Adam Thierer's Blog, page 7

January 26, 2022

Thoughts on the America COMPETES Act: The Most Corporatist & Wasteful Industrial Policy Ever

On Tuesday, Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, posted the text of the “America Creating Opportunities for Manufacturing, Pre-Eminence in Technology and Economic Strength Act of 2022,” or “The America COMPETES Act.” As far as industrial policy measures go, the COMPETES Act is one of the most ambitious and expensive central planning efforts in American history. It represents the triumph of top-down, corporatist, techno-mercantilist thinking over a more sensible innovation policy rooted in bottom-up competition, entrepreneurialism, private investment, and free trade.

Unprecedented Planning & Spending

First, the ugly facts: The full text of the COMPETES Act weighs in at a staggering 2,912 pages. A section-by-section “summary” of the measure takes up 109 pages alone. Even the shorter “fact sheet” for the bill is 20 pages long. It is impossible to believe that anyone in Congress has read every provision of this bill. It will be another case of having “to pass the bill so you can find out what’s in it,” as Speaker Pelosi once famously said about another mega-measure.

Of course, a mega bill presents major opportunities for lawmakers to sneak in endless gobs of pork and unrelated policy measures they can’t find any other way to get through Congress. The Senate already passed a similar 2,600-page companion measure last summer, “The U.S. Innovation and Competition Act.” Lawmakers loaded up that measure with so much pork and favors for special interests that Sen. John N. Kennedy (R-La.) labelled the effort an “orgy of spending porn.” Like that effort, the new COMPETES Act includes $52 billion to boost domestic semiconductor production as well as $45 billion in grants and loans to address supply chain issues.

But there are billions allocated for other initiatives, as well as countless provisions addressing other technologies and sectors, including: 5G mobile networks, biometrics, quantum information science, “the development of safe and trustworthy artificial intelligence and data science,” cybersecurity literacy, drone security, microelectronics, electronic waste, genomics, isotope development, and the Large Hadron Collider and high intensity lasers, among many other things. The measure also proposes a broad array of Green New Deal-esque efforts focused on things like: biometrology, climate and Earth modeling, deforestation and overfishing matters, solar energy, bioenergy, the creation of a National Engineering Biology Research and Development Initiative and a Regional Clean Energy Innovation Program at the Department of Energy, clean water programs, a national clean energy incubator program, and helium conservation, again among many other things. There are even provisions addressing the trading of shark fins and coral reef conservation.

A Sweeping Macroeconomic Planning Exercise

There are more sweeping macroeconomic provisions and mandates in the bill. For example, the COMPETES Act would create a new “national supply chain database,” as well as a Supply Chain Resiliency and Crisis Response Office in the Department of Commerce, while also requiring the Director of White House Office of Science & Technology Policy to develop and submit to Congress a 4-year comprehensive national S&T strategy. The measure also includes trade adjustment assistance for workers, firms, and farmers and even provisions dealing with currency undervaluation. There are also many provisions addressing drug manufacturing and medical supply chain issues. There are even proposed expansions of federal antitrust power. (Apparently, once America’s grandiose industrial policies magically create global powerhouses in every sector, we’ll need expanding antitrust action to tear them all down and start all over again! Meanwhile, perhaps the greatest irony of the new industrial policy efforts is that, while lawmakers are falling all over themselves to shower corporate America with hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars, policymakers are simultaneously on a regulatory and antitrust jihad against many successful tech companies with bills that would break them up or destroy their business models.)

Finally, the COMPETES Act includes a huge assortment of national security and foreign policy-related provisions, most of which focus on countering China in some fashion. “There’s a lot of Cold War-style influence mongering happening here,” says Reason’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown, including programs that sound like they could have been concocted by the CIA, such as the bill’s “Countering China’s Educational and Cultural Diplomacy in Latin America” initiative. But there is also a lot of language here addressing other regions or countries, including: Oceania, Africa, the Arctic, the Middle East, Iran, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and others.

The relationship of most of these provisions to U.S. industrial competitiveness is tenuous to say the least. Nonetheless, those provisions take up a huge amount of space in this nearly 3,000-page industrial policy measure and may end up complicating its passage.

A Chicken in Every Pot

The inclusion of “Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs” in the bill deserves special attention. The Act proposes $7 billion over four years to fund 10 different innovation hubs and it includes many provisions about how and where money will be spent. It’s hard to see how spreading $7 billion across 10 hubs is actually going to result in much once every special interest gets their cut of the action, but proposals like these are all the rage these days. It’s the equivalent of policymakers promising a high-tech chicken in every pot, or a Silicon Valley in every state.

In a two-part series for Discourse, I documented the problems associated with the many previous government efforts to create innovation hubs, tech clusters, or science parks. The government’s track record in this regard is long and lamentable. Instead of following a time-tested approach getting the broad innovation policy environment right through a “generalized” approach to economic growth and development, most policymakers took unwise shortcuts and tried using “targeted” development schemes that were incredibly risky and ended up squandering a huge amount of taxpayer resources.

But all those failed past efforts probably won’t stop this high-tech pork barrel effort from rolling forward in some fashion. The proposed new regional hub effort comes on top of an announcement last July by the Commerce Department that the agency plans to allocate $1 billion in pandemic recovery funds to create or expand “regional industry clusters” as part of the administration’s new “Build Back Better Regional Challenge.” The agency’s list of possible winning funding ideas includes an “artificial intelligence corridor” and a “climate-friendly electric vehicle cluster.” And there are many other federal and state programs throwing money at the idea of hub or “cluster” formation, or even just highly cronyist efforts to attract a single big tech firm. (Anyone remember the Foxconn fiasco in Wisconsin?)

As Matt Mitchell and I have noted, this growing trend represents the collision of federal industrial policy and long-standing state-based economic development efforts. Regardless of how well-intentioned they may be, it is highly unlikely these new tech pork barrel efforts will produce better results than the long string of earlier federal and state failures.

Secondary Effects & Unforeseeable Costs

A bill this big presents many other big opportunities for corporations and other special interests. It’s no wonder that many of companies, trade associations, and other special interests are lining up to support this effort. In a recent study co-authored with Connor Haaland (“Does the US Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for AI & High-Tech”), we outlined “the way rent-seeking and cronyism often become chronic problems for highly targeted, big-budget industrial policy efforts.” Those problems will grow exponentially if the COMPETES Act passes. Everyone expects a cut of the action when Washington starts showering sectors with money.

But there’s a bigger problem associated with the everything-and-the-kitchen-sink approach to such a massive industrial policy bill. All the ambiguities associated with a monster measure like this means that agency bureaucrats will be left to fill in all the details for many years to come. It is folly of the highest order to believe that all these agencies will work together in a tightly coordinated and consistent way to advance industrial policy efforts or address “strategic objectives.” Anyone currently following the fight between the FAA and FCC over the rollout of 5G wireless networks will know what I am talking about. Moreover, delegating broad authority and big money to all these agencies just further reinforces the rent-seeking instincts of special interests, who will rush to their respective regulatory masters with hat in hand. The presents agencies with an added policy lever to blackmail companies into doing what they want without any new regulations even being issued.

