Michael Roberts's Blog, page 8

December 20, 2024

Profitability, investment and the ‘silent’ depression’ -a new book

Ascension Mejorado is Clinical Professor and Economics Faculty Chair in the Liberal Studies program at New York University and Manuel Roman taught economics at New Jersey City University, US for over 25 years and is now retired. They have authored a superb book that analyses the US economy from a Marxist perspective and in so doing provides yet more empirical support for Marx’s law of profitability and its essential relevance to crises in capitalist production.

Entitled, Declining Profitability and the Evolution of the US Economy: A Classical Perspective, Mejorado and Roman take the reader on a journey through Marxist crisis theory using the latest data from the US economy.

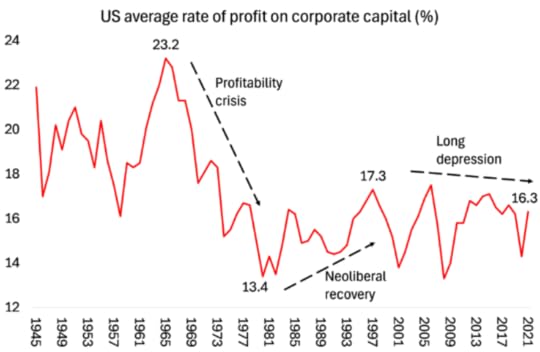

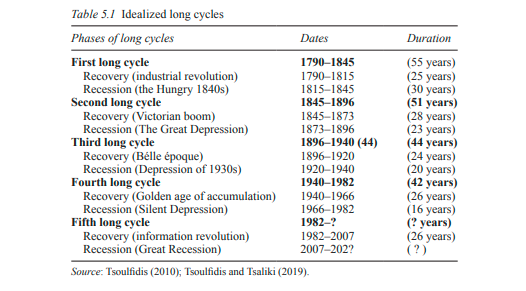

The main argument is stated clearly: “It is our contention, as that of all great economists, including Marx and Keynes, that business profitability drives the accumulation of capital and that at the advanced stages of that process, the system’s growth rate declines because falling profitability saps the incentive to expand the stock of fixed capital assets…. The relationship between falling profitability and the capital accumulation trend is structurally binding.” They show that that long-term falling profitability in the US led to corresponding periods of falling capital accumulation rates, periodically punctuated by ‘recessions’ and brief recoveries.

In the decades leading up to the stagflation crisis of the 1970s, declining profit rates undermined the foundations of capital accumulation. In the 1980s, this forced US capital to deindustrialize at home and turn financial investment. Declining interest rates spurred financial bubbles and paved the way for major financial crises in the 21st century.

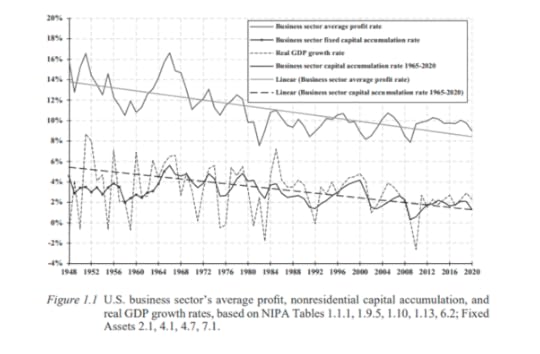

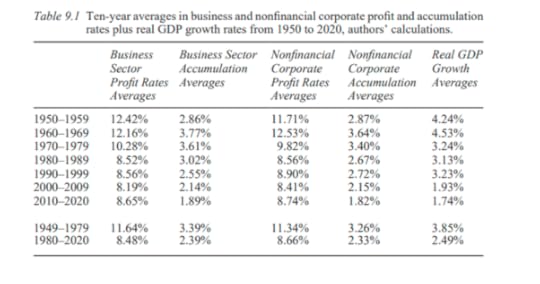

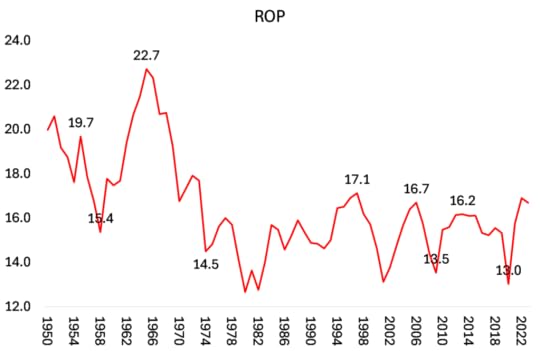

In Figure 1.1 above, from 2001 to 2020, the gross profit rate, defined as business sector net operating surplus on current cost net capital stock, averaged 8.6 percent. At that level, it was 28.2 percent lower than in the first three decades of the postwar period, when it reached a 13 percent average. Similarly, the average rate of capital accumulation in the nonfinancial corporate sector, from 2001 to 2020, at an average of 2.82 percent, was 22 percent lower than in the first three decades of the postwar, when it reached 3.6 percent average.

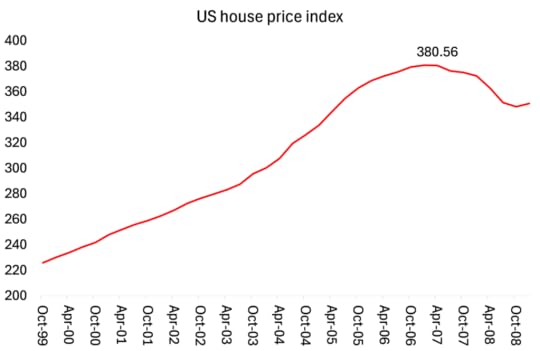

Most interesting, Mejorado and Roman show that “contrary to the neoclassical conventional wisdom, the Federal Reserve’s policy of lowering interest rates since 1984 had very little effect on nonfinancial capital expenditures.” Indeed, the long-term trend of non-residential capital accumulation in the real economy declined from 1965 to the present. What low interest rates did achieve was a credit-fuelled boom in housing mortgages and household debt that eventually triggered the financial crisis in 2007-8.

“Raising interest rates to combat inflation will not dampen investment growth if business profitability is high enough as it was in the 1970s, and lowering interest rates will not increase nonfinancial corporate investment when profitability is low or falling as it has been since 2000. Falling interest rates did not spur nonfinancial corporate investment. Instead falling interest rates stimulated mortgage buying by households: there is an inverse relationship between interest rates and the share of disposable income households devoted to the purchase of mortgages.” https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2024/08/26/jackson-hole-celebrates-itself/

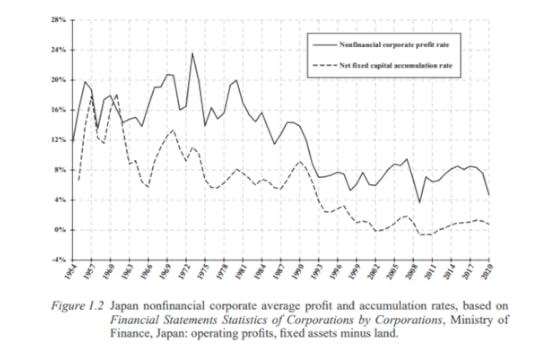

In passing, they take to task Japanese Marxist Takuya Sato’s claim that Marx’s law of the falling rate of profit did not apply to 21st century Japan (Sato wrote this in a chapter of the book, World in Crisis, edited by G Carchedi and myself in 2018).

They find that the relationship between the profitability trend of nonfinancial corporations and the capital accumulation in Japan is highly correlated and this “confirms the existence of a remarkable parallelism between them from 1954 to the year 2020, not a bifurcation in the 21st century. Japan’s economic development confirms the structural links binding profitability and accumulation trends at the higher stages of capitalist development.”

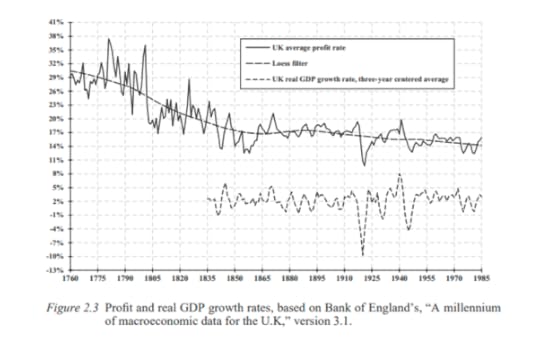

The same story applies to the UK. The authors provide a measure of the rate of profit there back to 1760.

I did something similar in my chapter on the UK rate of profit in World in Crisis.

Mejorado and Roman also reject the idea that the wide gap between the profitability of the top US corporations and the unprofitable ‘zombie’ companies (often referred to on this blog) is the result of monopoly power exerted by companies at the peak of the corporate pyramid. “On the contrary, it is a testimony to their superior competitive power and success in the ever-going race to conquer market share. We interpret the profitability gap in the ‘dual’ economy consisting of superstar firms at one end and zombies at the other as the end result of competition-as-war, not evidence of monopoly power as liberal critics like Stiglitz and Mazzucato insist.”

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2017/03/06/getting-a-level-playing-field/

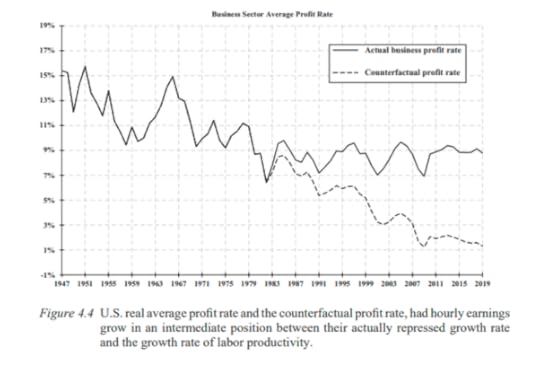

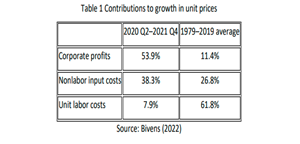

Under neoliberalism, there was a major reorientation of capital investments from domestic to offshore manufacturing and the expansion of domestic services created a dual economy with financial trading in the lead. In combination with the compression of wages, neoliberal changes improved business ‘competitiveness’. So there was a significant rise in the rate of surplus value that helped to sustain profitability. To demonstrate this argument, Mejorado and Roman plotted a counterfactual path of would have happened to the average profit rate if wage share in GDP had not been held down as it was after the 1980s. The business sector average rate of profit would have plummeted to unsustainable low levels.

G Carchedi did a similar analysis in his chapter on the US rate of profit in our book World in Crisis (pp49-57).

In the neoliberal period, the share of corporate profits allocated for purposes other than fixed capital investments sharply increased and, correspondingly, the share directed to finance plant and equipment declined. The share of financial profits relative to all corporate profits rose from less than 10 percent in the late 1940s to nearly 40 percent in 2002 before settling down to over 25 percent in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–2009. This was the reason for the widening gap between the top companies and the so-called zombies.

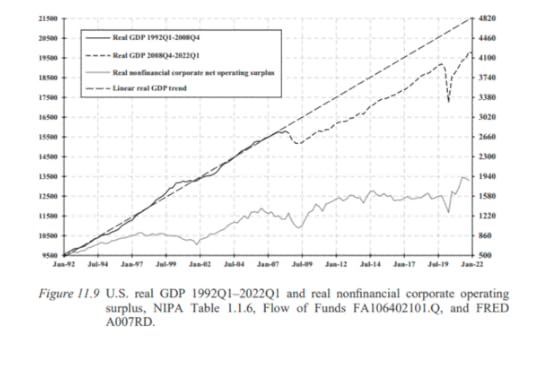

The long-run growth trend in nonfinancial capital accumulation continued to fall throughout the neoliberal phase from the early 1980s to 2001 because US profitability never got back to 1970s levels, let alone the trend levels of the earlier postwar period. In 2001, profitability fell to its lowest trough and since the recovery from the Great Recession, and from 2012 to 2019 the mass of real profits in the nonfinancial corporate sector stagnated.

