Anna Geiger's Blog, page 22

February 20, 2022

Mistakes to avoid when giving phonics instruction

For decades I considered myself a balanced literacy teacher. Of course I believed in phonics instruction.

Of course I taught phonics.

Or did I?

Looking back, I made some pretty big mistakes when it came to phonics instruction.

I’m sharing them here in the hopes that I can help you avoid my own mistakes!

Phonics Instruction Mistake #1: Not following a strong scope and sequence

Phonics Instruction Mistake #1: Not following a strong scope and sequenceAs a balanced literacy teacher, I had a general idea of which phonics skills were important to learn.

But I believed in an embedded approach to phonics instruction.

In other words, I taught phonics as it came up in our shared reading lessons, the students’ reading of leveled books, and our spelling lessons.

When students were stuck on a word, I (sometimes) encouraged them to find chunks they knew. If the word contained a sound-spelling they hadn’t yet encountered, I simply told it to them. (“ee” makes the long e sound)

Don’t get me wrong; it’s definitely helpful to point out sound-spellings during authentic reading and writing experiences.

BUT … this should be in addition to explicit phonics lessons that follow a strong scope and sequence.

By using a scope and sequence, we can ensure that we are not leaving gaps in our students’ phonics knowledge.

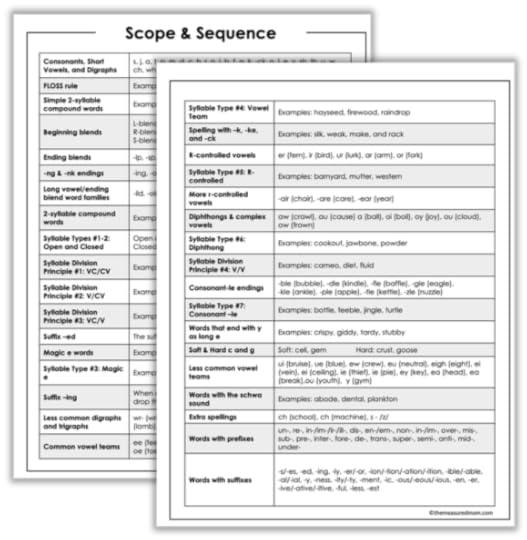

Get my free phonics scope and sequence below.

Free phonics scope and sequence

Sign up for our free newsletter and get this detailed phonics scope and sequence. You’ll know exactly what order to teach foundational phonics concepts!

Phonics Instruction Mistake #2: Not teaching phonics explicitly and systematically

I’ll be up front and tell you that my first year of teaching first grade, I was required to use a scripted phonics program that I hated.

It was a whole class program that, quite honestly, wasn’t meeting the needs of most of my students.

Because of that bad experience, I strongly believed in an embedded (rather than sequential, systematic) phonics approach. With the school board’s blessing, I tossed that program and, with it, explicit phonics teaching.

If I could go back (ahem) years, I would give engaging phonics lessons with the following elements:

Phonics Instruction Mistake #3: Forgetting to incorporate phonemic awareness

Phonics Instruction Mistake #3: Forgetting to incorporate phonemic awarenessI’ll be honest. Phonemic awareness was hardly on my radar when I was a classroom teacher.

But these days, phonemic awareness is a hot topic in reading education … and with good reason! Of all the phonological awareness skills, phonemic awareness is by far the most important.

A child’s level of phonemic awareness has direct impact on his/her reading success.

A reminder: phonemic awareness is the ability to play with individual sounds in words; specifically, isolating, blending, segmenting, and manipulating those sounds.

We used to think that we should only do phonemic awareness “in the dark,” but now we know that incorporating letters is important.

Check out this video in which I share examples of incorporating phonemic awareness with phonics. (This is lesson 8 in our membership training, Phonological and Phonemic Awareness.)

The above video is an excerpt from the Phonological & Phonemic Awareness training of our membership site, The Measured Mom Plus.

Phonics Instruction Mistake #4: Not giving students enough practice with new sound-spellingsAs a balanced literacy teacher, I taught phonics within our spelling lessons. But looking back, I know that my approach was not nearly as robust as my students needed.

Most importantly, they lacked sufficient practice with new sound-spellings.

In spelling class, I taught my students to read and sort words with specific phonics patterns. But then I had them read leveled books during reading class. Since they yet didn’t know many of the sound-spellings in their leveled books, I told them to use context and the picture to help them “solve” words.

I wish I knew then what I know now.

Here’s the thing.

For kids who struggle to sound out words, they’re going to take the path of least resistance. They’re not going to use phonics to solve words if they can help it.

I wish, wish, wish that I had used quality decodable books instead leveled books with my beginning readers.

Decodable books help students actually apply their phonics knowledge.

I know, I know. A lot of decodable books are really the pits. But there are some incredible decodable book series out there, and more are published all the time.

Check out my Ultimate Guide to Decodable Books to find new favorites!

Phonics Instruction Mistake #5: Not teaching strategies for sounding out multi-syllable wordsI’m embarrassed to say that the only thing I remember teaching my students about multi-syllable words was to find chunks they know.

There’s so much more we can and should do!

1-Consider teaching students to read and identify syllable types (open, closed, magic e, vowel team, r-controlled, and consonant-le). To learn more, check out Reading Rockets’ article: Six Syllable Types.

2- Consider teaching syllable division strategies. There is debate about this in the science of reading community; some believe this is just too complicated and a waste of time.

I think the opposing side has a valid argument, but I don’t think we should toss it out entirely. We should be careful not to spend too much time on this, but I believe that teaching syllable division principles is valuable. To learn more, check out Sarah’s Teaching Snippets blog post: How to Teach Syllable Division Rules.

3- If the above is too much for you, I understand. Syllable types and syllable division principles can feel overwhelming or just plain unnecessary If you’re in that camp, make sure you teach your students a non-rule based approach for sounding out multi-syllable words.

I LOVE this video from Reading Rockets. If you’re short on time, watch it on double speed. It’s worth the 7 minutes!

Phonics Instruction Mistake #6: Failing to differentiateI love the enthusiasm I’m seeing from teachers all over the world about making their phonics instruction more explicit and systematic.

But in doing this, we have to be careful not to fall back into the old trap of thinking that teaching the same thing to everyone – all the time – is the way to go.

If you’ve been a teacher for a single day, you know how vastly different our students’ abilities are, especially when it comes to early reading skills.

Personally, I think that our students in kindergarten and first grade are best served by small group phonics lessons. To form these groups, we assess students’ phonics knowledge (check out my free phonics assessment – coming soon!) and group them accordingly.

In these small groups, we teach phonics systematically, sequentially, and explicitly.

If you’d like to know more about what those small group lessons could look like, stay tuned! It’s coming later in our phonics series.

Ultimate Collection of Phonics Word Lists

$15.00

After spending way too many hours searching for the right words, I created this ultimate collection of phonics word lists. With over 200 word lists, you’ll never have to google “words with the CVCE pattern” ever again!

Buy Now

The post Mistakes to avoid when giving phonics instruction appeared first on The Measured Mom.

February 13, 2022

Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #10: Do Fountas and Pinnell REALLY want teachers to educate themselves?

TRT Podcast#66: Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #10 – Do Fountas and Pinnell REALLY want teachers to educate themselves?

Fountas and Pinnell claim that administrators need to prioritize ongoing professional learning for teachers. But what happens when these teachers find out that what they’re learning contradicts Fountas and Pinnell’s approach?

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and you are listening to Episode 66 of the Triple R Teaching podcast. Today is the tenth and final reaction episode in which I respond to Fountas and Pinnell.

Their final question that they responded to was this one, "Much has been said about the role of teachers in teaching children how to read, but what role do school administrators, coaches, and other teacher leaders play?"

This may be the longest response that Fountas & Pinnell shared in their series. I'm going to play just a short paragraph:

"There are various roles throughout the school that can support the growth of teacher expertise: principals who aim to build the capacity for shared leadership in their schools, literacy coaches who value the expertise of teachers and support their leadership development, and teachers who want to grow professionally and contribute to their team by engaging in acts of leadership to support all their colleagues."

So I don't think there's anything in the response that Fountas & Pinnell shared to disagree with. They acknowledge that school administrators and teachers need to work together, they need to educate themselves, they must all take responsibility for the success of all the students, and everyone must learn more every year.

I just find it very ironic that Fountas and Pinnell are promoting this culture of learning among the staff and the administration when that does not seem to be the approach they have personally taken.

They talk a good game about how their resources are research based, but when you really look at the science of reading you see that they are stuck. They are stuck because they believe that three-cueing is what students need to make sense of text.

We've talked many times about how that is not true. When we understand that three-cueing is a problem, then we can make the conclusion that students, at least early readers, should not be using leveled books to "read" because they can't solve the words except by using three-cueing.

So we make the conclusion that students should be learning to read using decodable books, at least in those very early stages, and we understand the foundational role that phonics has to play.

Fountas and Pinnell seem to be closing their eyes and ears to the current research. They talk about having everyone educate themselves and support each other, but I'm not sure they're living it out.

I've heard from many teachers who want very much to move forward in structured literacy and the science of reading, but they're in a Fountas and Pinnell school. They're in a school where they're required to do the Fountas and Pinnell brand of guided reading, and they're struggling because they see that these approaches are not working and should not be used when teaching beginning readers.

Now am I saying that everything that Fountas and Pinnell share is bad or wrong? No, I definitely do not say that nor do I believe that.

However, when you look at their foundational beliefs, which really are based on the idea of three-cueing, you have to question any conclusions that they draw. So a wise, educated teacher may be able to find some gems of wisdom from Fountas and Pinnell, but that's really not where I would choose to go, not after I've learned so much about the science of reading, and now that I see that they really aren't interested in that conversation.

If you're in a school where you would like to help your staff understand more about the science reading in a nonjudgmental way, I have a presentation that I am able to give online. It is called "Embracing the Science of Reading After Twenty Years in Balanced Literacy."

If you think that's a presentation that your staff would be open to, I would definitely invite your administrator as well, and we could possibly set up an hour where I could share this with your staff live. The challenge, of course, is always finding a time that works for everyone, so you may certainly reach out to me at hello@themeasuredmom.com.

If you have a morning that your staff has some development time, it's possible that we could work this out depending on our time zones. I can't do this when my kids are home, it just doesn't work. I have mornings available this year, and in the future I'll have more flexibility when all six kids are in school all day.

Feel free to reach out if we can set something up, we will. I'd love to help you help your staff understand the science of reading.

Thanks so much for listening to this ten part series, and I look forward to sharing more podcast episodes with you soon. You can check out the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode66.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Emily Hanford’s response: Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Mark Seidenberg’s response: Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

Check out the full podcast series:

Reaction #1: You CAN have conversations about the science of reading

Reaction #2: Fountas & Pinnell are wrong about three-cueing

Reaction #3: Yes, you ARE teaching guessing

Reaction #4: Here are the problems with guided reading

Reaction #5: Here’s why you SHOULD use decodable books

Reaction #6: You can teach phonics AND language comprehension

Reaction #7: Do Fountas & Pinnell promote balanced literacy?

Reaction #8: Is structured literacy responsive?

Reaction #9: Do teachers know best?

Reaction #10: Do Fountas & Pinnell REALLY want teachers to educate themselves?

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #10: Do Fountas and Pinnell REALLY want teachers to educate themselves? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Answers to common questions about decodable readers

What are decodable readers?

Who should be reading them?

When can students move on to a different type of text?

We’ll answer these questions and more in today’s post!

I’ve been upfront about this before, but I’ll say it again.

I wasn’t always a fan of decodable readers.

Decodable readers (also called decodable books) can be stilted, boring, and nonsensical.

The good news is that times are a-changin’.

These days it isn’t hard to find beautiful, interesting, and meaningful decodable texts … even for very young readers.

In today’s post we’ll answer common questions about this important tool.

What are decodable readers?I love this definition from Iowa Reading Research.

Decodable readers are texts that introduce words and word structures in a carefully planned scope and sequence. The order in which that word structure is introduced often aligns with the scope and sequence of the curriculum. In this way, students have the opportunity to apply the phonics skills they are learning and to build confidence in their abilities to read full sentences and short stories.

Iowa Reading Research

The fact is that a book is only decodable for a child if s/he has been taught the sound-spellings within the book. What is decodable for one child is not necessarily decodable for another.

You might be wondering if a book has to be 100% decodable to quality.

It does not.

In his book, Choosing and Using Decodable Texts (definitely one to add to your library!), Wiley Blevins shares this opinion: “If one story is more comprehensible and engaging at 65 percent or 70 percent decodable than another story at 80 percent decodable that has stilted sentences and odd language structures, I prefer the story with slightly lower decodability.”

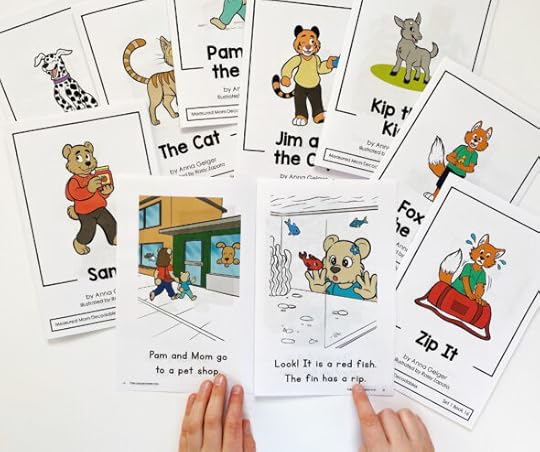

Here’s a sample book from my collection of decodable books (you can get a version of the book below for free on this page).

Of the 25 different words in the book (many are repeated, for a total of 64 words), 64% are decodable based on the sound-spellings that have been taught thus far.

We could easily stretch that number to 76% if we include the words has, is, and a. HAS and IS are decodable when you teach students that “s” can also represent /z/. And “a” is such an easy word I hesitate to call it irregular.

The remainder of the words are the following: for, go, to, look, the, her

Some of those are functional words that kids should learn early on: to and the.

Some are words with the r-controlled vowel pattern: for and her. It will be a while until these students are explicitly taught r-controlled vowels, but that doesn’t mean we should prevent them from seeing or learning any words with that pattern. The book also contains the word look, another word I think kids should learn before we teach the related phonics pattern.

That leaves us with the word GO. Soon, these students will learn open and closed syllables. But for now it’s fine for them to learn to recognize this word without that explicit instruction.

Why should we use decodable readers with our students?For years I resisted decodable books. Not only did I believe that all of them were boring without any kind of meaningful story line, I also thought that I had a much better alternative.

I used leveled books with my beginning readers. Early leveled books usually have predictable text and words that students can figure out using the picture and/or context.

I thought that I was teaching my students to be strategic readers by encouraging them to use all the “cues” available to them: meaning, syntax, and the visual cue of phonics. (You might know that this is called “three cueing,” or MSV.)

It wasn’t until I began exploring the science of reading that I realized that teaching kids to use three-cueing is counter-productive at best, and harmful at worst.

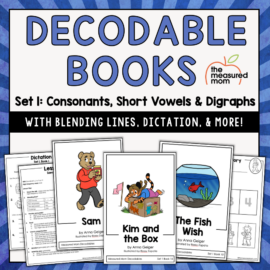

Decodable Books & Lessons for CVC Words & Common Digraphs

$18.00

This set of printable books includes blending lines, dictation practice, comprehension questions and more for each book!

Buy Now

It all comes down to how the brain learns to read.

Let’s review.

In the brain, there are different areas that work together to help us read. We need to get the phonological assembly region (that focuses on sounds) to connect with the orthographic processor (which focuses on print). How do we get these areas to work together?

We give kids explicit, systematic phonics instruction AND practice with decoding.

Where will they get that practice?

You guessed it. Reading and re-reading quality decodable texts and books.

When kids decode a word enough times, it becomes “orthographically mapped.” That means that they recognize it instantly without needing to sound out or guess. It’s not because they’ve memorized the word as a whole … it’s because they connected the letters to the sounds.

Some kids can orthographically map a word after reading it just a few times. Other kids need more exposures to the word.

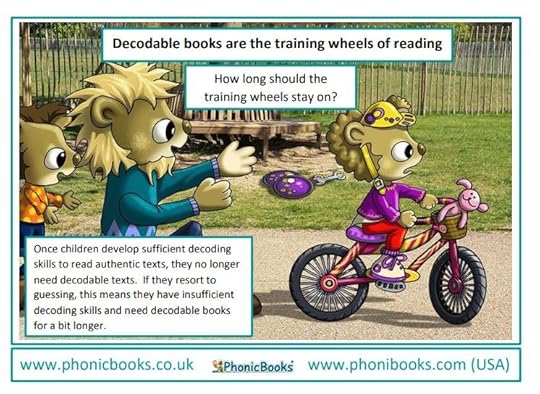

Who should be reading decodable books? And for how long?I can’t think of a better way to explain this than with this lovely graphic from Phonicbooks.

(Phonicbooks is one of many companies with quality decodable readers in multiple levels. The books are sturdy and engaging, and I definitely recommend checking out their website.)

As pointed out in the graphic, kids should start to read with decodable books.

Eventually, as they develop the skills to read authentic texts (books that were written for us to enjoy and not to teach a specific phonics pattern) they can move on to other texts for independent practice.

In an excellent webinar presentation that you can find on YouTube, Michel Hunter and Linda Farrell state that they feel that kids are ready to move out of decodable books when they are at about a level J. (While I am no longer a fan of Fountas and Pinnell, I do think that their leveling system can be useful when helping kids choose books for independent reading … particularly at level J and higher, when kids can’t use three-cueing to read all the words.)

However!

Even though we can eventually guide our students toward non-decodable books for their independent reading practice, decodable text is still very valuable in our small group phonics lessons.

Let’s chat about that next.

How to use decodable textsIn general, I recommend teaching phonics in small groups rather than to the whole class.

That’s because – if you are teaching anywhere at all – you know that students come to you with a huge variety of reading skills.

My first year of teaching first grade, I had a student who couldn’t remember the letters of the alphabet after two years in kindergarten, and two students who were reading at a fourth grade reading level.

Teaching phonics to the whole group (which I was expected to do) was a fail. My sweet little student who couldn’t remember letter sounds was quickly confused. And my advanced readers were thoroughly bored.

In my opinion, it’s better to assess kids with a good phonics assessment (coming soon!) and teach phonics in small groups.

A future post will break those lessons down for you, but for now let’s share some activities that you can do as you teach your students to read a particular decodable text.

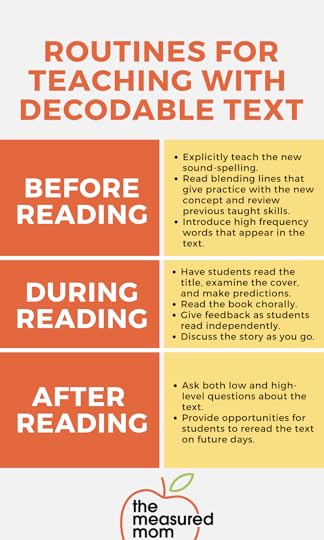

Take a screenshot of following infographic for future reference!

Where can you find quality decodable readers?

After all this talk about why, when, and how we should use decodable books (and with whom), one question remains …

Where can we find them?

For about six months, I collected as many decodable books that I could find. Then I reviewed the books and put them together in The Ultimate Guide to Decodable Books.

You can find it by clicking on the image below.

Looking for more information about decodable text? Here are some great resources!

The Drudgery (and Beauty) of Decodable Texts – by Margaret Goldberg of The Right to Read Project Fear Not the Decodable: Why? When? How? – by Heidi Ann Mesmer, PhD at Heinemann How to Use Decodable Books – by Santina DiMauro at Phonics Hero How to Use Decodable Texts – by Christina Winter of Mrs. Winter’s Bliss Decodable Books: What Are They, and How Should I Use Them with My K-2 Students? by Alison Ryan of Learning at the Primary PondBe sure to check out the rest of our phonics series!The post Answers to common questions about decodable readers appeared first on The Measured Mom.

February 12, 2022

Free decodable books

Are you looking for free decodable books to use with your learners in the classroom or at home?

You’re in the right spot!

My experience with decodable books

My experience with decodable booksI admit it. As a first grade teacher, I was in the anti-decodable books camp.

A big reason for that had to do with my misunderstanding of how children learn to read. I thought kids should use three-cueing as they read leveled books.

Now, however, I understand that students need to read decodable text so they get practice applying the phonics skills we’ve taught them.

Another reason I was anti-decodable was that I was less than impressed with the decodable books in the market. At the time (*ahem years ago), most decodable books were boring, stilted, and not something kids would want to read again and again.

Times have changed, and now you can choose from a huge variety of quality, decodable books.

I’m adding my free decodable books to the mix because I want everyone to have access to quality decodables, regardless of their budget.

At the end of this post, you’ll find the foldable, color version of each book for FREE when you join my free newsletter.

What about comprehension and decodable text?Another reason I used to be anti-decodable was that I thought kids would read them sooo sloowwwly they wouldn’t be able to comprehend the text. (Either that, or the text was so stilted they wouldn’t be able to comprehend it no matter how fast they read it!)

It turns out that I was partly right.

When you understand the Simple View of Reading, you know that reading comprehension is the product of decoding ability AND language comprehension. Students must become proficient decoders and understand the language to become fluent. Fluency is the bridge between phonics and comprehension.

When kids are first learning to read, decoding takes a lot of mental energy. As students become more fluent, their brains are freed up for comprehension.

But that doesn’t mean that students shouldn’t make sense of the decodable text that they read!

I hired a custom illustrator for these books because I wanted the full story to be available through the pictures. (After all, an author can only include so many words when kids only know six letter sounds.)

Don’t get me wrong – students don’t need the pictures to read these books – but the pictures themselves provide opportunities for predicting, questioning, inferring, and other higher level skills.

Each book comes with a set of low and high level comprehension questions on the final page.

Just check out this flip book to see the first book in action!

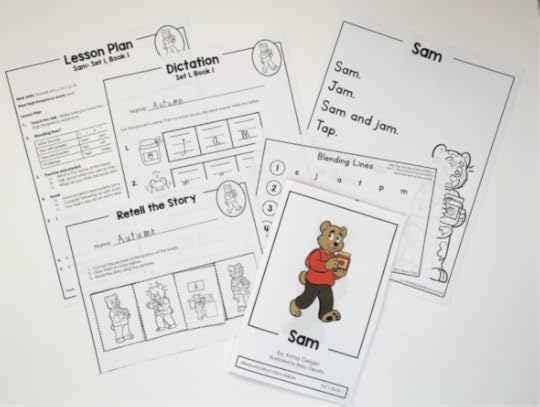

What’s included in the full set?The free books below are all you truly need to get started. But you’ll be blown away by the supplementary materials, as pictured below.

When you purchase the complete set of level 1 books with accompanying resources, you will receive:

Each book in multiple printing formats (each includes black and white)A single-page lesson plan for each book with introductory activities and tips for reading the book with studentsBlending lines that give decoding practice before readingA cut-and-paste retelling activity so students can retell the story using the picturesA dictation exercise so students connect letter-sound knowledge to spellingEach book on a single page with just one picture; use for partner reading and assessment at the end of the week!Free decodable booksClick on each book to get it for free! You’ll see a pop-up to enter your name and email address so the book comes right to your inbox.

You’ll also see a special offer to get the full set with supplementary materials (as described above).

The post Free decodable books appeared first on The Measured Mom.

February 6, 2022

Response to Fountas & Pinnell #9: Do teachers know best?

TRT Podcast#65: Response to Fountas & Pinnell #9 – Do teachers know best?

Fountas and Pinnell tell us that no literacy program can take the place of a teacher’s expertise. And they’re right! But expertise comes from knowledge, and that knowledge is not innate. In this episode I’ll share online courses that will improve your understanding of the science of reading.

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and you are listening to Episode 65 of the Triple R Teaching podcast. We are on the tail end of our reaction series in which I react to Fountas and Pinnell's blog series called "Just To Clarify," in which they answer questions and react to criticism of their work.

Today's question is question number nine, "Elevating teacher expertise has always been a hallmark of your work. What has led you to advocate so strongly that teachers are the single most important factor in a child's learning achievement?"

This is how Irene Fountas responds:

"Learning to read is complex and no reading program is an alternative to teacher expertise. Over the years, there have been many literacy programs, programs positioned as a one size fits all solution, and some acknowledging the complexity of literacy learning. However, students depend on the expertise of teachers – expertise in understanding the alphabetic system and how it works, expertise in the understanding of texts, including their opportunities and challenges, expertise in understanding each child's unique strengths and needs as a learner, and expertise in how literacy competencies develop in children over time. There is simply no literacy program that can take the place of a teacher's expertise in helping children develop an effective literacy processing system. With any set of resources, teachers will need to make moment-to-moment decisions based on their observation of children."

Okay, let's respond to that. I think there is a lot of good in there.

Number one, she acknowledges that learning to read is complex. Absolutely! If you want to make a first grade teacher mad, just tell her that anybody can teach first grade. Absolutely NOT true, especially because our first grade teachers have such an enormous responsibility in teaching children to read.

Louisa Moats has written a whole article called "Reading is Rocket Science," I'll link to that in the show notes. It's really important to remember that teaching reading is not simple. It is complex and the experience and knowledge of the teacher is very important.

I think Irene Fountas is right when she says that some programs are positioned as one size fits all. That's what publishers are going to do because they want you to think that, but most teachers can tell you that a single program does not fit all their needs. They have to use multiple programs to teach all the facets of literacy understandings, including phonics, phonemic awareness, comprehension, vocabulary, and fluency. They need multiple pieces and it is up to the teacher to use those pieces wisely.

Now I know there's a lot of talk about using programs with fidelity. There's something to be said for that, but I also think there must be teachers paying attention to what's happening right in front of them and not just reading from a script. That could be a whole other podcast series. Maybe it will be someday when we talk about out the qualities of explicit teaching and diagnostic teaching and just being a good teacher. Being a good teacher is way more than reading a script.

So I agree with what Fountas and Pinnell are saying here. I think the problem though, is that historically, balanced literacy and whole language advocates have put too much emphasis on what the teacher knows when the teacher might not know that much. We may feel that because we're in the classroom interacting with the kids every day that we can gather all the knowledge we need to make decisions, but we can't do that if we don't have anything to pin our knowledge on.

So let's say I'm looking at a student and I notice that she can't sound out words. Okay, that's good information to have, but what does that mean? Do I understand that when kids can't sound out words, it may indicate a problem with phonemic awareness and I may need to go back and work on that?

What about if a child is struggling to comprehend text? We can say he doesn't remember what he reads, but do we understand the elements of Scarborough's Reading Rope under language comprehension? Do we understand that we need to figure out where the missing link is and address that?

So making observations about our students isn't enough, right? We have to know what to do with that information. And we don't know what to do with it unless we educate ourselves.

Way back at the beginning of this "Just To Clarify" series, Fountas and Pinnell said that teachers who are hearing all this criticism or all this talk about the science of reading should put their heads down and just keep doing what they know works.

I think they missed a really good opportunity there to tell us that teachers shouldn't just "put their heads down," they should be studying! They should be reading. They should be learning. They should be taking courses. When you do all those things, then you're more qualified to be the person who makes these moment to moment decisions based on your observations.

A few years ago when I started really studying the science of reading, I read a lot of books and then I also took some online courses to help improve my knowledge and understanding. I'd like to share the names of those here with you, and then I'll also link to them in the show notes so you can check them out for yourself.

One that I think is really useful and affordable is called "The Reading Teacher's Top Ten Tools" by Deb Glaser. She makes it really affordable so you can take it just for a month. If you have a month and you can just watch everything and study it, then you can cancel your account. It's not something that gives you permanent access; it is a monthly payment. At least it was when I joined it. So if you don't have a lot of money to invest, but you have time, I would take a month or two to go through her program. Study everything, print the reference sheets, and you will have learned quite a bit.

What I like about this program is that she has a lot of videos of her actually in classrooms with students that help you see how this works in real life. I should note that while there's a lot of really good stuff in "The Reading Teacher's Top Ten Tools," she doesn't really give you the nuts and bolts. There's not a lot about how this is going to actually look on a day to day basis in your classroom, such as how to manage students during this part of your day. There isn't that sort of thing, but I'd say it's definitely a good step and definitely an affordable one.

Another course I've taken is from The Big Dippers. That's definitely one that you can trust, and the course is very useful because it gives you a really solid understanding of the science of reading. It's pretty short, and I would say it's really not going to give you a lot of video. So if you prefer to take in content via video, this is not the course for you. It's pretty inexpensive at one hundred dollars, but you only get access for six months. It's definitely a knowledge builder, but not something you're going to get to refer to for very long.

I also took the "Online Elementary Reading Academy" from CORE. CORE is a very good website, very trustworthy. They've got a lot of great resources and webinars and things. The course is expensive, however, it is pretty in-depth. They do have a lot of helpful videos and it actually is something that you're doing with a teacher so you can't sign up anytime. It's about seven to ten weeks, and while you can watch the videos at your own pace, you do have that time period to react with the instructor to ask questions.

So if you want a course in which you can connect with a teacher, this would be maybe a good one to try. It is currently six hundred dollars, so it's definitely on the pricey side. You do get a really fat book that comes with it which is really, really good. It's called the "Teaching Reading Sourcebook." Honestly, I would buy that even if you don't take the course, and also an assessment tool. So those two things are, I would say, easily worth a hundred dollars of what you pay.

Another one that I recommend is called "Keys to Beginning Reading" by Joan Sedita. I would definitely check out her website. She's got a lot of useful things on her blog and other things that you can check out that are free, but her course is excellent. It also includes a spiral-bound manual that walks you through a lot of the things that she teaches. So it really is nice because the course talks about all the elements of beginning reading. It gets very practical. There aren't a lot of student printable resources, but there are a small handful. So that's definitely another one to check out.

Of course, I would really love it if you would check out "Teaching Every Reader," which is my full online course. I published it with my colleague, Becky Spence, way back in 2017. That version of the course was a balanced literacy course. When we learned about the science of reading, we closed the course for about nine months and completely redid all the lessons.

When we made the course, we really wanted to make it into something that was accessible to everyone. So in each lesson there's usually a video, which you can speed up if you'd like, although most people tell me I talk too fast already. And then there is a transcript, so you can print the lesson to read it later. We have guided notes to guide you through the lesson.

There's a lot of teacher reference sheets you can print and, best of all, the course includes many, many, many, many student printables. It has resources for teaching phonemic awareness, phonics, and so on. These are all printables that you can print for your students. They're for centers, file folder games, editable resources, etc. It's a ton and we don't sell those anywhere else, they're only included in the course.

We even have a bonus module all about dyslexia.

When you join, you get lifetime access. So unlike some of the other courses where you join, but then after a couple of months you lose your access, you can have access to this for as long as Becky and I are operating online. We hope that will be for a few more decades. For example, people who bought the course in 2017 received all the updates completely free. When you join, you get all the updates to the course.

I'd love for you to check out the show notes today so you can learn more about all these courses that I've taken as well as the one that I've created. If you click through "Teaching Every Reader" and the doors are closed to the public, but you would like to join before the course opens, please send me an email, anna@themeasuredmom.com. I totally understand that when you're ready to learn, you're ready to learn, and so most of the time we can get teachers in between launches if you send us a private email.

Thanks so much for listening to this episode, and be sure to check out the show notes and all the courses I mentioned at themeasuredmom.com/episode65.

We'll be back next week for our final reaction to Fountas and Pinnell!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Emily Hanford’s response: Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Mark Seidenberg’s response: Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

Louisa Moats: Teaching Reading is Rocket Science

Deb Glaser’s The Reading Teacher’s Top Ten Tools

The Big Dippers course

Keys to Beginning Reading from Joan Sedita

Online Reading Academy from CORE Learning

My course: Teaching Every Reader

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Response to Fountas & Pinnell #9: Do teachers know best? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

February 5, 2022

Why you should include spelling dictation in your phonics lessons

Spelling dictation allows children to apply the sound-spellings you’ve taught in your phonics lessons. Keep reading to learn best practices for this important activity!

When you hear the word dictation, you might visualize an old-school boss dictating a letter to his efficient secretary, who is madly typing on a typewriter.

But today I’m talking about spelling dictation.

What is spelling dictation?This is when you dictate words and/or sentences to your students so they can write them on their paper. (Some teachers even dictate sounds, and have their students write the graphemes.)

It’s very important that you have pre-taught all the sound-spellings and high frequency words included in a dictation exercise.

In general, spelling dictation is not a test (although you might use it that way at the end of the week). Instead, you provide immediate feedback so students are sure to spell correctly (even if erasing is required).

Why should you include dictation exercises in your phonics lessons?Decoding (sounding out words) and encoding (spelling the words on paper) go together.

It only makes sense to tie spelling to the phonics skills we’ve taught.

Otherwise, spelling becomes a memorization game … and we all know how that goes. You always have those students whose diligent parents help them work hard all week to ace the test … and then they proceed to spell the words wrong the following week.

Let’s avoid this all-too-common outcome by tying spelling and phonics together.

How to do spelling dictation1. Prepare a list of up to 5 words and 1-2 sentences that you will dictate. Make sure the words include the most recent sound-spelling you’ve taught. The sentences should include review words as well.

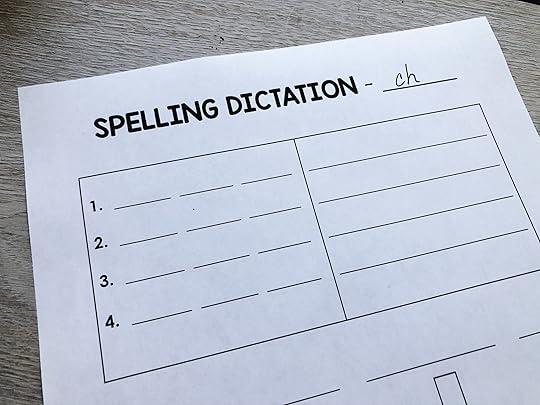

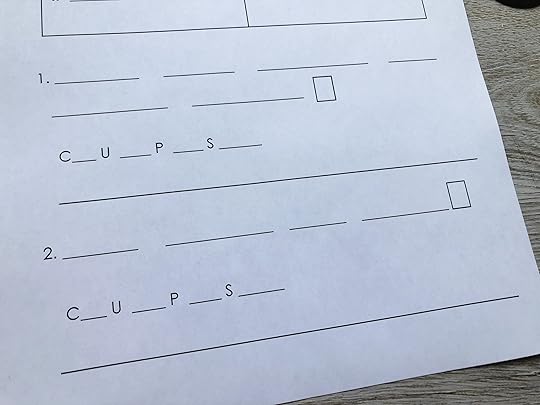

2. Provide a white board or worksheet for students to record their work. White boards are more fun and less time-consuming, but a prepared worksheet allows you to have a record of student work and encourages proper handwriting. You might want to switch between the two, depending on time constraints. A good practice might be to use a white board every third or fourth session.

3. If you are preparing a worksheet in advance, I recommend doing the following for word dictation: Draw a line for for each phoneme so students can write a single grapheme on each line.

4. After you dictate each word, write the correct spelling so everyone can see it. Have students check their work and rewrite the word correctly on a single line next to their original spelling (no lines or sound boxes this time).

5. Start small with sentence dictation; it’s exhausting for young writers. Gradually move from 1-2 sentences, and increase the length of the sentences as your students are ready.

6. If your students are doing dictation on a worksheet, prepare a set of lines for each sentence (one line per word.) After you dictate the sentence, have students repeat it as they point to one line for each word. They may need to repeat it again.

7. After students write a sentence, have them check it using CUPS.

C: Capitalization: Does the sentence start with a capital letter? For older students – are proper nouns capitalized? U: Usage: Does the sentence make sense? Have them read it aloud to make sure they didn’t miss any words.P: Punctuation: Does the sentence end with the proper mark? For older students – are other punctuation marks used appropriately?S: Spelling: Are all the words spelled correctly?8. After checking their work with CUPS, have students rewrite the sentence.

A sample dictation lesson for the digraph CHSomething important thing to rememberStart small!

My new decodable books series (coming soon!) includes a simple dictation worksheet for each book. Because the page pictured above is for the first book, the page includes just four words. Pages for later books also include a simple sentence.

Check out these posts to learn more about spelling dictation:

Spelling dictation with sounds, words, and sentences – Learning at the Primary Pond Spelling dictation with sentences – All About Learning PressStay tuned for the rest of our phonics series!The post Why you should include spelling dictation in your phonics lessons appeared first on The Measured Mom.

January 30, 2022

Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #8: Is structured literacy responsive?

TRT Podcast#64: Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #8 – Is structured literacy responsive?

Fountas and Pinnell are proud to describe their approach as responsive; rather than follow a script, they make observations and tailor their instruction to meet individual needs. They insinuate that more structured programs don’t allow teachers to adjust for individual students. Is that a correct assumption? Is structured literacy responsive?

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, this is Anna Geiger from The Measured Mom. You are listening to Episode 64 of the Triple R Teaching Podcast and episode eight in our series of responses to Fountas and Pinnell's blog posts in which they defend themselves against criticism of their work. In addition to responding to criticism, they also answer questions and one of those we're going to address today.

The question is, "What do you mean by 'responsive teaching' and why is it important?

This is part of Gay Su Pinnell's response to that question:

"Responsive teaching meets students where they are and takes them where they need to go next in their learning. It's a highly complex process. It's a constant cycle that takes place across multiple instructional contexts. The teacher would notice the language children use during oral discussion of books that they hear read aloud, what they write in their reader's notebook about books they've read, what they write in the writing process, what they write in response to reading in guided reading, read aloud, and their own choice books. So the teacher is always gathering data across five contexts for teaching reading and five contexts for teaching writing, as well as a daily direct, explicit, and systematic teaching of phonics, phonemic awareness, and vocabulary and spelling.

"So, you're really looking across the language arts with the best knowledge of how readers and writers and spellers develop over time. Just to be very clear, responsive teaching is not a label and it is not a relabeling of anything called 'balanced literacy' or even 'whole language approach' to literacy learning. We have always advocated for a child-centered, responsive approach to literacy learning, not a program-centered approach. A child-centered approach. One that focuses on observation and assessment rather than holding to a script is much more than a label. This approach, focusing on the child, enables teachers to be constructive, inquiry based, language based, and to engage each child's strength and curiosity.

"With responsive teaching, educators can respond to and meet children where they are in their learning — to teach the child, not the program, not the book. In this way, teaching reading is a science, a science of observation, decision-making, and knowledge. And this is what we call responsive teaching."

Sounds good, right? And a lot of that IS good because we don't want a script that we refer to constantly without veering off script, right? We want to be aware of the students in front of us and not follow a list of questions without paying attention to the students' answers.

My first year of teaching first grade, I was required to use a scripted phonics program. I will be upfront with you, I hated it. I thought it was awful.

Looking back, I still think it was awful, but it would've been helpful if I understood the value of some of the pieces. I think if I understood how important a lot of those basic skills were, I would not have been so unhappy about implementing the program. I think that would've been conveyed more to the students, and I could have made it more exciting.

The teacher next door loved the program. She thought it was great because of all the foundational skills it was teaching. I have a feeling her class did a lot better with it than mine did!

That experience soured me on scripts, but I have to say, probably a big reason for that is I was immersing myself in books by Fountas and Pinnell, Regie Routman, Lucy Calkins, and others in the whole language or balanced literacy general field who tell teachers over and over that they're the ones who know their students best and they are the ones that should make the decisions. I would never want to take away from teachers or tell them that they don't matter, that anybody could go in and teach this program because that's just not true!

Still, I think we need to be aware that this idea that we're just watching the students, taking notes, and then deciding what to teach next can be problematic because it requires a great deal of skill on the part of the teacher to do this well.

I think so many teachers are thrown into these balanced literacy classrooms, perhaps as brand new teachers, and they don't have that experience yet. They're not really sure how to have all these organized, observational assessments and then act on those. It's really hard to do, even for an experienced teacher.

So I think that this all sounds really great, but it's really hard to put into practice.

I also want to address that the structured literacy approach is NOT against working with students in what they know. In fact, diagnostic teaching is an essential piece of the structured literacy approach.

On The Big Dippers website, which is all about the science of reading, they write this, "Diagnostic: A characteristic of reading instruction where the teacher monitors the progress of their students, being alert to where skill gaps exist, and adjusts instruction based on students’ immediate needs."

Did you catch that, "immediate?" That sounds a lot like what Fountas and Pinnell are talking about. They want you to be attuned to the students in front of you. A good structured literacy teacher will do that.

The Big Dippers website also goes on to explain what that looks like. They write, "Teachers use formal and informal data to inform instruction. When working with students in small or large groups, the teacher is consistently monitoring the progress of students in order to measure effectiveness towards the specific target. Educators are also able to intervene appropriately so students can achieve automaticity and mastery of a skill or concept. Information about a student’s understanding and mastery is used to inform how a teacher plans explicit instruction in a thoughtful manner. Teachers can look for patterns in student errors to pinpoint specific deficits in reading skills or concepts and determine if a change in instruction is needed."

Now when I taught with a balanced literacy approach, I had a lot of ways to collect informal data. I have to say though, most of it was just stored in my head because I was so busy managing all the pieces of our day. I didn't do a lot of formal reading assessment, probably because I didn't see the value in it and I didn't know what to do with the results.

There's a really good blog post recently published on the Right to Read Project by Margaret Goldberg and it's called "Data: The Closest Thing We Have to a Crystal Ball." She is talking about how, as a balanced literacy teacher, she resisted these formal assessments. She didn't think they told her what she really needed to know. She thought it was a waste of time.

At the end of the post she explains what she wishes she had known, as a balanced literacy teacher, about data and data collection. One thing that she notes is that screening data tells us whether our approach is working. Families have a right to know if their child is likely to experience difficulty with reading.

This is getting a little off topic, but I'm currently reading the book "Overcoming Dyslexia" by Sally Shaywitz, and she says over and over in there how important it is to give early screening to kindergartners so that we know if it looks like they're likely to have challenges with reading. That way we can address that head on from the very beginning.

SO many times I hear people say, "Oh, they'll catch on," or "By third grade, everybody catches up." I don't know where that comes from, by the way. I've never seen any research to back up that idea. In fact, I see things to the contrary all the time.

The fact is screening assessments are important. They help us know if there are certain students who would benefit from extra intervention. They help us know if what we're doing is working. They help us know if our students are getting closer to meeting their goal.

So yes, responsive teaching is important, but it's not just observation. It is also specific, formal assessment that we give at different periods of the year, and then we use that to inform our instruction and thereby help individual students.

So that's my reaction to the Fountas and Pinnell "Just to Clarify" series episode eight. We have two more to go. If you want to find the show notes for this episode, you can head to themeasuredmom.com/episode64.

Thanks for listening and we'll see you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Emily Hanford’s response: Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Mark Seidenberg’s response: Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

Data: The Closest Thing We Have to a Crystal Ball – from The Right to Read Project

Science of Reading and Structured Literacy: What’s all the Buzz About? – The Big Dippers

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #8: Is structured literacy responsive? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

January 29, 2022

How to use blending lines

Today we’re going to talk about blending lines – a powerful, easy-to-use tool that will help your students become masters at decoding!

It’s the fourth post in our 10-part series about teaching phonics.

Blending is the stringing of letter sounds to read a word.

There are two main types of blending:

Successive blendingFinal blending*Weird but important note: Some phonics experts use the terms “successive blending” and “final blending” differently. Beck and Beck (Making Sense of Phonics) use the terms as I will use them in this article. Wiley Blevins, in his book (A Fresh Look at Phonics) switches the terms around.

Successive and Final BlendingSuccessive blending

Successive blending is an excellent way to introduce blending to your students, and children who struggle will benefit from extended use of this approach.

The power of successive blending is that it helps students keep the sounds in their heads; short-term memory issues are a real problem for students who sound out p-a-t and come up with “tan.”

While you should phase out successive blending after a few weeks, Beck and Beck recommend temporarily bringing it back when students start reading words with beginning blends (such as flat and swim).

Final blending

Final blending (which I like to call “sound by sound blending”) is more efficient and the method you should use when your students understand the concept of blending.

However, if you are working with an individual student who is struggling, switch back to successive blending.

Watch this quick video to understand both types of blending.

(For a longer video of successive blending, see this post.)

Best practices for teaching blendingIn his book, A Fresh Look at Phonics, Wiley Blevins share these tips for teaching blending:

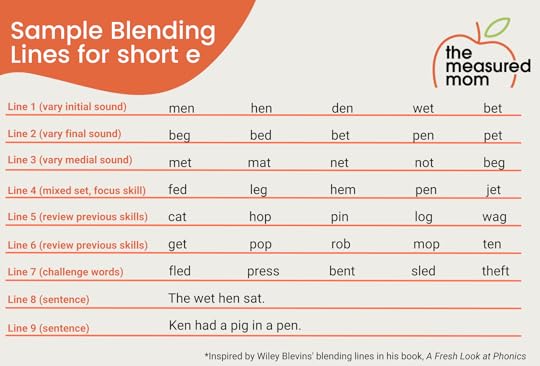

Model and practice blending often (every day for early readers).When starting blending with new readers, use words that start with continuous sounds (such as mmmm and sssss).Practice blending before reading a story (at least 20 words in 1st grade and up).Select blending lines that include minimal contrasts so students have to fully analyze the words.Create lines that allow you to informally assess your students.Make sure your lines contain differentiated practice to meet everyone’s needs.Include sentences in your lines.What are blending lines?Blending lines are lines of words that students sound out using their phonics knowledge. Blending lines allow students to practice the new focus skill and review previously learned skills.

Students should read the these lines after the lesson but before reading their decodable book.

You can use the lines with a whole class or in a small group phonics lesson.

Sample blending lines

Wiley Blevins’ tips for using blending lines

Model only one or two words at the beginning of the word set. You want your students to do the work.Have students read the words chorally the first time through (observe to see which students drop out as the words become more challenging).Revisit the lines by pointing to words in random order and calling on students to read them. Remember to call on struggling readers for the easier lines and advanced readers for the challenging ones. Keep the whole class engaged by having them give a thumbs-up to indicate when a word is read correctly.Use the lines for multiple days of instruction as a quick review or warm-up.Make copies of the week’s lines for students to take home and practice.Make sure that the time spent on the lines is no more than 5 minutes at a time.More sample blending lines

So what do you think?

Are you ready to give blending lines a try?

It can be tricky to write your own blending lines, but I’ve made it easy for you!

As you can see in the above image, I’ve created a planning sheet for you that reminds you what to focus on for each line.

After you type in the words on the planning sheet, they auto-populate into the student page.

The page prints without the blue boxes, making it the perfect practice sheet for your students.

Just sign up below to get the freebie!

Get your editable blending lines pages!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The post How to use blending lines appeared first on The Measured Mom.

January 24, 2022

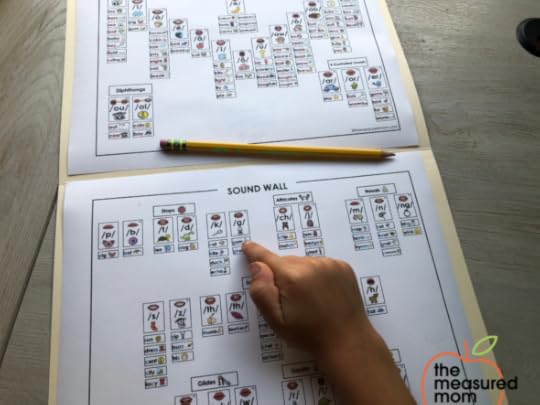

How to use a sound wall

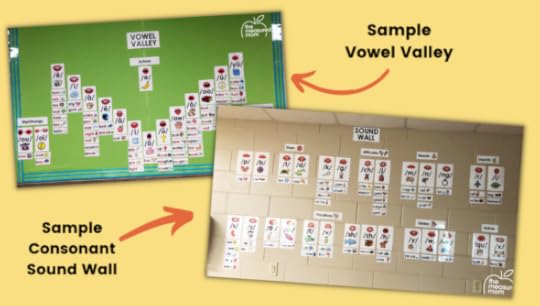

I’m sure you heard the buzz about sound walls.

Most literacy experts are telling us to replace our word walls with sound walls.

And I agree.

But what exactly IS a sound wall, and how do you use it?

We’ve got the answers in today’s post!

What is a sound wall?

What is a sound wall? A sound wall is a visual reference to help students when they are reading and spelling.

Unlike a word wall, where words are displayed by their beginning letter, a sound wall displays the 44 speech sounds by manner and place of articulation in the mouth.

(Plain English = A sound wall organizes and displays speech sounds based on what your mouth is doing when you make them.)

Sound walls usually include pictures to represent what the mouth looks like when making each sound. An anchor picture is included with the mouth card.

As students learn different phonics patterns that represent the sounds, these patterns (or words featuring the patterns) are added to the wall.

Why use a sound wall instead of a word wall?

Why use a sound wall instead of a word wall?A traditional word wall displays high frequency words by their first letter. Teachers direct students to the word wall to find words they want to spell.

The problem is that we have 44 individual sounds in the English language, but only 26 letters. A student may look for the word “the” on the word wall but not know where to look, because “the” doesn’t begin with the /t/ sound.

A sound wall makes a lot more sense, because it starts with the SOUND instead of with print.

As you teach your students to use and become familiar with the sound wall, they will learn to use it as a reference when spelling.

Three things you need to understand to use a sound wall effectively

Three things you need to understand to use a sound wall effectively1. Understand the difference between phonemes and graphemes.

A phoneme is a sound. We represent sounds by putting a letter or letters between virgules (slash marks). For example: /s/ represents “sssss.”

It’s important that we can break words apart into their individual phonemes. The word “sand” has 4 phonemes: /s/ /ă/ /n/ /d/. The word “fox” also has 4 phonemes: /f/ /ŏ/ /k/ /s/. The word “eight” has only 2 phonemes: /ā/ /t/.

Graphemes are the letters used to represent a phoneme. In the word “eight” the grapheme “eigh” is used to represent the phoneme /ā/. Even though the word has 5 letters, it has only two phonemes.

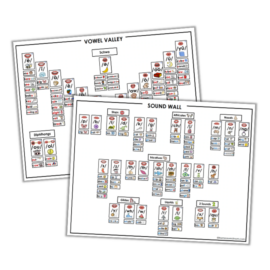

2. Understand the vowel phonemes.

On a sound wall, the 19 vowel phonemes are arranged based on the place of articulation. In other words, they are arranged by the openness of the jaw and the tongue height/placement when you make each of the phonemes.

The vowel phonemes are arranged in a V shape (“Vowel Valley”) to mimic the motion of your chin as you make the sounds. Notice that your mouth is most open when you make the short o sound, which is at the bottom center of Vowel Valley.

A few important notes: We count r-controlled vowels as single phonemes. For example, in the word “farmer” we have just 4 phonemes: /f/ /ar/ /m/ /er/. We also count diphthongs as single phonemes, even though a diphthong is formed by combining two vowels in a single syllable. For example, in the word “coin” we have 3 phonemes: /k/ /oi/ /n/.

Finally, did you know that the schwa is the most common vowel sound in the English language? It occurs in an unaccented syllable and usually sounds like a weak version of /ŭ/, as in banana. It can also sound like /ĭ/, as in cactus.

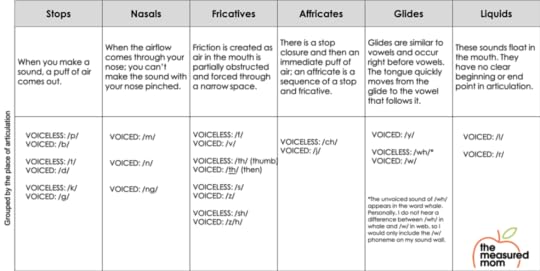

3. Understand the consonant phonemes.

There’s more to remember when it comes to consonant phonemes.

Sound walls organize the consonant phonemes into 6 categories: stops, affricates, nasals, fricatives, glides, and liquids. Each category contains both voiced and unvoiced sounds. A voiced sound is made from the voice box. Put your hand on your throat when you say a sound to feel if it is voiced (you will feel a vibration in your throat) or unvoiced.

Take a minute and read through the sounds in each column on the chart below. Put your hand on your throat as you say the sounds aloud; notice the difference between voiced and voiceless sounds.

How should I set up my sound wall?

How should I set up my sound wall?I recommend choosing two areas in your classroom to display the consonant sound wall and vowel valley.

When you set up vowel valley, I recommend starting in the center of the display area and working your way up and out. This way it’s easier to keep things lined up properly.

Important note!

Do not set up the consonant sound wall and vowel valley in their entirety unless students have already learned all the phonemes and their corresponding graphemes. This is highly unlikely unless you are teaching third grade or above. Instead, put up just the phonemes and graphemes that students learned in their previous grade.

If you are setting up a sound wall in kindergarten, the wall will be empty (or you will post the phonemes/graphemes and have them turned over or “locked” until you teach them). If you are setting up a sound wall in first grade, you will have short vowels and consonants posted to start the year. You will gradually add other phonemes with graphemes. If you are setting up a sound wall in second grade, you will have the consonants, short vowels, and many long vowel graphemes posted to start the year.

What order should I follow when teaching phonemes and graphemes?

What order should I follow when teaching phonemes and graphemes?This depends on your phonics scope & sequence. There is no perfect scope and sequence, but I have created my own sequence based on my experience and study. You can get it for free in this post.

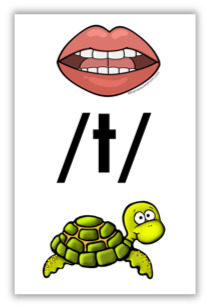

What could sound wall lessons look like?SAMPLE LESSON #1When teaching a new letter sound-spelling, you can follow a routine like this one.

1. Introduce the phoneme and anchor picture.

(Hold up the /t/ card.)This picture is a turtle. What is the picture?” (TURTLE)The first sound in turtle is /t//t/ /t/. Say the sound. (/t/)

(Hold up the /t/ card.)This picture is a turtle. What is the picture?” (TURTLE)The first sound in turtle is /t//t/ /t/. Say the sound. (/t/)2. Talk about the formation of the sound.

Take out your mirror and look at your mouth when you make the /t/ sound.”What is your tongue doing? What are your teeth doing? Are your lips doing anything? Feel your throat when you say the /t/ sound. Is this a voiced sound? Put your hand in front of your mouth when you say /t/. What is the air doing? (It’s making a little puff.) We call the/t/ sound a stop sound.3. Practice forming the new letter.

“The way we spell the /t/ sound is with a t. Watch me make the letter t in the air.”“Now let’s make a t in the air together.”4. Teach the key word for the sound-spelling.

Our key word for the t spelling is ten. What’s the key word? (ten)When you are writing a word and it has the /t/ sound, use a t. I am going to say some words. Repeat the word after me. Then put your thumb up if the word begins with /t/. Put your thumb down if it does not. (ten, tiger, dog, toaster, pencil, turtle, top)SAMPLE LESSON #2

Our key word for the t spelling is ten. What’s the key word? (ten)When you are writing a word and it has the /t/ sound, use a t. I am going to say some words. Repeat the word after me. Then put your thumb up if the word begins with /t/. Put your thumb down if it does not. (ten, tiger, dog, toaster, pencil, turtle, top)SAMPLE LESSON #2When students already know the basic phoneme and are learning a new grapheme, it could look like this:

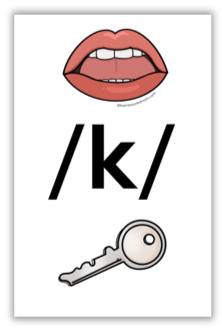

1. Review the header card with the anchor picture.

Today we are going to learn a spelling for the /k/ sound.(Hold up the /k/ card.)This picture is a key. What is the picture? (KEY)The first sound in key is /k/. Say the sound. (/k/)

Today we are going to learn a spelling for the /k/ sound.(Hold up the /k/ card.)This picture is a key. What is the picture? (KEY)The first sound in key is /k/. Say the sound. (/k/)2. Teach the new grapheme and key word.

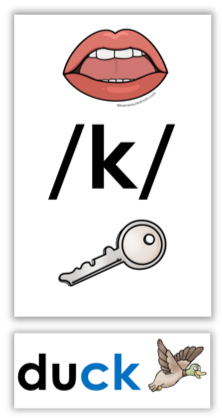

When the /k/ sound appears at the end of a word, it is sometimes spelled C-K.”Here is our key word for the ck spelling at the end of a word: DUCK. Say the word.When a one-syllable word has a short vowel sound and the /k/ sound follows, we spell it with the letters c-k.If I am spelling the word sack, for example, I can start by breaking the word into phonemes. /s/ /ă/ /k/. Repeat the phonemes of sack. /s/ /ă/ /k/

When the /k/ sound appears at the end of a word, it is sometimes spelled C-K.”Here is our key word for the ck spelling at the end of a word: DUCK. Say the word.When a one-syllable word has a short vowel sound and the /k/ sound follows, we spell it with the letters c-k.If I am spelling the word sack, for example, I can start by breaking the word into phonemes. /s/ /ă/ /k/. Repeat the phonemes of sack. /s/ /ă/ /k/3. Practice spelling one or more words with the new grapheme.

I’m going to draw three lines to help me write the word. I’ll spell one phoneme on each line. S….. What letters makes the /s/ sound? Yes. I will write an “s” on the first line. Aaaaaa. What letter represents that sound? Yes, the letter a. I will write that on the second line. Now we are at the final sound, /k/. This is when I need to remember our new pattern. At the end of a single syllable word, when the /k/ sound follows a short vowel, I use ck to spell the /k/ sound. I will write ck on the last line. How do we spell sack? S-A-C-K4. As time allows, do guided dictation.

We’re going to spell the word PICK. What’s the word? (PICK)Let’s count the sounds in the word pick. /p/ /i/ /k/How many sounds? (3) Draw three small lines on your paper, one for each sound.What’s the first sound? What letter represents that sound?What’s the second sound? What letter represents that sound?What’s the final sound? What will you write to represent that sound?How can I make the sound wall more meaningful to my students?If you’re anything like me, you’ve put up a word wall and mostly forgotten about it.

We don’t want that to happen with our sounds walls!

In addition to regular, consistent sound wall lessons (even 5 minutes a day is helpful!), give your students their own portable sound walls to keep as a reference.

They might enjoy highlighting the key words as you add them to your large sound wall and vowel valley.

In fact, you can download FREE portable sound walls (pictured above) at the end of this post!

After you sign up for the freebie, you’ll learn how to get my FULL set of sound wall printables.

P.S. If you’re nervous about using a sound wall, or aren’t sure you’ll get it right, set aside your fears and just START. We all have to start somewhere, and I think you’ll be amazed at how soon you get the hang of it!

Get your free portable sound wall and vowel valley!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The post How to use a sound wall appeared first on The Measured Mom.

January 23, 2022

Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #7: Do Fountas & Pinnell promote “balanced literacy?”

TRT Podcast#63: Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #7 – Do Fountas and Pinnell promote “balanced literacy?”

Fountas and Pinnell are steering clear of the label “balanced literacy.” But should they? Do they deserve the label?

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello! Welcome to Triple R Teaching, Episode 63. I'm your host, Anna Geiger, from The Measured Mom, and we are in episode seven of our reaction to the Fountas and Pinnell "Just to Clarify," blog series.

Question seven says, "Some people have referred to your work as 'balanced literacy' or 'whole language.' Do these labels accurately describe your work?"

Here's what Irene Fountas had to say:

"We are not fans of using labels to describe literacy instruction because they often mean different things to different people. We have always advocated for teachers and leaders to describe their literacy practices and rationales, rather than label their approach. In our first professional book, 'Guided Reading,' published in 1996, we used the word 'balanced' as an adjective when describing a high-quality language and literacy environment that would include both small group and whole group differentiated instruction that included the various types of reading and writing, letter and word work, oral language, observation, assessment, homeschool connections, all supported by good teaching. Since that time, the term 'balanced literacy' has become a label that means many different things over the years. To some, it means a little of this and a little of that. Rather, we choose to describe effective literacy instruction. Rather, we choose to use terms like 'responsive teaching' or 'effective literacy teaching.'"

I think that what Irene Fountas is saying here is fair. I think it's best not to label a specific practice as "balanced literacy" or "whole language" or "science of reading" or "structured literacy." It's best to look at specifically what is being taught and why.

However, these labels can be useful, right? If we know that something is aligned better with the idea of what balanced literacy is, we know it's not something we're going to want to use because that's in contradiction with the current reading research. I think it's fair though for them not to want to have the "balanced literacy" or "whole language" label.

I always thought that Fountas and Pinnell came up with the "balanced literacy" label, but in doing research for this episode I learned from a Reading Rockets article by Timothy Shanahan, that it actually came from Michael Pressley.

Michael Pressley was actually a big phonics guy. He was one of the authors of the "Open Court Phonics" program at the time, but he wanted to, as Timothy Shanahan writes, "heal the great divide between people like him and the whole language advocates."

The idea of balanced literacy in the beginning was not a bad one. The idea was to help both sides get along and to see the value in both approaches. To me, the value in the "phonics approach" is explicit, systematic, structured teaching, and the value in the "whole language approach" is helping kids develop a love for reading.

We CAN have both, but there are things from the whole language approach that are a real problem that unfortunately have leaked into what we consider the balanced literacy approach. And a lot of that has to do with haphazard teaching of basic skills.

As Timothy Shanahan writes in this article,

"Unfortunately, 'balanced' too often means that kids don't get substantial explicit instruction in chronological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, spelling, handwriting, oral reading fluency, reading comprehension, or writing. Studies show repeatedly that explicit instruction in these is beneficial in moving kids forward in literacy learning and the idea of balancing these essentials against something else is bothersome. It's time we retire the balanced literacy."

To many people today, especially in the science of reading community, Fountas and Pinnell and Lucy Calkins are synonymous with the balanced literacy approach.

They may not want that label, which I understand because as I've said before, there are many different understandings of what balanced literacy is. There are many different definitions and no one wants to connect themselves with a label that's not clear.

But I think when we consider balanced literacy as this approach in which we focus more on activities than skills, in which we have something of a haphazard approach to phonics and phonemic awareness, in which we focus more on the love of reading than on the skills kids need that will get them to love reading, then I think it's fair to say that Fountas and Pinnell are advocates of a balanced literacy approach.

That's my response to this episode of "Just to Clarify" by Fountas and Pinnell. Go ahead and check out the show notes at themeasuredmom.com/episode63. There I'm going to link to several articles about balanced literacy, and you can decide for yourself, are Fountas and Pinnell balanced literacy instructors?

We'll see you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Fountas & Pinnell’s series: Just to Clarify

Emily Hanford’s response: Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Mark Seidenberg’s response: Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

My blog post: The difference between balanced and structured literacy

Unbalanced comments on balanced literacy, by Timothy Shanahan on Reading Rockets

Balanced Literacy’s Crumbling Foundation, by Margaret Goldberg on Reading Rockets

At a Loss for Words, by Emily Hanford

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Reaction to Fountas & Pinnell #7: Do Fountas & Pinnell promote “balanced literacy?” appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Anna Geiger's Blog

- Anna Geiger's profile

- 1 follower