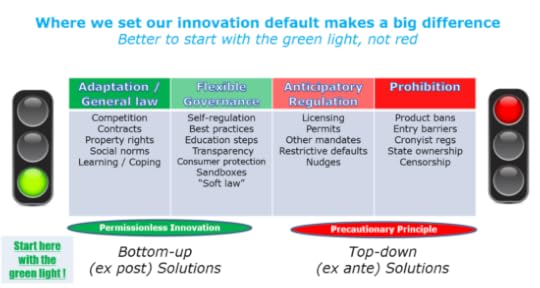

Here’s a slide presentation on “The Future of Innovation Policy” that I presented to some student groups recently. It builds on themes discussed in my recent books, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, and Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance: How Innovation Improves Economies and Governments. I specifically discuss the tension between permissionless innovation and the precautionary principle as competing policy defaults.

The Future of Innovation of Policy – Adam Thierer – Mercatus Center from Adam Thierer

Additional Reading:

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom , 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2016).“ How to Get the Future We Were Promised ,” Discourse, January 18, 2022.“ Defending Innovation Against Attacks from All Sides ,” Discourse, November 9, 2021. Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance: How Innovation Improves Economies and Governments (Washington, DC: Cato Institute, 2020).“ Converting Permissionless Innovation into Public Policy: 3 Reforms ,” Medium, November 29, 2017.“ Embracing a Culture of Permissionless Innovation,” Cato Online Forum, November 17, 2014.

Should All Kids Under 18 Be Banned from Social Media?

This weekend, The Wall Street Journal ran my short letter to the editor entitled, “We Can Protect Children and Keep the Internet Free.” My letter was a response to columnist Peggy Noonan’s April 9 oped, “Can Anyone Tame Big Tech?” in which she proposed banning everyone under 18 from all social-media sites. She specifically singled out TikTok, Youtube, and Instagram and argued “You’re not allowed to drink at 14 or drive at 12; you can’t vote at 15. Isn’t there a public interest here?”

I briefly explained why Noonan’s proposal is neither practical nor sensible, noting how it:

would turn every kid into an instant criminal for seeking access to information and culture on the dominant medium of their generation. I wonder how she would have felt about adults proposing to ban all kids from listening to TV or radio during her youth.

Let’s work to empower parents to help them guide their children’s digital experiences. Better online-safety and media-literacy efforts can prepare kids for a hyperconnected future. We can find workable solutions that wouldn’t usher in unprecedented government control of speech.

Let me elaborate just a bit because this was the focus of much of my writing a decade ago, including my book, Parental Controls & Online Child Protection: A Survey of Tools & Methods, which spanned several editions. Online child safety is a matter I take seriously and the concerns that Noonan raised in her oped have been heard repeatedly since the earliest days of the Internet. Regulatory efforts were immediately tried. They focused on restricting underage access to objectionable online content (as well as video games), but were immediately challenged and struck down as unconstitutionally overbroad restrictions on free speech and a violation of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

But practically speaking, most of these efforts were never going to work anyway. There was almost no way to bottle up all the content flowing in the modern information ecosystem without highly repressive regulation, and it was going to be nearly impossible to keep kids off the Internet altogether when it was the dominant communications and entertainment medium of their generation. The first instinct of every moral panic wave–from the waltz to comic books to rock or rap music to video games–has often been to take the easy way out by proposing sweeping bans on all access by kids to the content or platforms of their generation. It never works.

Nor should it. There is a huge amount of entirely beneficial speech, content, and communications that kids would be denied by such sweeping bans. That would make such ban highly counter-productive. But, again, usually such efforts just were not practically enforceable because kids are often better at the cat-and-mouse game than adults give them credit for. Moreover, imposing age limitations of speech or content are far more difficult than age-related bans on specific tangible products, like tobacco or other dangerous physical products.

Acknowledging these realities, most sensible people quickly move on from extreme proposals like flat bans of all kids using the popular media platforms and systems of the day. Over the past half century in the U.S., this has led to a flowering of more decentralized governance approach to kids and media that I have referred to as the “3E approach.” That stands for empowerment (of parents), education (of youth), and enforcement (of existing laws). The 3E approach includes a variety of mechanisms and approaches, including: self-regulatory codes, private content rating systems, a wide variety of different parental control technologies, and much more.

