Mike Moyer's Blog, page 8

October 18, 2017

Entrepreneurship Isn’t for Everyone

I thought this was a funny Sprite commercial (translated). As crazy as it sounds, not everyone wants to start their own company.

Why Slicing is Better than Pricing

I hear it all the time: “We raised $10,000 from an angel investor in exchange for 10% of our company,” or some other variation of [person] gets X% for [small investment].

As innocent as this sounds, it means that the company has essentially sold equity in the company. Selling a fixed chunk of equity for a fixed sum is equity financing and it means that a meaningful company valuation can be determined, or at least implied, during the investment round. For example, selling 10% of the company implies that the company had a pre-money valuation of $90,000 and, therefore, a post-money valuation of $100,000. This is called a “priced” round.

Extreme caution should be taken when selling equity for cash to avoid legal, ethical and tax consequences.

Legal Issues

You may very well be in violation of securities law if you sell equity to unaccredited investors or without proper documentation and disclosures. Even crowdfunding requires extensive and expensive documentation, known as placement memorandums (PPM), to secure investment in exchange for priced equity. PPMs are usually created by lawyers and provide detail with regard to a businesses operating history, business plans, financial performance & forecasts, and full disclosure of the plethora of reasons why the company might fail.

Ethical Issues

In my opinion, most founders are not qualified to properly value their own company. Neither are their moms, dads, buddies, rich uncles or aunts, lawyers or anyone else in their personal networks. Likewise, angel investors, who are investing their own money, aren’t qualified either. Valuation discussions are highly-biased, emotional, personal. Even those with the best intentions can be led astray by desperation, ignorance or an overly-optimistic view of the future.

Tax Issues

Another problem with setting a premature valuation for your company is that the IRS (or other taxing agency) may deem subsequent equity allocations as taxable income which means the recipient will pay tax (in cash) even if the stock turns out to be worthless (the most common scenario).

Slicing Pie allows a company to divide equity in a company before a valuation can be set. Until a value can be set, the value is $0. If nobody is willing to buy it (your equity) it has no value. Think about it, what the value of a product that nobody wants? So, unless the company is raising a serious amount of money with professional investors you should probably be slicing Pie instead of pricing Pie.

When to Price Instead of Slice

A company that has created a repeatable, sustainable business model, produced hard assets, intellectual property or cash flow, on the other hand, is worth something. These are things you produce while you’re using Slicing Pie. When you have these things, it’s time to price and “bake the Pie.”

A professional investor who invests other people’s money (like a VC) is much better qualified to make a financial offer for equity, especially if he or she has the proper documentation including a business plan, due diligence reports and a Private Placement Memorandum (PPM).

This doesn’t mean they’re aren’t unscrupulous professionals, but a few things are usually true about professional investors:

They have a fiduciary responsibility to their clients

They have seen a lot more deals than the average angel, founder or founder’s mom

They don’t operate in a vacuum; other VCs are also looking at or are part of the deal so you’ll have multiple experts looking

Compared to your friends and family, it’s much harder for them to claim that you misled them (they should know better)

Of course, you can, and should, shop your deal around to negotiate the best terms, but you aren’t going to trick a professional investor. Different VCs will value your company based on different criteria, to some you will be more valuable than to others. Of course, they could trick you, so be sure to surround yourself with advisers or attorneys who can spot red flags.

I’m not very experienced with equity crowdfunding, but it appears that they are usually lead by a professional investment group and require similar documentation.

A professional or crowdfunding round should raise enough money to cover all the corporate expenses (including salaries) until breakeven or the next funding round. This means that the Pie will stop accumulating slices and can be “baked”. Baking the Pie means that share vest or are otherwise fixed and are now subject to the terms of the investment.

Pricing Without Professional Investors

Some companies have no intention of raising money or, they intended to, but decided against it because they reached cash flow breakeven and don’t need or want money for growth. As in a professional round, a breakeven company is meeting all its financial obligations and slices are no longer accumulating so the Pie bakes.

If your company has outstanding convertible notes, KISS or SAFEs, you will need a valuation to convert the equity. For this you will need to find a professional accountant who is certified for 409A valuations. A 409A valuation is common when setting the strike price for option pools, but can also be used to convert a convertible loan, KISS or SAFE (see below) in the absence of a Series A round. Check out Capshare for a free, DIY 409A tool (with limitations).

Pricing a Pie is much trickier than slicing a Pie. During the bootstrapping stage, stick to Slicing Pie. The contributions made in Slicing Pie are the bets placed on the future price of the Pie.

October 11, 2017

Lump-Sum Payments

Occasionally, an individual will need (or want) cash for their own use. If the company is in a position to provide cash, it can do so by making a lump-sum payment to the individual in any amount. In Slicing Pie, cash payments reduce at-risk contributions so when a lump -sum payment is made it will reduce the individual’s slices. To make sure the reduction is fair, you should apply the payment in the following way:

First, the lump-sum payment will, in effect, reimburse the individual for cash contributions reducing slices at the cash rate until all cash payments have been reimbursed.

