Anna Geiger's Blog, page 24

November 28, 2021

Introducing a new series: Reacting to Fountas and Pinnell

TRT Podcast#56: Introducing a new series: Reacting to Fountas and Pinnell

Fountas and Pinnell are big names in the field of literacy education. But for years they’ve been accused of advocating methods that do not align with reading research. Fountas and Pinnell have finally responded to this criticism in a 10-part blog series called “Just to Clarify.” This episode is the introduction to a 10-part series in which I respond to their blogs, one by one. It’s my first “reaction” series, and I’m excited! I hope you are too.

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, and welcome to Episode 56 of Triple R Teaching, this is Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom. In this episode, I'd like to introduce an exciting new series that we're going to start next week. It will be a ten part series in which we examine some comments made by two prominent names in literacy education, Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell.

If you're at all familiar with the guided reading levels A, B, C, D, E, etc., then you're connected in some way to Fountas and Pinnell because they were the creators of that leveling system. Many, many schools in the United States in particular use the Fountas and Pinnell reading program.

For many years, I was a huge fan of Fountas and Pinnell! I bought every book they had. I loved their books because they got me excited about teaching reading and showed me ways to get students excited about reading as well! However, after I learned about the science of reading and structured literacy, I realized that their core belief, which has to do with how students read words, especially beginning readers, was in conflict with what I had learned about how the brain learns to read and how we store words for future instant retrieval. Since that time, I've really realized that much of what I've learned from Fountas and Pinnell I can't trust because it starts with the wrong foundation.

Now, really quickly, we can talk about who Fountas and Pinnell are. Irene Fountas is a professor at Lesley University in Massachusetts and Gay Su Pinnell is Professor Emerita at Ohio State. The main concern that people have raised to Fountas and Pinnell is their embracing of three-cueing, which is this idea that students use different cues to help them solve words as they read, particularly beginning readers. And so these students are learning to read using leveled books with words they can't necessarily sound out, but they can use the context or maybe a letter of the word to figure out what they must be. This is a core piece of balanced literacy, which is what I was in for a good twenty years.

I don't think everything about balanced literacy is bad, but three-cueing is definitely a rotten apple. The problem is that even though people have brought all these things to Fountas and Pinnell, they've kind of just dug in their heels. They haven't really engaged in much conversation and they certainly have not denounced three-cueing.

They've recently put out a series of blog posts with audio called "Just to Clarify." In that series, they answer ten questions that have been posed to them in the midst of, as some people would call it, the current "Reading Wars," we could also call it the discussion about the science of reading.

So here are the questions that they answer in their series:The first question is two-part: Why have you chosen not to participate in the latest debate about how to teach reading? What advice do you have for teachers who feel caught in the crossfire while this debate intensifies?

Number two: Can you clarify what MSV (that's three-cueing) is and why you believe it's important?

Number three: Some have suggested you support the use of guessing, can you comment on that?

Number four: How does guided reading and the use of leveled texts advance the literacy learning of children? What role does guided reading play in a comprehensive literacy system?

Number five: In your view of early literacy development, what is the role of decodable texts?

Number six: Could you speak to the role of phonics and teaching children to read, and clarify your approach to phonics instruction?

Number seven: Some people have referred to your work as "balanced literacy" or "whole language." Are these labels accurate?

Number eight: What do you mean by "responsive teaching" and why is it important?

Number nine: Elevating teacher expertise has always been a hallmark of your work. What has led you to advocate so strongly that teachers are the single most important factor in a child's learning achievement?

And finally, number ten: Much has been said about the role of teachers in teaching children how to read, but what role do school administrators, coaches, and other teacher leaders play?

Now, much has been written already in response to these blog posts. One person who has responded is Emily Hanford. You might remember that she was the author of "At a Loss for Words," which first kind of forced me to address the science of reading and structured literacy and start to figure out what the real story was there. Also Mark Seidenberg, who's the author of "Language at the Speed of Sight," in which he talks about how three-cueing is not what works to help children to read (plus a whole lot of other things). Both of them have been very disappointed by the blog series.

In fact, Mark Seidenberg said this, "Fountas and Pinnell clarified for me they haven't changed at all. They illustrate they still don't get it, that they're still part of the problem. These folks just haven't really benefited much from the ongoing discussion about what are the best ways to teach kids to read so that the most kids succeed."

I was reading somewhere else where someone wrote about this and they said it felt like Fountas and Pinnell's legs were stuck in concrete, they just wouldn't move.

Well, is that true? Is that really what they're saying in their series, that they don't care about the science of reading or structured literacy, and they are just going to hold fast to what they think works? We're going to examine that in the next ten episodes. In each episode, I'm going to share a little bit from their answer to each question and then give my response based on what I've learned from the science of reading, that is the research about how we learn to read.

You can find links to their blog posts as well as responses from Emily Hanford and Mark Seidenberg in the show notes for this episode, which you can find at themeasuredmom.com/episode56. Thanks for listening, and we'll see you next week.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Emily Hanford’s response: Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Mark Seidenberg’s response: Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Introducing a new series: Reacting to Fountas and Pinnell appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 22, 2021

A simple process for teaching sight words

TRT Podcast#55: A simple process for teaching sight words

TRT Podcast#55: A simple process for teaching sight wordsWe’ve learned that teaching students to memorize sight words as wholes isn’t the way to go. But what should we do instead? This episode will walk you through a simple process for teaching sight words.

Listen to the episode here Full episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, it's Anna Geiger from The Measured Mom! Today we're going to conclude our three-part series about sight words. In the first week, we talked about misconceptions surrounding sight words. Last week, we talked about the most important thing to remember when teaching sight words. Today we're going to look at a simple process for introducing sight words.

Now, just to be clear, when I use the term "sight word," I'm referring to those high frequency words we want our students to recognize automatically. There's a lot of different definitions around sight words. I believe we talked about that in the first week. Today I'm using it in a more general way, just the idea that these are words we want students to recognize instantly, without needing to sound out or guess.

With that said, let's take a look at a simple process for teaching sight words.

Number one, count the sounds in the word. This is really important because we've learned that we go from speech to print when learning to read, not the other way around. We want our students to examine the sounds in the word.

I might say, "Today we're going to learn to read and spell the word 'some.' Say the word 'some.' Let's count the sounds in the word. In front of you, you have some boxes. I want you to put a counter in each box every time we say a sound. Are you ready? Let's say the sounds of the word 'some': /s/, /ŭ/, /m/. How many sounds? Three. That's right."

That's all you're doing. You're counting the sounds. It can be helpful to have boxes, one for each sound that are going to be in the word, or you can just have them use counters and push them forward for each sound.

The next thing I would say is, "Let's work on spelling each of those sounds. What's the first sound in the word 'some?' /s/. What letter would you expect to see for the sound /s/? That's right, an S. Go ahead and write an S in the first box. All right. Let's point to the second box, which is for the second sound. What's the second sound in the word some? /ŭ/. What letter represents the sound /ŭ/? Yes, it's usually a U, but this word is different. In this word, we're going to put an O. So put an 'o' in the middle box. All right, now it's time for the last sound. What's the last sound in some? /m/. What letter represents /m/? That's right, M. Put an M in the last box, and then we have to squeeze a sneaky letter in there. Squeeze in the E. We're not sure why we have to use an E in the word some, but there it is. Let's look at the word and point to each of the letters. S-O-M-E spells 'some.'"

That would be the first couple of steps. You're going to count the sounds, and you're going to explicitly teach the spelling of each sound.

The next thing I recommend is practicing reading the word in different contexts. First, I would include the word in a list of other words that have a similar pattern. For the word "some," we could read "some, come."

Then I recommend reading the word in some sentences. Those sentences should be decodable based on about where the child would be expected to be in reading development when they are learning this sight word. The word "some" is probably one of the earlier words that you would teach so you'd keep your sentences pretty simple. "I have some cats. I have some cups. I have some dogs," or something like that. You would want them to maybe highlight or underline that sight word and then read the sentences.

Finally, you should have them practice building, tracing, and writing the word. You could give them magnetic letters. You could give them pieces of paper where each piece of paper has one letter of the word. Have them practice building the word a few times. Have them trace it so they can practice the proper proportions for the letters and practice writing the word.

Now there's one more thing that would be really helpful in addition to all of these steps. That would be to have students have a book - a decodable book - featuring the sight word that they can use to practice.

It's hard to find this kind of book. I actually created a whole set of sight word books years ago. They were on my website for years, but I took them down. I took them down a year or two ago because they were not aligned with the science of reading. The sight word books that I created were based on my understanding of balanced literacy, which says that students should use pictures and context clues as they're solving words, at least in those beginning reading books. That's what the books relied on. I thought that seeing the sight word over and over, and then using the pictures and context and everything to read the rest of the book, would help those sight words stick.

But really, our kids are much better off if those "sight word books" they're using are decodable. That way they're practicing their decoding skills, and then they're practicing reading those high frequency words as well.

If you're thinking to yourself, "Okay, those steps sound good. And yeah, those decodable books, that sounds nice. But I don't really have time to create word lists and sentences, and I certainly don't have time to create my own decodable text for all of the sight words that I want to teach. What now?"

The good news is that I have done that for you. My team and I have worked to create a set of 240 sight word lessons. Each lesson comes with a decodable book featuring that high frequency word. These are available in our shop. The regular price is $49, which is a steal because each lesson in each book only costs about 10 cents each.

However, if you're listening to this in real time, and that is November 22nd, 2021 or a few days after, we're offering a special Cyber Monday/Black Friday sale where you can get the whole set of 240 lessons in books for $27. Or you could join The Measured Mom Plus, our membership, which has over 2000 well-organized printables for teaching in a structured way, and we keep adding to it all the time. If you join for the year, you can get this bundle of sight word lessons and books for free through November 29th, through Cyber Monday.

So you've got three options, I guess. You can create the lessons and books on your own, which is totally fine. Or if you'd like someone to do it for you, you can head to my website, and you can go to themeasuredmom.com/sightwordlessons to get the whole bundle for an incredible price, especially if you're getting this in 2021, before Cyber Monday.

Option number three is to join the membership, The Measured Mom Plus, and there, if you do that by November 29th, you will receive all of these for free included with your yearly membership. To learn more about the membership, you can go to themeasuredmom.com/join.

You'll find links to this product in my shop, as well as a link to join the membership, and also a link to some free lessons and books that I've offered on my website, so that you can check to see if it's something that you'd like to invest in. All of this will be on the show notes page, themeasuredmom.com/episode55.

Next week, I'm planning to start an exciting new 10-part series, and I will see you then. Thanks for listening.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resourcesOur sight word blog series begins here.Free sight word lessons and decodable booksIn our shop: The FULL SET of 240 sight word lessons and decodable booksLearn more about our membership hereGet on the waitlist for Teaching Every ReaderJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

Get the FULL SET of sight word lessons and books!

Sight Word Lessons with Decodable Books (Complete Set!)

$49.00 $27.00

With explicit lessons and decodable books, this bundle has everything you need to introduce sight words with confidence!

Buy Now

The post A simple process for teaching sight words appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 16, 2021

Editable sight word games

Our students need to turn a LOT of high frequency words into sight words … words they recognize instantly without sounding out or guessing.

In this sight word series, we’ve talked extensively about how to TEACH sight words. But how do we practice them? After all, students need to encounter the words multiple times to orthographically map them.

The answer?

Editable sight word games!

If you’re looking for editable reading games that you can use at centers, then you should know that I created our bundle of editable reading games for YOU!

When you purchase, you’ll get access to 150 editable sight word games!

Easily differentiate for different learners by plugging in specific words that students need to practice.Have literacy centers ready in minutes when you type in the words and print the no-prep games.

Banish boredom with a huge variety of game formats.

Sneak focused reading practice into game time … your students will have so much fun they won’t even realize they’re learning!Prepare reading games in minutes

Type in up to 12 words, and watch them instantly auto-populate into the games.Click the game you’d like to use, and you’ll jump right to it.Print, and you’re ready to go!Take a peek at some of the games

Type in up to 12 words, and watch them instantly auto-populate into the games.Click the game you’d like to use, and you’ll jump right to it.Print, and you’re ready to go!Take a peek at some of the games

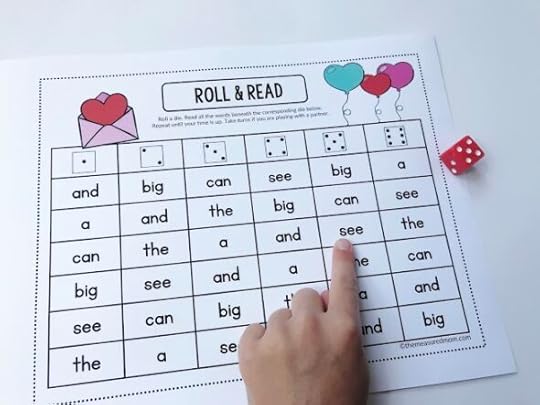

Roll and read is a classic favorite. Students roll a die and practice reading the words in that column. You’ll get an editable version of this game in 10 different formats – one for each month of the school year – plus a non-seasonal game you can use anytime you’d like!

With Cover All, students use a die to move around the board. Each time they read a word, they look for the corresponding picture on their board. If they have the picture, they cover it. The first to “cover all,” wins! Again, you’ll get 10 different versions – one for each school month plus a non-seasonal game.

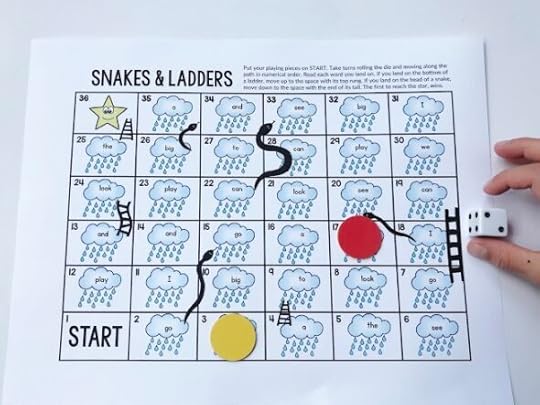

Kids love Chutes and Ladders (ask me how I know – I’ve played the classic version waaay too many times). In this game, students move around the board with a die and read the word they land on. If they land on a ladder, they move up. If they land on a snake, doooown they go.

(You know the drill … 10 versions are included, including a non-seasonal game.)

15 different types of games are includedSpin & GraphSight Word BumpFollow the PathFollow the Path version 2POWWrite the RoomRoll & ReadFour in a RowCover AllSnakes & LaddersSingle Player BingoGo FishTic-Tac-ToeRoll, Read & CoverMemoryCheck out this quick video to learn moreLet me answer your questions about the editable gamesWhat happens after I purchase?

You’ll receive an email with links to download the editable games. Save the files to your computer, and you can access them at any time.

What if I don’t have enough color ink for these printables?

Not a problem! Each printable also comes in black and white.

What if I love a game, but the seasons don’t match the environment I teach in?

Each of the fifteen game styles also comes in a non-seasonal version that you can use any month of the year.

What if I need help with my purchase?

We’re just an email away! Contact our team at hello@themeasuredmom.com, and we’ll respond within 24 hours, excluding Sundays.

Ready to prepare reading centers in minutes?Get the full set of 150 editable games

Editable Reading Games for Every Season – MEGA PACK!

$24.00

With 15 different game styles in ten versions each, you’ll never run out of editable sight word games!

Buy Now

Have you seen the rest of the sight word series?

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Coming soon

The post Editable sight word games appeared first on The Measured Mom.

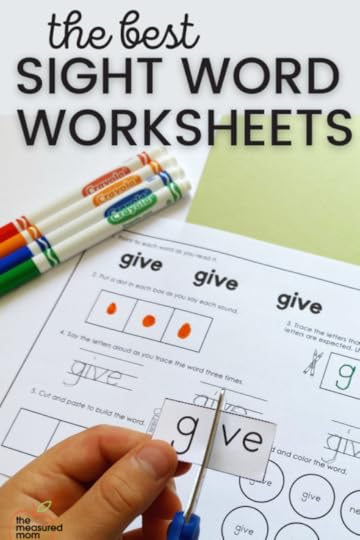

Sight word worksheets – based on the science of reading!

Are you on the hunt for sight word worksheets? Check out our set for 240 sight words … in two levels of difficulty. Bonus – they align with the science of reading!

Have you been following along with our sight word series? This post is the 7th in a ten-part series.

So far, we’ve shared:

The difference between sight words and high frequency wordsThe difference between the Dolch and Fry word listsHow to teach sight wordsWhether or not we should teach sight words in preschoolSight words organized by phonics skillHow to choose kindergarten sight wordsToday we’re going to look at how to choose the best sight word worksheets.

How to choose sight word worksheetsChoose worksheets that draw attention to the individual sounds in each word. We know that this is how we “map” words into our brains – by matching those sounds to the letters. So a good set of sight word worksheets will draw attention to those sounds.Choose a worksheet that gives students practice writing the sight words. This may not be a favorite student activity, but writing those words is so important!

Avoid worksheets that have boxes for writing the letters of different heights. I’m sure you’ve seen them – they’re everywhere. But time and again, I’ve heard reading experts say that this is pointless. It promotes memorizing words as wholes, and that’s NOT how the brain learns to read.

Choose worksheets that call attention to the irregular parts of the word (if there are any).

I’ve designed our new high frequency word worksheets to fit ALL these criteria!

Let’s take a look!

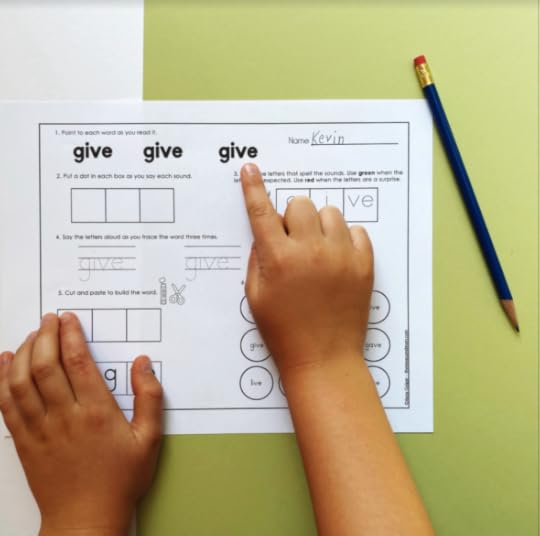

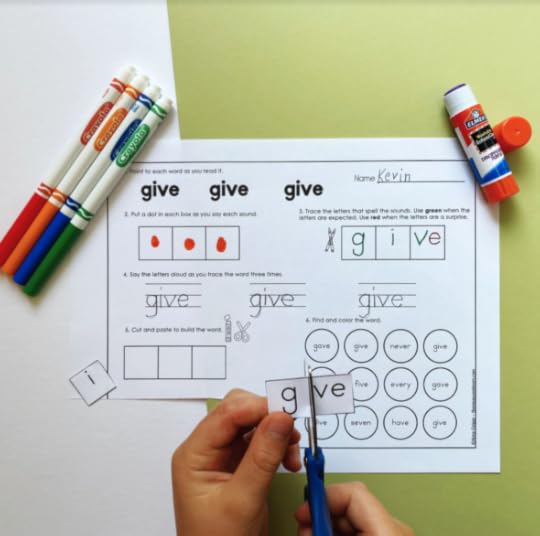

First, students point to the high frequency word and read it aloud, three times.

The next step is something that most sight word worksheets don’t address: counting the SOUNDS in the sight word. In the above example, the student is drawing a dot for each sound: /g/ /i/ /v/.

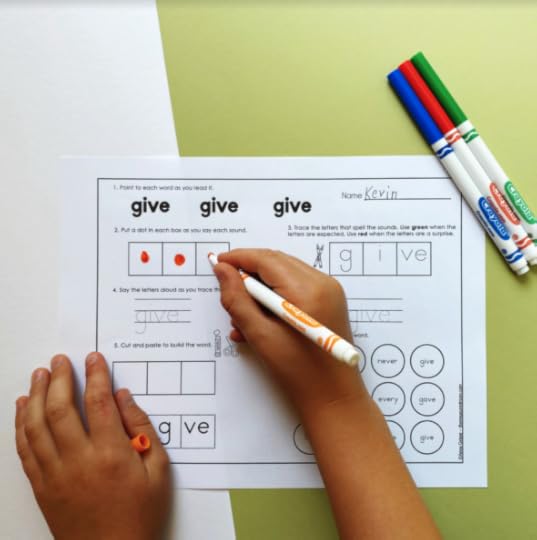

In this step, trace the spelling for each sound in the word. You’ll notice that “ve” are in a single box because both letters work together to make the /v/ sound in “give.”

We draw students’ attention to the surprising parts of the word by having them color the expected spellings in green and the unexpected spelling(s) in red.

In the above example, we don’t expect that “e” to be there, because the i isn’t long like it is in most CVCE words.

Please note that students will color code differently, depending on where they’re at with their phonics knowledge. Some students may know that English words don’t end with v, so to them that e isn’t surprising at all!

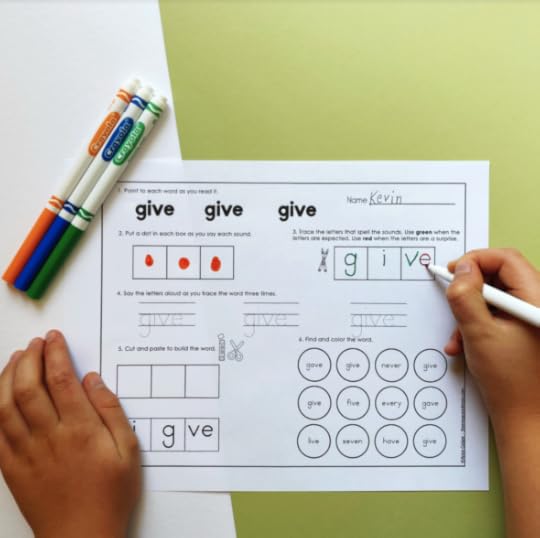

Time for handwriting practice! Not everyone’s favorite, but it’s very important to practice writing the word. We need to be able to spell it as well as read it!

In the Level One version of our worksheets, students cut apart the word, sound-spelling by sound-spelling.

Notice that I did NOT say, letter by letter.

It’s important for students to see that more than one letter can be used to represent a single sound.

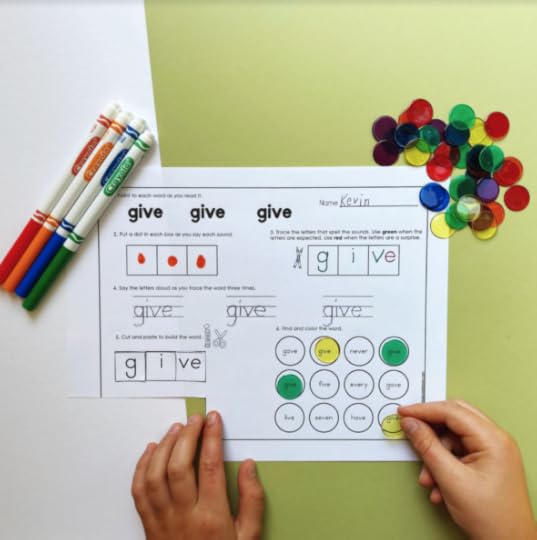

After students have glued the letters down, they have a fun little break with the word find activity. They can cover the words with clear counters or color with marker or crayon.

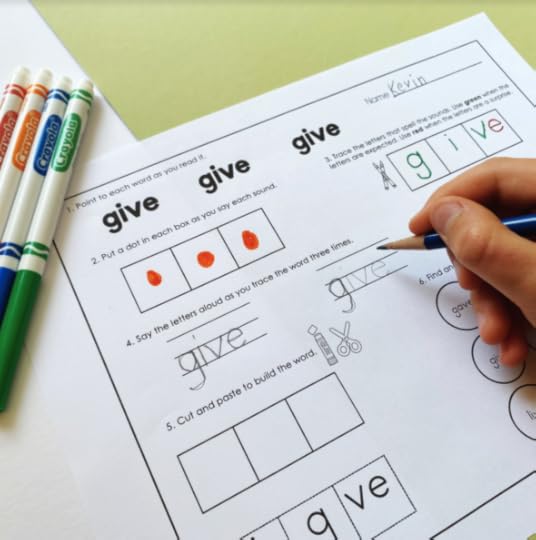

Our sight word worksheets include TWO versions of each worksheet. In the level 2 worksheet, as you can see above, students do not do the cut-and-paste or word find activity.

Instead, they write an original sentence and use the editing checkboxes in number 6 to check their work.

Answers to your questionsWhich words are included? Both versions include worksheets for 240 high frequency words. They include the words from Dolch’s list of 220 words and Fry’s first 100, plus a few extra. View the complete list here.Is the file easy to use? I don’t have time to scroll through 240 words every time I need a worksheet. You bet it’s easy! We have a clickable table of contents near the beginning of the file. Just click on the word you need, and you’ll jump right to it!

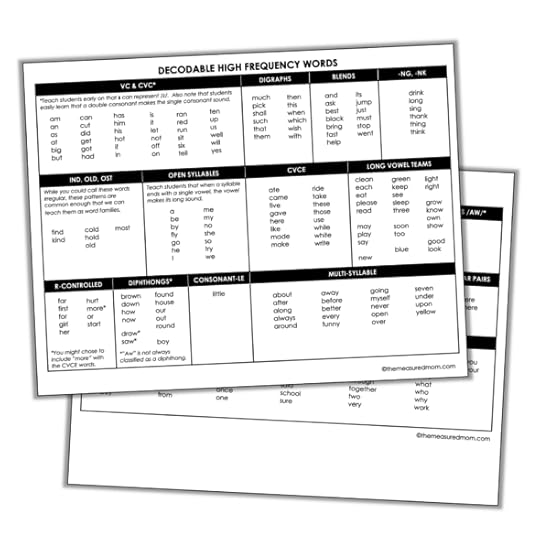

How do I know which words to start with? It’s best to teach the words alongside phonics instruction whenever possible. So I would think about which phonics skill you’re teaching and then teach sight words that align with those skills. This way students’ focus is on the letters themselves and not on memorizing words as wholes (which can only be done for so long … eventually the brain gets overwhelmed). Inside the file you’ll find a list of the 240 words organized by phonics skill to help you out!

These helpful charts are included with your purchase.What age are these worksheets for? I recommend teaching high frequency words to students who already have some ability to sound out words (even if it’s just basic 3-letter words). Once children have important pre-reading skills in place AND show an ability to sound out simple words, they are ready for some of these worksheets. This will include some (but definitely not all) pre-K students, most kindergarten students (by mid-year), and children in first, second, and third grade.

These helpful charts are included with your purchase.What age are these worksheets for? I recommend teaching high frequency words to students who already have some ability to sound out words (even if it’s just basic 3-letter words). Once children have important pre-reading skills in place AND show an ability to sound out simple words, they are ready for some of these worksheets. This will include some (but definitely not all) pre-K students, most kindergarten students (by mid-year), and children in first, second, and third grade.How do I know if my preschooler is ready for sight words? I wrote a blog post to answer this very question! You can find it here. Ready to get started?

Get the full set of 240 worksheets!

Sight Word Worksheets – Based on the science of reading!

$15.00

You’ll get two versions of each worksheets, with a clickable table of contents so you can quickly find the word you need!

Buy Now

Have you seen the rest of our sight word series?

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Coming soon

The post Sight word worksheets – based on the science of reading! appeared first on The Measured Mom.

The best kindergarten sight words

Have you been following along with our sight word series? We’ve talked about what sight words are, how to teach them, and why it’s important to integrate sight word teaching with phonics. Today we’ll tackle kindergarten sight words.

Many schools require kindergarten teachers to teach a long list of sight words to their kindergartners.

Unfortunately, lists of kindergarten sight words are often problematic.

To understand why, we need to remember WHAT sight words are and HOW we learn to read them.

A quick review … what are sight words?Even though I use the term “sight words” throughout this series to refer to high frequency words that children need to learn, it’s important to remember the true definition.

A sight word is a word that is instantly and effortlessly recalled from memory, regardless of whether it is phonically regular or irregular. A sight-word vocabulary refers to the pool of words a student can effortless recognize.

David A. Kilpatrick, PhD

Our goal, then, is to turn high frequency words (words that appear often in print) INTO sight words – words our students recognize automatically without needing to sound out or guess.

Why memorizing sight words isn’t a good long term strategyWhile we may teach our students to memorize a handful of words to get them going, our goal is NOT to teach our students to memorize sight words as wholes.

They can only do this for so long – the brain is not able to memorize an unending number of words, because that’s not how the brain learns to read.

We learn to read by matching the sounds to the letters (sounding out words). When we do this enough times, we orthographically map the word into our brains so that when we see it in the future, we recognize it automatically.

We cannot orthographically map words unless we pay attention to the letters and their sounds.

Conclusion = teach sight words by calling attention to their letters and sounds. Learn more in this post: How to teach sight words.

How to choose kindergarten sight words

How to choose kindergarten sight words If I could banish the Dolch grade level sight word lists, I would!

While I do think that the Dolch and Fry word lists are helpful because they give us the most common high frequency words, the grade level lists are just ridiculous.

(Case in point: the CVC words cut and got are on the third grade list. Huh??)

So let’s just agree that the Dolch kindergarten list is not any kind of authority for choosing kindergarten sight words.

Instead, you need to consider two things when choosing your sight words:

Choose high frequency words that are decodable, and teach them when you teach the corresponding phonics skill.Choose high frequency words that students will encounter in their decodable books .Decodable sight words for kindergartenWhen I look at my own scope and sequence for teaching phonics skills, I consider the following to be appropriate phonics skills to teach in kindergarten. (Depending on the setting, teachers may not have time to address the later skills in this list.)

VC words (if, it, etc.) CVC words (can, bat, etc.)Words with beginning and ending digraphs (th, sh, ch, etc.)Words with beginning blends (fr, st, sl, etc.)Words with ending blends (-st, -mp, etc.)Words that end with -ng and -nkThe -ild, -old, -ind, -olt and -ost word familiesOpen syllable one-syllable words (he, she, be, etc.)Knowing that, let’s look at words from the Dolch and Fry lists that fit these patterns. You can teach these words WITHIN your phonics lessons.

While you WILL need to teach some of these words before you teach the phonics skill (so kids can read their decodable books), most of the following words should not be taught as whole words to memorize.

VC and CVC high frequency words

amanasatbigbutcancutdidgetgothadhas*himhishotifinis*itletnotoffoinranredrunsitsixtell**tenupuswell**willyes*Teach your students that “s” can represent the /z/ sound.

**Technically not CVC, but students easily learn that two identical letters in a row represent a single sound.

High frequency words with digraphs

muchpickshallsuchthatthemthinthiswhenwhichwishwithHigh frequency words with blends

andaskbestblackbringfasthelpitsjumpjustmuststopwentHigh frequency words that end with -ng or -nk

drinklongsingthankthingthinkHigh frequency words in the -ind, -old, and -ost families

findkindcoldholdoldmostHigh frequency open syllable words

abebyflygoheImemynoshesotryweWOW! That’s a LOT of words that we can teach right within our phonics lessons … no memorization necessary!

And yet … you SHOULD teach some of these words before you get to their appropriate phonics lesson. For example, kids will obviously need to read “a” and “I” from the very beginning.

Other decodable high frequency words that you will probably want to teach early on include and, go, he, she, and we.

I also don’t want to give the impression that practice isn’t incorporate. Kids need to read these words over and over again to orthographically map them.

I recommend using editable reading word games so you can type in the words you want your students to practice.

Check out our editable reading games!

Editable Reading Games for Every Season – MEGA PACK!

$24.00

You’ll get a variety of editable games for every season. Just type in the words you want your students to practice, and print!

Buy Now

What about irregular kindergarten sight words?

There are a fair number of high frequency words that we can’t sound out (or at least we can’t sound out all the parts).

Which ones should we teach in kindergarten?

This is a tough call. There is NO perfect list.

My recommendation is to teach the words kids are most likely to encounter in the decodable books they’re reading within their phonics lessons and for reading practice.

(Notice:I did NOT say “the words they are encountering in their leveled books. If you are using leveled books in kindergarten, I get it. I did this in first grade for years. But now I understand the problem with this approach. Check out my podcast, Should you use leveled or decodable books? for more information.)

A possible kindergarten list of irregular high frequency words

theis (technically not irregular, because “s” often represents /z/)toaredoesfromofonesaidtheytwowaswerewhatwhoyouyourgivehavehas (technically not irregular, because “s” often represents /z/)Well, look at that! That list looks pretty manageable. It’s not complete – students need to learn decodable high frequency words as well – but when you have a systematic approach to phonics instruction, they’ll be learning those words as you go.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Coming soon

The post The best kindergarten sight words appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 14, 2021

The most important thing to remember when teaching sight words

TRT Podcast#54: The most important thing to remember when teaching sight words

TRT Podcast#54: The most important thing to remember when teaching sight wordsThere’s a lot of misinformation out there about teaching sight words. In this episode, we boil it down to the MOST important thing to get right.

Listen to the episode here Full episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello everybody! This is Anna Geiger from The Measured Mom, and we are in the middle of our short series all about sight words here on the Triple R Teaching podcast.

Last week we talked about misconceptions around teaching sight words. This week, in Episode 54, we are going to talk about the most important thing to remember when teaching sight words.

I can say it in just two words. Are you ready?

Phonics first.

There's two implications for that. Number one, we don't teach sight words until students can use phonics to sound out words. And number two, we USE phonics when teaching sight words instead of teaching students to memorize words as wholes. So let me explain both of these implications for phonics first.

Number one, it's really important to remember that young children should not be spending a lot of time learning sight words if they can't sound out words. That isn't to say that there isn't a small set of sight words that we can teach them to memorize, words like "a, I, the, of," and so on - a very small number.

But in general, we should wait to teach sight words until kids can sound out words. In fact, researchers tell us that children will do better at learning sight words, even irregular ones, if they're good at decoding. That's something I learned from Rollanda O'Connor's book, Teaching Word Recognition, which I highly recommend.

There's a lot of confusion around this and a lot of people think that teaching sight words is the way to begin. I totally understand because that's what I used to think! However, children will do better in learning to read if they have a core set of pre-reading skills.

Those important pre-reading skills are concepts of print, where they know how to turn the pages and they know that each word they say is represented on the page. They are language and listening skills, so they can retell a story and they can answer simple questions about it. They include letter knowledge, so they know the letters of the alphabet and most, if not all, of the letter sounds. They include phonological and phonemic awareness, which has to do with things like rhyming, counting syllables, and identifying individual sounds in words. Finally, they include interest in learning to read.

All those things should be present before children learn to read. But that doesn't mean that once those things are present, we start with sight words. We should actually teach them to sound out words.

Like I said, I used to think that students should learn sight words first, and that's because it seems a lot easier. Because I believed this, I used to share a huge set of sight word books for preschoolers and kindergartners to learn to read. I thought they could memorize the repeated sight word and then use the pictures to "read" the rest of the words.

Notice that "read" is in quotes. Although I thought it was "read" for real, because I believed in something called three-queuing, something I learned about in college and grad school. I no longer recommend that. If you want to know more, you can check out my podcast episode, What's Wrong with Three Queuing. I won't get into that today.

What if you understand when I say that you shouldn't start teaching reading with sight words - except for that little handful to get them going - and that you should teach kids to sound out words, BUT your preschooler or kindergartner is really struggling to get those sounds to blend together? Well, then you need to go back to those pre-reading skills and check on them, especially phonemic awareness, and you should start with oral blending.

So if you have the word "cat," you should try to see if they can make the word if they just listen. So if you said, "Put these sounds together to make a word, /c/, /ă/, /t/. What's the word? Cat." If they can't do that oral blending, learning to read is going to be really hard. There's really no point in expecting them to memorize lists and lists of sight words, thinking that's going to help them to learn to read. They have to learn to match those phonemes to the graphemes, those sounds to the letters.

They can't possibly learn to read by memorizing and memorizing and memorizing because their brain can only do that for so long. So rather than thinking that we're teaching them to read by having them memorize these lists of words, because sounding out was hard, we're actually wasting our time! What you're better off doing is spending your time building phonemic awareness, which is a whole different topic, but I have a lot of resources on my website and on this podcast. I will link to them in today's show notes.

Once they understand the concept of decoding words and they're ready to read a simple decodable book, you'll need to teach the high frequency words that are included in the book. Sometimes we call them sight words. Last week, I talked about how that definition of sight words isn't exactly accurate. I know I'm going to confuse you by continuing to use it just because I know that's how many people still use it. But technically, we're talking about high frequency words here, irregular high frequency words.

So if a child is learning to sound out CVC words, the book's text may look like this, "The cat is big." Well, the child can sound out "cat" and "big," but not necessarily "the" and "is," unless you've taught the child that "s" can say /z/. So you'll need to teach those irregular words, but that's not going to be our focus, right? Our focus mostly is going to be on decoding words.

The second thing to remember when it comes to phonics first is to teach sight words or high frequency words, even the irregular ones, within your phonics lessons.

Last week I said that a major misconception about teaching sight words is this idea that we should teach sight words as wholes. That's been around for a long time. In fact, that's what both Edward Dolch and Edward Fry both believed, and they're the ones that came up with the big high frequency word lists that we use today.

If you've ever looked at the Dolch high frequency word list and seen that it's organized by grade level, I'm sure you said, "Hang on a second, who came up with this?" The third grade list has words like "cut, got, hot," and "if," which is frankly pretty ridiculous because if you're in third grade and you can't sound those out, you have a bigger problem than not knowing sight words or high frequency words. So yeah, don't go by that list because it's all about frequency - when those words occur in text for different grade levels - it's not about phonics skill.

It really makes more sense to look at all those common words that are in text and then sort them by phonics skill. So you wouldn't have to teach "cut" by itself, you could just teach it within your phonics lessons when you're teaching kids to sound out CVC words with short u. The same is true for a lot of other words.

Now, does that mean that all of the words are decodable? Definitely not. There are many irregular words on the Dolch and Fry lists, but you can still call attention to the parts that are regular and then have kids memorize the irregular parts. We'll talk more about that next week when I share a simple process for teaching sight words.

Let's quickly review what we went over today.

The most important thing to remember about teaching sight words is phonics first. Phonics first means two things. We do not start beginning readers with sight words. Sure, we can teach them a small handful of sight words just to get them going, but that is not the main focus. We want to build those pre-reading skills, phonemic awareness, and the skill of phonic decoding BEFORE we teach a lot of high frequency words. Researchers tell us the better kids are at decoding words, the better they're going to be at reading those irregular high frequency words as well. So decoding is really important!

The number two thing to remember about phonics first is that we should be teaching these high frequency words, both regular and irregular, within the context of phonics lessons. Many, many of the words, probably at least half that we find on these high frequency word lists, are actually fully decodable. Teach them within your phonics lessons. For the others, we can call attention to the decodable parts and special attention to the parts that are irregular, which we'll get into more next time.

Please remember I've got a full blog series on my website right now all about sight words. You can go to themeasuredmom.com/sightwordseries.

I have a really special gift for you that's available now, I put together a list of sight words or high frequency words organized by phonics skill. It's on my website and you can find it by going to themeasuredmom.com/phonicsandsightwords. So it's themeasuredmom.com/phonicsandsightwords. That has both the regular and irregular words organized by phonics skill.

Check that out and print it for yourself as a ready reference, and stay tuned because next week we have a very special offer for Black Friday and Cyber Monday and it's all about a complete new resource we have for teaching high frequency words to master.

You can find the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode54. See you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related blog posts, podcast episodes, and other resourcesOur sight word blog series begins here.Strongly recommended book (I read the whole thing cover to cover – a rarity for me!): Teaching Word Recognition, by Rollanda E. O’Connor5 important pre-reading skillsDo’s and don’ts for teaching phonemic awarenessWhat’s wrong with three-cueing?

Download your free list of sight words organized by phonics skill

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every ReaderJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post The most important thing to remember when teaching sight words appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 7, 2021

4 Common Misconceptions about Teaching Sight Words

Should we use the Dolch grade-level lists to help us decide which sight words to teach? Should we teach our students to memorize sight words as wholes? And should beginning reading instruction START with sight words? Get answers to these questions and more as we look at common misconceptions surrounding the teaching of sight words.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello! Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and I'm so glad to welcome you to another Triple R Teaching podcast episode! Today, we're going to talk about sight words, specifically four common misconceptions about sight words.

The first misconception that people have about sight words is that they are words that cannot be sounded out. For example, the word "the" would be a sight word.

Many people still define sight words this way, as words that kids cannot sound out, words they have to simply memorize, but this definition is actually not correct. Sight words can certainly be irregular, but the definition of sight words is not "words kids can't sound out."

Reading researchers have a different definition of sight words. It's really good to refer to David Kilpatrick's definition. He says that "a sight word is a word that is instantly and effortlessly recalled from memory, regardless of whether it is phonically regular or irregular." A sight word vocabulary refers to the pool of words a student can effortlessly recognize.

Some people use the terms, "sight words" and "high frequency words" interchangeably, but they're not the same thing.

A high frequency word is one of the words that is most commonly used in the English language. A high frequency word can be regular as in "and," or it can be irregular as in "the." The goal is to help our students turn these high frequency words into their own personal sight words, words that they can recognize instantly - preferably within a second.

Having definitions straight is always important as we move forward,so I wanted to start with that one. Sight words are words that students know automatically. They are not necessarily phonically irregular words.

Misconception number two, we should use the Dolch grade level sight word lists as a guide when choosing words to teach our students.

Now, first of all, there's nothing wrong with referring to the Dolch and Fry sight word lists. For high frequency words our students need to know, I certainly refer to those lists. However, it's good to know where Dolch and Fry were coming from.

Edward Dolch and Edward Fry, both Edwards, which is kind of funny, were advocates of the whole word approach, so they were not big on teaching phonics. Not that they necessarily said you shouldn't, but they thought that it was secondary. In fact, in his book, "Teaching Primary Reading," Edward Dolch said that first graders should only learn sight words and teachers should wait until second grade to introduce phonics. So that's obviously NOT the path we want to follow, especially if you've been following along with my science of reading episodes.

So we have to be careful. Dolch and Fry don't espouse a lot of really great ideas about teaching reading when it comes to high frequency words. However, like I said, their lists are helpful because they help us know what words are most common. These are good words for children to know automatically.

The problem with the Dolch words is the grade level categories. I'm not exactly sure how those came about, but I believe they have to do with how often those particular words were present in grade level text. So for example, a third grade level text, what high frequency words were most present in third grade versus kindergarten and so on. Now where exactly they got the grade level text, that's something else I don't know. But if you take a look at the word lists for Dolch, the grade level word lists, you're going to start to wonder a little bit, who came up with this stuff? Because if you look at the third grade level list, it has these words "cut, got, hot, if". Those are not third grade level words, by any stretch of the imagination! I certainly hope that a child who is reading as they should be by third grade does not need to memorize those words! They read them automatically because they learned a long time ago how to read vowel-consonant and consonant-vowel-consonant words. It's silly.

Similarly, some of the words on the kindergarten list are pretty tough, like "please" and "pretty." I'm not sure why it's necessary to teach kids to learn those long words by sight in kindergarten. So yeah, the Dolch and Fry sight word lists can be a good reference for high frequency words, but are not so good when it comes to knowing WHEN to teach them.

Misconception number three is one that Dolch and Fry had themselves, that we should teach sight words as whole words.

We talked about this way back in our series about the science of reading. We talked about how even skilled readers do not recognize words as wholes, because if you did that, you would have memorized 30,000 to 70,000 words. That's how many words you recognize instantly without having to sound out or guess. Your brain cannot do that.

The only way you know all these words so quickly is because you've gotten really good at a mental process called orthographic mapping. Orthographic mapping is that you connect each individual sound to each individual letter or letter pair in the word. You're connecting the phonemes to the graphemes very, very, very, very, very, very fast. You have gotten really good at that because you're good at phonic decoding and phonemic awareness.

That's what we want our students to become good at, decoding and phonemic awareness. Those are two important skills we're going to teach them. As they learn those, they're going to get better at converting those high frequency words into sight words, words they recognize instantly.

So we don't want to start with sight words by giving flashcards and expecting kids to just memorize the shape of the word. That's not where we're going. Later in this series about sight words, we'll get very specific about how to teach sight words, but for now we just want to know that a common misconception is that you should teach them as wholes. That is not true.

And finally, another misconception about sight words is that we should START beginning reading instruction with sight words.

This was definitely a misconception that I used to have because as I taught my young children, my preschoolers, to read, I noticed it was a little hard for them to sound out words, but they could memorize words a little bit easier. So that felt like the best way to start. What I didn't realize was that the reason they struggled with sounding out words was because they needed more work with phonemic awareness.

Phonemic awareness is this ability to play with individual sounds in words. So if a child can orally blend, like if you said, put these sounds together, /f/ /i/ /sh/, and they can put them together and say "fish," they're on the path to reading. They're probably going to have some success in sounding out words.

But if they don't understand that words are made of individual sounds, they can't isolate phonemes and they can't segment or blend phonemes, then sounding out words is going to be tough. So it's better to spend time building phonemic awareness and THEN teach kids to sound out words and THEN teach some sight words.

Can you start by teaching a handful of "sight words," words that kids can just recognize instantly, before doing phonics? Kids will probably learn to recognize a few words even if you teach it to them rather quickly, such as "the" perhaps, but you don't want to go too far with that before you're doing phonics.

I really recommend starting with phonics and then teaching a handful of sight words, even if they don't know the phonics patterns, to help them read decodable books.

So for example, if the book says, "The cat is big," a child cannot read "the," unless you just teach them to know that word. And they might not know "is" either if you haven't taught them that "s" can also of say /z/.

So when we're teaching preschoolers or kindergartners to read, we don't want to start with big lists of sight words. We can teach a handful of sight words to use with the decodable texts they are reading, but we want to start primarily with phonics, with sounding out words. And if that's not working, it's because we need to go back and make sure we've got phonemic awareness well in hand.

So let's quickly review those four common misconceptions when it comes to sight words.

Number one, this idea that sight words cannot be sounded out. Well, it's true that SOME high frequency words cannot be sounded out. A sight word is really a word you recognize instantly, without needing to sound out or guess. Our goal is that our students convert high frequency words into sight words, their own personal sight words.

A second misconception is that we should use the Dolch grade level word lists as a guide for deciding when to teach words. If you take a close look at the word list, you'll find out whoa, that doesn't really make sense! Look at where they all go. There's CVC words in the third grade list. It doesn't make sense at all. What you really should be doing is thinking about the phonics lessons that you're teaching and try to incorporate the high frequency words with your phonics instruction, but we'll get to that in a future episode.

Number three, a misconception is that we should teach sight words as wholes. This idea has been prominent for a long time. Certainly Edward Dolch and Edward Fry, the creators of the most popular high frequency word lists believe this. I mentioned that one of them even said that we shouldn't teach kids to sound out words until second grade. That is a problem because it bypasses orthographic mapping, which as you recall is that children and adults connect sounds to letters, phonemes to graphemes. So no, we should not teach sight words as individual whole words. We should call attention to the parts of the word that are phonically regular, and then study the parts that are not. But again, we'll save this for a future episode.

Finally, we should begin reading instruction with sight words. That is another misconception. In fact, we want to start with phonics. If children are struggling to sound out words, that means they need work in phonemic awareness, and we need to go back and build that before we focus too heavily on sounding out words.

So I hope that gave you a few things to think about. I look forward to joining you next time to teach more about sight words. In the meantime, I recommend checking out my ten part sight word series on the blog, The Measured Mom. We talk about the difference between sight words and high frequency words, the differences between the Dolch and Fry lists, how to teach sight words, how we should approach sight words in preschool and kindergarten, sight words organized by phonics skill, and a whole lot more.

You can check out that series by going to themeasuredmom.com/sightwordseries. One more time that link is themeasuredmom.com/sightwordseries.

You can check out the show notes for this episode, by going to themeasuredmom.com/episode53. Thanks for listening. And I'll talk to you again next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Check out these posts from our sight word series!What is the difference between sight words and high frequency words?What is the difference between Dolch and Fry sight words?How to teach sight wordsShould we teach sight words in preschool?Sight words organized by phonics skillGet on the waitlist for Teaching Every ReaderJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post 4 Common Misconceptions about Teaching Sight Words appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 4, 2021

Do phonics and sight words go together?

A small number of words make up a large percentage of the words that appear in print. These are called high frequency words.

It’s important that our students recognize a large number of high frequency words by sight so they can read fluently.

We call these words – the words they recognize instantly without needing to sound out or guess – their sight word vocabulary.

In essence, we want our students to turn high frequency words into their own personal sight words.

Some of these high frequency words are easy to sound out (words like in and can). Others are irregular and don’t follow predictable phonics patterns (words like the and some).

Both Edward Dolch and Edward Fry (yes, both were Edwards!) put together lists of high frequency words several decades ago.

I think Dolch and Fry did us a service by collecting high frequency words.

But they had a real problem when it came to execution.

Dolch and Fry both believed that we should teach students to memorize these high frequency words as wholes.

Yet the majority of these high frequency words can be sounded out … they don’t need to be memorized as whole words at all!

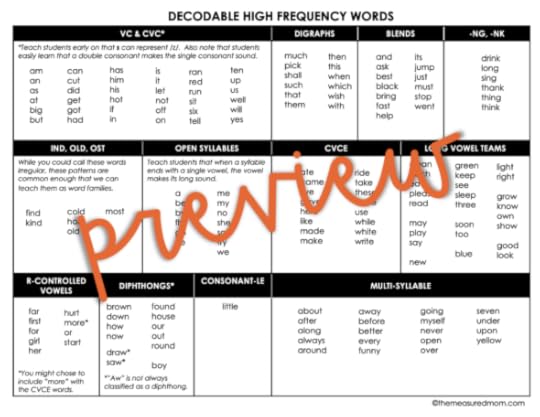

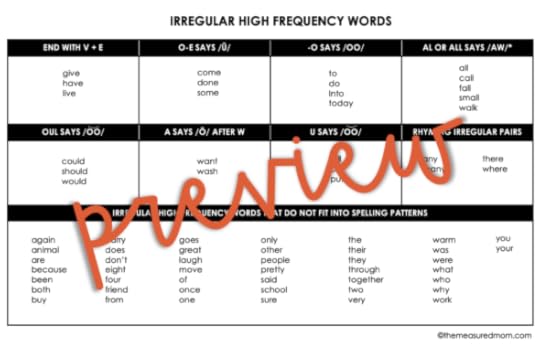

Let’s take a look at sight words organized by phonics skill.

In many schools, beginning readers are expected to memorize long lists of sight words.

Too often, the “sight words” they are expected to learn each week have nothing to do with that week’s phonics skill.

While this is certainly going to happen with irregular words and a few others, our GOAL should be to combine teach high frequency words WITHIN our phonics lessons as much as possible.

Don’t trust the “grade level” sight word listsThe Dolch sight word list of 220 words has been organized by grade level. I used to refer to it often. (In fact, I used to sell my high frequency word practice mats organized by Dolch grade level. Now I just sell them as a single set.)

But there’s nothing sacred about the Dolch grade level sight word lists; there is no reason to follow these leveled lists when choosing what words to teach our students.

For example, the high frequency words “cut,” “got,” “hot,” and “if” appear on the Dolch third grade sight word list.

What??

Clearly, kindergartners who have learned to read CVC words can read these words without any trouble. Cut, got, hot and if do NOT need to be taught separately as words to memorize … and we certainly don’t need to wait until third grade to address them!

What about the kindergarten Dolch sight word list?

It contains words like “please” and “pretty.” There’s nothing wrong with waiting to teach “please” until you teach the “ea says long e” phonics pattern (likely not until first grade). And the word “pretty” is such an irregular one that you should probably wait to teach it.

Teach high frequency words according to spelling pattern whenever possible

Sight words by phonics patternOf my list of 240 high frequency words, well over half of them can be organized by phonics pattern.

Yep, these words are DECODABLE!

That means that the words you need to teach kids to memorize (although you don’t even have to do that, as we’ll get to in a minute), is MUCH smaller.

Here’s a quick screenshot of sight words organized by phonics level. (Scroll down to the end of this post to download the pdf for free.)

Do we have to teach the words in the above order?

No. This list is organized by my personal scope and sequence, which you can get for free here. There is no perfect scope and sequence, so you certainly don’t need to follow mine exactly.

But you DO want to make sure that your scope and sequence goes from simple to more complex.

There are also times that you’ll want to teach words earlier than they’re listed.

For example, you wouldn’t necessarily introduce SEE until you teach the “ee says long e” pattern, likely in first grade. But this simple word is easy to recognize by sight, and I recommend teaching it is a “sight word” in kindergarten or possibly even Pre-K.

The same is true for words like A, I, GO, and FOR. You don’t need to wait until you teach the corresponding phonics pattern.

But in general, it’s good practice to combine sight words with phonics instruction.

What about irregular sight words?Great question.

You can STILL incorporate phonics by recognizing that many of these surprising words are part of a set.

Teach them that way.

For example, don’t teach “any” one week and “many” several weeks later. Teach them together. Teach your students that in these words, the “a” represents the short e sound. The “y” at the end represents the long e sound.

Don’t teach “come” and “some” separately. Teach them together. Teach your students that in these words, the o-consonant-e pattern represents the short u sound.

In the free download at the end of this post, you’ll also get a list of irregular high frequency word, organized by phonics skill.

But what about irregular sight words that don’t share spelling patterns?

But what about irregular sight words that don’t share spelling patterns?You can still use phonics by addressing the parts of the words that are regular and then learning the surprising parts “by heart.”

Have you seen the heart word magic videos from Really Great Reading? They do a great job showing you how to incorporate phonemic awareness and phonics so you don’t rely on whole word memorization.

Here’s a good routine to follow when teaching irregular sight words:

Name the new word, and have your learner repeat it.Name the individual phonemes (sounds) in the word. For example, in the word does, there are three phonemes: /d/, /u/ and /z/.Spell the sounds. Call attention to any unexpected spelling. In does, we spell the short u sound with “oe” and the /z/ sound with s.If possible, have your learner read related words. Have your learner read connected text. Connected text can be decodable sentences or decodable books.Download your FREE sight word list organized by phonics skill below!

Download your free word lists here

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

You’re invited to check out the rest of our sight word series …

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon

The post Do phonics and sight words go together? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Preschool Sight Words

How should I introduce sight words to preschoolers?

What is a good sight word list for preschoolers?

Where can I find preschool sight word worksheets?

These are all questions I’ve heard from parents who are eager to get their children on the right path when it comes to learning to read.

They are all good questions, but I think we need to back up and ask this question first:

SHOULD we teach sight words in preschool?

First of all, let’s clarify what sight words are. Some people will tell you that sight words are words that cannot be sounded out.

But researchers’ definition of sight words is different. Sight words are words that a reader recognizes instantly, without needing to sound out or guess.

Therefore, all beginning readers have a different sight word vocabulary, because they all know a different set of words “by sight.”

It’s probably best to speak in terms of “high frequency words.” These are the most commonly used words in printed text.

Obviously, readers need to know high frequency words.

But HOW they learn these high frequency words matters.

We’ll get to that in a minute.

First …

What should preschoolers know BEFORE they learn to read?This is an important question to answer.

After all, we don’t teach newborn babies to read. Why not?

They’re not ready (obviously).

They’re not ready because they need a set of important pre-reading skills.

5 important pre-reading skills for preschoolers1- Concepts of printThey hold books correctly and turn pages in the right direction.They know that each word on a page represents a spoken word.They understand that text is read from left to right. 2- Language and listening skillsThey can retell a familiar story in their own words.They engage with a story as you read to them — asking questions (“Why did he say that?”) and making personal connections (“I wish I could have that much ice cream!”)They can answer simple questions about a story.

2- Language and listening skillsThey can retell a familiar story in their own words.They engage with a story as you read to them — asking questions (“Why did he say that?”) and making personal connections (“I wish I could have that much ice cream!”)They can answer simple questions about a story. 3- Letter knowledgeThey recognize the letters of the alphabet.They can name each letter’s sound (or a large number of them).4-Phonological and phonemic awarenessThey can count words.They can count syllables in words.They can rhyme.They can put sounds together to make a word. If you say these sounds to your child, /f/ and /ish/, can he put them together to make fish? If you stretch a word and say it like this — mooooon – does your child know the word is moon? They can identify the first and last sound in a word. This is not the same thing as knowing the letter. For example, if you ask your child the first sound in the word phone, she should be able to answer /f/.

3- Letter knowledgeThey recognize the letters of the alphabet.They can name each letter’s sound (or a large number of them).4-Phonological and phonemic awarenessThey can count words.They can count syllables in words.They can rhyme.They can put sounds together to make a word. If you say these sounds to your child, /f/ and /ish/, can he put them together to make fish? If you stretch a word and say it like this — mooooon – does your child know the word is moon? They can identify the first and last sound in a word. This is not the same thing as knowing the letter. For example, if you ask your child the first sound in the word phone, she should be able to answer /f/. 5- They have an interest in learning to read.They enjoy being read to.They frequently ask you to read aloud.They pretend to read.After pre-reading skills are in place, we should teach preschoolers to sound out words.

5- They have an interest in learning to read.They enjoy being read to.They frequently ask you to read aloud.They pretend to read.After pre-reading skills are in place, we should teach preschoolers to sound out words.Once students are ready to read, we teach them to blend sounds into words.

I used to teach that students should learn sight words FIRST, because it can seem easier to memorize a few words than to sound them out.

Because I believed this, I created a huge set of sight word books for preschoolers to “learn to read.” I thought that they could memorize the repeated “sight word” and use the pictures to read the rest of the words.

I don’t share those sight word books anymore, because I’ve learned that three-cueing (something I learned to use in college and grad school) is a major problem and NOT something we should be teaching beginning readers to use. (I won’t get into that here, but you might want to check out my podcast episode: “What’s wrong with 3-cueing?”)

What if preschoolers struggle to sound out words?If your child struggles to sound out simple words, you might think that you should switch to giving them them lists of words to memorize.

That is NOT the answer.

Instead, you need to go back to those pre-reading skills and make sure they’ll all in place … particularly phonemic awareness.

Phonemic awareness is the ability to play with individual sounds in words.

Readers should be able to isolate, blend, segment, and manipulate phonemes.

While we certainly can (and SHOULD) continue to teach phonemic awareness as we teach phonics, if children don’t have the basics, they will not be successful with reading.

Practice ORAL blending if your child struggles to sound out a 3-letter word like hat.

You can say, “Put these sounds together to make a word. /h/ /a/ /m/. What’s the word?” If your child cannot say HAM, then you need to build phonemic awareness before sounding out words.

Build phonemic awareness with our hands-on games!

Phonemic Awareness Games & Activities

$24.00

Get your preschooler ready to read with this interactive set of phonemic awareness activities.

Buy Now

AFTER preschoolers are starting to sound out words, we can teach “sight words.”

When your child understands the concept of decoding words and is ready to read a simple decodable book, you’ll need to teach the high frequency words that are also included in that book.

For example, if your child is learning to sound out CVC words, the book’s text may look like this:

“The cat is big.”

To read the sentence, your child needs to know the high frequency words THE and IS.

THE is not a word your child can sound out; you will need to teach him/her to memorize the tricky parts. IS is not as tricky as you might think; just teach your child that the letter S has two sounds: /s/ and /z/, and in the word IS it makes the sound /z/.

What sight words should we teach preschoolers?In general, I don’t think you should teach preschoolers to memorize words. However, it’s helpful to know a small set of words “by sight” so that your child can start to read decodable books.

Readsters recommends teaching these sight words to pre-readers:

theaItoandwasforyouisofHOW should we teach introduce sight words in preschool?While flash cards can be helpful for review, that’s not how we should introduce sight words. I’ve got a whole post about how to teach sight words, and I recommend checking it out here.

Here’s a quick summary of my approach:

Assuming your learner has phonemic awareness and letter-sound knowledge, you’re ready to begin. (Not sure about the phonemic awareness? Give this free assessment.)Name the new word, and have your learner repeat it.Name the individual phonemes (sounds) in the word. For example, in the word is, there are two phonemes: /i/ and /z/.Spell the sounds. Call attention to any unexpected spelling. In is, we spell /i/ with i and /z/ with s.If possible, have your learner read related words. Has and his are great words to read alongside is because they are short vowel words with an s that represents the the /z/ sound.Have your learner read connected text. Connected text can be decodable sentences or books.I recommend my high frequency word lessons and books which can be used with kids as young as preschool.

You’re invited to check out the rest of this series!Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon

The post Preschool Sight Words appeared first on The Measured Mom.

October 31, 2021

Science of Reading Q & A: #2

What should you do with all your leveled books? Is there any place for them in a science of reading classroom? What should you do when students just can’t master their short vowel sounds? When do you move on? And what about assessing struggling readers? Should you use Fountas & Pinnell’s benchmark assessment to find their reading level? Get answers to these questions and more in this science of reading Q & A episode!

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, and welcome to our second Science of Reading Q & A! In our last episode, I answered some questions that some listeners had after I gave an online workshop with my colleague, Becky Spence. These are also questions that were submitted to a survey.

My first question was from someone who runs a small village school in India. They're teaching English as a second language and the students are really struggling with short vowel sounds. They asked, "At what point do you just say that's good enough and move on so they can continue to make progress, because they're really struggling to distinguish between the short vowel sounds."

One thing I recommend doing as you're teaching those vowel sounds is to teach some kind of visual cue for each vowel sound. So /a/, you might have your hand making the shape of an apple: /ă/, apple. Or you could have an apple that you're about to eat, /ă/. And then for /ĕ/, maybe you'll have your fingers on the side of your mouth. For /ĭ/, you might be itchy in your shoulder. /ŏ/ you might have your finger on your chin as your mouth is open very tall: /ŏ/. For /ŭ/, you might have a fist on your stomach: /ŭ/.

I think it's really good to have these consistent motions that you make when you teach those short vowel sounds. So find something that you think is really going to work for your students and use those motions as you have students practice the sounds.

At the beginning of each of your lessons, I would have flashcards that have those short vowel letters and you have them practice the sound. So if you have a "U," for example, they would say, "U says /ŭ/." And then when they say the /ŭ/, they're putting their fist on their stomach or whatever it is that you have them do for the /ŭ/ sound.

Something else you can do is you can have little tents. So you take little index cards, fold them over, and each one has a vowel on it, A, E, I, O, U. Then you have this warmup activity before you do your other stuff in which you say a short vowel sound or a short vowel syllable - something that contains that short vowel. Then students repeat the sound and then find the little tent that corresponds to it.

For example, you could say, "Eyes on me, the sound is /ă/. Repeat, /ă/." Then they find their little tent, the one that has the A on it, and they hold it up and they all say together, "A says /ă/." You can do this with words too, once they're ready. Initially, if they're still struggling to tell the difference, I would stick with just saying the sound.

When they're ready for words, you could say, "Eyes on me. The word is cat. Repeat. Cat." Then they would find the card again and they would hold it up. And they would say "A says /ă/." That's obviously more advanced, but I would definitely incorporate some kind of short vowel review at the beginning of all your lessons, if they still don't have it, because I do know that at some point you need to move on.

Another question was, "I'm a grade one leveled literacy intervention teacher using Fountas and Pinnell. I've always questioned the suitability of the program for struggling readers. My question is, how do you assess your students' reading level? Our struggling students struggle with the retelling of the story and the comprehension questions."

Okay, really good question. I would say, first of all, I wouldn't necessarily test the reading level with struggling students because you would have to ask what's the point of that? What's that going to tell you? Reading levels are somewhat arbitrary, especially at the very beginning, like A, B, C, D E F, G. I wouldn't even use those if you could. Avoid it because they're just testing how well students use the pictures because most of those early books don't even require them to have a lot of phonics knowledge.

Instead, I would find a good phonics assessment and I would test their phonics knowledge. That's what I would do. Now in terms of what assessment to give them for comprehension, I don't have a suggestion for that right now, but I would join one of the big science of reading Facebook groups and ask there because there's always lots of people with suggestions.

Another listener said, "I currently teach reading to four to six year olds. We use Reading A-Z decodables and high frequency word books. Students start in leveled high frequency word books and progress quickly. Then when their high frequency words are mastered, we move them to decodables. Would the science of reading suggest starting straight away in decodables, and then moving to high frequency word books? Or not incorporating the leveled readers at all?"

Great question! I would say definitely start with the decodables, and you have to really ask what the point of those high frequency word books are and how students are figuring out the words. If they're figuring out the words by context and picture clues, then you are bypassing orthographic mapping, and you're actually stunting their reading growth. And they're going to probably have a problem later. Now some kids will be successful with this, but it's really not helping anyone make a lot of progress, because what you want is for them to connect the sounds to the letters, and they're not doing that if they're just using picture and context.

You can teach high frequency words within the decodables. So you teach the high frequency words that the decodables include. There's nothing wrong with teaching about 10 high frequency words to begin with by sight - memorization - just to get them started, but that's not how we want to continue. We want to mostly teach high frequency words within the context of phonics, even if the words aren't entirely regular. So I hope that helps. Go ahead and drop me an email, anna@themeasuredmom.com, if you have more questions.

Along that same line, "What do I do with all the leveled books in my room? Can I use them, but follow the science of reading?"

This is such a hard question, because if you have been doing balanced literacy for a long time, you have a lot of leveled books and they are not cheap! I know because I used to collect them myself. That's hard because if you really understand the science of reading, you realize that beginning readers, for sure kindergarten and early first grade, really need to be reading decodable books. They should not be reading the predictable leveled books, unless they're at a very, very early stage and they're working on concepts of print, like voice to print matching. But I'm quite sure that that's not what this teacher meant.

I watched a webinar from Linda Farrell and Michael Hunter recently. It was on YouTube and I will leave a link to it in the show notes. They're both from Readsters, and they have an excellent website and resources, with lots of great articles. They had this whole webinar all about leveled and decodable books. It was SO helpful and I highly recommend watching it.

In there, they talked about how you really should not be using leveled books before level J to teach early reading, but you could keep those books and use them with English language learners as read alouds and as a way to build vocabulary. So you don't necessarily have to throw them all out! You can certainly have them for students to enjoy on their own, but you do not want to use them to teach beginning reading. That webinar is going to give you a lot of help.

Another question, "Should we introduce digraphs, even though all letter sounds are not solid?"