Anna Geiger's Blog, page 20

May 12, 2022

What teachers should know about dyslexia

Do you suspect that one of your students may have dyslexia? Here’s what every teacher should know!

As I look back to the students that I taught, I can picture one particular little boy who I’m sure had dyslexia. He was a bright, articulate, and kind first grader.

On one particularly rough day of teaching, he gave me a little blue gem shaped like a heart. “This is for you, because you’re the nicest teacher I’ve ever had.”

I’ll admit that I wasn’t feeling like a very nice teacher that day. This sensitive little guy knew I needed some encouragement!

He was all ears during whole class read alouds and his language comprehension was excellent.

But he struggled to get words off the page.

At the time I was a balanced literacy teacher. I advised his parents to read to him more (which they were already doing), and I gave him more practice with leveled texts.

He was a hard worker, and he had committed parents. But nothing we did made a whole lot of difference.

That little boy is now in his mid-twenties, and I hope he found a teacher who gave him more help than I did.

This is what I wish that I knew about dyslexia.

1. Dyslexia is real, and it’s more common than you might think.Recently a friend of mine told me that her graduate school professor told her that dyslexia doesn’t exist.

Lest you think this was decades ago, it was 2015. 2015!

Dyslexia is real. People can have mild, moderate, or severe dyslexia.

The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity says that up to 20% of students have dyslexia. It is the most common learning disorder.

There is much that we can do for students with dyslexia, but there is no cure. Our students will not “grow out of” dyslexia.

2. Dyslexia is a language-based learning disorder.Old myths die hard. Dyslexia is not about seeing letters or words backward.

It’s most commonly due to a difficulty in phonological processing.

According to Sally Shaywitz (Overcoming Dyslexia), dyslexia is an unexpected reading difficulty for someone who has the intelligence to be a much better reader.

This is the International Dyslexia Association’s official definition:

“Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede the growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.”

(If that felt like a mouthful, that’s because it is. Dyslexia is difficult to define, and experts don’t always agree on the definition.)

3. Early screening helps us know which students are at risk for dyslexiaClues for dyslexia can appear even before a child starts school, so it’s imperative that teachers use a screener to detect red flags.

Recommended reading:

Signs of dyslexia

Screeners do not diagnose dyslexia. But they do tell us which students would benefit from more testing. Get a free dyslexia screener at This Reading Mama.

4. It’s a big mistake to take a “wait and see” approach.

4. It’s a big mistake to take a “wait and see” approach.Early identification is crucial so that students can get the help they need. We’ve learned that the brain responds best to intervention when children are young. As we get older, our brains get less “plastic.” We can still help older, dyslexic readers, but the process will be harder than it would have been when they were young.

Many students with dyslexia need one-on-one tutoring so they can move forward. As a teacher, it’s your job to alert parents to this need.

5. Students with dyslexia need a structured literacy approach.Students with dyslexia can learn to read with the right approach. The good news … ALL students benefit from structured literacy!

Structured literacy uses explicit, systematic teaching to teach the following elements:

phonologysound-symbolsyllablesmorphologysyntaxsemanticsStructured literacy is very different from the way I used to teach reading – using predictable, leveled texts and three-cueing. Balanced literacy approaches will not teach dyslexic students to be successful readers.

Learn more in our structured literacy blog series

What is structured literacy?

6. Students with dyslexia need reasonable accommodations.

Here are a few that make sense in a primary classroom.

Allow more time for test-taking.Repeat directions as needed.Use daily routines so it’s easier for students to know what is expected.Give small, step-by-step instructions.Build in daily review.Provide books on audio.Also read: Accommodations for Students with Dyslexia (from the IDA)

7. You can be the teacher that makes all the difference.

7. You can be the teacher that makes all the difference.When you educate yourself about dyslexia, point parents in the right direction, and change the way you teach so that you reach all learners, you will make an incredible, lasting impact on the child’s life.

Here’s how to learn more!

Read Conquering Dyslexia , by Jan Hasbrouck. It’s short, easy to read, and practical. You can read it in a weekend!Read Dyslexia Advocate , by Kelli Sandman-Hurley to know how to help a child with dyslexia within the public education system.Bookmark the International Dyslexia Association’s website. Its printable fact sheets are extremely helpful! Read the rest of our blog series, linked below!Check out the whole seriesPart 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9

The post What teachers should know about dyslexia appeared first on The Measured Mom.

May 1, 2022

Whole class vocabulary activities to make those words STICK

TRT Podcast#77: Whole class vocabulary activities to make those words STICK

These simple activities will help your students make new words part of their expressive vocabulary … and they take just a few minutes each!

��

Listen to the episode here

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, hello! Anna Geiger here with Episode 77 of the Triple R Teaching podcast. Today we're talking vocabulary. We're going to talk about what it looks like when you're introducing vocabulary in the context of your whole class read alouds, and then we'll talk about some simple, easy activities that you can do during the rest of the week to help students embrace these words and really make them part of their own vocabulary.

**Are you ready? It's coming soon. The doors to our online course, Teaching Every Reader, open to the public only twice a year, and they're opening again on May 16th, 2022! When you join you'll get lifetime access (including all future updates) to eight video modules, which include printable resources, assessments, and dozens and dozens of student resources. One of our students, Sarah, had this to say, "I absolutely loved this course and have recommended it to our entire district. For the first time ever I feel confident knowing that I have the tools I need to teach reading well." To learn more, visit teachingeveryreader.com.**

I really think it's important to teach new words in the context of a read aloud or text that students are reading, rather than refer to a list of tier two vocabulary words for grade one or whatever grade you teach. I think it makes much more sense to teach in context, because as much as we might like to have one, there is no list of words for first grade, second grade, third grade, etc., it just doesn't exist.

What we're really going for is to teach those tier two words. Tier two words means words that are words you're going to hear - perhaps in conversation, or you're going to read, but they may not be words you're familiar with. These are high utility words, but they're not basic words. They're a little more advanced, but they're also not technical.

A tier three word would be a word like "baleen" if you're studying whales. Those words certainly have their value, but typically when you're teaching vocabulary from a read aloud, unless it's a very specific nonfiction text, you're going to be teaching those tier two words.

The cool thing is the words don't actually have to be in the book. Sometimes when you're teaching kindergarten or first grade, there's a really great book you want to read aloud with a good message and a lot of good things to discuss, but there isn't really any advanced vocabulary in the book. You can choose words that are related to the content.

For example, I was reading aloud to my little guy a number of months ago, and we were reading a book called "The Art Lesson" by Tomie dePaola. I believe it's a true story about the author when he was young and his experience in art class in school, but there's no advanced vocabulary, so I put the words "excited," "frustrated," and "disappointed" on sticky notes and we used those to mark how he was feeling in different parts of the book. First, I discussed what the words meant, then we applied their definitions to the text, and at the end we went back to look at the different parts of the book when he was feeling those emotions.

So your first step then after you've chosen your read aloud is to pick your vocabulary words and consider related words if there are no specific words in the text you want to teach. Before you do the reading, introduce the words, talk about them a bit. It's up to you how much in detail you want to go about their meanings, if you're going to be using words whose meanings can be figured out using context, you may want to wait.

You might say, "One of the words we're going to be learning about today is 'damp.' Keep your ears open for that word, I'm not going to tell you what it means. When we get to it I want you to think about what it could mean based on the context." Then as you read you'll stop briefly to talk about each of these words, and when you're finished reading you'll discuss them again.

