Anna Geiger's Blog, page 23

January 17, 2022

What order should you teach phonics skills?

We can all agree that teaching phonics is important.

But there are SO many skills.

Which ones should we teach? And in what order?

Today we’ll look at my recommended order for teaching phonics skills.

Before we get into my recommended order, I want to be clear about a few things.

There is no perfect order for teaching phonics skills.

When choosing your own scope and sequence (mine or someone else’s), do make sure the scope and sequence has the following characteristics (from Wiley Blevins in his wonderful book, A Fresh Look at Phonics).

Qualities of a strong phonics scope and sequence

It moves from the simplest to most complex skills and builds on previous learning.It allows words to be formed as soon as possible.It teaches more common sound-spellings before less common sound-spellings.It separates easily confused letters and sounds.My recommended sequence does all of the above.

I’ve chosen to break this down into three levels. Technically these levels are kindergarten, first, and second grade, but students need to start where they ARE.

This may mean that you have a group of first graders who are starting in the middle of Level 1. You may also have kindergartners who move so quickly that they’re learning Level 2 skills before the kindergarten year ends.

I recommend assessing phonics knowledge with a quality phonics assessment (coming in a month or two!) and then forming small groups based on phonics knowledge.

Over the years I have recommended slightly different sequences for teaching consonant and vowel sounds.

However, since I am using the following sequence when writing my series of decodable books (coming soon!), this is what I recommend.

(Again, this isn’t sacred! Adjust accordingly, as long as you follow Wiley Blevins’ recommendations above.)

Consonants, short vowels, and common digraphs / VC and CVC wordss, j, a, t, p, m, d, c, h, r, n, i, b, f, g, k, -ck, o, l, e, sh, th, u, w, ch, wh, x, y, z, qu

Remember that digraphs are two letters that make one sound. The digraphs in the above list include -ck, sh, th, ch, and wh. “Qu” is technically a blend, but I usually include it with digraphs.

As you are teaching the above letters and sounds, teach your students to read VC (vowel-consonant) words like am and if. Teach them to read CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words like cat and pig. Since they are learning digraphs, you will also teach them to read words like rack and chin.

(We have a huge collection of free printables for teaching CVC words, which you can find here.)

FLOSS ruleThe floss rule says that when you spell the /f/, /s/, /l/, or /z/ sound after a short vowel in a single-syllable word, you usually double the final consonant.

“Floss” is a great way to remember this rule, but it doesn’t include the letter z. I love what Emily Gibbons does. She calls it “Zee floss rule” in a silly accent.

Examples: puff, fell, miss, jazz

(Check out my free FLOSS rule game here).

Simple 2-syllable compound wordsTeach your students not to be afraid of big words! Now that they can read CVC words, know common digraphs, and understand the FLOSS rule, they can read compound words like catnip and bathtub.

Beginning BlendsThese days some voices are telling us not to teach blends. One concern (as I understand it) is that we don’t want to teach blends as single chunks; children should simply sound out blends the way they do other letters – sound by sound.

I agree that we need to be careful; blends (sometimes called consonant clusters) are not digraphs. Each letter has its own sound. And it’s absolutely NOT necessary (indeed, it would be a huge waste of time) to teach each blend on its own.

But I still believe that specifically helping students notice blends, read words with blends, and spell words with blends, is good practice.

L-blends: bl-, cl-, fl-, gl-, pl-, sl-

R-blends: br-, cr-, dr-, fr-, gr-, pr-, tr-

S-blends: sc-, shr-, sk-, sm-, sn-, sp-, squ-, st-, sw-

-lp, -st, -ct, -pt, -sk, -lk, -lf, -xt, -ft, -nd, -mp, -st, -lt, -nch

(You can check out our free printables for teaching blends on this page.)

-ng & -nk endingsThese are often called “glued” or “welded” sounds. Consider teaching them in word families.

-ing, -ang, -ong, -ung, -ank, -ink, -onk, -unk

Long vowel/ending blend word familiesIn my Orton-Gillingham training these were called “kind, old words.” In these word families, the vowel makes a long sound instead of its expected short sound.

-ild, -old, -ind, -olt, -ost

Open & Closed syllable typesBelieve it or not, you can teach this concept in kindergarten. Teach your students that when a syllable ends in a vowel, the door is open. The vowel shouts its name through the open door and makes its long sound (no, go, we, be, etc.).

When a syllable ends in a consonant, the vowel makes its short sound (cup, hen, sit, etc.).

Now that students understand open and closed syllables, they’re ready to practice syllable division – if that’s the route you want to go. This is a big thing in the Orton-Gillingham approach, but other approaches skip the division rules and teach a more loose and flexible approach to dividing words into syllables.

I don’t think that one way is necessarily superior to the other. If you decide to go the OG route, you’ll find syllable division principles below.

VC/CV syllable divisionHelp your students identify the vowels and then label the consonants between the vowels. They can then divide the word, identify the syllable types, and read.

This is NOT what students need to do every time they come upon a new word in their reading (absolutely not!), but the skill of identifying syllable types will come in very handy as they start to encounter longer words in reading and spelling.

Sample VC/CV words: napkin, muffin, bandit, instruct

V/CV and VC/V syllable divisionThese are a bit tricky because there is no set rule to tell us whether to divide after the first vowel or after the consonant.

However, the V/CV pattern is present about 75% of the time, so students should try that one first. After identifying the syllable types and reading the word, they can adjust accordingly.

V/CV examples: robot, tulip

VC/V examples: denim, visit, credit

Teach your students that the suffix -ed can represent /t/, /d/, or /id/.

I should note that in my decodable books I include words with the “ed” ending earlier in the sequence. That’s because books get very stilted when you try to avoid the “ed” ending.

In a decodable book I was writing the other day I wrote “Fox hugged his sis.” Otherwise I would have had to write “Fox did hug his sis,” and that just sounds weird.

CVCE (Magic e) wordsSilent e has many uses. In Magic e words, it makes the preceding vowel say its long sound.

Sample words: bake, dime, theme, cute, hose

CVCE syllable typeNow that students can read CVCE words, they can read longer words that include this syllable type.

Examples: classmate, handmade, timeline

(This site is bursting with CVCE printables! Check them out here.)

Suffix -ingTeach your students that when adding this ending, they either double the final consonant, drop the e, or make no change to the base word.

Less common digraphs and trigraphswr-, kn-, ph-, gh-, gn-, -mb, -tch, -dge

Common vowel teamsVowel teams are two or more letters that combine to represent a vowel sound. One or more of the letters may actually be a consonant (as in the vowel team igh).

ee, ea, (eat), ai, ay, oa, ow (grow), oe, igh, y (dry), oo (zoo), oo (good)

(So many vowel team goodies on this site – check them out here.)

Vowel team syllable typeStudents can divide longer words into syllables and read words with the vowel team syllable.

Sample words: hayseed, firewood, raindrop

Spelling with -k, -ke, and -ckWhen you hear the /k/ sound at the end of a one syllable word, it is spelled with a k if it is preceded by a vowel that says its name (CVCE), is preceded by a double vowel, or is preceded by a consonant. The sound /k/ is spelled ck when preceded by a single, short vowel.

Sample words: bake, beak, ask, back

R-controlled vowelsSome phonics scope and sequences introduce r-controlled vowels much earlier, and that’s completely fine. I chose to include them here because we are also focusing on syllable types, and we don’t want to overload students with all the syllable types too quickly.