Over the past two decades, many multistakeholder initiatives and blue-ribbon commissions were created to address online safety issues in a holistic fashion. I summarized their conclusions in my 2009 report, “Five Online Safety Task Forces Agree: Education, Empowerment & Self-Regulation Are the Answer.” The crucial takeaway from all these task forces and commissions is that no silver-bullet solutions exist to hard problems. Child safety demands a vigilant but adaptive approach, rooted in a variety of best practices, educational approaches, and technological empowerment solutions to address various safety concerns. Digital literacy is particularly crucial to building wiser, more resilient kids and adults, who can work together to find constructive approaches to hard problems.

Importantly, our task here is never done. This is an ongoing and evolving process. Issues like underage access to pornography or violent content have been with us for a very long time and will never be completely “solved.” We must constantly work to improve existing online safety mechanisms while also devising new solutions for our rapidly evolving information ecosystem. Nothing should be off the table except the one solution that Noonan suggested in her essay. Just proposing outright bans on kids on social media or any other new media platform (VR will be next) is an unworkable and illogical response that we should dismiss fairly quickly. No matter how well-intentioned such proposals may be, moral panic-induced prohibitions on kids and media ultimately are not going to help them learn to live better, safer, and more enriching lives in the new media ecosystems of today or the future. We can do better.

February 18, 2022

Podcast: What’s Wrong with Industrial Policy?

I recently joined Rep. Dan Crenshaw on his Hold These Truths podcast to discuss, “What’s Wrong with Industrial Policy.” We chatted for 25 minutes about a wide range of issues related to the the growing push for grandiose industrial policy schemes in the US, including the massive new 3,000-page, $350 billion “COMPETES Act” legislation that recently passed in the House and which will soon be conferenced with a Senate bill that already passed.

On the same day this podcast was released this week, I also had a new op-ed appear in The Hill on “The Coming Industrial Policy Hangover.” In both that essay and the podcast with Rep. Crenshaw, I stress that, beyond all the other problems with these new industrial policy measures, no one is talking about the fiscal cost of it all. As I note:

In the rush to pass legislation, we’ve barely heard a peep about the $250-$350 billion price tag. This follows a massive splurge of recent government borrowing, which led to the U.S. national debt hitting another lamentable new record: $30 trillion. China already owns over $1 trillion of that debt, making one wonder if we’re really countering China by adopting a massive, new and unfunded industrial policy that they will end up financing indirectly.

Read my oped for more details and for a deeper dive of what’s wrong with the bills, see my earlier essay here on “Thoughts on the America COMPETES Act: The Most Corporatist & Wasteful Industrial Policy Ever.”

Additional Reading from Adam Thierer on Industrial Policy:

Adam Thierer, “Thoughts on the America COMPETES Act: The Most Corporatist & Wasteful Industrial Policy Ever,” January 26, 2022.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Does the US Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for AI & High-Tech?” Mercatus Center Research Paper, November 17, 2021.Adam Thierer, “The Coming Industrial Policy Hangover,” The Hill, February 16, 2022.Podcast: “What’s Wrong with Industrial Policy,” Hold These Truths with Rep. Dan Crenshw, February 16, 2022.Adam Thierer, “Government Planning and Spending Won’t Replicate Silicon Valley,” Discourse, August 18, 2021.Adam Thierer, “To Promote Tech Hubs Across the Country, Governments Should Focus on Improving the General Business Environment,” Discourse, September 9, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy as ‘Casino Economics‘,” The Hill, July 12, 2021.Adam Thierer, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse,” Discourse, June 28, 2021.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.Matthew D. Mitchell and Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea,” Discourse, April 6, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy Advocates Should Learn from Don Lavoie,” Discourse, November 5, 2021.Adam Thierer, “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy,’” Technology Liberation Front, September 3, 2020.Adam Thierer, “Skeptical Takes on Expansive Industrial Policy Efforts,” Technology Liberation Front, March 15, 2021.February 14, 2022

Opportunities for Students at the Mercatus Center

Are you a student or young scholar looking for opportunities to advance your studies and future career opportunities? The Mercatus Center at George Mason University can help. I’ve been with Mercatus for 12 years now and the most rewarding part of my job has always been the chance to interact with students and up-and-coming scholars who are hungry to learn more and make their mark on the world. Of course, learning and researching takes time and money. Mercatus works with students and scholars in many different fields to help them advance their careers by offering them some financial assistance to make their dreams easier to achieve.