And then there is the final consideration: where will all the money come from for this grand exercise in technocratic central planning? The Senate bill costs an estimated $250 billion. To be clear, that’s A QUARTER TRILLION DOLLARS. We’re talking big money, and chances are that the final price tag for the House’s COMPETES Act will be even higher. Does the money to fund all this profligate spending just fall like manna from industrial policy heaven? No, it will come out the pockets of the American taxpayer and American companies (who will just pass the bill along to consumers). This will have dynamic effects on growth and innovation that are almost never discussed in industrial policy debates. Here’s how Connor Haaland and I put it in our big study:

“First, a dollar spent pursuing one objective is a dollar that could have been invested differently, and potential better. Second, the very act of imposing taxes to cover these state gambits results in costs and distortions that must be accounted for. Some of these costs are deadweight losses associated with taxes and tax collection more generally. But this points to a third lesson: The true potential costs associated with industrial policy programs also need to account for the negative secondary effects of rent-seeking, bureaucracy, and the many other downsides of the political system, included cost overruns and corruption.”

As the old saying goes: There is no free lunch.

Conclusion: There Is a Better Way

Some advocates of the COMPETES Act label it a “competitiveness bill” or an “innovation initiative.” It takes a great deal of hubris to pretend that that the economy is just a giant machine to be manipulated and that policymakers can easily “dial in” the desired innovation results through massive bills and expanded bureaucracy.

Lawmakers and bureaucrats are not going to allocate capital more efficiently than private innovators and investors. Nor are they going to be able to “shore up supply chains” or create tech hubs in every city just by sprinkling a little magical industrial policy pixie dust thinly across the entire nation.

We should not try to compete with China by becoming China. Nor do we need to. Markets and supply chains recover from setbacks faster than governments can. This week, the White House reiterated its support for industrial policy efforts to strengthen supply chains and extend subsidies to the semiconductors industry. But, assuming the COMPETES Act passes, it’ll take years to get all the planning and spending going. When government spins those proverbial dials, it does so very slowly and extremely inefficiently. Meanwhile, the same day the White House was making these announcements, it was also touting that $80 billion in private investment has been announced by the US semiconductor industry recently. Just last week, Intel announced it plans to invest at least $20 billion in two new chip-making facilities in Ohio. Scott Lincicome and Ilana Blumsack have documented the many other private initiatives underway by the semiconductor industry to expand domestic manufacturing capacity, as well as efforts by foreign firms like Samsung to invest here to take advantage of our skilled workforce and vibrant capital market. This is all happening despite the fact that Congress is still debating an industrial policy measure that may end up being too bloated to even achieve successful passage this session.

Does government have any role to play? It certainly does. Most current industrial policy proposals fail to understand that the most important thing that policymakers can do is to clean up decades of earlier failed industrial policy efforts. Industrial policies in fields like energy, aviation, space, communications and other sectors skewed markets in unnatural and inefficient ways by favoring specific technologies and companies over others. This is because industrial policy all too often devolves into the business of picking winners and losers. This is not always done in a formal way or even with clear intent. Rather, when government is throwing around billions and engaging in casino economics by placing big bets, a lucky few will win at the expense of others.

Of course, not all government support is as wasteful or corporatist in character. “Basic” R&D efforts are certainly more defensible than most “applied” or “targeted” efforts. “When government is supporting basic R&D,” Connor Haaland and I have noted, “the chances of wasting scarce resources on risky investments can be minimized to some degree, at least as compared with highly targeted applied R&D investments in unproven technologies and firms.”

And then there are all of the education and training efforts governments can undertake. If lawmakers were smart, they would have just limited their efforts to the sort of things found in Titles III, V, and VI of the COMPETES Act, which relates to boosting STEM education, high-tech workforce training, improving National Science Foundation research efforts, and funding various other federal science agencies and labs, that conduct more basic research.

Meanwhile, government defense spending isn’t going to dry up anytime soon and it continues to represent an indirect form of industrial policy given the trillions of dollars that are spread around through the so-called “military-industrial complex.” That certainly doesn’t mean America should be greatly expanding its already bloated defense budgets in the name of expanding industrial policy. Yet, for better or worse, government is always going to be spending a lot of money on defense priorities and it gives it a chance to address whatever “strategic” needs it has.

But the current industrial policy behemoth advancing in Congress represents a misguided effort at domestic retrenchment and a collapse into a lamentable sort of techno-mercantilism thinking that happens every quarter century or so. In my paper with Haaland as well as a separate essay, I have documented just how misguided the “Japan panic” of the 1980s and 90s was. One policymaker and pundit after another lined up to breathlessly proclaim the end of America if we failed to adopt a grandiose industrial policy to counter Japan. Of course, that industrial policy approach ended up being such a disaster that even the Japanese government itself declared in a 2000 report that “the Japanese model was not the source of Japanese competitiveness but the cause of our failure.”

Moreover, it is worth noting what happened with the Internet and digital technology in the U.S. versus the rest of the world in the 1990s and beyond. America essentially put a policy firewall between the emerging digital technology sector and the old industrial policy regime we had for analog sectors and technologies, like broadcasting and wireline telephony. And thank God we did! America’s digital technology sector thrived, and U.S.-headquartered tech companies became household names across the globe. Meanwhile, the Europeans have spent 20 years crafting one misguided industrial policy scheme after another to equal America’s accomplishments. Despite highly targeted and expensive efforts to foster a domestic digital tech base, the EU has instead generated a string of industrial policy failures that Haaland and I documented in detail here.

Corporatism, cronyism, and profligate pork-barrel spending were not the sources of America’s competitive advantage in digital technology, and top-down planning did not make our digital technology companies global powerhouses. Instead, we got our innovation culture right for digital technology. First and foremost, our the default regulatory policy for the digital economy was permissionless innovation. No one had to ask anyone for the right to develop all those new digital technologies and online platforms. The Clinton Administration’s 1997 “Framework for Global Electronic Commerce” announced that “governments should encourage industry self-regulation and private sector leadership where possible” and “avoid undue restrictions on electronic commerce.” Second, investors saw that positive policy ecosystem developing and moved quickly to shower entrepreneurs in this sector with unprecedented private venture capital investment. Third, education and career opportunities in these sectors expanded accordingly. Real-time “learning by doing” took place as millions of people learned new digital skillsets on the fly. Kids learned how to code before anyone could even teach them how to type. Most importantly, talented immigrants and foreign investors then came here to take advantage of all this, allowing America to steal away the best and brightest from the rest of the world.

This constitutes one of the greatest capitalist success stories in human history, and it all happened without targeted, technocratic, top-down industrial policy planning. This is the more principled and less costly vision for innovation policy America needs today to counter China and the rest of the world. There is absolutely no reason that we can’t apply this same vision to aviation, space, semiconductors, energy, nanotech, AI, and many other sectors of importance.

_______________________________________

Additional Reading from Adam Thierer on Industrial Policy:

Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Does the US Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for AI & High-Tech?” Mercatus Center Research Paper, November 17, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Government Planning and Spending Won’t Replicate Silicon Valley,” Discourse, August 18, 2021.Adam Thierer, “To Promote Tech Hubs Across the Country, Governments Should Focus on Improving the General Business Environment,” Discourse, September 9, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy as ‘Casino Economics‘,” The Hill, July 12, 2021.Adam Thierer, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse,” Discourse, June 28, 2021.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.Matthew D. Mitchell and Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea,” Discourse, April 6, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy Advocates Should Learn from Don Lavoie,” Discourse, November 5, 2021.Adam Thierer, “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy,'” Technology Liberation Front, September 3, 2020.Adam Thierer, “Skeptical Takes on Expansive Industrial Policy Efforts,” Technology Liberation Front, March 15, 2021.Other critical essays on industrial policy:

