Michael Roberts's Blog, page 2

September 29, 2025

Argentina: the chainsaw breaks down

Last week US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent offered a $20bn swap line to Javier Milei’s government in Argentina and pledged to buy its bonds, as the Trump administration moved to shore up its ideological ally. The measures temporarily halted a rout in Argentine foreign exchange and bond markets triggered by the rapid depletion of the country’s foreign reserves as Milei sought to defend an overvalued currency.

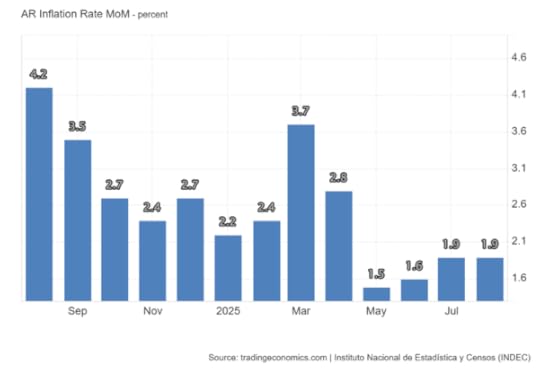

Over the past months, there has been wild optimism in financial markets and among mainstream economists and international agencies that Milei’s self-styled ‘chainsaw economics’ was working. Since taking office, Milei had taken a ‘chainsaw’ to government spending in welfare and public services and sacked thousands of public workers. As a result, the government budget was put into balance. Relying on record high IMF bailout funds to prop up the peso against the dollar, the Milei government has held the peso well above its real effective rate against the dollar in order to drive down Argentina’s horrendous inflation rate. It seemed that all was going well and all those the leftists and doommongers had been proved strong – chainsaw economics was working.

Foreign investors and international agencies rushed to praise the free market economics aims and fiscal austerity measures of the Milei government as a successful alternative to ‘pink socialism’. With a pin of Javier Milei’s signature ‘chainsaw’ affixed to her jacket, during a press conference at the IMF spring meeting, IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva urged Argentinians “to stay the course” and back Milei at the upcoming legislative elections in October. “It’s very important that they don’t derail the will for change,” she said.

Then the OECD followed up the acclaim. In its report on Argentina in July, their worthy economists pronounced that “against the background of a difficult legacy of macroeconomic imbalances, Argentina has embarked on an ambitious and unprecedented reform process to stabilise the economy. Reforms have started to bear fruit, and the economy is set for a strong recovery. Inflation has fallen to levels not seen in years. The upfront fiscal consolidation process started in late 2023 has been instrumental to taming high inflation. Still, fiscal policy will require further fine-tuning to maintain fiscal prudence in the medium to long-term, while boosting potential growth.”

But then the chainsaw broke, triggered by the provincial elections in Buenos Aires, the largest region in Argentina. Milei’s party was expected to do well, based on the apparent success of his economic policies. But instead – disaster. Milei’s party lost by a staggering 14 points and the opposition Peronist party won 6 out of 8 electoral jurisdictions, including three it hadn’t won in 20 years. Milei’s party’s vote share fell in all eight districts and he lost by 10 points in the crucial first district, which is both a bellwether and a major economic hub for the province.

So, unlike the mainstream economists, the IMF and the OECD, the Argentine electorate were not so enamoured of the ‘anarco-capitalist’ Milei’s chainsaw economics, especially with the scandals that abounded in the Milei administration. His sister Karina, called “the Boss” by him and appointed General Secretary of the Presidency (the highest ranking non-Cabinet office in the executive branch), allegedly has been taking bribes from all and sundry (‘Karina takes 3%’, said Milei’s personal lawyer).

But more important for the voters of Buenos Aires province was that Milei’s chainsaw had destroyed jobs, good paying jobs, closed many businesses and forced people into ‘informal’work ie to make a peso anywhere they could. Milei claimed that the Argentine poverty rate has fallen under his government. And it is true that, as the inflation rate fell, the official poverty rate also dropped, to 31.6 percent in the first half of 2025. But the official poverty rate uses an outdated basket of goods to measure the cost of living. When that is updated (soon), the results could well be worse. Anyway, the huge cuts in government spending have led to high environmental risk, according to an index that considers the presence of pests, accumulation of garbage, and proximity to sources of pollution. Only 27% of homes are on paved streets, while 46% are on dirt roads. Half of households studied didn’t have a formal water connection and the figure was as high as 95% in some neighborhoods. Meanwhile, 63% were not properly connected to the power grid; and 41% of families rely on community kitchens, a figure that reaches 60% in some neighborhoods.

The Milei administration has defunded soup kitchens, accusing the social organizations that run them of being corrupt. So in Córdoba, a study found that 58% of families couldn’t afford the basic food basket in August. Half of households said they were skipping one of their daily meals, usually dinner. Two-thirds of Argentine children under the age of 14 are living in poverty. Multidimensional poverty (measured as income plus lack of access to key welfare factors) increased inter-annually from 39.8 to 41.6 percent and within that figure, structural poverty (three wants or more) rose from 22.4 to 23.9 percent. In sum, 25-40% of Argentine families are in deep poverty. And there has been a further increase in inequality. The top 10% of income earners now earn 23 times more than the poorest decile, compared to 19 times a year ago. The fall in income reached 33.5% year-on-year in real terms among the poorest decile, but only 20.2% among the richest. The gini inequality index has hit an all-time high of 0.47.

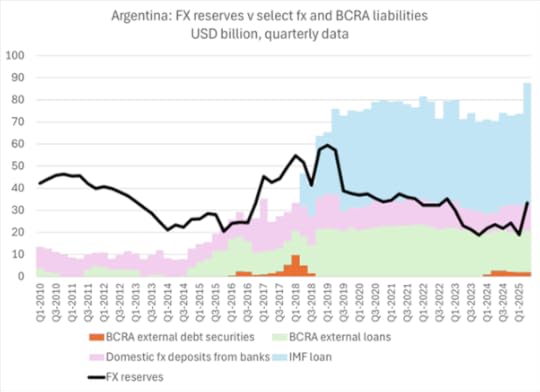

The Buenos Aires election ended the fantasy that Milei’s chainsaw economics and ‘free market’ policies were working. Capital, both domestic and foreign, suddenly realised that Argentines could soon vote out their hero and return the dreaded Peronistas to office. There was a run on the peso and the government and central bank was forced to use its scarce dollar reserves to try and keep the peso within the agreed exchange rate band with the US dollar, and so preserve the downward pressure on inflation. FX reserves dropped by more than $1bn a week, a rate that would soon have emptied the purse. Argentina has only $30bn in FX reserves. The government would not have been able to sustain the peso for much longer.

