Anna Geiger's Blog, page 17

November 4, 2022

Books about place value

Looking for books that will help you teach place value? Try these!

Sir Cumference and All the King’s Tens, by Cindy Neuschwander

In this clever book, Sir Cumference and Lady Di are planning a surprise birthday party for King Arthur, but so many guests have arrived that they can’t keep track of them. When the knight and lady count tens, hundreds, and thousands of partygoers, listeners will get a fun lesson in place value.

A Fair Bear Share, by Stuart J. Murphy

Stuart Murphy is brilliant at combining storytelling with math concepts! In this book, bear cubs are picking nuts and berries for a special dessert, but one little bear just wants to play. When the cubs count the nuts and berries by making piles of ten (and leftovers), it’s very clear that one little bear hasn’t done her part. In fact, there aren’t enough nuts and berries to make a pie. Finally the last bear does her share, and by making piles of tens and leftovers the cubs discover that they have just enough berries and nuts to make a delicious pie.

Place Value, by David A. Adler

Adler takes the complex subject of place value and explains it in a very straightforward way, alongside vibrant illustrations of busy monkeys. Truthfully, this book helped me understand place value better. It’s a must-read for you and your students!

Earth Day – Hooray! by Stuart J. Murphy

A group of kids lead an effort to clean up local parks with a soda can drive. They sort the cans that they collect into bags of ten and then 100. Eventually they make bags of 1000, having collected 5,026 total cans. Highly recommended!

The King’s Commissioners, by Aileen Freedman

This story is a little long, but eventually we get to the math lesson when the king has his assistants count all his royal commissioners. Each assistant counts in a different way – in 2’s, 5’s, and finally 10’s. I love that this book will help kids think about numbers in different ways.

Octopuses Have Zero Bones, by Anne Richardson

This beautiful, fascinating book about the world describes our system of numerals and applies them to the world. “Hummingbirds lay TWO eggs. Now let’s try placing two zeros after the two. Bowhead whales can live more than TWO HUNDRED years.” The author and illustrator teach fascinating facts as they help kids think about the powers of ten. This book is absolutely brilliant and makes a great read aloud for young and old listeners alike!

Zero the Hero, by Joan Holub & Tom Lichtenheld

This book is hilarious and worth reading even if you aren’t teaching place value. Zero feels worthless. He doesn’t add anything in addition. You can’t use him in division. And he makes numbers disappear when he multiplies. Zero runs away, leaving the numbers realizing just how important he truly is. In the end, he saves the day by multiplying himself by the Roman Numeral invaders and making them disappear. You’ll have to work a bit to make the place value connection, but this book is worth the effort.

Zero: Is it Something? Is it Nothing? by Claudia Zaslavsky

This vintage book (1989) helps students think about the different uses of zero. Sometimes, zero is nothing. But zero can also mean something – as in the number 250, or the number 305. From Tic-Tac-Toe to rounding, this book covers every possible use for zero. I recommend reading just a section at a time and returning to the book often.

Out for the Count, by Kathryn Cave

This book (published in 1991) is a little hard to find, but it’s worth tracking down. Tom can’t sleep, so his father suggests counting sheep. Soon the sheep lead Tom into the wild where he meets more creatures that he can count by tens and ones. It’s a fantastic introduction to place value!

Penguin Place Value, by Kathleen L. Stone

The penguins catch fish and store them in boxes of ten, plus leftovers. This simple little book is ideal for introducing place value to young listeners. It’s immediately obvious that this book was written by an experienced teacher; the end of the book even includes suggestions for games to enhance learning!

Looking for place value resources?

Our low-cost membership includes thousands of printables for teaching math and literacy concepts in PreK – third grade, including a fantastic variety of low-prep activities for teaching place value. CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE

The post Books about place value appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 3, 2022

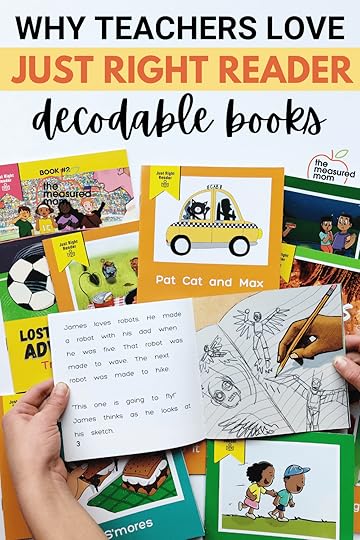

5 Reasons you’ll LOVE Just Right Reader decodable books!

Disclosure: This blog post is sponsored by Just Right Reader. All opinions are my own. I only promote products I know and love!

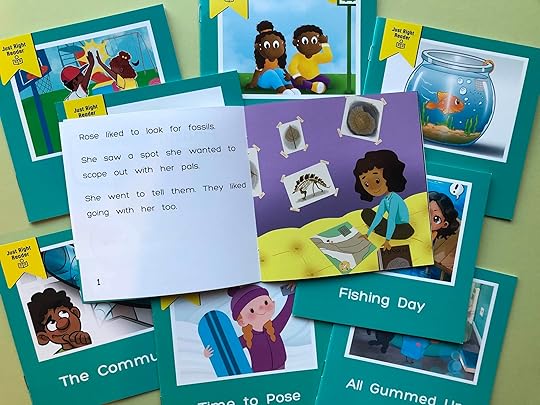

Are you looking for decodable books to fill your classroom library? You can’t go wrong with Just Right Reader!

When Just Right Reader asked to sponsor this blog post, I jumped at the chance. That’s because their giant collection of over 300 books is one every primary teacher and reading interventionist will love!

Sara Rich, an experienced educator (and former school principal!) has always been passionate about teaching reading. In fact, she received San Francisco Mayor’s Principal of the Year award after she helped schools raise reading achievement levels.

When Sara’s own daughter struggled to read, Sara saw the need for more fun and engaging decodable books.

She recruited a team of reading experts and phonics leaders to help create decodables that students and teachers would love … and the rest is history!

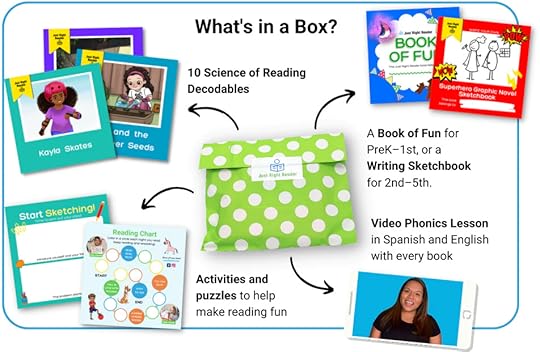

5 reasons teachers and school districts LOVE Just Right Reader Decodable Books1 – Just Right Reader has an enormous collection of decodable books for Pre-K to third grade.

5 reasons teachers and school districts LOVE Just Right Reader Decodable Books1 – Just Right Reader has an enormous collection of decodable books for Pre-K to third grade.Never run out of decodables again!

The Pre-K library includes 62 titles and teaches letter recognition and phonemic awareness. The Kindergarten library includes 50 titles and features CVC words. The First Grade library includes 110 titles and features digraphs, beginning blends, ending blends, final e, and r-controlled vowels. The Second Grade library includes 90 titles and features vowel teams, multi-consonant sounds, and final stable syllables.2 – The books are at least 80% decodable.

If you’ve ever picked up a “decodable” book and found that it contains far too many words with phonics patterns you haven’t taught yet … you know how frustrating that can be for students!

Just Right Reader has you covered. It follows a solid scope and sequence; its books primarily feature words with sound-spelling relationships that have been previously taught. The books also include high frequency words so that the sentences sound the way we speak (whew – no stilted language structures here!).

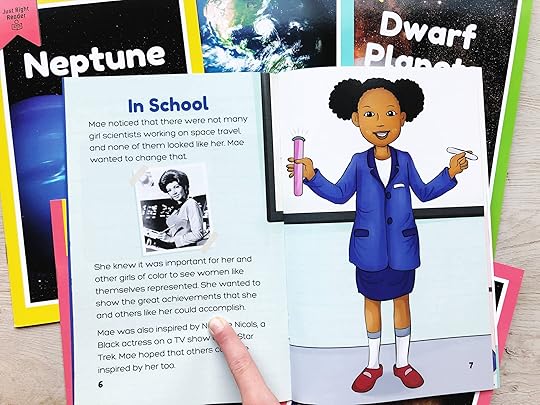

3- The books are high quality and feature a variety of engaging illustrations with diverse characters.