Mike Watson, “Industrial Policy in the Real World,” National Affairs, Summer 2021.Scott Lincicome and Huan Zhu, “Questioning Industrial Policy: Why Government Manufacturing Plans Are Ineffective and Unnecessary,” Cato Institute Working Paper, June 16, 2021.Samuel Gregg, “Industrial Policy Mythology Confronts Economic Reality,” Law & Liberty, September 3, 2021.Chang-Tai Hsieh, “Countering Chinese Industrial Policy Is Counterproductive,” Project Syndicate, September 15, 2021.Anne O. Krueger, “America’s Muddled Industrial Policy,” CGTN, June 25, 2021.Tracy C. Miller, “The Case for Limiting Government Semiconductor Subsidies,” The Hill, June 26, 2021.Scott Lincicome, “The ‘Endless Frontier’ and American Industrial Policy,” Cato Institute Blog, May 26, 2021.Daniel W. Drezner, “Is the United States capable of industrial policy in 2021?” Washington Post, June 14, 2021.Douglas Holtz-Eakin, “The Nicest Thing I Can Write About Supply Chain Policy,” The Daily Dish, June 10, 2021.Lipton Matthews, “Industrial Policy—a.k.a. Central Planning—Won’t Make America Great,” Mises Wire, November 5, 2021.Richard Beason, “Japanese Industrial Policy: An Economic Assessment,” National Foundation for American Policy, November 2021.Douglas Irwin, “Memo to the Biden administration on how to rethink industrial policy,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, October 2020.Jim Pethokoukis, “Will Biden’s embrace of industrial policy pay off?” AEI Blog, January 15, 2021.Phil Levy & Christine McDaniel, “Does the U.S. Need a Vigorous Industrial Policy?” Discourse, February 16, 2021.Veronique de Rugy, “Support for Industrial Policy is Growing,” AIER, January 18, 2020.Ben Reinhardt on concerns about The Endless Frontier ActRyan Bourne, “Do Oren Cass’s Justifications for Industrial Policy Stack Up?” Cato Commentary, August 15, 2019.Scott Lincicome, “Manufactured Crisis: ‘Deindustrialization, Free Markets, and National Security,” Cato Policy Analysis No. 907, January 27, 2021.Judge Glock, “Semiconductors Don’t Need Subsidies,” City Journal, April 20, 2021.Judge Glock, “Industrial Policy Hurts Industry,” Washington Examiner, April 20, 2021.January 25, 2022

The Case for Innovation, Progress & Abundance: Some Readings

This is a compendium of readings on “progress studies,” or essays and books which generally make the case for technological innovation, dynamism, economic growth, and abundance. I will update this list as additional material of relevance is brought to my attention.

Recent Essays

Alec Stapp & Caleb Watney, “Progress is a Policy Choice,” Institute for Progress, January 20, 2022.Adam Thierer, “How to Get the Future We Were Promised,” Discourse, January 18, 2022.Katherine Boyle, “Building American Dynamism,” Future, January 14, 2022. Derek Thompson, “A Simple Plan to Solve All of America’s Problems,” The Atlantic, January 12, 2022.Matthew Yglesias, “The Case for More Energy,” October 7, 2021.Ezra Klein, “The Economic Mistake the Left Is Finally Confronting,” The New York Times, September 19, 2021.Jason Crawford, “We need a new philosophy of progress,” The Roots of Progress, August 23, 2021.Noah Smith, “Techno-optimism for the 2020s,” December 3, 2020. Ezra Klein, “Why We Can’t Build,” Vox, April 22, 2020.Marc Andreesen, “It’s Time to Build,” Future, April 18, 2020.Eli Dourado, “How do we move the needle on progress?” September 26, 2019.José Luis Ricón, “About the ‘Progress’ in Progress Studies” September 6, 2019.Will Rinehart, “Progress Studies: Some Initial Thoughts,” August 30, 2019.Adam Thierer, “Is There a Science of Progress?” AIER, August 8, 2019.Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen, “We Need a New Science of Progress,” The Atlantic, July 30, 2019.Tyler Cowen, “The Case for the Longer Term,” Cato Unbound, January 9, 2019.Vinod Khosla, “We Need Large Innovations,” Medium, January 1, 2018.Adam Thierer, “How Technology Expands the Horizons of Our Humanity,” Medium, November 19, 2018. Eli Dourado, “How Technological Innovation Can Massively Reduce the Cost of Living,” PlainText, January 29, 2016.

Books

January 20, 2022

The Most Important Technology Policy Book of the Past Quarter Century

Discourse magazine has just published my review of Where Is My Flying Car?, by J. Storrs Hall, which I argue is the most important book on technology policy written in the past quarter century. Hall perfectly defines what is at stake if we fail to embrace a pro-progress policy vision going forward. Hall documents how a “Jetsons” future was within our grasp, but it was stolen away from us. What held back progress in key sectors like transportation, nanotech & energy was anti-technological thinking and the overregulation that accompanies it. “[T]he Great Stagnation was really the Great Strangulation,” he argues. The culprits: negative cultural attitudes toward innovation, incumbent companies or academics looking to protect their turf, litigation-happy trial lawyers, and a raft of risk-averse laws and regulations.

Discourse magazine has just published my review of Where Is My Flying Car?, by J. Storrs Hall, which I argue is the most important book on technology policy written in the past quarter century. Hall perfectly defines what is at stake if we fail to embrace a pro-progress policy vision going forward. Hall documents how a “Jetsons” future was within our grasp, but it was stolen away from us. What held back progress in key sectors like transportation, nanotech & energy was anti-technological thinking and the overregulation that accompanies it. “[T]he Great Stagnation was really the Great Strangulation,” he argues. The culprits: negative cultural attitudes toward innovation, incumbent companies or academics looking to protect their turf, litigation-happy trial lawyers, and a raft of risk-averse laws and regulations.

Hall coins the term “the Machiavelli Effect” to identify why many people simultaneously fear the new and different, and they also want to protect whatever status quo they benefit from (or at least feel comfortable with). He builds on this passage from Niccolò Machiavelli’s classic 1532 study of political power, “The Prince”:

[I]t ought to be remembered that there is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, then to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things. Because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new. This coolness arises partly from fear of the opponents, who have the laws on their side, and partly from the incredulity of men, who do not readily believe in new things until they have had a long experience of them. Thus it happens that whenever those who are hostile have the opportunity to attack they do it like partisans, whilst the others defend lukewarmly, in such wise that the prince is endangered along with them.

Hall notes that the Machiavelli Effect “has nothing to do with any conspiracy.” Rather, it comes down to human nature: Many people simultaneously fear the new and different, and they also want to protect whatever status quo they benefit from (or at least feel comfortable with). Isaac Asimov identified the same problem in a 1974 lecture when he noted how there had been “bitter, exaggerated, last-stitch resistance . . . to every significant technological change that had taken place on earth.” [On this same point, also see Innovation and Its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technologies, by Calestous Juma. It’s the best history on the topic.]

Hall identifies how the Machiavelli Effect held back nuclear, nanotech, and aviation technologies. “Over the long run, unchecked regulation destroys the learning curve, prevents innovation, protects and preserves inefficiency, and makes progress run backward.” The problem is the Precautionary Principle, which undermines the learning curve is by setting policy defaults to no trial and error as opposed to free to experiment. There can be no reward without some risk! Hall quotes Wilbur Wright on this, who once noted that, “If you are looking for perfect safety, you would do well to sit on a fence and watch the birds.”

Over-regulation of those sectors also resulted in massive misallocation of talent, “taking more than a million of the country’s most talented and motivated people and putting them to work making arguments and filing briefs instead of inventing, developing, and manufacturing.” Hall is equally critical of government R&D efforts. “One of the great tragedies of the latter 20th century, and clearly one of the causes of the Great Stagnation,” he argues, “was the increasing centralization and bureaucratization of science and research funding.”