Source: Brad Setser

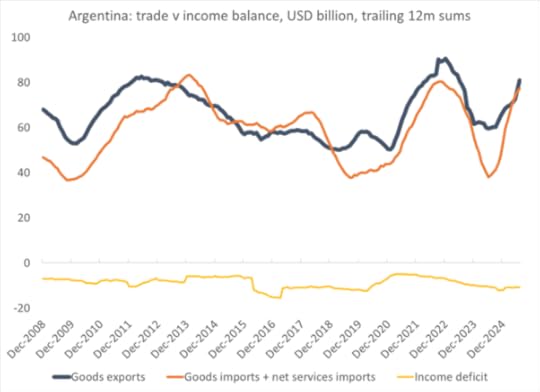

Milei may have balanced the government budget but the fiscal chainsaw did not deal with the continued weakness in the trade account. Under Milei, exports rose a little but imports also rose and income from exports flowed out. The monthly income deficit on the current account rose.

Source: Brad Setser

As soon as investors got hold of these FX dollars, they took them out of the country. In 2024, outbound investment totaled $3.3 bn (Argentines making portfolio investments abroad) and a $1.4 bn reduction in foreign portfolio investments into the country; so a total of $4.7bn outflow. In 2025 so far, another $2.6bn has left the country. This leakage of dollars is unsustainable.

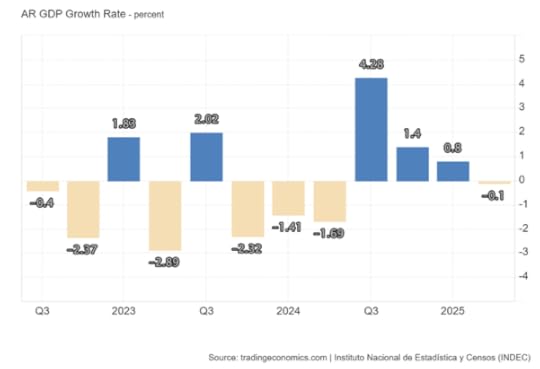

Why was this happening? As the government aimed to maintain a strong peso to keep inflation falling, it had to use its dollar reserves to fill the income and investment gap. The strong peso may have driven down inflation as import costs fell, but it also meant that Argentine exports could not compete in world markets. And balancing the government budget did not deliver more dollars, but instead led to economic stagnation. Indeed, in the last few months, economic growth has petered out.

And ironically, even the artificially overvalued peso is no longer pushing down the monthly inflation rate – it’s been rising for the last three months.

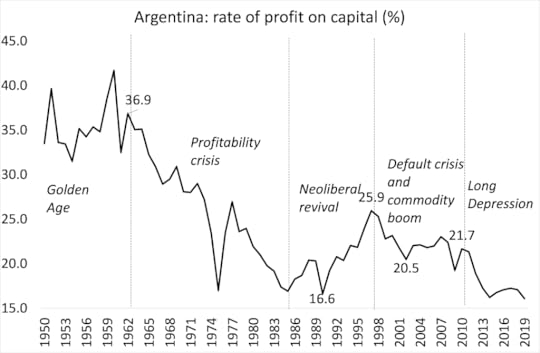

Given the strong peso, Argentine industry cannot compete, so it is not investing at home. Over the past six quarters (from Q2 2024 to Q2 2025), the investment-to-GDP ratio averaged a new low of 15.9%. Investment rates are low because the profitability of capital invested in Argentina is at a record low.

Source: EWPT series and author’s calculations

And that’s the long-term story of Argentine capitalism. The economy has basically stagnated since the end of Great Recession in 2088-9, particularly since the end of the global commodity prices boom in 2012. In the 13 years from 2012 to 2024, average real GDP growth was just 0.1%. Industrial output is falling and household consumption is stagnant, with retail sales falling. That’s hardly surprising when state salaries are down by 33.8% in real terms and Argentines are forced desperately to find work ‘informally’ as best they can.

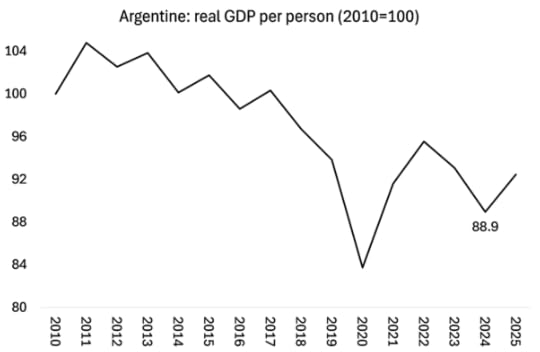

According to the IMF, real GDP growth was expected to expand by about 5½ percent this year. That does not seem likely now. But such a rise in real GDP in 2025, even if achieved, would only take per-capita GDP back to the level of 2021, when the economy was emerging from the pandemic. Indeed, the per capita GDP index would still be well below its peak of 2011 (at the height of the commodity price boom), some 15 years ago.

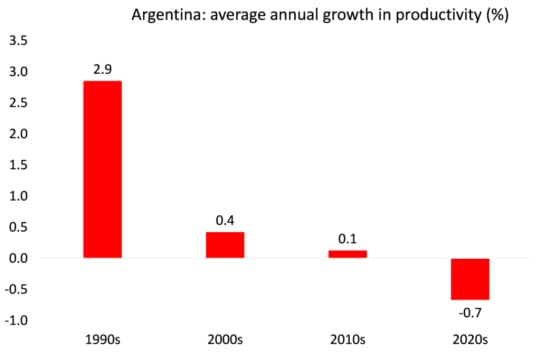

The key to economic success in Argentina, as it is in all economies, is an increase in the productivity of labour through more investment in the productive sectors of the economy. All the previous IMF loans ended up being smuggled or invested abroad or used for financial speculation. Neither right-wing nor Peronist governments did anything to stop this speculative robbery of the Argentine people and resources.

As Argentine Marxist economist Rolando Astarita has pointed out, Argentina’s underlying weakness is related to technological and productive backwardness. Except in sectors where Argentina has natural advantages, such as energy from the Vaca Muerta region or the soy and corn complexes, productivity standards are low relative to international standards. Even in soybeans, wheat, and corn, productivity is below that of US producers. These differences are essentially due to differences in the level of investment in inputs and technology.

Source: Conference Board, TED2

Argentina’s foreign exchange reserves are lower now than they were in 2018, despite the IMF making huge loans since then. Former President Mauricio Macri borrowed $50bn that year — the fund’s biggest ever bailout — before his political downfall blew the IMF programme off course and hit the currency. Now after allowing for the IMF’s loans and liabilities such as a swap line from China, Argentina’s reserves have stayed heavily negative this year despite the IMF advancing more than half of a fresh $20bn bailout upfront.

