Anna Geiger's Blog, page 21

March 22, 2022

How to keep the rest of your class learning as you meet with small groups

TRT Podcast#72: How to keep the rest of the class learning while you meet with small groups

Keep the rest of the class busy AND learning with these easy-prep, effective literacy center ideas!

Listen to the episode here Full episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, welcome to episode 72! We're going to talk about what the rest of your students are doing while you're meeting with your small groups.

Last week we talked about why I think it's so powerful to meet with small groups for phonics lessons versus teaching that skill to the whole class and how you can differentiate within those lessons. I talked about how to form and schedule the meetings with those groups and what to do when you're meeting with them.

That's all really good and really valuable, BUT if you have students over here who are misbehaving, who are noisy, or who are off task, your small groups are not going to go well, so we really need to nail down what the rest of the class is doing.

I want to give you five ideas for literacy centers, these are literacy centers that I think are powerful and not just busy work. You will teach your students how to do the activities at each of these centers, and then when that's all in place, you can start your small group phonics lessons.

Number one: your students should be doing some kind of word work. I think a really good thing to do is have a center or two that is focused on having them read the words that have the pattern that you've taught. These can be word lists, words within a game and so on.

I've recently created a bunch of games that would fit for this center. We've got "Roll & Read" where students roll a die and then read that column.

Then we have "Follow the Path," where students roll a die to move along a board. When they land on a gumball, they read a card. When they land on a space, they read just one word, but the gumball card is four or five words for extra practice.

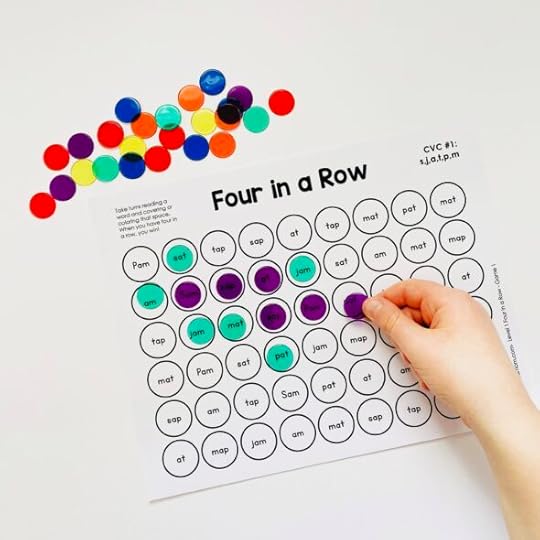

We also have "Four in a Row" where we've got all the words on a grid and students take turns reading a word and covering it, and trying to be the first to get four in a row.

We even have a Buddy Spelling Game, which helps students practice encoding the words that you've taught in their phonics lessons. It is a partner game, of course, where students read the word to their partner when they land on a certain numbered space, they practice spelling it, and then they check their spelling.

These are all great ideas for word work phonics centers. What you want to make sure is that the games you use are pretty consistent from week to week in terms of format. Because when you do that, you save yourself a ton of time from kids coming up and asking, "I don't know how to play this. What do we do again?" or arguing about how to play. When they consistently recognize the format of the game, they can get started right away and use their time really well. So that's one center, word work or phonics centers.

Another center, I think, should be independent reading where they are practicing reading texts with the phonics patterns that you've taught them. I personally have always liked when kids have a gallon size plastic bag with their name on it, but if you have room, you could have actual book bins. The nice thing about the gallon bags is they fit into a milk crate standing up. You could have them grab their bag, pull out their books, and they practice reading them independently - probably out loud if they're very young.

You could get those PVC pipe whisper phones that they can hold up to their ear. That way they can read very quietly, but actually hear it amplified in their ear. It's less disturbing to others and allows them to be able to hear the words and kind of block out the other noise at the centers.

In terms of how to fill those bags, I recommend including the books that you've finished with them in your small group phonics centers, the decodable books, as well as books that have the patterns you've taught them, but they may not have seen yet.

So let's say you're teaching CVCE words. You could still have some review books in there that have CVC words, or once they're solid with CVCE, other books that have the CVCE pattern that you've printed from offline or that you've purchased.

Then you'll have some students who are ready for leveled books, and they won't necessarily need a bag full of decodable books. That's up to you and your discretion in terms of what each particular child is ready to handle. If kids are still going to the picture to try to solve words, they're not ready for leveled books. However, if their phonics knowledge is pretty good, they're able to figure out words using their phonics knowledge as their first go-to versus going to the picture or context, then they're likely ready for other types of books. But I think it's valuable to review and practice those decodable books you've used in your lessons.

Another center that I think is a great idea is a listening center. You can set them up with books they can listen to on an iPad or another device using earpods or headphones, and you might also have some kind of response. So you might have a picture response, where for each book they listen to they draw a picture. If they're ready, maybe a simple graphic organizer, like the most important information or the beginning, middle, end, or problem and solution.

Another good center to have is a buddy reading center. Here students are working together, and they can each read a page or they can each read a paragraph depending on how long their books are. At the buddy reading center, you're going to have them practice reading decodable text, if you think that's a good idea for these particular students, or you could have copies of poems you've read for shared reading, or you could have partner plays, or readers theater.

Personally, I prefer to have buddy reading students be pretty close to the same level, so that they're actually each being challenged and not having someone who's way advanced tutoring someone who's really struggling, but if you think that's a good choice for a particular week, you could do that.

Finally, it's a good idea to have a center where students practice reading high frequency words, so that when you've taught your high frequency words in your small groups, now you have a place for that particular group to find their material.

I didn't mention this yet, but I recommend color coding your groups and color coding their materials at the center in colored file folders or some other way of color coding. So if you've got your lowest group and let's say it's the green group, then over at the centers, they know that their buddy reading material is in the green folder. They know that their phonics games are in the green folder, their high frequency word flashcards again are in a green folder or a bag with a green sticker on it. You want it to be very, very clear for them where their materials are. It also makes it easier for you.

So in terms of things they could do at the high frequency word center, they could quiz each other there with flashcards and time them to see how long it took them to read the words, and they could maybe keep track from week to week. You could have them play a game that you've created from an editable game that you've purchased somewhere, where you can just type in the words that they've learned so far, and they just practice reading them over and over in the game. You might have phrases on cards that include the high frequency word for them to practice reading. Those are all things that you can do to help your students learn their high frequency words.

Let's review quickly the five centers that we talked about today. Number one, I think, is really one of the most important, and that's your phonics or word work centers where you're going to have them practice applying the phonics skills you've taught in your small groups.

Right up there as a really important center would be independent reading, where you have them each have a gallon size plastic bag filled with books that they're able to read on their own and that they practice reading during that center.

You could also have buddy reading where students practice reading decodable text or partner plays, readers theater, poems, and other material that they can handle, and they read that with a buddy.

You could also have a listening center where students listen to books on an iPad and possibly do a written response.

Finally, we talked about high frequency words, where you have a way for them to practice the words that you're helping them turn into sight words - words they recognize automatically without needing to sound out or guess.

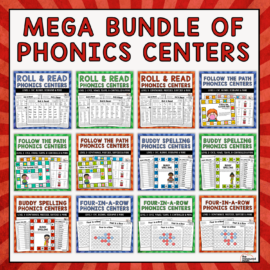

Just as a reminder, I've got that Mega Bundle of Phonics Games ready in my shop. I want to let you know that I'm going to give you a special link to check out the games. If you purchase within one hour of visiting this link, you can get all the games for $27. If you purchase all the files separately, it's $76. If you purchase the bundle, it's $49, but if you get this special offer, it's $27 as of the spring of 2022. Prices may change in the future.

To check out this special offer, head to themeasuredmom.com/phonicsgames. I'll also link to that in the show notes for this episode, which you can find at themeasuredmom.com/episode72. Thanks for listening and I'll talk to you again next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Get this bundle of 12 FREE phonics games!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

Related resources Multi-level partner plays (great for buddy reading!) Editable reading games (great for high frequency word practice)Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every ReaderJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post How to keep the rest of your class learning as you meet with small groups appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 21, 2022

Busting 12 dyslexia myths

Dyslexia is the most common learning disability, yet many people know very little about it – dyslexia myths abound!