Are you a student or young scholar looking for opportunities to advance your studies and future career opportunities? The Mercatus Center at George Mason University can help. I’ve been with Mercatus for 12 years now and the most rewarding part of my job has always been the chance to interact with students and up-and-coming scholars who are hungry to learn more and make their mark on the world. Of course, learning and researching takes time and money. Mercatus works with students and scholars in many different fields to help them advance their careers by offering them some financial assistance to make their dreams easier to achieve.

The Mercatus Center’s Academic & Student Programs team (ASP) are the ones that make all this happen. ASP is currently accepting applications for various fellowships running through the 2022-2023 academic year (for students) and 2023 calendar year (for our early-career scholars). ASP recruits, trains, and supports graduate students who have gone on to pursue careers in academia, government, and public policy. Additionally, ASP supports scholars pursuing research on the cutting edge of academia. Mercatus fellows have an opportunity to learn from and interact with an impressive collection of Mercatus faculty, affiliated scholars, and visitors.

ASP offers several different fellowship programs to suit every need. Our fellows explore and discuss the foundations of political economy and public policy and pursue research on pressing issues. For graduate students who follow this blog and are generally interested in the big questions surrounding innovation, we especially encourage you to consider the Frédéric Bastiat Fellowship which will be premiering its innovation study track for the 2022-2023 academic year. I usually am an instructor at the session on tech and innovation policy.

Here are more details on all the academic fellowships that Mercatus currently offers. Please pass along this information to any students or early-career scholars who might be interested.

For Students at Any University and in Any Discipline:

The Adam Smith Fellowship is a one-year, competitive fellowship program for graduate students enrolled in PhD programs at any university and in any discipline including, but not limited to, economics, philosophy, political science, and sociology. Adam Smith Fellows receive a stipend and attend colloquia on the Austrian, Virginia, and Bloomington schools of political economy. It is a total award of up to $10,000 for the year. The application deadline is March 15, 2022.

The Frédéric Bastiat Fellowship is a one-year, competitive fellowship program for graduate students who are enrolled in master’s, juris doctoral, and doctoral programs from any university and in any discipline including, but not limited to, economics, law, political science, and public policy. Frédéric Bastiat Fellows receive a stipend and attend colloquia on political economy and public policy. It is a total award of up to $5,000 for the year. The application deadline is March 15, 2022.

The Oskar Morgenstern Fellowship is a one-year, competitive fellowship program for students who are enrolled in PhD programs from any university and in any discipline with training in quantitative methods. Oskar Morgenstern Fellows receive a stipend and attend colloquia on utilizing quantitative and empirical techniques to explore key questions and themes advanced by the Austrian, Virginia, and Bloomington schools of political economy. It is a total award of up to $7,000 for the year. The application deadline is March 15, 2022.

For Those Considering or in the Early Stages of Graduate School:

The Don Lavoie Fellowship is a competitive, renewable, and online fellowship program for advanced undergraduates, recent graduates considering graduate school, and early-stage graduate students. Fellowships are open to students from any discipline who are interested in studying key ideas in political economy and learning how to utilize these ideas in academic and policy research. It is a total award of up to $1,250 for the semester. The deadline to apply for the Don Lavoie Fellowship for the Fall 2021 semester is April 15, 2022.

For Early Career Scholars:

The Mercatus Center’s James Buchanan Fellowship is awarded to scholars in any discipline who have recently graduated from their doctoral programs. The aim of this fellowship is to encourage early-career scholars to critically engage ideas in the political economy of Adam Smith and the Austrian, Virginia, and Bloomington schools of political economy. It is a total award of up to $15,000 for the year. The application deadline is April 15, 2022.

February 7, 2022

The Precautionary Principle: A Plea for Proportionality

Gabrielle Bauer, a Toronto-based medical writer, has just published one of the most concise explanations of what’s wrong with the precautionary principle that I have ever read. The precautionary principle, you will recall, generally refers to public policies that limit or even prohibit trial-and-error experimentation and risk-taking. Innovations are restricted until their creators can prove that they will not cause any harms or disruptions. In an essay for The New Atlantis entitled, “Danger: Caution Ahead,” Bauer uses the world’s recent experiences with COVID lockdowns as the backdrop for how society can sometimes take extreme caution too far, and create more serious dangers in the process. “The phrase ‘abundance of caution’ captures the precautionary principle in a more literary way,” Bauer notes. Indeed, another way to look at it is through the prism of the old saying, “better to be safe than sorry.” The problem, she correctly observes, is that, “extreme caution comes at a cost.” This is exactly right and it points to the profound trade-offs associated with precautionary principle thinking in practice.