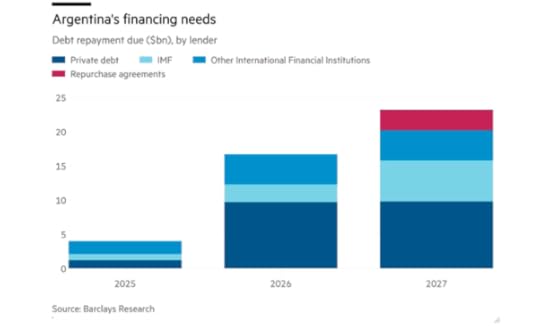

Beginning in September 2026, large FX debt service obligations to private bondholders are coming due. Argentina has $95bn of dollar- and euro-denominated debt, against net reserves of just $6bn, according to Barclays. And it has to make $44bn worth of debt repayments between now and the end of Milei’s term in 2027. So Milei can ill-afford to use scarce foreign exchange reserves to prop the peso.

Also the US government will expect to get its $20bn back and the IMF ia already owed $57bn of credit outstanding to Argentina, or 46 per cent of the total. Will they be prepared to add more bad money after good?

So a devaluation of the peso looks increasingly inevitable. The peso needs to fall about 30 per cent to restore Argentina’s competitiveness and rebuild FX reserves, according to Capital Economics. But if that were to happen quickly, inflation would spiral upwards just as before Milei came into office. Thus the Trump admistation has stepped up (temporarily) to fix the chainsaw. “The plan is as long as President Milei continues with his strong economic policies to help him, to bridge him to the election, we are not going to let a disequilibrium in the market cause a backup in his substantial economic reforms.”

The aim now is for Milei to win the mid-term congressional elections and then devalue (gradually?) to boost exports and bring in dollars. But that will also mean the return of high inflation. So much for chainsaw economics.

September 23, 2025

The UN at 80: ignored and irrelevant

The 80th edition of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA 80) opened yesterday in New York. The theme this year is: ‘Better together: 80 years and more for peace, development and human rights’, highlighting the urgency of delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and reinvigorating ‘global cooperation’.

When the United Nations was born in San Francisco on June 26, 1945, the overriding goal of the 50 participants who signed the UN Charter was stated in its first words: “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war.” One of the UN’s earliest achievements was to agree on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, outlining global standards for human rights. “The UN was created not to lead mankind to heaven,” said Dag Hammarskjold, UN secretary general, “but to save humanity from hell.” 80 years later, the current secretary-general Antonio Guterres cannot have such ambitious aspirations. “Guterres does say quite bold things. But he is now dismissed as on the sidelines and not a player,” says Mark Malloch-Brown, a former head of the UN Development Programme who was also deputy secretary-general under Kofi Annan in 2006. “The briefing room in Kofi’s day brimmed with journalists. Now it’s more mausoleum than press room.”

The demise of the United Nations mirrors the decline of all the international institutions formed by the agreement of the major powers who won the Second World War, when they met at Bretton Woods, US. The IMF, the World Bank, the UN and later the World Trade Organisation were international agencies set up supposedly to support nations in financial crisis, help end global poverty, achieve equitable trade; and avoid wars.

But that was always an illusion. These agencies were really formed to work under the hegemonic leadership of the US, backed by its junior partners in the top capitalist economies. They were institutions of post-war ‘Pax Americana’. The UN was different in that the policies and interests of US imperialism could not always be approved. The UN Security Council was the executive body of the UN, composed of the major post-war powers. And each member had a veto to block any UN action on ‘peacekeeping.’ That meant the Soviet Union and later Maoist China could stop US expansion and warmongering, although not all the time – the UN approved the US war against North Korea in the 1950s, a war conducted by the US under the UN flag. And there have been many other UN peace-keeping forces used to ensure the status quo for Western interests in the last 80 years. But increasingly, because of the Soviet/China veto, the US had to promote its war objectives globally outside of the UN: Vietnam in Asia; NATO intervention in the Balkans; and straight-forward US action in Cuba, Grenada, Libya and others. The ‘peace’ objectives of the UN were increasingly ignored as the US expanded its military might (with over 700 bases now around the world).

A key turning point was the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellite states in the early 1990s. Now it appeared that the US had carte blanche to do as it wanted, using the cover of UN approval. But with the two invasions of Iraq in the 1990s and then in 2003 American leaders found that they could not use the UN to support their ambitions. In 2003, after a series of grotesque lies were presented to the UN assembly on Saddam’s supposed ‘weapons of mass destruction’ to justify the invasion of Iraq and regime change, the US eventually decided to bypass UN approval and rely on the ‘coalition of the willing’ – ie the alliance of imperialist powers, which always chipped in to support US policy. The new political strategy of US imperialism was now the Washington Consensus, namely that the ‘democracies’ of the West should ally to weaken and defeat the ‘autocratic’ powers of Russia, Iran and Asia. The international rules for the world order would be set by the imperialist core without any input or consultation with the UN.

However, trends in the world economy brought down the Washington Consensus. Far from ruling the roost economically, US capitalism was in relative decline. That decline had started as far back as the mid-1970s as the European capitalist economies gained manufacturing share, followed by Japan. And in the 1990s, China emerged from its backward past and joined the World Trade Organisation. The US was increasingly left with only superiority in services, finance and military prowess – and still in the control of the IMF, World Bank and other ‘aid’ agencies. The US’ ‘exorbitant privilege’ of owning the world’s reserve and transactions currency, the dollar, was gradually undermined.

US net international investment position as % of US GDP

Source: IMF

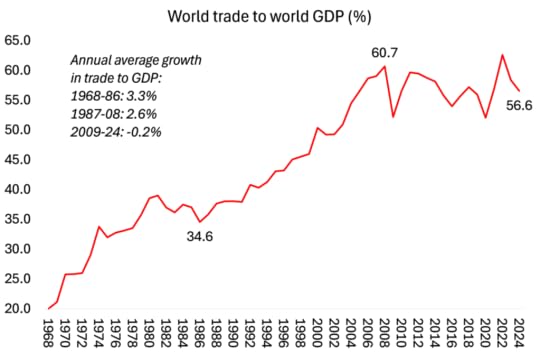

This relative decline was grudgingly accepted by successive US administrations while the world economy appeared to expand and the profitability of US corporations rose through the 1990s and into the early 2000s. But the global financial crash and the ensuing Great Recession that hit all the world’s capitalist economies changed all that. Globalisation – namely the exponential growth in world trade and capital flows – came to an end. US capitalism could no longer depend so much on the transfer of value through trade and capital returns to subsidise its deficits and debt – as it had for decades since the 1980s. This was a new world with new economic powers resisting US attempts to take the lion’s share.

Source: World Bank

Now the US was increasingly unwilling to use the Bretton Woods institutions to promote its interests – internationalism was replaced by nationalism – culminating in Donald Trump and MAGA. Now the UN was not only to be circumvented but even more, to be minimised and attacked. As Jean Kirkpatrick, who served as Ronald Reagan’s ambassador to the UN, famously suggested: the US would like to leave the UN but it was just “not worth the trouble”. The US under Donald Trump has withdrawn from the WHO and the UN Human Rights Council; while the UN Security Council is paralysed in the face of the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza; an intensfying trade war, and a funding crisis for the UN agencies.

