Anna Geiger's Blog, page 26

August 26, 2021

Do’s and don’ts for teaching comprehension

It’s week four of our deep dive into “The Big Five!” So far we’ve explored phonemic awareness, phonics, and fluency. Today we’ll take a look at do’s and don’ts for teaching comprehension.

Have you ever heard people say that in the primary grades, children “learn to read” and in the later stages they “read to learn”? There’s some truth to that. At the very early stages, students cannot comprehend what they’re reading because they’re not reading fast enough.

They have to develop some automaticity with word recognition and fluency of rhythm to be able to free up more of their brains for comprehension.

However, the act of teaching comprehension isn’t something we should push off to a later date.

In their recent article in The Reading Teacher, The Science of Reading Comprehension Instruction, Duke, Ward & Pearson have this to say:

Given the absolute necessity of foundational word-reading skills, it is tempting to think that instruction should begin with a focus on developing those and later turning to comprehension.

Nell K, Duke, Alessandra E. Ward & P. David Pearson

However, research has supported a simultaneous, rather than sequential model of reading instruction.

Along with development of phonological awareness, print concepts, and alphabet knowledge, young learners in preschool and early elementary school benefit from efforts to develop oral language comprehension …

As young learners being to read texts themselves, comprehension instruction, alongside phonics and other foundational skills instruction, has an important place.

We might ask … how do we teach comprehension when students aren’t doing much reading? Or when the reading they do is slow and tedious because they’re still learning phonic decoding?

The answer lies in reading aloud to your students.

An interactive read aloud is not when you grab a book off the shelf to fill five minutes. While that’s certainly a good thing to do, an interactive read aloud is something you plan for.

You choose a book before you meet with your students, determine teaching points (such as skills and vocabulary), and (if you’d like) jot them down on sticky notes. Put those notes at the places in the book where you plan to stop and talk. Then read and enjoy!

In an interactive read aloud you might …

In an interactive read aloud you might …Do these things before you read

talk about the author and illustratortake a sneak peek at the book before you read (read the back or inside summary)examine the table of contentsinvite students to discuss what they already know about the topicmake predictions about what will be in the textDo these things as you read

stop to examine new vocabulary wordsthink aloud as you readinvite students to make connections to the textencourage students to interact with the book by having them talk to a partner, act out a sentence or short part of the book, make a quick sketch or note, or participate in a class discussionDo these things after you read

ask students to retell the storyhave students name things they learnedcheck predictionsWhen you ask thought-provoking and open-ended questions, your students will engage in high-level thinking. With your help, they will have thoughtful discussions with you and their classmates.

The products of reading comprehension are demonstrations of what the reader knows and understands AFTER reading.

Examples of reading comprehension products include:

Answering text-based questionsWriting a summaryCompleting a worksheet about a bookRetelling a storyCompleting a graphic organizer about a textIn contrast, a reading comprehension process is a skill or process that students have which enables them to create the product.

Examples of reading comprehension processes include:

Making inferencesMonitoring comprehensionMaking predictionsAsking questions while readingWhat’s the point, you ask?

The point is that, too often, we have our students complete products and think that we’re teaching comprehension.

We’re not.

When you assign a worksheet with questions after students read a story, you’re not teaching comprehension. You’re assessing comprehension.

Teaching and assessing both have their place, but let’s not fool ourselves into thinking we’re teaching when we’re just checking understanding.

We must make time to explicitly teach reading comprehension processes.

It troubles me when I hear some people in the science of reading community claim that once students are proficient with decoding and reading fluently, comprehension will “just happen.”

We can’t (and shouldn’t!) count on that. Comprehension is just like everything else in a structured literacy classroom. We must explicitly teach it.

In recent years, reading comprehension strategy instruction has come under attack. This may be for good reason; some teachers (I’m raising my hand here!) have focused so much on the process that they almost forget about the product.

For example, a reading lesson becomes more about learning the skill of activating prior knowledge than about actually learning the life cycle of a frog.

Here’s a key thing to remember:

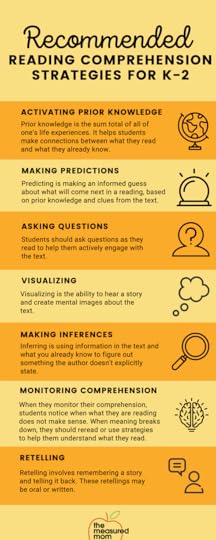

Reading comprehension strategies should be taught as TOOLS to help students comprehend text. They are not an end in themselves.All that said, researchers tells us that even primary students benefit from reading strategy instruction (and – you guessed it – a lot of this instruction will happen through explicit modeling during interactive read alouds).

Here’s an infographic with the strategies to emphasize in the early grades.

As you’re planning your interactive read aloud, whole group lessons in which students read grade-level text, or small group lessons, take some time working through a template like this one.

This template is based on the Berger Framework:

Summary of understandings: What themes or concepts do you want your students to learn from this text?Text challenges to address: What challenging sentence structure, inferences, etc. will students need help with?

Before reading: What will you do to prepare students to read? You might activate/build prior knowledge, introduce vocabulary, and/or set a purpose for reading.

During reading: Where will you stop to analyze text structure, ask a question, make an inference, etc.?

After reading: What questions will you ask, how will you teach vocabulary, and what independent work (if any) will students do in response to the text?

If you’re looking for texts for students to read when using the above framework, I’ve got great news! I have a variety of reading comprehension passages in my shop. Get a FREE sample at the end of this post.

Let’s sum up!DON’T wait to teach reading comprehension. Researchers tell us that students can learn comprehension alongside other early reading skills.DO spend time preparing powerful interactive read alouds … the ideal time to teach comprehension to our youngest readers.DON’T confuse reading comprehension processes and products. Giving worksheets isn’t teaching students how to comprehend; it’s assessing them.DO teach reading comprehension strategies.DO consider using a lesson plan template when planning reading comprehension lessons. Download the free reading passage at the end of the post and give it a try!

Free reading passages

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The post Do’s and don’ts for teaching comprehension appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Do’s and don’ts for teaching reading fluency

Have you been following along with our series about the Big 5? So far we’ve tackled phonemic awareness and phonics. Now it’s time to discuss the do’s and dont’s for teaching reading fluency.

As I look back on my years as a balanced literacy teacher, I realize that I misunderstood fluency and its place in the big picture.

I was opposed to decodable books because I thought that leveled books, with their predictable language, helped students become fluent readers.

Since my students could “read” those predictable sentences quickly and easily, I thought this was building their fluency.

In contrast, I was troubled when I heard students slooowwlly sound out words in decodable books. I felt that it negatively impacted fluency and comprehension. I felt the same concern that Margaret Goldberg wrote about in her blog post, The Drudgery (and Beauty) of Decodable texts.

“Sounding out each word took so long that by the time they got to the end of a sentence, students didn’t know what they had read. I worried that I was creating ‘word callers’ (and they weren’t even calling the words very well!)”

As Goldberg studied the science of reading, she learned the same thing that I did: students have to do the hard work of sounding out words to become proficient readers.

Fluency will not happen right away.

While they can learn comprehension through whole class read alouds, comprehension of the texts they read themselves will not happen right away.

I can best explain the proper place of fluency through a video excerpt from the Fluency Module of my online course, Teaching Every Reader.

Key takeaways from the video:

Fluency is the automatic application of decoding and language skills.Fluency is the bridge to comprehension.

It’s easy to go overboard with fluency assessments, or to feel so overwhelmed that you’re not sure where to start.

Good news! Assessing oral reading fluency can be quick and simple.

What gets confusing is all the acronyms and abbreviations. Let’s get those straight first.

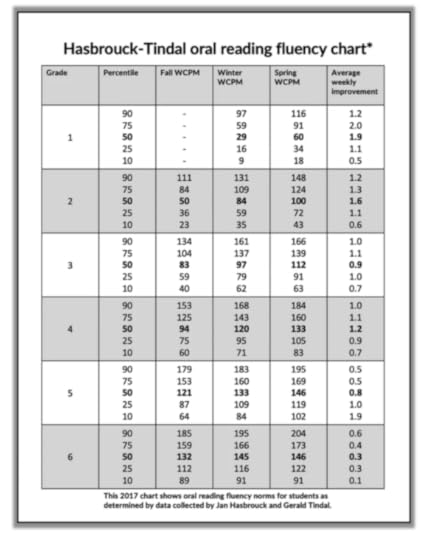

ORF: Oral reading fluency; it’s a combination of reading rate and accuracy.CBM: Curriculum based measurement; it’s the assessment tool that is most commonly used for measuring ORF.WCPM: Words correct per minute; it’s how we measure ORF.To conduct an ORF CBM assessment, listen to a student read aloud from an unpracticed, grade level passage for one minute. Follow along with a copy of the passage and mark any errors.

At the end of the one minute, determine the student’s ORF score by subtracting the number of errors from the total number of words word. The score is expressed as WCPM.

How often should you assess students’ oral reading fluency? Here’s a good plan:

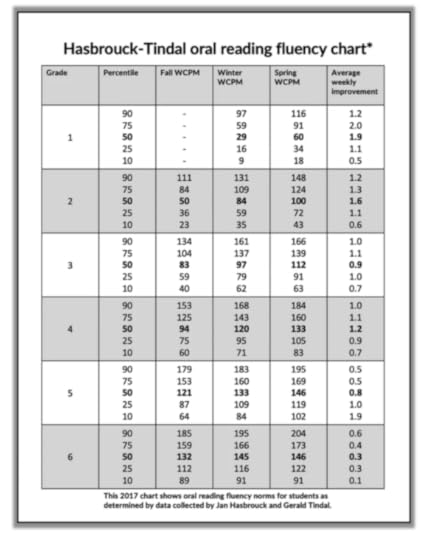

Assess first graders’ fluency in the winter and spring.For second grade and up, assess oral reading fluency in the fall, winter and spring.After assessing, be sure to compare student scores to the fluency norms as compiled by Jan Hasbrouck and Gerald Tindal.

If a child’s fluency is not within ten WCPM of the 50th percentile on the table, you should assess more often and keep track of the child’s progress on a chart.

With all that talk about assessing oral reading fluency, it’s important to remember that we do this to assess only one aspect of fluency.

As Jan Hasbrouck and Deborah Glaser write in their handbook, Reading Fluency, “ORF assessments yield results that can be interpreted and used for making decisions, yet provide only ‘one piece of the puzzle’ when determining overall wellness.”

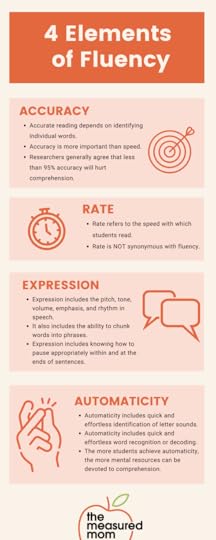

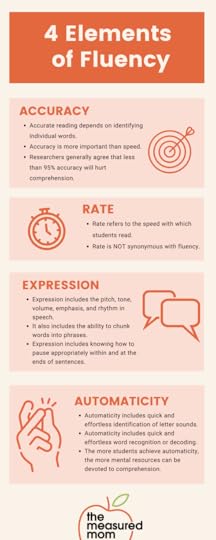

In fact, there are four key aspects of teaching reading fluency, which I’ve described in the following infographic:

Did you catch the bullets under AUTOMATICITY? Fluency isn’t just about reading words. We need students to be able to quickly identify letters, letter sounds, syllables, and more.

If you’re a student of my course, Teaching Every Reader, you can get a file of fluency drills for all levels in this lesson.

Prosody is all about to do with reading the way we speak – it’s about reading with phrasing, emotion, and emphasis, and rhythm (even inside our heads).

Teaching students to read with prosody is SUCH an important part of teaching reading fluency.

According to the authors Pamela E. Hook and Sandra D. Jones, in their chapter of the book Expert Perpsectives on Interventions in Reading, children must learn to read with expression in order to improve comprehension.

These experts tell us that students must transition from decoding text to constructing meaning by reading with prosody. “Making this connection allows a reader to self-monitor and self-correct, which in turn facilitates the comprehension of text.”

I can speak to this from my own experience. Of our six kids, one stands out as not being particularly interested in reading. (He’d rather shoot baskets, throw a football, or ride his bike any day!) He often reads aloud in a monotone voice, hardly stopping for punctuation.

When I ask him about what he just read, it’s no surprise that he has no idea! In contrast, when he and I read aloud together and I force him to stop and read with expression, his comprehension improves.

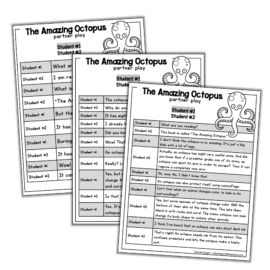

Use reader’s theater to build reading fluencyReader’s theater is an authentic way to get students to reread a text with expression – which builds fluency and improves comprehension.

Reader’s theater combines reading and performing. It requires no costumes or scenery.

You need a copy of the script for each group of students. As the teacher, you’ll assign roles and guide students as they practice reading their scripts. After several days of practice, students can perform their scripts for the class.

I especially love reader’s theater scripts in the form of partner plays!

Partner plays include only two parts, making them ideal for buddy reading and use at centers.

Here’s an audio recording of a partner play I read with my youngest (he just started kindergarten; I taught him to read at home before starting school using a structured literacy approach).

When you get to the end of this blog post, you’re invited to download all three levels of this partner play for FREE!

Fluency is important, but it’s often forgotten in the daily challenge of “fitting it all in.”

As tough as it sounds, I recommend incorporating fluency practice every day in grades 1-3.

If this sounds tedious, don’t worry. There are countless ways to build fluency!

Do whole class or small group echo reading, in which you model how to read a text, and students “echo” you, matching your phrasing as much as possible as they reread the text. This is not a recitation activity; it is reading. Make sure that you gradually increase the amount of text that students echo to prevent them from relying on their memory.Do whole group or small group choral reading. You and your students will read the text simultaneously; it will give them practice developing automaticity and expression.

For students who need a fluency intervention, use timed repeated reading. This is when a student reads for one minute and tries to beat their rate and accuracy with successive one-minute readings of the same text. But don’t use this with everyone. According to the authors of the Core Reading Sourcebook, timed repeated reading is best used “as an intervention strategy that is most appropriate for slow but accurate readers who need intense practice to increase their automaticity in reading connected text.”

Provide fluency drills at centers to give students practice naming letters and letter sounds. More advanced readers should practice reading syllables and single words. If you’re a member of my online course, Teaching Every Reader, you can head to this lesson to grab a big file of fluency drills.

Have students play word reading games in pairs or small groups. (My collection of editable reading games is perfect for this.)

Spend a week doing partner plays or reader’s theater (zip to the end of this post to download a free script in three levels!).

Give students daily time to read text at their independent or instructional level. Phonics lessons are great, but students must practice what they’re learning by reading connected text. I recommend making sure that each student has a bag of decodable texts that s/he can read every day. For students who are ready for leveled books, those should be in the bag as well. Note that I did not say that kids should grab any old book off the shelf and read for fluency practice. Work with your students to choose their books, and hold them accountable. Listen to them read whenever possible.Let’s sum up!DO understand the role of fluency in the big picture of learning to read. Fluency is the bridge to comprehension.DO assess oral reading fluency at different points of the year for first grade and up.DON’T focus only on reading rate. Fluency includes accuracy, rate, expression, and automaticity.DO provide authentic experiences for students to practice reading with expression. Partner plays are my favorite tool for this! Scroll down to get a FREE script.DON’T forget to make time for daily fluency building.

CLICK HERE FOR A PRINTABLE VERSION OF THIS BLOG POST

Free partner play in 3 levels

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The post Do’s and don’ts for teaching reading fluency appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Do’s and dont’s for teaching reading fluency

Have you been following along with our series about the Big 5? So far we’ve tackled phonemic awareness and phonics. Now it’s time to discuss the do’s and dont’s for teaching reading fluency.

As I look back on my years as a balanced literacy teacher, I realize that I misunderstood fluency and its place in the big picture.

I was opposed to decodable books because I thought that leveled books, with their predictable language, helped students become fluent readers.

Since my students could “read” those predictable sentences quickly and easily, I thought this was building their fluency.

In contrast, I was troubled when I heard students slooowwlly sound out words in decodable books. I felt that it negatively impacted fluency and comprehension. I felt the same concern that Margaret Goldberg wrote about in her blog post, The Drudgery (and Beauty) of Decodable texts.

“Sounding out each word took so long that by the time they got to the end of a sentence, students didn’t know what they had read. I worried that I was creating ‘word callers’ (and they weren’t even calling the words very well!)”

As Goldberg studied the science of reading, she learned the same thing that I did: students have to do the hard work of sounding out words to become proficient readers.

Fluency will not happen right away.

While they can learn comprehension through whole class read alouds, comprehension of the texts they read themselves will not happen right away.

I can best explain the proper place of fluency through a video excerpt from the Fluency Module of my online course, Teaching Every Reader.

Key takeaways from the video:

Fluency is the automatic application of decoding and language skills.Fluency is the bridge to comprehension.

It’s easy to go overboard with fluency assessments, or to feel so overwhelmed that you’re not sure where to start.

Good news! Assessing oral reading fluency can be quick and simple.

What gets confusing is all the acronyms and abbreviations. Let’s get those straight first.

ORF: Oral reading fluency; it’s a combination of reading rate and accuracy.CBM: Curriculum based measurement; it’s the assessment tool that is most commonly used for measuring ORF.WCPM: Words correct per minute; it’s how we measure ORF.To conduct an ORF CBM assessment, listen to a student read aloud from an unpracticed, grade level passage for one minute. Follow along with a copy of the passage and mark any errors.

At the end of the one minute, determine the student’s ORF score by subtracting the number of errors from the total number of words word. The score is expressed as WCPM.

How often should you assess students’ oral reading fluency? Here’s a good plan:

Assess first graders’ fluency in the winter and spring.For second grade and up, assess oral reading fluency in the fall, winter and spring.After assessing, be sure to compare student scores to the fluency norms as compiled by Jan Hasbrouck and Gerald Tindal.

If a child’s fluency is not within ten WCPM of the 50th percentile on the table, you should assess more often and keep track of the child’s progress on a chart.

With all that talk about assessing oral reading fluency, it’s important to remember that we do this to assess only one aspect of fluency.

As Jan Hasbrouck and Deborah Glaser write in their handbook, Reading Fluency, “ORF assessments yield results that can be interpreted and used for making decisions, yet provide only ‘one piece of the puzzle’ when determining overall wellness.”

In fact, there are four key aspects of teaching reading fluency, which I’ve described in the following infographic:

Did you catch the bullets under AUTOMATICITY? Fluency isn’t just about reading words. We need students to be able to quickly identify letters, letter sounds, syllables, and more.

If you’re a student of my course, Teaching Every Reader, you can get a file of fluency drills for all levels in this lesson.

Prosody is all about to do with reading the way we speak – it’s about reading with phrasing, emotion, and emphasis, and rhythm (even inside our heads).

Teaching students to read with prosody is SUCH an important part of teaching reading fluency.

According to the authors Pamela E. Hook and Sandra D. Jones, in their chapter of the book Expert Perpsectives on Interventions in Reading, children must learn to read with expression in order to improve comprehension.

These experts tell us that students must transition from decoding text to constructing meaning by reading with prosody. “Making this connection allows a reader to self-monitor and self-correct, which in turn facilitates the comprehension of text.”

I can speak to this from my own experience. Of our six kids, one stands out as not being particularly interested in reading. (He’d rather shoot baskets, throw a football, or ride his bike any day!) He often reads aloud in a monotone voice, hardly stopping for punctuation.

When I ask him about what he just read, it’s no surprise that he has no idea! In contrast, when he and I read aloud together and I force him to stop and read with expression, his comprehension improves.

Use reader’s theater to build reading fluencyReader’s theater is an authentic way to get students to reread a text with expression – which builds fluency and improves comprehension.

Reader’s theater combines reading and performing. It requires no costumes or scenery.

You need a copy of the script for each group of students. As the teacher, you’ll assign roles and guide students as they practice reading their scripts. After several days of practice, students can perform their scripts for the class.

I especially love reader’s theater scripts in the form of partner plays!

Partner plays include only two parts, making them ideal for buddy reading and use at centers.

Here’s an audio recording of a partner play I read with my youngest (he just started kindergarten; I taught him to read at home before starting school using a structured literacy approach).

When you get to the end of this blog post, you’re invited to download all three levels of this partner play for FREE!

Fluency is important, but it’s often forgotten in the daily challenge of “fitting it all in.”

As tough as it sounds, I recommend incorporating fluency practice every day in grades 1-3.

If this sounds tedious, don’t worry. There are countless ways to build fluency!

Do whole class or small group echo reading, in which you model how to read a text, and students “echo” you, matching your phrasing as much as possible as they reread the text. This is not a recitation activity; it is reading. Make sure that you gradually increase the amount of text that students echo to prevent them from relying on their memory.Do whole group or small group choral reading. You and your students will read the text simultaneously; it will give them practice developing automaticity and expression.

For students who need a fluency intervention, use timed repeated reading. This is when a student reads for one minute and tries to beat their rate and accuracy with successive one-minute readings of the same text. But don’t use this with everyone. According to the authors of the Core Reading Sourcebook, timed repeated reading is best used “as an intervention strategy that is most appropriate for slow but accurate readers who need intense practice to increase their automaticity in reading connected text.”

Provide fluency drills at centers to give students practice naming letters and letter sounds. More advanced readers should practice reading syllables and single words. If you’re a member of my online course, Teaching Every Reader, you can head to this lesson to grab a big file of fluency drills.

Have students play word reading games in pairs or small groups. (My collection of editable reading games is perfect for this.)

Spend a week doing partner plays or reader’s theater (zip to the end of this post to download a free script in three levels!).

Give students daily time to read text at their independent or instructional level. Phonics lessons are great, but students must practice what they’re learning by reading connected text. I recommend making sure that each student has a bag of decodable texts that s/he can read every day. For students who are ready for leveled books, those should be in the bag as well. Note that I did not say that kids should grab any old book off the shelf and read for fluency practice. Work with your students to choose their books, and hold them accountable. Listen to them read whenever possible.Let’s sum up!DO understand the role of fluency in the big picture of learning to read. Fluency is the bridge to comprehension.DO assess oral reading fluency at different points of the year for first grade and up.DON’T focus only on reading rate. Fluency includes accuracy, rate, expression, and automaticity.DO provide authentic experiences for students to practice reading with expression. Partner plays are my favorite tool for this! Scroll down to get a FREE script.DON’T forget to make time for daily fluency building.

Free partner play in 3 levels

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The post Do’s and dont’s for teaching reading fluency appeared first on The Measured Mom.

August 23, 2021

Do’s and don’ts for phonics instruction

In today’s post, the second in our 5-part series, we’ll dive into do’s and don’ts for teaching phonics.

Another name for this post could be “Mistakes I’ve Made When Teaching Phonics …” because I’ve made a lot.

Let’s start with a little backstory.

When I first started teaching first grade, I had to use a very rigid phonics program that I detested.

I was a balanced literacy teacher all the way, and I didn’t think that such a structured approach was necessary. (Also, to be fair, the program was very, very boring and took an insane amount of time.)

The following year, I chose (with the principal and school board’s blessing) to take a different approach to phonics instruction. I taught phonics on as “as you need it” basis and taught my students to read using leveled texts and the three cueing system.

When students were stuck on a word, I did as I’d been taught in graduate school and tried really hard not to say, “sound it out.” Instead, I told my students to use clues from the picture or sentence to help them “solve” (note that I didn’t say read) the challenging word. I asked them to connect what they saw in the picture with the first letter of the mystery word.

I wasn’t anti-phonics by any means; I felt I was teaching as much of it as my students needed. But I put a greater emphasis on three-cueing; I thought that using three cueing was teaching them to problem solve.

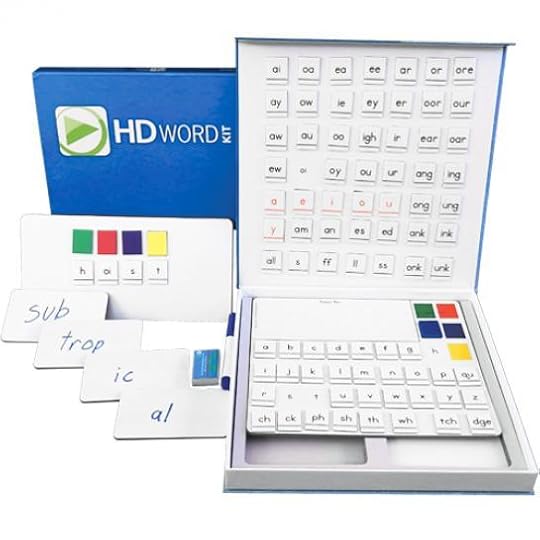

Now, after studying the science of reading, I understand that students need to learn phonics in a structured way so they can become proficient at orthographic mapping and, thus, learn to read words by sight.

Learning to read words by sight is not about memorizing lists of “sight words”; rather, it’s about connecting phonemes to graphemes (sounds to letters) until it becomes automatic.

Orthographic mapping involves the formation of letter-sound connections to bond the spellings, pronunciations, and meanings of specific words in memory. It explains how children learn to read words by sight, to spell words from memory, and to acquire vocabulary words from print.

Linnea Ehri

Now that you know a bit of my history, let’s dive into the do’s and don’ts for phonics instruction.

As a first and second grade teacher, I had a general idea about the order in which to teach phonics skills, but I didn’t think it was all that important.

I never had a printed scope and sequence that I could refer to.

Now I understand that a solid scope and sequence is KEY.

According to Wiley Blevins, in his fabulous book A Fresh Look at Phonics, a superior scope and sequence will:

Build from the simplest to the most complex skillsAllow many words to be formed as early as possibleTeach high-utility skills before less useful sound spellingsSeparate easily confused sounds and lettersA solid scope and sequence is a road map, and it’s essential for anyone looking to teach phonics in a structured, systematic way.

If you’re looking for the perfect scope and sequence, I’m sorry – there isn’t one. But following the above guidelines will help.

As I take into account my experience, study, and Orton-Gillingham training, I now recommend the following sequence for phonics instruction:

Consonants, short vowels, and basic digraphs (ch, sh, th, wh) … with CVC wordsBeginning and ending blendsCVCE wordsLong vowel teamsR-controlled vowelsDiphthongs and complex vowelsLess common sound spellingsOf course, there’s a lot more that needs to go into that sequence, such as syllable types and spelling rules.

You can grab my full scope and sequence for phonics instruction for FREE at the end of this post.

I fought decodable texts for a long time. That’s probably because the ones I had to use were just awful. They were stilted and nonsensical. I just couldn’t stomach them.

Instead, I used leveled texts. I thought that students were building fluency because they could “read” these books quickly, but they weren’t truly reading. They were using context and perhaps the first letter or two to guess the words. Occasionally they were sounding out words in their leveled readers. And as their haphazard phonics knowledge grew, some students naturally used phonics more and more. Eventually, they were truly reading.

But not all of them.

Some of them were still guessing. And I didn’t realize that because I didn’t see them when they graduated from my room into third grade. I didn’t see them struggling through harder texts – texts with fewer pictures and longer words – when three-cueing no longer served them.

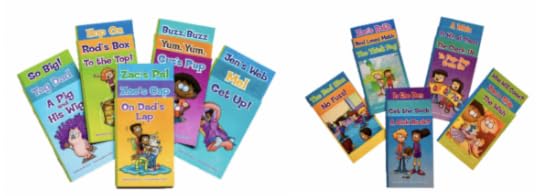

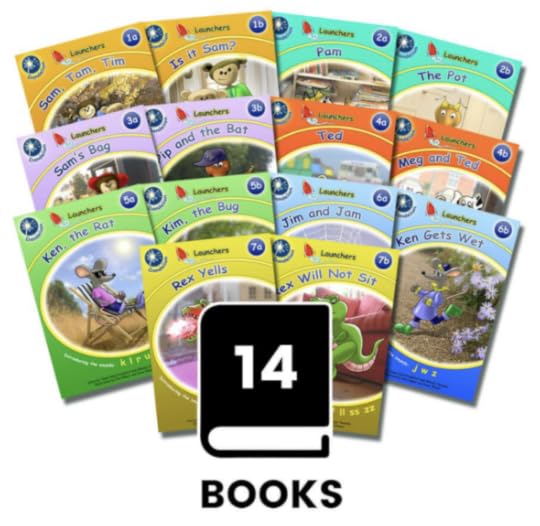

Students must practice what they’re learning in their phonics lessons by reading connected text. This text may be decodable passages or decodable sentences, but I think using actual decodable books is a good goal.

Here’s why:

It’s exciting to read an actual book. It’s fun.Books tell stories (or at least they should). Stories are fun.Books have pictures (or at least they should). Pictures are fun.No, learning to read isn’t all about fun.

But I feel I need to add the “fun” bit because sometimes it gets lost in the structured literacy approach. I get discouraged when I hear people say that early reading material shouldn’t have any pictures.

As long as our phonics material is structurally sound, there’s nothing wrong with making it appealing. Learning to read is hard work, but stories and pictures add joy.

As for where to find these quality decodable books, you’re in luck.

I spent six months purchasing and studying decodable texts. You can find my top recommendations in this post.

This morning I remembered how important routines are.

That’s because today was the first day all six of my kids went to school – from my oldest in high school all the way down to my baby, on his first day of kindergarten.

In order to get all the kids out the door at 7 AM, pick up two neighbor girls, and get to both schools on time, a routine was absolutely essential.

And we were out the door with five minutes to spare!

As a mom, I’ve learned how important routines are.

For some reason, though, I fought routines as a classroom teacher. I felt that routines made things boring.

As a parent I see that routines give kids security. They know what to expect. They get better and better at doing the things because they’ve done them so many times.

A routine helps you do the easy stuff automatically; it frees up your brain for the challenging work.

All that said, here’s a good routine for your phonics lessons.

These phonics lessons don’t have to be for the whole class.

I find it interesting (and frankly, disheartening) that some structured literacy teachers are adamantly against small group lessons. They maintain that the best (and only) way to teach phonics is through a whole class approach.

This way everyone gets access to grade level material.

But how does a 30-minute phonics lesson on “grade level” material help the student who is miles behind? And what does it do for the advanced readers who knew this content last year?

This is where small group teaching comes in, and it brings us to our first DON’T.

I know that one reason I had such a negative feeling about structured phonics lessons was because the whole class lessons I taught that one year served very few of my students.

It was a class of about 20 first graders, and several of them entered the room reading fourth grade chapter books.

I also had a student who had spent two years in kindergarten and still struggled to remember letter sounds.

The rest of the kids were spread across the middle.

A single phonics lesson was supposed to meet ALL of their needs?

I wish I had thought of giving a phonics assessment and then grouping my students by phonics skill.

Instead, I grouped by “reading level” and had my students read leveled books.

When some students got stuck at a lower level, I didn’t realize it was probably because they needed more explicit phonics instruction … not more practice with three-cueing.

In an ideal world, you’d have other teachers in your building who would work with you so that each of you could teach a small group phonics lesson at the same time. Students would visit a different classroom if needed, and each would get instruction tailored to his/her needs. In just 20-30 minutes, every student would be done with his/her phonics lesson.

In an ideal world.

I have never lived in that world, and you may not, either.

Here’s my recommendation:

Give a phonics assessment (if you’re a member of my course, Teaching Every Reader, you can use the one in this lesson ).Group your students by what they’re ready to learn next. Have no more than 4 groups, even if it means (and it probably will) that some students will need to start by practicing things they already know.Train your students to do meaningful literacy activities while you’re meeting with small groups. Yes, this will take some time. Yes, it will be worth it. If possible, meet with all of your phonics groups each day. If it’s not possible, make sure you meet with your lowest groups daily. Within your groups, follow the structure of an effective phonics lesson, as noted in the above infographic. Your lower groups will likely need longer lessons than your highest group.

A common criticism of structured literacy/the science of reading is that it’s all about phonics.

I feels like that.

It feels like that because other approaches often lack an appropriate focus on phonics, so the structured approach may feel like it’s going a little overboard to correct it.

The fact is, phonics instruction is HUGE for beginning readers. Decoding is the bulk of their reading work.

As they become more proficient at decoding, they will become more fluent, and they will be able to devote more attention to reading comprehension.

But they need to become proficient with phonic decoding first.

AND YET …

Beginning readers can (and should) build background knowledge.

They can (and should) build vocabulary.

They can (and should) think critically.

They can (and should) learn about language structures, genres, and more.

If you’re a student of the science of reading, you’re likely familiar with Scarborough’s reading rope, which you can see here.

Dr. Hollis Scarborough published it in 2001 as a visual to illustrate the complexities of learning to read.

As you notice, there are two strands. The top strand involves language comprehension.

The bottom strand is where phonics comes in.

What we need to remember is that those early decodable books aren’t going to do a whole lot to improve language comprehension.

The bulk of that work comes through interactive read-alouds.

I recommend doing one or two interactive read-alouds every day. You can learn more about them in this blog post.

Let’s sum up!This was a hefty blog post about teaching phonics! Let’s review.

DO follow a strong scope and sequence when teaching phonics. As a reminder, you can get my scope and sequence for FREE at the end of this post.

DO use decodable texts. It’s true; many decodable books have given them a bad name. But they’re not all boring and stilted; in fact, better books and series are being published all the time. Check out my ultimate guide to decodable books to find the best of the best.

DO follow a consistent routine in your phonics lessons. When kids have a routine for the easy stuff (knowing what comes next, getting out their letter tiles, etc.) they free up their brains for the more challenging work. A routine also keeps the teacher on task and makes planning easier!

DON’T limit your phonics instruction to whole class teaching. If all of your students have the same level of phonics knowledge, go ahead and stick to whole class teaching. But I’m willing to bet that they’re all over the map. Focused small group lessons will accelerate student growth.

DON’T forget the rest of the Reading Rope. Phonic decoding is extremely important for beginning readers, but we can address other strands through interactive read alouds.

Free phonics scope and sequence

Free Phonics Scope & Sequence

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The post Do’s and don’ts for phonics instruction appeared first on The Measured Mom.

August 19, 2021

Do’s and don’ts for teaching phonemic awareness

Looking for tips for teaching phonemic awareness?

In this post I’ll share do’s and don’ts for teaching phonemic awareness … sharing mistakes I’ve made in the past and new insights I’ve gained through my study of the science of reading.

As we consider do’s and don’ts for teaching phonemic awareness skills, let’s start with the basics.

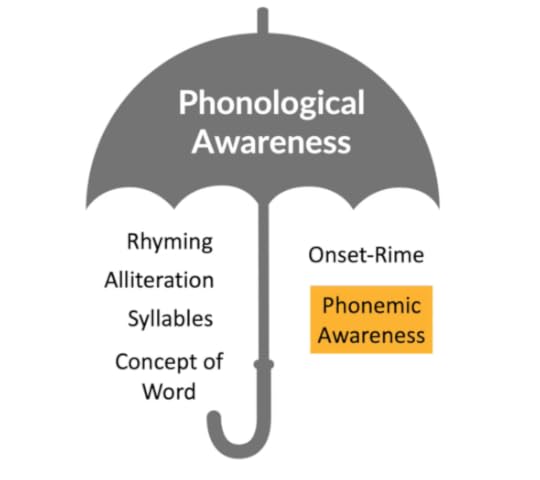

I admit it … I didn’t understand the difference between phonological and phonemic awareness for a long time.

I knew they weren’t the same as phonics. I knew that phonics has to do with print, and phonological/phonemic awareness has to do with sounds.

But the rest was fuzzy.

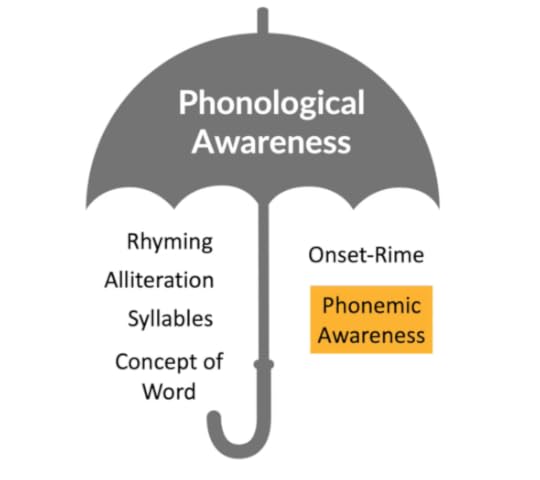

A visual helps.

The above graphic is from my online course, Teaching Every Reader. As you can see, there are many components of phonological awareness: rhyming, alliteration, syllables, concept of word, onset- rime, AND phonemic awareness.

Phonemic awareness is just one piece of phonological awareness.

Many researchers would argue that it’s the most important piece.

There are several mental skills associated with word reading. Phoneme awareness appears to be one of the most important of these skills. Phoneme awareness refers to the ability to notice that spoken words can be broken down into smaller parts called phonemes.

David Kilpatrick, Equipped for Reading Success

Did you catch that?

While the other components of phonological awareness have to do with the larger parts of words (syllables, onset/rime, etc.), a phoneme is the smallest part of a word. It’s an individual sound.

Test yourself.

How many phonemes does each of these words have?

hatfishswimboxsquishReady for the answer key? Note … when you see letters between those slash marks (fancy word = virgules), we are referring to the sounds, not the letter names.

Hat has three phonemes: /h/ /a/ /t/Fish has three phonemes: /f/ /i/ /sh/Swim has four phonemes: /s/ /w/ /i/ /m/Fox has four phonemes: /b/ /o/ /k/ /s/Squish has five phonemes: /s/ /k/ /w/ /i/ /sh/How’d you do?

If you’re new to counting phonemes, don’t worry! It takes a little practice.

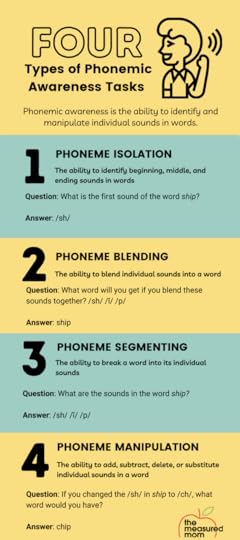

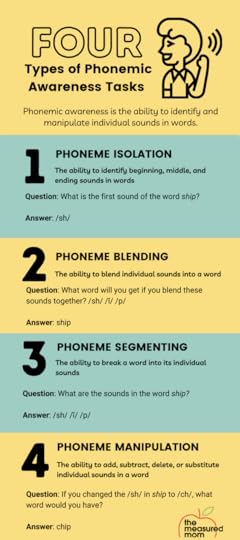

Before we move on, let’s remember that there are four levels of phonemic awareness.The following infographic breaks down the four types and gives a sample phonemic awareness task for each one.

If you’re asking, “Who cares?” then I say “Great question.”

Knowing what phonemic awareness is does us no good if we don’t understand why it matters.

That brings us to our second “do …”

Let’s start with the end goal: reading comprehension.

How do we get there?

Check out this quote from David Kilpatrick.

Reading comprehension is our goal, and the most direct route to good reading comprehension is to make the word recognition process automatic so a student can focus all of his or her mental energy on the meaning.

David Kilpatrick, Equipped for Reading Success

The next logical question is: HOW do we make the word recognition process automatic? How do we get students to the place where they recognize words immediately without needing to sound them out?

Hint: It’s not through memorizing long lists of words!

We use a process called orthographic mapping to be able to instantly recognize words.

Orthographic mapping is a process by which we map phonemes to graphemes.

Say what?!

This threw me for a loop for while, but it’s not as complex as it sounds.

Phonemes = sounds

Graphemes = printed letters which represent sounds

Therefore, orthographic mapping is a mental process by which we match the sounds of a word to the letters in a word (the spellings). By second grade, typical readers need just 2-4 exposures to a word to have it “orthographically mapped.”

We cannot become good at orthographic mapping unless we have both letter sound knowledge AND PHONEMIC AWARENESS.

(That was a very quick look at orthographic mapping, and if you don’t quite get it yet, that’s normal. Here’s an 11-minute video from Ms. Jane’s Tutoring & Dyslexia Services that explains it in an easy-to-understand way.

Once we understand WHAT phonemic awareness is, and WHY we need to teach it, we’re ready to get started.

But before you start, make sure you know how to pronounce phonemes properly.

What’s the sound of the letter l?

Did you say “luh”? Many people make that mistake.

Instead, we say that the sound of letter l is /llllll/.

Otherwise, if students are sounding out the word let, they might read it as luh-et.

Pronouncing phonemes getseven trickier with letters like p and b. It’s hard to clip the sounds quickly so we don’t add an “uh” to the end.

Check out this quick video to make sure you’re pronouncing all 44 phonemes correctly (the sounds will be different, of course, if you are not speaking American English.)

I have to hang my head in shame here because, for years, I didn’t give a lot of thought to phonemic awareness.

By “years” I mean all the years I was a classroom teacher. UGH.

I thought that the playful games we played with words and songs would be enough.

And it was … for some students.

I didn’t get that phonemic awareness is often the missing key for struggling readers. (And truthfully, all my students would have benefited from explicit instruction in phonemic awareness.)

Had I known its importance, I would have made it a point to teach phonemic awareness every day. (Every kindergarten and first grade teaches should fit it into their daily schedule.)

The good news is that phonemic awareness instruction doesn’t have to take long, and it requires few materials.

Many teachers love the Heggerty phonemic awareness curriculum. The program includes hand motions and daily lessons that take just 10-15 minutes.

I think Heggerty is a pretty solid program, but if your budget is tight, you can get a free printable phonemic awareness program at Reading Done Right.

Not ready to purchase a full curriculum? My phonemic awareness bundle has 12 weeks of oral phonemic awareness activities, plus printable games kids love.

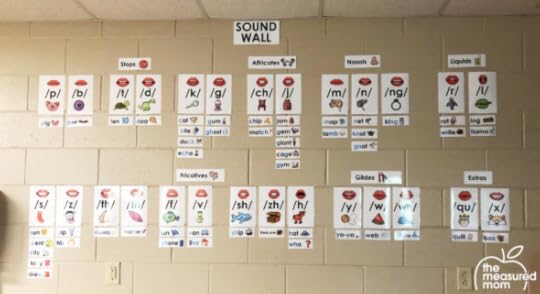

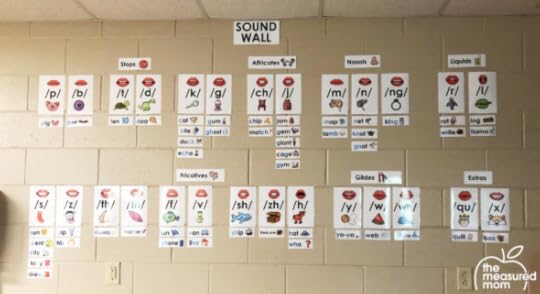

Are you familiar with sound walls? They’re all the rage these days – a substitute for the more traditional word walls.

In the past, we used word walls as a way to help kids find spellings of high frequency words.

But the problem with a word wall is that while we have 44 phonemes in the English language, a word wall only has 26 letters.

It makes more sense to teach children sounds (phonemes) and then gradually add words to the sound wall as they learn phonics patterns that spell those sounds.

Here’s a sound wall that I helped a teacher put up this very morning. (This is my own creation and will be added to my shop in the next few months.)

I won’t get into all the specifics here, but you can see that the sounds are arranged based on how they’re made in the mouth.

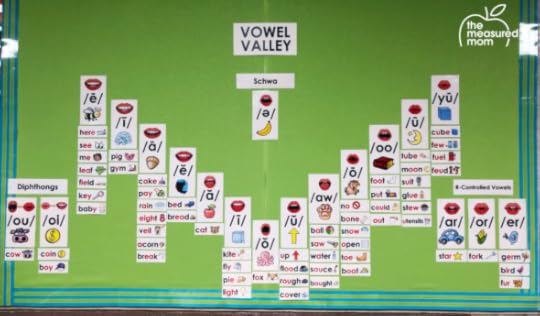

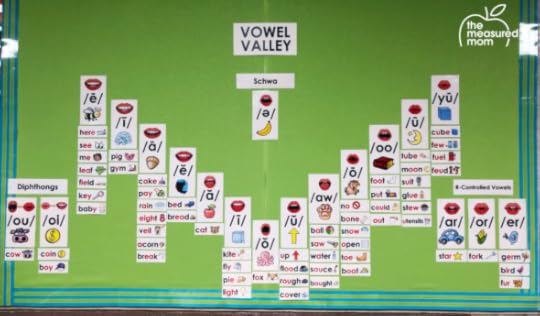

We also put up this sound wall for vowel phonemes. You can see that the vowels are arranged based on how your mouth is formed when you make the sounds. The bottom-most sound is the short o, when your mouth is opened the widest.

Many teachers have little mirrors that they give their students so they can see how their mouth looks when they articulate particular phonemes.

Here’s a very important sound wall tip …

Do not put up all the sounds and word cards on the first day!

The above examples are complete sound walls that you might not even see until third grade.

You should only display the words below each sound when you’ve taught that phonics pattern.

For example, the above sound wall includes “ei” for veil. You would likely not teach that pattern in first grade, so a first grade teacher would never use that card.

(If the idea of sound walls is fuzzy, stay tuned, because my upcoming product will explain exactly how to use it!)

We often hear that phonemic awareness activities can be done in the dark (without print), and that’s true, but it’s also important to teach phonemic awareness and phonics together.

One of my favorite ways to do that is with phoneme grapheme mapping. Check out this video I did with my preschool-aged son and our neighbor. (They are little; please excuse the incorrect letter formation.  )

)

In this activity they practiced:

Phoneme segmentingPhoneme blendingWe could have added phoneme isolation by asking, “What’s the first/middle/last sound?”

We could have added phoneme manipulation by asking, “If you took the /s/ off of sun and replaced it with /f/, what would the new word be?”

Another way to integrate phonemic awareness with phonics is to have a phonemic awareness warm-up related to the phonics skill you’re about to teach.

For example: If you’re teaching the ai spelling pattern, tell your students to listen for the vowel sound in each word. They should give a thumbs up if they hear the long a sound.

bat (thumbs down)

rain (thumbs up)

say (thumbs up)

snack (thumbs down)

weigh (thumbs up)

Then continue on to your phonics lesson in which you tell them that ai is one way to represent the long a sound.

Let’s sum up!This was a hefty blog post about teaching phonemic awareness! Let’s review.

DO understand the difference between phonological and phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness has to do with the individual sounds in words. There are four kids of phonemic awareness tasks:

phoneme isolationphoneme blendingphoneme segmentingphoneme manipulationDO understand the importance of phonemic awareness. The short explanation is that students must be proficient in phonemic awareness to be able to do the mental process of orthographic mapping – which is how we recognize words automatically instead of having to sound them out.

DON’T leave phonemic awareness to chance. Kindergarten and first grade teachers should reserve 5-10 minutes for phonemic awareness instruction every day.

DO use a sound wall as you teach each phoneme. Remember not to add a word card until you’ve taught the phonics pattern associated with that word.

Finally, DO integrate phonemic awareness with phonics instruction. You can do that with activities like phoneme grapheme mapping or by doing a related phonemic awareness task before you teach a new phonics skill.

As a reward for making it to the end of this post, you’re invited to download this FREE set of phonemic awareness games, a sample from my full set.

Free phonemic awareness games

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The rest of this series is coming this Fall!

Part 1 Part 2 – Coming August 30 Part 3 – Coming September 6 Part 4 – Coming September 13 Part 5 – Coming September 20

The post Do’s and don’ts for teaching phonemic awareness appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Do’s and dont’s for teaching phonemic awareness

Looking for tips for teaching phonemic awareness?

In this post I’ll share do’s and don’ts for teaching phonemic awareness … sharing mistakes I’ve made in the past and new insights I’ve gained through my study of the science of reading.

As we consider do’s and don’ts for teaching phonemic awareness skills, let’s start with the basics.

I admit it … I didn’t understand the difference between phonological and phonemic awareness for a long time.

I knew they weren’t the same as phonics. I knew that phonics has to do with print, and phonological/phonemic awareness has to do with sounds.

But the rest was fuzzy.

A visual helps.

The above graphic is from my online course, Teaching Every Reader. As you can see, there are many components of phonological awareness: rhyming, alliteration, syllables, concept of word, onset- rime, AND phonemic awareness.

Phonemic awareness is just one piece of phonological awareness.

Many researchers would argue that it’s the most important piece.

There are several mental skills associated with word reading. Phoneme awareness appears to be one of the most important of these skills. Phoneme awareness refers to the ability to notice that spoken words can be broken down into smaller parts called phonemes.

David Kilpatrick, Equipped for Reading Success

Did you catch that?

While the other components of phonological awareness have to do with the larger parts of words (syllables, onset/rime, etc.), a phoneme is the smallest part of a word. It’s an individual sound.

Test yourself.

How many phonemes does each of these words have?

hatfishswimboxsquishReady for the answer key? Note … when you see letters between those slash marks (fancy word = virgules), we are referring to the sounds, not the letter names.

Hat has three phonemes: /h/ /a/ /t/Fish has three phonemes: /f/ /i/ /sh/Swim has four phonemes: /s/ /w/ /i/ /m/Fox has four phonemes: /b/ /o/ /k/ /s/Squish has five phonemes: /s/ /k/ /w/ /i/ /sh/How’d you do?

If you’re new to counting phonemes, don’t worry! It takes a little practice.

Before we move on, let’s remember that there are four levels of phonemic awareness.The following infographic breaks down the four types and gives a sample phonemic awareness task for each one.

If you’re asking, “Who cares?” then I say “Great question.”

Knowing what phonemic awareness is does us no good if we don’t understand why it matters.

That brings us to our second “do …”

Let’s start with the end goal: reading comprehension.

How do we get there?

Check out this quote from David Kilpatrick.

Reading comprehension is our goal, and the most direct route to good reading comprehension is to make the word recognition process automatic so a student can focus all of his or her mental energy on the meaning.

David Kilpatrick, Equipped for Reading Success

The next logical question is: HOW do we make the word recognition process automatic? How do we get students to the place where they recognize words immediately without needing to sound them out?

Hint: It’s not through memorizing long lists of words!

We use a process called orthographic mapping to be able to instantly recognize words.

Orthographic mapping is a process by which we map phonemes to graphemes.

Say what?!

This threw me for a loop for while, but it’s not as complex as it sounds.

Phonemes = sounds

Graphemes = printed letters which represent sounds

Therefore, orthographic mapping is a mental process by which we match the sounds of a word to the letters in a word (the spellings). By second grade, typical readers need just 2-4 exposures to a word to have it “orthographically mapped.”

We cannot become good at orthographic mapping unless we have both letter sound knowledge AND PHONEMIC AWARENESS.

(That was a very quick look at orthographic mapping, and if you don’t quite get it yet, that’s normal. Here’s an 11-minute video from Ms. Jane’s Tutoring & Dyslexia Services that explains it in an easy-to-understand way.

Once we understand WHAT phonemic awareness is, and WHY we need to teach it, we’re ready to get started.

But before you start, make sure you know how to pronounce phonemes properly.

What’s the sound of the letter l?

Did you say “luh”? Many people make that mistake.

Instead, we say that the sound of letter l is /llllll/.

Otherwise, if students are sounding out the word let, they might read it as luh-et.

Pronouncing phonemes getseven trickier with letters like p and b. It’s hard to clip the sounds quickly so we don’t add an “uh” to the end.

Check out this quick video to make sure you’re pronouncing all 44 phonemes correctly (the sounds will be different, of course, if you are not speaking American English.)

I have to hang my head in shame here because, for years, I didn’t give a lot of thought to phonemic awareness.

By “years” I mean all the years I was a classroom teacher. UGH.

I thought that the playful games we played with words and songs would be enough.

And it was … for some students.

I didn’t get that phonemic awareness is often the missing key for struggling readers. (And truthfully, all my students would have benefited from explicit instruction in phonemic awareness.)

Had I known its importance, I would have made it a point to teach phonemic awareness every day. (Every kindergarten and first grade teaches should fit it into their daily schedule.)

The good news is that phonemic awareness instruction doesn’t have to take long, and it requires few materials.

Many teachers love the Heggerty phonemic awareness curriculum. The program includes hand motions and daily lessons that take just 10-15 minutes.

I think Heggerty is a pretty solid program, but if your budget is tight, you can get a free printable phonemic awareness program at Reading Done Right.

Not ready to purchase a full curriculum? My phonemic awareness bundle has 12 weeks of oral phonemic awareness activities, plus printable games kids love.

Are you familiar with sound walls? They’re all the rage these days – a substitute for the more traditional word walls.

In the past, we used word walls as a way to help kids find spellings of high frequency words.

But the problem with a word wall is that while we have 44 phonemes in the English language, a word wall only has 26 letters.

It makes more sense to teach children sounds (phonemes) and then gradually add words to the sound wall as they learn phonics patterns that spell those sounds.

Here’s a sound wall that I helped a teacher put up this very morning. (This is my own creation and will be added to my shop in the next few months.)

I won’t get into all the specifics here, but you can see that the sounds are arranged based on how they’re made in the mouth.

We falso put up this sound wall for vowel phonemes. You can see that the vowels are arranged based on how your mouth is formed when you make the sounds. The bottom-most sound is the short o, when your mouth is opened the widest.

Many teachers have little mirrors that they give their students so they can see how their mouth looks when they articulate particular phonemes.

Here’s a very important sound wall tip …

Do not put up all the sounds and word cards on the first day!

The above examples are complete sound walls that you might not even see until third grade.

You should only display the words below each sound when you’ve taught that phonics pattern.

For example, the above sound wall includes “ei” for veil. You would likely not teach that pattern in first grade, so a first grade teacher would never use that card.

(If the idea of sound walls is fuzzy, stay tuned, because my upcoming product will explain exactly how to use it!)

We often hear that phonemic awareness activities can be done in the dark (without print), and that’s true, but it’s also important to teach phonemic awareness and phonics together.

One of my favorite ways to do that is with phoneme grapheme mapping. Check out this video I did with my preschool-aged son and our neighbor. (They are little; please excuse the incorrect letter formation.  )

)

In this activity they practiced:

Phoneme segmentingPhoneme blendingWe could have added phoneme isolation by asking, “What’s the first/middle/last sound?”

We could have added phoneme manipulation by asking, “If you took the /s/ off of sun and replaced it with /f/, what would the new word be?”

Another way to integrate phonemic awareness with phonics is to have a phonemic awareness warm-up related to the phonics skill you’re about to teach.

For example: If you’re teaching the ai spelling pattern, tell your students to listen for the vowel sound in each word. They should give a thumbs up if they hear the long a sound.

bat (thumbs down)

rain (thumbs up)

say (thumbs up)

snack (thumbs down)

weigh (thumbs up)

Then continue on to your phonics lesson in which you tell them that ai is one way to represent the long a sound.

Let’s sum up!This was a hefty blog post about teaching phonemic awareness! Let’s review.

DO understand the difference between phonological and phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness has to do with the individual sounds in words. There are four kids of phonemic awareness tasks:

phoneme isolationphoneme blendingphoneme segmentingphoneme manipulationDO understand the importance of phonemic awareness. The short explanation is that students must be proficient in phonemic awareness to be able to do the mental process of orthographic mapping – which is how we recognize words automatically instead of having to sound them out.

DON’T leave phonemic awareness to chance. Kindergarten and first grade teachers should reserve 5-10 minutes for phonemic awareness instruction every day.

DO use a sound wall as you teach each phoneme. Remember not to add a word card until you’ve taught the phonics pattern associated with that word.

Finally, DO integrate phonemic awareness with phonics instruction. You can do that with activities like phoneme grapheme mapping or by doing a related phonemic awareness task before you teach a new phonics skill.

As a reward for making it to the end of this post, you’re invited to download this FREE set of phonemic awareness games, a sample from my full set.

Free phonemic awareness games

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The rest of this series is coming this Fall!

Part 1 Part 2 – Coming August 30 Part 3 – Coming September 6 Part 4 – Coming September 13 Part 5 – Coming September 20

The post Do’s and dont’s for teaching phonemic awareness appeared first on The Measured Mom.

May 2, 2021

Books to read on your science of reading journey

This concludes our official science of reading series, but there’s a lot more to learn! Check out my top recommendations for books that will help you understand the science AND apply it to your classroom. Also check out our online course, Teaching Every Reader!��It’s open for enrollment through May 10, 2021.��Get the details here.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello friends. Before we get into this episode, I wanted to add two books I forgot to mention - really essential books for your science of reading journey. One is "Equipped for Reading Success" by David Kilpatrick. He's all about explaining orthographic mapping and helping you understand how to build phonemic awareness with your students. And also Denise Eide's book, "Uncovering the Logic of English," which will teach you about some spelling rules and generalizations you may not have known before, and will help you teach your students reading and writing.

If you're with me on Facebook, you are watching a live recording of the Triple R Teaching Podcast Episode 44: Books to Read on Your Science of Reading Journey. If you've been with me on the podcast for the last couple of months, you know that I've shared quite a lot of episodes all about understanding the science of reading and how to apply that knowledge into the teaching that you're doing in your classroom.

Today I want to take a look at some books that I recommend for those of you that want to learn more. I'm going to start with books that I feel are very simple and an easy way to get into it, then we'll progress to some more challenging books, and we'll finish with very practical books.

The first one I like, and the first one I actually got the whole way through, was "Know Better, Do Better" by David and Meredith Liben. I love this book because it's written in a story format. They talk about how they started a charter school - a public school in Harlem - with a whole language approach. They were really excited about it, they got all the right materials, great teachers, and they were all into it. They thought they were doing a great job... and then their students ranked the bottom of the area's test scores.

So they realized that what they thought was working wasn't working, the students weren't really learning to read very well. So they kept what was good about the whole language approach, but then they moved to a more structured literacy approach. This was way back in the nineties, I believe. And it worked! The students became great readers!

I like this book because it is not judgmental. It's written to people like me who come from a balanced literacy background, or for some of you maybe even whole language, and they tackle some of the things that might scare you a little bit and help you understand how it worked for them. So you might be scared of switching to decodable books, but they talk about their experience with it and how it actually was very positive. It's quite short and super interesting and helpful, so I would start with "Know Better, Do Better" by David Liben and Meredith Liben.

Another book is a new one that was just recently published, called "Shifting the Balance" by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates. I'm going to go ahead and read to you the summary on the back: "These days, it seems that everyone has a strong opinion about how to teach young children to read. Some may brush off the current tension as nothing more than one more round of ���The Reading Wars.��� Others may avoid the clash altogether due to the uncivilized discourse that sometimes results. Certainly, sorting the signal from the noise is no easy task. In this leading-edge book, authors Jan Burkins and Kari Yates address this tension as a critical opportunity to look closely at the research, re-evaluate current practices, and embrace new possibilities."

I like this book because, again, if you are in a balanced literacy classroom, this shows you how to start to understand the science of reading and make some changes. It's not judgmental, but is a good way to start integrating the science into more of what you're doing.

Those are the ones I recommend starting with. As you're ready to learn a little bit more, I recommend "Speech to Print" by Louisa Moats. This one helps you understand the structure of the English language, which can then help you teach it. I think you might be surprised at how much you didn't know, that's how I feel about it. I haven't completed this book yet, but I refer to it often. It's got a lot of helpful charts, talks about things like teaching syllable types, talks about phonemes and morphologies, and is really helpful.

Now anytime you ask someone, "What book should I read about the science of reading?" they'll usually recommend one of these books, if not all three. These are Mark Seidenberg's "Language at the Speed of Sight," "Proust and the Squid" by Maryanne Wolf, and "Reading in the Brain" by Stanislas Dehaene. I'm going to be honest with you, these books are hard. I have definitely not gotten through all of them, in fact, I've only read a portion of each one of these books.

I prefer Stanislas Dehaene's YouTube video. There's a presentation that he gave about how the brain learns to read, and I find that much easier to get through than this book. I watched it many times until it made sense to me. I will link to that in the show notes for this episode.

Here's this one, "Proust and the Squid" by Maryanne Wolf. She is a professor of child development, and she's excellent. You can find her doing a lot of interviews all over the place. I found this book hard to get through, but maybe eventually I'll be able to do it.

Of all three, I find Mark Seidenberg's book the most easy to read. He talks about understanding the science of reading and why it's important for our students. He's a cognitive neuroscientist. This book is long and the font is small, but a lot of it's told in, again, sort of a story fashion, so it's easier to get through.

Another book, which I can't wait to finish, is this one, "Overcoming Dyslexia." You might think at first glance, "I don't need to read that. I'm not interested in learning about teaching students with dyslexia because that's not what I do." Or you might think, "What I learn in there can't also apply to the rest of my class." But this is really good because she talks about the science of how the brain learns to read and how the way that we teach students can really help. You may actually read it and find out that some of your students possibly could have dyslexia based on the things that she writes, and that will help you think about how to change what you're doing in the classroom. It has lots of stories, and she has a very nice writing style, I highly recommend it.

Now let's talk about getting some practical books. These would be books that not only teach you about the science, but also give you things to do with it. I'll give you a few of my recommendations here.

I like "A Fresh Look at Phonics." This book is older, from 2017, so about four years old. I really like Wiley Blevins a lot. I like him because he is not the type of person that's going to tell you it has to be one way. He's honest about what the research really says and what people try to make it say. He also shows you how you can be a good phonics teacher, even within maybe a less than ideal setup. Maybe you're in a balanced literacy classroom and you have to be, so you can't quite transition to a structured literacy classroom. He'll still show you how to be a strong phonics teacher. This is extremely easy to read, and has lots of helpful resources. You might also want to check out his book, "Phonics A to Z," which I think is on its third edition.

Here's another book that is actually one of my favorites. I love that Rollanda E. O'Connor in her book, "Teaching Word Recognition," talks about the research. She's constantly backing up what she's saying with research, but it's also extremely practical and I found it very interesting. I read this book in the car while we were on vacation and I just marked it up all over the place. I read it from start to finish. She talks about things like oral language, phonemic awareness, the alphabetic principle, decoding, developing sight words, reading multi-syllabic words. It's just got everything. It's really, really good and is a short read, so you can get a lot out of it in a short time.

I'll share two more books. One is "How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction" by Sharon Walpole and Michael McKenna. This is the book you want if you're trying to figure out how to do needs-based small groups during your reading block; if you're interested in finding out specifically what skills each of your students has and then you're grouping them to help them move forward. This is not going to be teaching you how to group students by reading level, it's going to help you group them by their need. So maybe you could think of it as grouping them by their deficits, like where are they in terms of their phonics knowledge? Where do they need to go next? This book will help you get them there. I love it because, as any of you know, when you have a class of 25 kids they're going to be all over the place, right? They're not all going to be moving at the same pace your phonics curriculum does. And so this is really good for differentiation, and I think you'll love that over half the book is the activities so it's really, really practical. This is a very popular one. If you find it's expensive on Amazon, you should get it from the publisher's website, the Guilford Press.

Here's the last one. This one is on the pricey side, but wow is it an incredible book with lots of resources! I love that each chapter talks about the science and it gives you really practical ideas. This is called "Teaching Reading Sourcebook," from Core. It might be about $80, but look how fat it is, and it's very readable with big font, really nice charts, word lists, as well as specific activities to do with students. I highly recommended it. They also have an assessment spiral-bound book that you can buy, which is also very good.

So let's really quickly review the books we talked about today. The books that I started with, as in books that are going to slowly get you into the science of reading, particularly if you're coming from a balanced literacy background are: "Know Better, Do Better" by David and Meredith Liben and "Shifting the Balance" by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates.

Then if you want to go really deep and read some of those harder books, some of your choices are: Mark Seidenberg's "Language at the Speed of Sight," which is my favorite of these, "Proust and the Squid" by Maryanne Wolf, and "Reading in the Brain" by Stanislas Dehaene.

You also might want to check out "Overcoming Dyslexia" by Sally Shaywitz. This book is not just for teachers of students with dyslexia, it will help you understand how the brain learns to read and how you can apply that to how you teach all of your students.

Finally, I talked about some books that are really practical. Those were: "A Fresh Look at Phonics" by Wiley Blevins (I recommend anything by Wiley Blevins), as well as "Teaching Word Recognition," which talks a lot about the research, but also talks about specific activities. That's by Rollanda E. O'Connor. "How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction" by Sharon Walpole, which I think is a must-own. And then finally, from Core, "Teaching Reading Sourcebook," which is jam-packed with summaries of the research and specific activities that you can do.

I hope this was helpful. I've really enjoyed doing the science of reading series with you. This concludes our official science of reading podcast series, but we're not going to stop talking about these things next week. We're going to start a series about teaching phonics.

I should also let you know that if you're listening to this in real time, when I publish it on the podcast, it will be Monday, May 3rd, and that is the day that Becky Spence and I are opening the door to our online course, "Teaching Every Reader." We're very excited to open it up; we only open it up a couple of times a year. In fact, on Monday and Tuesday, we're going to be giving a live workshop that is going to teach you four simple ways to bring the science of reading into a K-2 classroom. In that workshop, we'll be giving specific details about the course and how, if you join by Thursday of next week, you can get special early bird pricing. So if you haven't signed up for one of the workshops, you can do that by heading to themeasuredmom.com/liveworkshop.

If you want to learn more about the course, you can go to teachingeveryreader.com. There's an information page there now, and it will switch over with an option to join us on Monday. I'm also always happy to answer questions; you can email my team at hello@themeasuredmom.com. Thanks so much for joining me, and I'll talk to you again next week.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related episodes What are the reading wars? My reaction to Emily Hanford���s article, ���At a Loss for Words��� How the brain learns to read What the science of reading is based on What���s wrong with three-cueing? Should you use leveled or decodable books with beginning readers? Do���s and don���ts for using decodable texts with beginning readers The difference between balanced and structured literacy 3 science of reading myths debunked Recommended books Equipped for Reading Success , by David Kilpatrick Uncovering the Logic of English , by Denise Eide Know Better, Do Better , by David & Meredith Liben Shifting the Balance , by Jan Burkins & Kari Yates Speech to Print , by Louisa Moats Reading in the Brain , by Stanislas Dehaene (check out the related YouTube video here) Proust and the Squid , by Maryanne Wolf Language at the Speed of Sight , by Mark Seidenberg Overcoming Dyslexia , by Sally Shaywitz A Fresh Look at Phonics , by Wiley Blevins Teaching Word Recognition , by Rollanda E. O’Connor How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction , by Sharon Walpole & Michael McKenna CORE’s Teaching Reading Sourcebook , by Bill Honig, et. al.Join our online course … open for a short time only! Register here!

The post Books to read on your science of reading journey appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 28, 2021

Syntax and semantics in structured literacy

Have you been following along in our series about structured literacy? Becky Spence (This Reading Mama) are doing this collaborative blog series as we revise our online course, Teaching Every Reader, to align with the science of reading.

In week 1, I named the elements of structured literacy. In week 2, we examined the key differences between balanced and structured literacy. I was honest about why it took me quite some time to make the shift from balanced to structured literacy.In week 3, Becky defined phonology and helped us see how we can teach phonological and phonemic awareness in a structured way.In week 4, I discussed the why, what when, and how of teaching sound-symbol association (i,e, phonics) within a structured literacy setting.In week 5, Becky broke down syllable instruction . I highly recommend her free chart for teaching about syllables in a systematic way – it’s super helpful and can be found right in the blog post. In week 6, Becky took the mystery out of morphology . She explained that it’s important because it helps learners read with meaning and spell words correctly.And now we’re on week 7! It’s the final week of our structured literacy series, and I’m going to tackle syntax and semantics.

I’ll be honest … these elements of structured literacy are not as easy to explain.

The definitions are rather straightforward, but it can be difficult to describe systematic and sequential way to teach these aspects of structured literacy.

But it’s crucial that we take the time to teach syntax and semantics; after all, structured literacy isn’t just about phonics!

What is syntax within structured literacy?

Syntax is the set of principles that dictate the sequence and function of words in a sentence in order to convey meaning. This includes grammar, sentence variation, and the mechanics of language.

The International Dyslexia Association on readingrockets.org

You likely have a grammar curriculum that you follow.

But syntax isn’t just about identifying whether a word is a noun, verb, adjective, or other part of speech.

Understanding sentence structure is what’s really key.

According to Joan Sedita of Keys to Literacy, “the ability to understand at the sentence level is in many ways the foundation for being able to comprehend text.”

Here are two of the activities that Sedita recommends for teaching sentence structure:

Sentence scramble: Write each word of a sentence on a card. Give the cards (out of order) to your students. They must arrange the words into a complete, grammatically correct sentence.Sentence elaboration: Start with a simple subject (The cat). Then ask the W questions as readers gradually add more information.EXAMPLE:

“Who?” the cat.

“What about the cat?” The cat ate.

“What did she eat?” The cat ate a cicada.

“Where did she eat it?” The cat ate a cicada in the front yard.

“Why did she eat it?” The cat ate a cicada in the front yard because she was hungry.

“When did she eat it?” This morning, the cat ate a cicada in the front yard because she was hungry.

I learned about another activity for building sentence structure from Deb Glaser of The Reading Teacher’s Top Ten Tools.

Sentence combining: After reading a fiction or nonfiction text to your students, share two related sentences. Discuss how the sentences relate to each other and choose a connector to combine the sentences.EXAMPLE: After reading aloud The Three Little Pigs, you could post these sentences:

The Third Little Pig was smart.

The Third Little Pig built a house of bricks.

Talk about how the sentences relate. Do they have contrasting ideas? Does the second sentence give more information? Does one sentence provide an explanation? Do the sentences show events in a sequence?