Important: when counting phonemes (individual sounds) in words, count an r-controlled vowel as a SINGLE sound. It feels a little weird to do that, but it’s common practice.

er, ir, ur, ar, or

(You can find our r-controlled freebies here.)

R-Controlled vowels syllable typeNow students can read words like barnyard, mutter, and western.

More r-controlled vowels-air, -are, -ear

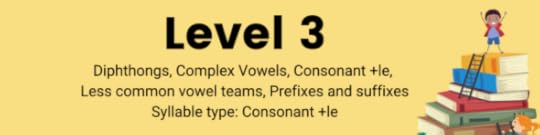

Diphthongs and complex vowels

Diphthongs and complex vowelsA diphthong is a vowel sound that glides in the middle. The mouth position shifts during the production of the single vowel phoneme. There is disagreement about which vowel combinations are diphthongs. For our purposes, I include the following.

aw, au, a (as in calm), oi, oy, ou, ow (as in cow)

Diphthong syllable typeNow students can read words like cookout, jawbone, and powder.

Note: Many programs include the diphthong syllable type WITH the vowel team syllable type, for a total of six instead of seven syllable types. I’ve done that myself with some printables I’ve made. It’s fine.

V/V syllable division principleThis is the least common syllable division occurrence. If you teach syllable division principles, now is a good time to teach this one.

Sample V/V words: cameo, diet, and fluid.

Consonant-le endingThis is sometimes referred to as the final stable syllable.

-ble, -dle, -fle, -gle, -kle, -ple, -tle, -zle

Consonant-le syllable typeStudents can read words like bottle, feeble, jingle, and turtle.

Words that end with y as long eExamples: crispy, giddy, tardy, stubby

soft and hard c and gWhen c is followed by e, i, or y, it usually makes its soft /s/ sound. When c is followed by any other letter, it usually makes its hard /k/ sound.

When g is followed by e, i, or y, it usually makes its soft /j/ sound. When g is followed by another letter, it usually makes its hard /g/ sound.

Soft c words: brace, dance, rancidHard c words: cage, cramp, cupSoft g words: age, giant, gerbilHard g words: dog, gift, goatLesson common vowel teamsui, ue, ew, eu, eigh, ei (vein), ei (ceiling), ie (thief), ie (pie), ey, ea (head), ea (break), ou (youth), y (gym)

Words with the schwa soundThe schwa is a muffled vowel sound that is only found in unstressed syllables. In fact, the schwa is actually the most common vowel sound of all. When students are decoding multisyllable words and the word doesn’t sound right, they should adjust the vowel sound in the unaccented syllable. It may just be a schwa!

Remember that the schwa sound is sort of a short u sound (as in tandem) or a short i sound (as in tablet).

Students should already be familiar with schwa, but it’s good practice to address it specifically.

Sample words: abode, bacon, happen, salad, trial

Extra spellingsYou have likely already taught these incidentally throughout the years, but just in case these skills need focused attention, you can teach them now.

ch (school), ch (machine), s – /z/

Words with prefixesun-, re-, in-/im-/ill-, dis-, en-/em-, non-, in-/im-, over-, mis-, sub-, pre-, inter-, fore-, de-, trans-, super-, semi-, anti-, mid-, under-

Words with suffixes-s/-es, -ed, -ing, -ly, -er/-or, -ion/-tion, -ation/-ition, -ible/-able, -al/-ial, -y, -ness, -ity/-ty, -ment, -ic, -ous/-eous/-ious, -en, -er, -ive/-ative, -ful,-less,-est

Whew! That was a lot! No need to copy it all down … join our email list below and get a FREE scope and sequence chart!

Download your free scope and sequence chart!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

Check our the rest of our phonics series!

Part 1 Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon

The post What order should you teach phonics skills? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

January 16, 2022

Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #6: We can teach phonics AND language comprehension

TRT Podcast#62: Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #6 – You can teach phonics AND language comprehension

Fountas and Pinnell caution against focusing “only on accuracy and decoding.” If we do that, they say, students may not understand that what they read must make sense. But the science of reading community doesn’t advocate phonics alone. Far from it!

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here! Welcome to Triple R Teaching, Episode 62. This is actually the sixth episode in our reaction series to Fountas & Pinnell.

So you know that Fountas and Pinnell are big literacy names in the United States, especially that they have created kind of an empire around their approach to teaching beginning reading instruction. They're the creators of the guided reading levels. They came out with their first book about guided reading back in the nineties and put out the second edition in 2017.

They have been holding fast to their beliefs about how beginning reading works, what materials we should use, and what approach we should take when teaching beginning readers. That has a lot of people in the science of reading community frustrated because it feels like Fountas and Pinnell aren't listening to what we've learned from research. They have, as one person said, "stuck their feet in concrete, and they're not budging."

They recently put out a "Just to Clarify" blog series, in which they answer ten questions or criticisms of their work. What we're doing in this series on my podcast is responding to each of those short audio blog posts that they have created.

Today we're going to look at question six and that was, "Could you speak to the role of phonics and teaching children to read, and clarify your approach to phonics instruction?"

Before I keep going I want to note that you might hear some coughing in the background, sorry about that. We've had a cold going through all my kids and I've had a kid home for a week at a time for several weeks. Right now it's my 11 year old and he's in another room working on some homework to catch up, but there's still some coughing coming in from over there. So hopefully you can ignore that and let's talk about phonics and Fountas and Pinnell.

As my kids would say, it's a little "sus" that Fountas and Pinnell are talking this much about phonics, because it's my understanding that it wasn't right away that they had this big portion of their program devoted to phonics. I'm pretty sure that was not part of the first version of their reading program at all. I've looked and looked to try to find dates for when all the pieces came out and I can't seem to find it. So I am ready to be corrected if I'm wrong, but I have to question any acknowledgement on their part that phonics is important if it wasn't something that came with the original program.

In a recent episode when I talked about guided reading and some of the problems with the way that Fountas and Pinnell use that, I talked about this big, fat book I have of theirs about guided reading. It's 600 pages, and it has fewer than five pages that even address phonics.

With early readers, phonics has got to be a huge piece of what we do with them, right? We need to build the phonemic awareness foundation and then teach phonics and teach them to decode words so that they have that first important piece when it comes to the Simple View of Reading.

Let's listen in to how Fountas & Pinnell answer the question about their beliefs regarding phonics: "Phonics is essential for reading and writing, and research certainly supports this, but phonics is not the end goal of literacy or becoming literate. An overarching principle in literacy learning is that the purpose of reading must be constructing the meaning of the text using language and print. When the focus is only on accuracy and decoding, young readers may not understand that the purpose of printed language is to make sense and to convey a meaningful message. They may give so much attention to decoding that they have little attention to give to thinking about the meaning, the language, and the messages of the text.

"In the pursuit of accurate reading, teachers must, of course, focus on helping children with decoding. But instruction must also include a focus on thinking within, about, and beyond the text. Therefore, an effective literacy design includes explicit phonics instruction and takes place within a comprehensive approach so that learners have ample opportunities to apply their understandings as they engage in meaningful reading and writing. The bottom line is, we believe there cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach to teaching phonics or phonemic awareness."

Okay, so let's take this apart. The very first thing that Irene Fountas says is, "Phonics is essential for reading and writing." We agree, right? Absolutely agree!

But then she adds a but, "But phonics is not the end goal of literacy or becoming literate." We can agree with that too, right? The goal of reading is reading comprehension, but as we learned with the Simple View of Reading, reading comprehension cannot occur without decoding and language comprehension.

She goes on to say that when the focus is only on accuracy and decoding, young readers may not understand the purpose of printed language is to make sense and to convey a meaningful message.

This is often the complaint lodged against science of reading advocates, that when you're so focused on phonics, kids aren't going to understand that the text is supposed to mean something. But you CAN do both and certainly if you take a look at Scarborough's Reading Rope, which shows us all the subskills involved in language comprehension and word recognition, you would know that the science of reading community is not at all against language comprehension. It's an important piece!

It's just that on the other side, the balanced literacy side, phonics has been notoriously unrepresented. It's often included, but in a haphazard way.

So this is a concern that the science of reading community has, therefore it can feel over-emphasized, but it is definitely not the end all and be all. I don't think anyone in the science of reading community would claim that to be the case.

In the second paragraph of her response, Fountas says that instruction must also include a focus on thinking within, about, and beyond the text. Agreed. Absolutely!

We do a lot of that in the science of reading structured literacy classrooms using interactive read alouds, which I know Fountas & Pinnell also promote. It's where the teacher reads a thoughtful piece of literature to the class and has planned places to stop and have discussions about vocabulary, using reading comprehension strategies, and so on. So we can agree on that.

I think the problem is that Fountas and Pinnell would believe that if you're using decodable books to teach reading, then you can't focus on comprehension. They might say that you can't help students realize that we're not just word calling, we're actually trying to make sense of the text. We addressed that in a previous episode, but I think it's worth repeating again here.

It really all comes down to the texts that you have students use, because Fountas and Pinnell can say all they want that phonics is important, that we need to teach phonics, and that we'll have these phonics lessons. But then if they're over here giving guided reading lessons with leveled books that do not allow students to practice the phonics knowledge that you've taught them, the students are not going to use it. They can't apply it because you're not giving them opportunities beyond lists of words in their phonics lessons.

I know this is really hard, but if you're trying to move from a balanced to structured literacy approach, you have to let go of this idea that teaching kids to sound out words teaches them to word call.

Now, could that happen? Could you have somebody who's just calling out words and not making any sense of it? Well, sure, but the problem isn't phonics, the problem is that they need some language comprehension instruction, whether that's background knowledge, vocabulary, or so on. Let's not blame phonics.

Let's remember that we teach phonics to help students identify the words, and we also teach language comprehension. We make sure that students have consistent opportunities to apply that phonics knowledge with the books they read and not practice three-queuing in leveled books.

I want to address one more thing in Fountas's response to this question and that's where she says the bottom line is that there cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach to teaching phonics or phonemic awareness.

So I agree with that. I don't think there's one program that works for everyone and the teacher is important here in this equation. Success with the program depends very much on the teacher's implementation and interaction with students and so on, which we will be getting to in another episode.

But I don't want to use this as a cop out. I wouldn't want to say, well, there's no one-size-fits-all approach, so you can use whatever you want. That's not true!

Now let's look in terms of what research says about phonics instruction and what it should be. Well, we know it should be systematic. We know it should be sequential. Some people say it should be synthetic. Synthetic phonics is when you sound out all the letters in a row, and there's also analytic phonics. I believe that analytic phonics is more where Fountas and Pinnell are coming from in their program. It's more word family based and more noticing the chunks of words. I'm not a hundred percent sure on that; I just know I've heard that from a couple of people.

So I think we can agree that there's no one program that serves everyone perfectly, but that doesn't mean that there aren't certain criteria we should look for when finding a good phonics program.

In the show notes I'm going to share with you an article by Wiley Blevins. He's a big name in the phonics community. I love his books, I think I have them all. He wrote something called, "Phonics: Ten Important Research Findings." I think that's really good to check out. It will help you consider the research as you're choosing your own phonics program. If I can find any other helpful posts from him, I'll also link to those in the show notes.

Thanks for listening to my reaction to Fountas and Pinnell's words on phonics. You can find the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode 62. See you next week.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Emily Hanford’s response: Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Mark Seidenberg’s response: Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

Wiley Blevins: Phonics: 10 important phonics research findings

Recommended book by Wiley Blevins: A Fresh Look at Phonics

Free ebook from Sadlier Phonics (written by Wiley Blevins): Seven Characteristics of Strong Phonics Instruction

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #6: We can teach phonics AND language comprehension appeared first on The Measured Mom.

January 10, 2022

What every teacher should know about the reading wars

The reading wars are alive and well. Should you pay attention or stay out of the debate?

Here’s what every teacher should know about the reading wars.

As a mom of six, I’ve refereed countless arguments.

It wasn’t much different in the classroom.

I loved my years as a classroom teacher, but I remember how incessant student squabbles can be.

The truth is … I’ve heard enough bickering to last the rest of my life.

You too?

But alas … the bickering is all around us.

If you teach reading, it’s impossible to avoid the reading wars.

We find arguments on Twitter, in Facebook groups, and in blog comment sections.

I don’t know about you, but sometimes I just want to bury my head in the sand.

As tempting as it may be, we shouldn’t put our heads down and keep teaching without being aware of the current debate.

There’s much to learn.

There’s much to say.

1. The reading wars have a long history.

1. The reading wars have a long history.AND IT ALL COMES DOWN TO PHONICS

In my podcast about the reading wars, I quoted David and Meredith Liben.

“The disagreements over the rightful role, intensity of focus, and approach within the phonics universe is a central part of the reading wars.”

And that’s because the phonics discussion leads to difficult questions …

How structured should the teaching of young children be?How much should children practice new skills?How and when should we assess?Who’s accountable for children learning to read?The phonics (sound it out) approach was pitted against the look-say (memorize the whole word) approach for decades – in fact, much of the early 20th century.

THE DEBATE GOT HEATED IN THE MID 1950’SThe reading wars really ignited when Rudolf Flesch published his incendiary book, Why Johnny Can’t Read, in 1955. In that book he blasted the whole word approach.

Jeanne Chall

Jeanne ChallProminent researchers such as Jeanne Chall joined the discussion, and they found that systematic, sequential phonics instruction produces better outcomes in word recognition in the early grades and even helps improve reading comprehension in the later grades.

The publication of Jeanne Chall’s book, Learning to Read: The Great Debate, should have ended the reading wars.

But in spite of what she shared from research…

Whole language (NOT systematic, explicit phonics instruction) became a popular approach.

WHOLE LANGUAGE BECAME POPULAR IN THE 1970’SThe whole language philosophy says that learning to read is very much like learning to speak. It says that if we surround kids with lots of quality literature, lots of print on the walls, and lots of reading aloud to them, they’ll pick up reading without a lot of explicit instruction.

Whole language isn’t technically against phonics, but it advocates more of a “teach it as needed” approach.

The wars raged on.

In 2000, the National Reading Panel completed its three-year study of the research surrounding reading. They recommended explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, systematic phonics instruction, methods to improve fluency, and ways to improve reading comprehension.

BALANCED LITERACY BECAME POPULAR IN THE LATE 1990’SAround the time that the NRP released its report, balanced literacy was born.

Balanced literacy has a million definitions, but we can all agree that it was an attempt to end the reading words between the whole language and phonics camps.

Balanced literacy isn’t all bad. Balanced literacy teachers tend to be dedicated educators who are passionate about quality literature; they work hard to help their students develop a love of reading.

But there’s a problem.

And it’s a big one.

2. The current debate is between balanced and structured literacy.

2. The current debate is between balanced and structured literacy.The name “structured literacy” was coined by the International Dyslexia Association in 2016.

Structured literacy is a systematic and cumulative approach that teaches the critical elements (phonemic awareness, phonics, and the rest) through explicit instruction and with diagnostic teaching.

(It that sounded like a foreign language, check out my series about structured literacy. I break it all down.)

Those in the structured literacy camp are often referred to “science of reading” advocates.

The science of reading is simply the collection of research related to how we teach reading.

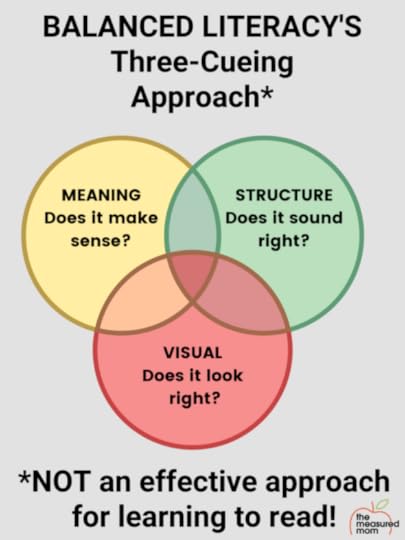

Structured literacy advocates (sometimes called the science of reading crowd) have quite a few problems with balanced literacy, but the biggest issue by far is with three-cueing.

In fact, the recent article that reignited the reading wars focuses on three-cueing itself. (If you haven’t read it, check out Emily Hanford’s article: “At a Loss for Words.”)

Structured literacy advocates claim that three-cueing actually teaches bad habits and guessing, and that early readers need to begin their reading with decodable books so they can practice the phonics knowledge they’ve learned.

Despite research showing that three-cueing is unhelpful at best and damaging at worst, Fountas and Pinnell are still holding fast.

Meanwhile, in a recent article, Mark Seidenberg notes that “the best ‘cue’ to a word is the word itself.”

3. The science of reading camp isn’t JUST about phonics.

It feels like the science of reading is all about phonics – and nothing else.

After all, that’s where the discussions tend to go.

But SOR advocates know that we need both decoding ability AND language comprehension to be achieve the goal of reading: reading comprehension.

The reason the discussion revolves around phonics is because it’s taught in such a haphazard way in many balanced literacy classrooms.

It’s the thing that needs the most pressing attention.

If you doubt that comprehension gets attention in the science of reading camp, check out this post about Scarborough’s reading rope.

4. The science of reading is not a fad or pendulum swing.It seems that every time I read a heated Facebook thread about the science of reading, someone always comes out and says something like this:

“I’ve been teaching for 35 years, and this is just the pendulum swinging back. It will swing again in a few years.”

Except … the science of reading isn’t just a bunch of people with opinions (even though we all have them). It’s the body of basic research about how we learn to read.

That research is going to be refined and added to, but it’s not going to disappear.

5. It’s every teacher’s responsibility to keep learning.You may have heard the rallying cry of the science of reading crowd: “Know better, do better.”

I used to hate that.

It made me feel like they were sitting up on their high horse, looking down at me (I was still firmly entrenched in balanced literacy).

However, as I began to understand how wrong my approach was, I felt guilt and sadness for the students I hadn’t helped. I now realized that “know better, do better” is what we say to encourage ourselves to keep going … to do better for our current and future students.

Are you ready to learn?

Joining a science of reading Facebook group is a good place to start. The drama can get intense (ugh), but these groups often share links to free and inexpensive trainings that will help you on your journey.

Just like any setting, those groups are full of people with their own opinions (generally expressed IN ALL CAPS) that may or may not be backed by research.

It’s your job to do your own study.

Here are good places to start!

Listen to my podcast series: Science of Reading Bootcamp.Read Know Better, Do Better, by David and Meredith Liben.Read Shifting the Balance, by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates.Get on the waitlist for my online course, Teaching Every Reader.Put more books on your reading list: Books to read on your science of reading journeyI’ll close this post with a quote from Cecilia Magro, one of many dedicated online educators.

Stay tuned for the rest of our 10-part phonics series!As teachers, we need to be informed on research, how the brain learns, and critically analyze the practices we use in our classroom and decide if we need to change. When we know better, we do better.

Cecilia Magro, I Love 1st Grade

Part 1 Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon Coming soon

The post What every teacher should know about the reading wars appeared first on The Measured Mom.

January 9, 2022

Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #5: Here’s why you SHOULD use decodable books

TRT Podcast#61: Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #5 – Here’s why you SHOULD use decodable books

Fountas and Pinnell aren’t moving when it comes to decodable books. They believe these books are contrived and that decodable books teach children that their reading doesn’t have to make sense. But decodable books are exactly what our beginning readers SHOULD be reading. Here’s why.

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello and welcome! You are listening to Triple R Teaching, Episode 61. This is the fifth in my series of reactions to Fountas & Pinnell's "Just to Clarify" blog series, in which Gay Su Pinnell and Irene Fountas, two popular figures in literacy in the United States, react to criticism of their work.

They've been very prominent since the '90s, and many consider them the founders of the balanced literacy movement. They might not agree, but that's what many people would say. They promote teaching reading using leveled texts. That's just one part of their overall program, but that is a big piece of it.

Today's question is, "In your view of early literacy development, what is the role of decodable texts?"

They have a long response here, so I'm not going to play that for you, but I'm going to take out pieces of it. To summarize, they're not fans of decodable text. They do not feel that those texts are useful to kids. But let's take out some pieces.

First of all, they tell us that back in the 1800s, kids did use decodable text, and yet, the literacy rate was below 50%. I'm not going to try to speak to that specifically because there are a million other factors in there, for one, the idea that many kids couldn't even go to school because they were helping on the farm. I think we need to really look into many reasons about why the literacy rate was low. So we won't use that as support for their argument.

They talk about how, in the '50s, there were a lot of sight word books using the look-say method. I've talked about that before when I've talked about the history of the reading wars and how there was this switch to the memorizing of lots and lots of words. I've talked about how that's a bad thing, because that's not how your brain works. We don't store up thousands and thousands of words as holes. Rather, the way that we learn to recognize words is by connecting the phonemes to the graphemes, through a process called orthographic mapping.

They don't talk about that here, but they just address those two things. That in the past, kids used decodable books back in the 1800s, but the literacy rate was low. We cannot connect the two, necessarily. Then they address the idea of these look-say books, where the story would not be very exciting, right? "See Jane run," and so on.

Their point of doing this is to let us know that both of those options, those decodable books from the 1800s, and the look-say books from the '50s, those are contrived, as in they're not really real. The books are just written for a particular purpose, and they aren't real stories. Kids cannot engage with them.

I would like to counter with the argument that leveled books, the early books that they provide for our earliest readers, are also contrived.

It really isn't until students get up to Level I or J that the books start to sound more like regular books. Those early books have patterns so students can easily pick up on them. They have pictures that match the text so that you can easily get your cue. Those books are also written for a specific purpose.

I used to think this! I used to think that decodable books weren't real books, but leveled books were. Now I understand that both are contrived, but for different reasons. I'm going to quote now from their response, in which they're describing the problem with those other options, the decodable books and the look-say books: "In both of these approaches, there was something wrong with the language in these books because children were encouraged to read, and not really to think of the meaning. And in some cases of some texts, the meaning was so elusive that almost no one could make sense of it. But pre-teaching phonetic elements and patterns then resulted in these extremely contrived texts."

