Michael Roberts's Blog, page 3

August 10, 2025

WAPE 2025: geopolitics, economic models and multi-polarity

Last weekend the 18th Congress of the World Association of Political Economy (WAPE) took place in Istanbul, Turkey.. WAPE is a Chinese-run academic economics organisation, linking up with Marxist economists globally. “Even though that might seem like bias, the WAPE forums and journals still provide an important outlet to discuss all the developments in the world capitalist economy from a Marxist perspective. Marxist economists from all over the world are welcome to join WAPE and attend WAPE forums.” (WAPE mission statement).

As you would expect, many of the plenary speeches included economists from China as well as those from ‘the West’ and the ‘Global South’. I was invited to attend but was unable to do so, so I cannot report on the subjects of the various plenary speeches. However, I did make a presentation by recorded video (see my You Tube channel).

There were also a series of paper sessions covering themes such as geopolitical economy; macroeconomic modelling; ecology; AI; imperialism and multi-polarity; and of course, China. I have managed to obtain some of the presentations from their authors and so can make some (rather limited) comments.

Let’s start with geopolitics. The first paper session on this theme was about the 80th anniversary of the United Nations. I’m afraid I cannot comment on the papers in this session as I do not have them. But I can make a general point about the history and efficacy of the UN. It was an institution set up in 1945 along with other agencies designed to set the world order after WW2. The IMF was supposed to support advanced capitalist economies that got into financial trouble, using funds mainly financed by the US; the World Bank was supposed to support and help the poor countries of the world to grow and end their poverty; and the UN was supposed to be the international body to ensure peace and offer ‘neutral’ peace-keeping diplomacy and armed forces if necessary to resolve or control conflicts.

The claim was that these organisations were fair and balanced and constructive. In reality, they were agencies to ensure US-led imperialist control over the world. The IMF provides emergency funds under strict conditionalities; but many countries that have governments working in the interests of US imperialism get extra help with fewer conditions (Argentina, Ukraine) while others are starved of funds (Venezuela) or face distress from IMF debt. Based in New York, the UN was not a body of equals; it has a security council where only the top post-war nations have a vote and a veto on anything that the UN does. This has paralysed its role as peacekeeper. Significantly, as the US has lost some of its dominance politically, the UN it has increasingly been ignored by the great powers – whereas the US would go to the UN to get backing for its war in Korea in the 1950s or even the invasion of Iraq in the 2000s (unsuccessfully), increasingly the US now looks for ‘coalitions of the willing’ to bypass the UN and instead uses and expands NATO for its purposes. The UN has not played a role in resolving conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza, Iran or Afghanistan. It is an irrelevance.

That the UN is an irrelevance is further confirmed by the discussions taking place at WAPE and other conferences of the left. The discussion now is about alternatives to US hegemony and imperialism and the hope that ‘multipolarity’, as expressed in the BRICS formation, could be a new development in defeating US dominance over the last 80 years.

There were a number of papers on this theme. I have only one that I can comment on. Prof. Chandrasekhar Saratchand, University of Delhi presented: Neoliberalism and the Transition From the Washington Consensus to MAGA. In his paper, Prof Saratchand argues that the global order post WW2 as described above gave way to neoliberalism, the aim of which was to extract extra surplus value out of the Global South by ‘metropolitan capital’. The so-called Washington Consensus (WC) was the ideological support for this exploitation of the poor countries. The WC argued that only the US and the ‘free democracies ‘ of the West could bring prosperity through “free markets” and unrestricted capital flows. Any resistance to this Consensus by government adopting protectionism or nationalisation was detrimental to the world.

However, China’s rise increasingly undermined the world order (ie US hegemony). So the US switched from ‘engagement’ with China to ‘containment’. The Washington Consensus was also amended post the Great Recession to no longer advocate globalisation and free trade, but instead to support the ‘democratic bloc’ against the ‘autocratic bloc’. Saratchand argues that the US cannot turn the clock back and stay as global leader, despite the aims of the MAGA supporters under Trump in the US. Indeed, the dollar is threatened by multi-polar blocs in the future.

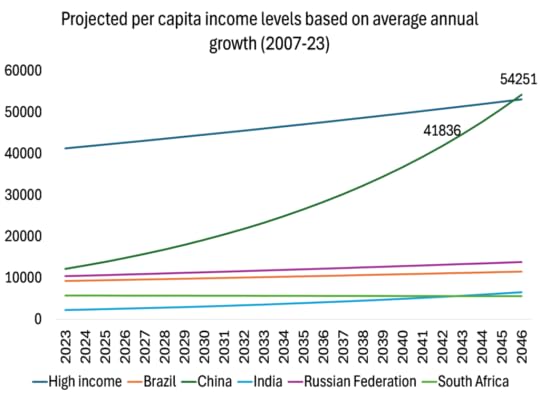

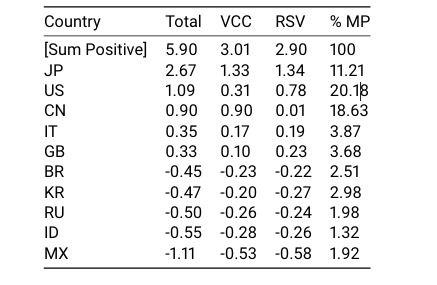

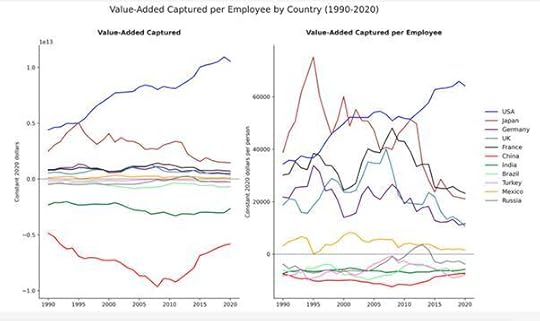

My own paper (as presented by video above) concentrated on the failure of the poor countries of the world to ‘catch up’ with the rich countries after 80 years of the post-war world order. I tried to gauge the gap between the rich and poor countries ie the imperialist core and the dominated periphery. To do this, I measured 1) the average per capita income in each country (taking into account, where we can, the inequality of incomes within countries); 2) the level of labour productivity; and 3) ‘human development’ as defined by the UN. Then I extrapolated the current average growth in these measures to see when the periphery might catch up.

I found that the countries of the Global South (6bn people) are not ‘catching up’ with the Global North (2bn people) and never will in the foreseeable future. The main reasons are that wealth (value) is being persistently transferred from the South to the North AND profitability in the Global South is falling faster than labour productivity growth is rising. However, I did find that China may be the exception because its investment growth is less determined by profitability than in any other major Global South economy. In effect, the Marxist model of uneven and combined development explains best why the periphery is not catching up and will not do so unless the structure of global accumulation and trade is changed – to put it bluntly, unless capitalism/imperialism is replaced by a commonly owned and democratically planned global economy.

Another theme of the conference sessions was macro modelling, in other words working out the cycles of accumulation and growth under capitalism. Costas Passas, a the Greek School of Social Sciences looked at Greek capitalism in his presentation, The Political Economy of Crisis and Recovery in Modern Greece. This was a joint paper with Thanasis Maniatis, both of whom published in our book World in Crisis back in 2018. Passas and Maniatis show that, contrary to recent optimistic mainstream talk, Greece is not really recovering from the terrible years of debt and austerity of the 2010. The central role in any model of capitalism must be profitability; and the current modest recovery in Greece is due to a huge increase in exploitation and an unprecedented devaluation and destruction of capital, the two forces that can raise profitability. But Greek capital still has a very low level of profitability, and so insufficient investment holds back technical change. All the old problems of a weak capitalist economy are exhibited in a renewal of balance of payments problems in Greece. For more on this, see my recent online booklet on Greece.

In another paper, Hiroshi Onishi and Chen Li, of Keio University–Kyoto University and St. Andrew’s University, considered what they called an External Dependency Model of the Capitalist Sector in Labour Supply. They construct an accumulation model based on two assumptions that (1) the level of wages determines the supply of labor; and (2) labor shortages are historically offset by the non-capitalist sector.

This seems to follow the idea of Rosa Luxemburg that capitalist progress depends on the extent of labour supply or demand, not on the relation between the productivity of labour and profitability. Onishi and Chen Li argue that the greater the labor supplied from outside—whether from foreign countries or from non-capitalist sectors such as rural areas—the more intensely capitalists have been able to exploit labor within the capitalist sector. As Western societies become increasingly unable to accept more immigrants due to rising cultural tensions, and as rural labor reserves in Asia become depleted, the exploitation rate will fall, causing a crisis for capitalism. This echoes the theory of the great economic historian J Arthur Lewis.

It is true that immigration and an increased supply of labour is a powerful counteracting factor to falling profitability in capitalist economies, ie it produces a rise in the absolute rate of surplus value. But the presenters seemed to have ignored the most important way capitalism accumulates and expands, ie through mechanisation and thus a rise in relative surplus value. The end of immigration does not necessarily mean a fall in exploitation and therefore a fall in profitability. Unfortunately, Rosa Luxemburg was wrong to think capitalism would collapse if external demand from the periphery fell, and neither is it correct to think capitalism would collapse if the supply of labour globally dried up, even though that would intensify the problem of boosting profitability for capital.

Konstantinos Loizos at the Centre of Planning and Economic Research (KEPE), and Stavros Mavroudeas at Panteon University, Athens, presented a paper Alternative Marxist Theories of Competition: Looking for a New Comprehensive Hypothesis. This argued that any Marxist theory of competition between capitals must involve class struggle as the key element. They refer to Marxist ‘fundamentalists’ (of which I think I am one) who “are right to point out the importance of competition to support innovation in capitalist development.” However, the defining characteristic of capitalism is not competition, but class struggle. The authors argue that class struggle takes two forms: among capitals and between capital and labor and both determine the rate of surplus value and the rate of profit.

Surely, it is the exploitation by capital of labour that determines the size of surplus value and profitability, while competition among capitals determines the distribution of that surplus. For me, the class struggle is between capital and labour. Competition among capitals is not a ‘class struggle’? Many capitals are not many classes. So for me, the charge that “fundamentalists seem to degrade a social relation with political consequences to a technical issue that justifies the tendency for equalization of the rates of profit” is an odd conclusion. If the authors mean that academic Marxists are only ‘interpreting’ the world when ‘the point is to change it’, then there may be truth in that, but to talk of Marx’s law of profitability as a ‘fatalistic law’ that degrades the role of class struggle cannot be right.

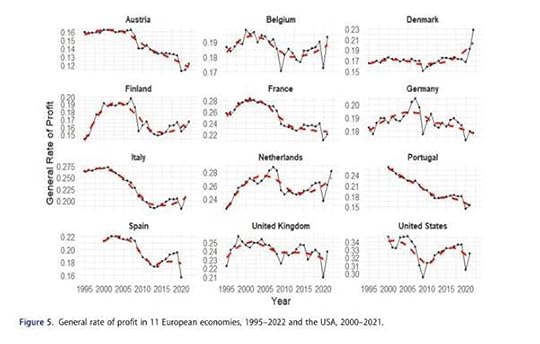

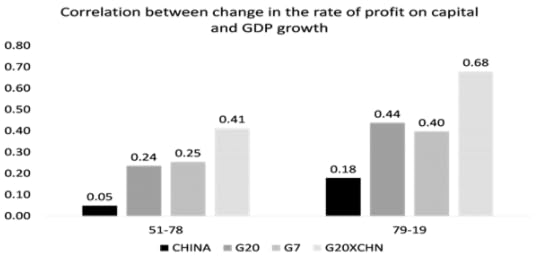

Perhaps the most interesting paper presented at WAPE that I have received is that by Greek Marxist economists Ozan Mutlu & Lefteris Tsoulfidis, on Capital Accumulation, Technological Change, and the Rate of Profit in European and the US Economies. This paper makes a significant contribution to Marx’s law of profitability and the ensuing consequences for the major economies in 2025.

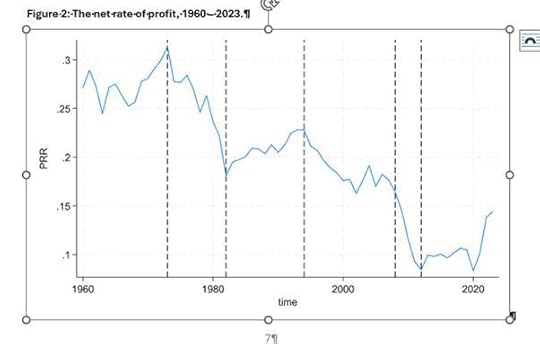

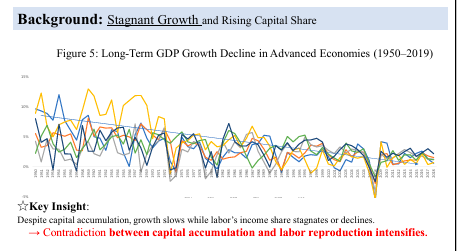

In the paper, the authors break up the economies of Europe and the US into productive and unproductive labour sectors and generate rates of profit accordingly. The general rate of profit is for total economy and the net rate of profit is for productive sectors only. They confirm a long run downward trend in the profitability of capital, driven by two factors: a rising organic composition of capital and a rising share of surplus value going into unproductive activities. This leads to a fall in investment over time to “what can be termed “Marx’s moment” or the tipping point of “absolute overaccumulation of capital” as in 2008.

However, a recent development has been a reversal of a rising share of surplus value in the unproductive sectors, which “appears to have contributed to stabilizing the profit rate” since 2008. The authors speculate this reversal could be due to “new technologies (AI? – MR) increasingly being applied to non-production activities, where employment has sharply declined. This is evident in sectors such as finance, real estate and wholesale and retail trade. These trends seem likely to solidify soon and will probably shape the emerging new sixth-long cycle.” The authors refer here to their view that capitalism is in its downward phase of a fifth long cycle and a new sixth cycle may soon start, driven by rising profitability. I am not so sure. https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2025/07/27/ai-bubbling-up/

A final point. WAPE contributors are keen to discuss and analyse the possible decline of US hegemony and the rise of a ‘multipolar’ world, personified mainly in the BRICS group. It seems many on the left look to the BRICS to provide an alternative anti-imperialist force that can resist US imperialism in support of working people globally.

I think this is a dangerous illusion. Can we really expect that Putin’s Russia, Xi’s China, Modi’s India, Ayotolla’s Iran, El-Sisi’s Egypt, Subianto’s Indonesia or MbS in Saudi Arabia will lead an internationalist movement of workers to overthrow imperialism? These governments do not work for the international interests of working people, but for the national interests of their respective elites. The ‘class struggle’ globally is between the workers of all these countries and their ruling elites, not between elites of imperialism and the elites of the ‘resistant’ countries. For me, imperialism will only be defeated by movements of the working class in the rich countries, but also in the BRICS.

Apologies to anybody with papers not reported on, or for any misunderstanding of the arguments of those I did consider.

August 4, 2025

Tariffs and the US economy

Last week, the mega tech companies – the so-called Magnificent Seven – presented their latest earnings results. They appeared to be ‘blockbuster’. They painted a picture of a booming economy, supporting President Trump’s assertion that America “is the hottest country anywhere in the world”. (He was not referring to global warming). At the same time, Trump announced his latest round of tariff measures on goods exports from other countries into the US. The US stock market continued to stay near a record high.

The financial media lauded the tech results and even went along with the Trump administration’s claims that all the fears about the hit to US economic growth and inflation from Trump’s tariff measures had been proved wrong.

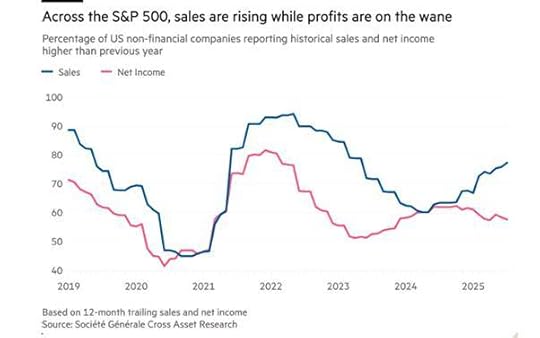

But the more you look at the data below the stock market hype and Trump’s claims, the reality is much less rosy. Below the surface, large parts of corporate America are grappling with slowing profits and the uncertainty generated by Trump’s aggressive trade war. With almost two-thirds of S&P 500 companies having reported second-quarter results, earnings for consumer staples and materials companies are down 0.1 per cent and 5 per cent year on year, according to FactSet data. Indeed, 52 per cent of those S&P 500 companies to have posted results, have reported declining profit margins, according to Société Générale.

The 10 biggest stocks on the S&P 500 account for one-third of overall profits across the index, with tech and financials reporting year-on-year quarterly earnings growth of 41 per cent and 12.8 per cent, respectively.

And when we delve into the earnings results of the Magnificent Seven, we find, contrary to the views of the financial media, that their earnings rises are not due to revenues and profits accrued from the huge investments in AI made by these companies, but from existing services created from the previous tech boom in the internet and social media. Meta’s (Facebook) shares jumped more than 11 per cent on their results adding more than $150bn to its market value. But the rise in earnings came from increased advertising revenues in existing services, not AI.

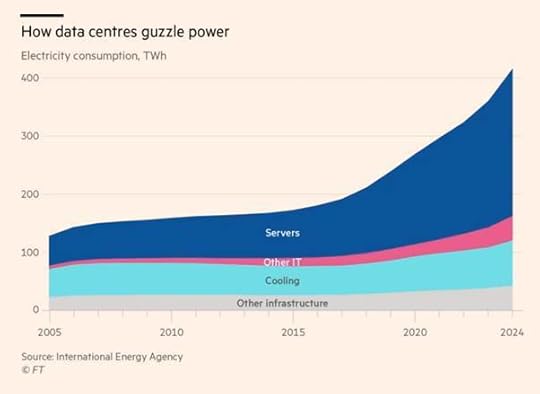

Meta’s Zuckerberg proclaimed that he is investing ever more in AI data centers and energy sources. “We are making all these investments because we have conviction that superintelligence is going to improve every aspect of what we do from a business perspective,” Zuckerberg said on a call with investors. However, Meta’s finance officer Susan Li said Meta was not anticipating “meaningful” revenue from its generative AI push this year or in 2026. And the company cautioned that the costs of building the infrastructure needed to underpin its AI ambitions were growing. Meta raised the lower end of its 2025 capital expenditures forecast to between $66bn and $72bn. It said that it expected its 2026 year-over-year expense growth to be higher than its 2025 growth rate, citing higher infrastructure costs and growth in employee compensation due to its AI efforts.

Over at Microsoft, quarterly profits soared from record revenues in its cloud computing division. But it too is looking to make future money from its massive investment in artificial intelligence. Finance officer Amy Hood said Microsoft spending on data centres would rise to $120bn in 2026 up from $88.2bn in 2025 and almost quadruple the $32bn in 2023. “We are going through a generational tech shift with AI . . . We lead the AI infrastructure wave and took share every quarter this year, we continue to scale our own data centre capacity faster than any other competitor.” But little or no revenue comes from AI so far. Copilot AI apps now had 100mn monthly users, Google’s Gemini with 450mn users and market leader ChatGPT, with more than 600mn. But only 3% actually pay for AI.

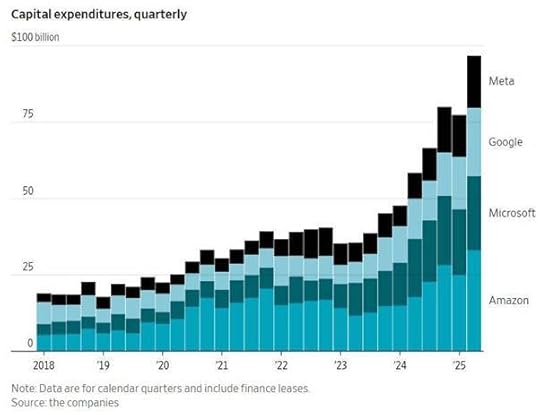

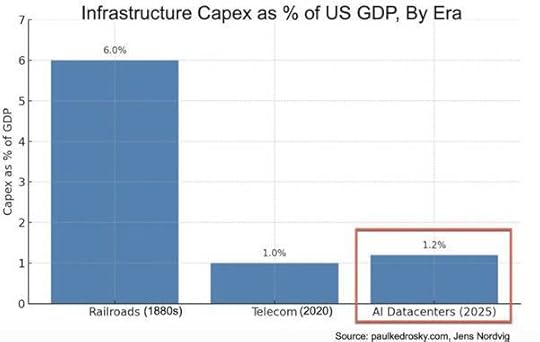

Already Microsoft and Meta capital expenditure is more than a third of their total sales. Indeed, capex spending for AI contributed more to growth in the US economy in the past two quarters than all of consumer spending.

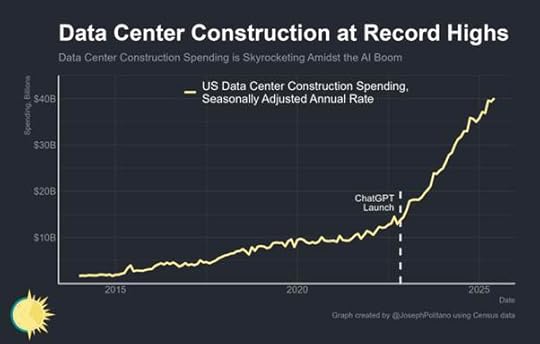

And there is no end yet to the AI investment boom. US data center construction hit another record high in June, exceeding $40bn annualized for the first time. That’s up 28% from this time last year and up 190% since the launch of ChatGPT nearly three years ago.

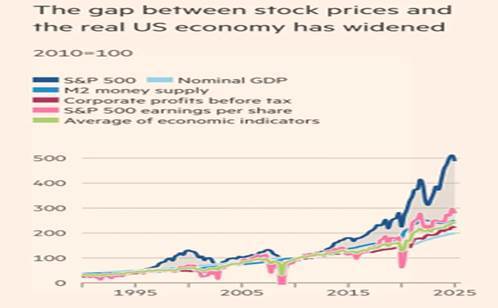

But this boom in the stock market, driven by AI hype, is increasingly out of line with the rest of the US economy.

Take the latest US real GDP figures. After the data showed that the Eurozone grew only 0.1% in Q2 2025, the US data showed a rise in real GDP of 0.7%, which translated into an annualised rate of 3.0%, more than forecast. Trump hailed the result. But the headline growth rate was mainly due to a sharp fall in imports of goods into the US (-30%) as the tariff rises began to bite. The fall in imports meant that net trade (that’s exports minus imports) rose sharply, adding to GDP. Excluding trade and the impact of the tariffs, real final sales to private domestic purchasers, the sum of domestic consumer spending and gross private fixed investment, slowed to a rise of just 1.2% compared to 1.9% in Q1.

Indeed, investment growth dropped back in Q2, up only 0.4% vs 7.6% in Q1. Investment in equipment grew only 4.8% compared to the huge 23.7% rise in Q1, while investment in new structures (factories, data centres and offices) fell 10.3% in Q2, having also fallen 2.4% in Q1. Looking through all these volatile changes, the overall picture is that the US economy rose 2.0% in real terms in Q2 2025 over the same period in 2024, at the same rate as in Q1. The US economy is still doing better than the Eurozone and Japan, but at less than half the rate of China.

Source: BEA

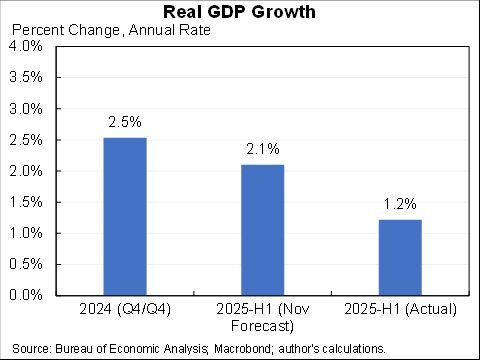

Mainstream economist Jason Furman points out that US real GDP growth for the first half of 2025 averaged just a 1.2% annual rate, well below the pace in 2024. So the current 2% a year rate as above is likely to slip further.

Source: Jason Furman

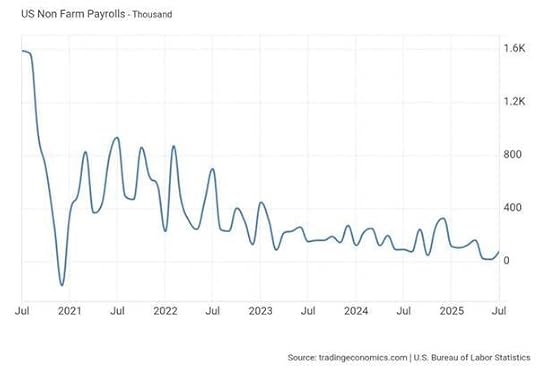

And then there is employment. The latest release on jobs growth in the US was ugly. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics said there was only a tiny 73k increase in July and previous May and June data were revised down sharply, while the unemployment rate rose. Indeed, only 106,000 jobs have been added from May to July, down sharply from the 380,000 added in the previous three months.

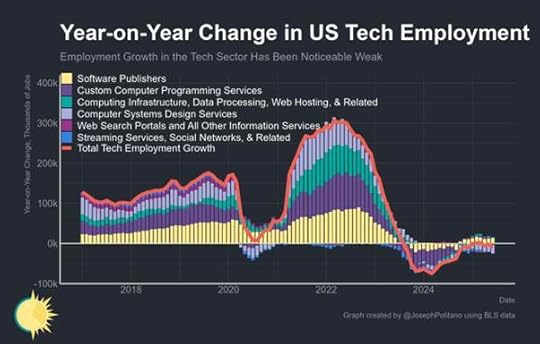

This is now the worst job market in the US since the end of pandemic slump. Layoffs are at their highest level with nearly 750k job cuts in H1 2025. Even the high flying tech sector has seen a loss of jobs. Across all subsectors, jobs growth remains well below the peak tech era of 2022 or even the pre-COVID era.

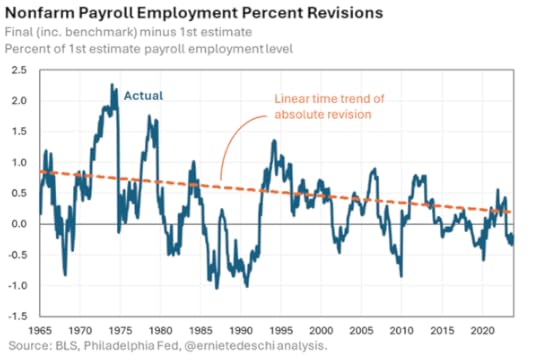

Blame the messenger. On the news of July jobs figures, Trump claimed the US economy had never been stronger; the figures had been rigged and so he sacked the longstanding head of Bureau of Labor stats. It’s true that the jobs statistics are volatile and the Bureau finds it difficult to reconcile different measures of employment growth, but the irony in Trump’s move is that the Bureau’s estimates of payroll employment have got more, not less, accurate over time.

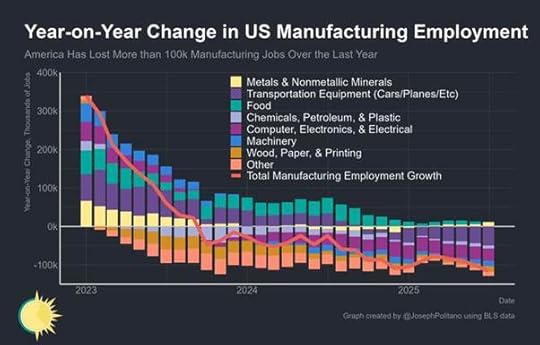

The reality is that the US economy has been slowing down for some time and with it, employment growth. Indeed, America has lost 116k manufacturing jobs over the last year—that’s the fastest pace of job loss since the early COVID era and worse than any period from 2011-2019. Big drops in the transportation (-49k) & electronics (-32k) industries have driven most of the decline.

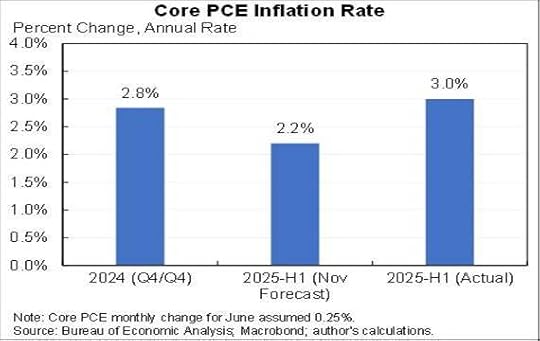

And then there is inflation. Far from inflation rates heading down as the economy slows, the official rates are staying stubbornly closer to 3% a year, instead of the target rate set by the US Federal Reserve of 2% a year.

Source: Furman

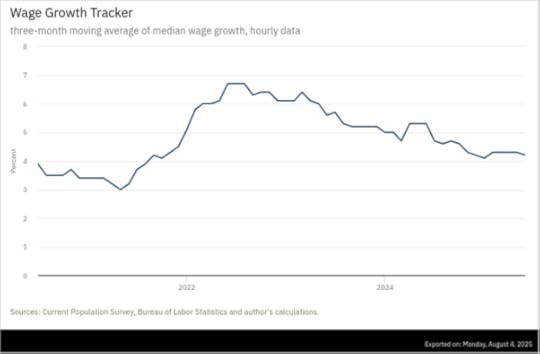

You might say, what difference does one percentage point make? But remember American consumers have suffered an average 20% rise in prices since the end of the pandemic slump and with average wage growth now slowing towards 3% a year, any real gains in living standards have disappeared.

Source: Atlanta Fed

Average real weekly earnings for full-time employees are now at the same level as just before pandemic, some five years ago.

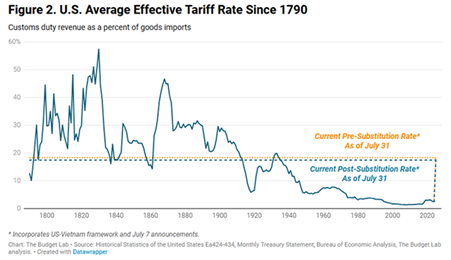

All this is well before Trump’s tariffs begin to hit the US economy and consumers. As Fed chair Jay Powell put it: “American businesses have been absorbing Trump’s tariffs so far, but eventually the burden will be shifted on to American consumers.” Trump’s latest tariff measures are a mess with no rhyme or reason. He has raised high tariffs on some countries and in some sectors, but not in others. Since Trump took office, the average effective US tariff rate on all goods from overseas has now soared to its highest level in almost a century: 18.2%, according to the Budget Lab at Yale.

Source: The Budget Lab

Trump says increased import tariffs are bringing in billions in extra revenue for a government that is running a huge budget deficit of about 6% of GDP a year. But the extra billions are tiny compared to the deficit and revenue is being lost from Trump’s cuts to corporate profits taxes and above all from the slowdown in the economy. Meanwhile, the US trade deficit is running about 50 per cent above last year and will end up higher for 2025 as a whole, while GDP growth will be weaker.

Tariffs are typically paid by the importer of the product affected. If the tariff on that product suddenly goes from 0% to 15%, the importer will try to pass it on. So far, many have resisted and tried to absorb the extra cost. Some 50% say they are “absorbing cost increases internally.” But eventually, the tariff rises will feed into consumer prices. The Budget Lab at Yale estimates the short-term impact of Trump’s tariffs will be a 1.8% rise in US prices, equivalent to an average income loss of $2,400 per US household.

But the tariffs will also lead to less investment at home as US manufacturers find the costs of importing components from abroad rising significantly, and domestic substitutes (if they exist) will be pricier. Profit margins will be squeezed even if prices are raised to compensate. That will add to downward pressure on US economic growth. The Yale Budget Lab reckons if they stay as they are now, Trump’s tariffs will reduce GDP growth by 0.6% pts through the rest of this year and next year (that means the current growth rate of under 2% could fall below 1% by end 2026). As I have argued before, the US economy would then enter a period of stagflation, where economic growth stutters to a near halt, while unemployment rises along with inflation.

This puts the US Federal Reserve in a serious dilemma. Last week, the Fed’s monetary policy committee decided not to lower its policy interest rate. The Fed’s policy rate, which sets the floor for all borrowing rates in the US and often globally, was held at 4.25% for the fifth straight meeting. This was despite threatening noises from President Donald Trump who wants a huge cut and says he will remove Fed Chair Powell if he does not get it. But if the Fed cuts rates, that will weaken its ability (such as it is) to control inflation and meet the 2% target. On the other hand, if it continues to hold rates up, then it will add to the borrowing costs of companies and households and so force further cuts in investment and employment.

Now I have argued in the past that Fed monetary policy has little effect on the economy: what matters are profits and their effect on investment. But the Fed’s dilemma between rising inflation and rising unemployment sums up the growing stagflationary environment in the US. And the impact of Trump’s trade tariffs has yet to be fully felt. So the Fed faces the prospect of a stagflationary economy.

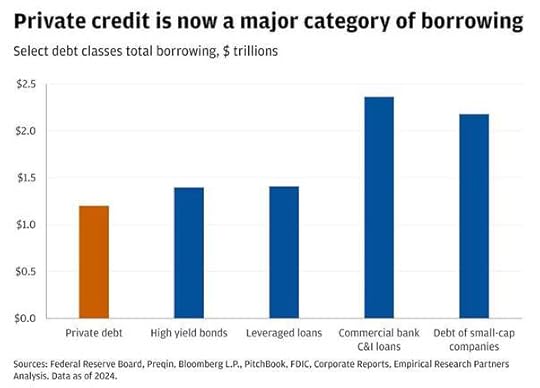

Meanwhile the AI capacity spending boom accelerates. The Magnificent Seven of mega tech companies are paying for this by running down their cash reserves and borrowing more. Of the planned investment in AI data centers of near $3trn by 2028, half will have come from using up cash flows and increasingly nearly another third from what is called ‘private credit’.

The tech companies are borrowing less in the traditional form of corporate bond issuance or bank loans and instead opting for getting credit from private credit companies that raise money from hedge funds, pension funds and other institutions and then lend it on. These credit vehicles are not regulated like the bond markets or the banks. So if things go wrong in the AI bubble, there could a rapid reaction in credit markets.

The US has a record high stock market, unlimited spending on AI capacity by the tech giants, along with sharply increased borrowing to pay for it; but no sign yet of any significant revenues or profits from AI – and alongside that: a slowing rest of the economy, a widening trade deficit in goods and increasing unemployment and prices. All this as we go into the second half of 2025.

July 27, 2025

AI: bubbling up

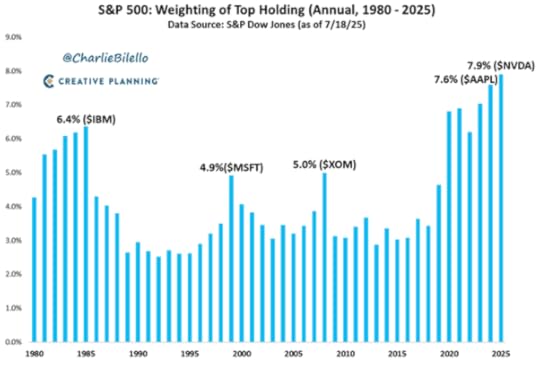

The Magnificent 7 stocks — NVIDIA, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), Apple, Meta, Tesla and Amazon — now make up around 35% of the value of the US stock market, and NVIDIA’s market value makes up about 19% of the Magnificent 7. The S&P 500 has never been more concentrated in a single stock than it is today, with Nvidia representing close to 8% of the index.

This is a hugely top heavy stock market, now at record levels, driven by just seven stocks and in particular, Nvidia, the company that is making all the processors needed by AI companies to develop their models. If Nvidia’s revenue growth should weaken, that will put huge downward pressure on this highly overvalued stock market. As Torsten Slok, chief economist at one of the largest investment institutions, put it: “The difference between the IT bubble in the 1990s and the AI bubble today is that the top 10 companies in the S&P 500 today are more overvalued than they were in the 1990s.”

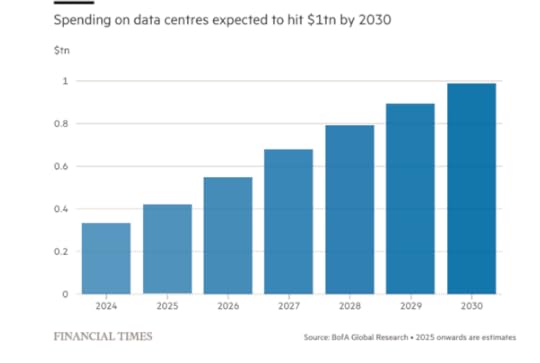

So is the great AI sector a huge bubble, funded by fictitious capital that will not be realised by revenues and, more important, profits for the AI leaders? By the end of this year, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Tesla will have spent over $560 billion in capital expenditures on AI in the last two years, but they have only accrued revenues of about $35 billion. Amazon plans to spend $105 billion in capital expenditures this year but will get revenues of just $5bn. And revenues are not profit, as revenues are measured before the costs of delivering AI services. Investment in AI is now at $332 billion of capital expenditures in 2025 for just $28.7 billion of revenue. Investment in the huge data centers necessary to train and source AI models is planned to reach $1trn by the end of the decade.

But if any of the Magnificent Seven start getting cold feet on what they are spending relative to revenues and profit and so reduce their purchases of chips, Nvidia’s stock price could head downwards fast, taking others with it.

Are the expected returns of revenue on this massive capital investment likely to materialise? Goldman Sachs’ head of equity research, Jim Covello, questioned whether the companies planning to pour $1tn into building generative AI would ever see a return on the money. A partner at venture capital firm Sequoia, meanwhile, estimated that tech companies needed to generate $600bn in extra revenue to justify their extra capital spending in 2024 alone — around six times more than they were likely to produce.

Take the well known ChatGPT. It has, allegedly, 500 million weekly active users — but by the last count, only 15.5 million paying subscribers, just a 3% conversion rate. While increasing numbers of people now use AI chatbots, only a tiny number are paying for the AI service they use, producing annual revenue of about $12bn, according to a survey of 5,000 American adults by Menlo Ventures.

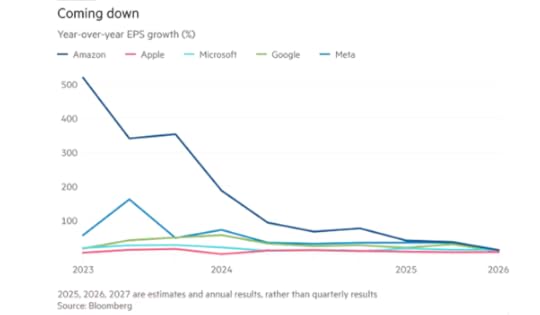

When it comes to profits from AI, the situation is even worse. Big Tech’s annual earnings growth results have been flat or slowing for the past few quarters and are expected to slow further in 2025 and 2026.

So huge investment of money and resources, astronomic payments to AI trainers, and massive data centers being constructed – with the AI hype driving the stock market to ever new heights – but so far, with no significant revenues raised and virtually no profits. This is a repeat of the dot.com bubble on steroids.

However, a bubble there may be, but that does not mean that eventually a new ‘disrupting’ technology will not emerge that will radically change the productivity frontier for the major economies and thus deliver a new period of growth. The dot.com bubble burst in 2000 with a massive drop in the stock market, but the internet went on to spread into all sectors of business and into all households – and the Magnificent Seven emerged.

Take another example from the 19th century. During the 1840s, there was Railway Mania, as huge numbers of companies raised funds to invest in constructing rail lines across Britain. Railway shares rocketed, with stock prices doubling in 18 months from early 1843. But after the bubble came the burst in 1845, with many companies going bust and stock prices falling by half. This triggered a widespread financial crisis and a slump in production. Nevertheless, the railways were built, transport costs dropped sharply and consumer demand for travel expanded mightily. Britain entered an economic boom in the 1850s.

Will the AI bubble follow the same path, producing a financial collapse and crisis, but eventually provide the basis for new growth in productivity? In previous posts on AI, I have recounted the scepticism about the productivity benefits of AI offered by such experts as Nobel prize winner, Daren Acemoglu and others. Also in a recent in-depth report by the OECD on productivity growth in the major economies, cold water was poured onto impact of the internet in raising productivity growth in the last 25 years.

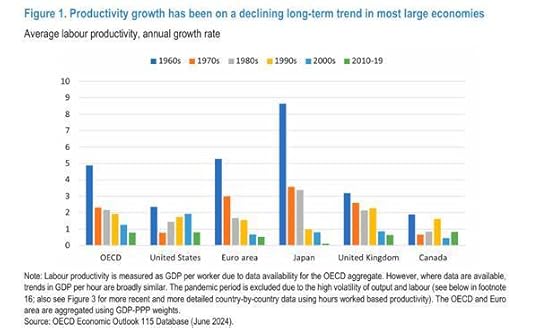

As the OECD report put it: “Over the past half-century we have filled offices and pockets with ever-faster computers, yet labour-productivity growth in advanced economies has slowed from roughly 2 per cent a year in the 1990s to about 0.8 per cent in the past decade. Even China’s once-soaring output per worker has stalled”. Research productivity has sagged. The average scientist now produces fewer breakthrough ideas per dollar than their 1960s counterpart.

Labour productivity growth has been on a declining trend since the 1970s across the OECD and weakened further since the turn of the century. In the US, productivity picked up from the mid 1990s to the mid-2000s on the back of rising efficiency in the production of ICT equipment and the diffusion of internet-related innovations that were adopted in ICT-using sectors, notably retail. “However, this rebound was relatively short-lived and productivity growth has since then been lacklustre.”

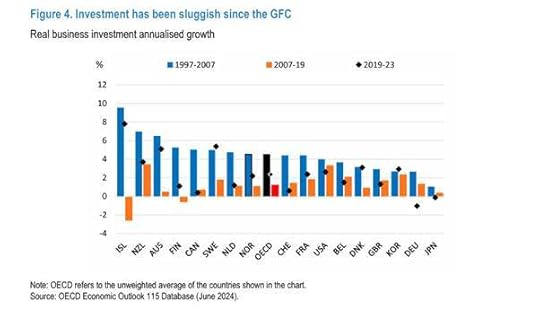

The key factor in raising productivity of labour is investment in new labour-saving technology. But business investment has slowed markedly in all countries. And the OECD makes clear why. The “investment slowdown despite readily available and cheap credit for firms with access to capital markets is in line with historical patterns showing that uncertainty and expected profits tend to play a greater role than financial conditions in investment decisions.” In other words, the profitability of capital declined, reducing the incentive to invest in new technologies.

And so-called ‘intangibles’, like software investment, did not compensate for the decline in investment in plant, equipment etc. “Notwithstanding the rise of intangibles, total investment since the GFC has been weak overall, which worsened the labour productivity slowdown directly.”

Will AI be different? Can it deliver higher productiivity through companies replacing millions of workers across the econmy with AI tools? The problem here is that economic miracles usually stem from discovery, not repeating tasks at greater speed. So far, AI primarily boosts efficiency rather than creativity. A survey of over 7,000 knowledge workers found heavy users of generative AI reduced weekly email tasks by 3.6 hours (31 per cent), while collaborative work remained unchanged. But once everyone delegated email responses to ChatGPT, inbox volume expanded, nullifying initial efficiency gains. “America’s brief productivity resurgence of the 1990s teaches us that gains from new tools, be they spreadsheets or AI agents, fade unless accompanied by breakthrough innovations.” (OECD).

Large language models gravitate towards the statistical consensus. A model trained before Galileo would have parroted a geocentric universe; fed 19th-century texts, it would have proved human flight impossible before the Wright brothers succeeded. A recent Nature review found that, while LLMs lightened routine scientific chores, the decisive leaps of insight still belonged to humans. Human cognition is better conceptualized as a form of theory-based causal reasoning rather than AI’s emphasis on information processing and data-based prediction. AI uses a probability-based approach to knowledge and is largely backward-looking and imitative, whereas human cognition is forward-looking and capable of generating genuine novelty.

The great Holy Grail of OpenAI and other AI companies is a super-intelligent generative AI that can take over innovation from humans. So far, that remains as mythical as the Holy Grail was in literature. Current GenAI can make only incremental discoveries, but cannot achieve fundamental discoveries from scratch as humans can.

But OpenAI guru, Sam Altman promises that its AI won’t just be able to do a single worker’s job, it will be able to do all of their jobs: “AI can do the work of an organization.” This would be the ultimate in maximising profitability by doing away with workers in companies (even AI companies?) as AI machines take over operating, developing and marketing everything. That’s why Altman and the other AI moguls will not stop expanding their data centres and developing yet more advanced chips, just because Chinese AI models like DeepSeek have undercut their current models. Nothing must stop the objective of super-intelligent AI.

Unfortunately, as MIT Tech explains, many AI models are notorious black boxes, which means that while an algorithm might produce a useful output, it’s unclear to researchers how it actually got there. This has been the case for years, with AI systems often defying statistics-based theoretical models. In other words, AI trainers don’t really know how AI models work. That is a major obstacle to achieving the Holy Grail.

So the AI boom is still just a financial bubble. As one commentator put it: “Generative AI does not do the things that it’s being sold as doing, and the things it can actually do aren’t the kind of things that create business returns, automate labor, or really do much more than one extension of a cloud software platform. The money isn’t there, the users aren’t there, every company seems to lose money and some companies lose so much money that it’s impossible to tell how they’ll survive.”

Meanwhile, the massive construction of data centers is consuming unprecedented levels of energy. The International Energy Agency predicts data centre electricity consumption will double to 945 terawatt-hours by 2030 — more than the current power used by an entire country such as Japan. Ireland and the Netherlands have already restricted the development of new data centres due to concerns about their impact on the electricity network. There are huge surges in power demand at data centres in training AI models, along with a bumpy renewable energy supply that threatens the resilience and capacity of current energy systems.

As for the productivity and growth outcomes, the OECD hedges its bets. If AI technologies spread and are successively implemented, the OECD reckons global labour productivity will rise by 2.4% pts over the next ten years, and add 4% to world GDP from where it would have been on current trends. However, if AI is not so successful in reducing the need for human labour and does not spread to all sectors, then labour productivity may rise only 0.8% pts above the current trend level in ten years (from the current 0.8% a year) and world economic growth will be unchanged. The jury is out.

July 19, 2025

Japan: stagnation and confusion

Tomorrow, a key election takes in the G7 economy, Japan. The focus is on whether the ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its junior partner Komeito, which together suffered a major defeat in last autumn’s lower House of Representatives election, can maintain a majority in the upper House of Councillors. The coalition government must win 50 of the 125 seats (half of the House seats) that are up for grabs. The latest opinion polls suggest that various minority opposition parties are taking around two-thirds of the potential vote among them, while the governing parties are getting only 32%.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, who heads the LDP, has intensified his rhetoric on issues appealing to conservatives, the core LDP base. He has emphasized the necessity of revising Japan’s pacifist constitution, a long-held goal of the LDP to remilitarise Japan, and has talked tough on opposing Trump’s proposed 25% tariff on Japanese exports to the US: “Do not underestimate us. Even if it is an ally that we are negotiating with, we must say what needs to be said without hesitation.” Ishiba is appealing to the ‘populist’ right, just as all ‘mainstream’ politicians in the G7 economies now do. In Japan, the ‘populist’ right is represented by the Sanseito party, which is against immigration and foreigners under the slogan “Japanese First” and has gained support among younger voters.

But those are not the main issues concerning voters. Instead, it is dissatisfaction with rising inflation, low wage growth and high taxes, leading to a wave of support for previously marginal parties that have pledged more government spending and cuts to the sales tax on all goods. The LDP has promised cash handouts and other measures to lower energy prices.

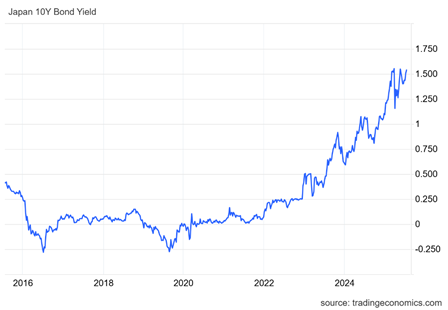

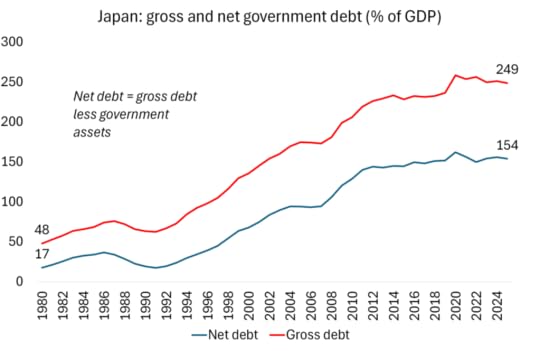

But these promised handouts can only increase the government’s budget deficits and the humongous public sector debt that Japan has. As a result, financial investors have been selling off government bonds: the yield on ten-year bonds has hit its highest level since the global financial crash of 2008.

The opposition parties are running their campaigns on attacking the rising inflation rates and calling for a cut in the 10% sales tax and the 8% food items tax to reduce the cost of living. But the sales tax is the biggest source of government revenue. In fiscal 2025, it collected 25 trillion yen ($160bn), or 21.6% of total revenues. Halving the tax rate would cut revenues by over 10 trillion yen.

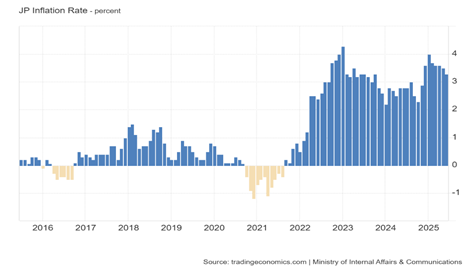

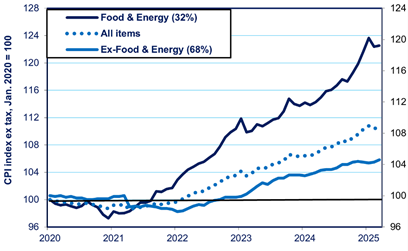

Japan used to have a near zero rate of inflation but in an attempt to revive the economy, the government and the Bank of Japan deliberately tried to boost inflation to encourage companies to invest and reduce the real burden of debt. But all that has done is eat into the living standards of Japanese households.

According to the polls, 48% of the public says combating inflation is the top issue, followed by social security at 33% and economic growth at 30%. Voters want a cut in the sales tax but do not want the revenue loss to be compensated for by reductions in social security benefits as the government has suggested would be necessary.

Source: Katz

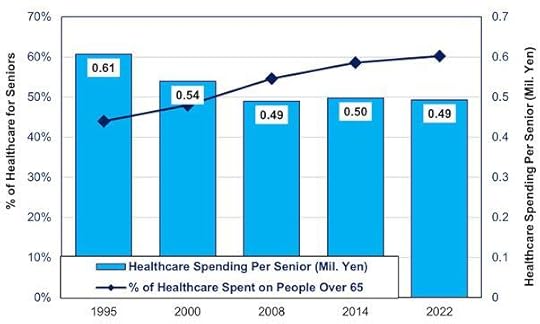

As in all G7 economies, over the decades, Japanese governments have adopted neoliberal economic policies aimed at reducing pensions and welfare benefits. Richard Katz has pointed out that the LDP coalition has lowered social security benefits for seniors from ¥2.9 million ($20,000 at today’s exchange rates) in 1995 to just ¥2.1 million ($14,500) now, a 30% decrease in price-adjusted terms. In addition, government spending on healthcare for each person over the age of 65 has been reduced by almost a fifth over the past 30 years.

Source: Katz

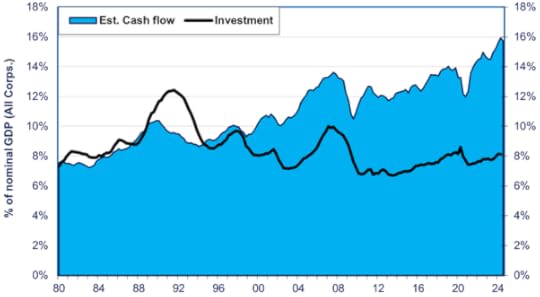

At the same time, the corporate profits tax has been slashed from 50% to just 15%. Profits have doubled from 8% of GDP to 16% but corporate tax revenue for the government has tumbled from 4% of GDP to 2.5%. These cuts in corporate profits tax have not led to improved business investment growth. Instead, companies hoarded the cash or invested in government bonds and the stock market.

Source: Katz

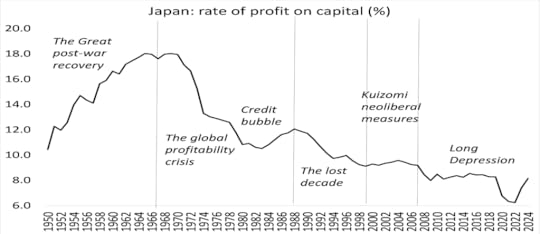

The key to the failure of these neo-liberal measures to boost corporate investment and end the stagnation of the Japanese economy since the 1990s is the decline in the profitability of capital investment. Japan’s profitability of capital has fallen more than in any other G7 economy.

Source: EWPT and AMECO series, author’s calculations

The Japanese economy has stagnated (in real GDP), continually teetering on outright recession. So investment and consumer demand has been weak. This is particularly the case with wages. Indeed, it has been a feature of the last 25 years that wages have remained stagnant, while profits have risen. This is the product of the neo-liberal policies adopted by successive governments in trying to reverse the long-term decline in the profitability of Japanese capital, with only limited success.

Even though the official unemployment rate is near all-time lows, as in other major economies, there is more ‘slack’ in the labour market than the 2.5% unemployment rate would otherwise indicate. The aggregate number of hours worked is still 2.8% below the pre-pandemic level. Companies are filling gaps in the ranks of their workforces with part-time workers at lower wages. Unemployment is low because of the massive shrinkage in the working-age population, now declining at about 550,000 per year.

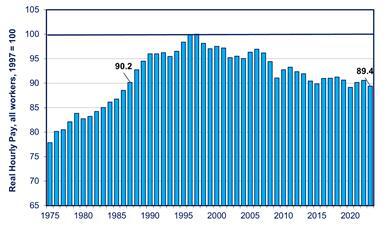

The impact on the labour market has been compensated for by a rise in female employment, but female employees work in lower wage areas and receive lower wages than males. This keeps wage share down and profit share up. Indeed, labour’s share of Japan’s national income has been falling since the end of the Japanese boom period of the 1980s; from 60% to 55% now. The median hourly pay of a full-time worker in Japan is no higher than in 1993. And the average real hourly wage of all Japanese workers—not just full-timers—is down 10% from its 1997 peak.

Source: Katz

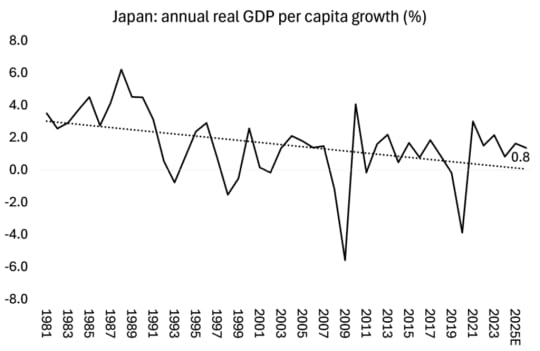

The big long-term issue is Japan’s population. It has been falling and ageing. That allows per capita income growth to grow more than total GDP growth; per capita Japan’s real GDP is up 10.8% since 2010, while real GDP is up 9.6%. But per capita real GDP growth is also slowing.

Source: IMF

Those in work are overworked. Japan invented the term karoshi — death from overwork — 50 years ago, following a string of employee tragedies. The large corporates are promoting the idea of a four-day week to relieve this pressure and increase productivity. But there is little sign that this or any other measure is working to raise productivity. Productivity growth is non-existent.

The reason is clear. Business investment growth is very weak. Japan’s corporations may have increased profits at the expense of wages, but they are not investing that capital in new technology and productivity-enhancing equipment. Real investment is no higher than in 2007. Public investment (about one-quarter of business investment) is static. Japanese capital’s image of innovating technology appears to be long gone. The mainstream measure of ‘innovation’ , total factor productivity (TFP) has faded from over 1% growth a year in the 1990s to near zero now, while the huge capital investment of the 1980s and 1990s is nowhere to be seen. So Japan’s ‘potential’ real GDP growth rate is close to zero.

Prime ministers come and go: from Abe to Kishida to Ishiba, but nothing changes. Japan has run permanent government deficits, spending it on construction and other projects and yet Japan’s economy has continued to stagnate. Japan’s huge public debt ratio will not lead to a financial crisis, as the bulk of this debt is owned by the Bank of Japan and the major banks, but it still expresses the failure of the private sector to invest.

Source: IMF

The Upper House election takes place as Japan’s export engine is spluttering and just as US President Donald Trump’s tariffs will start to hit key sectors such as automobiles and steel from 1 August. Tokyo has so far failed to reach a trade agreement with the US, despite seven trips to Washington by Japan’s trade envoy Ryosei Akazawa.

Japan’s economy contracted in the first quarter and the latest trade figures suggest that a second consecutive contraction in Q2 is increasingly likely, meeting the definition of a ‘technical recession’. If the LDP-led coalition loses its majority in the Upper House, then it may be forced to hold a general election, with the economy stagnating and the government in disarray.

July 14, 2025

Crypto corruption and un-Stablecoins

“Bitcoin is a speculation and not an investment. Not regulated, not backed by any asset, only worth what someone is willing to pay.” — Matthew Stephenson

“It’s totally absolutely crazy, stupid gambling” — the late Charlie Munger, speaking in 2023.

“Cryptocurrencies are highly volatile and therefore not really useful stores of value and not backed by anything,… It’s more a speculative asset that’s essentially a substitute for gold rather than for the dollar. ” Federal Reserve Bank chair, Jay Powell

“Bitcoin, it just seems like a scam…. I don’t like it because it’s another currency competing against the dollar.” Donald Trump, June 2021.

It’s crypto week in the US. And the price of the leading cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, has hit a record $120,000 as the US Congress prepares to consider bills aimed at creating clearer regulatory frameworks for digital assets. In the next five days, US lawmakers will consider the Genius Act, the Digital Asset Market Clarity Act, and the Anti-CBDC Surveillance State Act. The aim is to make “America the crypto capital of the world”.

The US Senate has already approved the Genius Act, a bill that enables private companies to issue ‘stablecoins’. The Anti-CBDC Surveillance State Act would prohibit the Federal Reserve from issuing a central bank digital currency, thus ensuring all the private cryptocurrencies would not have to compete against a government one.

Where is all this leading to?

The rise of cryptocurrencies began over ten years ago after the end of the Great Recession. Cryptocurrencies are digital tokens that are ‘mined’ like gold, not physically but digitally on powerful computers using what are called ‘blockchain transactions’ completely divorced from central bank issuance or control.

For a long time, the price of cryptocurrencies in dollars swung violently, but overall, cryptocurrency prices in dollars have continued to rise (along with stock market prices in the US in particular) as a new form of financial ‘asset’ to speculate with. Increasingly, cryptocurrencies are becoming recognised financial assets. More than $11bn has flowed into global funds that track cryptocurrencies this year, taking total assets under management to $176bn, according to data from UK group CoinShares.

From the start, cryptocurrency craze has been riddled with fraud, criminality and corruption – the cases of which are too numerous to mention all. In an annual report last September, the FBI revealed that fraud related to crypto businesses soared in 2023 with Americans suffering $5.6bn in losses, a 45% jump from the previous year. Sam Bankman-Fried, who founded the now bankrupt FTX crypto exchange, was sentenced to 25 years in prison in March 2024 by a New York judge for milking customers out of $8bn. Last month, the US Securities and Exchange Commission charged Unicorn, an investment platform that promised cryptocurrencies backed by real estate, with a $100mn fraud that misled more than 5,000 investors.

The dream of the techno enthusiasts that cryptocurrencies would replace state-issued currencies like the dollar or the euro and so free individuals from the ‘heavy hand of state regulation’ in a new free world of money has never materialised. Instead, what has happened is that the mega financial institutions have taken over control of these currencies and are turning them into what they hope will be a highly profitable set of financial assets to suck in investors.

The epitomy of this approach is Donald Trump himself. Having previously condemned cryptocurrencies as a scam, Trump nowhas his own cryptocurrency and disclosed almost $60mn in income last year from one of his digital currency ventures. His wife Melania has her own digital currency too. These are called ‘meme’ coins, being related to internet memes, viral moments or current events. They have ranged from tokens representing a euthanised grey squirrel, a cartoon dog and a lewd joke. Dubious promoters of these coins proliferate. CoinMarketCap, the online platform and data provider, tracks around 16.9mn cryptocurrencies — but there are millions more, leaving suckers (sorry, investors) with a bewildering number to buy. This is consumer choice under capitalism at its best.

Crypto mogul Justin Sun has publicly flaunted a $100,000 Donald Trump-branded watch that he was awarded at a private dinner at Trump’s Virginia golf club. Sun had earned this for buying $20m of the crypto memecoin $Trump, ranking him first among 220 purchasers of the token who received dinner invitations. Trump’s much-hyped 22 May dinner and a White House tour the next day for 25 leading memecoin buyers were devised to spur sales of $Trump and wound up raking in about $148m, much of it courtesy of anonymous and foreign buyers.

Sun has invested $75m in another Trump crypto enterprise, World Liberty Financial (WLF) that Trump and his two older sons launched last fall and in which they boast a 60% stake. The company, described as a “digital asset bank”, allows users to borrow, lend and invest in cryptocurrencies. The US financial regulator SEC has now paused or ended 12 cases involving cryptocurrency fraud, including three Sun crypto companies that were charged with fraud by an SEC lawsuit in 2023. They had their cases ‘paused’ in February by the agency, citing the “public interest” (!).

Does ‘crypto week’ mean that state-issued currencies like the US dollar or euro are going to be usurped by private cryptocurrencies? What gives you the answer to that is two-fold: first, all cryptocurrencies are priced in dollars – the state-issued currency that everybody uses to buy things and services. Bitcoin or other crypto currencies have not replaced dollars (or euros) for the billions of daily transactions.

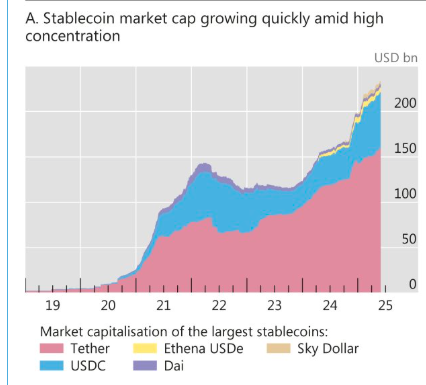

The other part of the answer is the emergence of stablecoins. A stablecoin is a crypto currency coin that is tied to an existing fiat currency, namely the US dollar, making it easy to switch (if expensively) between a crypto currency like bitcoin and an official currency like the dollar. Stablecoins are supposed to track real-world currencies and so play a central role in the stability of the broader crypto market by providing traders with a safe place to park their cash between making bets on volatile digital coins.

But that gives the game away. Stablecoins are an escape hatch out of cryptocurrencies back into ‘real money’ ie dollars or euros. Stablecoin companies can only do business as long as they have a coin that is backed by US dollar assets. These companies thus hold US dollar assets like treasury bills in order to meet any sale of their coins for dollars.

The problem here is that stablecoins are often not stable. The largest stablecoin company is Tether. Back in 2022, it was faced with a run on its coins when it emerged that it had only 4% of its assets in cash and the rest in risky commercial bills. It was able to get away with this because stablecoins were not regulated and subject to regulatory supervision or deposit insurance requirements. Now they are to be regulated. But the Genius Act “will not prevent sanctions evasion and other illicit activity and lets big tech giants like Elon Musk’s X issue their own private money – all without the guard rails needed to keep Americans safe from scams, junk fees or another financial crash,” said Senator Elizabeth Warren.

The cryptocraze shows no signs of ending. The big change now is that the cryptocurrency companies are racing to expand into traditional banking in the US, as they seek to capitalise on the crypto ‘free for all’ initiated by Donald Trump. The so-called Genius Act will tighten regulation of stablecoins and tie them more closely to US treasuries. Only regulated banks and some non-bank groups with licences will be able to issue stablecoins.

But this really means the end of ‘free private currencies’. “It’s . . . a 180 turn from where a lot of these crypto companies started, saying ‘we don’t need banks, we don’t need laws, we’re above it all’,” said Max Bonici, partner at law firm Davis Wright Tremaine. “Now they’re saying ‘regulate us’. And the big boys are moving in. Large banks, including Bank of America, are seeking to issue their own stablecoins once US regulation is finalised.

Goldman Sachs says it expects the value of stablecoins in circulation to grow from $240bn to more than $1tn within three to five years. Citigroup includes in its total addressable market estimates $195tn of cross-border transfers and $1 quadrillion of flows sent via SWIFT. JPMorgan says it’s “in the realm of possibility” for stablecoins to take 10 per cent of the $22tn US M2 money supply, or $2trn in assets.

But optimism by the big financial institutions, backed by the US president and Congress, about stablecoins becoming huge is just selling their own book. In practice, there won’t be that much demand for stablecoins as they pay no interest so that their value can be eroded by inflation. Some banks are trying to get round that. JP Morgan says it is launching a so-called “deposit token” as an alternative to stablecoins — called JPMD. The bank says JPMD will eventually enable its institutional clients exclusively to send and receive money securely on a chain representation of a bank deposit, which will pay interest.

But again this shows that private cryptocurrencies are not money. JP Morgan’s tokens are just that, like gift vouchers or supermarket points that can be used by holders only within that company alone. They are not universally usable. Like stablecoins, they have to be turned into real money like dollars through another transaction. With bitcoin, your paper gain may look good, but cashing out and realising it is different. For any sizeable amount, you need to put the crypto in an ‘external wallet’. Then you pay a high transaction cost and are also immensely vulnerable to blockchain hackers and scammers.

In global trade and finance, it is hard to make goods and money transfer between parties at the same moment, which creates risk, delay and expense. But as Steven Kelly of Yale’s Program on Financial Stability points out, “When stablecoins purport to solve that, the problem is that supply chain payments now, and in the future, demand bank money.”

Stablecoins are not money. As the Bank for International Settlements put it: proper money “can be issued by different banks and accepted by all without hesitation. It does this because it is settled at par against a common safe asset (central bank reserves) provided by the central bank…..Deposit tokens don’t have this property now and it’s hard to see how that could change”.

Money is the universal form of value; and it must be seen as universal to become money. BIS: “The foundation of any monetary arrangement is the ability to settle payments at par, ie at full value. Common knowledge of the value of money has a shorthand – the “singleness of money” – where money can be issued by different banks and accepted by all without hesitation. It does this because it is settled at par against a common safe asset (central bank reserves) provided by the central bank, which has a mandate to act in the public interest.”

The state through a central bank guarantees the value of any state-issued currency with infinite liquidity to meet demand. That does not apply to private tokens like stablecoins, even if they are now to be brought under the regulatory powers of the state. At best, stablecoins become just another financial asset, like corporate bonds or bills, not cash that can be used universally.

Moreover, the BIS argues that “crypto lacks the scalability and coordination benefits of money. As the size of the ledger grows with the volume of transactions, it becomes harder to update it quickly. The cost of transacting with crypto increases with the volume of transactions and cryptoassets cannot scale without compromising security or their decentralised underpinning.”

Cryptocurrencies are vulnerable to corruption, fraud and money laundering; and as private tokens, they function at wildly varying exchange rates to state-issued money. As such, they will allow the large financial institutions to make huge profits with no visible gain in value for society.

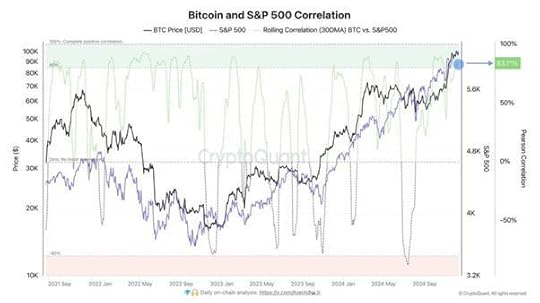

Bitcoins and other crypto currencies increasingly move in step with the prices of other forms of fictitious capital. Recent studies and market analyses show that Bitcoin’s correlation with the S&P 500 has significantly increased over the past five years. Especially during macroeconomic crises—like COVID-19, inflation spikes, or monetary policy shifts—both assets have tended to move in tandem. For instance, the 30-day correlation between them has surpassed 70%, showing shared sensitivity to global risks and monetary decisions.

As such, any future instability in financial markets and any significant downturn in the so-called ‘real economy’ will hit the crypto market and its ‘stable’ coins hard.

July 8, 2025

Just 1.6% of all world’s adults own 48.1% of all the world’s personal wealth

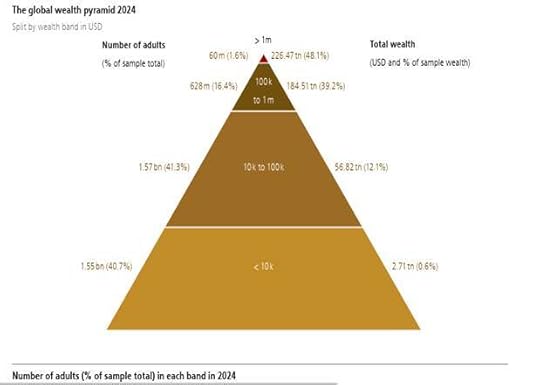

Every year, I do a post on the inequality of global wealth using the annual data compiled by economists working for the Swiss bank, Credit Suisse. But Credit Suisse is now no more, swept away by scandal and the banking crisis of 2023. The other major Swiss bank, UBS, took over the assets of CS and now produces its own annual Global Wealth report. It’s not so clear and useful as the CS ones were, but nevertheless, it still produces a global wealth pyramid, as below.

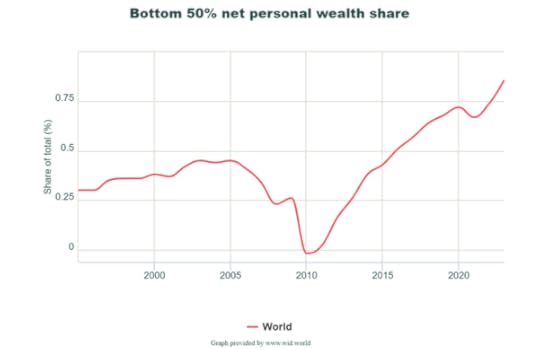

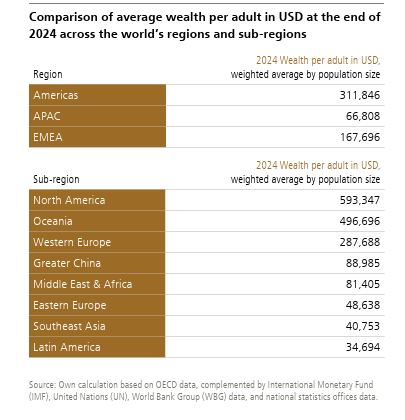

The wealth pyramid shows that just 60m adults, or 1.6% of all world’s adults, have net personal wealth of $226 trn, or 48.1% of all the world’s personal wealth. At the other extreme, 1.57bn adults (around 41% of the world’s adults) have only $2.7trn, or just 0.6% of all the world’s personal wealth! This result matches closely the estimate of the World Inequality Lab, which finds that 50% of the world’s population (not just adults) have only 0.9% of total personal wealth.

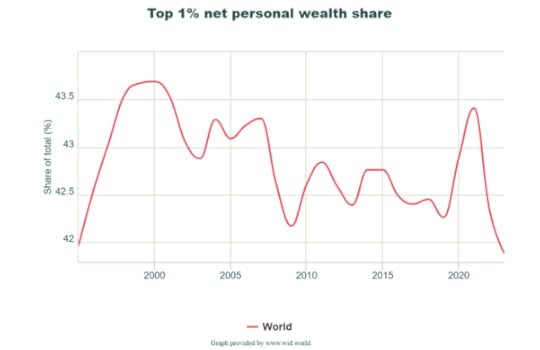

And that the top 1% of world’s population have about 42% of all personal wealth, the same as in 1995.

Indeed, if we add in the middle rung of wealth holders in the UBS pyramid, it turns out that 3.1bn adults (or 82% of all adults) have personal wealth of $61trn, or just 12.7% of total global personal wealth. The other 87.3% is owned by just 680m adults or just 18.2% of the total number of adults in the world (3.8bn). At the very top of the pyramid, there are 2,891 dollar billionaires in the world, with just 31 adults having a fortune of over $50bn each.

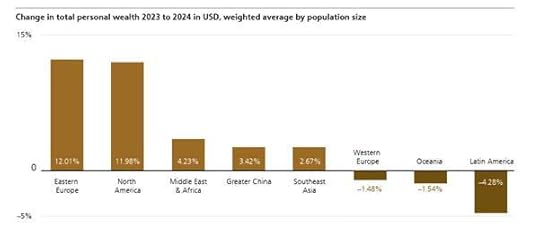

In 2024, personal wealth rose most in Eastern Europe (from a low level) and North America, but fell in Latin America, Western Europe and Oceania (Australia etc). Average household wealth in Britain fell 3.6% in 2024, the second largest drop of any major economy.

The rise in North America was mainly due to the rise in the value of stocks and bonds for the very rich. Globally, total financial wealth leapt 6.2%, while non-financial wealth (property) expanded just 1.7%. Average personal wealth per adult in North America is nearly six times higher than in China, 12 times higher than in Eastern Europe; and nearly 20 times higher than in Latin America.

According to the UBS report, the extreme inequality of personal wealth globally has worsened (if only slightly) since the start of the 21st century. Post-apartheid South Africa remains top of the world league for inequality of wealth as measured by the gini coefficient for inequality, followed as always by Brazil. And that gini ratio has worsened significantly during the Long Depression since 2008. Of the advanced capitalist economies, Sweden has the most unequal distribution of personal wealth, something that may surprise those who praise social democratic Scandinavia. The US is as unequal as Sweden.

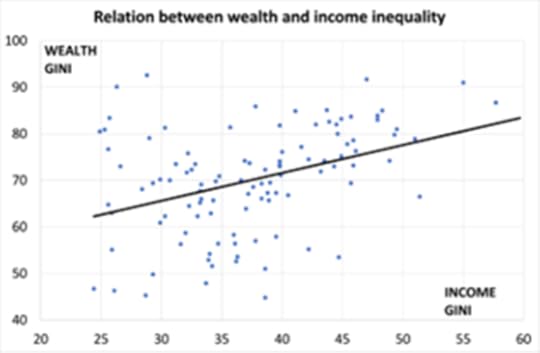

Remember these are measures of wealth, ie what is owned net of debt by each adult globally. The pyramid is not a measure of personal income inequality. But I have found in previous analyses that wealth and income are closely related. There is a positive correlation of about 0.38 between wealth and income; in other words, the higher the inequality of personal wealth in an economy, the more likely is it that the inequality of income will be higher.

Inequality analysts like Gabriel Zucman and Saez echo Marx’s view when they say that “progressive income taxation cannot solve all our injustices. But if history is any guide, it can help stir the country in the right direction, …. Democracy or plutocracy: That is, fundamentally, what top tax rates are about.” But having said that, the cause of high and rising inequality is to be found in the process of capital accumulation itself. It is not primarily the lack of progressive taxation of incomes or the lack of a wealth tax; or even the lack of intervention to deal with tax havens. Such policy measures would certainly help to reduce inequality and deliver badly needed government revenue. But if pre-tax income from capital (profit, rent and interest) continues to rise at the expense of income from labour (wages), then there is a built-in tendency for inequality to rise. And if capital continues to accumulate, then those that own the bulk of it will get richer compared to those who own no capital. Rising global inequality will not be reversed by a redistribution of wealth or income through taxation alone. It will require a complete restructuring of the ownership and control of the means of production and resources globally.

July 4, 2025

Dollar v euro

This week, the world’s major central bankers have gathered in the sweltering heat of Sintra, Portugal (although I am sure the the aircon is good in their swanky hotel in the hills). The big issue, according to the financial media, is whether the US dollar is going to continue to fall, raising the further issue of whether dollar dominance in world markets is coming to an end – and with it, the ‘exorbitant privilege’ that the US has in controlling the supply of world’s main trading and financial currency.

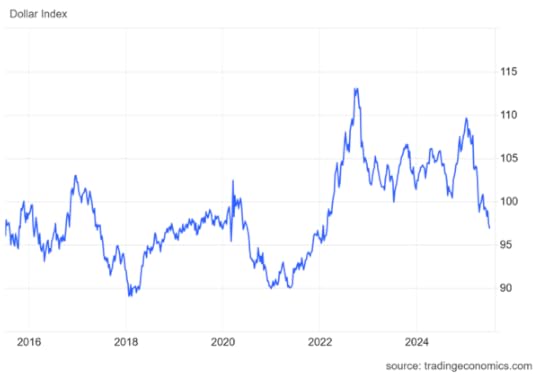

It’s true that that dollar has dropped against other major currencies to its lowest levels in three and half years since Donald Trump took office in January. His tariff tantrums and wild reversals have increased uncertainty in international trading and for investors about whether to hold their purchases and assets in dollars.

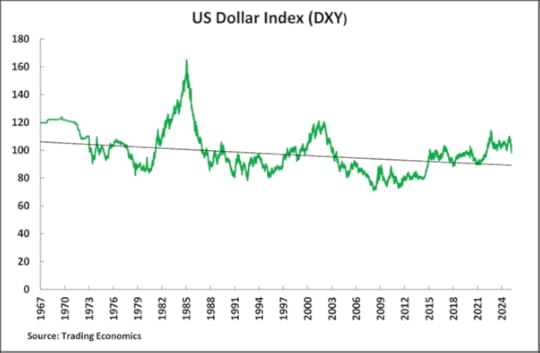

But is that the real reason for the fall in the dollar? First, the US dollar may be at a 3-year low against other currencies but that is only because it was historic highs back then. Over a much longer period, the dollar is by no means weak against the the euro, the pound, the yen, or renminbi.

The value of the dollar has plunged about 9% since January, with a 4.5% drop in April alone. But even after the impact of the Trump tariff tantrums, the dollar index is pretty much in line with where it was ten years ago.

In my view, the real reason that the dollar has recently weakened against the euro and other currencies is that the US economy is slowing down and there is now pressure on the US Federal Reserve to cut its policy interest rate to reduce borrowing costs, mortgage rates and debt servicing costs for businesses and households.

Fed Chair Powell is under tremendous pressure to cut interest rates which is has been reluctant to do because he expects Trump’s tariff measures to lead to a move up in consumer inflation rate. Trump is demanding that he resign immediately so that he can appoint a Fed chair that will slash interest rates.

The Fed’s monetary policy committee (FOMC) is split over whether to keep interest rates up, supposedly to keep inflation down; or instead cut rates to help the US economy. This dilemma is really a false dichotomy because monetary policy enacted by central banks does little to ‘manage’ capitalist economies, whether to ‘control inflation’ or ‘boost growth’.

Nevertheless, there is increasing expectation that the Fed wil accelerate its rate cuts through the rest of this year and so reduce the differential between US interest rates and those in Europe and Japan. This will make it less attractive to hold dollar assets keeping the dollar weaker than before.

But none of this means that the dollar will lose its hegemonic status in world markets. To think so is wishful thinking at best and a bad misjudgement on the strength of the other major economies. ECB President Lagarde applied some of that wishful thinking a few weeks ago when she said that: “The euro could become a viable alternative to the dollar… creating the opening for a ‘global euro moment.” Seriously! Has Lagarde not noticed the stagnation of the major economies in Europe?

Here are the latest annual growth (yoy) rate figures for the leading economies:

India 7.4%, China 5.4%; Brazil 2.9%, Canada 2.3%.US 2.0%, Japan 1.7%, Russia 1.4%, UK 1.3%, South Africa 0.8%; Italy 0.7%, France 0.6%, Germany zero,

They show that, within the G7 top economies, Canada and the US economies are doing twice as well as in the European economies. The economies of Europe are stagnating; it’s just that the US is beginning to join the stagnant European economies. The latest US real GDP data show a fall of 0.5%, while US manufacturing remains in contraction territory (below 50 on the graph).

This is the reason why the dollar is weakening and why the Fed is likely to cut its interest rates. But the dollar still makes up 58% of international reserves, well above the euro’s 20% share. Lagarde’s wishful thinking is just that.

June 30, 2025

Sustainable development and unsustainable debt

Today, world leaders gather in Seville, Spain for a UN aid summit for developing countries. This is the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development. At least 50 world leaders including French President Macron, EU chief von der Leyen and UN head Guterres will be there. The conference is supposed to boost flagging support for global development, the so-called sustainable development goals set decades ago by the UN, with the aim of taking the poor countries and their people out of poverty.

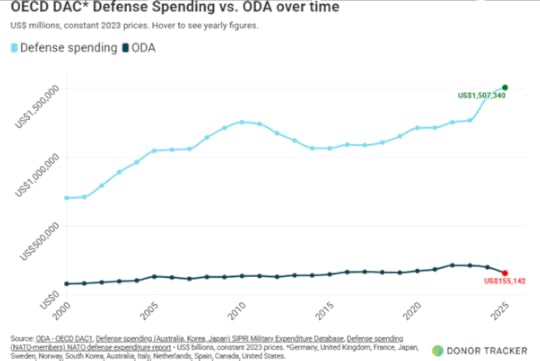

These laudable aims have, like many UN initiatives in the 21st century, proven unsustainable. As the world leaders pontificate this week in Seville, the reality is that the gap between the rich countries and the rest of the world has not closed – on the contrary it has widened. And instead of renewed efforts to boost funding for the so-called developing world, the opposite is happening. US President Trump has gutted the funding and personnel of the US development agency, USAID. USAID funding is expected to fall from $60bn in 2024 to less than $30bn in 2026. Germany, Britain and France, among other rich economies, are also making cuts in order to finance huge rises in arms spending for war.

The Group of Seven (G7) countries, which together account for around three-quarters of all official development assistance (ODA), are set to slash their aid spending by 28 percent for 2026 compared to 2024 levels. This would be the biggest cut in aid since the G7 was established in 1975 and indeed in aid records going back to 1960.

Next year will mark the third consecutive year of decline in G7 aid spending – a trend not seen since the 1990s. If these cuts go ahead, G7 aid levels in 2026 will crash by $44 billion to just $112 billion. The cuts are being driven primarily by the US (down $33 billion), Germany (down $3.5 billion), the UK (down $5 billion) and France (down $3 billion).

The international charity Oxfam says the cuts to development aid are the largest since 1960 and the UN puts the growing gap between what is needed for sustainable development and what is delivered at $4 trillion. “The G7’s retreat from the world is unprecedented and couldn’t come at a worse time, with hunger, poverty, and climate harm intensifying. The G7 cannot claim to build bridges on one hand while tearing them down with the other. It sends a shameful message to the Global South, that G7 ideals of collaboration mean nothing,” said Oxfam International Executive Director Amitabh Behar.

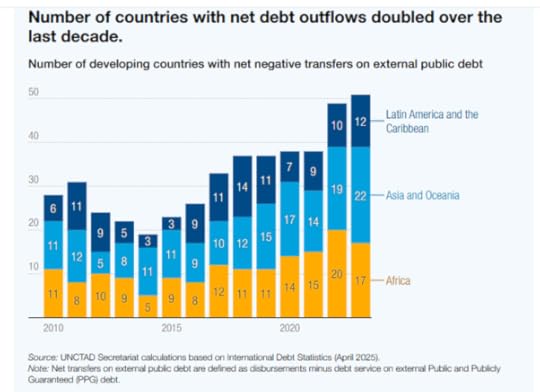

Poor countries are not only getting less financial support; they are experiencing an ever-rising burden of debt owed to the rich countries’ banks and financial institutions. The total external debt of the group of the least developed countries has more than tripled in 15 years, according to the UN. Total debt in the so-called emerging economies (excluding China) has reached 126% of their GDPs. Total external debt stock of the poor countries hit at an all-time high of 8.8 trillion in 2023, up 2.4 percent from the previous year.

Debt repayments are now greater than new inflows of credit and capital. In 2023, low- and middle-income countries (excluding China) experienced a net outflow to the private sector of $30bn on long-term debt — a major drain on development. Since 2022, foreign private creditors have extracted nearly $141 billion more in debt service payments from public sector borrowers in developing economies than they disbursed in new financing. For two years in a row now, the external creditors of developing economies have been pulling out more than they have been putting in.”

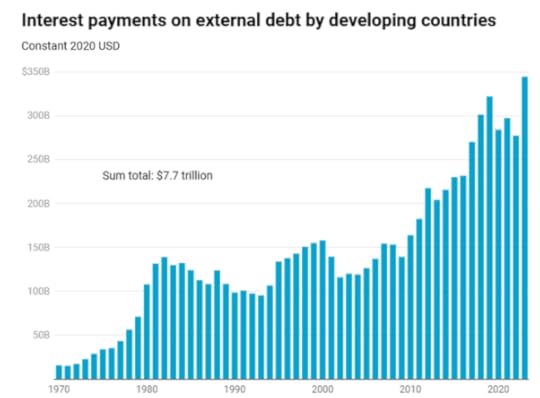

The total debt servicing costs (principal plus interest payments) of all LMICs reached an all-time high of US$1.4 trillion in 2023. Excluding China, debt servicing costs climbed to a record of US$971 billion in 2023, an increase of 19.7 percent over the previous year and more than double the amounts seen a decade ago.

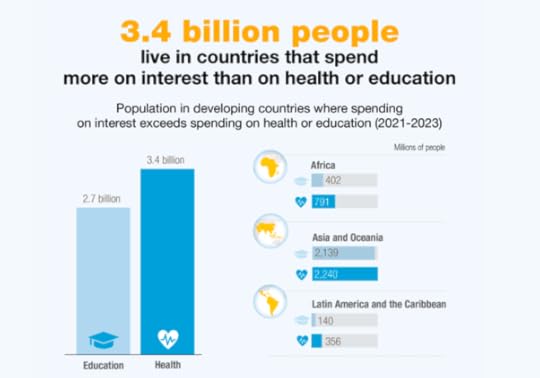

A recent report commissioned by the late Pope Francis and coordinated by ‘Nobel’ laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz reckons that 3.3 billion people live in countries that fork out more on interest payments than on health. Recent data from the UN’s trade and development body, UNCTAD, reveal that 54 countries spend over 10 percent of their tax revenues on interest payments alone. The average interest burden for developing countries, as a share of tax revenues, has almost doubled since 2011. More than 3.3bn people live in countries that now spend more on debt service than on health, and 2.7bn in countries that spend more on debt than on education.

Global aid for nutrition will fall by 44 percent in 2025 compared to 2022: The end of just $128 million worth of US-funded child nutrition programs for a million children will result in an extra 163,500 child deaths a year. At the same time, 2.3 million children suffering from severe acute malnutrition – the most lethal form of undernutrition – are now at risk of losing their life-saving treatments. One in five dollars of aid to poor countries’ health budgets are to be cut or under threat: WHO reports that almost three-quarters of its country offices are seeing serious disruptions to health services, and in about a quarter of the countries where it operates some health facilities have already been forced to shut down completely. US aid cuts could lead to up to 3 million preventable deaths every year, with 95 million people losing access to healthcare. This includes children dying from vaccine-preventable diseases, pregnant women losing access to care, and rising deaths from malaria, TB, and HIV.

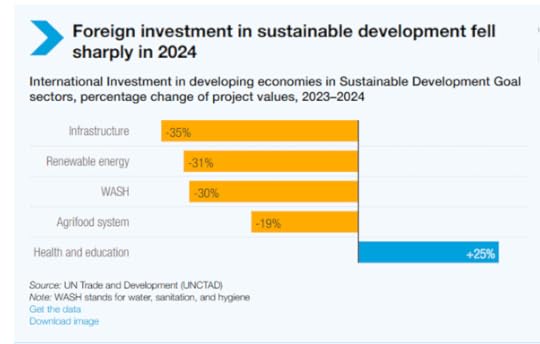

According to a new report by UNCTAD for the Seville conference, sectors critical to the Sustainable Development Goals suffered in particular from a drop in foreign investment. Investment flows to developing countries for infrastructure fell 35%, renewable energy 31%, water and sanitation 30% and agrifood systems 19%. Only the health sector saw growth. Projects rose by about one fifth in number and value, but total volumes remained small – under $15 billion.

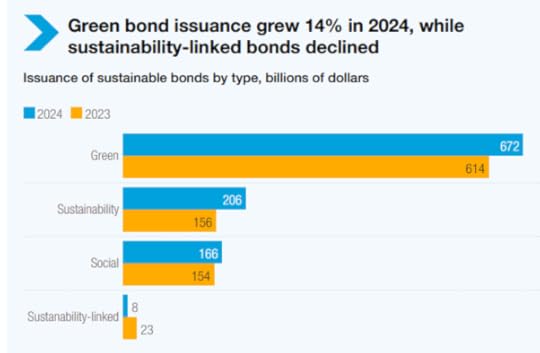

Before the conference in Seville began, the US announced that it would not be attending or agreeing to any plan. So some governments made a declaration. They came up with a feeble proposal, not binding on them and with no justification for implementing it, namely that the various development banks around the world should triple their lending capacity, particularly for “essential social spending”. And there should be “more cooperation against tax evasion”. Some hope. In reality, loans and bonds to carry out sustainability goals have declined.

In a previous post, I showed that the countries of the so-called Global South are not ‘catching up’ with the rich imperialist countries of the so-called Global North, either in income per person, in productivity, or by any index of human development. At the same time, the huge inequalities of income and wealth, between and within countries, continue to worsen.

What is the answer? Not more loans from banks and governments at exorbitant and rising interest rates (the UK or Germany borrows at 3 -4%, while developing countries are charged 6-8%), but instead the cancellation and writing off of existing debt burdens for poor countries (I don’t like the word debt ‘forgiveness’ as there is nothing to forgive).

And then what is needed is a global plan for public investment in the Global South aimed at infrastructure, health, education and public services, alongside support for employment-creating technologies and industries. This could easily be financed by the rich countries with a wealth tax on the very rich and by public ownership of the major banks and multinationals that currently dominate global finance. Of course, that won’t happen without revolutionary changes in the Global North.

June 25, 2025

AHE 2025: imperialism, China and financialisation

Last week the annual conference of the Association for Heterodox Economics (AHE) took place in London. I quote from the AHE website: “Formed in 1999 to provide an annual conference where all heterodox (that is, Post Keynesian, Marxian, Sraffian, Institutional-evolutionary, social, Austrian, and feminist) economists could gather and hear each other presenting papers on theoretical, applied, and policy topics and issues that utilized their heterodox economics”. So the AHE is an academic forum for economists not considered part of the mainstream. But that does not mean heterodox economics, as opposed to ‘orthodox’ economics, is socialist or even anti-capitalist.

For me, there are three schools of economic thought: mainstream, heterodox and Marxist. As I put it in a presentation to a Rethinking Economics conference back in 2019, “there was one thing that unites the mainstream and the heterodox (in every form) and one thing in which Marxian economics stands out: namely the labour theory of value and surplus value. The neoclassical and all the heterodox from Keynes to Kalecki, Robinson, Minsky, Keen and the MMTers deny the validity and relevance of Marx’s key contribution to understanding the capitalist system: that is it is a system of production for profit; and that profits emerge from the exploitation of labour power – where value and surplus value arises.”

But let’s move on. The very well organised AHE 2025 conference brought together economists from all schools and from many parts of the world to present a myriad of papers along with plenary sessions on key geopolitical issues. And here I must make an apology. I was invited to participate in a panel of authors providing chapters in a new book on radical economics. But I failed to attend – succumbing to a heatwave (at least by UK standards) on the day. That’s the first time I have missed a committed meeting. I shall return to the book later in this post.