Hall’s book builds on Jason Crawford’s insight that, “We need a new philosophy of progress,” that is rooted in optimism about the future and support for a culture of trial-and-error experimentation. Hall’s book is a major contribution to that effort. Hall makes a profoundly moral case for innovation. “The zero-sum society is a recipe for evil,” because it leaves us with a “static level of existence” that denies us the ability to improve the human condition. Indeed, Hall’s book is the most full-throated defense of innovation by a trained scientist or engineer since Samuel Florman’s 1976 “Existential Pleasures of Engineering.” Both are celebrations of the potential for humanity to build more and better tools to improve the world.

Hall’s book should also be read alongside books from Virginia Postrel (“The Future and Its Enemies”), Steven Pinker (“Enlightenment Now”), Matt Ridley (“How Innovation Works”) and Deirdre McCloskey’s three-volume trilogy about the history of modern economic growth. These scholars argue that there is a symbiotic relationship between innovation, economic growth, pluralism and human betterment, and that to deny people the ability to improve their lot in life is fundamentally anti-human.

I just cannot recommend Hall’s Where Is My Flying Car? highly enough. It’s a masterpiece. And bravo to Stripe Press for publishing a beautiful hardbound edition. It is a stunning book both to behold and read. Order it now, and jump over to Discourse to read my entire review of it.

December 8, 2021

The Classical Liberal Approach to Digital Media Free Speech Issues

On December 13th, I will be participating in an Atlas Network panel on, “Big Tech, Free Speech, and Censorship: The Classical Liberal Approach.” In anticipation of that event, I have also just published a new op-ed for The Hill entitled, “Left and right take aim at Big Tech — and the First Amendment.” In this essay, I discuss the growing calls from both the Left and the Right for a variety of new content regulations. I then outline the classical liberal approach to concerns about free speech platforms more generally, which ultimately comes down to the proposition that innovation and competition are always superior to government regulation when it comes to content policy.

In the current debates, I am particularly concerned with calls by many conservatives for more comprehensive governmental controls on speech policies of private platforms, so I will zero in on those efforts in this essay. First, here’s what both the Left and the Right share in common in these debates: Many on both sides of the aisle desire more government control over the editorial decisions made by private platforms. They both advocate more political meddling with the way private firms make decisions about what types of content and communications are allowed on their platforms. In today’s hyper-partisan world,” I argue in my Hill column, “tech platforms have become just another plaything to be dominated by politics and regulation. When the ends justify the means, principles that transcend the battles of the day — like property rights, free speech and editorial independence — become disposable. These are things we take for granted until they’ve been chipped away at and lost.”

Despite a shared objective for greater politicization of media markets, the Left and the Right part ways quickly when it comes to the underlying objectives of expanded government control. As I noted in my Hill op-ed:

there is considerable confusion in the complaints both parties make about “Big Tech.” Democrats want tech companies doing more to limit content they claim is hate speech, misinformation, or that incites violence. Republicans want online operators to do less, because many conservatives believe tech platforms already take down too much of their content.

This makes life very lonely for free speech defenders and classical liberals. Usually in the past, we could count on the Left to be with us in some free speech battles (such as putting an end to the endless wars over “indecency” regulations for broadcast radio and television), while the Right would be with us on others (such as opposition to the “Fairness Doctrine” or similar mandates). Today, however, it is more common for classical liberals to be fighting with both sides about free speech issues.

My focus is primarily on the Right because, with the rise of Donald Trump and “national conservatism,” there seems to be a lot of soul-searching going on among conservatives about their stance toward private media platforms, and the editorial rights of digital platforms in particular.

In my new Hill essay and others articles (all of which are listed down below), I argue there is a principled classical liberal approach to these issues that was nicely outlined by President Ronald Reagan in his 1987 veto of Fairness Doctrine legislation, when he said:

History has shown that the dangers of an overly timid or biased press cannot be averted through bureaucratic regulation, but only through the freedom and competition that the First Amendment sought to guarantee.

Let’s break that line down. Reagan admits that media bias can be a real thing. Of course it is! Journalists, editors, and even the companies they work for all have specific views. They all favor or disfavor certain types of content. But, at least in the United States, the editorial decisions made by these private actors are protected by the First Amendment. Section 230 is really quite secondary to this debate, even though some Trumpian conservatives wrongly suggest that it’s what they want changed. In reality, national conservatives would need to find a way to work around well-established First Amendment protections if they wanted to impose new restrictions on the editorial rights of private parties.

But why would they want to do that? Returning to the Reagan veto statement, we should remember how Reagan noted that, even if the First Amendment did not protect the editorial discretion of private media platforms, bureaucratic regulation was not the right answer to the problem of “bias.” Competition and choice were the superior answer. This is the heart and soul of the classical liberal perspective: more innovation is always superior to more regulation.

For the past 30 years, conservatives and classical liberals were generally aligned on that point. But the ascendancy of Donald Trump created a rift in that alliance that now threatens to grow into a chasm as more and more Right-of-center people begin advocating for comprehensive control of media platforms.

The problems with that are numerous beginning with the fact that none of the old rationales for media controls work (and most of them never did). Consider the old arguments justifying widespread regulation of private media:

“Scarcity” was the old primary justification for media regulation, but we live in the exact opposite world today, in which the most common complaint about media is the abundance of it!Conversely, the supposed “pervasiveness” of some media (namely broadcasting) was used as a rationale for government censorship in the past. But that, too, no longer works because in today’s crowded media marketplace and Internet-enabled world, all forms of communications and entertainment are equally pervasive to some extent.State ownership and licensing of spectrum was another rationale for control that no longer works. No digital media platforms need federal licenses to operate today. So, that hook is also gone. Moreover, the answer to the problem of government ownership of media is to stop letting the government own and control media assets, including spectrum.“Fairness” is another old excuse for control, with some regulatory advocates suggesting that five unelected bureaucrats at the Federal Communications Commission (or some other agency) are well-suited to “balance” the airing of viewpoints on media platforms. Of course, America’s disastrous experience with the Fairness Doctrine proved just how wrong that thinking was. [I summarize all the evidence proving that here.]That leaves a final, more amorphous rationale for media control: “gatekeeper” concerns and assertions that private media platforms can essentially become “state actors.” In the wake of Donald Trump’s “de-platorming” from Facebook and Twitter, many of his supporters began adopting this language in defense of more aggressive government control of private media platforms, including the possibility of declaring those platforms common carriers. But as Berin Szóka and Corbin Barthold of Tech Freedom note:

Where courts have upheld imposing common carriage burdens on communications networks under the First Amendment, it has been because consumers reasonably expected them to operate conduits. Not so for social media platforms. [. . . ] When it comes to the regulation of speech on social media, however, the presumption of content neutrality does not apply. Conservatives present their criticism of content moderation as a desire for “neutrality,” but forcing platforms to carry certain content and viewpoints that they would prefer not to carry constitutes a “content preference” that would trigger strict scrutiny. Under strict scrutiny, any “gatekeeper” power exercised by social media would be just as irrelevant as the monopoly power of local newspapers was in [previous Supreme Court holdings].

Put simply, efforts to stretch extremely narrow and limited common carriage precedents to fit social media just don’t work. We’ve already seen lower courts admit as much when blocking the enforcement of conservative-led efforts in Florida and Texas to limit the editorial discretion of private social media platforms. What would be needed would be a more far-reaching strike at the First Amendment itself, which would entail a jurisprudential revolution at the Supreme Court — reversing about a century of free speech precedents — or an almost unthinkable effort to amend the First Amendment itself. These things are almost certainly not going to occur.

