Anna Geiger's Blog, page 18

September 25, 2022

The science of reading in kindergarten

TRT Podcast #94: The science of reading in kindergarten

TRT Podcast #94: The science of reading in kindergarten094: Today we get to hear from Stephanie, a kindergarten teacher in Arkansas. Now that she understands the science of reading, she shares exactly how she teaches reading to her kindergartners.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, everyone! You might remember that in the summer of 2022, I had a blog series where I interviewed teachers who had moved from more of a balanced literacy approach to a structured literacy approach. While that series was going on, I received an email from Stephanie, a teacher in Arkansas who asked if she could come on the podcast and share her story. That's what we get to hear today, and we also get to hear how she applies the science of reading to teaching in kindergarten.

Anna Geiger: Welcome, Stephanie! We're so glad to have you here on the podcast.

Stephanie: Hello! I'm so excited to be here, thank you.

Anna: Stephanie reached out to me when I had my series all about moving from balanced to structured literacy in the summer of 2022. She's going to talk to us about how she came to understand that balanced literacy wasn't working for all of her students and how she slowly made the change to more of a structured approach, the science of reading. We're going to talk about that.

Another cool thing is that Stephanie is from Arkansas, which many of you may know has been a leader in switching to more of a research-based approach to teaching reading. So Stephanie, can you talk to us maybe a little bit about what you learned about how to teach reading when you were in college?

Stephanie: Absolutely. It's a short story. I really did not learn a whole lot about how to teach reading in college. I took a reading course and I remember they showed us how to take a running record and I learned a lot of vocabulary that helped me pass my Praxis, but once I got to the classroom and I had to teach kiddos to read, I thought, "Well, okay. I've got to figure this out now," because I didn't have instruction when I was in my college courses on how to do it.

Anna: So you just were kind of figuring it out as you went along, or were you given some resources that you were supposed to work with?

Stephanie: Both. When I first began my special education journey, I did do a fourteen day professional development on balanced literacy, and from there I was given resources and leveled readers and a DRA assessment kit. I even did some LLI small groups and all of those things. I used what I learned from my professional development the very best I could, and I had a co-teacher who had been teaching balanced literacy and she was a great help. She explained to me the cueing system, and she even had the Beanie Babies and we shared those between us, "Okay, is it your turn for the dolphin today? All right, well, I'll take the lion."

For a lot of kiddos, they did okay. In the first grade, they grew. Was it the best method? No, absolutely not, but they grew and we kept doing it for a little while.

But I had some students, as a special education teacher, that it was not effective for at all. It turned into frustration, and it was not fun to pull out those guided readers. They would see me and say, "Here we go. Oh, no! Not again!"

So I thought, "Okay, we've got to try something new." That new thing was just me with a sharpie and some index cards writing decodable words. I didn't know that's what it was back then, that's not what I called it. In fact, I think it was, we started with the "at" word family and some sight words, and we'd read "the cat" and "the rat" and "the cat and the rat," and each week we would expand those sentences.

Then we switched gears a little bit and I started making him books, and then he was reading books and stories. They were rough drafts, I think I still was using my sharpie and some notebook paper then, but even as rough as those books were, they were still better for him than the leveled text because he could read, and he could make progress, and he began to have fun and feel better about what we were doing together.

So that was a turning point for me, for sure. I didn't understand why the decodable text was better at that point, but I did know there was something to it.

Anna: I have a question for you when we're talking about decodables. I had a comment on my Instagram, not too long ago, from somebody, "If you think that these boring books are going to cause a love of reading, you're delusional," so I'd love to know your perspective on what you saw when you were using those with kids? Did they enjoy reading them? Did success breed motivation, like Anita Archer says? What was your experience with that?

Stephanie: Well, I think now there are much better decodables than there used to be. I think a lot of people have experience with some of the early ones. But listen, if a kid is frustrated, they're not having fun. It doesn't matter how pretty the pictures are, or how wonderful the story is, if they're frustrated with it they don't want anything to do with it. But if a kiddo has success, that makes them feel good, and that builds confidence.

From my experience, those decodables were a whole lot more fun than the other books just because of that success and that confidence, that sparkle that I got to see in this little guy's eye because at the end of the week, he read it so much quicker, and more fluently, and he was like, "Oh, I did it!" He didn't dread my homemade decodables like he did some of the guided readers.

Anna: I think, too, don't you think that kids know when they're actually reading and when they're not reading?

Stephanie: Oh, 100%.

Anna: He knew he was pulling the words off, he wasn't just using the picture or helping you get him started, he knew he could actually do it himself, and there's something to be said for that.

Stephanie: 100% yes, I think so, absolutely.

Anna: So this was your first move towards more of the science of reading, which you probably weren't aware of that phrase back then, or structured literacy or anything.

Stephanie: No, no idea. Mm-mm.

Anna: You were just trying something new, and it worked.

Stephanie: Right, mm-hmm. Yep.

Anna: Can you walk us through the timeline then after that?

Stephanie: Sure. That was about two years into my teaching career. After that, I continued to teach special education for a couple of years. Then I was the gen ed first grade teacher for a couple years, and then I went back to special education.

Then, two years ago, Arkansas did a huge movement, the RISE movement. It's called the Reading Initiative for Student Excellence, and every teacher across the state has to demonstrate proficiency in teaching reading, from pre-K on up through high school.

In fact, our district did a fourteen day training with the LETRS book, and we have had so many resources and experiences and opportunities to learn. Even my husband, he teaches third-grade math, had to go through it because he's an Arkansas teacher.

There was resistance, because change is scary, and anytime you completely overhaul what you're doing, there's a lot of stress and frustration in trying to figure out this new thing.

But I think once we began to shift our instruction, we did find that there were some things that we were doing that were actually still pretty good! For instance, part of our balanced literacy before RISE was read-alouds. Well, we still do read-alouds! We do them better and we focus more on vocabulary and background knowledge and things like that. Everything shifted, but some things weren't completely thrown out either.

Anna: Can you walk us through a little bit of what a day would look like in your classroom? We're recording this in September, so I know it's the beginning of the year, and it's going to look different in a few months, but what would be an average day of your literacy in kindergarten?

Stephanie: Yes, ma'am. Kiddos come in and their first step is to grab their familiar reading folder. Some teachers use a basket. I use a folder because I like it to be right there at their desk. Right now, inside a kindergarten familiar reading folder is the alphabet. As time goes on, when I really get into small group instruction and they start reading text with me, I'll give them a copy of that text after we've gone over it for a week. When I know that they can read it with accuracy, then it's going to go inside their familiar reading folder. So their folder will just expand as the year goes on and they'll have lots of different things to choose from and review what I've already taught and worked on with them. That's different for all kids, that's differentiated.

Then from there, we move into our shared reading time. At this point, it's all about concepts about print, but eventually I will start thinking aloud through all reading skills, modeling fluency, and modeling how to apply different comprehension strategies. We love to use big books with that, so the kiddos can see the print, and we talk about punctuation, and all that good stuff. If I don't have a big book, we'll do a poem or something on our SMART Board. I'll project that up.

After that, we move into phonological and phonemic awareness. We use Heggerty for that, whole group.

Then we go into phonics. Right now, we are doing a letters boot camp, just exposure to all the letters of the alphabet. When we get through our letters boot camp, we'll start our phonics program. That phonics lesson is approximately 30 minutes long, and then I have an hour of small group time and centers.

Anna: Can you talk to us about how you form those small groups and what you do in those lessons?

Stephanie: For kindergarten, at the beginning of the year, I group my kiddos based on the letters that they know because the bulk of our small group time is going to be working on letter identification, letter recognition fluency, formation of letters, all of that good stuff.

Eventually, when we start decodable text, I will start grouping more on mastered phonics skill and phonemes. My instruction really starts to be differentiated at that point because I have four groups, typically. That leaves me fifteen minutes for each group. I would love to have six groups and 20 minutes for each group, but logistically, it's not possible.

Then, within my small group, we work on phonological awareness skills and phonemic awareness skills. I use David Kilpatrick's book as a resource first thing, and I do one-minute drills from there. We work on some type of fluency warm-up activity to review previous skills. I pull in phonics instruction when we get there.

I usually have an intervention group where I'm reteaching skills. I usually have about two groups that I call my grade-level groups, and they're pretty close to just being right there on grade level, and then I have one group that is my enrichment group.

Those groups change every time I do an assessment, or every time a kiddo starts flying through letters, I move them up a group.

Anna: Sure.

Stephanie: After the phonics instruction, we move into a decodable text of some kind. Later in the year, we'll pull those out.

Anna: Tell me about what you do with your enrichment group.

Stephanie: In kindergarten, what that looks like a lot of times is instruction on more advanced phonics skills, and the opportunity to read those skills in context in a book of some kind. Last year at Christmas time, I had a group who had mastered everything in our kindergarten phonics curriculum, we had to brush up on digraphs just a tad, but then they were ready to start on first-grade level skills.

Anna: I know people always ask me what curriculum I recommend, which I don't specifically recommend a curriculum, but I share what I've heard are good curricula. You talked about Heggerty and Kilpatrick. Can you tell us your main program, and then also, are there specific decodable series that you like to use?

Stephanie: Yes, ma'am. Sure thing. We use Phonics First, it's a Brainspring program. It uses Orton-Gillingham methods and I like it a lot. I've seen great success with it. I have started writing decodable books and that's what I use with my kiddos. They match the scope and sequence of our phonics program. I have also used the Flyleaf books. I pick and choose from those because they there's some that work really well.

Anna: It sounds like the way you teach now would be very different than at the beginning of your teaching journey.

Stephanie: 1000%, yeah.

Anna: Can you talk a little bit about the difference you've seen in how kids are progressing, or learning, or maybe also a little bit about their interest in reading, and if you've had any concerns about that? That's a big concern for people who are being told that there's something wrong with leveled books, they're concerned that their kids are just going to be bored. Maybe you could talk about that and how you keep your kids interested during phonics.

Stephanie: We have a lot of fun! I feel like honestly, the structured literacy approach is way more fun for me to teach and for my kids to learn than the balanced literacy approach. We have games, we have songs, we have Play-Doh, and apple sauce. Anytime you can incorporate food into a lesson, kids are going to be excited, so when we are learning the short a says /��/, we are writing A's in apple sauce on our desk. The kids get excited about it, and I think as a teacher, because I'm so much more excited about it, they catch onto that.

If I'm excited, "Whoo, we're excited! We're going to learn A today, or learn C today!" and the confidence that the students have because they're able to read is a huge driving factor in them wanting to read more and them looking forward to small reading groups and looking forward to getting a brand new book and looking forward to coming to school, and saying, "Oh, I can't wait to do this." Because kids know, kids are smart, and you can't fool them.

My own son, I'll use him as an example, he's a kindergartner this year, and I started him with my decodable texts this summer. He can sound out the words and blend and put them together and he's like, "Mom, look at me! Look at me!" He had to call his grandma and he had to read the book to her and his Auntie Nick and read the book to her.

Whereas then the other night we had just a book off the bookshelf and he "read," with air quotes, "read" me the page, and I was just encouraging him for being in a book, "Good job."

And he turned to me and said, "Mom, I didn't read that. I was just using the picture. I just made that up."

And I was like, "Okay," guilty face, I was like, "Well, you didn't. You're right, you're right."

Kids know and they get excited when they're successful. If you're successful, you feel good, and if you feel good about something, you want to do it, and you want to do more of it.

Anna: Yes, exactly. You talked a little bit about the decodables you've written. Can you talk to us a little bit about your TPT store and what you've created, what you are most proud of there?

Stephanie: Oh, sure. Yeah, I would love to. My books are kind of the cornerstone of my store. I've got a level for kindergarten, and first grade, and I've just started on what I call level three, which is more later first grade/second grade books, and then I've started developing small group kits to go with my books.

Basically, if you had the book and you needed your lesson plans and your phonemic awareness activities and your words to practice in dictation, you could grab the kit to go along with the book and you're all set up, you're good to go there.

Something I've learned along the way is that reading in small groups is wonderful, but I have learned that kids need more than just that little bit of reading. Anytime that you can sneak it in throughout your day, even if it's just a sentence here or there, it's great.

The familiar reading we've got as part of our literacy block and then within our phonics instruction, add in a sentence that goes along with our phonics pattern, and it builds each day. Anybody could do this up on their whiteboard, or use Google Slides and type it out for Monday. Depending on your pattern, if it's short A and you're working on C and T you read something like, "The cat ran," and then maybe on Tuesday you could say, "The cat ran to the dog," and then the next day, maybe you're going to change it up and say something else. I like to use different punctuation marks, the kids get SO excited about recognizing and getting to use an exclamation point!

Anna: Oh, that's so funny.

Stephanie: They say, "It's an exclamation point right there!" or a question mark.

They get so excited, so we'll say, "The cat ran to the dog?" they inflect the ending, or they'll say, "The cat ran to the dog!" Just goofy stuff, but it gives them opportunities to map those words in and let those words become sight words. They can read them automatically, which we know helps their fluency and their comprehension and all the things.

The more I can incorporate just simple one minute, two minute, or thirty seconds of, "Let's read this sentence real quick," the better.

Anna: The name of your store is Darling Ideas, is that right?

Stephanie: Yes, it is.

Anna: I will link to that in the show notes so people can find that.

Now, I know a lot of the professional education you've gotten has been provided through your state, but are there books or podcasts or blogs or anything that have been a help to you?

Stephanie: You bet! Well, okay, I love your podcast because every time I listen, I get something that I can take away with me and try the very next day! I think it was a couple of weeks ago, I was listening to your vocabulary podcast about how to incorporate vocabulary, and things like that. So definitely your podcast. I like some of the Facebook groups, "What I Should Have Learned in College" has some good tips. I like to scroll, but I get buried in there sometimes.

Anna: Yes. Yep, you you get sucked in.

Stephanie: Yep, I get sucked in. I also like the podcast "Together in Literacy." That's a good one.

The very beginning of David Kilpatrick's book, his assessments and his drills are amazing, but the very beginning of his book has some really great snippets and take-aways.

Anna: "Equipped for Reading Success" is the book you're talking about. I agree that he is the reason I understood orthographic mapping. It was really hard for me at first. I just kept watching his videos and then it sounds so basic once you figure it out, but that was a new idea for me. He has a really great way of explaining things.

Stephanie: I love it.

TikTok is a great resource for me. Heidi on TikTok, Heidi, I forget her last name, but she's always sharing great snippets. As a busy teacher and a busy mama, I don't always have time to sit down with a text like I used to, so anything that I can listen to and apply. I try to walk every night, and so that's a good 15 to 30 minutes that I can listen to something.

Anna: Yes! Any tips for teachers who are trying to make this change in their schools on how to go about it in a way that's going to help everybody get on board?

Stephanie: Start small. My mom used to always tell me, "An elephant wasn't eaten in a day," same thing as Rome wasn't built in a day. I would not approach people with, "Hey, we've got to overhaul everything. Let's change to structured literacy," and yada, yada, yada, but a teacher next door is more accepting of, "Hey, yesterday, I tried this and it worked really well. You might give it a try with your kids," or, "Hey, I came up with this resource and tried this idea and my kiddos had a lot of fun with it. Maybe you want to try it, too." Definitely start small.

I set a goal for myself and I feel like it's obtainable to try to do something new each week. Some weeks it's a whole lot more than others. Some weeks it may be, "Okay, I'm going to try to implement this strategy for teaching writing," whereas the next week, my new thing might be these cool pointers that I found in the Target dollar bin, but it's just something to try. It keeps it exciting for me, but also I hope my students as well.

Anna: Well thank you so much for sharing. I know people are going to love, especially, the part where you talked about your day and how that looks, and I know they're going to want to check out your store and see the resources you have for making small groups work.

Stephanie: Thank you.

Anna: We'll provide all that in the show notes. Thanks again for reaching out to me, Stephanie.

Stephanie: Yes, ma'am. Thank you for having me. This was fun! I was a little nervous at first, but you made it so easy, and I had a blast.

Anna: I'm so glad Stephanie could join us today, and you can find the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode94. Talk to you next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Stephanie’s TPT storeDarling IdeasStephanie’s recommendationsEquipped for Reading Success, by David KilpatrickTogether in Literacy podcastGet on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post The science of reading in kindergarten appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 19, 2022

How to teach reading comprehension in K-2

Welcome back to our Balanced to Structured Literacy series!

Today we’re tackling a topic that many people think isn’t even part of the science of reading: comprehension.

It feels like phonics get talked about the most – which is probably true. After all, kids must have strong phonics (and phonemic awareness) skills to lay the foundation for reading.

After they get more automatic with those skills, they start to become fluent … which paves the way for comprehension.

But we don’t have to wait until our students are fluent to work on comprehension.

In fact, we build comprehension even before they can read … through whole-class read-alouds.

As a classroom teacher, I had many days where I just grabbed a book and started reading.

(Okay, I admit it, that was most of the time.)

Don’t get me wrong – there’s nothing wrong with grabbing a book to fill a few minutes.

But the interactive whole-class read-aloud is different. It’s planned and purposeful.

And it should be a consistent part of your reading block. It’s the ideal time to build vocabulary and comprehension!

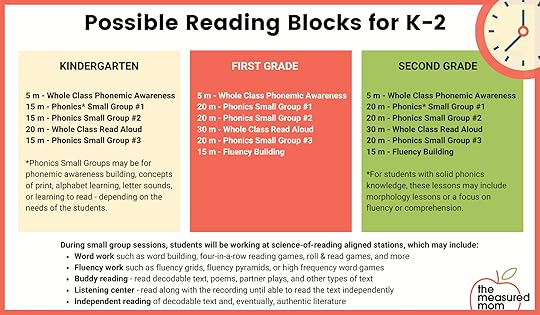

Let’s take a look at some sample schedules and see how that whole class read-aloud fits in.

Remember … the “Whole Class Read Aloud” is when your main focus is vocabulary and comprehension.

As you think about what book to read aloud, consider …What content do you want your students to learn?Instead of choosing a book based on what reading comprehension strategy you want your students to learn, choose a book based on the content you want your students to understand. You can then choose a reading comprehension strategy in service of the content.

(Not gonna lie … I had this backward for a while. I started with a list of all the reading comprehension strategies – predicting, visualizing, you name it – and I tried to find a book that would help me teach a particular strategy. I had it backward!)

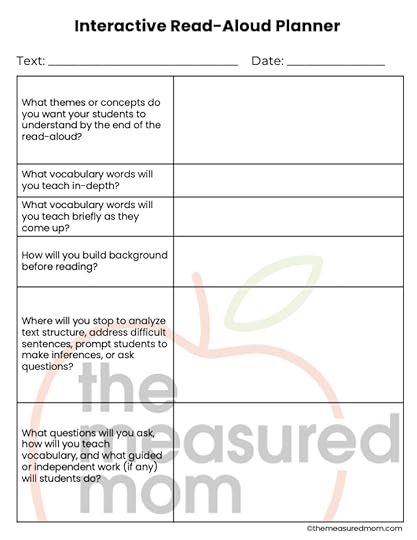

Spend time with the book beforehand, making note of anything that applies:What themes or concepts are most important for your students to learn?What vocabulary words will you teach in-depth?What vocabulary words will you teach as they come up in the text?How will you build background knowledge before reading the book aloud?Where will you stop to analyze text structure, address difficult sentences, prompt students to make inferences, or ask questions?What guided or independent work might students do after the reading?

Spend time with the book beforehand, making note of anything that applies:What themes or concepts are most important for your students to learn?What vocabulary words will you teach in-depth?What vocabulary words will you teach as they come up in the text?How will you build background knowledge before reading the book aloud?Where will you stop to analyze text structure, address difficult sentences, prompt students to make inferences, or ask questions?What guided or independent work might students do after the reading? Before you read, don’t forget to …Introduce the book by reading the title and illustrator.Build background as appropriate.Pre-teach any Tier-2 vocabulary words that students need to know to comprehend the text.As you read …Stop to briefly address vocabulary words.Ask questions and occasionally pause for students to “turn and talk” to a partner.Think aloud as you apply reading comprehension strategies.After reading ..Discuss the story through both low and high level questions.Include a follow-up drawing and/or writing activity. Research tells us that writing about reading helps us comprehend the text better!

Before you read, don’t forget to …Introduce the book by reading the title and illustrator.Build background as appropriate.Pre-teach any Tier-2 vocabulary words that students need to know to comprehend the text.As you read …Stop to briefly address vocabulary words.Ask questions and occasionally pause for students to “turn and talk” to a partner.Think aloud as you apply reading comprehension strategies.After reading ..Discuss the story through both low and high level questions.Include a follow-up drawing and/or writing activity. Research tells us that writing about reading helps us comprehend the text better!Most of all, just get started! You will get better and better at interactive read-alouds the more you do them.

Grab our free planning template!

Click to download

Don’t forget to check out the rest of our Balanced to Structured Literacy series!

Coming August 29 Coming September 5 Coming September 12 Coming September 19 Coming September 26 Coming October 3

The post How to teach reading comprehension in K-2 appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 18, 2022

How to give corrective feedback

TRT Podcast #93: How to give corrective feedback

TRT Podcast #93: How to give corrective feedback093: What’s the best response when students misread a word? How can our response be both efficient and helpful? Find out in today’s episode!

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, I'm Anna Geiger from The Measured Mom, and today we are starting Episode 93 of the podcast. We're going to talk about how to give corrective feedback. This is part of our explicit instruction series.

Remember, explicit instruction is when you are very clear and direct about what you want your students to learn. There is no ambiguity; it's very clear and obvious. Giving good corrective feedback is part of explicit instruction. So let's talk about it using, again, as our guide, Anita Archer and Charles Hughes' book, "Explicit Instruction."

If your students have given the correct response, you can very quickly affirm it and move on, usually I say "excellent" or "good job." That's something we do naturally as teachers.

What gets to be a little harder is when students make mistakes and we're not sure exactly what to say. Let's say that your student is hesitant with the answer. For example, you give them a word to read and the word is "make," and they say, "make?" as kind of a question, they're not sure.

You could say, "Well, let's look at that word," and you do a little bit of reteaching. You say, "Remember, when we have a vowel and a consonant and an E at the end, the E makes that vowel say its long sound. So, I would read this word like this, make. Now you read it, make."

So you see that there's a little bit of reteaching. It was very, very quick, but we look for opportunities to do that.

Let's say you're doing a blending drill and you have the word "rain," and some of your students say, "ran." That would be another time where you could give some reteaching. You could put the word "rain" on the board, underline the letters AI and say, "What sound do the letters AI represent? /��/. That's right. So let's read the word together." Then you point to each grapheme as you read, "/r/ /��/ /n/, rain." Again, a quick reteaching in the case of student error.

If a student is reading orally to you, and you're not doing an assessment, so let's say you're just listening to them read and they make an error on a word, what you're going to want to do is have them reread the word and then read the whole sentence.

I watched a webinar about this which was extremely helpful. It was with Margaret Goldberg, and she's one of my favorite people. In her webinar with Collaborative Classroom, here are the steps that she said to think about when a student stumbles on a word: First you just stop and listen, and you maybe say something about the error. You might say, "Oh, careful! Reread. Sound that word out," and you listen to what they say.

After that, you provide the appropriate corrective feedback. If you're wondering what that feedback should be, here are some things to think about. What did they say? What part of the word did they miss? Why? Then provide the appropriate feedback.

Let's say they're reading the word "plant" and they read "pant." Okay, so clearly the issue there is they're not reading both letters in the blend. So, you could say, "Careful, try that again."

If they still say "pant," you would point to the beginning of the word and you would say, "I see two letters at the beginning here that spell two sounds." You point to each letter as you go, "/p/ /l/ /��/ /n/ /t/. Say the sounds as I point to the letters, /p/ /l/ /��/ /n/ /t/. What's the word?" They say it, and then you say, "Now go back and read the sentence again."

Now, let's say the word includes a phonics pattern you haven't taught yet, but occasionally those words do come up in their reading, right? Let's say the word is "made" and they haven't learned silent E. You would just say, "That word is made. What's the word? Made. Now reread the sentence." So, you just tell them the word. If you think it's something they can learn and you can pre-teach it, go right ahead. But for many kids, just having you tell them the word will be the most efficient way to work through the text.

Now, let's say they're not actually reading to you, but they're answering a question. So you've read a story together - maybe you've read it to them, or they've read a decodable text or a more advanced text to you - and they answer a question incorrectly.

You might say, "What is the problem of the story?" and they're just not getting it. One thing you could do is ask lower level questions to get them to the higher question.

Let's use an example we're all familiar with, The Billy Goats Gruff. You could say, "What is the problem of the story?" and they're not quite sure how to answer it.

You could say, "Well, let's think about this for a little bit. Who are the main characters in our story? That's right, the three billy goats. What do they want to do? Yes, they want to cross the bridge, but why can't they? Right. The troll is in the way. So, what is the problem the goats are having? That's right. The problem of the story is the goats want to cross the bridge, but the troll won't let them."

I want to close this up with a nice summary paragraph in the Explicit Instruction book. It says, "In summary, good corrections are consistently and immediately provided, match the type of error made by the student, are specific in the information they convey, and focus on the correct response. In addition, corrections are delivered in an encouraging tone and end with the correct response."

We don't want to play a guessing game with figuring out the correct answer. We want to quickly and efficiently show them how to get to that answer.

You can find the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode93. Talk to you next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related linksExplicit Instruction, by Anita L. Archer and Charles A. HughesWhy Explicit Instruction? video with Anita Archer on Center for Dyslexia MTSUWhat should we do when a reader stumbles on a word? blog post by Margaret GoldbergGet on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post How to give corrective feedback appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 11, 2022

How to keep your students engaged and listening

��TRT Podcast #92: How to keep your students engaged and listening

��TRT Podcast #92: How to keep your students engaged and listening092: In today’s episode we look at how to elicit frequent responses during your lessons. Not only will this keep your students engaged, but research tells us that it will also help them better master the information!

Listen to the episode here��Full episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom for Episode 92 of the Triple R Teaching podcast, we're so close to 100, that's so exciting! Today we're going to talk about how to keep your students engaged during your lessons by having them respond frequently.

I think many times with our lessons, it's teacher says, teacher says, teacher says, teacher says, teacher says, question, students respond, teacher says, and so on. That's really not what we want, according to Dr. Anita Archer. I've mentioned her before, she's amazing. If you ever watch her workshops where she's teaching you or her workshops where she's teaching students, either way, she's constantly eliciting responses. She's constantly keeping you with her.

Today we want to talk about how you can do that in your classroom.

The reason we want to do this, not only does it keep students engaged and decrease misbehaviors, it also helps students learn more. Research tells us that the more you do this act of retrieval where you are getting the information out of your head and rehearsing it, saying it out loud, you are going to learn more. So we're doing two important things here, we're keeping students engaged in the lessons so it moves more smoothly, and we're helping them master the material.

Let's talk about three kinds of responses: they can be oral, they can be written, or they can be action responses.

What we want to avoid when we're asking for oral responses is the traditional method where we ask a question, students raise their hand, and we call on someone. When this happens, according to Dr. Archer, the teacher ends up teaching the best and leaving the rest.

She tells us that it doesn't make sense to have students raise their hand to answer when you're asking a question that everyone ought to know. If it's a question that reflects what you've taught them, everyone is responsible for knowing that, so you should choose who answers, you shouldn't have students volunteer answers.

The only time it makes sense to have students volunteer is when the question requires them to think about their background or their experience, and their answers are going to be unique to them. If it's an answer that everyone should know, because we've taught it to everyone, then we don't want to call on volunteers.

What we can do a lot of is choral responses where we have all students answer together, and Dr. Archer does this all the time in her workshops, she's a master at it. She usually uses the word "everyone." So she asks a question, she says, "Everyone?" and they answer. You want to have a specific word or action or some kind of signal that your students recognize to know that, oh, my turn to answer, we're all answering together. So hers is "everyone," you could do everyone with your hand behind your ear.

For example, "S-H spells the sound... everyone?" /sh/. Or, "Let's read this sentence together, everyone?" Or, "Five plus five equals... everyone?" When you ask these simple retrieval questions, it works really well to have everyone answer at the same time.

Another way to have students respond orally is through partner responses. Here's a few tips. When you assign partners, make sure that the lowest performing students are matched with middle performing students, not the highest performing or another low performing. If they're with middle performing, then the middle performing students will tend to be more supportive, allowing those lower performing students to actually respond. We don't want someone doing all of the work. Then when you assign partners, call one of them a "one" and one of them a "two," so you can easily say "Ones, turn to your partner and tell them the problem of the story. Begin by saying, the problem in the story was..."

Giving them sentence starters as they begin their responses is really good, because it allows them to articulate their responses a little more quickly, use full sentences, and they're more likely to stay on topic. It also helps them with retrieving that information and formulating their answer, so use sentence starters as much as you think of it.

Let's go back a minute to when I was talking about not calling on volunteers when it's information you expect everyone to know. Instead, using choral responses or just choosing a student at random to answer the question. You might be wondering, well, what do I do when a particular student is daydreaming or just not paying attention and is off-task? How do I get them back?

One common thing that teachers have done is to call on them, right, to basically call them out when they're not paying attention. But when you think about it, that really doesn't achieve very much. It just embarrasses them and doesn't really encourage participation. Dr. Archer tells us that some better ways to bring someone back who is distracted are to move closer to them or to give a directive to the whole group.

So you might say, "Everyone, I need eyes up here," or give them something physical to do like "Everyone, put your finger on the first word of the passage," or "Everyone, show me the heading, the first heading of the passage." Or maybe even have them draw something, like "Draw a circle on your paper. In the circle, write the name of the main character," something like that to get everyone back together. So that was oral responses.

Let's talk about written responses, particularly what's called "response slates." A response slate could just be one of those mini dry erase boards with a marker and eraser. Everyone can have one of those and they pull them out. You ask a question, they write their response, and you give them a signal for flipping them so that you can quickly see everyone's answer and give corrective feedback as needed.

Research shows that the use of response slates or dry erase boards is very useful for a number of reasons. One is that it increases the opportunities for students to respond, and remember, that act of retrieval and then rehearsing the answer by saying it or writing it really improves learning. This provides more opportunities for that. It also increases the number of students who are participating. It increases academic achievement, like I just said, and it decreases off-task behavior.

Finally, let's talk about action responses. Those are when you ask your students to do something physical to keep them engaged in the lesson. This may be just something very, very basic, such as, "I'm going to give you a new vocabulary word. If this is a word you're familiar with and you know it, you could tell me what it means, then put your thumb up right by your chest. If you are sort of knowing the word, put your thumb out to the side. And if you've never heard of the word or you have no idea what it means, put your thumb down. The word is exuberant," and then just watch what they do. You can very quickly see where your students are at as you move forward with your lesson, but it also keeps them engaged and participating.

One thing I like to do is have students act out vocabulary words, which may mean just sitting at their desk and changing their facial expression. For example, "Show me what it looks like when you feel disappointed," or "So and so, could you show us what it looks like to dash across the room?"

So today we talked about three different types of responses that students can give to keep them engaged in the lesson. We talked about oral, written, and action responses. If you want more ideas for each of these, be sure to check out explicit instruction by Anita Archer and Charles Hughes. I will share that in the show notes for today's episode, which you can find at themeasuredmom.com/episode92. Talk to you next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related linksExplicit Instruction, by Anita L. Archer and Charles A. HughesWhy Explicit Instruction? video with Anita Archer on Center for Dyslexia MTSUUsing effective methods to elicit frequent responses – National Center on Intensive InstructionGet on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post How to keep your students engaged and listening appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 5, 2022

How to give systematic phonics instruction

Welcome to the first post in our series about making the switch from balanced to structured literacy!

Today we’re tackling phonics.

Specifically, systematic phonics instruction.

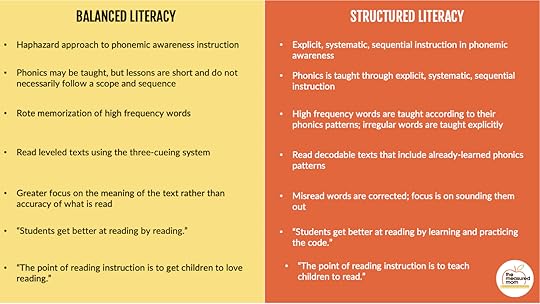

Before we begin, let’s be clear.

I am not saying that balanced literacy teachers don’t teach phonics.

The concern I have is that this instruction is often neither systematic nor explicit.

In other words … a balanced literacy teacher may lack a phonics scope and sequence and typically does not teach each new sound-spelling in a specific order.

Instead, phonics may be taught as it comes up in small group lessons or independent reading.

Even if the opposite is true – the teacher does teach phonics in a structured way – there is often precious little practice with decodable text. (But that will be another post in this series.)

Bottom line? Even if you already teach phonics, keep reading!

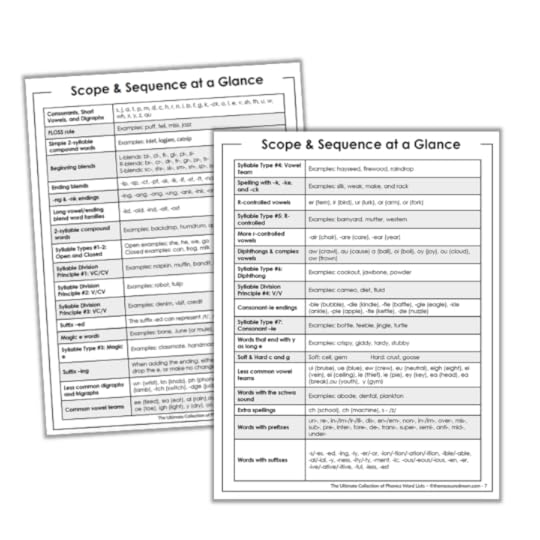

Step 1If you’re ready for systematic phonics instruction, the first thing you need to do to implement systematic phonics instruction is to get a solid scope and sequence. Hopefully your whole school is on board so that you can share the same one.

Research does not tell us what scope and sequence is best. We do know that we should start with simple skills and move to more complex ones.

This is the general order that I prefer:

CVC words (mix in digraphs sh, th, ch & wh)Beginning and final consonant blends (sometimes called consonant clusters)CVCE wordsCommon vowel teamsR-controlled vowels (ar, ir, er, ur, or)Diphthongs and complex vowels (oi, oy, ow, ou, aw, au)Consonant-le words (bubble, cattle, riddle)Words with prefixes and suffixesOf course this general outline doesn’t hit everything.

You can get my free, detailed scope and sequence below.

Free phonics scope and sequence

Sign up for our email list and get this FREE scope and sequence! I created this sequence based on my research, teaching experience, and Orton-Gillingham training. After you sign up, you’ll get a special offer for our Ultimate Collection of Phonics Word Lists. The scope and sequence will arrive in your email shortly.

Step 2

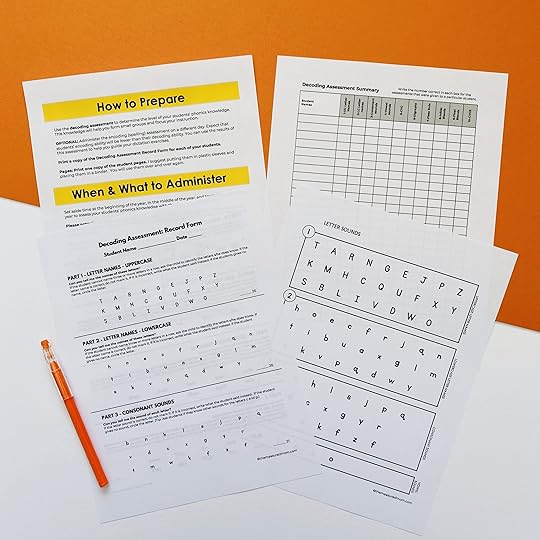

Use an assessment aligned with your scope and sequence to assess your students’ phonics knowledge.

This assessment should be given at the beginning of the year in K-2 and at appropriate times throughout the year. Older students only need to be given the assessment if they are struggling with word recognition.

A good assessment will help you pinpoint where to begin instruction.

1- Make a plan to give the decoding assessment three times a year.

2��� Don���t give the full decoding assessment to each child; instead, administer just the sections that are recommended for the child���s grade level. However, always back up on the assessment or move ahead if it becomes clear that the child���s abilities are above or below grade level.

3��� Break up the assessment as needed. If a child is tiring, it���s best to discontinue rather than to plow through. You want accurate results.

4-Give an encoding (spelling) assessment if desired. It���s likely that your students will read better than they spell (i.e. they will perform better on the decoding than the encoding assessment), so you may not want to form groups based on the encoding results. However, this is valuable information. Encoding (spelling) is often neglected, but it naturally fits into phonics lessons and should be included through dictation exercises.

Grab my free assessment (aligned with my scope and sequence) below.

Free phonics assessment

Looking for a free phonics assessment to help you gauge where your students are at with their phonics knowledge? We’ve got you covered with this comprehensive, yet easy-to-use resource! One teacher wrote, “I’ve used many phonics assessments and lot of them are very good, but this is the best I’ve seen!”

Step 3

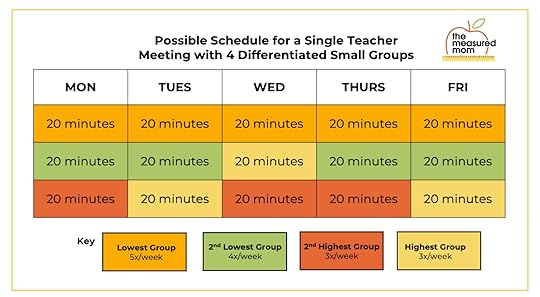

Teach your phonics lessons in differentiated small groups.

Just to be clear, this is my opinion – not a must. The National Reading Panel told us we can be successful with systematic phonics instruction in whole class or small group lessons.

But I know very well how varied that phonics knowledge is in pretty much any classroom. I wouldn’t want to teach kids who are struggling with letter sounds along with kids who are reading multisyllable words.

It doesn’t feel fair to either of them.

Some teachers teach the on-grade-level lesson to the whole class and then differentiate in small groups. Others just teach from where students are at, within the small groups.

They meet with the lower students more often to help them catch up to grade level.

I think it’s best to have no more than four groups, for scheduling purposes.

Here’s what that might look like:

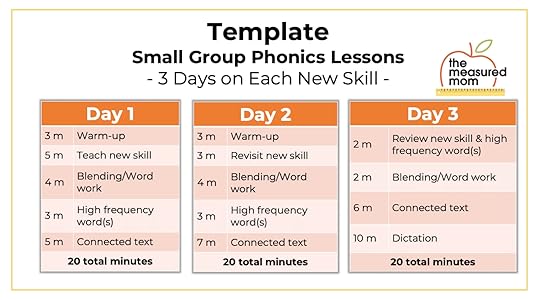

Within your lessons, follow a routine.

Here’s what that might look like:

Step 4

Step 4Make sure your students have plenty of opportunities to reread the connected text (decodable passage or book) on subsequent days so that they can orthographically map the words.

Here are ways to make that happen:

Put the passage or book in their reading bags; it should be the first thing they read before moving on to other books.Have students from the small phonics group reread their passage or book during buddy reading time.Send the book or passage home for extra practice.If time allows, have students begin their phonics small group lessons by rereading text from previous lessons.Keep an eye out for the rest of the posts in our From Balanced to Structured Literacy blog series!

Coming August 29 Coming September 5 Coming September 12 Coming September 19 Coming September 26 Coming October 3

The post How to give systematic phonics instruction appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 4, 2022

The 3 important parts of an explicit lesson

TRT Podcast #91: The 3 important parts of an explicit lesson

TRT Podcast #91: The 3 important parts of an explicit lesson091: Learn the structure of an explicit lesson, and get a free template in the show notes!

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello! Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom for Episode 91 of the Triple R Teaching podcast. This week we are going to look at explicit instruction. Last week we talked about what it is, and today we're going to look at the structure of an explicit lesson.

I talked last week about how, to me, in the past, explicit instruction sounded boring. It sounded like it had to be scripted, and that it was just the teacher talking at the students. Drill and kill. But now I understand that explicit instruction is actually proven by research to be most effective in teaching students academic skills. It's also been shown to be most effective at improving students self-confidence and self-esteem because, as Anita Archer likes to say, success breeds motivation.

If you want to know more about that research, go ahead and check out Project Follow Through, which I will link to in the show notes.

As I mentioned last week, if you really want to know about explicit instruction and the ins and outs of it, I would recommend checking out Anita Archer. She is the queen of explicit instruction, has been in education for decades, and has produced many wonderful workshops and online trainings, and especially her book "Explicit Instruction," which she co-wrote with Charles Hughes. Anytime you're wondering about explicit instruction, you can be sure to learn something when you find Dr. Archer. Today a lot of what I'm sharing is from her book "Explicit Instruction."

When we think about an explicit lesson, we think about three parts. We want to have the opening, the body, and the conclusion. Of course, most of what you're doing is going to be happening in the body of the lesson, but it's important to set it up well.

To start your lesson, you want to have a routine where you get your students' attention. Now, as a teacher, I wish I would've done this, I think it would've saved a lot of transition time and a lot of headaches. It's something you want to teach at the beginning of the year, or the middle of the year if that's when you're going to implement this.

There are many ways to do this. A lot of teachers like to do something called call and response. That's where you say the same thing always, and your students respond the same each time. For example, "One, two," and the students respond, "Eyes on you!" Or the teacher says, "Eyes," and the students say, "Open!," the teacher says, "Ears," and they respond, "Listening!" or something like that. I will go ahead and link to some different call and response ideas in the show notes for this episode so you can pick one, if you're not already doing this, that will work to get your students' attention at the beginning of every lesson that you give.

Once you've gotten their attention, you want to tell them what it is you're going to teach them that day. So maybe you would say, "Today, we're going to learn how to spell the /sh/ sound with S-H." And then, if necessary, you can talk about how this is relevant, and why this is important to know.

Then you're going to move into the body of the lesson, and that's where you want to follow the, I do, we do, you do model. I was recently listening to something by Dr. Archer and she mentioned having coined this phrase, so if I heard that correctly, she's the one who came up with this, probably a long time ago, because like I said, she's been in education for decades.

According to Dr. Archer, the "I do it" is my turn, "we do it" is let's do this together, and "you do it" is your turn. I think that a lot of us assume we're kind of doing this in our lessons automatically, but then if we would actually look closely at our lessons, we would find out, "Oh, actually I'm not really doing that," because that's probably what I would've thought. Then if I would've looked at it closely, I would've seen, "Oh, I jumped right to the we do it. Or for the I do it, I really wasn't very explicit, and I didn't explain it very well."

It's a good practice to think through some of your lessons before you give them with this in mind. I'll provide a free template in the show notes so you can try that for a few lessons just to make sure this is really what you're doing.

So with the "I do it," you're going to model the new skill. Going back to the SH, I could show a card and I say, "These are the letters SH. SH spells /sh/. Here are some words with SH. Watch as I blend the sounds together to read the words." The maybe I would have the word "ship" so that all the students could see it, and I would probably underline the SH as I read it to show them that this makes one sound, "/sh/-/��/-/p/, ship." Then there's another word, maybe "shed," and then I would, again, underline it. "Watch me blend the sounds, /sh/-/��/-/d/, shed." Then I could do some with the SH at the end of the word.

Then I could also model spelling words with SH. "I'm going to spell the word 'shut,' as in 'I shut the door.' The sounds of shut are /sh-/��/-/t/. I'm going to draw three lines and I'm going to spell each sound in a line. So the first sound is /sh/. All right I know that S-H spells /sh/ that goes in my first blank," and so on. After you've done the modeling during which you are engaging your students, it's not just you talking to them, there's going to be some back and forth.

Then you're going to go to the "we do it" where you do these things with them. This might be a set of blending lines, I've written a blog post about that and I'll link to it in the show notes. These start simply. On the top, the first line, the words could be in pairs that differ by just a single phoneme, we call those minimal pairs. So you could have a word like "ship" and "shop" only one phoneme changes, the vowel. Then as you go on, they get more complicated. So then you could have a line of words that have SH in them, but all the vowels are different. The idea is to start simple and move to more complex, but you do those with your students to start. You show them, you point to each sound spelling and have them kind of think it through in their heads, and then altogether they say the word. You could also do dictation together where you dictate a word, but together you spell the sounds. So that's the "we do it" part.

Then, of course, "you do it" is when they get a chance to try this out on their own. Now let's say you're doing an explicit phonics lesson, a small group lesson just like I talked about with the SH, and the lesson is done and you want them to do this on their own. I would recommend doing some kind of decodable book work, where they have to read the words themselves, or maybe reading a list of words, or also doing dictation.

Now just to be clear, if you're teaching a very complex topic the "I do, we do, you do" may not occur all at once. You may spread those out over several days, but they're all included as you're teaching this new skill.

The closing of the lesson is very brief. You're just going to review what you taught your students, and then you may set them free for independent work. So if you are doing that SH lesson in a small group, you might send your students off to centers and have the first activity that they do be a worksheet or more reading of words that have the SH in them.

Normally, of course, your centers need to be review from previously-learned skills, but you may have just one be always a continuation of independent work from that new skill that they learned.

As a review, an explicit lesson should have three parts: the opening, the body, and the closing.

In the opening, you're getting their attention. You're stating the goal of the lesson. Something I forgot to mention at the beginning, sorry about that, is that you want to include review of critical prerequisite skills. That's anything they have to know to understand this new skill, and you're not sure how well they know it, make sure you review it at the beginning of your lesson.

Then, of course, in the body, you're going to be modeling it. Then you're going to have them do it with you with scaffolding and prompting. And then, finally, they're going to do it on their own with you watching.

Finally the closing, you're going to review what they learned, and then you're going to assign independent work.

Again, I will provide a free template in the show notes so you can try this out and see if you're really doing this already and how you could improve the structure of your lessons for the future. You can find the show notes at themeasuredmom.com/episode91. See you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related linksExplicit Instruction, by Anita L. Archer and Charles A. HughesWhy Explicit Instruction? video with Anita Archer on Center for Dyslexia MTSUProject Follow Through50 fun call and response ideasHow to use blending lines (with free editable template)Get on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

Get your free lesson plan template!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

The post The 3 important parts of an explicit lesson appeared first on The Measured Mom.

August 28, 2022

The what and why of explicit instruction

TRT Podcast #90: The what and why of explicit instruction

TRT Podcast #90: The what and why of explicit instructionDoes the phrase “explicit instruction” make you think of “drill and kill”? The good news is that explicit instruction isn’t about boring teaching … it’s about GOOD teaching. Learn exactly what explicit instruction is, and why it’s important for student success.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here with you for Episode 90 of the podcast! This episode is brought to you by the Measured Mom Plus, which is my online membership site for teachers and homeschoolers of pre-K through third grade. The membership is home to thousands of printable resources, as well as no-print resources and workshops that will help you teach reading well. One of our members, Linda, had this to say, "The best purchase I've made as a teacher is the yearly subscription to the membership. It's great to have so many resources and games with engaging, productive activities that students love." To learn more, visit themeasuredmom.com/join.

Today in Episode 90, we're starting a series all about explicit instruction. Before we get into that, we need to talk about the difference between the science of reading and the art of teaching.

As you know, the science of reading is the body of research about how we learn to read and how to best teach reading.

The art of teaching has to do with how we communicate that information to students, because you can know all of the research, but if you don't know HOW to teach it, of course, your students aren't going to learn. So the art of teaching includes things like how you structure your lessons, how you communicate information to students, how you involve them in the lessons, how you give feedback, how you help them stay on task, and how you make sure that they're actually learning it.

Explicit instruction has to do with the how, the art of teaching. For a definition of explicit instruction, we can best go to Dr. Anita Archer, who is really the primary expert on explicit instruction. She has written a wonderful book with Charles Hughes called "Explicit Instruction," and she has given many online presentations about it. Just look for her on YouTube and you'll find lots of helpful workshops.

I'm going to take a clip from one of those and share with you her definition of explicit instruction, "Explicit instruction simply is instruction that is quite direct. It is unambiguous with the goal that the students would get it, would understand it, and would learn."

You may have noticed that Dr. Archer used the word direct in her definition. Sometimes I use the phrases "explicit instruction" and "direct instruction" interchangeably, and I think they're pretty much the same thing, except when direct instruction has a capital D and I.

Capital "Direct Instruction" is actually different. It has the same principles of lowercase explicit instruction because it includes focusing on structured lessons, increasing on-task behaviors, and teaching content, but the difference is that it's actually a method designed by Siegfried Engelmann and Dr. Wesley Becker. In their method, there's a very specific way to teach the lessons and sometimes they're even scripted. So, just be aware that lowercase direct instruction and uppercase direct instruction are two different things.

Now, I'll be honest and tell you that explicit instruction left a bad taste in my mouth for a long time because I associated it with drill and kill, the idea that if you practice and practice something, you will kill a student's love of learning.

Well, I like what Dr. Archer has to say about this, "I constantly hear people say, 'Well, you know, Anita, that is just drill and kill, drill and kill.' But I can tell you, we have no reported incidents of children dying of practice."

So there was actually a big research study that helped us understand that direct instruction, this direct teaching of concepts and skills, is superior to other methods, and it was called Project Follow Through. It's the most extensive educational experiment ever conducted. It began in 1968, it was sponsored by the federal government, and the goal was to determine the best way to teach at-risk children from kindergarten through third grade. The study took about nine years and it included over 200,000 children in 178 communities. They were taught using one of 22 different models of instruction, one of which was direct instruction. The 200,000 children represented a variety of ethnicities, and they were from different socioeconomic backgrounds, so this was a very good study.

What they found in 1977 when they looked at the results was that Direct Instruction blew the other approaches out of the water when it came to academic learning! Students learned much more and much better with the Direct Instruction approach. Also, these students had more self-esteem and self-confidence, even more than the approaches that were actually designed to improve self-confidence and self-esteem.

Dr. Archer likes to say that success breeds motivation. The self-confidence came from actually learning the information, which comes through explicit instruction.

Now, you should know that with this study, we're talking about Direct Instruction with a capital letter, so this was a specific way to teach explicitly, but it was the only method of all of them that really focused on explicit teaching.

By the way, subsequent research found that the Direct Instruction students continued to outperform their peers and were more likely to finish high school and go to college. The research is clear, direct instruction is superior when it comes to helping students actually learn the material.

So, what exactly is included with explicit instruction? We know it's direct, we know it's very clear, but what else? Well, in their book, "Explicit Instruction," Anita Archer and Charles Hughes have a list of sixteen elements of explicit instruction, and I'm just going to look at a few of those with you today.

When you are teaching explicitly, you're going to have organized and focused lessons. You won't be teaching off the cuff, you'll have prepared a lesson, and you'll have a plan for how things are going to go.

The lesson follows through a logical sequence.

You're going to begin your lesson with a clear statement of the goals and your expectations of your students.

You're going to make sure you review previously learned skills and knowledge before starting.

Your lesson may include a step-by-step demonstration.

You're going to have guided and supported practice using the I Do, We Do, You Do Model, which we'll talk about next week.

You are going to require frequent responses. Sometimes I think that when we think about explicit or direct instruction, we assume it's the teacher lecturing from the front of the room and the kids are sitting at their desks bored, but that's really not true because we know that the art of teaching would tell us that for students to really be learning, they have to be active.

Explicit instruction involves lots of responses from the students, and there's a trick for this, how to incorporate those frequent responses in your lessons, and that's why one of our episodes in this series is going to be about keeping students engaged during the lesson.

You want to provide immediate and corrective feedback.

You want to teach at a brisk pace. You certainly want to go slow enough so that students can think and process, but you want it to be fast enough that they're not going to get bored. Anita Archer calls this "moving at a perky pace."

Finally, you want to make sure that you are providing lots of opportunities for practice. Let's hear what Anita Archer has to say about that,

"The students need deliberate practice where they're practicing with a purpose. They need practice that is spaced over time, not all in one session, and they need to retrieve information in that practice. So it's a combination of very explicit instruction with I Do It, We Do It, You Do It, followed with deliberate and spaced practice and retrieval."

So, there you go. This was our first episode in the series, An Introduction to Explicit Instruction. In the show notes for today's episode, you'll find a link to Anita Archer's book, as well as that video on YouTube in which she elaborates more on explicit instruction. You can find the show notes at themeasuredmom.com/episode90. See you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related linksExplicit Instruction, by Anita L. Archer and Charles A. HughesWhy Explicit Instruction? video with Anita Archer on Center for Dyslexia MTSUProject Follow ThroughGet on the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader.

The post The what and why of explicit instruction appeared first on The Measured Mom.

August 14, 2022

From balanced to structured literacy: A conversation with Dr. Wendy Farone

TRT Podcast #89: Teacher education is life-changing: A conversation with Dr. Wendy Farone

TRT Podcast #89: Teacher education is life-changing: A conversation with Dr. Wendy FaroneDr. Wendy Farone has been a classroom teacher, LETRS trainer, educational consultant, and Title 1 reading specialist. Through the years she has learned what really makes the difference … teacher education. Listen in to find out what she wishes every teacher knew about teaching reading.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

I recently had the privilege of doing an interview with Dr. Wendy Farone. She has been in education for thirty years and is just a wealth of information about what it means to teach reading right. I found Wendy when I watched a webinar about dyslexia that she gave for Voyager Sopris and I was struck by how clear and concise she is, as well as her honesty about how she came to structured literacy from balanced literacy. I'm sure you're going to get a lot out of today's episode. We'll get started right after the intro.

Intro: Welcome to Triple R Teaching, where we encourage you to think differently about education by helping you reflect, refine, and recharge. This isn't just about trying something new as you educate those entrusted to your care. We'll equip you with simple strategies and practical tips that will fill your toolbox and reignite your passion for teaching. It's time to reflect, refine, and recharge with your host, Anna Geiger.

Anna Geiger: Hello, everyone. Today in our Balanced to Structured Literacy series, we're excited to welcome Dr. Wendy Farone. She has been in education for thirty years, including twelve years as a classroom teacher in various grades. She was a Title I reading specialist, an education consultant, and a national LETRS trainer, and she also has a PhD in reading. Welcome, Wendy!

Wendy Farone: Thank you very much for having me. I'm excited to talk about this topic.

Anna: Yes, I found Wendy because I was watching a webinar, I can't remember which one, but I think it may have been about dyslexia and I was just struck by how clear and helpful her instruction was, as well as her acknowledgment that it wasn't always how she approached reading.

Can you tell us a little bit about your history with balanced literacy?

Wendy: I sure can. I started in education as an adult learner, so I was about twenty-five, which back in the day was really kind of late to the party, right? When I got my first job, I taught first grade, and it was all literature-based. Students would come in in the morning and they would walk around that little kidney-shaped table and pick up packets of handouts. We would do what the curriculum, or the text in this case, taught us to do and that was read stories and point to things as we read them. There was really no structure. There were songs and such, but there was no direct instruction, there was really nothing explicit.

What I found was that the kids who got it, got it, and the kids who didn't, didn't. I didn't see that as a fault of mine or the curriculum, I saw it as something wrong with the child himself or herself. So that child, of course, was considered for maybe a special education referral because certainly, there could be nothing wrong in my teaching or something wrong in the curriculum that the district had chosen.

Well, reflecting back, I have quite a bit of regret about that because I know better now. Of course, as educators, we have to remember that we are not responsible for what we do not know, but we certainly are responsible once we DO know in implementing those those good things.

I taught that way for many years. Twelve years I was in the classroom, and I watched it go from configuration spelling, where you draw circles around (I still see it, it makes me crazy), rather than actually learning spelling patterns. Then it went into more balanced literacy.

What I find very interesting is the use of the term "balanced literacy," who doesn't want balance in their life, right? We don't want extremes one way or the other, the middle ground is just a perfect place to be. That was a great way to tag people into thinking that this is the right thing to do.

Well, in the year 2000, the National Reading Panel came out and they had checked out a ton of studies, and they weeded out those ones that were good studies and methodology. They found that there really wasn't all that much that was going into the field of education to teachers and into publications that go to teachers, that really taught what the research said about teaching reading.

Therefore, what happened then is that the teachers were taught by universities who didn't understand, and so balanced literacy was the path of least resistance. It was wonderful, it was fun, it was a hoot! We told stories, kids sang songs, and we loved it. It's just, unfortunately, those who couldn't read didn't learn to read, and so that turned into flooding the special education fields, and Title I, and everybody needs a reading specialist.

We kept pointing the finger at the child and that frustrated me like crazy and so I thought, "There HAS to be a better way to do this!" The National Reading Panel, like I said, came out in 2000, and I was intrigued. I kept thinking, "There is a better way," so I decided I had my bachelor's in elementary ed, my master's in reading, a reading specialist certification through the state, and a national certification, and I thought, "Well, maybe the answer lies in the doctoral level. Maybe that's where it is." I went all the way through, got a PhD in reading, and I realized that it's not there, either.

Well, a whole lot of money spent later, I was really no better off than I was in teaching a kid how to read. It was completely frustrating. Where do you go once you've got a doctorate? I mean, isn't that the top of the ladder?

Well, part of the work that I was doing was working for a Department of Ed in the Bureau of Special Education. I was a training in technical assistance consultant. As part of that work, my director brought in LETRS training, which is Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, which is ironically spelled L-E-T-R-S, right?

Now it is nationally and internationally known as the gold-star level learning experience for teachers in the science of reading. I was given the gift of becoming certified as a trainer of LETRS. It was life-changing, because now I know why kids struggle as a reader, and I have enough knowledge around spelling systems, writing systems, decoding, and all of those phonology systems that I can truly teach a child how to read on the back of a napkin.

Anna: Well, that's really cool.

Wendy: Mm-hmm.

Anna: So when you gained your understanding of the science of reading, was that when you were an educational consultant?

Wendy: That's correct.

Anna: Then you had to bring this information into schools where teachers weren't always on board. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Wendy: Oh, my, there are so many great stories around that. Most of it, reflecting back, I think is because nobody likes to be told that what they are doing is not the right way of doing it. There's a resistance there. As a consultant, you have to really be careful. When I would approach a resistant group who have the "yeah, but's" (that sounds good, Wendy. Yeah, but in my district...), what I would have to do in my trainings and my assistance work was to convince them that this isn't working for them, that what's happening now has a 50% proficiency rate.

It's not like they unloaded a bus in the front of the school and said, "All kids who can't read, get in there." Mom and Dad are sending the student with the understanding that these are professional educators and even though it's tough and even though things get in the way, the variables are crazy, we can do this, anyway. In spite of those, we can teach kids how to read, kids with learning disabilities and physical and cognitive disabilities. We can teach them to read anyway.

That's the beautiful thing. Once you empower a teacher to recognize that maybe there is a better way, they willing to investigate. Then they catch the bug and off it goes. I've had many, many, many teachers say to me, "Why didn't anybody teach me this before?"

Anna: Yes. Yeah, I hear that a lot.

Wendy: "How do we not know this?"

Anna: What do you feel has been the most impactful knowledge that you shared with these teachers that really set off the light bulb?

Wendy: Teaching them how the spelling system works, that there IS a reason why there's an E at the end of "cheese" or "house." It's not just there because they had a box of E's sitting around, it's there to keep it from looking plural, because any word in the English language that ends in a single S means more than one, or that it's happening right now, like "walks" means that we're walking right now.

So the E is there to signify that we don't mean more than one "chee," or more than one "hou," it's an indicator. Those types of nuances of the spelling system allow teachers to teach decoding better, and to teach writing better, and to recognize errors in student patterns in spelling and writing. This can indicate to me that they don't understand what a digraph is, or how to blend the "bl" sound together, that's what they're missing. It pinpoints us and engages us directly with what the issue is, instead of saying some broad term like, "He's below, so he gets Title." Why is he below? That's what I want to know.

When I was teaching in balanced literacy and those types of things, it was really kind of hope and, "Well, it sounds like he's reading kind of slow, and when I did a running record, this showed up. Are you sure? Are you positive? Would you stand in front of an attorney and fight that argument?" I've had to do that.

When the time came, I thought, "No, I cannot," but now, put me in front of an attorney and I'll eat his lunch because I know how to teach reading and I know the spelling system and my passion is that every single teacher should know as much as I know about teaching reading. They should have that opportunity to know that much and have that much confidence.

Anna: Well, am I correct that one of your passion projects is teaching about how to help kids with dyslexia?

Wendy: Well, that's true! A lot of times, though, dyslexia is this term that they just give to a child because they haven't been taught well. I caution folks about that. It's become a buzzword and that's a problem. If a child is not able to read, there's a reason why, and I don't care if they're dyslexic or not, we have to do our best to teach them how to read. The world works by being literate. That's your key to a good income, it's your key to a strong outlook on life, all of those things are based on your ability to communicate through print, right?

Anna: Mm-hmm.

Wendy: Very rarely do you have a child who is so severely dyslexic that they are not able to interact with print, very rarely, but sometimes people jump right to that conclusion, "Oh, he has dyslexia, so we are going to put him over there and give him audiobooks." No! Teach him how to read! Put his social studies book on audio UNTIL you teach him how to read. We want him to learn how to read. That's the goal!

Anna: For somebody who maybe can't be LETRS trained at this time, but really wants to learn the things that you're talking about, do you have some special recommendations for them?

Wendy: I do. There's all kinds of books out there now. The Reading League has a ton of resources. Tim Odegard, with Middle Tennessee State University, has a dyslexia center and has a ton of resources there for students with dyslexia. I would offer that you look at the dyslexia site. The International Reading Association is not the dyslexia site, by the way.

Anna: Right.