The authors argue that since the 1980s, the diversion of capital to purchase financial assets has contributed to the decline in labour productivity growth and the widening of financial fragility. Falling interest rates led to intermittent bouts of euphoria and inflated financial assets. But rising financial valuations are not sustainable if they transgress the income growth limits of the real sector, as they did in 2007-8. And now significant numbers of so-called ‘zombie’ companies will be in jeopardy if interest rates stay high in response to rising inflation.

The authors refer to a ‘silent depression’ in the period from 2012 to 2020 when there was a stagnation of the mass of nonfinancial corporate real profits from 2012 to 2020. This long depression (as I call it) happened because the weak zombie companies were not sacrificed in the Great Recession to benefit overall profitability. Instead “ Federal Reserve measures to prop up the banks contributed to the preservation of insolvent ‘zombie’ companies” … Losers can only remain standing as long as central banks provide them with low interest rates and the possibility of accumulating debt. Estimates of the share of ‘zombie’ public companies in the U.S. economy that cannot even meet their interest obligations out of their revenues rose from around single-digit percentage to about 20 percent in 2020.”

Most important, Mejorado and Roman show that it is the movement in the rate and mass of profits that leads to an investment collapse and a hoarding of cash, with the subsequent collapse in ‘effective demand’, not vice versa. “For Marx, an increase in the demand for idle money, at the aggregate level, takes place when the capitalist class as a whole is induced to regard investment and production as not profitable. In this way, Marx linked the analysis of effective demand to the analysis of the fundamental factors underlying capitalist production and growth.”

The authors compare the restoration of profitability for nonfinancial corporate business after the Great Depression with that of the Great Recession. The profit rate plunged in the 1930s and by 1938 it fell substantially below the level reached in the late 1920s. I have made a similar observation and measurement in a post. But profit rates recovered during the world war and reached historically high levels in the 1940s and remained elevated for 20 years of the ‘glorious’ Golden Age. But that did not happen in the slumps of 2009 and 2020. That’s because there was no ‘cleansing’ of the weak to boost profitability as in the 1930s.

So Mejorado and Roman do not expect the ‘silent depression’ to end. “Given the extended path of secular stagnation, low capital accumulation trends in the real sectors, and the build-up of financial fragility in the banking scaffold that fueled asset bubbles, the depression “is likely to persist” as “a chronic condition of subnormal activity for a considerable period without any marked tendency either towards recovery or towards complete collapse” (quote from Keynes).

December 15, 2024

Overproduction or overaccumulation? – the debate

Back last November, the excellent Argentine Marxist economist, Rolando Astarita presented on his blog the case for ‘overproduction’ as the cause of crises under capitalism, denying the role of Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as being relevant. He argued that Marx and Engels never mentioned the law in relation to crises in their works and in explaining any crises in the 19th century. They always referred to ‘overproduction’. And there was no evidence that a falling rate of profit preceded or causes periodic crises.

This led to reply by Spanish Marxist Daniel Alabarracin in the Spanish online journal, Sin Permiso. Here is Albarracin’s critique. https://www.sinpermiso.info/textos/sobre-las-crisis-ciclicas-y-la-ltdtg-y-el-aceleracionismo-de-rolando-astarita. Astarita responded, saying that Albarracin’s critique was ‘baseless’ because he (Astarita) did accept that profitability affects capital accumulation. But he did not accept that Marx’s law of profitability was a cause of crises, however. That was down to ‘overproduction’. Here is Astarita’s reply to Alabarracin. https://www.sinpermiso.info/textos/ltdtg-una-critica-sin-fundamento.

At this point, yours truly waded in.

Now I have always disagreed with the view that ‘overproduction’ is the cause of cyclical crises. For me, overproduction is a description of a crisis or slump, not a cause. I had been having a private correspondence with Rolando on this question of overproduction or overaccumulation as the cause of crises. So I decided to publish my view in Sin Permiso. Here is my reply to Rolando’s arguments. I show this in full below, as it is more accurate than the submission in Sin Permiso which has a few misprints and actually includes a section on Mandel’s views which are not mine, but Rolando’s.

“Dear Rolando,

I was surprised and disappointed on reading your latest post on the causes of cyclical crises in capitalism. I did not realise that you adopted what I consider is the false, outdated and empirically unsupported view that crises under capitalism are caused by ‘overproduction’ and that it has nothing to do with the movement of profitability and profits in capitalist accumulation. This overproduction thesis has been presented by a succession of theorists like Tugan-Baranovsky, Hilferding, Maksakovsky, Moszkowska, and Simon Clarke. I thought this theory had been refuted many moons ago.

First, you claim that Marx never explained cyclical crises by his law of profitability. You back this claim by saying that “when he wrote about the crisis of 1847 he did not mention the law.” Well, that is not surprising as he had not developed the law by then. But you go on to claim that “nor did he do so in passages referring to the crises of 1866 and 1873. And in chapter 17 of volume II of Theories of Surplus Value , devoted to capitalist crises.”

This smacks of the argument presented by German Marxist Michael Heinrich that Marx dropped his law of profitability after 1865 as an explanation of crises because he thought it no longer worked. And yet Engels in his preface to Capital Volume 3 notes that Marx spent some considerable time looking at the relation of the rate of profit to the rate of surplus value in the 1870s (in contradiction to the claim that he dropped the law). Indeed, much of Engels’ preface is about the relation of the rate of profit to the rate of surplus value. If the law had been dropped, why discuss this? And more to the point, why did Engels include three key chapters on the role of the rate of profit in Capital Volume 3?

You say that there is no reference to the law of profitability in Chapter 17 of Volume 2 of Theories of Surplus Value which discusses theories of crisis by classical economists. Well, that is open to debate. Let me give you some quotes from that chapter.

“In capitalist accumulation it is a question of replacing the value of capital advanced along with the usual rate of profit”. This suggests that the rate of profit is very relevant to capital accumulation. And this: “it must never be forgotten that in capitalist production what matters is not the immediate use value but the exchange value and in particular the expansion of surplus value. This is the driving motive of capitalist production” So profit is the motive force of capitalism not production (or thus overproduction). And “the destruction of capital through crises means the depreciation of values which prevents them from renewing their productive process”. It’s the depreciation of value not the collapse of demand that is key to crises and the subsequent recovery.

You refer to the note that Marx makes that “permanent crises do not exist”. But the full quote is revealing: “When Adam Snith explains the fall in the rate of profit from an overabundance of capital, an accumulation of capital, he is speaking of a permanent effect and this is wrong. As against this, the transitory over-abundance of capital, overproduction and crises are something different (my emphasis). Permanent crises do not exist.” So Marx directly refers to the ‘temporary’ over abundance of capital as relevant to crises – overabundance here means relative to profit or profitability, not demand. Even more explicitly, he says: “the transition from the phrase overproduction of commodities to the phrase overabundance of capital is indeed an advance…”

And there is more. He goes on to explain the law of profitability: that if constant capital rises more than variable capital, then the rate of profit will fall. “The rate of profit falls because the value of constant capital has risen against that of variable capital and less variable capital is employed”. ….hence crisis is “a crisis of labour and crisis of capital”. With the rate of profit “decreasing … it is a case of overproduction of fixed capital.”… “Crises are due to an overproduction of fixed capital” (my emphasis).

Marx even makes points against overproduction as a cause: “it goes without saying that it is not be denied that too much may be produced in individual spheres and thus partial crises can arise from disproportionate production” BUT “ we are not speaking here of crisis in so far as it arises from disproportionate production” He goes on: “the limits to production are set by the profit of the capitalist and in no way by the needs of the producers.”

And this next statement is even clearer: “it is the barrier set up by the capitalists’ profit, which forms the basis of overproduction.” …“Overproduction is specifically conditioned by the general law of the production of capital”. And that “accumulation depends not only on the rate of profit but on the amount of profit”. And “accumulation for its part is not directly determined by the rate of surplus value but by the rate of surplus value to total capital outlay, ie the rate of profit and even more by the total amount of profit.”

All these quotes indicate that Marx saw profit and profitability as key to the movement of capital accumulation and it is the overabundance of capital relative to profit that leads to overproduction of commodities ie crises.

This is even more explicitly stated in Capital Volume 3, Chapters 13 to 15, where I think you struggle to deny the role of profitability in causing crises. You say you can only find two vague references to the rate of profit and crises. Are we reading the same chapters? It is very explicit to me. Anybody who reads these chapters can see Marx is directly relating profitability and profits to cyclical crises.

More quotes:

“The periodical depreciation of existing capital offer the means immanent in capitalist production to check the fall in the rate of profit and hasten the accumulation of capital value through the formation of new capital and disturbs the existing conditions within which the process of circulation and reproduction of capital takes place, and is therefore accompanied by sudden stoppages and crises in the production process”. So the rate of profit falls and it is necessary eventually to have a crisis ie a depreciation of existing capital, to restore profitability and resume the reproduction process.

Crises are caused by “an overproduction of capital, not of individual commodities, although over production of capital always includes overproduction of commodities, which is therefore simply over accumulation of capital.” ….“Overproduction of capital is never anything more than overproduction of the means of production which may serve as means of capital.”

There is a moment of absolute over accumulation of capital “when increased capital produces just as much or even less surplus value than it did before its increase…” and again “ultimately the depreciation of the elements of constant capital would itself tend to raise the rate of profit … the ensuing stagnation of production would have prepared within capitalistic limits a subsequent expansion of production. And thus the cycle would run its course anew.” So Marx says the law of profitability produces cyclical crises, which you deny.

“It is overproduction of the means of production only in so far as the latter serve as capital and consequently include a self expansion of value, which must produce an additonal value in proportion to the increased mass”. ……“Capital grows much more rapidly .. to contradict the condition under which this swelling capital augments its value.” Hence the crisis is because “It is a matter of expanding value not consuming it”.

More. “the rate of profit is the motive power of capitalist production. Things are produced only so long as they can be produced at a profit.” That’s why: “The development of the productivity of labour creates out of the falling rate of profit a law which at a certain point comes into antagonistic conflict with this development and must be overcome constantly through crises.” (my emphasis) That’s pretty clear where Marx stands on profitability and crises.

Your interpretation of these chapters is that Marx only shows that a falling rate of profit leads to falling investment growth and thus ‘stagnation’, not cyclical crises. This does not seem to match the quotes above. Moreover, there is the question of the relation between profitability and the mass of profit which you too refer to. This is crucial because it is when the mass of profit turns down, that investment collapses. Marx does not have a stagnation theory similar to Keynes.

You refer to Thomas Weisskopf that if the LTRPF is a theory of crises, it must also be a theory of accumulation. Sure, and such a theory is clearly there in Marx. For capitalists to accumulate, they will increasingly invest in constant capital relative to variable capital. And as Marx’s law of value says that only labour power can create new value, there will be a tendency for the rate of profit to fall. And if profitability does fall, then accumulation growth will eventually slow or even collapse. This links Marx’s general law of accumulation in Capital Volume 1 with the LTRPF in Volume 3.

You want the relationship between overproduction and crises to be ‘clarified’. Marx’s law does that. As the rate of profit falls, eventually it can cause a fall in the mass of profit. There is an overaccumulation of capital expressed as an overproduction of commodities at existing prices. That overproduction is resolved by a depreciation of capital (both constant capital and labour) and which includes the wastage of commodities. Thus it is an overaccumulation of capital that causes an overproduction of commodities. Overproduction of commodities is thus a description of crisis, but not the cause. As you say; “crisis (is not) due to underaccumulation or underinvestment, but rather overaccumulation or overinvestment.” But that means overaccumulation relative to profitability or profit, not ‘demand’.

The overproduction thesis assumes that supply and demand are independent of each other. That is certainly not Marxist theory (see the Preface to the Contribution). The mismatch between supply and demand is the outcome of the crisis, not the cause. A question can be asked here. If supply is in line with demand, can a crisis of production materialise? Marx’s law of profitability says that it can and will because crises are not caused by a mismatch of production over demand, but a mismatch between the accumulation of capital and profit.

You claim that it was overproduction prior to 2007 that caused the Great Recession of 2008-9. Your evidence was “signs of a glut in the market in 2006 – millions of unsold homes, falling prices, late mortgage payments.” Really, in 2006? Home prices continued to rise throughout 2007 and only peaked in early 2007.

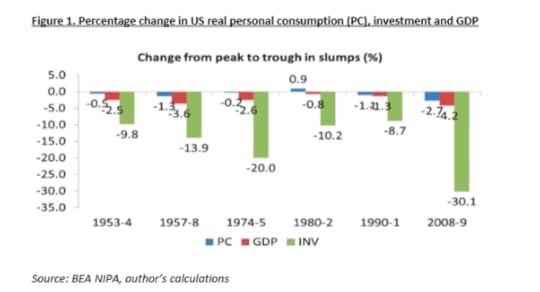

In the last six recessions since WW2, personal consumption fell less than GDP or investment on every occasion and did not even fall in 1980-2. Investment fell by 8-30% on every occasion.

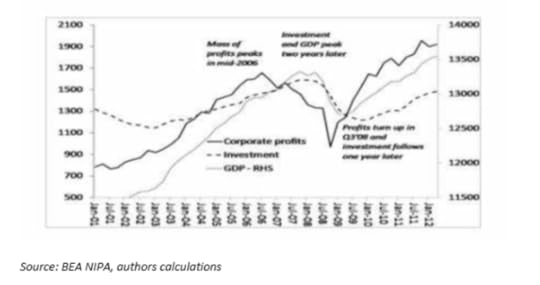

If the fall in GDP is to be an indicator of ‘overproduction’, then that did not happen in the Great Recession until well after the fall in profitability, the mass of profits and investment. And the recovery began first with a rise in the mass of profits and investment and only GDP after that.

You want any theoretical explanation of crises to be based on empirical data. “For example, if it is claimed that the crisis is caused by a long-term fall in the rate of profit, due to the increase in the organic composition of capital (OCC, constant capital/living labour ratio), the fall in the rate of profit and the progressive increase in the OCC must be evident.”

Well, there is a wealth of evidence by Marxist economists to show that. What surprised me is that you cite only two studies, Weisskopf from 1980 (!) and Brenner from 1996. And then there is Jose Tapia’s excellent paper from 2017 – which shows a clear connection between profits, investment and crises, with the causal direction from profits to investment to GDP.

Instead, I can cite a host of empirical work showing the movement in the rate of profit in the US and in many other countries that support Marx’s law, both in the tendency for the rate of profit to fall and also its connection with investment and crises of production. You do not reference the works by Mandel, Shaikh, Tsoulfidis, and others (including me) that have theoretically and empirically substantiated this theory.

Running the risk of neglecting some important works, I mention those of Duménil and Lévy (1993, 2002), Basu and Manolakos (2010), Paitaridis and Tsoulfidis (2012), Roberts (2016), Tsoulfidis and Paitaridis (2019), M. Li (2020) for the USA; Webber and Rigby (1986) for Canada; Reati (1986b), Cockshott et al. (1995), Li (2020), Alexiou (2022) for the UK; Reati (1989) for France; Reati (1986b), Tutan (2008) for W. Germany; Edvinsson (2010) for Sweden; Lianos (1992), Maniatis (2005, 2012), Maniatis and Passas (2013), Tsoulfidis and Tsaliki (2014, 2019) for Greece; Izquierdo (2007) for Spain; Mariña and Moseley (2000) for Mexico; Yu and Feng (2007), M. Li (2020) for China; Li M. (2020) for Japan; Jeong (2017), Jeong and Jeong (2020) for S. Korea; Maito (2014), M. Li (2020), Roberts (2020) for the world economy. And there is Trofimov (2020). Sergio Camara (Mexico,) Peter Jones (Australia), Themis Kalogerakos (on the US) and Murray Smith on Canada and the US. And just this year we have a new book by Mejorado and Roman on profitability and the US economy (which I shall review shortly).

Yes, the rate of profit can fall and the mass of profit can still be rising, as it was in 2006 just before the Great Recession. But eventually that situation cannot last. The answer to your question on why a small fall in the ROP from 11% to 10% might or might not trigger a crisis depends on the change in the mass of profit. You say, why would capitalists stop investing if they could even make a larger mass of profit even if the profit rate falls? The answer is that they would not, but eventually the mass will fall if the rate keeps falling. This was main argument of Henryk Grossman, rather than whether the mass of profit was insufficient for the capitalist to consume and invest at the same time.

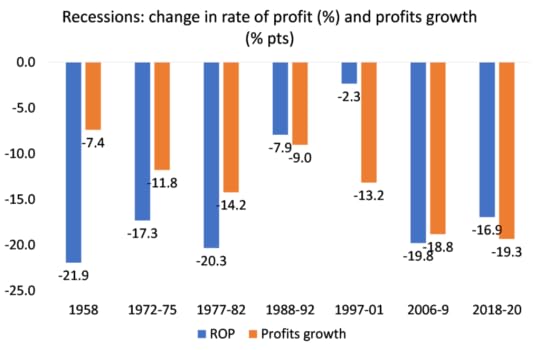

You say: “If the cause of cyclical crises is in the LTGT, there should be empirical evidence of a progressive fall in the profit rate due to an increase in the COC in the years, or in the decade, prior to the outbreak of the crisis. But this is not observed in the crises that occurred in the last 100 years.” You cite the out of date and inadequate work of Brenner for your argument that the ROP does not fall before crises. But there is much better evidence from many later sources (as cited above). I cite just one more: Carchedi in our edited book World in Crisis p46. I could also cite the very latest evidence provided in that new book by Mejarado and Roman (as I say, to be reviewed by me shortly). And here is graph from my own work. The rate of profit falls and so does the mass of profit in the period before slumps in the US.

You say that between 1920 and 1929, in the US, there is no clear tendency for the profit rate to fall that could explain the crisis of 1929-1933. But there is. See my book, The Long Depression pp 52-54, with graphs showing that the ROP in the US started falling as early as 1924. And see also: https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2021/04/18/the-roaring-twenties-repeated/

You say that “If we consider the crisis of 2007-2009, the profit rate had an upward movement from 1983 to 2006. There is no way to fit these data into the explanation of these crises by a gradual fall in the profit rate.” Yes there is: actually the US ROP in 2006 was lower than in 1997. Here is the very latest calculation of the US rate of profit in the non-financial sector from the excellent new Basu-Wasner database.

Indeed, before every major recession in post-war US, the ROP started falling in advance – as in my graph above.

You say that “As for the crises that occurred between 1825 and 1913, although there are no statistics on the long-term evolution of the profit rate, some of the major references in historical studies of the cycle, such as Lescure (1938) and Mitchell (1941), do not establish a connection between the crises and an eventual long-term fall in the profit rate.” Again, this is not correct. See the ROP series provided by the Bank of England and developed in my work on the UK rate of profit in the book already cited, World in Crisis, p183 onwards.

You say “it is difficult to explain the cyclical weakening of investment by the LTDTG.” Well, I think the above discussion on the relation between the rate of profit, the mass of profit and investment shows that not to be correct. And Tapia, in his paper of 2017 that you cite and in his subsequent papers, shows the clear causal connection between profits leading to investment. Again, Tapia’s updated paper is available in our book, World in Crisis, p78 onwards. Your alternative ‘possible sequence’ merely shows that as the rate of profit falls, capitalists will continue to accumulate and produce more and so increase the mass of profit to compensate. But that cannot last, and when the ROP falls to the point where the mass of profit starts to decline then a cyclical crisis emerges.

As you say, Marx argues that the decline in the rate of profit “necessarily provokes a competitive struggle” (p. 329, vol. 3) and not vice versa. So the position of Smith and Brenner that it is the competitive struggle that lowers profitability is not Marx’s and is also empirically incorrect. It is the falling rate of profit that provokes the competitive struggle and eventually provokes a slump in investment and production. And the falling rate of profit is not caused by a competitive ‘squeeze’ or rising wages, but by the rising organic composition of capital that outstrips the counteracting factors like the rise in the rate of surplus value. That is Marx’s law.

The LTRPF is not a law of stagnation (as you argue) but a law that explains cyclical crises. According to Marx, this law is not in and of itself capable of generating crises. In fact, the fall in the rate of profit can be slow enough and still the economy can keep expanding for many years. What the analysis requires is a cause for the crises from the ‘possibility’ of crises to pass to the ‘actuality’ theory of crises. Such a cause is offered by Marx in the trajectory of the mass of realized surplus value (profits); as the rate of profit declines, there is a point at which the mass or real net profits stagnate and thereafter even falls. This is what can be called ‘Marx’s moment’ or the point of ‘over-accumulation’ (see Shaikh, 1992; Tsoulfidis, 2006). At this tipping point, the capitalists abstain from investment and the system spirals down into a crisis.

You reject this view on the grounds that this absolute overaccumulation is only a “theoretical possibility” and would only happen because of a rise in wages squeezing profits. And you add that “we do not see that a general theory of capitalist crises can be derived from this hypothetical case. Nor do we know that such an “absolute overproduction” of capital has occurred in any country.” Well, I don’t think Marx saw absolute over accumulation as just a theoretical possibility or a hypothetical case, but as the logical consequence of his law in relation to crises. And again there is plenty of evidence (as above) that absolute over accumulation, as indicated by a fall in the mass of profit before crises, happens.

You say that your “position is that the tendency of capitalism to overproduction is logically prior to the question of whether the rate of profit tends to fall.” In my view, Marx says the opposite with a clear logical sequence to explain that and, since Marx, many Marxist economists have provided a wealth of empirical evidence to back Marx’s law as the underlying cause of regular and recurring crises in capitalism.

And finally, we get to your true position – namely a complete denial of what Marx wrote in Chapters 13 to 15 of Volume 3: “explanations of cyclical crises due to the increase in costs (wages, raw materials, interest rates) can also be stated without the need to refer to any long-term law of variation in the profit rate.” If that were correct, I assume you would remove those chapters from Volume 3, perhaps also because Engels distorted them to justify the law – this is the charge of Heinrich and other New Reading revisionists. You have previously reduced Marx’s law to one of a stagnation rather than a crisis theory and then you now go on to accept the neo-Ricardian Okishio theorem that refutes of the very logic of Marx’s law completely. You appear to ignore the refutations of Okishio by many Marxist economists since Okishio presented it (including Okishio himself in stepping back from his original arguments).

You say that “It is not clear why the rate of profit will fall in the long run with increasing productivity. “ Gosh! That is the very basis of the law that derives from Marx’s general law of accumulation in Volume One that capitalists invest more technology over labour to boost productivity and gain advantage over rivals; to Volume 3 where he shows that in doing so the rate of profit tends to fall and comes into contradiction with the rise in productivity. It is the basic contradiction of capitalist accumulation, denied by the mainstream, by Keynesians, by Piketty et al – and now by you?

You say “the value of the commodity that makes up the constant capital will fall in proportion to the increase in productivity, and the rate of profit will not fall. This is a key problem in the law formulated by Marx.” Yes, one of the counteracting factors would be the cheapening of constant capital through increased productivity. But that counteracting factor cannot overcome the law eventually. You rely on Okishio’s ‘complex goods’ to argue this. But the rise in constant capital over variable capital (within the value of the commodity) and in price terms is a self-evident feature of modern capitalist growth and empirically verified in many places and by many scholars. You have to admit that and you do: “Of course, this criticism does not deny that, in the long term, there is an increase in constant capital per worker due to the development of productive forces.” And yet you try to deny it.

You finish with a musing about whether the LTRPF might instead be a secular theory showing the ‘ultimate limits’ to the capitalist mode of production. Well, the LTRPF as a cyclical crisis or ‘ultimate end of capitalism’ theory is not necessarily contradictory. Yes, there is no ‘permanent crisis’, but also the long-term decline in the ROP shows that capitalism has a limited economic life – indeed it is increasingly past its sell-by date.”

Here is Rolando’s reply to me as published in Sin Permiso.

Dear Michael:

You write: “First, you claim that Marx never explained cyclical crises with his law of profitability. You back this up by saying that “when he wrote about the 1847 crisis he did not mention the law. Well, that is not surprising since he had not developed the law by then. But you go on to claim that “neither did he do so in the passages referring to the crises of 1866 and 1873. And in chapter 17 of volume II of Theories of Surplus Value, devoted to capitalist crises, he made no reference to the LTGT.”

First question : Marx mentions the 1847 crisis again in several passages in the drafts of Capital, when he had already elaborated the LTDTG. It is a fact that he does not explain the 1847 crisis by the tendency law of profit.

Second: In Chapter 17 of Volume II of Theories of Surplus Value, Marx does not even mention the LTDGT. This is despite the fact that the entire chapter is primarily devoted to explaining why the capitalist system tends towards crises of overproduction. To be more precise, if Marx had explained the crises of overproduction (of which the one in 1847 is an example) on the basis of the LTDGT, he would have had to show that, within a period of approximately 10 years, the organic composition of capital should have increased so much that, despite the increase in relative surplus value (due to the increase in productivity) and the relative cheapening of constant capital (for the same reason), the rate of profit would have fallen. With the addition that this would not have been enough, because in addition to demonstrating the fall in the rate of profit in the ten-year cycle due to the LTGT, he would have had to show why this fall would have caused the crisis. And for this to be a general explanation of the crises he witnessed, the same phenomenon should have occurred, every 10 years, in the crises of 1836, 1847, 1857, 1866, 1873. But this did not happen.

Third: I do not understand why no attention is paid to Anti-Dühring. Marx undoubtedly knew this text. He never questioned it. He never presented an alternative based on the LTDTG to Engels’ explanation of the crises of the 19th century.

Fourthly, I have quoted at length from passages and passages in the private correspondence of Marx and Engels on the crises of overproduction. In none of these exchanges do I find that they explain the crises of their time due to the LTDTG.

Fifth: I find the argument “you are not right because what you say was said by, for example, Hilferding” inappropriate. I will develop this topic in another post.

Sixth: I insist on the need to differentiate between crises of underconsumption and crises of overproduction. Marx and Engels were critical of the underconsumptionist approach (typical of bourgeois reformism) to overproduction.

Hug. Rolando

And Rolando replies to a recent comment on his blog as follows:

“I still think that cyclical crises are not explained by the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. For this reason Marx and Engels did not explain the crises of 1836, 1847, 1857, 1866, 1873, 1882-4, 1890, by that law. It is striking that Roberts, and others who share his position, do not say why Marx and Engels did not explain those crises by the LTGT:

In the same way, the 1929-1933 crisis in the USA, or 2007-2009 (as I show in the note) are not explained by the LTGT.

I do think that the fundamental motor of capitalist accumulation is the valorization of capital. It is nonsense to maintain that, if the LTDGT does not explain the crises, the rate of profit (i.e. the valorization of capital) does not play a role in the dynamics of capitalist accumulation and crises.”

My comment:

I think we have answered Rolando’s argument that Marx and Engels did not refer to the law of profitability in explaining those crises (see the quotes of profitability and crises mentioned n my reply above). And actually there is good evidence that the crises of 1929 and 2008 were preceded by falls in the rate and mass of profit which I also presented in my reply above – Rolando ignores this evidence.

But let’s just say that Rolando is right and Marx did not reckon his law of profitability provided any cause for periodic crises and it was all down to ‘overproduction’ of supply exceeding demand in the market. Then I would have to say that Marx was wrong. He should have stuck to the logic of his law of profitability as it provides the most compelling case for the cause of crises, backed by the best evidence compared to ‘overproduction’, which excludes the role of profitability in crises in an economy driven by the profit motive!

As Rolando says, it is nonsense to suggest that profitability does not play a role in changes in investment or accumulation. But he then argues that it does not play a role in causing slumps. I argue along with many others that movements in profitability provide the underlying or ultimate cause of periodic crises and provide both theoretical and empirical evidence to support that. The overproduction theory does not explain periodic crises and has no empirical support.

December 10, 2024

Milei’s ‘creative destruction’

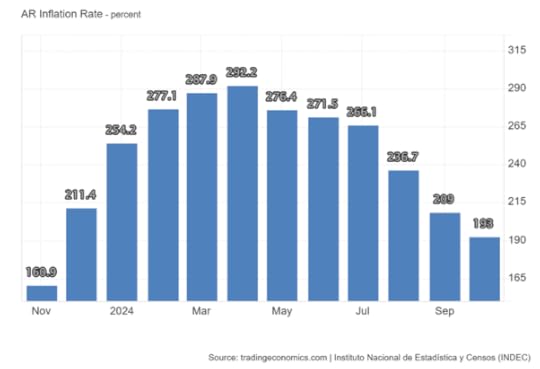

It’s one year since the self proclaimed ‘anarcho-capitalist’ Javier Milei became President of Argentina. He took power in a country where annual inflation was running at 160%, over four of every 10 people were below the poverty line and the trade deficit stood at $43 billion. In addition, there was a daunting $45 billion debt owed to the International Monetary Fund, with $10.6 billion due to be paid to the multilateral lender and private creditors.

The previous Peronist administration had failed miserably to deliver on economic expansion, a stable currency and low inflation. And it also failed to deliver on ending poverty and reducing inequality. Argentina’s official poverty rate rose to 40% in the first half of 2023. According to the World Inequality Database, the top 1% of Argentines then had 26% of all net personal wealth, the top 10% had 59%, while the bottom 50% had just 5%! In incomes, the top 1% had 15%, the top 10%, 47% and the bottom 50% just 14%.

Milei’s plan was clear (at least in his own mind). He would dismantle Argentina’s state sector, ‘free up’ markets from regulation for big business and foreign investors to make profits; devalue the currency with the eventual aim of complete dollarisation and then rely on unrestricted capitalism to solve the perpetual crisis. This is a living experiment in free market policies over reformist, semi-interventionist Keynesianism adopted by previous administrations.

On taking power, Milei implemented a series of austerity measures, including slashing energy and transportation subsidies, laying off tens of thousands of government workers, freezing public infrastructure projects and imposing wage and pension freezes below inflation.

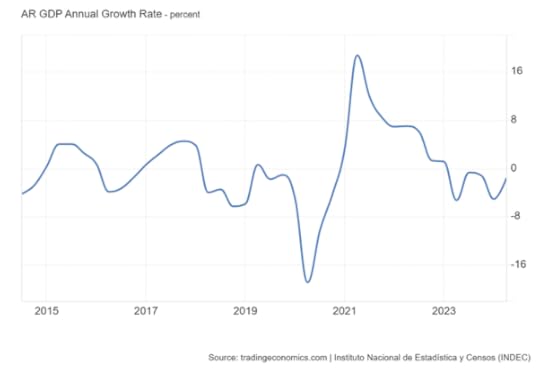

It has been brutal. The economy has gone into a deep slump. The IMF forecasts a contraction of 3.5% for 2024. That’s the biggest contraction in any of the G20 top economies and only surpassed by gangster-ridden Haiti and civil war-smashed South Sudan.

Milei aims to end hyperinflation in the economy through a deliberately engineered slump in production and consumption that destroys costs for capital. By cutting public sector spending and jobs and subsidies for the poor, he aims to increase the rate of exploitation for business and eventually boost the profitability of Argentine capital in order to inspire investment.

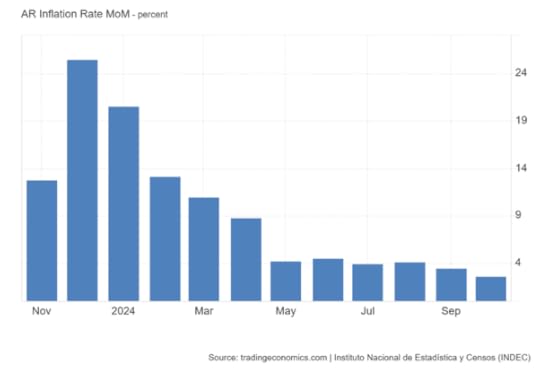

After one year, monthly inflation has dropped sharply as most Argentines have been forced to cut back on spending.

However, prices are still nearly over 190% higher than a year ago, when Milei took office.

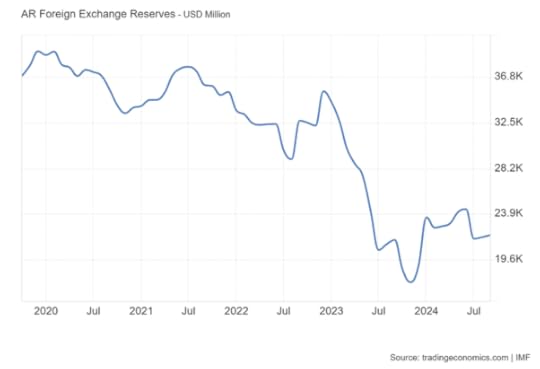

Slowing inflation has strengthened the Argentine peso and reduced borrowing costs. And with a tax amnesty, Milei has lured rich Argentines to declare their hidden US dollar savings (hidden in offshore bank accounts and under mattresses). That brought $19 billion into Argentina’s banks, boosting foreign exchange reserves.

Milei wants to free up the peso from controls but if he does that now, the peso, being hugely overvalued, would plummet, making it difficult to meet repayments to the IMF. Luckily, the much-hated IMF is very pleased with Milei’s policies. The IMF commented that they have “resulted in faster-than-anticipated progress in restoring macroeconomic stability and bringing the program firmly back on track,” , thanking Argentine authorities for “the decisive implementation of their stabilization plan.” So the rich are not having to pay tax and Milei’s austerity measures have been greeted with enthusiasm by the IMF and Argentine big business.

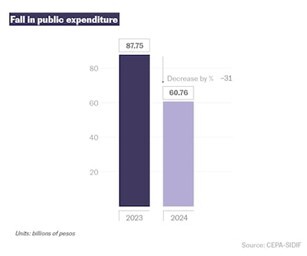

Public spending has been reduced by 30% year-over-year in real terms (adjusted for inflation), according to calculations by the Center for Argentine Political Economy (CEPA) and the Association for the Budget and Public Financial Management (ASAP).

Milei has closed 13 ministries and fired some 30,000 public employees, 10% of the federal workforce. He has also frozen public works and reduced the funds that are allocated to education, health, scientific research and pensions. The budgetary cuts have been especially hard on infrastructure (-74%), education (-52%), social development (-60%), healthcare (-28%) and federal assistance to the provinces (-68%).

The Argentine Chamber of Construction (CAC) estimates that the state now owes contractors about 400 billion pesos (or $400 million) and that 200,000 workers have been fired in the construction sector since the start of the Milei administration. State pensions have been frozen. As it is, a pensioner in the lowest income bracket currently receives the equivalent of $320 a month, or barely a third of the $900 that a household requires to survive.

According to the National Interuniversity Council, 70% of teaching and non-teaching salaries fall below the poverty line. Milei has now eliminated the National Fund for Teacher Incentives, which subsidised these very low salaries of teachers throughout the country and represented almost 80% of the transfers from the federal government to the provinces for educational purposes. In addition to suspending infrastructure upgrades to schools, he also cut student scholarship programs by 69%. University budgets were frozen and so many campuses were left without resources to pay for gas heating and electricity and the university system declared a state of emergency.

Milei has cut the salaries of researchers and support staff at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), the main organization dedicated to science and technology in the country. He also drastically reduced the number of doctoral and postdoctoral scholarships, dismissed 15% of the administrative staff of CONICET, froze the budget for the National Agency for the Promotion of Research and ceased projects in key institutions, such as the National Institute of Industrial Technology (INTI) and the National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA). As a result, there was a 30% drop in applications to research and scientific positions in the country. In a public letter addressed to Milei, 68 Nobel Prize winners warned that “the Argentine science and technology system is approaching a dangerous precipice.”

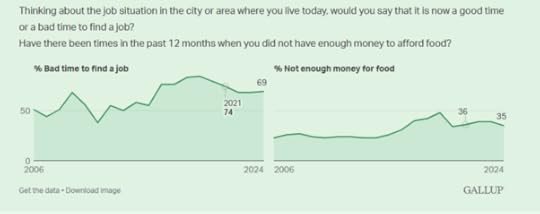

Poverty levels have worsened significantly. Argentina’s poverty rate has jumped from almost 42% to 53%, an extra 3.4m Argentines. Two-thirds of Argentine children under the age of 14 are living in poverty. Milei has eliminated subsidies that were managed through social organizations. Among the aid interrupted is the distribution of food to soup kitchens, which serve children and entire families. Employment programs channeled through worker cooperatives have also been cancelled. Argentines incresingly cannot get jobs and cannot afford even enough to feed the family properly.

Subsidies on electricity, gas, water and public transit have been cut. In December 2023, a middle-class family spent about 30,105 pesos (about $30) a month on electricity, gas, water and public transportation. But in September 2024, spending had risen to 141,543 pesos ($142).

These massive hits to the living standards of average Argentines, along with continuing rises in inflation have led to a collapse in consumption. In the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (AMBA) a 12.9% year-on-year decline was recorded and -2.3% compared to April 2024. In the rest of the country, consumption fell 15.5%% yoy and 3.6% compared to April 2024.

There has been further increase in inequality. The top 10% of income earners now earn 23 times more than the poorest decile, compared to 19 times a year ago. The fall in income reached 33.5% year-on-year in real terms among the poorest decile, but only 20.2% among the richest. The gini inequality index has hit an all-time high of 0.47.

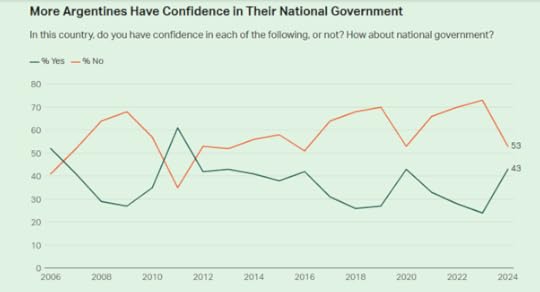

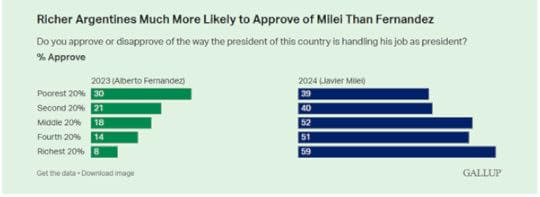

Despite this vicious attack on average living standards, Milei has maintained a sufficient degree of support. People are still hoping that he will end the chaos of inflation and then restore growth. His approval ratings have been stable.

Naturally, support for the Milei government mainly comes from rich Argentines, but even the poorest who are taking the bulk of the burden of his measures still show more support for him than for the previous Peronist administration.

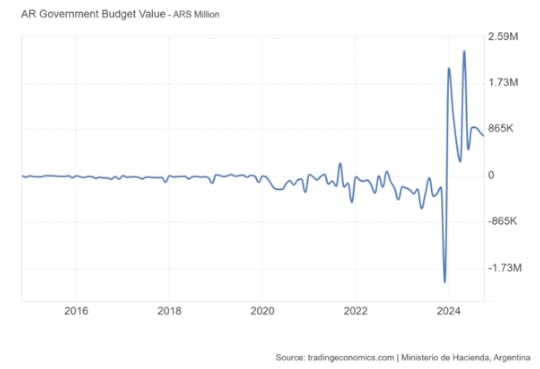

By aggressively cutting spending and chopping government ministries in half, Argentina has swung from a fiscal deficit of 2 trillion pesos (US$2 billion) at the end of last year to a surplus of 750bn pesos in October this year. This is the first fiscal surplus in 16 years.

Will Miele’s policies work? It certainly provides a living experiment in the success of ‘free market’ policies over Keynesian macro management in a country. But Argentina is a weak capitalist economy dominated by imperialism. It had been running a huge trade deficit. Milei’s devaluation of the peso did enable exports to recover over the last year (now up 30%), while austerity domestically crushed imports. The tax exemptions for the rich have led a small net influx of capital after massive outflows in the last year of Peronist government.

So foreign exchange reserves have improved slightly, but are still way short of being sufficient to meet debt repayments ahead, mainly to the IMF. The country faces large external debt payments of approximately US$9 billion in 2025. But maybe the IMF will be kind.

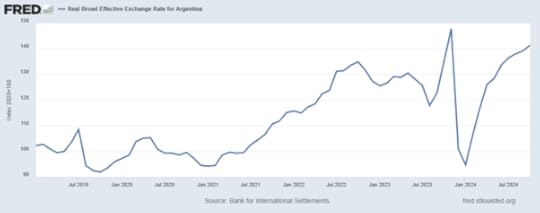

The immediate problem is that the peso is still well overvalued even though the US dollar is strong and needs to be devalued by at least another 30% to make Argentine exports competitive. But that would only re-accelerate inflation.

Milei’s anarcho-capitalist plans are really a form of ‘creative destruction’,, the term that Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian economist of the 1930s, used to explain how slumps are necessary under capitalism in order to create the conditions for new expansion. It is necessary to ‘cleanse’ the system of unnecessary spending, unproductive workers and weak firms, making the economy ‘leaner and fitter’.

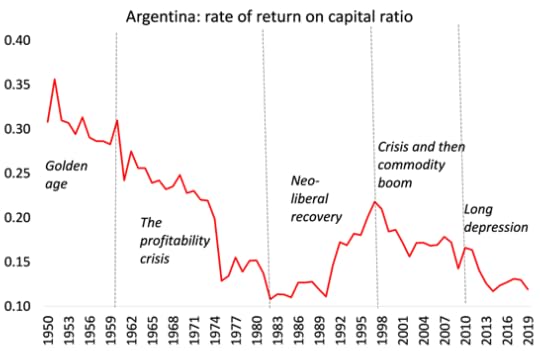

So far, in ‘creative destruction’, Milei has only achieved destruction. But, as Marx argued, the creative bit requires a sharp rise in the profitability of capital that will lead to a burst of investment and thus employment and incomes. Is that really likely, given global stagnation and how far Argentina’s capitalist sector has sunk? Indeed, will a deep recession in Argentina be so deep that the economy will sink into a depression for the rest of the decade?

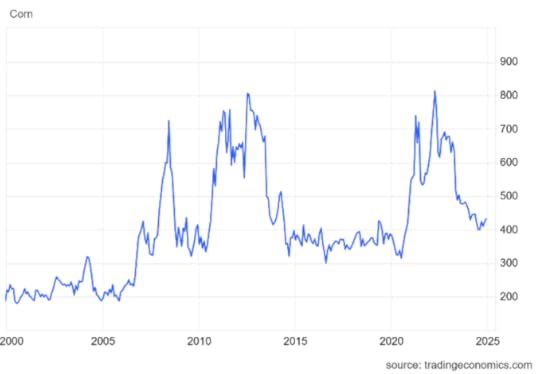

Argentina could possibly get out of its mess if there were a boom in commodity prices, as there was in the early 2000s. Argentina is the world’s largest exporter of soya bean oil and meal, the number two exporter of corn and the third biggest exporter of soya beans. However, for now, soybean and corn prices are not very buoyant.

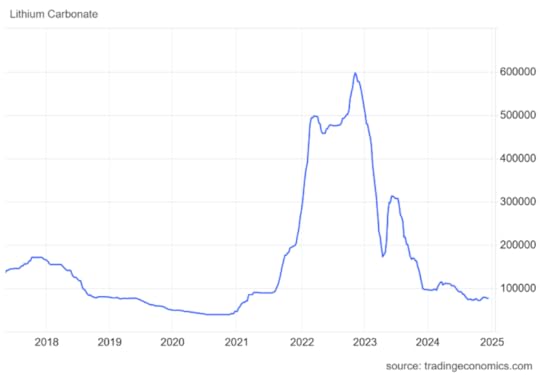

Argentina has the world’s third largest lithium reserves, making it a key player in the global energy transition . However, lithium prices have dived recently.

Argentina also has considerable reserves of shale gas. The Vaca Muerta oil field is one of the world’s largest unconventional hydrocarbon resources, with an estimated 16 billion barrels of oil and 308 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, but so far largely unexploited.

Exports are key and that means an even greater devaluation of the peso that could re-accelerate inflation, unless even more austerity is applied domestically. And the big worry is that incoming President Trump says he aims to raise tariffs on all US imports by at least 20% and that will hit Argentina. No wonder Milei has spent time cosying up to Trump at Mar-a-Largo.

December 7, 2024

The chaos theory of profitability refuted

Back to theory in this post.

The law of the tendential fall of the average rate of profit (LTRPF) lies at the very heart of Marxian economics. It is essential to explain all aspects of the capitalist economy, from economic crises to imperialism and the theft of international value inherent in imperialism. In short, it is essential for labour’s indictment of, and struggle, against capitalism.

It is thus not by chance that it has been the object of sustained attacks since the publication of the third volume of Capital.

One such critique that has gained some traction in Marxist circles is that by Marxists Emmanuel Farjoun and Moshe Machover in their book written in 1983 (and republished by Verso in 2020) called Laws of Chaos. They argue that Marx’s transformation of the values of commodities by the equalisation of individual rates of surplus value (profit) into prices of production based an average rate of profit for all capitals is indeterminate.

Supposedly, in Marx’s Capital 1, the price of a commodity is determined by the value contained in it (individual value), while in Capital 3 it is determined by its social value, the value it has after individual profit rates are modified by their equalization into an average. Thus values are converted into prices of production.

Like many other critics, Farjoun and Machover reckon that this conversion is inconsistent because prices of production would then not be uniquely determined by a quantity of value in labour time. Farjoun and Machover argue that Marx was wrong and Marxist must recognise that “there is no rigid relation between labour content and price. The ratio between price and labour content is a random variable, which can assume, for a given individual transaction, any positive numerical value whatsoever”. What Marx and the rest of us apparently need to recognise is that individual profit rates are not determined by any definite amount of value measured in labour time, but are ‘chaotic’ ie. ruled by the laws of probability. So there is no average rate of profit, but only a ‘scatter’ of profit rates.

In the paper attached, Determination and probability in Marx’s transformation ‘problem‘, my colleague Guglielmo Carchedi refutes this ‘chaotic’ theory of the relation between the value of commodities and prices of production. A scatter as a whole always has an average. It is an essential feature of any group of numbers. It arises necessarily from it and together with it. It follows that the average does not pre-exist the scatter. Each time a scatter arises or changes, the average arises or changes too. And a decreasing sequence of averages measures a decreasing average quantity of surplus value generated relative to the capital invested within a given time frame ie an average rate of profit. It is perfectly determinable and not ‘chaotic’.

Why does any of this matter? Well, if an average rate of profit on capital invested cannot be determined and instead is either non-existent or merely random, then this drives a hole through Marx’s LTRPF and in turn, any compelling explanation of crises in capitalist production. However, in the attached paper, Carchedi shows that the ‘probabilistic approach’ is wrong and indeed a step backwards in Marxist theory.

December 4, 2024

US economy: an exceptional boom or a bubble to burst?

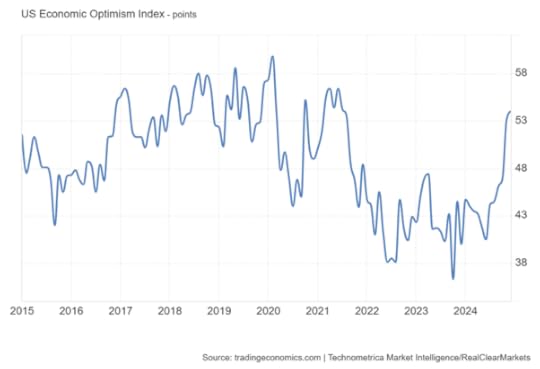

Recently, there has been a spate of articles and commentary about ‘US exceptionalism’, namely that the US economy is bounding forward in terms of economic growth, hi-tech investment and productivity, leaving the rest of the world behind. And so no wonder that the US dollar is riding high and its stock markets are booming. This success is put down to less regulation, an entrepreneurial spirit, lower taxes on investment etc – in other words, none of this government interference that Europe, Japan and other advanced capitalist economies suffer. Optimism reigns about America’s success, even it seems among the wider public and not just in stock markets. The RealClearMarkets/TIPP Economic Optimism Index in the US has risen to its highest since August 2021, if still below the pre-pandemic years.

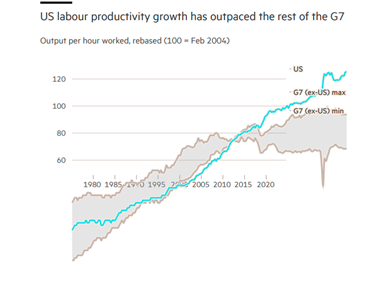

But this story of boom is misleading. Yes, the US economy is doing better than Europe or Japan. But is it doing better historically? Take the recent piece in the UK’s Financial Times lauding the US performance relative to Europe entitled “why America’s economy is soaring ahead of its rivals”. The authors go on: “the US is growing so much faster than any other advanced economy. Its GDP has expanded by 11.4 per cent since the end of 2019 and in its latest forecast, the IMF predicted US growth at 2.8 per cent this year.” And: “its growth record is rooted in faster productivity growth — a more enduring driver of economic performance….US labour productivity has grown by 30 per cent since the 2008-09 financial crisis, more than three times the pace in the Eurozone and the UK. That productivity gap, visible for a decade, is reshaping the hierarchy of the global economy.”

And more: “productivity growth the US is rapidly outstripping almost all advanced economies, many of which are caught in a spiral of low growth, weakening living standards, strained public finances and impaired geopolitical influence.”

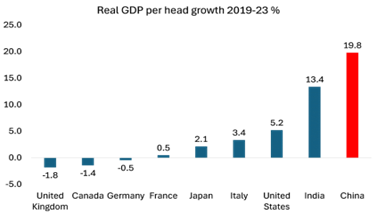

The problem with this narrative is that it is all relative. Note the title of article: why America’s economy is soaring – ahead of its rivals. The US economy is soaring, wait… but only ahead of its rivals. Yes, compared to Europe and the rest of the advanced capitalist economies (of course, not compared to China or India), the US is doing much better. But that’s because Europe, Japan, Canada are stagnating and even in outright recession. In historic terms, the US economy is doing worse than in the 2010s and worse again compared to the 2000s.

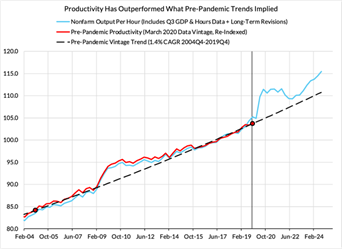

Take productivity growth. Here is the FT graph that suggests US exceptionalism.

But if you look closely at the trajectory of the US productivity growth line, you can see that from about 2010, productivity growth in the US has been slowing. Its relative outperformance is entirely due the collapse of growth in the rest of the G7. As the FT article puts it: “Data from the Conference Board shows that, in the past few years, labour productivity has dropped relative to that of the US in most advanced economies.” Yes, relative to the US, but labour productivity growth in the US is slowing down too, if by not so much.

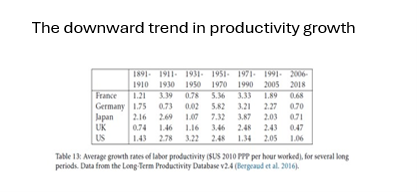

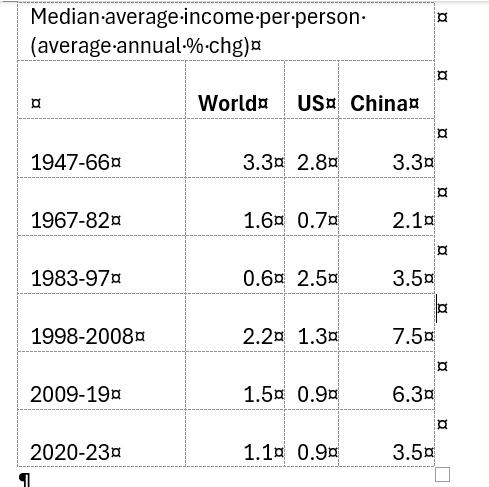

Indeed, if we go way back on the history of productivity growth, the real story is that capitalist economies are increasingly failing to expand the productive forces and raise the productivity of labour. You can see that from the table below. US productivity growth from 2006-18 is much better than other major capitalist economies, but the rate is half what it was in the 1990s.

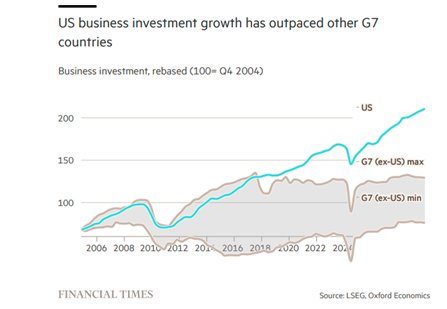

The same narrative applies to productive business investment. The FT shows a graph where US business investent growth is outpacing other economies. But again, note that the trajectory of US investment growth is also slowing: compare the current growth rate with that of the 2010s and even more with the 2000s. US business investment is slowing over the long term, while in the rest of the G7, business investment is stagnating.

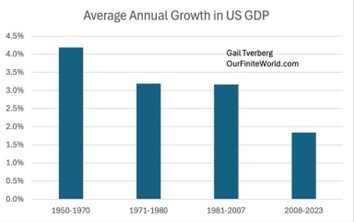

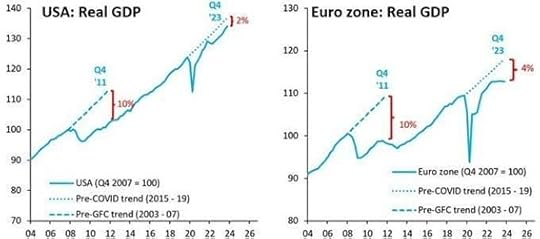

Let’s take another graph that shows the historic trend of economic growth in the US.

Average annual real GDP growth in the US has declined from the 4% rate in the post-war ‘Golden Age’ to 3% a year before the Great Recession and under 2% in the period since then, in what I have called the Long Depression. And current consensus forecasts for US growth in 2025 are just 1.9%. But that would still be the fastest of any G7 economy.

Moreover, we are measuring real GDP growth here. In recent years, much of the faster growth in the US has been due to immigration, boosting the labour force and overall output. Growth in output per person has been much less, if still better than the rest of the G7 after the pandemic.

The graph below of trend growth for the US versus Europe shows the story better. US trend growth rates have been slipping in the 21st century; while Europe’s have been diving.

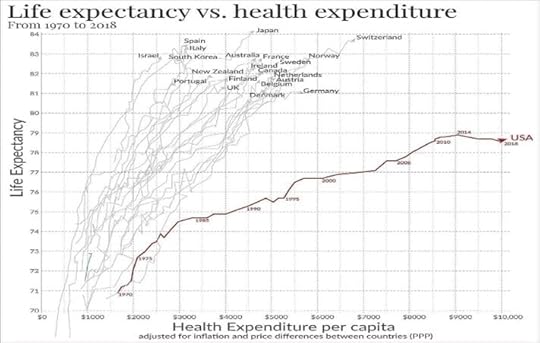

Moreover, the relatively better performance of the US capitalist economy over the other advanced economies does not indicate whether average Americans are doing better. As the FT article admits: “For all its economic power, the US has the largest income inequality in the G7, coupled with the lowest life expectancy and the highest housing costs, according to the OECD. Market competition is limited and millions of workers endure unstable employment conditions.” Hardly a recruitment poster for living in the US, even if stock market investors don’t care about that.

And if we are talking above relative growth in average income per person in the US, look at this table that I have compiled from the World Inequality Database. Average earners in the US are seeing less and less progress (even relatively), particularly in the 21st century.

Nevertheless, the argument goes that a US productivity boom is now under way, driven by the introduction of AI and other technology investment that the rest of the capitalist world (and China) cannot match. As Nathan Sheets, chief economist at Citigroup, says that, despite these efforts and China’s push to become an AI superpower, the US is the “place where AI is happening, and will continue to be the place where AI happens”. And there are signs that US productivity growth may be picking up – although note that the graph below is an estimate.

Maybe so, but the huge investment spending in AI has yet to be see real results across the whole economy that could reduce significantly jobs and so sustain a a large rise in productivity per worker. That could take decades.

Indeed, there is plenty of evidence that the AI boom could really just be a bubble – a huge rise in what Marx called fictitious capital, ie investment in the stocks of AI-related companies and the US dollar that is way out of line with the reality of AI-realised profits and productive investment.

In the FT again, Ruchir Sharma, chair of Rockefeller International called the US stock market boom “the mother of all bubbles”. Let me quote: “global investors are committing more capital to a single country than ever before in modern history. The US stock market now floats above the rest. Relative prices are the highest since data began over a century ago and relative valuations are at a peak since data began half a century ago. As a result, the US accounts for nearly 70 per cent of the leading global stock index, up from 30 per cent in the 1980s. And the dollar, by some measures, trades at a higher value than at any time since the developed world abandoned fixed exchange rates 50 years ago.”

But “Awe of “American exceptionalism” in markets has now gone too far….Talk of bubbles in tech or AI, or in investment strategies focused on growth and momentum, obscures the mother of all bubbles in US markets. Thoroughly dominating the mind space of global investors, America is over-owned, overvalued and overhyped to a degree never seen before. As with all bubbles, it is hard to know when this one will deflate, or what will trigger its decline.”

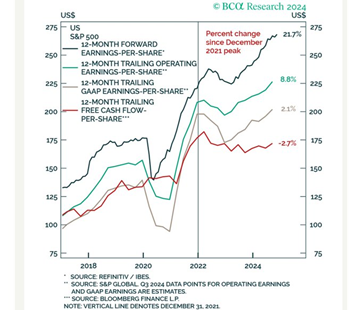

And this bubble is very narrowly supported. US stock market drives world markets and just seven stocks drive US stock market: the so-called Magnificent Seven. For the vast majority of US companies, those outside the burgeoning energy sector, social media and tech, things are not so great. S&P 500 free cash flow per share hasn’t grown at all in three years (see the red line below). Forecasts of profit growth are wildly out of line with what is being realised.

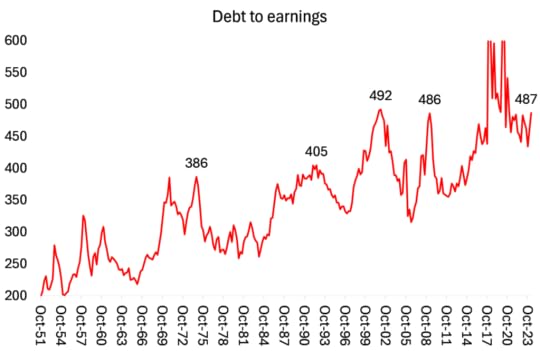

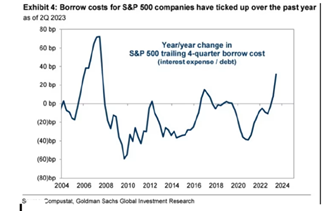

US corporate debt to earnings remains near all-time highs and interest costs on this debt have not fallen much since the US Fed decided to start cutting its policy rate.

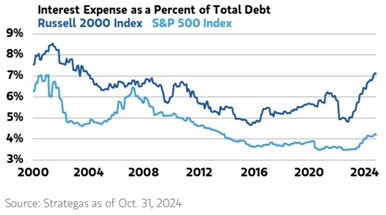

The difference in the average cost of debt for the smaller Russell 2000 companies and the big S&P 500 companies recently more than doubled to about 300 basis points. With intermediate and long-term interest rates still backing up, it is not obvious that relief will come soon.

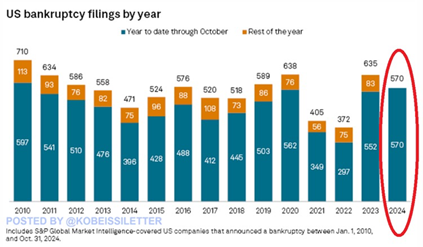

US corporate bankruptcies in 2024 have surpassed 2020 pandemic levels. Bankruptcies are surging as if the US economy was struggling.

In its recent Financial Stability Report, the Federal Reserve noted that “valuation pressures remained elevated. The ratio of equity prices to earnings moved up toward the high end of its historical range, and an estimate of the equity premium—the compensation for risk in equity markets—remained well below average.” It was concerned that “While balance sheets in the nonfinancial business and household sectors remained sound, a sharp downturn in economic activity would depress business earnings and household incomes and reduce the debt-servicing capacity of smaller, riskier businesses with already low ICrs as well as particularly financially stretched households.”

There is no bust yet in the stock markets. But if a bust comes, with many companies struggling and debt burden rising, a financial crash could well ricochet into the ‘real economy’. And spillover globally.

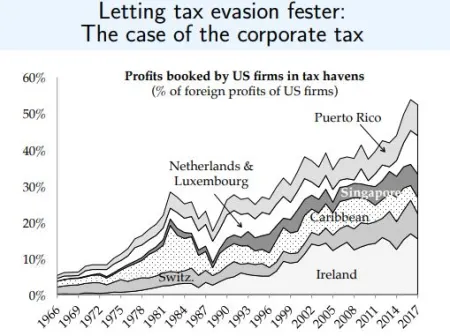

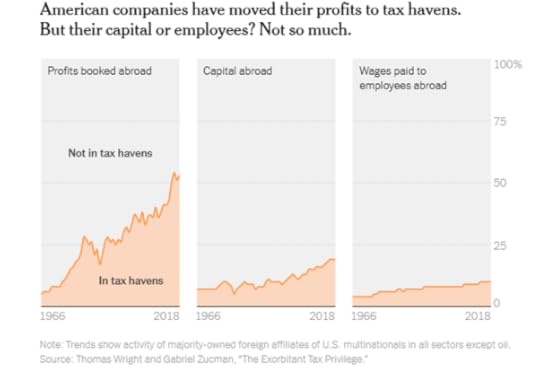

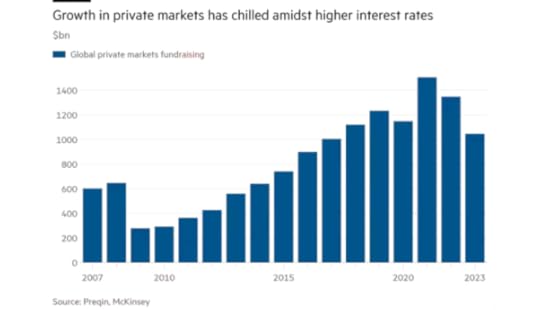

Productivity growth in the major economies has slowed across the board because productive investment growth dropped. And in capitalist economies, productive investment is driven by profitability. The neo-liberal attempt to raise profitability after the profitability crisis of the 1970s was only partially successful and came to an end as the new century began. The stagnation and ‘long depression’ of the 21st century is exhibited in rising private and public debt as governments and corporations try to overcome stagnant and low profitability by increasing borrowing.

That remains the Achilles heel of the US exceptionalism. The story of US exceptionalism is really a story of Europe’s collapse – and that’s another story.

November 29, 2024

Ireland election: its economic model under threat?

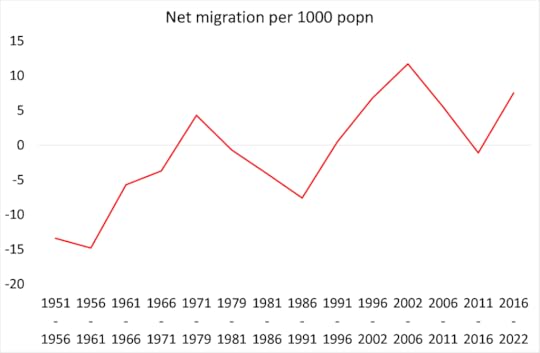

The Repubic of Ireland (this excludes the northern Ireland enclave which is still part of Britain) holds a general election today. Ireland has just 5m people and is part of the European Union and the Eurozone, contributing just 1% of EU27 and 3% of EU GDP.

The current government is a coalition of the two traditional pro-capitalist parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fail, with the Greens. This coalition has kept out of power the republican nationalist Sinn Fein that wants a referendum on a united Ireland and offers more radical economic measures. The current Taoiseach (Irish PM) is Simon Harris of Fine Gael, which is slightly behind in the opinion polls at 19% of the expected vote, while Fianna Fail and Sinn Fein are polling about 21% each.

In the 21st century, Ireland became a huge tax haven for high wealth individuals, hedge funds and above all, American multinationals. Ireland remains a leading location for US foreign direct investment (FDI). Some 970 American firms employ more than 210,000 people directly, with a further 168,000 jobs supported indirectly in the supply of products and services. These companies are also responsible for the bulk of corporation tax revenue. This has made Ireland an “outlier” in Europe with more than 25% of tax revenue in the Republic of Ireland coming from corporation tax compared an average figure of less than 10% across Europe.

In 2018, Facebook made $15 billion in profit in Ireland — the equivalent of about $10 million for each of its employees there. That same year, Bristol Myers Squibb recorded close to $5 billion in profit in the Emerald Isle, or roughly $7.5 million per employee., while employment in these companies for Irish workers has been relatively modest and confined to highly-educated or skilled Irish workers.

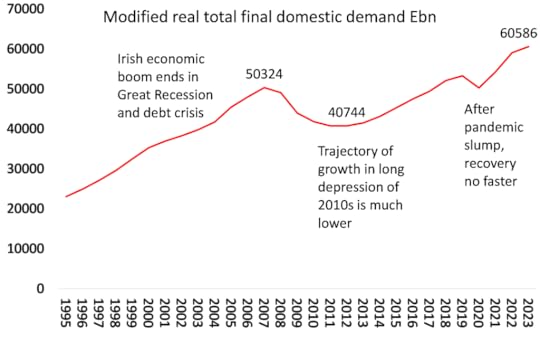

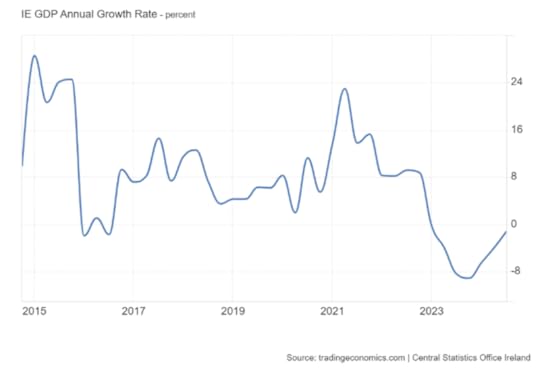

Ireland’s tax haven status, and in a ‘colonial’ relation to US corporates and investors, leads to misleading data on national output growth. While GDP data suggest a massive boom, if the profits of the American companies are stripped out, domestic growth is much less impressive. Indeed, the government has been forced use what it calls modified domestic demand (MDD) as a measure of real expansion for Ireland. MDD strips out American investment in imported intellectual property and aircraft leasing which does not touch the sides of the Irish economy.

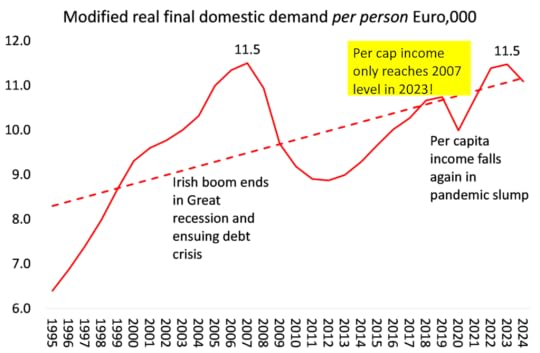

Instead of GDP as a measure, if you consider MDD, you find that Ireland’s economic growth has been much more modest and indeed is slowing. The trajectory of fast growth was halted by the Great Recession of 2008-9 and the subsequent recovery in the 2010s (the decade of the Long Depression in all the major economies) had a much lower growth rate. The pandemic slump then hit Ireland and again, as elsewhere, the growth rate has hardly resumed the trajectory of the 2010s.

This is even more clearly revealed when we consider MDD per person. Average per capita income (MDD) is currently no higher than at the peak of 2007, 17 years later!

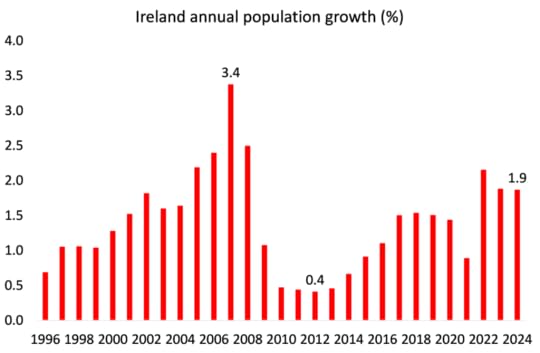

And that’s because much of the rise in output has been achieved by sharply increased immigration – an election issue now. After a century as a country of emigrants, Ireland’s population in 2024 is now estimated to be 5.38 million, rising by 98,700 people in the year to April 2024. This was the largest 12-month population increase in 16 years since 2008, when the population rose by 109,200. And there are 2.7m in employment, up one million since 2000.

The number of immigrants in the year to April 2024 is estimated to be 149,200 consisting of 30,000 returning Irish citizens, 27,000 other EU citizens, 5,400 UK citizens, and 86,800 other citizens including Ukrainians.

The population rise is increasingly concentrated in Dublin, Ireland’s capital, where the proportion of the population has risen from 28.1% of the total in 2018 to 28.5% in 2024 and now has 1.5m people.

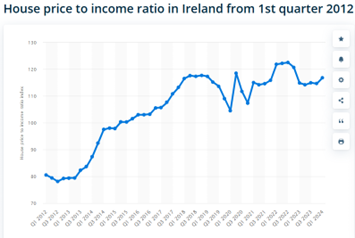

As a result, cheek to jowl with the modern American owned plants in the so-called Silicon Docks area of Dublin, there is an inner city which is one of the most deprived areas of Europe capitals. Homelessness in Ireland is at a record high – with the most recent figures showing 12,600 people were in emergency accommodation in June. The average cost of renting a one-bedroom property in Dublin is €1,800 (£1,550) a month. That places it third among major cities in Europe, just behind Geneva and London, in a study of more than 40 locations carried out by the EU statistics agency Eurostat.

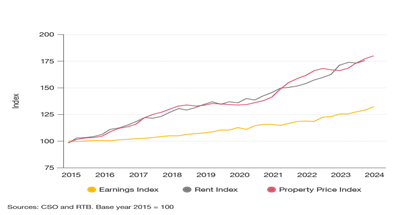

So the rising cost of living and lack of affordable housing are key election themes. While average hourly earnings increased by 25% between 2019 and 2024, the gap between earnings and housing costs has widened significantly and is forecast to continue to do so. The Central Bank of Ireland estimates that 52,000 homes will need to be built per year out to 2050. This is an increase of 20,000 units per annum relative to the 2023 figures. In the 12 months to July 2024, 12% of property purchases were by non-occupiers – that means buy-to-let owners seeking to make profits from renting.

Indeed, inequality of incomes in Ireland remains extreme, with top 10% of earners gaining more share of total income (from 30% in 1980 to 35% in 2018), while the share going to the bottom 50% has fallen to just 20%.

As usual, inequality of wealth (ie ownership of property and financial assets net of debt) is even worse. The top 1% of wealth holders in Ireland have 23% of all personal wealth and the top 10% have 66%, while the bottom 50% have no net share as they owe more than the own (-3.4%)!

Last year, Ireland’s economy slipped into recession on the back of a slump in the American multinationals’ exports (even the MDD measure showed only a 0.5% rise). That shows how dependent Ireland has become on US multinationals, with that sector contracting for the first time since 2013. Things look little better in 2024 as business investment drops.

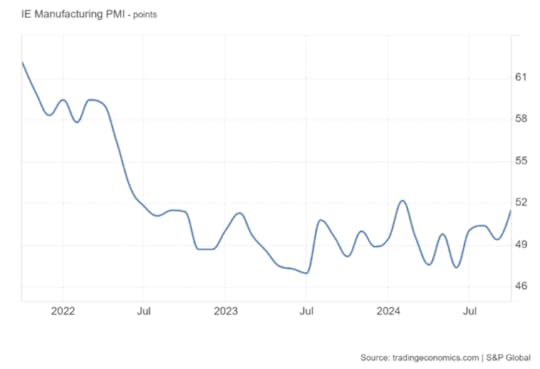

As elsewhere in Europe, Ireland’s manufacturing sector has been contracting (scoring below 50 on the PMI economic activity measure).

The Irish government was recently forced to tax multinationals like Apple more than they wanted, to meet EU tax regulations and they also had to raise their corporate tax rate to 15%. Ironically, as a result, the government is now flush with extra revenue (E14bn alone in back taxes from Apple). Tax revenues are set to create a surplus over government spending of E65bn by the end of this decade.

How will it be spent it, if at all? Suggestions include setting up a sovereign wealth fund to invest, along the lines of Norway’s and a fund for infrastructure. As PM Harris says: “There are clear areas where it would merit consideration around infrastructure, housing and other areas where there are constraints.”

Indeed! The problem is that Ireland’s private sector construction industry is totally inadequate to build more homes to meet any reasonable target to deal with the housing crisis. And of course, no state-owned housing corporation is being advocated with training for skilled construction workers.

And then there is Trump. He could be a serious threat to Ireland’s future attraction for American corporate investment with his talk of making America great again by getting US firms to operate at home. Trump plans to match the US corporation tax rate to Ireland’s now 15% and to slap tariffs on goods manufactured abroad in a bid to lure companies back home.

PM Harris has said the country could lose €10bn in corporate tax if just three US multinationals were repatriated to America under a hostile Donald Trump administration. Ten multinationals account for 60% of Ireland’s corporate tax receipts, with Microsoft, which books some global as well as EU revenues through Ireland, thought to be the single biggest contributor. MAGA could mean the end of Irish economic growth model.

November 24, 2024

COP-out 29

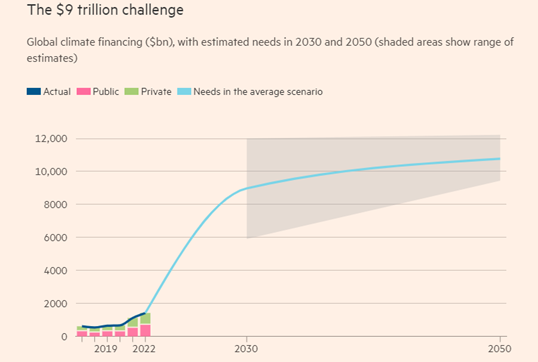

There was a tortuous and painful end to COP29, the international climate change conference held in oil-rich Baku, Azerbaijan. The main issue was how much would the rich countries hand over to the poor countries to pay for the measures to mitigate global warming and handle the damage caused by rising ‘greenhouse gas’ emissions. The finance target set was for more than $1.3trn a year by 2035. But the final deal was based on just $300bn in actual grants and low-interest loans from the developed world. The rest would have to come from private investors and perhaps levies on fossil fuels and frequent flyers – the details of which remained vague.

The offer from the ‘developed’ countries, funded from their national budgets and overseas aid, is supposed to form the inner core of a so-called ‘layered’ finance settlement, accompanied by a middle layer of new forms of finance such as new taxes on fossil fuels and high-carbon activities, carbon trading and ‘innovative’ forms of finance; and an outermost layer of investment from the private sector, into projects such as solar and windfarms. This was a ‘copout’ from providing real money transfers.

Mohamed Adow, director of the Power Shift Africa thinktank, said: “This [summit] has been a disaster for the developing world. It’s a betrayal of both people and planet, by wealthy countries who claim to take climate change seriously. Rich countries have promised to ‘mobilise’ some funds in the future, rather than provide them now. The cheque is in the mail. But lives and livelihoods in vulnerable countries are being lost now.”

Juan Carlos Monterrey Gómez, Panama’s climate envoy concluded: “This is definitely not enough. What we need is at least $5tn a year, but what we have asked for is just $1.3tn. That is 1% of global GDP. That should not be too much when you’re talking about saving the planet we all live on.” The final deal “comes to nothing when you split it. We have bills in the billions to pay after droughts and flooding. It won’t put us on a path to 1.5C. More like 3C.”

More than 60,000 people had registered to attend the conference which had seen hotel prices rocket 500%. A standard room at the Baku Holiday Inn cost £700 a night for the duration of the conference compared to the usual £90. FlightRadar24, a flight tracking website, revealed that 65 private jets landed in Baku in the first week, twice as many as usual.

Edi Rama, Prime Minister of Albania commented “People there eat, drink, meet and take photos together – while images of voiceless leaders play on and on and on in the background,” he said. “To me, this seems exactly like what happens in the real world every day. Life goes on, with its old habits, and our speeches – full of good words about fighting climate change – change nothing. What does it mean for the future of the world if the biggest polluters continue as usual?” asked Rama. “What on earth are we doing in this gathering, over and over and over, if there is no common political will on the horizon to go beyond words and unite for meaningful action?”

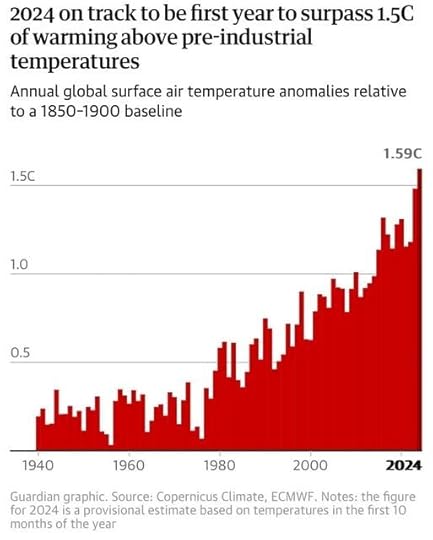

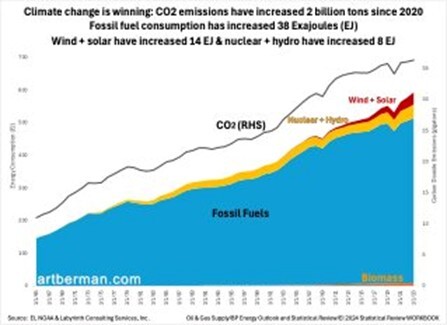

At COP29, there was no further talk of ‘the transition away from burning fossil fuels’ as pledged by the world’s nations just a year ago, with 2024 on track to set another new record for global carbon emissions.

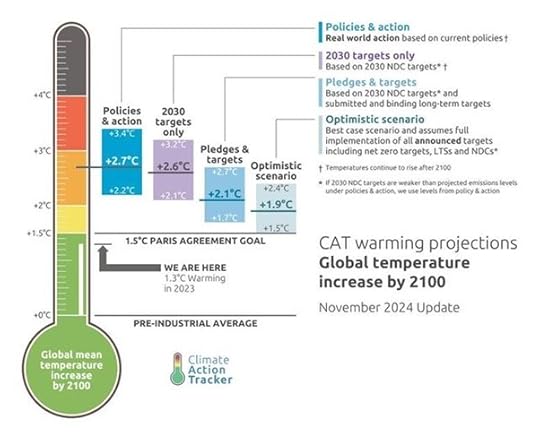

The latest data indicate that the planet-heating emissions from coal, oil and gas will rise by 0.8% in 2024. In stark contrast, emissions have to fall by 43% by 2030 for the world to have any chance of keeping to the 1.5C temperature rise target set by the COP Paris agreement. That target is dead and the planet is heading fast towards 2.0C rise (and above) compared to pre-industrial times.

Indeed, current policies put the temperature rise on track for a 2.7C rise. The expected level of global heating by the end of the century has not changed since 2021, with “minimal progress” made this year, according to the Climate Action Tracker project. The consortium’s estimate has not shifted since the Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow three years ago. “We have clearly failed to bend the curve,” said Sofia Gonzales-Zuñiga, from Climate Analytics. The expected level of warming is slightly lower when including government pledges and targets, at 2.1C, but that has also not changed since 2021. Warming in the most optimistic scenario rose slightly from 1.8C last year to 1.9C this year, the report found. “We are causing global warming 100 times faster than past natural changes. “We are taking Earth’s climate beyond natural limits, with CO2 & temps levels not seen for 3 million years.” said Mark Maslin.

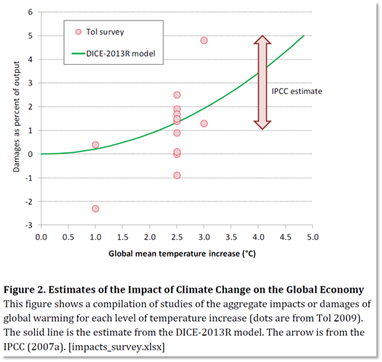

Changes in average global temperatures that sound small can lead to massive human suffering. Last month, a study found half of the 68,000 heat deaths in Europe in 2022 were the result of the 1.3C of global heating the world has seen so far. At the higher temperatures that are projected for the end of the century, the risk of irreversible and catastrophic extremes is also set to soar. Researchers warned their median warming estimate of 2.7C by 2100 had a wide enough margin of error that it could translate into far hotter temperatures than scientists were expecting. “There is a 33% chance of our projection being 3C or higher, and a 10% chance of being 3.6C or higher,” said Gonzales-Zuniga. The latter would be “absolutely catastrophic”, she added.