But this hasn’t stopped some conservatives from pitching extreme solutions in their efforts to regulate digital media at both the state and federal level. I discuss these efforts in previous essays on, “How Conservatives Came to Favor the Fairness Doctrine & Net Neutrality,“ “Sen. Hawley’s Radical, Paternalistic Plan to Remake the Internet,“ and “The White House Social Media Summit and the Return of ‘Regulation by Raised Eyebrow’.“ Perhaps some Trump-aligned conservatives understand that these legislative efforts are unlikely to stick, but they continue to push them in an attempt to make life hell for tech platforms, or perhaps just to troll the Left and “own the Libs.”

But some conservatives seem to really believe in some of the extreme ideas they are tossing around. What is particular troubling about these efforts is the way — following Trump’s lead — some conservatives, including even more mainstream conservative groups like the Heritage Foundation, are increasingly referring to private media platforms as “the enemy of the people.” That’s the kind of extremist language typically used by totalitarian thugs and Marxist lunatics who so hate private enterprise and freedom of speech that they are willing to adopt a sort of burn-the-village-to-save-it rhetorical approach to media policy.

And speaking of Marxists, here’s what is even more astonishing about these efforts by some conservatives to use such rationales in support of comprehensive media regulation: It is all based on the “media access” playbook concocted by radical Leftist scholars a generation ago. As I summarized in my essay on, “The Surprising Ideological Origins of Trump’s Communications Collectivism“:

Media access advocates look to transform the First Amendment into a tool for social change to advance specific political ends or ideological objectives. Media access theory dispenses with both the editorial discretion rights and private property rights of private speech platforms. Private platforms become subject to the political whims of policymakers who dictate “fair” terms of access. We can think of this as communications collectivism.

Media access doctrine is rooted in an arrogant, elitist, anti-property, anti-freedom ethic that suggest the State is a better position to dictate what can and cannot be said on private speech platforms. “It’s astonishing, yet nonetheless true,” I continued on in that essay, “that the ideological roots of Trump’s anti-social media campaign lie in the works of those extreme Leftists and even media Marxists. He has just given media access theory his own unique nationalistic spin and sold this snake oil to conservatives.” Yet, Trump and other national conservatives are embracing this contemptible doctrine because now more than ever the ends apparently justify the means in American politics. Nevermind that all this could come back to haunt them when the Left somehow leverages this regulatory apparatus to control Fox News or other sites and content that conservatives favor! Once media platforms are viewed as just another thing to be controlled by politics, the only question is which politics and how are those politics enforced? Certainly both the Left and the Right cannot both have their way given all that current divides them.

What is utterly perplexing about all this is how much thanks national conservatives really owe to the major digital platforms they now seek to destroy. As I noted in my new Hill op-ed:

There has never been more opportunity for conservative viewpoints than right now. Each day on Facebook, the top-10 most shared links are dominated by pundits such as Ben Shapiro, Dan Bongino, Dinesh D’Souza and Sean Hannity. Right-leaning content is shared widely on Twitter each day. Websites like Dailywire.com and Foxnews.com get far more traffic than the New York Times or CNN.

Thus, conservatives might be shooting themselves in the foot if they were able to convince more legislatures to adopt the media access regulatory playbook because it could have profound unintended consequences once the Left uses those tools to somehow restrict access to “hate speech” or “misinformation” — and then define it so broadly so as to include much of the top material posted by conservatives on Facebook and Twitter ever day.

Not all conservatives have drank the media access kool-aid. In the wake of Trump’s deplatforming from a few major sites, a wave of new Right-leaning digital services are being planned or have already launched. (Axios and Forbes recently summarized some of these efforts.) I don’t know which will of these efforts will succeed, but more competition and platform-building are certainly superior to current calls by some Trump supporters for government regulation of mainstream social media services. Again, this is the old Reagan vision at its finest! We can achieve a better media landscape, “only through the freedom and competition that the First Amendment sought to guarantee,” not through bureaucratic regulation. It remains the principled path forward.

________________________________________

Additional Reading :

“Left and right take aim at Big Tech — and the First Amendment““When It Comes to Fighting Social Media Bias, More Regulation Is Not the Answer““FCC’s O’Rielly on First Amendment & Fairness Doctrine Dangers““Conservatives & Common Carriage: Contradictions & Challenges““The Great Deplatforming of 2021““A Good Time to Re-Read Reagan’s Fairness Doctrine Veto““Sen. Hawley’s Radical, Paternalistic Plan to Remake the Internet““How Conservatives Came to Favor the Fairness Doctrine & Net Neutrality““Sen. Hawley’s Moral Panic Over Social Media““The White House Social Media Summit and the Return of ‘Regulation by Raised Eyebrow’““The Not-So-SMART Act““The Surprising Ideological Origins of Trump’s Communications Collectivism“Older essays & testimony :

Adam Thierer, “Why Regulate Broadcasting: Toward a Consistent First Amendment Standard for the Information Age,” Catholic University Law School, 15 CommLaw Conspectus (Summer 2007): 431-482.Adam Thierer, Testimony at FCC’s Hearing on “Serving the Public Interest in the Digital Era”, March 3, 2010.Adam Thierer, “FCC v. Fox and the Future of the First Amendment in the Information Age,” Federalist Society, Engage (Feb. 2009).November 17, 2021

New Mercatus Center Report on Industrial Policy

The Mercatus Center has just released a new special study that I co-authored with Connor Haaland entitled, “Does the United States Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for High Tech?” With industrial policy reemerging as a major issue — and with Congress still debating a $250 billion, 2,400-page industrial policy bill — our report does a deep dive into the history various industrial policy efforts both here and abroad over the past half century. Our 64-page survey of the historical record leads us to conclude that, “targeted industrial policy programs cannot magically bring about innovation or economic growth, and government efforts to plan economies from the top down have never had an encouraging track record.”

The Mercatus Center has just released a new special study that I co-authored with Connor Haaland entitled, “Does the United States Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for High Tech?” With industrial policy reemerging as a major issue — and with Congress still debating a $250 billion, 2,400-page industrial policy bill — our report does a deep dive into the history various industrial policy efforts both here and abroad over the past half century. Our 64-page survey of the historical record leads us to conclude that, “targeted industrial policy programs cannot magically bring about innovation or economic growth, and government efforts to plan economies from the top down have never had an encouraging track record.”

We zero in on the distinction between general versus targeted economic development efforts and argue that:

whether we are referring to federal, state, or local planning efforts—the more highly targeted development efforts typically involve many tradeoffs that are often not taken into consideration by industrial policy advocates. Downsides include government steering of public resources into unproductive endeavors, as well as more serious problems, such as cronyism and even corruption.

We also stress the need to more tightly define the term “industrial policy” to ensure rational evaluation is even possible. We argue that, “industrial policy has intentionality and directionality, which distinguishes it from science policy, innovation policy, and economic policy more generally.” We like the focus definition used by economist Nathaniel Lane, who defines industrial policy as “intentional political action meant to shift the industrial structure of an economy.”

Our report examines the so-called “Japan model” of industrial policy that was all the rage in intellectual circles a generation ago and then compares it to the Chinese and European industrial policy efforts of today, which many pundits claim that the US needs to mimic. We find problems with those models and argue that:

America’s goal should not be to “imitate China” or “copy its playbook” when it comes to targeted industrial policy and technological governance of AI and other high-tech sectors. Europe’s approach, although not as heavy-handed, is also not a good model. Not only would the Chinese and European approaches potentially undermine the permissionless innovation ethos that made America’s tech companies become global powerhouses, but expanded industrial policy efforts would entail massive state bets on risky ventures using taxpayer resources.

We discuss the public choice dynamics surrounding many industrial development efforts and note that, “what is often described as “industrial policy” is in reality nothing more than industrial politics.” We highlight how many of the largest industrial policy programs have been prone to highly inefficient contracting procedures and massive cost overruns. Sometimes outright corruption even becomes a problem with some of the largest programs. But that’s not the only cost. Sometimes, in their effort to promote specific industrial outputs or outcomes, government undermines the very innovation they hope to spur.

When governments repress the entrepreneurial spirit of their most innovative creators and companies, this is bound to have negative ramifications for long-term competitiveness and economic growth. Heavy-handed industrial policy schemes can contribute to this sort of repression as the state gains more levers of control over private companies.

We note how that has certainly been the case in the European Union, where “countries have adopted a highly precautionary regulatory model for new digital sectors that shuns risk-taking and focuses on maximizing other values at the expense of disruptive change. This approach has resulted in fewer national champions, and it has cost Europe in terms of global competitive advantage,” we note. We also highlight the long string of failed European industrial policy programs.

Ours is not a doctrinaire analysis; we take a pragmatic approach to the evaluation of industrial policy programs and proposals. Some of them may succeed based simply on the reality that “if government officials roll the proverbial industrial policy dice enough times, some bets are bound to pay off, at least indirectly.” But any serious analysis of these efforts, we argue, must fully weigh the trade-offs associated with the potential tax and compliance burdens associated with funding them to begin with.

But we admit that, “industrial policy will always be with us to some extent, given the sheer size of government and the many existing programs already devoted to economic development or high-tech initiatives.” Toward that end, we wrap up the paper with a variety of high-level recommendations about industrial policy. We highlight how:

The priority should be generalized economic development over targeted development efforts. The most important thing that policymakers can do to boost economic opportunities is to create a legal and regulatory environment that is conducive to entrepreneurship, investment, innovation, and free trade. [. . . ] government should focus on setting the table for entrepreneurial activity instead of trying to determine everything on the plate. To put this differently, policymakers need to avoid the “fun stuff” and focus on “boring” issues that often get neglected.

We apply these insights to the ongoing debate over regional economic development and the specific effort currently underway at the federal level to encourage “regional innovation hubs,” as federal and state lawmakers look to create “the next Silicon Valley” elsewhere.

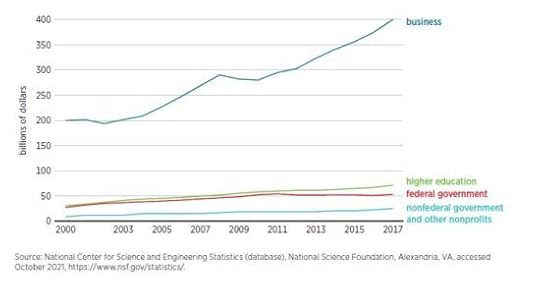

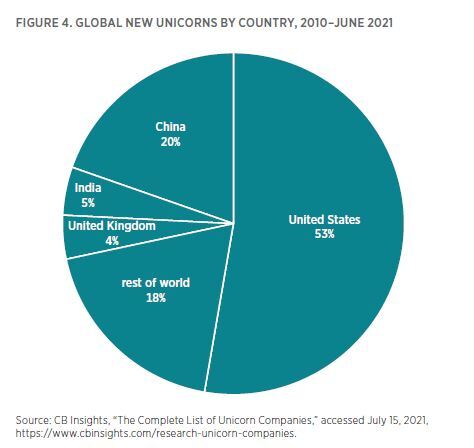

In terms of our nation’s overall investment in R&D, we note that “[t]he United States has the most vibrant venture capital (VC) market in the world, and this market helps support risky ventures without gambling with taxpayer dollars.” While some bemoan the fact that private enterprise provides the bulk of R&D expenditures in the US – and that amount is increasing relative to governmental sources – this is actually something that should be celebrated. The strength of private-funded R&D helps set the US apart and make investment markets nimbler and more responsive to real-world needs. Moreover, global unicorn growth in the US continues at a healthy clip. From 2010 to mid-2021, the US created 53 percent of global unicorns, compared with 20 percent for China. These facts are often overlook in industrial policy debates.

While our paper is comprehensive, admittedly, there are some things we leave out of the analysis or do not spend as much time discussing. For example, there is a never-ending debate about the relationship between national security and industrial policy that raises many hard questions. A nation needs military hardware to defend itself, and almost every program to provide weapons and military equipment in the US involve private contracting to get them. These are the biggest industrial policy programs at all, but we don’t spend a lot of time focus on them in our paper because that would have taken us far afield.

We have a short section on these issues that notes how “defense-related programs have also been prone to highly inefficient contracting procedures and massive cost overruns.” Many of these programs remain vital, however, and must find a way to make them more efficient and cost-effective. But there are still other issues related to national security and industrial policy that raise hard questions, including: export or import controls, trade restrictions, and more. These continue to be challenging issues and I personally hope to revisit some of them in upcoming essays.

With Congress still trying to finalize its mega industrial policy bill, our paper is relevant to the short-term debate over these issues. But our hope is that this paper offers a big-picture, long-term framework for thinking through the challenges associated with industrial policy issues both here and abroad.

Here is the outline of the paper and, again, you can find it at this link. (The report can also be found on SSRN & Research Gate).

Introduction: Definitional Challenges 5Calls for Expanding Industrial Policy to Boost High-Tech Innovation 8Some (Quickly Forgotten) Recent History 11The Romantic View of Industrial Policy vs. Reality 15The Challenge of Creating “National Champions”: Europe’s Failures 20Adverse Effects of State-Led Promotion: The China Model Examined 23Where Does Real Competitive Advantage Come From? 27Industrial Policy Did Not Give Us the Internet and the iPhone 33Evaluating Other Industrial Policy Efforts 39Using Competitions and Prizes to Encourage Innovation More Efficiently 46Conclusion: Generality Is Better Than Targeting________________________________

Additional Reading:

Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy Advocates Should Learn from Don Lavoie,” Discourse, November 5, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Government Planning and Spending Won’t Replicate Silicon Valley,” Discourse, August 18, 2021.Adam Thierer, “To Promote Tech Hubs Across the Country, Governments Should Focus on Improving the General Business Environment,” Discourse, September 9, 2021.Adam Thierer, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse,” Discourse, June 28, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy as ‘Casino Economics‘,” The Hill, July 12, 2021.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.Matthew D. Mitchell and Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea,” Discourse, April 6, 2021.Adam Thierer, “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy,’” Technology Liberation Front, September 3, 2020.Adam Thierer, “Skeptical Takes on Expansive Industrial Policy Efforts,” Technology Liberation Front, ongoing series.November 9, 2021

Lavoie’s Lessons for Industrial Policy Planners

Discourse magazine recently published my essay on what “Industrial Policy Advocates Should Learn from Don Lavoie.” With industrial policy enjoying a major revival in the the U.S. — with several major federal proposals are pending or already set to go into effect — I argue that Lavoie’s work is worth revisiting, especially as this weekend was the 20th anniversary of his untimely passing. Jump over to Discourse to read the entire thing.

But one thing I wanted to just briefly highlight here is the useful tool Lavoie created that helped us think about the “planning spectrum,” or the range of different industrial policy planning motivations and proposals. On one axis, he plotted “futurist” versus “preservationist” advocates and proposals, with the futurists wanting to invest in new skills and technologies, while the preservationists seek to prop up existing sectors. On the other axis, he contrasted “left-wing or pro-labor” and “right-wing or pro-business” advocates and proposals.