Second, any remaining amount will be applied to the individual’s Well balance, if any. This will not reduce slices, but will decrease the person’s ownership in the Well.

Third, the remainder will be applied to non-cash contributions.

I do not recommend making lump-sum payments in excess of the individual’s total contribution. Also, I don’t thinks it’s a great idea to take cash out of the Well to make Lump Sum payments unless the person getting the payment is the only person with cash in the Well. If not, and you must take money from the Well, enter the withdrawal after entering the Lump Sum (this only matters if the Lump Sum recipient is also part of the Well.)

By applying the payments in this order, you make the most efficient use of the money and reduce slices appropriately.

For example, Tom is a Grunt who has 4,000 slices and a $1,000 balance in the Well. His slices break down like this assuming his Pie is using the the recommended cash multiplier of four and non-cash multiplier of two:

Contribution

Amount

Slices*

Cash

$250

1,000

Non-Cash

$1,500

3,000

TOTAL

4,000

He asks the company for a lump-sum payment of $1,750.

The payment is applied first to his cash contributions: $1,750 – $250 = $1,500. This eliminates slices from cash contributions:

Contribution

Amount

Slices*

Cash

$0

0

Non-Cash

$1,500

3,000

TOTAL

3,000

Next, the remaining $1,500 is applied to his Well balance which is $1,000 (see above). $1,500 – $1,000 = $500. This does not affect his slices, but does reduce future slices he might get when Well money is used.

The remaining $500 is applied to his non-cash contributions: $1,500 – $500 = $1,000.

Contribution

Amount

Slices*

Cash

$0

0

Non-Cash

$1,000

2,000

TOTAL

2,000

Tom now has 2,000 slices in the Pie and $1,750 in his pocket.

It’s logical that cash payments would first cover cash expenses. It’s also logical that if Tom needs money it would come out of the Well. By reducing cash expenses first, you remove slices from the Pie creating a natural disincentive for Tom to ask for lump-sum payments. If you reduced the Well first and allowed the cash slices to remain, Tom would not experience any consequences for asking for the money. Slicing Pie always aligns incentives with the interests of the firm.

If you were to apply the lump-sum to non-cash payments before the Well balance you would be allowing Tom to get slices for paying himself (if the money was drawn from the Well). This actually creates an incentive to ask for the money which is also gaming the system which is not in line with the spirit of the model.

To illustrate this, pretend Tom has $1,000 in the Well and $1,000 in non-cash contributions:

Contribution

Amount

Slices*

Cash

$0

0

Non-Cash

$1,000

2,000

TOTAL

2,000

If you apply the payments to non-cash first, he now has an incentive to ask for a lump-sum payment. The money would eliminate his non-cash contribution:

Contribution

Amount

Slices*

Cash

$0

0

Non-Cash

$0

0

TOTAL

0

But, if the money was drawn out of the Well, Tom would receive slices:

Contribution

Amount

Slices*

Cash

$1,000

4,000

Non-Cash

$0

0

TOTAL

4,000

So, Tom has basically paid himself using Well money which leave less money in the bank and rewards him with twice the slices! This is not fair and, therefore, against the rules of Slicing Pie. Gaming the system would be grounds for termination for cause.

There is nothing wrong with making lump-sum payments to Grunts who need money as long as you apply the payment properly and reduce slices accordingly. Slicing Pie not only ensures a perfect split, but also aligns incentives of all participants.

September 26, 2017

The Pie Slicer Update: Fall 2017

I am pleased to announce the release of a major update to the Slicing Pie Pie Slicer online software which will be live on Monday, October 2, 2017.

Used by thousands of Grunts, the Pie Slicer software is the easiest way to track and manage a perfectly fair equity split during the bootstrapping stage of a company’s development.

[image error]The biggest change is a complete overhaul of the graphical user interface. It has been updated and reorganized a little to provide a better overall experience. We fixed the overall look of the program and some little things, for instance, each person’s color is consistent on all screens and graphs.

Additionally, the UI is responsive making entries from a mobile device more enjoyable!

[image error]In addition to the UI, we are rolling out a number of new features:

Repeat Contributions

Now you can set a contribution to repeat on a daily, weekly, monthly or annually. This makes it easier to track predictable contributions like a weekly salary, monthly office rent or an annual software license.

Lump-Sum Payments

When cash flow is sporadic it’s difficult to predict when a partial salary can be paid with any regularity. In many cases team members are paid when cash is available depending on what the company can afford. These payments can be logged as Lump-Sum payments in the Pie Slicer. Making a Lump-Sum payment will reduce someone’s at-risk contributions and, therefore, reduce his or her slices in the Pie. The payment deducts cash slices first, then non-cash.

Contribution Approvals Restriction

Too many people adding contributions willy-nilly can get a little hard to manage. Pie owners/admins can set a user account to require approvals for each new contribution. So, when a restricted user logs a contribution, it is held as pending until the Pie owner approves it. Owners get an email alert when a new contribution is waiting to be approved. This feature can come in handy for new participants who are still getting used to working in a Slicing Pie company, people who work part time and make sporadic contributions, or people who have received a performance warning and are under close supervision.

