Mike Moyer's Blog, page 6

April 5, 2019

Three Reasons Someone Would Not Want to Use Slicing Pie

If you and your fellow founders have chosen to implement the Slicing Pie model in your bootstrapped startup company, you can rest assured that if you follow the logic you will all get a share of the equity that accurately represents the fair market value of your contributions relative to other participants. Furthermore, you and the other members of the team will enjoy the security the model provides when someone separates from the firm. No matter what transpires, Slicing Pie will self-adjust the split to keep it perfectly fair.

To some, this seems to good to be true, but it’s not. There is only one version of fairness and it’s always based on observable events rather than unknowable future predictions. So, when you add someone to your team and he or she does not want to use the Slicing Pie model, it is usually due to one of three reasons:

One: He or She Doesn’t Understand Slicing Pie

I spend a great deal of my time teaching Slicing Pie model to people all over the world through live seminars, phone calls, emails and webinars or creating educational materials including books, videos, articles, and even a Slicing Pie game. Still, sometimes it just doesn’t “click” right away. Be patient and give the person some time and space to fully understand how it works. People who agree to it without understanding it could get caught off guard. For instance, a person who gets fired for cause will lose some or all of his or her slices. It’s perfectly fair, but it may still hurt (as it should). Slicing Pie gives people what they deserve, not always what they want.

If you find someone who is struggling to understand, you can always set up a call with me here. There is a fee for the call, but I can arrange a no-fee call if you are unable to pay the fee,

Two: He or She is Not Willing to Learn Slicing Pie

Occasionally, you will encounter a person who dismisses Slicing Pie for no reason other than he or she not wanting to take the time to learn it. Often, these people cite industry “norms” like, “an advisor should get 2%,” or “it was my idea, so I want 51%.” The person might be “old school” and consider themselves “above” the model. I often hear things like, “let’s just trust each other,” or “we’ll just do what is fair.” These statements show a lack of understanding of how Slicing Pie and the assumption that it is possible to somehow “know better” and magically pick the right split. Encourage these people to take another look at the model but be willing to walk away from them if you must. Don’t compromise and give them a fixed percentage. Trust me, it’s not worth it. No matter how great they may be, someone is going to get burned.

Three: He or She Does Understand Slicing Pie, But Would Rather Not Use It

This reason is a bit more complicated and is usually a major red flag. Someone who appears to understand the model yet insists on a fixed percentage is either willing to benefit at someone else’s expense, or willing to allow someone else to benefit at his or her expense.

If someone feels he or she is in a position of power, the temptation to take advantage can be significant. If the company is desperate for cash, for instance, the provider of the cash may impose unfavorable terms. Don’t sell chunks of equity for small amounts of cash. Use loans or convertible notes. Premature valuations can cause all kinds of problems for startups and can set a bad precedent for future participants. Someone in a power position may not be aware of the damage that a bad financing deal can cause and may feel quite justified in their position. Walk away. If your company is worth investing in, you will be able to find other investors.

If the person asks for a fixed chunk of equity that appears to be less favorable than what the Slicing Pie model might allocate you have a different problem. You may be dealing with someone who does not take the project seriously or worse, the person may expect it to fail so who cares how much equity is allocated? Don’t put a person on the team who does not share your own confidence in the vision of the company. The best-case scenario is you will have to fire the person for cause which is pretty stressful and time-consuming.

Slicing Pie always works. It always creates a fair split. Do your company a favor and walk away from team members who don’t understand fairness or don’t value the benefits of being fair.

March 7, 2019

Beyond the Equity Split: Compete or Non-Compete

One of the often-overlooked features of the Slicing Pie model is the logical outcomes regarding a person’s ability to compete with the startup after a separation. Getting a fair deal for everyone is more than just splitting equity correctly.

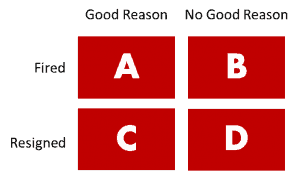

In any company, there are four basic conditions under which a person can be separated from the firm:

In any company, there are four basic conditions under which a person can be separated from the firm:

He or she can be fired for good reason

He or she can be fired for no good reason

He or she can resign for good reason

He or she can resign for no good reason

These are universal conditions, although they have different names in different places. In the UK and Europe, I often hear the terms “Good Leaver” for conditions B and C, and “Bad Leaver” for conditions A and D. I also hear fired or terminated for cause or no cause. Use whatever language works, the important thing is that different separation conditions have different logical outcomes when it comes to fairness. The outcomes should always do two things:

Reflect the fair market value of each person’s contribution. This is their “bet.” Bets are always worth what they’re worth, they don’t have special powers.

Align everyone’s interests so that each participant has incentives to act in the best interests of the business. No person should ever be given an incentive to act selfishly or greedy.

You can read what happens to a participant’s slices here, but when it comes to whether a person should be free to engage in direct competition with a former employer, it breaks down like this:

If a person is fired for good reason or resigns for no good reason, he or she should not compete with the company or solicit employees. This removes the incentive to deliberately undermine the company’s activities. For example, it wouldn’t be fair for someone to work for a startup during the proof-of-concept stage only to quit and start his or her own company once the business model is figured out.

Conversely, if a person is fired for no good reason or resigns for good reason, the company should not take any action that would hinder the person’s right to engage in competitive activity. The company can, of course, enforce patents, trademarks, copyrights and trade secrets including in-process innovations, customer lists, and other confidential information. For example, it wouldn’t be fair for someone to work for a startup during the proof-of-concept stage only to get fired once the business model is figured out and then preventing him or her from applying his or her skills and knowledge to a new company.

Enforceability

Of course, companies ask employees to sign non-compete agreements all the time and enforceability varies in different states and countries. According to Slicing Pie lawyer, Matt Rossetti: “Non-competes are a severe restriction on commerce and an individual’s ability to make a living. Because of this, the prevailing trend is to limit or bar the enforceability of non-competes.”

But legal isn’t the same thing as fair. It’s important to adhere to what is fair, even if local laws provide opportunities to act unfairly. Just because you live in a place where a non-compete isn’t enforceable doesn’t mean it’s fair to do so.

(I should note, however, that breaking the law should always be avoided.)

The Fair Logic in Action

Merrily and Anson start a lemonade stand and developed a special secret formula for making lemonade.

Scenario One: Anson slacks off on the job and, after two clear warnings, he is fired for good reason. It would not be fair for him to open a competing lemonade stand. If he wanted to be in the lemonade business, he should have corrected his behavior.

Scenario Two: Merrily decides she no longer needs Anson, so she fires him for no good reason. It would be fair for Anson to start a competing stand. If Merrily did not want this, she should have thought twice before firing him for no reason. Anson may not steal the secret formula or any other intellectual property, but he is free to come up with a new formula and go into business.

Scenario Three: Merrily decides they are going to sell kittens instead of lemonade. This is a different business, so Anson would be able to resign for good reason and, as in Scenario Two, would be free to start a lemonade stand. This probably won’t bother Merrily because she abandoned the lemonade concept, but Anson still can’t steal the secret formula. In this case, it would probably be more practical for Merrily to quit the lemonade stand, but she may want to return to selling lemonade, so she wants to retain the trade secret.

Dealing with Ideas

The next two scenarios are common sources of founder disputes because they deal with the idea upon which the company was founded.

Scenario Four (it starts getting more interesting): Let’s pretend that during the planning stage for the business Anson invented the secret formula. Merrily decides she no longer needs Anson, so she fires him for no good reason. It would be fair for Anson to start a competing stand. Anson may not use the secret formula even though it was his idea. The company owns the intellectual property (IP) he developed on the job. Anson will have to come up with a new formula to go into business.

The key legal concept here is called an assignment of rights or work made for hire. Slicing Pie logic assumes an assignment of rights. But all startups should have an assignment of rights contract or at least a clear policy in place.

Scenario Five: Let’s pretend that Anson invented the secret formula prior to starting the business with Merrily who agrees to treat the formula as a trade secret. Merrily decides she no longer needs Anson, so she fires him for no good reason. It would be fair for Anson to start a competing stand. But this does not necessarily mean Anson can extract his IP. In this case, Anson’s rights would be defined by the license agreement he has with the company. If the license agreement was exclusive, he could not use it for his new company, but he would continue to receive the fair market royalties as allocations of slices or cash. If the agreement was non-exclusive, Anson could license the IP to his new company.

Sadly, many founders with pre-existing IP don’t put an agreement in place with the new company. If you feel that you substantially own documented IP upon which a company was founded, it would behoove you to engage an attorney and do a licensing deal with the newly-formed company. This applies to trade secrets, patents, trademarks, and copyrights.

If the fair market value of time and materials were included in the Pie, it should be treated as a work made for hire and the IP would assume to be owned by the company. The owner of the IP should decide, in advance, whether developing the IP was an independent act or simply part of his or her role in the business. In most cases, a person should be able to get slices for time and materials and a royalty.

Startup companies are always changing, but Slicing Pie always delivers an objectively fair deal to participants.

Aligned Incentives

Adhering to the competition logic in Slicing Pie employees think twice before slacking off or quitting and startup managers think twice before firing someone or breaking commitments (which provides good reason to resign). People are free to make their own decisions with full knowledge of the logical consequences that will result. Any agreement that goes against this logic will provide opportunity for one party to benefit at the expense of the other—that’s not fair!

Slicing Pie lawyers can provide contracts that include the right kinds of clauses for your organizational agreements.

[image error]

December 12, 2018

Unfair Incubators and Accelerators

Incubators and accelerators often request a fixed chunk of equity from the companies who participate in their programs. The organization then provides services such as office space, supplies, access to the Internet, equipment (like printers, copiers and fax machines), mentors and educational programs. I’ve seen these percentages range from 5% to as much as 20%.

During the bootstrapping stage, any equity allocation expressed as a fixed percent is not fair. This is because the future is unknowable. It’s impossible to know, for instance, how much of the incubator or accelerator’s services you will consume and how long you will consume them? Even in situations when the curriculum is set, it’s impossible to know all the other contributions that will be made by others in order to get to breakeven or Series A investment. Remember, in Slicing Pie, equity is allocated based on the relative fair market value of each person’s contributions. So, you will never know the final number until the pie has terminated at breakeven or Series A.

However, in spite of fixed equity splits being unfair, it may be unavoidable. If you’re not willing to accept the deal, you may not get access to the program.

It is very important in these cases to be clear about the timing of the percentage. X% today is very different than X% a year from now, or the time of an IPO. Unless the time is specified, the very existence of an agreement may block future rounds of investment. Future investors may not want to allocate 10% of the company in exchange for what they perceive as a small investment of services.

The most logical timing to allocate the percentage is at the same time as the first priced round of investment, usually Series A. It’s kind of like converting a convertible note but instead of a cash amount, you’re converting a percentage.

You should avoid allocating equity earlier because you may be inadvertently setting a premature valuation for your company.

Ideally, the accelerator or incubator would recognize the value of a fair equity splits and participate in the Pie. There are two ways this could be accomplished. The first way is to simply allocate 10% of the slices in your pie at the time the deal was made. For example, if your Pie had 500,000 slices would simply add on 50,000 slices for them. This is an okay solution, but there is a better one.

The best solution is for the incubator or accelerator to simply bill the startup for the services it consumes. A monthly bill might include rent, Internet access, education, snacks, mentors or whatever else the program offers. Upon receipt of the bill, the startup can either pay it and not use any equity at all, or not pay the bill in full or in part. The unpaid portion of the bill will convert to slices alongside everybody else. This will properly reflect the program’s involvement in the company without taking an unfair fixed split.

If you are involved in accelerator or incubator that asks for fixed split, please feel free to introduce them to the Slicing Pie model or to me. I would be happy to have a conversation with the program management to help them understand how it works so they can offer a fair solution to the participants!

November 30, 2018

Different Rates for Different Tasks

It’s not uncommon for a startup founder to wear many different hats. A CTO, for instance, might code a new app and respond to customer service emails and fix bugs. These activities require different skills and some of the tasks appear to be more important. Sometimes, teams want to assign different pay rates to different tasks. Why not pay $50/hour for app coding and $20/hour for customer service? The answer is that it’s neither fair nor practical and here is why:

November 17, 2018

Slicing Pie Lawyer Recognized as Super Lawyer

Matt Rossetti, who has done hundreds of Slicing Pie consultations, was recognized as an Illinois Super Lawyer. Congratulation Matt!

September 4, 2018

Is Slicing Pie a Scam?

We’ve all heard it: “life isn’t fair.” A phrase that rarely provides any comfort at the time it is heard, its real meaning is that you won’t always get what you want. People often want what they don’t deserve, especially when they think they can get away with it.

Traditional equity splits are basically a means for people to justify getting what they don’t deserve. In fact, traditional splits are so good at getting people what they don’t deserve, many people actually believe that they deserve what they don’t deserve.

When a person doesn’t get what he deserves, it’s not fair. If the person who denied him what he deserves knows it’s not fair, it’s a scam. It’s no surprise that when a person doesn’t get what he believes he deserves he calls it a scam, even though he never deserved it in the first place.

Traditional equity split models are always unfair, yet they are so ingrained in our startup culture that people believe in them, even when faced with the logic of fairness.

Slicing Pie reflects the logic of fairness. An equity split is either fair or it’s not fair. There aren’t multiple versions of fairness, there is only one.

Slicing Pie is Fair.

Slicing Pie provides a logical framework for creating a fair equity split. Within that framework is an outline of what happens when someone leaves a company under various circumstances. In some cases, an individual would lose his or her slices and in some cases an individual would keep them.

In Slicing Pie, a person would lose their slices in the Pie if he or she was terminated for good reason or resigned for no good reason and any cash contributions would be paid back when possible. Understandably, people don’t like losing their slices and may actually believe they should keep them. Sometimes, when facing this consequence, they will assert that losing slices is somehow unfair. I’ve even heard people refer to this consequence as a “scam.” It’s not. Losing slices under these conditions is a logical outcome given the nature of the behavior.

Consider a startup with only one founder, Sam. He leaves his $50,000 job and starts a company. Over the next six months he works full time and invests $10,000 in cash. His total investment is $25,000 in unpaid salary (non-cash) and $10,000 in expenses (cash). If he were using the Slicing Pie model there would be 90,000 slices in the Pie ((25,000 x 2) + (10,000 x 4)). (But, even if he was not using Slicing Pie the outcome in this story would be the same because Slicing Pie reflects reality.)

The project isn’t as much fun as Sam thought it would be, so he quits. This is resignation for no good reason. Obviously, because he is the only participant, the startup would fail and Sam will never be paid for the time he invested and his $10,000 is gone too.

Alternatively, he may not actually quit, but instead he fritters away his time playing Fortnight. If he had a manager, he would probably get fired for this kind of behavior which is known as termination for cause. Again, the startup would most likely fail and Sam will never be paid for the time he invested and his $10,000 is gone too.

No matter how much time or effort Sam puts in or how great his initial work was, it’s all gone if he engages in behavior that ends the company. Nobody would say that it’s not fair that he lost his investment, nor was he scammed. He simply behaved in a way that lost his investment.

Furthermore, Sam’s startup may have great potential, but he still ended it. Under the right circumstances, someone else could have picked up where Sam left off, but it would still be over for Sam.

Let’s pretend Sam has a partner, Keith, who can carry on the startup. Both of them are held to the same standard—Slicing Pie. If Sam quits or stops performing, there is no reason why Keith should have to account for Sam in the future success of the company. For Sam, the game is over and for he is out of business. It wouldn’t be fair to Keith to have to carry a deadbeat partner—even if Sam’s contribution was valuable. If Sam wants to benefit from his work he should continue to do his best every day. He shouldn’t quit and he shouldn’t stop doing good work. Keith’s job is to help Sam as a member of the team, it’s not to protect Sam’s investment if Sam gives up.

Slicing Pie imposes the same logical consequences on all participants in a startup. Everyone has a choice every day. They can do their work the best they can or not. If not, they lose. It’s not personal, it’s not punishment, it’s just business!

August 23, 2018

Profit Pitfalls

One of the most common misconceptions about startups deals with the basic definition of profits:

Profits = Revenue – Expenses

Pretty straightforward—right?

But, here is the problem: many people make some fundamental mistakes about what constitutes revenue and expenses. Mistakes are understandable, not everyone has studied accounting. I, myself, have never studied electrical engineering and only have a vague understanding of the difference between an amp and a volt. Someone who does understand amps and volts could teach me the basics even though it might take much longer to teach me the nuances and implications of amps and volts.

So, while I can’t teach you about amps and volts, here are the basics of revenue and expenses:

Revenue = sales. Sales happen when people buy your product or service and either pay you or promise to pay you (in which case you’ll have to go collect the cash). Revenue does not include investment dollars or grants or loans. Your accountant can help you sort out things like how to handle non-sales income like interest received, sale of assets, etc.

Expenses = all costs associated with running the business including—and this is VERY important—everyone’s full fair market salaries. Your accountant can help you sort out things like how to handle long and short-term debt, interest payments, depreciation, etc.

Other Terms

There are a couple more really important concepts to understand:

Dividends are the portion of the profits the management team decides to pay out to shareholders. In other words, getting a share of the profits depends on whether there is a decision to actually distribute those profits to shareholders. In the rare case that a startup actually earns profits in the short term, it would be even more rare to actually make a dividend distribution. But, if the decision is made, your percent share of the dividend payout should equal your percent share of the equity. This means that managers can’t pay a dividend to some shareholders and not others (yes, there could be different classes of shares, but I’m just covering the basics. In Slicing Pie, you should have the same shares as everyone else.)

Retained Earnings are the portion of the profits the management team decides not to pay out to shareholders. In a startup, this is common because founders want to use the money in invest in growth.

Common Mistakes

The most common mistake is that people forget to include their fair market salaries as expenses. Someone will tell me, “we’re profitable! We made $40,000 last year!”

Me: “Did you pay yourself a salary?”

Him: “Um, no.”

Me: “How much is your fair market salary?”

Him: “$100,000.”

So, this guy actually lost $60,000. In the Slicing Pie model, the $60,000 is unpaid fair market compensation and would convert to slices which will all the company to later allocate equity fairly. If and when the company has enough cash to pay a full salary the Pie will stop accumulating slices.

Notice I said “enough cash,” not “enough revenue” when it comes to paying salaries. The Pie stops accumulating slices when there is cash to pay expenses even if it comes from non-revenue sources like Series A investment or large grants, for instance. If there is enough revenue to pay all expenses then you have reached breakeven. The Pie bakes after either of these situations.

Paying from Profits

Sometimes the founders tell me they are going to “pay people from profits”. If you think about it, there is no possible way this can happen because unless you are paying fair market salaries it is impossible to calculate profits, ergo impossible to pay someone from profits. People try all the time, but it does not work and, therefore, they never feel quite right about it. This is because profit distributions (known as dividends) have nothing to do with compensation. Yes, you could be like Steve Jobs and take $1 salaries, but this does not reflect logic, it’s a PR stunt.

Imagine you bought some shares in Apple, Inc. (AAPL). You own these shares and, therefore, are entitled to dividends. Apple has been paying a quarterly dividend of around $0.60 for the past few quarters. So, if you owned 21,000 shares you be paid about $50,000 per year in dividends. Of course, you would have had to pay over $4,000,000 to buy the shares (the shares are $216 right at the moment I’m writing this…which means the annual ROI for Apple is around 1.5%. Hmmm…I guess Apple investors like to speculate…don’t we all…)

Now imagine you go get a job at Apple, Inc. and you negotiate a $40,000 salary. Your manager says, “hey! You own shares in Apple, Inc. so we’ll just ‘pay you from profits’ instead of paying your salary. It’s cool, though, because you’ll probably make more than $40,000 in dividend payments.”

Not cool. Obviously, you would expect to be paid your salary in addition to the dividends paid to shareholders. The two sources of income are not substitutes. Your salary should be paid before profits are calculated and, thus, before dividends are paid.

In Slicing Pie, you share of the equity was obtained by not being paid fair market compensation. This is the “price” you pay for your shares. Once the shares are yours, you own them until you sell them.

Hand-Me-Down Shares

Here is another example to make sure this concept is perfectly clear. Pretend that I’m your dad and I get killed by a Monster Truck as I’m running through the Monster Truck rally trying to catch a balloon. It’s a mess. Blood and guts and popped balloon parts everywhere!

You and your brother inherit my highly profitable escalator shoe manufacturing company. I love you both equally so you each get 50% of the company. You did not pay for these shares, but you are each entitled to 50% of the dividends paid by the company.

I’m dead so one of you needs to step in and run the place. Your brother couldn’t care less, but you want to work there. Do you work for free? Of course not. You should be paid a logical salary for the job. Your ownership and your job are separate things. You and your brother each get a share of the profits, but you also get a salary.

If you don’t want to work while your brother sits on his butt, you don’t have to. You could hire another person to be your CEO and pay her the fair market salary and you and you brother can go sit on your butt somewhere and split the profits. Your CEO doesn’t mind as long as she is getting a fair market salary. In fact, lining your pockets is her #1 job responsibility. If she does a great job, you could pay her a bonus and/or give her a raise. If she does a bad job you can fire her and hire someone else.

So, no matter how you acquire your equity, the dividends are yours for as long as you own your shares.

Profit Shares vs. Equity Shares

It’s common for managers to want to use profit-sharing instead of equity so they can “maintain control” of their company. This is possible, but tread carefully. There is so much convoluted profit-sharing program advice about that it rivals bad equity-splitting advice. The shear tonnage of useless crap is mindboggling!

Slicing Pie uses the relative, unpaid portion of the fair market value of each person’s contribution to determine a fair split. Fair is fair (there are not multiple versions of fairness) so other models are simply not fair. So, given the logic of the Slicing Pie model the person with the highest number of slices is the person with the most to lose. That person should have at least some influence on the decisions being made! If you strip voting rights from a person’s share you create a conflict. You are saying that the people who retain voting rights are some sort of special, mystical being with greater importance that mere humans and that humans can’t be trusted to make good decisions with their own finances. Now, while it’s true that most humans suck at personal finance (including me), humans are still humans and mystical beings don’t walk among us.

That being said, it may be impractical for daily decisions to be made by a committee of Pie slicers and consolidating control to certain people may be worthwhile from an efficiency standpoint. Control can be consolidated in many ways. Most CEOs of public companies don’t own a majority of the equity, yet they make important decisions all the time. You can grant power through a variety of employment contracts, company policy or even legal structures such as a manager-managed LLC.

Decision-making powers can be part of a job description. A CEO may have the ability to approve higher expenses than a low-level employee, for example. Just be clear about people’s roles and responsibilities.

How to Create a Profit Share

If you simply must create a profit share program instead of equity, it is important that the financial benefits of the profit share unit is identical to the financial benefits of the voting shares. This can be done by creating a separate class of stock in an S-Corp or C-Corp or a special class of membership interest in an LLC. This means that profit share participants get their share of dividends and the proceeds of a sale. Any other structure unfairly values one human being over another. Yes, it happens all the time, but it’s not fair.

Warnings about Profit Shares

When you strip voting rights from an individual participant in the Pie you immediately weaken the team because incentives are no longer aligned. Remember, there are no profits until all expenses and salaries are being paid. This means:

Voting members can simply raise their salaries to absorb profits.

Voting members can approve and invite themselves corporate boondoggle in the Bahamas that burns up all the profits.

Voting members can approve the purchase of a corporate jet that eats up all the profits.

Voting members can engage in all sorts of shenanigans that will deplete company profits.

Thus, the voting members can put themselves in a position to enjoy the company profits without actually paying a dividend and there’s not much a profit share holder can do. The profit share holder can sue, but the costs of the lawsuit would use up company profits!

In public companies or in private companies with a diverse investor pool, boards of directors are formed to represent the investors when it comes to things like management compensation and decision-making powers, etc.

Forcing Profit Distributions—Not

Whether you an equity holder or a profit-share holder, dividends are never guaranteed in a startup. In most cases a startup should retain earnings to grow the company and offset the need for outside capital. You can’t force a company to make a distribution and a company can’t really make an accurate prediction of future dividend payments. The future is always unknowable, plan for the worst but hope for the best.

Taxes and Legal and Such

How you actually make payments will certainly impact your taxes. Dividends, for instance, may not be subject to certain employment taxes. I’m not an accountant or a lawyer so be sure to engage a professional that you trust who also understands Slicing Pie. No matter what, you should always operate legally and pay the taxes you legitimately owe. Nothing, however, should prevent you from fair treatment of your fellow Grunts!

The Last Point on Profits

Profits are great! Profits are important! Profits are prince! But, profits are also easy to manipulate and cannot serve as a reliable substitute for salary compensation. Profits and salaries are separate sources of income and fully understanding and appreciating why will help ensure fair dealings with the entire team.

May 8, 2018

Slicing Pie Offer Letter Template

I published a sample Slicing Pie offer letter a few years ago and it has been a very popular download. Last week I took another look at it and made some updates. The key is to make it clear that the participant is being offered a position with an agreed-upon fair market salary, but that no actual salary payments are being promised or implied and that Slicing Pie will be used for the equity split. It’s also good to cover basic expectations with regard to responsibilities, work product and time commitment. Failure of the employee to fulfill these requirements could lead to termination for cause. In many jurisdictions, an offer letter constitutes a legally-binding agreement. As I am not a lawyer, you should run this past one before using it in your own company. If you’re lawyer doesn’t understand Slicing Pie, put him or her in touch with us or find a new lawyer!

New Book in Progress: Slicing Pie À La Mode

I’ve started work on a new book, called Slicing Pie À La Mode, which will cover a number of topics related to Slicing Pie in more depth including:

I’ve started work on a new book, called Slicing Pie À La Mode, which will cover a number of topics related to Slicing Pie in more depth including:

Consulting Companies

Real Estate Deals

Bonus Programs

Incubators and Accelerators (“Nested” Pies)

Company Polices

I’d like your input with regard to other topics I should be sure to include. Your ideas are welcome!

April 5, 2018

The Four Horsemen of the Equity Apocalypse

Bad equity agreements are extremely common. The prevailing wisdom—worldwide—about how equity is split is virtually guaranteed to cause problems. I take calls and get emails literally every day from people trying to figure out a fair split within the flawed logic of conventional wisdom.

What’s really scary is that the conventional wisdom is perpetuated by smart, well-meaning, experienced people who, at their core, think they are providing good advice. The good news is that there is a founder equity split model that creates a fair split.

There are four major problems with the way most equity splits are created in early-stage, bootstrapped companies. These are the “Four Horseman of the Equity Apocalypse” because the presence of any one of them can easily doom a fledgling startup by causing disputes between founders and other participants that have nothing to do with the actual business. A tragic tale told over and over and over…

If you’re a party to an equity split with any or all of these fatal flaws brace yourself—things are going to get ugly!

Horseman Number One: Fixed Equity Splits

The most common and most dangerous of the Four Horseman is a fixed or static equity split. This is when fixed chunks of equity are doled out in percentages to founders, usually in advance of any real work being done. A chunk for the founder, a chunk for the first few employees, some little nuggets for lawyers and advisors, and a “hold-back” for future employees and investors. The most common type of split is the dreaded even split where the equity is split evenly among the founding team such as “50/50” or “25/25/25/25”.

At the core of the fixed equity split problem is the fact that it will not accommodate unforeseen changes in the team, strategy, funding or any other future events. In other words, getting a fixed equity split right requires the founders to accurately predict the future, which, of course, is impossible. So, when something inevitably changes, the team must renegotiate the split. A painful, often hostile, experience which only leads to yet another fixed split creating a downward spiral that can easily require costly and distracting legal intervention.

Horseman Number Two: Time-Based Vesting Schedules

People implement fixed equity splits with a tacit understanding that things may change even though their fingers are crossed. In an attempt to mitigate the possibility that someone will leave the company with a huge chunk of equity it is quite common to slap on a time-based vesting schedule. The usual terms are a four-year vesting with a one-year cliff. This means the individual receives restricted shares that are subject to forfeiture in the event they leave the company. Unvested shares return to the company’s authorized share pool whereas vested shares are owned by the employee. A portion of the shares (usually 1/48) vest each month except during the first year which is subject to the “cliff”. The cliff means that no shares vest during the first year, but ¼ of the shares will vest on the first anniversary. I’m not sure who came up with this. During the dot-com bubble it seemed that a five-year vesting schedule was more common, but it doesn’t really matter. Time-based vesting schedules do nothing but confuse people’s incentives.

A time-based vesting schedule implies that time is the only thing that really matters with disregard to an individual’s actual contribution during the time period. And, because the commitment levels of early-stage company participants can vary widely, this becomes a real problem. Under this agreement, the only thing that matters is that a person keeps his or her job. It provides no direct incentive to perform well. Sure, people are supposed to do a good job so that their equity will someday be valuable, but the basic terms of the deal do not reflect that sentiment. A good business deal should reward participation and performance, not just treading water until the clock runs out.

The real incentive is for a person to keep his job until the stock vests and then he is free to consider other options. It’s kind of like a mobile phone contract. Once you’re out of the contract you might stay with the same carrier, but you have no obligation. I once worked for a startup company with a five-year vesting schedule with annual vesting. People routinely quit on their fifth anniversary. It was a sad joke in the company.

To make matters worse, with time-based vesting schedules managers have an incentive to terminate employees before they vest. This, too, is quite common.

Because incentives are conflicting and time-based vesting does not reflect actual contributions, conflict often arises when employees separate from the firm. Which leads us to….

Horseman Three: Lopsided Stock Purchase Agreements

Stock purchase agreements are designed to do a number of things that aren’t all bad, but too often they are designed to protect the business and not the employees. For example, many stock purchase agreements allow the company to force a buyback of shares from a departing employee. As stated before, when an employee leaves a company their unvested shares are forfeited. Their vested shares, however, may be subject to a buyback. This means that even after you fully vest, the company can buy your shares back. The price is usually defined by the agreement and not based on current market price. So, if you receive shares with a par value of $0.01, you may be forced to sell the shares back to the company. Imagine you forgo a $100,000 annual salary for four years and fully vest. When you leave, the company buys your shares back for $10,000. Smells like a lawsuit waiting to happen and when it does, the terms of the agreement are pretty clear and employees are the losers. Remember, just because it’s legal and just because you signed it doesn’t mean it’s fair. I’ve been a victim of this before, it’s not pretty.

In an effort to protect against future problems, stock-purchase agreements are often full of terms like anti-dilution, claw-back, rights of first refusal and other terms that simply over-complicate the deal.

Unfortunately, because most stock purchase agreements are written by the company’s attorney, they usually provide protection for the company’s interests at the expense of the employee (I can’t remember if I’ve ever seen a stock-purchase agreement that doesn’t favor corporate interests at the expense of team members). Most start-ups won’t negotiate terms with individual employees on a one-off basis. These are usually take-it-or-leave-it deals that can easily lead to a destructive dispute.

Horseman Four: Premature Valuations

If founders sell X% of the company to one of their moms for $Y the implied value of the company is $Y/X%. So, if mom buys 10% of the company for $2,000 the implied value of the company is $2,000/10% = $20,000. This is a premature valuation because it was set early on in the company’s life with no grounding in reality. In most cases, a company is worth $0…until it’s not.

Premature valuations cause a number of real problems. Mom gets a fixed percentage for a fixed dollar amount. Her exposure is limited, yet the founders, who are not getting paid, have unlimited exposure. The more they work, the bigger their investment gets relative to hers, yet her percentage stays the same.

The next problem is one of dilution. Early friends & family deals are notorious for poor documentation, so when the next investor comes on board does mom dilute? If so, she might get upset, if not, the investor may walk away.

Yet another problem of premature valuation is that when new shares are issued, the IRS may decide to tax the individuals who receive them even though no cash changed hands. And, because most early-stage bootstrapped companies have a $0 valuation, the poor souls are stuck paying taxes on worthless shares.

Premature valuations lead to disputes because startup founders are not really qualified to assess an unbiased valuation for their own companies (neither are their moms).

Start-up companies should avoid setting a valuation until one of two possible events occur. The first is when the company has reached a breakeven point and can pay salaries and expenses. When this happens, a qualified professional can conduct a 409A valuation based on the revenue, assets, customer base or other observable elements of the company. Additionally, the employees and founders’ exposure is now limited to previously forgone salaries, investments and expenses.

The second possible event is during a Series A investment led by professional investors. Usually a VC or “super angel”, these are people who invest other people’s money or have obtained considerable wealth and are in the business of investing. These people will provide enough cash to cover expenses and salaries in the short to medium term (again, limiting the employee’s exposure). They negotiate the valuation and investment terms with the founding team.

Avoiding the Four Horsemen

The only way to completely avoid the Four Horsemen of the Equity Apocalypse is to use the Slicing Pie model for equity allocation and recovery. Slicing Pie is a logical alternative to illogical traditional equity splits.

You avoid the fixed equity horseman because Slicing Pie is a dynamic split model that automatically adjusts based on the relative contributions of each person. This means that no matter what changes, each person is guaranteed to have a fair percentage of the final outstanding shares at breakeven or Series A.

You avoid the time-based vesting horseman because Slicing Pie, in a C-Corp or S-Corp, becomes the basis for vesting, thus removing the arbitrary timeline. This means people’s incentives are aligned and each participant is adequately protected.

You avoid the lopsided stock purchase agreement horseman because the rules of Slicing Pie are perfectly balanced and ensure each participant is treated fairly.

Lastly, you avoid the premature valuation horseman because Slicing Pie works during the bootstrapping stage, before a valuation can be set. Allocations are based on a function of the relative contributions or “bets” placed on the company. Additionally, the Slicing Pie funding strategies, likewise, do not require a formal valuation.

Post Pie

After Slicing Pie terminates, the Four Horsemen of the Equity Apocalypse become friendly little ponies that will help, not hurt, your company. Equity splits naturally become fixed because the company will be able to provide fair market compensation and reimburse expenses to employees. Once everyone is getting paid, a bonus/option incentive program can be put in place and a time-based vesting schedule can help retain key employees. Stock-purchase agreements are replaced by option agreements or cash investors that can provide more logical terms. Finally, valuations can be set by professional investors and the stock price can be used to set the option strike price.

The Four Horseman of the Equity Apocalypse are a danger during the company’s early stage when it is still bootstrapping, the future path is unclear, participants are not compensated and the company is at its most vulnerable. It is during this critical time that conventional equity split models simply don’t make sense. Only Slicing Pie can allow your company to create a fair, conflict-free cap table and avoid apocalyptic equity disputes.