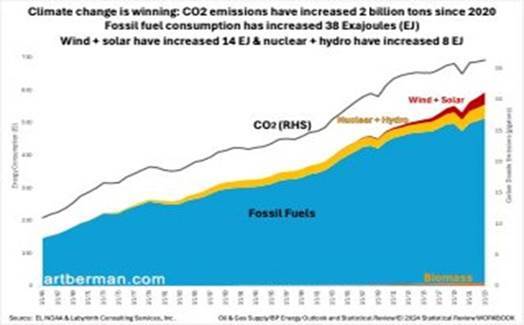

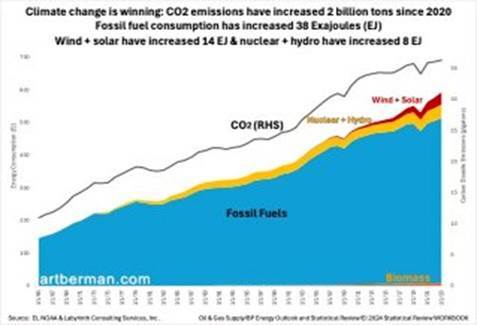

Nothing more illustrates the irrelevance of the UN in the 21st century than the issue of climate change. It is the UN-sponsored International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that collects and presents the science on global warming and predictions for the future of the planet and humanity. The IPCC delivers ever more stark warnings about the damage from global warming. But each international climate change meeting (COP) called by the UN, is ever more excruciatingly slow in reaching any agreement on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and, once over, national governments ignore or reject even the most mild targets for global action.

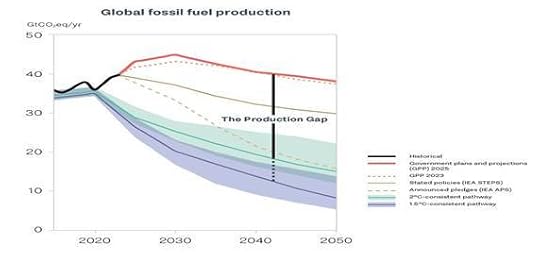

Indeed, the latest report shows that governments are now planning more fossil fuel production in the coming decades than they were in 2023. This increase goes against the commitments that countries have made at UN climate summits to “transition away from fossil fuels” and phase down production, particularly of coal. If all the planned new extraction takes place, the world will produce more than double the quantity of fossil fuels in 2030 than would be consistent with holding global temperature rises to 1.5C above preindustrial levels. Projected 2030 production exceeds levels aligned with limiting warming to 1.5ºC by more than 120%.

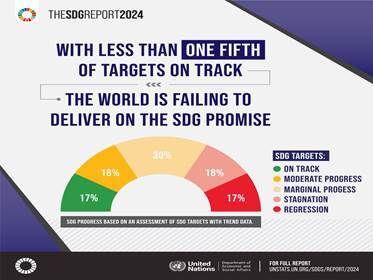

Then there is economic development to end poverty globally. In September 2015, the UN agreed on a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030. All countries supposedly pledged to work together to eradicate poverty and hunger, protect the planet, foster peace and ensure gender equality. What has happened in the last ten years? Just one-third of the SDGs are on track, with little prospect of achieving any significant progress in the next five years.

The 2024 Sustainable Development Goals Report highlighted that nearly half the 17 targets are showing minimal or moderate progress, while over a one-third are stalled or going in reverse, since they were adopted. “This report is known as the annual SDG report card and it shows the world is getting a failing grade,” UN Secretary-General Guterres said at the press conference to launch the comprehensive stocktake.

Then there is war and the UN aspirations for world peace. The UN now appears to have no role in avoiding wars or maintaining peace. Instead, Donald Trump proclaims that he, as the leader of the US, the hegemonic power, is ending wars (seven so far, according to Trump). The US is now openly running ‘peace’ negotiations globally as it suits it, not the UN. Trump has even been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize!

Alongside all Trump’s boastful rhetoric about ending wars, the cruel reality is that US imperialism is stepping up conflicts globally. Trump calls for Canada to become the 51st state; he wants to buy Greenland from the Danes (despite the inhabitants having their own autonomous parliament); he begins to surround Venezuela with his military. And of course, above all, the US continues to back Israel in its horrendous destruction of Gaza and occupation of the West Bank and the killing of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, leaving the UN paralysed. As Sigrid Kaag, a former deputy prime minister of the Netherlands who has had several roles at the UN, including as special co-ordinator of the Middle East peace process, put it. “The UN is at a point of irrelevance. That is its predicament. The dream might live on, but no one looks at the news and says: ‘What happened in the UN?”

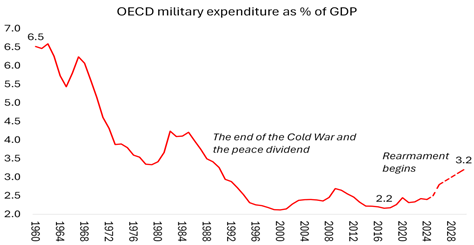

The dark reality is that the UN is heading for the same fate as The League of Nations in the inter-world war period of the 20th century. The League was founded in 1920 and lasted only 18 years of relative peace until fascist states in Europe and Japan launched their invasions. Now in 2025, military spending is rising fast everywhere. Defence budgets are being doubled, with NATO countries aiming at 5% of GDP for the armed forces by the end of this decade – a level not seen since the founding of the UN. Trump has (rightly) changed the name of the US Department of Defense to the Department of War.

The failure of the UN is the organisational symbol of the failure of world capitalism to unite people and states to end poverty globally, stop global warming and environmental collapse and prevent continual and unending wars. Mark Malloch-Brown, a former head of the UN Development Programme who was also deputy secretary-general under Kofi Annan in 2006 summed it up: “In many ways the UN is the walking dead,” he says. “It never quite falls over and yet it is still a corpse.”

September 22, 2025

IIPPE 2025: immigration and the world order

The 2025 conference of the International Initiative for thePromotion of Political Economy (IIPPE) just took place in Ankara, Turkey. The IIPPE was founded in 2006 with the aim of “developing and promoting political economy in and of itself but also through critical and constructive engagement with mainstream economics, heterodox alternatives, interdisciplinarity, and activism understood broadly as ranging across formulating progressive policy through to support for progressive movement.” The intention of IIPPE “is to develop and promote political economy, especially but not exclusively Marxist political economy.”

I was unable to go to Ankara for the conference, but I did participate in some online sessions organised by the China Working Group of IIPPE and presented in one session. But I was also able to obtain some of the papers presented by the participants in the main conference. So I can give a view on just a few of the papers presented.

The main theme of this year’s conference was Immigration: Crisis of the World Capitalist System, Crisis for the World Capitalist System and the plenary speaker on this was Hannah Cross from the University of Westminster. In 2021, Hannah Cross wrote an important book offering a Marxist perspective on immigration, called Migration Beyond Capitalism.

In her book, Cross argued that global migration was driven by capital’s need for cheap labour. Immigration was encouraged to provide a ‘reserve army of labour’ that would keep wages low and also divide working people. This migration also led to removing a sizeable number of able-bodied workers (often the more highly educated and skilled) from their home countries in the search for work – the so-called ‘brain drain’.

In her book, Cross uses migration-studies research to show that border regimes have very little effect on the overall volume of migration, which is primarily dependent on conditions in migrants’ home countries and labour-market opportunities in the host countries. And there is little to no relationship between the volume of migration to an area and anti-migrant attitudes in that area – rather, what causes anti-migrant attitudes is the intensification of border systems.

With increased global warming, migration will accelerate in the decade ahead. That will increase the contradiction between native-born workers and immigrant workers – so nationalist and racist attitudes are likely to increase. But Cross argues that, just as there is a material basis for the division between workers under capitalism, so must there also be a material basis for unity. It is, again, the capitalist system itself that provides this material basis. Capitalism gives workers common problems to confront and struggles to undertake, with these struggles often resonating across borders. Ending imperialism in the Global South is a precondition of ending borders for immigration in the Global North.

There is a lot more to be said on migration and there were several papers on the theme at IIPPE that I cannot comment on. So I shall move onto China. The China Working Group within IIPPE held a series of workshop presentations before the official conference and also sessions in the conference itself. One of the workshop was on ‘China is not imperialist’. This is a controversial issue among Marxists, many (most?) of whom consider China as both capitalist and imperialist, and that issue was also debated at the China sessions.

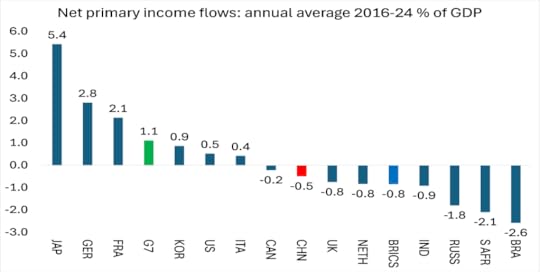

I presented paper on whether China was imperialist, based on Lenin’s key categories for imperialism, particularly on how imperialist states moved from direct colonial dominations to economic domination through monopoly companies dominating trade and through the export of capital to exploit the peoples of what we now call the Global South. In my paper, I argued that there are now four ways that capital in the so-called Global North gain transfers of surplus value from the capital and labour of the Global South: first, the transfer of value through international trade (unequal exchange); second, through cross-border flows of profit, interest and dividends; third, through flows and the stock of foreign direct investment; and fourth, through ‘excess yield’ (returns) on net foreign assets. There is no room to spell out all the points here (see the paper).

The major peripheral economies (including China) are transferring billions in value to the imperialist North through these avenues of trade and capital flows, although it is true that China’s phenomenal rise as a manufacturing power has increasingly reduced and even reversed its losses of value on trade with the Global North. But as one study has shown, China’s switch from net loser to net gainer in international trade was almost entirely due to high investment and technological advances ie a rising capital composition. So my conclusion was that China still did not fit the bill as an imperialist economy.

In the same session, Mick Dunford, Visiting Professor, Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR), Chinese Academy of Sciences, argued that those who claim China is imperialist forget the historical development of China as one of the most exploited and abused nations in the history of imperialist and colonial domination. imperialism was a system where capital went beyond its own boundaries, not just economically but also politically and militarily, with the aim of domination of the periphery. By that definition, China could not be an imperialist state.

In another session, Esther Majerowicz from Brazil seemed to argue to the contrary, appearing to argue that China was a capitalist economy that had developed an imperialist-style extraction of profits and resources from the Global South and indeed it had become a major imperialist rival to US global hegemony. Her arguments were based on her book, jointly edited with Edemilson Parana, called China in Contemporary Capitalism (2024).

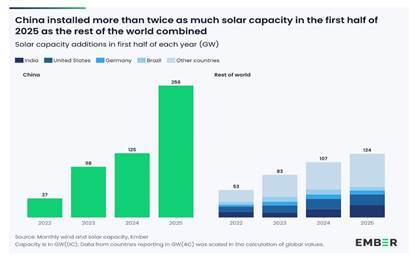

Whatever side you take on this, there were several other papers that outlined the huge progress that China has made in development not just of industry, but also increasingly in hi-tech sectors, mostly vividly observed in the production of electric vehicles and solar equipment, which China is exporting in massive amounts to the rest of the world.

Again, in this post I cannot fully cover the many papers on China and the character of its development and progress, so I’ll move on to some interesting presentations on Marxist economics. Oleg Komolov from Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, presented a paper on Unequal Exchange and the place of Russia in Global Economy. I don’ t have this presentation, but an earlier paper by Komolov showed that the Russian economy in the 2010s had a permanent net capital outflow through private and public channels. This led to a depreciation of the ruble. That boosted energy and resources exports but inhibited the wider growth of the Russian economy. So Russia remained part of the periphery in global capitalism. In my view, the Russia-Ukraine conflict sustains that model, but with capital controls blocking outflows.

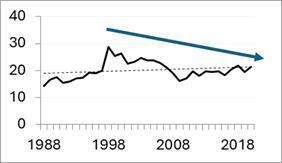

There was an interesting session on Marx’s law of profitability. Ekin Değirmenci presented an analysis of the Marx’s law as applied to Turkish manufacturing from 1988 to 2020. He found that the rate of profit in Turkish manufacturing rose from the late 1980s to 1998 but declined thereafter. To me, that fitted in with the trend in all the major economies – a rise through the 1980s to the late 1990s and then a decline through to the end of 2010s. And following Marx, Değirmenci found that the downward force on profitability was a rising organic composition of capital (capital intensity) with the main counteracting factor being a rising rate of surplus value (labour exploitation).

Turkey manufacturing: profit rate: weak rising trend overall, but declining post-1998

Luis Arboledas-Lérida presented an excellent critique of the widespread view among Marxist economists that knowledge has no value in exchange as a commodity, so that value gained by the owners of knowledge commodities is not appropriated from the labour of their workers, but only through ‘monopoly rents’. Lerida argues that this theory of ‘knowledge rents’ endorses a totally unrealistic conception of knowledge; it deploys the economic category of ‘rent’ in a manner utterly unrelated to the Marxian framework and Marx’s analysis of ground-rent, despite claims to the contrary; and is actually based on mainstream neoclassical theory. The critique of the theory of monopoly rents has been taken up before by AK Norris and Tavo Espinosa. And Arboledas’s paper reiterated his critique made at the HM 2024 conference.

There was also an interesting session of papers on money hoarding, world money and cryptocurrencies. Unfortunately, I do not have the papers for these. And there was a plenary session led by Galip Yalman from the Middle East Technical University, Ankara on ‘Central Banks as Hegemonic Apparatuses’. The role of central banks is a hot topic among the mainstream at the moment, given the ongoing attempt of Donald Trump to take control of the US Federal Reserve and end its supposed independence.