Decodable passages have their place, but there’s nothing like having a real book in your hands. These are solid, sturdy little books with words on the left and full color pictures on the right.

You and your students will enjoy the variety in the illustrations – since many different illustrators work for Just Right Reader, there are many different styles to enjoy!

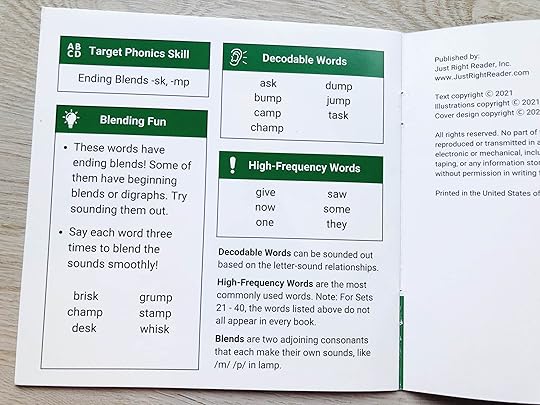

4 – Teaching tips and a QR code to a phonics lessons are included with each book.

The front of each book names the featured sound-spelling. The back pages repeat the target skill, provide extra words to sound out, and list the words featured in the book.

This is a fantastic reference for both teachers and parents — making Just Right Reader decodables the perfect choice for at-home reading.

Bonus! Each book has QR code with a link to a phonics lesson that goes with each decodable!

Just Right Reader even sells Take-Home Decodable Boxes: students get personalized-to-their-phonics-level packs of decodables to take home and keep. Parents can use the QR code on the back of each book to access the phonics lessons and reinforce what’s being taught in the classroom!

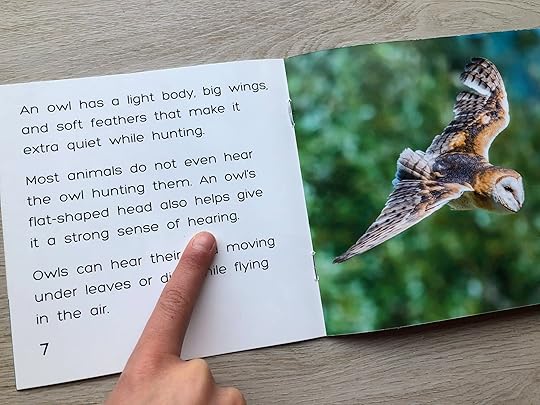

5 – Just Right Reader also sells Decodable Plus books featuring both fiction and nonfiction chapter books.

The Decodables Plus books are geared for emerging readers in third to fifth grade who are behind in reading but don’t want to read “babyish” books. The Decodable Plus library currently includes a series about planets (which includes the biography of Mae Jamison pictured above), animals of the Everglades, dangerous places, the Lost River Camp Adventure Series, and the Next-Door Detective Agency series.

And here’s something else to love …

Just Right Reader has a free e-library featuring 60 books that you can read online for FREE! These are online flip books that will let you “try before you buy.” (And trust me … you’ll be hooked!)

Ready to get started?Head to Just Right Reader’s shop where you can purchase, create a purchase order, or request a quote.

Have fun exploring!

The post 5 Reasons you’ll LOVE Just Right Reader decodable books! appeared first on The Measured Mom.

October 31, 2022

What does research tell us about reading fluency? A conversation with Dr. Tim Rasinski

��

TRT Podcast #99: What does research tell us about reading fluency? A conversation with Dr. Tim Rasinski

Dr. Tim Rasinski is an educator, researcher, writer, and director of an award-winning reading clinic. Today he shares what the research tells us about reading fluency – and how to apply this knowledge in artful ways.

Listen to the episode here

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello! In today's episode, I had the honor of speaking with Dr. Tim Rasinski. If you know anything about reading fluency, you have probably read something that he's written.

He is a professor of education at Kent State University and directs its award-winning reading clinic. He's written over two hundred articles and has authored, co-authored, or edited over fifty books or curriculum programs. In addition, his research on reading has been cited by the National Reading Panel and has been published in many journals. But more than that, Dr. Rasinski is about the art of teaching, not just about the science, but how to apply it in artful ways. We'll get started right after the intro.

Anna Geiger: Welcome, everybody! Today I'm very excited and honored to be interviewing Dr. Tim Rasinski. If you know anything about reading fluency, you've heard of him and probably read at least one of his books. He has been in education for years, given us lots of articles and books and webinars. Today, he's going to talk to us about reading fluency and what we can learn from the research. Welcome!

Tim Rasinksi: Hi, Anna! Glad to be with you. Thanks for setting this up!

Anna Geiger: Can you talk to us a little bit about how you got into education, and then what led you into studying fluency, and then where you're at today?

Tim Rasinksi: Oh boy, that's a long story because I've been at it for a while.

Actually, my college degree is in economics. I had this aspiration to be a, I guess, a businessman, a banker, something like that. But at the time I was in the service, and when I got out of the service I worked in a bank for a while, and I had friends who kept telling me, "You know, you work with kids pretty well. Why don't you think about being a teacher?"

Well, I come from a family of teachers, and I know how hard they work, and I said, "I don't want to work that hard!"

But nevertheless, that's what happened. So I used the GI Bill to become a teacher outside of Omaha, Nebraska. I taught elementary, the middle grades, and was a reading specialist for several years.

Actually it was there that my interest in fluency was developed. I was working as a Title I reading interventionist, and I'm working with these kids who, by definition, are having difficulty with reading, and I'm doing everything that the book tells me to do. I'm working on phonics and phonemic awareness and vocabulary and reading comprehension. Most of the kids I was working with did pretty well, but there were some that I just couldn't budge off the dime.

Fortunately for me, I was working on my master's degree at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. So if there's any Mavericks out there, it's a shout out to you guys. But the professors had us reading some of these articles that were just beginning to appear on reading fluency.

I'm not even sure I knew what fluency was at the time, but I read these articles. One was called "The Method of Repeated Readings" by Dr. Jay Samuels from the University of Minnesota, another one by Carol Chomsky, "After Decoding: What?" After you teach kids to decode words, but they're still not making any progress, her answer was reading fluency. So I read these, as well as Dick Allington's piece, "Fluency: The Neglected Reading Goal."

Anyways, what happened was I said, "Okay, well, I'll give this a try," and I tried out repeated readings and assisted reading with the students I was working with, and, lo and behold, they began to make progress. In some cases, it was pretty breathtaking. In other cases, it was more muted, but it was there.

And so I jumped on that bandwagon, started my PhD work at Ohio State, and met up with my advisor, Jerry Zutell, who also had an interest in reading fluency. We've worked together over the years, but that's how it got started, actually, as a very practical problem, working with kids who are having some difficulty in reading.

So I got on it forty-plus years ago, and I'm still at it. I'm still trying to discover more things about fluency and why it's important.

Now I do research. We just did a study that got published in the Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy about fluency in adults.

But what I really see myself as is a person who bridges research into practice. I think we have a huge need for that in our field. It's one thing to have the basic research into literacy, but then how do you actually apply that in the classroom? That's what I call the art. We're in this age now of the science of reading, but there's also an art of reading as well. It's that blend. That's where I kind of see myself positioned, not only my own research, but the research by other people, and trying to translate that for teachers who are in the trenches.

Anna Geiger: Yes, that is extremely appreciated. I think a lot of teachers, myself in the past included, see researchers and they think, "Well, what do they know? They've never been a teacher." For people to hear that many researchers were actually in the classroom, and still have a foot in the classroom, is good. And especially, we appreciate the bridging, too, because for teachers, reading those big, complex articles may not be what they want to do after a long day in the classroom.

Tim Rasinksi: Right. And in many cases, the research that we do is under such controlled circumstances, that it doesn't even begin to approach what teachers find in the classroom. So we need that, those folks who bridge both positions and try to translate that for teachers, because you're right, many teachers just don't have the time to dig into those 30, 40-page studies. And so it's up to me and my colleagues like me to kind of pull out those nuggets and talk about, "This is the way it can be done." And I think we need more of those folks.

Anna Geiger: Yeah, for sure. Speaking of those nuggets, what would you say, for the average teacher, what are the big takeaways from research for teaching reading fluency in the classroom?

Tim Rasinksi: Boy, I could go on that this one for quite a while.

First of all, the idea that reading fluency is not a uni-dimensional construct. It's actually made up of two subcompetencies. One, everybody knows about, we call it automaticity in word recognition. It's the ability to recognize words so automatically that when a reader is reading, they're not really paying all that much attention to the words. They're recognizing those words automatically, and so all their mental attention can be devoted to where it really matters: comprehension.

I teach a course here at the university on phonics, and one of the first things I tell my students is, "The goal of phonics instruction is to get students not to use phonics."

Anna Geiger: Yes.

Tim Rasinksi: As adults, we don't use phonics hardly ever, maybe once in a while, but most of the words we encounter are basically sight words. They're up there in our heads, and it's just a matter of seeing the word and instantly accessing it, not only the sound, but the meaning, and then applying it to comprehension. So that's one thing. Most people know about that because they're familiar with the way we measure automaticity, it's usually the speed of reading. How many words per minute can you read correctly?

But there's this other part. I often call fluency a bridge between word study and comprehension. Automaticity is part of that bridge that links to word study. But the other part that links to comprehension is what we call prosody, or I would prefer to call it expression.

If I think about somebody who's a fluent reader, it's not somebody who reads fast, but it's somebody who uses their voice to make meaning. They get loud and soft and fast and slow. They have dramatic pauses. They phrase the text into meaningful units. We know that that's a big part of fluency as well. What the research is pretty clear on is this: students that read orally with good expression, when they read silently they tend to be our best comprehenders. And this is across all grade levels.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress, again, getting back into the basic research, in 2019 they did a study on that with fourth graders. They found that there is a relationship, kids that read with greater expression, enthusiasm, even joy, if you will, they tended to be better comprehenders as well. So it's both of those things.

What happens is sometimes we get overly focused on that automaticity part, that the expression part gets neglected.

I was just chatting with a teacher earlier today and yesterday about this where her school has a goal for all kids in her grade level, I think it was third grade, to read at a particular speed at different points in the year, and the kids are actually graded on speed. She was kind of concerned about that because how can I develop prosody if I'm trying to get my kids to read as fast as possible?

You can't. I mean, when you're focused on speed, the rest of it goes by the wayside, even the comprehension part. I'm just trying to go from part A to part B. I have a friend, Chase Young, who calls this NASCAR reading.

We had a couple kids in our reading clinic just a few months ago, second graders, that came to us because they were experiencing difficulty. And so what we do is we have them read a couple of passages for us, and of course we try to analyze what's going on. Both of these kids looked up at the clinician who was working with them at the time and said, "Am I supposed to read this as fast as I can?"

Where's that coming from? Yeah, it's coming from all of this, and I'm not putting down teachers. These are well-meaning teachers trying to do the best, but it really doesn't work.

We want kids to be fast readers, but we want them to become fast the way that you and I became reasonably fast readers, and how was that? We just read a lot. You practice, and you become more automatic, and the speed just shows up. But you also learn how to modulate the speed ... slower here, faster here, and that metacognitive awareness of reading fluently.

So those are the two main things, this two-dimensional part of it. Then let's talk about the way that we teach reading fluency.

I like to think that there are three basic components. One is that we want to model fluent reading for kids. We want to read to kids, and when we read to kids, not only talk about what we've read, but talking about HOW you've read it, if you're the teacher. Did you notice how I changed my voice when I became a different character? So the kids developed that awareness of what prosodic fluent reading is like.

The second part is what I call assisted reading. That's where a student is reading something, but they're hearing it read to them at the same time in a fluent matter. It could be done in a variety of ways. This could be working with a group, choral reading. It could be reading with a partner. It could be a parent or a teacher or even a classmate who's a somewhat better reader than them. It could be reading and listening to something that was prerecorded. The most unusual one is something where a captioned television has been suggested as a way to develop that assisted reading, because when you watch captioned TV, you're seeing the words on the TV and you're hearing them at the same time or close to the same time. It's not exactly the best reading, but it is reading. When we're talking about kids who are having difficulty, we want to cast as wide a net as possible. Any opportunity to get kids in front of words is certainly worth it. So that's the second part, assisted reading.

Then the third part is practice, but there's two kinds of practice.

The most common kind of practice is wide reading. Dick Allington writes about that a lot. We know that kids who read the most tend to be our best readers, so we want to get kids into reading one thing after the next. That's what I usually define wide reading as. I read one book, then the next, and the next, and the next.

But we also have this thing called repeated reading. That's where we ask kids who are, again, not-so-good readers to read something multiple times until they reach a point where they can read it reasonably well. They begin to approximate what a good reader does.

What we have learned is that when that is done ... I mean this is what Dr. Jay Samuels found years ago. When kids do that, of course they get better on this piece that you practice over and over again because practice makes perfect. But the key is, when they then move on to a new passage, something they've never seen before, something that's even more difficult than the one they just practiced, we find improvements there as well. There's a sense of generalization there. That's something we want to build into our instructional approaches.

So the key is, and again, here's sort of the art of it, how do teachers do this? How do teachers do the modeling, the assisted reading, and the repeated reading to develop fluency with our kids?

What often happens is we do the repeated readings to increase reading speed. Read this five times until we can read it at 120 words per minute.

To me, I call that fake fluency. Where, in real life, do people practice a text to read it fast? The only thing I can think of is those drug commercials we hear on the radio where they list all the bad things that are going to happen to you if you take this particular medicine or drug.

Okay, so those are the things. Now, may I continue? I'm kind of dominating the time here.

Anna Geiger: Of course, of course!

Tim Rasinksi: See, this is where the art comes in. The science of reading fluency tells us modeling, assisted reading, and repeated reading. But how do you actually get kids into this?

Now we see all this timed reading stuff, and that's adhering to the science. But the art is this: why would anybody want to engage in reading a text multiple times?

The artful answer, to me, is performance. If you're going to be in a play, if you're going to sing a song for an audience, if you're going to recite a poem for a poetry slam, you have to rehearse. What is rehearsal? It's repeated readings. It's not repeated readings to read fast. It's repeated readings to reach a point where you can read that text with adequate speed but also appropriate expression and meaning so that an audience would find what you're reading satisfying and meaningful for them. That's the art.

So the question then for me is, are there certain kinds of texts that are meant to be performed orally? That's where we come into things like song, poetry, reader's theater, a lot of these kinds of texts that many of us grew up with. I grew up with poetry, and songs, and putting on plays. Now it doesn't seem like we have the time for that kind of stuff, and I think we should find it because the nature of poetry itself is so rich. It's rich with meaning and metaphor, and that should be part and parcel of our reading programs.

Also things like, well, lots of texts, and I don't want to overdo it, but even things like oratory or speeches from American history. In November is the anniversary of the Gettysburg Address, so I will have students in our reading clinic rehearse and perform at least portions of Mr. Lincoln's speech, "Four score and seven years ago ..." But the goal is to learn to read it with that kind of expression that perhaps Abraham Lincoln did. That requires rehearsal.

That's the art. We're taking the science, and not dismissing the science, but finding a way to apply it in artful ways. That's why I often say teaching is so difficult because you have to be both an artist and a scientist. If you want to be a scientist, you go to laboratory and do your work. If you want to be an artist, you go to your studio. But if you want to be a teacher, you've got to do both of those things, and that's a challenge. That's a challenge that we all struggle with.

Anna Geiger: I'm sure teachers will appreciate that you have acknowledged that for them because we all know that's true.

Tim Rasinksi: Oh yeah, I mean there was a time when I would work in classrooms, sub occasionally, just to kind of keep my toe in the water, but I got to the point where it was just too hard. It's difficult. I love going into a classroom and spending an hour or so, but I've got such respect for teachers who spend day after day in the trenches. And when I say in the trenches, I don't mean that disparagingly. It's tough, really tough. And it's so sad to hear negative comments that we hear now from the media or from other folks about teaching. Teaching is not easy to do.

And yet the future of our country, the future of our world, is in the hands of teachers as well as the parents.

Anna Geiger: Absolutely. Yes, they're partners.

Now you alluded to this a little bit at the beginning when you talked about reading just to read fast, but any other mistakes that you've seen when teachers are trying to teach fluency or mistakes to avoid?

Tim Rasinksi: Well the other thing I would say would be to look at those kinds of texts because in many of the programs. I won't name any of them, but in our work on fluency with kids, what they're asking kids to read repeatedly are informational texts. And I have nothing against informational texts, they're really important. But did you ever try to read informational text with expression? I mean, basically you're conveying information, and it doesn't lend itself as easily as what I just mentioned, poetry and song and a reader's theater script, or when kids are performing a short play. So try to keep that artfulness there, that notion of reading with expression in the kinds of texts kids read. And find ways to make it every day.

Tim Shanahan, I'm sure you're probably familiar with his work, was at one time, several years ago, the director of reading for the Chicago Public Schools. He mandated that fluency be taught every single day using many of these techniques that I just mentioned, all the way through grade 12. What he found was that the overall reading proficiency scores went up in the Chicago schools in the time he was there, and he attributed it largely to the work on fluency that was demanded.

The thing is, fluency often, like Dick Ellington said, was the neglected goal of the reading program. And to some extent, it still is. We did a study a couple years ago where we asked elementary teachers to identify how much time per day they devoted to phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. What we found was that fluency was the one that had the least amount of time devoted to it.

So we need to, of course, find time for fluency. And then what do you do during that time?

Now in our reading clinic, we actually use a lesson, we call it the Fluency Development Lesson. Keep in mind, we're working with kids who are having difficulty in reading. Our goal is for our children to feel successful in reading every single day. I want these kids to leave our clinic, go up to their moms and dads and say, "Mom, I can read something that I couldn't read at the beginning of the lesson." Well, what can you learn to read? Something not terribly long, so a song lyric, a poem, maybe a short passage from a story, or whatever.

But then we go through this process. This is a twenty-minute lesson where it begins with the teacher reading the text to the kids. They follow along silently, and they might actually read it a couple times like that. Then they read it together, chorally, teacher and students. Then the kids practice with a partner and eventually they end up performing it. You might have a parent sitting outside the classroom, and the children go up there and they perform for the parent, and the job of the parent is just to give the kids a big hug and tell them what a great job they did. Every day these kids feel have accomplished something.

How often do our kids who struggle in reading not have that experience? They work hard. Teachers work hard. But did they ever feel that tangible success of actually conquering a text. In our reading clinic, we actually find that happening. And then when we pre and post test the children, we find they're making exceptional progress, not just in fluency, but actually overall reading. Word recognition improves. Fluency improves. Comprehension improves as well.

Until we can make fluency just as integral a part of our classroom instruction, I'm going to be on my soapbox and talking to good folks like you about how important fluency is.

The other thing I'll mention ... you got me going here, I can't stop now.

Anna Geiger: That's okay!

Tim Rasinksi: Most of our state standards identify fluency as a goal, but it's usually grades K through five or one through five. But what happens when kids leave fifth grade and they're not adequately fluent, sufficiently fluent?

It becomes an albatross because our middle school teachers and high school teachers may not be trained in fluency. We've actually done research that finds that you take a look at most of the kids in high school who are having difficulty with reading, and it's usually reading comprehension, but when you strip it away a little bit, what you find is fluency is a huge problem. They read excessively slowly in that word-by-word manner. There's no expression, no joy in their voice. Of course, as a result, comprehension suffers.

So this is a message that needs to go beyond just fifth grade, into middle school and high school, because we have kids that slip through the cracks and would benefit from that kind of instruction.

Anna Geiger: I remember way back when I was doing my master's degree, we had to help some kids during the summer. I was with a BIG boy, he was like, I don't know, six feet tall, and I'm five foot two, and he was reading about like a second grader. We did some fluency poetry reading where I would read a line, then he would read a line, and when he first read a line really clearly, he just was so excited in his eyes. He was like, "That was tight! I read a line. And it sounded really good."

Tim Rasinksi: Right. I know. I know! That convinced him, "I can do something."

One of the things we built into our clinical program is that kids actually, once you learn how to do it, that's not good enough. Now you have to perform it, perform for your classmates, and perform for Mom and Dad when you go home so that they have that chance to show off.

It's just like a musician, they practice things repeatedly, but there's a purpose. That purpose is the eventual concert, the eventual performance there.

And again, yeah, you're right. I mean to see a sixth grader read The Cremation of Sam McGee, "There are strange things done in the midnight sun by the men who moil for gold." To hear those kids read like that, it's so heartwarming because, otherwise, these are the same kids who previously would mumble read. They're so ashamed of their ability to read that they'd just kind of mumble in that staccato-like fashion. We want readers who are enthusiastic and see meaning in print.

Anna Geiger: Yeah. Well speaking of having a set time of the day where you work on fluency, I mean I think obviously that's going to be different in kindergarten and first grade where in kindergarten you're working in fluency with sounds and individual words, and then that builds from that. But I can see when students are starting to read more fluently, like second grade, having a period where you do work on fluency. I'm going to write a blog post about the fluency development lesson, because I've read a lot about that, and it just seems very doable for a classroom teacher. It only takes like fifteen minutes a day, and you do something new every day, lots of things.

Tim Rasinksi: Yeah. Exactly.

Anna Geiger: Do you have any other tips for teachers if they really want to have that block of time trying to build fluency for their students. Perhaps the fluency development lesson or putting in reader's theater? Any other ideas?

Tim Rasinksi: Well, you said something that I slightly disagree with. I mean, K-1 you're working on words and phonics, and clearly you are, but that doesn't mean you have to give up on reading fluency. One of the easiest things to do is find a nursery rhyme or a poem or a song and make sure the words are in front of the kids and sing it chorally at the beginning of every single day through the course of a week or so. And then once the kids basically get it memorized, then let's start looking at the individual words within this text. Let's look at the sentences. Look at the words. Let's break the word down into its onset and rhyme. Let's think of other words that have that rhyme in them.

So it's actually the way I taught my four kids how to read. We sat down side by side, and we would do nursery rhymes and poems, and that was a big part of it. And we were able to dig into phonics, but it wasn't ... Typically, we think in terms of phonics going from part to whole. Let's learn the letters, then the sounds, which is fine, but why not go the other way too? Let's read the whole text first, and really get good at it. Then let's analyze it for its various elements.

Anna Geiger: So make time for that explicit phonics instruction, but also put shared reading into your day?

Tim Rasinksi: Exactly. Exactly.

Anna Geiger: Because it also builds prosody, which they can't get from their decodable text yet.

Tim Rasinksi: Exactly. And we're talking five to ten minutes a day. But if you have that daily song, you could do it right at the beginning of the day, right before lunch, after lunch, or at the end of the day. It is joyful. It's so neat to see kids sing. Brain scientists tell us that one of the reasons we love to sing is because it makes you feel good, and we ought to be bringing that kind of joy into our classrooms.

I gave a talk several years ago. It was actually in New York City, and we started a lecture to teachers with some songs about New York. "I'll Take Manhattan, and Staten Island, too." The following April, I received an email from a teacher who had attended that workshop. She was a first grade teacher, and I'll just give you her first name, Becky.

She wrote to me, and she said, "I started singing with my first graders. What we would do is learn two or three songs over the course of a week, children's songs that we all grew up with. And on a Friday we'd have a hootenanny or a sing-along. Then the next week we'd have a couple of new songs to learn." She called it joyful learning.

Well the reason why she wrote to me in April was she said, "Every one of my students is reading at grade level, AND they love to sing." And she said, "That had never happened before where every kid was reading at grade level!" And she said, "The only thing we did differently was brought in these songs."

And the neat thing I'll throw in about song and poetry is that they're easy to learn. The rhythm, the rhyme, and the melody just make them so accessible.

I mention this as a resource if anybody's interested. I have a website, it's called timrasinski.com. If you click under Resources, I've put several of the articles that I've written over the years. One of those articles is with that teacher. I guess I should give you her last name, it's Becky Iwasaki. She's a first grade teacher from Danbury, Connecticut, and she and I actually wrote an article for The Reading Teacher right after that, talking about how she was able to bring this into her classrooms and the results that she had.

Anna Geiger: I know you've written, I don't know how many books you've written, I have most of them, I think. I think a recent one is "Artfully Teaching the Science of Reading" with Chase Young?

Tim Rasinksi: Yes, and if I could give you a little bit of background to it.

Anna Geiger: Sure.

Tim Rasinksi: It started because I have two colleagues, Dr. Chase Young and Dr. David Paige, and last year, Reading Research Quarterly did a special issue on the science of reading.

We thought to ourselves, "Well, how about if we do one on the art and science of teaching reading?"

We focused primarily on reading fluency, and it got published. They accepted it.

Then what happened was I guess a publisher contacted Chase Young and said, "Well, are you interested in maybe turning this into a book form?" And so we did. It came out in April.

What we did was basically took The Big Five from the National Reading Panel, phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension, and we devoted a chapter to how can these scientific concepts be taught in artful sorts of ways?

So it's not just the fluency and rehearsal. We talk about ways that you can teach phonics through things like daily word ladders. Or you can teach vocabulary through Latin and Greek morphemes or word roots and having kids invent words. We really like the book. It's gotten a really nice reception from those teachers who recognize the science, but realize there's something else that's missing, and the thing that's missing is the art. And so we try with this book to give teachers permission to be that artful person. Too many times these programs that we now have for teachers are so prescriptive. There's no room for individual creativity. There's no room for students to become creative. I think we're really missing a lot when we hamper teachers in that sort of way.

Anna Geiger: Agreed. Because people that become teachers, in general, are creative people.

Tim Rasinksi: Exactly.

Anna Geiger: That's why they became a teacher, to be creative. So I think there's a lot of value in those explicit programs, but teachers have to be able to bring creativity and, like you said, art to their teaching.

Tim Rasinksi: Right. Because every one of us, we're different in our style of teaching. Every one of our students, they're different in the way they learn, of course, in their needs as well. And who else knows that than the teachers themselves? So one size does not fit all for sure.

Anna Geiger: For sure. Well, in all the books that you've written, particularly the one you just wrote, but are there any other ones that you would like to highlight before we close for today?

Tim Rasinksi: There's one that's on fluency that's getting a lot of attention. It's called "The Megabook of Fluency," written by myself and a fifth grade teacher from out of Phoenix. Her name is Melissa Cheesman Smith. I had written a book previously called "The Fluent Reader," which is more a kind of an academic book, a research-in-a-practice book. But this book, "The Megabook of Fluency," is very practical. The idea is that it's just chapter after chapter of things that can be put into the classroom tomorrow. So that would be the one I would recommend. It's gotten great reviews on Amazon. I believe it won of the Teachers' Choice Award in 2019. So I mean, that's like the Academy Awards for educational books.

Anna Geiger: Oh, cool.

Tim Rasinksi: Another thing that I often work on is what you call foundational reading, so phonics and vocabulary. I have several books out there, and they're not really academic books, they're books for teachers and kids to use. They're called "Daily Word Ladders." I don't know if you're familiar with them or not.

Anna Geiger: Yes. Yep, oh yeah. I've seen them.

Tim Rasinksi: They're little exercises where kids go from one word to the next. Research on this out of the University of Pittsburgh has found that when kids do this, these daily word ladders, they improve their spelling, their word recognition, and their comprehension improves. I think I've got about seven word ladder books out there.

Anna Geiger: Oh, great!

Tim Rasinksi: That would be the other one, and I'd invite anybody go to on Amazon and read the reviews. Generally, like 90% of the folks who write about them have said, "Kids love them, and they're actually learning as a result of that." So "Daily Word Ladders" and "The Megabook of Fluency" would be my top choices.

Anna Geiger: Well, I will link to all those things, plus other books of yours in the show notes and your website.

Tim Rasinksi: Okay.

Anna Geiger: Thank you so much for taking time and sharing this. I know people will really appreciate learning from you.

Tim Rasinksi: Well, I'm glad to do it. I'm glad we are able to get connected. My email address, too, I'll actually put it out too.

Anna Geiger: Sure. Sure.

Tim Rasinksi: My email is trasinsk@kent.edu. I'll trust you to put it in the notes too.

Anna Geiger: Sure. I will.

Tim Rasinksi: The other thing is my Twitter feed. My Twitter is @TimRasinski1. So there's a 1 at the end of Rasinski. The reason why I mention that is ever since the pandemic started back in March of 2020, I thought to myself, "Now, what can I do to contribute to teachers and parents at home trying to work with their kids?" So what I've been doing has been a couple times a week, if I can, I post lessons. I do Morphology Monday where I work on morphemes, or I provide resources, so something that a teacher could take this and download it on your computer or print it out and do it right away. Every Wednesday, what I've been trying to do is a word ladder. Then every Friday I call Fluency Friday, and I try to provide a text that kids could practice and eventually perform. If anybody follows me on Twitter, I share these every week.

Anna Geiger: That's awesome.

Tim Rasinksi: Hopefully. That's my goal is to keep doing that. And it's free. You can share it with your colleagues, share it with parents. It's my small contribution to the great work that teachers do.

Anna Geiger: Well, fabulous. Thank you so much.

Tim Rasinksi: All right, well thanks, Anna.

Anna Geiger: You can find the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode99. Talk to you next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Find Tim Rasinski here:

Email: trasinsk@kent.edu

Twitter: @timrasinski1

Website

Books by Tim Rasinski (not a complete list)

The Megabook of Fluency (with Melissa Cheesman Smith)

Daily Word Ladders

The Fluent Reader

From Phonics to Fluency (with Nancy Padak)

Get on the waitlist for my course, Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post What does research tell us about reading fluency? A conversation with Dr. Tim Rasinski appeared first on The Measured Mom.

October 30, 2022

How to build fluency with partner reading

Are you looking for more ways to build fluency? Try partner reading!

Partner reading (sometimes called buddy reading) is when students are paired up to read together.

How partner reading works

Assign reading partners. Be careful not to pair students that are very different in ability. One recommended approach is to (privately, of course) make a numbered list of your students from most skilled to least skilled. Cut the list in half. Then assign the top of each list to the top of the other list. For example, in a class of 26, Reader 1 would be paired with reader 14, Reader 2 with Reader 15, etc.The teacher chooses the text or each pair chooses a book, poem, partner play , or other reading material.Students decide how they will read the text together: reading chorally, alternating pages, or reading by line (as in a partner play).As one student takes the role of reader, the other student is the listener/supporter. A Reading Rockets article calls these roles the player and the coach.The supporter’s role is to help find the place in the text, give appropriate prompts when the other student is stuck on a word, or simply give words after a reasonable pause.Students pause periodically to discuss what they’re reading.

Benefits of partner reading

Buddy reading can be an excellent alternative to the familiar “sustained silent reading,” because struggling students can get the support they need and are less likely to be off task.

Buddy reading is also a great alternative to round robin reading, because students read much more than they would if they were taking turns with the entire class.

When taught how, students can provide each other with feedback as they monitor comprehension.

The teacher’s role during partner reading

When you first introduce buddy reading, your role is to circulate and make sure everyone is on task. You may help students with a word that neither reader knows. You might resolve disputes, help a listener/supporter with their role, or simply listen in as children read.

Another important role is to evaluate student pairings. Is one reader doing all the work? How can you help that student be more of a coach? Maybe it’s best to assign new partners.

Please note: Eventually you may choose to move buddy reading to centers, where students will read while you’re meeting with small groups; wait to do this until your students have demonstrated that they can buddy read quietly and independently. If possible (I know your schedule is tight!), try to include buddy reading outside of centers at least 2-3 times a week so you can facilitate.

Partner reading in action

This video from the Institute of Education Sciences is worth a watch!

Tips for choosing reading material for buddy reading

As noted in the video, instructional level text is appropriate for partner reading when the teacher is providing support. Don’t be afraid to provide support by first reading it to the class and/or reading it chorally as a whole group.When students are doing partner reading at centers, it would be best to use independent level text that students have read before. This is a great time to have students practice rereading decodable text, shared reading texts, poetry from their fluency development lessons, and other familiar text. At centers, it may work better to have students more closely matched in reading ability. Test it!

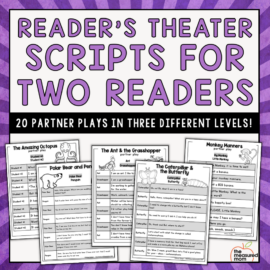

Partner Plays: Reader’s Theater Scripts for 2 Readers

$20.00

When you purchase, you’ll get a set of 20 different plays in three levels each … a total of 60 scripts!

Buy Now

How to help students learn to do partner reading effectively

This is where we have to break the process down to its smallest pieces and teach each one. I wish we didn’t have to, but we do!

Show students where in the room they may sit as they partner read.Show students how to sit “side by side” and “knee by knee.” Some teachers use EEKK: Elbow to elbow, knee to knee.Model how to help a reader with an unfamiliar word as well as how long to wait before offering support.Demonstrate what is appropriate discussion and what would be considered off topic.Provide examples of discussion starters so students understand how to talk about the book during and after reading.Will you do partner reading with your students?

Stay tuned for the last post in our fluency series!

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Coming November 7

References

Kuhn, M. & Levy, L. (2015). Developing fluent readers. The Guilford Press.

Rasinski, T. (2010). The fluent reader. Scholastic.

Reading Rockets. (n.d.) Partner reading. https://www.readingrockets.org/strate...

The post How to build fluency with partner reading appeared first on The Measured Mom.

October 23, 2022

How to improve oral reading fluency using poetry

Do you have students with poor oral reading fluency?

Their reading is slow and labored.They frequently stop at unknown words.They lack expression.They struggle with decoding.It’s no surprise, then, that they lack a good understanding of the text. After all, fluency is the bridge from decoding to comprehension.

The good news is that repeated reading has been shown to improve reading fluency.

There are many ways to do repeated reading (that’s coming in a future blog post), but today we’re focusing on improving oral reading fluency using poetry.

“Poetry has melody, rhythm, pacing and pitch that supports building fluency skills, especially prosody (expression, automaticity and comprehension)” (Hancock, 2018).

And of course … it’s fun!

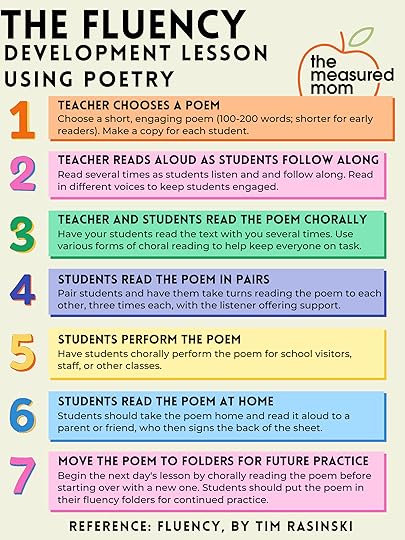

If you’re concerned that not all students will be able to read the chosen poem because you have so many different reading levels in your classroom (who doesn’t?!), the Fluency Development Lesson will save the day.

Who created the Fluency Development Lesson?

The Fluency Development Lesson (FDL) was designed by Nancy Padak and Tim Rasinski as a way to improve the fluency of students who were receiving Title 1 Instruction. Rasinski (2010) noted that the “students read the connected text we gave them in such a slow, disjointed, and labored manner that we wondered how they could possibly understand any of it” (p. 145).

After implementing FDL for several months, Rasinski and his colleagues found that students made substantial gains in the reading fluency and overall reading. The success students had with FDL texts transferred to other texts.

And … both students and teachers enjoyed the lesson! (Rasinski, 2010)

How does the Fluency Development Lesson work?

The following infographic is based on the model designed by Padak and Rasinski, with a few small tweaks.

This only takes about 15 minutes per day!

Where to find poems for the Fluency Development Lesson

The Children’s Poetry Archive has a wonderful collection of poems that are read out loud; you can also get the text. Poets.org has a set of poems for kids. You’ll just need to copy and paste them into a document and make the font larger. This will take a little more leg work, but you can get children’s poetry anthologies from the library and type up your favorites. Imagination Soup has a great list of anthologies. Copy and paste the poems from poet Ken Nesbitt’s website . These are silly and fun, and many would work for younger readers. Poetry Minute is great! Each poem can be read in under a minute. At first glance I saw a number of poems that would work for beginners.If you’re a member of The Measured Mom Plus, our affordable membership for PreK-third grade, check out our growing collection of fluency poems! (Not a member yet? Learn more here! )Stay tuned for the rest of our fluency series!

Part 1 Part 2 Coming October 31 Coming November 7

References

Hancock, L. (2018, April 27). The Dynamic Duo: Poetry and Fluency. Literacy Junkie. https://www.literacyjunkie.com/blog/2...

Rasinski, T. (2010). The Fluent Reader. Scholastic.

The post How to improve oral reading fluency using poetry appeared first on The Measured Mom.

What to do after administering the ORF: A conversation with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck

TRT Podcast #98: What to do after administering the ORF: A conversation with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck

TRT Podcast #98: What to do after administering the ORF: A conversation with Dr. Jan HasbrouckIn this second episode with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck, she shares the origins of the Oral Reading Fluency Norms (imagine compiling this data in the days before computers!). Dr. Hasbrouck also reminds us that the ORF assessment is a thermometer; after administering, it’s up to teachers to do more assessment to find the root of the problem.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Anna Geiger: Hello and welcome to Episode 98 of the podcast! Today is the second half of my interview with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck. Last week she helped us understand the concept of fluency and why it's so complicated. Today, we're going to talk about oral reading fluency.

You may be familiar with the ORF norms chart. The chart shows the oral reading fluency norms of students, as determined by data collected by Jan Hasbrouck and Gerald Tindal.

When teachers give their students oral reading fluency assessments, where they check to see how many words they can read correct per minute, they can refer to this chart to see whether their students' oral reading fluency is on track, or whether there's a red flag that we need to figure out what else is wrong that's causing them to read so slowly.

Again, I apologize. My audio for this episode is not the best, but Dr. Hasbrouck comes in nice and clear. We'll get started right after the intro.

Dr. Jan Hasbrouck: There are three publications. There are three sets of Hasbrouck and Tindal norms. The first one, the publication was in 1992, but that's a whole story of the challenges of getting research published sometimes.

I first started working with Gerry Tindal at the University of Oregon, which was the mid 80s. I became a reading coach in 1985, and by 1986 I was working with Gerry. He had come, as I had mentioned, from the University of Minnesota where he was part of a group of people who essentially invented a whole bunch of measures called curriculum-based measures. One of which was this measure of oral reading fluency, of having students read out loud for a minute and scoring their words correct per minute score. That's one of a suite of assessments called curriculum-based measures. But Gerry was a doctoral student working with Stan Deno and folks there who invented this measure.

So it was very new, but Gerry was a big believer that words correct per minute was the thing. You needed to measure that with students, and it was going to tell you a whole lot about who was on track and who wasn't. And of course, it was a brand new measure, I'd never heard of it before, and having been a reading specialist for fifteen years, I was extremely skeptical.

I just thought, as many people still do when they first hear about ORF (oral reading fluency), should we really use a one-minute measure of cold, unpracticed reading, and that would be enough to tell us anything about anything? I was as skeptical as anybody when I first heard about it.

At that time, because it was a new measure, there were no norms to indicate what those numbers should be. For a third grader reading 83 words correct per minute in the winter, what does that mean? We had no norms.

What the original researchers suggested, the University of Minnesota folks suggested, was that schools should establish their own norms, and they had procedures for doing that. They said to test all your kids and create norms for your building.

When Gerry told me that I thought, "Well, that's ridiculous!"

I had spent my entire fifteen years up to that point working in low performing schools. I said, "What's the value in assessing our low performing school? We already know we're a low performing school, who cares about the 50th percentile at a low performing school?" And I said, "We need national norms."

He thought that was a good idea and put me in a little room with a desk and a ruler and a calculator, and brought stacks and stacks and stacks of paper. Very few people back then were doing ORF measures of their students, but there were a few, and through that process of literally using a ruler, going down and typing in scores on my calculator, we came up with some norms for oral reading fluency from second grade through fifth grade.

That was the first study. That's all the data we had. I think in total it was about 10,000 students, which was still a lot of rulers and typing. That was a lot of scores for me to put in all by myself. There were no computers back at that time, or I didn't have one.

So we wrote up a little article about this new way to assess kids called oral reading fluency and what the score should be. I probably finished that work in 1987 or 1988, and it took us until 1992 to get it published because every time we submitted it, people's reactions were like mine. They were horrified! Why would we assess kids on a one minute measure? That's ridiculous. Who cares about that?

It was finally published, not in a research journal, but in a special ed teacher practitioner journal called "Teaching Exceptional Children." They saw the value of it and they published it.

Then over years the reading world discovered it. The internet started, I guess, in its early stages, and people started learning about it. It became a measure that people were interested in, but there were no national norms. There was no DIBELS or aimsweb or Acadience or FastBridge or easyCBM. In those early years, people were just creating their own assessments, so they wanted norms.

Then in 2006, we did it again. By then we had access to a quarter of a million scores from first grade to eighth grade. We did the study again and published that in "The Reading Teacher." We chose that, not because it's a reading research journal, but because we wanted to get this information into the hands of as many teachers as we could.

Then ten years after that, we thought it was time to update it, and so in 2017 we compiled our newest set of norms. That one has over six million students. This time we only had access to first through sixth grade, for a lot of reasons.

But those norms, when you look at those three sets of norms and other norms all kind of coalesce around the same. Now, of course, we have the publishers who have created commercially available assessments from that research, and looking at all the norms together, they kind of coalesce around the same. There are certainly differences between aimsweb benchmarks and easyCBM benchmarks and DIBELS benchmarks, a little bit. People using those commercially available products sometimes do go then to the Hasbrouck and Tindal norms, because ours are compiled from multiple measures. Ours are not just aligned with a single assessment.

But let's get to the second part of your question about how we should use them.

They really are to help teachers get a sense of where their students are in terms of their acquisition of automaticity. That's a very important piece of information, and to be able to acquire that piece of information in one minute is pretty extraordinary. It's not, and never was intended to be, the only measure. It doesn't diagnose reading problems. It doesn't tell us a lot. It actually doesn't really tell us about a student's fluency. It tells us about their automaticity.

There are many people who have tried hard to consider changing the name of that assessment from oral reading fluency. Because fluency, as we've talked about, is much more complex. It has expression and prosody. It is connected with comprehension. A sixty second assessment doesn't measure that, but it does measure automaticity.

So those folks back at the University of Minnesota were absolutely right that they were onto something. We now have close to forty years of research where the words correct per minute score has been shown to correlate or predict comprehension, almost better than anything else we have. And it takes a minute to do that!

So we do know that, in general, those students who have not reached the 50th percentile on an oral reading fluency measure when reading unpracticed grade level material are not on track for future success in reading.

That's the primary way I feel that those norms should be used. They should be used to check on individual students' relationship to the normative progress that we know students should have.

Some very recent research came out that I'm citing a lot. It was Wyatt et al. that did a study where they went back and looked at NAEP scores, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, and wanted to know what ORF scores, or words correct per minute scores, best predicted NAEP scores.

They were looking at fourth graders, as the first NAEP test is given to fourth graders. The fourth graders who were at the top of the NAEP, which is the advanced level, were reading at the level of the 75th percentile on Hasbrouck and Tindal norms. The students who were at the advanced level, which is where we want students to be, advanced basic level, were reading around the 50th percentile of the Hasbrouck and Tindal norms. And the kids who were not successful on the NAEP, which is a comprehension test, bottom line, were below the 50th percentile.

So that suggests to me that what we've been saying for years based mostly on hypothesis, that you need to get kids to the 50th percentile, is true, and there is some advantage to being as high as the 75th.

But that study really to me feels quite conclusive in saying that those kids who are just reading super fast don't seem to have any benefit for comprehension. Which makes sense to me as a practitioner, but now we have some good clear evidence about that.

Anna Geiger: Yeah, I can definitely speak to that with one of my kids who, of all six kids, he's the one that least prefers to pick up a book. He can read "very fluently," but I'll ask him what it was about and he doesn't always know. So I'm working on slowing him down. It's that thought that reading is a race, don't worry about expression, and that's not where we're headed.

For a teacher that does the oral reading fluency with their students and then sees that some are lower than where they should be, what's the next steps? I know you've talked about how ORF is a thermometer. It doesn't diagnose. So what comes next? If a teacher notices that someone is low, what should the next steps be?

Dr. Jan Hasbrouck: It's a very good question and it's a sophisticated question that not a lot of people are always asking.

A lot of administrators are uninformed about that idea that ORF is a thermometer and that's all. Just like in the world of a physician, if they use a thermometer to take your temperature and find you have a fever, they don't treat the fever. I mean, sometimes this might be, but the CAUSE of the fever is not identified by the thermometer. So they're not going to fix you by plunging you in a bath of ice water to lower the fever. It's not the score that's important, it's what it could indicate.

So in the medical world, a fever is an indicator that something is amiss. But in conversations that I have had with physicians about, "When you see a high fever, what does that mean to you?" They start talking about all the things that can cause a fever: it can be flu, it can be COVID, it could be a ruptured appendix, it could be other kinds of infections or inflammations. It means something's not right, but what it does for a physician is then trigger a whole other set of assessments called diagnostic assessments.

That's exactly what should happen with us too. Our students have an academic fever if they are not strongly at the 50th percentile on unpracticed grade level text.

What caused that fever? Often when I'm trying to explain this or help teachers understand this, I will pull out Scarborough's Rope again. It helps to point out that those students who seem to be stuck at the middle of Scarborough's Rope where the pieces are being woven together, they can read, but they're not reading at that tightly woven rope. They're not reading well.

Is that loosely woven rope caused just by the fact that they're not yet sufficiently fluent? Should we work on just reading more to help them become fluent? For some students, yes, that's it. They read quite well, but all they really need is to practice, practice, practice, practice to become more fluent. However, that's only a subset of those children.

For some of those children, we go back to the beginnings of Scarborough's Rope and look both at the language piece and the word recognition piece. What I have found for a lot of my students who struggle with becoming fluent readers is that it's at the bottom part of Scarborough's Rope. It's the word recognition. They have some gaps or weaknesses in the foundational word recognition skills. Like it could be they're still struggling with phoneme awareness or they're still struggling with some aspects of word recognition. And if you're struggling with both of those things, you're going to struggle with the acquisition of sight words.

A lot of our students who aren't fluent, although they may be pretty good readers, have not acquired sufficient sight vocabulary. Their orthographic mapping process is faulty. If it is faulty, it's likely some deficits in phoneme awareness and phonics, and vocabulary we know plays a role in that. We are all better at turning words into memorized sight words if we know the function or the meaning of that word.

So if a student is struggling with their fluency as measured by words correct per minute, we should do some diagnostic assessments quickly. We don't need to send them to a school psychologist for a two or three-hour deep dive. It's more that we should do a little check of their phonics or do a little check of their phoneme awareness.

If you suspect that insufficient vocabulary academic language is an issue, we have some ways to take a look at that. That's where, in most cases, you're likely going to find some things that we need to be working on along with fluency, to make sure that we do get eventually to that tightly woven rope.

Anna Geiger: I know you mentioned that this is not always understood. How are people, in your experience, misusing the results of the ORF? If they see a certain reading words correct per minute, what are you seeing some schools do that you would not recommend?

Dr. Jan Hasbrouck: Well, I would say the main thing is using it as if it were a measure of fluency that you have just used diagnostically to assess, and then saying that the treatment for that is to do lots of intensive work to help you become a more fluent reader. In too many people's minds means that means a fast reader, and that's going to be an effort of extreme frustration for everybody if that student is struggling with fluency because of underlying issues.

I think the name of the assessment being oral reading fluency implies that to people. I don't blame the end user. There's a lot of blame to go around on that. We should rebrand that assessment and not call it oral reading fluency.

These days I usually just call it a measure of words correct per minute. Words correct per minute, which is a measure of automaticity, is an indicator of proficiency in underlying skills.

So if they're not proficient, that likely means their underlying skills have some weaknesses that we can go back and do some remediation on. Depending on the age of the student, we are likely going to do that skills remediation while we also are working on fluent reading of text. So we should be doing all of that altogether. But if the intervention is just doing something to get the kids to read faster, that is very likely going to fail and make everybody frustrated.

Anna Geiger: So I've seen some teachers that have a passage that all of their students are responsible for. And at the first day of the week they read it, they check the words per minute, they actually graph it on a little graph, and they just keep doing that all through the week to see how many they get. What would be your response to something like that?

Dr. Jan Hasbrouck: I actually recommend graphing students' oral reading fluency scores over time when I do workshops on best practices in intervention. If we're concerned about students, we really do need to collect some data and monitor their progress.

I also, though, always talk about doing that kind of thing in a differentiated way. I think that we always start with the classroom time that we have and it's never enough, and if we're talking about the entire classroom of students then of course we have great differentiated needs. We've got students who are probably, in almost every classroom, sailing along and doing great. We've got some students who are just making exactly the progress we would expect. And we've got some students who are struggling.

Given the fact that there's never enough time in classrooms for the instruction, which is the most important thing we do, instruction and intervention, I want to be very cautious about how much time is being spent on data collection.

So I think teachers, just like physicians, can differentiate data collection if you think about it.

A lot of us who are reasonably well only go see our doctor once a year. We get these once-a-year assessments and we check our blood pressure and cholesterol and all that. Our doctor says, "Everything looks good. I'll see you next year."

A good friend of mine right now is in the hospital. She just moved out of intensive care following some surgery. While she was in intensive care, she was getting assessments every minute of every hour. The level of assessment goes up when the need goes up in the medical world.

And that should be the same for us too. Weekly assessments of students using words correct per minute is very appropriate if a student has very high needs because it is a very sensitive measure, and we can see relatively quickly, over a period of a few weeks usually, whether our intervention is working or not. And if it's not working, we need to do something different.

I wouldn't recommend weekly assessment of our kids who seem to be doing fine. For those students, especially in our early elementary years, I do recommend those words correct per minute benchmark checks in the beginning, middle, and end of the year. As well as teacher observation of the students as they're working, doing little checks of their spelling, which is a really interesting thing.

A teacher can say, "We've been working on words that have blends at the beginning. You can decode those. Well, now take out a piece of paper or a whiteboard and see if you can spell those words. Can you spell the word, 'slam?'"

We do little checks like that to see if indeed the kids you think are moving along are actually moving along, but that can be done just as part of small group instruction, or even whole class instruction. But I think we need to be cautious about the amount of time we devote to data collection and differentiate that based on the needs of our students.

Anna Geiger: Thank you.

I just have one more question for you. Timothy Shanahan wrote a blog post with some sort of suggestion for a literacy reading block schedule. One thing he said was that every day there should be time for fluency building. What do you think should go in that block? I know it depends on the grade, but just some general ideas.

Dr. Jan Hasbrouck: Yes, and I appreciate that Tim did that. It is important because when we consider that goal on Scarborough's Rope, that tightly woven rope, the only way we're going to get there is practice. So it's not just the grade level or age of the student to consider, much more important than that is their skill development. Where are they in their development?

At the very beginning of the rope, fluency practice is more at the sound and letter level. Kids can be doing some work outside of whole class or small group instruction in partners, or they could be doing some center work where they're practicing that.

Then you have fluency practice with really beginning novice readers. Typically that would be late kindergarten or early to mid first grade who would do fluency practice with decodable text. Again that can be independent, or it's ideal for them to be working in partners or working with an older student or somebody who can listen and do some corrections with them.

Once students, wherever they are in the trajectory, have broken the code, then they really can apply their decoding to text that has more variety to it. For those kids, once they're really quite well-established readers, that's going to be early to mid second grade, that's when sustained silent reading, independent reading, can help you be a better reader.

We do know that there's value in independent reading, but only once you've become an established reader. Before that it's the individual component parts, the word level and the very simple text level. More often that's better done not silently and not independently, but with somebody there who can listen and give you some feedback and practice.

But ALL of that is fluency practice. We sometimes think of fluency practice only for those well-established readers. But we can practice the component pieces, text appropriate for that child's developmental level, and it should be done on a daily basis for sure if we want to get all kids to that tightly woven rope. And we do want to get all kids there.

Anna Geiger: Awesome. Well, usually I edit my episodes quite a bit, but I'm not going to want to cut anything out of all the wonderful things you had to say! Thank you so much for all that you do and continue to do. I just love catching any workshop that you're giving. I always make sure to watch those. Thanks for not retiring yet!

Dr. Jan Hasbrouck: Well, thank you for your interest in my work. I appreciate it.

Anna Geiger: Please head to the show notes for this episode to find links to Dr. Hasbrouck's work, as well as the oral reading fluency norms chart, and links to many presentations that she's generously shared and that are posted on YouTube. You can find the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode 98. Talk to you next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related link Hasbrouck-Tindal Oral Reading Fluency norms Books by Dr. Hasbrouck Reading Fluency (written with Dr. Deb Glaser; for the full version of the book, see Benchmark Education’s website) Conquering Dyslexia Student-Focused Coaching Learn more from Dr. Hasbrouck!The Science of Reading: An Introduction (with the Reading League)Reading Fluency: Essential for Reading Comprehension (with Oregon RTI)Dyslexia Awareness (with McGraw Hill)Conquering Dyslexia (with Read Naturally)The Science of Fluency, part 1 (with Read Washington)The Science of Fluency, part 2 (with Read Washington)The Science of Reading 2.0: A Deeper Understanding (with Read Washington)What Do We Need to Know about Reading Fluency? (with Read Naturally)

The post What to do after administering the ORF: A conversation with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck appeared first on The Measured Mom.

October 16, 2022

Fluency isn’t just about speed: A conversation with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck

��TRT Podcast #97: Fluency isn’t just about speed: A conversation with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck

��TRT Podcast #97: Fluency isn’t just about speed: A conversation with Dr. Jan HasbrouckToday we hear from Dr. Jan Hasbrouck, a writer, consultant and researcher who is full of wisdom about the science of reading – and fluency in particular. In this episode she helps us understand the concept of reading fluency. It’s not just about speed!

Listen to the episode here��Full episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello! Anna Geiger here, and I'm very excited today to kick off our series about fluency with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck!

Dr. Hasbrouck is a big name in the science of reading community because she's been a player for about fify years. She is a researcher, educational consultant, and author. In the past, she was a reading specialist and a literacy coach, as well as a college professor, and now still after all these years, is very active in helping people understand the science of reading.

We had such a good conversation that I split this episode into two. This week we're going to meet Dr. Hasbrouck, learn more about her experience in the field of education, and learn why the concept of fluency is so complicated and how it's a lot more than just reading quickly.

I was a bit nervous as I was getting set up to welcome Dr. Hasbrouck and I chose the wrong audio for myself. So I apologize that my audio is a little muddy, but Dr. Hasbrouck comes in loud and clear.

Anna Geiger: Hello everybody! Anna Geiger here, and I am so excited to welcome Dr. Jan Hasbrouck to the podcast today! She is an educational consultant, author, and researcher, and if you're familiar with the science of reading, you've definitely seen her around. She is retired now, but still does a lot for the science of reading by giving a lot of presentations and webinars. We're going to welcome her and ask her to introduce herself. Hello, Dr. Hasbrouck!

Dr. Jan Hasbrouck: Hi, nice to be here! Yeah, and one little correction there about me being retired. I am no longer affiliated with a university, or any agency specifically like that, but I am busier than ever.