Anna Geiger's Blog, page 6

October 6, 2024

Understanding the Orton-Gillingham Approach – with Pryor Rayburn

TRT Podcast #189: Understanding the Orton-Gillingham Approach – with Pryor Rayburn

TRT Podcast #189: Understanding the Orton-Gillingham Approach – with Pryor RayburnPryor Rayburn, a teacher and Fellow in Training with the Orton-Gillingham Academy, shares education resources through her website, The Orton Gillingham Mama. In today’s episode she explains the principles of Orton-Gillingham, discusses what elements are not yet supported by research, and shares an effective routine for teaching those tricky function words (the, was, what etc.) that often trip kids up (spoiler alert: it’s all about meaning!).

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcript Resources from Pryor Rayburn:Sight Words Framework FreebieOrton Gillingham Mama websiteCourse: How to Teach (& Master!) Sight Words in 5 Minutes a DayOrton Gillingham Mama on Instagram

Resources from Pryor Rayburn:Sight Words Framework FreebieOrton Gillingham Mama websiteCourse: How to Teach (& Master!) Sight Words in 5 Minutes a DayOrton Gillingham Mama on InstagramYOU’LL LOVE THIS PRACTICAL BOOK!

Looking for an easy-to-read guide to help you reach all readers? If you teach kindergarten through third grade, this is the book for you.

Get practical ideas and lesson plan templates that you can implement tomorrow!

GET YOUR COPY TODAY!

The post Understanding the Orton-Gillingham Approach – with Pryor Rayburn appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 29, 2024

How to apply reading research to classroom teaching – with Harriett Janetos

TRT Podcast #188: How to apply reading research to classroom teaching – with Harriet Janetos

TRT Podcast #188: How to apply reading research to classroom teaching – with Harriet JanetosHarriet Janetos, an author and reading specialist, has a gift for sorting through reading research and understanding how to apply it in day-to-day teaching. In this episode we discuss practical insights from her book, From Sound to Summary.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcript Resources:

From Sound to Summary

, by Harriett Janetos

Brain Words

, by Gene Ouellette & Richard Gentry

Harriet’s Green Lights, Red Flags, Gray Areas

chart

Resources:

From Sound to Summary

, by Harriett Janetos

Brain Words

, by Gene Ouellette & Richard Gentry

Harriet’s Green Lights, Red Flags, Gray Areas

chartYOU’LL LOVE THIS PRACTICAL BOOK!

Looking for an easy-to-read guide to help you reach all readers? If you teach kindergarten through third grade, this is the book for you.

Get practical ideas and lesson plan templates that you can implement tomorrow!

GET YOUR COPY TODAY!

The post How to apply reading research to classroom teaching – with Harriett Janetos appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 26, 2024

The ultimate guide to phonics rules and patterns

I’m often asked about where someone might find a master list of phonics rules or a phonics rules cheat sheet.

I’ve put this post together so you have a place to find the most important phonics rules and patterns.

Let’s dive in!

Note: In this post, letters written between slash marks represent sounds. For example: /sh/ represents the sound you hear at the beginning of the word chef. Letters written between small brackets represent spellings. For example, and are both spellings for the sound /sh/.

Every syllable includes a written and spoken vowel. Before we examine this rule further, we should define vowel.

In English, we have vowel phonemes and vowel graphemes. A vowel phoneme is an open speech sound that you can sing. We often think of two kinds of vowel sounds: “short” and “long.” You can hear the five short vowel sounds in cat, bed, pig, mop, and hut. Long vowel sounds are the vowels’ names, as in rain, seek, light, coat, and cute. However, there are more than just the “short” and “long” vowel sounds, as you’ll soon see.

Vowel graphemes (written representations of the sounds) can occur as single letters (a, e, i, o, u, and sometimes y) and in combination with other vowels and/or consonants.

Let’s take a look at the vowel phonemes and the graphemes that can spell them.

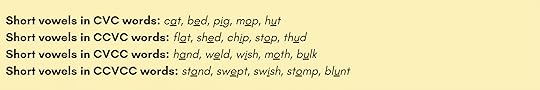

“Short” vowel phonemes are usually spelled with a single vowel letter. They occur in words with the consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) pattern as well as in words that begin and/or end with consonant digraphs or blends.

“Long” vowel phonemes occur in open syllables (that’s coming soon) and in combination with other letters. While some vowel teams can spell a short vowel (such as in bread), most spell a long sound. R-controlled vowels are those in which the /r/ alters the sound of the vowel. I consider the following to be r-controlled vowel graphemes: , , , , and . Finally, there are vowel diphthongs, in which the vowel is two sounds glided into one. Diphthong graphemes are typically listed as and ; and and sometimes and .

There is disagreement among experts about whether there is such a thing as “six common syllable types” in English spelling. However, most will agree that English has both closed and open syllables.

A closed syllable is one in which the vowel is “closed off” by one or more consonants. In a closed syllable, the vowel sound is usually short. (In a multi-syllable word, a closed unaccented syllable often includes the schwa sound. The schwa is the most common vowel in English; it is pronounced as a lazy short i or u.)

[image error]

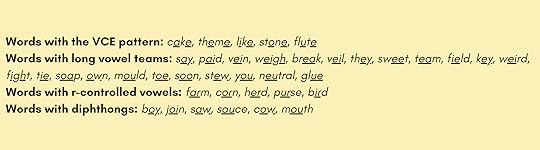

Unlike closed syllables, open syllables end with a vowel, not a consonant. The vowel typically spells its long sound; however, in an unaccented syllable, the vowel grapheme may represent the schwa, as in the middle syllable of dinosaur.

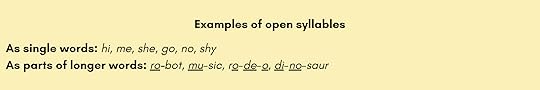

The FLOSS rule tells us that when a one-syllable words ends in a short vowel and the letter f, l, s, or z, the final letter should be doubled. (Get a free FLOSS rule game here.)

This is not a phonics rule, but a distinction I need to make because of the common confusion that I see.

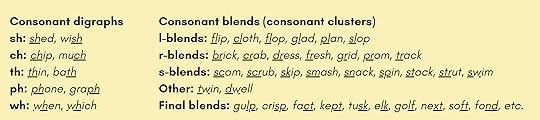

A digraph is two letters that join together to represent a single sound. Consonant digraphs include , , , , and .

A consonant blend (also called a consonant cluster) is 2-3 adjoining consonants that each retain their sound; however, the sounds are quickly blended together. Technically, a blend is not a grapheme because it is 2-3 graphemes next to each other. The reason many programs teach blends is because it requires greater skill to read words with the CCVC or CVCC pattern than it does to read CVC words. I think it’s important to spend extra time reading words with this pattern, but I do not think it’s advisable to teach blends as units or to teach each one individually.

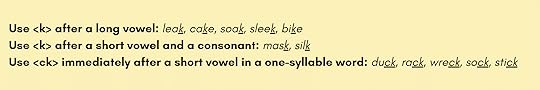

When the /k/ sound is at the end of the word, it can be spelled with or . This is an important phonics rule that we want to teach students early on. You can get a free practice sheet for this rule here.

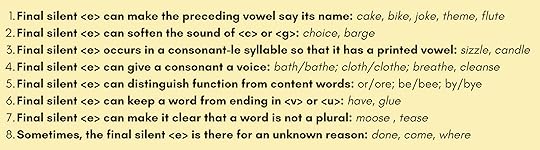

We often think of the final silent as having only a single reason for its existence: to make the preceding vowel say its name, as in lake. But there are many reasons for the final silent !

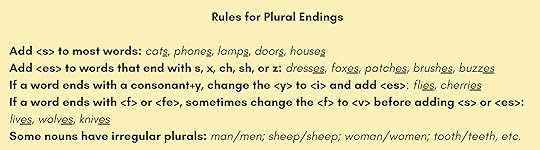

English words do not typically end with , , , , or Lyn Stone calls them “illegal” in her book, Spelling for Life. She also recommends this catchy chant: “, , , , … at the end of a word they cannot be!”

This rule is important because it helps us explain many English spellings.

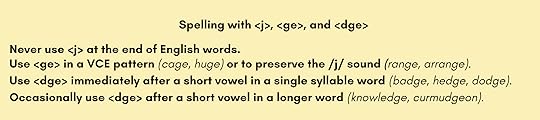

Since is illegal at the end of English words, we use in words like shy, by, and my. We also use the spelling in words like pie, or tie. Exceptions to this rule include the words I and hi, as well as words from other languages such as ski (Norwegian) and broccoli (Italian).Since is illegal at the end of English words, we use or as in cage or judge.

Since is illegal at the end of English words, we use as in unique.

Since is illegal at the end of English words, we use as in glue. Exceptions include words like flu (an abbreviation for influenza) and menu, which comes from the French.

Since is illegal at the end of English words, we use as in have, give, and carve.

For most English words, we form past tense verbs using the ending. The is called a morpheme, because it is a unit of meaning. The spelling communicates that a word is past tense. It is important to teach this so that students understand that a word like jumped is not spelled jumpt.

The ending can be pronounced in three different ways: /t/ as in jumped, /d/ as in played, and /id/ as in landed. The pronunciation depends on the consonant that precedes the ending. The important thing for our students to remember is that the spelling of the morpheme remains consistent, even when pronunciation changes.

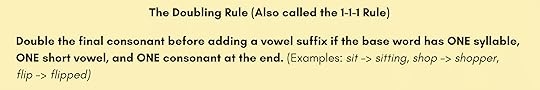

This is an important rule to teach our students as soon as they learn to write words with inflectional suffixes such as , , and . All of these are examples of vowel suffixes because they begin with a vowel.

Drop the final silent when adding a vowel suffix (a suffix that begins with a vowel).

Examples:

live + ing -> living

serve + er -> server

bake + ed -> baked

Nonexamples (because these are not vowel suffixes)

hope + ful -> hopeful

like + ness -> likeness

Keep the final silent if it is needed to preserve the soft sound of or .

Examples:

change + able -> changeable

notice + able -> noticeable

outrage + ous -> outrageous

When a word ends with a consonant + , change the to before adding a vowel suffix.

Examples:

cry + es -> cries

hurry + ed -> hurried

identify + er -> identifier

When a word ends with a single short vowel and /ch/, spell /ch/ with .

Examples: batch, wretch, stitch, notch, hutch

Exceptions: much, such, rich, which

This rule typically applies to one-syllable words, but it sometimes appears within a short vowel syllable of a longer word.

Examples: satchel, kitchen

“Q and u stick like glue.” In other words, The letter may not stand alone in English spelling. Except for names and other proper nouns, the must always be followed by a and a vowel.

It’s important to note that in words with , the is usually acting as a consonant, since it represents the /w/ sound (of course, this isn’t true in words like plaque and unique).

Examples: quit, quaint, quest, queen, quiet

The letter spells its soft sound, /s/, when it immediately precedes , , or .

Examples: cent, city, cyst, icy, agency

The letter spells its hard sound when it immediately precedes the letters , , or .

Examples: car, container, curb

One reason these rules are important is because they affect the spelling of a word when you add a vowel suffix. For the word serviceable, for example, we might wonder why the final silent is not dropped when adding the vowel suffix . The reason the is not dropped is because it is needed to keep the sound of the soft.

Sometimes we need to keep the sound of final hard. Consider the word panic. If we add the vowel suffix , the word would be panicing. This makes it look like the should spell its soft sound, because it is followed by an . To preserve the hard sound, we need to add a : panicking. Other words like this inlcude picnicking, colicky, and frolicked.

Hopefully the conclusion that you are drawing is that English language is not illogical; it’s complex.

The letter may spell its soft sound, /j/, before , , or .

Examples: germ, ginger, gym

The spells its hard sound, /g/, before , , or .

Examples: gasoline, goat, gumbo, begun, cardigan

Sometimes the spells its hard sound, /g/, before the letters or .

Examples: get, gear, target, forget, girl, gift, begin

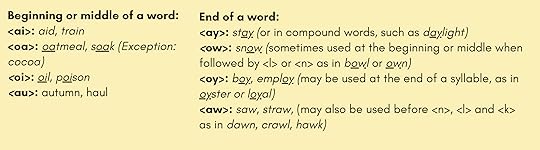

It’s true that there are multiple spellings for different sounds. For example, two common spellings for long a are and . Thankfully, for many of these sounds, it’s not hard to know which grapheme to use when we consider the vowel team’s position in the word:

The letter can represent a vowel or consonant sound, depending on its position in a word. Did you know that the letter spells a vowel sound more often than it spells a consonant sound?

Think of as a stand-in for the letters and . There is usually a logical reason that we use instead of these vowels.

In the word crazy, for example, we can’t use an to spell the long e sound because the word would be craze, and the VCE pattern tells us that the would be silent. The letter jumps in as a stand-in. (Or, as Lyn Stone writes in Spelling for Life, a stunt double.)

Also consider the word fly. We don’t write it as fli because is illegal at the end of English words. So the letter becomes a stand-in.

With this rule we are crossing over into morphology, but both phonology and morphology affect English spelling, so trust me – this is relevant.

Consider the words military and militia. Why isn’t the /sh/ in militia spelled with ? It’s because these words share the base milit. The spelling of that morpheme stays the same, even when the pronunciation changes.

I could give you an infinite number of examples, but let’s keep it short:

Nature and native Malign and malignant Signed and signature

I am a big fan of sound mapping, in which we map sounds to letters by spelling each phoneme on a single line or in a single box. However, sound mapping can get tricky when we try to assign every grapheme to a phoneme. Some graphemes aren’t spelling any sound at all.

For example, in the word two, the is not helping to spell /t/ or /oo/. It’s used to connect this word to other words with a similar meaning (twice, twin, twelve).

Another example is the word ladder. Technically, only the first is spelling /d/. The second is there to keep the vowel short.

What about the word since? The final is not part of the /s/ pronunciation. It is there to keep the sound of the soft.

I could go on forever, but let’s conclude with the word have. The final is not helping spell /v/. It’s there to keep the word from ending with the illegal letter .

This final rule does get hairy. For example, I consider a spelling for long u, even though you could argue that the is there to keep the word from ending in illegal . Different phonics experts and programs have different opinions about which letter combinations are graphemes and which are not. But I encourage you to think about this rule the next time you are confronted with a puzzling spelling. Could there be a logical reason for the intrusive letter?

ConclusionI’ve worked to make this post as comprehensive as possible – but I could never list all the rules and patterns in a single blog post! I encourage you to check out these references for more insight.

References The Complete Guide to English Spelling Rules , by John J. Fulford Spelling for Life , by Lyn Stone Uncovering the Logic of English , by Denise EideThe post The ultimate guide to phonics rules and patterns appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 22, 2024

The 6 systems every school needs to improve literacy outcomes – with Pati Montgomery

TRT Podcast #187: The 6 systems every school needs to improve literacy outcomes – with Pati Montgomery

TRT Podcast #187: The 6 systems every school needs to improve literacy outcomes – with Pati MontgomeryIncreasing teacher knowledge about the science of reading is one important step toward improving literacy outcomes in a school or district. But so much more is required! Pati Montgomery, founder of Schools Cubed, walks us through the six key systems that are essential for improving literacy outcomes.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcript Pati Montgomery’s Resources:

Schools Cubed

Pati’s new book with Angela Hanlin,

It’s Possible!

Pati Montgomery’s Resources:

Schools Cubed

Pati’s new book with Angela Hanlin,

It’s Possible!

YOU’LL LOVE THIS PRACTICAL BOOK!

Looking for an easy-to-read guide to help you reach all readers? If you teach kindergarten through third grade, this is the book for you.

Get practical ideas and lesson plan templates that you can implement tomorrow!

GET YOUR COPY TODAY!

The post The 6 systems every school needs to improve literacy outcomes – with Pati Montgomery appeared first on The Measured Mom.

The 5 systems every school needs to improve literacy outcomes – with Pati Montgomery

TRT Podcast #187: The 5 systems every school needs to improve literacy outcomes – with Pati Montgomery

TRT Podcast #187: The 5 systems every school needs to improve literacy outcomes – with Pati MontgomeryIncreasing teacher knowledge about the science of reading is one important step toward improving literacy outcomes in a school or district. But so much more is required! Pati Montgomery, founder of Schools Cubed, walks us through the five key systems that are essential for improving literacy outcomes.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcript Pati Montgomery’s Resources:

Schools Cubed

Pati’s new book with Angela Hanlin,

It’s Possible!

Pati Montgomery’s Resources:

Schools Cubed

Pati’s new book with Angela Hanlin,

It’s Possible!

YOU’LL LOVE THIS PRACTICAL BOOK!

Looking for an easy-to-read guide to help you reach all readers? If you teach kindergarten through third grade, this is the book for you.

Get practical ideas and lesson plan templates that you can implement tomorrow!

GET YOUR COPY TODAY!

The post The 5 systems every school needs to improve literacy outcomes – with Pati Montgomery appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 15, 2024

Why a skeptical balanced literacy teacher embraced the science of reading

TRT Podcast #186: Why a skeptical balanced literacy teacher embraced the science of reading

TRT Podcast #186: Why a skeptical balanced literacy teacher embraced the science of readingJolene Rosploch was a committed balanced literacy teacher. When Schools Cubed arrived to help her school improve literacy outcomes, Jolene was skeptical. Listen to find out what led her to embrace the science of reading.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcript Jolene recommends:

Shifting the Balance

, by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates

Jolene recommends:

Shifting the Balance

, by Jan Burkins and Kari YatesYOU’LL LOVE THIS PRACTICAL BOOK!

Looking for an easy-to-read guide to help you reach all readers? If you teach kindergarten through third grade, this is the book for you.

Get practical ideas and lesson plan templates that you can implement tomorrow!

GET YOUR COPY TODAY!

The post Why a skeptical balanced literacy teacher embraced the science of reading appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 8, 2024

From struggle to success: A reading specialist’s structured literacy journey

��TRT Podcast #185: From struggle to success: A reading specialist’s structured literacy journey

��TRT Podcast #185: From struggle to success: A reading specialist’s structured literacy journeyReading specialist Julie Speidel describes the struggles and triumphs that she faced as she supported her staff in improving literacy outcomes.����

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, this is Anna Geiger from The Measured Mom and I'm also the author of the book, "Reach All Readers," which is an excellent book for a staff book study if you're looking to help your staff learn more about the science of reading.

In today's episode, I'm interviewing Julie Speidel, who worked with her staff to help them understand and apply the science of reading. She walks us through her whole journey from when she was a balanced literacy teacher, to changing her understandings, and then the challenges, and ultimately success, that she faced when helping her staff move away from the more balanced literacy methods to more explicit instruction and more intentional instruction in foundational skills, as well as oral language and comprehension.

What I love about her story is it's very clear this is not always smooth sailing and there are ups and downs, but everyone is moving forward together, and you'll see how she developed a relationship with her staff as well as with the administrator so that all of them could work together to make these changes. Here we go!

Anna Geiger: Welcome, Julie!

Julie Speidel: Hi, there! Thank you for having me on.

Anna Geiger: Let's go back in time a little bit and tell us how you got into education.

Julie Speidel: Growing up I always knew that I wanted to be working with children, and I ended up in education. It's interesting because thinking about what area I wanted to focus in on, I thought to myself, "You know what? I just don't want to do early childhood. I just don't want to be responsible for teaching a kid how to read because that's so important, and I don't want to mess them up."

My initial license was first through sixth grade and I started as a fifth grade teacher teaching ELA part-time and working as a special ed para.

Then I got a job full-time as a second grade teacher in the building, and that's where my heart is. Even to this day, I love second grade. I think not only are they just learning so much, but they're developing their sense of humor, their independence, and it's such a big, big learning age.

I went back to school and got my degree as a reading specialist, then I got a job in Cudahy working as a reading specialist in 2014, and that's what I have been doing ever since.

Anna Geiger: I can relate to what you said about how not wanting to teach the primary grades where you're actually teaching kids to read because that's how I felt after I left college. I had classes in teaching reading, but we never really talked about how you get kids started with reading and I felt like, "Well, I'm going to teach the middle grades because I don't know how to teach kids to read, and I don't want to mess them up."

I wish I would've known that that's important to know no matter what grade you teach, especially in those middle grades when kids are stuck, if you don't know how it all begins, then you don't know how to help them.

But yeah, I can totally relate to that. A lot of it was just learning on the job and learning as I've done in the past few years.

So you've been in this position for about 10 years, but you shared with me that you have not always understood the idea of the science of reading and structured literacy. Can you go back in time and talk to us about what you were doing at first?

Julie Speidel: So one of the pieces that we talked about in our master's program is the importance of not specifically diagnosing, but still assessing our students to figure out what level they're at. In my district where I was a second grade teacher, I was really pushing for getting some sort of assessment in there, and we actually used the Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System. I was the leader and was gung-ho getting that into our building.

We assessed our students, but one of the things that we discovered was it was so overwhelming. I mean, you would sit with some kids for 10 minutes trying to figure out their right exact level!

Anna Geiger: Or longer.

Julie Speidel: Right! And what are the rest of the kids doing during that time? Not learning. It is not a valuable use of their time at all.

We got in their LLI program to do leveled text and working with it and using the three-queing system like, "Look at the first letter, think about the picture, what are you reading? What would make sense in this sentence?" Those were our go-tos; that's what we were working through.

Then when I came to the Cudahy District, I was like, "Yes, I know Fountas & Pinnell. I got to go to Chicago and I did their training with LLI, I met them, and I am totally on board, I know what to do, this is familiar."

So when I first came, that's where we were at. Our district had a hodgepodge of phonics programs. They were teaching phonics, but they were not teaching it consistently. We had five elementary schools in my district when I started and each school was using something different.

Our school was using, and we had somebody who was trained, on Wilson. They had brought in Fundations, and so I was intervening with that right away. That's structured literacy right there to an extent, because that's Orton-Gillingham based.

I'm reading these things and I'm like, "Oh, CK at the end of a word is because of the short vowel?" I mean, light bulbs were going off for me because growing up, I went to my lower elementary years in Florida and it was a big phonics state and a big push. Having those pieces, I knew how important it was.

I tried to get kids to sound out words and things, but then going to the training with Fountas & Pinnell, I mean, we had a consulting firm come in and they're like, "Know better, do better." They just kept saying that over and over again.

I think it was last month that I came across that it was actually Maya Angelou's quote, and it's, "Do the best you can until you know better. And then when you know better, do better." That very much resonated with me.

Even back then I was like, "Oh, this three-cueing system, this is the bomb. You've got to try this. This is the better." And it's not the better.

Anna Geiger: It sounds like from what you said that your master's program got the importance of assessment, but they were teaching you to use the wrong tools, and then you use the wrong tools thinking that those were useful because many of us thought that those levels meant something and now we find out they're basically arbitrary.

In your training with Fountas & Pinnell, did they talk a lot about teaching phonics to kids or were they more about using context and pictures and the first letter?

Julie Speidel: There was a lot of word-part things. There were games and things that went with the programs, but it wasn't very much honed in on a certain skill or a certain phonics pattern or something along those lines where they're going to be having that direct practice with it afterwards or within the text.

Anna Geiger: Yeah. So it was more embedded or haphazard?

Julie Speidel: Yes.

Anna Geiger: Which feels... That's the way that I did it for a long time too, and to me that felt like the better way. It felt more meaningful and for me it was nice. I felt like I had this freedom to know my students and to do what was needed at the time, but like you, I didn't really.

Even though I also learned with phonics, I didn't know all those phonics patterns because I had no program that was teaching them to me, and I had not learned them in college or graduate school. It's interesting how programs can also teach teachers, like you said, and Fundations was helping.

Now you were the specialist, what about in Tier 1? What kind of phonics instruction were the kids getting then?

Julie Speidel: In phonics, it was all over the place originally.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Julie Speidel: When I first came, they had Journeys and everybody was using their own phonics program. We had that for two years, I believe, and it was heavily focused on the Core standards, the Common Core standards.

Then we went through the process of adopting Benchmark Literacy, and that did have a phonics component. As specialists, we said, "Okay, we're getting this program and everybody is using this phonics program." The tool we started using was the easyCBM.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Julie Speidel: Then we eventually moved over to AIMSweb. We would do all of these early education assessments and early literacy assessments, and we would just be like, "Okay, here's where they are, here's where they're going," and kind of tracking that piece.

We weren't seeing growth. As a Tier 3 interventionist, I was seeing kids continue through the intensive intervention, or they would be referred for special education. We followed the protocols, the letter of the law, how many interventions to do, and we just weren't seeing the growth. I was doing LLI with them, and I was finding those pieces were missing.

Then that's when I started getting into David Kilpatrick and reading about the importance of phonemic awareness.

So then I said to my principal that as a district, we weren't aligned. Our schools were kind of an island, and so I said, "I want to try this." I would see growth in the kids in my small groups, but then it wasn't consistent back into the Tier 1 classroom, so the growth still wasn't happening.

In February 2021, I actually looked back in my notes from our meeting agendas, and we said that we need to have more direct instruction in our early literacy. We started to dig into it and kind of came across some webinars and things like that that. We were looking at this going, "Oh my gosh!" Our mind was blown.

I got really irritated and frustrated with my master's program because I was listening to the dates in these things and we're talking like 2000, 1999, the Simple View of Reading, I believe that's the '80s. I was just like, "Why didn't they teach me this?"

Anna Geiger: Yeah, we all feel that way.

Julie Speidel: So then I went down a rabbit hole of science of reading and dug in and took everything I could. I came across your program, your blogs, and that summer I took your Teaching Every Reader course.

Then our director of instruction at the time, she reached out to the Department of Instruction to see where the state was going and got connected with a consulting company called Schools Cubed and Pati Montgomery.

They came in and did an assessment, an audit, of what our classrooms were doing, and how they were teaching, and how we could do better, and then we signed a contract to work with them for three years on improving and switching over to that structured literacy piece that the science of reading shows is more effective.

It was a ton of heavy lifting that first year.

Anna Geiger: I know you mentioned in your notes before we were talking about how you don't want to make teachers feel like what they've been doing all this time has been wrong. You want to support them in moving forward, but you don't want to put a heavy burden on teachers because of course not everything was wrong, but also there were some practices that need improvement. Do you have any advice for someone who's working with teachers and trying to help them make the shift in a supportive way versus an accusatory way?

Julie Speidel: I have made many mistakes in how I went about doing that, and the best information on that that I can offer is listen to your teachers and present the information and listen to what they're saying back.

There are lots of whys. Have the answers. If you don't know the answer, don't be afraid to say, "Hey, I'm going to go find that out."

The other piece that I got was that this is just a pendulum shift. This is going to go and it's going to be here for a little while, and then I'm going to have to go back to a different way of teaching. I would bring it back to that, and this is where I'm not quite sure of my numbers, about 75% of kids are going to learn to read no matter how you teach them.

Anna Geiger: Yeah, I think it's lower. I think you're referring to Nancy Young's Ladder of Reading and Writing, and I think it could be up to 50%, maybe 40-50%. But you're right that some kids, even if you use balanced literacy, they're going to be fine. Now, they could be better, but they're going to appear just fine. But to your point, many kids won't. A large percentage of kids must have this structured approach or they're just not going to be good readers and spellers.

Julie Speidel: Right. So why not change this practice? I mean, it's not a pendulum shift, it's an actual way of teaching that makes sense, and something that I don't want to go away from until I know better again.

Anna Geiger: You've already talked a little bit about what was happening already. It was kind of haphazard, different programs for different teachers in one school, no phonics program. Can you compare that to what's happening in classrooms now? And also talk a little bit about your data and how that's shifted?

Julie Speidel: Every teacher is teaching the phonics to fidelity, and that is insured by the specialists in the building coming in and doing observations and providing feedback.

In our buildings, it's not like observations in the past where your principal would come in and he would let you know, "Hey, I'm coming in to see you. I'm going to be observing this. Where's your lesson plan?" All of those things. The specialists and my principal were part of almost every planning session initially, and the first two years it kind of got a little busier when we merged schools and we went from a school of like 130 to a school of almost 300.

It's not just the phonics and the phonemic awareness piece. Our lesson plans include all of those five pillars from what a lesson needs for that structured literacy. Those pieces are all there.

Anna Geiger: Yeah. For someone listening, that would be, you're also teaching comprehension, building fluency, and teaching vocabulary.

When I visited a school in your district, I did see that. We got to go to different classrooms and see phonemic awareness being taught, we saw phonics lessons. We saw phoneme-grapheme mapping, which is application of phonics skills. We saw a teacher explicitly teaching vocabulary and another teacher teaching comprehension. It was really neat.

I love how you talked about how the visits to the classrooms are different now. It seems to me that the previous visits, and I know because I've had them as a teacher, were more almost like a pop quiz or a test, whereas now they're more of a coaching session. I'm assuming the teachers are interested in your feedback, and it's more of almost a problem-solving situation where you're working together to help fix any issues that there might be. Would you agree?

Julie Speidel: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. That's personally how I run our sessions. I want them to come to me and say, "This is not working." I mean, I am curious to see how this shift would've gone in my first two years of teaching or my first two years as a coach versus having almost been there eight years. I mean, there's a lot of trust building. You talk about building trust with students in your classroom. It was building that trust with the teachers and letting them know that I'm in this too.

I guess that would be part of my advice is you have to make yourself vulnerable and show them that this is a struggle for you too. You don't know everything, and it's all a collaboration. There's no hierarchy.

However, they do still do that. They're always like, "Oh, Ms. Speidel is here! The police are coming to check to make sure I'm doing it right."

I think some of that goes away when you're in the classroom so much. I was in and out of there every day, whether it was coming to get students to take them to do intervention, and I would always stay for an extra 30 seconds to see or if it was interacting with the lesson. I knew what the lesson was because I was part of the planning process.

The other piece that I would suggest if you're making the shift, and I apologize, this is kind of going all over squirrel moment in my brain.

Anna Geiger: No problem.

Julie Speidel: Is that first year I didn't try to tackle everything. My first year I really focused in on how to improve the phonics component, putting together something that allowed for that extra meaningful practice as a class.

We decided that our best route of instruction was for everybody to use the same materials as we created slideshows, and then we would put together practice grids of the letters. They would go through and say all the different letter names and then do the sounds, and then you could say, call on certain groups to do that.

It was very engaging and quick and you could isolate, "I know these three kids are struggling with a certain sound, I want to have just these three kids go and see if I can hear them doing it."

Then we also did the same thing for our high frequency words, spiraling the ones we're practicing, and having the new ones in there.

We have district routines now for how to teach our high frequency words. We have district routines for how to teach our vocabulary and those kinds of things, so putting those in place. That first year we did that, we got those in place.

Then we also worked on, it's called the six-step lesson plan. It was designed for a small group situation where you introduce one new letter, you review three letters, and you practice those, and then it kind of scaffolds and goes... So then once you have your phonics skill, then you introduce the high frequency words, and then you go into the decodable that practices the phonics skill that you did and work through those pieces.

We kind of took that. We use that in our small group, and we used that for kindergarten when they were ready for a book, first grade, and second grade. We worked really hard to make sure that those pieces were in place. Our first year we didn't have good decodables, so Schools Cubed recommended we purchase the Super Readers, Challenge Readers from Voyager Sopris, The Power Readers.

Anna Geiger: Yes, and they're very inexpensive.

Julie Speidel: Yes. And the primary phonics ones.

My school had some extra funding through state funds and federal funds, and I did research and we got in some other decodables. I created so much that first year, basically like a card catalog of phonics skills for all of the extra titles that we got. Teachers could come and pull books because they knew, "Oh, we're working on EIGH. I need a book that practices that." They would go to the spreadsheet and find it, they'd come to my room and check out the books for their small group, and things like that. You have to have the resources available.

Anna Geiger: When I look at how you've worked to build trust and help support your teachers as you do this, here are some things I noted. First of all, there's very much a team mindset. It's not you at the top saying, "You've got to do this. Now I'm checking on you." It's more, "I'm learning this with you and here are the things I've learned. I didn't always know these things and here's why we're going to do them."

You talked about the importance of why, not just giving instructions.

You also have a humble and vulnerable perspective in terms of admitting past mistakes. "We all have things that we wish we'd done differently as teachers, and we need to be able to accept that and be open about that. But also now we know better, so let me share with you the tools that will help you implement this approach."

And you've got that lesson plan, which sounds to me like a pattern for explicit instruction because so many of us didn't really know what that was, didn't really understand what it means, to be explicit in our teaching, and then to fill in that review. It's scaffolded practice.

You give them what they need to do that, but then also you're there to help them as they figure this out. I like how you said you were in their classrooms often, and hopefully that was a comfort to them versus a scary feeling. And the more you build that relationship, the more that can be not a scary thing but, "Oh, good, she's here to help and give me feedback."

You talked about when you shared with them feedback, you start with the positive. We all know how important that is. Teaching is such a personal thing. We really need that for someone to start with a positive and acknowledge what we're doing. Teaching is wonderful, but really tough, even on good days. There are just so many things that go into it. I love that you're able to start that way with your teachers.

As we get closer to wrapping this up, the teachers prior to this were doing more of their own thing kind of, but now there were a lot more expectations from the district and support from you in terms of, "We're all doing this." How did that go over, and how have the teachers feelings toward this explicit structured instruction changed over time? Are there any stories you could share or any comments about how the teachers feel about this and what they've seen?

Julie Speidel: Yeah, so we've actually had that conversation, and I can specifically think of sitting down and the faces of these teachers saying how overwhelmed and burnt out that they felt initially. At the same time though, they wouldn't go back and do it differently because by basically being thrown in the pool, you learn to swim. If it had kind of been rolled out a little more gradually, they may not have bought in as quickly because they could still kind of do their own thing and be wishy-washy with it.

Is there a better way to do it? There might've been. We could have maybe in that first year just focused in on that small group. Maybe that's the piece that we should have done.

But as I said, the teachers said, "I don't know if I would've done it differently."

Other teachers sitting around were going, "You know what? I think you're right." They were kind of feeling that same thing.

I think having the level of support that they had from myself and the other specialists in the school I think was tantamount as well.

The fact that the principals were involved and that the principals were part of the trainings and the principals were part of the walkthroughs, that was huge. That puts your principal to them in an approachable light because they're in there just as frequently, not doing those official pop quiz type observations. It was very informal.

We had the opportunity to talk through these observations and what we were seeing, what's working, what's not working, how can we tweak this? Then having the specialists go back to the teachers and having those grade level meetings. I think that has been very helpful.

Anna Geiger: A lot of people now are talking about how can we make changes and implement the science of reading and structured literacy? So many kids are failing, but it's a hard thing to do because just kind of jumping in can turn some people off, and it can be overwhelming.

But you have a success story where you did that. You had the specialists come in and teachers knew we're just going to do this now. There was lots and lots of support, but it was hard at first. What are teachers saying about it now a couple years later? Do they compare the way they used to teach with how they teach now and what do they think?

Julie Speidel: They're seeing the difference in their students.

One of the big pieces that we worked on with our younger grades is that oral language development, getting them to talk about what they're reading, talk about the phonics skills, talk about the rules, talk about the vocabulary. We can see the progression in our students.

It's crazy because I'll walk in, and I'll be doing an observation and be like, am I watching a YouTube video of a class doing this? You watch these exemplar YouTube videos of kids saying, "I heard you say that the word soar means to fly high above." And they're doing it! They're practicing it, they're responding, and it's sticking with them.

Walking down the hall to kindergarten I hear, "Ms. Smith, we're having a crop of fresh vegetables for our snack today!" And your heart just goes, yes! You're just so thrilled. In that sense, we're seeing that happening drastically.

We're also seeing... You had asked about the data side earlier. We're seeing kids that are not stuck in intensive intervention. They're moving back into the classroom. I don't have specific data on this, but I would say I probably referred two to three students a year around that second and third grade level, as they had had the opportunity to go through the different interventions by that point.

In the past three years, there has been one student that I would say needs some special education testing and referral. Even though three to one seems very small, it's still huge.

The other piece is kids would just continually be in those interventions because they weren't getting it. Now they do their structured intervention with us in the Tier 3 level, but what they're doing in the classroom is supported by that.

It's so much extra practice that just from this year to next year, in second grade, we started the year I think with four or five small groups for intensive interventions in second grade. Not that they were below the 25th percentile, they were just below the 50th percentile.

Anna Geiger: Gotcha.

Julie Speidel: We started with four of those. Moving into third grade for next year, we have none.

Anna Geiger: Oh, wow! That's so exciting!

Julie Speidel: For our first graders, we use the CORE phonics screener, so we know which skills that they're missing, which ones that they need to work on that have been previously taught. And so in our intensive intervention, let's say we'll work on short U, and we will use the decodable from the classroom, and we have that six-step lesson plan that we format. They practice the skill, they practice the high frequency words, they practice reading the text multiple times, and they do that with us for 15 minutes. Then they also do it in their classroom with their classroom teacher for 15 minutes. They practice writing the words and things like that.

It's repetition of these skills and just kind of moving that needle slowly initially so that when we get to those upper levels, we're finding that we don't need as much support.

Anna Geiger: You're taking care of most of it in the early grades, which is what we're supposed to do.

Julie Speidel: Yeah. We're doing it in kindergarten too like, "What letters do they know? What letters don't they know? How can we work on this? How can we improve it with their handwriting? How can we tie it all together?"

I think I referenced purposeful practice. "If this is what I'm teaching, how can I practice this multiple times in multiple ways, what can I connect together so that it makes sense?"

Anna Geiger: We covered a lot of things. We talked about your journey about how there was a lot of hodgepodge things going on. You brought in outside support, you dove right in. It was hard at first, but there was lots of support from the reading specialists.

As the years have gone by, the teachers have really seen a huge change in their students. You have fewer kids that are stuck in intervention, I should say. You're taking care of what they needs in intervention versus kind of wondering what to do next.

For me, that's been a huge difference between the idea of balanced and structured literacy is, "Oh, now I understand the big picture."

I also understand the use of a universal screener and then a diagnostic. I know how to pin down what's the problem, and I know what to do to fix it. And I have a system, like your school does, for helping kids get what they need when they need it, but then move them out so they don't have to be stuck in this extra support forever because we can take care of it.

Are there any final thoughts that you have or resources that you would send people to, whether classroom teachers or reading specialists, to learn more things that you found really helpful?

Julie Speidel: Yeah, I would definitely say as a team, I think that they would very much benefit from doing the "Shifting the Balance" book together, because I think it really portrays what balanced literacy is and what structured literacy is, and seeing that we're not throwing the baby out with the bathwater. There are things that are the same, and they're easy shifts. There is no set way of how to do this, and it's going to be a struggle.

For phonemic awareness, David Kilpatrick's "Equipped for Reading Success," that book to me was very helpful.

I don't mean to be a plug for your program, but that Teaching Every Reader course, it was very helpful.

Surprisingly, Stanislaus-

Anna Geiger: Dehaene, I think it's Dehaene. I think I heard him pronounce it that way. It's tricky.

Julie Speidel: A neurobiologist talking about how your brain... I find him very engaging. Other people are probably like, "He's so dry," but I'm just a nerd. We were actually showing some of his clips to the teachers now on how is this working? Trying to get them still to understand and buy in.

Anita Archer has been huge with that vocabulary piece and the student engagement.

Then I did the first portion of LETRS, and that was very eye-opening. It's very similar to what our state is mandating that 4K through third grade teachers and principals have to go through mandatory training, and the program that we're using is similar, but those pieces are very eye-opening.

Anna Geiger: Well, I will be sure to link all those things in the show notes. Is it okay if people send me questions that I pass them on to you and then you can help a teacher?

Julie Speidel: Absolutely.

Anna Geiger: That'd be great because I'm sure a lot of people have more questions about the specific things that you were doing that we didn't get into. Also, especially someone in a reading specialist position that's trying to support their staff, that can be a tricky thing.

Thanks so much for sharing your story. I know this is going to help a lot of teachers.

Julie Speidel: Well, thank you for giving me the opportunity to do this.

Anna Geiger: This is actually the second in a four-part series talking about the work that a school district has done to move from balanced to structured literacy. That is Cudahy in Wisconsin. Last week I talked to Candice Johnson, this week it was Julie. Next week will be another reading specialist from the school. Then finally, in the fourth week, we'll talk to Pati Montgomery, leader of Schools Cubed.

With that, I want you to check out the show notes, and you can get all the links to the resources that Julie mentioned. You can find those at themeasuredmom.com/episode185. Talk to you next time!

Closing: That's all for this episode of Triple R Teaching. For more educational resources, visit Anna at her home base, themeasuredmom.com, and join our teaching community. We look forward to helping you reflect, refine, and recharge on the next episode of Triple R Teaching.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Julie’s recommended resources Shifting the Balance , by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates Equipped for Reading Success , by David Kilpatrick Reading in the Brain , by Stanislas Dehaene Anita Archer’s website LETRS

YOU’LL LOVE THIS PRACTICAL BOOK!

Looking for an easy-to-read guide to help you reach all readers? If you teach kindergarten through third grade, this is the book for you.

Get practical ideas and lesson plan templates that you can implement tomorrow!

GET YOUR COPY TODAY!

The post From struggle to success: A reading specialist’s structured literacy journey appeared first on The Measured Mom.

September 1, 2024

How one school moved from balanced to structured literacy – with Candice Johnson

��TRT Podcast #184: One school’s journey from balanced to structured literacy – with Candice Johnson

��TRT Podcast #184: One school’s journey from balanced to structured literacy – with Candice JohnsonToday’s episode tells the story of a Cudahy, Wisconsin school’s journey from balanced to structured literacy. Reading specialist Candice Johnson describes how her school implemented systems, high impact instructional routines, and more��to improve reading instruction in every classroom.��

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, this is Anna Geiger from The Measured Mom and the author of "Reach All Readers." Before we get started, I want to quickly share a portion of a review of my book written by David Pelk on Amazon.

He wrote, "'Reach All Readers' is a great learning tool and resource for all educators. Anna Geiger has a true gift of summarizing research and then connecting it with practical ways to use it. She has given you the support, including additional ideas and materials to make it practical. Her layout of her learning will not only point you in the direction you want to go, but will also provide the next places you might go as you figure out your own next steps. This is a book you want to have in your resource collection to support all readers."

You can learn more at reachallreaders.com.

Today is the first in a four-part series. I'm interviewing Candice Johnson, reading specialist at a small school in Cudahy, Wisconsin. Her district worked with an organization called Schools Cubed to help improve literacy learning across the board. In this episode, she walks us through what that looked like and how their school has implemented particular systems, high-impact instructional routines, and more to improve reading outcomes for everyone. Then she talks about where they're going next.

Anna Geiger: Welcome, Candice!

Candice Johnson: Hi, Anna! Thanks for having me.

Anna Geiger: This last spring you and I met at a presentation that I was giving about the science of reading, and you invited me to your school in Cudahy to see all the changes that your school's made. That was a wonderful morning of visiting different classrooms and talking with teachers about the systems changes you guys have made, so I'm really excited to dive into the details today.

Before we do that, could you introduce us to yourself and talk about how you got into education?

Candice Johnson: Absolutely. My name is Candice Johnson, and I am a reading specialist instructional coach for the school district of Cudahy. I really love my job and the work that we're doing, but I definitely did not see myself as being in this role and doing the work that I'm doing.

My journey kind of started off a little bit different. I've been teaching for almost 15 years. I started off as a substitute teacher and that's where I landed my first job, and I was really excited. My first couple years as a teacher, one of the things that I realized and did a lot of reflecting on was that I wasn't trained to teach kids to read. We did some of the things that you hear about. We did the assessment system three times a year, and we would collect this data, but we really didn't do much with it. We would look at it and go, "Oh, that's too bad."

I had so many questions, and I had so much responsibility sitting on my plate, looking at 25 kids in front of me. My expectation is we've got to get these kids to read, and I knew that I didn't have the capacity to do that in the way that I wanted to.

About five years into my journey, I took a risk and went back to school, and I got a master's degree from Cardinal Stritch University. As I evolved with my education, things started changing in my classroom, and it was really amazing. I will never forget I had gone on a field trip one day and my building administrator had asked me to meet her in her office. She asked me to be the building reading specialist, and I looked her dead in the eye and I said, "Absolutely not."

That classroom, those kids, those were my people. That's what I love doing. Those are my community of kids. It took about five or six times of having the same conversation and pulling me into the office.

What really got me to put my foot into this role is she sat me down and she said, "Listen, Candice, I have seen you go from being that new teacher to what you are today. You can see and you can feel the change that has happened in your classroom, and it is remarkable. I need that change to happen across our building. The impact that you're making is great, but we can make a bigger impact together, and I need that knowledge and that coaching to go along with me as your building administrator."

Anna Geiger: Have you been in Cudahy this whole time?

Candice Johnson: I have, yeah.

Anna Geiger: Could you talk to us a little bit about the Cudahy school system and what that looks like?

Candice Johnson: The Cudahy School district serves roughly 2000 students. We have gone through some challenges in the last couple years. As our community has been growing, I've watched the particular elementary school that I work in go from being over 400 students to now, we have declined to less than 200 students. We have faced a school closure and potential more school closures, and that's a really devastating feeling to have in education.

But we're a very proud district. We are a district who has done some reflecting and has made some very positive changes. Several years ago, my curriculum director, Karen Savaglia, who is wonderful, really recognized that in looking at our school data from the state report card, we were underserving our community.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Candice Johnson: And we needed some outside help. She had reached out to a company they called Schools Cubed. It's a consulting firm that is run by Pati Montgomery based out of Colorado.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Candice Johnson: She and her team stepped in during the time where we were seeing that we were really failing our students. Especially after that pandemic, I think a lot of schools saw a very big decline in their numbers. I know in my school, we, I think historically, were always around the 30th percentile, which is not good. Reflecting back, I don't even think I knew what those numbers were.

Anna Geiger: Right. Right.

Candice Johnson: Nobody talked about them. So we started having conversations and we started looking at graphs together, and we had dropped to 21% and went, "Oh my gosh, this is not okay."

Anna Geiger: For people who are listening, does that mean 21% of kids were reaching benchmark for reading achievement? Is that what you're saying?

Candice Johnson: Yes, according to the state reading assessments, the Forward assessments.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Candice Johnson: We said we have to make this change. We have to be reflective, and we need to move forward.

It has been quite the journey. It has been a difficult journey, but it has been the most amazing and rewarding journey because of the results that we have seen in the three years. We're going into our fourth year.

For my school in particular, we were at, according to state testing, 21% of students reading at proficiency. After one year with Pati Montgomery, we raised that to 42%.

Anna Geiger: Great!

Candice Johnson: That was huge. Three years into that journey, we are now at 47%, building that momentum and continuing to grow our students.

Our goal is to really follow some of the statistics that we're hearing from research. The National Institute of Health has come out and said the brain has the cognitive capacity to read, and that should be reaching 95% of our population, with the other 5% roughly having cognitive disabilities.

Our goal is to continue to prove to the Cudahy community that we can take a community that has low socioeconomic status, it is a diverse community of learners... In the past, there have been a lot of excuses as to why these kids could not learn, and we've been able to push those aside and say, "Yes, they can." That's our journey right now and moving forward to that 95%.

Anna Geiger: Talk to me about what the teachers were told initially and maybe what kind of pushback you may have gotten.

Candice Johnson: The unfortunate thing about being in the teaching profession is that you have a very short window before you are sitting with kids to get professional development. You're coming off of summer break, and so when our teachers, including me because I didn't have much information either, sat down with our first presentation and were hit with a lot of information really fast, then it was just zero to 100. It was incredibly overwhelming, and it kind of just felt like everybody was just drowning in new information and figuring it out as we went, but things got better. I think it's just the nature of what education is in not having that time that we need to prepare in advance.

What we learned in this process is that Schools Cubed is all about systems, structures, and instructional routines. Pati has developed some really great tools that have really helped us along.

She has what she calls a literacy evaluation tool. It is a tab that sits on my computer every single day. It's essentially a rubric, and that rubric is compromised of six categories. That's universal instruction, intervention assessment, data-based decision making, professional development, and school leadership. All of those categories have a rating system that has been the tool that my team... When I say team I mean the amazing teachers that I work with who are the ones in the classrooms implementing all of this work, and my amazing administrator who is leading this work.

The part that really changed the mindset with our implementers, our teachers... At first it is so hard to hear, especially when you've been teaching for 20 plus years, that there are all these changes to make, and to undo and unlearn things is really challenging. And so people, of course, are going to be very resistant to wanting to make that change.

But there was a school board meeting where Pati had gone to the school board and presented some information. In her discussion with the school board, a light bulb moment went off with all of our staff. In that moment, she basically told them that the purpose of her consulting firm and what sets her apart from other consulting firms is that this isn't about critiquing teachers. This isn't about going in and telling them they're doing everything wrong. This is about building leadership. So Pati's belief is that when we have principals who are literacy leaders and are evaluators, that is when the change is going to happen.

When Schools Cubed started coming in to do visits, which happened once a month, they would visit classrooms, but they didn't really sit down and talk with teachers as much as they did sit in and have a two-day discussion once a month with the building administrator and myself. It really came down to building that strong team and teaching a principal, what are those look-fors? What does that research say? Because when I leave here, you are the one who has to do the work, and you are the one that has to hold these teachers accountable, and you are the one who is going to set the tone for the expectations moving forward.

That was a very pivotal moment for the staff that I work with. When they saw that their leader had to do the learning first, it was much more impactful.

Anna Geiger: When you had this leadership, you all became basically forced to be on the same page. Can you talk about that, about before and after? How did things change with Schools Cubed kind of taking leadership here?

Candice Johnson: I can be super honest and tell you that as I have to make my schedule based off of other people's schedules, I realized reading really wasn't being taught. It wasn't in the schedule for some classrooms, and that was really alarming to me. I think there was an upsurge in Teachers Pay Teachers, with good intent, but not a lot of direction on how to use materials. Walking into classrooms, oftentimes reading was just a mixture of worksheets that students were working on that really didn't have a solid objective to the learning that needed to be had.

We had a 90 minute literacy block, and half an hour of that was shared reading and maybe ten minutes of phonics. Then it was an hour of what we call the Guided Reading, using a lot of Fountas and Pinnell and a lot of LLI kits during that time.

The transition that we first made with Schools Cubed was that our principal now had to make the master schedule. Teachers were not in charge of that anymore. That ensured that our literacy blocks were put down at a certain time, and so when an evaluator was to walk into your classroom with that schedule, you should be teaching your ELA block when you said you were teaching that ELA block.

Anna Geiger: Gotcha.

Candice Johnson: Because a lot of times that was a problem.

Our 21% proficiency was very low. As a school who was deemed high need at that time, we moved into 120 minute literacy block.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Candice Johnson: We had to invest the time in to make the changes. Since then, we've brought it down to 90 minutes that we're rolling into this year because we've seen great growth and success, but that was a transition that we had to make. So fidelity to the master schedule was important.

The next part was pacing. Within our block, we really tried to base the block off of the five pillars, and starting in a very specific order. We're going to start with phonemic awareness, we're going to roll into phonics, vocabulary, comprehension, and then really the belief is that fluency and oral language development, that should be woven into all of the components that we're doing. We should see that everywhere. It's not its own component.

The belief is if your literacy block starts at 8:30, and I know when you came to visit my school, I'm like, "No, we start at 8:30!" If you are not on your pacing, if you have too many kids that need to use the restroom and you take a classroom break, and then you come back, you're eating time, and so we had to be really critical about sticking to that. It was a really hard adjustment at first because we were never clock watchers, I guess, if you want to call it that. But then we got into a groove and to a pacing, and we started to see a difference with that.

Anna Geiger: So in a way, you're accepting this urgency of this situation, right?

Candice Johnson: Absolutely.

Anna Geiger: And urgency requires absolutely that we're sticking to the time that we've committed and we're not letting other things suck time out of it, which is hard for teachers because so many things can suck time out, right? How did you help the teachers stay on track with that?

Candice Johnson: One of the things that changed within my role when Pati and her team came in, the role evolved into more of an instructional coaching role. Another very profound thing that was said to me by my coach, Jill, who we worked with, is... The first time we ever met her, she sat my administrator and myself down, and she really clarified those roles. She looked at me and she said, "Candice, you are the coach. You are the cheerleader. You are the grower. You are going to go into classrooms once a week, and you're going to watch those teachers, and you are going to be their best friend, giving them the advice and the feedback that they need."

By feedback, what I learned was being able to transcribe what I was seeing so that a teacher could read it back, but then providing them some feedback in terms of, let's reflect on some things. I'm going to ask you some questions, and we'll develop from there.

Then she looked at my administrator and she said, you are also a grower, but you are the evaluator. That is very different from being the coach, the grower.

The distinct differences between us are that I really had to form relationships and trust with teachers for them to be able to accept feedback. It is very scary to have someone like me walk in and sit in the corner or sit down next to your students and watch you teach. That was a very rough start to our journey because it had never been done.

Anna Geiger: Sure.

Candice Johnson: It was only really accepted when the evaluator came in once in a while to do those evaluations. Whatever feedback or discussions that I have with teachers was never to go to my administrator. That was between me and the teacher, unless the teacher decided that they wanted to talk to the administrator about it.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Candice Johnson: Same thing with my administrator. Whatever she saw in her evaluations that was between her and the teacher.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Candice Johnson: We could have general conversations and say, "Hey, I'm seeing a common thread happening in our K-2. Maybe it would be nice if the two of us could go in together to do some observations and talk about some of those things, and do some reflecting on that tool with our universal instruction." That would allow us to have some conversations, but I think that really helped bridge a trustworthy relationship with myself and with the staff that I work with.

Anna Geiger: So you've talked about basically reestablishing of roles and understanding what everyone's job is, and then a handing of the schedule to the teachers versus teachers developing it on their own, and also this pacing, keeping on track with the schedule. Is there anything else that was a big shift for everyone?

Candice Johnson: Instructional routines. What you were doing within that time limit was really important, and it had to be purposeful.

School districts adopt programs, and sometimes we get too much training, sometimes we get too little training, sometimes we get no training. These textbooks are thick, and there's a lot of information in there.

One of the things that my teachers have come to realize is that we have to be really grounded in what we believe. As we made the shift to structured literacy and this body of reading research, we have to be up to date on our knowledge and be able to be consumers of a curriculum, rather than have that curriculum textbook be able to... Because it's a program, it can't tell us what to do. We have to be able to be educated professionals who can go in and say, "This is what's going to fit our needs for our community," and be able to pick and choose what that is. That was a really huge part in the instructional routines that we did.

Anna Geiger: To that, I would say, in the past, that may have been happening as well. People were just picking and choosing, but they didn't have the shared knowledge. Would you agree?

Candice Johnson: I would absolutely agree because there's a time limit, right? You could spend a full day trying to get all of the things done in that book. You have to pick and choose what you do, but I think it was based more on, oh, this is just what I want to do versus what my data is telling me what I need to do.

Anna Geiger: Exactly.

Candice Johnson: Because when I look at this classroom, each classroom every year is going to be different. They have different needs and different changes need to happen with that. But within those instructional routines, what Schools Cubed really brought us back to that were not strong at all in our school, was equity of instruction and making sure that all students were required to participate. No one gets to put their head down, no students are getting pulled out of the classroom.

During that time, we formulated what we refer to as focus walls that are really a great visual tool for both a student and teacher, but also someone like me who's walking into multiple classrooms in a day, or an evaluator who is coming in to know what your focus is of that day or that week and the purpose, your objectives.

We really started to dive really deep into Anita Archer and really understand explicit and scaffolded language. We had to develop very intimidating lesson plans. I think that was maybe something that started early on in those August dates that kind of hit us with the brick, is that we were going to now have to plan our lessons, very detailed, by the way, and submit those into a Google Drive where our administrator or myself could pull them up and follow along as you're teaching.

Anna Geiger: Sure.

Candice Johnson: That was a really hard shift for teachers too. At first, I'm not going to lie, I had my head down on my desk and I had doors slamming in my faces, and people didn't want to hear or see from me, but there was a relationship that grew over time.

I had an amazing team who was really open to listening to some of my crazy ideas, and they were willing to try them in their planning process, and then let me watch them teach it and give me feedback and say, "You know what, Candice, this was too much. We need to tone it down here. This isn't realistic. Or maybe we take a little bit of the planning out of this and shift it here where there's a lot more going on in this department that I need to focus on. This seems more routine, and I kind of got this piece." So yes, I would say it took about a year or two to really fold into that.

I'll also say, which is really interesting, when we first had Pati and her team come in year one, we moved to structured literacy still using our old programming.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Candice Johnson: So we were using all of the things we had used from Benchmark for years, but we had to really learn how to be consumers of that. Then in year two, we adopted Wonders.

Anna Geiger: Okay.

Candice Johnson: So there was some lesson plan changing there. We were feeling really good year one, and then year two came and there were more changes, but we were, I think, more ready for them within the instructional routines.

The other things that Schools Cubed really brought, you mentioned it earlier, is that urgency in that pacing, and we really honed in on our culturally responsive practices, and student management, and engagement. If students are not engaged, they are not learning.

We also really toned down teacher talk. Teachers view themselves more as a facilitator, as a coach, but we have to give kids time to be able to collaborate with each other and be able to have that think time to be part of that learning. That was very different for us.

We also learned how to engage students in frequent responses. We learned how to navigate turn and talk routines. We also went from picking on students who had raised their hands, because what we've found is that it's always the same kids and the expectations of learning are only going to the kids who are willing, and sometimes those aren't the kids who need it the most. So we kind of started a policy where we just don't call on hands, and we cold call and the students know that and I think they like it.

At first, it was a little different, but it keeps them on their toes and they're really excited, and we have procedures in place, right? You may call on a student who doesn't have an answer, and that's okay. But the system may be that we will say, "Okay, we're going to come back to you. We're going to jump to somebody else who's going to help us find that answer." Then that student's going to repeat that answer so that we can confirm that they have a better understanding. But we also like to set them up so that they can have maybe a partner talk before we do that cold calling as well.

Also, I think the last important thing for anybody who's listening, who teaches the real little ones who are very wiggly, and you're thinking 90 to 120 minute reading block, that's not sustainable. We had to, again, reflect and evolve into understanding that we had to build in movement breaks. We've had to be really strategic about when we're standing, when we're sitting, what movements they're doing, at what time. The kids really look forward to it and they really enjoy it, and you can see the engagement in the classrooms.

Anna Geiger: So you've basically doubled your numbers, but I know you're still working towards that 95%. Can you talk about what are your next steps to keep raising those numbers and helping more kids reach benchmark or exceed it?

Candice Johnson: One of the pieces that we have been evolving and learning and working on is understanding data. Data can be very complex, especially when it comes to students and the varying data points that we do collect. We started off in year one with a data system that really helped us see a bigger picture. Now what we're learning to do is to dive really deep into that data and really break apart what some of those categories mean. Let's take these results and let's use it to reflect on our teaching.

We're in that process of going slowly because it can be very complicated to understand those results and to think about the impact of maybe what we feel versus what our data is saying, because we might think we're doing amazing at teaching vocabulary, but our scores maybe weren't as high as those feelings. So we have to do some hard reflection and some navigating and go back to some of those routines, and really think about the progress.

Our kids are not the same that they were in this journey three years ago. They're growing, and those numbers are becoming more proficient. We have to evolve with those students and meet their needs where they're at. So I would say that's where we're at, really navigating that data right now.

Anna Geiger: Well there are so many things we could pick out of this episode. For teachers, or maybe administrators, who want to start making school-wide changes, but may not be at a point where they're able to hire someone, some things you talked about were being sure we understand everyone's role, having a system where if you hopefully have a reading specialist they have a schedule for visiting teachers and a time to provide that positive and helpful feedback. Like you said, that can be slow going at first, but slowly building that relationship, and then having expectations for what classrooms are doing at different times of the day.

I know that can be really hard for teachers because I know one thing I loved as a teacher was my autonomy, which I thought was a good thing at the time, but looking back, there was a lot I was doing that was definitely not supported by research in it, and I would've benefited from some leadership that helped me understand that.

Also, school-wide professional development that's shared versus you're going here, you're going there. We're all going to learn this, and here's what we're learning, and we're making time for that as well as providing it in a way that teachers can digest it. Then learning to own that data as a school, not just by classroom, but this is our data and working together on it. A lot of it, I think, comes down to the fact that we're not little islands. We're a whole community, and we're all responsible for everyone's success. Would you agree?

Candice Johnson: Absolutely. I think you really defined the work that we've done. That was beautiful.