In my view, central banks were never neutral bodies designed to provide expert advice and decisions on controlling interest rate, money supply and affecting the wider economy. Central banks were created as ‘lenders of last resort’ to ensure that the banking sector did not implode and would continue to ‘lubricate’ the capitalist economy. In the post-1945 period, they morphed into agencies for ‘managing the economy’ (with little success); and the neoliberal period saw a drive to establish their ‘independence’ from any leftist governments in the interests of finance capital.

As usual, IIPPE had many papers and sessions that I could not include in this short post. But have a look at the IIPPE programme, and perhaps you can follow up on the authors of papers that interest you.

September 14, 2025

US economy: stagflation now more than a whiff

The US economy has a widening gap: between rising inflation on the one side and employment on the other. According to mainstream Keynesian theory, that should not happen. That’s because a weakening labour market should lead to a fall in wage increases and in consumer demand and price inflation will subside. The experience of the 1970s economies disproved that theory supposedly supported by the so-called Phillips curve (ie a trade-off between price rises and unemployment). Inflation erupted while unemployment rocketed. The decade of the 2010s after the Great Recession again disproved the theory, when inflation in the major economies subsided to near zero and unemployment rates were at record lows. In the post-COVID period from 2021 to 2024, inflation rates rose sharply and yet unemployment rates stayed low.

Why was Keynesian theory wrong? It was because Keynesian theory assumes that it is aggregate demand that drives spending and prices. If demand outstrips supply, prices will rise. However, in each of these periods, the 1970s and the 2010s, it was the supply-side that was the driver, not aggregate demand. In the 1970s, economic growth slowed as profitability of capital and investment growth plummeted and then energy supply was restricted by the oil producers and crude oil prices rocketed. In the 2010s, economic growth crawled, inflation rates dropped but unemployment did not tick up. In 2020s, the post-pandemic slump led to a breakdown of global supply chains, an energy price hike and a reduction in skilled labour. It was a supply-side problem.

Monetarist theory was also exposed in these periods. Central banks – especially the Federal Reserve under Ben Bernanke, a disciple of the arch monetarist Milton Friedman, who claimed that inflation was essentially a monetary phenomenon (ie money supply drove prices) – assumed that the answer to the Great Recession of 2008-9 was to cut interest rates and boost to money supply through what was called quantitative easing (QE) ie the Fed ‘prints’ money and buys government and corporate bonds from the banks, which in turn were expected to increase lending (money supply) to companies and households to spend. But that did not happen. The real economy remained in depression and all money injections simply boosted financial asset prices. Stock and bond prices mushroomed. Again, monetarism ignored the real drivers of economic growth, spending and investment: the profitability of capital ie the supply-side.

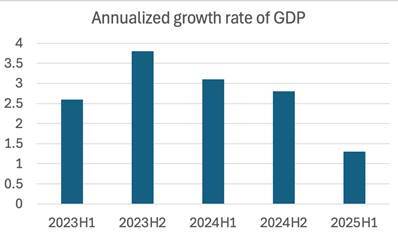

Back last February, in a post, I suggested that the US economy had a ‘whiff of stagflation’. ‘Stagflation’ is when national output and employment stagnates or rises only very slowly and yet price inflation continues to rise and even accelerate. The US economy has clearly been slowing. Quarterly growth rates have been erratic, mainly because of wild swings in imports, which surged early this year as companies tried to ‘front-run’ Trump’s import tariff increases, and then real GDP growth slowed as tariffs started to affect necessary import components for industry. But the first half of the year shows a clear slowdown under Trump.

Indeed, economic growth dropping towards what some analysts call “stall speed” — “a pace below which the economy slips into recession (an outright fall in GDP). The US economy is not yet in recession because profits are still rising for the US corporate sector and the AI investment boom is still driving key sectors of the economy. But stagflation is now more than just a whiff in the economic air as it was at the beginning of 2025.

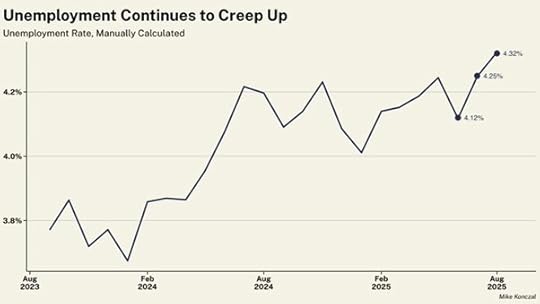

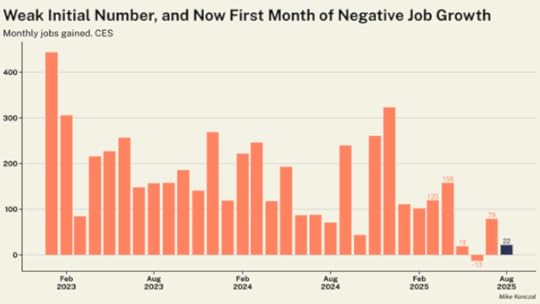

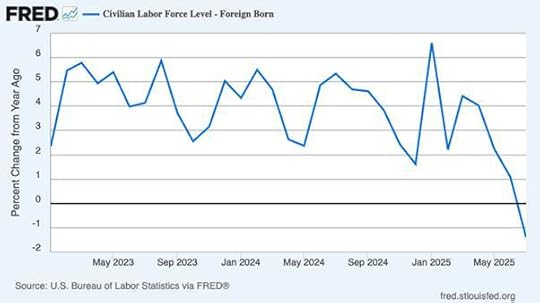

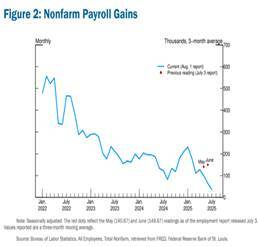

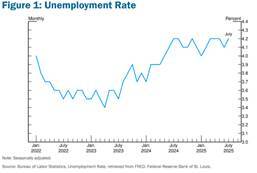

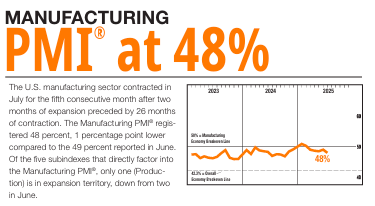

Take jobs. Employment growth is slowing fast and unemployment is creeping up.

In August net jobs increased by just 22,000, while June was revised down to a fall of 13,000.