In my own writing about the problems associated with the precautionary principle (see list of essays at bottom), I often like to paraphrase an ancient nugget of wisdom from St. Thomas Aquinas, who once noted in his Summa Theologica that, if the highest aim of a captain were merely to preserve their ship, then they would simply keep it in port forever. Of course, that is not the only goal of a captain has. The safety of the vessel and the crew is essential, of course, but captains brave the high seas because there are good reasons to take such risks. Most obviously, it might be how they make their living. But historically, captains have also taken to the seas as pioneering explorers, researchers, or even just thrill-seekers.

This was equally true when humans first decided to take to the air in balloons, blimps, airplanes, and rockets. A strict application of the precautionary principle would have instead told us we should keep our feet on the ground. Better to be safe than sorry! Thankfully, many brave souls ignored that advice and took the heavens in the spirit of exploration and adventure. As Wilbur Wright once famously said, “If you are looking for perfect safety, you would do well to sit on a fence and watch the birds.” Needless to say, humans would have never mastered the skies if the Wright brothers (and many others) had not gotten off the fence and taken the risks they did.

Opportunity Costs Matter

Here we get to the true danger of strict versions of the precautionary principle: It essentially becomes a crime to get off the fence and do anything risky at all. This sets up the potential for stasis and stagnation as societal learning is severely curtailed. Progress becomes harder because there can be no reward without some risk. — both individually or societally. “Caution makes sense except when it doesn’t,” Bauer notes. She continues on to note:

Used too liberally, the precautionary principle can keep us stuck in a state of extreme risk-aversion, leading to cumbersome policies that weigh down our lives. To get to the good parts of life, we need to accept some risk.

As I argued in a book on these issues, the root problem with precautionary principle thinking is that “living in constant fear of worst-case scenarios—and premising public policy on them—means that best-case scenarios will never come about.” If societal attitudes and public policy will not tolerate the idea of any error resulting from experimentation with new and better ways of doing things, then we will obviously not get many new and better things! Scientist Martin Rees refers to this truism about the precautionary principle as “the hidden cost of saying no.”

The opportunity cost of inaction or stasis can be hard to quantify but imagine if we organized our entire society around a rigid application of the precautionary principle. Bauer notes that this is basically what we did during COVID. And the results are in. “It’s far past time we ask ourselves when abundance really means excess, when our precautionary measures against Covid have gone too far, when we have ignored the costs and lost all sense of proportionality.” Unfortunately, the precautionary mindset–which is always rooted in fear of the unknown–took control. As Bauer notes:

It should have been socially acceptable to debate the merits of these tradeoffs, with nuance and without censure. But that is not what happened. Early in the pandemic, an unspoken rule — thou shalt not question the costs — sprang up and stifled discourse.

“And here’s the worst of it: the costs of excess caution can persist long after the initial danger has passed,” she notes. “It’s no different with Covid: our knee-jerk caution may have downstream effects that persist after the virus has ceased to be a threat.” She cites many compelling examples of the negative effects associated with extreme precautionary thinking during COVID, noting how, “[t]he impact of travel and trade restrictions on food security and childhood vaccination in developing countries will likely reverberate for decades.” Moreover:

The Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare the risks of extreme protection: lost businesses, lost livelihoods, lost graduations, lost loves, lost goodbyes; the loss of personal agency over life’s most intimate and meaningful moments; the loss, quite possibly, of our cherished principles of liberal democracy. A recent report by International IDEA, a democracy advocacy organization, concluded that many countries had become more authoritarian as they took steps to contain the pandemic.

This list of lockdown trade-offs goes on and the aggregate costs will be staggering once economists and others get around to better estimating them. As noted, gauging those costs will be challenging because of the many variables and values that come into play. But it remains vital that society takes risk analysis and trade-offs more seriously so that we don’t make these mistakes again and again.

Proportionality is the Key

Toward that end, Bauer makes “a plea for proportionality.” She wants society to strike a more reasonable balance when it comes to policy measures that might block actions and research that could help us better understand how to deal with risk uncertainties. Accordingly, “we must understand when to apply the precautionary principle and when to move on from it.”

“The precautionary principle doesn’t come with such checks and balances. On the contrary, it tends to perpetuate itself and acquire a life of its own,” she notes. In other words, once set in place initially for a given issue or sector, precautionary principle thinking tends to grow like bad weeds until it has taken over everything in sight. (To see the consequences of that in fields like aviation, space, nanotech, and others, please check out J. Storrs Hall’s amazing new book, Where Is My Flying Car?)