So that first step is to choose the words based on the read aloud you're reading and introduce them.

But, of course, that may not be enough. It's also good to have review activities throughout the week, perhaps throughout the year, that come back to these words so that students can really make them a part of their own speaking and writing vocabulary.

One that I like to do that's very, very simple is Thumbs Up, Thumbs Down. I ask a question or maybe make a statement using one of the words, and if students agree, they put a thumb up, if they disagree, they put a thumb down.

For example, let's say the word is "delighted." I might say, "I was delighted when I found out that we were having mashed potatoes for supper." Now, everyone can have a different opinion, right? Actually my little guy can't stand mashed potatoes, he can't stand potatoes of any kind which I think is really odd, but it's been like that since he was a baby. I always make him have a tiny bit of one, which is always too much. Regardless, he would put his thumb down for that sentence.

You could just have a few of those example pre-written and ready to go so that when you finish the read aloud it could be your review activity, or you could put it on a clipboard and do those the next day when you have a couple of minutes.

Something else to do is to have a simple discussion using the word. Let's say the word is "cautiously." You could say, "If you're walking through a dark cave, you need to do it cautiously. What are some other things that you should do cautiously?"

Another activity that I like to do is Fill in the Blank. Let's say you've got three words that you're working on with a read aloud, which I think is a good number. You could have a set of three sentences where each one needs a blank filled in, and it would be one of those three words. I like to have the three sentences relate to each other, to kind of tell a story. I do multiple sets, maybe three sets of sentences, so that's nine examples where we're going to fill in the blank. You could put those sentences up on the board if you want and have the words on cards and students use sticky tack or something to put them in their spot, or you could put this on a screen and have them move the word, or you could just do it orally. Although I think it's really good to have the sentence displayed for kids, it really helps.

Something else you can do is have your students complete a semantic gradient activity. A semantic gradient is a list of words in order by degree, and it's somewhat subjective, there's not always one exact answer.

For example, let's say you've taught your students the word "dart." As in you "dart" somewhere, as in a synonym for "walk" or "run." You could put a whole bunch of other words that are related to that on little index cards and have students work together in groups to put them in order from slowest to fastest. So there might be words like "crawl," "meander," "stroll," "walk," "jog," "dart," "run," "sprint." See what I mean?

When they work together with that they really have to think about the meanings of the words and the benefit of doing it in a group is that some students may not know some of the words but others may. Semantic gradients can be useful, it won't work with every word, but that's just something to keep in mind.

You could also have students act out the word if possible. I was recently reading aloud "Little House in the Big Woods" by Laura Ingalls Wilder to my youngest two, they're in kindergarten and second grade. We were reading the chapter where the grandpa in the 1800s had to walk solemnly to church. He could not smile. He could not laugh. He could hardly even talk. I had my kids show me what that would look like to walk solemnly. We acted out what it would be like to sit solemnly in church and stare right at the preacher and not turn or anything. This, I think, really helped them solidify the words. So acting out is another good one.

Finally, this is something I heard about somewhere, I can't remember, it was a particular blog years ago and they called the vocabulary words they had taught brain words. Whenever students heard the word in a different read aloud or a different context or maybe even in conversation in class, they would tap their brain as a signal to say hey, we know that word! That just promotes awareness around the words that you've already taught.

So there you go. Those are some ideas for helping your students really master the new vocabulary that you're teaching them. You can get the show notes, including the transcript, so you have all of these at your fingertips at themeasuredmom.com/episode77. I'll also include some links to some of my favorite books for vocabulary activities.

Thanks for listening and I'll talk to you again next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Do’s and don’ts for teaching vocabulary (blog post)

Bringing Words to Life, by Beck & Beck

Word Nerds, by Brenda J. Overturf

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post Whole class vocabulary activities to make those words STICK appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 24, 2022

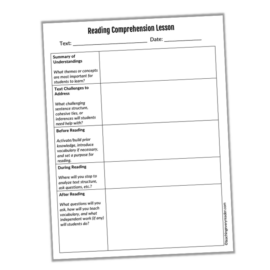

A simple template for reading comprehension lessons

TRT Podcast#76: A simple template for reading comprehension lessons

So – you’re reading an on-grade-level text with the whole class. How can you make this reading comprehension lesson interesting, engaging, and useful for ALL your students? Today’s episode will give you a simple template you can follow to make these lessons a success!

��

Listen to the episode here

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

So you have a grade level text you want your whole class to read. How can you make the most of this reading comprehension lesson? What are the before, during, and after reading activities you can do to help make this text accessible and interesting to everyone? That's what we're going to cover today!

Welcome to Triple R Teaching, where we encourage you to think differently about education by helping you reflect, refine, and recharge. This isn't just about trying something new as you educate those entrusted to your care. We'll equip you with simple strategies and practical tips that will fill your toolbox and reignite your passion for teaching. It's time to reflect, refine, and recharge with your host, Anna Geiger.

Hello, hello! Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom. Today, we're talking reading comprehension lessons, so a lesson that you are doing with your whole class, and they're reading the same text, what's the best way to go about this?

I'm going to share something with you from our online course, Teaching Every Reader, and this is based on a framework called the Berger framework. I have not been able to track down who Berger was or where the Berger framework came from, but it's something I learned about when I took The Reading Teacher's Top Ten Tools by Deb Glaser. We have adjusted this framework a little bit to make it our own, but I want you to know that this comes from the Berger framework.

This is a really useful thing to keep in mind as you're planning a whole group lesson because you don't want to go down the old path of having everyone take turns reading round robin style, and then reading a list of questions at the end. There's so much more we can do to make the text interesting and accessible.

Before you read the text with your class, make a note of the things you want your students to learn. Remember, the thing you write down should not be, "I want them to learn to make connections," or, "I want them to learn to do cause and effect." Those things are important and they can be a secondary item because they are important reading strategies, but the main thing is you want them to learn something from the text, right?

So if you want them to learn to compare and contrast, what are they comparing and contrasting? Make sure the text is worth reading. Maybe the text is the difference between frogs and toads, and that's what you want them to learn. Learning knowledge for knowledge's sake is important. Learning vocabulary for vocabulary's sake is important. That's really what you want to start with, the themes or concepts that are most important for your students to learn.

The next thing you should write down is the things in the text that may be difficult for your students. For example, a text that uses a lot of pronouns to refer to items in previous sentences can be a little hard for young or struggling readers. Maybe there are things in the text that are not explicitly stated, and students will need to make inferences. Those are things you should mark.

I'll be upfront with you, if you are brand new to this, this step is probably going to be hard. You may not have really analyzed a text this deeply before. In our course, Teaching Every Reader, we go through this quite a bit, talking about what could make a text challenging, like challenging sentence structures, cohesive ties, so that's going back to those pronouns where something is related to something else, and helping students make those connections. But as you get practice with this, you will start to notice what parts of the text may trip your students up.

Once you've made these notes for yourself, you know the things that you're going to focus on during your lesson. It's time to think about your before, during, and after reading activities. As you begin to read the text, probably with echo reading or coral reading (NOT round robin reading), make sure that you start by setting a purpose for reading. Tell your students what you want them to learn.

If necessary, address key vocabulary words. Some of them you may need to pre-teach. However, if you think that they can figure out what the words mean by context, you can wait to discuss them as they come up. You want to call attention to any of those things that are challenging such as an especially long sentence. If there's a text structure that's obvious, talk about it. Maybe it's a descriptive text. Maybe it's a text that very clearly compares and contrasts something. Maybe it's a text that addresses a problem and a solution. Call attention to the text structure. If you're reading a fiction text, you might make predictions about the plot.