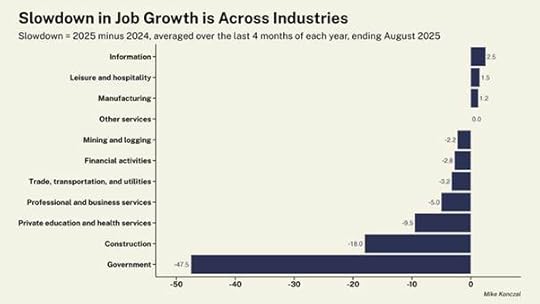

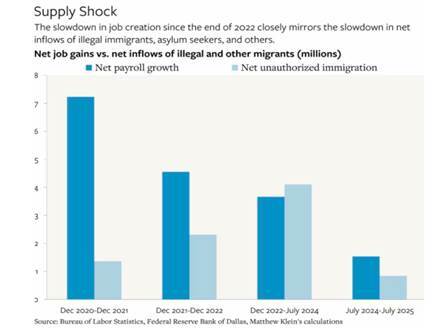

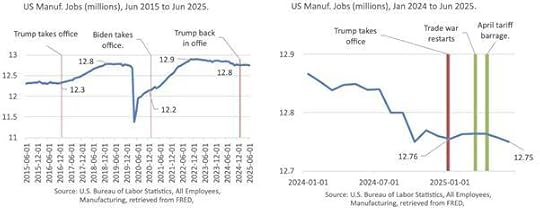

Trumponomics argued that that tariffs would build up manufacturing jobs and federal workforce cuts would free up workers for them. No chance. Manufacturing lost jobs almost as fast as the federal workforce (-12K vs -15K). Job growth is slowing across nearly all sectors.

Job losses are particularly severe for men. Males have lost 56,000 jobs over the past four months. The main reason is that Trump’s attack on immigration has led to a significant fall in the labour force. The ICE is making mass arrests and deportations, but the number of foreign-born workers in the United States was already shrinking after years of rapid growth. Native-born workers have not gained from this – unemployment there is at its highest rate since the end of the pandemic. Increases in both youth and black unemployment (now at 7.5%, the highest since October ‘21) suggest that the crackdown on immigration has not created a more favourable job market for the more vulnerable components of the US labour force.

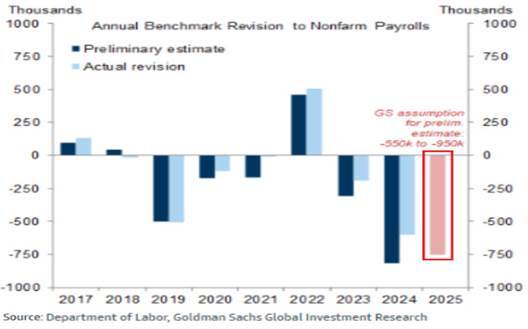

Trump sacked the head of Bureau of Labor Statistics after the BLS recorded a very weak jobs growth figure. But since then, annual revisions of the jobs figures have reduced employment growth by 911k in the year to March 2025. Sacking the messenger does not change the message. US jobs growth has slowed to a rate outside of recessionary periods not seen for more than 60 years. Employment growth is slowing, not because of weak demand but because supply growth is drying up as immigration falls, manufacturing stays in recession and the government agencies and workforce are decimated by Trump.

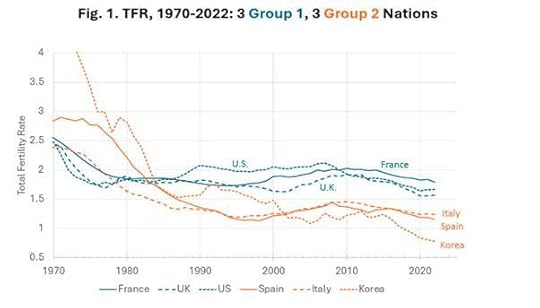

The basic problem is that a lack of demand is not the constraining factor in American manufacturing; it’s the workforce. The number of workers who are able and willing to work on a factory floor is shrinking. Almost 400,000 manufacturing jobs are currently unfilled, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Fewer productive workers mean less growth. And there is nothing the Fed can do about this, either by cutting interest rates or resorting to more monetary injections (quantitative easing). Even if Trump got his way, sacked some Fed board members, then took control the Fed and to make deep reductions in the Fed’s policy interest rate, all that would do is fuel yet further the speculative boom in the stock market, with little effect on the productive sectors of the economy.

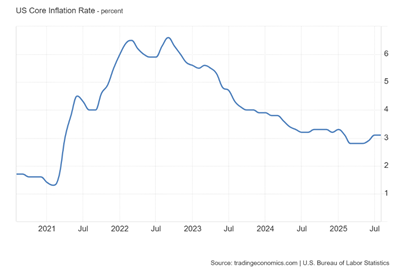

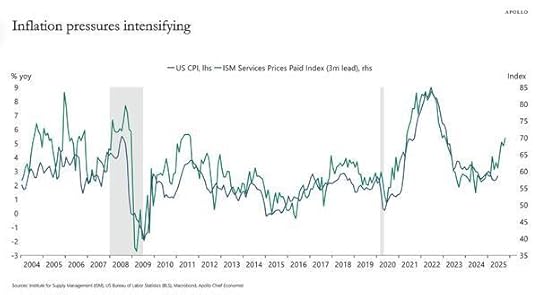

The Fed’s current board is reluctant to cut interest rates because it fears inflation would accelerate. Inflation is already on the up. The latest headline consumer price inflation rate accelerated to 2.9% year over year in August 2025, well above the Fed’s target for inflation at 2% a year. The Fed likes to follow what it calls the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation rate. This always handily lower than the average price rise in consumer goods for American households. But even the PCE is staying above the Fed’s target at 2.6% yoy. The core inflation rate (which excludes energy and food prices) is stubbornly stuck at 3.1% yoy.

Again, this rise in inflation is not due to increased demand for goods and services outstripping supply; it is due slowing production and rising costs within production, particularly in services like utilities, healthcare insurance etc.

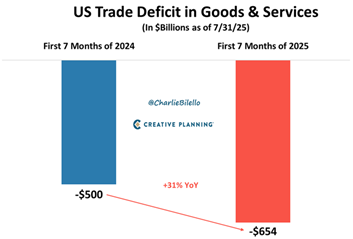

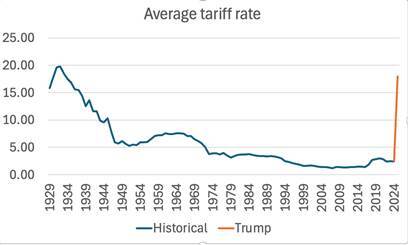

The Trump officials argue that that tariffs are having no impact on inflation. But if that were true, then it would mean the ‘supply shock’ to prices was happening anyway. It is true that, so far, the impact of the tariff has been limited. That’s because as soon as Trump started his tariff tantrums, US importers rushed to maximise stocks and run ahead of the tariff hikes. That’s why the US imports rocketed in the first half of 2025 and the US trade deficit sharply worsened.

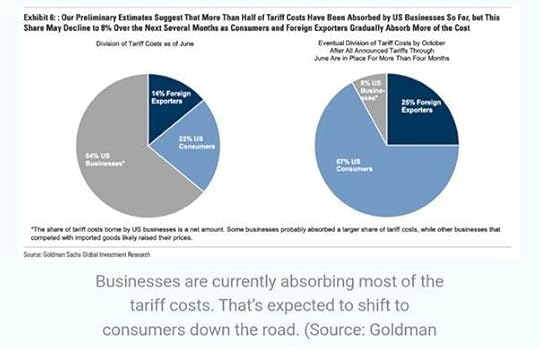

Also, some foreign exporters to the US reduced their prices to absorb the hit to import prices from the tariffs. But tariff hikes will eventually come through to consumer prices. Already, about 22% of tariff costs have been passed onto consumers, according to a Goldman Sachs analysis. GS reckon that will eventually rise to 67%.