Okay. So this was something I could've said, word-for-word, back when I was a balanced literacy teacher and really was against decodable books. And I understand why some people might say this, because some decodable books are bad. They just are; some are not good! If they don't make any sense, and they're so stilted because they're trying to fit in all these decodable words that you can't even tell if you read it right, because it doesn't sound like we talk, then that's a problem. Decodable books should sound like we talk. If that means you have to add a few words that are not decodable, I think that's a good trade-off.

Wiley Blevins has said he'd rather have a book, I can't quote him exactly, but it was something like, "I'd rather have a book that's 60-65% decodable than 80% or more, if it's going to make sense." So I'm not of the mind that every book should be 100% decodable - I don't agree with that. The books we read should make sense because we want students to be able to go back and correct it if it doesn't make sense.

So I guess, there I'm just acknowledging the concern that Fountas & Pinnell have. It is a real concern that kids aren't making meaning from decodable texts. So I think we need to be very conscious of this and choose quality decodable books. I actually spent a long time curating a big list of the decodable books that I think are the best. It's on my website. I will link to the post in the show notes, so you can check it out.

The next part of their blog is interesting. They write,

"All of the contrived texts were created by adult scholars who based their work on assumptions about their own material reading. They assume that reading means recognizing or sounding out the words or memorizing sight words. And that leads to the assumption that children should learn the words first or the letter-sound patterns first, and then read them in words strung together. This could, with some children, lead to the confusion that they're reading nothing more than a list of words."

All right, let's unpack this. Back in the 1800s, and back in the '50s, I'm not sure exactly what was known about how the brain learns to read. It may be entirely possible that people were basing their reading material, and how they thought reading worked, based on their own personal experience.

I think it's fair to say that when Marie Clay was developing her own system, her ideas about three-queuing, she based that on observations of kids. She wasn't basing it on a scientific study, not that I know of. So I think it's fair to say that maybe all of these people had misplaced ideas about why they chose the texts that they did.

However, now we know!

We have a good forty years of research that helps us understand how children learn to read. We know that for orthographic mapping - instant recognition of words - to occur, students must be good at phonemic awareness and phonic decoding. They cannot become good at those two skills unless they're actually sounding out words in the books they read.

Fountas & Pinnell say the concern is that if they're reading these decodable books, they'll think reading is just saying the words.

If you have a quality decodable book that does tell a story, even if it's through the pictures, and has text that kids can sound out, you can certainly talk about the story. I don't recommend long lists of words that don't make any sense. Certainly that's good practice, but I think it needs to be applied in a meaningful story, which you can actually find in decodable books.

Now, is the book going to be a great piece of literature? No, that's not the purpose. Fountas and Pinnell have something right here, decodable books are contrived. They are. They're created for a specific purpose, to help beginning readers learn to sound out words. That's the whole point of them! BUT creative authors and illustrators can create engaging decodable books. If you check out that blog post that I'm going to share in the show notes, you'll find out how true that is.

I find it very telling that in this blog post by Fountas & Pinnell, they do not allow for decodable books. Basically they're saying that their books are decodable because of the consistent patterns. I cannot agree with that.

Let's listen in to a little of their audio blog post about the types of books that they recommend you use instead of decodable books:

"What we recommend is easy texts with many words that we could call “decodable” because they are regular phonogram patterns such as, “can,” “see,” “be,” mixed with enough sight words that the language sounds a bit like talking. It isn't really exactly the same as talking, but it makes sense to kids. And good stories with interesting illustrations, fiction and non-fiction, so that they have the opportunity to behave like readers and choose books and enjoy books. At the same time, we sometimes have a repeating pattern of a sentence structure to give them more practice. In the books that we have produced, we put in these recognizable repeating elements, but the reader does not depend on or memorize the books. It's a real story, and they're decoding as much as they know and have been taught in phonics lessons in these easy books."

So there're some problems with that, quite a few problems.

First of all, a decodable book is a book that includes phonics patterns that a student has been taught. So I totally understand that "see" is decodable and "be" is a decodable word, but if you haven't taught them that "ee" represents the /ē/ sound and that open syllable words, like "be," have a long vowel sound at the end, then it's not decodable to the child.

Now can you teach a few sight words without getting to the phonics pattern? Absolutely. I've talked about that in the past. That's fine, but we're not going to overdo it.

So this is NOT true, that these books are decodable for the individual reader, not unless they have studied that phonics. This is not a true claim, that these books are decodable for the readers, because the words themselves are phonetic. They're decodable when the students have learned the pattern!

They talk about how these books are good because the language sounds a bit like talking, and I totally get that. That is why I really, really, really, really resisted switching from leveled to decodable books. That's the joy of leveled books, especially for the teacher, when you're hearing kids "reading" these books. It sounds like they're fluent because they're just remembering the pattern and then adding the last word from the picture. It's a good feeling to hear them do that, because it feels like they're developing strong reading habits and abilities.

On the other hand, when you hear them work really hard to sound out each word, it's rather painful and not very fun. There's a really, really good blog post by the Right to Read Project. It's called "The Drudgery (and Beauty) of Decodable Texts," and I'll link to that in the show notes. And I believe that she addresses this there, or maybe I heard it on a podcast somewhere. But Margaret Goldberg talks about how this is really hard at first, to listen to kids struggle through sounding out words. It feels like they're never going to get there, but they do. They do! And fluency will come.

When we try to push fluency early, by giving them these contrived books that make them rely on the picture to solve the words, we're going about things backward.

In the recording, you may have heard Pinnell say that they put in these repeating elements, but that readers don't depend on them or memorize the books. That's wishful thinking.

There's a really good video on YouTube about the "Paint It Purple" book. I actually had this book and used it with my kids as beginning readers. It's from Reading A-Z. It's a leveled book, and they solve the words by using the pictures. In the video the mother records her daughter reading it and then shows that she doesn't remember any of those words later, because she wasn't using phonics knowledge to sound them out. But then, when her mother gave her a very explicit phonics lesson, then she could read a lot more of those words in isolation. That is a really big eye-opener! Definitely watch that two-part video on YouTube, I'll link to it in the show notes.

To conclude their blog post, Fountas & Pinnell ask us to think about the contrived texts, as they call them, that we're using for beginning readers. Do they have a real story? Do they provide interesting information? Do they engage the child? Does it sound like language? Does it also provide the opportunity to sound out words?

It should do both; they're right about that. It should sound like language, as much as possible, and it should provide the opportunity to sound out words. I will not say that all their books do that because most of them, those early books, only provide a couple of examples where kids can sound out words. And guess what? They don't even need to, because they have the picture to help them.

I had this conversation with a principal when I was really struggling with switching from balanced to structured literacy. He was very kind. He sent me a Facebook message when I had made a comment in a large science of reading Facebook group. He offered to hop on the phone with me, and so we talked. He teaches at a school with a lot of kids who struggle to read. They had switched to decodable books, and I said, "Well, doesn't that just make them not like to read anymore, because you're giving them these awful, boring books?"

This is what he said to me. "You've got to understand these kids can't read. When we give them these books that they can read, because we've taught them the skills they need to read it - we've taught them to actually identify each individual word on the page - that's where the love of reading comes from. The love of reading comes from the success they have, the seeing that they can do it.

"On the other hand, kids know when they can't read, right? If you give a child a book that's leveled, and they're supposed to solve everything by the picture, I think they know that they're not really doing the reading. They're kind of guessing at the words, because that's the only tool they're good at. They haven't had a chance to really hone their phonics skills because they're not using them much. They may be having a phonics lesson way over here, but then they're not applying it to the reading that they're doing. And if a child struggles with reading, I can guarantee they're going to pick the thing that's easier to do, which is guessing with the picture versus actually sounding out words."

So yeah, I've got to say this blog post was a definite miss. It's disappointing to hear that they don't see any value in decodable books, when really that's the primary reading material that our youngest readers should be reading. Will they be exposed to other quality texts? Absolutely! They'll be exposed to them in whole class read alouds, and the comprehension discussions that follow. But, for their actual instruction and practice, they should be reading decodable books.

If you're not sure about that, if you're still holding back on that one, I understand. I'm going to provide a bunch of episodes and blog posts for you, in the show notes, that will help you. So thanks, so much, for listening.

I'll be back next week with another Fountas & Pinnell reaction. You can find the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode61. See you next week.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Emily Hanford’s response: Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Mark Seidenberg’s response: Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

The Drudgery and Beauty of Decodable Texts – the Right to Read Project

YouTube Video: The Purple Challenge (a must-watch!)

The Ultimate Guide to Decodable Books

Should you use decodable or leveled texts with beginning readers?

Using decodable and leveled readers appropriately (very helpful workshop – free on YouTube!)

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #5: Here’s why you SHOULD use decodable books appeared first on The Measured Mom.

It’s a giveaway for our 9th anniversary … and we’re choosing NINE winners!

It’s hard to believe, but we’ve been in business for nine years!

When I began this website, I was a mom of four kids, ages 5,4, 2, and almost 1.

Since then we’ve been blessed with two more kids, and our oldest two are taller than I am. This year our kids are 14, 13, 11, almost 10, 7, and 6.

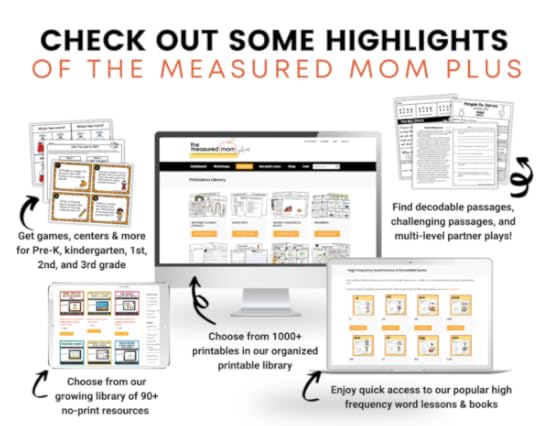

A lot can happen in nine years!We’ve published hundreds of blog posts and shared over 800 free printables on our website.We’ve created a huge collection of low-prep resources for our shop.We’ve published two online courses, Teaching Every Reader and Teaching Every Writer.We host a weekly podcast, Triple R Teaching.We sell a monthly membership for busy PreK-third grade educators.It’s time for our yearly anniversary celebrationEach January we celebrate the blog’s anniversary by hosting a giveaway. This year we’re giving away NINE yearly memberships to The Measured Mom Plus!

What is The Measured Mom Plus?It’s our one-stop shop for high quality, ready-to-use printables AND professional development!

Check out this quick video:

When you join the membership, you will receive:New printables for PreK-third grade each monthNew no-print resources for PreK-third grade each monthAccess to 1000+ printables in our printable libraryFree no-print resources24/7 access to our video workshops33% savings in our shop Here’s what our members love most …

Here’s what our members love most …“I can quickly find things that my students enjoy.”

– Debra, special education teacher

“I love that everything is made for me, and all I have to do is print and use!”

– Mary, 1st grade teacher

“The membership has whatever I’m looking for, in whatever area I need! I’ve taught in early childhood for over 30 years, and I like to keep on top of on new research and ideas. Anna is always organized and on top of things. The site is so professional.”

-Laurie, Pre-K teacher

“The membership has lots of great materials, and since I have access to all the grade levels, I’m able to meet more students’ needs.”

– Shannon, 2nd & 3rd grade teacher

“I love the ease of the website. Everything is easy to find. I love the activities I can easily make for centers. Everything is easy to find, make, and use!”

– Maura, 1st & 2nd grade teacher

“I love that I can look through multiple grade levels for different skills and activities!”

-Andee, special education teacher

“Last year I switched from second to third grade. My membership helped me not skip a beat! It was so great to have trusted, valuable resource to turn to, especially when it felt like I was out of my depth with new standards, a new school/district, and an unprecedented year! I LOVE how responsive Anna and her team are!”

-Jennie, 3rd grade teacher

“The resources are amazing! I am a reading specialist, and the resources for foundational skills complement the interventions I use daily with my students.

-Nicole, special education teacher

“I love the print and play games, the Google Slides games, and the professional development videos! The ideas help me improve my teaching and make it more engaging.”

-Elizabeth, kindergarten teacher

The post It’s a giveaway for our 9th anniversary … and we’re choosing NINE winners! appeared first on The Measured Mom.

January 2, 2022

Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #4: Here are the problems with guided reading

TRT Podcast#60: Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #4 – Here are the problems with guided reading

For Fountas and Pinnell, guided reading is the key piece of the reading block. But there are some problems with the guided reading approach in K-2.

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here, and I'm excited to join you for Episode 60 of Triple R Teaching. We are continuing our series in which I respond to articles on the Fountas & Pinnell Literacy website. They have published a series called "Just to Clarify," in which they react to criticism of their work.

Today, we're going to look at the blog series' question four, which is "How does guided reading and the use of leveled texts advance the literacy learning of children, and what role does guided reading play within a comprehensive literacy system?"

We're going to start by listening to Irene Fountas' response. We're going to listen to the first portion of it in which she explains what guided reading is:

"Guided reading is small group instruction. Groups are formed with students who are similar at a particular point in time in their reading development. The teacher selects a short text that offers both support and challenge, an instructional level text for their current processing abilities, thus setting the scene for expert differentiated teaching. With explicit teaching, the teacher observes and interacts with students to support more efficient processing. Lessons should take about 15 or 20 minutes per day, perhaps a bit more as the texts get longer. The goal is for students to process one text after another, each with increasing complexity."

She then goes on to explain that guided reading is just one part of the day. You also should be teaching phonemic awareness and phonics and whole class lessons. You should have interactive read-aloud and shared reading, and so on.

So I want to start by saying that I appreciate that here Irene Fountas lets us know that guided reading is just one part of the reading block. However, I want to repeat what I've said before that one problem with balanced literacy, certainly when I was teaching with it, is there tends to be more of a focus on these activities, these structures of, for example, shared reading, guided reading, and so on, rather than a focus on the skills that should be taught within them.

Balanced literacy and guided reading can be haphazard.There may not be a scope and sequence helping teachers understand what they want to teach their students throughout the year. Instead they have a collection of books, and then they choose lessons based on the book rather than starting with the scope and sequence. So that's something to be aware of.

One of the major tenets of guided reading is that children are working with a text at their instructional level. So you assess their level using the Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System or running records, and then in the group, you're teaching them with something slightly higher than that called their instructional level.

There has been a lot of discussion and research around teaching kids at a certain level versus giving them access to all different levels of books. I am not going to say that I know a lot about that because I don't. I still need to read and study that a little bit more. I know Timothy Shanahan has written a blog post about it. So I'm not going to address that specifically, but I do want to talk about how Fountas and Pinnell determine reading level.

They use the Fountas and Pinnell Text Level Gradient, which, of course, they created. To determine what level students are at, A through Z, you're going to give them running records or use the running records within their Benchmark Assessment System.

The problem with this, the BIG problem, is that for the youngest readers, the leveling tests - the running records and the assessment system - are really just measuring how good students are at three-cueing because they can't sound out most of the words in those early books. They have to use pictures. They have to use context. They have to use maybe the picture and the first letter.

As we've discussed, especially last week, that's not really reading! That's guessing. Balanced literacy teachers do not want to hear that. Guessing is when you use lots of information, but you don't know for sure if you're right, and that's exactly what this is. If they can't ultimately check that they're right by matching the sounds to the letters, they can't 100% know.

So we have to ask ourselves, "What do these levels really tell us? If a student is at level C or D, what does that mean?"

It can't really tell us a whole lot. It doesn't tell us what phonics knowledge they have. It doesn't tell us how strong they are in phonemic awareness. It can't tell us that because it's impossible to know from a student's reading of one of those early texts. The texts require them to use pictures and context, otherwise there's no way they could read them.

So I have to question the validity of the leveling system, at least for those early levels. I'm not yet ready to say that we should throw out the leveling system or idea for older readers. Maybe I'll get there someday, but I'm not there right now. However, I do have a real problem with it for our youngest readers.

This leads me to my next point. If we have to question the validity of these levels, particularly for our youngest readers in K-2, then we have to question the formation of these groups. Because if we can't really trust or get much value or information out of a level D reading level, then why would we put students who are supposedly level D into a group? They may need quite different instruction.

I believe the better option, particularly for kindergarten and first grade, is to give a strong phonics assessment and then teach phonemic awareness and phonics within those small groups, maybe for about 15 minutes a day.

I know that Fountas and Pinnell will not tell you that phonics is not important. They will tell you it matters. It's important. They have material for teaching phonics. But I have next to me their book about guided reading, their second edition published in 2017, and this is a fat book. We're talking around 600 pages! Would you like to guess at how many pages in this 600-page book address phonics? It's less than five.

Now to be fair, they have other books about phonics. But if you understand the Simple View of Reading and you know that reading comprehension occurs as a result of decoding and language comprehension, you know that we have to give more than five pages of attention to phonics!

In these early guided reading groups, children should be using phonics to solve words because without phonics, there is no decoding.

I'm not ready to say that we should throw guided reading away forever for all grades, but I do question its value with our youngest readers, who really need to work on their foundational skills.

A quick recap of my reaction to Fountas and Pinnell's mini blog post about guided reading. Guided reading lessons are often haphazard, and they don't typically follow a scope and sequence. Another problem is that the levels are not very informative, particularly for our youngest readers. What we really need is to know what phonics knowledge they have. And giving them this A, B, C, D, E, F, G level is really just telling us how good they are at three-cueing because with those early books, they can't sound out most of the words. They don't have the phonics knowledge yet.

Instead, I think time would be better spent, in kindergarten and first grade for sure, giving a strong phonics assessment and grouping students by phonics need and teaching that in the small groups.

Those are some quick thoughts for you on what I think about Fountas and Pinnell's approach to guided reading in the primary grades. Thanks for listening. You can find the show notes at themeasuredmom.com/episode60.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Emily Hanford’s response: Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Mark Seidenberg’s response: Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

Timothy Shanahan: Should We Teach Students at Their Reading Levels?

The difference between balanced and structured literacy

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #4: Here are the problems with guided reading appeared first on The Measured Mom.

December 20, 2021

The Best books about teaching phonics

Looking for books about teaching phonics? Here are my top recommendations!

Phonics from A-Z, by Wiley Blevins

This classic is on its third addition, and Wiley Blevins starts with phonemic awareness and takes us through planning phonics lessons and meeting the needs of students who struggle. It truly is the A-Z guide!

A Fresh Look at Phonics, by Wiley Blevins

Unlike his previous book, which is more of a guidebook, this book challenges us to think about mistakes we may have made when teaching phonics – and how to fix them.

Making Sense of Phonics, by Isabel Beck & Mark Beck

This book will help you understand where phonics fits in the big picture of teaching reading and gives powerful tips and ideas for helping kids sound out words and tackle multisyllable words. Like Blevins’ aforementioned books, this is a must-own.

Uncovering the Logic of English, by Denise Eide

If you’ve ever felt that English is so illogical that you want to throw up your hands in despair, you need this book. Eide shows us that English isn’t as “crazy” as some of us have been led to believe. The book is a quick and easy read and one you’ll want close by.

Teaching Reading Sourcebook, by Bill Honig, Linda Diamond, & Linda Gutlohn

This gigantic guide is an incredible reference book. Don’t let the price tag scare you away; you’ll reference this book often. It’s not just about phonics; you’ll refer to this book as you teach phonemic awareness, fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary as well. Put it on your wish list!

How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction, by Sharon Walpole & Michael McKenna

If you want to get started with small group phonics lessons but don’t have a curriculum, this book is an affordable option. It tells you everything you need to know to form reading groups based on phonics knowledge, and gives you the materials for each lesson. I wouldn’t call the lessons highly creative, but they ARE effective.

Looking for words to use in your phonics lessons?

Ultimate Collection of Phonics Word Lists

$15.00

Print our ultimate collection of phonics word lists, and you’ll have over 200 word lists at your fingertips! From CVC words to words with prefixes and suffixes, this collection has it all!

Buy Now

The post The Best books about teaching phonics appeared first on The Measured Mom.

December 19, 2021

Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #3: Yes, you ARE teaching guessing

TRT Podcast#59: Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #3 – Yes, you ARE teaching guessing

No one likes to admit they’re teaching kids to guess at words, but that’s exactly what’s happening when we teach beginning readers to use three-cueing. This short episode explains the connection.

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from the Measured Mom, back for the third episode in our reaction to Fountas and Pinnell's blog series called "Just To Clarify."

You remember that Fountas and Pinnell are big names in literacy education here in the United States and around the world. They have created a very popular reading series that is used by many schools, as well as an assessment system and other things.

The problem is that a lot of the things that are foundational for their program do not align with the current reading research. They have been under criticism for a long time, and just recently they have published a series of ten blog posts basically defending themselves against the criticism. Now I am responding with a ten-part podcast series reacting to each of those posts.

Their third post reacts to this question that has been sent to them, "Some have suggested that you support the use of guessing. Can you comment on this?"

Here is their response: "We do not use the word 'guess' in our writing, nor with children in instruction. As readers process texts, they often make attempts at difficult words, using their experience and knowledge. They make predictions based on information in the text and information they bring to the text.

"For example, a child who cannot yet sound out the word 'elephant' from his knowledge of syllables and the “ph” digraph can read a story about one following print, left to right, and making sense of his reading and using the letter-sound knowledge within her power. When she uses the picture information, the letter sound information actually becomes more available to her. Calling this 'guessing' fails to recognize the complexity of what she is really doing.

"Again, the goal for the teacher is to demonstrate and encourage the reader to persist in using all sources of information together; meaning, language, and letter-sound information."

This goes back to our episode last week, where I said that teaching students to read using three-cueing shows a misunderstanding of how reading works in the brain. We're coming back to that again here. Do you see how important it is to really understand how reading works?

If you think that kids read by combining all these cues at once - meaning, language, letter sounds - then three-cueing makes perfect sense. And it makes sense to give them books that require them to use three-cueing. But when you understand that the three cueing model is popular, but not backed by research, and that teaching students to read using three-cueing may look like it's working, but is actually bypassing important things that need to happen in the brain, then you realize that yeah, having kids solve words with three-cueing IS teaching them to guess.

The definition of guess is to estimate or suppose something without sufficient information to be sure of being correct.

So if a child is "reading" a leveled book, which includes words they are not able to sound out, and they use the picture to help them solve the word, they can't know for 100% sure that they're right, because the only way to know 100% sure that you're right is to be able to match the phonemes to the graphemes. If they can't do that, if they can't sound it out all the way through, then they're not 100% sure if they're right. That would be the definition of a guess.

This accusation of teaching kids to guess bothers balanced literacy teachers. Like I said, it bothered me when I taught with three-cueing. Did you notice what Irene Fountas said at the very beginning of her reaction? She said, "We do not use the word 'guess' in our writing, nor with children in instruction."

I hear that a lot. "Well, I don't tell my students to guess!" You may not be telling them to guess, but by the cues you're giving them, that's what you're expecting them to do.

In the last sentence of Fountas' answer, she says that calling this reading process "guessing" fails to recognize the complexity of what the reader is doing.

Now, I would never want to say that learning to read is simple or that teaching reading is simple, because it's not. It's very complicated. In fact, Louisa C. Moats has written an article called "Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science."

However, when we try to say that learning to read is complicated because we're integrating all these cueing systems, we've missed the mark. Instead, I recommend learning more about the four-part processor, and I'm going to link to a YouTube video that explains this very well in the show notes.

So to conclude, we may not want to admit it, but if we're teaching students to read with three-cueing, we are teaching them to guess because if they don't have the phonics knowledge to read the words, they really don't know for sure if their reading is accurate.

Next week, we're going to get into the fourth post by Fountas and Pinnell. We're going to talk about guided reading and leveled texts, so stay tuned!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Louisa C. Moat’s article Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science

YouTube video explaining the Four Part Processor

Podcast episode: What’s wrong with three-cueing?

Podcast episode: How the brain learns to read

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #3: Yes, you ARE teaching guessing appeared first on The Measured Mom.

December 12, 2021

Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #2: Fountas & Pinnell are wrong about three-cueing

TRT Podcast#58: Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #2: Fountas and Pinnell are wrong about three-cueing

Despite the lack of evidence for three-cueing, Fountas and Pinnell aren’t budging. In this episode I respond to their recent blog post in which they claim that we must help students use multiple sources of information to solve words.

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, hello, Anna Geiger here. Welcome back! We are on our second reaction to the Fountas and Pinnell blog series called "Just To Clarify," in which they react to criticisms of their work.

Fountas and Pinnell, as you recall, are leaders in literacy education in the United States. They have created a very popular reading program that's used in many schools. We consider them the founders of balanced literacy. They may try to distance themselves from that label, but the fact is it came about during their work back in the '90s.

The current situation is that with studying the science of reading and structured literacy, a lot of people are accusing them of promoting methods that do not teach reading well and that do not meet the needs of a large number of students.

Fountas and Pinnell have reacted in a series of blog posts, and today, we are touching on a big one. Question number two is, "Can you clarify what MSV analysis is and why you believe it's important?"

This is all about three-cueing. If you've followed my podcast for a long time, you know I've talked a lot about this. This is kind of the big rotten apple in balanced literacy. It's the thing that absolutely has to go!

Let's review what MSV stands for. M is meaning, S for syntax, V is for visual. So as a balanced literacy teacher, I believed that students use these three cues to help them solve words. They used the context - that's meaning, they used grammar - that's syntax, and they used phonics - that's the visual cue. And they used them all together simultaneously. Maybe sometimes they'd be using one cue more than another, but they'd be using them all together to solve words. It wasn't just about sounding it out.

In my opinion, this has to do with a misunderstanding of how reading in the brain works. Before I get to that, let's go ahead and listen to a portion of Irene's answer: "The goal for the reader is accuracy using all sources of information simultaneously, and that includes processing each letter in words from left to right. If a reader says 'pony' for 'horse' because of information from the pictures, that tells the teacher that the reader is using meaning information from the pictures, as well as the structure of the language, but is neglecting to use the visual information of the print. His response is partially correct, but the teacher needs to guide him to stop and work for accuracy."

Oh boy, there's a lot to talk about just in that little section.

So they talk about the goal for the reader is using all sources of information simultaneously. That's what I'm talking about when I think it's a misunderstanding of how reading works. We've talked about the science of reading in other episodes and we've talked about the importance of understanding that when you're reading, you are matching the phonemes to the graphemes so orthographic mapping can occur.

Orthographic mapping is reading words instantly and effortlessly after repeated exposure to the word, repeated practice sounding it out. You have to remember that we're not storing thousands and thousands of words in our brains as wholes. We're actually matching those sounds to the letters very, very, very quickly as proficient readers. But students can't learn to do that unless they actually HAVE to sound out the word.

Fountas and Pinnell and other balanced literacy advocates are telling us that there are other pathways to get to the word. We could look at the picture. We could use the picture and the first letter. We could think about what sounds right. Those are backdoor ways of getting to the word.

Maybe they'll help us understand that text itself, but they're not going to serve us for the future because those "strategies" are actually not giving students practice doing what they need to do most in these early stages of reading. They HAVE to match the phonemes to the graphemes. They have to sound it out!

We looked at pictures of the brain and how scientists have learned through fMRI that proficient readers are having all the right circuits firing in the left hemisphere. But children with dyslexia often do not have all those areas well developed, and their reading work is happening on the right side of the brain because they're needing that extra practice, building those phoneme-grapheme connections.

If we're teaching them to use context or what sounds right, we're actually having them do their reading work on the right side of the brain, which is the wrong side for learning to read. I often hear from people defending three-cueing that it comes from Marie Clay and her observations of how children read. Now I can't speak to this extensively because I have not studied Marie Clay's work, even though I have some of her books that I bought many years ago.

But you can see right away, there's a problem, right? If she's making an observation, it's sort of a guess because you don't know what's actually happening inside their brains. Through research and, like I said, fMRI and other things, scientists have learned that students read by matching phonemes to graphemes. That is what they're doing. That is what successful readers do. These things that we're teaching in balanced literacy, which include using context or pictures, are actually reinforcing the habits of poor readers.

Now, back when I was a three-cueing advocate, I did not want to hear this and I did not accept it. And we'll talk more about that next week when we answer their question about guessing. But I want to read some other reactions to you, some other perspectives about three-cueing. Let's talk about where it came from. I think that's really important.

This is a blog post from the National Institute for Direct Instruction, I will link to it in the show notes. Here's what they say: "The three-cueing system is well-known to most teachers. What is less well-known is that it arose not as a result of advances in knowledge concerning reading development, but rather in response to an unfounded but passionately held belief. Despite its largely uncritical acceptance by many within the education field, it has never been shown to have utility, in fact, is predicated upon notions of reading development that have been demonstrated to be false."

Now, someone first brought this to my attention a long time ago, I'm a little embarrassed to say it. I think it was around 2015 in my blog post comments, and I was like, "What?" She was saying to me that three-cueing is not backed by research, but I just learned about it a few years ago in graduate school so I didn't believe her. But I went back and forth with her a little bit and finally I said, "I'm sorry, I can't continue this debate in my comment section." And I just didn't believe her because I wasn't hearing this from other people.

It was about four or five years later where the science of reading really became more prominent as a result of Emily Hanford's article that I felt forced to study it myself. It was really hard, REALLY hard, to give up three-cueing because that basically turned how I taught reading on its head. I have a whole episode about what's wrong with three-cueing that you can find linked to in the show notes.

I also want to share what Lindsay at The Learning Spark had to say. She wrote a blog post all about her pet peeves about teaching reading, and her pet peeve number two was those resistant to give up three-cueing. I want to read to you the paragraph from her website: