Anna Geiger's Blog, page 28

March 18, 2021

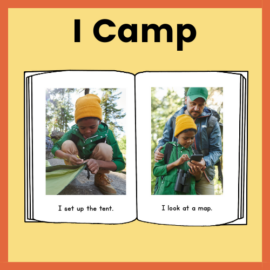

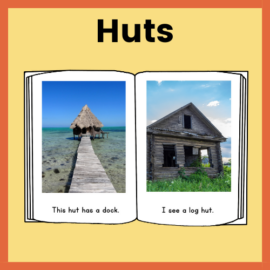

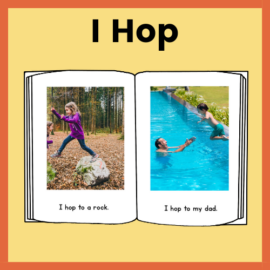

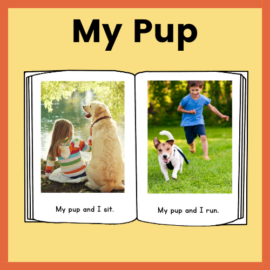

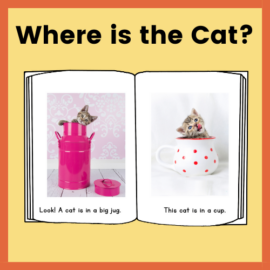

Free decodable nonfiction readers

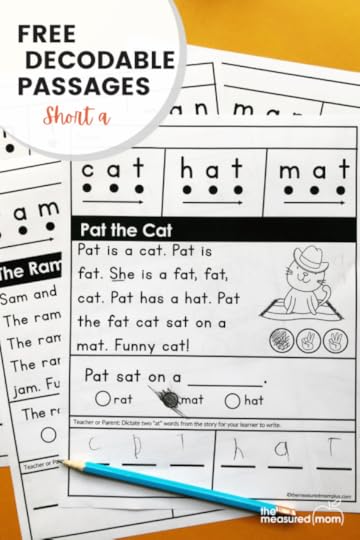

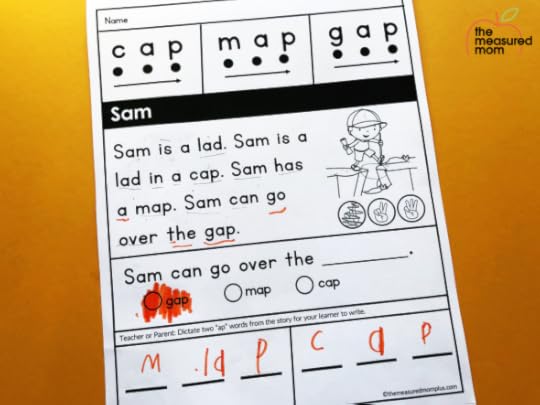

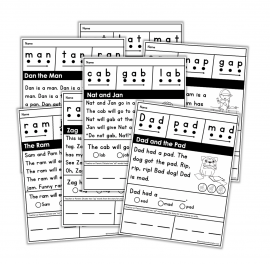

Are you teaching young children to read using fiction and nonfiction readers?

If so, it’s imperative that your learners get lots of practice with decodable text … text with words they can sound out and not guess using the pictures.

A decodable text allows readers to practice the phonics skills they have already been taught.In the past, I really resisted decodable readers.

I was sure they made no sense, would kill a love for reading, and got in the way of comprehension.

The fact is that there ARE some bad decodable books out there. But good ones are being created and shared all the time.

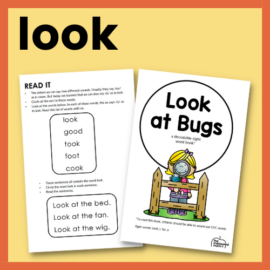

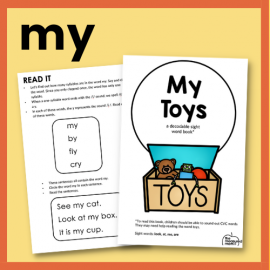

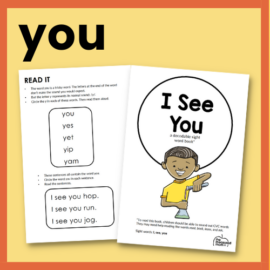

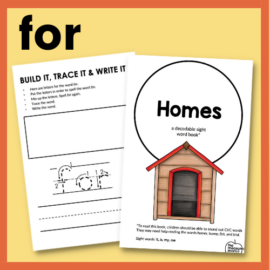

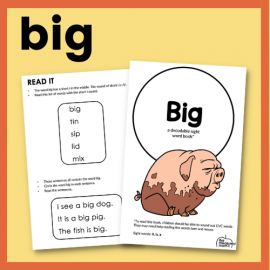

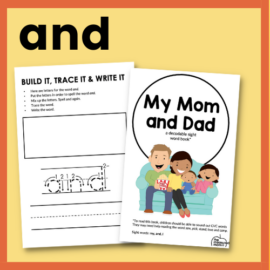

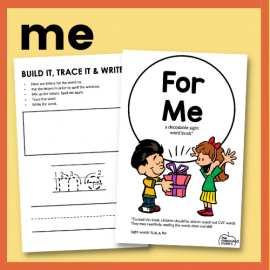

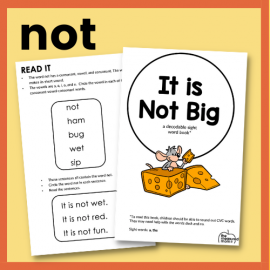

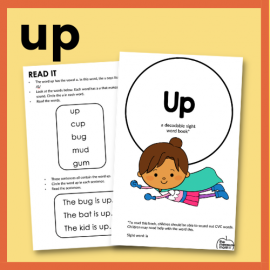

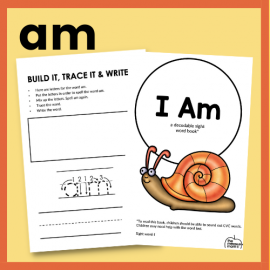

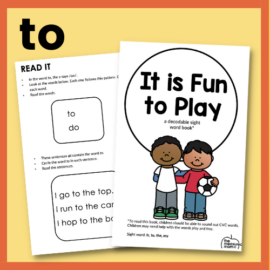

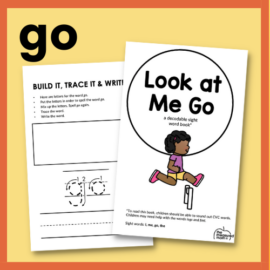

(You might have seen my sight word lessons with accompanying decodable books.)

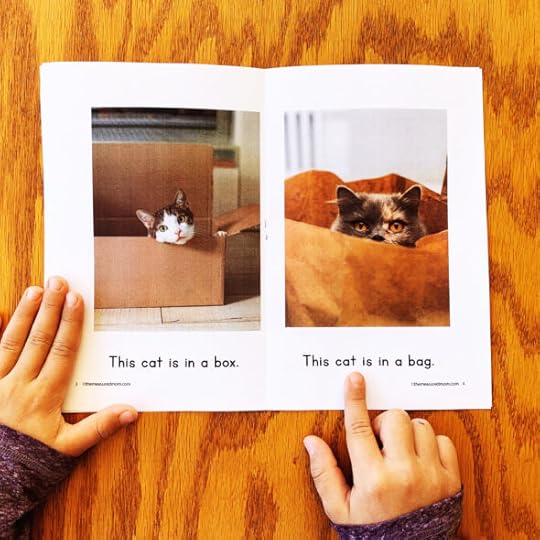

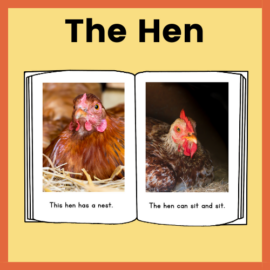

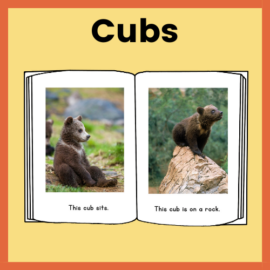

It’s tricky to find nonfiction readers that kids can sound out … so I’ve started creating very simple nonfiction decodable books for new readers.

I hope you’ll add my nonfiction decodable books to your list of favorites!

P.S. While I hope to create more of these books, this will likely be the extent of the free collection. Enjoy!

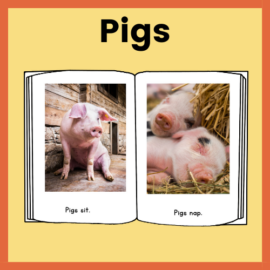

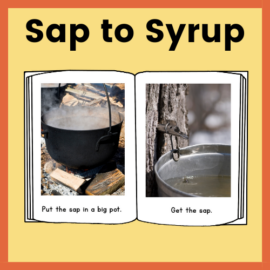

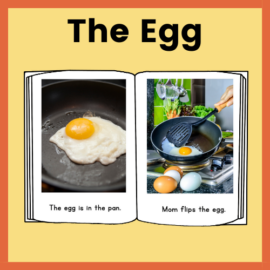

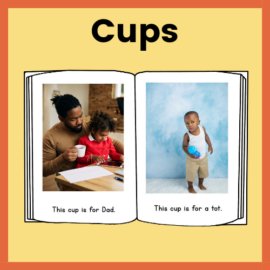

Click on an image to get a free decodable book

Looking for more nonfiction decodable readers? Consider Flyleaf. You can order a variety of decodable books in different genres. These are some of the highest quality decodable books that I have found.

The post Free decodable nonfiction readers appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Teaching preschoolers to read

We’re in the golden years of parenting.

Right now, in 2021, our family is between diapers and dating. And I love it.

Things are still wild and crazy (and LOUD), but that’s to be expected with six kids ages 5-13.

I admit that I don’t miss the Exhausted Years … the years I had a preschooler, baby, and toddler all at once.

I can’t count how many times I pushed a shopping cart with a baby seat in the cart, a toddler in the front, and preschoolers pulling on my coat.

Many shoppers couldn’t resist remarking, “You’ve got your hands full.”

These days, even though my eye bags are worsening, my wrinkles are deepening, and my hair is graying, I am getting sleep.

(And I am SO thankful for it!)

But you know what I do miss about those early years?

Teaching my kids to read.

Thankfully, I have one preschooler left. He’s five years old, and he’ll start kindergarten in the fall. I’ve been teaching him to read for a few months, and it’s been So. Much. Fun.

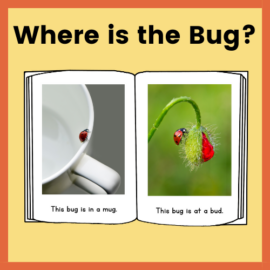

But is this necessary? SHOULD you teach your preschooler to read?

It depends.

You shouldn’t teach your child to sound out words until s/he has important foundational skills.

Then, and only then, should you move on to decoding words and reading decodable text.

How to teach preschoolers to read READ TO YOUR CHILD AS OFTEN AS YOU CAN

READ TO YOUR CHILD AS OFTEN AS YOU CANWhile reading to kids is not teaching reading, and does not guarantee that your child will be able to read successfully, it does build language comprehension … and this is a key piece of the reading puzzle. Browse all our book lists here.

TALK ABOUT BOOKS AS YOU READ ALOUDAs you read aloud to your child, ask thoughtful questions and have a discussion. This post about interactive read alouds will show you what kinds of questions to ask.

TEACH YOUR CHILD THE ALPHABET

TEACH YOUR CHILD THE ALPHABETSome people think you should start with letter sounds before teaching letter names, but I disagree … although there’s nothing wrong with teaching both at once if your child is up for it. Should you do letter of the week? Maybe. Be sure to use a fun, flexible curriculum, and teach multiple letters each week if your child can remember them.

TEACH LETTER SOUNDSSince I taught my kids their alphabet when they were two or three years old, most of them weren’t ready to learn sounds that early. So I taught letter sounds after they knew their letters. Here is my favorite printable for teaching letter sounds.

TEACH RHYMING, CONCEPT OF WORD, AND SYLLABLESThese are all elements of phonological awareness, which basically means that kids can play with sounds in words. Search my website for free resources, or buy these packs that have everything you need at your fingertips.

Use my Nursery Rhyme concepts of print packs to teach the concept of word.Use my Rhyming Activities pack to build this important skill.Use my Syllable Activities pack to help kids count and identify syllables in words.SPEND A LONG-ISH TIME TEACHING PHONEMIC AWARENESSPhonemic awareness is the ability to play with sounds in words. In recent months I’ve done a lot of study on this, and I’ve learned that this really is key in helping kids become proficient readers. The good news is that it’s easy to teach, and it only takes a few minutes a day. But you need to do this for some time, and it should continue even after you start teaching reading.

It helps to have a curriculum that you can follow. If you have a budget for it, consider purchasing Heggerty’s daily curriculum for preschool. Or download and print the free lessons from Reading Done Right. Looking for a more play-based approach? Get Marilyn Adams’ Phonemic Awareness curriculum.

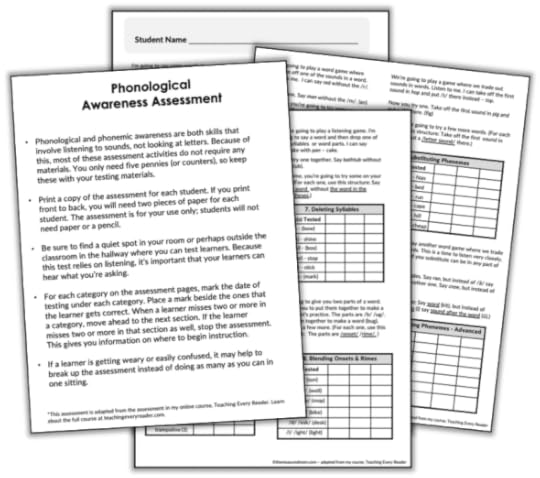

ASSESS YOUR CHILD’S PHONOLOGICAL/PHONEMIC AWARENESS

ASSESS YOUR CHILD’S PHONOLOGICAL/PHONEMIC AWARENESSGive your child a phonological awareness assessment to see if you should move on to teaching reading. I have a free assessment here. If you give the assessment and aren’t sure what your next steps should be, contact me via the Contact tab on the website. I’m happy to help!

TEACH BLENDING USING SUCCESSIVE BLENDINGReady to read? Awesome! It’s time to get started with preschool phonics activities.

I find it helpful to start with successive blending (sometimes called cumulative blending). The above activity worked wonders for my youngest two kids. You can get the free printable (and how to use it) in this post.

PLAY CVC READING GAMESAs your learner is catching on to sounding out words, play lots of CVC word games. CVC stands for consonant-vowel-consonant. I have found that diving right in with decodable texts in preschool can be overwhelming. Consider start with games to build confidence.

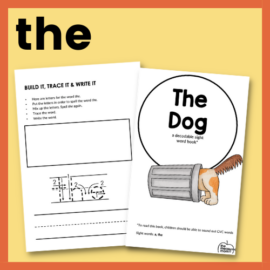

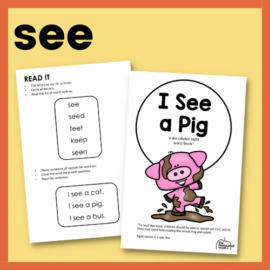

Our free matching games are great for beginners.Kids also enjoy our four-in-a-row reading games.Our word slider cards are another great tool.If phonemic awareness is solid, but sounding out words is still tough, consider using word families to start. I like our word building cards.TEACH A HANDFUL OF BASIC SIGHT WORDSHow are things going? Is your learner getting better at those CVC words? It’s not necessary (or even helpful) to teach loads of sight words to preschoolers. However, I recommend introducing just a few sight words in preschool so that your child can be successful with quality decodable texts. I recommend teaching these words in a multisensory way using my free sight word lessons and books.

Here are some good words to start with: a, I, see, the, is

START HAVING YOUR CHILD READ DECODABLE BOOKS“Decodable” means something different to every reader, because it means that the child has been taught the phonics patterns for most of the words.

In the past I’ve always resisted decodable books and recommended leveled readers instead. However, after a lot of study I realize that leveled books for our earliest readers are not a good choice. This is because they contain many words students could not read in isolation, so they must use context or pictures to figure out the words. In order for them to cement the words into their brains for future retrieval, it’s important that our students connect the sounds to the letters – in other words, sound them out.

This feels like slooooow going at first, when kids have to sound out every letter, but if they have a strong phonemic awareness foundation they will get it.

There are many decodable books to choose from. When starting with brand-new readers, I recommend books that move at a slow pace and have a variety of books for each level. Here are some of my favorites for very beginning readers:

Reading for All Learners: I See Sam booksThe Alphabet Series booksHalf-Pint Readers: These are very affordable. The stories are cute and simple, but they still have a plot. Highly recommended!Power Readers: These are very inexpensive because they are meant to be written in. Not as engaging as some of the other books, but good to have.TEACH OTHER PHONICS PATTERNS AND MOVE ONTO MORE CHALLENGING BOOKSIt may be best to keep going with CVC words until kindergarten. Developing automaticity with these words (so that your child can read each word without sounding them out letter by letter) is a wonderful goal, but it can take some time.

However, if your child is breezing through your CVC decodable books and is ready for the next step, teach beginning blends and digraphs. Then move on to CVCE words.

REMEMBER TO KEEP READING ALOUD TO YOUR CHILDSometimes, when we’re teaching our kids to read, we forget to set ample time to read to them and discuss the books. Since early books aren’t very “deep,” we need to use other literature to build vocabulary and comprehension.

I hope this post was helpful! Feel free to leave a comment below or send my team a message via the Contact tab if you need more support.

The post Teaching preschoolers to read appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 17, 2021

Sight word lessons and sight word books

Are you teaching sight words to young readers?

You’re in the right place!

In this post I’ll show you exactly how to teach sight words using hands-on lessons and free printable sight word books.

But first things first …

What ARE sight words, anyway?It depends whom you ask.

When reading researchers use the term sight words, they’re referring to the words that a reader recognizes instantly, on sight.

Sight words can also refer to words that our readers encounter frequently when reading. That’s the definition I’ll be using here. We want our readers to know these words instantly as they work to become fluent readers.

It’s time to rethink how we teach sight words.I used to think that when we teach sight words to young readers, we should teach them as whole words. This is why I used to share a collection of sight word books that taught the words through repeated exposure. (Those will soon disappear from the site and my shop.)

But research is telling us that this isn’t how the brain learns to read.

In order for kids’ brains to make new words a part of their permanent sight word vocabulary (the fancy word for this is orthographic mapping), they need to connect the sounds to the letters.

In other words? Sound it out.

Integrating high-frequency words into phonics lessons allows students to make sense of spelling patterns for these words. – readingrockets.org

I know what you’re thinking.

What about words that we CAN’T sound out?We call attention to the parts of the word that are phonetic (and there’s usually at least 1-2 of them). Then we teach learners to learn the tricky parts by heart.

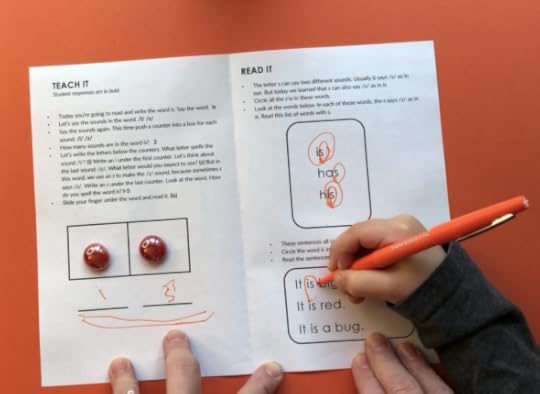

How to teach high frequency words to young learnersFirst, know our goal here. Our goal is not to teach loads of sight words as whole words, because kids need to connect the sounds to letters when reading. Instead, our goal is to integrate sight word learning with phonics instruction.Next, we need to make sure our learners are ready to sound out words. Not sure?

Check out this post.

All set? Great. Name the new word, and have your learner repeat it.Name the individual phonemes (sounds) in the word. For example, in the word is, there are two phonemes: /i/ and /z/.Spell the sounds. Call attention to any unexpected spelling. In is, we spell /i/ with i and /z/ with s.If possible, have your learner read related words. Has and his are great words to read alongside is because they are short vowel words with an s that represents the the /z/ sound.Have your learner read connected text. Connected text can be decodable sentences or books.Watch the video to see a sight word lesson in action …

How to teach high frequency words to young learnersFirst, know our goal here. Our goal is not to teach loads of sight words as whole words, because kids need to connect the sounds to letters when reading. Instead, our goal is to integrate sight word learning with phonics instruction.Next, we need to make sure our learners are ready to sound out words. Not sure?

Check out this post.

All set? Great. Name the new word, and have your learner repeat it.Name the individual phonemes (sounds) in the word. For example, in the word is, there are two phonemes: /i/ and /z/.Spell the sounds. Call attention to any unexpected spelling. In is, we spell /i/ with i and /z/ with s.If possible, have your learner read related words. Has and his are great words to read alongside is because they are short vowel words with an s that represents the the /z/ sound.Have your learner read connected text. Connected text can be decodable sentences or books.Watch the video to see a sight word lesson in action …Where can you find sight word lessons and decodable sight word books?

You’ll find a beginner’s collection below. Enjoy!

P.S. I look forward to adding more of these to our membership site, The Measured Mom Plus. I do not plan to add any more free books to this page. Learn more about membership here.

Sight word readers[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

The post Sight word lessons and sight word books appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 14, 2021

What’s wrong with three-cueing?

I never thought I’d be sharing an episode about what’s wrong with three-cueing. After all,��I’ve spent decades prompting kids to think about what makes sense, sounds right, and looks right when solving words!��Listen to find why I��(finally) changed my approach.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, and welcome to the 39th episode of Triple R Teaching! I'm going to be honest with you and tell you that out of all the episodes that I've done so far, this has been the hardest one to prepare. Two years ago, I never would have thought that I would be sharing a podcast episode called "What's Wrong With Three-Cueing". That's because, like millions of other teachers, three-cueing is something that I've held very close to my heart.

What is three-cueing? Well, three-cueing is a model that shows that three systems of cues work together as we make sense of print - semantics, syntax and graphophonics. It's often referred to as MSV because semantics has to do with what the text means, syntax has to do with grammar and we use S as the abbreviation, and graphophonics has to do with the visual cue, or phonics. I, like millions of other teachers, used these cues while I was helping children read.

On the surface this model makes perfect sense. In fact, Marilyn Adams, who is a long time specialist in cognition and education, wrote this way back in 1998. She said, "My concerns with the three-cueing system relate, not to the schematic, which I find wholly sensible in so far as it goes. The problem is in the application."

Ever since I was in graduate school in the early 2000s and in the many years of professional reading since, I have, until about six months ago, been a proponent of three-cueing! I was taught to use it as a way to help children solve unfamiliar words. When I was teaching beginning reading with my own kids and in the classroom, instead of focusing merely on sounding it out as a word to text skill, I helped children use the three cues. So I would say, "What makes sense?" "What would sound right?" "Use the picture for help." "Look at the first letter and use the picture for help." I rarely said, "Sound it out," because I had been taught that that should be the last resort. Instead I needed to focus on meaning, because of course, reading is all about comprehension.

Well, a few years ago, as I talked about in another episode, Emily Hanford published what became a viral article that attacked three-cueing. I want to share with you a quote from that article, "For decades, reading instruction in American schools has been rooted in a flawed theory about how reading works, a theory that was debunked decades ago by cognitive scientists, yet remains deeply embedded in teaching practices and curriculum materials. As a result, the strategies that struggling readers use to get by ��� memorizing words, using context to guess words, skipping words they don't know ��� are the strategies that many beginning readers are taught in school. This makes it harder for many kids to learn how to read, and children who don't get off to a good start in reading find it difficult to ever master the process."

Well, this flew in the face of everything that I had learned and believed, but I knew that I couldn't ignore it because a couple of readers of my blog had sent me an email or commented about it. So I brought this to a Facebook group over a year ago, a Facebook group of other educators. This is what I wrote, "I would love it if some of you would chime in on this for me. I promote the three-cueing system for reading with the use of level texts. Of course, I also promote focus phonics instruction. I have received blog comments from a couple of readers referencing this article which refutes the three-cueing system." I then included a link to "At a Loss for Words", by Emily Hanford. I continued, "In responding I have noted that some of the assumptions in the article are wrong, that the use of the three-cueing system inevitably means very little phonics instruction, for example. But I'm struggling with what to say to paragraphs like this..." And then I quoted from the article, "This idea that there are different kinds of evidence that lead to different conclusions about how reading works is one reason people continue to disagree about how children should be taught to read. It's important for educators to understand that three-cueing is based on theory and observational research and that there's decades of scientific evidence from labs all over the world that converges on a very different idea about skilled reading."

Well I told you in another episode that, to my surprise, the reading wars erupted right there in the comments! There were people who, like me, disagreed with the article, people who were thinking more about the article and were starting to study the science, and people who had effectively switched over to a more structured approach and were no longer considering themselves balanced literacy teachers.

I will never forget what one of the teachers wrote. She said, "Finding out that MSV is not in the best interest of reading instruction is sort of like finding out that one of your children is a serial killer!"

I know that sounds over the top and really dramatic, but you have to understand that for many, many teachers, myself included, it did feel extremely personal! This is what we used, this is what we taught, and we really believed that kids needed those three cues when they were reading those early books.

I find it very telling that in over eight years of running my website, themeasuredmom.com, in which 31 million different people have read my blog post, only a small number of people have actually commented or emailed me to say they disagreed with the idea of three-cueing. Would you like to guess how many people, out of 31 million, tried to reach out and tell me that they disagreed with three-cueing?

The answer is three. Three out of 31 million. I don't think I'm alone in misunderstanding three-cueing - I know I'm not! And I want you to know that even after this first discussion in the Facebook group, I still didn't think too much about it. It was in the back of my head, but I still thought that because some assumptions she'd made in the article felt wrong to me, I didn't think I had to take it seriously. But over time I started studying more about the science of reading, and I joined a science of reading Facebook group, and it was something that was said in there that really turned the tide for me. It really helped me start to think about things in a different way. Here's what it was, a reading specialist - formerly balanced literacy - agreed that using three-cueing with kids in K-2 often works! She said it works with these leveled books they have because the books are designed for them to be able to use picture cues and what would make sense to read the patterned, predictable texts. It seems to work.

That's what I needed to hear because people were telling me that it wasn't working and I was looking at my kids, and it certainly seemed to be working for all of them! Well, when she affirmed that it worked at first but then broke down later on, THAT'S what caught my attention. She said for many kids it works really well in K-2 because of the texts they're reading. But when they get to third grade or fourth grade, when they don't have those advanced phonics skills to tackle those long words, it breaks apart. And they can't just use the first letter anymore, of course, or find a small chunk, they need to be able to sound out the whole word. At this point many struggling readers, not all, but many have gotten into those habits of skipping words or using the picture. This isn't going to work anymore when you're reading a third grade science book, and those students start to hit a wall. That's what got my attention and that's when I decided to dive deeper into the science of reading.

I think one of the best places that you can go when you're trying to make a switch from balanced literacy to structured literacy, or even if you don't want to switch but just want to hear more, is to go to somebody who's been in your shoes. In Emily Hanford's article, she quotes a teacher who had been teaching with balanced literacy and now had switched over. Her name is Margaret Goldberg, I talked about her in another episode. When she was making the transition, she decided to try it out by teaching some of her kids to read their books with three-cueing and other kids to read the books by sounding out.

Here's what the article says about that, "It was clear to Goldberg after just a few months of teaching both approaches that the students learning phonics were doing better.

'One of the things that I still struggle with is a lot of guilt,' she said. She thinks the students who learned three-cueing were actually harmed by the approach. 'I did lasting damage to these kids. It was so hard to ever get them to stop looking at a picture to guess what a word would be. It was so hard to ever get them to slow down and sound a word out because they had had this experience of knowing that you predict what you read before you read it.'

Goldberg soon discovered the decades of scientific evidence against cueing. She was shocked. She had never come across any of this science in her teacher preparation or on the job."

If you would like to learn more about three-cueing and anything else in balanced literacy that we need to rethink, this is the book I recommend. This is brand new, it's called "Shifting the Balance", by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates. Down here you can see that it says, "Six ways to bring the science of reading into the balanced literacy classroom." This book is excellent, and they have a chapter in there all about three-cueing.

They address misconceptions that many teachers, including myself, had. One misconception that I had, was that you should start, when prompting kids to read an unknown word, with does it make sense? Because reading is all about meaning, right? So it makes sense we should prioritize meaning and use that cue first. Here's what they write in the book, "Sometimes science, as you know by now, is actually counterintuitive, and sometimes what seems logical simply does not match what really goes on inside a reader's brain."

Two episodes ago, I believe episode 37, I talked about how the brain learns to read. I tried to keep it really simple, and I would go check that out if you haven't seen it yet or listened to it. That episode will help you understand why using these cues to help kids solve words is harmful - it prevents them from adding words to their permanent sight vocabulary. So, as teachers, oftentimes when we say sight words, we typically mean high frequency words, and some people mean words you can't sound out. But to a researcher, that means a word that's permanently in the brain so that when a child sees it they can read it instantly. A lot of times, most of the time, those words aren't permanent right away. They have to sound the word out enough times until it becomes automatic.

So, my little guy, I'm teaching him to read, and now he can see "cat" and know what it is right away. But a month ago, he could not, he had to go /c/, /a/, /t/. If we teach kids to attack words by looking at the picture or thinking about what would make sense instead of directing them to sound out the word, we're preventing them from attaching the phonemes to graphemes - the sounds to the letters. They NEED to do that. It's a process that has to happen for those words to be mapped into their brains.

Now, can kids memorize some words without having to learn them by sounding it out? Sure, because we teach "the", before kids can sound it out. You really can't sound it out anyway. But the point is you can only do that with so many words. There's thousands, tens of thousands, of words that you and I read automatically, and then maybe a few more that you might encounter sometimes in a technical book or something, that you'd have to slow down very briefly to sound out. We didn't get tens of thousands of words in our mental vocabulary just by memorizing all of them or the shape of them. We learned them by attending to all the letters and sounding them out and that's how it works, those things connect to each other.

Here's a quote from the book again, "Teaching children to rely first and foremost on context for figuring out words is teaching them a process that will eventually fall apart on them." You can only memorize so many words and if you want to save a word for future retrieval you need to sound it out first.

Marilyn Adams, I talked about her earlier, has contributed a chapter in this book called Literacy for All. I really like this paragraph where she talks about the misuse of three-cueing. This is what she wrote, "If the intended message of the three-cueing system was originally that teachers should take care not to overemphasize phonics to the neglect of comprehension, it's received message has broadly become that teachers should minimize attention to phonics, less it compete with comprehension. If the original premise of the three-cuing system was that the reason for reading the words is to understand the text, it has since been oddly converted, such that, in effect the reason for understanding the text is in order to figure the words."

So it's backward, isn't it? We don't have to throw away MSV entirely, but we need to think about it entirely differently. Instead of thinking of it as three different cues that kids can use to solve words, we want them to solve words by sounding them out. But we want them to cross-check by thinking, does it make sense? Did it sound right?

We will get into all of this more in a future episode, but now we have to think about what's next. So we know that MSV, teaching kids to attack words using those three cues, is a bad idea. But so what? What does this matter? Well, it matters because the kinds of texts you use are going to help them use the right cue, the sounding out cue. If you give them a text with all kinds of words that they can't sound out, then you have to use MSV. That's why next week we're going to talk all about leveled and decodable texts - pros and cons, when should you use them, are there limitations? I'm really excited to share that with you next week in episode 40.

In the show notes today, which will be live when this episode is repurposed for the podcast, I'm going to give you some links to some helpful resources. One of those is the "Shifting the Balance" book, which again, I HIGHLY recommend. It's very easy to read and very practical. I'm also going to link to Margaret Goldberg's blog, which she writes with a couple of other teachers, which I love to read because it comes from a place of love. She is not going to be talking down to you, but she's going to be talking about her transition from balanced to structured literacy. I find it very encouraging and helpful. I'll also link to the original Emily Hanford article and anything else that I think would be helpful for you, including some past podcast episodes that you can go back and review as you're thinking through this for yourself.

Thank you so much for watching or listening, and I can't wait to be with you next week!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Link to original Facebook Live presentationVideo presentationRecommended readsEmily Hanford’s article: At a Loss for WordsRight to Read Project blogLiteracy for All, Chapter 4: The Three Cueing System, by Marilyn AdamsShifting the Balance (amazing book!), by Jan Burkins & Kari YatesRecommended podcastsA Simple Look at How the Brain Learns to ReadWhat The Science of Reading is Based On

The post What’s wrong with three-cueing? appeared first on The Measured Mom.

March 7, 2021

What the science of reading is based on

There are a lot of questions about what the science of reading truly is.��Is it from a journalist?��Is the science brand-new?��How do we know that we can trust it? In today’s episode I’ll share the particulars!

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

I've heard a lot of opinions about the science of reading. Some people think it's the invention of a journalist who doesn't know what she's talking about. Others question if it's something we can really trust. Is this all brand-new science? Has it even been proven? In today's episode, we're going to talk about what the science of reading really is and why you CAN trust it.

Last week, we talked about what the science of reading is, and our definition is a body of basic research on reading. The research has been conducted for decades and has important implications for how we teach reading. Last week, we talked about the human brain and how it learns to read, and we made this really, really simple. It's actually quite complicated, but we put it in the most basic terms.

When you look at the brain, you should know that effective reading takes place in the left hemisphere. We've got something in the back of our brain we like to call the orthographic processor - it's not the scientific name, but it's where we recognize letters and words. Then towards the front of that left side of the brain, we've got the phonological processor, which is where we recognize sounds. Then sort of in the middle back, we have the phonological assembly region, which allows us to connect speech sounds with visual images. That's really important, because it's that part of the brain that helps us sort of connect the circuits - make the two parts work together.

Scientists have studied brains of people who are not strong readers, and they find that instead of having this well-developed phonological assembly region on the left side of the brain, they're doing a lot of their reading work on the right side of the brain, which is not efficient. The way that we can help strengthen this phonological assembly region is to teach kids to connect sounds to print. So we talked a lot about phonological awareness and then phonics and how we can help kids connect the phonemes - the sounds, to the written letters - the graphemes, through systematic explicit phonics instruction.

But this is just one part of the science of reading. Neuroscience is just one piece. If you join any conversation about the science of reading, almost inevitably two things are going to come up, and here they are: the simple view of reading and Scarborough's Reading Rope. Today we're going to talk about both of those things, the simple view of reading and Scarborough's Reading Rope.

We're going to start with the simple view. This is a theory represented by a mathematical formula, which defines the two basic domains that are required for reading comprehension to take place. It was proposed by Gough and Tunmer in 1986. I'm not sure about you, but in 1986 I was eight years old, so this happened long before I got into undergrad and before I got my master's degree in curriculum and instruction with a focus on teaching reading. Yet I never learned about the simple view of reading either in undergrad or graduate school! However, it's been around for a long time.

In fact, it's been supported by research many times over, and no one has been able to prove it false! That's really good to know, because I know for some people, they hear the science of reading, and because this is kind of just getting into the mainstream in the last couple of years, it feels like it's just a pendulum and is only a fad. But it's actually been around for a long time!

One thing, I think, no matter what side of the reading wars we might be on, we can all agree that reading comprehension is the goal of reading, right? We all agree that that's where we want our students to get. The question is how do they get there?

The simple view of reading shows us that reading comprehension is a product of decoding and language comprehension. So when we have both of those things, then reading comprehension can take place. It's really important to remember that this is a multiplication equation and NOT an addition problem, okay?

So when we think about decoding, we also think of that as just being word recognition. There are some things that have to be learned for that to happen. We want to teach phonemic awareness and phonics. So, again, phonemic awareness is that ability to play with sounds in words, and phonics is connecting those sounds to actual letters. Then we also want to build language comprehension, and that involves things like vocabulary and text comprehension. Text comprehension is a little more abstract, but that includes things like syntax, text structure, and other things.

Fluency then, is the application of decoding and language skills, the automatic application. So when children become automatic in their decoding and connecting the words they're reading to what they already know with language comprehension, that's when fluent reading can occur. These pieces together lead us to reading comprehension, which is, of course, the goal of reading.

Like I said, it's really important to remember this is a multiplication, not addition problem.

Let's take a look at some scenarios. I can think of myself when I took Spanish in high school a long time ago, about 25 years ago. I don't remember much of it now, to be honest, because that was a long time ago and I haven't used it. But I can still decode words in Spanish, because unlike English, they're relatively consistent in terms of the sounds connected to the letter, so it's pretty easy to "read Spanish" out loud.

If you gave me a page of Spanish text, I could read it to you, so you would probably give me a decoding score of one, BUT my vocabulary in Spanish is very poor. I probably know fewer than 50 words, so that would have to be assigned a zero. Therefore, even though I could read the words out loud, my reading comprehension would not be happening. It would be a zero. One times zero equals zero.

Let's think about another situation. Can you for a minute think about a student you have had who's very bright, who can have really strong conversations with you and has good vocabulary? When they listen to you read aloud, they're just totally into it. They can answer all the questions, but they struggle to get words off a page. In that instance, the child would have a decoding score of zero, and a language comprehension score of one, which unfortunately leads to a reading comprehension score of zero. It's really important that kids can decode AND have understanding of the language in order for reading comprehension to take place.

So you might say, "Who cares? That's interesting, but it doesn't matter to me. What am I going to do with that?"

I would say, well, it matters because not all children who have trouble reading, or who have trouble understanding what they read have the same problem.

I was talking to a friend of mine, a school psychologist, and she said that she often finds that when they have kids that come to them around fifth grade, struggling to read or to understand what they read, teachers often assume it's a comprehension issue. They focus on that instead of checking to see if it's a decoding issue. So the problem could be decoding, or the problem could be language comprehension. We have to be able to look through all the possibilities before we decide on the intervention. The simple view of reading gives us this big picture of what could be at play when kids are struggling to comprehend.

Now, you might be thinking about the simple view of reading and saying, "Okay, I've taught kids how to read, and it's not simple. It's not that simple. It's complicated."

To that, I would say I totally agree with you, and my only beef with the simple view of reading is that it's called "the simple view of reading".

Now, I know that the people who created it would not tell you that learning to read is simple. They're just trying to show all the big domains that all the sub-skills rest under. But it's really good to use something else next to the simple view of reading, and that is Scarborough's Reading Rope, because that's where we're going to see all the pieces.

Scarborough's Reading Rope was created by Dr. Hollis Scarborough in the 1990s, and it was published in 2001. Interestingly, she created this as a visual for the parents and teachers who were attending her presentations. She wanted to show them all the complexities involved in learning to read. It's so interesting to me that she actually designed this for people like you and me. At least I'm assuming you're like me, that you're not research-oriented. You don't spend hours and hours studying research articles in journals. We maybe read them occasionally, but it's not something we're heavily involved in. That's why she created the Reading Rope.

This is what it looks like - she drew this herself. It's two ropes that are becoming entwined together as the strands get tighter and tighter. So if you're listening to this on the podcast, you should go ahead and Google Scarborough's Reading Rope so you can see what I'm talking about here.

Interestingly, Hollis Scarborough created this completely separate from the simple view of reading. She was not familiar with it when she created this, and yet she also came up with two domains for proficient reading based on the research, word recognition and language comprehension.

So in the model, she labels each of these strands with the sub-skills of word recognition and language comprehension. Those are phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition. Those are the sub-skills of word recognition, and just to be clear, sight recognition does not mean memorizing lists of sight words. It means being able to read any word quickly and accurately, whether or not it's high frequency. So for my little boy who's learning to read, who's five years old, the word "cat" could be a word in his sight recognition. He recognizes that word instantly. Another word that could be in there is "the". That's not phonetic, and yet he can read that instantly as well. It's any word they can read instantly.

Talking about language comprehension, these are the things that are involved there, background knowledge, vocabulary, language structure, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge. So as you can see, learning to read is not as simple as the simple view of reading might lead us to believe. It's actually quite complicated. All of these things are part of it.

The rope helps us see the change over time in the relationships of the strands and bundles. So back to that visual, if you're looking with me on Facebook, you can see that the strands get tighter and tighter and tighter as reading becomes more skilled. So the word recognition becomes more automatic, the language comprehension becomes more strategic, and then as that rope becomes tighter and tighter, we get to skilled reading. Scarborough in an interview stated that the rope allows us to talk about a concrete thing, a rope made of strands, as a metaphor for what research has shown to be important about becoming a good reader. She also said if any of the strands get frayed, it can hold back the development of other strands and, by extension, eventually weaken the entire rope. She saw these as strengths of the model.

Again, you might say, "All right. Nice visual, but who cares? Why does this matter for me as a reading teacher?"

I say, "Good question." That's always something we should be asking when we're looking at things like this. It's important for a few reasons. One thing it does is it helps us find strengths and deficits in a proposed curriculum. So let's say you're looking at a possible reading program for your school, and you're saying, "Okay, so this curriculum has lots of decoding practice in it, so a very strong phonics component, but it's not really touching on phonological awareness." Well, if that's true, then you need to either reconsider the curriculum or supplement it. You might have a different curriculum which has really good language comprehension pieces, so it talks a lot about background knowledge and vocabulary and so on, but the decoding piece is really weak. It does not include systematic sequential phonics instruction. If that's the case, you're going to want to reconsider this program.

Having Scarborough's Reading Rope in front of you allows you to be more wise about programs that you choose. We can also use it to help us determine strengths and weaknesses of individual students so we choose the right intervention. This is just a really good, big picture view of all the things that are at play when it comes to becoming a skilled reader.

Here are some key takeaways for you today. To understand the science of reading, we should be aware of the neuroscience, which I talked about last week, the simple view of reading, and Scarborough's Reading Rope. We should know that these findings are not new and they have been proven time and time again. Now, it's true that for many of us, myself included, learning about this has been new. That could probably be a whole other episode about why we didn't know about this until now, but it's been around.

We should know that the science of reading continues to grow as more research is done. I don't think we're in the final iteration of Scarborough's Reading Rope. I think that things are going to be added and adjusted to it as scientists learn more about skillful reading. In the same way, we're going to learn more about how the brain learns to read, and that's going to add more information to what we know about the neuroscience of reading.

We should know that the science of reading is not just about phonics. It's actually a response to the reading wars, because both the simple view of reading and Scarborough's Reading Rope acknowledge that there are two parts, two domains, word recognition and language comprehension. Those are both necessary for students to become strong readers.

If you're hearing all that and you're saying, "Yeah, I knew that. I've been doing balanced literacy for a long time, and I totally understand that phonics and language comprehension are important, and that's why I teach both of them," I would say, "Well, that's exactly what I would have said six months ago," because that's certainly what I believed - that I was giving adequate attention to both. It's possible that you really are giving strong phonics instruction and you really are giving strong attention to language comprehension, but here's the problem...

The problem is something that is very prevalent in balanced literacy curricula, and that's called three cueing. If I say this and you want to run away because you love three cueing, just as I always have, stick with me just for a few minutes, okay?

For those of you that aren't familiar with three cueing, three cueing is the idea that children use three cues as they read, syntactic cues - grammar, semantic cues - what makes sense, and graphophonic cues - phonics, sometimes called the visual cue. Often when you hear teachers prompting children, especially beginning readers who are reading in those early-level texts, they will use cues like these. "What looks right? Does it sound right? Use the picture." They believe that in using all these cues, they're helping kids become skillful readers. I have certainly believed that. I've certainly taught that way.

The problem is that three cueing bypasses some really important things that need to be happening as children are learning to read, and we're going to get into all of that next week.

Thanks so much for joining me today for Episode 38 of Triple R Teaching. Next week, we're going to get deep into three cueing. I'll see you then!

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Link to original Facebook Live presentationVideo presentation

The post What the science of reading is based on appeared first on The Measured Mom.

February 28, 2021

How the brain learns to read

How exactly does the brain learn to read … and why should teachers even care? In today’s episode I simplify the science and share exactly why this understanding is important for K-2 teachers.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, Anna Geiger here, and I am continuing with our Facebook live series all about the science of reading! If you've been with me for the last couple of weeks, you've seen how I've talked about taking this big topic and breaking it down into little pieces. I'm doing it so they're not scary and so they show you what the science of reading is all about, and how it can help you improve what you're doing in the classroom.

This is Episode 37 of the Triple R Teaching podcast. If you're watching on Facebook, you're watching the live recording of what will become the episode when I put it on the podcast next week.

In today's episode, Episode 37, we're going to take a simple look at the brain and how it learns to read, and why this is even important. Why do you need to know it?

We're going to dive right in. What is the science of reading? The science of reading is a body of basic research on reading, and the research has been conducted for decades and has important implications for how we teach reading. I know a lot of people are hearing the phrase, "science of reading", and they think, what's that all about? Is it just another pendulum swing? Is this a brand new thing? It's actually been around for a long time, and we'll get into all of that in the next few weeks.

Last week, I told you that this week we were going to talk about the actual science, and I thought I was going to give an overview of all the pieces. Then as I started preparing it, I thought that's just a little too much to swallow at once! So we're going to take this piece by piece, and this week, we're just going to talk about the brain and how the brain learns to read.

Here's what we know about the brain and reading. Learning to read is not a natural process. So if you have ever read much about whole language or even been a whole language teacher, you may have heard that learning to read is natural - that if we surround children with the same things that we surround them with when they learn to speak, they'll learn to read. For example, if we're teaching kids to speak, we know that it's important to be talking to them, to surround them with language, and to have conversations. But many people have extended that over to the idea of teaching reading, and they say if we surround kids with lots of books and we read a lot to them, then they will naturally pick it up. Now, there are a small number of kids who do pick up reading without being directly taught, but it is only a small number, because the fact is, our brains were created to speak, and reading is a human invention.

So why is that important to know? Well, different parts of our brain work together as we read, so there's not one specific part of your brain that's the reading part. It's all different parts working together, and we have to train those parts of the brain to learn to read. The good news about the brain is it's able to change in order to learn new things. So when scientists look at the brain of someone with dyslexia, what they see is a brain that's not using all the parts efficiently. So the scientists say that our brains have plasticity. That means that a brain can be rewired, basically. This is good news for struggling readers. The right instruction can "rewire" the brain so that they can become good readers!

We know this stuff about the inside of the brain by using functional magnetic resonance imaging, FMRI, which you may be familiar with. Basically, it allows scientists to watch the neural systems at work as people read. So when you're using a part of your brain, more blood flow goes to that part. When they have people wear these special caps and sit in these little machines and they're reading, the scientists can look at their brain image and see which parts are basically lighting up. It reveals the parts of the brain that activate when we read.

Here's a picture of a brain here, and I promise you now, I'm going to get really, really, really basic. So I don't know about you, but I am not the kind of person who enjoys big technological explanations. My husband is really good at those, and my oldest son, who's 12 and just like him, is also really good at it, and both of them like to explain to me how things work. I usually start zoning out when they're telling me these things, because I just can't focus.

But if you're the kind of person who loves those big explanations, here's some really good books to check out. Mark Seidenberg's "Language at the Speed of Sight" has some good descriptions in there about how the brain learns to read. We've got "Overcoming Dyslexia" by Sally Shaywitz. Then we've also got "Reading in the Brain" - and I have tried so many times to remember how to pronounce his name - by Stanislas Dehaene. I may be wrong about that. But if you want the big, big specifics, these are what I recommend to you.

Let's go back, though, to my very simplified version. In the brain you could say we've got these parts that work together to read. You've got this part in the back. This is not the scientific name, but it's basically an orthographic processor, so it recognizes pictures, like letters and words. Then in the front of this left side of your brain, we've got the part that recognizes sounds, we could call it the phonological processor. Then kind of in the middle here, we've got the part that helps those two parts work together, and we could call it the phonological assembly region. It allows us to connect the speech sounds with the letters and the words.

This is all happening, as I said, in the left hemisphere, and that's really important to know. The left hemisphere is best designed for efficient reading. The reason why this is important to know is that in people who are struggling to learn to read, it's not happening in that part of the brain. It's happening on the other side! So if you're watching with me on Facebook, you can see this diagram of a brain of someone without dyslexia. You can see, as they're reading, that these parts are being activated. Scientists are finding that someone who has dyslexia when reading may not be activating this middle part very much, or this part over here in the back. Instead, what's happening is activity is going on in the other side of the brain, on the right side. That's what they're seeing in struggling readers. Their brains are not being efficient when it comes to reading, and it's slowing them down and impeding comprehension and all the rest.

So who cares? Why does this even matter? Why do I need to know how the brain learns to read? The reason that teachers should know this is because it has implications for teaching. Specifically, we have to know what to do to help this phonological assembly region get these other parts to work together. It's really important that we give the right instructions so that this develops! Otherwise, as I showed you in that other screen, we've got the two brains here, and someone with dyslexia isn't really using that middle part as much. We've got to figure out what to do to help them so that this part gets used more as they're reading.

So how do we do that? That's the big question, right? Well, some of you are not going to like my answer, and I know this because I did not like it myself! The answer is that the texts that we use are important. It means you cannot just be using leveled texts with brand new readers. If you are someone who does balanced literacy or guided reading, you may have been using levels like A, B, C, D with your early readers. Those books rely a lot on picture cues, so you might ask them what makes sense, what sounds right, and to use the picture. I've done that myself. I've told teachers to do that! But now I've realized that is NOT the best way to build that reading brain. It's not a good way at all, because instead of helping kids make connections between the letters themselves and the sounds, the phonemes, we're sort of asking them to do work in the right side of the brain. And that's what struggling readers do.

We want to help the left side of the brain have the right circuits firing when kids are reading, so we want to make sure that they're giving lots of practice reading decodeable texts. If that scares you, don't worry, because I'm going to talk about it in the future.

Our brains need explicit systematic phonics instruction and practice with decoding, not only in those decodable texts, but in our phonics lessons. If you're someone who's afraid of drill and kill, I'm totally with you there. I always have been afraid of it myself. I'm learning, though, that phonics instruction does not have to be drill and kill. It can actually be a lot of fun, as long as we figure out exactly what our students need to know and we have the right materials to do it.

Those are definitely things we're going to be addressing in future episodes of the podcast. I want to sum up really quickly what we talked about today. We were born to talk, but our brains were not created to read. Reading is a human invention, and we must train parts of our brain to read. The left hemisphere is the part of the brain best suited for reading. When weak readers read, we often see more activity in the right side of the brain, which is not what we want. So we want to train that left side of the brain with explicit systematic phonics instruction.

Now, today I talked to you about neuroscience, and that is only one small piece of the science of reading. There's a lot of other things to talk about, specifically the simple view of reading and Scarborough's reading rope. Those are things we'll be getting to in the next couple of weeks, but I didn't want to overload you with too much at once! I just wanted to give you a really simple look at how the brain learns to read and why our instruction is so important.

If you have questions about this or other comments, and if you're listening on the podcast, you can head to the show notes, themeasuredmom.com/episode37, to give me some feedback. I'm definitely interested in what you're thinking.

Thanks so much for listening, and I'll talk to you again next week.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

Recommended reading Language at the Speed of Sight , by Mark Seidenberg Overcoming Dyslexia , by Sally Shaywitz Reading in the Brain , by Stanislas DehaeneLink to original Facebook Live presentationVideo presentation

The post How the brain learns to read appeared first on The Measured Mom.

February 21, 2021

My reaction to Emily Hanford’s article, “At a Loss for Words”

When I first read��Emily Hanford’s article, “At a Loss for Words,” I felt annoyed, angry and – in the end – dismissive. I’ve read the article many times since, and now my reaction is quite the opposite. Listen to find out what’s changed!

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello! My name is Anna Geiger, and if you're watching me on Facebook, you are watching the live recording of a future podcast episode for Triple R Teaching. Triple R Teaching is my podcast where I help teachers reflect, refine, and recharge.

We're in the second of our series all about the science of reading. Last week, I gave you a brief history of the reading wars in America. I promised you that this week, I would give you my reaction to the article that some would say reignited the reading wars. You could say it made the science of reading a movement.

This article first came to my attention the year it came out in 2019, and it's called, "At A Loss For Words: How a Flawed Idea Is Teaching Millions of Kids To Be Poor Readers". I have to say that when this article came out, I was not a fan. In fact, it brought out a lot of feelings in me, a lot of negative feelings! Let me read to you the very beginning of the article.

It says, "For decades, reading instruction in American schools has been rooted in a flawed theory about how reading works, a theory that was debunked decades ago by cognitive scientists, yet remains deeply embedded in teaching practices and curriculum materials. As a result, the strategies that struggling readers use to get by ��� memorizing words, using context to guess words, skipping words they don't know ��� are the strategies that many beginning readers are taught in school. This makes it harder for many kids to learn how to read, and children who don't get off to a good start in reading find it difficult to ever master the process."

I read that quote from the article, and I thought, "What does she know? She's a journalist. How could she tell me how to teach reading?"

That's exactly how I taught kids how to read, to use multiple cues for solving words, because otherwise it sounds like this, "The c-a-t h-a-d ..." and who can make meaning when they're reading like that? If you read books that allow them to have flow to the reading because the texts are predictable, and when they can use pictures to help them solve the words, then they can read more fluently and can make sense of what they read. It prevents them from being word callers, and it brings joy to reading, because who wants to sit and read decodable phonics books?!

So already I was feeling very defensive, what's she talking about? How does she know anything? Then I went on in the article, and she quoted some statistics from the NAEP where she said, "A shocking number of kids in the United States can't read very well. A third of all fourth-graders can't read at a basic level, and most students are still not proficient readers by the time they finish high school."

I read that and I thought, "Well yeah, that doesn't look good, but I've never been an expert on standardized test reporting." I could dismiss this, because I knew that where I taught the students were scoring much higher than the average, so my students weren't struggling to read.

Then in the article, she walks us through the reading wars, a little bit like I did with you last week. Then she zeroes in on the three cueing system, and that's the thing that gets me right in the heart! It gets a lot of teachers right in the heart, because it's something we believe in! She wrote, "In the cueing theory of how reading works, when a child comes to a word she doesn't know, the teacher encourages her to think of a word that makes sense and asks: Does it look right? Does it sound right? If a word checks out on the basis of those questions, the child is getting it. She's on the path to skilled reading."

I read it and thought, "Well yeah, that's true. I do teach kids to use the three queuing system because that's how they'll make sense of what they're reading. If they don't have the three queuing system, they have to read these contrived decodable texts that don't mean anything! It's going to stunt their reading growth, and when people listen to my kids read it...is....go...ing...to sound like this!

Well, then I read on. The article goes on to talk about the science of reading that was going on in the background while the three cueing system was becoming popular. It's the body of research that scientists have conducted on how we learn to read. I felt dismissive again. She's a journalist, they're scientists, and none of them are teachers in the trenches! How can THEY tell us how to teach? So I skipped over that and I kept going.

Okay, now she was getting me a little bit, because now she was quoting an actual teacher, a teacher and a literacy coach in the Oakland Unified School District. Her name is Margaret Goldberg, and she started out using the three cueing approach. That was how she first taught kids how to read, but she transitioned. In the article, it talks about her transition from teaching with leveled books to decodable books.

She's quoted as saying this, "I did lasting damage to these kids (the children who learned three cueing). It was so hard to ever get them to stop looking at a picture to guess what a word would be. It was so hard to ever get them to slow down and sound a word out because they had had this experience of knowing that you predict what you read before you read it."

I thought, "No, you're not hurting the kids! You're helping them read faster and more smoothly, and you're helping them make sense of what they read. When they can enjoy what they're reading instead of slogging through a decodable book, they will learn to love it! Besides that," I thought, "Emily Hanford talks like balanced literacy is without phonics, and that's not true! I did teach phonics when I taught balanced literacy in the classroom. And as my students learned to read more, they started using MORE phonics. They started paying more attention."

That's how I saw the article at first. I basically dismissed it. It was by a journalist who had talked about a lot of scientists - what did they know? - and I didn't agree with this one teacher who felt like the three queuing system was damaging to beginning readers. That's how I felt at first.

Well, that was a few years ago. I have been going back to the article many, many times, as different readers of my blog have directed me to it. My feelings of annoyance, anger, and dismissiveness have faded.

Why? Why am I starting to see this article differently? Well, I believe it started back in, I think it was 2020. I'm not 100% sure about that, maybe it was even 2019, but I posted in a Facebook group about this very thing. I think it was last summer, and I said, "Hey, teachers in this group," because it was a teacher seller group, "I've always taught reading using the three cueing system for beginning readers and leveled books, but now I'm hearing that some people don't agree with that and they keep sending me to this article by Emily Hanford. What do you think?" I tagged some people that I knew taught the same way that I did.

I was REALLY surprised at the conversation that happened in that thread after I posed that question, especially since I'm usually extremely quiet in this group. I usually just head in there to see what's new in the teacher seller world, and I don't participate very much.

Over one hundred people replied to me, and I've got to tell you, the reading wars erupted right there in the comment section! I did not know that teachers everywhere were dismissing the three queuing system now as being faulty. I had not heard that! I was really not familiar with the new science, or the science that's been around for a while that we're just finding out about, that was leading them to their conclusions.

Now I've been diving into the books and research myself. I've spent many evenings doing Google Meets with other educators. They're teachers like me who were staunch balanced literacy advocates, and are now not trying to throw everything from balanced literacy away, but, confronted with this science, are starting to make a shift in how they approach beginning reading.

Now when I read the article, instead of being afraid and having this tension in my chest and thinking I have to throw away everything I've ever done, I just listen. I listen to this paragraph right here.

"She's come to understand that cueing sends the message to kids that they don't need to sound out words. Her students would get phonics instruction in one part of the day. Then they'd go reader's workshop and be taught that when they come to a word they don't know, they have lots of strategies. They can sound it out. They can also check the first letter, look at the picture, think of a word that makes sense. Teaching cueing AND phonics doesn't work," she said. "One negates the other."

I started to think, "You know, she's got a point. If you teach them phonics over here, but then when you give them their books, they don't have to use the phonics, why would they stop to sound out words?"

Interestingly, this all happened at the same time that I began teaching my youngest to read. I noticed that when I use leveled books with him, which had very few words that he could sound out, he would start to read the pattern and his eyes would jump right off the page. It got to be that any leveled book I gave him, as soon as he figured out the pattern, that's all he needed. However, when I started using some engaging decodable books with him and taught him how to work through those words, his eyes were on every word in the book.

I read this quote in the article, "To be clear, there's nothing wrong with pictures. They're great to look at and talk about, and they can help a child comprehend the meaning of a story. Context ��� including a picture if there is one ��� helps us understand what we're reading all the time. But if a child is being taught to use context to identify words, she's being taught to read like a poor reader."

I read that and I thought, "Yeah, I'm starting to get it now." Kids DO use the cues to help them comprehend what they read, BUT the decoding needs to come first. First, they can decode the word, and after they've decoded it, they can think about whether that word makes sense or sounds right grammatically.

Now, when I read the article, "At A Loss For Words" by Emily Hanford, I don't get that tight feeling in my chest. I don't feel my wall go up or get angry at this journalist who has no right to say these things and cause division among teachers. Instead, I see a challenge for myself personally, to find out what the research REALLY says about our brains and how they learn to read and what implications that has for how we teach reading. I've learned I don't need to be worried. In the past, when I approached this article, it left me with a feeling of being scared and helpless. I thought I would have to throw away everything I've ever done. I don't think that now.

Instead, I think about how I can study all the books and articles that have been brought to bear recently and I can be excited about what I can learn as well as what I can share with you! I get excited about how what I'm learning and what you're learning will impact many, many students around the world.

Next week, I'm going to give you the research, the science that I alluded to in today's video, that forms the basis for the science of reading. I know some of you have expressed concerns about it such as, "Who is this from? Can we really trust this? Is this just a pendulum swing?" I want to address all those concerns for you and just help you see where the science of reading people are coming from.

If you hear science of reading and you get scared and your wall goes up and you don't want to listen, I would encourage you to tune in and just hear what I have to say. I promise you I've been in the exact same position you have, and we're all learning this together. It's not something to be afraid of. It's something to be excited about! So just come and have a listen. I'll be here next week, or you can check on the podcast for the episode next week. Thanks so much for listening. And I'll talk to you again soon.

Scroll back to top

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

powered by

The article that reignited the reading warsAt a Loss for Words, by Emily HanfordLink to original Facebook Live presentationVideo presentation

The post My reaction to Emily Hanford’s article, “At a Loss for Words” appeared first on The Measured Mom.

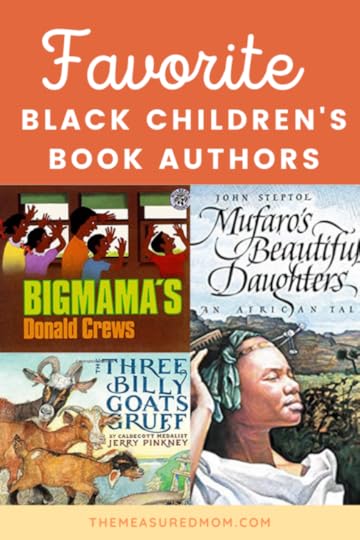

Favorite Black children’s book authors

I’ve shared dozens of book lists over the years. This month I’m sharing a collection of my favorite Black children’s book authors. I chose from the classics, but I know there are many newer Black authors that I’ve missed. Please share your favorites in the comments!

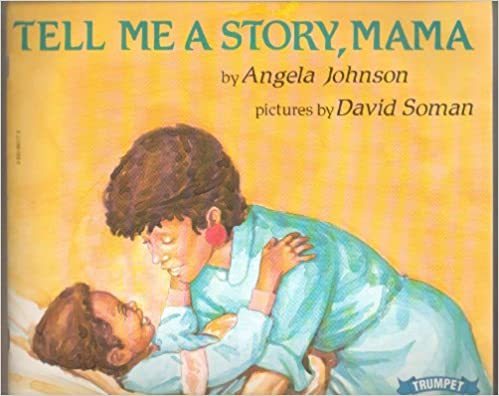

Angela Johnson

Angela JohnsonAngela Johnson, the author of over 4o books, is a definite favorite. Her first book, Tell Me a Story, Mama, is a wonderful book that can help spark ideas for children’s writing. Another favorite is��When I am Old with You,��about a little boy and his grandfather. Her books have just the right amount of text … and the stories of loving family members will tug right at your heart.

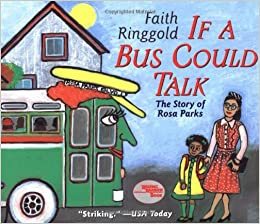

Faith Ringgold is another favorite African American author and illustrator. Her first book, Tar Beach, won the Caldecott Honor award in 1991. My favorite book of hers is long but beautifully written and illustrated: If a Bus Could Talk: The Story of Rosa Parks.

Jacqueline WoodsonJacqueline Woodson often tells about history through her storytelling. This is the Rope tells how Black people came to New York City. Coming on Home Soon takes place in World War II, when little Ada Ruth’s mama must go off to work while Ada Ruth stays with her grandmother. You may have read The Other Side, a wonderful story about two girls who become friends in a segregated South.

My favorite Black children’s author is Jerry Pinkney, who in addition to being a masterful storyteller is an incredible artist. I especially love his retellings of classic stories – like The Three Billy Goats Gruff, The Three Little Kittens,��and his nearly wordless book Lion and the Mouse. Your listeners will request them again and again.

Patricia C. McKissack died a few years ago, having written over 100 books. She wrote mostly nonfiction, focusing on issues of racism and Black history. She also write picture books unrelated to history, such as Flossie & the Fox and my preschooler’s favorite, The Honest to Goodness Truth. If you’d like to check out some of her nonfiction books, try the riveting Amistad: The Story of a Slave Ship.

John Steptoe wrote and illustrated one of my all-time favorite picture books, Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters. This is an absolutely stunning Cinderella story that has delighted all the children I’ve shared it with. (I should definitely try to find more of Steptoe’s books at the library!)

I’d never forget Donald Crews, an author and illustrator who has written and/or illustrated many classic picture books for young listeners, such as Freight Train, Bigmama’s, and Shortcut. His books are often used as mentor texts in writing workshop.

I’m sure I just scratched the surface!��What are your favorite children’s picture books by Black authors? Let us know in the comments!

The post Favorite Black children’s book authors appeared first on The Measured Mom.

February 14, 2021

What are the reading wars?

As we begin our discussion about the science of reading, we need to look back at the history of teaching reading in the United States. What exactly are the reading wars, and when did they begin? Where are we today? Join us for a brief and lively��history of the debate.

Listen to the episode hereFull episode transcriptTranscript

Download

New Tab

Hello, my name is Anna Geiger, and thank you for joining me for this live presentation. You are watching, if you're watching on Facebook, the recording of Episode 35 of the Triple R Teaching podcast, and we're going to talk about the history of the reading wars in America. Now why is this important? It's because this lays the foundation for the discussion we're about to be having in the next number of episodes all about the science of reading. We'll talk about what that is and why it's important or not important, and what does it have to do with you and your teaching?

Really, the discussion always tends to start with phonics, for better or for worse. Some people will tell you that the science of reading is not all about phonics, and they're absolutely right. It is not all about phonics, and we'll get into that in a later episode, but phonics tends to be the place where we have our big discussions and disagreements in America when it comes to teaching reading.

Why is that? Well, it has to do with a lot of things.

Let's start with this quote from David and Meredith Liben in their book, "Know Better, Do Better". "The disagreements over the rightful role, intensity of focus, and approach within the phonics universe is a central part of the reading wars." The reason is because phonics just happens to be kind of controversial, and that's because the discussion leads us to so many controversial questions, like how structured should the teaching of young children be? How much should children practice new skills? How and what should we assess, and who's accountable for children learning to read? These are all questions that come up a lot when we're talking about phonics, it's really the perfect storm!

Now I'm going to share this timeline with you; we're going to talk about the history of the reading wars in America. If you don't like history, I'll do my very best to make it interesting for you.

So, back in the 1800s, phonics instruction in America, or reading instruction, was whole-word and phonics-based. They used these little readers, often called the McGuffey Readers, and I think there were some other ones that were popular as well. The kids would be sitting in their little rows or their individual desks, and they would learn to read with these books that focused heavily on either single words, or words you could sound out, so it was a combination. Regardless, you might look at it and think it was pretty boring, because it did tend to look that way. It was a lot of drilling, a lot of reciting, and a lot of the kids just sitting there and responding to the teacher.

There was a reformer in America who didn't like what it looked like. His name was Horace Mann, and he was an American education reformer committed to public education. He did a lot of really great things! One thing he did was advocate that we support kids with positive reinforcement instead of corporal punishment, so he tried to get spanking and things like that out of schools. He also advocated training women to become educators, and as a sidelight, he did not think that slavery should be a part of the new territories.

We would say that a lot of things he did were positive things, but he had some interesting ideas about the alphabet. Here's a quote from Horace Mann himself, "Children would find it far more interesting and pleasurable to memorize words and read short sentences and stories without having to bother to learn the names of letters." He called the alphabet method "repulsive and soul-deadening to children."

That is so interesting to me, and I have to think that a lot of that is because of the way that teaching was done in those days. I know a lot of those early schools were called "blab schools", where the kids just recited, recited, recited. There wasn't a lot of give and take, there wasn't a lot of discussion, it was just the kids having to recite.

You could look at that and it might be pretty boring; it might look like drill and kill. That's how Horace Mann felt, and so he said, "We need to focus instead on whole words and sentences."

So he was kind of the father in America of the look-say method, which became really popular in the '30s through the '60s. I'm sure most of us have heard of the Dick and Jane books, maybe you even learned to read with those yourself. Dick and Jane books depend on kids learning a lot of words as wholes, so they just repeat those words over and over, lots of sight words.

The problem was that with the look-say method, it seemed that a lot of kids really weren't learning to read as well as you would hope. In 1955, Rudolf Flesch published his book, "Why Johnny Can't Read", and wow, did that ignite the reading wars big time! He said that kids weren't learning to read in America because we were not teaching phonics systematically. Instead, we were just kind of hoping kids would pick things up as they read these whole words. That book was on the bestseller list for 37 weeks in a row, and you could say that the publication of that book ignited the reading wars in America.

I had heard of it, I can't say I've actually read the whole thing, but I know that its tone got a lot of people angry. There were teachers that didn't like the book, and it just caused a lot of trouble in terms of discussion, troubling discussions with people getting upset.

There was a researcher in the '60s who said, "It's time that I sit down and do something about this." Her name was Jeanne Chall, and she was a psychologist, writer, and literacy researcher for many years, I think it was like 50 years. She sat down and she studied a lot of research so she could create a summary of it.