Here's something else you could do. If you're reading a nonfiction text about a topic that you think your students know something about, you could make a list of the vocabulary words they might find in the text. You could have them have the text turned over and you could say, "Today, we're reading a text comparing frogs and toads. Who can give some words that we might find in this text?" and they'll probably list words like amphibian, tadpole, and so on. It's really fun for kids if you put those words up on the board where everybody can see it and then keep a tally of the words as they appear in the text. It will really keep their attention.

**Whether you're just getting started in your teaching career, or you're an experienced teacher ready to learn more about the science of reading, our online course, Teaching Every Reader, is for you. The doors open on May 16th, 2022. When you join us, you'll get access to eight video modules all about the science of reading and how to apply it to your day to day teaching. Module one is all about the big picture. Gain a solid understanding of the science of reading. Module two will help you build a solid foundation of oral language. Module three is all about phonological and phonemic awareness, and the following modules will help you teach phonics, fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary. Finally, in the final module, you'll learn how to use what you've learned to plan differentiated small group lessons. We've even got a bonus module all about teaching learners with dyslexia. To learn more, visit teachingeveryreader.com.**

If the text has text features like headings, subheadings, illustrations, or bold print, call attention to those things before they read. If you're going to be using this text to teach a reading comprehension strategy such as cause and effect or monitoring comprehension or building background or using prior knowledge, discuss that before you begin.

As you are reading the text with your students, stop at vocabulary words that may be difficult. Stop at those words you introduced before reading, or those words that you marked, but decided to have students try to figure out the meaning using context.

Note cohesive ties. If they are reading a sentence and you know that a phrase in that sentence refers to something in a previous sentence, you can stop, direct them to that cohesive tie, they can underline it, and then you can say, "This is the word 'they.' What is 'they' referring to? Oh yes, 'they' is referring to amphibians, which was in the previous sentence." If it's a text they can write in, which is always useful, have them underline that word and draw an arrow to the word that precedes it.

You could do a think-pair-share. At different points in the reading, you could stop, ask a question related to the text, have students talk about it with each other, and then take turns sharing it with the group. You can ask quick questions about the text that can be answered with a thumbs up or a thumbs down. You can stop at different points to summarize what you've read so far.

You see how this whole class reading of a text is really quite deep and thick. It's not just reading it and being done, it's stopping often to discuss it. If you have your questions and your points of discussion ready, and you're involving the students and not just calling on individual students here and there, you can keep them engaged and you can make this interesting. Not only will their comprehension in general improve, but, of course, they'll also learn some useful information.

Other things teachers like to do is have their students code the text. Maybe you choose just two or three things they could use to code. For example, a star if they think something is important, a question mark if they're confused, and an exclamation mark if it was something really interesting.

Finally, after reading, and you can see we've already done a ton of work with the text, you're going to review the vocabulary words that you taught. You're going to ask both low and high level questions. You're going to have students work to summarize the text, maybe in pairs. You could have them do a writing activity. They could complete a graphic organizer. Each child could write a quiz about the text and then switch quizzes with another student and see how they do at completing each other's quiz.

I hope that this has helped you see that a reading comprehension lesson does not have to be dry and boring. There's so much you can do to make it interesting. Inside our course, Teaching Every Reader, we actually have a three-part module all about reading comprehension, and we go through everything: a summary of the research, how to teach story structure and text structure and cohesive ties, how to teach reading comprehension strategies and keep them in the proper perspective, as well as working through a reading comprehension lesson as you've heard today.

In the show notes for this episode, themeasuredmom.com/episode76, I'm going to share with you for free the reading comprehension lesson template that is included in the course, so you can print this out and use it as you plan your own reading comprehension lessons. Thanks so much for listening, and we'll talk to you again next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

Core’s Teaching Reading Sourcebook, by Honig, Diamond & Gutlohn

The Megabook of Fluency , by Rasinksi and Cheesman Smith

Get this free lesson template!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post A simple template for reading comprehension lessons appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 23, 2022

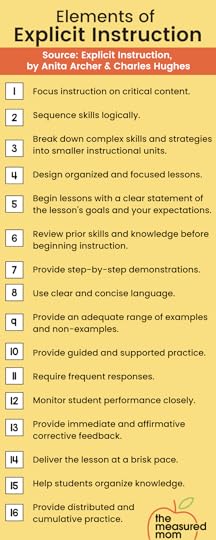

What is explicit instruction?

How do you teach students with dyslexia? With explicit instruction. But what IS explicit instruction anyway?

In their book, Anita Archer and Charles A. Hughes tell us that explicit instruction is systematic, direct, engaging, and success oriented.

If you have a few minutes, check out this helpful video from Anita Archer.

It feels a little weird to use the word explicit when talking about teaching because of the word’s negative connotation. But rest assured, in this context explicit simply means that our teaching is direct and clear.

Researchers have identified the characteristics of explicit instruction. Archer and Hughes list them in their book.

You might notice that the above list doesn’t tell you what to teach, but how to teach.

Explicit instruction is about the art of teaching.

This may frustrate you if you came to this post to learn the specifics of what to teach children with dyslexia, but we can trust Archer and Hughes on this.

Effective and efficient instruction requires that we attend to the details of instruction because the details do make a significant difference in providing quality instruction that promotes growth and success.

Anita Archer & Charles Hughes in Explicit Instruction

Let’s take a look at some practical ways to bring those sixteen elements to life.

Have your lesson materials organized and ready to go.Admittedly, this was not my forte as a classroom teacher. In fact we often had games such as “let’s find the teacher’s stapler.” I tended to leave things in piles and forget where I’d placed them.

Our time is precious – and we can maximize it by having organized systems for where we keep our materials. (As my dad would say, “A place for everything and everything in its place.”)

Use a timer to keep yourself on track.This is an excellent strategy when teaching small group phonics lessons. Set a timer for each portion of your lesson so you save time for reading connected text and doing guided writing.

Recommended:

How to give small group phonics lessons

Use routines.

As a parent of six kids, routines have saved my sanity. My kids appreciate knowing what to expect, and best of all – I don’t have to tell them what comes next because they know.

If I find myself answering the same questions a million times a day, that should clue me in: I need a routine for this.

Use routines in how you line up, hand in papers, start a lesson, get letter tiles, do word sorts … you name it.

Use the I do, We do, You do model in your lessons.a. I DO – Demonstrate the skill and describe what is being done. Unless the skill is very simple, you will need to model it multiple times. Even though you are modeling, keep your students involved. One way to do this is by having them chorally repeat words and phrases.

Anita Archer is brilliant at active participation. Watch this quick video … you’ll love it!

b. WE DO – As the authors of Explicit Instruction write, “the purpose of initial practice activities in an explicit lesson is to provide students with opportunities to become successful and confident users of the skill.” Guided practice is provided through the use of prompts.

c. YOU DO – Finally, it’s time to determine whether students can perform the task without your prompting. Provide students with several problems similar to the ones you’ve already presented in the lesson, and ask them to do them on their own.

To conclude the lesson, review what was learned and (if appropriate) assign independent work.

Be creative in how you elicit responses.It’s so easy to just do as we’ve always done … ask a question, wait for hands to go up, and call on someone.

But there are better ways to engage our students.c

a. Have students give choral responses. Ask a question, pause, and then say, “Everyone?” Teach your students that this is their cue to answer in unison.

b. Have students give partner responses.

Assign partners and pause after questions for students to discuss the answer with their partner. If the question is more open-ended, call on students to share what their partner stated.

c. Have students work in small groups.

Place students on teams and give each person a number. Their job is to work together to answer the question, making sure they all agree on the answer. Then call out a number; the student with that number must answer for the group.

d. Bring distracted students back to the lesson.

Instead of calling on someone who’s daydreaming, try one of these suggestions from Explicit Instruction:

Move closer to the disctracted student.Give a directive to the whole group. (“I need everyone’s eyes up here.”)Give the students something physical to do. (“Circle the number 1 on your paper.”)As you can see, there’s a lot to say about explicit instruction. We’ve barely scratched the surface today, but this is enough to get you started.

Remember, explicit instruction is important for everyone, and especially our students with dyslexia.

Stay tuned for then next post in our dyslexia series!The post What is explicit instruction? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 17, 2022

6 ways to build fluency

TRT Podcast#75: 6 Ways to build fluency

TRT Podcast#75: 6 Ways to build fluencyWithout fluency, our students will struggle to comprehend what they read. Here are six ways to build fluency in a variety of settings. Let me know if you try the last one!

��Listen to the episode here��Full episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and today we're going to look at six ways to build fluency.

This is a big one because, as we know, fluency is the bridge from decoding to comprehension. If students can sound out words, but they can't read them automatically, or with fluency, in terms of expression and phrasing, then comprehension is not going to occur. So what can we do to improve students' reading fluency?

Let's start with something simple, echo reading and choral reading. We're going to count these as a pair. We want to consider using echo and choral reading to replace the traditional round robin reading, where students go around the room taking turns reading aloud. Round robin reading really does not give students enough practice to develop their fluency, but echo and choral reading are research-based instructional strategies that help students transition to fluent reading.

You don't want to use echo reading with easy texts because students don't need the support with easy texts. You want to save it for challenging material, and an important thing to remember with echo reading is that you want what you're reading to be long enough that students actually have to read it as they echo, not just recite what they heard. It's good practice to gradually increase the amount of text that students must echo so they're not relying on their memory. Your goal is for them to echo your reading of several paragraphs or even a page. Remember with this activity, and any fluency activity, the goal is always reading comprehension so make sure you explain vocabulary or other confusing sections of the text.

Choral reading is another type of assisted reading activity, but it's a little harder than echo reading because you and the students are reading it simultaneously. It provides less support, but it will give them practice developing automaticity and expression. Consider starting with echo reading and then following up with choral reading.

**Mark your calendar, the doors to our online course, Teaching Every Reader, open on May 16th, 2022. When you join, you'll get lifetime access to eight video modules. You'll also get charts, resources, and dozens of low-prep student resources. Here's what one of our students had to say, "Teaching Every Reader is well organized and very informative. Each module is thorough and delivered in a concise, clear manner. I'm so glad to have unlimited access to the modules. They will be a great reference in the months and years to come." To learn more, visit teachingeveryreader.com.**

Our second strategy for fluency building is partner reading. That is, of course, when students read in pairs to each other. In partner reading one student is the reader and the other is the listener or supporter. Students should alternate reading paragraphs or pages, and if they're reading a play, they should alternate roles. The reader's job is to read clearly and with expression, and the listener's job is to follow along, help with misread words, and offer encouragement.

You want to make sure before having your students do partner reading that you do a LOT of practice of appropriate behaviors so this doesn't become a difficult time for you. These may include using quiet voices while you read, talking only to your partner, talking only about your reading, sitting side by side using EEKK (elbow to elbow, knee to knee), holding the text so both of you can see it, waiting a few seconds before jumping into help, using kind words when correcting mispronunciations, and doing your best.

Partner reading is a great center idea when you're teaching small groups, but when possible you could have the whole class doing buddy reading so you can circulate and give support. As you move around the room, you can help partners monitor their volume, stay on task, resolve disputes, and support each other. It's probably actually a really good idea to do whole class partner reading before you introduce it at a center.

As for how you should form partnerships, people have different ideas about this. One recommended way is to rank your readers from highest to lowest, list them in that order, and split the list in half and then match the first person on each list with the first person on the other and so on. Of course, this would be a private list, you would not share it with your students. So in a class of twenty four children, the top reader would be matched with the reader who was ranked thirteen.

Now, personally, I think if you can get it to work, it's nice to match students who are similar in reading ability, unless they're both really, really low in which case they'd have a hard time supporting each other. But I think that can be useful, particularly with kids kind of in the middle. But there are certainly different things that you could try and you could certainly have flexible pairings.

Next, we have reader's theater. You're probably familiar with that. That's an authentic way to get students to reread a text and therefore build fluency. The fun thing about reader's theater is that it combines reading and performance. You provide a script for your students, they practice it multiple times, and then they perform it, whether it's just for their classmates or for maybe parents who come to visit or school staff. Some teachers like to do a whole week of reader's theater. That might be what they do during their fluency building time, and then the next week they might do something different. That could be a good thing to make it something to look forward to and not something they get tired of.

As for where to find scripts, you can find free ones online - not too many, but there are some. You could also take a favorite book and type the lines into parts yourself, creating your own script. I have a set of these in my shop. Just today someone left a comment that she used it with children who were in an after school reading program for third grade and they really enjoyed it. These were kids who probably are struggling readers, and they thought they were really fun.

The next strategy for building fluency is often something that teachers do with the whole class, but from all the things I've read, it's really best for children who need a fluency intervention, and it's not particularly useful with everyone else. What this is is timed, repeated reading. So you have a child read for one minute and try to beat their rate and accuracy with successive one minute readings of the same text. It's less authentic than other repeated reading activities, but it is effective for children who need this extra help.

In their book, the Teaching Reading Sourcebook, which I highly recommend, Honig, Diamond, and Gutlohn tell us that research has shown that timed repeated reading is best used as "an intervention strategy most appropriate for slow, but accurate readers who need intense practice to increase their automaticity in reading connected text". So, in other words, avoid doing this with your whole class all the time, but instead, save it for struggling readers who are accurate, but disfluent.

Again, you're going to have a passage, probably 100-250 words, and you're going to tell the student they're going to read the same passage over and over until they read it fluently at a certain rate. Let them know you're going to use a chart to graph their performance so they can see how they improve. You'll preview the passage together, set a timer for one minute, listen to them read, and keep track of their errors.

Now, this is important. After the first reading, you need to give positive feedback and then corrective feedback. You don't just have them read and then set the timer and read again. You want to talk about what they did well, and then look at those words they got wrong or that tripped them up, and help them with those words so that next time they have a better chance of reading them correctly. You might need to model expressive reading, and then you're going to calculate their oral reading fluency score plotted on a graph and set a goal. For instance, by Friday, we want to read this passage with this number of words correct per minute.

Let's move on to a strategy that you can use with the whole class. This is called FORI, and I cannot remember what those letters stand for! I'm assuming F stands for fluency. But FORI is something that you can do with students probably toward the end of first grade, second grade, and on.

It's a whole group approach for building fluency that was originally developed for a district that had mandated that all the kids had to be taught exclusively with grade level texts, which is a little scary for a teacher who knows their kids are at all different levels. So they had to use a lot of scaffolding, which is temporary support in their lessons, and their two year experiment with FORI was successful and their students reading levels went up.

You can use FORI with any reading program. There's good research evidence of effectiveness with early elementary kids, and it's been successfully used with English language learners. This is something I learned about from the CORE "Teaching Reading Sourcebook," which I mentioned just a few minutes ago.

It uses challenging material to expose students to a variety of concepts, vocabulary, and ideas that they would not get access to if they were only reading texts at their instructional level. The benefit of this approach is that it not only builds fluency, but it also builds comprehension and vocabulary by supporting students so they can access texts they could not access on their own.

The first day you introduce the text and read it to the class while they follow along. Then you lead a discussion to make sure the focus is on comprehension. At home, they do their own reading for twenty or thirty minutes.

The next day you echo read. You read a section, then they read a section, and remember with echo reading, it's not recitation, it's making the section long enough that they actually have to read it, not recite. Again, the teacher continues to include comprehension in the discussion. That night, students read the text to a family member, so it's not their choice anymore, it's this one.

On Wednesday, the third day, the teacher and the students choral read the selection. So echo reading was a little easier, and choral reading is harder because they don't have the teacher modeling first. Students who need extra practice read the same text at home, but others may choose their own text.

On Thursday, they do partner reading of the same passage, and, according to this model, they get to choose their partner, and they typically alternate pages. That night, students who need extra practice read the same text, but others may read a book of their choice.

On Friday, all the kids do extension activities that lead to greater comprehension of the text. That could include a discussion, some kind of written response, filling out a graphic organizer, you get the idea. That night everyone reads on their own, their choice of text.

Your goal is that everybody in the class will be able to read the grade level text independently by the end of the week. That's FORI.

If you head to the show notes after this episode, you can print the transcript of this episode and that way you can have all this written down so you don't forget the steps for each day.

Finally, I would like to talk to you about another whole class fluency builder, and that is a fluency development lesson.

In the 90s, Timothy Rasinski, who's big in fluency, he and his colleagues studied the effectiveness of the fluency development lesson (FDL), and they found that students who participated made significant gains in their reading rate compared to the kids in the control group. The FDL was developed to assist students experiencing difficulties in fluency and in learning to read. Unlike FORI, the fluency development lesson is appropriate for younger readers AND more experienced ones. It's also, I think, something any teacher could incorporate because it's much quicker than FORI because you're using a very short passage.

You choose a text that's just 50-150 words, it could be poems, it could even be predictable text. That's fine. Choose an engaging text that's ideal for performing orally. You're really working on prosody here, expression. You make sure that every child has their own copy of the text, so it's not just you reading a big book, they all need their own copy. You read it a few times to provide a model of fluent reading and students follow along. Then you take about two or three minutes to talk about the meaning of the text.

Have you noticed that consistently here, we want to make sure that we're focusing on MEANING and not just reading words off the page. During that little discussion the teacher could address any challenging concepts or vocabulary. Then the teacher leads the class in several choral readings. You might mix things up by reading in a silly voice different times. Since it's just a short passage, that shouldn't be a problem. Again, students read the text in pairs, then they come back as a group. Volunteers might read it out loud. They take it home to read to a family member, and now this is their text and they can put it in their reading bag for their independent work and practice it.

So you can see how the fluency development lesson is sort of a mini FORI, sort of. It's really, really short, but you do a lot of the same steps, so it's great for older and younger kids. The lessons are fast and it requires very little prep on your part which is awesome.

So, wow, I really hope that all the things I shared with you today have filled your toolbox and given you some exciting things to try when it comes to building fluency with your students.

Let's go ahead and do a quick review. First, we talked about echo and choral reading. So echo reading is when kids echo your reading, but again, it's long enough text that they're not reciting, they're actually reading. Choral is when they're reading together with you.

Then we talked about partner reading, where they read as buddies, in pairs.

We talked about reader's theater, which is similar to partner reading, but it's more of a small group and they're going to perform for a class or for visitors to the classroom.

We talked about timed repeated readings, which are really most appropriate for our students who are reading accurately, but at a slow rate. It's best as an intervention strategy and not something you do with everyone all the time.

FORI, F-O-R-I, is really good if you're trying to get everybody to have plenty of practice reading grade level text.

Finally, the fluency development lesson is good for kids of all ages and you only need a small reading passage, and it's kind of an intense attention on that text for a day.

Head to the show notes to download and print the transcript so you don't have to remember all of these. You can find the show notes at themeasuredmom.com/episode75. We'll talk to you again next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resourcesCore’s Teaching Reading Sourcebook, by Honig, Diamond & Gutlohn The Megabook of Fluency , by Rasinksi and Cheesman Smith

Reader’s Theater Scripts – Familiar Tales for Grades 1-3

$12.00

These ten scripts are easy to prepare and fun to perform!

Buy Now

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every ReaderJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post 6 ways to build fluency appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 10, 2022

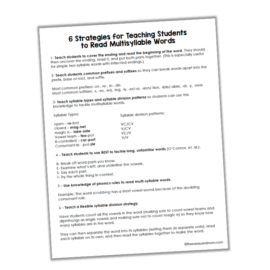

6 strategies for reading multisyllable words

TRT Podcast#74: 6 strategies for reading multisyllable words

TRT Podcast#74: 6 strategies for reading multisyllable wordsDo you have students who struggle to read longer words? These six strategies will give you the tools you need to help. #4 is my favorite!

Listen to the episode here Full episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here and welcome to the Triple R Teaching podcast, Episode 74. Today we're going to look at six strategies for teaching students to read multisyllable words.

The first strategy is one you're likely already doing, and that's to encourage your students to find the short words in longer words. This is really helpful particularly for beginning readers who are just starting to read longer words, words that might have an -ed or -ing ending. Have them find the chunk they know and then add the ending.

For example, in the word "playing," they would find the word "play" and then add the ending -ing.

This can also work with words with the consonant-le ending. For example, in the word "bottle," the child can read the "bot" at the beginning and then add the ending.

The next thing we should do is make sure that we introduce our students to common affixes - prefixes and suffixes - early on. So this should begin in about second grade, even earlier if students are ready for it. Interestingly, you don't need to teach a ton of prefixes and suffixes for this to help. A study in 1989 found that 58% of all words with prefixes were accounted for with the prefixes un-, re-, in-, and dis-. Among suffixes, the inflections on verbs, -ing and -ed, and nouns, -s and -es, accounted for more than 60% of word endings.

I'll include notes on this in the show notes, but the point is that you don't need to have a huge list of prefixes and suffixes to teach in order for it to make a big difference when your students tackle multisyllable words.

Our next strategy for teaching students to read multisyllable words is actually a little bit controversial in science of reading circles.

**What if you could get a solid understanding of the research without spending hours reading dry professional journals? What if you knew how to pinpoint each student's instructional needs and make a do-able plan for moving forward? What if you could find a solid system for teaching phonemic awareness, phonics, and vocabulary? What if you could be confident that your students had exactly what they need to grow in fluency and achieve the ultimate goal, strong reading comprehension? What if you had the resources you need to plan engaging whole class lessons and efficient, targeted small group instruction? What you want is within your reach and it's all within our online course, Teaching Every Reader. The doors open to the public on May 16th, 2022, mark your calendar and visit teachingeveryreader.com to learn more.**

The controversial technique is teaching students syllable division and syllable types. I think the reason that it gets so much flack from some people is that it can be time-consuming. Interestingly, in her book, Teaching Word Recognition, Rolanda O'Connor tells us that we actually don't have to spend a ton of time teaching these types of things to older, struggling readers. She often talks about how it only takes maybe a month or so of intervention in these particular strategies, perhaps only a total of five hours, and it can make a really big difference in students' reading. So just keep that in mind, as I talk to you about some of these things that we can consider.

