Anna Geiger's Blog, page 25

October 27, 2021

What’s the difference between Dolch and Fry sight words?

In our first post of this series we explained the difference between sight words and high frequency words.

Sight words are words we know by sight, without needing to sound them out or guess.High frequency words are words that appear frequently in the English language.Our goal for our students is that they turn high frequency words INTO sight words.But where do we get these high frequency words FROM?

Enter Dolch and Fry.

What is the Dolch word list?The Dolch word list was published by Dr. Edward Dolch in 1936.

Dolch was a proponent of the “look-say” method of teaching reading. He believed that reading instruction should begin by teaching children to memorize words based on their shape.

(Now that we understand how the brain learns to read, we understand that this is a faulty method of teaching reading).

In his book, Teaching Primary Reading, Dolch even stated that first graders should learn only sight words, and teachers should wait until second grade to introduce phonics (!!).

For decades, the science of reading has shown the importance of beginning phonics instruction. Therefore, we need to seriously question completely abandon Dolch’s approach.

However, his original list of 220 high frequency words remains popular today.

This list of 220 words contains no nouns; Dolch later created a set of 95 nouns, but his original list consists of “service words” because these words appear in any type of text, no matter the content.

You’ve likely found lists of Dolch words organized by grade level.

However, these groupings really don’t make sense. For example, “yellow” is on the pre-primer list, but “if” is on the third grade list.

Huh?

What is the Fry list?Edward Fry, like Edward Dolch, believed in the look-say method of teaching reading.

He did acknowledge that teachers should teach phonics, but he didn’t have much to say about it. Instead, he focused on teaching students to memorize the most common high frequency word from his Fry Lists, which contain all parts of speech.

According to Fry, in his book, How to Teach Reading, students should learn the first 100 words in their first year of school, the second hundred in the second year, and the third hundred in the third year.

Is there anything wrong with using the Dolch and Fry lists?There is nothing wrong with having lists of high frequency words that students should learn.

The issue is HOW we teach them, and WHEN.

“We need to bury the idea that Dolch words, Fry words, or words from any other high frequency word list need to be taught through memorization. Rather, they should be included in phonics instruction so that, as early as possible, students use spelling patterns to read a greater variety of words than just those on high frequency lists.”Source: COMPARING THE DOLCH AND HIGH FREQUENCY WORD LISTS, by Farrell, Osenga, & Hunter

In the upcoming posts in this series, we’ll examine HOW and WHEN to teach high frequency words.

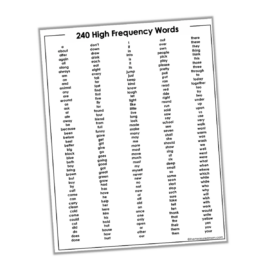

In the meantime, you’re invited to download a list of high frequency words

When I create sight word resources, I know that teachers are often required to teach words from both the Dolch and Fry word lists.

I’ve created a list of 240 words that includes the Dolch 220, Fry’s first 100, and a few others.

Get your free word list here

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

Stay tuned for the rest of this series!

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Part 10

The post What’s the difference between Dolch and Fry sight words? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Sight words vs. High frequency words: What’s the difference?

Sight words vs. high frequency words. What’s the difference? This is the beginning of our blog series all about sight words.

What are sight words?

What are sight words?Traditionally, when teachers say “sight words,” they are referring to high frequency words that children should know by sight.

We often define sight words as words that kids can’t sound out – words like the, for example.

But this definition is not correct. While sight words may be irregular, the definition of sight words is NOT words that kids can’t sound out.

Reading researchers have a different definition of sight words.

A sight word is a word that is instantly and effortlessly recalled from memory, regardless of whether it is phonically regular or irregular. A sight-word vocabulary refers to the pool of words a student can effortlessly recognize.

David A. Kilpatrick, PhD

As an adult, most of the words you encounter are sight words, because unless you’re reading from a challenging textbook or a technical manual, you know the words automatically. You don’t need to sound them out.

What are high frequency words?High frequency words are the words that are most commonly used in the English language. These words may be regular (as in and) or irregular (as in the).

It’s essential that students develop automaticity as they read, and one way to do this is to help them read many high frequency words by sight.

Our goal is to make high frequency words SIGHT WORDS.We want our students to recognize high frequency words instantly. But the way we do this isn’t by giving them stacks of words to memorize.

Will students memorize some high frequency words?

Yes, at first.

They’ll memorize their names and a few other words like Dad and Mom.

And there’s nothing wrong with teaching pre-readers a small set of sight words before they begin reading. In their article, A New Model for Teaching High Frequency Words, Linda Farrell, Tina Osenga, and Michael Hunter recommend teaching the following sight words to new readers:

theaItoandwasforyouisofWe can teach these words to students after they know letter names but before they’ve begun phonics instruction.

However.

This is just to get them started.

There’s a problem with the common practice of sending home lists of words for students to memorize. “While this method works for many students, it is an abysmal failure with others.” (A New Model for Teaching High Frequency Words, by Farrell, Osenga and Hunter).

Rather, we should integrate high frequency word instruction into phonics lessons whenever possible.

More on that in a minute. First …

What are flash words and heart words?Some educators refer to decodable high frequency words as “flash words.” These words appear so frequently that students should be able to read them in a flash.

Irregular high frequency words are sometimes called “heart words” because there are parts of the word that can’t be sounded out; students must learn those parts “by heart.”

Teach both flash words and heart words using phonicsBe leery of any reading program that says students need to “just memorize” irregular words.

Rather, look for a program that organizes high frequency words to fit phonics lessons wherever possible.

In other words, teach the word can when students know the sounds of c, a, and n.

Even with irregular words (“heart words”) we can all attention to the part of the word that IS regular.

Really Great Reading has some excellent instructional videos to help you teach those tricky heart words.

Find all of Really Great Reading’s “heart word magic” videos here.

Will we just ask students to memorize SOME sight words?Yes. High frequency words are the glue that hold decodable sentences together. We want students to know some of these words so the decodable books they read make sense.

Because of that, we’ll teach a small number of sight words to pre-readers, and additional words as needed so our students can read their decodable books.

But let’s let go of this idea that students need to memorize lists and lists of sight words.

Turn high frequency words into sight words with these engaging mats!

High Frequency Word Practice Mats – 240 words!

$24.00

Students will count the sounds in words, spell them, read them in context, and more! What a meaningful, multi-sensory way to master high frequency words!

Buy Now

Stay tuned for the rest of this series!

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Part 10

The post Sight words vs. High frequency words: What’s the difference? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

October 10, 2021

Science of Reading Q & A: #1

This past week Becky Spence and I shared a video workshop about the science of reading. Because of some technical difficulties, we weren’t able to do our question and answer session live. Here are answers to questions submitted after the webinar. More to come next week!

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, and welcome to Episode 51 of Triple R Teaching! I'm recording this on Friday, October 8th, 2021, and what a week it has been!

This tends to be my busiest week of the year because my colleague, Becky Spence, and I release our training about the science of reading. We give live presentations for two nights, and then we offer our online course.

That's what this week has been, but Monday and Tuesday were the first time in four years of giving live presentations that they totally flopped! We had a terrible technical experience with Demio, and I'm not sure why because I've had good experiences with them before. I don't know what was happening, but I just kept getting kicked out and kicked out. It's a really awful feeling when you're trying to give a live presentation to hundreds of teachers who have taken time out of their day to listen to you! I know how busy they are, and then felt awful to consistently waste their time because the audio kept cutting out!

So we had to give up, and we ended up recording the training so that teachers could watch it. That training is coming down the day that I'm recording this, so it will not be available anymore once you're listening to this podcast, but I wanted to record this podcast in connection with the video because we had a lot of great questions that were asked.

Typically, when we give the live training, our assistant gathers questions during the training and we answer them at the end. We could not do that this year because of our technical issues, so I asked people to submit questions via a Google Form. I've got quite a few. I'm not going to do all of them this week, but I think I'll tackle some this week and then some next week.

This is going to be kind of an off-the-cuff presentation, mainly because we've got out of town guests at our house this weekend, and I'm giving a live presentation again today - thankfully, I'm not hosting it, so hopefully audio is not a problem this afternoon. So there's just a lot going on in my life and I don't have a lot of time to edit this before I pick up my little guy from kindergarten in about 45 minutes. So please forgive me if it's a little less rehearsed, but we're going to answer some of the questions from watchers of this training that we gave.

One person wrote this, "Just wondering why the 'experts' think that the queuing systems are totally invalid. I am a former Reading Recovery teacher, and Marie Clay researched what 'good readers' did to come up with her interventions, many of which are very much aligned with the science of reading. Could it possibly be that the techniques were just not good for poor readers or dyslexic readers?"

So I totally understand where this person is coming from because this was certainly what I felt for a long time. I think what we have to really understand is what the point is of getting words off the page. It's not just to figure out what the words could be or to figure out what the words are (through using pictures or context or whatever). The point is that we want kids to sound out the words so they orthographically map the words, so that they remember them for the future. When you remember that, three-queuing feels a little counterproductive because yes, kids might be figuring out what the words are, but not in a way that's going to help them for the future.

Now, I want to be clear, balanced literacy does work - for some kids! When someone finally acknowledged that fact to me when I was struggling with this, it really helped turn the tide for me. Once someone acknowledged to me that yes, balanced literacy works for a lot of kids, but it's just that for some kids, they get to third grade and they hit a wall. They can't use those cues anymore because they don't have the books with all the supports. They start to fall apart.

That was what I needed to hear - that three cuing appears to work and does work for some kids. But for many kids, they hit a wall when they get to third grade and they don't have the strategies they need to actually sound out those words. They have three queuing, which only gets them so far.

I cannot speak to the research that Marie Clay did. I don't know if it was just observational research. I'm not sure if the things she came up with would contradict the things we know now about how the brain works and what orthographic mapping is. So I can't speak to her research, but I would like to talk to the last point, "Could it possibly be the techniques were just not good for poor readers or dyslexic readers?"

Well, I used to think about this too. But I think we have to ask ourselves, if they're not good for poor readers or dyslexic readers, why are we using them? There are many, many, many poor readers in the United States. If you look at results of standardized test scores for fourth graders, they're pretty dismal. There's a very low percentage of kids that are actually reading on grade level. I would recommend you check out Nancy Young's, "Ladder of Reading". You can just Google that and you'll find it on her website. I'm looking it up right now as I'm recording this.

What she did is she followed the research and she found out that for 5% of kids, reading is pretty effortless, right? Those are the kids that kind of teach themselves to read. They exist! Not very many, but they exist. 35% learn to read pretty much no matter what method you use, including balanced literacy. 40% to 50% really need that structured approach, and 10% to 15% have dyslexia.

That's a pretty significant percentage. If our main way of teaching reading is not going to serve a good number of our students, I think we need to reevaluate. So that's my answer to that question.

Another question was, "What are some suggestions you have to help students in third grade who can't spell? Is sounding out still a strategy?"

When I think about teaching spelling or helping kids with spelling, of course you always need to be doing that phonics instruction. A really good thing to remember is to connect the phonemes to the graphemes when spelling.

My little daughter is in second grade, and her teacher gives some challenging spelling words. When we work on those challenge words, we break the word into phonemes, and we draw a line for every sound, and then we fill in the blanks.

One of her words this week was "physical". So we said, "Let's count all the sounds /f/ /ĭ/ /z/ /ĭ/ /k/ /əl/." So we had to put six lines on the paper. We talked about how she knew right away that P-H can spell /f/, so she wrote that down. The next one was harder, /ĭ/, what can that be? I told her that in this word, the Y represents the /ĭ/ sound. Now, when she was trying to spell this word on her own, she was doing P-H-Y-I. That means she was using two different letters to represent the /ĭ/ sound. But when we took it apart into its individual phonemes and represented those on paper, she could see, "Oh yeah, I only need ONE vowel here, and I'm going to use the Y as a vowel." Then for the /z/ sound, we talked about how in this word, the S represents the /z/ sound and so on.

That really helped. I would encourage you to help kids break words apart into phonemes, and then use the phonics knowledge they have to fill in the blanks. I think just that can help tremendously!

Someone else said, "I would love to see what a science-of-reading-based small group lesson in kindergarten would look like."

We actually get into this in great detail in "Teaching Every Reader," our course, which if you're listening to this on Monday, October 11th, closes to the public tonight. I believe it closes at 9:30pm my time, which is Chicago time.

What we say in the course is that first, you should assess students' phonemic awareness and phonics knowledge and then group them accordingly. You may have groups of kids who are still learning letter names, and you'll probably have some kids who are reading, depending on where you're teaching. So you're going to want to group them.

I personally would try not to do more than four groups. It's just really hard to meet with that many separate groups. I know that can be very hard to narrow it down to just four, but if you think about it, that's way better than the whole class, right? They're still getting much more focused attention than they would if you were teaching them all as one group.

Then within those small groups, you want to be following the structure of an effective phonics lesson, understanding that this is going to be a little different with the kids who are still learning their alphabet. But once they're learning their letters and ready to sound out words, it would look like this: You'd start with a phonemic awareness warmup. You're going to connect phonemic awareness to the phonics skill you're teaching. You'd introduce the new skill by EXPLICITLY telling them what you want them to know. No guessing here, just tell them. Then you're going to practice blending words based on the sounds they've learned so far. You're going to do word building with letter tiles or magnetic letters. If they're ready to read (if they're able to read more than a word or two), they can read decodable text. This could be just a list of words if that's where you're at, but hopefully before long they'll progress into quality decodable books. Then you're going to do guided writing, which could just be as simple as dictation where they practice spelling words that have the pattern that you've taught them.

So I go into this in a pretty good amount of detail on my website. There's a blog post called, "Do's and Don'ts for Phonics Instruction," and there I talk a lot more about phonics. There's also a graphic with this layout of a phonics lesson that you might want to download.

Another teacher asked, "For the 'Say It, Move It' activity and the phoneme grapheme mapping, how many chips would you use for a blend, as in F-L for the word 'flip'? Would it be one chip for F-L as you would use for the /ch/ sound, or would it be two?"

Great question! Blends are two sounds. So for the word "flip," it would be /f/ /l/ /ĭ/ /p/ - four sounds, four blanks, four chips. Whereas in "chip" or "ship" or something like that with a diagraph, it would only be three because the diagraph is two letters that make one sound.

Someone else asked, "Where do nonsense words fit into this? We're required to test on them in kindergarten and first grade and use them to progress monitor until our winter testing."

So actually, it sounds like you're using them as you should! Nonsense words are great for assessing phonics knowledge. Sometimes kids can memorize words or they have seen a word enough that they kind of know it because it's a real word, but they don't necessarily have the phonics knowledge to sound out a nonsense word. If that's the case, then you need to go back and practice that skill. So nonsense words serve a very useful purpose, they can tell you if a child has actually mastered a phonics skill. That's a great time to use them.

Some teachers have students practice with them just to make sure they really know the phonics skill that they're learning. I wouldn't do a ton of that, but definitely they should be a part of phonics assessment.

So, in order for me to edit this episode and get it ready for my assistant to upload before I pick up my little guy from kindergarten, we're going to end this for this week. Again, if you're listening on October 11th, 2021, you can learn more about our course. Go to teachingeveryreader.com. If you're past the date, you can join the wait list or email me personally and talk about when you can become part of it. You can email me at hello@themeasuredmom.com.

Thanks so much for listening and hope to talk to you again next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Recommended ResourcesNancy Young’s Ladder of ReadingThe Measured Mom’s Do’s and Don’ts for Phonics Instruction Check out all the episodes in the Science of Reading BootcampEpisode 1: 3 reasons why there’s so much disagreement around the science of readingEpisode 2: How we read and remember wordsEpisode 3: The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading RopeEpisode 4: What IS structured literacy, anyway?Episode 5: What does research tell us about the Big 5?Episode 6: How to structure the reading block in a science of reading classroomGet on the waitlist for Teaching Every ReaderJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Science of Reading Q & A: #1 appeared first on The Measured Mom.

October 3, 2021

How to structure the reading block in a science of reading classroom

Now that we’ve laid a strong foundation, it’s time to apply the science of reading to your daily instruction. This episode will show you how to use what you’ve learned to schedule a powerful reading block that will meet the needs of all your students. Share this 6-week podcast series with friends who want to learn more about the science of reading. Also check out our online course, Teaching Every Reader! It opens for enrollment on October 4, 2021. Get the details here.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, and welcome to Episode 50 of Triple R Teaching! This also happens to be the final episode in our science of reading bootcamp.

We've talked about the reasons why there's so much disagreement around the science of reading. We've talked about how we read and remember words. We went through some really important foundational pieces of the science of reading - the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough's Reading Rope. We talked about structured literacy and what the research tells us about phonological awareness, phonics, and so on.

Today is the day we're going to get very practical! We're going to talk about how you could set up your day as you're teaching reading - particularly in kindergarten, first, and second grade - when you have an understanding of the science of reading.

It starts by planning your schedule. Before we plan our schedule, we need to look at the big picture. One fair criticism of balanced literacy is that it tends to be focused more on the activities themselves than on the skills. We don't want that to happen.

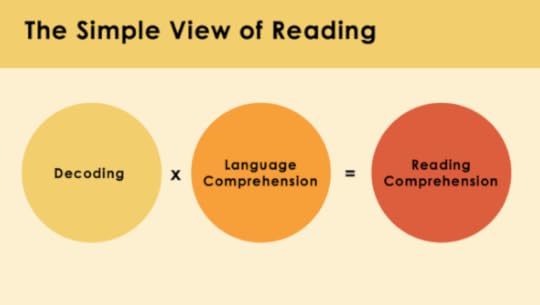

Let's think about the Big Five which we talked about last week and how they fit into the Simple View of Reading. Remember that the Simple View of Reading is a mathematical formula that tells us that reading has two basic domains - word recognition and language comprehension. So when children can read individual words and comprehend language, reading comprehension can result. It's set up like a multiplication problem. Word recognition multiplied by language comprehension equals reading comprehension.

If you've got that picture in your mind, let's think about the Big Five and where they fit. Phonological and phonemic awareness and phonics all have to do with word recognition, so you could imagine those under the first domain. Vocabulary fits under language comprehension. Fluency doesn't actually fit under one of the domains. It's the automatic application of the two domains of word recognition and language comprehension. And reading comprehension? That's the product, right? That's the goal of reading!

We teach phonological awareness through phonological and phonemic awareness lessons. We teach phonics through phonics lessons. We teach vocabulary and reading comprehension through whole class interactive read alouds, and sometimes by reading grade level text together, particularly in second grade. We also do focus on comprehension as much as possible with the decodable books that children are reading. We build fluency by teaching students to decode words, giving them chances to do repeated reading and allowing them to read independently.

Our task now is to put all of these individual pieces into a daily schedule. In doing that, we're going to remember to include whole class lessons, small group lessons, and time for students to work independently. Now this could look one thousand different ways, and it's going to depend on so many things. I'm just going to give you one option.

What I would do is start with the whole class interactive read aloud that I've planned carefully. During that lesson, I'll be teaching vocabulary and comprehension.

Then I would move into a small group lesson. I know that there are some teachers that prefer to teach the whole phonics lesson to the whole class every day. Unless you HAVE to do that, I would not. Students are at SO many different levels and to me, that's a way to get kids not to love reading. You may be pushing them too fast because they're trying to keep up with the other kids in the whole group lesson, or boring them to tears doing phonics that they knew a year or two ago. So personally, I would assess all the students using a phonics assessment that includes both real and nonsense words, and then I would group them.

I prefer no more than four groups because it gets really hard to find time to teach more than that. That does mean, of course, that some kids will probably be put in a group a little bit lower than they actually are just to manage the total number of four groups, but I think that's okay, it's a much better option than having them learn with the whole class.

So you would plan these groups in advance and then after the whole class read aloud, you would have your students start their small group phonics lessons. You could do three or four small group phonics lessons per day. It probably would be best to do just three a day, because then you could have a good twenty minutes for each one. This leaves you a total of sixty minutes for kids to be meeting with you and for other kids to be doing centers. What that means is that your highest group is probably not going to meet with you EVERY day, but I'm sure that if they're very advanced, that's not going to be a problem.

While your students are meeting with you, your other students are doing MEANINGFUL literacy centers. These are not going to be things that are just keeping them busy, they're going to be things that improve their literacy skills. One thing to keep in mind about centers is that they are a really good place to be doing the cumulative practice, the review. Make sure that what you put at centers is something that your students already know and that they're reviewing versus new stuff. You want to make sure it's something they're confident in and can do on their own because they really benefit from that repeated practice.

If there's time, it would be great to put in another whole class interactive read aloud, especially if you're teaching really young kids.

Then you'll want to have some time in the day for fluency building and independent reading. Now, fluency building would be something that I would recommend for first grade and second grade, but not necessarily kindergarten. They're really too early in their reading journey to practice fluency. Independent reading for kindergarten probably wouldn't happen until later in the year because at the beginning of the year, they're just looking at pictures. That's fine, you could put that in a literacy center where they're just enjoying books, and there's a lot of benefit to that, but I wouldn't necessarily call that reading.

I have a blog post called "The Do's and Don'ts for Teaching Phonics," and in that blog post I go through a specific set of steps that are really important to have in a phonics lesson. I'll include that in the show notes so you can think more about how to plan your small group phonics lessons.

Let's talk a little bit about independent reading. That's become kind of a hot topic in the science of reading community because traditional independent reading time hasn't always been beneficial, especially for our low readers. One criticism of balanced literacy is that students spend too much time in independent reading. You might hear that and think, "How could that be a problem? Shouldn't students spend lots of time reading independently?"

Well, yes and no. Independent reading time is a problem when we think that students learn to read by reading. I thought that for a long time. While a tiny percentage of students can indeed teach themselves to read, most students need, and ALL students will benefit from, systematic sequential instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, and other foundational skills. You know that!

When we leave them on their own for long periods of time, it's hard to make time for this important instruction. We don't want to have a forty five minute block of independent reading time because then where are we going to fit that explicit instruction?

It's also a problem when we don't give students any guidance in book choice. So if we say, "Okay, it's independent reading time, pick a book!" It can be questionable whether they're going to be able to read the book they choose, and if they're just looking at pictures, they're not growing as readers.

I know in the past, I assumed that because good readers read a lot, independent reading time will lead to better readers. But Tim Shanahan pointed out that correlation doesn't prove causation. Even if good readers read more, it doesn't mean it was reading more that made them good readers. It may be that good readers choose to read more because they can do it well.

Another problem with independent reading time is when we think that it will guarantee motivation to read. I know I have always held the belief that if students are given time to read, they'll learn to enjoy it and they'll become lifelong readers. The problem is that the motivational impact of independent reading time hasn't been studied very much.

Tim Shanahan also said, "In my experience, the better readers enjoy the free reading time so they continue to like reading, even within the independent reading time framework, but the other kids don't enjoy it much since they don't read very well."

The problem is that many struggling readers just pretend to read during independent reading time. They're not only NOT benefiting from this time, but they're actually losing instructional time that could be used to build the skills that would help them become successful readers.

I believe we should have independent reading time, but we have to come at it from a different angle. We should have it not because we want students to teach themselves to read, and not because we think that lots of independent reading time is going to increase motivation or help them become lifelong readers, that may result but there's no guarantee. No, we have independent reading time because students need to have practice reading and rereading texts to orthographically map the words! They need to have time to read independently so fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension can improve.

What I would do during this part of your day is to have each child have a large gallon plastic bag or some kind of book bin, and you would help them choose the books that would go in their bag. Personally, I would make sure that if you're doing decodable books with your students, kindergarten and first grade for sure, you would make certain that their bag has decodable books that they've already practiced. Or it could have new ones at their level for them to practice reading.

You could certainly have other books in there as well. If the child is enjoying a certain series of books and you know they do pretty well with them, you could include one of those. You could even have a "dessert" book, an extra book that they can "read" (even if they're not really reading it) after they've read their other books.

Use your best judgment about when to allow students to move out of decodable text for independent reading time. Once they have good beginning phonics knowledge and their strategy for reading is to look at the letters and sound out the words, not use pictures or context clues as a first line of attack, they might be ready for regular non-decodable books during independent reading time even if they can't read all the words.

You should also make sure that you have a system for letting students switch out the books in their bags, for instance maybe once a week you help students switch out books.

Ideally during independent reading time, you are moving around among the students and listening to them read and noticing who's ready for more books and who needs assistance.

That was all about independent reading, which is, I think something you need to include in your day. You've got one or two whole class interactive read alouds somewhere, you've got time for your focused phonics lessons while other students are doing review work at centers, and you have time for them to read independently, if they're at the right age for that - already reading at least decodable books.

You also want to think about fluency building. Some things you could do for fluency building include shared reading. You could have an enlarged book on a document camera on your screen, or a big book, or a poem that you read together and students can practice at least the prosody. Remember, prosody is when they read with expression, so that's a good time to practice things like that.

You can do partner reading with decodable books or other books that they can read together. You can do FORI, that's a whole class fluency building activity that you can look up. I've got information about that in my course, but that's something else you could try.

You can also include fluency at your centers. One of them could be buddy reading, and one of them could be having students play high frequency word games. You could also spend a week as a class doing reader's theater or partner plays during fifteen minutes. You can pass out scripts and assign parts, and you have students practice their parts during that time, and then they can perform them at the end of the week. You have quite a few options for your fluency building time.

Let's do a quick review. When you plan your daily schedule you want to make sure that you're focusing first on skills, not on activities. I recommend having a whole class interactive read aloud, at least one, where you focus on comprehension vocabulary. This is a planned time, it's not just pulling a book off the shelf. You have small group phonics lessons. You've assessed your students using a good assessment tool, which includes nonsense words. You're grouping them and then in those groups, you're doing a quality phonics lesson. You can go to my blog post, "Do's and Don'ts for Teaching Phonics" to see what would be included there.

Also, I forgot to mention this before, but I was including phonemic awareness in those phonics lessons. When you head to that blog post I mentioned, it's going to show you that phonemic awareness should be part of the warmup. But you can certainly also schedule a whole class phonemic awareness lesson in your day as well. Many teachers use a program like Heggerty for this.

You're also going to be having time for students to read independently if they are at that point. This is so they can orthographically map the words. It's not to help them become people who love reading, although we certainly hope that will occur. The main goal is to help them become stronger readers. Then you will also have time during the day where students can build fluency.

I hope this was helpful as you think about applying the science of reading to your classroom. If you're listening to this in real time, today is the day that our online course, Teaching Every Reader, is open for public enrollment. It's open October 4th, 2021 through October 11th. Please head to teachingeveryreader.com to learn more.

Thanks so much for listening to the science of reading bootcamp series!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related postDo’s and don’ts for teaching phonicsMore episodes in the Science of Reading BootcampEpisode 1: 3 reasons why there’s so much disagreement around the science of readingEpisode 2: How we read and remember wordsEpisode 3: The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading RopeEpisode 4: What IS structured literacy, anyway?Episode 5: What does research tell us about the Big 5?

If you’re ready to learn more, you’re invited to check out our online course, Teaching Every Reader!

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR ONLINE COURSE

The post How to structure the reading block in a science of reading classroom appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 26, 2021

What does research tell us about the Big 5?

We know that the science of reading isn’t a curriculum, a fad, or a pendulum swing. It’s a body of research. So what does this research tell us about the Big 5? What does the science of reading have to say about phonological/phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary? In this episode we’ll examine the research and make practical applications to our teaching. Share this 6-week podcast series with friends who want to learn more about the science of reading. Also check out our online course, Teaching Every Reader! It opens for enrollment on October 4, 2021. Get the details here.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello! You are listening to the Science of Reading Bootcamp, Episode Five, and we're going to talk about what the research says about the Big Five.

As we stated previously, the science of reading is not a curriculum. It's not a fad, and it's not a pendulum swing. It's a body of research. Today we're going to look at what this body of research has to say about phonological and phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary - the Big Five!

Before we do that, though, I'd like to tell you a little bit about our online course, "Teaching Every Reader", which will open for enrollment on October 4th. Inside that course, we have eight modules. Each module is a mixture of video and text, and all the videos have transcripts that you can print and read. The first module is called "The Big Picture". In that module, you'll get a solid understanding of the science of reading.

Module two is about building a foundation of oral language and modules three to seven are about The Big 5. Finally, module eight is all about putting it together, taking the science of reading and applying it to how you set up your daily schedule, how you form small groups, how you differentiate, how you keep the other students busy and learning. It's the nuts and bolts. What sets our course apart from other courses about the science of reading is the huge amount of student resources. When you join, not only will you get permanent access to all the modules, you will also get dozens and dozens of printable student materials, including editable activities that will help you as you teach the Big Five! So remember to mark your calendar and head to teachingeveryreader.com to join the waitlist.

In today's episode, we're going to take a look at some research related to each of the Big Five, and then give some specifics as to how this would impact your teaching. Let's start with phonological and phonemic awareness. As always, I like to give definitions because these terms are easily confused.

Phonological awareness involves identifying and manipulating units of oral language. It's an umbrella term. It includes word awareness, rhyming ability, syllable awareness, understanding of onsets and rhymes, alliteration, and phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness has to do with the smallest part of a word, the phoneme, the individual sounds.

Phonemic awareness has to do with the ability to isolate, blend, segment, and manipulate individual sounds in words. The key thing that research tells us about phonemic awareness is that phonemic awareness is central to developing a large sight word vocabulary.

Really quickly, let's review. How do words become part of our permanent sight vocabulary? How do we recognize them instantly without needing to sound out or guess? It's not that we store individual pictures of each word in our brains. We recognize words instantly because we're good at two things, phonetic decoding and orthographic mapping. Phonetic decoding is sounding out words and orthographic mapping is remembering words for the future for instant retrieval so you don't need to sound them out. Otherwise reading would be extremely tedious if we had to do that every time we were reading, if we had to sound out every word letter by letter! You don't need to do that anymore! Unless perhaps you come to a surprise word, perhaps a long scientific word that you've never read before.

To be able to do phonetic decoding, you must know letters and sounds and be able to blend phonemes. To be able to do orthographic mapping, you must have letter sound proficiency and phonemic proficiency, so you have to be very good at phonemic awareness.

Remember words are connected in memory by connecting pronunciations to written spellings. For the word "cat", we connect /k/, /ă/, /t/, to the letters of the word. we're connecting the known - the sounds, to the new - the word "cat". That's why phonemic awareness is so important. It helps us remember words for the future!

What implication does this have for your classroom? Well, particularly in pre-k, kindergarten, and first grade, perhaps even in second grade, we're going to make phonemic awareness instruction part of the day. This should include oral exercises that help students learn to do all the parts of phonemic awareness, particularly phoneme manipulation, which is what is going to help them become strong readers. Phoneme manipulation has to do with adding and subtracting phonemes or substituting phonemes.

As for what you should use to teach phonemic awareness, many teachers enjoy the program Heggerty, which is just a collection of oral exercises that you do every day for about 10 minutes. Also, there are some one minute phonemic awareness activities in the back of David Kilpatrick's book, "Equipped for Reading Success". There's even a free phonemic awareness curriculum you can get at "Reading Done Right," and that's high quality as well. You could try any of those!

As we talked about last week, cumulative practice, that constant review, is a key practice of structured literacy. So I think that in addition to doing these oral activities, it's very helpful to put phonemic awareness activities at your centers.

Now, the challenge of course is how can they build phonemic awareness at a center when it's an oral activity and there's no teacher there to do the oral work? Actually, I've created a whole bundle of phonemic awareness games that students can play. The games use pictures, and this allows them to practice phonemic awareness to get that cumulative practice in when you're not sitting right next to them. In fact, if you'd like to get this bundle of games for 40% off, you can do that when you visit themeasuredmom.com/phonemicawareness. Be aware that as soon as you get to that page, a timer will start and you'll need to purchase before the timer runs out to get them for the 40% off, but that timer should give you enough time to read through the page and see if that bundle of activities is right for you. Again, that link is themeasuredmom.com/phonemicawareness.

Let's move now to phonics. What is phonics? A definition from Wiley Blevins in "A Fresh Look at Phonics" is that, "Phonics instruction teaches students how to map sounds onto letters and spellings." Research tells us a lot about phonics instruction, and I'm just going to focus on some key summaries of the research.

In 1967, Jeanne Chall wrote her book, "Learning to Read: The Great Debate". She analyzed the data, did a ton of research, and concluded that, "by an overwhelming margin, the programs that included systematic phonics resulted in significantly better word recognition, better spelling, better vocabulary, and better reading comprehension, at least through the third grade."

In 1985, there was a study of research which was published as a report, "Becoming a Nation of Readers". The report stated that teachers of beginning reading should present well-designed phonics instruction. Phonics is more likely to be useful when children hear the sounds associated with most letters, both in isolation and in words, and when they are taught to blend together the sounds of letters to identify words.

Finally, we have the National Reading Panels report published in the year 2000, and the report stated that phonics instruction enhances children's success in learning to read and systematic phonics instruction is significantly more effective than instruction that teaches little or no phonics. Phonics instruction increases the ability to comprehend text for beginning readers and older struggling readers.

All right, so that's the research. What we've basically learned is that systematic phonics instruction is important. Systematic is much better, much more efficient, and more effective than a haphazard approach.

Let's go back to what we talked about last week with the key practices of structured literacy and apply those to how we teach phonics.

Number one, your phonics instruction needs to be explicit. You will come right out and say what you want your students to know. Rather than giving them a list of words that have the letters "ee" and help them try to figure out how the words are the same and what those letters might be saying, you're just going to come out and say it. You'll say, "In some words, we use the letters "ee" to represent the long e sound. Here is a list of words that use "ee" to represent the long e sound."

Your instruction also needs to be systematic. You will have routines in your phonics lessons that help your students master the content. My recommendation for a good solid phonics lesson includes the following: phonemic awareness warmup, explicitly teach the new skill, practice blending with the new sound spelling pattern, do word building with the new sound spelling pattern, read decodable text featuring the new sound spelling pattern, and do guided writing, such as dictation, which again features the new sound spelling pattern.

Let's go back to the key practices of structured literacy again. Your phonics lessons should be sequential. You will go in order using a solid scope and sequence.

Your phonics instruction will be cumulative. You will mix in review, likely at literacy centers.

Finally, it will be diagnostic. You won't just blindly follow your curriculum without testing your students first. You will assess them, see where they're at, and then know where to begin and when to slow down and repeat. Personally, I recommend a small group rather than whole group phonics lessons. We'll talk more about that next week.

The third of the Big Five is fluency. As you know, fluency is the ability to read accurately, at an appropriate rate, and with proper expression.

As we think about fluency, it's important to think about its role in the simple view of reading. Decoding, or word recognition, is the ability to read and understand the words on a page. To build the skill of decoding, we teach phonemic awareness and phonics.

The next part of the simple view of reading is language comprehension. It's the ability to make sense of the language we hear and the language we read. To build language comprehension, we teach vocabulary and text comprehension. When you multiply decoding and language comprehension, you get reading comprehension.

So fluency is not explicitly presented in the simple view of reading, but here's where it fits in. Fluency is the automatic application of decoding and language skills. It's often talked about as a bridge between the early stages and the later stages of reading. The early stages include oral language, phonemic awareness, and phonics, as well as high-frequency words. Later stages include increased reading skills and comprehension.

Jan Hasbrouck is a big expert in the field of reading fluency. She wrote a book with Deb Glaser called "Reading Fluency". In that book, they write this, "If readers do not develop adequate levels of fluency, then they can become stuck in the middle of the bridge, able to decode words, but with insufficient automaticity to adequately facilitate comprehension. These students typically become our reluctant readers, often with dire consequences for themselves."

They have another metaphor for fluency. "Fluency is a doorway that leads to comprehension and increased motivation." According to Hasbrouck and Glaser, "If that fluency door remains closed than access to the meaning of print and the joy of reading is effectively blocked."

You see research tells us that for comprehension to occur, fluency must be present. And this means we cannot leave fluency building to chance! There are things we must do to make sure fluency develops.

Number one of course is to teach phonic decoding because without that students cannot be fluent. Number two, is to actually plan for and schedule activities that promote fluency. As tough as it sounds, I recommend incorporating fluency practice every day in grades one to three, and there are many ways to build fluency.

Let's just list a few of those. Number one, you can do whole class or small group echo reading. You model how to read a text and students echo you, matching your phrasing as much as possible as they reread it. Please note, this is not a recitation activity. It's actual reading. Make sure you gradually increase the amount of text that students echo so they're not just relying on their memory. They're actually reading the words after you read the words, but they're trying to match your phrasing and your expression.

You can also do whole group or small group choral reading. You will read together! It will give them practice, again developing automaticity and expression.

You may have heard of timed repeated reading, but I have read through the research that this is not recommended for everybody. It's more of an intervention strategy, and they have found a lot of success with it when they use it with students who really need to build their fluency, so their words per minute are very low. This is when a student reads for one minute, and then tries to beat their rate and accuracy with successive one minute readings. Don't use this with everyone. It's best as an intervention strategy for slow but accurate readers who need intense practice to increase automaticity. That's from the CORE "Teaching Reading Sourcebook".

You can also have your students play word reading games because one way they're going to be more fluent, more automatic, is to know those high-frequency words. So it's a good idea to play games, and practice those words they're going to see over and over.

You could do partner plays or reader's theater. I have both partner plays and reader's theater scripts in my shop. I'll link to those in the show notes.

And finally, you want to give your students daily time to read text at their independent or instructional level. A lot of times when you read things about the science of reading or structured literacy, people will often say that a structured literacy classroom does not have a lot of time for students to read independently. I really don't like that. I think that's a mis-characterization of what structured literacy is all about.

What they really mean is that you shouldn't have kids have a time of the day where they pick any old book and then sit down and read it. Because for some kids, they're not actually going to be reading. The most struggling readers aren't going to have success with that, and it's not going to help them. Whereas your strong readers are probably reading in their free time anyway.

I recommend making sure that each student in K-2 has a bag of decodable books they can read every day. For students who are ready for leveled books, those should be in the bags as well. I did not say they should grab any old book off the shelf and read for fluency practice. Work with them to choose their books and hold them accountable. Listen to them read whenever possible, and when they're ready, help them choose new books that will help them practice what they have learned.

Let's move on to the next one of the Big Five, and that is reading comprehension. What does research say about reading comprehension? Well, here's what it doesn't say. It doesn't say we have to choose between teaching strategies or building knowledge. That's like choosing between process and product. It doesn't have to be one or the other. It also doesn't say that our focus should only be on decoding because comprehension will just happen and doesn't need to be explicitly taught.

Unfortunately, these false ideas exist even within the science of reading community. That's why it's important to educate ourselves on what the research really says! In their summary of the research in the book, "Fundamentals of Literacy Instruction and Assessment", Hougen and Smartt wrote this,

"For comprehension to occur successfully, readers must purposefully and actively construct meaning as they navigate their way through the text. They do this by relying on background knowledge and making connections while considering the meanings of words and how the text is organized. Readers also make inferences, determine what information is most important in the text, and create mental images of the text."

I know that was pretty deep. Let's look at some highlights from a recent article in "The Reading Teacher" called "The Science of Reading Comprehension" by Nell Duke, Alessandra Ward, and David Pearson. Here's some highlights from their article. Number one, word reading is necessary, but not sufficient for reading comprehension. And you knew this, right? It's obvious from the simple view of reading. Children need to be able to sound out words, but that's not enough. They must also have language comprehension.

Next, reading comprehension is not automatic, even when fluency appears strong. Even though a student may sound like a fluent reader, that doesn't guarantee comprehension. It's not automatically achieved when students can read words quickly. This is when it's helpful to remember Scarborough's Reading Rope. There are many strands in the language comprehension domain. The research also tells us that comprehension instruction should begin early. Here's a quote from that science of reading comprehension instruction article.

"Research has supported a simultaneous rather than sequential model of reading instruction. Along with development of phonological awareness, print concepts and alphabet knowledge, young learners in preschool and early elementary school benefit from efforts to develop oral language comprehension, including efforts to develop oral comprehension of written language. As young learners begin to read texts themselves, comprehension instruction alongside phonics and other foundational skills instruction has an important place."

Have you ever heard people say that in the primary grades children learn to read, and in the later grades they read to learn? I hear that all the time, and I used to really, really hate that. But the fact is there's a lot of truth to it. At the very early stages, students cannot comprehend what they're reading because they're not reading fast enough. They really have to develop some automaticity with word recognition and fluency of rhythm to be able to free up more of their brains for comprehension.

So there's something to be said for in the early grades they learn to read, and that in the later grades they read to learn, BUT that doesn't mean that we just put comprehension off to the side until students get to third grade. At first, students benefit from oral language comprehension, which we can develop through whole class read alouds. Then as they begin to read the texts themselves, more specific comprehension instruction can take place.

Research tells us that teaching text structures and features fosters reading comprehension development. The research also tells us that vocabulary and knowledge building support reading comprehension development, and it tells us that comprehension strategy instruction improves reading comprehension.

Now those strategies include things like inferring, monitoring comprehension, predicting, and so on. I want to be clear that some teachers, myself included, have gone about comprehension strategy instruction in the wrong way. We viewed it as a product rather than a process, but poor implementation of it in the past does not justify abandoning comprehension instruction. There's been a history of doing it wrong, but that doesn't mean it's not important! We just need to do it right.

Here's a quick summary of the application of the research regarding reading comprehension. We are going to teach text structures and text features. We're going to build background knowledge. We're going to teach reading comprehension strategies, but we primarily do all these things through interactive read alouds until students can read longer texts that lend themselves to instruction and practice with these skills.

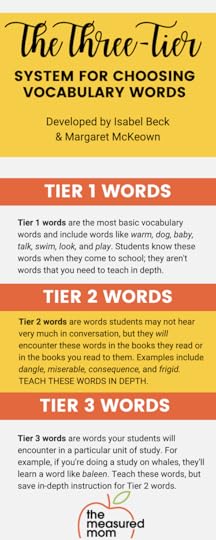

Finally, we are now on the last of the Big Five: vocabulary. Vocabulary is the knowledge of words and their meanings. For many decades, researchers have noted that there is a strongly correlated relationship between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension. And that makes perfect sense, right? If you try to read a manual for repairing something and you don't know what all the parts are, the manual is not going to make a whole lot of sense. If you're great at sounding out words, but you're reading a textbook about something you don't understand and have never studied, it's not going to make sense to you. We've got to know those vocabulary words.

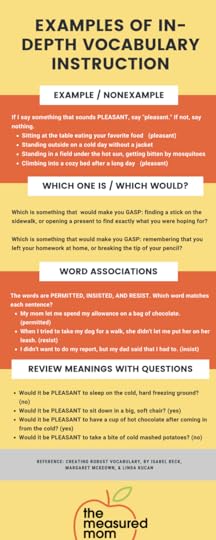

In the book, "Creating Robust Vocabulary", the authors give us a summary of some of the research and they tell us that in 1999 and 2002 researchers discovered that kindergarten vocabulary knowledge could predict reading comprehension of students two years later in second grade. A 1997 study found this relationship held through fourth grade. Another 1997 study showed that vocabulary knowledge in first grade predicted students' reading comprehension in their junior year of high school.

Unfortunately, research also tells us that traditionally vocabulary instruction in schools has not been strong. It isn't to say that reading programs don't give attention to new vocabulary words. They do. Typically, there are new vocabulary words introduced with each story, but the attention paid to these words in the curriculum is brief, and there are very few opportunities to review.

Let's look at some more research. In "The Vocabulary Book", Michael F. Graves tells us that instruction that involves activating prior knowledge and comparing and contrasting word meanings is likely to be more powerful than simply combining context and definitions. He also tells us that more lengthy and robust instruction that involves active learning, connecting to prior knowledge, and frequent encounters, is likely to be more powerful than less time-consuming and less robust instruction. In other words, briefly discussing a new word is not enough. Looking up words and copying their definitions won't cut it.

According to Michael Graves, there are four components of an effective vocabulary program, so this is our application of the research. You want your students to be doing wide or extensive independent reading. Now, of course, with our early, early kids, that's going to be us reading to them. You want to give instruction in specific words to expand the understanding of the text that has those words. So when you're reading aloud to your students, you want to pull out words and spend time with them, not necessarily during the reading, but after or before. You're going to give your students instruction in independent word learning strategies. In other words, you'll show them how to use context or a dictionary to find word meanings, and you can do word consciousness and wordplay activities.

That may be our longest podcast episode so far! We talked about the Big Five and what the research says about them, and how you can take that research and apply it to what you're doing in your classroom.

Next week is the final episode in our Science of Reading Bootcamp, and that's where we get into the nuts and bolts. What exactly could your day look like when you are applying the recent research?

Again, remember that you can check out our course, and teachingeveryreader.com is where you could get on the wait list. The course opens on October 4th.

Thanks so much for listening and I'll talk to you again next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

More episodes in the Science of Reading BootcampEpisode 1: 3 reasons why there’s so much disagreement around the science of readingEpisode 2: How we read and remember wordsEpisode 3: The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading RopeEpisode 4: What IS structured literacy, anyway?Related products in my shopSpecial offer on my phonemic awareness activitiesPartner playsReader’s theater scriptsEditable word reading gamesReading comprehension passages: Famous PeopleReading comprehension passages: Biomes & HabitatsBooks & ResourcesJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.Heggerty phonemic awareness curriculumEquipped for Reading Success, by David Kilpatrick (one-minute phonemic awareness drills)Free phonemic awareness curriculum curriculum at Reading Done RightA Fresh Look at Phonics, by Wiley BlevinsLearning to Read, by Jeanne ChallBecoming a Nation of Readers reportNational Reading Panel reportReading Fluency, by Jan Hasbrouck & Deb GlaserThe Core Teaching Reading Sourcebook, by Bill Honig, Linda Diamond, & Linda GutlohnThe Fundamentals of Literacy Instruction & Assessment, by Hougen & SmarttThe Science of Reading Comprehension (article in The Reading Teacher), by Nell Duke, Alessandra Ward, & David PearsonCreating Robust Vocabulary, by Isabel Beck, Linda Kucan, & Margaret McKeownThe Vocabulary Book, by Michael Graves

The post What does research tell us about the Big 5? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 19, 2021

What IS structured literacy, anyway?

Structured literacy is all the rage these days, but what exactly is it? Today we’ll discuss the HOW and the WHAT of structured literacy. Share this 6-week podcast series with friends who want to learn more about the science of reading. Also check out our online course, Teaching Every Reader! It opens for enrollment on October 4, 2021. Get the details here.

Key Practices (the HOW of structured literacy)

ExplicitSystematicSequentialCumulativeDiagnosticElements (the WHAT of structured literacy)

PhonologySound-Symbol AssociationSyllable InstructionMorphologySyntax & SemanticsListen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, and welcome to the fourth episode in our Science of Reading Bootcamp. Today is another day that's a little bit more theory and less practical, but I promise next week we're going to get into the practical - the nuts and bolts. But this is really important to understand!

We're going to talk today about what structured literacy is. You hear that being tossed around a lot. You might wonder what exactly that means. How do you teach in a structured way? Does structured literacy equal boring?

I know that's certainly what I thought for a while. I really didn't want anything to do with it until I started studying the science of reading and realized there were some problems with my approach. I actually did an episode way back on April 19th, 2021. It was Episode 42, and I described the difference between balanced and structured literacy.

In this episode today, we're just going to zero in on structured literacy. What is it? How do you teach with a structured approach?

Well, to understand structured literacy, you only need to know two things: you need to know the key practices in structured literacy, and you need to know the elements.

The key practices are basically qualities of good teaching. You should be using those in whatever you're teaching, whether that's math, science, or reading.

I've chosen the word "elements" to refer to the content. You're going to be using these key practices as you teach this specific content.

In today's episode, I want to talk about the practices and the elements. There are five qualities of good teaching when it comes to structured literacy.

Number one: when you teach in a structured way, you are explicit. You come right out and say what you want your students to know! It's not a guessing game. You just come right out and say it.

Number two: be systematic. Being systematic means that you have predictable routines. You're not just making it up as you go along. For people who like to fly by the seat of their pants, being systematic can be hard. It can be hard to have routines that work for you, but students really respond to them. It's definitely something to figure out. A lot of programs come with routines they want you to use. I would say you can certainly modify them to fit your personality and your style, but in general, you want to stick to them as much as possible, especially if students will be using those same routines in other grades.

Number three: being sequential is the third key practice of structured literacy. That means you're teaching in order from easy to difficult. In other words, when you're teaching phonics, you're going to start with vowels, consonants, CVC words, and gradually move up to more complicated concepts, such as CVCE words, r-controlled vowels and so on.

Number four: Another practice is being cumulative. The concepts are reinforced and practiced over time. We don't just teach something and forget about it. We review it - a lot! A great place to do that is at your literacy centers. If you are teaching phonics in small groups at those literacy centers, that's where you give them things they've already learned, but you give them fun ways of practicing it.

Finally, number five: another key practice of structured literacy is being diagnostic. You're monitoring progress and adjusting instruction based on student needs. This can be tricky if you have a program and someone expects you to be exactly on the same page as everyone else in your building every day. That's when you need to educate somebody about what it means to be a diagnostic teacher, how you don't just teach the next thing because the book says to, but you teach it because your students are ready for it.

Some teachers solve this issue by meeting with students in small groups to help them understand the concepts they didn't grasp with the whole class. Personally, I think the best approach is to assess everyone and then teach phonics in small groups, but we'll get to that later in the series.

Those are the five key practices of structured literacy. They're qualities of good teaching. You should do them no matter what subject you teach. You want to be explicit, systematic, sequential, cumulative, and diagnostic. That's the first thing you need to know.

The second thing you need to know about structured literacy is that there are certain things we're going to teach within structured literacy. We're going to be explicit, systematic, sequential, cumulative and diagnostic when we teach these key elements. Now I actually have a whole blog series that I did with my colleague, Becky Spence, of "This Reading Mama", all about what structured literacy is and I will link to those episodes in the show notes.

Right now, I'll go through them very quickly. The first one is phonology. Phonology - phone - has to do with sound. That's about phonological awareness and specifically phonemic awareness. You remember that that has to do with the individual sounds in words, so we teach that.

We also teach sound-symbol association. in other words, phonics. The sound, /ē/, can be represented in a lot of ways. It can be represented with a single "e", as in "me". It can be represented with e-consonant-e, as in "here" and so on. Sound-symbol association is matching phonemes to graphemes. We're going to get very specific in our phonics instruction. We can teach that we spell the /k/ sound in different ways. We usually use "c" to spell /k/ before "a", "o", and "u", and we usually use "k" to spell the sound /k/ before "e" and "i". We use "ck" to spell /k/ at the end of a single syllable, short vowel word. You might teach even more complex spellings depending on the age or grade of your students.

The next element of structured literacy is syllable instruction. I'm not talking about clapping syllables, that goes back to phonology. I'm talking about teaching about the six syllable types and syllable division rules. You can learn more about this in the blog post series that I'll link to in the show notes. We also go into great detail about syllables and syllable instruction inside our online course, "Teaching Every Reader".

The next element is morphology. Morphology refers to morphemes, the smallest parts of words that have meaning. Things like prefixes, suffixes, and root space words. You'll be focusing more on that in the upper grades, but you can certainly do some of that in the lower grades as well.

Finally, we have syntax and semantics. That has to do with grammar and sentence structure, the mechanics of language. With our youngest students, we'll be addressing a lot of this through read alouds. But as students grow as readers, we can teach them these things and how to apply them to their own reading and writing.

That was today's episode. Let's review really quickly. If someone asks you, "What is structured literacy?", you can say, "Well, it has to do with how you teach and what you teach". In reference to how you teach, you should be explicit, systematic, sequential, cumulative, and diagnostic. In regards to what you teach, you teach your students phonology, phonics, syllable types and syllable division, morphology, and then syntax and semantics.

There's a lot to remember in this episode! I recommend heading to the show notes, themeasuredmom.com/episode48 and printing the transcript, so that you can have all of this at your fingertips and you don't have to remember all of it. Remember that our online course "Teaching Every Reader" will show you how to teach reading according to the science of reading and with a structured literacy approach, and that opens on October 4th, 2021.

Finally, the last two weeks of this Science of Reading Bootcamp are going to get very specific! Next week we'll talk about what the research says about the Big Five:phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary, and how that applies to how you teach them. Then the last week, we'll discuss the nuts and bolts of the science of reading.

We'll see you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

More episodes in the Science of Reading BootcampEpisode 1: 3 reasons why there’s so much disagreement around the science of readingEpisode 2: How we read and remember wordsEpisode 3: The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope

The post What IS structured literacy, anyway? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 12, 2021

The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope

If you study the science of reading, it won’t be long until you hear mentions of the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope. What are they? And what do they have to do with how we teach reading? Today’s episode will answer those questions. Share this 6-week podcast series with friends who want to learn more about the science of reading. Also check out our online course, Teaching Every Reader! It opens for enrollment on October 4, 2021. Get the details here.

VisualsSimple View of Reading

This diagram of The Simple View of Reading is from my online course, Teaching Every Reader.

Please visit the International Dyslexia Association’s website to see an image of Scarborough’s Reading Rope.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, and thank you for joining me for the third episode in our series of the Science of Reading Bootcamp. Today, we're going to talk about two models that are key pieces of the science of reading.

If you do any study into the science of reading, you're going to come across these. It's really important that you understand them. One is called the Simple View of Reading and one is called Scarborough's Reading Rope. I'll just tell you upfront, this is a little bit tricky on a podcast when you're just listening, because visuals are important. But if you head to the show notes, themeasuredmom.com/episode47, I'll give you some visuals and link to some visuals so you can make sense of what you're hearing.

First of all, let's talk about the Simple View of Reading. This was proposed by Gough and Tunmer in 1986. It is a formula demonstrating that reading has two basic components: word recognition (often referred to as decoding), and language comprehension. The formula is a multiplication problem. Imagine on the left, you have decoding, then you multiply that by language comprehension, and it equals reading comprehension.

Because it's a multiplication problem, you've got to have a score of above zero for each one in order for any kind of reading comprehension to occur. So if a child cannot decode, cannot sound out words, they would get a zero for decoding. Even though they do understand the language and get a one for language comprehension, their reading comprehension will still be a zero because zero times one equals zero.

So students must be able to decode AND understand the language for reading comprehension to occur. The reason that Gough and Tunmer proposed this model is because at the time, many educators did not feel that strong decoding was necessary to achieve reading comprehension if children have strong language abilities.

Now, I'll just come right out and say it, this was me for a while. When I taught kids to read using a balanced literacy approach, they were "reading" leveled books and using the pictures and the first letter to help them read a lot of the words. They were figuring out the words or something close to them, and they were getting something out of the text. So I thought they were achieving reading comprehension.

But it wasn't reading comprehension because they weren't truly reading! To be truly reading, they really have to pull those individual words off the page by being able to sound them out or by just knowing them because they have sounded them out in the past and have orthographically mapped the words.

So the simple view of reading tells us that decoding skills and understanding of language must both be present for reading comprehension to take place. You might say, "Okay, that feels rather obvious. What's the point? What are the implications?"

Well, the first implication is that we need to make phonic decoding a focal point of early reading instruction! It shouldn't be just something on the side that we teach as it comes up, which can often happen when you're using leveled books with beginning readers. For example, you might say, "Well, this page has "ee" in it. So I'll teach them really quick that "ee" says /ē/."

Now, there's nothing wrong with doing that occasionally, but you need to have a structured phonics program and decodable books that give them practice on what you're teaching them.

Of course, we also need to make sure that we are helping build their language comprehension by building their content knowledge through strong, interactive read alouds and lessons in social studies and science.

Something else to think about in relation to the Simple View of Reading is that when older students are struggling readers - they're not comprehending what they're reading, many times teachers jump to the conclusion that language comprehension is the issue. But it could be that the real issue is that the child never really learned to be good at decoding.

So my first few years of teaching, I was teaching a combined class of third, fourth, and fifth graders. I had a student who was in third grade. I taught her for all three years. She was a brilliant artist, but she really struggled with reading. I wish I knew then what I know now! Looking back, thinking back to the errors she made, I know that she needed me to give her a phonics assessment with both real and nonsense words so that I could tell which phonics skills she had mastered. Then I needed to give her direct instruction in those phonics patterns.

There could also be the opposite issue. You could have a student who is brilliant at sounding out words, but struggles to make sense of text. This child may need more instruction in vocabulary, verbal reasoning, syntax, and so on. Or you may have a student who struggles in both areas.

The point which we can get from the Simple View of Reading is that you need to assess both a child's decoding ability AND language comprehension to be able to make a plan to help the child. So that's model one and I will have a visual of that in the show notes, themeasuredmom.com/episode47.