Kelsey Timmerman's Blog, page 16

December 3, 2015

Suffering in the shame of silence after another mass shooting

Another mass shooting and I’m left feeling the same–ashamed.

As I wrote about the Syrian refugee crisis, empathy should be our default setting, and it’s where my heart and mind go every time I hear news like that of the mass shooting in San Bernadino or [insert the most recent mass shooting].

What if that were my son, daughter, wife, brother, sister, mom, or dad gunned down simply for showing up to work or to school or to church that day?

My daughter is in first grade and several times a year the school has active shooter drills. They don’t call them that. She just knows to hide in the corner or in the bathroom and be really quiet.

What if that weren’t a drill? What if a real-life shooter held a gun to her head and pulled the trigger blowing away the dreams of her becoming a cowgirl/writer, our plans of going to Harry Potter world in February? Her laugh, her joy, her hugs, her, all gone.

I can barely write this. Or imagine it.

If that happened to her or someone close to me, I would stand, I would speak out. Ending gun violence would become the cause of my life. But it hasn’t happened to her or anyone close to me. So I hear the same arguments from the talking heads, and I do nothing and I suffer in silence from the shame of my silence.

Writer Colum McCann’s writing space is littered with notes from himself and from others. One of them reads:

“What is the source of our first suffering? It lies in the fact that we hesitated to speak. It was born in the moment when we accumulated silent things within us.”

The NY Times’ piece that profiles McCann follows him to Newtown Connecticut, where 20 children and 6 adults were shot and killed at Sandy Hook Elementary. The students were reading his book Let the Great World Spin and discussing how to move forward after tragedy. Here’s what he told the students:

“I’m not interested in blind optimism, but I’m very interested in optimism that is hard-won, that takes on darkness and then says, ‘This is not enough.’ But it takes time, more time than we can sometimes imagine, to get there. And sometimes we don’t.”

Being ashamed and having empathy is not enough without action.

The reality is that since I haven’t experienced the tragedy of this type of violence, I’m not going to make this the cause of my life, but I can support those parents, brothers, sisters, and spouses of those who are.

Here’s how I’m planning on acting: This morning I made a donation to Americans for Responsible Solutions, founded by former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords and her husband Mark. I also signed the group’s petition to congress.

It’s a small something to do, but it’s not silence. It’s not nothing. It’s not recycling political talking points and arguments. It’s supporting those who are acting.

Empathy without action is numbing. As a nation, we must continue to feel these tragedies and continue to act.

December 2, 2015

Beanie-to-briefs in ethical brands for less than a pair of boots

(Rocking my Krochet Kids beanie)

Most folks think shopping for clothing with your ethics is a privilege that few can afford. I’ve been writing about being an ethical and engaged consumer since I traveled around the world to meet the people who made my clothes.

Since writing Where Am I Wearing? I encouraged folks to wear one thing a day they knew was produced in a way that treated people and planet fairly. I reach a lot of college students and thought that a whole outfit in such clothes would be unaffordable.

That’s what I thought . . . until today.

Today, I decided to do a little online shopping experiment: I put together a whole outfit consisting of underwear, shirt, shoes, pants, socks, and a beanie by visiting the online stores of companies that I know are making responsible decisions about people and planet. And then I compared them to products you would normally find at the mall.

It turns out the ethical outfit I put together only cost $153, which was actually $8 cheaper than the normal outfit.

Don’t believe me? Check out the results and I’ll introduce you to some of my favorite ethical brands.

Underwear

It’s almost embarrassing to admit that I’m wearing Fair Trade underwear as I type this. A few years ago, Fair Trade underwear would’ve looked like something your grandma crocheted.They would be ethical but itchy. And when it comes to underwear I’d rather have them non-itchy than produced in a way that I was assured was ethical.

Pact Apparel underwear: They are the first company I know of to offer Fair Trade Certified Underwear (listed in the Fair Trade Shopping Guide). I love their marketing: “Change starts with your underwear!” I own several pairs of their boxer briefs. Great for the gym or for standing in front of a thousand college students talking about being an ethical consumer. Cost: $10 – $12.50 / pair

Compare to 5-pack of Hanes – $4 per pair

Shirt

Organic Cotton t-shirt produced by TS Designs in North Carolina: I Love TS Designs. I’ve gotten to know their owner, Eric Henry, over the years and visited their factory this fall. Eric and TS Designs are the real deal, driven by the greater good. Cost: $22 / shirt.

SustainU: Made in USA of recycled cotton. I spoke on a panel alongside the company’s founder Chris Yurba, a former Notre Dame fullback, and a pretty awesome dude. Cost: $15 (on sale)

prAna: Was one of the first brands to really get behind Fair Trade apparel. They’ve got some cool designs. I wear these as my fancy T-shirts–or business casual for normal folks. Cost: $35

Compare to Nike cotton shirt – $18.99

Shoes

Oliberté: The first shoe to be certified by Fair Trade USA. I’m one of their ambassadors, which means they sent me a free pair of shoes and I posed for some pics wearing them. Since that first pair, I bought another pair. They are really high quality and stand up against any leather shoe I’ve ever owned. Cost: $50 (usually more in the $125+ range but I found a pair on sale)

SoleRebels: Ethiopian-owned and -operated, I had a chance to visit this factory to see the amazing things they are accomplishing by paying workers a living wage. The shoes themselves are really comfortable–love the feel of the inner tube tire on the soul–but can look a little homemade. Cost: $85

Compare to Clark’s leather boot – $75

Pants

Patagonia: A company that is definitely a leader on all things responsible consumption and an early adopter of acknowledging where their products are made. I worked at a store that sold Patagonia and I’ve never seen a company stand behind their products like Patagonia. Customers would bring in a jacket with a hole and Patagonia would fix it or send them a new jacket for free. Cost of Fair Trade, organic cotton pants – $99

Raleigh Denim – I own one pair. Let’s just say when I bought them the credit card company called my wife. They are by far the best, most comfortable jeans, and by far the most expensive jeans I’ve ever owned. Cost: Let’s just say, it’s more than this entire outfit I’m putting together.

Levi’s – GoodGuide (a resources every ethical shopper should have on his or her phone) actually ranks Levi’s 2nd to Patagonia in their list of jean brands. Cost: $50

Compare to Old Navy – $40

Socks

Mitscoots: Made in Austin, Texas, by individuals transitioning out of homelessness. For every pair you buy Mitscoots gives a pair to someone living on the streets. Cost: $14 / pair

Pact Apparel also sells Fair Trade Certified socks: $8 / pair

Compare to Dockers dress socks – $3 / pair

Beanie

Krochet Kids: A few snowboarding high schooler from Spokane started to crochet beanies and sell them to friends. One of the snowboarders traveled to Uganda and saw people could use a good opportunity. The friends were all like, “We’re snowboarding dudes from Spokane and we learned to crochet. So could these Ugandan women.” The friends taught the women, and now you can buy the beanies, each hand signed by the woman who made them. Cost: $20

Compare to Under Armour beanie – $20

Be more than just a consumer. Be a producer.

Now for a larger point: We aren’t just going to shop our way to a better world. Each purchasing decision we make is a decision about people and planet, and, made collectively, they can make a difference. But we need to be more than consumers. We need to be producers.

Once you are dressed in all this ethical apparel, what are you going to produce? What are you going to produce with your passions, curiosities, life experiences, and skills? Are you and your snowboarding buddies going to start crocheting? Are you going to start an apparel business in North Carolina when 97% of such businesses have gone overseas?

Don’t just wear these items of clothing, be inspired by them.

–

This post was written (with the help of Oreo Kitty) while wearing a TS Designs T-shirt, SustainU hoodie, and Pact Apparel underwear.

November 25, 2015

Join my #BlackFridayFast

For the past few years, I’ve fasted on Black Friday. I don’t consume anything–no shopping and no eating for at least 16 hours.

If you’d like to join me, I’ll be doing it again this year from 12AM – 6 PM on Black Friday. You can follow and/or suffer along with me using the hashtag #BlackFridayFast.

Sixteen hours really isn’t that long. I once did it for 30 hours, and while it sucked, it wasn’t that bad. I wrote about the experience at the end of WHERE AM I EATING? (you can read the excerpt at the end of this post). Sixteen hours is plenty of time to accomplish what I want to accomplish through the fast.

How to get your hangry on

If you are pregnant, a hobbit, or suffer from chronic, apocalyptic-levels of hangriness, you may not want to give this a go. If you do participate, you’ll want to decrease your activity a bit (a great excuse to nap all day), drink a lot of water or juice (avoiding acidic juices), and break your fast with something nice on your belly. I usually break it with Thanksgiving leftovers or obscene amounts of Pizza King pizza, ignoring that last bit of advice altogether. Also at 11:59PM on Thanksgiving Day one minute before beginning the fast, you’ll find me somewhere near the fridge with a full mouth and belly.

Why I’m doing the #BlackFridayFast

I’m a contrarian

How’s that for honesty? I didn’t want a varsity letterman’s jacket in high school. That bad that you like now? I don’t like them now and have moved onto some other cooler band you’ve never heard of. (I’m actually not quite that bad, but I’m definitely somewhat of a contrarian.)

I’ve got nothing against those who shop on Black Friday. I’m not better than you. You probably love shopping much more than me. All that money you are saving on those deals…I would pay that much not to be in a crowded store at 3AM so tired I wanted to puke.

So there’s that. But there’s also the fact that I’m a bit of a contrarian. In fact, this rebelling against Black Friday thing is starting to catch on so much maybe I should think about going shopping.

REI will be closed on Black Friday, encouraging their patrons to play outside while documenting their experiences with the hashtag #OptOutside.

The group “Our Walmart” made up of 100 WalMart employees and 900 others has been fasting outside Walmarts for 15 days as they ask for a $15 minimum wage.

Clothing company Everlane will give all of its Black Friday profits to the sewers in its LA factory.

To know hunger the slightest bit

I fast to remember just how important food is by experiencing a bit of hunger. There are a billion undernourished humans on the planet and a billion overnourished. Like most of you reading this, I’m part of the last group. As I write in EATING:

“Love isn’t possible without food. Nothing is.”

Not eating reminds me of the necessity of food and our biological tie to plants and animals.

(I go in much more detail on how I think and feel about this in the excerpt)

Man belongs to the world

We need to be more than consumers–takers. We need to be producers and leavers as well.

A quote to ponder from Ishmael: An Adventure of Mind and Spirit by Daniel Quinn:

“The premise of the Taker story is ‘the world belongs to man’. … The premise of the Leaver story is ‘man belongs to the world’.”

Said the ape to the man, his student. Have you read Ishmael? If you have and explained it to a friend and didn’t sound like an idiot, you are smarter than me.

The average American consumes the amount of resources of 32 Kenyans. If all 6.5 billion earthlings were Americans, we’d need five planets! We consume too damn much! And a day that celebrates consumption, seems as responsible as a Free Beer Friday day for an alcoholic.

Our society tells us to consume more because we aren’t good enough the way we are and all these things can make us more fully realized humans. But at the same time, we should conserve more. A recent essay by George Monibot in the Guardian argues that economic growth can’t be reconciled with sustainability:

Governments urge us both to consume more and to conserve more. We must extract more fossil fuel from the ground, but burn less of it. We should reduce, reuse and recycle the stuff that enters our homes, and at the same time increase, discard and replace it. How else can the consumer economy grow? We should eat less meat to protect the living planet, and eat more meat to boost the farming industry. These policies are irreconcilable. The new analyses suggest that economic growth is the problem, regardless of whether the word sustainable is bolted to the front of it.

It’s not just that we don’t address this contradiction; scarcely anyone dares even name it. It’s as if the issue is too big, too frightening to contemplate. We seem unable to face the fact that our utopia is also our dystopia; that production appears to be indistinguishable from destruction.

—

Anyhow, that’s why I’m fasting. I’ll be thinking about some of the above on Friday, but mostly I’ll probably be thinking about pizza. If you want to join me, I’d love to have some online company at #BlackFridayFast.

Now here’s that EATING excerpt I keep alluding to.

—

From WHERE AM I EATING? An adventure through the global food economy

On the day Americans do what Americans do better than anyone else on the planet—consume—I chose to consume nothing. I fasted on Black Friday.

In the morning, I made the kids breakfast without so much as an eye twitch from lack of caffeine or sugar. But by lunch, I was in a friend’s vacant office writing this book—a book about food—my nose buried in a bag of chocolates like a street kid huffing glue for a fix.

By dinner, I was experiencing hunger like I hadn’t known hunger. It no longer existed in my stomach; we all know hunger like that—the kind that twists, the kind that growls. This was lightheadedness fueled by lack of sustenance. Biological systems were finding fuel in untapped places.

I made dinner for the kids—penne pasta in red sauce with sides of carrots and grapes. Normally in the course of cooking, which I’m learning to do, I would have popped in a few grapes or carrots.

Yes, this hunger was different. My head hurt. My limbs were heavy. My stomach wasn’t any more hungry than usual, but my body was becoming increasingly lethargic.

When the kids were in bed, I read about the events of the day. A local story reported from Victoria’s Secret that more than the prices were half-off; the shoppers’ clothes were half-off, too, as they refused to wait for the dressing room. Two people were shot in a Walmart parking lot in Tallahassee by a fellow shopper. People pushed and shoved their way to 40 percent off gaming systems. Some workers at Walmart were thinking of striking even though it would likely mean that they would lose their jobs, because they weren’t protected by a union.

I added six hours onto my fast because I wanted to experience sleep after not having eaten for an entire day. Falling to sleep was easy at first, but I became too hungry to stay asleep.

I dreamed about food. I dreamed about potato chips—salty, high-caloried potato chips. Then I dreamed about bacon.

When I awoke at 5 AM, I had bacon on the brain. The house was cold and the desire to stay in bed was strong, but the desire to find bacon was stronger. We were out.

Nine minutes to go.

I thought back to our Thanksgiving lunch yesterday, where my lobster dip was a smash-hit, and Annie’s Grandma Betty prayed, “Lord we give thanks to thee for the food about to nourish our bodies. We ask you to bless this food and the hands that prepared it.”

The spread of food was three tables long. There was a lot to be thankful for, including all of the family members with their heads bowed.

In the throes of a famine, some parents stop caring for their children. They become consumed with finding food and abandon them. The moral become immoral. Crime rates rise. Anger, delusion, and hysteria rule.

My small famine isn’t an act of solidarity with the world’s one billion undernourished, it is simply to know hunger, to know what it feels like to be without food. But I know that my next meal will come, and I know where it will come from.

Food isn’t a luxury; it is a biological necessity, a human right. We should treat it as such. We should give thanks for it.

Love isn’t possible without food, nothing is.

We can’t live without food, and we can’t live without the people who catch, pick, and grow it.

I give thanks for the food about to nourish my body and to the hands that prepared the food I’m about to eat…wherever in the world they are.

November 24, 2015

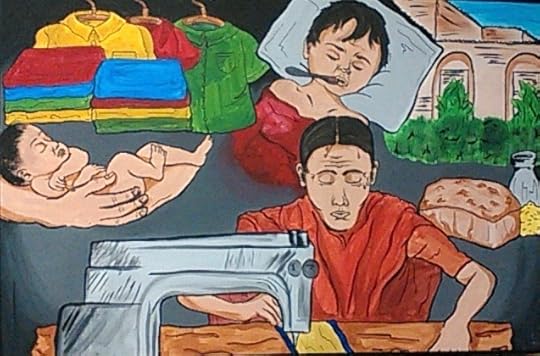

Painting by Austin Peay State U student Toni Agee

APSU students are awesomely talented. I only saw the winners and honorable mentions of their creative response assignment for WHERE AM I WEARING. The fact that student Toni Agee’s painting was neither is just a testament to how awesome these projects were.

Behold…

When we work it may look like we are concentrating on the task at hand, but often we’re focused on more important things, such as why we are working in the first place. Even the person who makes your clothes has a rich inner life.

Well done, Toni!

I see my son dead on a beach: How I think about the Syrian refugee crisis

A few things have shaped the way I see the Syrian refugee crisis. I thought I would share them:

#1: The photo of the boy on the beach

The pictures of 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi lifeless on the beach have haunted me for months. You should see them. They are here.

I can barely handle seeing the photos. I see them and I see my own son, which is terrifying and exactly how we should see the world. I see the shirt I helped him put on, the shoes we bought him. When confronted with a harsh reality, we should see ourselves and our family members in the mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters impacted by that reality.

Empathy should be a our default setting.

When I look at the Syrian refugees, I think about what it must be like to be forced from my home. What about my cat, my favorite coffee mug, our family photos, and all of the other silly and serious things that make up a home? Like, do you go the ATM? Fill your pockets with cash?

At some point you step out your front door for the last time and you don’t have any idea where you’ll sleep next, if you’ll be safe, what this all means for the future of your kids.

I see my family walking. I see my family on the boat. I see my Griffin dead on a beach. I see myself as the father, who described the horrible events to the Globe & Mail:

“The Turk [smuggler] jumped into the sea, then a wave came and flipped us over. I grabbed my sons and wife and we held onto the boat,” Mr. Kurdi said, speaking slowly in Arabic and struggling at times for words.

“We stayed like that for an hour, then the first [son] died and I left him so I can help the other, then the second died, so I left him as well to help his mom and I found her dead. … What do I do. … I spent three hours waiting for the coast guard to come. The life jackets we were wearing were all fake. …

“My wife is my world and I have nothing, by God. I don’t even think of getting married again or having more kids. … I am choking, I cannot breathe. They died in my arms.”

This is the reality for 4 million Syrians and 3 million Iraqis.

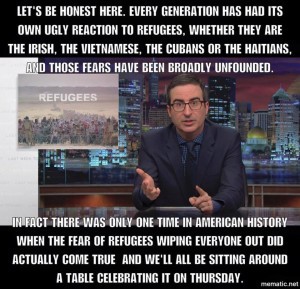

And the United States has promised to take in 10,000 (1.25%) and many are arguing against it because they might be terrorists. John Oliver points out that to date 1 in 261,000 of the refugees we’ve taken in have been part of terrorist plots.

Yoda said it best: ”Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.”

#2 John Oliver: Explaining the refugee vetting process:

“If you’re a refugee, first, you apply through the United Nations High Commission of Refugees, which collects documents and performs interviews. Incidentally, less than 1 percent of refugees worldwide end up being recommended for resettlement, but if you’re one of them, you may then be referred to the State Department to begin the vetting process. At this point, more information is collected, and you’ll be put through security screenings by the National Counterterrorism Center, the FBI, and the Department of Homeland Security, and if you’re a Syrian refugee, you’ll get an additional layer of screening called the Syria Enhanced Review, which may include a further check by a special part of Homeland Security—the USCIS [United States Citizenship and Immigration Services] fraud detection and national security directorate.

“Then, you finally get an interview with USCIS officers and you’ll also be fingerprinted so your prints can be run through the biometric databases of the FBI, Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of Defense. And, if you make it through all that, you’ll also have health screenings which, let’s face it, may not go too well for you because you may have given yourself a stroke going through this process so far. But, if everything comes back clear, you’ll be enrolled in cultural orientation classes—all while your information continues to be checked recurrently against terrorist databases to make sure that no new information comes in that wasn’t caught before.

“All of that has to happen before you get near a plane! This process typically takes 18 to 24 months once you’ve been referred to the UN by the United States. This is the most rigorous vetting anyone has to face before entering this country. No terrorist in their right mind would choose this path when the visa process requires far less effort.”

You can watch the whole thing here:

#3 Hoosiers choosing love not fear

In the Huffington Post I wrote about a group of Hoosiers, roughly 100 so far, who have donated to the Syrian family turned away by the state of Indiana. Read Hoosiers extend hospitality to Syrian refugees despite Indiana’s position.

Here are two excerpts from the piece:

One family and $1,500 (or even $20,000) by no means makes a dent in the human tragedy and political quagmire playing out in Syria. But if there’s ever going to be relief for the refugees or a solution to the crisis, it will likely begin with the compassion of individuals—a citizen, a president, a religious leader, maybe even an English professor from Indiana—and ripple out in concentric circles of compassion influencing others to think, feel, and act.

…

Sometimes I’m ashamed to be a Hoosier and sometimes I’m ashamed to be a human for that matter. But having a front row seat to this small act of hospitality, reminded me of a few things: that we are often more than just divisive Facebook posts; that the compassion and hospitality of one can inspire the compassion and hospitality of 50; and that every human life has a purpose.

If you are interested in donating to the campaign, visit Hoosiers Welcoming Syrians.

—

The hardest part of all this is what do we do? I see the photos and news reports and I feel them. Years from now there will be memorials about these families. There will be mottos, which will be some version of “never forget.” We must not become desensitized to these reports. We must “never forget” as they are happening. We must witness. We must remember.

But the reality is we will forget. We will move on. As Christoper Dickey, Daily Beast editor and long-time foreign correspondent told CNN: “The ability for the public to forget a crisis like this is one of the most terrifying aspects of it.”

November 10, 2015

My British filmmaker friend who taught me about the American town that has been on fire since 1961

The small appalachian town of Centralia, PA, has been on fire since 1961. Last month NBC announced that Centralia will be the focus of a new pilot. Deadline.com describes the show:

“Centralia is a dark character-driven genre soap based on a real town in central Pennsylvania where an underground mine fire has been burning for over 50 years. The remaining few residents of this ghost town are determined to preserve their homes butremain unaware of the evil that is slowly making its way to the surface.”

I’m not sure what the “evil that is slowly making its way to the surface” is, but it can’t be more disastrous and sinister than what actually happened. Few people have focused on the environmental and social disaster of Centralia more than filmmaker and documentarian Simon Tatum (The Last Freak Show). Simon has been visiting Centralia for over a decade, befriending the few remaining residents, and shooting hundreds of hours of footage.

Simon and I share a passion for telling people-focused stories to highlight complex issues. Simon reached out to me after reading my first book, and we’ve stayed in touch ever since.

There are few people who have thought more about the story of Centralia than Simon, so I reached out to him to share what actually happened to the town and what drew him to the story.

///

Kelsey Timmerman: What happened in Centralia?

Simon Tatum: Centralia was an ordinary little mountain town with around 1,100 residents which sat on top of one of the largest coal seams in the world – The Mammoth Coal Vein – so it revolved almost entirely around the coal mine.

In the spring of 1961 the town council ordered a landfill site on the edge of town to be torched as a clean up project for Memorial Day. The landfill site was was on an old strip-mining pit that hadn’t been sealed properly. That day the flames found their way down to the coal seam and slowly began to spread beneath the town.

There were various attempts to extinguish it but the resources were never there to be truly effective. The town carried on as normal not really realising the extent of what was happening beneath their feet. The fire was growing, being fed oxygen from all angles by the mass of mine tunnels that snaked their way through the mountain.

Twenty years later, in 1981 a twelve year old boy named Todd Domboski was playing in his grandmother’s garden when he noticed a wisp of smoke spiraling up from the lawn. He went to investigate and the ground just opened up beneath him. He managed to grab onto a clump of tree roots and was pulled to safety, but the hole itself was more than 80 feet deep. Smoke and noxious steam billowed out around him as the roar of the fire screamed underneath him.

The town began to panic. The ground began to subside, the highway that ran through the town began to buckle and split, smoke and steam pouring out. Suddenly the government started to take notice and eventually $42 million was allocated to relocate the entire town. The majority took them up on the offer, but there were a hardcore few that refused to leave. Some believed the government wanted them out in order to mine the billions of dollars of coal beneath them. Others just didn’t want to be forced out of their homes. So the government simply tore the town down around them.

And so the town went on. For thirty years now the remaining residents have lived in the still burning ghost town. At its height the smoke and steam was dramatic – billowing out, filling the air, the stench of sulfur permeating everything.

Today there are still six people living in Centralia . . . I think. The fire is still burning and the town’s almost gone. Nature is finally taking it back.

KT: So you’re over in England helping bring fictional worlds like Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride to life on the big screen, and you think, “Screw it, I’m going to a ghost town in rural, Pennsylvania?”

ST: “I was 25, I’d just been given the job of 3rd Assistant Director on Corpse Bride, but by that time I’d begun to lose my passion for filmmaking. I’d been an AD for sometime, working on various high end features, commercials, and music videos and somewhere along the way I’d started to forget why I wanted to be there in the first place. So my mind switched to documentary – an entirely different strand of filmmaking that would allow me to do something that felt meaningful, something that would enable to me to head out into the world and experience it in a way few people get to.

So I looked for a documentary subject, something I could dive into as a one man band, self-fund, self-shoot. At the time my dad was reading Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods. In it Bryson mentions the town of Centralia, the mine fire that’s been burning beneath it for forty years and the collection of townsfolk who refuse to leave. Immediately I knew that was the subject I’d been looking for. So I began searching for a way in and found an online forum set up by the community of Centralia to communicate with each other. I posted that I was intending to make a film about the town, focusing not as an oddity but focusing on the people themselves as their community is slowly destroyed around them. I got a few replies from people curious about the town and it’s weird history, nothing useful, until one day I received a reply from someone calling themselves “Coalcracker.” This turned out to be John. He was the youngest resident in Centralia at 34, ferociously passionate about the town and keeping it alive. He would be happy to meet me and be on camera. He said it was my intention to focus on the people that made him decide to write to me.

So I booked a ticket, packed my camera, flew from London to Philadelphia, rented a car and headed into the mountains. I was horribly nervous. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I was heading into No-man’s land with no idea if I’d be welcomed or really what kind of story I’d find. I’d never done a documentary at that point, so I was riddled with anxiety of every kind – Who do I think I am? I’m not a filmmaker, these people will see me for the imposter I am immediately and probably chase me out of town with a shotgun.

KT: Once you got there how were you received?

ST: There was skepticism from some but generally I was welcomed with great warmth. They mostly embraced the opportunity to talk about the town they loved and reminisce about the tight-knit community that has been all but torn apart.

John was my way in. At our first meeting he was shy and polite. I liked him straight away. But he had a fierce anger towards the government and the fear-mongers that took his town. We spent about three hours walking around town on that first day. It was late September and cold, the smoke and steam billowing furiously out of the split ground. He told me that he would never leave, that he would die there.

Over the next two years we developed a strong friendship. I went back to Centralia repeatedly and each time I saw him he’d become more and more isolated from the outside world. He lived in a beautiful, pristine house right in the middle of the town. He’d shared the house with his grandfather who’d passed away a little while ago and so the place was hugely special for him. I think he found it difficult to let go of the image of Centralia as it used to be – a place he’d spent such happy times with his grandfather. What remained of the town was kept pristine by John. He’d spend every weekend mowing the grass all over town, re-painting the benches and fences and generally fixing what was broken. Decorating the place at christmas. It was extremely impressive. His house now stood alone, on one side was the manicured lawn, on the other side smoldering scrubland. The final time I saw him we went for dinner at a dingy local bar over in the next town. He was at the lowest point I’d seen him. We talked for a long time about his obsession with the past and his fear of the future. I flew back to England and months went by before we spoke again. He told me that our conversation that night had a profound effect on him. The next time we spoke, he’d sold his house and moved away from Centralia for good.

KT: Did you ever hear from John again?

ST: A few years later I was in the U.S. shooting a TV series. I was heading down to West Virginia when I decided to take a detour and head back to Centralia. When I got there I couldn’t believe it. It was almost as if the town never existed. John’s house was gone. The pristine grass and trimmed hedges had become wild. Nature had taken the town back.

Then, last year I saw a post on a Centralia facebook page by a woman whose name I didn’t recognize. She’d posted a Christmas photo of herself and her partner holding their new baby. Her partner was John looking happier than I’d ever seen him. It puts a smile on my face just thinking about it.

Over the course of those years, I shot hundreds of hours of footage, interviewed all the key people from the story of the town – many of whom have passed away now, including Miss Centralia 1919 – but the film itself was never finished. My time there was really my film school. It was there that I made all my mistakes, learning the art of making a film by going out there and just doing it.

KT: I’ve been following your career for the past few years and I know that you’ve had some incredible adventures – you’ve filmed Amazonian tribes, Thai elephants, American sideshows. One time you even asked me if I would shoot a magician with a revolver! Did you forget about Centralia? Write it off as learning experience and move on?

ST: The fact I never finished it always bothered me. I never felt I was done with it as it was always really special to me. So now, twelve years later, the film is finally being completed. I’m in the unique position of being able to tell the story over the course of twelve years, from the perspective of those at the heart of it as well as incorporating myself and the filmmaking process itself. So it’s really becoming a film about the making of a film.

The place became more to me than just a film subject. I’d take every opportunity I could to fly back out there. To this day, I still find the smell of the burning sulfur comforting.

–

To learn more about Centralia, Simon recommends Fire Underground: The Ongoing Tragedy of the Centralia Mine Fire by David Dekok.

To learn more about Simon visit simontatum.com.

November 9, 2015

A Liberal on Lazy Liberalism & Faux Outrage

I’m no anthropologist, but I like to think that my degree in anthropology has instilled a certain level of cultural sensitivity and empathy that fuels my work. That’s why I was shocked to receive an email that painted me as anything but culturally sensitive.

By holding up my Jingle These Christmas Boxers, I was sexual harassing the entire audience.

By saying, “the worst thing isn’t that we live in a world where child labor exists, but in a world where a mother who loves her child just as much as your mom loves you and my mom loves me sends that child off to work for the day because they have to earn an income,” I’m offending any audience members who don’t have mothers or mothers who loves them.

I took the comments very seriously and arranged to chat with my critic. The call lasted 90 minutes. Socially and politically my critic and I agree on most everything. We’re both pretty liberal. (Although I try to make my message and stories go beyond politics and bridge ideologies. I’m in the give a shit business: I try to make people care about our local and global neighbors.) But we could never see eye-to-eye on the criticisms that were leveled at my work.

I considered the criticism, talked to people I trust about them, and even lost a night’s sleep over them. I took them really seriously. But the more I thought about it, the more I felt like the critic was being overly sensitive. Hell, SpongeBob is more inappropriate than any joke I’ve ever told on a stage.

Anyhow, two weeks ago I was watching Bill Maher and he went on a rant about the faux outrage over Halloween costumes deemed inappropriate, and, in a weird way, he captured how I felt about the email I had lost sleep over:

“…banning a hobo costume doesn’t make the homeless feel better. It makes you feel better. This is the lazy liberalism in which scolding has become a substitute for actually doing something.”

Watch Maher’s rant starting at the comment above

(To be clear I think you should think twice before painting your face black for Halloween or dressing as Caitlyn Jenner. So please don’t level that criticism at me.)

Faux outrage is shouting on Facebook or Twitter. Real outrage moves us to action to address injustices, to change a system that needs changing, to live lives of justice not just critiquing how others are doing it wrong. Faux outrage is pointing a finger at someone else and saying, “You are doing it wrong,” really outrage is pointing a finger at yourself and saying, “What can I do?” It’s putting ourselves in uncomfortable positions for our beliefs.

I’m not saying that I’m doing all of the above, but I’m trying. I’m pointing the finger at myself. I’m acting. And the people who I look up to are those who act, not those who shout.

There is plenty of room to criticize my work, maybe one day I’ll share all the ways, but getting hung up on a pair of underwear is not a productive thing to do in a conversation about global slavery.

One other takeaway here, and perhaps more relevant to the criticism I received. It’s rare that I don’t get something out of a book I read, a movie I watch, or a talk I hear. Sure, I also rarely agree with something 100%, but I try to find the value in a thing. Look for the value, what you can learn. When our political correctness blinds us to a larger message, a more productive conversation, or a different perspective, it keeps us from growing and learning.

Don’t just scold. Act.

Don’t just shout. Listen.

Tell me how I’m wrong.

October 29, 2015

Join me in kickstarting Krochet Kids’ World’s Greatest Beanie

One of my absolute favorite clothing brands is Krochet Kids. A few years ago I had the chance to meet one of the founders of this nonprofit apparel brand, Kohl Crecelius, when he was speaking at Ball State.

Kohl and his buddies, Travis and Stewart, were avid snow sports enthusiasts in high school and wanted to have some headwear that was different than anyone’s on the slopes. They learned to crochet beanies and the friends started filling custom orders.

After high school Stewart traveled to Uganda on a trip that had nothing to do with beanies or crocheting and realized how little opportunity existed for the people there.

(This is massive paraphrasing)

They thought if a couple of dudes from Washington state could learn to crochet, anyone could. They went to Uganda and taught the locals, who started making beanies and signing each one they’ve made. Now Krochet Kids produces much more than just beanies, but they still make beanies.

Which brings us to: THE WORLD’S GREATEST BEANIE!

They set out on a quest to find the best design, material, and an awesome story for a beanie. I can’t wait to have the sweet, soft alpaca wool hugging my ears during Indiana’s harsh winter.

Sometimes I talk about a cheesy idea called the Axis of Awesome. Basically, the way each of us can produce the biggest impact with our lives is by operating from the spot our skills, passions and curiosities, and our life experiences line up. Krochet Kids is a perfect example of this and is one of the many reasons I’m proud to support them.

October 21, 2015

I’m so 2015 that I’m on periscope

I don’t mean to brag, but like 16 people follow me on periscope. We should be periscopians together.

I’ve had several folks ask me what I think of it. Here’s essentially what I told my friend Mark Benson:

I think it’s more intimate since it is more immediate. The thing I like best is what I liked about Instagram early on or any other new social platform–how quiet it is. I follow a few people and a few people follow me. It’s much more manageable to interact and pay attention to what others are doing compared to thousands of folks on Twitter.

But as Mark pointed out: “Call someplace paradise, and kiss it goodbye.”

My first try at Periscope was walking out on stage at UNC-Greensboro in an auditorium before 1,000+. It was fun walking out with my periscope friends.

Last night I shot the video below touring my new co-working space at the Downtown Business Connector in Muncie. I was waiting with my Facing Project co-founder, J.R., to lead a writer training for Muncie’s Facing Racism Project.

The video format isn’t the best. I didn’t know you had to enable the videos to save to your camera roll. Otherwise the video is gone within 24 hours. But I really wanted to show you my office so I found a work around that allowed me to record the video from my phone to my computer. (Note: This only works on an updated iPhone to an updated Mac. I know because I had to update both operating systems.)

I thought the whole point of periscope was to produce a temporary video that wouldn’t live on forever, but this workaround eliminates that.

So as always don’t be a jackass and post it on the Internet.

October 19, 2015

How Fair Trade Actually Changes the World

(With kids in cocoa region of Ivory Coast)

You’re standing in the aisle. Before you is a bar of normal chocolate and a bar of Fair Trade or ethically sourced chocolate, or a pair of regular underwear and a pair of Fair Trade underwear, or a pair of regular chocolate underwear and a pair of Fair Trade chocolate underwear. (Just kidding about that last one. I don’t think Fair Trade is in the “novelty” market yet. Someday!)

You have a choice to make: Be fair or be normal?

Choose the product that supports millions of farmers around the world, sets certain social and environmental standards, provides producers with a guaranteed minimum price for their product and a social premium, or choose the one that is business as usual?

If you buy the fair option, does that change the world? This one act at this moment, does it change the life of a farmer or factory worker?

Not really.

Sure, if enough of us do it, collectively Fair Trade and ethical consumption can change the lives of farmers and factory workers around the world. I’ve seen the change first hand in the lives of cocoa farmers and coffee farmers. But that small single act in a store in Oklahoma or in Indiana or wherever by itself contributes a small part to that change.

But something much bigger happens in that moment.

You stop to think about that bag of coffee or pair of underwear and you consider that it came from somewhere else and someone else. You think about a family supported by the work, sending kids to school, paying for books and medicine. You think about a world beyond your own needs. A world connected.

That moment is a small act of gratitude that doesn’t necessarily change the world immediately, but it changes the way you see the world. That changes the way you interact with the world as a consumer, producer, giver, volunteer, as a local and global citizen, and that, my friend, can change the world.

–

My friends at Fair Trade USA are celebrating Fair Trade month. You can learn more about Fair Trade and the ever-growing list of Fair Trade products at BeFair.org.