Anna Geiger's Blog, page 14

May 14, 2023

How to fit phonemic awareness into your phonics lessons

��

TRT Podcast #124: How to fit phonemic awareness into your phonics lessons

This week I’m doing a hot topics collaboration with Melissa & Lori Love Literacy … and it’s all about phonemic awareness! Learn how to fit phonemic awareness into your phonics lessons, and then head over to Melissa & Lori’s podcast on Friday to hear an interview with Heggerty’s literacy consultant.

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello! Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and this week is the last in my series of hot topic episodes in collaboration with Melissa and Lori Love Literacy. This week we're both tackling phonemic awareness. I'm going to talk about phonemic awareness and how to fit it right into your phonics lessons, and later on this week Melissa and Lori are conducting an interview about whether or not phonemic awareness should be done in the dark. I encourage you to check out their episode later in the week.

As you know, that's been pretty spicy in the last couple of years in the science of reading community. There's been a lot of discussion, you might even call it infighting, that has unsettled some people. I think it's good to remember that as members of a scientific community, we expect that what we know will change over time, and that's okay.

We're going to talk very specifically today about how to incorporate phonemic awareness into your phonics lessons, and over at Melissa and Lori Love Literacy, they have an interview in which they're talking about whether phonemic awareness should be done orally or whether it should be done with letters. I'm excited to dive into this with you today.

Now I'm guessing if you listen to my podcast, you're very familiar with Melissa and Lori Love Literacy, but if not, you should know that it's a podcast for educators learning more about the science of reading and high quality curriculum, and they've got some incredible interviews over there, so go check it out after you listen to this one.

We're going to talk now quickly about phonemic awareness in your phonics lessons, but before we do that, let's break down again what phonemic awareness is.

Phonemic awareness is the conscious awareness of individual sounds in words. For example, the word rake has three phonemes, /r/ /��/ /k/, even though it has four letters. The word strength, which has eight letters, has only six phonemes, /s/ /t/ /r/ /��/ /ng/ /th/.

This conscious awareness of sounds is something that we need to teach. The question is how do we teach it? That's where a lot of the controversy has come about.

For many years, we were taught phonemic awareness activities can and should be done in the dark because phonemic awareness is an oral skill. However, we've known from research, for quite a few years actually, that phonemic awareness activities are more powerful when combined with letters. Some people have thought, oh, if you add letters, then it turns into phonics, but that's actually not true. We can combine the two.

So I recommend starting your phonics lessons with a brief phonemic awareness activity connected to the sound of the grapheme you're going to teach. If you're teaching your students that C-H spells /ch/, I would start with an oral-only activity just to get students' ears listening to that phoneme, becoming aware of it. This would be an example of a time where I think an oral phonemic awareness activity makes sense.

If I'm teaching that C-H spells /ch/, I could start like this, "Okay, students repeat these words after me. Chip, chill, Chad, chart, chin. What sound did you say at the beginning of each of these words? That's right, /ch/."

Now you might have little mirrors. Some teachers do this where they have kids pull out little mirrors so they can look at what their mouth is doing when they make a particular sound. I could say, "Take out your mirror. What's your mouth doing when you say /ch/? What are your teeth doing? Put your hand in front of your mouth. Do you feel any air coming out?" or "Put your hand on your neck. Do you feel a buzz when you say /ch/?" And you wouldn't because /ch/ is an unvoiced sound.

Then I could move on. We could do some phoneme blending activities. I could say, "I'm going to say some sounds and put them together to make words. My sounds are /ch/ /��/ /k/. The word is chick. Now, it's your turn. I'll say the sounds, and when I put my hand in front of me like this, say the word together." Just imagine I've got my hand outstretched to the left, my palm facing me, and I move my hand away from myself for each phoneme, and then I place my hand palm up as a signal for the students to say the actual word. I would go, /ch/ /��/ /p/. I wait a second or so, and then when I put my hand palm up, the students could join together and say, "chop". I would do that with a few other words like such, rich, and chug. That would be enough. That's only a couple of minutes, but that's a really good introduction to my phonics lesson.

Then I could say, "The /ch/ sound is spelled with the letters C-H," and then I could connect it to my sound wall, if I use a sound wall, by revealing the C-H spelling. Then I can move into the rest of my phonics lesson, having them read words with ch, having them read blending lines, reading connected text, doing dictation, and so on.

Another way, a very important way, to include phonemic awareness in your phonics lesson is by doing phoneme grapheme mapping and also word building.

You're probably aware of phoneme grapheme mapping, that's been very popular for a while now, but it's this idea of using sound boxes, and then putting the spelling in each box. What you could do is you could have a piece of paper in front of your students with four or five boxes in a row. They're probably only going to need three boxes, but you know it's good for them to have to think about how many they need.

For example you could say, "We're going to segment the word chop, take the chips that you have and move a chip into a box for each sound. Ready? /ch/ /��/ /p/. How many sounds? Three, correct. Now, let's spell each sound."

Then you could have them move those little counters out of the way, and they could write with pencil. You could be doing this on a dry erase board, or they could be using letter tiles. If you have letter tiles, of course, you only want a single sound represented on each tile. They would use a tile that says CH, not the C and the H, the CH tile. Then they would spell each sound using those tiles or writing the letters.

After that, you'll have them put their finger under the word and move it to the right as they blend the sounds to read the word. "Let's say the sounds of that word, /ch/ /��/ /p/. Now, let's blend them together, chop."

So right there we've done phoneme segmenting and blending, right in our phonics lesson. Of course, we wouldn't stop with one word. We'd do a number of words.

As we're doing this, we could also be working on phoneme manipulation. I could say, "Okay, we've done the word chop. What would you have to do to change the word chop to chip?" And then some of them would tell you to move the O out and put in the I, or they would say, change the /��/ to /��/, or you could just tell them what to do. After you've got the word chip, you can say, "Okay, change the /p/ to /n/. Now, read the word." Right there, they've done phoneme manipulation and blending.

As you can see, including phoneme grapheme mapping and word building activities in your phonics lesson is a fabulous way to build phonemic awareness, because phonemic awareness should not be an end in itself.

We don't want to do scads of oral activities in the hopes that that's going to bring our kids to a certain level. Dr. Jeannine Herron has said that phonemic awareness is best learned by pronouncing spoken words and segmenting them in order to spell them, which is exactly what you're doing with the activities that we talked about today.

Thanks so much for listening! You can find the show notes for this episode, which includes a link to Melissa and Lori's episode about phonemic awareness, at themeasuredmom.com/episode124. Talk to you next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related links

Melissa & Lori Love Literacy podcast

Talking phonemic awareness with Dr. Susan Brady

The post How to fit phonemic awareness into your phonics lessons appeared first on The Measured Mom.

May 7, 2023

How to add speech to print elements to your phonics instruction

��

TRT Podcast #123: How to add speech to print elements to your phonics instruction

Curious about speech to print but not ready to take the plunge? These are simple ways to add speech to print elements to traditional phonics instruction.

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello! Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and this week we're going to talk again about print to speech versus speech to print.

Last week I teamed up with Melissa and Lori Love Literacy. They had an interview about speech to print, and I had a quick episode comparing print to speech versus speech to print. Remember that I said that a better way to refer to these approaches is traditional phonics instruction, such as Orton-Gillingham which is print to speech, versus structured linguistic literacy, which includes programs you may be familiar with like Reading Simplified, EBLI, Phono-Graphix, and SPELL-Links.