Lavoie used this tool to help highlight the remarkable intellectual schizophrenia among industrial policy planners, who all claimed to have the One Big Plan to save the economy. The problem was, Lavoie noted, all their plans differed greatly. For example, he did a deep dive into the work of Robert Reich and Felix Rohatyn, who were both outspoken industrial policy advocates during the 80s. Reich as affiliated with the Harvard School of Government at that time, and Rohatyn was a well-known Wall Street financier. The industrial policy proposals set forth by Reich and Rohatyn received enormous media and academic attention at the time, yet no one except Lavoie seriously explored the many ways in which their proposals differed so fundamentally. Rohatyn was slotted on the lower right quadrant because of his desire to prop up old sectors and ensure the health of various private businesses. Reich fell into the upper quadrant of being more of futurist in his desire to have the government promote newer skills, sectors, and technologies.

After identifying the many inconsistencies among these planners and their proposed schemes, Lavoie pointed out that these differences raised some obvious questions: Whose plan are we supposed to follow when proposed plans conflict? And how much stock should we place in the wisdom of industrial policy when the leading advocates cannot even agree on what sectors and technologies are worth preserving or promoting? It was a simply but powerful insight that should led us to calling into question anyone who tries to pretend that they have all the answers when it comes to industrial policy planning. And, as I argue in my new essay, this insight helps us identify the continuing intellectual schizophrenia among industrial policy planners and schemes today. If you jump over to my longer piece, you’ll see my breakdown of all this, but it’s plotted here:

In the end, I conclude that:

The limitations of industrial policy exist regardless of the policymaker’s intentions. There are no “good guys” versus “bad guys” when it comes to industrial policy efforts; there are just many people with many different technocratic plans, all of which are constrained by limited knowledge and resources.

Moreover, Lavoie most important piece of relevant advice is the simple adage that, if you find yourself in a hole, it is wise to stop digging. Constantly doubling down on planning efforts is not going to help governments escape the problems created by their earlier interventions. Unfortunately, this is exactly what many industrial policy advocates do: They insist that America already has an industrial policy, but that it lacks the sort of conscious design or coherent form or direction they desire. But that is the typical sort of hubris and folly we’ve always heard from planners. They always think there’s a proverbial “better path” out there and want us to imagine that they can lead us down it with wiser planning that avoids all the problems of all those past failed planning efforts.

As Lavoie taught us long ago, we’d be wise to reject their various schemes and recommendations. “In light of the inherent deficiencies of central planning, it might be argued that the U.S. should instead try to reduce current government interference with the competitive process to the absolute minimum consistent with other political goals,” he concluded. It remains wise advice for today’s policymakers.

________________________________________

Additional Reading:

Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Does the US Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for AI & High-Tech?” Presentation for IHS Papers Workshop: Does America Need a New Industrial Policy?, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Government Planning and Spending Won’t Replicate Silicon Valley,” Discourse, August 18, 2021.Adam Thierer, “To Promote Tech Hubs Across the Country, Governments Should Focus on Improving the General Business Environment,” Discourse, September 9, 2021.Adam Thierer, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse,” Discourse, June 28, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy as ‘Casino Economics‘,” The Hill, July 12, 2021.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.Matthew D. Mitchell and Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea,” Discourse, April 6, 2021.Adam Thierer, “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy,’” Technology Liberation Front, September 3, 2020.Adam Thierer, “Skeptical Takes on Expansive Industrial Policy Efforts,” Technology Liberation Front, ongoing series.October 27, 2021

Tips & Best Practices for Aspiring Policy Scholars

A short presentation I do for Mercatus Center graduate students every couple of years offering advice to aspiring policy scholars looking to develop their personal brand & be more effective public policy analysts.

Tips & Best Practices for Aspiring Policy Scholars from Adam Thierer

October 1, 2021

What Explains the Rebirth of Analog Era Media?

What explains the rebirth of analog era media? Many people (including me!) predicted that vinyl records, turntables, broadcast TV antennas and even printed books seemed destined for the dustbin of technological history. We were so wrong, as I note in this new oped that has gone out through the Tribune Wire Service.

“Many of us threw away our record collections and antennas and began migrating from physical books to digital ones,” I note. “Now, these older technologies are enjoying a revival. What explains their resurgence, and what’s the lesson?”

I offer some data about the rebirth of analog era media as well as some possible explanations for their resurgence. “With vinyl records and printed books, people enjoy making a physical connection with the art they love. They want to hold it in their hands, display it on their wall and show it off to their friends. Digital music or books don’t satisfy that desire, no matter how much more convenient and affordable they might be. The mediums still matter.”

Read more here. Meanwhile, my own personal vinyl collection continues to grow without constraint! …

September 12, 2021

Can Government Reproduce Silicon Valley Everywhere?

Wishful thinking is a dangerous drug. Some pundits and policymakers believe that, if your intentions are pure and you have the “right” people in power, all government needs to do is sprinkle a little pixie dust (in the form of billions of taxpayer dollars) and magical things will happen.

Of course, reality has a funny way of throwing a wrench into the best-laid plans. Which brings me to the question I raise in a new 2-part series for Discourse magazine: Can governments replicate Silicon Valley everywhere?

In the first installment, I explore the track record of federal and state attempts to build tech clusters, science parks & “regional innovation hubs” using state subsidies and industrial policy. This is highly relevant today because of the huge new industrial policy push at the federal level is building on top of growing state and local efforts to create tech hubs, science parks, or various other types of industrial “clusters.

At the federal level, this summer, the Senate passed a 2,300-page industrial policy bill, the “United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021,” that included almost $10 billion over four years for a Department of Commerce-led effort to fund 20 new regional technology hubs, “in a manner that ensures geographic diversity and representation from communities of differing populations.” A similar proposal that is moving in the House, the “Regional Innovation Act of 2021,” proposes almost $7 billion over five years for 10 regional tech hubs. Meanwhile, the Biden administration also is pitching ideas for new high-tech hubs. In late July, the Commerce Department’s Economic Development Administration announced plans to allocate $1 billion in pandemic recovery funds to create or expand “regional industry clusters” as part of the administration’s new Build Back Better Regional Challenge. Among the possible ideas the agency said might win funding are an “artificial intelligence corridor,” an “agriculture-technology cluster” in rural coal counties, a “blue economy cluster” in coastal regions, and a “climate-friendly electric vehicle cluster.”

In my essay, I note that the economic literature on these efforts has been fairly negative, to put it mildly. There is no precise recipe for growing tech clusters, as most economists and business analysts note.

“Despite several attempts, Silicon Valley has not been successfully copied elsewhere,” notes Mark Zachary Taylor, author of “The Politics of Innovation: Why Some Countries Are Better Than Others at Science and Technology.” Judge Glock, a senior policy adviser with the Cicero Institute, offers a more blistering assessment of such efforts: “Almost every American state has tried to fund the creation of biotech clusters, projects that almost inevitably end with weeds growing through the parking-lot pavement and a trail of corrupt bargains.”

I then highlight the key findings from several major studies of these efforts, all of which make it clear that, as cluster scholars by Aaron Chatterji, Edward Glaeser and William Kerr noted in 2014 after gathering all the research conducted on the topic: existing evidence “suggests that the regional foundation for growth-enabling innovation is complex and that we should be cautious of single policy solutions that claim to fit all needs.” Furthermore, “even if clusters of entrepreneurship are good for local growth, it is less clear that cities or states have the ability to generate those clusters.”

I also highlight research from my Mercatus Center colleagues on “The Economics of a Targeted Economic Development Subsidy” documenting costs of state-level planning & case study of Foxconn fiasco. They summarize the fairly miserable track record of state and local mini-industrial policy efforts. As they note, the extensive economic literature on this matter finds that “the net effect of targeted economic development subsidies is likely to be negative” because “the taxes funding the subsidies will discourage more economic activity than will be encouraged by the subsidies themselves.” Similarly, Harvard Business School economist Josh Lerner evaluated dozens of similar targeted development efforts from around the globe in his 2009 book Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed—and What to Do About It. He concluded that “for each effective government intervention, there have been dozens, even hundreds, of failures, where substantial public expenditures bore no fruit.”

In my essay, I also discuss the astonishing array of federal efforts to promote the geographic spread of high-tech sectors and jobs since 2000. Throughout Bush, Obama, Trump & Biden admins, there’s been a lot of spending, but not a lot of success. Just lots of new laws and bureaucracies:

In 2012, the Obama administration launched the multiagency Rural Jobs and Innovation Accelerator Challenge and Advanced Manufacturing Jobs and Innovation Accelerator Challenge. This occurred at roughly the same time President Obama was launching his Startup America initiative. He also signed the JOBS Act (Jump-start Our Business Startups) in 2012. All these efforts included various measures to support the spread of advanced manufacturing and high-tech startups across the U.S. But none of these efforts have borne much fruit so far.

In the second installment of this series, I explore better ways to encourage regional tech innovation and economic development without doubling down on failed programs of the past. Specifically, I explain why, when it comes to economic development efforts, policymakers would be wise to avoid the costly, ineffective “fun stuff” and refocus on time-tested “boring” strategies:

The boring approach to economic development seeks to promote an open innovation culture that is conducive to risk-taking, investment and growth without the need to extend targeted privileges to particular firms or industries. Such a culture comes down to a classic mix of simplified and equally applied taxes, streamlined permitting processes and sensible regulations, limits on frivolous lawsuits, and clear protection of contracts and property rights.

As Matt Mitchell and I argued previously, policymakers need to resist the urge to go for broke with splashy policies and programs. They need to appreciate the benefits of generalized economic development policy (a.k.a. the boring approach) as opposed to far riskier targeted development efforts.

I also highlight recent research explaining how perhaps the simplest way to strengthen existing clusters, or give rise to new ones, is to make sure America’s immigration policies are hospitable to the best and brightest minds from across the globe.

And I note how, due to the problems associated with many other forms of government-sponsored R&D assistance, many scholars and policymakers are increasingly turning to the idea of government-sponsored competitions and prizes as a superior way to distribute R&D assistance.

With competitions, governments can set broad goals to help facilitate the search for important societal needs. The prizes then create a powerful incentive for innovators to pursue those goals, not only to win money, but also to gain recognition from peers and the public. Another alternative is just using lotteries to distribute R&D money instead of having agencies target grants. That at least avoids political shenanigans and paperwork delays, although it may not be a particularly effective approach.

There is also some good news is overlooked in today’s rush to make big industrial policy gambles: Venture capitalists and new startups are already spreading out naturally.

A 2021 study on “The State of the Startup Ecosystem” by Engine, a research and advocacy organization supporting startups, revealed that “as Series A funding grew over the last fifteen years, more of that growth has started to shift to areas located outside of the largest ecosystems.” Series A funding refers to the initial round of outside venture capitalist investment in startups. The report looked at Series A deals from 2003 to 2018 and found that “Series A rounds outside of the top five ecosystems grew nearly 900 percent, while the number of rounds outside of the top nine grew nearly tenfold.” Whereas Series A fundings outside of the top five ecosystems stood at 38% in 2003, they had jumped up to 43% in 2018. “The increase in deal location diversity over this period reflects an increasing spread in venture capital investment across the country and less centralization of investment in areas like Silicon Valley,” the report concluded.

Meanwhile, tech innovators and investors are increasingly engaging in innovation arbitrage as they move to cities and states across the nation that are more hospitable to entrepreneurial activities. Firms and investors are voting with their feet (and dollars) by flocking to areas where tech clusters can more naturally sprout because the general policy environment is sound.

But government efforts to artificially try to create regional innovation hubs in a top-down, technocratic fashion will almost certainly persist. As they do, some will argue that this time will be different! Perhaps, but it is more likely that the past is prologue; these new hubs will likely cause federal politicians to jockey for position to have their regions named one of the winners and get a big cut of all the new high-tech pork being served up by Washington. We can do better.

Jump over to Discourse to read both installments here and here.

Also, down below I list several other things I have written recently on industrial policy efforts more generally.

Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Does the US Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for AI & High-Tech?” Presentation for IHS Papers Workshop: Does America Need a New Industrial Policy?, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Government Planning and Spending Won’t Replicate Silicon Valley,” Discourse, August 18, 2021.Adam Thierer, “To Promote Tech Hubs Across the Country, Governments Should Focus on Improving the General Business Environment,” Discourse, September 9, 2021.Adam Thierer, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse,” Discourse, June 28, 2021.Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy as ‘Casino Economics‘,” The Hill, July 12, 2021.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.Matthew D. Mitchell and Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea,” Discourse, April 6, 2021.Adam Thierer, “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy,’” Technology Liberation Front, September 3, 2020.Adam Thierer, “Skeptical Takes on Expansive Industrial Policy Efforts,” Technology Liberation Front, ongoing series.July 16, 2021

Keeping Uncle Sam out of the Industrial Policy Casino

In my latest column for The Hill, I consider that dangers of government gambling our tax dollars on risky industrial policy programs. I begin by noting:

In my latest column for The Hill, I consider that dangers of government gambling our tax dollars on risky industrial policy programs. I begin by noting:

Roll the dice at a casino enough times, and you are bound to win a few games. But knowing the odds are not in your favor, how much are you willing to risk losing by continuing to gamble?

This is the same issue governments confront when they gamble taxpayer dollars on industrial policy efforts, which can best be described as targeted and directed efforts to plan for specific future industrial outputs and outcomes. Throwing enough money at risky ventures might net a few wins, but at what cost? Could those resources have been better spent? And do bureaucrats really make better bets than private investors?

I continue on to note that, while the US is embarking on a major new industrial policy push, history does not provide us with a lot of hope regarding Uncle Sam’s betting record when he starts rolling those industrial policy dice. “How much tolerance should the public have for government industrial policy gambling?” I ask. I continue on:

Generally speaking, “basic” support (broad-based funding for universities and research labs) is wiser than “applied” (targeted subsidies for specific firms or sectors). With basic R&D funding, the chances of wasting resources on risky investments can be contained, at least as compared to highly targeted investments in unproven technologies and firms.

I also argue that “The riskiest bets on new technologies and sectors are better left to private investors,” and note how, “America’s venture capital industry remains the envy of the world because it continues to power world-beating advanced technology.” Accordingly, I conclude:

While some government investments will always be necessary, policymakers engaging in casino economics means bad industrial policy bets and taxpayer money squandered on risky ventures best made by private actors. We need to keep Uncle Sam’s gambling habits in check.

Read the whole thing here. And here’s a list of more of my recent writing on industrial policy:

Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Does the US Need a More Targeted Industrial Policy for AI & High-Tech?” Presentation for IHS Papers Workshop: Does America Need a New Industrial Policy?, forthcoming, July 23, 2021.Adam Thierer, “‘Japan Inc.’ and Other Tales of Industrial Policy Apocalypse,” Discourse, June 28, 2021.Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.Matthew D. Mitchell and Adam Thierer, “Industrial Policy is a Very Old, New Idea,” Discourse, April 6, 2021.Adam Thierer, “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy,’” Technology Liberation Front, September 3, 2020.“Skeptical Takes on Expansive Industrial Policy Efforts,” Technology Liberation Front, ongoing series.Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower