Mike Moyer's Blog, page 10

June 24, 2016

How to Fire Your Landlord with Slicing Pie

Landlords who provide office, warehouse, farmland or other facilities to startups and do not get paid rent are contributing slices to the Pie using the non-cash multiplier. So, if your company is using a space that would normally rent for $1,000 a month and you’re using the recommended non-cash multiplier of 2, then each month your landlord would be contributing 2,000 slices to your pie. But, what happens to those slices if you move out? Or, what happens if she kicks you out?

Landlords who provide office, warehouse, farmland or other facilities to startups and do not get paid rent are contributing slices to the Pie using the non-cash multiplier. So, if your company is using a space that would normally rent for $1,000 a month and you’re using the recommended non-cash multiplier of 2, then each month your landlord would be contributing 2,000 slices to your pie. But, what happens to those slices if you move out? Or, what happens if she kicks you out?

In the event of separation, Slicing Pie creates appropriate consequences for the at-fault party to discourage people from making decisions or engaging in behavior that could harm others. If a participant is at-fault, they lose their slices for non-cash contributions and slices for cash contributions would be recalculated without the multiplier (Some slices may be protected if the company opts for loyal employee protection.) The company could force a buyback at $1 per slice. If the company is at-fault the participant would keep all their slices in the Pie. The company can offer a buyback at $1 per slice.

In many cases, there will be a lease agreement in place. If the landlord violates the terms of the lease she will be deemed at-fault and would lose slices. If the company violates the terms of the lease, the company will be deemed at fault. The landlord’s slices would stay in the Pie and penalties for breaking a lease early might add more slices to the Pie.

Sometimes there is no lease in place. A spare bedroom, basement or garage might be used for the company, but the founders didn’t bother signing a lease agreement. In these cases, you can apply the termination rules in Slicing Pie.

The termination rules in Slicing Pie apply to all participants (with limited exceptions for advisors). Remember that a participant can be leave a company for four different reasons:

Fired for good reason

Resign for no good reason

Fired for no good reason

Resign for good reason

The first two reason are the fault of the person leaving and the second two reasons are the fault of the company.

Like an employee, a landlord could be fired for good reason if they commit acts of moral turpitude like stealing from the company or harassing employees, or if they failed to correct problems after two warnings.

For instance, say the electricity went off in your building and you asked for it to be fixed. This is warning one and the landlord should be given a reasonable amount of time to correct the problem. If she does not, the company should ask again, this is warning two. Again, the landlord should be given a reasonable amount of time to correct the problem. If the problem is not corrected, the company should be able to move out and the landlord’s non-cash rent slices would vanish. If she wanted to keep her slices, she should have made sure her building had power!

Conversely, if the company outgrew the space and needed to move into a bigger space they would, in effect, be firing the landlord for no good reason. After all, it’s not the landlord’s fault the company grew!

What if the company grows, but does not move out? Packing 10 people in a space designed for 2 may be a good deal for the company, but it’s not a good deal for the landlord who now has to buy more electricity and heat and toilet paper. This would be a good reason for the landlord to “resign” aka kick the company out. It’s not what the landlord signed up for and she should not be penalized.

Separating from a landlord is basically the same thing as separating from an employee. Instead of time, landlords provide facilities. But, like employees who have a responsibility to perform on the job, landlords have the responsibility to maintain a facility that provides the expected accommodations.

The termination rules in Slicing Pie aligns the interests of all participants so they behave in a way that will enhance the long-term value of the organization.

The post How to Fire Your Landlord with Slicing Pie appeared first on Slicing Pie.

June 12, 2016

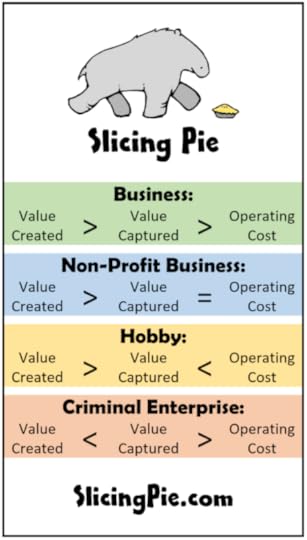

Entity Types

June 7, 2016

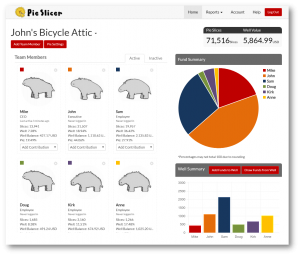

Pie Slicer Update

We are happy to announce that in the wee hours of the morning on Monday, June 7, 2016 we will be launching an updated and enhanced version of the Pie Slicer software. Since launching the program over a year ago, thousands of Grunts have logged in to track contributions to their companies and determine a perfect split in real-time.

We are happy to announce that in the wee hours of the morning on Monday, June 7, 2016 we will be launching an updated and enhanced version of the Pie Slicer software. Since launching the program over a year ago, thousands of Grunts have logged in to track contributions to their companies and determine a perfect split in real-time.

The new program has new functionality and a more robust database and back-end for a faster and more reliable service that will grow as the Slicing Pie model gains traction all over the world.

Stay tuned for more updates!

The post Pie Slicer Update appeared first on Slicing Pie.

April 22, 2016

Slicing Pie Equity Splits at Allyke

The following is the story of a real-actual entrepreneur who successfully implemented Slicing Pie to get his company started on the right foot.

In the Fall of 2014, Greg Moeller joined a tech startup in the Boston area that was developing some exciting technology. He joined the team with a handshake promise that he would receive some equity in the company based on a loosely defined system of milestones and bonuses. It was not entirely clear how it all worked, but Greg was excited about the company and worked diligently for the next few months on a strategy that he thought would accelerate the success of the company. The rest of the team rejected the strategy, much to Greg’s chagrin.

In the Fall of 2014, Greg Moeller joined a tech startup in the Boston area that was developing some exciting technology. He joined the team with a handshake promise that he would receive some equity in the company based on a loosely defined system of milestones and bonuses. It was not entirely clear how it all worked, but Greg was excited about the company and worked diligently for the next few months on a strategy that he thought would accelerate the success of the company. The rest of the team rejected the strategy, much to Greg’s chagrin.

At the urging of his marketing friend Todd, Greg decided to pursue the strategy on his own and parted on good terms with the other company. “I told Todd I didn’t want to go it alone,” said Greg, “he decided to join me and we agreed to adopt the Slicing Pie model based on a recorded lecture from Stanford University.”

Greg and Todd negotiated fair market salaries and began to use the online Pie Slicer tool to keep track of their contributions. Greg’s wife, an attorney, helped the pair set up their company using the rules in Slicing Pie. Allyke was formed to provide unique image-based search functionality to major retailers. Not long after they started, they cut a deal with a major retailer, even before the product was ready!

“The Slicing Pie model was great,” remembered Greg, “in other startups I’ve worked with the idea of valuing each person was a corrosive element that Slicing Pie eliminated, plus, it created a culture of openness and transparency that really worked well.”

Neal, a CTO, joined the team to build the product. “Negotiating fair market salaries was easy,” explained Greg, “Todd and I agreed on our own salaries and getting to a deal with Neal took about two seconds.”

Over the next few months, they implemented the program and hired some interns who agreed to take slices, instead of cash compensation.

Greg began to raise money for their company knowing that investors could be quite sensitive to the dynamics of the team. “With the Slicing Pie model in place we were well aligned, it was a non-issue for the investors,” said Greg.

In spite of the traction the team was getting, Todd decided to leave for another opportunity. Under the rules of Slicing Pie, he was resigning for no good reason and would be forfeiting some of his slices in the pie. Greg explained, “when we reviewed the rules we had kind of forgotten about that. Todd was upset, and I felt conflicted because he had built value in the company. I agreed to let him keep 40,000 slices in the pie and kept an option to buy him out for $40,000” (Note: in the Slicing Pie model this is called a “Loyal Employee Clause”)

After another four months of effort, Greg, Mark and Michael (a new team member doing sales) were able to attract angels who were experts in the retail industry and close a $1.5 million round. With the buyout in place, the angel round closed allowing Greg and the others to draw salaries. He used some of the money to buyout Todd and the interns using the Slicing Pie recovery framework. With money in the bank, the Slicing Pie model terminated and the founder’s shares became subject to the terms of the angel investor.

“The Slicing Pie formula was great! it allowed us to create a collaborative culture and adapt to changes. In hindsight, I would have made sure we were clearer about the termination rules so they wouldn’t have caught us by surprise and, at the time, we had trouble finding a lawyer that was comfortable with the model. Overall, the Slicing Pie model delivered on its promised of a perfect equity split, and I will most certainly use it again!”

Greg Moeller , Allyke

Greg Moeller , AllykeIf you would like to learn more from Greg, please complete the form below. Both Greg, and Mike Moyer will get a copy of your message. Greg will respond if he can!

The post Slicing Pie Equity Splits at Allyke appeared first on Slicing Pie.

April 14, 2016

Risk Taken vs. Value Creation

Once in a while, someone will ask me why the Slicing Pie model isn’t based on value creation instead of the fair market value of the contributions made. The concept sounds reasonable: shouldn’t a person who creates the value reap the value? However, there are a number of problems with this approach that make value creation an impractical tool for the fair allocation of equity.

Pretend a startup is a game of Blackjack. Two partners, Anson and Norvin, agree to play against the house and split the winnings 50/50. They each bet $1 on the same hand. The dealer deals two aces. The partners weren’t expecting this, but they decide to split the aces and double down. Anson is busted, so Norvin puts $2 more on the table. Now the 50/50 split doesn’t seem quite fair; Norvin bet $3 and Anson only bet $1. It would be logical to split the winnings 25/75 not 50/50. In this analogy, risk is represented by the bets, and value creation is the winnings (if any). In a startup, the winnings are the future profits or proceeds of a sale, if any.

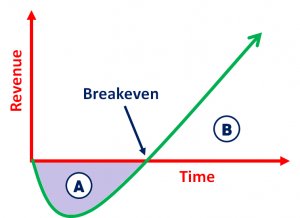

In the graph shown, the value created is represented in area B. Value comes in the form of income generated.

In the graph shown, the value created is represented in area B. Value comes in the form of income generated.

The shaded area A shows the losses incurred before breakeven. Area A represents risk taken by the individual participants necessary to realize the value created by the firm in Area B.

It’s important to remember that expenses include all costs related to the company, even those that are unpaid. For instance, many startup founders forgo salaries in the early days to conserve cash. This unpaid salary is at risk; it is a “bet” on the future outcome of the company.

In the Slicing Pie model, risk implies the unpaid portion of the fair market value of the contributions made by each participant. Risk, in this case, is a participant’s actual financial exposure, not the chance they will lose it. In other words, risk is the bet, not the odds of winning or losing. Unpaid compensation for contributions made is at-risk and can include both cash and non-cash investments.

Unlike future value, risk is quantifiable and knowable at any given time up to breakeven. In the Blackjack analogy, we can easily observe the bets made by each player, but it is impossible to predict the ultimate payout. By keeping a log of the various contributions made and who made them, the Slicing Pie formula can calculate one person’s risk relative to the others and, therefore, allocate equity fairly. At the point of breakeven, all the risk is known and a final percentage for each person can be determined. After the breakeven point, individuals are no longer incurring personal risk because they are getting paid their salaries and expenses, etc. In other words, they are no longer making out-of-pocket bets, they are, in essence, playing with the house’s money.

The principle behind Slicing Pie is that a person’s % share of the equity should be equal to that person’s % share of the risk taken. In the Blackjack game, each person’s % share of the winnings should equal that person’s % of the bets placed.

Now, let’s consider the same scenario from the standpoint of value creation. Anson and Norvin go to the Casino. They discuss, at length, which game to play. Anson wants to play Blackjack, but Norvin wants to play Craps. They finally decide to go with Blackjack. Anson argues that because it was his idea to play Blackjack, he should get a larger share of the winnings. Norvin reluctantly agrees to a 60/40 split and they each place $1 on the same hand. The dealer deals the two aces. Another discussion ensues about whether they should split the aces. Anson doesn’t want to because he is out of cash. Norvin offers to pay, but Anson insists the split should stay the same because it was his idea. Norvin thinks that his money will enable them to win more money. The dealer is getting impatient. They finally agree to a 50/50 split and Norvin bets. The dealer puts the next cards down. Anson makes the call on the left hand and loses, Norvin makes the call on the right hand and wins! Norvin is upset that he has to split the money 50/50. It was Anson’s idea to play, but Norvin thinks it was his money and strategy that created all the value. Anson is upset because he had to pay 100% interest to the loan shark that gave him the original $1 and Norvin didn’t have to take a loan. Anson thought that they should pay off his loan with the winnings. After all, thought Anson, without his $1 they wouldn’t have had enough to play, and it was his idea to play in the first place.

They each hire lawyers…

In this scenario, the duo tried to determine value creation before the value was created and, when value was actually created, they both felt entitled to a larger share. This is a common problem.

In most cases, however, it’s impossible to predict the value that will be created and, even if it were possible, it would be impossible to assign that value to individual participants. In the above example, where was the value created? Anson’s idea to play Blackjack? His loan? Norvin’s money? Norvin’s strategy? Or was it just luck? It was probably a mix of everything.

In the non-startup world everyone would just get paid. There would be no need to place personal bets because the company is playing with the house’s money or the investor’s money. In both cases, what you are getting paid should be equal to the fair market value of the contributions you make, not the future value generated from your contributions. Can you imagine having to argue how much value you created every pay period? Would you give money back if your ideas backfired?

In the non-startup world, we negotiate payments based on the market. People who have a track record of creating value have higher salaries than those who don’t. When a person is hired, it is expected that they will perform to the best of his or her abilities. People who perform better than expected get raises and bonuses and promotions. Those who perform worse than expected get fired.

Consider an individual who gets hired to pursue a marketing strategy that was designed by the management team. In the non-startup world, he would be paid his salary. In the startup world, he would not get paid and, therefore, would be betting his salary on the future. But, what if the strategy was flawed and did not work? It’s not the fault of the employee if he did his best to follow the strategy as outline. In both cases, the company might be forced to discontinue the operation and terminate the employee. It’s a bummer in either case, but does the failed strategy mean the bet the startup guy made on the startup with his unpaid salary doesn’t count?

Does the $1 Norvin bet on the losing left hand in Blackjack not count towards his total bet? Should Anson be penalized for making the wrong call?

What if the employee spots the flaw in the strategy and corrects it allowing the company to make millions? Does he get to keep the money that was made? Probably not! It belongs to the company. In the non-startup world his managers would promote him and give him a raise. In the startup world his managers would do the same, but because he placed a bet in the form of unpaid salary, he would be entitled to a future % share of the profits that properly reflected his % share of the risk taken to earn those profits.

In the Slicing Pie model compensation for all types of contributions is treated the same way it would be treated in a non-startup company. The only difference is that if the money isn’t available to pay everyone, unpaid money is at-risk and, therefore, becomes a bet on the company’s future. Once the bet is on the table, it’s part of the game.

Entrepreneurs are pre-occupied with future value, which is understandable. However, problems arise when their predictions are treated as facts. The only thing they can know for sure is the fair market value of contributions made. By looking at risk taken, rather than value created, founders can operate their companies in a more logical way and avoid arguing about which past moves created future value.

The post Risk Taken vs. Value Creation appeared first on Slicing Pie.

December 13, 2015

Slicing Pie for Jump Chile

I'm looking forward to visiting Santiago, Chile for some Slicing Pie events! Below is the flyer for the December 16th event. I hope you can make it!

October 29, 2015

Slicing Pie Legal Discussion with Matt Rossetti

Matt Rossetti is a Chicago-based Slicing Pie friendly attorney. Click here for more information about his practice and to access Slicing Pie agreement templates.

October 1, 2015

The Fair Market Value of a Relationship

Slicing Pie uses fair market value as part of the formula for determining fair equity. I often get questions on how to value a relationship. Everyone on the planet will agree that relationships are important and valuable, but putting a fair market value on the relationship seems difficult.

Relationships are only valuable if they can be translated into money. This is business, after all, and money talks. Relationships can translate into sales, investments or partnerships that provide value to the organization.

In the Slicing Pie model, I encourage people to use discretion when providing slices in the pie for relationships. Someone who merely makes an introduction, for instance, may not warrant any slices. Someone who sets up meetings and helps negotiate a deal, on the other hand, may be entitled to slices.

In some markets an introduction may be enough. Trevor Ewen, author of Pear of the Week, a personal finance and investing blog, considers it standard practice to provide fees for referrals stating that “in my day job as a software engineer, we are usually willing to pay 5% of the client’s value for a successful referral resulting in a sale.” In other markets Ewen is more conservative, “in real estate, the terms are a bit softer.” Ewen recommends setting the terms upfront, “If fees are involved, they need to be discussed up front. I think it’s a little unrealistic to make a referral and then ask for money. It’s much better to state that any referral you make is worth X, and then others decide whether or not to work with you.” In most cases, discussing the terms before the deal moves forward will help avoid disputes later on.

In many cases, people provide referrals because it’s good business and good karma. Tracy Fuller, from Innovative Events, Inc doesn’t expect to be paid for introduction and thinks it’s good for business, “I just made a warm referral that is in the process of resulting in a $75,000 investment into a company to start franchising. If I didn’t make this connection it would never have happened. This is the company’s first investor in this project. I enjoy making warm referrals and helping others close sells. I have not been paid with dollars but certainly with good faith and return referrals. Being the go-to person puts me in the place of opportunity.”

Reciprocity, rather than a fee, is a common expectation of professional referrals. Robert Palidora, a financial consultant from Pennsylvania says, “our industry survives on referrals, we are taught to ask for them. There is no compensation expected or assumed. There is the assumption for a quid pro quo relationship.

When considering the fees, check what’s customary in your market. For employees, tapping personal relationships may simply be part of the job. Some jobs, like sales, carry a moderate base salary plus a commission. Other jobs, like CTO, may not warrant a commission or fee. Their fair market salary should encapsulate the fact that they have connections in the industry.

In Slicing Pie, when a relationship turns into a sale the person who makes the sale is generally entitled to an industry-standard sales commission. When a relationship turns into an investment, the person who closes the deal and is not otherwise compensated by the company, may be entitled to a finder’s fee. When a relationship turns into a valuable partnership, the person who creates the deal may be entitled t a percentage of the savings or sales generated as a result of the partnership as long as they’re not otherwise compensated.

Fair Market Value

Slicing Pie uses fair market value as part of the formula for determining the perfect allocation of equity in a startup company. Fair market value is the price a person would have been paid by someone who could afford to pay for the same contribution, this is similar to opportunity cost. When someone contributes something of value to a starting company they are, in effect, betting the fair market value of the contribution on the future outcome of the company. It’ a risky bet, which is why Slicing Pie uses a risk multiplier to calculate the number of slices.

Everything has a fair market value…as long as there is actually a market for the product or service and the individual in possession of the product or services has the wherewithal to reach that market.

The worms in my yard may have value to someone, but I, personally, have no access to the worm market so my contribution of worms is more or less valueless. The time I spent digging them up has the fair market value of a landscaper’s rate with similar skills to my own. If, however, I am a professional worm farmer and actively deal in worms, my worms have a fair market value.

The fair market value, therefore, lies at the intersection of the product or service being offered and the market to which it is being offered. A snow shovel has little or no value in Hawaii, but great value in Minnesota.

If I’m a computer programmer in San Francisco my fair market value may be much higher than someone with the exact same skills in Bangladesh.

If I am a highly skilled commodities trader in a town with no commodities exchange my skills have little or no value. In order to create value from my skills I need to move somewhere that I can apply my skills. I need to go where there is a demand for my skills. If, however, I’m joining a startup commodities exchange my skills may be applicable. My fair market rate would be whatever a person with my skills would get paid for my skills on the open market. In the case of a commodities trader, I might get paid a moderate base salary plus a percentage of the money I make for my employer.

Most of the time fair market value is easy to observe in the market place. It’s much easier and more reliable than trying to predict the future. If you can’t observe a fair market value there may be no market for the contribution and, therefore, no fair market value.

More details on how to determine fair market value for different kinds of contributions can be found in Slicing Pie or Fair & Square.

September 25, 2015

Slicing Pie Retrofit/Forecast Guide

Many founders discover the Slicing Pie model after they have already succumbed to a dreaded fixed split. This guide outlines the process for retrofitting the Slicing Pie model using the Retrofitting/Forecast Tool spreadsheet that you can download below. Some ideas for doing this retrofit is covered in the Slicing Pie book so if you’re not familiar with the model, this may not make perfect sense.

Retrofit/ForecastGuide

Download the PDF guide that walks you through the retrofit.

Retrofit/ForecastTool