Teaching syllable types means helping kids understand that there are six (or seven, depending on how you count) different types of syllables.

The closed syllable has a short vowel sound because it ends with a single consonant following that single short vowel. For example, the word "can" is a closed syllable. In the word "kitten," both syllables are closed. Now you might notice that in the second part of the word, "ten," doesn't actually say "ten." It says "tin." That's because it has the schwa in it, but that doesn't change the fact that that is a closed syllable.

Then we have open syllables that end with a long vowel. So the word "hi," as in, "Hi, how are you?" or "go." Those are open syllable words. Then we can put them into longer words like the word "robot." The first syllable "ro" is open. The second syllable "bot" is closed. Those are the two basic ones that I think we can teach to really young kids.

Then we go on to others like the magic E syllable, vowel team, diphthong (which is sometimes included with vowel team), bossy R, and consonant-le. Knowing the syllable types and having practice with them can really help kids as they solve multisyllable words.

Kind of alongside that are pretty intense, in my opinion, syllable division strategies, where you teach students how to examine a word, find the vowels, locate the consonants between, divide the word according to a pattern such as VC, CV, or V/CV or VC/V or V/V. Those are the four main ones.

It's quite a process to teach these to students, help them analyze the word by finding the consonants and vowels, dividing appropriately, labeling each syllable type, and then slowly sounding out the word. This is a very big part of many Orton Gillingham based reading programs.

I think there's value in this in helping students study and analyze words, but I think it is, in my opinion, a little unrealistic to think that when a child gets to a word they don't know they're going to actually label all the parts and divide it up. I just don't really see that happening. However, just this practice of analyzing long words can be useful.

My concern, as I mentioned in a previous episode, is that it takes a long time and I wouldn't want to see a ton of time spent on this each week, because really what we're really going for is practice with connected text. If we're going to spend fifteen minutes, multiple times a week, on syllable division, I just don't think that's a really useful use of our time. Now that's my opinion. I personally do believe that teaching syllable types is useful, but again, we've got to keep our end goal in mind here.

Our fourth strategy is from Rolanda E. O'Connor in Teaching Word Recognition, which is such a great book. I'm sure I've mentioned that before, but it's definitely worth purchasing. She has a technique called BEST. That's the acronym and it's good for elementary students.

To teach the strategy you present the acronym BEST and you help your students understand what each letter stands for. B stands for break off the word parts you know, so that could be breaking off a prefix or a suffix. E is for examine what's left and underline the vowels. Underlining the vowels can help you see where the syllables occur. S is for say each part, and T is try the whole thing in context.

In her book, she tells us that memorizing the acronym and the actions will take a few minutes the first day and less time as they get more practice with it. When you do the first step, breaking the word apart, that requires them to know prefixes and suffixes, so you want to make sure you've taught those and also identifying the base word within a longer word. Then as they underline those vowels in the rest of the word, that can help them chunk it out.

In her research, O'Connor found that kids with reading disabilities understood this after four or five days of instruction, with just five minutes each day, but it took about two weeks before they found the students challenging each other to BEST a long word they encountered in their reading. That's really cool to find out they actually applied this. I would say this is much easier to apply on the run than a long syllable division type strategy. She suggested that teachers should use this strategy with their students for a few minutes daily for at least three weeks before expecting it to make a difference.

Strategy number five is to have students use their understanding of basic phonics rules to decode longer words. One quick example, if a word has a double consonant in the middle, it usually means the vowel preceding it is short. So in the word "scrubbing," it wouldn't be "scroob-ing," it would be "scrubbing" because that double consonant alerts us to that. We know because when you have a word with a single short vowel and a final consonant, and you're adding -ing, the general rule is that you double that final consonant. That's just one example, but knowing these basic phonics rules can help students as they analyze parts of words.

Finally, the last strategy we're going to talk about today, our sixth and final one, is having a flexible syllable division strategy based on finding the vowels. I'm going to include a video in the show notes for this episode from Reading Rockets with Linda Farrell, I just love her. She has a video where she's working with a boy and she's helping him decode longer words by first finding the vowels, and then pulling down the chunks, the syllables of each word, using those vowels as a guide, and then reading those syllables and putting them together. It's flexible because we're not worried so much about syllable division rules. We're just mainly looking for vowels, dividing the word into syllables, which may not be a hundred percent correct, but it will probably be good enough for reading the word.

This strategy is flexible. It's definitely not as exact as the syllable division strategies I mentioned earlier, and it's certainly up for debate as to which is better, but I think it's good to have all of these up your sleeve.

Today in the show notes, I'm going to make sure to give you a PDF that lists all of these strategies. You can have them at your fingertips as a reference when you're helping your students learn to decode multisyllable words. You can find that at themeasuredmom.com/episode74. Thanks for listening. I'll talk to you again next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Get this free cheat sheet!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

Related resources Teaching Word Recognition, by Rollanda E. O’Connor Six Syllable Types – Reading Rockets Reading Multisyllable Words video with Linda Farrell and Xavier (third grader)Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every ReaderJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post 6 strategies for reading multisyllable words appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 8, 2022

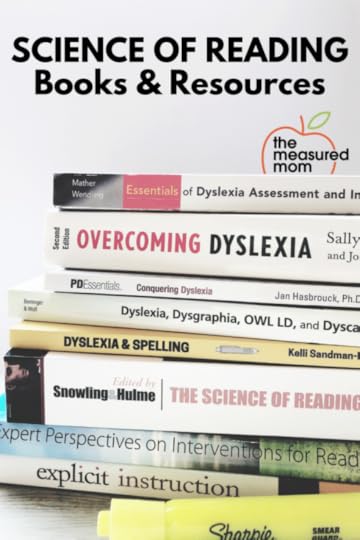

Recommended Science of Reading books

The science of reading is the body of research that has been conducted on how we learn to read and write. This research has been conducted over decades, but only recently has much of it been introduced to today’s classroom teachers.

It’s important to note that as more research is conducted, we may need to revise our previous understandings. In addition, there is disagreement when it comes to translational science: how to apply this science to day-to-day teaching.

I say this to let you know that while I recommend all of these books, the authors do not agree with each other on all points.

Enjoy studying them for yourself!

*This list will continue to grow as I complete particular books. While I have read portions of countless books, I am choosing to include only the books I have read in their entirety.

I hope you will share this post with others on their science of reading journey!

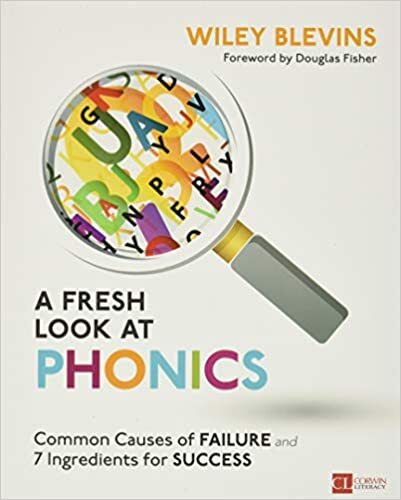

A Fresh Look at Phonics

Wiley Blevins

I recommend Blevins’ books every chance I get, and when I see he’s published a new one I buy it immediately. They are all easy to read and incredibly practical – yet still building on the science of reading. In this book WIley uses the data he’s collected to show which phonics approaches really work. Learn activities, routines, and lesson formats that will make your phonics lessons both engaging and powerful.

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

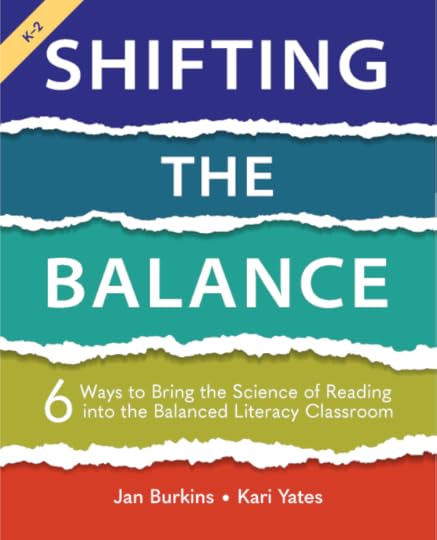

Shifting the Balance

Jan Burkins & Kari Yates

This is the book for balanced literacy teachers who want to learn about the science of reading. Burkins and Yates tell encourage them to can begin their science of reading journey by making six shifts in how they approach beginning reading instruction.

For those passionate about the science of reading, this book will be too simple and not go far enough. But for those starting out, it’s the ideal first step.

Anna’s overall rating

easy to read

easy to apply

Conquering Dyslexia

Jan Hasbrouck, Ph.D.

As both an experienced researcher and the mother of a daughter with severe dyslexia, Hasbrouck writes in a relatable and practical way. She writes about the signs of dyslexia, how to get a diagnosis, and how to teach students with dyslexia. I find myself referring to this book again and again … such an accessible read!

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

Phonics from A to Z

Wiley Blevins

True story: I jumped out of my seat when reading this book because my website is referenced on page 40 (just to mention my big list of alphabet books, but still). This is a book you’ll reference over and over because it includes word lists, powerful instructional routines, and sections about teaching phonics to struggling readers and English learners. It’s a classic that every reading teacher should own!

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

Dyslexia Advocate!

Kelli Sandman-Hurley

This book will tell you exactly what to do if you suspect your child or student has dyslexia. You’ll learn how to apply the IDEA (Individual with Disabilities Education Act), how to prepare for an IEP meeting, and a whole lot more. A must-own for teachers and parents of children with dyslexia!

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

Teaching Reading Sourcebook

Bill Honig, Linda Diamond, Linda Gutlohn

Not only does this book give you the big picture of teaching reading (with research to back it up), it also breaks down print awareness, letter knowledge, phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, comprehension, vocabulary and more.

I love the practical examples and the easy-to-read format. Don’t let the price tag scare you – it’s worth every penny.

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

Making Sense of Phonics

Isabel L. Beck & Mark E. Beck

I say this a lot, but this book really is a must-read (and must-own!). From the back cover: “This bestselling book provides indispensable tools and strategies for explicit, systematic phonics instruction in K-3. This volume is packed with engaging activities, many specific examples, and research-based explanations.”

It’s been a few years since I read it; paging through it makes me eager to read it again!

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

Sally Shaywitz, M.D.

This is considered THE book on dyslexia, and it should be studied by anyone who wants to become an expert in this area. Be prepared: the book is fat and extremely comprehensive. The authors cover everything – from screening for dyslexia and possibly getting a diagnosis, to how to help people with dyslexia succeed in college and beyond.

I find the book most helpful in understanding dyslexia; while it does include several chapters about teaching readers with dyslexia, I didn’t find that section particularly useful.

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

Teaching Word Recognition

Rollanda E. O’Connor

If you teach struggling readers, this book is a MUST-READ. The layout isn’t particuarly eye-catching, but once you get started you won’t be able to put it down. O’Connor’s book includes brilliant strategies for helping kids remember letters of the alphabet, learn to decode, and sound out multi-syllable words. It’s another one I want to take the time to re-read.

A treasure for sure!

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

Choosing and Using Decodable Texts

Wiley Blevins

If you’re making the switch from leveled to decodable books (or just want to do a better job of teaching with decodables), THIS is the book you need. In his trademark style, Blevins presents useful information in a conversational format with lots of helpful examples so you’re immediately ready to apply what you learned. Learn how to choose decodable books and how to develop before, during and after routines to make the most of them.

Anna’s overall rating

Easy to read

Easy to apply

The post Recommended Science of Reading books appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 4, 2022

Signs of dyslexia

Today, in the third post of our dyslexia blog series, we’re uncovering the signs of dyslexia.

So far we’ve addressed dyslexia myths and defined exactly what dyslexia is.

Read also

Busting 12 dyslexia myths

Here’s a quick refresher:

Dyslexia is a the most common learning disability. It is “characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result form a deficit in the phonological component of language is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction.” (Source: Conquering Dyslexia, by Jan Hasbrouck)

(For more about what dyslexia is and isn’t, check out This Reading Mama’s post: What is dyslexia?)

Signs of dyslexia(Sources: Overcoming Dyslexia, by Sally Shaywitz, Dyslexia 101, by Marianne Sutherland, and Conquering Dyslexia, by Jan Hasbrouck)

It is not a single sign that alerts us to the possibility of dyslexia; it’s the combination of multiple signs. Later in this series we’ll help you understand what to do if you suspect dyslexia.

Another important note is that the specific signs of dyslexia will vary according to the age and educational level of that person.

Clues to dyslexia in preschoolers

Trouble learning common nursery rhymesDelayed speechDifficulty rhymingMay have trouble learning the alphabet, letters, colors, etc.Mispronouncing familiar words (persistent baby talk)Difficulty in learning and remembering names of letters and numbersFailure to know the letters in one’s nameClues to dyslexia in kindergartners and first graders

Failure to understand that words come apart (not able to break words apart into syllables (cowboy to cow-boy) or phonemes (cat to /k/ /a/ /t/)Inability to remember letter-sound associations (b represents /b/)Reading errors that show no connection to the sounds of the letters (pig may be read as goat)Inability to sound out even simple CVC words (big, dog, cat)Complains about how hard reading is History of reading problems in parents or siblingsClues to dyslexia in second grade through high school

Mispronunciation of long, unfamiliar, or complicated wordsGeneral reluctance to read or writePersistent letter and number reversalsSpeech that is not fluent – pausing or hesitating often when speakingUsing imprecise language (“stuff” or “things” instead of the name of the object)Not being able to find the exact word, such as confusing words that sound alike (such as saying tornado instead of volcano)Needing time to come up with a verbal response quicklyDifficulty in remembering isolated pieces of verbal informationVery slow progress in acquiring reading skillsLack of a strategy for reading new wordsTrouble reading unknown words that must be sounded outInability to read small function words (that, in, of)Stumbling on multisyllable wordsOmitting parts of words when readingFear of reading out loudOral reading full of substitutions, omissions, and mispronunciationsChoppy, labored oral reading that lacks inflectionBetter able to understand words in context rather than in isolationInability to finish tests on timeVery poor spellingTrouble reading mathematics word problemsMessy handwriting Extreme difficulty learning foreign languagesLack of enjoyment in readingAvoidance behaviors (often complaining of a headache or upset stomach in relation to school work)History of reading, spelling, and foreign-language learning problems among family membersIf you suspect dyslexia, don’t despair! Children with dyslexia CAN learn to read … and to enjoy it! In addition, people with dyslexia often display strengths such as the following. (Source: Overcoming Dyslexia, by Sally Shaywitz)

Curiosity and a strong imaginationAbility to figure things outA good understanding of new conceptsTalent at building modelsExcellent thinking skillsAbility to get the “big picture”A high level of understanding of what is read to him/herExcellence in areas not dependent on reading or in more conceptual subjectsOften especially emphatheticI’d like to conclude with a quote from a parent of a child with dyslexia, as quoted in Overcoming Dyslexia, by Sally Shaywitz.

Don’t be afraid of a dyslexia diagnosis. Become empathetic, learn about it, do the best you can to help your kid understand, also, that they’re going to be fine. This isn’t the end of the world. Not only is it not the end of the world, it’s a great opportunity (for your child to learn to advocate for him/herself).

Parent of a child with dyslexia

The post Signs of dyslexia appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 2, 2022

5 Ways to build the alphabetic principle

TRT Podcast#73: 5 ways to build the alphabetic principle

The alphabetic principle is the understanding that printed letters represent sounds – it sounds simple, but not all kids grasp this concept. Without it, they can’t learn to read! Here are five simple ways to build the alphabetic principle.

Listen to the episode here

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and welcome to Episode 73 of Triple R Teaching, where we're going to look at five ways to build the alphabetic principle.

The alphabetic principle is this idea that print is a code for sounds. In other words, we use graphemes to represent phonemes, a letter or group of letters to represent a single sound. For example, the letter D represents the sound /d/. The letter F represents the sound /f/. The alphabetic principle is something that we as teachers might take for granted, but as it turns out, a lot of our students don't acquire this as naturally as we might think.

Becky Spence, who is the creator of This Reading Mama and the co-author of my online course Teaching Every Reader, wrote this on her website,

"I'm telling you when I began to truly understand the alphabetic principle, it absolutely blew my mind. I'm sure I'd heard the phrase before, and I'm sure I'd even learned what it meant, but when I actually understood its role in teaching beginning readers and helping struggling readers, it all became very clear. I'd always thought that if learners had two important skills, they were good to go as readers and spellers: phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter sounds. But guess what? It's not enough. If learners don't also have a strong understanding of the alphabetic principle, they're missing a big piece to the puzzle when it comes to reading and spelling."

A great definition of the alphabetic principle comes from Rollanda E. O'Connor in her fantastic book, Teaching Word Recognition, and she writes, "The alphabetic principle can be understood in this way. Any word that we say can be broken into speech sounds. Any speech sound can be represented with a letter or collection of letters from the alphabet." Also in her book, O'Connor reminds us that the alphabetic principle should be established as early as possible, definitely by the end of kindergarten.

So how do we do that? How do we make sure that our students have the alphabetic principle? Today I want to share five things that you can do.

**If you're listening in real time, mark your calendar for May 16th, 2022, when we open the doors to our online course, Teaching Every Reader, our comprehensive training for K-2 educators. If you're passionate about growing engaged, proficient readers, but every year you have a few students who just don't get it, Teaching Every Reader is for you. Imagine having the knowledge and tools you need to meet the varied needs of all your learners. When you join us, you'll get lifetime access to the course, which includes eight video modules of practical video trainings with printable transcripts, charts and reference sheets, printable assessment forms, and dozens and dozens of low-prep student activities. To learn more, visit teachingeveryreader.com.**

Number one, when you introduce letters of the alphabet, consider starting with the letter's sound. Now I'm actually not of the camp that says we should start only with letter sounds and wait to learn letter names. Instead, I think we should teach them together, but consider starting with the sound.

Here's what I mean. Instead of saying, "This is the letter S and it says /s/," consider starting with the sound itself.

So you could say something like this, "Today, we're going to learn how to spell the sound /s/. Watch me as I make the sound /s/. Let me hear you make that sound, /s/. What is your mouth doing? Yes, your tongue is up by the roof of your mouth. One way we spell the sound /s/ is with the letter S." Then I would display the letter S on a card, and I would say, "The letter S represents /s/. S is the letter, /s/ is the sound."

Something else you can do to build the alphabetic principle is to include letters as much as possible, even in phonological awareness activities. So we're learning that we shouldn't spend a ton of time on phonological sensitivity skills - like rhyming syllables and onset/rime - once kids get to kindergarten, but I still think there's value there, especially in preschool.

Let's say I'm teaching children in preschool to break words apart into their onset and rime. Remember that the onset is the part of the word right before the first vowel, and then the rime is the rest of the word, and this is in one-syllable words. So in the word "milk," the onset is /m/ and the rime is /ilk/. And by the way, rime in this case is spelled R-I-M-E.

If I'm doing this with my preschoolers, I'm teaching them to break the word apart into the onset and the rime, I can represent each of those parts with a block. Once we've done this a lot of times and they understand the process, I could say, "Can you break the word "sack" into two parts?" You would have them push one block forward for /s/ and one block forward for /ack/, and then since I've already taught them, that S says /s/, I could remove that first block and put an S in its place. Then we could point to the letter and the second block and say the word again, "sack," "sack."

Something else you can do, even with very young learners, is have them build words using letter tiles. This is something that Marnie Ginsberg from Reading Simplified talks about a lot. I'll link to her video about this in the show notes. What you would do is you would have letter tiles for a three letter word, a CVC word, and you would help the child spell the word by first breaking it apart, and then pulling down the tiles and putting them in the proper order. Marnie recommends not calling those tiles by their letter names, but referring to them by their sounds.

For example, if I had the letters S-A-T and I mixed them up, I would say, "Today, we're going to spell the word "sat." What's the first sound? /s/." Then I would say, "Okay, where's the /s/?" Instead of saying where's the S, I could say where's the /s/, snd they would pull down the S, and if not, I would show them which one they needed. "Okay. What's the middle sound? /��/. Yes. Pull down the, /��/" and they would pull down the A. Then finally, "What's the final sound? /t/. Yes, pull down the /t/," and they would pull down the T. Then you could read the word with them.

As students start to do writing, we move on to tip number four, which is to encourage students to use invented spelling. This simply means that you encourage them to spell words as best they can using the phonics knowledge they have, even though their phonics knowledge is incomplete. So a preschooler may write the word hat with an H and a T, because they don't necessarily understand how to break it apart into all of its sounds. Or they might spell the word "is" as I-Z because they don't know yet that the word "is" uses an S to represent /z/. This is all actually very useful.

In her book, Teaching Word Recognition, O'Connor tells us this,

"Invented spelling requires children to devote conscious attention to how they might represent the sounds in words logically, even when they have not been taught particular spelling and written word pairings. The logic children use to invent spellings for words is an internal and temporary logic, which can be replaced over time as they become more aware of the letter sound possibilities in their language."

Of course, over time, invented spelling is slowly replaced by conventional spelling.

Finally, my last tip for you is to help your students develop the alphabetic principle by practicing segment to spell, even in preschool. What I like to do for segment to spell is actually count the sounds in the word first and draw a small line for each sound, so we can represent each sound in each blank.

For example, if we're spelling the word "pig," I would say, "Today, we're going to spell the word 'pig.' Let's break it apart and count the sounds. /p/ /��/ /g/. How many? Three sounds, so let's draw three blanks."

Something else you could do if you think this would be fun for your students is to put down three sticky notes, then on each sticky note, they'll write the spelling for the sound. So let's say we're using the sticky notes, I could say, "On the first sticky note, we're going to spell the sound /p/. What letter represents /p/?" Or you could say what letter says /p/, even though that's not technically correct, but I don't think it's a big deal. All right, so then they would write a P on the line. Then for the second one, "What is the second sound in the word pig? That's right /��/, what letter represents, /��/? Yes an I, let's put an I on the middle sticky," and so on.