Today, in the first of my collaborative blog series with Becky Spence of This Reading Mama, we’re going to do some dyslexia myth busting!

Myth #1: People with dyslexia see letters and words backward, and people with dyslexia always write letters and words backward.

Myth #1: People with dyslexia see letters and words backward, and people with dyslexia always write letters and words backward.This misconception may be the most common, perhaps because it’s been around for so long. Dyslexia is not a visual disorder. It’s a phonological processing disorder (more on that next week!).

If you learn of a dyslexia treatment that utilizes eye movement training or colored text overlays, it’s bunk!

This myth is especially troublesome because some teachers and parents will dismiss the possibility of dyslexia because a child doesn’t transpose letters or write backward.

Myth #2: Dyslexia is rare.Dyslexia is actually the most common reading disability. Estimates vary, but some experts say that as many as 15% of the population has dyslexia. It exists on a continuum, so people with dyslexia have varying levels of difficulty when it comes to learning to read.

Myth #3: Laziness causes dyslexia.

Myth #3: Laziness causes dyslexia.Anyone can be lazy, but dyslexia is not caused by laziness. In fact, oftentimes the person with dyslexia is working harder than anyone else in the room. Telling someone with dyslexia to just “try harder” isn’t going to solve the problem.

As Jan Hasbrouck points out in her book, Conquering Dyslexia, “children with dyslexia use nearly five times the brain areas as their neurotypical peers while performing a simple language task. Readers with dyslexia are already working very hard!”

Myth #4: Dyslexia is a sign of below-average intelligence.According to the International Dyslexia Association’s definition, dyslexia is “neurobiological in origin.” People with dyslexia do not necessarily have a low IQ, and people with a high IQ can most certainly have dyslexia.

Myth #5: Dyslexia is much more common in boys than girls.

Myth #5: Dyslexia is much more common in boys than girls.While it seems that slightly more boys and than girls have dyslexia, dyslexia affects boys and girls at almost the same rate. It’s possible that boys may be diagnosed more often because their difficulties may be more likely to lead to misbehavior, whereas girls may be more likely to struggle quietly.

Myth #6: Dyslexia only affects people who speak English.

Myth #6: Dyslexia only affects people who speak English.People from all different countries may be born with dyslexia (remember, it’s neurobiological). But depending on how their language works, dyslexia shows up in different ways.

Myth #7: Dyslexia is a result of parents not reading enough at home.I cringe when I look back to my teaching days and remember one particular child that most assuredly had dyslexia. I knew nothing about it at the time, so my top advice was for his parents to read to him more. (These caring parents had been reading to him consistently for years.)

Reading more to our kids has countless benefits, but reading to a child with dyslexia will not overcome this neurobiological condition. Dyslexia is caused by a difference in how the brain works (more on that next week!).

Myth #8: People with dyslexia always have special gifts in other areas.

Myth #8: People with dyslexia always have special gifts in other areas.This is a myth we’d like to be true, but the fact is that many people with dyslexia do not show signs of giftedness. In speaking with a dyslexia tutor in an online training, she told me that this myth is dangerous because of the discouragement it can cause. It can lead students to say, “Great. I have dyslexia AND I don’t have any special talents. I’m not even good at being dyslexic.”

Myth #9: An FMRI scan can be used to diagnose dyslexia.This would be handy, but this technology can only show differences between groups of individuals with or without dyslexia. It doesn’t have the ability to distinguish individuals with and without dyslexia.

Myth #10: Dyslexia cannot be identified until third grade.

Myth #10: Dyslexia cannot be identified until third grade.This may be one of the most damaging myths, as early identification is crucial so that proper intervention can begin. Students at risk for dyslexia can be identified as early as four years old, and possibly even earlier.

Myth #11: With time, a person will outgrow dyslexia.Our children are precious, and we must always bear in mind that if a child is not evaluated and later proves to have dyslexia, we have robbed him of precious time.

Sally Shaywitz, in Overcoming Dyslexia

Dyslexia is a lifelong disability, and we can’t cure it.

Myth #12: People with dyslexia cannot learn to read and spell.

Myth #12: People with dyslexia cannot learn to read and spell.This is a myth we are especially happy to debunk! It may require a great deal more effort and time, but children with dyslexia can learn to read and spell with systematic, sequential, explicit instruction

Stay tuned for the rest of this dyslexia series!

References

Conquering Dyslexia , by Jan Hasbrouck Overcoming Dyslexia , by Sally ShaywitzThe post Busting 12 dyslexia myths appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 20, 2022

How to plan and teach small group phonics lessons

TRT Podcast#71: How to plan and teach small group phonics lessons

TRT Podcast#71: How to plan and teach small group phonics lessonsHow should you form your phonics groups? How often should you meet with each group? What specific activities should you include in your lessons? We’ve got the answers in this week’s episode!

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, hello! Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and today we're going to talk about how to form your small phonics groups, how to schedule your meetings with those groups, and what to do when you're meeting with the group. We're basically looking at the nuts and bolts. We're really dialing in to see how we're going to apply all the things you've learned about the science of reading and structured literacy to your day-to-day teaching.

I know we sometimes get really excited by all the things we get to learn, but when it comes down to actually applying it, it gets very tricky, so I want this to be a really practical episode for you. Please remember that anything I'm sharing can be found in the show notes, themeasuredmom.com/episode71. You're definitely going to want to head there because there's a lot of useful links and materials you're going to find.

Now, first thing, why small groups? Why can't we just teach the on-level phonics skill to the whole class? While plenty of teachers do this, it is not my preference because your students, as you know, are at so many different levels. What some teachers do is they teach the on-level skill to the whole class, and then they differentiate in small groups, maybe they meet with kids who are struggling and give them extra support.

But to me, it doesn't make sense if you have someone who is still struggling to read CVC words, but then you're trying to teach them long vowel teams with the whole class. To me, it makes more sense to meet with them in a small group with other kids who are struggling with the same skill so they can get lots of practice on that skill.

I also don't like the idea of having kids who are advanced in their phonics skill being part of a lesson every day that's something far beneath what they're capable of. I would much rather see those students challenged in more advanced phonics skills, multisyllable words, and so on.

In their book "How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction," Sharon Walpole and Michael McKenna promote this model where you assess students and then you group them by their needs and that's their main instruction. Their main instruction is not whole class, it's in these small groups. They said that the benefit of this approach is that "no students who have already mastered foundational skills for their grade level will receive redundant time-wasting instruction."

This was brought up in a Facebook group I was a part of, and someone said, "Is it really so bad to be bored for twenty minutes a day?" But I don't think that's the point. I think the point is that we're not giving them what they need. They don't need the same thing over and over that they've mastered at least a year ago. They need to be challenged and move into the next stage of phonics knowledge.

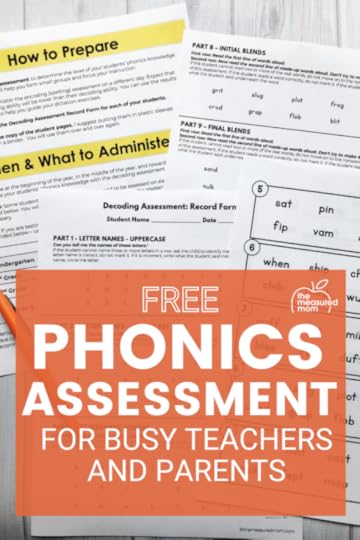

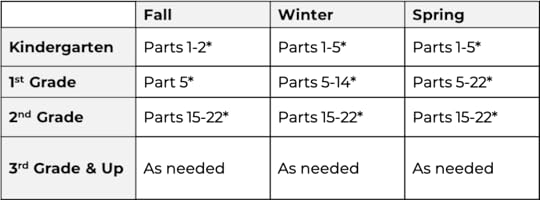

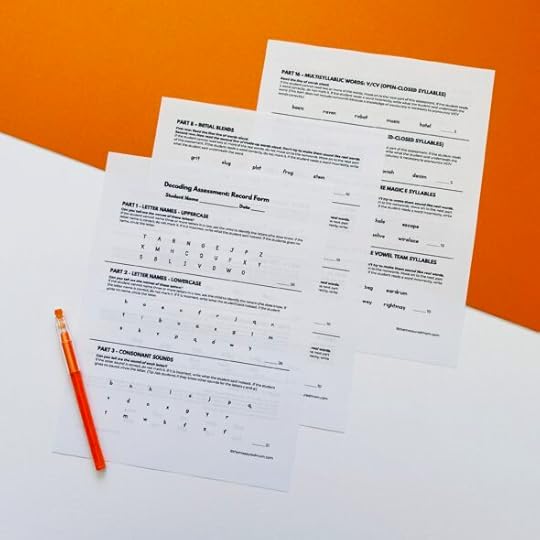

That's my philosophy, I do think it's important to group students by level. First, you're going to give them a phonics assessment. I have one free on my website and I will link to that in the show notes, themeasuredmom.com/episode71. After you've given that assessment, you're going to look at the results and group your students into four groups.

Now, you're going to look at the results and you're going to want to group your students into ten groups because they're going to be all over the place, it's not going to be evenly divided. It's okay though to have some students move back a little bit to review. It's still, when you think about it, way better for them than having them be doing the same skill with the whole class. The groups will not be perfect, that's not possible, but you're going to be doing a much better job than if you're teaching everyone the same thing every day.

The reason I recommend having just four groups is that you'll be able to meet with them enough times per week to make a difference. If you have too many groups, you're not going to be able to see your advanced readers very often. We want everyone to be meeting with you as much as possible, so I recommend meeting with three groups per day, each group for twenty minutes. Fifteen minutes is a little short, and I think you'll find yourself stressed out if you try to do it in fifteen. Thirty minutes would be awesome, but that's really unrealistic because then you're trying to keep the rest of the kids busy and engaged while you're meeting with a small group.

Now, if you're in a really ideal situation where you have other teachers of your grade level doing the same approach that you are, one teacher could do the lowest level group, one could do the next highest, and so on all at the same time. If you did that, you could meet with all the students every day, but I totally understand that that's not realistic. So assuming you're not in that really exciting situation and you're doing all the teaching, I would meet with three groups per day, twenty minutes per group.

Now, you might be thinking, "Okay, but we have four groups. How does that work?"

Here's what I recommend. I recommend meeting with your lowest group every day. In fact, I would just start always with them so they know when phonics time starts, they go to the table. It's a routine they can get used to.

After that, I would recommend meeting with your next lowest group four days a week. One of those days you're not going to see them, maybe on Wednesday, but they meet with you four days a week.

Then you're going to meet with your second highest group three times a week and your highest group also three times a week.

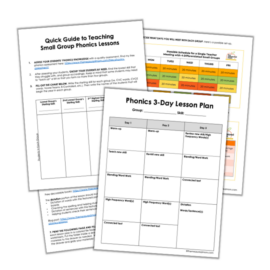

I actually have a visual chart that would show you how this could look. I'll put it in the show notes for the episode, themeasuredmom.com/episode71.

Now the question is, "Okay, I've got these groups, and I know the skills I'm going to teach them, but what do I do with them in those twenty minutes?"

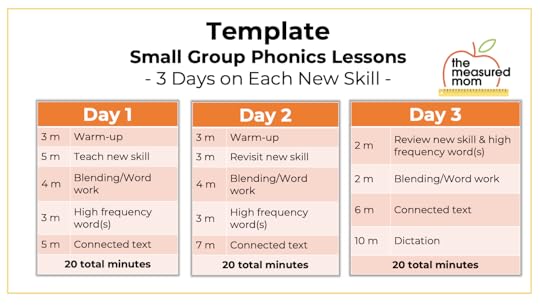

That is a really good question, and I want you to know that in the show notes, you're going to find a link to a PDF where I'm going to give you a layout of what those lessons could look like and what things you could do within those twenty minutes. I'm going to go through it right now also, but you don't need to write this down, just make sure you check the show notes at the end of the episode, themeasuredmom.com/episode71.

So let's say that you teach each skill for three days. That means that your lowest group is going to get through one skill a week plus two parts of another, whereas your highest groups are only going to get through one new skill each week. That's totally fine. They're advanced, and they're probably going to learn much faster. You could maybe move ahead and get to another skill sooner than you might think or it's okay because they are far above grade level and they're going to be doing just fine. But you can see that in giving more instruction to your lowest readers, they have a better chance of getting up to grade level.

In those lessons, the first day of the new skill, you're going to do some kind of warm-up. A warm-up could include a visual drill like flashcards. It could include a kinesthetic drill where you say the sounds and they write the letter that makes the sound in a tray. You could have a little poster, an individual poster for each child, where they point to the letters when you say the sound. There's a lot of things you could do to review previously learned skills. That could also include practicing high frequency words that you've taught. It could include a phonemic awareness activity that gets them ready to learn the phonics skill. Those are all really good things you could do during the warmup.

Then on that first day, you're going to teach the new skill. You're going to explicitly tell them what you're teaching them - what the new sound-spelling is. Maybe it's that the letter A represents /��/. Maybe it's that "sh" represents /sh/. Maybe you're teaching them that there's two very common ways to spell /��/, "ee" and "ea." Whatever it is, you're going to teach it very clearly and explicitly. That would probably take about five minutes.

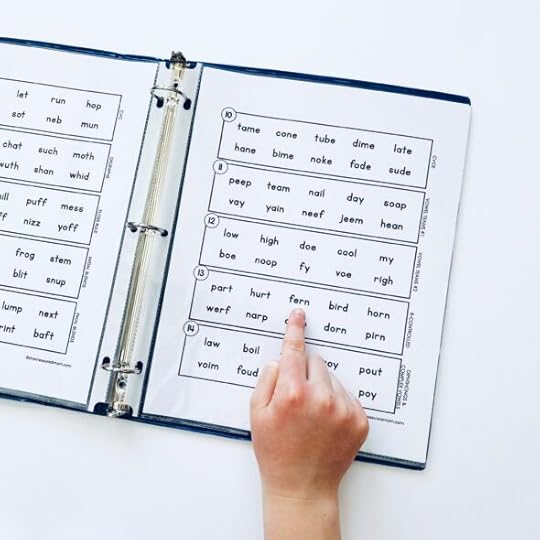

After that, you're going to do some blending or word work. As they're getting ready to read connected texts later in the lesson, you're going to help them practice for that by reading blending lines.

So let's say that the skill that you've taught your students is that "ee" says /��/, you're going to have lines of words for them to practice that include words that have the "ee" spelling in addition to lines that are review - previously taught sound-spellings. Then at the bottom, you could have some advanced words that could challenge them, words with "ee" that have inflectional endings, for example, like "ed" or "ing."

Also during that blending or word work time, you could do something like word building with letter tiles. You could have them cut out a certain number of tiles that go with that day's lesson, and then you're going to tell them words to spell, and you'll watch them build the words. You're going to say, "Change one letter to make the word..." So it's word building and switching of those letter tiles.

You could do word sort. Let's say you've taught that "ee" and "ea" spell the sound /��/. You might have two headers, one with "ee," one with "ea," and a bunch of words. They practice reading and then moving those little slips of paper into the different columns.

You could do a word ladder, which is where you've got something prepared in advance. They've got a ladder on a piece of paper. On the bottom there's a word that they start with and you maybe give them a clue or tell them to switch one letter to spell a new word and it goes all the way up to the top.

There's a lot you could do in blending word work. Of course you wouldn't do it all in one lesson.

Next you could do some high frequency word instruction where you introduce a new high frequency word, perhaps one that's going to appear in their decodable text coming up. Always remember that when we're teaching new irregular high frequency words, we focus on the phonemes and the graphemes and give attention to the tricky part of the word.

The one that's usually talked about when we're giving examples for this is the word "said." When you're introducing the word "said," you could have them count the sounds, separate the word into its sounds (/s/-/��/-/d/), talk about the spelling for each sound, and give special attention to that "ai" in the middle since that's an unexpected spelling in the word "said." They could practice writing the new high frequency word. That would probably take at least three minutes of your lesson.

Then you want to spend some time reading connected text, that could be word lists, it could be a paragraph, a passage, or a decodable book. That is what you're going to do for at least the next five minutes, and that is going to be where you're going to really get started with the new decodable book if that's what you're using.

The second day of your new skill, again, you'll start with a warmup. You'll revisit the new skill and review it a little bit. Again, you're going to do some blending and word work and review those high frequency words, and you're going to spend a little bit more time with that connected text today.

So maybe the first day you did a choral reading, or maybe they read it through one time. This time you might have them read it in pairs, or you might take a closer look at that text and highlight words that have the featured phonics pattern, or maybe you're going to spend more time discussing the story, but always you want them to practice reading it first. You want to give them opportunity to gain fluency with the text.

The third day you're going to, again, review the new skill and high frequency words, but probably not spend as long, maybe about two minutes. Again, you're going to do blending and word work, but not as long. You'll do the connected text, maybe about six minutes, and then I recommend saving the bulk of your lesson - about ten minutes - for dictation. This is when you are going to dictate words with the sound-spelling that you've taught. With this new skill, they going to practice writing words and possibly sentences featuring that new sound-spelling.

When you first start doing this, dictation is going to take a lot longer than you think it should, especially if you're with kindergarten. It may be that needs to be the whole lesson, but eventually you'll probably want to work to making that just be about ten minutes long.

So that was a look at how to form your phonics groups, a schedule for meeting with them, and what to do with them when you do meet with them. I know this is hard to get in your head when it's just audio, so please do check out the show notes. I'm going to have charts there to help you see how this all works, as well as a download where you can have specific items for things to work out in each part of the lesson.

Thanks so much for listening. I'll talk to you again next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Get your quick guide here!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

Related blog posts Blog post: How to teach small group phonics lessonsBlog post: What order should you teach phonics skills? (with a free phonics scope and sequence)Blog post: Free phonics assessmentGet on the waitlist for Teaching Every ReaderJoin the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post How to plan and teach small group phonics lessons appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 14, 2022

Phonics centers that will keep students busy and learning

Last week we looked at how to schedule and structure your small group phonics lessons. One question remains … what are the rest of the students doing while you teach small groups? Today I’m sharing ideas for phonics centers!

As you teach your small groups (see last week’s post for all the details), the rest of your class needs to be working independently.

But classroom time is valuable. How can you make sure that they’re doing work that will help them grow as readers?

Ideas for meaningful literacy centers1 – Word work (phonics centers)

2 – Buddy reading (decodable passages or books, reader’s theater, partner plays, etc.)

3- High frequency word practice (editable reading games are perfect for this!)

3- Listen to audio books

4- Independent reading of books students are accountable for (such as decodable books you’ve used in phonics lessons)

Beginning readers who are learning to decode will benefit from a lot of word reading practice at centers.

Here are some ideas for low prep phonics centers your students will love! 1- Roll & Read Games

1- Roll & Read GamesI’m currently working with my youngest as I work toward a certificate in Orton-Gillingham. As I look for activities that will build fluency with our current sound-spelling, I often reach for Roll & Read.

We take turns rolling a die and reading the corresponding column as smoothly as we can. Sometimes we’ll pause so I can explain the meaning of a word.

When one of us reads a column, we color a dot at the bottom to show that we’ve read it. We stop playing when we’ve colored in the circles for all six columns.

My son loves the fast pace, and these games have been great for building his fluency with tougher words!

In the shop:

Roll & Read Level 1 – CVC Words, Blends, Digraphs & More Roll & Read Level 2 – CVCE Words, Vowel Teams, R-Controlled Vowels & More Roll & Read Level 3 – Diphthongs, Prefixes, Suffixes & More 2- Follow the Path Games

2- Follow the Path GamesEven my reluctant readers have been willing to play these Follow the Path games with me, because they enjoy the race to the final space. (And more often than not, after we’re done they ask “Can we play again?”)

These aren’t quite no-prep, because you need to cut out the cards for each game. But it’s worth the trouble, because when kids land on a gumball they draw a card and read four words in a row.

In the shop:

Follow the Path Level 1 – CVC Words, Blends, Digraphs & More Follow the Path Level 2 – CVCE Words, Vowel Teams, R-Controlled Vowels & More Follow the Path Level 3 – Diphthongs, Prefixes, Suffixes & More 3 – Four in a Row

3 – Four in a RowHere’s another no-prep game that’s easy for you and fun for kids. Just print the game of your choice, and have kids take turns reading words and covering with a manipulative.

Whoever gets four in a row first, wins! This is a quick game, so after kids finish they can play a few more times.

In the shop:

Four in a Row Level 1 – CVC Words, Blends, Digraphs & More Four in a Row Level 2 – CVCE Words, Vowel Teams, R-Controlled Vowels & More Four in a Row Level 3 – Diphthongs, Prefixes, Suffixes & More 4 – Buddy Spelling

4 – Buddy SpellingUnlike our other games, this one focuses on encoding (spelling) in addition to decoding. With this game, students roll a die and note the space they land on. Then the other player reads a word from the answer key for the first player to spell.

Finally, the first player checks his/her spelling against the answer key and marks the appropriate face on their recording sheet (see image above).

In the shop:

Buddy Spelling Level 1 – CVC Words, Blends, Digraphs & More Buddy Spelling Level 2 – CVCE Words, Vowel Teams, R-Controlled Vowels & More Buddy Spelling Level 3 – Diphthongs, Prefixes, Suffixes & MoreAnd there you have it! We’ve got four simple phonics centers that you can pull out again and again.

Consider purchasing the MEGA PACK of phonics centers. You’ll be all set!

Phonics Centers – MEGA BUNDLE

$49.00

These games will save you hours of time, and you’ll know that your students are getting good reading practice while you teach their peers in small groups.

Buy Now

Have you seen the rest of our phonics series? Check our the rest of our phonics series!

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Part 10

The post Phonics centers that will keep students busy and learning appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 13, 2022

What phonics skills should students learn in each grade?

TRT Podcast#70: What phonics skills should students learn in each grade?

In this episode I share the phonics skills we should teach by grade level. Do you agree with how I break it down?

��

Listen to the episode here

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

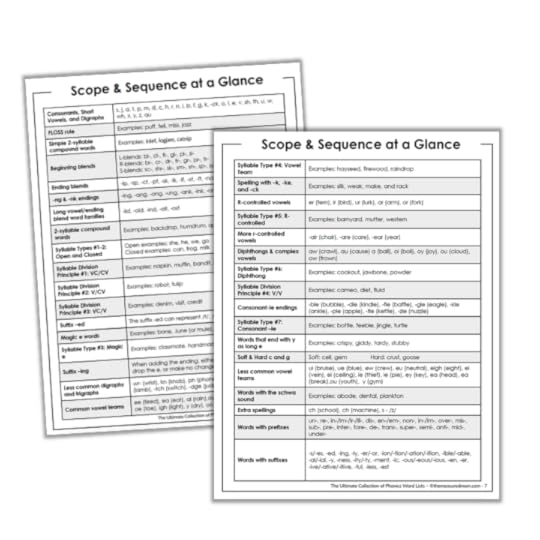

Hello, hello! Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and you are listening to Episode 70 of the Triple R Teaching podcast. We are working our way through our phonics series, and today we're going to talk about the phonics skills we need to teach, a recommended order, and how those might fit into different grade levels.

I want to start with a disclaimer, as I always do. There is no perfect scope and sequence. This is how I approach it, but there's plenty of room for flexibility.

One thing we can all agree on is that we start in kindergarten with letter sounds. Now, there's a big debate over whether we teach letter names with letter sounds or just letter sounds. I'm definitely in the names AND sounds camp, but I won't go into that too much in this podcast episode because it probably will get its own episode in the future.

Some tips for beginning phonics instruction with letter sounds is to make sure that you include high-utility sounds at the beginning, along with a common short vowel, so that words can be built and read as soon as possible. So, in other words, we're not going to teach the sound of X at the beginning. We're going to teach things like the sound of S and M and so on, especially those letters that you can sustain, like /s/ and /m/.

But our number one goal is to make sure we choose a collection of letters and sounds that children can use to read words. In my scope and sequence, I actually have the letter J towards the beginning, but that's because I use it in our first decodable book. Because of that, I need to put it towards the beginning, even though it's not as high utility of a sound. My goal is to get them to read stories, and that was the letter I needed to tell a story at the very beginning.

As you're teaching students these short vowel sounds and consonant sounds and you're helping them put them together to read VC words like "am" or "in" and CVC words like "cat" and "bit," you also could consider including common consonant digraphs in your instruction. That's actually how I do it. I sprinkle those about halfway through. We start sprinkling in ending "ck," "sh," "th," "ch," and "wh." Some people wait to teach those until they've taught all the consonant sounds, and that's perfectly fine, but this is just one thing to consider. It allows them to read more words, and you can tell better stories too.

After teaching letter sounds and how to blend them together to read VC and CVC words, I would go ahead and teach the floss rule. Now this is something that's very common in Orton-Gillingham circles. The idea is that when you have a single syllable short vowel word, you're going to double the final letter if it's the /s/, /z/, /f/, or /l/ sound. For example, the word "off." It's a single syllable word, we have a short vowel O and we have the /f/ at the end, so we're going to double the F.

You can decide if your students are ready to learn the rule or if that feels like way too much, but you can certainly teach them to read those words. It's very simple, it will open up more words they can read, and it's just a nice place to squeeze that in.

Something else I think we easily forget to do is to recognize that, at this point, even in kindergarten, students can read two-syllable words if those two syllables are made up of individual syllables that they can read. So for example, the word "catnip," a child could read that word because they can read "cat" and they can read "nip." Or if you've taught digraphs, they can read the word "bathtub." That's why, in my Ultimate Collection of Phonics Word Lists, I include very simple compound words that students, even in kindergarten, can read once you've taught them to read CVC words and basic digraphs.

Moving on, most programs will teach blends. Some put it off a little bit later, but for most, that's what comes next. Blends are when you have two, sometimes three, consonants that each have their own individual sound, but they sort of blend together.

Now this is another hot topic. Many people think there's no reason to teach blends, and that it's a confusing name because it sounds like blending. I personally think that helping students notice blends, read words with blends, and spell words with blends is good practice.

I like to think of them as three groups: L-blends, R-blends, and S-blends. Then I would move into ending blends, which are a little trickier, but also really good to focus on.

One thing I want to note, if you are doing phoneme-grapheme mapping, which I hope you are (it's when you dictate a word and then have students separate the words into sounds and spell each sound), I would encourage you to make sure that you include a blend as two sounds. In the Orton-Gillingham program that I'm following, they actually have one blank for a blend, but then they separate it with two smaller blanks underneath. Personally, I think that's confusing. I think it would be better to have a single line for each part of the blend. For example, in the word "frog," you would have four lines for /f/, /r/, /��/, /g/.

Also, when you have letter tiles, make sure that blends do not have their own letter tile. I would personally separate them, so you wouldn't have a tile that says "fl". You would have an F tile and an L tile, and that's because when they're switching things around in the word, you only need to take out one letter of a blend to change it. So for the word "slip," if you want to change it to "snip," you would just slide out the L and put in the N. So consider that as you're teaching blends.

Following this, I like to teach the "ng" and "nk" endings. Technically, "ng" is a digraph, and "nk" is a blend. It's a little bit confusing, but it can be helpful to teach those as word families. That's the way Orton-Gillingham usually approaches it. You could teach "ing," "ang," "ong," and so on. I don't think you NEED to teach them as word families, but that's one thing to consider.

Then we have some tricky long vowel ending blend word families, which are in very different places depending on your phonics scope and sequence. I think it's okay to teach them here. These would be the endings like "ild," "old," "ind," "olt," and "ost." They look like the vowel should be short, but it's actually long.

Then, believe it or not, I do think you can teach the concept of open and closed syllables in kindergarten. There are a lot of really great resources out there with an open and closed door, and I'm sure there's plenty of free YouTube videos you can watch to teach your students about this concept, but just to understand that when you have a vowel at the end of a syllable, it usually makes the long vowel sound. You can also make the schwa sound, but we're not going to talk about that right now, but I think it's a good idea because when they get to reading multisyllable words, that's something that's going to come in handy.

Now in my scope in sequence, this is where kindergarten ends, but that doesn't mean I think that every kindergartener should stop at this point. I have a little boy who's a pretty accelerated reader. He's reading chapter books, and he is in kindergarten, middle way through. I would not want his teacher to say, "Okay, well, we've taught open and closed, and now we're done because that's kindergarten." I would hope that the teacher would group students by phonics knowledge and then put them wherever that tends to be. So if his teacher were doing that, she could put him in a much more advanced group, even though she's teaching kindergarten.

In my scope and sequence, we're moving now into level two, which is actually first grade. That's when, if you'd like, you can start to teach syllable division strategies. Now, this gets confusing. I am not 100% sold on syllable division strategy teaching, just because it gets very complicated and can take a lot of time. I'm not going to give a hard and fast yes or no right now, but if you would teach it, this would be the time to teach it.

Then you'll also want to teach them about common suffixes like "ed" ends a word, and that there are different sounds for "ed."

Next, I would teach CVCE words, those are sometimes called "magic e words." I used to call them "silent e words," but I wouldn't do that anymore because silent e is in many different words, but here we're talking about the E that changes the sound of the vowel. So in the word "rake," the E at the end of the word changes the sound of the A. A better example probably would be the word "same." Instead of "Sam," we have "same." "Rake" is a little tricky because if it's a short vowel word, it ends with "ck," but you get the idea.

There is debate in the science of reading community of whether or not students need to learn about syllable types. There are six or seven syllable types, depending on how you divide them up, and personally, I'm a syllable type fan. I don't think it's all that complicated, and I don't think it has to take a lot of time. Understanding syllable types can help students as they approach multisyllable words.

With that understanding, I would recommend at this time teaching your students to read multisyllable words that include the CVCE pattern. For example, if they've learned all the phonics skills you've taught so far, they can read a word like "classmate." The first part has the floss rule, and the second part has the CVCE syllable type.

Moving on, you could teach another suffix, "ing," less common digraphs and trigraphs like "wr," "kn," "ph," and so on, and then we're going to get into common vowel teams.

I've seen different approaches for this. I've seen a program that actually recommends teaching the sound and then all the spellings all at once, or maybe a few in kindergarten and adding more in first grade and adding more in second grade. Personally, I like the idea of dripping them out more slowly so we can work toward mastery, but I don't want to say there's a right or wrong here, because I don't believe that there is. If you have a very skilled teacher, you could do it the other way.

Common vowel teams that I recommend starting with would be "ee" and "ea" as in "eat," "ai," "ay," "oa," and so on. If you check out the links in the show notes, you'll be able to find a link to my full scope and sequence, where I lay it all out.

Now this probably won't surprise you, but I think that after you've taught common vowel teams, you want to teach the vowel team syllable type, so once kids know a lot of these common teams, they can read multisyllable words like "hayseed," "firewood," and "raindrop."

Again, in my Ultimate Collection of Phonics Word Lists, I've got all these words for you right in order. The nice thing about the guide is if you follow my scope and sequence, the words that are listed in the guide can only be read, technically, if students have mastered the previous skills. There's not a bunch of mix up. If you choose to follow my scope and sequence, the guide is the perfect supplement for you.

Moving on, you can focus on teaching the spelling of the /k/ ending of words, whether it's K, "ck," or "ke."

Then we've got r-controlled vowels. This is really the bugaboo, I think. It's all over the place. Some people teach it right after CVC words, some people teach it more in the middle, and some people teach it way over here. This one was a real struggle for me is to figure out where to put it, but in the end, I went with the Orton-Gillingham approach. I don't think it's wrong to teach it earlier, this is just how I've chosen to go, but there's plenty of options.

When we're teaching r-controlled vowels, we want to teach students the spellings of words with the /er/, /ar/, and /or/ sounds. Then, of course, you want to go on and teach the r-controlled vowels syllable types.

Now in my scope and sequence, we're coming to the end of first grade. The next section moves into second. It is not to say, again, that plenty of first graders aren't already moving on to this. It depends on where they land when you assess them at the beginning of the year or midyear or whatever. Plenty of kids in first grade will be moving on to what I call level three.

Level three would be diphthongs and complex vowels. The diphthongs are "oi" and "oy" (the /oy/ sound because your mouth changes as you turn into the next vowel). Then you've got "ow," where you can feel the change in your mouth again. I've often included "aw" as a diphthong, but technically, it's really not because your mouth doesn't really change. I just find it really hard to find a place for it, so this is where I teach "aw." I call it a complex vowel. That's just kind of a tricky one.

Then, of course, there's a diphthong syllable type. Some people don't separate vowel team and diphthong syllable types. I chose to do that in my scope and sequence because that's how Orton-Gillingham approaches it, but you could just lump diphthongs in with vowel team syllable types if you want to keep it extra simple. At this point, you could teach more syllable division principles if you wanted.

Then I want to talk about consonant-le, so words like "apple," "bridle," and "fiddle." This would be the place to teach that ending. Then it's also the consonant-le syllable type, but if your word ends with a consonant-le ending, it's already multisyllable, so there's not a lot of difference here.

Then we could teach words that end with Y as long E like "crispy," "giddy," and "stubby." Of course, you could teach this much earlier as well, it's just where I put it in my scope and sequence.

Then we've got soft and hard C and G, which is a little complicated spelling-wise, but that's where I put that here.

Then we have some less common vowel teams and words with schwa. Now, you probably should have had a lesson about schwa way back when you had your students learn to read multisyllable words with open and closed syllables because, in so many words, the unaccented vowel softens into a schwa.

Actually, schwa is the most common vowel sound that there is, believe it or not, and even my little kindergartner, albeit he is an advanced reader and speller, but he has learned to identify the schwa in a word. For example, in the word "bacon," once he's divided it into syllables, he knows right away that the O represents the schwa because otherwise, it would say /b/ /��/ /k/ /��/ /n/.

You can help your students recognize when a vowel makes an unexpected sound. I think it's good to note that the schwa sound can be /��/ or /��/, because you could say bacon, bacon, bacon {Anna pronounces the word with multiple schwa sounds}. It's a mix, so teach them to listen for the /��/ or the /��/ when you wouldn't expect it. The schwa is really important to teach because when students are sounding out multisyllable words, it won't sound like a real word sometimes unless you adjust the vowel. Some people call this flexing the vowel, it's just playing with it until you land on a real word.

Finally, in my scope and sequence, we've got extra spellings like "ch" for "school," just the very uncommon spellings that you might see, and then finally, prefixes and suffixes.

That's a lot that I went through today. Just as a reminder, this is my approach. It doesn't have to be yours, but if you choose to follow it, you're going to especially love my decodable books that follow the scope and sequence.

We just released our first set of books. There are sixteen of them, and they teach short vowel sounds, consonant sounds, and the basic digraphs. We're slowly adding more.

If you're part of our membership, The Measured Mom Plus, you will get each book as it's released, and you won't have to wait for the whole set. In the membership, we do give each book in all its printable options, plus the supplementary resources like the blending lines, the dictation practice, and so on.

Do check out the membership, themeasuredmom.com/membership, if you'd like to get your hands on my resources, but there's certainly plenty available on the main site as well. I'll provide links to those things in the show notes for today, which you can find at themeasuredmom.com/episode70.

Thanks for listening, and I'll talk to you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Links you’ll love

Ultimate collection of phonics word lists

What order should you teach phonics skills? (with a free scope and sequence)

Free decodable book series��

Free phonics assessment

All our free phonics printables

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post What phonics skills should students learn in each grade? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 6, 2022

What you need to know about Orton-Gillingham

TRT Podcast#69: What you need to know about Orton-Gillingham

What IS Orton-Gillingham anyway? Is it backed by research? What do critics have to say? We’ll answer these questions and more in today’s episode.

Listen to the episode here

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger from The Measured Mom here, and welcome to the Triple R Teaching Podcast! You are listening to the third in our series of posts about teaching phonics.

Today I want to talk about Orton-Gillingham. This was something that was really confusing to me for a long time. A lot of people told me about it, mentioned that they used that approach, or that they were certified in Orton-Gillingham. I didn't know what any of that meant. I want to clear that up for anyone who has questions and also to address some criticisms of the Orton-Gillingham approach.

First of all, Orton-Gillingham is not a curriculum, it's an approach. There are many curricula that base their instruction on the Orton-Gillingham approach, but it looks different depending on the program. Orton-Gillingham is direct, explicit, multisensory, structured, sequential, diagnostic, and prescriptive. I know that was a lot, we're going to look at what some of those things look like in an Orton-Gillingham lesson, but I want you to know that those are the qualities of Orton-Gillingham.

Orton-Gillingham was named after Samuel T. Orton and Anna Gillingham, who both were born in the late 1800s. Orton died in 1948 and Gillingham in 1963, so this has been around for a long time. Samuel Orton was a neuropsychiatrist and a pathologist who focused on reading failure and related language processing difficulties. Anna Gillingham actually learned from him and she was also an educator and psychologist. The Orton-Gillingham Approach was pioneered by these two people and, of course, named after them.

It's generally meant for being used in a one-on-one setting, but now it's becoming more mainstream as we're understanding that structured literacy is appropriate for all learners. Now we're seeing small group lessons modeled after the Orton-Gillingham approach and even whole group programs basing their lessons on Orton-Gillingham. It was initially designed for learners with dyslexia, but now many educators believe that it is useful for all students.

The Orton-Gillingham approach directly teaches the fundamental structure of language. It begins with sound-symbol relationships and then progresses to more complex concepts.

A big part of Orton-Gillingham is its multisensory lessons, they are visual, auditory, and kinesthetic.

I'm currently being trained by IMSE, the Institute for Multi-Sensory Education, so that in a few months I should have my Orton-Gillingham certificate.

Their lessons look something like this. A few times a week, you are to use a three-part drill, which is visual and kinesthetic. The visual drill is when you show flashcards of all the sound spellings you've taught so far, and students should do something like this. A says /ă/, F says /f/, or they can just say the sound of the letter that's on the card. There's also a kinesthetic drill where you say the sounds and they write the letter that represents the sound in sand or some other surface. So, if you said, "The sound is /f/", they would say and write, "F says /f/." And when they say, "/f/," they're underlining the letter.

If you've taught them multiple ways to spell a sound, they can divide their tray into two, three, or even more. So I might say, "There are two ways to spell this sound, divide your tray into two parts. Eyes on me. The sound is /s/. Repeat, /s/."

Then they would write, "S says /s/, and SS says /s/." Later on, they would also add the C, and anything else they learn that represents that sound. Eventually with some vowels, for example, they're going to have quite a few in that sand.

The drill ends with a blending drill. So you have a board and you have cards that go on it, and each card has a letter or a set of letters depending on the sound. They have blends on single cards, and they have digraphs on single cards. You point to each item, students say the sound of it, and then blend it together. It might be "/fl/, /ĭ/, /p/ - flip." Sometimes it makes a real word, and sometimes not, so they put their thumb up or down to show whether or not it's a real word.

Then you're going to explicitly teach the new phonics skill. There are different things to include here. In the approach that I'm using they want you to use a physical object as an anchor for helping them remember the concept and to start with an alliterative sentence. For example, if I'm teaching the sound /m/, I might say, "Listen to this sentence: Many mumbling mice make music in the moonlight. What sound do you hear repeated in that sentence?" And they would say, "/m/." That's actually starting with phonemic awareness.

You're going to teach the rule, so I would say, "This is the letter M, it represents the sound /m/." Then you'd have them practice writing the letter M in the sand. Depending on how far along they are, you're also going to dictate words and sentences for them to write.

There's a very structured procedure for doing this. If I said, "Write the word 'mat,'" they're supposed to pound the word, "mat," (said while pounding fist onto other hand). Then they're supposed to break it into phonemes by tapping with their fingers, /m/-/ă/-/t/, then they pound again "mat," and then they write it on the line.

For writing sentences there's also quite a structure for that as well. You dictate the sentence, you pound the syllables in the sentence, they pound and repeat with you, you point to all the lines and say the words, they point to the lines and say the words, and then they write. It is very, very structured.

IMSE calls irregular words, "red words," which other programs may call the same or something different. These are high frequency words that need extra attention because they don't follow all the spelling patterns. The procedure for teaching red words in the program I'm using is that you introduce the word, you count the phonemes in the word, you talk about how to spell those phonemes, and you talk about what's unusual - ahout the part of the word doesn't match what you think you would see.

Then there's a very structured way of practicing the word. They write it with crayon, with their paper on top of plastic netting that you maybe use for sewing I think or some of knitting, I'm not sure, I'm not a sewer, but something like that! So they write it with crayon, and then they trace it with their finger. They integrate all these multi-sensory things. They also tap the word so they would tap the spelling on their arm. So if the word is "said," they would start at their shoulder and go down to their wrist, S-A-I-D. And then they say "said" by sliding their finger from their shoulder down to their wrist. They do that multiple times.

Orton-Gillingham gets deep into the structure of language. In addition to teaching these basic sound-spellings, children learned about syllable types and syllable division. So you're looking very closely at where to divide a word into syllables based on the position of the vowels and the consonants. Then you identify the syllable types after you've divided and read the word.

Orton-Gillingham is really about teaching phonics, but a full approach like IMSE's also includes comprehension and vocabulary. Those things though will be more something that you would come up with on your own versus following a strict scope and sequence. At least that's been my experience.

That's an overview of what Orton-Gillingham looks like. There are criticisms of Orton-Gillingham, and I think some are legit and some, maybe not so much. Let's talk about that.

First of all, many people will say, this is very old, it's been around for a super long time, and it's not backed by research. The tricky part about that is it's hard to create a study that examines the efficacy of Orton-Gillingham, and there are different reasons for that.

Number one, there's many different programs that call themselves Orton-Gillingham or legitimately are based on the Orton-Gillingham approach, they just look at things differently. It also depends on the training of the teacher. If you have a teacher thrown into a classroom, expected to teach using the Orton-Gillingham approach, and it's brand new to them, it's not going to be as effective as somebody who's taken a year or two training. It also depends on whether you're teaching it with the whole class, small group, or one-on-one. Anything done one-on-one is going to be more effective probably than a whole-group approach, just because you're able to be very diagnostic in that one-on-one setting. It's a little more tricky when you're working with a larger group.

It also depends on the severity of the disability. We're being told now that twenty percent of children have dyslexia, but there's a big range of dyslexia. You have some kids who just have slight dyslexia, and that can really be handled by some structured literacy interventions, and you have kids who are severely dyslexic.

Finally, it's hard to measure the efficacy of Orton-Gillingham because we don't know what's happening in the rest of the day. If you have a child right here, who's getting Orton-Gillingham tutoring once a day, but in the classroom they're being taught to use three-cueing as they're reading and solving words, then it's a little hard to know versus somebody who's getting Orton-Gillingham and structured literacy in the class. All that said, it is hard to research.

Recently however, there was a study reported in the Reading League Journal, and I will try to find that specific journal and link to it in the show notes. This is what the authors wrote at the end of the article,

"In summary, the findings from this meta-analysis do not provide definitive evidence that OG interventions significantly improve the reading outcomes of students with, or at risk for, word learning, reading disorders, such as dyslexia. However, the mean ES of 0.22 indicates OG interventions may hold promise for positively impacting the reading outcomes of this population of students. Additional high quality research is needed to identify whether OG interventions are, or are not, effective for students with and at risk for WLRD."

This isn't specifically saying that Orton-Gillingham methods are bad, or they don't work, it's just that statistically it has not been proven that they are significantly better.

I think it's good to remember that phonics instruction should be systematic, sequential, and explicit. That's what research tells us and Orton-Gillingham is all three of those things.

However, one specific piece of Orton-Gillingham that research has not proven to be making any kind of difference is the multisensory approach. Common sense could tell us that it makes sense that we should involve different parts of the body, but that has not been proven by research, which is interesting because the multisensory is really the heart of Orton-Gillingham.

As someone pointed out in a Facebook group I'm a part of, what you would probably really need is a study that compares kids learning with Orton-Gillingham, but leaving out those multisensory things like writing and sand and arm tapping, and then kids who received the same instruction with those multisensory techniques. I don't know if a study like that is forthcoming, but that's really what you would probably need to test the validity of these multisensory actions.

One criticism of Orton-Gillingham is that it doesn't incorporate phonemic awareness. People say that's because as the original creators of this approach created it before we really knew all the research about the importance of phonemic awareness. Now I have to say, in my experience, it's not true that OG does not include phonemic awareness because we know this now, so programs are incorporating it. However, I think there is a valid criticism that OG typically goes from print to speech rather than speech to print, which we're finding may be more effective.

I don't think this is a hard thing to change in your lessons. If you're teaching a new sound, instead of saying, this is an A and it says /ă/, or represents /ă/, you could switch it around. You could give that alliterative sentence. You could talk about the sound. You could show a card from a sound wall where the sound is represented with the picture of the mouth, and whether it's voiced or unvoiced, and you could talk about that sound.

If I'm teaching the sound spelling of, /m/ is M, after I've given that many mumbling mice sentence, I could say "The sound we're going to spell today is the sound of /m/. Look in this mirror. What is your mouth doing when you make the sound, /m/? That's right, your lips are coming together and you can hold the sound /m/ for as long as you want. Plug your nose, can you still make this sound? No, not really. So, /m/ is something that we call a nasal sound."

Now, do they need to memorize that this is a nasal sound? No, they do not, but it can be helpful to give a little bit of information as they see where it belongs on the sound wall. And then you would say, "One way we spell the sound /m/, is with the letter M." Then you could help them make the letter M in the air and make it in the sand.

Personally, I think that having them form those letters with their finger and underline is good for letter formation. I've been using the Orton-Gillingham approach with my youngest as I work to get certified, and when we started he was constantly mixing up capital and lowercase letters or forming letters incorrectly. That constant practice of writing in the sand and my insistence that he forms the letters correctly has made a huge difference. So, whether or not it helps them remember the sounds and the spellings, I'm not sure, but the value of doing that for forming letters, I found to be really important.

Another criticism of Orton-Gillingham is that there are too many rules. There are definitely different approaches to teaching phonics that are also very good, that are not as rule-heavy. I think that there is something to this criticism because when you are teaching this explicit way of dividing words into syllables and the syllable division patterns, there are so many exceptions that you have to teach that it gets a little overwhelming. So, I am still on the fence as to whether I think that these very deliberate syllable division practices are worthwhile because they do take a lot of time to teach, and I do think we need to reserve a lot of time in our lessons for students to actually practice reading connected text.

That would be my criticism of Orton-Gillingham. It feels like there's a lot of word-level activity, and not as much connected text opportunity. If you are spending a ton of time doing this long procedure for red words and doing syllable division practice and doing dictation, it can be hard to fit in reading connected text, and that's the whole point! That's what we're trying to get! I would want to be careful that I'm not crowding out the connected text reading and making that just be sort of the last thing we do, if we have time. That should really be what we're doing a lot of so kids can orthographically map these words and see the value of the isolated practice that they're doing.

One thing that I think is very good about Orton-Gillingham is its focus on encoding, which is spelling. My little guy has been a strong reader from the beginning. When I started teaching him using decodable books, he caught on very quickly, but spelling is not the same. You can be a very strong reader and be a struggling speller, or just not a very good speller.

I really like the dictation exercises in Orton-Gillingham and the sentence dictation. I have found that those are really powerful. A lot of those spelling rules that feel like a waste of time actually really come in handy you when you're spelling. I wouldn't want to say to get rid of rules altogether, I definitely don't think so, because having those as a reference is really helpful when spelling.

Another criticism of Orton-Gillingham is that comprehension, fluency, and vocabulary are not in their lessons. This really depends on the program. If you're following IMSE, which is meant to be something you can use with the whole class, they do let you know that you need to include those things in the lessons. It's just that, I think I said this earlier, you have to come up with those on your own. They give you lots of examples and ways of doing this, but I wouldn't say it's necessarily part of a curriculum. It's something that you need to come up with.

I don't think that has to be a bad thing. There's a lot of really good interactive, read-aloud programs that you can buy, or you can just do them yourself. In those you teach vocabulary and you teach knowledge and you teach comprehension skills and strategies. You have to make sure that this is important to you and that you include it consistently in your day.

Now, of course, when you're reading a decodable book, there are comprehension questions at the end. IMSE includes that in all of their decodable books, and I include those in the decodable books that you can find on my website. That is really important! You want to make sure the decodable book makes sense and lends itself to questions and discussion.

As for fluency, well, we know that fluency really depends on automaticity with word reading. I think there's a lot of that in Orton-Gillingham. After you dictate the words and they write them, they should read them again to you. You can also have other lists of words that they read. But again, my encouragement is to make sure you're including lots of connected texts, and that it's not just lists of words, but actual stories in books or passages. Definitely make sure there's plenty of time for applying the phonics knowledge that you're teaching.

This was a bit of a longer episode, but I wanted to give you the big picture of what Orton-Gillingham is all about, as well as get specific about what lessons could look like, and then examine some criticisms of Orton-Gillingham and my response to those. If you'd like to find the show notes for this episode, you can do that at themeasuredmom.com/episode69. Don't forget to check out my membership for loads of support with your phonics teaching, no matter what approach you're using. You can learn more about the membership at themeasuredmom.com/membership. We'll talk to you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related resources

What Does Science Say about Orton-Gillingham Interventions? article from the Reading League journal by Emily Solari, et. al.

What is the Orton-Gillingham Approach? blog post from The Orton-Gillingham Academy

Orton-Gillingham training from IMSE

Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post What you need to know about Orton-Gillingham appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 2, 2022

How to give small group phonics lessons

We’re nearing the end of our phonics series, and it’s time to get down to the nuts and bolts. What exactly should phonics lessons look like in your classroom?

Today we’ll look at how to meet the needs of all your students using small group instruction.

My first year of teaching first grade, I was required to use a very explicit, scripted phonics program.

It was a fail.

Full disclosure: At the time I was a balanced literacy teacher and didn’t see the value in explicit phonics instruction. However, even if I had believed in the value of the content, teaching it to the whole class just wasn’t practical.

I had one student who didn’t know all her letters, two students who were reading fourth grade chapter books, and 15 students whose skills were somewhere between these two extremes.

The whole class lessons were useless to my advanced readers, who needed a much bigger challenge.

Meanwhile, the lessons moved too fast for my struggling readers.

Teaching phonics to the whole class wasn’t working.

Why teach foundational skills in small groups?In a Reading Rockets article researcher Timothy Shanahan writes, “Small group instruction tends to be more effective than whole class teaching. In small groups, it’s easier for kids to stay focused, for teachers to notice error or inattention, and there is more opportunity for interaction and individual response.” (Source: Do We Teach Decoding in Small Groups or Whole Class?)

In the article, Shanahan refers to studies that looked at small group teaching; the studies concluded that kids who had small group phonics teaching had bigger outcomes than those who had just whole group phonics teaching.

To be clear, Shanahan seems to refer to the practice of teaching the grade-level skill to the whole class first, and then differentiating in small groups on an as-needed basis.

But to me, It just makes sense to teach these crucial skills in small groups to start.

In their book, How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction, Sharon Walpole and Michael C. McKenna write that the benefit of this approach is that “no students who have already mastered foundational skills for their grade level will receive redundant, time-wasting instruction.”

When this topic was brought up in a large Facebook group, one person didn’t feel that it’s a problem for advanced readers to receive redundant teaching. “Is it really so bad to be bored for 20 minutes a day?”

I don’t think boredom is the issue. The issue is not giving students what they need.

Students who have limited phonics knowledge need focused time with their teacher to master it.

Students who are farther along need instruction on more advanced skills.

Intentional small group phonics lessons are the key.

Common questions about teaching small group phonics lessonsYou might be thinking … how am I going to fit these into my day? I can teach the whole class phonics lesson in 30 minutes, but small group lessons will take longer since I’ll be seeing multiple groups.

Other common questions include:

How should I form my groups?How many groups should I have? How often should I meet with each group?What should I do with each small group?What are the rest of the students doing?And what should the rest of my reading block look like?How to form small groups for phonics lessonsGive your students a phonics assessment that includes nonsense words (because nonsense words will help you know if they’ve truly mastered the phonics skills). You can grab mine below.Get my free phonics assessment in this post

Free phonics assessment

After reviewing the results, put students into small groups based on what they’re ready to learn next. If you are a single teacher teaching all groups, I recommend a maximum of four groups because this will be easiest to manage. To be clear: your students will not fit neatly into four groups. That’s just not how real life works. Don’t feel bad about having some students back up a little bit for review so that they can fit in a group. It’s far superior to lumping everyone together for whole group phonics lessons. Decide how you will label your groups. I prefer to label groups by color because you can easily color-code their center activities. (Just be careful to use friendly colors like blue and green for your lower groups rather than “caution” colors like yellow or red. Just my opinion!)Get ready to implement small group teaching after the first 3-4 weeks of school. In that first month, you’ll be teaching phonics routines to the whole class and teaching your students to work independently at centers (more on that next week).How to determine a small group teaching schedule

The reason I recommend four groups maximum is so that you can meet with each group as much as possible with a 3-group-a-day schedule.

There are many ways to set this up, but here’s one to try:

As you can see, with three 20-minute groups a day you will need an hour for daily small group phonics instruction.

With the above setup, you would meet with your lowest group every day, your second lowest group four times a week, and your top two groups three times a week each.

What to do with your small groupsIf you take 3 days (a total of one hour) for each new skill, your 20-minute lessons could look like this:

The warm-up could include:

Visual drill of previously learned sound-spellings (flash cards)Auditory drill of previously learned sound-spellings (writing in sand)High frequency word reviewQuick phonemic awareness activityTeaching the new skill should include:

Explicit teaching of the new concept (whether this is alphabet knowledge, a new grapheme such as ai, or a syllable division strategy)Blending/Word work could include:

Blending linesGet my editable blending lines in this post

How to use blending lines

Word building with letter tilesWord sortingWord ladders

High frequency word instruction could include:

Introducing new words by focusing on the phonemes and graphemesGiving attention to the “tricky part” of each wordPractice writing the new word(s)Check out our collection of explicit sight word lessons

Sight word lessons and sight word books

The connected text portion of the lesson could include:

Reading lists of words that feature the new sound-spellingReading a decodable passage or paragraph that feature the new sound-spellingReading a decodable book that features the new sound-spellingHave you seen our decodable books with custom illustrations?

Free decodable books

The dictation portion of the lesson should include:

Dictation of words with the featured pattern; students can write on paper or on dry-erase boardsChecking the spelling and helping students fix errorsDictation of sentences with the featured patternHelping students check their sentences for accuracyHave you seen my post about using dictation?

Why you should include spelling dictation in your phonics lessons

What should the rest of the reading block look like?

If you can set aside two hours for reading instruction, it might look like this in a first grade classroom:

10-15 minutes: Whole Class Phonemic Awareness/Sound Wall Activities

60 minutes: Small Group Phonics Lessons

15 minutes: Fluency Building

20 minutes: Whole Class Vocabulary/Comprehension (through interactive read aloud)

10 minutes: Independent reading practice (for some students, this will be practice reading their decodable books)

The above schedule is a possible schedule for first grade. It would look slightly different in other grades. For example, your kindergarten lessons might be shorter – if you meet with three groups for 15 minutes each, you’d only need 45 minutes for small group lessons.

Fluency building would not be necessary in kindergarten; you could spend that time doing more whole group instruction instead, such as shared reading.