Today I want to talk to you about what you might do if you're intrigued by structured linguistic literacy, but you're not ready to go all in. It is quite a commitment because it really changes your scope and sequence big time, and it changes your pacing. It's really very different from a traditional phonics approach.

So what can you do if you're not ready to do that or aren't sure you want to, but you want to incorporate some of the really good things in the structured linguistic literacy approach? That's what we're going to talk about today.

One easy change you can make is to say this to your students when they are listening for phonemes and repeating words that have particular phonemes. Instead of saying, "What sound did you hear in each of these words," say, "What sound did you SAY in each of these words?" This helps them associate the sound with something they did with their mouth.

Something else to remember is that you can start having kids build words from a very early age, even in preschool. I just finished reading a book called Making Speech Visible, by Dr. Jeannine Herron, and she talks about having that be the way to reading - by spelling! Actually starting with spelling, giving kids letter tiles and having them build words.

Another thing to think about as you are maybe incorporating elements of structured linguistic literacy is to focus more on the sounds than the letter names. I'm not saying you shouldn't teach letter names when you teach sounds, I personally think that that's a good idea, but when you're doing the building with words, think about referring to the tiles as their sound versus the letter. So if a child has three tiles, M, A, T, instead of saying move the M, you could say, move the /m/, find the /��/, find the /t/, and that can help them really focus on what those letters represent.

Another thing to remember is that you want to start very early with teaching vowels and consonants that can be combined to form words. You don't want to have to wait halfway through kindergarten before kids can start to blend and spell. You want to be doing that very early, and you can. You can start that the second week of school if you are teaching consonants and vowels that can be combined to make words.

Another thing to think about is to use letter tiles versus blank tiles as soon as possible. So as soon as you teach those initial consonants and vowels, the first ones that you teach, put those letter names on the tiles versus doing this without. Because as we know, phonemic awareness instruction is much more effective if we have letters versus just blank tiles.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we should spend very little time on bigger speech sounds, such as syllables. We want to focus on phonemes right from the start, and we learned about that in our episode with Dr. Susan Brady.

So even if you're teaching preschoolers, phonemes are your main focus. I personally don't have a problem with doing syllables and rhyming in moderation in preschool. However, and this is very interesting, The National Reading Panel found the greatest effect size for phonemic awareness instruction when it was taught to preschoolers. So we don't have to wait until kids can count syllables or rhyme words, we can do phonemic awareness very early on. And again, phonemic awareness develops really well when you are spelling words using just a few letters and then blending those sounds, reading the words back.

You want to do a lot of word building and word chaining from the beginning. So not only are you having kids build words, like building the word mat with /m/ /��/ /t/, you're also going to have them switch out letters and replace them with other letters.

You could say, "Let's switch out a sound. You've got the word 'mat,' let's change that word to 'sat.' Which sound do we need to switch?" And then show them that they're going to move the /m/ out and put the /s/ in.

So those are just a few things to think about.

One more thing is to consider the pace of your phonics program. Remember that in structured linguistic literacy, they actually teach quite a few spellings at once. Now, they repeat them over the year, so just because they teach multiple spellings for long O in kindergarten doesn't mean they're not going to review in first grade. Knowing that this works for so many children, I think we don't have to be afraid of introducing multiple spellings at once.

For example, if I'm teaching /��/, maybe I would rather teach just O by itself, an O constant E. But when I'm teaching vowel teams, it probably makes sense to teach a bunch at a time, because some of them are very rare anyway. So maybe I'll teach OA as in soap, OW as in snow, and OE as in toe. I might do all three at once.

So think about that. Think about if you can improve your pacing, because the sooner you get through all the phonics skills, the sooner kids are going to be able to read authentic text.

There's probably a lot more we can say, but I think that's a good starting point.

I hope you'll check out Melissa and Lori's episode from last week so you can learn more about structured linguistic literacy from the experts. And don't forget to head to the show notes, because there I'm going to link to some YouTube videos that will really help you dive deep to see if structured linguistic literacy is something that you want to try. You can find the show notes for today's episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode123. Talk to you next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related links

Melissa & Lori Love Literacy podcast

Talking phonemic awareness with Dr. Susan Brady

Making Speech Visible , by Dr. Jeannine Herron

Teaching Reading with a Speech to Print Approach: YouTube video with Dr. Jan Wasowicz

Speech to Print: Is There a Third Way? YouTube video with Dr. Marnie Ginsberg

Answering Your Questions about Speech to Print: YouTube video with Nora Chahbazi

The post How to add speech to print elements to your phonics instruction appeared first on The Measured Mom.

May 3, 2023

Eliminate summer slide with decodable books that students can read all summer long!

This post is sponsored by Just Right Reader. All opinions are my own. I only promote products I know and love!

Looking for a way to eliminate summer slide … and accelerate reading achievement in summer school and at home?

You can’t go wrong with Just Right Reader’s Summer Take-Home Decodable Packs!

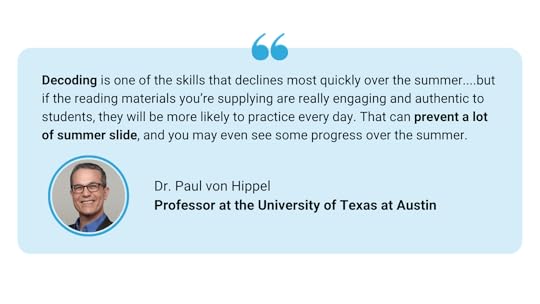

We’re all too familiar with the summer slide … and decoding is the literacy skill that slides most of all. But there’s hope!

Here’s why teachers and students love Just Right Reader’s take-home decodable packs:

Each Summer Pack includes 10 Science of Reading decodables with diverse characters, colorful illustrations, and relatable stories. They���re decodables students are excited to read ��� a perfect way to reinforce the phonics skills students they’ve worked hard to learn all year.The packs are personalized to each student.The books feature diverse characters and engaging stories. The books are gift-wrapped in a backpack … making students excited to get started and to read every day.

The books are gift-wrapped in a backpack … making students excited to get started and to read every day. Each decodable book has a memorable video phonics lesson in English and Spanish, easily accessed by scanning the QR code on the back.Purchase optionsSUMMER PACKSay goodbye to the summer slide with decodables for every week of summerThe pack includes 5 packs of decodable books each … 50 books total per student!SKILL REVIEW PACKFeatures a mixed review of phonics skillsIncludes 1 pack of 10 decodable books per studentIs available in both English and Spanish

Each decodable book has a memorable video phonics lesson in English and Spanish, easily accessed by scanning the QR code on the back.Purchase optionsSUMMER PACKSay goodbye to the summer slide with decodables for every week of summerThe pack includes 5 packs of decodable books each … 50 books total per student!SKILL REVIEW PACKFeatures a mixed review of phonics skillsIncludes 1 pack of 10 decodable books per studentIs available in both English and Spanish

Yes, Just Right Reader includes Spanish decodables as well! These are not translations; they are engaging texts written in Spanish to support all biliteracy models. These books feature diverse characters and relatable situations with short video lessons in Spanish to strengthen caregiver involvement.

GET STARTED TODAY!The post Eliminate summer slide with decodable books that students can read all summer long! appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 30, 2023

Print to speech vs Speech to print: What’s the difference?

��

TRT Podcast #122: Print to speech vs. Speech to print: What’s the difference?��

This week I’m doing a hot topics collaboration with Melissa & Lori Love Literacy … and we’re starting with two different approaches to teaching phonics: print to speech and speech to print. What’s the difference?��

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, here for the first time in a long time with a solo episode. For the next couple of weeks, I'm teaming up with Melissa and Lori Love Literacy. We're going to be looking at some hot topics in the science of reading world.

This week we're tackling speech to print. At the end of this week, you will get a conversation between Marnie Ginsburg and Tami Frankfort with Melissa and Lori, and you'll find that on their podcast.

I'm sure if you're listening to my podcast, you know who Melissa and Lori are. But just in case, they have a fabulous podcast for educators interested in learning more about the science of reading, knowledge building, and high quality curriculum, and they just have so many fantastic interviews. Be sure to check that out and subscribe if you haven't already. They're conducting the interview later this week.

I'm going to compare the difference between traditional phonics instruction and speech to print approaches. That's what we're going to be looking at today.

We're going to start by defining some things. Print to speech and speech to print are two different ways of teaching phonics. Now they encompass more things, but we're just going to focus on the phonics part today.

The problem with those labels is that they also mean other things, right? Print to speech also means decoding, and speech to print also means encoding. Of course every phonics lesson, whether you're print to speech or speech to print, is going to include reading and spelling.

I think that calling it print to speech versus speech to print is very confusing, and it leads some people to just not even listen because they're like, "Well, of course. I do print to speech and speech to print in my phonics program, so what's the difference? Why are we even talking about this?"

Maybe let's phrase it a little bit differently. Let's talk about structured literacy. Structured literacy was coined by the International Dyslexia Association a few years ago, and it emphasizes highly explicit and systematic teaching of all important components of literacy. It's not just phonics, but often when we refer to that, when we say structured literacy, we're often referring to how we teach phonics.

Technically, the print to speech approach and the speech to print approach are both structured literacy. They both fall under that. They both fall under the principles that we know from research. The thing, though, is that structured literacy was coined by the IDA, and the IDA is really more in support of Orton-Gillingham-type approaches. Even here, it gets a little bit muddy.

Instead of calling it structured literacy versus something else, or print to speech versus speech to print, this is how I'm going to distinguish between the two. We're going to call them traditional phonics instruction, which includes Orton-Gillingham, versus structured linguistic literacy, which is what programs you may have heard of follow.

For traditional phonics instruction, including Orton-Gillingham, we may have things like the Barton System and Fundations. Many common phonics programs that you may have used have roots in Orton-Gillingham.

Whereas structured linguistic literacy would be programs like EBLI, Reading Simplified, SPELL-Links, and Phono-Graphix. Those are the two things that we're comparing today.

In traditional phonics instruction, including OG, we begin with print and move to sound. We might start with a card. "This is a G. G says /g/, or G spells /g/."

Whereas with structured linguistic literacy, you're going to start with a sound and then move to print.

With traditional phonics instruction, we teach letters and sounds in isolation first. You may be familiar with a sound deck where you're reviewing all the sounds, there's flashcards, things like that.

Whereas with structured linguistic literacy, they actually teach letters with their sounds in context of words, in word building for example. They might be introducing the letters M, A, T in an actual word with letter tiles. They're actually not teaching the letter names initially. They will focus on those later, but their focus is on sounds. They might say, "Move the /m/ /��/ /t/" instead of saying the names of the letters.

In traditional phonics instruction, we might say something like, "What does the letter say?"

Whereas with structured linguistic literacy, you might say, "What sound do you say for this spelling?"

Traditional phonics instruction may focus on larger units of speech like the syllable and onset-rime, whereas structured linguistic literacy gets right to the phoneme.

Traditional approaches may teach phonics rules, exceptions, syllable types, and syllable division. There's a lot of that in the training that I took for Orton-Gillingham.

Whereas structured linguistic literacy focuses on patterns, no rules. They don't teach things like syllable types and fancy syllable division.

Traditional phonics instruction includes teaching one spelling at a time to mastery. You might be teaching the vowel consonant E pattern, and you really work on that for a while until kids really know it.

Whereas with structured linguistic literacy, you actually teach many spellings at a time and constantly review them and apply them. I guess eventually you would master them, but that's not an initial focus.

For example, if you're teaching spellings for the /��/ sound in structured linguistic literacy, then you would teach multiple spellings right away, even in kindergarten. So if you're teaching /��/, you might teach the letter O, O consonant E, OA, and OW. You might teach all of those at once, and then you just keep reviewing them.

OG is about mastery before moving on, but structured linguistic literacy is about mastery over time, which allows a faster pace.

Then, interestingly, because you are taking more time to master the spellings in OG, you're going to be using decodable text for a longer time.

But with structured linguistic literacy, because many patterns have been introduced sooner, they might call it the complex or advanced code, students can get into traditional text more quickly.

Those are some of the big differences.

A couple of other things we can talk about might be the idea of blends. In traditional phonics instruction, including OG, you teach blends as units. Not that they make one sound, but you teach them together so kids recognize them and say them quickly together.

Whereas with structured linguistic literacy, they don't think of blends as a thing. It's more just... I mean, they do teach CCVC words and CVCC words, but they don't teach blends as a unit.

Another thing is that in many OG programs, red words (as in irregular high frequency words) are taught by things like arm tapping and saying the letter names. So for the word "they", I might tap my shoulder and move all the way down; T-H-E-Y, they.

Whereas with structured linguistic literacy, you teach all words by sounds, think phoneme grapheme mapping.

Perhaps what's getting the most attention and interest from people is that according to structured linguistic literacy advocates, it's much faster than a traditional OG approach and more efficient.

I hope that this was helpful. I think if you listen to Melissa and Lori's episode at the end of the week, you're really going to find out more about the difference, and you can see if it's something you want to look into.

Next week I'm going to talk about how you can incorporate elements of structured linguistic literacy into your teaching, even if that's not the route you decide to go. I personally think there's good to be said for both sides, so next week we're going to talk about how to marry the two a little bit.

You can find the show notes for today's episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode122. Thanks so much for listening, and I'll talk to you again next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Related links

Melissa & Lori Love Literacy podcast

Teaching Reading with a Speech to Print Approach: YouTube video with Dr. Jan Wasowicz

The post Print to speech vs Speech to print: What’s the difference? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 23, 2023

Rethinking reading comprehension with Brent Conway

��

TRT Podcast #121: Rethinking reading comprehension with Brent Conway

I had quite a few misunderstandings about reading comprehension when I was a balanced literacy teacher. Today I talk with Brent Conway, a former principal and current superintendent, about how to rethink reading comprehension.

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from the Measured Mom!

Today we're speaking with Brent Conway, who is currently serving as superintendent at a school district in Massachusetts, and he is passionate about improving literacy outcomes for all students.

Today we had a really interesting conversation about reading comprehension, what we had wrong in our balanced literacy classrooms, and how we need to rethink how we approach reading comprehension. We talk about things like reading comprehension strategies, choosing texts, and assessing comprehension. I know you're going to get a lot out of today's episode, so let's get started.

Anna Geiger:

Welcome, Brent!

Brent Conway: Thank you! Thanks for having me.

Anna Geiger: Can you give us a little background about how you got into education and what you've been doing in the past few years?

Brent Conway: I had started as a teacher, fifth and sixth grade into middle school, and then ended up working as an assistant principal in an elementary school and as a special ed coordinator, and then became a principal at the ripe old age of thirty. I was a principal in Melrose, Massachusetts for a number of years at one of the elementary schools, Lincoln Elementary, and then they had me move to the middle school. Now, over the last five years I've been the assistant superintendent at Pentucket Regional School District in Massachusetts, all north of Boston.

Anna Geiger: Can you help me understand the difference between what a principal is responsible for and a superintendent?

Brent Conway: Well, I mean, the principal's main responsibility is the building itself, the physical building, and the people inside. Principals' jobs, from a pace perspective, are a lot more rapid; everything's in thirty-second intervals throughout the day.

Whereas someone who works in central office, so an assistant superintendent or superintendent, I think has some broader responsibilities that lean into budgeting, program evaluation, and support. Mainly as a central office person, I really only work with adults, for the most part. Although I certainly do make time to work with kids in a variety of ways, because I think that keeps me grounded, for sure.

Anna Geiger: I've heard some talks you've given, and I sort of got the impression that you had maybe a little bit of background in balanced literacy. Can you talk to that a little bit?

Brent Conway: I don't know that I personally had balanced literacy background, maybe a little without really realizing that's what it was. But for the most part, my experience really started as a principal realizing we had a school that was about 50% high needs with declining student performance. And this was in 2007. I was the fifth principal in, I don't know, about seven years or something to that effect. The literacy performance of the students was really poor for a community that should certainly be doing better.

I realized very quickly that no one really had any consistent way of how literacy should be taught. Some data was being used, not much. I don't even think we used the phrase "balanced literacy" or "science of reading" then. We just called it teaching kids to read, and we did it together. As a principal, I did it with teachers together, learning more around what was evidence-based literacy instruction and how to consistently do it.

Then I moved on to a middle school and wasn't engaged in the early literacy process as much, and just assumed all these other school districts were doing what we were doing in the elementary school, which was the science of reading essentially, based on the science of reading.

Then coming to a new school district about five years ago, I realized, oh, no, lots of other people have been using a balanced approach, which was not really effective. They had moved away from a lot of the evidence-based approaches that I had had success with.

Anna Geiger: How does a typical balanced literacy teacher approach comprehension?

Brent Conway: You hear the phrase a lot, "Well, my goal is to make everyone love reading." And I think it's admirable, for sure. I would love for people to love reading too. That would be our goal for kids to love reading. But that's really hard to have as a goal as a teacher or a school district, because number one, you'll never know whether you achieved it or not, and whether a student loves something or not should not really be our objective as a school. Our school, and as teachers, our objective should be, can they? And then, when they need to, be able to.

I was not a kid who loved reading. That was not something I enjoyed. I could, but I just didn't enjoy it. I had other things that I did. I read far more now as an adult than I did. I do enjoy reading, but I'm also particular about what it is that I read, and I don't know that I would say I love reading. And I think that's okay, because I can read and I can read to gain the information that I need, or I can choose to read for pleasure if I have time.

I think that's what we want. We want people to have the ability to make those choices, and you can't push upon your love of something onto someone else. That is up to them to make that choice.

So you hear that a lot, that love of reading, which again, it's hard to say, "No, you shouldn't do that."

But also I think people hear reading comprehension as that's what we're working on, "comprehension." And I think most people in the balanced literacy world, when you think about balance, it's, "Oh, yeah. No, no, phonics is important. We need kids to be able to decode and read, but then we have to work on comprehension," as if comprehension was totally separate from the ability to decode and read fluently. As if comprehension was a thing itself that you do.

So I think most people's view of comprehension was to give kids books that they find interesting so that they can love it, have them practice reading it, and you give them feedback and ask them questions about it. Give them books potentially that they can read that aren't too hard for them, because if it's too hard, they won't love it, and they won't get anything from it. I think that was what you saw a lot from balanced literacy.

You saw kids in different types of books. You saw different levels of books. And they really lacked this direct and systematic and explicit way of helping kids, all kids, actually engage with and learn to read a complex text, and that's really what we needed kids to do. And if you're using levels and you're focusing on comprehension as a single thing, you're not teaching the specific skills and components of that language that kids need. That's what's lacking a lot of times, and people don't necessarily realize that.

Anna Geiger: I think that's a very good description, and I remember when I taught with the balanced literacy way, I did a reading workshop where I did talk to a lot of kids about their books. We would try to do some literature circles and they would talk about the books more. I really didn't know any kind of scaffolds to help kids read more complex texts. I hadn't heard of them myself, the things I've learned about now.

Could you talk to us a little bit about what it even means to access a complex text?

Brent Conway: When we say complex texts, I'm not saying we're going to take War and Peace and have a first grader dive into that and just have them go read and then ask them to tell us about it. That's not what we're talking about. I mean, grade level texts and maybe a little beyond in some spots.

One thing that happened when the common core standards came out, they addressed three major shifts that needed to occur. To me, I always saw that as the three major shifts were the things that gave more definition and description to what was meant by comprehension. Because when you look at Scarborough's rope, and you think about the Simple View of Reading or Scarborough's rope, the language strands and all of those little components, those are the things we need to be directly and explicitly teaching and structuring for students to engage with.

Text complexity was one of those big shifts. Evidence, so acing student response in speaking, reading, and writing in evidence was the second. And knowledge building across all domains. Those were the three really big shifts.

So when you begin to think about that, what does that mean for comprehension? For text complexity, texts can range in complexity for a variety of reasons. Most people automatically go to vocabulary, texts with more advanced vocabulary, words that are content-specific or just Tier 2 words that maybe provide a little bit more specificity to meaning and context. People think of that, and vocabulary certainly is an element that makes texts complex.

Because we've always known a vocabulary as another component, that's not typically the piece that gets missed or tripped up on. It's more around sentence structure, syntax, and having kids understand coherence. When you start getting into texts and they use really unique uses of clauses and so forth, even in early grades, that type of information and complexity can really confuse kids. It's not that they don't actually know what the words are, it's the manner in which they were sequenced or used in a clause or a phrase that prevents it.

I actually have an example. We use Wit & Wisdom here in Pentucket, and I think second grade's a perfect example because we still have kids trying to master that decoding and be really fluent. Yet at the same time we have kids engaged with knowledge-building and complex texts. Some of it is teacher-read, but some of it the students are reading.

So in module two for second grade, it's about folk tales, and Johnny Appleseed is one of the folk tales they end up studying. They read multiple texts around Johnny Appleseed, and in particular, Aliki has this text on Johnny Appleseed, The Story of Johnny Appleseed. I don't know if you've ever seen this one before.

Anna Geiger: I don't think I have.

Brent Conway: So this is the one of the ones. Every kid has this book. It's not a read aloud. Every kid's engaged in this book, and it's very interesting. And this goes to the phrase of placing text at the center or planning from the text.

There is a sentence in here, well, a couple sentences, but on this page right here, this is what it reads, "Johnny did not like people to fight. He tried to make peace between the settlers and the Indians for he believed that all men should live together as brothers."

Now, there is no vocabulary in those sentences on that page that is confusing to second graders. For the most part, kids can decode almost all those words and read it fluently. There's nothing overly tricky except the use of the word "for," F-O-R. And who would've thought that that word would be the word that trips them up?

The phrase was, "For he believed that all men," da, da, da, da, da. Really, use of the word "for" there is just a fancy way of saying "because," and that's not vocabulary. It's a clause. It's a sentence structure. It's syntax. And it's grammar, and really, helping kids to break that down. But if you didn't plan from that text, you would never know why kids are confused after reading that.

That's the type of scaffold that we can do, just pointing out that phrase and that the use of "for" means "because," so these specific things. Then hopefully, kids can end up actually maybe even writing something like that, using that.

Anna Geiger: Something you said that was really useful, something about how we're planning from the text, not the other way around. I think that's a difference, at least in how I used to approach it, where we have this big list of comprehension strategies and so, "Okay, this week we're teaching predicting, so now I need to find five books that will help us practice predicting," versus starting from the knowledge.

That's a little bit easier when you're thinking, "Okay, we're going to start from knowledge. I'm going to read this book, and I want them to know this information, so I'm going to use these strategies to help them figure it out."

How would you approach that with a fiction text?

Brent Conway: So I think you look at what are the knowledge and skills. For instance, our fifth grade, the module they're in, they're reading A Phantom Tollbooth, and that's the core text. It's a pretty complex text, but the knowledge we're looking for, it's not about time travel. That's not necessarily the knowledge we want them to learn. The knowledge is actually about wordplay, and puns, and uses of how an author uses words. That's the knowledge we want them to learn, but we also want them to learn about a narrative text structure and character development. That's the knowledge they're working on.

So if that's what we're working on, I plan from the text about those components, knowing full well that when the book is over, what we're going to ask kids to do is write using evidence from the text, but what we're going to ask them to do is write from a perspective of one of the characters about how something would've been done differently.

So we want them to understand character, because character structure is important, setting, all of those components along with the wordplay because that author chooses those and that wordplay plays into the character's personalities and the interaction of all the characters.

Anna Geiger: So I've recently been hearing a lot about how we can't actually teach comprehension. We teach other things that lead to development of comprehension. Have you heard that? And can you speak to that?

Brent Conway: Yeah, so we have a phrase, Jen Hogan and I, Jen's our literacy specialist. We have a phrase, we call it the "balanced literacy hangover," and it is this lingering effect of all these years of thinking about a strategies-first approach to teaching reading comprehension. That if we practice making inferences every opportunity we get, then kids will just get really good at making inferences, and then they'll be able to make them. If we practice main idea and key details, if we practice these with all sorts of random texts, it's the strategy that gets better.

That's not necessarily true. It doesn't transfer that way. In the baseball study, which people have read about in Natalie Wexler's book, all that sort of makes that apparent. I could read a newspaper article about a cricket match, but I know nothing about cricket. I don't have the background knowledge. I can make inferences. I can summarize the main idea, but I'm going to struggle to use all those strategies effectively to show that I know what this means. It's not that I don't know how to do those strategies. I do. I lack all the other components of language comprehension.

So the "balanced literacy hangover" is when we sort of get focused on that strategies-first approach and we forget what is the purpose of reading? The purpose is either I'm reading to gain knowledge or understand something, whether it's fiction or non-fiction.

I'm glad you asked that example because we're talking about building knowledge around folk tales. It could be building knowledge around civil rights heroes and so forth, and the intent of that is different than the intent of reading a narrative book that's fiction, for instance, where I'm trying to learn about characters and settings and so forth.

So I think that's where that plays in a little bit, and it's different. Reading comprehension is the outcome. It's the outcome of being able to read the words, decode fluently, but then also use your language strands, all of the components, to make sense of what you're reading. And then you have reading comprehension.

That hangover, we saw even as we made these changes with teachers who were used to it. It was a lesson that was supposed to be five minutes on main idea, but it was at the beginning of this whole sequence of days and days of lessons. They were thirty minutes into the lesson, and that teacher was still doing main idea because she said, "The kids didn't understand the main idea."

That's when we realized, "Oh, this is going to be hard for people to step back."

Well, they're not going to know the main idea until you're done with the text. You've got to keep going, and they'll continue to use those strategies.

If you think about inferencing, inferencing really isn't a reading strategy. It's a cognitive skill. We make inferences at birth. Babies start making inferences, for instance. We just apply it to text. So it's not like we have to really teach people how to make inferences. We can help people learn when they have made an inference so they're more conscious of it, more purposeful.

Those are the types of things that we did with that strategies-based approach through a balanced literacy approach. Really, it should be about the content, and the knowledge, and the skills we're trying to achieve.

When you think about writing, you can't write anything you can't say. So when we think about writing, we want students to be able to say, and this goes back to that evidence from the text. We want them to be able to answer it out loud, and then have it transfer to writing.

But if you don't have the language, and the knowledge, and the vocabulary, you're not going to be able to say it either. So all of that is very much related, and it does take a different approach.

Anna Geiger: So I think it can feel maybe a little bit scary, because it's much easier to just check off a list. I taught this strategy, this strategy, this strategy versus the idea of building knowledge and vocabulary that's humongous, and that goes on, of course, forever and ever.

Is there anything you could say to a balanced literacy teacher who thinks, "Well, I want to do this, but this just sounds too much, how do I even get started?"

Brent Conway: Achieve the Core has a great document out, I think it's actually called Placing Text at the Center. It's sort of like a do-this-not-that approach that I think can be really helpful, and it does sort of talk about that moving away from a strategies-first approach.

I think you can begin to do it. I mean, I think ideally, having high-quality curriculum programs that are built for that purpose make it a lot easier. I know there are a lot of folks who are trying to do this on their own in a classroom without that curriculum. They're using the materials they had.

That is actually something from in the beginning when I came here, we were not ready to go buy a new curriculum and we began to just outline, "Well, what does the science say about how we should be teaching, and what we should be teaching?" And I think people tried to do all that work and it was hard work. They were looking for things, trying to put things together. Then we were in a position to make a change and give them the right tools that made it a lot easier.

Even at that, even these curriculum programs that are high quality are not perfect. People have to learn how to skillfully implement. So we do a lot of PD, for instance, Nancy Hennessy's book, The Reading Comprehension Blueprint, if you've ever seen that, is really helping people know how to use the tools like that. Tim Shanahan's work has been great as well.

We basically take that and use examples from Wit & Wisdom to show them how to do this, because some of it we need to scaffold up for some of the teachers too about how do you make this happen? It's curriculum-driven professional development based on evidence-based practices, right?

Anna Geiger: Yeah. So when your teachers are doing it this way versus some of the old ways, what are some changes that teachers can expect to see as they start doing this in the more research-based way?

Brent Conway: I guess it speaks to what screening and assessment datas you are using as well. There are districts who are saying, "We're moving towards a science of reading approach. We're going to teach in this approach, but we still want to use a leveled assessment to ensure students are comprehending text." Those assessments are not reliable in everything. They're not valid and reliable anyways, because they're so reliant upon things that you can't control for, like students' knowledge or understanding of the topic of what they're reading. There's a lot of variability.

To help people understand how to shift, for instance, we did a correlational exercise between the leveled assessments they had and the student's outcome on MCAS, which is our state assessment.

Anna Geiger: Was that the Fountas and Pinnell Benchmark Assessment? Yes?

Brent Conway: That's the one! So it only correlated 20% of the time. It was wrong on four out of five students. I think that was a little eye-opening.

Anna Geiger: Can you explain for people what that means? How it was wrong?

Brent Conway: Yep. So we started by saying, "Well, what is the percentage of students at the end of third grade who are proficient, at grade level or above, on the BAS?" It was like 80%.

Okay, so how come on our state assessment we're 50%? So we knew right away there was a disconnect.

People might say, "Well, it's a different assessment that has different rankings..."

Okay, it's a different assessment, but that's the tool you're using to know whether or not what you're doing is effective and to help you make decisions about how to help kids. And it's not matching up!

I said, "I'll tell you what, I'll correlate it kid by kid." So that's what we did. And I said, "What do you think it correlates as?"

Now the teachers see where sort of the movie's going and it's like, "Oh, probably 60% or something."

I said, "No. Lower." I said, "It's 20%."

They said, "Well, what does that mean?"

It's wrong on four out of five kids! It means that if you identified a student at level whatever the letter is that's at grade level, that is likely to be incorrect as far as a predictor of how they will score on the state reading assessment. In fact, it's only correct on 20% of the kids. One out of five kids have a correct prediction of where their reading outcome is. And it takes an incredible amount of time! Even if you think you have it right, it still doesn't tell you why or what to do to help a kid who isn't on grade level.

So we use an oral reading fluency assessment, we use DIBELS, for instance, K to 6, and I said, "That correlates for us 79% of the time." Nationally, it's about 80% of the time. It's a very strong predictor.

People say, "That's just speed reading."

And I said, "Well, there's more to it than that." However, we know that when students are fluent readers, they are far more likely to be able to comprehend the text that they did.

So these are the things where you get this false sense that students are reading pretty well. So when you ask, "What can you expect to see?" Well, it depends upon what you're using.

Initially, I'm not sure you could measure your results in a leveled assessment and feel like you're actually knowing or seeing anything. In fact, we see a lot of folks who focus early on in K-1 and even into grade 2 to ensure students are reading fluently and building the knowledge that way and they don't see the movement in their Fountas and Pinnell levels.

At the end of the day, what would you expect to see? I think you'll see a lot of student talk. That's what you want to see in your classroom. You want students to be talking about the text, and you want them to be using language and examples from the text.

That goes to when we talk about those three shifts, the complexity. Kids have to talk through some of that and you have to work through it. You want kids to use the vocabulary that's involved with that. You have these richer conversations around the knowledge and the things that they're actually reading about, the topics, and you really experience it that way. That's what we've heard.

When I hear parents come and talk to me and say, "The kids come home and they're talking about this thing they learned about the ocean and this and that." And the parents have to ask, "Is that in social studies class or is that in science class?"

And I say, "Well, no, it's in reading and we're doing ELA!" It's just these rich, rich conversations and the knowledge and the connections that kids make, that volume of reading, and that's the phrase.

When we think about people who become doctors, we ask you to write a dissertation. The first portion of that dissertation is your review of literature. You do this lengthy review of literature to make you an expert in the existing literature on the topic. You become an expert. You gain expertise about reading a volume of information about that topic.

A knowledge-building curriculum that focuses on building that aspect with complex text has kids engaged with topical, volume-of-reading learning.

I think the biggest thing we see too is a move away from things in silos. You mentioned the checklist. I taught grammar today. I had a station for grammar. I had a station for silent reading. I had a station for word work. I had a station for this. It's like you have these things in silos, but things are not connected. That's the piece that's really different. Things really connect more.

I think teachers in a balanced literacy environment were master organizers, fantastic organizers. They had things organized so well. They had this group here, and this station here, and everything is perfectly organized. It's the planning, the purposeful planning, the backwards-by-design planning that was often missing so that things were more connected and purposeful from the text, and that has more connection and authenticity to kids.

Anna Geiger: Well, thank you. That has given me a lot to think about. I know you recommended the Nancy Hennessy book. I've written about that on my website. It's a little tough to get started with, but it's very practical.

Is there anything else that you want to share or things that I should recommend to people who are listening? I know you mentioned that article that I'll link to as well.

Brent Conway: Yeah, the article. Achieve the Core has some fantastic things both on the three shifts themselves, complexity, evidence, and knowledge, those three big shifts. I think when that came out, that really provided more context to what is meant by comprehension. But then also, Placing Text at the Center, that is Sue Pimentel and Meredith Liben, who wrote a fantastic piece on that too. So that is an excellent resource to share.

And a lot of the things that Tim Shanahan has too. He's very generous with his slide decks and availability to sort of get anything he puts up there is a good tool, a good resource.

There's one more, I think, from a writing perspective. It's called, SMARTER Intervention. It's how to teach sentence writing using a research-based approach. I think that is very helpful. There's a blog, and it gives some really good examples, because I think what it does is it connects the idea that writing and reading are a reciprocal process, and we need to teach kids to write at the sentence level, and it connects the grammar. If you're writing about a text, again, all of these things are interconnected.

So I don't teach that nouns are a person, place, or thing. That's a definition. A noun is the who or the what. We don't teach that a verb is the action. What we do is we say the verb is what the noun did or is doing. So you give the meaning, it's the purpose and the function. When you do that in relation to a text as well, it's that reciprocal process. It's how you can break down a complex sentence, and it's how you can get kids to write complex sentences. So those are great tools, because it really is, it's all interconnected. And the more you make it interconnected, the more meaningful, purposeful, and likely to transfer to students it will be.

Anna Geiger: Perfect. Well, thank you. I'll link to that as well. And thank you again for taking time out of your day to talk to me.

Brent Conway: My pleasure.

Anna Geiger: Thank you so much for listening. You can find the show notes for this episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode121. Talk to you next time!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Resources mentioned in this episode

Wit & Wisdom knowledge building curriculum

The Reading Comprehension Blueprint , by Nancy Hennessy

The Knowledge Gap , by Natalie Wexler

The baseball experiment

The Three Shifts (Achieve the Core)

Reading as Liberation: An Examination of the Research Base , by lead writers Sue Pimentel & Meredith Liben

Tim Shanahan on Literacy

SMARTER Intervention

Get on the waitlist for my course, Teaching Every Reader

Join the waitlist for Teaching Every Reader

The post Rethinking reading comprehension with Brent Conway appeared first on The Measured Mom.

April 16, 2023

Teaching word recognition with Dr. Katie Pace Miles

��

TRT Podcast #120: Teaching word recognition with Dr. Katie Pace Miles

120: In today’s episode we discuss exactly what’s happening when children learn to recognize words – teaching tips included!

��

Full episode transcript

Transcript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and today we're continuing our expert interview series!

Today I'm speaking with Dr. Katie Pace Miles, associate professor at Brooklyn College, City University of New York. Her research interests include orthographic mapping, high frequency word learning, reading interventions, and literacy instruction that is grounded in the science of reading. I know you'll enjoy learning how she got into education, about how she did work with Dr. Linnea Ehri, then our conversation about how word-learning works, including how to teach those tricky high frequency words, and finally some programs that she's developed. Let's get started!

Anna Geiger: Hello and welcome to the podcast! Today we have the privilege of speaking with Dr. Katie Pace Miles, who is associate professor at Brooklyn College. If you've seen any of her presentations, she's done a lot of talking and presenting about the concept of sight words, what we have been traditionally getting wrong, and how we can change how we teach sight words. So welcome, Dr. Miles!

Katie Pace Miles: Thank you for having me.

Anna Geiger: Can you tell us a little bit about how you got into education, how balanced literacy was introduced to you, and then how you switched gears very quickly and the education that you got?

Katie Pace Miles: Sure. So I started teaching right after college. I was an elementary major. The school I was at was balanced literacy, and the crazy thing when I look back on it is that there was no curriculum. I was at one of those schools where every teacher made their own literacy curriculum, and so you were pulling from all different resources and things were being handed down and each classroom was doing it in a slightly different way.

For my master's, I went into educational psychology, but it had a really strong teacher training track to it. What was interesting is I came upon this dichotomy where I was learning about cognitive science and educational psychology, but the teacher training part of my master's was training me in balanced literacy.

We had to read The Art of Teaching Reading, and it just never sat well with me. I just rejected it. I remember scanning the book and I didn't know that this was what I would be doing now happen years later. Just in the moment, it just never sat well with me.

I felt like my students really needed more what we now call explicit systematic instruction. I became a reading specialist thereafter. I think I was always drawn to the striving readers and because of that, I just knew for those students, this was not going to work for them.

Anna Geiger: I'm going to insert a little bit there. For those of you not familiar with that book, The Art of Teaching Reading is by Lucy Calkins. It is very fat. It's probably about six hundred pages, and I'll just have to be honest and say that back in the day, I loved that book. I highlighted it up and down. I thought it was so inspirational. I just pictured this perfect class and how I was going to apply everything. I think I was sitting on the beach once reading that book and I loved it.

It's great to hear that you saw through it right away. Looking at the book now, I don't know if I still kept it, sometimes I keep those old books for reference, but I believe out of six hundred pages, there's about six pages that even mention phonics and there's no discussion about explicit teaching. I should go back and see what she talks about for the rest of the book.

But you could see right away there was something wrong with that. Can you talk a little bit more about this disconnect between your master's work and what you were learning in college?

Katie Pace Miles: Sure. So in my undergrad, I had gone to a really strong education program for my undergrad, but the thing that always, always bothered me is these moments of what EXACTLY do I do? What am I exactly supposed to do? I think that might be who I am just as a pragmatic person in these delicious courses.

At the end every time, I'd be like, "What does that mean when you go into the classroom tomorrow?" So that urgency that teachers feel when they hear me talk or anyone else talk, that's exactly who I was sitting in classes.

So I actually decided I wasn't going to do an education master's. I don't want to be extreme, but it just didn't sit well. I kind of wanted to reject a little bit of this, "Let's just talk about theory in education."

Now I was going to college in the early 2000s, and so there was none of this, "Let's do explicit, systematic, and all of that." The science of reading was not a part of my undergrad training in elementary education, and I just felt like I couldn't take it anymore.

I sought out this educational psychology program, and I fell in love with it because it was explaining what happens developmentally, what is happening cognitively when students are learning all different sorts of things. It was not specifically for reading, but I had this passion for teaching reading, so I was able to apply what I was learning in that master's to the children that I was teaching, and it just made so much more sense.

You have very basic things like previewing, reviewing, and then this whole idea of being systematic. This whole idea of developmental windows. That got me right away. Oh, yes, that makes perfect sense.

Having worked with kindergartners through third grade, there are certainly these developmental windows and you can see the bands. Not everyone's at the same point. They're not supposed to be.

I went on to do my PhD in educational psychology as well with Dr. Linnea Ehri. That was the best because obviously Ehri combines educational psychology and cognitive psychology with, very specifically, the development of reading.

Anna Geiger: And just for my listeners, Dr. Linnea Ehri is a huge name in the science of reading community and has contributed some major things including phases of reading and also the concept of orthographic mapping.

So it was a huge and amazing opportunity you had. Can you tell us more about how that worked?

Katie Pace Miles: Oh, it was like a dream come true. So while I was finishing up my master's in educational psychology, I was serving as a learning specialist actually for students in grades 3-5. I was dealing with a lot of students who it seemed to me they weren't getting the instruction they needed in K, 1, 2. Whereas you would hope there wouldn't be as many students needing reading support in 3-5, my caseload was huge. It was overwhelming.

Because I was in an educational psychology program, I came upon Dr. Ehri's research and just glommed onto it right away. It was experimental psychology work. She was manipulating variables with young students in determining whether it worked better this way or that way. Right away I was like, "That's what I need. That is what I've been waiting for."

I was able to translate it. The translation piece I felt was right there. It was like, "Okay, I'm going to try this tomorrow in my classroom." So I started communicating with her and applied and was very honored to receive a fellowship to work with her for five years.

Anna Geiger: Wow. Wow.

Katie Pace Miles: It's amazing.

Anna Geiger: So what did you do during that work?

Katie Pace Miles: So I served as her research assistant, and then I was also her student taking all of her classes. In this fellowship role, they set me up to start teaching at one of the City University of New York campuses. I wound up at Brooklyn College teaching developmental literacy. So as I was learning about all of the research from Dr. Ehri, I was then going to teach in an undergrad situation where these were all pre-service teachers. So it was my duty to translate what I was learning from Ehri to these students. It was just my job simply.

It's not what it is today, like, "Oh, we have to figure out the translation and whatnot." I was just forced to do it. There was no way that I could turn a blind eye to what I was learning in Ehri's classes and then show up on Wednesday to teach and talk about something other than what she was demonstrating that so clearly had mounds, years, piles of evidence behind it.

Anna Geiger: Amazing. Amazing.

I know one of the big things you like to talk about these days, one of the many things, is about sight words and what those really are and how we should approach them. Could you start us off with a proper definition of sight words? I know many people consider those words you can't sound out; you just have to memorize them. There's plenty of websites that still define them that way. How would you define it?

Katie Pace Miles: Well, I don't even use the term sight words. As you learn about the theory of orthographic mapping, you'll understand that the goal is that all words are going to be able to be read by sight because you would've mapped the letter-sound correspondences over time. You would've mapped that and stored that in memory.

That term, sight words, it came from a good place to use it with this subset of words, but it actually is inaccurate. So the words that I think we're all referring to when we say sight words are actually high frequency words.

Then I often like to say those are just words that are used a lot, and this idea that they're all irregular is inaccurate, but you have to look at your list. You have to scrutinize. You have to consider what phonics concepts you've taught so far and then look back at your list and say, "Actually, yeah, this word is now decodable."

So to go back to it, I would say high frequency words are words that are used most often in print, in text.

Anna Geiger: I've had an episode, quite some time ago, about orthographic mapping, but can you again define that for us and tell us how that relates to establishing a sight word vocabulary?

Katie Pace Miles: Ehri's theory of orthographic mapping proposes that there is a glue that is formed between the spelling of a word and its pronunciation, and also the meaning supports that. So it's the spelling, the pronunciation, and the meaning of a word that comes together to be mapped in memory.

Now the glue, as I mentioned at the beginning, and I always go like this because her diagram literally goes like this, this part of orthographic mapping is what most securely stores it in memory. The meaning supports that, but it is critical that when you are learning to read a new word, especially as an emergent reader, you are having a moment where you're analyzing what does the spelling of this word look like? And how does that spelling break out into the phonemes that I need to produce and then blend back together to say the word? Then over time, that glue will be strengthened.

It's not that you're going to do this where you analyze the spelling, map it to the pronunciation, and the next thing you know... Well, for some students that does happen. It's stored. For other students, the students that I'm working with, striving readers, it takes numerous exposures to that word to map it and securely store it in memory so that it can be read automatically by sight. Right? That's the goal.

So all words are going to go through this process and all words, again, the goal would be that you can read it automatically by sight at some point. Maybe it's after the first exposure, maybe it's after the fourth. Maybe for some students it's after the tenth or more exposure.

Anna Geiger: So let's say a teacher is doing the right things, they're teaching phonemic awareness and phonics, they've analyzed the high frequency word, but maybe the two words are "what" and "when" or "what" and "why." And they have a student who just cannot remember them. What tips would you have?

Katie Pace Miles: Definitely taking, as everyone who's listening to this knows, a multimodal approach to this. Sometimes we have the instructional approaches that we do consistently in our classrooms, and we know that for some students, we're going to have to really shake it up.

You can go through different protocols for high frequency words. I would crack out those magnetic letters. I would be counting the phonemes. I would be mapping those letters to those phonemes. You could do that without magnetic letters. You do it with magnetic letters. You bring other resources that you have around the classroom to do that.

Then it would be also your spelling brain. Can you work with students to say, "Hmm, I am seeing that this word is spelled W-H-A-T. How do you think that would be pronounced? /w/-/��/-/t/. Oh, well actually, we have to adjust our brain and say /w/-/��/-/t/ and why does it do that?" And then you would compare, are there other words where the A is making that sound? Just to give it more of a network around that letter making that different sound too. It's very likely that that will help that student to be like, "Oh yeah, it's like in the word..." whatever it is, and then they are creating those connections.

Anna Geiger: So you talked earlier about how meaning is so important to help those glue, and just as a reference to everybody who's not watching this, but listening, Dr. Miles had her fingers laced together when she was talking about gluing the pronunciation onto the letters.

How would you recommend approaching that when it comes to those abstract function words like "of" and "was"?

Katie Pace Miles: Anna, I actually have a research study that I conducted with Ehri a few years ago where we focus solely on function words. Well, I guess not solely. We had one where we were doing function and content words, and what we found really focuses on multilingual students. In the study it was non-native speakers of English, and what we found was that they needed examples of how to use those function words in sentences. They needed multiple examples over time in order to then be able to use that word appropriately.

Then we know from the theory of orthographic mapping that that's just part of the amalgam, as Ehri says. So if you know how to spell it and pronounce it or decode it, and you have that meeting, you're just going to have more clarity. You're going to have a clearer representation of that word in memory.

While we did focus on multilingual learners, I think there's also a lot of students for whom having opportunities to use the function words "of, the, what, why." All of those ones that are all over those high frequency word lists. Having opportunities to use them both verbally and in sentence writing, it's only going to strengthen the representation in memory.

Anna Geiger: So multiple exposures, sentence work, and maybe oral language work with those words.

Katie Pace Miles: Oral language work. Yep.

Anna Geiger: Now there's a lot of kindergarten teachers, maybe first grade teachers, who have a long list of sight words they're expected to teach. Then there's also the idea, which I used to espouse of, starting preschoolers with sight words because it felt easier, right? Because it kind of was to a point. You could memorize twenty words, whereas they might not quite be ready to sound out because they don't have the phonemic awareness skills or whatever.

And yet, this is really counterproductive. Can you talk a little bit about why it's really not a good use of time to memorize these long lists of words?

Katie Pace Miles: It really takes me back to these developmental psychology classes too. It's like time is limited in early childhood. There's only so much instructional time that you have. If we know through the research that the best way to securely store words in memory is through this decoding process, it doesn't make sense to spend so much time on memorization.

That time would be much better spent on letter-sound knowledge in preschool to make sure that you really have strong letter-sound knowledge going into kindergarten. Or there are many preschoolers who are ready for CVC word reading and it's completely appropriate. People are always like, "Oh, it's inappropriate." No, no, totally appropriate to go there.

Once they have that letter's sound, you start, in a really fun way, putting those words together. You can do it actually just with VC words at first, right? At, it. I just think it's really about time and the long-term outcome.

One of the things that I'll add on to that too is about habits. So if children start learning the habit of memorizing words in preschool, and then that's the focus of kindergarten, then all of a sudden we start telling them, "Oh no. Now you need to decode this word." And decoding is effortful. It's hard.

Anna Geiger: Yep. It's hard.

Katie Pace Miles: It's hard work. So it's best to start with that, get that on the ground, and then that's just the way you read words.

Anna Geiger: I was just reading something the other day, and I can't remember what it was, but it was something about how with a class they had teaching "sight words," but once the kids got to a certain number, they were forgetting the first ones.

Katie Pace Miles: Of course.

Anna Geiger: Which makes perfect sense, because if you're just learning it by memorizing it, your brain can only hold so much. Whereas actually, if you've mapped it into your brain by sounding it out, that makes more sense.

What could you say to teachers who are using a decodable book and naturally, of course, there's going to be a word or two sometimes that is not yet decodable for the child or maybe never will be technically fully decodable. How would you recommend they approach that word so the children can actually read the decodable?

Katie Pace Miles: I would hope that the decodable books you're using have limited high frequency words that you haven't taught yet. If that's the case, it's totally fine, right? I think it's okay when you come upon that word to say, "This is the word 'is,' or 'you'."

Anna Geiger: Or "have" or "does." Maybe "does" would be good one. Yeah.

Katie Pace Miles: There you go. And then it's up to the teacher. Does she want to take the teachable moment and break down the word into the sounds and map the letters real quick? Totally, that would be great. You could do it at the end. You could do it before. You could do it before the reading, after the reading. I think that it's a teachable moment where you don't need to require the child to then memorize the word.

Anna Geiger: Yeah. Right. That makes sense.

Katie Pace Miles: So I think there's this concept that if it's a high frequency word, then it has to be memorized, and then we have to make sure that that word has been memorized before we go on to the next. I don't look at it at all, especially if there are forty CVC decodable words in that book. That's your focus! If students can do that, that is such a victory! That's such excellent teaching. The teachers should feel so accomplished with that. Then just do as much mapping for those high frequency words as you can and move on.

Anna Geiger: Exactly, and not stress about it. Because the focus of the book is practicing those sound-spelling patterns that you've taught.

Katie Pace Miles: Absolutely.

Anna Geiger: You have done a lot of other things, including a program called Reading Ready. Can you talk to us about some of the projects that you have and the things that you share with people? I think a lot of them for free?

Katie Pace Miles: Yes, sure! I could talk to you about CUNY Reading Corps and I could talk to you about Reading Ready. Maybe I'll start with Reading Ready.

So I have two children, and my older child was an emergent reader in the midst of the pandemic, and I could not get over the fact that schools were closed and there's this developmental window for children to learn how to read, and my child was entering into it and I just couldn't get over it.

I was thinking about all these caregivers at home and what were they going to do? Also with young children, the remote instruction was not landing with them. They're young children and they're not going to learn how to read in a Zoom room of twenty five other students.

I had been a part of an intervention program called Reading Rescue. It's first and second grade reading intervention. At the same time that this was happening with my own child in the midst of the pandemic, I also saw that more and more students were entering into this. It's supposed to be an emergent intervention, but students were entering it without the prerequisite skills that they needed, and it made a lot of sense.

So I wrote Reading Ready based on what I was doing with my own daughter at home. Reading Ready is a simple to execute program. It has ten lessons. Each lesson has its own explicit systematic phonics instruction. Each lesson, though, so it's not that you just have ten sessions, those ten lessons break out into thirty to sixty sessions. It's a controlled, I call it an intervention, but it's also preventative. You could use this with young children before they need intervention just to make sure they're getting good word analysis work. Or if you have a first or second grader who didn't get this in kindergarten, you may want to use this program.