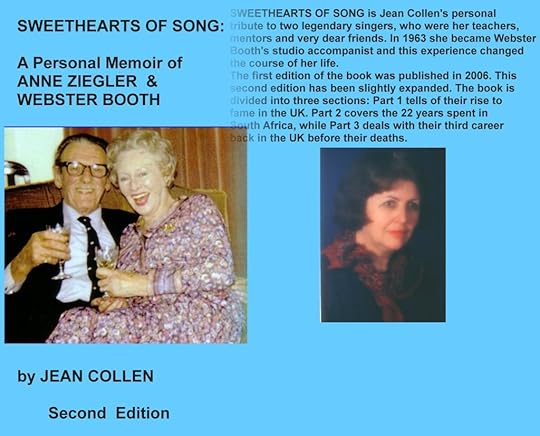

Jean Collen's Blog, page 4

November 25, 2022

WEBSTER BOOTH AND ANNE ZIEGLER IN PANTOMIME.

WEBSTER BOOTH

Tom Howell, leader of Opieros and Webster Booth.

Tom Howell, leader of Opieros and Webster Booth.The only times Webster Booth appeared in pantomime were during the winter seasons of 1927 and 1928 when he was a young man in his mid-twenties, He and Tom Howell had been performing together in Tom Howell’s Opieros for several years, appeared together in two of Fred Melville pantomimes at Brixton. The first pantomime in 1927 was St George and the Dragon. St George was played by principal boy, Vera Wright, while Webster played King Arthur.

30 December 1927, Saint George and the Dragon, The Brixton – On Monday, December 26 1927, Mr Frederick Melville presented here his twentieth annual pantomime, written and produced by him, the music composed and arranged by F Gilmour Smith.

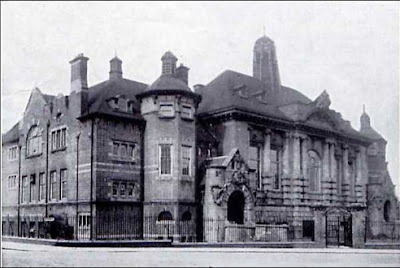

Brixton Theatre, renamed the Melville Theatre but destroyed during World War 2.

Brixton Theatre, renamed the Melville Theatre but destroyed during World War 2.St George of England: Miss Vera Wright, St Patrick of Ireland: Miss Eileen O’Brian, St Andrew of Scotland: Miss Maggie Wallace, St David of Wales: Mr Lloyd Morgan, St Denis of France: Miss Marie Fontaine, St Anthony of Italy: Miss Lily Wood, St Michael of Russia: Miss Agnes Moon, King Arthur of England: Mr Webster Booth, Sir Mordred de Killingsbury: Mr Tom Howell, Stephen Stuffingley: Mr C Harcourt Brooke, Tricky Dicky: Mr Willie Atom, Princess Guinevere: Miss Doris Ashton, Fairy Starlight: Miss Hilda Goodman, Mary Fairly: Miss Marjorie Holmes, Demon Ignorance: Mr Fred Moule, Dame Agatha Lumpkin: Mr Leslie Paget, Jerry Lumpkin: Mr Larry Kemble.

One of the crits reads as follows:

There is a fine patriotic flavour, to say nothing of sundry allusions to the need for keeping old England healthy, both bodily and mentally, by sweeping out the germs of disease and distrust, all worked in the usual deft Melvillean fashion in this year’s Brixton pantomime. Choosing the unusual subject of St George and the Dragon, Mr Melville has written a story at once original and arresting.

The story is sustained by a clever company through 12 scenes, some of them notably the Ancient Village near London, King Arthur’s Banqueting Hall, the Hall of the Seven Champions with the knightly Saints in shining armour, and the King’s Palace being the setting of striking beauty, splendid too, wherein, as in former years, the clever pupils of Miss Euphan Maclaren, led by Miss Babs Livesey and with a graceful solo dancer in Miss Margery Holmes, perform most charmingly their operatic ballet.

Considerable care has been spent on the dressing of this, one of the finest of the Brixton’s many pantomimes. No more inspiring figure could easily have been found for the part than Miss Vera Wright, who carries the role of St George with a fine air of dignity. Solos are not numerous in the pantomime, team work, duets, and concerted items comprising most of the vocal side, but Miss Wright gives a dramatic rendering of The Dream Passes, besides duets, and Say it again with Guinevere, a trio with Guinevere and the King, In a Little Spanish Town and another with Guinevere and the Fairy, One Summer Night.

Needless to say, with Miss Doris Ashton playing the part, Guinevere is one of the outstanding vocal successes of the pantomime. Miss Ashton has her chief chance in a medley of present day popular songs and many old favourites, with interpolated selections on the violin, her duets with St George and the one with the King, When You Played the Organ and I Sang the Rosary winning favour.

Mr Webster Booth adds stateliness and a pleasing tenor voice, heard in England, Mighty England and Tired Hands, and with Sir Mordred, Tenor and Baritone, to the part of the King. Mr Tom Howell’s Sir Mordred is a sound piece of character work, though he finds small scope in the part for his powerful baritone. Messrs C Harcourt Brooke and Willie Atom are an always amusing pair as Steven Stuffingley and Tricky Dicky, and Mr Leslie Paget’s Dame Agatha Lumpkin, with typical dame numbers in We’re All Getting Older Together and I’m a Widow is full of humour. It is Mr Larry Kemble, who as Jerry Lumpkin, walks away with the comic honours. He gives an original twist to the ubiquitous Stewdle-oodle-oo number, and can dance nimbly, but it is in his funny bicycle act and his deadly serious attempts to teach the Brixton’s popular musical director, Mr F Gilmour Smith, his business that his talents as a humorist shine most brightly. Miss Hilda Goodman is such a charming Fairy Starlight that she almost has us answering in the affirmative when she sings Do You Believe in Fairies?

A word of praise must also be given to ladies who impersonate the National Patron Saints with such dignity. Mr Chris Mason, the manager smiles as one who has “another winner”. (Stage)

December 1927 ST GEORGE AND THE DRAGON: PANTOMIME, BRIXTON THEATRE Fred Melville production – At the Brixton Theatre this year there is a patriotic pantomime, of which the hero is St. George of England, while villainy is represented by the Dragon and attendant demons. During the course of the pantomime these two forces wage a combat which quite puts to shame the mythical struggle on which the reputation of our patron saint is based. Although in the pantomime the Dragon always gets the worst of it, yet he is an unconscionable time a-dying, while, in the original legend, St George slew his opponent with uncommon dispatch and neatness. Fortunately, St. George has a number of distractions in this new version of his life, and, although the combat is a protracted one, he is able to have refreshing waits in between the rounds while young women sing, dance, and smile and while comic men make diverting remarks and execute quaint antics. His struggle may be a longer one, but it is at least much more pleasant. One’s sympathy, on the other hand, goes out to the Dragon, who is not so much slain as slowly tortured to his end.

St. George, of course, is a lady, and Miss Vera Wright makes him an excellent principal boy. She sings well, poses attractively, and generally makes one feel what a good kind of fellow St. George must have been. She is in high company, for there is King Arthur (Mr.Webster Booth) to give encouragement, some of it in song, and there is the Fairy Starlight (Miss Hilda Goodman), as determined a good fairy as ever rescued virtue from the hands of vice during the Christmas theatre season. There is also Princess Guinevere, the lady in the case, attractively played by Miss Doris Ashton, and “comic relief,” provided by Mr. Leslie Paget and Mr. Larry Kemble. (Times)

1928’s pantomime at the Brixton Theatre was a freely adapted version of Babes in the Wood. Once again Vera Wright played principal boy, this time in the role of Robin Hood. 20 December 1928, written by Frederick Melville. Principal boy, Vera Wright; principal girl, Teresa Watson; principal comedians, Tom Gumble and Jimmy Young; Fairy Queen, Gwen Stella, baritone Tom Howell; tenor Webster Booth. Specialities by Euphan Maclaren’s Operatic Dancers, Babette, Grar and Grar. Principal scenes: The Village, The Schoolroom, Ballet, Children’s Bedroom, Sherwood Forest, and Palace. Stage manager, Fred Moule. Produced by Frederick Melville on December 26, at 2pm, for run of about 7 weeks.

27 December 1928, BABES IN THE WOOD. PANTOMIME AT BRIXTON S.W. Fred Melville production – Comical Pantomime. Twice Daily, at 2 and 6.30. Seats booked. 8/6, 4/9, 5/9. Children half-price to Matinees. ‘Phone, Brixton 0050.

The Babes in the Wood, which opened at Brixton Theatre yesterday, departs freely from the conventional story, as any pantomime may do. The father of the children (not according to accepted legend) leaves with King Richard to fight the Saracen, and Maid Marion steps out of a wholly different tale to become their nurse. It is only natural, therefore, that Sherwood Forest should be just on the other side of the hill from the village green, and that Robin Hood should arrive at the right moment to tweak the wicked uncle’s nose and scatter the contents of that rascal’s purse among the villagers. It was also in the appropriate order of things that Little John and Will Scarlet (Webster Booth), and a band of archers should then come to help the great outlaw; but, if he had already beaten the local Dogberry and, the watch, they merely stayed to enjoy the dance. This and much more is woven round the old story of the babes and their friends the robins in the wood. If a pantomime is still to be regarded, as it ought to be, as primarily a play for children, this one preserves the right proportions to that end. The fairies cast their spell over whole scenes, and the babes are led through enchanted valleys where fairies and elves are never tired of dancing. The robbers (Jimmy Young and Tom Gamble) are fierce in appearance as the tale requires, but they are amusing, and they provide most of the comedy, with the wicked uncle (Fred. Moule) as a foil for their wit, the latter enjoying his lighter moments when he is not plotting mischief. Miss Vera Wright (Robin Hood) and Miss Teresa Watson (Maid Marion), who are respectively the principal boy and the principal girl, sing effectively, and the choruses and dances help to make a good Christmas entertainment. (Times)

In 1930 Webster made his West End debut in The Three Musketeers at Drury Lane and stopped working with the Opieros. He never appeared in pantomime again.

ANNE ZIEGLER

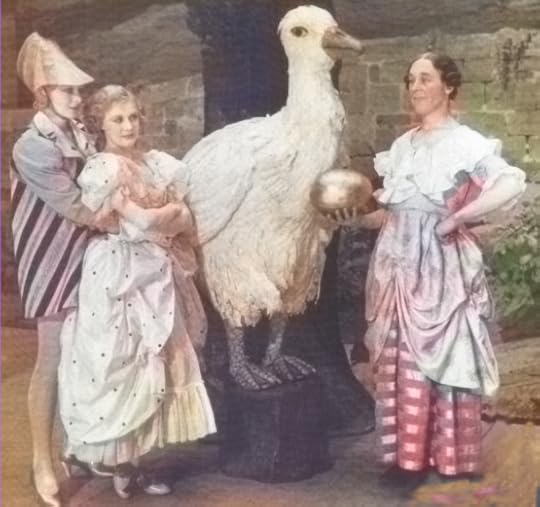

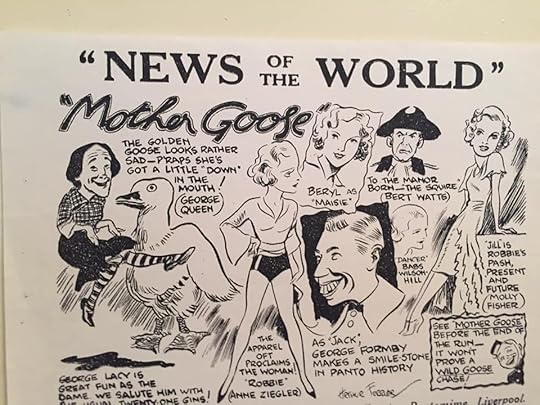

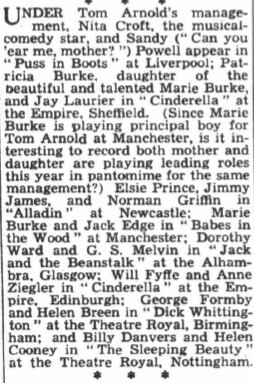

Anne Ziegler had a great deal more to do with pantomime throughout her career except for the period when she and Webster were at the top of the tree in the 1940s and she didn’t have enought time to appear in pantomime. Her first pantomime was a triumphant return to her home when she was principal boy in MOTHER GOOSE at the Liverpool Empire. Tom Arnold presented the pantomime with Anne as Principal Boy, George Formby, George Lacey, Mollie Fisher (principal girl), and Babs Wilson-Hill (principal dancer).It was in this production that Anne first met Babs Wilson-Hill (Marie Thompson), who was to become her life-long friend.

Anne as principal boy, Mollie Fisher, principal girl, and George Lacey (Dame) in Mother Goose. 1935.

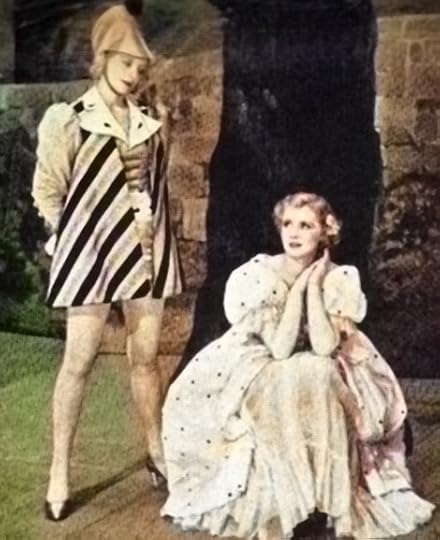

Anne as principal boy, Mollie Fisher, principal girl, and George Lacey (Dame) in Mother Goose. 1935. Anne and Mollie Fisher in a scene from the panto.

Anne and Mollie Fisher in a scene from the panto.

Anne appeared in two more pantomimes in the 1930s. In 1936 she appeared in Cinderella at the Edinburgh Empire Theatre with Will Fyffe as the Dame. Babs Wilson-Hill was also the principal dancer in this production.

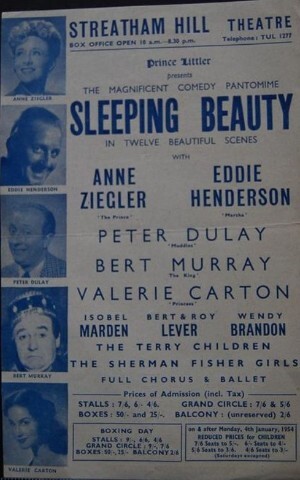

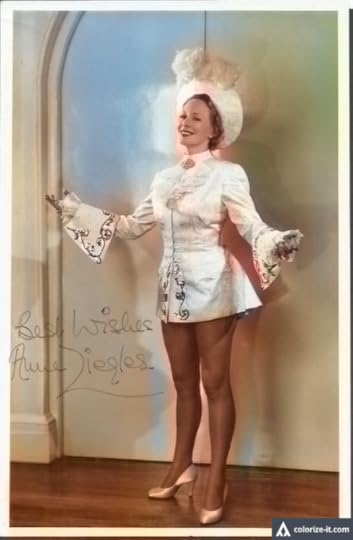

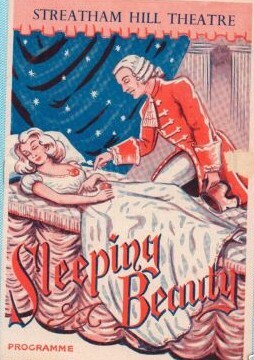

In 1938 to 1939 Anne was once again principal boy in The Sleeping Beauty at Streatham Hill Theatre.

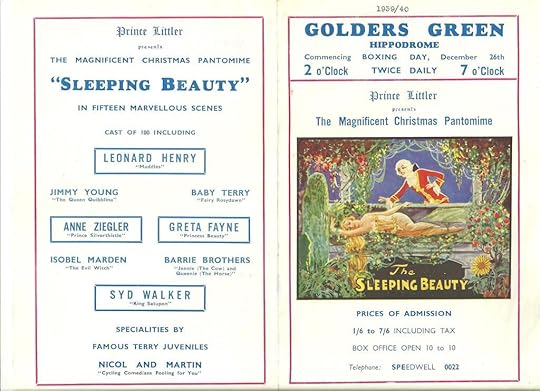

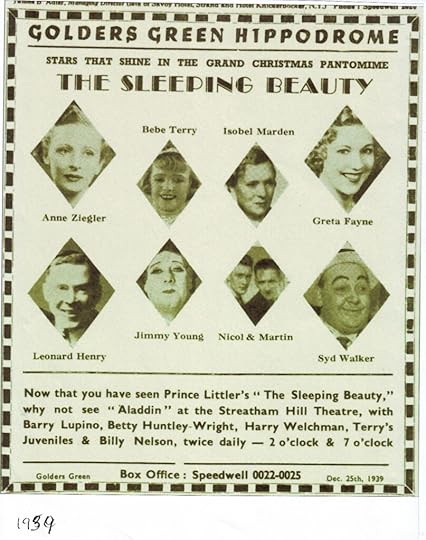

Despite the outbreak of war, Anne was principal boy at Golders Green Hippodrome in another production of The Sleeping Beauty as Prince Silverthistle.

This was to be Anne’s last appearance in panto for some time. When she and Webster went on the variety circuit as a double act they soon reached the pinnacle of their fame as duettists and were kept extremely busy. It was not until 1953 that Anne made another appearance in pantomime, this time in another production of The Sleeping Beauty at Streatham Hill.

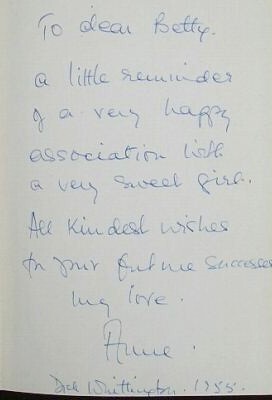

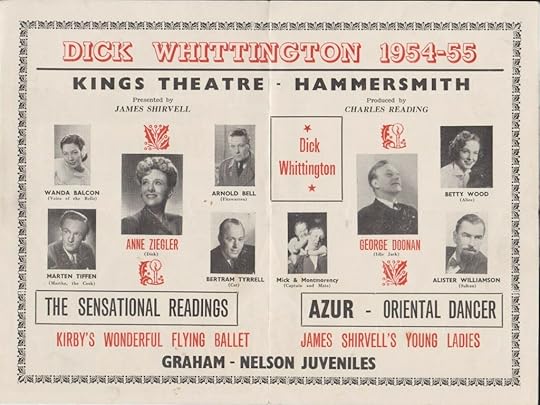

The following year from 1954 to 1955, Anne was principal boy at the King’s Theatre, Hammersmith in Dick Whittington. Anne and Webster’s joint autobiography had been published in 1951 and she presented the book to Betty Wood, a young member of the cast and inscribed it as follows:

That was Anne’s last appearance in panto in the UK for quite a while.

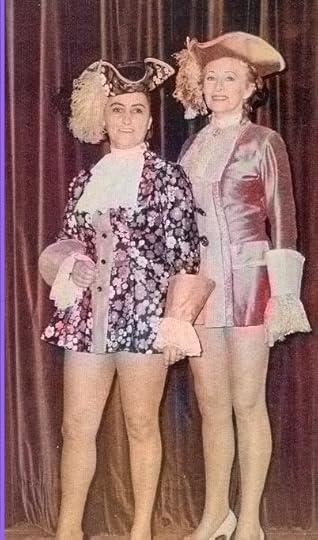

When Anne and Webster lived in the small town of Knysna, South Africa, Anne appeared as principal boy for the last time, at the age of nearly 60! There was a write-up about this performance in one of the national newspapers.

Anne and their singing pupil, the late Ena Van den Vyver, were the two principal boys in that panto.

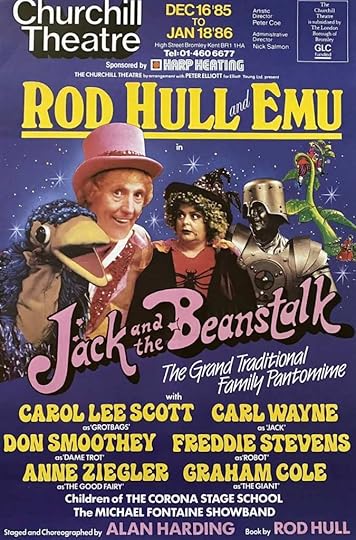

Anne and their singing pupil, the late Ena Van den Vyver, were the two principal boys in that panto.The last panto in which Anne appeared was not a happy experience for her. She was asked to play the Good Fairy in a production at the Churchill Theatre, Bromley for the 1985/1986 season. Webster had died the year before and the terms of her contract were changed without consultation. Because of this and also because she developed a virus, she was able to leave the show two weeks before it closed. She told me that she had no wish to take any other part in the theatre as it had changed so much since the days when they were performing regularly.

Jean Collen, November 2022.

October 27, 2022

STAFF EMPLOYED BY WEBSTER BOOTH AND ANNE ZIEGLER

Crowhurst, 98 Torrington Park, Friern Barnet. Photo: The late Pamela Davies.

Crowhurst, 98 Torrington Park, Friern Barnet. Photo: The late Pamela Davies.Just when I thought I had exhausted every aspect of Anne and Webster’s busy lives I heard from Martin Threadgold who was researching his family tree. He had a collection of photographs of Anne and Webster dating from 1943 when they were living at 98 Torrington Park, Friern Barnet which had been given to his grandmother, Rose Threadgold. He wondered whether she had been employed by the Booths. Although I could not find her name mentioned in any document or in Duet, their joint autobiography, I thought it would be interesting to look at some of the people who had been employed by them over the years – either as domestic workers or – as in the case of F.W. Gladwell, their manager, and Charles Forwood, their accompanist for many years.

TILLY RIDLEY

As early as 1930, when Webster was a young man of 28, he employed a cook-general called Mathilda from Sunderland, someone who was to play an important role in the lives of Webster and Anne. Webster told me that Tilly had been madly in love with him and didn’t mind if he occasionally didn’t have enough money to pay her wages. She went on working for him all the same! He even said that looking back, he might have done a lot worse than to have married her as she was a charming person who knew how to behave properly.

Lauderdale Mansions.

Lauderdale Mansions.Anne employed a cook-general of her own and this lady remained with them when she and Webster married in 1938 and were living in Anne’s flat in Lauderdale Mansions. At this time, Tilly returned to Sunderland and married her boyfriend, Ivor Ridley a ship’s electrician. But that was not the last they had seen of Tilly.

In Anne and Webster’s join autobiography, Duet, published in 1951, Anne wrote of Mathilda as follows: ‘A little slip of a thing with a strong Geordie accent, she had come to London from Sunderland, after working in service in big houses there. Her type, I think, does not exist today; her pride was a spotless house, her work was finished only when she could think of nothing else to do, and her greatest joy was a pile of empty dishes! For eight years she looked after Webster, and in that time there was only one disagreement. Tilly had been out to get some lilac for the house, and Webster, who is very quick-tempered, thought she had been lazing and reprimanded her sharply. When he saw the lilac he was desperately sorry, but would not say so. Years later he learned that she had cried all night.

Tilly came to look after them in their flat when they were working in Bristol during the early part of the war. Said Anne: ‘Webster has told how dirty that flat was when we went into it, but after forty-eight hours Tilly had it shining!’

CHARLES FORWOOD

Anne and Webster singing with Charles Forwood at the piano.

Anne and Webster singing with Charles Forwood at the piano.When Anne and Webster took the momentous decision to go “on the halls” which meant they would be performing twice nightly they were lucky enough to obtain the services of Charles Forwood as their accompanist. Webster once mentioned that they paid Charles Forwood £30 a week for his services. They paid this from the fee they received which was often £150 to £200 per concert. They admired him very much indeed and he remained with them until his health began to suffer and he did not feel well enough to join them on the tour of New Zealand and Australia in 1948.

TILLY AND JOHANNA

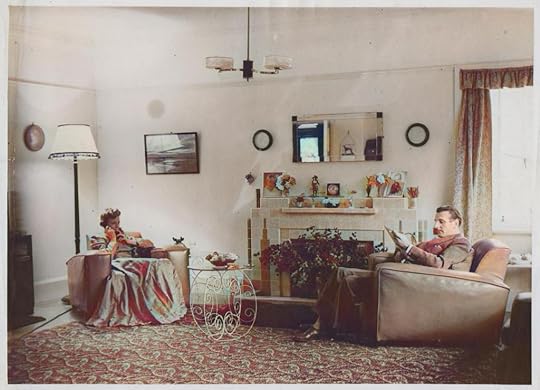

Anne and Webster relaxing in the lounge at Crowhurst. Thanks to Martin Threadgold for allowing me to use this photo.

Anne and Webster relaxing in the lounge at Crowhurst. Thanks to Martin Threadgold for allowing me to use this photo.Tilly continued to work for the Booths in their large home, Crowhurst, in Friern Barnet after the stint in Bristol was over and was with them during the war. They employed an Austrian refugee called Johanna to help Tilly with the work. Anne wrote of Johanna: ‘She was a wonderful worker, but had a constant cry, “In my country we always use twelve eggs in a cake!” or, “In my country only the poor eat herrings!” She had Tilly’s horror of dirt, but she had her own personal method of sleeping, which defied everything Hitler did to disturb it. Often we have wakened her when bombs were thudding all round, to hear the cry “I am so tired!”, and watch her promptly fall asleep again. When the war was over Johanna went back to her country – though not, I fear, ever again to use twelve eggs in a cake there.’

Introducing Smoky to the cat in the garden at Crowhurst!

Introducing Smoky to the cat in the garden at Crowhurst! Webster, Johanna and Anne working in the garden at Crowhurst. Thanks to Martin Threadgold for this photo.

Webster, Johanna and Anne working in the garden at Crowhurst. Thanks to Martin Threadgold for this photo.FWJ GLADWELL

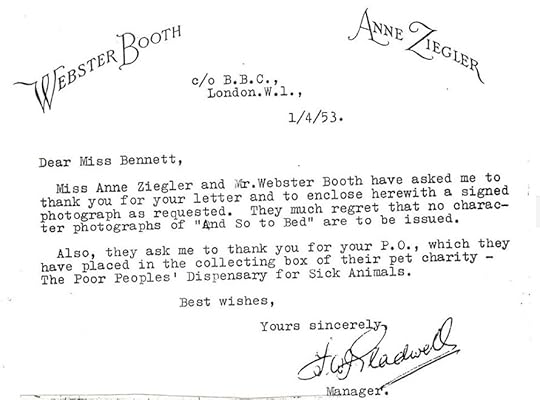

A letter from FWJ Gladwell to Miss Bennet on 1 April, 1953

A letter from FWJ Gladwell to Miss Bennet on 1 April, 1953In 1943 Tom Arnold staged a revival of The Vagabond King. FWJ Gladwell was Tom Arnold’s manage of The Vagabond King company. Anne and Webster were drawn to him because he loved animals and suggested that they could put Ginger, their cat into a cats’ private hotel when they were on tour with the show. When the tour ended Mr Gladwell became their personal manager, dealing with letters, fan-mail, contracts and songs sent to them by publishers and amateurs alike. Anne and Webster always answered fan mail personally although he occasionally forged their names on photographs sent to fans. He even managed to prepare meals for them if the cook was out and look after the cats and dog!

AUTOGRAPHED PHOTOS TO JOHANNA (thanks to Martin Threadgold)

We wondered why Johanna did not take these photographs with her on her return to Austria. The photographs were from Anne and Webster’s appearance in The Vagabond King.

TILLY AGAIN

When Anne needed a dresser during the run of Sweet Yesterday, Tilly came back to work for Anne in this new role. When her husband came home from the war they settled down in Newcastle, where he got a job on the shipyards.

WALTER WADE

After the war they advertised for domestic staff. Instead of a woman applying for the post, they received a reply from Walter Wade, who had been a dietician cook on the RAF. He said he was perfectly able to do housework and cooking so Anne and Webster decided to give him the job. He was an excellent cook and. at first, worked with a parlour maid to help with the housework.

When Anne and Webster sold Crowhurst and moved to the smaller Frognal Cottage in Hampstead, Walter, or Bill as they now called him, said that he would prefer to do all the work on his own rather than have a maid to help him. Apparently he continued cooking, cleaning the house and doing most of the washing rather than send it to the laundry! He was able to sew and mend, arrange flowers and look after the animals into the bargain!

102 Frognal, Frognal Cottage, Hampstead.

102 Frognal, Frognal Cottage, Hampstead.HILDA

When Anne and Webster moved to South Africa in 1956 they found a wonderful woman from St Helena to look after them in their various homes in Johannesburg. Her name was Hilda, a charming woman who wore her long dark hair in a bun. Occasionally she came up to the studio, and periodically she returned to St Helena on holiday. The only way to reach St Helena in those days was by mailship so she took a Union Castle liner there and caught the returning Union Castle liner back to Cape Town six weeks later. When she answered the telephone it was sometimes difficult to know whether it was Hilda or Anne speaking! She was the same age as Anne and returned to St Helena after the Booths moved to the Cape in 1968. Anne told me that she still corresponded with her many years later.

Pretoria Castle. Hilda may have travelled on this ship on her way to or from St Helena.

Pretoria Castle. Hilda may have travelled on this ship on her way to or from St Helena.KNYSNA, SOMERSET WEST AND BACK TO THE UK.

By the time I visited their home in Knysna in 1973 they did not have any permanent staff and when I visited Anne in Penrhyn Bay, North Wales in 1990, six years after Webster’s death, Anne said that she missed having permanent staff. She had her life-long friend and fan, Jean Buckley who lived nearby and who was always willing to take her to various places. She even helped out in the garden of the bungalow after Anne’s gardener stopped working. Sadly, they fell out a few years before Anne’s death and were never reconciled. Sally Rayner, a masseuse, took Jean’s place and helped her a great deal. Sadly, Sally is now dead.

Anne and Jean Buckley before the quarrel.

Anne and Jean Buckley before the quarrel.Her kind home help, Gwen Winfield, was in her forties. Her husband’s parents owned the Orotava Hotel where I had stayed in 1990, and now that Jean was no longer a friend Anne often went shopping with Gwen. She also had a meals-on-wheels service several times a week. She told me that she did not have the appetite to eat the meal all at once but saved the rest for the following day. When Anne died many of the ladies who worked for the meals-on-wheels service attended the funeral service.

Anne and Webster had been at the top of their profession in the UK for sixteen years and they had lived very comfortably during that time. Having looked at the staff they employed and the places where they had lived, it is rather sad to see the decline in their fortunes over the years. They were never bitter about it and hardly ever mentioned their fame and the opulence of their lives when they were at the top.

I’m afraid I have not managed to find out more about Rose Threadgold’s association with Anne and Webster but I am grateful that her grandson, Martin, gave me permission to use the photographs which had been given to Rose. I hope Martin finds out more about his grandmother as he continues to researche his family tree.

Jean Collen

27 October 2022.

September 10, 2022

WEBSTER BOOTH AND ANNE ZIEGLER’S ASSOCIATION WITH ROYALTY.

With the recent sad death of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II at the age of 96, I thought I would examine Webster and Anne’s association with British Royalty over the years.

They first went on the Variety Circuit in 1940, during World War II when Royal Variety Concerts were not held because of security reasons, so it was not until the Victory Royal Variety Concert on 5 November 1945 (their seventh wedding anniversary) that they appeared in one of those illustrious concerts.

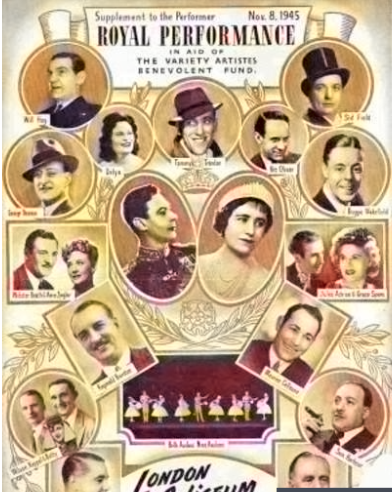

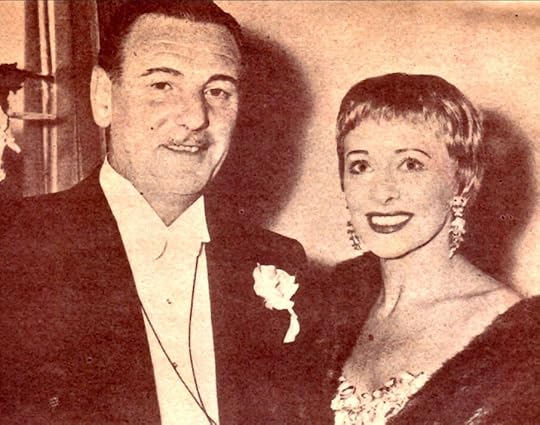

Webster and Anne at the rehearsal for the Royal Variety Performance. 5 November 1945.

Webster and Anne at the rehearsal for the Royal Variety Performance. 5 November 1945.6 November 1945 – King and Queen at the Coliseum. The

Royal Variety Performance: The King and Queen were the

guests at the London Coliseum last night of the Variety

Artistes Benevolent Fund and Institution for the first Royal

performance held in aid of the fund since the outbreak of war.

They were accompanied by Princess Elizabeth and Princess

Margaret Rose. As the King, who was in naval uniform,

stepped into the flower-decked box an audience

representative of the light theatre in all its aspects rose and

sang the National Anthem. All was, as nearly as it could be, as

it had been in the old days. The famous globe on the roof of

the Coliseum was alight, and the audience had contrived to

put up a more uniform display of formal evening dress than

has been seen in a theatre for some years, a somewhat

arbitrary putting forward of the hands of the clock on which

more than one comedian commented with more wit than

kindness. The programme was, just as in the old days, as

exact a reflection of the modern music hall at its best as it was

humanly possible to make it.

At the top of the bill was the irrepressible Mr. Tommy

Trinder. who dismissed the orchestra and at once established

the intimacy within which we no longer think of a comedian’s

jokes as being either good or bad: each adds to our

comfortable enjoyment of his personality.

Among other comedians well able to top any ordinary bill were Wilson,

Keppel, and Betty – the two neatly ludicrous gentlemen from

ancient Egypt and the smoothly gliding burlesque of

Cleopatra. Mr. Sid Field presented the literal-minded golfer

whose failure to comprehend the rather queer language of

golfers turns his lesson into a boxing match. Mr. Vic Oliver

struggled with The Unfinished Symphony, gravely

handicapped by a piano so decrepit that he had in the end to

take his tools to it. Mr. Will Hay broke his mind afresh on the

pupils of St. Michael’s, one of them intolerably smart, another

intolerably polysyllabic, and a third intolerably dumb, all

familiar but with the freshness that comes from excellent

timing. Mr. George Doonan was, as usual, the life and soul of

a street corner party, and Mr. Duggie Wakefield and his

confederates became inextricably mixed with the inner tubes

of motor wheels. A corner of the programme between the

comedians, the romantics and the clever ones was agreeably

tenanted by Mr. Maurice Colliano and his troupe of eccentric

dancers.

Mr. Webster Booth and Miss Anne Ziegler, Delya,

and Mr. Jules Adrian and Miss Grace Spero warbled or fiddled

for the romantics; the Nine Avalons took the breath away with

their feats on roller skates; and, for spectacle, there were two

set pieces from The Night and the Mystic, that charmingly

elaborate fiesta, and the Masque of London Town, and an

exciting finale to which theColiseum chorus and corps

de ballet contributed handsomely.

Artists appearing at the Royal Variety Concert.

Artists appearing at the Royal Variety Concert.24 May 1947 – Advertiser, Adelaide: Queen Mary at 80 –

Best Loved Figure in the Empire, London 23 May

Queen Mary, the most respected and perhaps the

best-loved figure in Britain, whom the King and the Queen

frequently consult on Royal Family policy, will be eighty on

Monday, and at eighty she remains one of the most energetic,

level-headed and clear-sighted women alive.

Proof of the affection with which the nation regards

her will be shown when a special three-hour radio programme

in commemoration of her birthday will be broadcast next

Friday.

It is expected that the broadcast will break all

previous listening records, even those for Mr Churchill’s

wartime speeches, because it is known that Queen Mary

herself is selecting the items and performers. Moreover, she

will probably visit the theatre at Broadcasting House

performance of a new thriller which Agatha Christie – Queen

Mary’s favourite author of “who-dunnits” – has been specially

commissioned to write.

Queen Mary’s favourite artists include Tommy

Handley and singers Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth, who

will participate in the variety programme, while the musical

programme will consist of items typical of the whole British

Isles. In addition, a special birthday television programme is

being arranged.

Radio Times

On Friday the Light Programme will devote the entire evening

between 7.15 and 10.00 pm to a celebration in honour of the

royal birthday. Listeners will hear a Gala Variety Show which will include such established favourites of radio as Richard Murdoch and Kenneth Horne, Elsie and Doris Waters, Tommy Handley, Anne Ziegler and

Webster Booth, Eric Barker, and Albert Sandler. The celebration will close with a special performance of old-time dance music in Those Were the Days… All the contributions to the evening broadcasts have been approved by Queen Mary.

30 May, 1947 – Broadcast, Gala Variety: Anne and Webster

sang in this broadcast for Queen Mary’s eightieth birthday.

Queen Mary had chosen their act as one of her favourites.

When I had the pleasure of being presented to Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, at the end of 1967, she told me that Anne and Webster had been favourite artistes of the late Queen Mary.

Shortly before they left for their tour to New Zealand and Australia they were invited to sing for King George and Queen Elizabeth and their daughter, Princess Margaret.

26 February 1948 – Morning Service in King’s Private

Chapel, Windsor. Webster Booth and Anne Ziegler had the

honour of singing to the King and Queen and Princess

Margaret last Sunday during the morning Service in their

private chapel adjoining Windsor Royal Lodge. They sang

excerpts from Messiah and a hymn by Vaughan Williams.

They were afterwards presented to their Majesties in Royal

Lodge and spent half an hour chatting with them about their

forthcoming world tour.

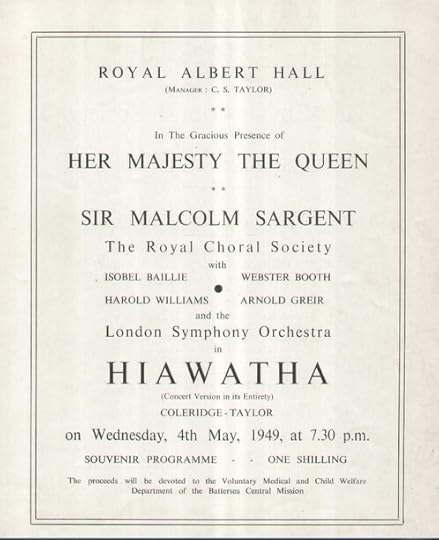

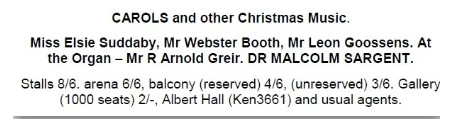

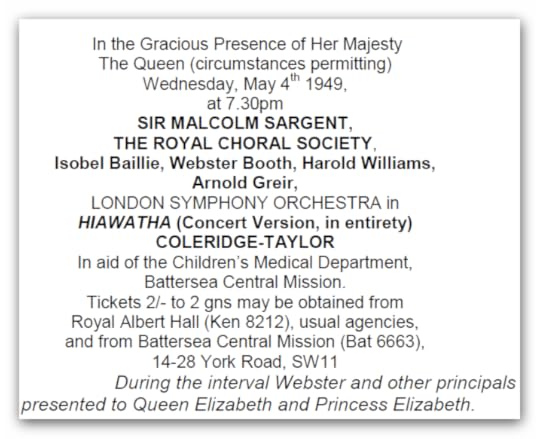

4 May 1949 It was the 21st year of Sir Malcolm’s conductorship of The Royal Choral Society. Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth and her daughter, Princess Elizabeth were present. Webster and other soloists were presented to them in the interval.

Sir Malcolm Sargent’s 21st year as conductor of the Society.

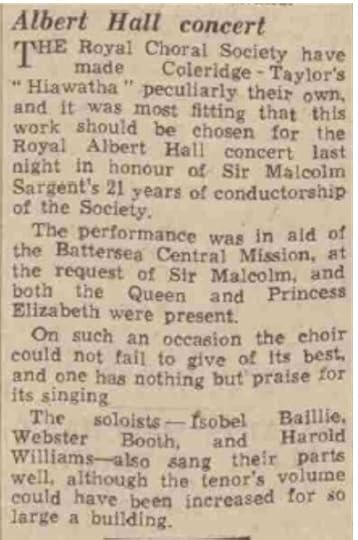

Sir Malcolm Sargent’s 21st year as conductor of the Society.6 May 1949 – Albert Hall Concert. The Royal Choral Society

have made Coleridge-Taylor’s Hiawatha peculiarly their own,

and it was most fitting that this work should be chosen for the

Royal Albert Hall concert last night in honour of Sir Malcolm

Sargent’s 21 years of conductorship of the Society.

The performance was in aid of the Battersea Central

Mission, at the request of Sir Malcolm, and both the Queen

and Princess Elizabeth were present.

On such an occasion the choir could not fail to give

of its best, and one has nothing but praise for its singing.

The soloists – Isobel Baillie, Webster Booth and Harold

Williams – also sang their parts well, although the tenor’s

volume could have been increased for so large a building.

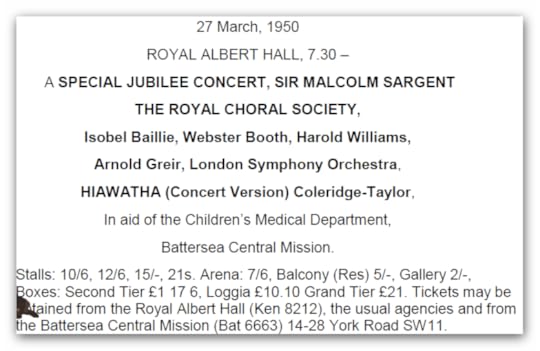

14th March 1950 – Jubilee of Hiawatha.

The Duchess of Kent will attend a special jubilee concert at the Royal Albert Hall on Monday, March 27, at 7.30 p.m. to celebrate the fiftieth

anniversary of the concert, in March, 1900, at which the Royal

Choral Society gave the first complete performance of

.Hiawatha in the concert version by Coleridge-Taylor. Sir

Malcolm Sargent, who has organised the concert, will conduct

the performance, which will be given by the Royal Choral

Society and the London Symphony Orchestra, and the soloists

will be Miss Isobel Baillie, Mr. Webster Booth, Mr. Harold

Williams, and Mr. Arnold Greir. The performance is in aid of

the voluntary medical department of the Battersea Central

Mission. Particulars can be obtained from the superintendent,

Rev. J. A. Thompson. 20. York Road, London, SW II.

March 28 1950 – Albert Hall Jubilee Performance of

Hiawatha. Sir Malcolm Sargent’s annual gift to the children of

the Battersea Central Mission took the form this year of a

performance of Hiawatha, which was sung last night by the

Royal Choral Society at the Albert Hall in the presence of its

president, the Duchess of Kent. The occasion was also the

jubilee of Coleridge-Taylor’s Cantata, which was sung for the

first time with all three parts complete exactly 50 years ago in

this same hall. The work lives by its freshness and

spontaneous sincerity. Some of its harmonic progressions

may raise a smile, or even a frown, but they belong to its

period, and so although they date the work they do not make it

out of date. The solo writing is less open to this mild reproach if reproach it be, than the chorus, and the itching rhythm of the

verse irritates less in the solo than in the choral parts. Yet it is,

of course, the chorus which is protagonist and happily carries

the easy yoke and the light burden of its euphony. The Royal

Choral Society, Mr. Webster Booth (in Onaway Awake), Miss

Isobel Baillie, and Mr. Harold Williams sang it with frank

appreciation of its naive and melodious qualities and without

the least self-consciousness, while Sir Malcolm Sargent was

as whole-hearted about it as he is about the cause to which

last night he wedded it.

This was the last concert before Anne and Webster went to live in South Africa which had Royal associations.

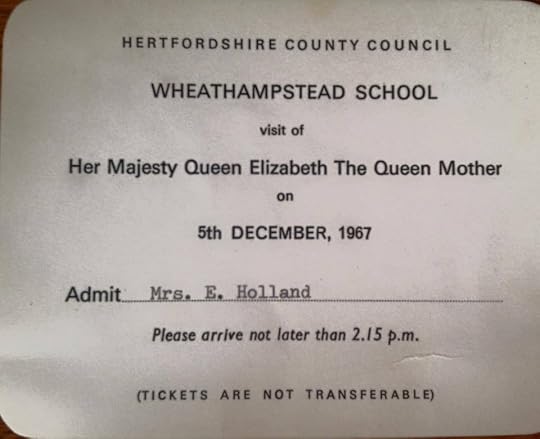

5 December 1967.

In 1967 I was living in Hertfordshire and working as a teacher of music and drama at Wheathampstead Secondary School. The Queen Mother came to the school to open it formally in December of 1967. I had the honour of being presented to her after the performance of the music group in the library, trained by my colleague Vera Brunskill and myself. Sir David Gilliat, the Queen Mother’s Private secretary, came to the school several months before the Queen’s visit to discuss with us what she would talk about.

The choice was Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth. The Queen told me that she had been very fond of their act and it had been Queen Mary’s favourite act. She had chosen Anne and Webster to sing in her special eightieth birthday performance in 1947.

Our performance for the Queen Mother – Cheelo, Cheelo. Vera Brunskill playing the flute, I singing and playing the guitar with the music group of Wheathampstead Secondary School. December 1967.

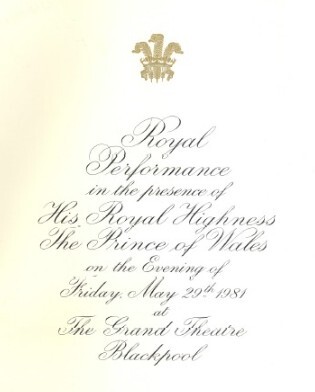

Our performance for the Queen Mother – Cheelo, Cheelo. Vera Brunskill playing the flute, I singing and playing the guitar with the music group of Wheathampstead Secondary School. December 1967.There was to be yet another Royal connection with Anne and Webster after their return to the UK in 1978. On 29 May 1981 they were invited to sing in a Royal Performance in Blackpool in the presence of Prince Charles, now King Charles III.

By this time Webster was far from well but they both went to sing at this performance along with a number of other older performers.

Webster can be seen in the background, bottom left. When he and Anne were presented to Prince Charles he asked them whether they were married!

Webster can be seen in the background, bottom left. When he and Anne were presented to Prince Charles he asked them whether they were married! I know that Princess Alexandra always sent Anne a Christmas card. On the death of the Queen Mother, Anne went into mourning for her, not very long before her own death in October 2003.

After Anne and Webster’s long association with Royalty, I wish King Charles III well in his new role as King of England. Long live the King.

Jean Collen.

August 24, 2022

PLACES ASSOCIATED WITH WEBSTER BOOTH AND ANNE ZIEGLER IN SOUTH AFRICA AND THE UK (1956 – 2003)

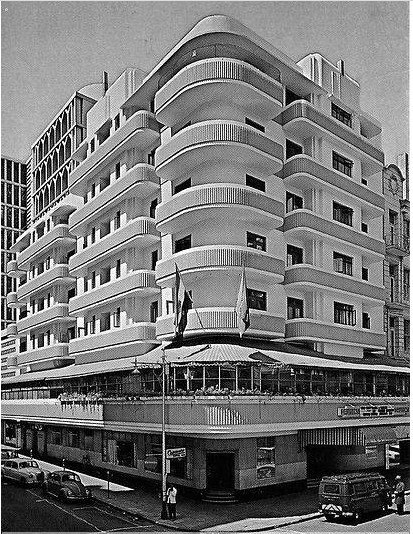

Dawson’s Hotel, President Street, Johannesburg 1972

Dawson’s Hotel, President Street, Johannesburg 1972Webster Booth and Anne Ziegler emigrated to South Africa in July 1956. While they were looking for a suitable home they lived at Dawson’s Hotel, Johannesburg. This photograph shows the hotel at the corner of Von Brandis and President Street. It was considered one of the best hotels in Johannesburg after the Carlton and the Langham hotels in 1956.

Pritchard Street, Johannesburg.

Pritchard Street, Johannesburg. The found a flat at Waverley, Highlands North, just off Louis Botha Avenue, where they lived for several years. They also rented a studio in the centre of the city on the eighth floor of Polliack’s Corner, corner of Eloff and Pritchard Street. It was advertised as the Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth School of Singing and Stagecraft.

The studio was on the eighth floor of Polliack’s Corner in the days when Anne and Webster were there. It had a large balcony facing the OK Bazaars . On the OK Bazaars corner of Eloff and Pritchard Street, little 12-year old boys gathered each morning to play melodious Kwela music, using a penny whistle, and a bass made of a tea-chest. The studio was beyond John Orr’s, the upmarket department store in Pritchard Street. This store was closed many years ago.

Polliack’s Corner, 169 Pritchard Street where Anne and Webster’s studio of Singing and Stagecraft was situated is the building with balconies on the right of this photograph. The view from the studio was the photograph below – a big department store called the OK Bazaars, on the corner of Pritchard and Eloff Streets, Johannesburg. Both these photographs were taken in the fifties when trams were still running in the city.

About 1958 Anne and Webster bought a house at 121 Buckingham Avenue, Craighall Park in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg. Anne said they paid R4000 (£2000) for the house and thought they did very well when they sold it for R8000 (£4000) five years later.

On Wednesday afternoons Webster went to Zoo Lake Bowling Club where he played bowls in “the most beautiful setting in the world”. I was sorry to hear that this bowling club’s lease was not renewed and was closed in February 2011. I had hoped that it may be saved as it had been on this site for over fifty years.

Their second home in Johannesburg was at 31a Second Avenue, Parktown North, where they lived until 1967 when they moved to Knysna in the Cape.

The first house in Knysna was at 4 Azalea Street, Paradise, Knysna. They planned to leave Knysna and move to Port Elizabeth when they discovered their second home in Knysna and stayed on until 1974 at a Settler Cottage at 18 Graham Street.

The Beacon Isle Hotel was built at Plettenberg Bay, the adjoining town to Knysna and attracted visitors from other parts of the country. Anne and Webster sang at its opening around 1970.

The new Crowhurst in Picardy Avenue, Somerset West. Anne is standing next to the cars. (1975) Photo: Dudley Holmes

In 1974 they moved to Somerset West near Cape Town where the cost of living was less than in Knysna, hoping to obtain more work in broadcasting and teaching but there were few pupils and few broadcasting engagements. Webster conducted the Somerset and District Choral Society but he was not offered a fee for doing this! After a time they moved into a maisonette and prepared to return to the United Kingdom in 1978 as Anne’s friend, Babs Wilson-Hill (Marie Thompson) offered to purchase a small bungalow in Penrhyn Bay, Llandudno, North Wales and agreed that they could live there rent-free for the rest of their lives.

Webster died on 21 June 1984 after a long illness at the age of 82. Anne lived on in the bungalow until her death on 13 October 2003 at the age of 93.

The bungalow in Penrhyn Bay.

Jean Collen

24 August 2022

PLACES ASSOCIATED WITH WEBSTER BOOTH AND ANNE ZIEGLER (UK) to 1956.

A member of the Webster Booth-Anne Ziegler Appreciation Group on Facebook suggested that it would be interesting to see various places associated with Webster Booth and Anne Ziegler. Here are places where they stayed during their lifetimes, and photographs of the buildings.

Arbury Road, Nuneaton

Webster Booth’s parents, Edwin Booth and Sarah Webster, were married in 1889. Sarah came from Chilvers Coton, Nuneaton and the address on the wedding certificate was Arbury Road, Nuneaton.

Their first home as a married couple was at 33 Nineveh Road, Handsworth, and it was there that their eldest son, Edgar John Booth was born in 1890.

It is the house with the blue door and is situated round the corner from Soho Road, Handsworth, where Edwin Booth ran a Ladies and Girls hairdressers at 157 Soho Road. The family moved to 157 Soho Road about 1895 and it was there that Webster Booth was born in 1902. It is now the site of a multi-purpose store.

33 Nineveh Road, Handsworth

Webster’s father’s hairdressing shop was originally at 187 Soho Road. It is now the site of Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Below: 157 Soho Road, Handsworth. The family moved from Nineveh Road to premises about the hairdressing shop in the mid 1890s.

Anne Ziegler was born Irene Frances Eastwood of 22 June 1910 at Marmion Road, Sefton Park, Liverpool.

Marmion Road, Sefton Park

When Webster Booth was 9 years old he was accepted as a chorister at Lincoln Cathedral.

Lincoln Cathedral, Lincoln (below)

Collage and photos: Charles S.P. Jenkins

After Webster’s voice broke, he returned home to Handsworth and attended Aston Commercial School which had opened in 1915, with the idea of becoming an accountant like his older brother, Edwin Norman. Edgar Keey, the father of his first wife, Winifred, was the headmaster there.

Webster Booth married Winifred Keey at the Fulham Registry Office in 1924. They made their home at 43 Prospect Road, Moseley with his older brother and family, where their son Keith was born on 12th June 1925. After Webster returned from a tour to Canada with D’Oyly Carte he decided to leave the company to become a freelance singer. He and his family went to London but in 1930 Winifred deserted Webster and they were divorced in 1931.

43 Prospect Road, Moseley, Birmingham (below) Photo: Michael Collen

43 Prospect Road, Moseley. Photo: Michael Collen.

43 Prospect Road, Moseley. Photo: Michael Collen.

Webster Booth left the D’Oyly Carte after the tour of Canada, changed his name from Leslie W. Booth, as he had been known in the D’oyly Carte Company, to Webster Booth and went to live in London to try his luck as a freelance singer.

The family lived in Streatham Hill, the old home of Tom Howell, leader of the Opieros Concert Party with whom he sang for several seasons, and – at the time of his divorce from Winifred Keey – he was living in Biggin Hill.

Streatham Hill (1927 on)

Biggin Hill, 1931 (below)

5 Crescent Court, Golders Green Crescent NW11

In October 1932 Webster Booth married his second wife, Dorothy Annie Alice Prior, stage name Paddy Prior. Paddy Prior was a soubrette, dancer, mezzo soprano and comedienne who had been on the stage since her late teens. She was born in Chandos Road, Fulham on 4 December 1904. During their marriage – 1932-1938 they lived at 5 Crescent Court, Golders Green Crescent.

In 1934 Irené Frances Eastwood moved to London and changed her name to Anne Ziegler to appear as the top voice in the octet of By Appointment, starring Maggie Teyte. She lived at 72 Lauderdale Mansions, Lauderdale Road, Maida Vale.

Lauderdale Mansions, Maida Vale.

Lauderdale Mansions, Maida Vale.Anne and Webster were married on 5 November 1938, first at Paddington Registry Office, then had their wedding blessed in a special service for divorced persons at St Ethelburga’s Church, Bishopsgate.

Photo: Charles S.P Jenkins

Anne and Webster lived at the same address before and after his divorce from Paddy Prior in 1938 and in 1939 they moved into a bigger flat in the same building.

In 1941 they purchased a big house with a big garden from the theatrical couple, Ernest Butcher and Muriel George. This house was called Crowhurst at 98 Torrington Park, Friern Barnet N12.

Crowhurst, 98 Torrington Park, Friern Barnet N12.

Crowhurst, 98 Torrington Park, Friern Barnet N12.

Anne and Webster in the garden at Crowhurst, early 1940s.

Photos of Crowhurst today: Pamela Davies

Crowhurst sitting room today.

When they returned from their concert tour to New Zealand, Australia and South Africa in 1948, they realised that Crowhurst was too big for them to manage at a time when it was difficult to find suitable domestic staff. They decided to buy a smaller house at Frognal Cottage, 102 Frognal, Hampstead NW3.

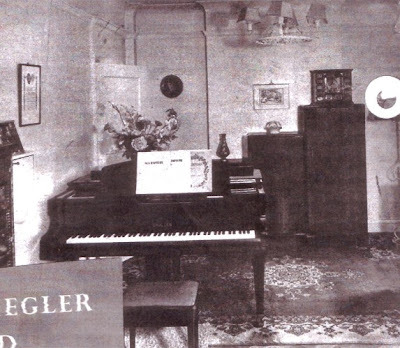

Listening to one of their new recordings in the sitting room at Frognal Cottage, with Smokey (1950)

Photos of Frognal Cottage today: Pamela Davies.

They sold Frognal Cottage in 1952 and moved to a house nearby at 9 Ellerdale Road, Hampstead, where they remained until they left to settle in South Africa in 1956.

9 Ellerdale Road, Hampstead.

I have created a similar post of the South African and UK residences where Anne and Webster lived from 1956 to 2003.

Jean Collen 24 August 2020

August 19, 2022

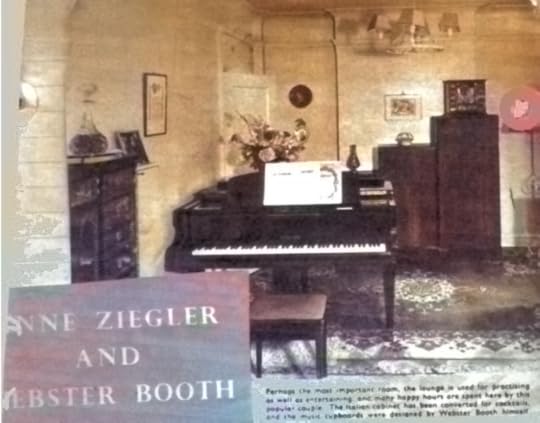

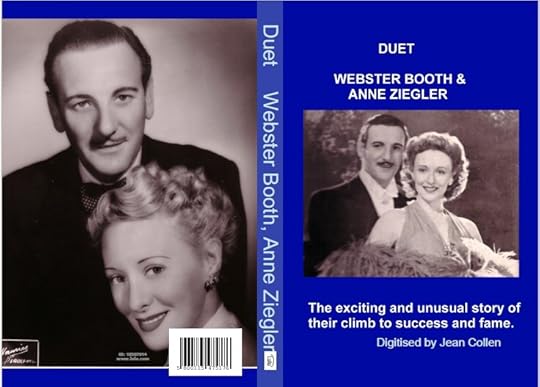

JOHN BULL MAGAZINE – 1O MAY 1952.

John Bull, 10 May 1952

10 May 1952 – John Bull article by Elkaw Allan.

Listening to their latest recording at home in Frognal Cottage.

Listening to their latest recording at home in Frognal Cottage.When Webster Booth arrived at the television studios to sing Silent Night with the Luton Girls’ Choir, he discovered to his horror that they had rehearsed it in English, though he had planned to sing the original German version. Hurriedly he learned the English words and, to make sure, had them written on a large piece of paper and hung above the camera. Just as the song was starting the paper blew away, and he was left with only an imperfect memory of the words. His wife, Anne Ziegler, crept up to the camera, stood next to it with the music, and mouthed the words to him.

So perfectly did they work together that viewers never noticed anything amiss. This close partnership has existed for the last twelve years, ever since their marriage and joint debut. Both have continued their separate careers as tenor and soprano, but it is as Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth, Singing the Songs you Love, that they are best known.

Some musicians deplore the syrupy sweetness of their repertoire and their flamboyant arrangements, but they are in constant demand at music halls and Sunday concerts, earning from £200 to £400 a week; the 500 gramophone records they have made sell in hundreds of thousands; they keep a Daimler and three servants; and their popularity extends from the working-class housewife who has named her children Anne, Webster, Leslie (Booth’s first name), and Keith (his son’s name) to Queen Mary, who picked out their act as a favourite she wished to hear in her eightieth birthday BBC programme.

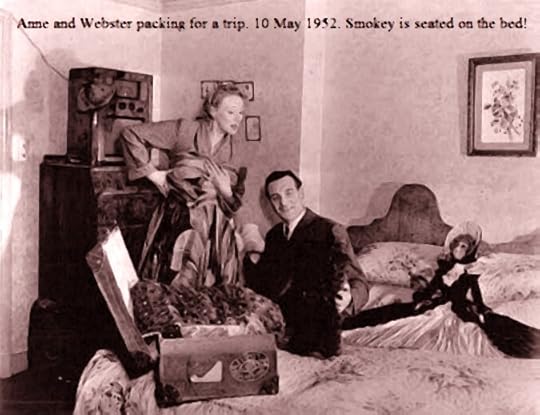

Anne and Webster pack for a concert tour. Smokey, their Cairn Terrier, is on the bed!

Anne and Webster pack for a concert tour. Smokey, their Cairn Terrier, is on the bed!On the stage they are the handsome, romantic couple who sing duets about love and memories, personifying the timeless happy-ever-after world of the fairy tales. At home, they resume a married life much more like those of their audiences. He is a tall, kindly fifty-year-old, who cheerfully calls his large-sized nose a “conk” and can never make up his mind whether or not to keep a moustache. She is shrewd, gentle and house-proud, likes making her own clothes, and is successfully keeping middle age at bay. She is sensitive about her exact age – forty-one – and it is inked out of articles stuck in her Press-cuttings book.

Sometimes they bicker, like every married couple, “But when we get on the stage we forget all our differences. The best way to make up any husband-and-wife quarrel is to do some work together,” says Booth, in a voice which has never completely lost its Birmingham accent.

Their approach to their work is light-hearted. “We’ve sung most of our songs so many times that it’s practically impossible to make a mistake, and Boo sometimes tries to make me dry up, just for fun.” says Anne, whom “Boo” calls “Lottie.” He whispers awful things under his breath, won’t let go of my hand, makes faces at me, and accidentally-on purpose flips me across the face when he’s gesturing. And I have to keep going as though nothing was wrong.”

The Chappell Grand Piano in the music room at Frognal Cottage, Frognal.

The Chappell Grand Piano in the music room at Frognal Cottage, Frognal.Their “Good Luck” Rings

But to sing sentimental songs successfully, it is necessary to be sentimental oneself, and the Booths, whose home is full of pets, conscientiously wear “good luck” rings they gave each other early in their acquaintance.

They met in 1934, when Booth, a recognised singer, was given the part of Faust in the first British colour film ever made. Two hundred girls applied to play Marguerite; among them was a slim blonde who had come from Liverpool three months before to join a musical comedy. Born Irené Eastwood, she had changed her surname to that of her German grandmother, Ziegler, and put her favourite Anne in front. Her looks and her voice got her the job. She fell in love with the leading man, and into a divorce suit, for he was married already.

Until then, his career had been solid without being spectacular. He had sung at concert parties with Arthur Askey, but was discouraged when an old woman got up after a show and loudly complained to her companion: “Yon singer’s not bad when ‘e croons, but when ‘e sings loud ‘e’s ‘orrible.”

Booth’s father, a hairdresser, was relieved when his nine-year-old son won a place in Lincoln Cathedral choir, for it meant a free education. On of the first rules laid down for him there was against going to football matches, in case he injured his voice shouting. “This was a blow for me, because I was mad on football. I played goalie, and when I was fourteen, the Aston Villa coach saw me and offered me a place in the Villa Colts. I couldn’t decide whether to accept, and played truant from my singing lesson to watch them again and make up my mind. Unfortunately – as I thought then – I was spotted at the game and got such a thrashing I dared not take the offer.”

The choirmaster’s methods were none too gentle. He used to push a broken baton into the children’s mouths to force them wide open and push their tongues down. The psychological scar has remained with Booth, and even today, he is unable to have his throat examined, the touch of anything stiff on his tongue making him violently sick.

This was highly inconvenient when, in the opening scene on the first night of The Vagabond King, an actor duelling with him over-enthusiastically hit him across the throat. He was almost knocked out. By the last curtain he could hardly raise a sound. A specialist was sent for, but because of Booth’s inability to allow his larynx to be examined, nothing could be done.

“He kept trying to look down, but I almost bit his fingers off. In the end he just packed his bag and walked out.” It was a week before Booth could sing again.

Audition Was a Failure

Anne was going to be a dancer, but her instep dropped when she was thirteen, and she studied singing instead. When the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company came to Liverpool, she was granted an audition. But the night before, she caught ‘flu and the audition was a miserable failure. In the chorus was Webster Booth, who had become an accountant, but who had gone back to singing later. They did not meet then, however.

“I suppose my disappointment was Fate’s way of paying me back for the fiendish child I had been,” says Anne. “I had always refused to do any work at school, and at home I played such tricks as pretending to faint and clutching the tablecloth as I fell to the ground, bringing all the tea-things with me. I was such a wicked child that my mother kept a riding whip on the dining table between my equally naughty brother and me, to thrash us when we misbehaved.”

The Booth’s schedule is sometimes crammed to bursting point. Recently, in Glasgow, they finished a concert at nine-twenty on Saturday evening and while Anne caught an express to London, Webster caught the train to Preston, in Lancashire, where he had left his car. He arrived there before dawn, slept for two hours and drove nearly 100 miles across country to Ashby-de-la-Zouch for a concert on Sunday afternoon. Meanwhile, in London, Anne packed some bags, and went to Luton to sing in Tom Jones. After his concert, Webster drove to London, and they met in time to sing at the Albert Hall on Sunday evening. After that, they hurried down to Eastbourne, where they started a week’s variety on Monday evening.

Trooped Into Bedroom

“The only way we can carry on is to sleep in the afternoon whenever we can,” explains Anne. This, however, had an awkward consequence when they sang for the British Legion in Motherwell. It was afternoon by the time got there, and they had eaten lunch. But the Legion had arranged a banquet for them, which they attended as briefly as possible before retiring to an adjoining room to rest. “Unfortunately, the people at the luncheon mistook our room for the cloakroom,” says Anne, “and when they finished lunch they all trooped into our bedroom looking for their coats. I’ve never been so embarrassed in my life.”

She takes a trunkful of crinolines wherever she goes. They have become her trade mark, and one of them had 100 yards of mauve and pink net in it. She has nine in her wardrobe, including one made ten years ago and worn so often that she dare not appear in it again. “People would say it was the only one I had.” She keeps a diary of every engagement, with a not of each dress, so that she does not repeat herself next time she sings at the same place. The crinolines cost from 85 to 240 guineas each.

Her husband wears out three dress suits a year. “It’s the packing that ruins them.” On the maiden voyage of Imperial Star to Australia, water flooded the hold, and all his dress shirts, ties and waistcoats were soaked and dyed by the colours near them. Booth collected all the disinfectant in the ship and soaked them in it. The captain sent a radio message to Teneriffe, the next port, and a laundry was standing by to wash them. This restored their looks, but six weeks later, as he was dressing for a concert, it disintegrated. The next one did the same right through his stock. He had to borrow a shirt before he could sing.

Although they have received 250 guineas for nine minutes’ work – when they travelled to Perth for an all star broadcast cabaret to launch an hotel – their regular fee is £150 for a concert. Cabaret appearances are usually worth £100, and they get a guaranteed minimum of £300 a week on the halls. On top of this are royalties for their gramophone records, which have been as much as £1,000 a year. “But everything costs a lot,” points out ex-accountant Booth. “Our house and secretary and servants run into £50 every week, and our accompanist gets up to £30 a week, plus expenses. And we still have the agent and the Income Tax man.

With Smokey at Frognal Cottage.

With Smokey at Frognal Cottage. For their fees they have to perform so many songs which, however pleasant for the first few times to hear and to sing, become almost sickening after a thousand airings. “Sometimes I feel I’ll go mad if I have to sing We’ll Gather Lilacs or The Keys of Heaven just once more,” confesses Anne. “But at every concert we are bound to get several requests for them and we are servants of the public.”

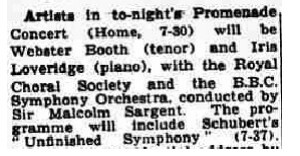

Sir Henry’s Question

To escape the monotony they have made several forays into grand opera and both have sung in oratorio. But on the one occasion he sang at a Promenade Concert, Booth felt he was insulted by Sir Henry Wood. He and Parry Jones had been asked to sing the tenor parts in Beethoven’s Choral Fantasia. and he arrived before Jones. Sir Henry met him and asked, before the whole BBC Chorus, “Are you the stand-in for Parry Jones?” He was so offended that he has stubbornly refused to sing again at the Proms although Sir Henry has since died. “It’s very naughty of him,” says Anne.

As for the future they talk – wistfully, but without conviction – of retiring and settling down in the country. Television is opening up a new field for them and they give it greater attention than the immediate payment warrants.

“Sometimes when we’re feeling particularly pleased with ourselves, we like to think that everyone in Britain has been made a little happier just for a moment sometime by our singing. After all, there’s no harm in being sentimental, is there?”

Femina and Women’s Life, 28 January 1965.

I am not sure of the origins of Femina and Women’s Life – it may have been a supplement to a newspaper at the time. It should not be confused with the Women’s magazine, Femina, which appeared in the 1980s. The photographs are taken from a rather over-the-top article, written by Fiona Fraser and Bill Brewer.

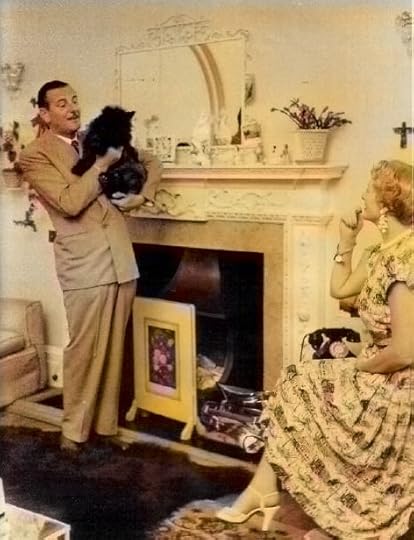

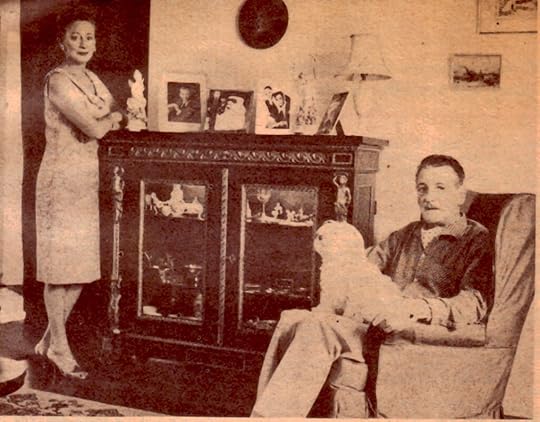

Husband-and-wife team Fiona Fraser and Bill Brewer visit the Booths of Parktown North.

Theatre Couples at Home – 8

“We met Princess Alexandra and she signed the photograph for us.”

“We met Princess Alexandra and she signed the photograph for us.”On a rural corner in Parktown North, there is a discreetly wood-fenced corner, over the top of which can just be glimpsed the roof of a charming home. By the wicker gate on an upturned stone is written the address, in which paint, probably by Leslie – otherwise known all over the world, as Webster Booth. We will call him Leslie so there is no confusion!

Leslie Webster Booth. Lyric tenor, Star of musicals, light opera, variety. In great demand for oratorio. Actor, well-known radio personality, film actor, writer, teacher of singing, film star of “The Laughing Lady”. “Waltz Time”, “The Robber Symphony”. Royal Command performer. Dog lover.

Leslie Webster Booth. Lyric tenor, Star of musicals, light opera, variety. In great demand for oratorio. Actor, well-known radio personality, film actor, writer, teacher of singing, film star of “The Laughing Lady”. “Waltz Time”, “The Robber Symphony”. Royal Command performer. Dog lover. Anne Ziegler, lyric soprano, Principal Boy, actress, recording and TV star with her partner-husband. Operettas, musicals, producer. Keen gardener, teacher of singing, Royal Command performer.

Anne Ziegler, lyric soprano, Principal Boy, actress, recording and TV star with her partner-husband. Operettas, musicals, producer. Keen gardener, teacher of singing, Royal Command performer.“You’d never guess that one of the best-known singing acts in the world lived here,” said Fiona to her daughter, Tandi, as Bill heaved the tape recorder from the back seat.

The Brewer trio walked through the wooden gate into a sunken garden, silky with tenderly-tended lawn and disciplined flower beds. A long, lean Leslie left manuscript, records and stop watch on the patio lounge, and came to greet them.

The slim and elegant Anne put down her seething hosepipe reluctantly, signalled the assistant gardener to turn the water off, stripped off her gardening gloves, and joined her guests.

“Coffee or tea?” she asked with Lancashire forthrightness.

Leslie led the way into the sweet coolness of their home. Tandi and her parents were fascinated by the warm sheen of the old and beautiful wood of various pieces of furniture, especially the bric-a-brac cabinet with the tiny treasures fro all over the world on its shelves.

Leslie moved a rocking-chair gently, disclosing a shaggy small dog. “I think you’ll find a plug for the recorder behind the black cat,” he said.

The Brewers regarded the large, somnolent cat with caution. They’d visited quite a few establishments during these interviews.

The coffee and milk were poured out of a lovely pair of silver antique jugs. The Brewer eyes shone enviously. Anne explained, “A present from Marion Rawicz of Rawicz and Landauer.”

The Brewer eyebrows made into interrogation marks. Anne explained, “During the war, they were aliens, and afterwards, Marion wanted to build a house in Hampstead -”

Bill was enchanted. “We used to have a cottage there,” he butted in. “Holly Hill – last cottage on the right-hand side. The only one with a garage. Did you know it?”

“No,” said Anne evenly. “And Marion couldn’t get permission. You had to have a permit for these things. So I went and was rather charming to the Hampstead Town Clerk – “

“We gave a concert for him,” Leslie entered into the conversation. Anne seemed rather relieved. “So we did!” she said. “So we had him with his back to the wall after the concert, and we exerted all our charms – “

“Did you?” breathed Bill.

“She did!” agreed the amiable Leslie.

Anne carried on. “anyhow, through all this, I got a permit for Marion to build his home, which he’s still living in.

“One day, he called on us with a rather curious parcel under his arm. (She now used such a good mittel-European accent, that the Brewers wondered why she didn’t do more radio plays.) “Undt’ee open it, undt say, ‘Anne, is only a leetle zing to say sank you for all vot you ‘aver done.’

“So, enjoy your coffee, because it comes from a happy memory.”

Eton Collar and All

Fiona started. “Let’s have some background stuff, please, Leslie. You started in opera, I believe?”

Leslie shook his head. “I started as a choirboy,” he said. “I was a choirboy at Lincoln Cathedral when I was seven.”

“Thorough little stinker he was, too!” said Anne.

“Yes, I was a shocking little horror in Eton collar and all that stuff! My voice broke when I was thirteen and I went to a commercial school to be trained as an accountant. I didn’t like that much, so I joined D’Oyly Carte – the Gilbert and Sullivan Opera Company – in the chorus. I was twenty-one when I joined the company, and after being promoted to various parts, I was with them on their first Canadian tour.

“When I returned, I realized there wasn’t much chance of getting anywhere with the D’Oyly-Cartes, so I left and started on concerts. I met Sargent – “

“Sir Malcolm?” breathed Fiona, impressed, looking at a signed photograph of that carnationed beau of conductors.

Leslie carried on with the background. “Yes. He put me into oratorio, and from that I went into grand opera.”

Bill leaped in. “What lead roles did you sing?”

“I didn’t,” Leslie said, rather obscurely. “I was one of the priests in The Magic Flute in the 1938 season with Richard Tauber. The conductor was Beecham. Then I did the tenor part in Rosenkavelier at Covent Garden and Sadlers Wells. Of course, by then, I was recording – “

“And you’d met me, of course,” Anne said, quite gently.

Leslie’s short period of accountancy must have made its impact, because he remembered. “Nineteen-thirty-four was when I met Anne,” he said with certain satisfaction

“Thirty years this month, I’ve put up with this monster,” Anne stated, without rancour.

Fiona looked at the glamorous Anne, and said, “Of course, you were very, very young at the time, weren’t you?”

Anne wasn’t the slightest bit perturbed. “Not all that young,” she said quite happily.

Opening night of Sextet, 1957.

Opening night of Sextet, 1957.Leslie decided to confess all. “Well, she was younger than me anyway,” he said. “Now let me see – I was playing Faust in the first colour film of that opera, and who was Marguerite but little Annie Ziegler! So that’s how we met. And then we started singing together – “

“And we got married,” Anne said. Then added, rather inconsequently, “Did you know Leslie was married three times?”

Leslie seemed unimpressed. “So what?” he asked.

Bill asked, “Any family?”

Leslie answered. “Yes, I’ve got one son, who’s a farmer in England.”

Anne added, “And a granddaughter, whom we haven’t seen yet, alas.”

Fiona brought them back to their careers. “When did you start singing together?”

Anne answered, “We were married in 1938, Bonfire night – November the Fifth!”

“Fireworks when you married?” murmured Bill.

“And ever since!” came, involuntarily, from Leslie.

Anne agreed sunnily. “Yes! And we started to get well-known when Julius Darewski put us on the map in variety in 1940. We opened at the Hippodrome, Manchester, and we concentrated on working together, and we did, in things like The Vagabond King.”

Fiona became excited. “I saw you in that, and fell in love with Leslie on the spot,” she said with fervour.

Leslie accepted her homage gracefully. “We did recordings, musicals, films together.”

The factual Fiona, of course, wanted to know, “How many records have you made?”

Leslie considered. “I suppose about a hundred and fifty duets, and two or three hundred solos.”

Fiona continued, “A lot of your records were very big sellers individually, weren’t they?”

Leslie’s accountancy course appeared to have failed him. “Yes. We’ll Gather Lilacs – I don’t know how many that sold, but it’s still selling. And Macushla and English Rose – they sold thousands, but I don’t know how many. Anyway, we still get money trickling in from all over the world.

“It’s not like it was, of course, because they’re not making 78s any more, but they’ve put out some re-issues on 45s, and they’re selling very well.” He considered the financial trickle, and said in heartfelt tones, “Thank heaven!”

‘Pretty Little Voice’

Bill considered it was time to learn something about Anne. He said, “Tell us about yourself before you met Leslie.”

Anne did so. “Actually, I wanted to be a pianist. I was a monster at school, and my parents were told that it wasn’t worthwhile my carrying on because I wasn’t interested in anything except music. Oh, I wasn’t expelled or anything, but I was taken away, and I continued with languages and piano.

“Then the organist at our church discovered that I had a ‘pretty little voice’, so I dropped the piano, because I realized that I’d only be adequate as a piano-player.

“I started training as a singer. I sang in a choir, then I sang in the chorus of operas, and my music teacher took me around for odd concerts, as a sort of star pupil.

“Eventually I had to find something to do, because my father lost all his money in the cotton market, and I wanted to support myself.

“So I went to London, and auditioned for the chorus of a musical with Maggie Teyte. That was a complete flop – lasted three weeks and folded up. I had two alternatives – get work in London, or go home.

“A friend introduced me to the woman who used to book the singers for the Lyons Corner House, the Regent Palace and the Strand Palace (where Leslie worked many years before), and that kept me going for three months.”

Fiona had a thought. “Have you always been Anne Ziegler?” she asked.

“No. My name was Irené Eastwood.” She slipped into an authentic North Country accent. “Reet good Lancashire name, Eastwood! Irené, in Greek, means ‘Peace’.”

Leslie said, “That’ll be the day!”

Anne took that in her stride. “I had to change my name when I went into the chorus, because my name had to go into the programme. I’ve always loved the name ‘Anne’, and I thought, ‘Now what do I do about my surname?’

“So I went through the Liverpool directory, and the last name in the book belonged to my father’s cousin who had emigrated from Germany about fiver hundred years earlier, and had drifted from farming in Scotland to farming in Cheshire. So there it was, A to Z – Anne Ziegler!

“And I was lucky, because during the 1930s, Continental singers with foreign names were very popular, and people thought I was Continental! I didn’t trade on it, but it did help!”

Bill commented, “Once Ziegler and Booth got together they travelled the world?”

Leslie said, “Well the only trip we haven’t made is from New Zealand to Vancouver!”

‘Best Country of All!’

Fiona was impressed, naturally. “Having toured the world, what made you decide to settle in South Africa?” she asked.

There was an astonished pause, as the Booths gazed at the Brewers. Then there was a machine-gun barrage of answers.

“It’s the best country of all.”

“Definitely.”

“The sun…”

“The way of living…”

“The spaciousness…”

Bill was intrigued. “Tell us more.”

Leslie did so. “I certainly will! We came out here on a world tour in 1948, on our way to Australia and New Zealand. Someone told us to contact Gladys Dixon at the SABC. So we cabled from the ship to say we were arriving in Cape Town, and had three weeks before we left Durban.

“She cabled back that she had arranged for us to do two broadcasts from Durban, two from Cape Town and two from Johannesburg. Then we rejoined the ship and did our tour.

“Well, when we got home, we talked things over. We didn’t like America or Australia much. We did like New Zealand, but it’s too remote, and the only decent place was South Africa, which we adored.

“Anyway, we didn’t do anything about it, until 1955, when we had a cable from Cape Town Municipality, asking us to do a tour with the Cape Town Orchestra. So we came out, did the tour, and then Percy Tucker of Show Service, asked us to come out again the following January in ’56 and do another tour. We came out and stayed until May.

“Then, when we went home, we found that the public taste for music had radically changed. So we said, ‘What’s there for us – here?’”

Anne said, “We could see the warning light. We could sense the change in entertainment form that was to come.”

Leslie nodded. “Yes. Rock ‘n Roll and all that twangy stuff was on its way. So I said, ‘To blazes with this! I’m too old to start learning to play a guitar. Let’s go back to South Africa!’ We came back in July ’56, and we haven’t been back to England since.”

August 16, 2022

Death of Ena Lambrechts (13 August 2022).

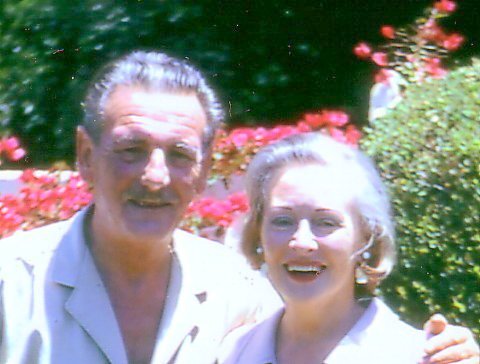

Ena Lambrechts and Webster Booth in an extract from Elijah, Knysna, 1970.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Us8NW0ip4IPh1yq6BgMhlW7tSwrtpaAQ/view?usp=sharing

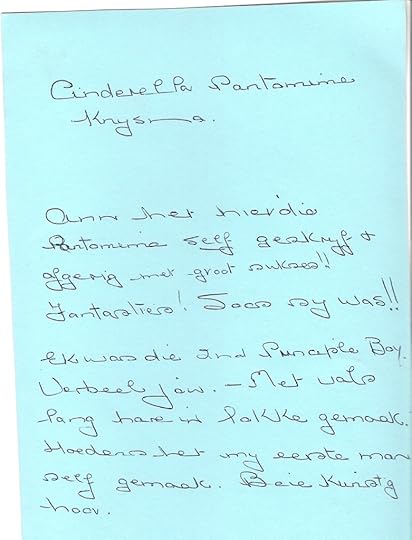

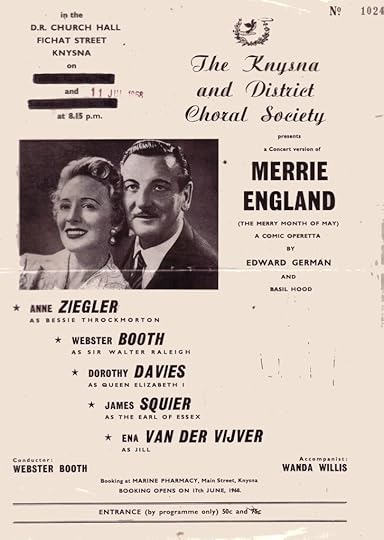

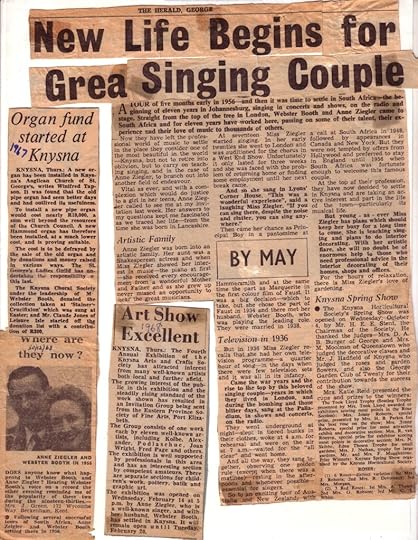

I was sorry to hear of the sudden death of Ena Lambrechts yesterday. She studied with Anne and Webster when they lived in Knysna in the Western Cape, and took part in a number of the performances they put on there with the Knysna and District Choral Society, ranging from excerpts from “Elijah” to pantomimes where she was “second” principal boy in “Cinderella” in the late 1960s/early 1970s.

Ena and Anne in “Cinderella” (late sixties/early seventies)

Ena and Anne in “Cinderella” (late sixties/early seventies) Ena’s message to me in Afrikaans.

Ena’s message to me in Afrikaans. This account of Ena’s work with the Booths appeared in my book,

ENA Lambrechts (formerly van der Vyver, Geldenhuys) OF STRAND, WESTERN CAPE, WRITES:

At the age of fifteen, I sang in the Knysna Eisteddfod. Without any previous singing training, I won the open section against trained singers like Maria Stander (whom Anne and Webster also knew) and received a gold medal. I also won the gold medal in my age group (15-18 year olds). This was without any training. (So naive!)

My family gave me no further encouragement. I actually didn’t realise I had something that could be developed, probably because I never was one to let such things go to my head (and even today, I’m still like that).

Anne and Webster in their garden in Knysna. Photo: Dudley Holmes.

Anne and Webster in their garden in Knysna. Photo: Dudley Holmes.When Anne and Webster came to Knysna our paths crossed. That was fantastic! At the choral society, I got to know them both as true friends who took an interest in me and my voice. I made use of this opportunity, and so had the chance to achieve something after all. During my time with them, I became, like Dudley Holmes, a child in their home. I will always remember Anne’s laugh. And I will never forget the late Sunday afternoons. “Dad” would pour the whisky, and I would sit on the carpet with Squillie and Lemon.

Squillie (Silva) and Spinach. Lemon died in 1972.

Squillie (Silva) and Spinach. Lemon died in 1972.When I was in London, Anne and Webster also gave me the opportunity to visit the BBC, where I met the affable Eric Robinson.

Back in Knysna, Anne and Webster took me into their capable hands and gave me a thorough training. From them I learned to develop full self-confidence in everything I did. My stage performances and rapport with audiences improved.

It was a great honour for me to share the stage with Anne and Webster, as a soloist as well as a duettist with each of them. Words can’t describe how honoured I was to achieve that in my life. At the same time, I was very disappointed that I went through their hands so late in my life. Because, in addition to my voice training, another world opened up to me.

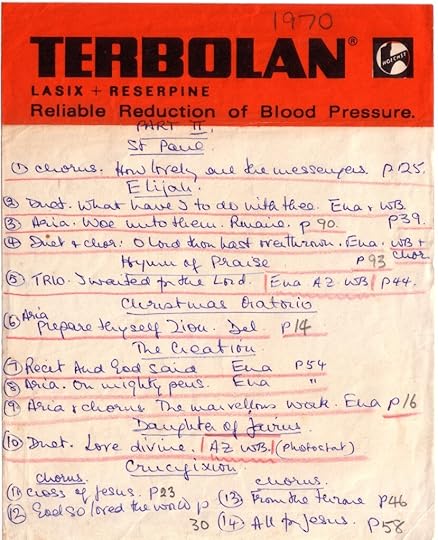

Ena sang solos from Messiah, Creation, Elijah and various other oratorios with the Knysna and District Choral society in 1970. This is part 2 of a full programme in Anne’s writing.

Ena sang solos from Messiah, Creation, Elijah and various other oratorios with the Knysna and District Choral society in 1970. This is part 2 of a full programme in Anne’s writing.I played important roles in their pantomimes, such as second principal boy in Cinderella, in Trial by Jury, as a soloist in choral performances and other productions, too numerous to mention.

1968. Merrie England.

1968. Merrie England. But in all the beautiful and happy days on the stage with Anne and Webster, there was spitefulness too. It was something I found very difficult to accept, but Dad coped with it in a completely different way from Anne and always prepared me for such things. I will always remain grateful to them for that. We, all three of us, simply came out stronger on the other side. I could see them, as professionals, rising above people who would never reach that level.

After my retirement, I was in a position to join a big choir, The Tygerberg City Choir in Belville, under the direction of a most competent choir leader and coach, Edward Atkinson.

The auditions had been going on for a week when the day of my audition arrived. The atmosphere was very tense. My time came nearer, but I walked in very calmly, and Edward was very friendly. He could see I was calm and full of self-confidence. I could answer all his questions clearly: Yes, especially my training and background with Anne and Webster. I could see that Edward was very satisfied.

Before I left, he told me that I had been accepted and that he would use me. I was, of course, told not to say anything, because the results would only be made known the following week. Believe me, to keep this from all the others who were still waiting to go through it all was difficult. I found the choral singing with big orchestras fantastic.

As far as the learning was concerned, to my surprise I surpassed myself. After two years, I had to resign from the choir because of the circumstances here in the Cape. It had become very dangerous to drive to the rehearsals alone at night. Car hijackings, abductions, etc. were rife, and I had to make a choice. My husband, Pieter, was also struck down with cancer, and I had to make a decision. I am glad that I was able to be part of such a large and wonderful choir under the direction of such a gifted coach. Both Edward and my husband have since died.

Nowadays I sing in the Cantando Choir here in the Strand. It’s not a big choir, but the spirit between us is very good, and there are some lovely voices. (At the end of March 2007, I was appointed as the choir soloist!)

I always try to keep up Anne and Webster’s good name with my performances, as a good advertisement for their part in my life and in my singing – and a positive outlook on life and in everything I tackle. Today I can look the world proudly in the eye, because of the part they played in my life!

After so many years, I still shed a solitary tear when I think back on them with respect.

Thank you for this opportunity to honour them. They transformed my simple life into a fantastic experience.

May Ena rest in peace and may her friends and family be comforted at this sad time.

I discovered several of these cuttings in the Port Elizabeth Herald when I was returning to South Africa onboard the SA Oranje.

1968 August.

1968 August. Jean Collen 16 August, 2022.

May 15, 2022

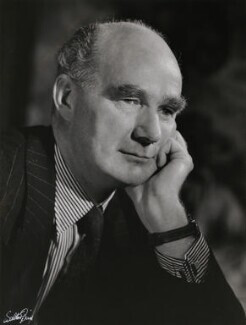

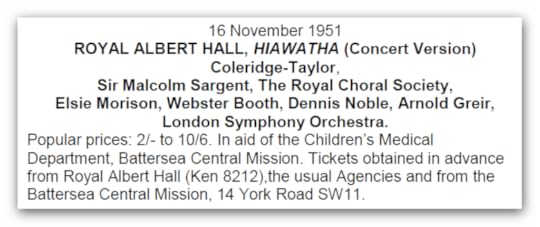

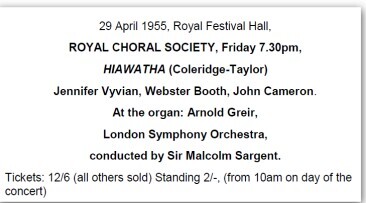

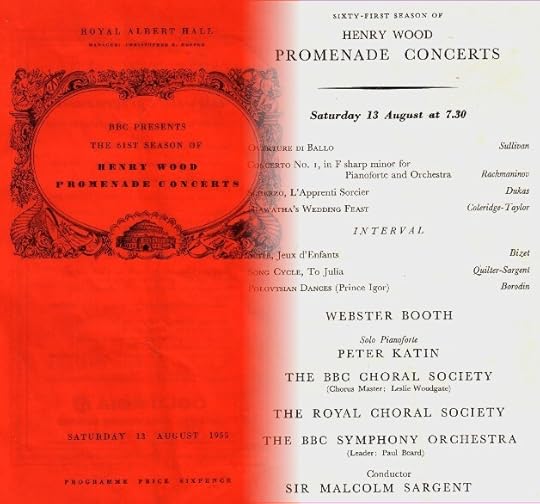

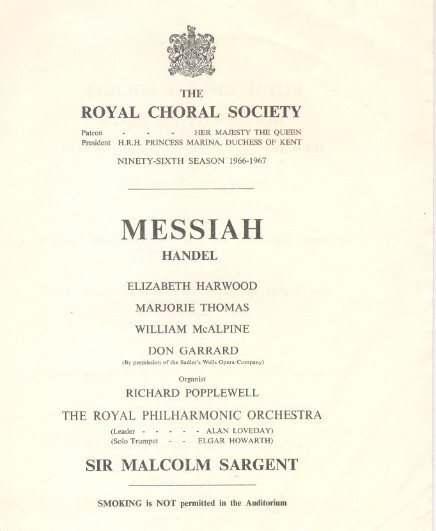

WEBSTER BOOTH’S ASSOCIATION WITH THE ROYAL CHORAL SOCIETY AND SIR MALCOLM SARGENT.

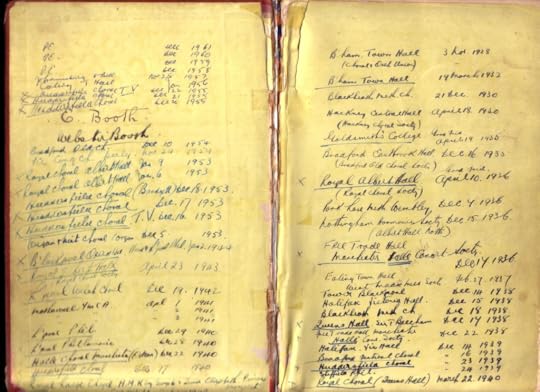

Front page of Webster’s score of Messiah.

Front page of Webster’s score of Messiah. 2022 is the hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Royal Choral Society. Webster Booth was associated with the Society from the early 1930s until 1955 when Malcolm Sargent was the conductor of the Society. He had conducted the D’oyly Carte Opera Company in 1926 when Webster was a chorister there and advised him not to consider an operatic career if he did not have a private income to supplement the small salary offered to opera singers. On the advice of Dr Sargent he concentrated on oratorio and undertook a variety of lighter engagements, ranging from concert work, cabaret and musical comedy to recording and radio work.

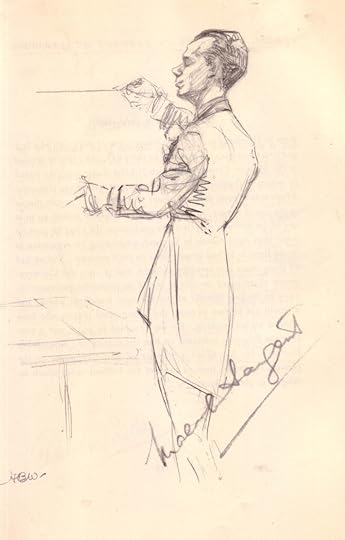

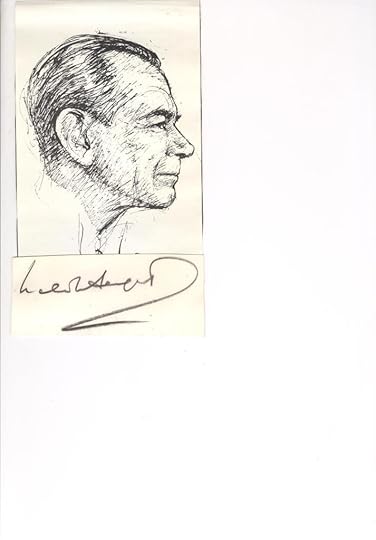

Sketch of Sir Malcolm by Hilda Wiener.

Sketch of Sir Malcolm by Hilda Wiener.Despite Sargent’s advice that he should not aspire to Grand Opera, Sargent was obviously impressed with Webster’s voice and saw to it that he was engaged with the Royal Choral Society on many occasions.

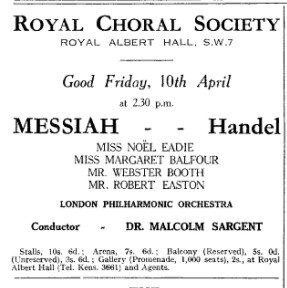

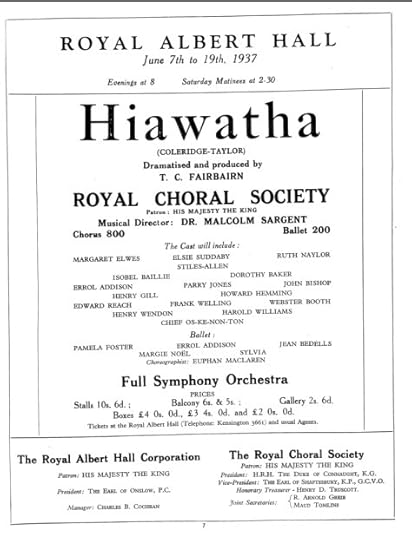

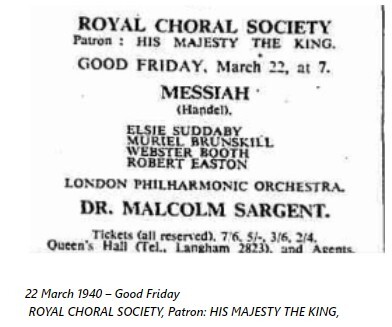

The first occasion was at the prestigious Good Friday Messiah at the Royal Albert Hall on 10 April 1936.

.

Webster Booth

Webster Booth

The Times crit read as follows:

The annual Good Friday performance of the

Messiah was given yesterday at the Albert Hall by the

Royal Choral Society under their regular conductor, Dr

Malcolm Sargent. It followed the customary lines, being

given in the usual arrangement as regards orchestral

accompaniment and with the usual cuts, except that the

tenor soloist, Mr Webster Booth, following the recent

precedent, was allowed the aria Thou Shalt Break Them

in Part II. He strove to make his solos vivid, and in doing

so employed considerable variety of vocal colour. Miss

Noel Eadie phrased I Know That My Redeemer Liveth

very spaciously, which is not easy to do, and succeeded

in sustaining its lines at a slow tempo. The contralto

soloist was Miss Margaret Balfour.

Of the Messiah solos, those assigned by Handel

to the bass singers are the best, and they found an

excellent exponent in Mr Robert Easton. His voice is just

about the right weight and composition for them, though