Jean Collen's Blog, page 6

September 8, 2021

FIONA COMPTON – PEN NAME FOR MY FICTIONAL WRITING.

About Fiona Compton

About Fiona ComptonIn order not to cause confusion between my non-fiction writing (published in my own name of Jean Collen) I am publishing fiction under the name of Fiona Compton. I have created a Facebook page for FIONA COMPTON – WRITER

If you are registered on Facebook, please like this page and follow it. All my novels and a collection of short stories have a musical theme. They are available at FIONA’S STORE – FICTION WITH A MUSICAL THEME

I have created a separate wordpress page for my fiction writing at: FIONA COMPTON’S FICTION

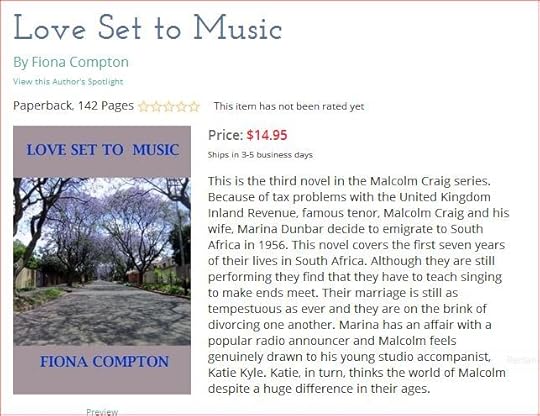

Third novel in the Malcolm Craig series

Third novel in the Malcolm Craig seriesI have completed the third novel in the Malcolm Craig series and have published the book as a paperback and as an Epub E-book. Read more about the new books and the two previous books at: Fiona’s Store – fiction with a musical theme

This is the fourth and final novel in the Malcolm Craig series. The stormy marriage of Malcolm Craig and his wife, Marina Dunbar eventually reaches the point of no return. They have to decide whether to remain married for the sake of their “sweethearts of song” image in the eyes of the public, or go their separate ways at last. In 1965 Kate Kyle, the young woman who is the object of Malcolm’s attentions, is so distressed and hurt at the course of events that she decides that the only course open to her is to leave the country and try to make a new life for herself in the United Kingdom.

Published on 27 November 2015.

Here is a random sample from “Love Set to Music”.

Kate – April 1962

After I finished my secretarial course I was working in the cables department of a city bank in Simmonds Street. I was taking lessons in piano and singing and preparing for various exams so I had to get up at the crack of dawn to practise my scales in singing and piano before I went to work. I was exhausted by the end of the day! Liz was on her April school holiday but I was working a five and a half day week in the bank with no sign of any holiday in view. My father had promised that if I did well in the exams he might allow me to leave the bank and study singing and piano full time until I completed my diplomas in both subjects so I was determined to do well no matter how exhausted I was. Becoming a professional musician was far more appealing to me than spending the rest of my life typing out letters and cables in the bank, and working overtime when the Rhodesian Sweep cables arrived and had to be decoded so that the bank could notify all the lucky winners that they had won a lot of money in the sweep.

One day Liz phoned during my lunch hour. She was very excited.

“Malcolm needs a small studio audience for his Edwardian programme tomorrow night and he’s just phoned to ask if I’d like to go. I suppose he’s been in touch with you too, Kate?” she asked.

My heart sank for he hadn’t asked me. I felt a stab of pure jealousy that my friend had been asked to go to the recording and Malcolm hadn’t bothered to ask me.

“No, he hasn’t phoned me,” I replied, barely able to speak for my mouth had dried up completely. “Perhaps he’s not planning on asking me at all.”

Liz was silent for a moment. She had probably assumed that Malcolm would invite me and she must have known that I was feeling very hurt not to have been invited.

“Well, it’s still not too late. Maybe he’ll phone you once you get home,” she said brightly, and then found an excuse to ring off quickly rather than commiserate with me any further. I continued eating the sandwiches my mother had made for my lunch, although I could hardly swallow them because there was a persistent lump in my throat. I did my best to keep a brave face and not let the tears that were welling up in my eyes run down my cheeks.

Malcolm

Marina and I were having a snack lunch in the studio. Eunice always managed to think of something interesting to put in our lunch boxes. As far as I was concerned the lunch break was the best part of our day in the studio. I really was not cut out to teach other people how to sing. I had managed to get out of most of the morning’s lessons by spending time in the office telephoning friends to invite them to the recording the following evening.

“I think I’ve contacted enough people for the recording tomorrow,” I said to Marina.”We don’t want too many in that small studio otherwise the applause will sound like Wembley Stadium at the cup final instead of a few genteel guests in a refined Edwardian drawing room. I had to laugh at Liz. She was so terribly excited about it. She could hardly contain herself!”

“Did you manage to get through to Kate?” asked Marina. “I know it’s sometimes difficult to get through to her at the bank when it’s busy.”

“Kate? I didn’t think of phoning her at all. I stopped phoning when I reached the right number.”

“But you know she and Liz are such great friends now. She’ll be terribly disappointed if you don’t ask her and she finds out that Liz is going. I wouldn’t be surprised if Liz didn’t phone her right away to tell her the exciting news. You know how they both adore you!”

I hadn’t even thought about whether Kate would be disappointed, but I realised that Marina was quite right. Kate would be very hurt indeed if I didn’t invite her to the recording. Despite her reserve, I didn’t need Marina to tell me that she thought a lot of me. She was probably as fond of me as I was of her. Why on earth hadn’t she been the first person I phoned instead of leaving her out altogether?

I looked up her number in the studio diary and made the call. I don’t think I have ever heard anyone happier to hear my voice in years.

“Will it be you and your parents, Kate, or do you want to bring your boyfriend with you too?”

I hoped she didn’t have a boyfriend, but if she did, I’d have to put a good face on it and receive the spotty youth with good grace.

“I haven’t got a boyfriend,” she replied in a small voice. For some reason I was very pleased to hear this. “It’ll just be me and my parents. Thank you so much for asking us, Mr Craig.”

There was a pause and she added, “I thought you had forgotten me.”

“Never, darling,” I lied bluffly. “Marina and I will meet you in the foyer of Broadcast House at half past seven. You won’t be late, will you?”

“No – we’ll be sure to be there on time,” Kate assured me solemnly.

Kate

We were usually pretty casually dressed when we went to rehearsals for the choir. Sometimes Liz was still wearing her blue school uniform if she hadn’t had time to change after some activity at school in the afternoon. We had never seen any of the other broadcasters formally dressed when they arrived at Broadcast House to record their programmes or read the news, although we had heard that BBC news readers had worn evening dress to read the news in the nineteen-thirties – and possibly beyond.

I was glad that Liz and I had dressed smartly for this particular trip to Broadcast House. When we arrived in the brightly lit foyer, there was Malcolm Craig clad in evening dress with a flower in his lapel, while Marina Dunbar wore a low-cut red evening dress, with a mink stole around her shoulders. Their great friend, widower Steve Baxter, a well-known broadcaster on Springbok radio, was obviously going to attend the recording too for he was also formally clad for the occasion although his usual attire for his own broadcasts was a sports jacket and open-necked shirt.

Although she was not taking part in the broadcast Marina was playing hostess to the people Malcolm had assembled for the recording. She ushered us all into the small studio where the recording was to take place and urged everyone to take their seats.

“Keep a seat for me in the front row, won’t you darlings,” she said to Liz and me.

Our parents sat together further back while Liz and I took our seats in the front row on either side of the coveted seat we were saving for Marina, or Miss Dunbar as I still called her. We were beside ourselves with excitement. Malcolm seated himself at a small table to the right of us, ready to begin the recording when he received the nod from the controllers who were seated in the enclosed glass booth at the back of the studio. He took a sip from the glass in front of him and glanced around at the audience.

Liz’s father asked in joking tones, “What’s that you’re drinking, Malcolm?”

“Water,” he replied dryly!

There was no further repartee between them after that exchange. Malcolm told us to clap politely after the items and talk in undertones to each other to create the atmosphere of a refined Edwardian drawing room. Although most of the audience applauded after the violinist and soprano had finished performing, it was only Marina who chatted to us brightly about the performers, and Liz and I did our best to respond with the necessary degree of ladylike decorum. For some reason everyone else seemed overwhelmed by the occasion and uttered not a word.

Malcolm got up from his chair in the corner and walked over to a spot directly in front of us to sing two ballads. Of course I had heard some of his recordings on the radio and I had heard his voice in the studio when he was showing me or one of the other pupils how to sing something properly. I had even heard him singing the Messiah when I was 13, but to experience him singing right in front of me was something I would never forget. Oh, Dry Those Tears and Parted – both sad Edwardian ballads, which he sang in his beautiful voice with all the feeling he could muster. I was completely mesmerised! I almost forgot that I had to chat politely with Marina and Liz after he stopped singing.

At the end of the recording everyone surged around him, congratulating him on his performance. Liz and I were the last in a long line of his admirers.

Malcolm asked us jokingly, “Well, was I all right?”

“All right? You were brilliant, Malcolm!” said Liz with all the confidence of youth.

“I’m glad you approve,” smiled Malcolm. “Perhaps you’ll come to some of the other recordings if you enjoyed this one.”

We nodded eagerly. I certainly couldn’t wait for the next time!

As we left the studio, I caught sight of Marina chatting to Steve Baxter while Malcolm was having a serious discussion with the accompanist. I thought I should say goodbye to her before we left, but I had the impression that she was not pleased that I had interrupted her intimate conversation with Steve Baxter.

“I’m so glad I was able to attend the recording,” I said. “Mr Craig was wonderful.”

“Yes, darling. We’re both very proud of him, aren’t we?” she replied in mocking tones, patting me on my arm. My face grew hot with embarrassment. and I suddenly felt deflated and childish. I realised then that I would be well advised not to offer such fulsome praise in future! Marina and Steve must have thought me very young and gauche.

After that magical evening it was difficult to settle down to sleep and it was a particularly dull thud that I had to force myself awake early in the morning to be in time to catch my regular bus with the other workers on their way to spend all day in shops and offices in the city.

Several months later, I did my music exams in piano and singing. Liz and an Afrikaans girl called Sonette du Preez, another pupil of Malcolm and Marina’s did their exams at the same time and Marina accompanied us all. Liz and I were suitably impressed by Sonette’s beautiful soprano voice when we heard her singing through the door of the the exam room. We decided that she had a much better voice than either of us and would probably do brilliantly in the exam

On Friday I went up to the studio apprehensively, wondering whether the exam results might have arrived. Malcolm answered the door and said heartily:

“I believe you sang very well on Tuesday, my gel!”

I looked at him intensely and said, “No, I was absolutely awful.”

“How do you think you did?”

“I’ve probably failed,” I replied with conviction.

He gave a little chuckle and marched back into the studio, leaving me to wait in the kitchen till Sonette finished her lesson. He called me in excitedly and handed me my card. I had obtained honours for Grade 8. I always expected the worst so I was always surprised if I did well. When I heard that Sonette with her brilliant voice had only managed 72 per cent for Grade 5, a mere pass, I felt disproportionately pleased, while congratulating her. Liz had passed Grade 6 with 72 per cent also. Marina and Malcolm seemed delighted with my results, and for most of that lesson, we drank tea and made firm plans for my diploma. Marina was wearing a black derby style hat and looked particularly striking in it. We all got on so well together that day.

I got honours for the piano exam too. My father was suitably impressed and agreed that I could stop working in the bank soon and study music on a full time basis.

Fiona Compton

The first and second books in this series, Just the Echo of a Sigh

First novel in the Malcolm Craig series

First novel in the Malcolm Craig seriesThe second novel in the series is Faint Harmony

Second novel in the Malcolm Craig series.

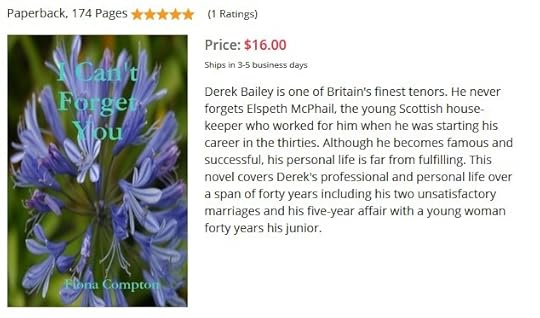

Second novel in the Malcolm Craig series.Other fiction books by Fiona Compton are: I Can’t Forget You:

Fiona Compton’s first novel.

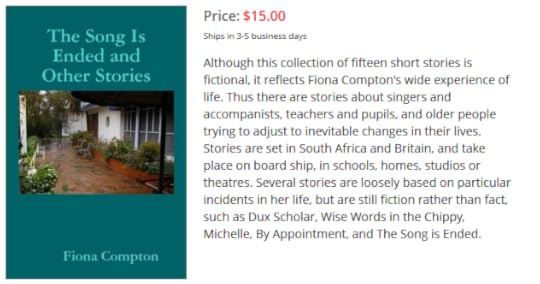

Fiona Compton’s first novel.The Song is Ended and other stories:

Short stories with a musical theme

Short stories with a musical themeFiona Compton©

26 August 2015.

Updated 8 September 2021.

ON WINGS OF SONG – A short story By FIONA COMPTON

Sally Roos waited restlessly in the line of contestants auditioning for the pop singing competition. Only ten more to go and then it would be her turn. Nobody had made it to the next round for quite a while. She watched the live broadcast of proceedings in the audition room on the giant TV screen: the judges were not at all forthcoming, sometimes even downright rude, making no allowances for the nerves of the contestants. Many were told bluntly, ‘You can’t sing. Promise me you’ll never sing again.’

Sally could see that in many cases they were right, but it was mean to deflate people’s egos so completely. Singing is such an integral part of a person, and it takes courage to sing in public, only to be callously ridiculed. Each failed contestants did a doleful walk of shame, trailing past the waiting hopefuls to the exit door. Many were tearful at having their dreams and self-confidence shattered so abruptly; others were angry and voluble, promising to show everyone that they could still be stars regardless of the flash opinions of the four powers-that-be. But most of the rejects were simply numb from their ordeal, longing for the comfort of home where they could pretend the lowering experience was a nightmare that had never happened. After the excitement of preparing for the competition, the only thing they had to look forward to was that their failed audition would be repeated over and over on TV, reinforcing the debilitating experience in their own mind and the collective mind of the nation.

Worse still, for those still waiting, were the whoops of delight from the few who were given the nod to the following round. Everyone cheered the victors with seemingly unselfish delight, although each one knew that another person through meant there was one less place for them.

Despite the disastrous audition process, most of the crowd were still full of hope. Sally was amazed at the confidence of some of the contestants, who thought nothing of singing in front of everyone at the top of their voices. She wondered whether being a complete extrovert was a prerequisite to becoming a pop star. Some could sing, but many others, equally confident, should never have been there in the first place.

Sally was wearing jeans and an emerald green top to match her eyes and complement her auburn hair and translucent skin but she realised that her mode of dress was conservative in comparison with the girls with pink hair, bare midriffs, low necklines and tight jeans or micro mini-skirts.

Sally had been studying piano since she was small, and classical singing for the last three years. Although Sally loved classical singing and had a pleasing soprano voice, she enjoyed pop music and could party with the best of them. She was doing music for matric, and only three weeks ago she had sung the final ABRSM singing exam. Her teacher, Barbara Boucher had been pleased with her performance and thought she would do well. But her schoolmates egged her on to sing the pop songs of the day. She knew she could do passable imitations of Celine Dion, Mariah Carey, Cher or Britney Spears, in voices quite distant from her own natural soprano. They all thought she was great and encouraged her to enter the pop competition.

She had decided to sing Gershwin’s ‘Summertime’, which had certainly been a popular song in its day, and Charlotte Church had sung it in the film she had made recently. It had jazzy rhythms and she could use her own voice rather than do an imitation of a pop star.

On one side of her was a confident girl with synthetic red hair, dangly earrings, and full stage make-up, her skimpy sequined top and a pink mini skirt barely covering her neat behind. Her shapely legs were clad in fishnet tights and she was frozen on this cold morning. But her spirits were warm and hopeful.

‘I’m ready for this,’ Lauren told Sally, as she rubbed her cold hands together. ‘It’s been my dream since I was a little girl to be a pop diva. I was born to be the new pop idol of South Africa. After that I’ll take on the world.’

Sally was impressed at her new pal’s supreme confidence. She wished she felt as positive about her own pop singing ability, but she knew she was a bit of a sham. How could a classical singer expect to become a pop star overnight? She wasn’t even sure she wanted to be one. She was certainly not as hungry for such a title as she was meant to be.

The boy on her other side was wearing a bright orange woolly hat. Unlike Lauren, he was nervous and twitchy. Periodically he had been up and down to visit the gents, which was no wonder, as apart from his nerves playing havoc with his bladder, he was drinking copious amounts of water from a large bottle.

‘My mouth is so dry,’ Sizwe told her. I’ll never be able to sing properly when I get in there. The judges don’t seem to know what they want. I’ve only just started with a voice trainer. She says I just have to get my voice more mature, and then there’ll be no stopping me. But I’ve only had lessons for three months. Maybe I’m not ready for this. Who’s your voice trainer?’

Voice trainer reminded Sally of a dog trainer. She had a singing teacher, which she presumed was the same thing as a voice trainer, just in different parlance.

Suddenly it was her turn. Lauren had shrieked her way through a Whitney Houston hit with the appropriate accent and ornamentation. She had been suitably berated for imitating her idol and emerged deflated from the audition room, leaving without a word.

Sally wondered what she herself was doing here. At least at the classical music exam she had been well prepared and confident that the examiner, a music professor from the Royal Academy, worked according to the rigorous standards set by the examining board. He had been polite and had not made her aware of his feelings – approving or disapproving – of her singing. The examiner would have written his report with due care. Whatever she achieved in that exam would be her true worth as a singer and musician.

This competition was simply entertainment for a TV audience of couch potatoes, slopping on their sofas, swilling beer, smoking fags, and munching chips and chocolates. A singing competition made a change from Rugby, ‘Big Brother’ or ‘The Weakest Link’. The potatoes could mock the bad singers and laugh at the antics of the cocky know-it-all judges, who were playing up to the cameras by being rude and dismissive to contestants. Even at a cut throat theatrical audition, the director was never rude to those auditioning.

It was too late to leave. She had been called to say a few words to the energetic presenter before her ordeal. Now she was going into this audition room where fairness and politeness were not to be expected from those in authority. Some good singers had been rejected, while poor ones had gone through to the next round. Sally did not rate her chances highly.

‘Just enjoy yourself,’ said the hearty presenter. ‘Show them what you can do, girl!’

Sally walked into the vast audition room, feeling cold, and nervous despite herself. After the preliminaries, she launched into ‘Summertime’. She had more or less found the right key for her unaccompanied performance. Eventually she was aware of a peremptory hand waving to her to stop in the middle of a phrase.

‘You have a good voice,’ admitted the female judge grudgingly. ‘You can sing.’

She was relieved to hear that much.

‘But you’re too operatic,’ said the next one. ‘And that’s not a pop song. Maybe you could make it in musicals, but not pop.’

‘You sing too high,’ said the third judge. ‘You’re not a pop singer. You should stick to opera.’

‘It’s a ‘no’,’ growled the chief judge, yawning and bored.

Sally felt quite dispirited to be turned down so uniformly. At least they hadn’t told her to stop singing under any circumstances. In her case, the judges were right. She wasn’t a pop singer. She didn’t long to be the second Madonna. She had only entered the competition because her mates had persuaded her to do so. Classical singing was far more satisfying and challenging, and what she had been trained to do. She would stick to it in future.

As she gathered up her belongings, she could see Sizwe on the TV screen, adopting a pseudo-confident stance to face the judges, still clutching his water bottle. She wondered what he would do with it while he was singing. Perhaps he would pretend it was a microphone, or the object of his serenade.

They wasted no time with him. He managed to stumble through a few lines of his song. She could hear the judges’ belligerent voices following her as she did the walk of shame.

‘Why are you wasting our time?’ the cocky young judge asked indignantly. ‘You can’t believe you can sing?’

‘And why do you sing in that false accent when you’re a home boy from Soweto, Bru?’ asked another.

‘Don’t even sing in the shower,’ said the third.

‘It’s a no,’ the other mumbled, making no attempt to hide his giggles at the boy’s egregious performance.

Sally was glad she didn’t have to see the crushed expression on Sizwe’s face when he emerged from the audition room. Her boyfriend, Pierre, squeezed her hand sympathetically and led her to his waiting car.

‘The judges don’t know what they’re talking about, Sally. You were the best singer there!’

‘But not a pop singer. They’re right about that.’

One look at her pale tired face told her parents that she hadn’t made it through to the next round. Her mother made everyone a strong cup of tea and brought out her special homemade ginger bread, still warm from the oven. No doubt, she had made it as a treat to celebrate if Sally had gone through to the second round. Now it was comfort food, complete with melting butter.

‘The results from the Board arrived,’ said Mrs Roos casually. ‘Can you face them after that awful audition? I’ll save them till tomorrow if you like.’

‘No, Mum. Where’s the envelope?’

Some colour reappeared in Sally’s face. If she was a flop as a pop singer, perhaps she had fared better in the classical singing exam. She opened the envelope and glanced through the examiner’s report, looking for the all-important mark.

‘It’s Honours!’ she cried. ‘I’ve never had such a high mark for an exam before. At least I’ve managed to do something right.’

Enclosed with the results was a letter asking her to sing at a gala concert for high scorers. There was even a chance she might qualify for a scholarship to one of the British music academies as a result of her high marks.

Pop singing was forgotten as she phoned her singing teacher excitedly to tell her the good news. They planned some extra lessons to prepare for the forthcoming Concert at the Linder Auditorium, where there would be no electronic instruments, no microphones or screaming teenagers in sight, just the grand piano, the accompanist, the singer and a quiet appreciative audience.

Sally would not forget this harrowing day in a hurry. Her musical journey might lead her along a different path to the one followed by pop singers. She might not be destined to be a pop idol, but singing would still play a large part in her life. She could not wait to begin.

Fiona Compton. 8 September 2021.

September 7, 2021

FIONA COMPTON -LINKS.

Protected: 1963 – 1966 Private

This post is password protected. You must visit the website and enter the password to continue reading.

LEAVING

lulu.com/spotlight/duettists

lulu.com/spotlight/duettistsLEAVING

At the end of January 1965, I started teaching music at Kingsmead College, a private girls’ school in Melrose, Johannesburg. Some of the schoolgirls were only three years younger than me, but at twenty-one I felt quite worldly wise. I settled down to teaching piano students in my music room at Kingsmead House, and music appreciation and matric music in a rondavel called Etunzi at the top of the sloping lawn overlooking the swimming pool. The classes were small; the girls well-behaved. Everything at Kingsmead was very pleasant indeed.

I still went to singing lessons and had the studio on a Wednesday to teach my private students and to work for my LTCL paper work in the piano.

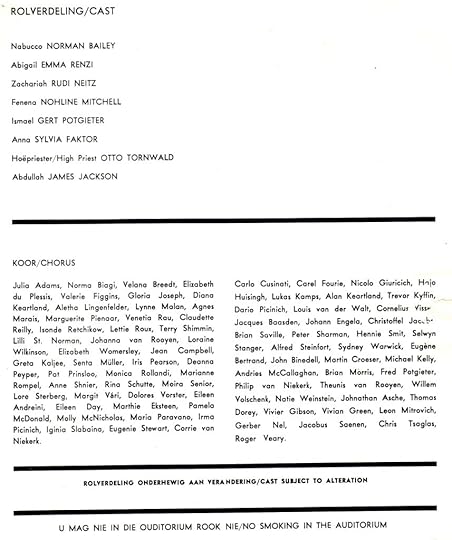

Nabucco chorus Rehearsal in the Queen’s Hall.

Nabucco chorus Rehearsal in the Queen’s Hall.

Singing in Nabucco was a wonderful experience. The conductor Leo Quayle had recently returned to South Africa after a time as conductor of the Welsh National Opera. He had dreams of building a similar company in South Africa by nurturing young home-grown singers so that they were capable of taking principal roles. If this could be done it would no longer be necessary to import big names from abroad and South African singers would not have to leave the country because there was not enough quality work for them.

Nabucco is a great chorus opera and Leo Quayle came to rehearsals occasionally to hear us rehearsing with our excellent chorus master Eberhard Künkel. Professor Quayle said that we should always remember that we were the finest singing talent in the province.

Webster as the British ambassador in “King Hendrik”.

Webster as the British ambassador in “King Hendrik”.Webster was on the film set of King Hendrik, playing the minute part of the British ambassador on the Johannesburg opening night of Nabucco. Anne attended the performance with Dudley Holmes’ mother and Dudley’s old friend, Grace Christison. Dudley was giving me a lift back to the staff residence at Kingsmead from the show that evening. As we were leaving I heard Grace ask, “Are we going straight to Anne’s?”

I was dropped outside the staff residence at Kingsmead, while the others went on to spend the rest of the evening with Anne.

At my lesson the following day I still felt hurt at being excluded. To my horror I found myself having an argument with Anne over some silly triviality. Webster looked on in alarm but did not take sides in the affray.

After this upset, I had to go back to school on the Rosebank bus to supervise the junior boarders’ evening prep. It was all I could do not to cry in front of the girls, but although I controlled myself during the prep, I spent the rest of the night in tears. Next day I sent a bouquet of flowers and a note of apology to Anne. The argument had not been entirely my fault, but I knew that if I didn’t apologise Anne might use it as an excuse to get rid of me and I could not bear the thought of never seeing them again.

Before I left for the theatre that afternoon, Anne phoned to thank me for the flowers. She said she had not mentioned our argument to anyone and that we should forget all about it.

“We three will always be friends,” she assured me.

After Nabucco ended my spirits were at low ebb. My particular friend at Kingsmead, the domestic science teacher, Joan Wishart, became engaged. Quite a few of my school friends were engaged; some were even married with children. I decided to go to the UK; it seemed the only thing to do. After my argument with Anne I realised how easily everything could fall apart.

I had been living in the sheltered and fairy tale world of the studio and Anne and Webster for nearly five years. Although I was teaching music, singing at concerts, and taking parts in shows, even mixing with people of my own age, Anne and Webster remained the most important and influential people in my life. I cared deeply for both of them, but I realised that I could not depend on them for my happiness for the rest of my life.

They had been asked to go on another tour with the SABC orchestra. After the tour Anne was going to Bloemfontein to produce The Merry Widow. Webster phoned to wish me a happy birthday before going on the orchestral trip. They would be away for two months so I would have a premature taste of life without them.

While they were away, Robin Paterson, one of the mathematics teachers at Kingsmead, whose husband was headmaster at St John’s Preparatory school, asked me to sing in a madrigal group under the leadership of Jimmy Gordon, the director of music at St John’s College, who had recently arrived in the country from Kenya. He had been a chorister of the Chapel Royal, King’s scholar at Cambridge, and had taught music at Eton College before moving to Kenya. He was a brilliant musician with a pleasing tenor voice. I was no soprano, but I sang soprano with Robin in this choir. There were ten of us, and every week we went to the College to rehearse the various Fauré, Bairstow and Byrd songs for the concert. Bob Barsby, another music master at St John’s, sang alto and played the organ brilliantly at the concert in St John’s Chapel. It was a great success, and Jimmy decided to work on the Fauré Requiem the following term.

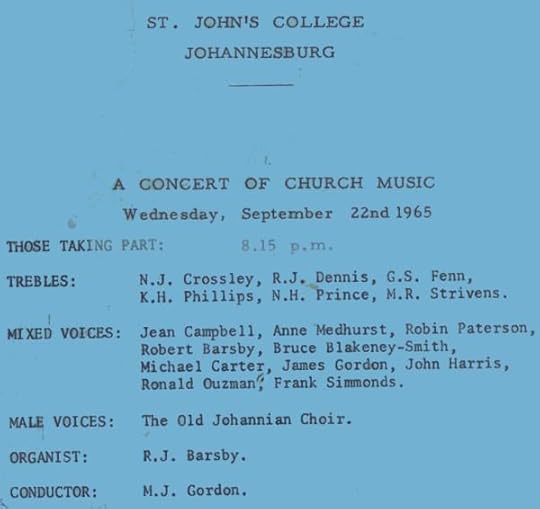

The concert at St John’s College. September 1965.

The concert at St John’s College. September 1965.In the meantime, I was still teaching at the studio every Wednesday. One day I went into town, thinking I might go up to the studio to practise, as Anne and Webster were not due back for another few weeks.

The sign Anne had put on the door when they left on the trip was no longer there and I could hear a student singing inside the studio. I could not understand why they had not let me know they were back early so that I too could resume my lessons. I went home without opening the studio door, once again feeling hurt and confused.

The first thing I did when I arrived home was to phone the studio to hear Webster’s voice with his usual gruff, “Hello”. I put down the receiver without speaking.

I assumed that they were both back and didn’t want me there for some reason. The next few days passed miserably. I didn’t go near the studio, but the following Wednesday I had to teach my private students there. About 11.00 am the phone rang. It was Webster to tell me he was back. I replied rather dryly that I already knew that.

“So it was you who phoned on Friday, Jeannie. I thought so. Why didn’t you stay on the line and speak to me?”

I told him that I had been too taken aback to say anything. He said that Anne was still in Bloemfontein doing The Merry Widow, so she had decided that I should wait until she returned before I could resume my lessons. But he wanted to see me. Could he pick me up from school on Friday?

After my few days of misery, I felt reassured after my conversation with him. On Friday I waited at the bus stop on Oxford Road, watching Tyrwhitt Avenue for his car to drive down to Oxford Road. They had sold the Ford Anglia and the Hillman Minx convertible, and bought a blue and white Super Minx (TJ9051) to replace them.

We had tea together and talked for ages – the first time we had been alone together in nearly a year. He told me about his son Keith, who now had a baby daughter Jane and was struggling to get his flower farm established. He was desperately sorry he had not been in a position to help him financially. He spoke of his brothers: Edgar had followed their father’s trade as a hairdresser and had retired to Weston-Super-Mare recently. Norman Booth, his eldest brother, an accountant, had been in the navy during the First World War. Norman had retired to Rugby and never went near the sea now that he was retired. Webster’s three sisters had spoilt him as the youngest child of the family, and whenever he was doing a show in Birmingham, the entire family expected him to host a big party for them at the Midland Hotel.

When Anne returned from producing The Merry Widow in Bloemfontein I resumed my singing lessons. She made no mention of Webster being at home on his own and I did not tell her that I had seen him.

One day I arrived to find Anne by herself in the studio. She did not refer to Webster’s absence, but as soon as I arrived home, I phoned him. Hilda had gone on another trip to St Helena. Once again they were alternating the days in the studio, but this time he had nobody to play for him.

During the time Hilda was away, he fetched me from school if he was going to the studio on his own. On one of our journeys he told me he had been a very serious young man and had his first heartbreak when a beloved girlfriend suddenly married a man many years older than herself. His mother told him that he shouldn’t be heart broken, as there were “lots of good fish in the sea”.

After that, he had become a bit of a lady-killer, determined that no woman would ever get the chance to hurt him again. When he was in Concert Party everyone in the company knew that when he went on to sing he’d look out for the prettiest girl in the hall and sing to her alone. Nine times out of ten, the same girl would appear at the stage door to see him after the show.

The term ended and some of the girls gave me farewell presents. Joan Wishart married her fiancé Alan, and made a beautiful bride. The time was drawing in; I would soon be leaving the country.

Anne and Webster did not have a happy Christmas. Webster had received an airmail letter from one of his sisters, who casually mentioned – almost as an afterthought – on the back of the letter that his brother, Edgar had passed away suddenly, without explaining how or why. He was extremely upset about Edgar’s death. On top of that the distinguished critic of The Star, Oliver Walker, whom Webster admired for his astute criticism of theatre and music, had also died suddenly on the golf course. When he spoke to Keith in a long distance Christmas call, Keith’s mother-in-law had also died, so with all the deaths, and the strain of having to cook Christmas dinner all by himself, without Hilda in attendance, it was a miserable start to 1966.

Kenneth McKellar

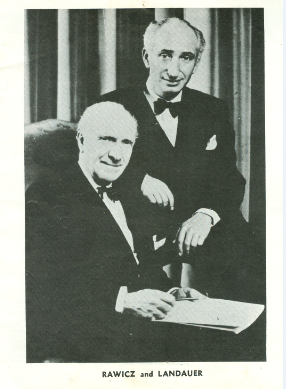

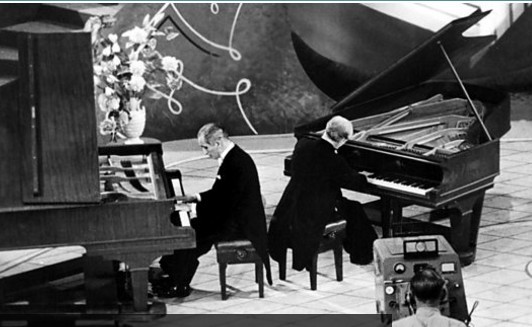

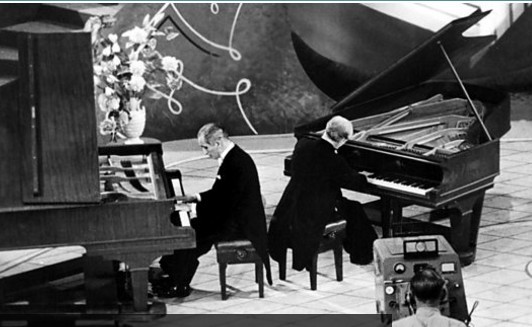

Kenneth McKellar The “Boys” – Rawicz and Landauer.

The “Boys” – Rawicz and Landauer.They went to the Kenneth McKellar Show. Kenneth McKellar found out that he was in the audience through the “boys” – Maryon Rawicz and Walter Landauer – who were on the same bill. Kenneth told the audience that Webster and Anne were in the audience, and sang Macushla as a tribute to Webster. After the show they went with Rawicz and Landauer and Kenneth McKellar to the Balalaika night club till 3.00 am. The following day Webster had felt much the worse for wear after his late night, so Anne cancelled all the students for that day.

One morning we took the dogs, Lemmy (Lemon) and Silva (Squillie) in the car to Zoo Lake, with Lemmy sitting on my lap on the journey. We had a pleasant walk round the lake with the dogs. Webster said that if any of the bowlers at his club noticed us, they would be asking what he was doing out with a dark haired young woman. It was all so pleasant and companionable.

Anne gave me a farewell gift of a container with little pouches for tissues and make-up, and we parted seemingly as friends.

She said, “You must keep in touch with us, darling. Let us know how you’re getting on.”

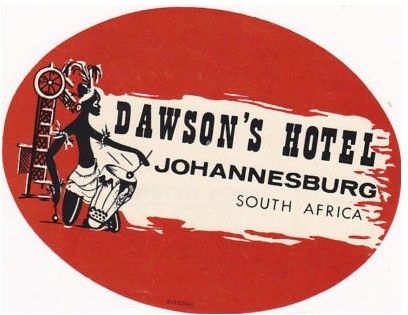

On 24 January I went into the studio to say goodbye to Webster He had given me a pretty mother of pearl powder compact as a farewell gift, which I still use today. We recalled our lunch in Dawson’s, and how young and unsophisticated I had been when he took me there, although it was only a few years before.

At last it was time to go. I powdered my face violently with his nice compact and tried hard to be cheerful although I felt as though my heart was going to burst. He kissed me and said in as matter-of-fact voice as possible, ‘Well, darling, all the best.”

I tried to smile, but I couldn’t say a word. Despite my resolve, I wept. He said, “You’ve been such a good girl up till now. Please, darling, don’t cry, for my sake?”

Eventually I pulled myself together and he said, “Good girl. I didn’t think you were going to cry, and I don’t want you to.”

I managed to say, “Anyway, we’ll meet again, won’t we?” and he said, “Of course we will.” And we did.

Webster and me.

Webster and me.Jean Collen, 7 September 2021.

September 3, 2021

THE OLD HOUSE – A Jo’burg Story pot-pourri – by Fiona Compton.

“It’s the big move on Saturday,” said my friend, Helen. “I can’t wait for it to be over.”

“Can I help at all?”

I knew I had to ask although I prayed her answer would be no. Helen is a good friend just surfacing from the morass of her divorce from Charlie. Hence the move from her elegant home, now occupied by his mistress, the soon-to-be Mrs Bryant, Mark 2.

“A red face brick bungalow with a tin roof,” Helen had told me without enthusiasm when she first bought the bungalow. It was all she could afford with the money she had been granted in the divorce settlement.

“Would you really help me?” asked Helen hopefully. “It would be a godsend if you could be at the house to receive the furniture until I get from one place to the other. I’d be quick. You’d only need to be there for an hour – or two at the most.”

“Give me the address and I’ll be there. No problem,” I said, dispensing regretfully with my slothful Saturday plans.

Helen was already fishing around in her copious handbag.

“Twenty-one,” she said, handing a set of keys to me. “Twenty-one, Juniper Street.”

It was a very hot day, but a shiver passed through my body.

“Are you sure of the number?” I asked faintly.

“Yes. Look, the address is on this label attached to the keys in case you forget it. Are you all right, Meg? You’ve gone quite pale. You should forget all that dieting nonsense. It doesn’t do you any good at all.”

“I’ll be fine,” I said, taking the keys from her with a trembling hand. “I’ll see you on Saturday at Juniper Street.”

I drove off abruptly, wondering why I hadn’t blurted out the reason for my discomfiture. Forty years ago, I had been nineteen, still living at home with my elderly parents. 21, Juniper Street had been our address.

I arrived at the bungalow an hour before the removal van was due. I had passed the house now and again on trips to the shopping centre on the other side of the hill. The thick bougainvillea creeper with heliotrope blossoms still enclosed the stoep where we had sat on hot evenings. As I climbed the familiar steps to the stoep, I felt as though I was a young teenager again, arriving home from school to receive a rapturous welcome from Shandy, our little brown and white dog of indeterminate breed.

I was surprised to see that the same wallpaper my parents had plastered on the walls in 1963 was still in the hallway. I could almost smell the goo that pervaded the atmosphere when we were having the place redecorated. I remembered my mother discussing the wallpaper with my singing teacher and the difficulty they were having in finding wallpaper they liked for decorating their new home.

“If you manage to do that job yourself you’ll be a better man than I am, Gungadin!” he had laughed.

I had been curious enough to check the origin of the dated expression and traced it back to Rudyard Kipling.

The telephone, where I had sat for hours, chatting to my best friend, Sally in the days when it cost a tickey to make a call and talk for as long for as we liked, was in the same place in the passage, although it had been replaced by a more up-to-date model than our sombre black set from all those years ago.

Sally and I studied singing with Marina Baxter and Derek Bailey, the famous English singers who had moved to South Africa from the UK in the mid-fifties. We had both been successful in our auditions to join the SABC choir and, at Marina and Derek’s suggestion, had sought each other out at rehearsals. Sally, like me, was originally from Glasgow. We both loved singing, hoped to make careers in music, and we both thought the world of Marina and Derek. Sally, a soprano, was short and plump with piercing blue eyes and honey-coloured hair. She was the youngest of three attractive sisters and was far more outgoing than me. I, a contralto, the only child of elderly parents, was tall and dark and fairly reserved and reticent until I got to know people well enough to relax with them.

The house was completely empty today as it waited for the arrival of Helen’s furniture, but suddenly the phone rang: not the computerised sound of today’s telephones, which, in my advancing years, I cannot always hear clearly. This ring was loud and jangling. No difficulty in hearing the ring, but did I have the right to answer the phone? I hesitated, but the ringing continued. Perhaps it was Helen calling about the movers. Eventually I picked up the receiver.

“Hello,” I said tentatively.

“Is that you, Meg? You sound strange this morning. Did you have a late night?”

It wasn’t Helen after all but the voice was certainly very familiar. It was the voice of a young girl. Usually girls of that age call me Mrs Johnson and ask to speak to one or other of my teenage children.

“Yes, this is Meg. Who’s speaking?” I asked rather suspiciously.

“You’re joking with me,” the girl laughed. “I just wanted to know how your accompanying in the studio went this week. Did you pluck up courage to ask him to dinner? Is he going to come?”

Suddenly I felt cold and shivery. At last I knew who was speaking. I recognised the voice of my best friend, Sally, who had died at the age of nineteen, forty years ago. I was rooted to the spot unable to speak. My younger self took over the conversation, while I, the middle-aged woman, looked on helplessly wondering what was happening to me in our old house.

“What did you sing at your lesson today?” I heard myself asking Sally, looking forward to a long chat about our heroes.

“I cancelled my lesson. I was far too excited to go. Can you keep a secret, Meg? Mum told me not to breathe a word, but I have to tell someone. You won’t believe what has happened to us!”

I waited expectantly. We never cancelled our singing lessons if we could possibly avoid doing so. We’d have to be on the point of going to hospital before we would think of staying away.

“We had a telegram this morning,” Sally said solemnly.

“Oh, I’m sorry. Has someone died?” I asked.

All the telegrams we ever received in our family had born bad news of one kind or another.

“Not that kind of telegram, silly. One from the bank to say we’ve – or rather – Mum has won a prize in the Rhodesian Sweep. Not first prize, you understand, but a fortune all the same.”

She paused tantalisingly.

“How much?” I asked.

“Forty thousand pounds!”

That was a lot of money in 1963. You could retire on the interest of money like that in days when the average wage was about £100 a month. Sally’s father didn’t retire, but he and her mother bought a bigger car, went on a first class trip back to Scotland, and had a kidney-shaped swimming pool built in the back garden.

After we got over the excitement of her parents having riches beyond our imagination, our conversation reverted to how I got on as a very keen, but inexperienced studio accompanist to Derek Bailey.

“Sally, it was wonderful, the best time I’ve had in my whole life. I’ll never forget it as long as I live. He was so kind and understanding. My sight-reading has improved so much, and guess what? He was thrilled when I asked him to dinner and he’s going to take me to Dawson’s Hotel for lunch sometime next week as well.”

Label for Dawson’s Hotel.

Label for Dawson’s Hotel.I was waiting eagerly waiting to hear what she thought of my news, which probably was quite tame in comparison to hers, but the line was dead. She was gone and I had no idea how to get her back again.

I looked into the empty lounge, still with its Adam ceiling and bay lead-light window. Even the fireplace remained although it was fitted with an anthracite heater now. In our day we had an open coal fire which filled the house with comforting warmth we never enjoy in winter today. Periodically the McPhail’s coal truck would arrive to replenish our coal cellar. ‘Mac won’t Phail you,’ read the slogan on the truck.

Our big radio with its green cat’s eye to fine-tune the stations had stood on a table next to the fireplace and was the sole source of our entertainment. The Nationalist government had banned TV from South Africa until 1976, fearing that the population might be unduly influenced by radical ideas from the outside world. The piano was in the opposite corner, where I must have distracted the neighbours practising singing and piano scales early each morning.

As I stared round the room remembering the way it had been, bemused by the vivid conversation I had just had with dear Sally, who had died so many years ago, I suddenly saw my parents and Derek, chatting together over an after-dinner whisky. I was there watching my younger self, clad in that bottle green velvet dress I had thought so attractive. It was the first time I had accompanied for Derek in their singing studio on the eighth floor of a building in the centre of the city, while Marina was away on a holiday trip. He was on his own at home, so my mother had suggested he should come to dinner one evening.

He loved our little dog, Shandy, and encouraged her to sit on his lap, shedding her hair on his smart Saville Row suit.

“My girl friend,” he said contentedly, sipping the whisky, stroking Shandy, and regaling us with tales of their days in variety when they had appeared on the same bill with the likes of Max Miller. Rawicz and Landauer and Albert Sandler.

Marion Rawicz and Walter Landauer (pianists)

Marion Rawicz and Walter Landauer (pianists) Albert Sandler (violinist)

Albert Sandler (violinist)The scene faded as quickly as it had begun and, now I saw myself standing on the bougainvillea-covered stoep with my parents bidding him goodbye after our wonderful evening together.

“Thank you for looking after Meg,” said my mother.

He smiled at me in a kindly fashion. “I think it’s Meg who’s looking after me,” he replied.

My heart warmed at his words, just as it had done forty years ago when I had first heard the same words spoken in that very spot. He was a kind and gentle man with none of the conceit one might have expected from a great and famous tenor.

We watched him drive his jaunty blue convertible up the hill of Juniper Street. He gave a gentle hoot on his horn to bid us goodbye.

That scene vanished as quickly as it had begun and reverted to being one of my indelible memories once again. I was alone in a cold and empty house, longing to return to those happy innocent days, sad that my parents, Derek and dear Shandy were gone forever, knowing that the moving van and Helen would soon be here, and knowing too that I couldn’t possibly share what had happened – or what I had imagined had happened – with Helen, or with anyone else on earth for as long as I lived.

Fiona Compton ©

1 August 2011

Updated 3 September 2021.

THE OLD HOUSE – A Jo’burg Story – a pot-pourri – by Jean Collen.

“It’s the big move on Saturday,” said my friend, Helen. “I can’t wait for it to be over.”

“Can I help at all?”

I knew I had to ask although I prayed her answer would be no. Helen is a good friend just surfacing from the morass of her divorce from Charlie. Hence the move from her elegant home, now occupied by his mistress, the soon-to-be Mrs Bryant, Mark 2.

“A red face brick bungalow with a tin roof,” Helen had told me without enthusiasm when she first bought the bungalow. It was all she could afford with the money she had been granted in the divorce settlement.

“Would you really help me?” asked Helen hopefully. “It would be a godsend if you could be at the house to receive the furniture until I get from one place to the other. I’d be quick. You’d only need to be there for an hour – or two at the most.”

“Give me the address and I’ll be there. No problem,” I said, dispensing regretfully with my slothful Saturday plans.

Helen was already fishing around in her copious handbag.

“Twenty-one,” she said, handing a set of keys to me. “Twenty-one, Juniper Street.”

It was a very hot day, but a shiver passed through my body.

“Are you sure of the number?” I asked faintly.

“Yes. Look, the address is on this label attached to the keys in case you forget it. Are you all right, Meg? You’ve gone quite pale. You should forget all that dieting nonsense. It doesn’t do you any good at all.”

“I’ll be fine,” I said, taking the keys from her with a trembling hand. “I’ll see you on Saturday at Juniper Street.”

I drove off abruptly, wondering why I hadn’t blurted out the reason for my discomfiture. Forty years ago, I had been nineteen, still living at home with my elderly parents. 21, Juniper Street had been our address.

I arrived at the bungalow an hour before the removal van was due. I had passed the house now and again on trips to the shopping centre on the other side of the hill. The thick bougainvillea creeper with heliotrope blossoms still enclosed the stoep where we had sat on hot evenings. As I climbed the familiar steps to the stoep, I felt as though I was a young teenager again, arriving home from school to receive a rapturous welcome from Shandy, our little brown and white dog of indeterminate breed.

I was surprised to see that the same wallpaper my parents had plastered on the walls in 1963 was still in the hallway. I could almost smell the goo that pervaded the atmosphere when we were having the place redecorated. I remembered my mother discussing the wallpaper with my singing teacher and the difficulty they were having in finding wallpaper they liked for decorating their new home.

“If you manage to do that job yourself you’ll be a better man than I am, Gungadin!” he had laughed.

I had been curious enough to check the origin of the dated expression and traced it back to Rudyard Kipling.

The telephone, where I had sat for hours, chatting to my best friend, Sally in the days when it cost a tickey to make a call and talk for as long for as we liked, was in the same place in the passage, although it had been replaced by a more up-to-date model than our sombre black set from all those years ago.

Sally and I studied singing with Marina Baxter and Derek Bailey, the famous English singers who had moved to South Africa from the UK in the mid-fifties. We had both been successful in our auditions to join the SABC choir and, at Marina and Derek’s suggestion, had sought each other out at rehearsals. Sally, like me, was originally from Glasgow. We both loved singing, hoped to make careers in music, and we both thought the world of Marina and Derek. Sally, a soprano, was short and plump with piercing blue eyes and honey-coloured hair. She was the youngest of three attractive sisters and was far more outgoing than me. I, a contralto, the only child of elderly parents, was tall and dark and fairly reserved and reticent until I got to know people well enough to relax with them.

The house was completely empty today as it waited for the arrival of Helen’s furniture, but suddenly the phone rang: not the computerised sound of today’s telephones, which, in my advancing years, I cannot always hear clearly. This ring was loud and jangling. No difficulty in hearing the ring, but did I have the right to answer the phone? I hesitated, but the ringing continued. Perhaps it was Helen calling about the movers. Eventually I picked up the receiver.

“Hello,” I said tentatively.

“Is that you, Meg? You sound strange this morning. Did you have a late night?”

It wasn’t Helen after all but the voice was certainly very familiar. It was the voice of a young girl. Usually girls of that age call me Mrs Johnson and ask to speak to one or other of my teenage children.

“Yes, this is Meg. Who’s speaking?” I asked rather suspiciously.

“You’re joking with me,” the girl laughed. “I just wanted to know how your accompanying in the studio went this week. Did you pluck up courage to ask him to dinner? Is he going to come?”

Suddenly I felt cold and shivery. At last I knew who was speaking. I recognised the voice of my best friend, Sally, who had died at the age of nineteen, forty years ago. I was rooted to the spot unable to speak. My younger self took over the conversation, while I, the middle-aged woman, looked on helplessly wondering what was happening to me in our old house.

“What did you sing at your lesson today?” I heard myself asking Sally, looking forward to a long chat about our heroes.

“I cancelled my lesson. I was far too excited to go. Can you keep a secret, Meg? Mum told me not to breathe a word, but I have to tell someone. You won’t believe what has happened to us!”

I waited expectantly. We never cancelled our singing lessons if we could possibly avoid doing so. We’d have to be on the point of going to hospital before we would think of staying away.

“We had a telegram this morning,” Sally said solemnly.

“Oh, I’m sorry. Has someone died?” I asked.

All the telegrams we ever received in our family had born bad news of one kind or another.

“Not that kind of telegram, silly. One from the bank to say we’ve – or rather – Mum has won a prize in the Rhodesian Sweep. Not first prize, you understand, but a fortune all the same.”

She paused tantalisingly.

“How much?” I asked.

“Forty thousand pounds!”

That was a lot of money in 1963. You could retire on the interest of money like that in days when the average wage was about £100 a month. Sally’s father didn’t retire, but he and her mother bought a bigger car, went on a first class trip back to Scotland, and had a kidney-shaped swimming pool built in the back garden.

After we got over the excitement of her parents having riches beyond our imagination, our conversation reverted to how I got on as a very keen, but inexperienced studio accompanist to Derek Bailey.

“Sally, it was wonderful, the best time I’ve had in my whole life. I’ll never forget it as long as I live. He was so kind and understanding. My sight-reading has improved so much, and guess what? He was thrilled when I asked him to dinner and he’s going to take me to Dawson’s Hotel for lunch sometime next week as well.”

Label for Dawson’s Hotel.

Label for Dawson’s Hotel.I was waiting eagerly waiting to hear what she thought of my news, which probably was quite tame in comparison to hers, but the line was dead. She was gone and I had no idea how to get her back again.

I looked into the empty lounge, still with its Adam ceiling and bay lead-light window. Even the fireplace remained although it was fitted with an anthracite heater now. In our day we had an open coal fire which filled the house with comforting warmth we never enjoy in winter today. Periodically the McPhail’s coal truck would arrive to replenish our coal cellar. ‘Mac won’t Phail you,’ read the slogan on the truck.

Our big radio with its green cat’s eye to fine-tune the stations had stood on a table next to the fireplace and was the sole source of our entertainment. The Nationalist government had banned TV from South Africa until 1976, fearing that the population might be unduly influenced by radical ideas from the outside world. The piano was in the opposite corner, where I must have distracted the neighbours practising singing and piano scales early each morning.

As I stared round the room remembering the way it had been, bemused by the vivid conversation I had just had with dear Sally, who had died so many years ago, I suddenly saw my parents and Derek, chatting together over an after-dinner whisky. I was there watching my younger self, clad in that bottle green velvet dress I had thought so attractive. It was the first time I had accompanied for Derek in their singing studio on the eighth floor of a building in the centre of the city, while Marina was away on a holiday trip. He was on his own at home, so my mother had suggested he should come to dinner one evening.

He loved our little dog, Shandy, and encouraged her to sit on his lap, shedding her hair on his smart Saville Row suit.

“My girl friend,” he said contentedly, sipping the whisky, stroking Shandy, and regaling us with tales of their days in variety when they had appeared on the same bill with the likes of Max Miller. Rawicz and Landauer and Albert Sandler.

Marion Rawicz and Walter Landauer (pianists)

Marion Rawicz and Walter Landauer (pianists) Albert Sandler (violinist)

Albert Sandler (violinist)The scene faded as quickly as it had begun and, now I saw myself standing on the bougainvillea-covered stoep with my parents bidding him goodbye after our wonderful evening together.

“Thank you for looking after Meg,” said my mother.

He smiled at me in a kindly fashion. “I think it’s Meg who’s looking after me,” he replied.

My heart warmed at his words, just as it had done forty years ago when I had first heard the same words spoken in that very spot. He was a kind and gentle man with none of the conceit one might have expected from a great and famous tenor.

We watched him drive his jaunty blue convertible up the hill of Juniper Street. He gave a gentle hoot on his horn to bid us goodbye.

That scene vanished as quickly as it had begun and reverted to being one of my indelible memories once again. I was alone in a cold and empty house, longing to return to those happy innocent days, sad that my parents, Derek and dear Shandy were gone forever, knowing that the moving van and Helen would soon be here, and knowing too that I couldn’t possibly share what had happened – or what I had imagined had happened – with Helen, or with anyone else on earth for as long as I lived.

Jean Collen ©

1 August 2011

Updated 3 September 2021.

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-613281784be54', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });July 1, 2021

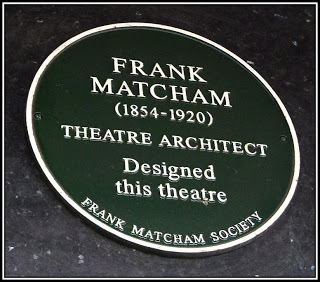

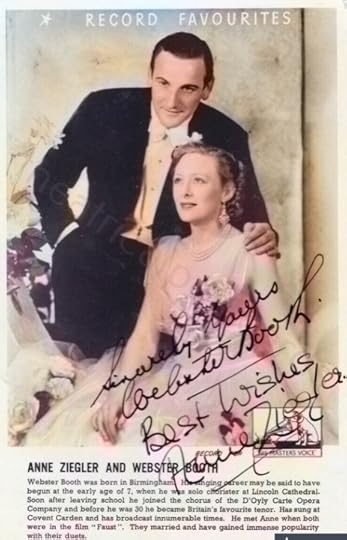

WEBSTER BOOTH AND ANNE ZIEGLER: APPEARANCES AT THE BRISTOL HIPPODROME

The Bristol Hippodrome opened in December 1912, was the last theatre designed by Frank Matcham. When Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth appeared at the Hippodrome it was principally a variety theatre, but their last appearance in the nineteen-fifties was in the musical And So to Bed. Today it is a venue for opera, ballet and musicals, but it is too big for the presentation of straight drama, seating 1,951 people.

All photographs of the Bristol Hippodrome were taken by Charles S. P. Jenkins in 2011 when he went to Bristol to see the production of South Pacific. I am very grateful to him for allowing me to use his excellent photographs in this post and for creating collages of his photographs for me.

All photographs of the Bristol Hippodrome were taken by Charles S. P. Jenkins in 2011 when he went to Bristol to see the production of South Pacific. I am very grateful to him for allowing me to use his excellent photographs in this post and for creating collages of his photographs for me.

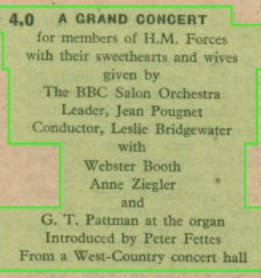

With the declaration of war, Webster returned to Bristol after singing at two concerts in Buxton with Anne, to join the variety department of the BBC. Others who had been chosen to join this department were Tommy Handley, Vera Lennox, Ernest Longstaffe, Sam Costa, Charles Shadwell, Doris Arnold, Betty Huntley-Wright, Leonard Henry and others. It had been pre-arranged that if war was declared the BBC variety department would broadcast from the Bristol studios as Bristol was deemed to be safer than London in the event of bombing. While he was on the staff of the BBC, he gave recitals on air several times a day, either as a soloist or with other BBC staff singers like Betty Huntley-Wright. When the bombing became heavy in Bristol, the BBC also broadcast from Evesham in Worcestershire and Bangor in North Wales.

London theatres had initially closed at the outbreak of war, so after a month living in London on her own with few engagements, Anne moved to Bristol and managed to find some broadcasting and concert work there. Anne and Webster lived at 27 Grove Road, Clifton during their time in Bristol. Webster gave up the staff job with the BBC at the end of 1939 when London theatres re-opened once again.

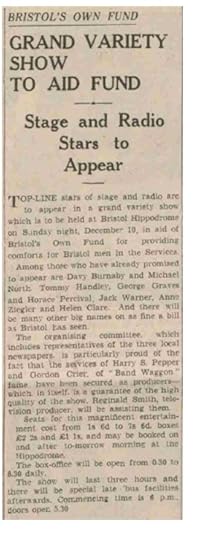

Anne appeared in an All Star Variety concert on 10 December 1939 in aid of Bristol’s Own Fund in the presence of the Lord Mayor and Sheriff of Bristol. The star-studded cast included Suzette Tarri, Helen Clare, Horace Percival, Tommy Handley, Davy Burnaby, Michael North, Dick Bentley, George Moon, Phil Green, Jack Warner, Jack Train, Jean Colin, Fred Yule, Richard Hassett, Denny Dennis, Mackenzie Twins, Alan Paul, Billy Ternent, Bryan Michie, Doris Arnold, Jack Hylton’s Band, Bristol Aeroplane company Band.

Just before Christmas of 1940 Webster was singing in a performance of Messiah in Manchester while Anne was in Bristol once again for a radio broadcast. Walter Legge, the record producer, who was looking after their recordings at HMV at that time, was staying at the Royal Hotel, where Anne was staying also. At breakfast the following morning he told her tactlessly, knowing that Webster had been singing in Manchester, that Manchester had been razed to the ground the previous night. Anne was distraught at the news and tried to phone Webster, but the lines were unavailable for non-priority calls. She travelled back to London, anxious to see whether Webster had arrived back at midday as planned, but there was no sign of him. Anne began to fear the worst. He eventually reached home that evening once trains from Manchester had started running again. By this time she was quite frantic with worry, but relieved and thankful that he had not lost his life in the dreadful air raid.

23 March 1941.

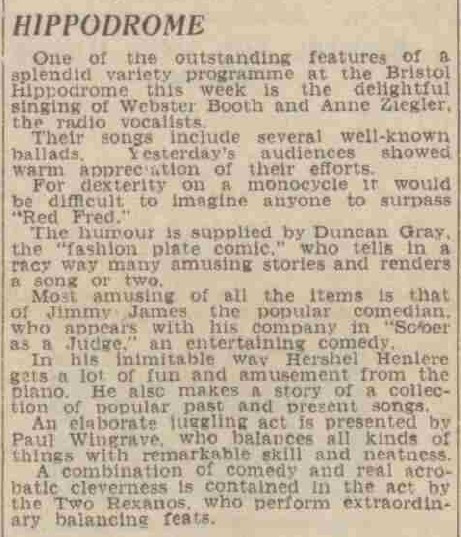

23 March 1941. After the war on August 1-6 1949 Webster and Anne appeared in variety at the Bristol Hippodrome with the Rudells, Albert Whelan, Frank Preston, MacDonald and Graham, Charles Ancaster, Kardoma, and Johnson Clark.

Their last appearance at the Hippodrome was from April 19-24 1954 when they played the roles of King Charles II and Mistress Knight in the touring production of Vivian Ellis’s musical play, “And So to Bed” with Arthur Riscoe, Barbara Shotter, Colin Hickman, Kenneth Collinson, David Sharpe, Mostyn Evans, Richard Curnock, Gwen Nelson, Hazel Jennings, and Joy Mornay.

Anne and Webster in And So to Bed

Their last appearance at the Hippodrome was from April 19-24 1954 when they played the roles of King Charles II and Mistress Knight in the touring production of Vivian Ellis’s musical play, And So to Bed with Arthur Riscoe, Barbara Shotter, Colin Hickman, Kenneth Collinson, David Sharpe, Mostyn Evans, Richard Curnock, Gwen Nelson, Hazel Jennings, and Joy Mornay.

Jean Collen updated 1 July 2021.

April 29, 2021

Protected: PERSONAL MEMOIR 3 – 1973 onwards.

This post is password protected. You must visit the website and enter the password to continue reading.

Protected: A PERSONAL MEMOIR -1965 onwards.

This post is password protected. You must visit the website and enter the password to continue reading.