Anna Geiger's Blog, page 10

December 1, 2023

It’s a giveaway!

To kick off this month, I’m hosting a giveaway for the fantastic book,��7 Mighty Moves,��by Lindsay Kemeny.

This is a wonderful book by a classroom teacher who made the switch from balanced to structured literacy after everything she knew didn’t help her severely dyslexic son learn to read.

The good news is that now he’s thriving – thanks to what she learned and implemented.

In the book, Lindsay shares 7 important moves she made as she transitioned to a more effective way of teaching.

The book is beautiful, inspiring, and informative – I can’t recommend it enough!

Please note: This giveaway is for U.S. residents only.

The post It’s a giveaway! appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 29, 2023

Should students use invented spelling?

Invented spelling has always been a hot topic in the reading world. What exactly is it – and should you allow your students to use it?

First things first.

What is invented spelling?Invented spelling is when students spell words based on the phonemic awareness and phonics knowledge that they have, even if the word is not spelled conventionally.

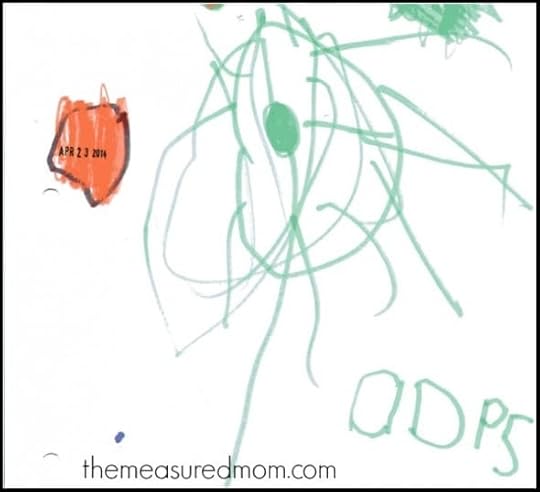

The above octopus, spelled “ODPS,” was drawn by my now thirteen-year-old when he was almost four years old.

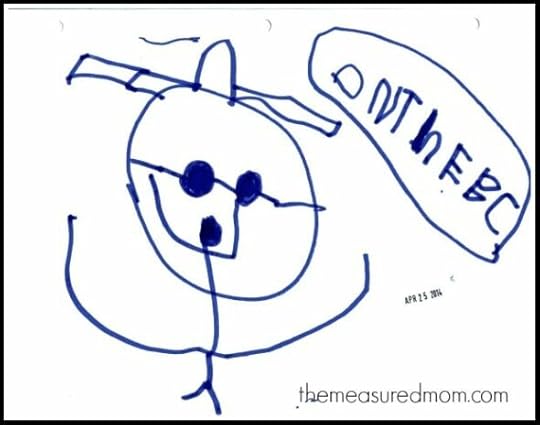

He also drew this picture of Pete the Cat, who is on the beach (spelled “ON THE BC”).

Each of these spellings show that my son knew basic letter-sound relationships but did not hear and represent all the sounds when spelling. He had memorized the spelling of “the” but did not know how to spell /ch/ as in “beach.”

In this way, invented spelling is very useful: It gives us a window into a child’s literacy development.

The argument against invented spellingThe name “invented spelling” has turned some people off, because it sounds like teachers are encouraging students to spell however they’d like, with no care or regard for conventional spelling.

This may be why some have attempted to rebrand invented spelling as “temporary” spelling or even “estimated” spelling. (I like both of these rebrands, by the way).

But invented spelling is not when teachers allow their students to spell words any which way.

The value of invented spelling

The value of invented spellingWhen we remember that spelling is not about memorizing but rather about applying phonology, orthography, and morphology (learn more here), we understand that students need time to learn correct spellings.

Expecting our young writers to spell everything conventionally is unrealistic. It’s also a bad idea to supply every spelling; when students are writing a string of letters that we provide, without any thought as to why they’re writing those letters, they’re not really learning.

In fact, invented spelling gives students a chance to apply the sound-spellings they’ve learned. It also increases their awareness of phonemes in words (Martins & Silva, 2006).

It even gives them decoding practice as they sound out the words while reading their writing.

To be clear: it’s not that we teach our students to invent spellings. Rather, we teach them to apply what they’ve learned from our explicit phonics lessons as they spell words. Since they haven’t learned everything about English spelling, some of their spellings will be invented rather than conventional.

The importance of feedback

The importance of feedbackWe shouldn’t allow our students to use invented spelling with nary a word from us. Instead, we should gently hold them accountable for the spellings they’ve learned and correct their spelling whenever it feels that they will learn from the correction.

When my son who wasn’t even four spelled octopus as “ODPS,” I recognized what a major achievement this was and cheered him on.

On the other hand, when my fourth grader spelled beautiful as “beyutiful,” I gave her a mnemonic for spelling the word correctly: “be-a-U-ti-ful.”

It’s also important to remember that invented spelling is a means to an end. We can affirm our students’ efforts without declaring that their spellings are “correct.” We should always look for ways to push their learning.

Will invented spelling hurt students’ spelling achievement?In 2013, Oulliette et al found that kindergartners who used invented spelling with feedback had similar (even slightly superior) conventional spelling to other students when they reached first grade.

What if students won’t write a word unless you supply the proper spelling?I had a little boy like that; he’s fifteen now. But my refusal to spell every word for him as a little boy often led to tears.

I learned that he did better if I asked him to attempt the spelling, circle it if he was unsure, and wait for me to offer the conventional spelling later in the day.

Another things you can is recopy the correct letters from the child’s spelling and leave blanks for the missed letters; see if the student can correct the spelling.

For example, when my daughter spelled physical as “phyisicle,” I could have written the word this way and encouraged her to try filling in the blanks.

ph_sic_ _

This allowed her to see all the letters she got right while also decreasing the size of the task.

When should students stop using invented spelling?When children have finished the phonics curriculum (usually by the end of second grade), teachers should expect conventional spelling most of the time.

When editing their writing, students can be taught to identify words that might be misspelled and find their correct spellings.

As always, teachers should explain why a word is spelled a certain way whenever possible, For example, if a fourth grader spells militia as malisha, you can share the spelling of military and explain that the words are related. Then guide the student to the correct spelling.

A final tip: When a student asks you for a spelling, always ask him/her to do their best spelling of the word first (even if it’s on a separate piece of paper). This will give you a window into the child’s spelling development, allow you to celebrate all the letters he or she got correct, and give you a focus for helping him or her spell the word correctly – rather than simply naming a string of letters the student will likely forget next time.

Did this post help you clarify what invented spelling is, and why it’s useful? The following articles may also help.

For further reading Explicit spelling instruction or invented spelling? by Tim Shanahan Invented spelling and spelling development, by Elaina Lutz on Reading RocketsReferencesMartins, M. A., & Silva, C. (2006). The impact of invented spelling on phonemic awareness. Learning and Instruction, 16(1), 41-56.

Ouellette, G., S��n��chal, M., & Haley, A. (2013). Guiding children’s invented spellings: A gateway into literacy learning. Journal of Experimental Education, 81(2), 261-279.

Click on the image below to see all the posts in my spelling series!

The post Should students use invented spelling? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

What are the must-know spelling rules?

Welcome back to our spelling series! In this post we’ll discuss spelling rules and which ones are worth teaching.

First, I should note that I am talking about spelling, not reading rules. Some rules, like the FLOSS rule, make perfect sense when it comes to teaching spelling. But I don’t think that we need to explicitly teach this rule for children to read words like hill, miss, and buzz. It’s enough to demonstrate that a double letter is only pronounced once.

At the same time, I believe that phonics and spelling instruction should be aligned in the early grades, so teaching the spelling rule makes sense to me – as long as we understand that children do not need to know this rule to read. It’s useful when children are spelling.

Must-know spelling rulesIn addition to learning basic letter-sound correspondences, children need to know alternate spellings and when to use them. They need to know rules about dropping and doubling letters. They know when to use a silent e. They need to know which letters are “illegal” at the end of English words.

These are the spelling rules and patterns that I think are important for teachers and students to know.

Are there other spelling rules and patterns you should teach?

Are there other spelling rules and patterns you should teach?This is largely a matter of opinion. Here are other resources with a list of rules that is not identical to my preferred list.

Logic of English has a longer list of spelling rules. You can learn about the rules in detail in Denise Eid’s book, Understanding the Logic of English. In her book, Spelling for Life , Lyn Stone has a set of uniquely named spelling rules. (All her books are worth purchasing!)Silver Moon Spelling Rules is a program that focuses on a set of 21 rules. You can learn more by downloading the Progression of Skills on this page. How to teach spelling rules1. State the rule.

In her book with Charles Hughes, Anita Archer explains that rules are generally understood through an If-Then statement.

For example, if a one-syllable word ends with a short vowel and /ch/, then /ch/ should be spelled with tch.

2. Present examples and non-examples.

Examples of this rule include catch, notch, and sketch.

Non-examples include bench (because the word ends with a short vowel plus a consonant before the /ch/) and beach (because the word has a long vowel).

3. Guide students in analyzing examples and non-examples.

For example, ask your students how to analyze the word switch. How is /ch/ spelled in this word? Why?

A nonexample would be the word stench. How is /ch/ spelled in this word? Why?

4. Check students’ understanding of the rule.

One way to do this is to do spelling dictation with immediate feedback. Dictate words that follow (and don’t follow) the rule. After students spell each word on paper or on a dry-erase board, post the correct spelling and discuss it as needed.

Reference Explicit Instruction , by Anita ArcherClick on the image below to see all the posts in my spelling series!

The post What are the must-know spelling rules? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 28, 2023

Should you teach syllable types?

In this post we’ll be looking at the six syllable types and considering the question: Should you teach them?

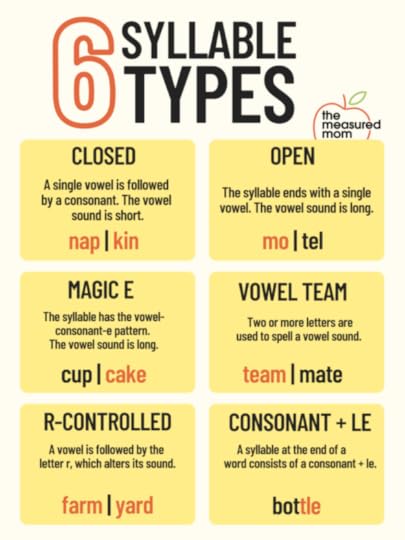

What are the syllable types?Most written English syllables can be organized into six kinds of syllables (called syllable types) based on their spelling.

Because every syllable has a single vowel phoneme (sound), the syllable types are defined by the location and/or spelling of the vowel phoneme.

The chart below defines each type and gives an example in orange.

Variations

VariationsThe “magic e” syllable type is also called the “vowel-consonant-e” or “CVCE” syllable type.

The “r-controlled” syllable type is also called “vowel-r.”

The “consonant-le” syllable may also be called the “final stable syllable.”

And some programs identify a seventh type: the “diphthong” syllable. Others include diphthong spellings with the “vowel team” syllable type.

What are the arguments for teaching syllable types?1. When students learn to recognize syllable types, they can use this knowledge to help read longer words. I like to think of syllable types as opening the door to multi-syllable word reading. If a student can read closed and magic e syllables, they can read cupcake. If they can read r-controlled vowel syllables, they can read further.

2. Some programs (particularly those based on Orton-Gillingham) teach syllable division rules. An understanding of syllable types is necessary for pronouncing each part of the word because syllable types help you know how to pronounce the vowel in each syllable.

3. Syllable types can also help students with their spelling.

For example, if an open syllable (la) is combined with a consonant+le syllable (dle), the d is not doubled.

On the other hand, if a closed syllable (rat) is combined with a consonant + le syllable (tle), a double consonant must result.

What does research say about teaching syllable types?Not much. Programs that teach syllable types and programs that don’t teach syllable types have both shown positive outcomes.

What is the argument against teaching syllable types?1. One reason not to teach syllable types is that they are not always consistent. The schwa, which is the common English vowel, often takes over a spelling in an open or closed syllable.

For example, in the word CACTUS, you would expect the closed syllable TUS to have a short vowel sound. Instead, you hear the schwa.

2. Some argue that syllable types are unnecessary when students are taught flexible syllable division strategies.

For example, when students read the word HABIT, they could break it apart by remembering that each syllable has a vowel. This may end up looking like HA – BIT. Even though syllable types tell us that this word should be prounced hay-bit, students who don’t know syllable types could simply try both the long and short vowel for the “a” in HA, eventually landing on the correct pronunciation.

3. We don’t want to overwhelm students’ working memory.

Some argue that teaching students to learn the names of syllable types is simply too much unnecessary information. We should save their working memory for the task of sounding out words, not storing extra information (like the names of the syllable types) that they don’t need to be successful.

Researcher Devin Kearns has written and spoken about syllable types and syllable division patterns. His conclusion is that syllable division patterns are so inconsistent that it is probably not worth our time to teach them.

As for syllable types, he thinks that teaching the most common syllable types, open and closed, is useful. But he prefers to call them “long vowel syllable” and “short vowel syllable.” He questions whether it’s important to teach the other syllable types.

In this video presentation, Dr. Kearns explains his position and shares a more flexible approach to syllable types and syllable division.

As for me, I think teachers should know the six syllable types and teach students to read each syllable type.

However, I’m not convinced that students need to identify and label syllable types. In my experience, this has been time-consuming and may not give us a bigger bang for our buck than a more flexible approach.

To be clear – here is not much research on this. These are just my conclusions.

What do you think? Do you think it’s important to teach the six syllable types?

For further reading Six Syllable Types , by Louisa Moats & Carol Tolman How Spelling Supports Reading , by Louisa Moats 7 Syllable Types for Reading and Spelling , by Mark Weakland Syllable Types , by Sarah Paul Phonics and Syllable Rules: Do We Need Them? by Nora Chabazi Does English Have Useful Syllable Division Patterns? by Devin KearnsClick on the image below to see all the posts in my spelling series!

The post Should you teach syllable types? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

What do phonology, orthography, and morphology have to do with spelling?

Welcome to the second post in my series about teaching spelling!

Today we’ll be diving deep into the structure of words as I answer this question:

What do phonology, orthography, and morphology have to do with spelling?Sometimes my oldest son likes to take regular English words and pronounce them “correctly.” For example, he’ll say, “The word raining should really be pronounced /r/ /a/ /i/ /n/ /i/ /n/ /g/.

I remember doing the same thing as a kid. And I would have been right, if English spelling was based solely on phonology.

But to be good spellers, students need knowledge in three areas: phonology, orthography, and morphology.

Phonology refers to how we distinguish, order, and say sounds in words.

Spellers use phonology when they break a word apart into its sounds to spell it. For example, when spelling the word mat, students can break the word apart into its sounds, /m/ /a/ /t/, before spelling each sound.

In order to use phonology, students must first have phonemic awareness, the conscious awareness of sounds in words – and the ability to blend and segment phonemes.

Orthography refers to the spelling system of a language.

Phonology only gets us so far when spelling, because English has approximately 44 phonemes (individual speech sounds) but at least 250 graphemes (ways to spell those sounds). There’s not a one-to-one match.

When students have a good knowledge of orthography, they know that ck is not used to spell /k/ at the beginning of a word. They know that the ay spelling for long a only appears at the end of a base word.

It’s important to combine spelling instruction with explicit phonics instruction so that students learn to apply these patterns.

(Here’s my free phonics scope and sequence if you need one.)

But even phonology and orthography aren’t enough.

Morphology refers to the smallest meaningful units of words. These can be base morphemes (sometimes called roots) or affixes (prefixes or suffixes).

A long word can be a single morpheme. For example, the word alligator is a single morpheme.

Other words have multiple morphemes. For example, the word uncomfortable has three morphemes: un, comfort, and able.

When spelling the word roped, students need to use phonology, orthography, and morphology.

They use phonology when they break the word apart into its four phonemes: /r/ /o/ /p/ /t/.

They use orthography when they remember that this word spells long o with o-consonant-e.

They use morphology when they give the word an ed ending instead of using the letter t, because ed shows past tense. (They also using orthography when they remember the spelling rule that the e must be dropped before an ed ending.)

Just when you thought we were done, I want to take a look at one more element: etymology.

Etymology is the study of word origins. It can help explain unusual spellings.

For example, the word ballet is not spelled ballay because its origin is French.

Pharmacy is spelled with ph because it comes from the Greek.

If you or your students are ever curious about the history of a word, check out Etymonline. It’s free!

Final thoughtsUnderstanding the difference between phonology, orthography, and morphology can help you when examining your students’ spelling and determining next steps for instruction.

If a child spells the word JUMP as JUP, you can see that the child needs instruction in phonemic awareness (because the phoneme /m/ is not represented in the spelling).

If a child spells the word KICKED as KICKT, you can see that the child needs instruction in morphology (because the ed ending was not used to spell past tense).

If a child spells the word SKATED as SKAITED, you can see the child needs instruction in orthography: specifically, learning when to use the ai spelling to spell long a.

Learn moreWatch Spelling in a Complex Orthography , with Lyn StoneWatch Spelling: Visible Language to Inform Instruction and Intervention , with Dr. Pam Kastner Tambra IsenbergThere’s a lot more to come in this series! Click on the image below to see all the posts as they are published.

The post What do phonology, orthography, and morphology have to do with spelling? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 27, 2023

Do’s and don’ts for how to teach spelling

Welcome to the first post in my series about teaching spelling!

How to teach spelling: Do’s and don’tsLet’s examine some “do’s” and “don’ts” for teaching spelling in the primary grades.

A scope and sequence tells you what to teach, and when. A quality scope and sequence orders skills from simple to more complex.

DON’T create personalized spelling lists for each student – when you watch for words that students misspell and make these their weekly spelling words. Besides being a management nightmare, this method guarantees that you will miss particular phonics patterns because it doesn’t let you teach in a systematic way.

Following a scope and sequence for spelling is easy when you follow the next DO …

At least through first grade, the words your students are spelling should match the sound-spelling(s) they’re learning in their explicit, systematic phonics lessons.

For example, if you’re teaching students to read CVCE words, their spelling list could include words like grape, dime, stroke, and flute.

(Here’s my free phonics scope and sequence if you need one.)

DON’T include a “word of the day” or words from your social studies and science unit if they don’t match the focus phonics pattern. Yes, children need to know the meaning of amphibian, but this word doesn’t fit in a first grade spelling list.

If you decide to include challenge words for students who can handle them, be sure to explicitly teach how to spell each sound. Don’t present them as strings of letters to be memorized.

I admit that when I was a balanced literacy teacher, my spelling lessons were not very explicit.

I began each week by giving my students words to cut apart and sort. I thought that having my students discover the phonics pattern was better than explicit teaching, so I asked them to figure out the pattern as they sorted the words. (Unfortunately, I didn’t know how strong the evidence is for direct instruction.)

Instead, I should have clearly introduced each new spelling and explained when to use it.

DON’T expect students to discover spelling patterns on their own. The research is clear: students benefit from direct instruction.

When teaching the long o sound, for example, students can learn to spell words with oa, as in goat, and ow as in show. Teaching a single pattern at a time will really slow you down. And yet …

DON’T teach too many spellings at once. Too many basal spelling programs flood lists with more than three spelling patterns. This is overwhelming and probably counter-productive.

Spelling “rules” are also called spelling patterns or spelling conventions. No matter what you call them, these are generalizations about spelling. As for which rules to teach, and how many, this is up for debate. Stay tuned for the “Must-Teach Spelling Rules” post that will be coming later in this series.

Don’t be afraid to teach spelling rules, but make sure that the rules are fairly consistent. Rules like “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking,” is false more than half the time.

If you’re not sure what this means, stay tuned for the next post in this series. Put simply, spelling isn’t one-to-one. We’re not using a single letter to spell each sound. If that were true, phones would be spelled fonz. When spelling this word, we consider phonology and spell each sound: /f/ /o/ /n/ /z/. We also consider orthography when we remember that English has certain spelling conventions; one of these is that one way to spell the long o sound is o-consonant e. We consider morphology when we spell the final /z/ sound with an s, because we know that the letter s can be used to denote a plural form.

DON’T call English spelling “crazy.” When we take into account phonology, orthography, and morphology, we recognize that there are good reasons for why we spell words the way we do.

Spelling dictation, phoneme-grapheme mapping, and word ladders are all meaningful ways to practice spelling. Stay tuned for the final post in this series, which will share a variety of ways to practice spelling words.

DON’T use activities that turn the focus to memorization, such as writing words five times each or rainbow writing.

There’s a lot more to come in this series! Click on the image below to see all the posts as they are published.

For further reading

How Spelling Supports Reading

, by Louisa Moats

How Words Cast Their Spell

, by R. Malatesha Joshi, Rebecca Treiman, Suzanne Carreker, and Louisa C. Moats

Why Spelling is Important and How to Teach it Effective

ly, by Virginia Berninger

For further reading

How Spelling Supports Reading

, by Louisa Moats

How Words Cast Their Spell

, by R. Malatesha Joshi, Rebecca Treiman, Suzanne Carreker, and Louisa C. Moats

Why Spelling is Important and How to Teach it Effective

ly, by Virginia BerningerThe post Do’s and don’ts for how to teach spelling appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 26, 2023

Balancing whole group and small group reading instruction with Dr. Sharon Walpole

TRT Podcast #148: Balancing whole group and small group reading instruction with Dr. Sharon Walpole

TRT Podcast #148: Balancing whole group and small group reading instruction with Dr. Sharon WalpoleDr. Sharon Walpole explains how teachers can balance whole group and small group reading instruction using her free open-access curriculum, Bookworms, and the phonics lessons in her book, How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here from The Measured Mom, and in today's episode I had the privilege of interviewing Dr. Sharon Walpole. She is director of the Professional Development Center for Educators and a professor in the School of Education at the University of Delaware. During her long career, she's done many things and may be best known for co-authoring the book "How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction" with Michael McKenna. She's also the author of the free open-access educational resource called Bookworms. That is a free curriculum online that includes loads of resources for shared reading, interactive read alouds, and more.

In this episode we're going to start by talking about her way of differentiating foundational skills. She actually starts with a whole group spelling lesson on level and then she differentiates based on where students are with their knowledge of phonics skills. Then she also talks about the whole class work that happens within the Bookworms program.

She definitely challenged my thinking in a few ways, as you'll see, so you'll have to let me know what you think of our conversation. You can leave a comment in the show notes. With that, let's get started!

Anna Geiger: Welcome Dr. Walpole!

Sharon Walpole: Thank you!

Anna Geiger: Today you agreed to meet with me to talk a little bit about differentiating reading instruction, especially in the primary grades.

Can you talk to us a little bit about your experience in education and what brought you to where you are now?

Sharon Walpole: Thank you. Yes. I was actually a high school history teacher, if you can imagine, and my students couldn't read very well so I became interested in studying reading. I always thought I would study adolescent literacy, but when I went to the University of Virginia I had the opportunity to work with some really, really fantastic folks in beginning reading and shifted my focus.

Then because I really did want to do my research in elementary school, instead of going to a university job right away, I became a literacy coach in an elementary school to sort of get some street credibility because there's nothing first grade teachers hate more than having a high school teacher tell them what to do. So I learned a lot about how to run a reading program which was much more than just how to teach reading.

I did that work for three years and then I moved to the University of Delaware in 2002, and I've had a really wonderful career at the University of Delaware. I've studied literacy coaching, I've studied the design and evaluation of interventions, and I'm also the author of a K-5 reading curriculum that's open-access called Bookworms.

Anna Geiger: Yes, and we'll talk about that at the end.

So you have co-written "How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction," and I think multiple versions of that have come out. Tell us about where that came from and what the book was written for.

Sharon Walpole: Yeah, actually it's kind of an interesting story and it houses sort of the whole trajectory of the move from guided reading into direct instruction. Mike McKenna, my late partner, he died in 2016 suddenly, and I had worked together for about 15 years.

In the early 2000s, we were working in Georgia with Reading First. We were the state architects of professional learning, so we went to Georgia and we visited schools a couple of times a month.

One of the things that Reading First required was that teachers collect data on foundational skills development, and that was kind of the beginning of DIBELS being very widely used. It was the test that was used in Georgia. At the same time, teachers were required to use a core program that was based in SBRR, scientifically-based reading research, and there was a big movement for that.

So there were these two mandates and they kind of overlapped because the assessments revealed foundational skills deficits, but they didn't tell exactly what to do about them. They were screening mechanisms.

I thought that teachers needed to know not just that kids were at-risk, but exactly what they needed to learn. We actually developed a diagnostic assessment that's very easy to use called the Informal Decoding Inventory.

The other thing that we learned was that the Reading First mandate had a big conceptual hole because back at that time, almost all of the curricula that were on approved lists for SBRR actually had some version of guided reading.

Teachers had a grade level passage or reading that went across the week and then they had three small groups. Typically, those small groups had a guided reading lesson in one of three little books that were related. They had some shared vocabulary, but there was the easy version, the middle version, and the hard version.

That made no sense to me because the easy version, especially in kindergarten, first grade, and the beginning of second grade, was typically a predictable book.

So we had data to show that students were at-risk for their decoding proficiency and for their oral reading fluency, and we had diagnostic data to show exactly what they needed to learn, whether they needed to firm up their letters and sounds, whether specific decoding proficiencies had been mastered, and those are pretty predictable. We know a lot about how decoding develops.

But there was no mechanism for teachers to actually address what kids really needed, so they were in small groups doing something that made no sense at all to me, predicting what the words might be.

So we actually said, let's sub out that small group, that weakest group, and teach some phonics. And so that's how the approach actually began.

There are things about guided reading that were always very attractive to teachers. It's not hard to do. It can be done in a sort of routine regular way with students learning to manage their self-directed work and teachers calling groups.

So we used that structure, but subbed out the content. There was no problem with that in the Reading First world. I know people say that it was very rigid. It wasn't for us, because after we started that in Georgia, we also worked across most of the states on the east coast to try to promote this same idea, and it was very, very well-received.

So that's how it started. It started as a feasible replacement for guided reading instruction for kids who needed to learn to decode.

Anna Geiger: Okay, and then in your book of course you lay out all the different types of lessons that you would have depending on where they're at.

Sharon Walpole: Yeah, we ended up scripting it. We started out with just frames, saying this is what the lesson should contain, and a lot of literacy coaches filled in those frames, but then when I came to watch them, sometimes they were just a little bit off. The scope and sequence wasn't exactly right or the level of difficulty wasn't exactly right, so we just said, well, we can write them easily.

That's how we ended up writing a book that talks about the science of reading and also has a fully-scripted set of lessons for building basic alphabet knowledge, initial phonemic awareness, and then more advanced phonemic awareness, segmenting and blending, and single-syllable phonics instruction.

Anna Geiger: So what is your opinion on the idea that yes, all kids need to know this, but I'd rather teach the grade level skill, according to my curriculum, to everybody at once. It will include the elements of explicit teaching and all that, and then if someone's struggling, then I'll remediate in a small group? Or if they are more advanced, then I'll give them a small group a couple times a week, but we always start with this 20-30 minutes of whole group phonics. Do you have any opinion on that?

Sharon Walpole: I actually think that that's pretty normal and it's a good idea because in the end, it's not feasible for teachers to differentiate everything. What I worry about is how long that whole group lesson is.

Even in Bookworms, that's how we do it. We have a short word study lesson that focuses on spelling and on letter formation in kindergarten, and then on decoding regular and high frequency words in first grade, and then on more mature letter patterns starting in second grade, and then on syllable types starting in third grade. You can still do that whole group phonics instruction for the grade level relatively quickly.

For students who are struggling in that area, they may not be mastering the content that the teacher is teaching because on the continuum of word knowledge they're starting out much lower. However, it doesn't mean they're not learning anything. They might be learning word meaning or they might be building phonemic flexibility, even if they're not quite learning decoding and spelling.

I know that one of the things that you had asked me to think about was whether that's previewing the content so they can learn it later, and I don't think that makes sense. I think they're learning something else about words. Some students do need us to go back to really where they start on that continuum, but I don't think it's reasonable, nor would it be effective, not to have grade level instruction. Because what about the students who are on grade level? They need to keep advancing their knowledge across the grade, and if there's no scope and sequence for grade level word knowledge building, those students won't be served.

Anna Geiger: What about someone who would say, let's give them a diagnostic assessment for phonics and then just put them all in instructional groups based on where they are on the scope and sequence, and that's how we give our instruction?

Sharon Walpole: Well, that's what we do, but we do both. We first have a grade level quick word study lesson every single day, but then also give students a diagnostically-driven small group lesson. I do think that that combination, at least so far in the research on the effects of Bookworms, has been really dramatic, so we do both.

Anna Geiger: Can you help me understand the purpose of the short whole group lesson for everybody?

Sharon Walpole: Yeah, so in Bookworms, it's a spelling lesson.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Sharon Walpole: At its very beginnings in kindergarten and first grade, word knowledge, spelling, and decoding can either be developing together or they can diverge. That happens a lot where students end up doing really well in their decoding, but their spelling starts to drop off.

So what I decided to do was to differentiate phonics instruction to get decoding ahead as quickly as we could, and then have a really systematic attention to spelling instruction. Ideally in a Bookworms school, a student's placement in decoding lessons in small group would be ahead of where their word study spelling instruction is at the whole group.

Anna Geiger: Yeah, that's very interesting because I know a lot of kids might enter kindergarten and first grade reading well above grade level, but their spelling is not at the same place.

Sharon Walpole: Yep.

Anna Geiger: How does that work though if you're doing the whole group spelling, and you have someone who's only reading at CVC level, but the whole group spelling is much further along? How do they do with that?

Sharon Walpole: Not well.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Sharon Walpole: I think that that's important information for teachers and families. I think it's easy to say my students are doing well when I'm instructing them at their just-right level of decoding knowledge, but we need to have a reminder that it's an emergency and that they're well below grade level.

So yes, I would expect students who are in second grade and decoding at the CVC level to do very poorly on grade level word knowledge assessments because they're not at grade level.

Anna Geiger: So in those small groups, would you do any kind of encoding work?

Sharon Walpole: We don't because there's not enough time. It's not that that might not add value, but to me, the costs are too great. Whenever students are in a small group in a classroom-based intervention, the rest of the class is waiting. The longer that time is... So that's just a pragmatic decision that I made, and I might be wrong for sure, but that's why I made it. I want to really protect the amount of time that students are not in teacher-managed work.

Anna Geiger: Right, and it is just a tug of war kind of because you're trying to meet everybody's needs specifically, but you also realize that the other kids aren't getting you at the same time.

Sharon Walpole: That's right.

Anna Geiger: They're just not learning as much. They're in a situation where they may be practicing something for automaticity, but there's no direct instruction there so I know that that is a really hard thing for teachers.

I know some schools have managed this by having a grade level team work together and each teacher is given a group, so they're all getting a good length phonics lesson at once.

For a teacher that is finding that they don't have the support to do a really good small group setup for the Tier 1 instruction and that their main phonics instruction mostly needs to be whole class, a longer whole class lesson, do you have any tips for differentiation within that?

Sharon Walpole: I just don't believe in that. I think you can either teach grade level instruction or you can teach different content based on students' assessed needs, but you can't do both at once. People have tried it. I don't think that that's an ideal design.

People in Bookworms schools differentiate sometimes for students who are struggling by giving them a preview lesson for the word study, but not from the teacher because the teacher has to be managing the whole crew, right? That's if they have intervention providers. Some people have also designed response cards so that the teacher can actually monitor more visually how quickly students are responding because they're touching items on a response card.

I still think that students can be learning different things. For example, one student might actually be building phonemic blending skills while another student is learning how to spell patterns - at the same time. I think that always having phonics and/or spelling instruction have a phonemic content actually is a way that you're both building automaticity for all kids, but also differentiating, inside one lesson.

Anna Geiger: So I'm trying to conceptualize how all this looks day-to-day for the teacher who's trying to figure out how to apply this. Maybe you could just briefly walk us through it. Let's say it's the beginning of the year for a first grade teacher, what does she do first?

Sharon Walpole: I'll tell you how Bookworms is designed. In a Bookworms first grade classroom, the teacher would start with shared reading probably. There's three segments: shared reading, English language arts, and differentiated instruction.

Let's say she starts with shared reading. Shared reading in Bookworms starts out with about 10 minutes of compare and contrast spelling instruction. It's called word study in the lesson plans, and all the lesson plans are open so you can actually look at them. They're open-access.

In the first four weeks of school, the kids are reviewing their letter names and sounds, but then in week five they start comparing and contrasting short vowel word families. Every day they sort words by their sound and then by their patterns once they become more sophisticated. They also do full phonemic analysis of words and they learn to spell six high-frequency words every week.

That word study instruction is fully scripted in the lesson plans, and it lasts about 10 minutes. At the end of that, all the students write a dictated sentence. The teacher says a sentence, the students memorize the sentence, and the students write the sentence. That allows the teacher to have daily progress monitoring in first grade when things are such high stakes for kids.

After that, they have their reading lesson, which starts out with choral reading. Bookworms only uses trade books. The teacher doesn't select them; they're already selected, and they're fully curricularized. The teacher is going to read the day's text segment with students chorally, which means everybody's reading together keeping their voice as best they can with the teacher's voice, and then immediately they reread it in partners. The teachers have partners already set up. The students just move to their partners and they reread that day's segment.

By about October 15th probably, the time that students spend in that repeated reading is about eight or ten minutes.

So they've read with the teacher, and then they reread.

Then on Tuesday, the next day, the teacher reads the next part of the book and the students reread it. They're always reading and rereading so they have a repeated reading intervention every single day. Then they have a discussion with open-ended questions, and the teacher makes an anchor chart of the content of the book. They do that every single day in shared reading.

Then the 45 minutes have elapsed for that instruction, and now it's time for differentiated instruction. At this time, the teacher can see up to three groups for 15 minutes each. When the students are in their groups, either they're getting additional phonics lessons that are based on diagnostic data, or they're getting an additional repeated reading lesson.

While the other students are not with the teacher, they have a written response to the day's shared reading. There's always a question that they write, and then they practice their word study in a workbook. In first grade, they also have handwriting practice.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Sharon Walpole: Those are those two blocks. Then there's a third 45-minute block, in Bookworms at least, that has either units of read-alouds to build knowledge, followed by grammar instruction or writing instruction, composition instruction.

Anna Geiger: Okay. Let's go back to the shared reading time. So these are trade books? These are not decodable texts necessarily?

Sharon Walpole: Right.

Anna Geiger: So can you walk us through that? Because I think some people would be concerned by that and wondering if we're teaching kids to memorize words, or how can they access the words if they don't have the patterns?

Sharon Walpole: So that's a really good question and probably in the first few weeks of first grade, there are a lot of kids who are memorizing the words because the books themselves are short enough for that to happen. But after that, they're just too long so they can't memorize the words.

I think the benefits of repeated reading have been very well-documented in the research literature, but you're right to be skeptical because basically they say that the benefits of repeated reading start when kids are past, in the old-fashioned terminology, about a primer level.

Basically we have to get them up to the primer level as fast as possible for the benefits of repeated reading to kick in. Now our small group phonics lessons do have decodable text to practice, but that decodable text is matched to the decoding instruction. In some ways, for some kids, at the beginning, maybe even the first month of first grade, parts of shared reading might just be a placeholder as we're using the rest of the day to get their skills built enough that they could read at a primer level.

Anna Geiger: What do you see as the learning goals or the benefits of the shared reading time?

Sharon Walpole: It builds community, that's one, and motivation for sure. Actually, I've been amazed at how much it builds student motivation to read, but that's just frosting. The real benefit is kids building automaticity with a wide range of words. I think that there are special educators who will disagree with me and say that all the reading has to be controlled, but that just never ends up intersecting with natural language text in my view.

I put natural language text in front of kids, but with this intense scaffolding of choral reading. Students do learn words, they learn a lot of words, just by reading them successfully several times.

I'm influenced by the work of David Share, and one of the things that he's argued that really resonated with me is that words are in a sort of gauge of known. They go from unknown to fully known. The number of times kids saw a specific word, or a word with a specific set of features, differs by the individual and brings a word to known.

So I think that this repeated reading intervention, even at the beginning of first grade, is building the corpus of sight words in a child's lexicon. We're addressing it very systematically with a spelling continuum, with a decoding continuum, and with repetitive reading in natural text.

Anna Geiger: This is so interesting because I know that there's not a ton out there in research about decodable text, and then there was also a meta-analysis and their conclusion was that we shouldn't limit kids to decodable text. So you're basically showing us a way to scaffold other text reading.

I think it's still a little hard to wrap my brain around because there's so much about automaticity at the word level and achieving that before you move kids into these more authentic texts. Do you have anything to say about that?

Sharon Walpole: Kids are capable of learning a lot more than we think they are, especially if we're providing a really engaging environment and a lot of scaffolding, which is what Bookworms provides. They're also able to build a literate community, even in a first grade class, where kids actually collaborate to solve reading problems.

Of course other people would say, well that's what they do in a reading and writing workshop, but that's actually also what they do in science of reading-based classroom. As long as you've taken time to build community and also as long as you've proven to kids that they're going to learn to read, they're going to be able to participate every single day and they're going to do things that are both interesting to them and challenging, and they're going to do them in community.

Anna Geiger: So to someone who would say any choral reading type of exercises or fluency-building type of exercises for early readers should be... Let's say they're doing reader's theater and they'd say, well, it should only be decodable readers theater. That is a lot of what I hear. Can you respond to that? I think you would disagree with that, right?

Sharon Walpole: Yeah. I've never actually heard that ever. Reader's theater can't be with decodable text. That's not what readers theater is so I don't know what those people are talking about.

Anna Geiger: It would be people who believe that we shouldn't... There are people that are working hard to understand the research believing that when kids start reading, they orthographically map words by matching the phonemes to the graphemes and actually sounding it out, and if we're giving them a lot of words they can't sound out, then what exactly are they doing?

Sharon Walpole: Yeah. Okay. I hear you now. What exactly are they doing is sometimes they are actually processing words more holistically when they're embedded in natural language text. There's no way around that, of course, that's what they're going to do. But some of those words will be processed during that time with enough depth to actually build them into the lexicon, not all of them.

Maybe the bets I'm trying to hedge are that we can teach decoding systematically and that's going to build word knowledge. We can teach spelling systematically and that's going to build word knowledge. We can also engage kids in repeated reading and that's going to build word knowledge too. So two of them are along very predictable lines of development and one is out in the wild.

Anna Geiger: Okay. So I know in your lessons you have decodable sentences, and then we have this other time that they're doing this other reading, this choral reading with scaffolding. Some of those words they are sounding out because they have the knowledge to do that, but we're also giving them access to a chance to build prosody and build knowledge and community and see patterns in words so that eventually, like you said with David Share, when you have some phonics knowledge, you teach words yourself. Thank you for walking me through that.

Sharon Walpole: Maybe I'm just actually trying to give kids the opportunity to come to that time when they're ready. You know what I mean? To be engaged in this really, really rich word world in Bookworms. I actually think it's fine for some students to be in the same world but learning different things at the same time. Maybe in some ways, that's the definition of differentiation.

Anna Geiger: Yeah, that's very interesting.

Sharon Walpole: But it's not because of what the teacher's doing to make it different; it's because of what the student's bringing.

Anna Geiger: Yeah, I've never thought of it that way. Very interesting. Well, thank you.

Well thank you so much for sharing how Bookworms works, and of course I'll link to that in the show notes and to your book.

Is there anything else you want to share about your work or things that you'd like people to find from you?

Sharon Walpole: I really would love people, especially people who use the "How to Plan" book because they have experienced a trust in what Mike and I together learned about how to build word knowledge, to look at the full curriculum to see how we can expand that idea to all the skills that kids need to be successful at grade level. It's easy to sign on, to open up resources, and get access to the lesson plans that are free. All you have to do is buy the trade books that go along with them.

Anna Geiger: Well, thank you. I know I've sent many people especially to your interactive read alouds there because they're just so well laid out the vocabulary is taught so nicely, and I'll make sure everybody can find all that. Thank you so much for joining me.

Sharon Walpole: Thank you!

Anna Geiger: Thank you for listening. You can find the show notes for today's episode at themeasuredmom.com/episode148. Talk to you next time!

Closing: That's all for this episode of Triple R Teaching. For more educational resources, visit Anna at her home base, themeasuredmom.com, and join our teaching community. We look forward to helping you reflect, refine, and recharge on the next episode of Triple R Teaching.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Resources from Dr. Sharon Walpole How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction Free Bookworms K-5 Reading and Writing curriculum

Looking for structured literacy resources?

Our membership has fluency pyramids, poems, and more – not to mention hundreds of resources for teaching letter sounds, phonics concepts, and more!

CHECK OUT OUR AFFORDABLE MEMBERSHIP HERE!

The post Balancing whole group and small group reading instruction with Dr. Sharon Walpole appeared first on The Measured Mom.

How to teach summarizing in the early grades

This is the final episode in our series about reading comprehension strategies! Let’s talk summarizing.

What does it mean to summarize a text?When you summarize a text, you give a brief statement of the main points.

Why should students learn to summarize?Summarizing goes hand-in-hand with comprehension monitoring and is a powerful strategy for improving comprehension (National Reading Panel, 2000).

Students should start with oral summaries and gradually progress to written summaries, since we know that writing about their reading improves students’ comprehension (Graham & Hebert, 2011).

What’s the simplest way to teach summarizing for the early grades?

I recommend the paragraph shrinking strategy from Fuchs & Fuchs (2005). This can be done orally after a whole class read-aloud or in pairs after partner reading.

(It’s not just for the early grades, either … you can use this strategy through high school!)

[image error]How to teach paragraph shrinking1. Introduce the strategy.

Today you will learn a strategy called Paragraph Shrinking. After I read each paragraph of our passage, we will shrink it by stating only the most important information. Paragraph Shrinking is also called summarizing.

2. Explain why you’re teaching the strategy.

Summarizing is a way to help you understand and remember what you read.

3. Model Paragraph Shrinking and gradually involve your students in the process.

a. Listen to me read the first paragraph of this passage about Louis Braille. (By the way, ChatGPT created this passage for me. I simply wrote, “Write a third grade level passage about Louise Braille. Each paragraph should be clearly about one main thing.”)

[image error]b. The first thing I need to do is name the who or what. This passage is about Louis Braille.

c. Now I need to identify the most important thing about Louise Braille in this paragraph. This paragraph tells us that Louis Braille was clever. It tells us that he hurt his eye and became blind. It tells us that loved learning, and he went to a school for the blind. I think that most important thing in this paragraph is that he hurt his eye and became blind.

d. Finally, I will put this information into a sentence that’s 10 words or less. I’ll put up my finger for each word that I say. If I start to run out of fingers, I’ll have to start over.

“Louis Braille hurt his eye when he was young and … ” I’m already at ten words. Let me start over.

“Louis Braille became blind when he was three years old.” Perfect!

e. Listen to me read the next paragraph.

[image error]f. What is the most important who or what in this paragraph? Yes, Louis Braille is the most important who or what.

g. What’s the most important thing about Louis Braille in this paragraph? You have one minute to discuss this with your partner … __________, what is the most important information about Louis Braille? Yes, he made a special code that helped blind people read. Let’s put that into a complete sentence that’s 10 words or less.

Louis Braille created a special code that helped blind people … oh, I’m already at 10 words. Let me try again.

Louis Braille created a code that helped blind people read.

We did it!

h. Listen to me read the final paragraph.

[image error]i. What is the most important who or what in this paragraph? Hint … it’s not Louis Braille! The most important who or what is Louis Braille’s special code.

j. What’s the most important thing about this special code? Yes, it helped people all over the world.

k. Let’s put this information into a summary that’s ten words or less.

Louis Braille’s special code helped people all over the world.

See the strategy in actionIf you’d like to learn more about paragraph shrinking – and how to give students practice using this strategy with a partner – I highly recommend this video from Lindsay Kemeny. She explains how partner reading, with paragraph shrinking, builds fluency while also supporting comprehension.

And don’t forget to check out the rest of our series about reading comprehension strategies!

References

ReferencesFuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2005). Peer-assisted learning strategies: Promoting word recognition, fluency, and reading comprehension in young children. The Journal of Special Education, 39(1), 34-44.

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2011). Writing to read: A meta-analysis of the impact of writing and writing instruction on reading. Harvard Educational Review, 81(4), 710-744.

National Reading Panel (U.S.) & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.). (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.Agarwal, P. K., & Bain, P. M. (2019). Powerful teaching. Jossey-Bass.

The post How to teach summarizing in the early grades appeared first on The Measured Mom.

November 25, 2023

How to improve comprehension by asking and answering questions

Welcome back to our series about reading comprehension strategies!

What are reading comprehension strategies?First, let’s review what reading comprehension strategies actually are. According to Shanahan et al (2010), comprehension strategies are deliberate mental actions to improve reading comprehension.

“Comprehension strategies refer to intentional (not automatic) actions a reader takes to keep his/her head in the game.”

Timothy Shanahan, 2018

In other words, you do something on purpose to help you understand the text.

Teach comprehension strategies to help students understand complex textIt’s important to teach reading comprehension strategies to help students understand text that is challenging for them – otherwise, what’s the point? If they understand the text at face value, they don’t need a comprehension strategy.

This isn’t something I always understood. As a balanced literacy teacher, I thought that I was supposed to start with the strategy. So I would look for books that lent themselves to predicting or making connections. Then I would teach the same strategy for a few weeks, using different books.

This was backward!

Start with the text, not the strategyI should have started with a quality text – and that’s what I’m encouraging you to do when it comes to teaching the strategy of asking and answering questions.

Choose a challenging text that will teach your students something important. Then show them how to ask and answer questions to support their understanding of it.ReQuest: A questioning techniqueReQuest is a questioning technique that has been shown to help students focus on text and pay attention to detail (Manzo, 1969).

Here’s how ReQuest works:

Have students read an assigned text (a few sentences or paragraphs).The teacher should turn over the text and invite students to ask him/her questions about the text. It helps to post question words so students know how to begin their questions: Who, what, when, where, why, and how. The teacher answers the questions without peeking and provides feedback about the quality of the students’ questions.Next, the students turn over the text while the teacher asks them questions. The students answer the questions without peeking.The teacher and students repeat the sequence for the rest of the text.

I love ReQuest because it supports what we know from research: if you want to remember information, it’s much more effective to practice remembering it (by answering questions) than to keep rereading the text. In fact, neural pathways get stronger when a memory is retrieved and students practice what they’ve learned (Argawal & Bain, 2019).

Important tip: Whenever possible, have students answer questions in pairs or in a small group. After students answer in pairs, you can randomly call on a student to share his or her answer with the class.

This technique increases student participation and ensures that everyone is doing what is necessary to remember the information … not just the regular few who raise their hands.

Question-Answer RelationshipThis technique improves comprehension by helping students understand different types of questions (Raphael & Au, 2005).

Explain that there are four types of questions that students may answer about a text:Right There questions have answers found directly in the text.Think and Search questions require readers to combine the information from different parts of the text.Author and Me questions require that a reader read teh text and relate it to his or her own experience.On My Own questions require students to rely on their background knowledge.Choose a passage. Read it aloud to your students, have them read it in pairs, or read it chorally as a class.

3. Ask questions related to the passage. Help students classify each question and find its answer.

Guess what? ChatGPT can help! I asked ChatGPT to write a second grade passage about natural

resources and provide examples of the four types of questions. Here’s what it gave me:

Here are the questions that ChatGPT provided.

Right There Questions:

What is water, and where does it come from?What is soil, and what do plants need it for?Think and Search Questions:

How do trees help us, and what are some things we get from them? *Why is sunlight important for plants, and what process does it help them with?Author and Me Question:

Why do you think the author says that trees are like nature’s giants?On My Own Questions:

Can you think of ways we can take care of the air around us?How can we use water wisely in our daily lives?*This is a weak question, because both parts of the question have the same answer. Nice try, ChatGPT.

SummaryThis post gave you two techniques that you can use to help students comprehend challenging text. ReQuest will help them learn to ask questions about the text they’re reading. Question-Answer-Relationship will help them learn to answer different kinds of questions that are posed to them.

Let me know if you try them!

Also be sure check out the rest of our comprehension strategies series by clicking the image below!

References

ReferencesAgarwal, P. K., & Bain, P. M. (2019). Powerful teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Manzo, A.V. (1969). The request procedure. Journal of Reading, 13(2), 206-221.

Raphael, T.E., & Au, K. H. (2005). QAR: Enhancing comprehension and test taking across grades and content areas. The Reading Teacher, 59(3), 206-221.

Shanahan. T. (2018, May 24). Where questioning fits in comprehension instruction: Skills and strategies Part II. Shanahan on Literacy. https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/bl...

Shanahan, T., Callison, K., Carriere, C., Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Schatschneider, C., & Torgesen, J. (2010). Improving Reading Comprehension in Kindergarten through 3rd Grade: IES Practice Guide. NCEE 2010-4038. What Works Clearinghouse.

The post How to improve comprehension by asking and answering questions appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Teaching expository text structure

Welcome back to our series about reading comprehension strategies!

An awareness of the different kinds of expository text structure can help students understand informational text.

In this post I’ll list the five different kinds of expository text structure and share a routine you can follow when teaching them.

What is text structure?Text structure is how an author organizes a text. Research shows that explicit instruction in text structure leads to gains in reading comprehension (Williams, 2005).

Because expository (informational) text can be organized in a variety of ways, it’s tricker than narrative text, in which stories follow a reliable pattern.

I like Nell Duke’s (2013) recommendation to make at least half of your read alouds expository text. This way you expose your students to more complex text while also building knowledge.

Types of expository text structuresThere are five major expository text structures: description, sequence, cause and effect, compare/contrast, and problem/solution.

[image error]A routine for teaching expository text structure1. Find a short expository text that is organized according to a particular text structure. Make sure that each student has a copy.

If you’re wondering where to get this text, look no further than ChatGTP.

I’ll be honest – ChatGPT and AI in general make me a little nervous – but I won’t deny how useful ChatGPT can be for teachers!

COMPARE & CONTRASTI told ChatGPT to “Write a paragraph using the compare and contrast text structure that compares aardvarks and anteaters. Make the paragraph appropriate for third grade.” This is what it gave me:

Aardvarks and anteaters are two animals that like to eat ants and termites, but they have some differences. Aardvarks live in Africa, and they have big ears and a snout like a pig to dig into termite mounds. On the other hand, anteaters live in Central and South America. They have long snouts and tongues that help them slurp up ants from nests. Aardvarks are strong and live in African savannahs, while anteaters have sharp claws and can climb trees in the forests of the Americas. Even though they both love ants, aardvarks and anteaters are special in their own ways, adapting to where they live to survive and thrive.

Impressive, huh?

DESCRIPTION“Write a paragraph for third graders using the description text structure to describe anteaters.”

PROBLEM & SOLUTIONAnteaters are amazing animals with unique features that help them eat their favorite food ��� ants! They live in Central and South America, where it’s warm and full of trees. Anteaters have long snouts and tongues that they use to slurp up ants from their nests. Imagine a long, sticky tongue reaching into an ant’s home! Anteaters also have sharp claws that they use to dig into the ground and find more ants to eat. They are like nature’s superheroes when it comes to hunting for tiny insects. With their special tools, anteaters are experts at finding and enjoying their delicious ant meals in the forests where they live.

“Write a paragraph about aardvarks for third grade using the problem and solution text structure.”

SEQUENCEAardvarks sometimes face a problem because their favorite food, ants and termites, can be tricky to get. You see, these tiny insects hide inside hard termite mounds. But guess what? Aardvarks are like nature’s little superheroes because they have a cool solution to this challenge! They’ve got super strong, shovel-like claws that work like special tools. These claws help aardvarks dig into the tough termite mounds and grab those tasty ants and termites. So, even though it might be hard to find their food, aardvarks have a clever way to solve the problem and enjoy their yummy meals. Go, aardvarks!

“Write a third grade paragraph using the sequence text structure about anteaters.”

CAUSE & EFFECTAnteaters do things in a specific order that helps them find and eat ants. First, they use their keen sense of smell to sniff out ant nests. Then, with their long snouts, they dig into the ground to uncover the ants’ homes. Once they find the ant nests, anteaters use their super long tongues to slurp up the ants. It’s like a special sequence or a step-by-step plan that anteaters follow to make sure they get their favorite food. Sniff, dig, slurp ��� that’s how anteaters go about their ant-hunting adventure!

“Write a cause and effect paragraph for third graders about aardvarks.”

Aardvarks have some special abilities that help them find and eat their favorite food, ants and termites. One cause is their long snouts, which act like powerful shovels. The effect of this is that aardvarks can easily dig into hard termite mounds to uncover the insects. Another cause is their excellent sense of smell. The effect of this is that aardvarks can sniff out where the ants and termites are hiding. So, because aardvarks have these amazing features, they can cause the ants and termites to be found and enjoyed for a tasty meal!

Okay, that last one was a little weak. But overall, ChatGPT came through.

2. Have your students read the paragraph alone or with a partner. If reading in pairs, students can take turns reading a sentence. If they finish before everyone is finished, they should read the paragraph again.

3. Read the paragraph chorally.

[image error]4. Identify signal words and invite your students to highlight them. A tip: If you had ChatGPT create your paragraph, you might want to add signal words that will make this task easier for your students. Use the chart earlier in this post to find signal words associated with each text structure. (The above passage is weak on signal words.)

5. Ask students questions about the paragraph.

Where do anteaters live?What do anteaters use to slurp up ants?What are two words that describe an anteater’s tongue?6. Have students form questions and ask a partner. Then, have them ask and answer their own questions. They must turn over the page before they answer the question.

7. Complete a graphic organizer together. You’ll find free graphic organizers at the end of this post. If possible, project the organizer onto your dry erase board and fill it in with student feedback.

[image error]8. Together, write a paragraph using the graphic organizer. Walk your students through the process of writing a topic sentence, detail sentences, and a concluding sentence. Model this process many times before asking students to do this on their own.

[image error]I hope this post gave you some insight into how to teach expository text structures!

Get your free graphic organizers!

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD

And check out the rest of our comprehension strategies series by clicking the image below!

References

Duke, N.K. (2013). Starting out: Practices to use in K-3. Educational Leadership, 71(3), 40-44.

Williams, J. P. (2005). Instruction in reading comprehension for primary-grade students: A focus on text structure. The Journal of Special Education, 39(1), 6-18.

The post Teaching expository text structure appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Anna Geiger's Blog

- Anna Geiger's profile

- 1 follower