Of course, proportionality cuts both ways, and as I noted in my last two books, there are some instances in which at least a light version of the precautionary principle should be preemptively applied, but they are limited to scenarios where the threat in question is tangible, immediate, irreversible, and catastrophic in nature. In such cases, I argue, society might be better suited thinking about when an “anti-catastrophe principle” is needed, which narrows the scope of the precautionary principle and focuses it more appropriately on the most unambiguously worst-case scenarios that meet those criteria. Generally speaking, however, this test is not satisfied in the vast majority of cases. “Innovation Allowed” should be our default principle.

Conclusion

The single most important thing that we must always remember when debating precautionary principle-based policies is that, just because someone has good intentions and claims safety as their goal, that does not automatically make the world a safer place. To repeat: Excessive safety-related measure can result in less safety overall. Or again, as Bauer says, “extreme caution comes at a cost.”

No one ever summarized this truism more clearly than the great political scientist Aaron Wildavsky, who devoted much of his life’s work to proving how efforts to create a risk-free society would instead lead to an extremely unsafe society. In his 1988 book, Searching for Safety, Wildavsky warned of the dangers of “trial without error” reasoning, and contrasted it with the trial-and-error method of evaluating risk and seeking wise solutions to it. He argued that wisdom is born of experience and that we can learn how to be wealthier and healthier as individuals and a society only by first being willing to embrace uncertainty and even occasional failure. Here was the crucial takeaway:

The direct implication of trial without error is obvious: If you can do nothing without knowing first how it will turn out, you cannot do anything at all. An indirect implication of trial without error is that if trying new things is made more costly, there will be fewer departures from past practice; this very lack of change may itself be dangerous in forgoing chances to reduce existing hazards. . . . Existing hazards will continue to cause harm if we fail to reduce them by taking advantage of the opportunity to benefit from repeated trials.

Trial and error is the basis of all societal learning, and without it, humanity will be less safe and less prosperous over the long run. Gabrielle Bauer’s new essay captures that insight better than anything I’ve read since Wildavsky was writing about the dangers of the precautionary principle. I beg you to jump over to New Atlantis and read her entire article. It’s absolutely essential.

________________

Additional reading from Adam Thierer on the precautionary principle

Adam Thierer, “How Many Lives Are Lost Due to the Precautionary Principle?” The Bridge, October 31, 2019.Adam Thierer, “How to Get the Future We Were Promised,” Discourse, January 18, 2022.Adam Thierer, “Failing Better: What We Learn by Confronting Risk and Uncertainty,” in Sherzod Abdukadirov (ed.), Nudge Theory in Action: Behavioral Design in Policy and Markets (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016): 65-94.Adam Thierer, “Innovation and the Trouble with the Precautionary Principle,” AIER, April 20, 2020.Adam Thierer, “Are ‘Permissionless Innovation’ and ‘Responsible Innovation’ Compatible?” Technology Liberation Front, July 12, 2017.Adam Thierer, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2016).Adam Thierer, “Problems with Precautionary Principle-Minded Tech Regulation & a Federal Robotics Commission,” Medium, September 22, 2014.Adam Thierer, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle,” Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology 14, no. 1 (2013): 312–50.February 4, 2022

Podcast: An Update on Federal & State Driverless Cars Policy

This week, I hosted another installment of the “Tech Roundup,” for the Federalist Society’s Regulatory Transparency Project. This latest 30-minute episode was on, “Autonomous Vehicles: Where Are We Now?” I was joined by Marc Scribner, a transportation policy expert with the Reason Foundation. We provided an quick update of where federal and state policy for AVs stands as of early 2022 and offered some thoughts about what might happen next in the Biden Administration Department of Transportation (DOT). Some experts believe that the DOT could be ready to start aggressively regulating driverless car tech or AV companies, especially Elon Musk’s Tesla. Tune in to hear what Marc and I have to say about all that and more.

Related Reading:

Marc Scribner, “Congress’ failure to enact an automated vehicle regulatory framework is an opportunity for states“Marc Scribner, “Challenges and Opportunities for Federal Automated Vehicle Policy“Marc Scribner, “10 Best Practices For State Automated Vehicle Policy“Adam Thierer, “Elon Musk and the Coming Federal Showdown Over Driverless Vehicles“

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower