Michael Roberts's Blog, page 5

April 21, 2025

Abundance or scarcity?

Abundance is a new book that has been attracting attention and debate among mainstream economists and politicians. It aims to explain to Democrat members in the US why their party lost the election to Trump (narrow as that result was). The authors, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, writers at very liberal mainstream The New York Times and The Atlantic, respectively, argue that it was because the Democrats and supporters of ‘liberal democracy’ have lost their ability in government to carry out great projects that could deliver the things and services that working people (called the ‘middle class’ in America) need.

Why did the Biden administration fail, despite the infrastructure programme and despite the green climate change programme? Well, according to the authors, it was not to do with high inflation causing falling average real incomes etc. It was more because of the failure of Democrat administrations to get the US back to making stuff to meet people’s needs. Abundance, not distribution; growth, not stagnation. What was really needed was not more environmental controls or equality measures, but just more things – in abundance. You see, the Democrats and the liberal elite were only interested in things like regulations on pollution, or on housing projects, or on roads etc. This stood in the way of just allowing capitalism (or to be more exact, capitalist combines) to get on with delivering.

The authors outline many examples of how production, resources and projects could be done to raise living standards if only government regulations and middle-class nimbyism stood aside. Take housing, the authors argue that the housing crisis in America with rising rents, and unaffordable home prices, is due to a sheer lack of supply. This housing scarcity has been caused by restrictive zoning regulations and community vetos, which collectively prevent housing from being built where it is most needed, sending house prices skyrocketing.

Take global warming and climate change. Environmental regulations intended to stop the use of fossil fuels have actually inhibited the large-scale deployment of clean energy alternatives. For example, efforts to build energy infrastructure—from solar panels to the transmission lines needed to connect them to electrical grids—face fierce opposition, often from the same liberals trying to block housing projects.

Fellow ‘Abundist’ Matt Yglesias reckons these blockages to delivering the needs of working people is due to the liberal left adopting the interests of the upper-middle class elite, which has led to “the adoption of a kind of English gentry attitude that prioritizes ‘open space,’ quiet, good taste, and a harmonious social order over dynamism, prosperity, and the kind of broad, upward absolute mobility that is made possible by growth.” These interests are what stop governments and companies from delivering ‘abundance’.

A central argument of the authors is that it is these middle-class well-off, property owners who oppose getting things done. Projects that would make a difference are blocked by local participation and litigation from a narrow band of rich homeowners and interest groups. Abundance is a call to dislodge these concentrated interests, who are basically the friends and neighbours of the authors themselves.

There is much truth in the author’s argument that America is no longer delivering on basic needs; and it is falling behind in implementing important technologies. But is it true that why America is failing to deliver a decent, reasonably priced health service is because of too much regulation and nimbyism ‘(not in my backyard’)? Is it true that America has failed to deliver a high quality education service for young people without huge student debt because of too much regulation and cultural elitism? Is it true that America’s roads and bridges are falling apart because of planning regulations and legal actions?

Surely, the reason that America has the most expensive healthcare in the major economies with the lowest health outcomes is because it is the only major economy that does not have a health service financed by government and taxpayers free at the point of use. Instead, it has huge private health insurance companies and hospital hiking up fees and avoiding payments and services at every opportunity.

Surely, education levels have deteriorated is because public investment in education has been continually reduced and governments have imposed huge debt burdens on students that deter many from getting qualifications.

Surely, America’s poor infrastructure is due to the very low levels of government spending for decades. The US rail network is tiny, slow and inadequate not because of nimbyism and regulations, but because it has been left to the private sector to consider it and it is just not profitable. Compare that to the massive state investment in the rail network in China that has transformed transport and communcations there in just a decade or so.

When one of the Abundance authors, Klein, was asked if he favoured a universal public health insurance model, he said that it would be hugely preferable over the status quo, but making Medicare for All the centrepiece of a Democratic health care agenda was not ‘politically practical’. Klein argued that this was so because of the vested interests of the medical profession. But surely the main reason is because of the mighty power of the health insurers, drug makers and private equity-owned hospitals that lobby the political parties. And since when do we not advocate the right solution because it won’t be accepted by vested interests? Should people have not fought to get rid of slavery in 19th century America because it was not ‘politically practical’?

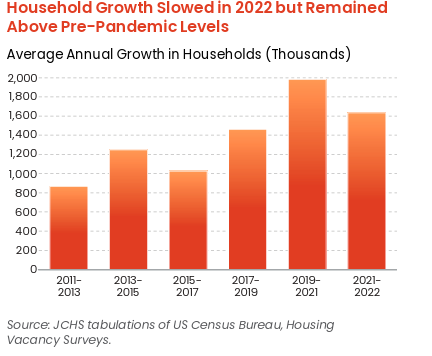

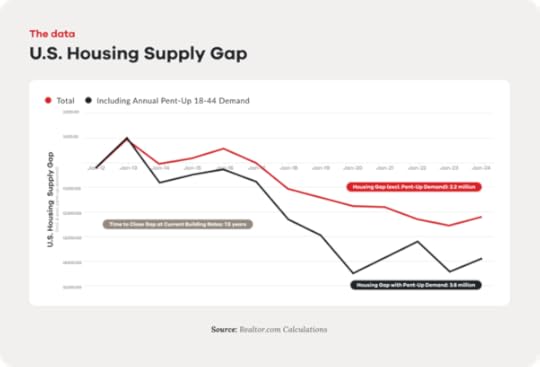

The authors make much of the housing crisis in America – a crisis that they blame on regulations, local opposition to planning etc. But whatever truth there is in that, it pales into insignificence with the real cause of the housing crisis. There are just not enough homes being built, even though US population growth is slowing and household formation is slowing.

Though estimates vary, experts put the US housing shortage at somewhere between 3.7 million and 6.8 million homes. If more homes were built and demand for homes was met, then the price of homes would fall or stop rising and incomes would start to close the gap on affordability. But at the current rate of build, it would take 7.5 years to close the current housing gap – in other words, never.

Why are not enough affordable homes being built? It is because the privately owned building sector does not want to build them unless they are profitable. More research has emerged over the last few years showing the link between the housing shortage and higher costs. So does America have a national house building programme funded by federal and state governments and built by a publicly owned national construction agency to solve this problem? No, of course not – this is America. Such a policy proposal would be ‘politically unacceptable’.

The abundance agenda appears to be an attack on the Trumpist right, but it is really an attack on the socialist left. The left is attacked for concentrating on inequality and discrimination and not on increasing production to meet working class needs. But what is the authors’ solution to getting more stuff – it is getting rid of regulations, even those supposedly there to protect our health, the environment and the planet. By the way, we hear the same argument in the UK from our ‘Labour’ government – namely the way to get millions of houses built is to do away with local planning and environmental regulations. Apparently, there is nothing wrong with capitalist system in the US (or in the UK), it’s just that it is hampered by petty regulations and bureaucracy.

Yes, we need more stuff and an ‘abundance’ of what working people need. But this book directs its sights towards planning regulations as the obstacle to abundance not to the real blockages imposed by the vested interests of the fossil fuel giants, the private equity moguls, the building and construction companies, and private sector control of America’s health and education.

Moreover, the authors have a naïve belief that new technologies can transform people’s lives if only they were freed up from unnecessary obstacles to implement them. The authors have a completely techno approach: “whether government is bigger or smaller is the wrong question. What it needs to be is better. It needs to justify itself not through the rules it follows but through the outcomes it delivers.” Take their view on AI. AI means “less work . . . [but] not . . . less pay. [It] is built on the collective knowledge of humanity, and so its profits are shared”. Really? Are the likes of OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, Nvidia etc going to share the profits of AI implementation with the rest of us? Intellectual property rights and monopoly control of new technology are the biggest obstacles to getting abundance. This book has an abundant title, but a scarcity of answers.

April 15, 2025

Argentina: anarcho capitalism to austerity

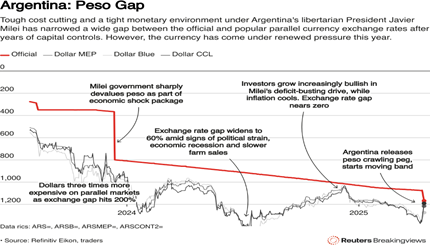

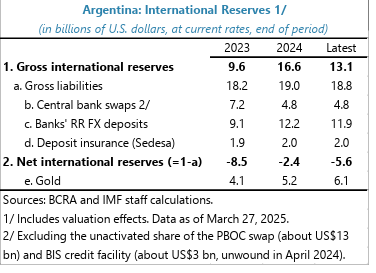

On Monday, the IMF announced that it had agreed to lend Argentina’s Milei government a further $20bn (on top of existing debts) to tide the government over in meeting its debt obligations and restoring its fast-falling foreign exchange reserves. The loan deal will release an initial $12 billion, with $3 billion more coming later in the year. The government says that it is set to receive $28 billion in 2025 alone, including the $15 billion of IMF money, $6 billion from other multinational lenders, $2 billion from global banks and $5 billion from extending a currency swap with China. Milei boasted that “What you’ll have is a mountain of dollars,”, with a target of doubling gross FX reserves to $50 billion.

With these funds, the government plans to ‘free’ the Argentine peso from controls and allow it to float freely within a moving band. The aim is expand the current band by 1% each month. The government and the IMF claim that this will eventually achieve “fully flexible exchange rate in the context of a bi-monetary system, where the peso and U.S. dollar coexist.” In other words, the financial speculators and investors will believe that the peso was strong enough to be fully convertible to the dollar without having to be devalued.

That has not been possible for decades, because of the huge dollar debts owed by the government and the lack of FX reserves to back the peso. Milei has targeted year-end for undoing FX controls, or sooner if the IMF speed up payouts. “The currency controls will no longer exist on January 1 (2026). Maybe sooner,” he said. As a result of the news, the ‘freed up’ official peso rate fell around 9% to 1,170 per US dollar, while, in contrast, the black market rate strengthened, so almost closing the gap between the official and informal rates that had widened sharply in recent years. Despite this, the peso rate against the dollar remains no better than when Milei came to power at the beginning of 2024.

Despite Milei’s boast, until the IMF came to the rescue, FX reserves had been dropping fast, with net reserves (ie after debt obligations and flows) at a negative $7bn. That’s not far short of the deficit that Milei inherited from the previous Peronist government.

Milei came into office in 2024, with the image of being a ‘free market’ libertarian, ‘anarcho-capitalist’. He was going to close down the central bank and ‘dollarise’ the economy and he was going to free up the peso and Argentine industry to market forces. But soon all this anarcho-capitalist talk melted away and instead Milei was forced to adopt the standard neoliberal economic package for an emerging economy in debt distress and with hyperinflation; namely vicious cuts in public spending and services alongside incentives to big business and foreign investors and, of course, the backing of yet another IMF package. Milei wielded a chainsaw to public sector and private sector jobs and in just a few months under Milei, Argentina faced the same job losses seen over four years of the previous right-wing president Macri’s rule.

The IMF under Kristalina Georgieva has been suitably impressed, holding lots of photo opportunities with Milei and writing “the country appears closer to a semblance of macroeconomic stability than at any point since the 2000s.” What the IMF likes is that Milei is committed to a ‘net zero’ government budget. Having ‘chain-sawed’ public services and sacked thousands of government workers, while raising employee social security contributions, the government aims for a surplus in the government budget (before interest payments) and an overall balance in 2025. It will go on squeezing government spending and raising taxes to run surpluses in future years – similar to the fiscal austerity programme that the EU ‘Troika’ imposed on Greece ten years ago to pay back its loans (it’s still paying), but this time with the enthusiastic support of the incumbent government.

In 2018, the IMF approved a $57 billion loan to the then right-wing government in Argentina – its largest ever to a single country – nearly $45 billion of which was disbursed. Most of this just financed capital flight of around $24 billion by ‘carry-trade’ speculators ie using the funds to buy foreign bonds. The rest was used to amortize roughly $21 billion in unpayable sovereign bonds – debt that eventually had to be ‘restructured’ in 2020.

Now the IMF is loaning yet more money, violating its own lending rules. That’s because unlike in 2018, Argentina now has a law – passed almost unanimously by both houses of Congress in 2021 – requiring congressional approval for any IMF financing program, with the aim of preventing future governments from borrowing massively in foreign currency without proper legislative oversight. But the Milei government has bypassed the law by issuing a Decree of Necessity and Urgency (DNU) – the Argentine equivalent of Trump’s emergency executive orders – to avoid Senate approval altogether.

And the IMF is happy to go along with this. That’s because the IMF wants the Milei government to survive the mid-term Congressional elections by being able to show that inflation has come down, the economy is booming and the peso is stable. As the IMF says in its report, this will be possible given “ongoing spending discipline, efficiency measures, and well-sequenced reforms of the tax, revenue sharing, and pension systems” and “building on the impressive ongoing efforts to deregulate the economy, the program seeks to deepen structural reforms to boost Argentina’s growth, including via its vast potential in energy and mining. Efforts will focus on further (i) strengthening product and labor market flexibility, and gradually opening the economy; (ii) improving state efficiency and its regulatory predictability; and (iii) enhancing governance and transparency, including by further aligning anti-corruption and AML/CFT frameworks with international standards.”

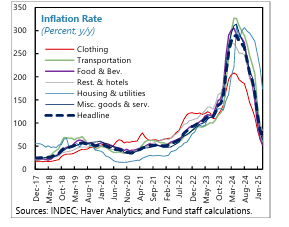

It’s true that inflation has fallen back from astronomical levels. That has been achieved by the slashing of government spending and holding the peso artificially above its real rate to the dollar, thus making imports cheaper. In effect, hyper-inflation was replaced by a major slump.

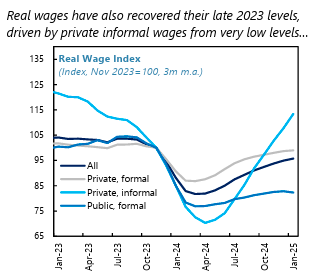

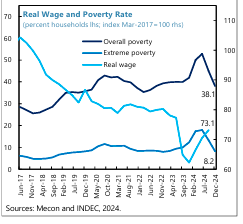

The inflation rate has fallen from 300% a year to around 50% (still high). But that has meant a rise in real wages in the last half of 2024, taking the average back to the end of 2023. But during the whole of 2024, average real wages still fell 12% and public sector workers took a hit of 20% with 30% for informal workers without rights etc. The rise since mid-2024 is entirely due improved incomes for informal workers in the private sector; public sector waged workers are still down 20%, private sector workers are down 5% – and all workers are still worse off than at the beginning of 2023.

During the Milei-induced slump of 2024, the official poverty rate hit a record 51%. That official rate has now dropped to 38%, due to a combination of the fall in inflation, the relative rise in informal wages and extra benefits in the universal child allowance and food support to cover inflation, aimed mainly at poor children and mothers. Without that, the World Bank reckons extreme poverty may have been 20 percent higher. Even so, the poverty rate is still as high as when Milei came to power.

Two-thirds of Argentine children under the age of 14 are living in poverty. Multidimensional poverty (measured as income plus lack of access to key welfare factors) increased inter-annually from 39.8 to 41.6 percent and within that figure, structural poverty (three wants or more) rose from 22.4 to 23.9 percent. In sum, 25-40% of Argentine families are in deep poverty. And there has been a further increase in inequality. The top 10% of income earners now earn 23 times more than the poorest decile, compared to 19 times a year ago. The fall in income reached 33.5% year-on-year in real terms among the poorest decile, but only 20.2% among the richest. The gini inequality index has hit an all-time high of 0.47.

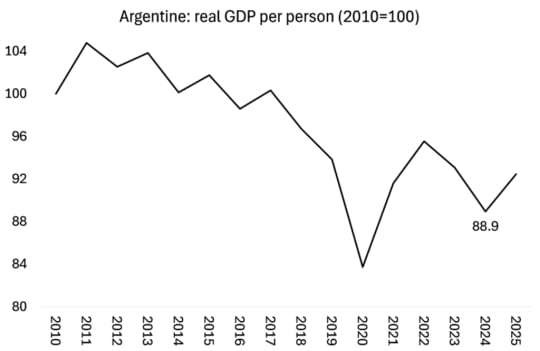

But from here, Milei and the IMF are full of optimism. According to the IMF, real GDP growth is expected to expand by about 5½ percent this year, and converge to about 3 percent over the medium term. But after the slump of 2024, such a rise in real GDP in 2025 would only take per-capita GDP back to the level of 2021, when the economy was emerging from the pandemic. And indeed, the per capita GDP index would still be well below its peak of 2011, some 15 years later.

Inflation is expected to fall to around 18–23 percent in end-2025 and reach single digits by 2027 as long as there is “a strict adherence to the fiscal anchor, along with a more robust monetary/FX regime with greater exchange rate flexibility to address shocks and strengthen aggregate demand management.” In other words, indefinite austerity.

Martin Guzman, a former economy minister with the Peronist bloc, said that the risk of a new IMF deal was that the funds would simply be used to ‘firefight’ the slide in the peso, eventually leading to greater debt loads. “The positive aspect of a new agreement would be the refinancing of the IMF debt, which begins to mature in September 2026. The negative aspect is more debt.” Contrary to Milei’s boast, Guzman reckoned that it was “highly unlikely” currency controls would be lifted soon because it would allow global firms to flee an estimated $9 billion that had been stuck in the country, pressuring the exchange rate down and inflation up.

The key to economic success in Argentina, as it is in all economies, is an increase in the productivity of labour through more investment in the productive sectors of the economy. All the previous IMF loans ended up being smuggled or invested abroad or used for financial speculation. Neither right-wing nor Peronist governments did anything to stop this speculative robbery of the Argentine people and resources.

There are only two major economic sectors that have flourished under Milei — finance and mining. They provide little in the way of tax revenue and employ relatively few workers (4% of the total). By contrast, the three major sectors that are still deep in recession are construction, industry and commerce, which account for almost half (44.5%) of the job market. Argentina’s biggest export sector and source of foreign exchange is agricultural products and this sector is suffering a wave of debt defaults.

Argentina could possibly get out of its mess if there were a boom in commodity prices, as there was in the early 2000s. Argentina is the world’s largest exporter of soya bean oil and meal, the number two exporter of corn and the third biggest exporter of soya beans. However, for now, soybean and corn prices are not very buoyant. Argentina has the world’s third-largest lithium reserves, making it a key player in the global energy transition. However, lithium prices have dived recently. Argentina also has considerable reserves of shale gas. The Vaca Muerta oil field is one of the world’s largest unconventional hydrocarbon resources, with an estimated 16 billion barrels of oil and 308 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and just coming on tap. But oil prices have fallen. And Trump’s 10% tariff hike on all US imports will just add to Argentina’s export woes.

April 13, 2025

Tariffs, Triffin and the dollar

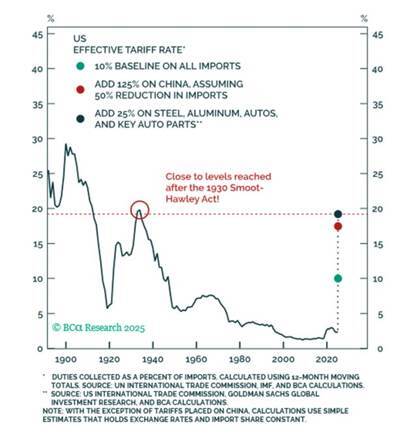

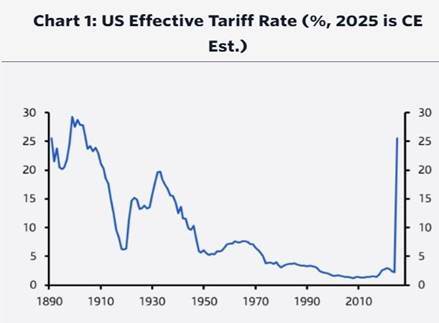

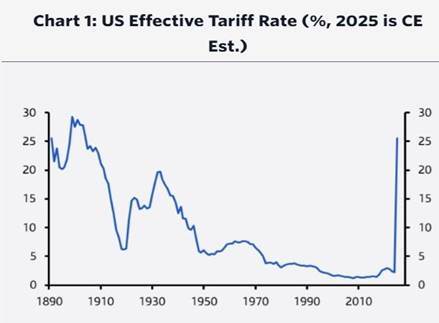

Despite Trump backing off from implementing his bizarre reciprocal tariffs imposed on every country in the world (including the penguin-only inhabited islands of Heard and McDonald), two thousand miles south west of Australia, the tariff war is by no means over. The ratcheting-up of tariffs on China still leaves the US total effective tariff rate higher than it was before Trump flinched. According to Stephen Brown at Capital Economics, Trump’s promise of 125 per cent tariffs on China puts the US’s effective tariff rate at 27 per cent.

Trump backed down because the bond market was showing signs of severe stress that could lead to a credit squeeze particularly for hedge funds that own a siginifcant stock of US bonds. If bonds dived there might well be bankruptcies for many companies, especially the heavily indebted so-called ‘zombie’ companies that constitute about 20% of all in the US.. Bankruptcies could then ricochet through the economy, leading to a financial crash and slump.

That was not only problem for Trump. The 125% tariff hike on imports from China potentially priced out exports of hi-tech consumer goods by American companies based in China. American companies like Apple who are the main exporters of i-phones etc out of China would have been hit hard. Roughly 90% of Apple’s iPhone production and assembly is based in China. If you take an iPhone for instance, less than 2% of its costs go to Chinese workers making the phone, while Apple makes an estimated 58.5% gross margin on its phones. Disrupting that supply chain would hit the US more than China. American companies screamed and and so Trump had to back down again. Now all consumer tech products imported from China, which are 22% of all US imports from China, are exempt.

The illogic of Trump tariff tantrums is also revealed by the fact the components going into i-phones and ipads are still subject to the tariff hike, just not final product. According to the US National Association of Manufacturers, 56% of goods imported to the US are actually manufacturing inputs with a lot of that coming from China. Price rises there will feed through to many final products. The exemptions offered to consumer technology goods apply only to reciprocal tariffs. All imports from China, including goods exempt from reciprocal levies, are still subject to an extra 20 per cent tariff. Moreover, Trump plans tariff hikes on semi-conductor imports which will hit the likes of Apple etc.

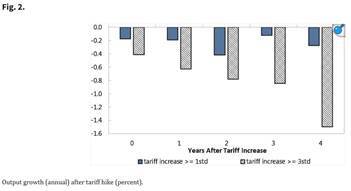

The US imports a lot of basic goods from China: 24 per cent of its textile and apparels imports ($45bn worth), 28 per cent of furniture imports ($19bn) and 21 per cent of electronics and machinery imports ($206bn) in 2024. A 100 percentage-point increase in tariffs seems certain to show up in higher prices for businesses and consumers. So instead of hurting China, Trump’s tariffs will hit the US economy even harder. China actually has very little dependence on exports to the US. They make up the equivalent of less than 3% of its GDP. American consumers and manufacturers will suffer sharp rises in prices – and indeed that is the experience of previous tariff programs. Furceri et al. (2020) found that a country’s GDP tends to go down after imposing a big tariff hike on imports. And the magnitude of the output decline increases as the years go by — the long-term pain is worse than the short-term pain.

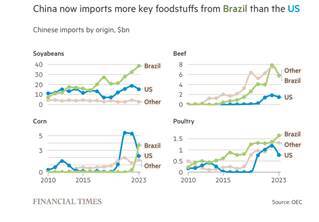

In the current US case, the significant drop in crude oil prices is already putting the profitability of US oil production in jeopardy. American farmers are losing badly in world markets as China switches its food and grain purchases to Brazil. Already, the US share of China’s food imports has collapsed from 20.7 per cent in 2016 to 13.5 per cent in 2023, while Brazil’s grew from 17.2 per cent to 25.2 per cent in the same period. Now Brazil’s beef sales to China climbed a third in the first quarter of 2025, compared with a year earlier while US agricultural shipments to China sank 54 per cent.

China accounts for 7 per cent of US goods exports, or 0.5 per cent of US GDP. According to Pantheon Macroeconomics, the hit to US exports from aggressive Chinese retaliation will outweigh any boost to GDP from the cancellation of “reciprocal” tariffs. Trump and his maga advisers argue that the tariffs revenues will be used to cut taxes to corporations and so boost investment. But according to the latest estimates, from the Tax Foundation thinktank – before Trump raised the stakes with a 104% tax on Chinese imports – would raise about $300bn a year on average, significantly short of Trump’s $2bn a day claim – basically peanuts compared to the loss of real incomes from the tariff measures.

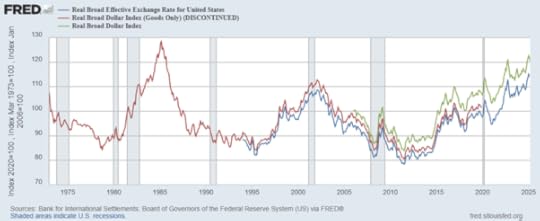

Financial markets remain nervous and uncertain with little sign of recovery after the huge losses recorded in the last few weeks. This has led to many analysts arguing that perhaps the days of dollar dominance are over and Trump has engineered a permanent fall in the dollar compared to other currencies and the end of the ‘exorbitant privilege’ that America has had in being able to issue dollars at will to pay for trade and investment.

Back in 1959, Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin predicted that the US could not go on running trade deficits with other countries and export capital to invest abroad and alsomaintain a strong dollar: “if the United States continued to run deficits, its foreign liabilities would come to exceed by far its ability to convert dollars into gold on demand and would bring about a “gold and dollar crisis.” Triffin argued that a country whose currency is the global reserve currency held by other nations as foreign exchange (FX) reserves to support international trade, is forced to supply the world with its currency in order to fulfill world demand for these FX reserves and that leads to running a permanent trade deficit.

Triffin’s so-called dilemma of a country providing the international currency losing out in trade has been taken up by Steve Miran, Trump’s White House economic advisor. Miran concludes all the countries running a trade surplus with the US must compensate the US for its ‘sacrifice’ in providing the dollar for trade and investment. But as Keynesian guru, Larry Summers, retorted: “If China wants to sell us things at really low prices and the transaction is we get solar collectors or we get batteries that we can put in electric cars and we send them pieces of paper that we print. Do you think that’s a good deal for us or a bad deal for us?” At the end of the day, Summers went on, who’s more “cheated”: the party doing the hard work of producing goods at very low prices on razor-thin margins, or the party that simply prints a virtually infinite amount of fiat money to pay for all this stuff?

Both Triffin and Miran have the story back to front. The US has been able to get cheap imports for decades and run a trade deficit to do so because countries exporting to the US have been prepared to take dollars in payment and indeed invest back those dollars into US government bonds or other dollar instruments. The trade surplus countries are not ‘forcing’ deficits on the US; it’s just that US exporters cannot compete at least in goods trade (the US runs a large surplus in services trade). Luckily for US companies and consumers, the surplus countries will take dollars in payment, up to now. If they did not do so, then US economy would be in real difficulty – just like many poor countries of the world without an internationally accepted currency are – and be forced to devalue the dollar and/or borrow at higher interest rates.

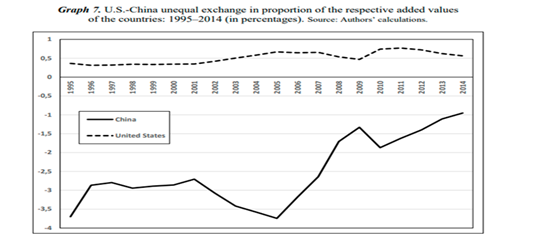

Under capitalism, there are always trade and capital imbalances among economies, not because the more efficient producer is ‘forcing’ a deficit on the less efficient, but because capitalism is a system of uneven and combined development, where national economies with lower costs can gain value in international trade from those less efficient. What really worries the US capitalists is not that surplus countries are forcing them to issue dollars; it is that China is closing the gap on productivity and technology with the US and thus threatens the economic dominance of the US.

Nevertheless, some mainstream economists accept Miran’s ludicrous argument and the Triffin fallacy. The Chinese-based economist, very much in vogue, Michael Pettis is one. Pettis argues that the likes of China have established trade surpluses because they have “suppressed domestic demand in order to subsidise its own manufacturing”, and so forcing the resulting the manufacturing trade surplus “to be absorbed by those of its partners who exert much less control over their trade and capital accounts.” So it is China’s (or until recently Germany’s) fault that there are trade imbalances, not the inability of US manufacturing to compete in world markets compared to Asia and even Europe.

Assuming no world governance and international cooperation on currencies, Pettis agrees with Miran: “the US is justified in acting unilaterally to reverse its role in accommodating policy distortions abroad, as it is doing now. The most effective way is likely to be by imposing controls on the US capital account that limit the ability of surplus countries to balance their surpluses by acquiring US assets.” So not tariffs on China’s imports, but controls on their purchases of dollar assets.

In essence, this is just another way of devaluing the dollar in order to weaken China’s export advantage and boost the US – a ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policy in disguise. Miran-Pettis offer a policy to lower the value of the dollar in the same way that Nixon did in 1971 in taking the dollar off the gold standard (the US reserve currency role encouraged the then US Treasury Secretary John Connally, when he announced the end of the dollar-gold standard in 1971 to tell EU finance ministers “the dollar is our currency, but it is your problem.”); and the US did similarly with the so-called Plaza accord in 1985, which forced surplus nations like Japan to hike interest rates and boost the yen, thus reducing Japanese exports. Now the answer to China’s export and manufacturing success is apparently to wipe out its dollar assets and weaken the dollar.

Unfortunately this policy won’t work. It did not save the US manufacturing sector in the 1970s or in the 1980s. As profitability fell sharply, US manufacturers located abroad to find better profitability in cheap labour economies. And this time, if the dollar is weakened, domestic inflation will rise even more (as it did in the 1970s) and US manufacturers far from returning home to invest will try to find other locations abroad, tariffs or no tariffs. If the dollar falls in value against other currencies, dollar holders like China, Japan and Europe will look for alternative currency assets.

Does this mean dollar dominance is over and we are in a multi-polar, multi currency world? Some on the left promote this trend. But there is a long way to go before the dollar’s international role will be trashed. Alternative currencies don’t look a safe bet either as all economies try to keep their currencies cheap to compete – that’s why there has been a rush to gold in financial markets.

The so-called BRICS are in no position to take over from the US dollar. This is a loose grouping of diverse economies and political institutions, with little in common, except for some resistance to the objectives of US imperialism. And contrary to all the talk of the dollar collapsing, the reality is that the dollar is still historically strong against other trading currencies, despite Trump’s zig zags.

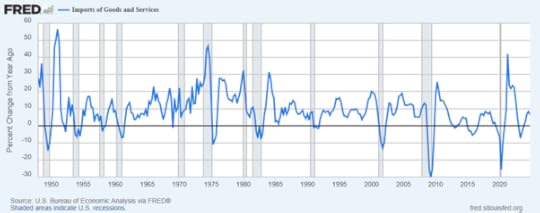

What will end the US trade deficit is not tariffs on US imports or controls on foreign investment into the US, but a slump. A slump would mean a sharp fall in consumer and producer purchases and investment and thus engender a fall in imports. Whenever the US economy has been in a slump (grey areas in graph below), the trade deficit narrows or disappears as imports fall sharply, while the dollar strengthens.

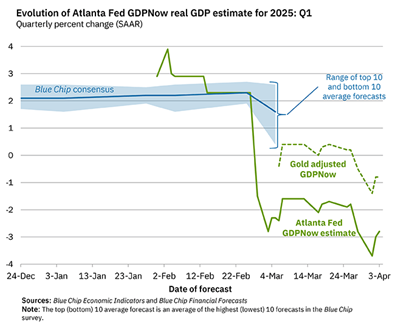

And the US economy is heading downwards as we go into the second quarter of 2025. Excluding gold purchases, the Atlanta Fed now predicts a 0.3% fall in real GDP in Q1 2025, but with domestic demand still growing slowly at 2% a year. But this is before the tariffs hit prices and production. The investment bank Goldman Sachs sees 45% chance of a US recession this year following the tariffs (with a GDP growth forecast of 0.5% for the whole year). Previously, before the tariff madness, GS was predicting “another solid year” of economic growth for the U.S. at 2.5% GDP growth. US inflation fell in March as the economy slowed and consumers reduced their purchases. But more than likely, inflation will turn up in the second half of this year while the economy slips further. Stagflation to slumpflation.

April 9, 2025

Trump’s slump

Today, President Donald Trump implemented his new range of tariffs on US imports called reciprocal tariffs. In addition to those announced last Wednesday (Liberation day), Trump included an extra levy on Chinese imports in retaliation to China’s decision to impose a 34% tariff on US imports, which in turn was a retaliation against Trump’s 34% hike on Chinese imports proposed last week. So US imports from China now have a 104% tariff rate, in effect a doubling. And as I write, China has announced a further 50% hike on US imports, taking Chinese tariffs on US exports to 84% in this tit-for-tat retaliation war.

Where is all this going? Well, it means a slump in production in the US and most major economies; and it means a revival of inflation, particularly in the US. This is madness, no? Well, as I said last February when all this kicked off, there is method in this madness. Trump and his accolytes are convinced that the US has been robbed of its economic power and hegemonic status in the world by other major economies stealing their manufacturing base and then imposing all sorts of blockages on the ability of US companies (particularly US manufacturing companies) to rule the roost. For Trump, this is expressed in the overall deficit in the goods trade that the US runs with the rest of the world.

He is not concerned, it seems, by services trade, where the US runs a surplus. It is manufacturing and commodities trade that concerns him. The aim is to close this deficit by imposing tariffs on US imports of goods. Using a crude formula for each country (the size of the US goods trade deficit with each country divided by the size of US imports from that country, then divided by two), Trump’s team arrived at the tariff hikes for each country. This formula is nonsense for several reasons: first, it excludes services trade, where the US runs surpluses with many countries; second, a tariff of 10% has been imposed even for countries where the US runs a goods surplus; third, it bears no relation to any actual tariff or non-tariff barriers that a country has on US exports; and fourth, it ignores the tariff and non-tariff barriers (of which there are many) that the US itself has on other countries’ exports.

These ‘non-tariff’ barriers may yet also come into play. Trump’s Maga trade envoy Navarro made it clear: “To those world leaders who, after decades of cheating, are suddenly offering to lower tariffs — know this: that’s just the beginning,” citing a laundry list of unfair practices he said included currency manipulation, “opaque” licensing, “discriminatory” product standards, “burdensome” customs procedures, data localisation and so called “lawfare” of taxes and regulation hitting US tech firms.

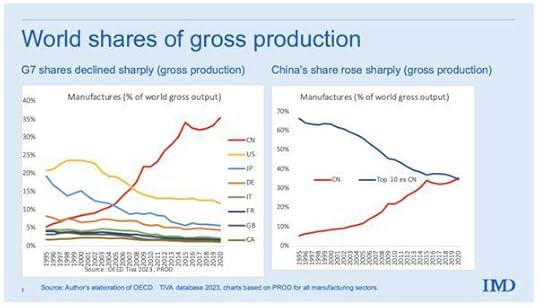

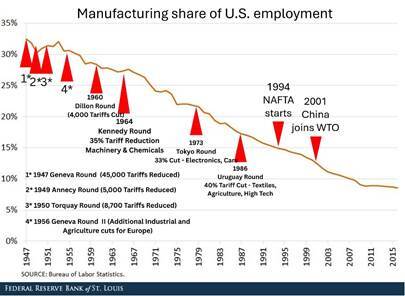

Trump’s aim is clear. He wants to restore America’s manufacturing base within the US. Much of imports into the US from countries like China, Vietnam, Europe, Canada, Mexico etc are from US companies based in those countries selling back to the US at lower cost than if they were based inside America. Over the last 40 years of ‘globalisation’, multi-national companies in the US, Europe, Japan moved their manufacturing operations into the Global South to take advantage of cheap labour, no trade unions or regulations and the use of the latest technology. But what has happened is that countries in Asia have dramatically industrialised their economies as a result and so gained market share in manufacturing and exports, leaving the US to fall back on marketing, finance and services.

Does that matter? Trump and his crew think so. Their eventual strategic aim is to weaken, strangle and gain ‘regime change’ in China and to take full hegemonic control over Latin America and the Pacific. To do that, they must have a strong and overwhelming military force. Trump has announced a record military budget of $1trn a year. But US arms manufacturers cannot deliver on that budget. So US manufacturing must be restored at home. Biden was keen to do that through an ‘industrial policy’ that subsidised tech companies and manufacturing infrastructure. But that meant a huge rise in government spending that drove up the fiscal deficit to record levels. Trump reckons that imposing tariffs to force American manufacturing companies to return home and foreign companies to invest in America rather than export to it is a better way. He reckons that he can increase manufacturing, spend more on arms, reduce taxes for corporations while cutting back on government civil spending and still keep the dollar stable – all with tariff hikes.

Is this going to work? It seems that some analysts, even leftist ones, think it might. It’s true that many semi-vassal states of US imperialism will probably try to concede to Trump’s terms: already South Korea and Japan are attempting to do so, and the UK too. But that won’t be enough to turn things round. Those who think Trump can succeed argue that, in the past, when the US opted to change the balance of global economic forces in its favour, it worked.

Nixon took the US off the gold standard in 1971 and established the dollar as the hegemonic currency with the ‘exorbitant’ privilege of being the only issuer of this currency, to pay for its imports and its capital investments abroad. But that did not stop the US losing market share in manufacturing through the 1970s.

And then in 1979, the then Federal Reserve governor Paul Volcker hiked interest rates to 19% to control inflation, which led to a deep slump both in the US and globally. The dollar rose so much that US manufacturing began to move its locations abroad – it was the beginning of the neo-liberal period. In 1985, the US got other trading nations to agree to strengthen their currencies against the dollar through the so-called Plaza accord. This eventually destroyed Japan’s industrial leadership built up in the 1960s and 1970s, but it did not work in restoring US manufacturing at home.

It is not going to work this time either, especially just through tariff hikes. US manufacturing can only compete in world markets because it has superior technology and so can reduce sharply labour costs in production. Although the US still has the second largest manufacturing sector in the world at 13% of world output (after China at 35%), US manufacturing employment has fallen sharply since the end of the golden age in the 1960s, mainly because US manufacturing profitability declined and technology replaced labour – not because of trade liberalisation. Indeed, the Trump’s team is talking about increasing manufacturing capacity at home through robots and AI and so delivering little extra jobs in the sector. So much for Trump’s claim that he was “proud to be the president for the workers, not the outsourcers; the President who stands up for Main Street, not Wall Street”.

The reality is that Trump cannot turn clock back to make the US the leading manufacturing economy in the world. That ship has passed. Globalisation has meant that the manufacturing value chain is now global, with components and raw materials spread across the world. As the Wall Street Journal pointed out: “Even if US-manufactured exports increased enough to close the trade deficit—an extremely unlikely event—and if employment grew proportionately, our manufacturing-workforce share would climb only from 8% to 9%. Not exactly transformational.”

If Trump wants to restore US manufacturing, the sector needs massive investment at home and US companies, already experiencing relatively low profitability outside the Magnificent Seven, are unlikely to oblige, except for military hardware paid for in government contracts. The reaction of Trump’s erstwhile adviser Elon Musk to the tariff hikes is symptomatic of the reaction of US big business: Musk attacked Navarro, calling him a “moron” and “dumber than a sack of bricks” after Navarro suggested the Tesla boss’s opposition to tariffs was self-interested (which indeed it is).

Despite the inevitable failure of tariffs as a solution to re-industrialising America, Trump seems set on going through with his protectionist strategy. This can only be a trigger for a new slump both in the US and in the major economies. It’s a trigger because already the major economies had been slowing to a crawl, even the US.

The manufacturing activity index (PMI) has been in contraction territory for over two years, while Americans’ inflation-adjusted earnings have gone nowhere post-pandemic (up just 1% in the last five years, as measured by real average weekly earnings). The much followed Atlanta Fed GDP Now model forecasts for US economic growth that in the first quarter ending March, the US economy contracted 1.4%, with domestic sales slowing to just 0.4% on an annualised basis. JPMorgan has slashed its 2025 GDP forecast from +1.3% to -0.3%, with unemployment projected to rise to 5.3%.

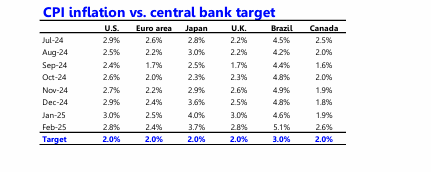

The ‘war against inflation’ is also being lost by the US Fed. The Fed’s target is 2% a year for US personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price inflation. In February, the PCE stayed at 2.5% and core PCE (excluding food and energy prices) rose to 2.8% a year. As I pointed out last February, in the major economies, there is an increasing whiff of stagflation ie low or zero growth alongside rising price inflation. And the impact of Trump’s import tariff hikes are still to be felt.

Indeed, the US Federal Reserve is now in a serious dilemma. Should it keep interest rates steady to try and control inflation; or lower them to try and avoid a slump? Prices in American shops will soon be rising sharply from imported consumer goods from Asia, including leather and apparel. Smartphones, laptops, and video game consoles are likely to become more expensive for US consumers, particularly as many of Trump’s highest tariffs are focused on countries such as Vietnam and Taiwan. Rice prices will rise by 10.3 per cent in the coming months, according to the Yale Budget Lab. The think-tank also forecasts a 4 per cent increase in the price of vegetables, fruit and nuts, many of which are imported from Mexico and Canada. Overall, the Yale Budget Lab estimates US households will spend an average of $3,800 more each year from 2026 as a result of tariff-induced inflation.

And back in ‘Main Street’, as Trump calls it, US companies are defaulting on junk loans at the fastest rate in four years, as they struggle to refinance a wave of cheap borrowing that followed the Covid pandemic. Because leveraged loans — high yield bank loans that have been sold on to other investors — have floating interest rates, many of those companies took on debt when rates were ultra low during the pandemic and have since struggled under high borrowing costs in recent years. Now their profit will be further squeezed by tariffs while interest rates stay high.

Usually when a recession is in the offing, government bond prices rise as investors look to a ‘safe haven’ from a stock market crash. But this time, bond prices and the dollar rate are also diving – as fears of rising inflation and worries about the security of holding dollar assets take over. The fall in the stock and bond markets are presaging the big fall in production and employment in the US and elsewhere (it is estimated that China’s current real GDP growth rate of 5% a year could be reduced by 2% points – it will be even worse for others). And a slump in the ‘real economy’ will lead to a further crash in financial assets.

Trump and his MAGA team believe that all these shocks are a price worth paying to restore US manufacturing hegemony. Once the dust settles, America will be great again, they argue. The destruction of world trade will have a ‘creative’ outcome (at least for America). But this is a delusion. US imperialism’s hegemony has been weakening as far back as Nixon in 1971 or Volcker in 1985. Trump’s slump will only confirm that trend.

April 4, 2025

Trump’s tariffs – some facts and consequences (from various sources)

The overall impact of Trump’s tariff hikes is to raise the average tariff rate on US goods imports to 26%, the highest level in 130 years.

The overall impact of Trump’s tariff hikes is to raise the average tariff rate on US goods imports to 26%, the highest level in 130 years.

2. The formula used to establish the tariff for each country exporting to the US is not related to any unfair taxes, subsidies or non-tariff barriers imposed by countries on US exports. Instead, it follows a simple formula: namely, the size of the US trade deficit with each country divided by the size of US imports from that country, then divided by two. An example: America runs a US$123bn deficit with Vietnam from which it imports US$137bn. So it is deemed to have trade barriers equating to a 90% import tariff. The US formula applies a reciprocal tariff of half that (45%), to reduce the bilateral deficit by half. Problem: Vietnam does not have a 90% tariff on US exports, so it cannot avoid a reduction in sales to the US by agreeing to reduce its ‘tariffs’ on US exports.

3. The moves will have a significant impact across the countries of the Global South. Some of the highest tariff rates are among lower-income developing countries in South and Southeast Asia like Cambodia or Sri Lanka.

4. Trump’s tariffs are only on goods imports, not services. The US runs a deficit on goods with the European Union countries, so Trump has imposed a 20% tariff on those imports. But there are no measures against services (about 20% of all world trade). The EU runs surplus on goods with the US, but a significant deficit in services (banking, insurance, professional services, software, digital communications etc) with the US. If services had been included, the US deficit with the EU would virtually disappear.

5. All countries, even those running a deficit with the US in traded goods, are subject to a 10% tariff. This also applies to countries without any trade with the US or any people (Diego Garcia, Antarctic…). The tariff on the UK is 10%, for example. So, although the UK goods trade is virtually in balance with the US ($58bn to $56bn), it will still take a hit from a loss of goods exports to its largest trading partner, the US. If Trump’s tariff formula for goods were applied to the UK, then there should be no tariff on imports from the UK. In contrast, if services trade were included, the tariff on imports from the UK would be 20%! Morgan Stanley reckons the new tariff regime could knock up to 0.6 percentage points off UK growth (which is virtually zero anyway).

6. Tariffs will substantially increase prices—US consumers will bear the brunt on a wide variety of basic foods and essential goods that physically cannot be produced domestically, with the poorest households being hit the hardest. American industry will struggle with higher costs for key intermediate supplies, machinery, and equipment, dwarfing any marginal benefits from reduced foreign competition.

7. Another example: the 54% tariff on China could result in a drop of $507 billion in imports – and China only exports $510bn in the first place. Trump’s China tariffs would reduce American imports by roughly 20%. This would cause a ‘supply shock’ similar to the pandemic period, leading to a US recession and/or inflation.

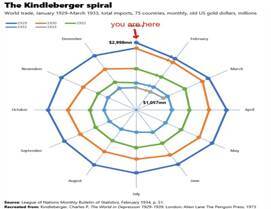

8. Retaliation by other countries will lead to a fall in US exports. In the 1930s, after the Smoot-Hawley tariffs were imposed, retaliation led to a 33% fall in US exports and spiralling down of international trade called the “Kindleberger Spiral”: a cycle where tariffs reduce trade, then retaliation reduces it further, then more retaliation, then first order effects on output, then second order effects, then more tariffs and retaliation, until global trade fell from $3 billion in January 1929 to $1 billion in March 1933.

9. A tariff trade war would hit the US economy harder than Smoot-Hawley, since trade is now three times as big a share of GDP as it was in 1929, and was 15% of GDP in 2024 versus roughly 6% in 1929.

10. US real GDP this year could be down by 1.5-2 percentage points and inflation could rise to close to 5% if these tariffs are not reversed soon (UBS forecast).

11. Falling trade growth from tariffs will lead to falling international capital flows, weakening investment and economic growth globally.

April 2, 2025

Liberation day

It’s not April Fools day (1 April). But it might as well be as later today US President Donald Trump announces another barrage of tariffs on imports into the US in what Trump calls ‘Liberation Day’ and what America’s voice of big business and finance, the Wall Street journal, has called “the dumbest trade war in history.”

In this round, Trump is raising tariffs on imports from countries that have higher tariff rates on US exports, ie so-called ‘reciprocal tariffs’. These are supposed to counter what he views as unfair taxes, subsidies and regulations by other countries on US exports. In parallel, the White House is looking at a whole host of levies on certain sectors and the tariffs of 25 per cent on all imports from Canada and Mexico which were earlier postponed are being now reapplied.

US officials have repeatedly singled out the EU’s value added tax as an example of an unfair trade practice. Digital services taxes are also under attack from Trump officials who say they discriminate against US companies. By the way, VAT is not an unfair tariff as it does not apply to international trade and is solely a domestic tax – the US is one of the few countries that does not operate a federal VAT; relying instead on varying federal and state sales taxes.

Trump claims that his latest measures are going ‘liberate’ American industry by raising the cost of importing foreign goods for American companies and households and so reduce demand and the huge trade deficit that the US currently runs with the rest of the world. He wants to reduce that deficit and force foreign companies to invest and operate within the US rather than export to it.

Will this work? No, for several reasons. First, there will be retaliation by other trading nations. The EU has said it would counter US steel and aluminium tariffs with its own duties affecting up to $28bn of assorted American goods. China has also put tariffs on $22bn of US agricultural exports, targeting Trump’s rural base with new duties of 10 per cent on soyabeans, pork, beef and seafood. Canada has already applied tariffs to about $21bn of US goods ranging from alcohol to peanut butter and around $21bn on US steel and aluminium products among other items.

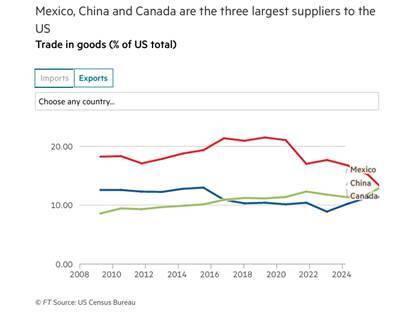

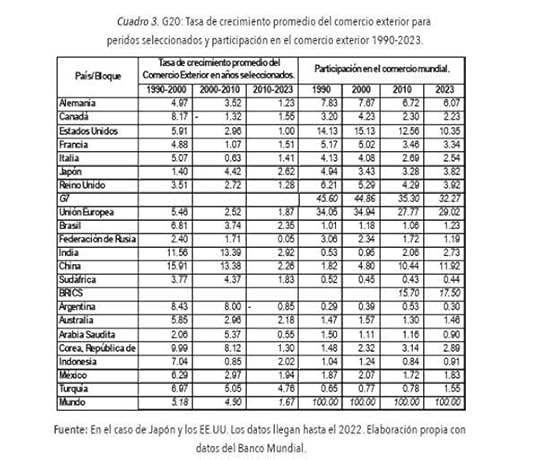

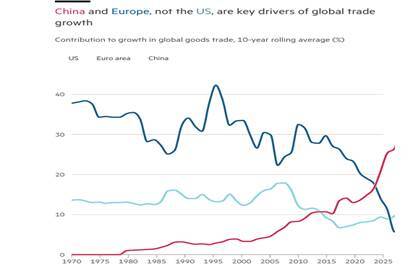

Second, US imports and exports are no longer the decisive force in world trade. US trade as a share of world trade is not small, currently at 10.35%. But that is down from over 14% in 1990. In contrast, the EU share of world trade is 29% (down from 34% in 1990) while the so-called BRICS now have a 17.5% share, led by China at nearly 12%, up from just 1.8% in 1990.

That means non-US trade by other nations could compensate for any reduction in exports to the US. In the 21st century, US trade no longer makes the biggest contribution to trade growth – China has taken a decisive lead.

Simon Evenett, professor at the IMD Business School, calculates that, even if the US cut off all goods imports, 70 of its trading partners would fully make up their lost sales to the US within one year, and 115 would do so within five years, assuming they maintained their current export growth rates to other markets. According to the NYU Stern School of Business, full implementation of these tariffs and retaliation by other countries against the US could cut global goods trade volumes by up to 10 per cent versus baseline growth in the long run. But even that downside scenario still implies about 5 per cent more global goods trade in 2029 than in 2024.

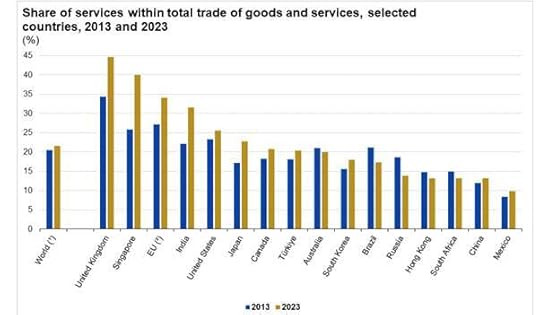

One factor that is driving some continued growth in world trade is the rise of trade in services. Global trade hit a record $33 trillion in 2024, expanding 3.7% ($1.2 trillion), according to the latest Global Trade Update by UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Services drove growth, rising 9% for the year and adding $700 billion – nearly 60% of the total growth. Trade in goods grew 2%, contributing $500 billion. None of Trump’s measures apply to services. Indeed, the US recorded the largest trade surplus for trade in services among the trading – some €257.5 billion in 2023 — while the UK had the 2nd largest surplus (€176.0 billion), followed by the EU (€163.9 billion) and India (€147.2 billion).

However, the caveat is that services trade still constitutes only 20% of total world trade. Moreover, world trade growth has fallen away since the end of the Great Recession, well before Trump’s tariff measures introduced in his first term in 2016, furthered under Biden from 2020, and now Trump again with Liberation Day. Globalisation is over and with it the possibility of overcoming domestic economic crises through exports and capital flows abroad.

And here is the crux of the reason for the likely failure of Trump’s tariff measures in restoring the US economy and ‘making America great again’: it does nothing to solve the underlying stagnation of the US domestic economy – on the contrary, it makes that worse.

Trump’s case for tariffs is that cheap foreign imports have caused US deindustrialization. For this reason, some Keynesian economists like Michael Pettis have supported Trump’s measures. Pettis writes that America’s “long-term massive deficits tell the story of a country that has failed to protect its own interests.” Foreign lending to the US “force[s] adjustments in the U.S. economy that result in lower US savings, mainly through some combination of higher unemployment, higher household debt, investment bubbles and a higher fiscal deficit,” while hollowing out the manufacturing sector.

But Pettis has this back to front. The reason that the US has been running huge trade deficits is because US industry cannot compete against other major traders, particularly China. US manufacturing hasn’t seen any significant productivity growth in 17 years. That has made it increasingly impossible for the US to compete in key areas. China’s manufacturing sector is now the dominant force in world production and trade. Its production exceeds that of the nine next largest manufacturers combined. The US imports Chinese goods because they are cheaper and increasingly good quality.

Maurice Obstfeld (Peterson Institute for International Economics) has refuted Pettis’ view that the US has been ‘forced’ to import more because mercantilist foreign practices. That’s the first myth propagated by Trump and Pettis. “The second is that the dollar’s status as the premier international reserve currency obliges the United States to run trade deficits to supply foreign official holders with dollars. The third is that US deficits are caused entirely by foreign financial inflows, which reflect a more general demand for US assets that America has no choice but to accommodate by consuming more than it produces.”

Obstfeld instead argues that it is the domestic situation of the US economy that has led to trade deficits. American consumers, companies and government have bought more than they have sold abroad and paid for it by taking in foreign capital (loans, sales of bonds and inward FDI). This happened not because of ‘excessive saving’ by the likes of China and Germany, but because of the ‘lack of investment’ in productive assets in the US (and other deficit countries like the UK). Obstfeld: “we are mostly seeing an investment collapse. The answer must depend on the rise in US consumption and real estate investment, to a large degree driven by the housing bubble.” Given these underlying reasons for the US trade deficit, “import tariffs will not improve the trade balance nor, consequently, will they necessarily create manufacturing jobs.” Instead, “they will raise prices to consumers and penalize export firms, which are especially dynamic and productive.”

As I have explained before, the US runs a huge trade deficit in goods with China because it imports so many competitively priced Chinese goods. That was not a problem for US capitalism up to the 2000s, because US capital got a net transfer of surplus value (UE) from China even though US ran a trade deficit. However, as China’s ‘technology deficit’ with the US began to narrow in the 21st century, these gains began to disappear. Here lies the geo-economic reason for the launching of the trade and technology war against China.

Trump’s tariffs will not be a liberation but instead only add to the likelihood of a new rise in domestic inflation and a descent into recession. Even before the announcement of the new tariffs, there were significant signs that the US economy was slowing at some pace. Already, financial investors are taking stock of Trump’s ‘dumbest trade war in history’ by selling shares. America’s former ‘Magnificent Seven’ stocks are already in in a bear market, ie falling in value by over 20% since Xmas.

The economic forecasters are lowering their estimates for US economic growth this year. Goldman Sachs has raised the probability of a recession this year to 35% from 20% and now expects US real GDP growth to reach only 1% this year. The Atlanta Fed GDP Now economic forecast for the first quarter of this year (just ended) is for a contraction of 1.4% annualised (ie -0.35% qoq). And Trump’s tariffs are still to come.

Tariffs have never been an effective economic policy tool that can boost a domestic economy. In the 1930s, the attempt of the US to ‘protect’ its industrial base with the Smoot-Hawley tariffs only led to a further contraction in output as part of the Great Depression that enveloped North America, Europe and Japan. The Great Depression of the 1930s was not caused by the protectionist trade war that the US provoked in 1930, but the tariffs then did add force to that global contraction, as it became ‘every country for itself’. Between the years 1929 and 1934, global trade fell by approximately 66% as countries worldwide implemented retaliatory trade measures.

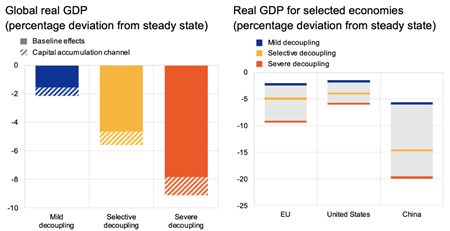

More and more studies argue that a tit-for-tat tariff war will only lead to a reduction in global growth, while pushing up inflation. The latest reckons that with a ‘selective decoupling’ between a (US-centric) West bloc and a (China-centric) East bloc limited to more strategic products, global GDP losses relative to trend growth could hover around 6%. In a more severe scenario affecting all products traded across blocs, losses could climb to 9%. Depending on the scenario, GDP losses could range from 2% to 6% for the US and 2.4% to 9.5% for the EU, while China would face much higher losses.

So no liberation there.

March 26, 2025

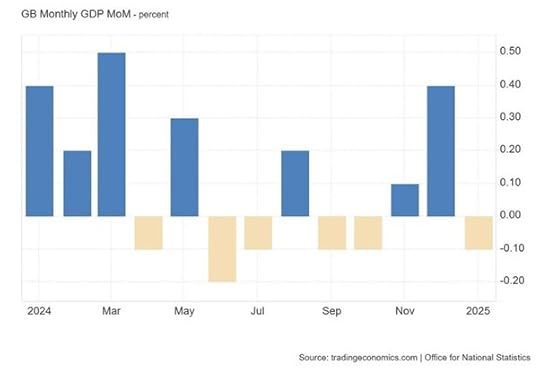

UK: still winter, no sign of spring

The UK government’s Spring statement on spending was as expected – really awful. First, Chancellor Rachel Reeves had to accept that the 2025 real GDP growth estimate will be half the rate previously forecast, halved to 1% from 2% by the government’s official forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). In addition, Reeves had to admit that the government’s inflation target rate of 2% a year would not be met until 2027 – and that assumes that Trump’s tariff measures don’t drive up costs in the meantime.

The UK economy remains in stagnation. Real GDP contracted 0.1% month-over-month in January 2025, worse than market expectations of a 0.1% gain. The largest downward contribution came from the production sector which fell 0.9%. The services sector also slowed to just a 0.1% rise.

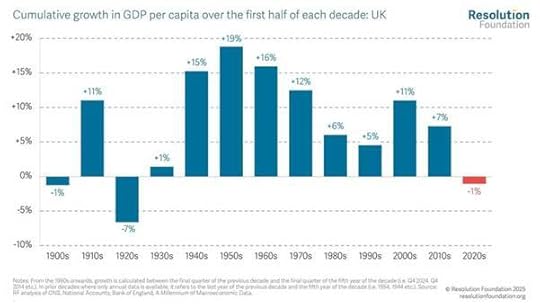

Real GDP per person growth in the UK in the first half of this decade is set to be the weakest of any comparable period in a century.

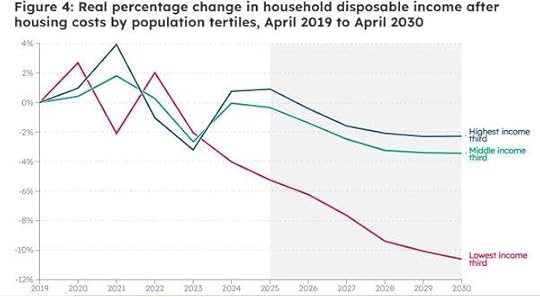

Despite this, Reeves sought to claim that the OBR has confirmed that real household disposable income will grow “at almost twice the rate” that had been anticipated in the autumn. She said households will be “on average” £500 better off “under this government”. This claim is flatly denied by the Joseph Rowntree Trust in a new study that reckoned ALL British families will be worse off by the end of this decade, with those on the lowest incomes hit twice as hard as middle and high-earners, a new forecast suggests. That would mean the average real disposable income in the UK would have fallen for ten years.

“We estimate that average household disposable incomes after housing costs (hereafter ‘disposable incomes’) will remain £400 a year below 2020 levels in April. By April 2030 households will be a further £1,400 worse off on average than they are today, a 3 percentage point fall.” The JRF forecasts that real gross earnings will fall by £700 a year between 2025 and 2030. This is due to firms passing on most of the costs of the recent increase to employer National Insurance Contributions (NICs) through lower nominal wages, smaller staff counts and higher consumer prices. Fiscal drag also continues to squeeze post-tax income through to 2028, as income tax thresholds have been frozen until 2028.

Middle- and higher-income households would have a fall in real disposable incomes of around 3% between 2025 and 2030, with real net earnings falling at the same time as housing costs rise. For the lowest income families, incomes are falling twice as fast as for the middle and the top, with a 6% fall in real disposable incomes between 2025 and 2030. These lowest income families will be £900 worse off by 2030, compared to today.

This Labour government has followed the previous Conservative government in imposing fiscal austerity – but this time on steroids. Reeves clams that there is a ‘fiscal hole’ between government revenues and spending now equivalent to £10bn a year, which must be filled. But this a hole that she has dug herself. The government promised no income tax changes, including no rise in corporate profits tax. It opposed significant borrowing to bridge any gap. It has ignored calls for a wealth tax on the super-rich. Instead, it has introduced a range of welfare cuts that affect the poorest in Britain, although polling shows two-thirds of the British public (64%) support a wealth tax on those who have over £10m. A wealth tax of 2% a year on those owning more than £10m would raise £24bn a year, easily covering the so-called ‘fiscal hole’.

Instead, the cuts pour in. First, there was the cap on child benefit to two children per family. Then there was the abolition of winter fuel payments made to the elderly. And more recently, the government announced swingeing reductions in benefits to the disabled and those unable to work. The UK’s Resolution Foundation think-tank estimated that this would leave as many as 1.2mn people worse off by £4,300 a year by 2029, because they would not receive “daily living” payments. Tougher eligibility for personal independence payments (Pips) and incapacity benefits will mean some people now in line to receive £15,000 a year, excluding housing support, will instead receive just £5,400 — a drop of 64 per cent. Ayla Ozmen, director of policy and campaigns at welfare charity Z2K, said three quarters of people on universal credit and disability support already struggled to afford the essentials. “Evidence from our advice services shows that those who will lose out include people with psychosis and double amputees,” she added.

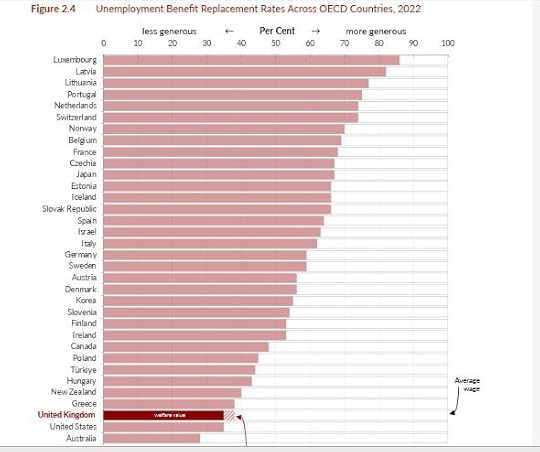

This is a horrendous hit to the living standards of the poorest. Right now, three million UK households are £3,000 a year worse off than the poorest households in Germany and £1,500 a year worse off than the lowest earners in France. They are also poorer than people in the poorest parts of Slovenia (where average disposable income is almost £900 a year higher), Malta (£1,000 higher) and Ireland (£2,300 higher). So says a new report on British living standards by the NIESR.

Districts in Birmingham were ranked as the poorest in the UK, according to the study, and below the poorest areas of Finland, France, Malta and Slovenia, it found. The UK now has some of the least generous welfare across countries in the OECD. Welfare payments covered the cost of essentials in only two of the past 14 years – both of them during the pandemic, after the £20 a week increase to universal credit. And now Reeves plans a further cut in universal credit. The ‘health’ element in UC will be cut by 50% and then frozen for new claimants. Reeves also plans to cut central government spending by up to 15% over this parliament, thus halving any real rise each year, with big cuts, yet again, for local councils, prisons and the courts.

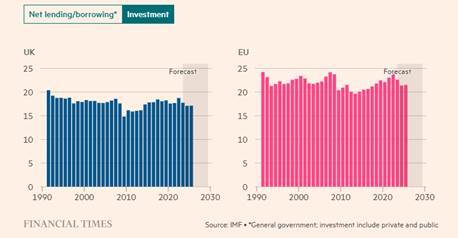

But there is more money to be spent in some areas, namely defence. The Starmer government with its arms race strategy in full blast has already announced a hike in defence spending from 2.3 per cent of GDP to 2.5 per cent by 2027 and onto 3% as soon as possible. The first hike has been paid for by cutting foreign ‘aid’ to the poorest countries in the world. And the much-heralded National Wealth Fund for investment will now be allowed to make investments in defence ie to arms manufacturers. So less on productive investment and more on unproductive destructive investment. The reason the British economy is in such a mess is that productive investment growth is low, lower than in comparable economies.

The government says it is going to change that and boost investment and economic growth. But its plan to do so rests entirely on encouraging the capitalist sector to increase spending. Apparently this will be done by ‘de-regulating’ the economy – in effect ending environmental and climate controls, ending restrictions on monopolies and a free hand for the financial sector to do what it wants. It was ‘light-touch’ regulation of the City of London that was the mantra of the last Labour government under Blair and Brown. Now it is doubled down on by Starmer and Reeves. According to Reeves, the City of London is the ‘crown jewel of the British economy and the main generator of growth’, not a centre of fictitious capital waiting for another accident to happen, as in 2008-9.

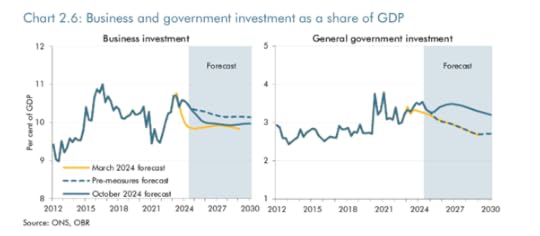

Through the mist of the government claims, the OBR finds that business investment to GDP, the lowest in the G7 at about 10%, will be little changed by the end of this parliament and government investment will be lower at the end of the Labour government’s term than at the start.

Labour’s policy to boost growth is to get rid of ‘planning’. Take housing. Reeves and deputy prime minister Rayner claim that de-regulating local planning regulations will take house building to a 40-year high (which is not actually saying much). But their measures really open the door for private developers like BlackRock and landlords to build, sell and rent homes at unaffordable levels. So-called affordable homes are not that at all – at 80% of the market rate, where house prices have risen to nine times average wages in England and Wales, Hardly any ‘social housing’ for those in need is promised.

Reeves says she has to make these cuts in government spending to ‘fill’ her fictional fiscal hole and to control fast-rising government debt. It’s true that government debt to GDP is rising faster in the UK than in the rest of the G7 or Europe. But that is because economic growth is so weak and interest costs on debt are so high as a result of inflation. The UK now spends more than £100bn a year on debt interest – a postwar high. This is money straight into the hands of the banks and financial institutions, paid for by welfare cuts. So the Labour government has decided to keep the financial sector happy with fiscal austerity and hope that economic growth will emerge from deregulation.

There are to be no taxes on the rich and the corporate sector. There is to be no public takeover of the productive sectors of the economy; nor the financial sector; nor the big investment funds. There is to be no public ownership of the corrupt energy and water utilities. The scandal of these privatized utilities is there for all to see, where shareholders have got billions in dividends, while debt and utility prices rise. The total collapse in the water infrastructure has reached the point where the UK’s water supply, rivers and beaches are no longer safe to drink or touch. Meanwhile, Britain’s roads are falling apart with unfilled potholes to the tune of £17bn to fix.

So yet more misery for most British households – spring has not come, the winter will continue.

March 21, 2025

From welfare to warfare: military Keynesianism

Warmongering has reached fever pitch in Europe. It all started with the US under Trump deciding that paying for the military ‘protection’ of European capitals from potential enemies was not worth it. Trump wants to stop the US paying for the bulk of the financing of NATO and providing its military might and he wants to end the Ukraine-Russia conflict so he can concentrate US imperialist strategy on the ‘Western hemisphere’ and the Pacific, with the aim of ‘containing’ and weakening China’s economic rise.

Trump’s strategy has panicked the European ruling elites. They are suddenly concerned that Ukraine will lose to the Russian forces and before long Putin will be at the borders of Germany or as UK premier Keir Starmer and a former head of MI5 both claim, “in British streets”.

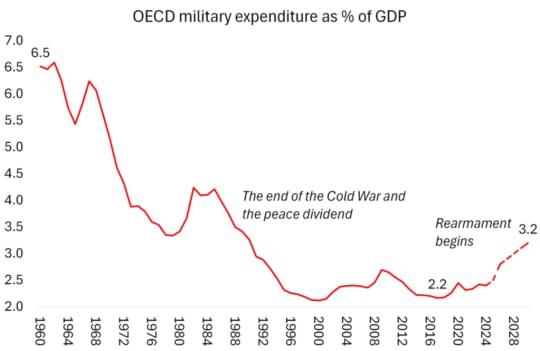

Whatever the validity of this supposed danger, the opportunity has been created for Europe’s military and secret services to ‘up the ante’ and call for an end to the so-called ‘peace dividend’ that began after the fall of the dreaded Soviet Union and now begin the process of rearmament. The EU Foreign Policy Chief Kaja Kallas spelt out the EU’s foreign policy as she saw it: “If together we are not able to put enough pressure on Moscow, then how can we claim that we can defeat China?”

Several arguments are offered for rearming European capitalism. Bronwen Maddox, director of Chatham House, the international relations ‘think-tank’, which mainly presents the views of the British military state, kicked it off with the claim that “spending on ‘defence’ “is the greatest public benefit of all” because it is necessary for the survival of ‘democracy’ against authoritarian forces. But there is a price to be paid for defending democracy: “the UK may have to borrow more to pay for the defence spending it so urgently needs. In the next year and beyond, politicians will have to brace themselves to reclaim money through cuts to sickness benefits, pensions and healthcare.” She went on: “If it took decades to build up this spending, it may take decades to reverse it,” so Britain needs to get on with it. “Starmer will soon have to name a date by which the UK will meet 2.5 per cent of GDP on military spending — and there is already a chorus arguing that this figure needs to be higher. In the end, politicians will have to persuade voters to surrender some of their benefits to pay for defence.”

Martin Wolf, the liberal Keynesian economic guru of the Financial Times, launched in: “spending on defence will need to rise substantially. Note that it was 5 per cent of UK GDP, or more, in the 1970s and 1980s. It may not need to be at those levels in the long term: modern Russia is not the Soviet Union. Yet it may need to be as high as that during the build-up, especially if the US does withdraw.”

How to pay for this? “If defence spending is to be permanently higher, taxes must rise, unless the government can find sufficient spending cuts, which is doubtful.” But don’t worry, spending on tanks, troops and missiles is actually beneficial to an economy, says Wolf. “The UK can also realistically expect economic returns on its defence investments. Historically, wars have been the mother of innovation.” He then cites the wonderful examples of the gains that Israel and Ukraine have made from their wars: “Israel’s “start up economy” began in its army. The Ukrainians now have revolutionised drone warfare.” He does not mention the human cost involved in innovation by war. Wolf moves on: “The crucial point, however, is that the need to spend significantly more on defence should be viewed as more than just a necessity and also more than just a cost, though both are true. If done in the right way, it is also an economic opportunity.” So war is the way out of economic stagnation.

Wolf shouts that Britain needs to get on with it: “If the US is no longer a proponent and defender of liberal democracy, the only force potentially strong enough to fill the gap is Europe. If Europeans are to succeed with this heavy task, they must begin by securing their home. Their ability to do so will depend in turn on resources, time, will and cohesion ….. Undoubtedly, Europe can substantially increase its spending on defence.” Wolf argued that we must defend the vaunted “European values” of personal freedom and liberal democracy. “To do so will be economically costly and even dangerous but necessary… because “Europe has ‘fifth columns’ almost everywhere.” He concluded that “If Europe does not mobilise quickly in its own defence, liberal democracy might founder altogether. Today feels a bit like the 1930s. This time, alas, the US looks to be on the wrong side.”

‘Progressive conservative’, FT columnist Janan Ganesh spelt it out baldly: “Europe must trim its welfare state to build a warfare state. There is no way of defending the continent without cuts to social spending.” He made it clear that the gains working people made after the end of WW2 but were gradually whittled away in the last 40 years must now be totally dispensed with. “The mission now is to defend Europe’s lives. How, if not through a smaller welfare state, is a better-armed continent to be funded?” The golden age of the post-war welfare state is not possible anymore. “Anyone under 80 who has spent their life in Europe can be excused for regarding a giant (sic – MR) welfare state as the natural way of things. In truth, it was the product of strange historical circumstances, which prevailed in the second half of the 20th century and no longer do.”

Yes, correct, the gains for working people in the golden age were the exception from the norm in capitalism (‘strange historical circumstances’). But now “pension and healthcare liabilities were going to be hard enough for the working population to meet even before the current defence shock…..Governments will have to be stingier with the old. Or, if that is unthinkable given their voting weight, the blade will have to fall on more productive areas of spending … Either way, the welfare state as we have known it must retreat somewhat: not enough that we will no longer call it by that name, but enough to hurt.” Ganesh, the true conservative, sees rearmament as an opportunity for capital to make the necessary reductions in welfare and public services. “Spending cuts are easier to sell on behalf of defence than on behalf of a generalised notion of efficiency…. Still, that isn’t the purpose of defence, and politicians must insist on this point. The purpose is survival.” So so-called ‘liberal capitalism’ needs to survive and that means cutting living standards for the poorest and spending money on going to war. From welfare state to warfare state.

Poland’s Prime minister Donald Tusk took the warmongering up another notch. He said that Poland “must reach for the most modern possibilities, also related to nuclear weapons and modern unconventional weapons”. We can presume that ‘unconventional’ meant chemical weapons? Tusk: “I say this with full responsibility, it is not enough to purchase conventional weapons, the most traditional ones.”

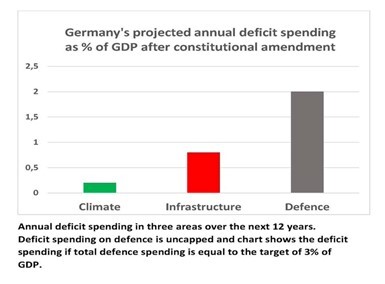

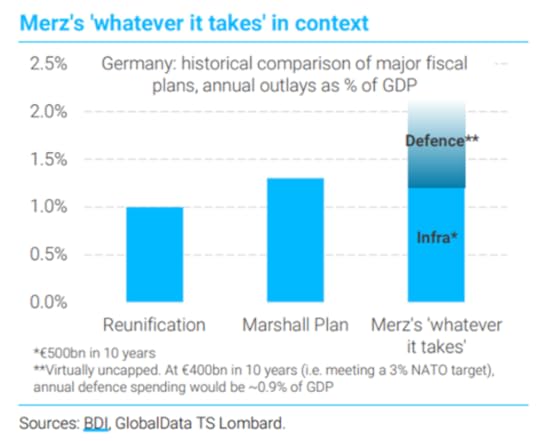

So nearly everywhere in Europe, the call is for increased ‘defence’ spending and rearmament. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has proposed a Rearm Europe Plan which aims to mobilise up to €800 billion to finance a massive ramp-up in defence spending. “We are in an era of re-armament, and Europe is ready to massively boost its defence spending, both to respond to the short-term urgency to act and to support Ukraine, but also to address the long-term need to take on more responsibility for our own European security,” she said. Under an ’emergency escape clause’, the EU Commission will call for increased spending on arms even if it breaks existing fiscal rules. Unused COVID funds (E90bn) and more borrowing through a “new instrument” will follow, to provide €150 billion in loans to member states to finance joint defence investments in pan-European capabilities including air and missile defence, artillery systems, missiles and ammunition, drones and anti-drone systems. Von der Leyen claimed that if EU countries increase their defence spending by 1.5% of GDP on average, €650 billion could be freed up over the coming four years. But there would be no extra funding for investment, infrastructure projects or public services, because Europe must devote its resources for preparing for war.

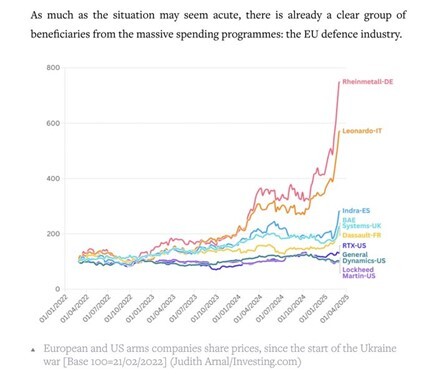

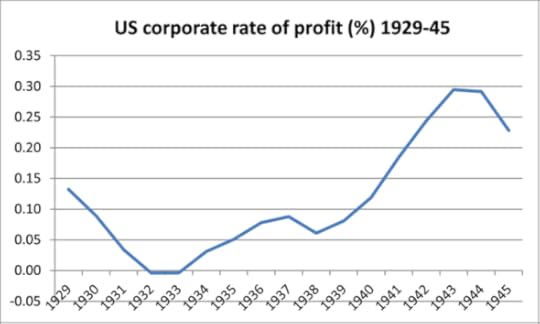

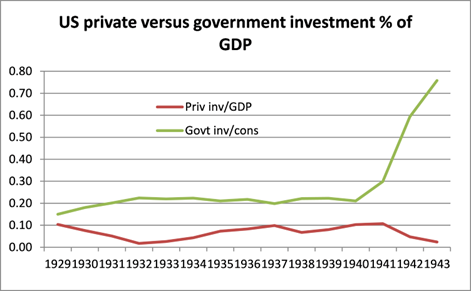

At the same time, as the FT put it, the British government “is making a rapid transition from green to battleship grey by now placing defence at the heart of its approach to technology and manufacturing.” Starmer announced a rise in defence spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2027 and an ambition to reach 3% into the 2030s. Britain’s finance minister Rachel Reeves, who has been steadily cutting spending on child credits, winter payments for the aged and disability benefits, announced that the remit of the Labour government’s new National Wealth Fund would be changed to let it invest in defence. British arms manufacturers are cock a hoop. “Leaving aside the ethics of weapons production, which deters some investors, there is plenty to like about defence as an industrial strategy” said one CEO.