View-Only Restriction

Pie owners/admins can set a user account to view-only which prevents the participant from being able to log their own contributions. This is useful for small or infrequent contributors. For instance, a Pie owner could set up a repeat allocation of slices in lieu of rent payments and provide a view-only account to the landlord so he or she can monitor his or her slices.

Analytics Reports

The Pie Analytics Reports have been updated based on our conversations with professional investors who take an interest in the activities of the company during the due diligence process. Managers can now see a breakdown of contributions by person, project or type in both slices and fair market value. These reports give managers and investors insight into how the team invests their time, money and other resources.

[image error]Daily and Weekly Email Summaries

Pie participants can request a daily or weekly email summary showing their own contribution activity and that of the entire team. Summaries include information for all Pies in which the user is participating.

Re-Hire a Grunt

The recent update allows companies to re-hire participants who resigned or were terminated. This feature was requested by users. Sometimes a participant has to leave a company for personal reasons, but may want to rejoin when the situation changes.

Email the Team

Email all active participants with one click. This is a small, but useful feature that comes in handy when sending information to Pie participants that you may not want to share with everyone in the company (aka non-participants).

Pricing

Current Pie owners will never have a price increase on active Pies. Current pricing will remain in effect for new Pies until late October so sign-up now to lock-in the lowest price!

September 19, 2017

My Lawyer Says Slicing Pie Won’t Work

Sometimes, when a founder approaches an attorney with the Slicing Pie concept, the attorney will respond with something like, “grumble, grumble, that won’t work…grumble…tax issues…grumble, grumble…too complicated…investors won’t like it…grumble…hard to implement…blah, blah, blah…”

This is an understandable response.

When a lawyer hears about Slicing Pie she isn’t thinking, “Yay! A chance to learn and apply new legal concepts in the lucrative and rewarding area of early-stage business formation work!”

It’s more likely that she is thinking, “oh brother, I’m not making a dime on this corporate formation work and now this founder wants me to implement some convoluted variable-compensation program that’s going to be a nightmare to administer.”

Startups companies usually aren’t the most lucrative opportunities for lawyers, especially during the formation stage. Many lawyers like working with startups, however, not only because it’s fun, but also because it can lead to interesting and profitable legal work down the road.

Corporate formation includes picking a type of entity, filing with the government, and executing a number of fairly standard contracts like shareholder agreements and operating agreements. It’s not terribly interesting work and it does not pay well even when founders want customizations on the contracts. However, it can be a necessary evil for start-up attorneys because when it’s done wrong it can be difficult to unwind. It is for this reason (and others) that attorneys tend to stick with what they already know.

Slicing Pie concepts are new and often run counter to traditional thinking. When a lawyer tries to incorporate a high-level introduction of Slicing Pie with her intimate understanding of traditional models she sees all sorts of red flags. For instance, issuing equity on a rolling basis can easily create unnecessary tax consequences, not to mention potentially time-consuming administration. Additionally, at first glance, Slicing Pie seems to have ambiguous outcomes which could turn off potential employees or investors. None of these problems are difficult to solve, but the solutions may not be immediately apparent.

Your lawyer, confused by Slicing Pie, will attempt to make an extremely compelling case why you should not use it and how much better off you will be if you use a traditional equity split model. After all, lawyers are professional argument-makers.

Faced with all the reasons why you should stick to a traditional model, a founder may start second-guessing the value of the Slicing Pie model and reconsider using it.

Don’t let this be you! Do not let your lawyer talk you out of using Slicing Pie.

Before you speak to your lawyer, be prepared:

Review the post on overcoming objections

Bring a copy of The Slicing Pie Handbook

Bring copies of the Slicing Pie summary sheets

Here are some talking points you can use during the conversation with a concerned lawyer:

Slicing Pie is a complete model for equity allocation and recovery. All the typical concerns that usually pop up are addressed.

Slicing Pie has been implemented by startups all over the world.

Slicing Pie companies face exactly the same tax issues faced by any other equity model and all the issues can be addressed.

Mike Moyer, the inventor of Slicing Pie, is happy to speak with any lawyer who is interested in learning about the model. He will also provide sample contracts and be on call to answer questions at no charge.

The goal of the conversation isn’t to teach Slicing Pie to your lawyer or even to convince her that it works. The goal is to encourage her to take the time to learn more about it as part of her professional development. A lawyer shouldn’t charge you for learning Slicing Pie or even to draft a basic agreement. Knowing Slicing Pie and having the tools to implement will benefit her legal practice and not just you as her client.

In my experience, once someone understands how Slicing Pie works it will be obvious why it works and implementing it will seem much more straightforward. Many lawyers won’t want to look into Slicing Pie because they have other, more important issues on their plate. Some are simply closed to anything new. Whatever the case, if your lawyer doesn’t want you to use Slicing Pie and isn’t willing to learn about how it works: find another lawyer!

September 11, 2017

Please Don’t Partition the Pie

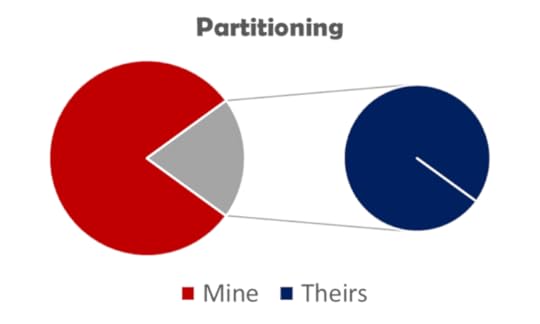

In the original Slicing Pie book, I proposed a concept called “partitioning” in which only a portion of the company’s shares would be subject to the Slicing Pie model. The remaining shares would be allocated to early founders or investors.

I regret this because it’s not really fair.

Unfortunately, the concept is in the original book and many of the subsequent translations of the book. If you have any of those, please enjoy the book, but ignore that part! The model in all the books is the same.

When I first started promoting the model back in 2010, I was still pondering the nuances of implementation, but over the years, I have gained more clarity on how to ensure the model keeps its promise of fairness. I removed the partitioning concept from The Slicing Pie Handbook and I caution people against using it.

Here’s why:

Carving out a chunk of equity for any person or persons simply re-introduces all the problems of a traditional fixed split—the problems that Slicing Pie is designed to solve in the first place. Fixed splits, not matter what their form, are bound to cause problems not only because the “right” number or percentage of shares is impossible to determine, but also because even if you could get it right, it would be wrong the moment something changes.

To make matters worse, the percentage of the company subject to Slicing Pie will instantly entitle the participants to the entire amount giving them what is almost certainly too much equity.

For instance, let’s say a founder wants to keep 80% for himself and leave 20% for new employees. He hires his first employee. The moment the employee shows up for work she will instantly be entitled to 20% of the company because she is the only participant in the allocation of 20%. If the founder hired two people at the same time, each of them would instantly have 10%.

The founder could try to address this problem by participating himself in the 20% portion alongside his employees, but they would no doubt wonder why he gets the 80% chunk too. And, if you think about it, why does he get 80%? What makes him so special?

Here are some possible reasons:

He wants to maintain decision-making rights. Okay, but there are other ways to accomplish this that still allow for a fair equity split.

He has an incredible idea. Okay, but Slicing Pie can accommodate ideas based on their fair market value which could be based on: 1) development costs, 2) royalties or 3) competitive offers.

He’s putting up all the cash. Okay, but Slicing Pie can easily account for cash contributions. If he’s putting up ALL the cash, including salaries, there is no need to use Slicing Pie and he needs to implement an incentive stock or option plan.

He’s a juggernaut in his industry. Okay, but Slicing Pie will reward his status based on the observable fair market value of his contributions. If he’s so powerful that success is a done deal, he should have no problem raising funding and won’t need Slicing Pie.

He just wants a big chunk. Hmmm…in this case ego and greed has gotten the best of him. Slicing Pie is designed to protect participants from this kind of behavior.

If you encounter a founder who thinks a partition makes sense, it may mean that he does not fully understand or trust that the model will do its work. Please put that person in touch with me and/or point them to the overcoming objections post on this blog.

If a founder does fully understand the model AND trusts that it’s fair then it’s clear that he is a person who is willing to benefit at the expense of others. Ego (“I’m so important the rules don’t apply to me” and, “I should have more than everyone else”) and greed (“I don’t want the rules to apply to me” and, “I want to have more than everyone else”) are powerful emotions and, understandably, difficult to ignore. But, people who can’t check their egos or are excessively greedy should be avoided, especially in a startup.

Even if you can get past how demoralizing it is to be taken advantage of, it’s likely that a leader like this will continue to make irrational, self-serving decisions can make it difficult for the company to survive.

If a founder is asking others to put their contributions at risk, he should be prepared to allow them to benefit from that risk. It’s not fair for him to benefit disproportionately from other’s risk. Everyone is in it together.

Think about it this way: imagine you invite a group of friends over to play poker. At the beginning of the game you said, “no matter what happens tonight I get to keep 80% of what you win.” How enthusiastic would your friends be about playing with you?

Of course, you could argue that it’s your house and you bought the drinks and it was your idea so 80% is “only fair.” They might be okay chipping in for drinks, but don’t count on them happily paying you off and don’t count on them wanting to play very long or coming back next week. Ultimately, they will resent you for taking advantage of them and the game won’t be much fun.

If it’s not fair, it’s not fun .

Startups are hard work, at least they should be fun too. Working for a company that undervalues your contribution sucks.

Even if a founder can get away with a partition, it does not make it fair. Maybe he can obscure the fact that he is taking advantage of others. This does not mean it’s the right thing to do. The world is full of examples where one group of people profits at the expense of others. It’s so common it’s cliché. People live with it because they don’t know a better way. When it comes to equity splits, Slicing Pie is the better way.

Slicing Pie will always give you the fair split. A partition is simply a fixed equity split with all the traditional fixed split problems. If you want to be unfair and you want to take advantage of others a fixed split is your best option. Slicing Pie can’t take a fixed partition and create a fair split because the underlying structure of the organization is fundamentally unfair.

If you want to be fair, use Slicing Pie. It will always give you what you deserve. If you want to benefit at the expense of others an old-fashion fixed split will give you the tools to let your ego and greed take control.

September 7, 2017

Slicing Pie and the Fat, Stubborn Grunt

One of the most common ways people discover Slicing Pie is when they are in the midst of renegotiating a previously executed traditional fixed split and are frantically looking for a better way. Because fixed splits are unfair, unwinding them can be difficult, especially if you’re trying to create a new fixed-split agreement which will lead to the same problems. I call this the “Fix & Fight” cycle and it can be very stressful.

It is often during the Fix & Fight cycle that someone finds Slicing Pie and shares it with the team. The good news is that if you found Slicing Pie after setting up a traditional fixed equity split, it’s easy to switch using the Slicing Pie Retrofit Guide and Spreadsheet. The tool will help you determine how many slices should be in your Pie and to whom they are allocated, providing a starting point from which to build.

But, what if one or more of your partners pushes back?

There are two primary reasons why someone would push back on using the Slicing Pie model. The first—and most common—is that he or she doesn’t “get it.” As obvious and logical as the model is, people sometimes raise objections. I’ve published a guide on overcoming objections that may come in handy. Once it “clicks” with your partner, you can move forward with the retrofit.

But, what if your partner understands Slicing Pie and still pushes back? This, too, is a solvable problem, but fixing it is a little more painful because you’re going to have to pay this person off with slices in the Pie.

Fat Grunts and Skinny Grunts

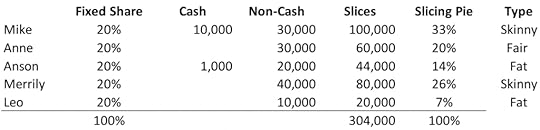

In a traditional equity split there are always two kinds of people: 1) those who have more than their fair share and 2) those who have less. I call those with more “fat Grunts” and those with less “skinny Grunts.” The first thing you’ll need to do is apply the Retrofit tool to see what a fair split should look like and who the skinny and fat Grunts are. Skinny Grunts rarely push back if it means they can finally get their fair share. Fat Grunts, on the other hand, have something to lose and may not want to be fair. Consider this split:

In this example, the team created an even split at the outset of the venture. Things didn’t move along as planned and the team applied the Slicing Pie retrofit formula to see where equity should be at this point in time. Mike is a skinny Grunt. He has less than he deserves. So is Merrily. Anson and Leo are fat Grunts because they have more than they deserve. Anne has the right amount, coincidentally.

Switching to Slicing Pie is the best way to ensure the fairest split, but if you’re dealing with a fat Grunt who won’t switch to Slicing Pie and you are a minority shareholder, you may be stuck in an unfair situation that probably won’t change. You will have to decide how much unfairness you can tolerate and quit when you’ve had enough of a toxic environment. Having a stubborn, fat Grunt on a team is demoralizing.

If, on the other hand, you have controlling interest or majority support you can simply force them to use Slicing Pie. Control can be contractual or based on the Pie. In this example, Mike, Anne and Merrily own 60% of the company and could successfully vote to move to Slicing Pie. They can’t, however, vote to take someone’s equity away from them. Doing so would cross an ethical line, even if it’s in the name of fairness. The three of them would have to get the others to agree so they can avoid potential legal battles.

If they forced the fat Grunts to take less equity the affected individuals would probably be quite angry and could cause problems for the company. Targeting a few people and deliberately diluting only their share looks bad to outsiders including judges, arbitrators and potential investors, employees or even customers.

This does not mean that their share is non-dilutable. In fact, there should never be such a thing as non-dilutable equity. It’s a deal breaker for any sane investor. All equity should be dilutable, but every team member should experience the same dilution. Yes, during a Slicing Pie retrofit you will be asking some people to give up slices. Most will do so willingly because they value fairness. Those who don’t do so actually can make a pretty compelling case that they shouldn’t be targeted. Many equity splits are handshake deals, but some are in writing. But, according to most legal jurisdictions a contract—verbal or written—may be binding. However, just because it’s legal, it doesn’t mean it’s fair.

Managing a Fat, Stubborn Grunt

Calling someone a “fat, stubborn Grunt” isn’t very flattering and it’s not meant to be. A fat, stubborn Grunt has shown himself to be the kind of person who is willing to benefit at the expense of the team. Not cool.

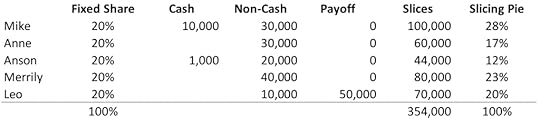

So, let’s pretend that of our two fat Grunts, Anson is cool with the switch to Slicing Pie, but Leo is a dick and won’t budge. You can still switch to Slicing Pie, but you have to pay Leo off with slices:

By allocating additional 50,000 slices to Leo, his share after implementing Slicing Pie will be the same as his share before implementing Slicing Pie so he will have no legal or ethical grounds for complaint. In fact, he actually got a nice bonus. Now if he tries to fight the deal he is less likely to curry favor with judges and arbitrators and less likely to be taken seriously if he badmouths the company in front of potential investors, employees or customers.

The next step is to separate from the employee. You need to do this for two reasons: 1) he has demonstrated that he cares little for the rights of others and 2) he has overcharged you for his services to date. Leo can now resign for good reason or the company can terminate without good reason. In both cases he would get to keep his current slices, but would not be contributing any additional slices so his share will dilute over time just like any other Grunt who stops contributing. When the Pie terminates at breakeven or Series A, Leo will vest or otherwise secure his shares along with all the other Grunts.

You could keep him as part of the team, but this episode will cast a pall over working relationships that probably isn’t worth whatever talents and skills he brings to the table. In the words of Taylor Swift, “’cause baby, now we’ve got bad blood, you know it used to be mad love.”

It’s kind of a drag having an absentee owner, especially one who took advantage of everyone. Equity owned by disgruntled former employees is called “dead” equity, and it should be avoided if possible. You can’t force him to give back or accept a buy out, but you can make him an offer. In Slicing Pie I recommend a buyout price of $1 per slice (or whatever your local currency is). In practice, however, parties can negotiate a buyout. So, if the company, or other team members, wants to make an offer to buy out the departing Grunt, go for it. If he turns the offer down you can keep negotiating or walk away. In this case you might start with $5,000 to buy out his slices which is the fair market value of his original contribution.

Leo’s stubbornness has led to an unfair pay off. However, everyone else on the team shared the expense proportionately, so while there is probably some resentment towards Leo, everyone else has been treated fairly relative to one another and working relationships remain intact.

This type of unfair bonus payment is unfortunate, but unwinding traditional splits often results in unfair payouts and legal fees. Allocating slices is probably the least expensive option and will make the transition as smooth as possible. The upside is that once Slicing Pie is in place, these types of disputes will be avoided.

August 29, 2017

Founder Investments – When to Just Say “No”

For the record, I’m not a CPA or an attorney, so you’ll have to check these strategies with someone knowledgeable with your local laws and practices.

One of the most common mistakes I see founders make is accepting cash investments from founders or employees who are also drawing a full or reduced salary. The idea, which is not a bad one, is that an individual would “buy in” to the company and get some “skin in the game.” The problem is that if the person is also drawing a salary all you have really accomplished is to create a tax consequence for both the company and the individual. To make matters worse, you also dilute the Pie.

One of the most common mistakes I see founders make is accepting cash investments from founders or employees who are also drawing a full or reduced salary. The idea, which is not a bad one, is that an individual would “buy in” to the company and get some “skin in the game.” The problem is that if the person is also drawing a salary all you have really accomplished is to create a tax consequence for both the company and the individual. To make matters worse, you also dilute the Pie.

Creating Unnecessary Taxes

Here’s what I mean: Let’s say you bring on a new partner with a fair market salary of $100,000 who agrees to accept a reduced salary of $12,000 per year ($1,000/month), leaving $88,000 at risk. In order to buy in to the company, he agrees to invest $12,000 cash when he joins. At the end of the first year, he would have 224,000 slices in the Pie:

Slices = (88,000 x 2) + (12,000 x 4) = 176,000 + 48,000 = 224,000 slices

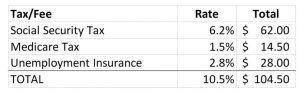

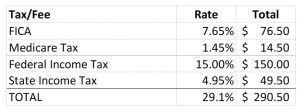

The bad news is that when the company processes the $1,000 payroll each month, they will have to pay employment taxes. These taxes will vary widely depending on your local tax laws, but here is an illustrative example:

Next, when the employee receives the money, he will have to pay his own taxes and fees:

Ouch! The payroll costs the company almost $400 per month. Seems like a waste of money. The tax people deserve their fair share too, but there is no need to pay tax when you don’t have to! Your goal is to legally minimize your taxes, I don’t know of any tax laws that require companies and individuals to maximize their tax burden. (This problem, by the way, is part of the reason there are cash and non-cash multipliers.)

Avoiding Unnecessary Employment Taxes

There are four ways to avoid paying unnecessary employment and income taxes:

Simply don’t pay the taxes. This is known as “tax evasion” and is illegal in most places. I don’t recommend this approach. Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for startups to make bad choices.

Pay the employee as a “1099” independent contractor. In the US, paying someone as an independent contractor helps companies avoid paying the usual employer-side taxes and fees. But, there are two problems with this approach. First, it simply shifts the tax burden to the employee who must now pay higher taxes to compensate for the fact that the employer paid lower or no taxes. And, second, many startup employees may not qualify for independent contractor status which means the tax people may reclassify the employee and send you a tax bill. I don’t recommend this either.

Don’t allow the employee to invest cash if they are also drawing a salary. Just say “no.” Think about it, if the person has enough cash lying around to make investments she probably shouldn’t be drawing a salary at the same time. She can simply keep her money to pay living expenses and there will be no additional taxes because the money is coming out of her savings. This strategy also lowers the number of slices in the Pie. After a year, she would have 200,000 slices as opposed to 224,000 slices thus, avoiding unnecessary dilution for other participants. In Slicing Pie terms, this prevents someone from “double-dipping” for slices. I do recommend this approach.

Lastly, if the team feels that a cash investment is necessary to show long-term commitment to the company, simply structure the investment as a loan and do not allocate any slices. This way, the company can pay back the loan without incurring taxes for the company or the employee. In this case, the $12,000 would be paid back monthly at $1,000 per month. And, like the above example (#3) this does not allow the individual to double-dip for slices.In some cases, the law may require that a reasonable interest rate be applied. In this example, the company could pay up to 10.5% and still breakeven on the alternative taxes. This would cause an income event for the employee, but income tax, instead of employment tax may apply and the burden would be much lower in any case. The benefit is that the company can use the loan to pay other short-term expenses and make future loan payments from future cash flow. If the company skips a payment, it can allocate slices instead. I sort of recommend this approach, but #3 is much easier and safer.

I’m surprised by how often start-up companies accept cash investments from founders or employees and then turns around and pays them a salary. As you can see, it simply runs the money through the company books and back out to the employee minus the taxes. It is a highly inefficient use of funds.

If the employee can’t afford to work without salary, she should not be making cash investments. She should simply forgo the salary until the company can afford to pay. And, until the company can afford to pay, the employee must be comfortable living on savings or credit cards and eating a steady diet of Ramen Noodles.

Early-stage, bootstrapped startups usually don’t pay much, if anything, in income tax because, by definition, they aren’t generating income (bootstrapping implies you haven’t reached breakeven). However, employment taxes are incurred when employees are paid regardless of income. Furthermore, using “priced” equity to pay employees could also trigger a tax consequence. Keeping [image error]clean records, filing the right forms and documenting transactions can help clear up tax issues with the tax people, but you should never evade taxes you actually owe. Financial transactions often have a way of producing unintended consequences. Slicing Pie lawyer Roger Royse has a great book that covers some of these issues.

This particular case is fairly obvious once you spot it, but many things are not. If you aren’t well-versed in accounting and basic tax rules and you can’t yet afford an accountant or attorney and can’t find someone who will work for Pie, there are a plethora of free resources about startup accounting a tax.

August 24, 2017

Slicing Pie Summaries

But, not everyone wants to read an entire book. Some people want a 10,000-foot view before diving in.

I’ve created a couple of different summary options. One is a single-page summary of the model and one is a description of the basic Slicing Pie formulas. These documents are designed to help Slicing Pie companies introduce the concept to potential employees or partners or anyone else curious about the model.

Download links will be emailed to you!

July 26, 2017

Why Fair Market Value is Fair

The fair market value of anything is the price a rational buyer would agree to pay a rational seller for it. For instance, the fair market value of a pop-up hot dog toaster is about $20. I know this because I reviewed prices from a number of online re-sellers and I consider myself a rational buyer of pop-up hot dog toasters. I’m not really in the market for one of these things, but I would advise my kids, who are in the lemonade business, that $20 might be a good investment. Hot dogs, in our local grocery market, cost about 50₵ and buns are about 25₵, The kids can provide condiments and buns for less than 20₵.

The fair market value of anything is the price a rational buyer would agree to pay a rational seller for it. For instance, the fair market value of a pop-up hot dog toaster is about $20. I know this because I reviewed prices from a number of online re-sellers and I consider myself a rational buyer of pop-up hot dog toasters. I’m not really in the market for one of these things, but I would advise my kids, who are in the lemonade business, that $20 might be a good investment. Hot dogs, in our local grocery market, cost about 50₵ and buns are about 25₵, The kids can provide condiments and buns for less than 20₵.

With total variable costs under $1, selling hot dogs for $2 to complement their lemonade could be a lucrative idea. If they sold eight dogs a day they would recoup their investment in the toaster in fewer than three days and could enjoy a profitable business asset all summer or even longer. If they stuck with the business, they could make hundreds of dollars before school starts.

If the health inspector shuts them down for touching the dogs without washing their hands, they will have to comply with health & safety laws. They can do this by hiring a staff, moving into a commercial kitchen, and paying for wages, taxes, business licenses, insurance and a plethora of other expenses. All of these things will have a price which they will pay if, and only if, they believe the investment will yield a positive return on investment.

The price they pay for everything will be the fair market price. As rational buyers, they will research the market and negotiate with sellers based on their beliefs about their projected ROI. There is no guarantee they will be able to make any money at all. There are lots of risks. It could rain all summer, for instance. Or, perhaps another kid opens a competitive stand. Or, maybe they just get bored.

Overpaying

In some cases, an unscrupulous seller may attempt to take advantage of their age and inexperience. “You’re going to make hundreds of dollars selling hot dogs, kids, so this hot dog toaster will cost $500. Without it, you can’t start your business,” they say. In other words, this seller priced the toaster on what he thinks the kids are going to do with it, not the fair market value. This is sometimes called “value-based” pricing and sometimes it’s a good approach, but not when there is a clear market for a product or service. In situations like this, the seller is essentially extorting future value from the firm by convincing the founders that they are providing access to a key ingredient without which the venture would fail.

If the kids didn’t know any better, this argument sounds logical so they will overpay. But, just because a seller can get away with something like this doesn’t mean it’s fair. As soon as the kids realize they are being ripped off they will find another seller who is happy getting the fair market price.

Underpaying

In other cases, the kids may attempt to take advantage of their clueless father and not pay me anything for my savvy business advice. “You’re our dad, so you should advise us for free because you love us,” they may argue. Sounds logical. But, just because kids can get away with something like this doesn’t mean it’s fair. It’s not uncommon for startup employees to be severely underpaid.

When dad is no longer helpful, perhaps they will engage an experienced hot dog restauranteur to consult with the operation. Like other rational buyers, they will negotiate a fair fee with the rational consultant. If the kids find comparable services elsewhere for a lower price, they will move to the most cost-effective advisor. The more unique and relevant the skillset of an advisor, the more they will pay.

Like most everything, the basic rules of supply & demand apply in the hot dog business.

If the kids make good, rationale investments and good business decisions they have the chance to create a profitable business.

Smart managers in successful businesses always do their best to pay fair market rates to acquire the inputs they need to create assets in hopes that the assets will create long-term value that greatly exceeds the cost of acquisition. In fact, long-term success often depends on a company’s willingness to pay fair market rates.

Occasionally, managers will overpay or underpay for inputs, but these events will ultimately obscure the real cost of doing business at best, and destroys the business at worst. Startups are especially vulnerable to making bad business decisions based on unfair pricing because founders often negotiate artificially low prices or use equity, instead of cash, to acquire the inputs needed to build their business assets. These seemingly harmless or even beneficial “non-cash” transactions can be disastrous.

Overpayment Problems

Founders are nothing if not optimistic, their belief in their ability to realize their vision is an important skill during the early, bootstrapping days of a company and beyond. They wind up making unsustainable commitments to contributors often in the form of equity allocations based on future values which are unknowable. In the hot dog example, the $500 machine may seem to be a logical investment, especially if they can use equity, instead of cash. In fact, the ability to use equity can be a component of the decision-making process. The founders might be so happy to find a seller willing to take equity that they disregard the price altogether. A good example of this is when a startup gives a seemingly small percentage to an advisor who does little to help the business.

Equity allocations based on future events (i.e. “you’re going to sell lots of hot dogs”) are bad ideas because they are based on unknowable events. As the company moves forward and founders become smarter about the market they will realize they overpaid and disagreements will arise. Even when one party gets away with a bad deal it does not make it fair.

Underpayment Problems

Founders are nothing if not resourceful, their ability to acquire the things they need a low or no cost is an important skill during the early, bootstrapping days of a company. They negotiate low rates with landlords or professional advice, hire employees without pay, haggle with suppliers and do whatever it takes to conserve cash. Sellers are often willing to accept underpayment in hopes that the entrepreneur will eventually be in a position to provide fair market rates. However, when founders don’t properly account for fair market rates they develop an unrealistic understanding of their cost structure that may be unsustainable and/or not scalable.

A common trap is using “low overhead” as an excuse to set prices low in an attempt to undercut a competitor. Even if the company can build early traction, the pricing may not allow the company to make a profit or even cover costs in the long term. Raising the pricing may lose customers and new customers may not value the company’s products or services enough to justify the higher price.

Underpaid sellers will eventually get tired of losing money and prefer to provide their goods and services to others at fair market rates. When this inevitably occurs, founders may not be able to pay and, therefore, run out of working capital before breakeven or other financing event.

Additionally, underpaid participants may grow to resent the founders and withdraw their support altogether leaving the fledgling business without the necessary resources.

We live in a world where market rates are knowable. There are very few resources that can’t be replaced with a quick online search. Fair market value provides a basis for making smart financial decisions. This means that a savvy buyer can shop around to make the most efficient us of the company’s money. However, if either party negotiates too aggressively, the final outcome may not be sustainable. Paying a logical fair market value helps foster stability and good decision making.

Slicing Pie relies on fair market value to ensure that participants are being properly recognized for their contribution and company buyers aren’t kidding themselves about their cost structures. If the company has cash, it can pay cash. If not, the company can allocated slices in the Pie to reflect the fact that the unpaid portion is the seller’s wager on the future success of the company. Artificially inflating or deflating costs based on estimates of unknowable, future events may provide an apparent short-term benefit, but the long-term effect can kill a company.