Given that the effective tariff on imports is now around 18% (up from about 4% before Trump started) and imports are about 14% of US GDP, then that can only mean an additional rise of about 1.5% pts to the inflation rate over the next 12 months, taking US inflation up to 4.5-5%.

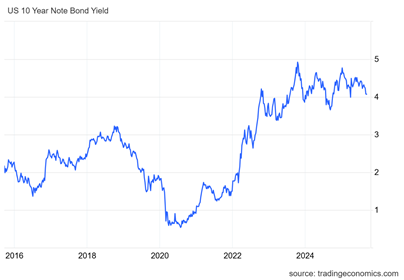

It’s this potential rise in inflation that worries government bond investors in financial markets. They will want higher yields to compensate for the reduction in real returns from higher inflation. So we can expect US long-term government bond yields to rise even if the Federal Reserve cuts short-term rates.

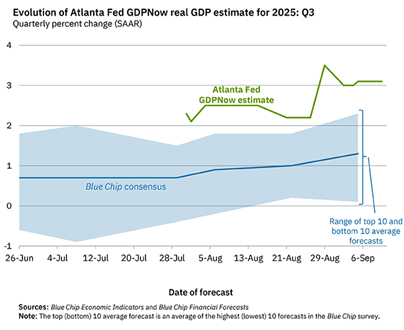

So the forces driving stagflation are getting stronger. However, that does not mean the US economy is imminently heading into an outright slump. A slump is when total output falls (mainstream economists like to call a fall in total output for two consecutive quarters, a ‘technical recession’). The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) tracks recessions and it applies a wide range of indicators to ‘call’ a slump. But the NBER judgement is always retrospective (ie after the slump is over). So far, the NBER has not called a recession. There are other forecasting models that try to track the rate of expansion in the US economy. The Atlanta Fed GDP Now model is popular. It is currently forecasting US real GDP to be rising 3.1% at annualised rate for the third quarter of this year – although note that the consensus of all the leading forecasters is about 1.3%.

The New York Federal Reserve also has a forecasting model. The New York Fed Staff Nowcast for 2025:Q3 is currently 2.1%. Again, this is an annualised rate, which is not the same as the quarterly rate or the year over year rate. But so far, whatever the measure or model, the US economy is still expected to have expanded from June to September this year, if at a slower pace.

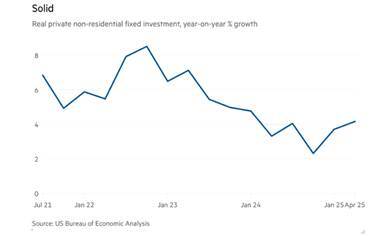

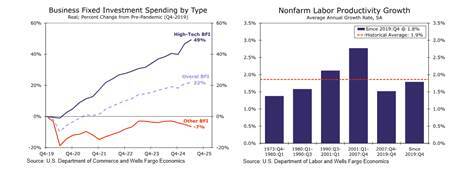

I and others have shown that a slump only follows when business investment contracts sharply and business investment only does so if profits start to fall. So far, business investment is still positive at about 4% a year.

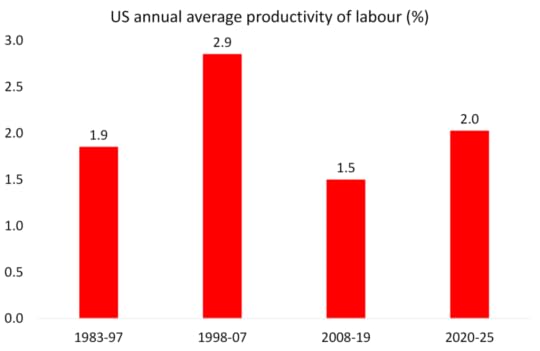

However, much of this growth in business investment is concentrated in high-tech AI spending on data centers and other infrastructure for the supposed boom in AI. Since 2019, that sector of business investment is up nearly 50%, while the rest of US corporate investment is down 7%. The impact of hi-tech, AI investment has budged up the growth rate in the productivity of labour slightly, but it is still below the rate of 1990s and 2000s. If the AI investment boom falters, then business investment will plummet.

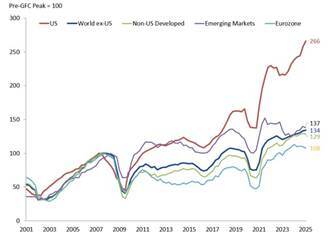

As for profits, US business has done much better than anywhere else. Since the peak before the global financial crisis, US corporate profits have surged by 166% – far outpacing other regions. By contrast, the eurozone has barely moved, with corporate profits up only 8%.

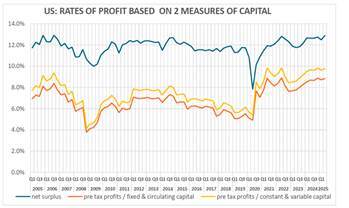

And the profitability of US capital has improved since the end of pandemic slump in 2020. According to calculations by Brian Green, the US corporate pre-tax rate of profit on capital is at a higher level than in 2006.

My own calculation for the US rate of profit since the end of the Great Recession and after the COVID pandemic is similar.

Source: EWPT 7.0 series, Basu-Wagner et al, AMECO, author’s calcs

Corporate profits are still growing. Operating income for S&P 500 companies (excluding financials) grew 9% in the most recent quarter, compared with the year before. But that figure includes the mega profits of the so-called Magnificent Seven hi-tech companies. If they are excluded, then the rest of the non-financial, non-energy companies’ earnings growth is about 4-5% and slowing. Profits growth among these companies is being squeezed by rising costs of production rise. That will intensify as the imports tariffs drive up the prices of components and raw materials.

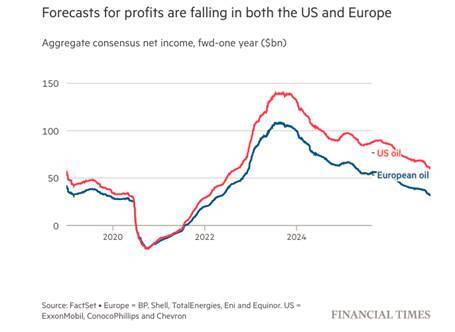

In addition, crude oil prices have been falling and this is reducing profits for the US energy sector. Capital spending on global oil and gas production is forecast to drop 4.3%, the first annual fall in investment since 2020. The energy companies are cutting jobs, slashing costs and scaling back investments at the fastest pace since the pandemic slump. The US shale industry has been hit particularly hard.

Trump and the MAGA team claim that tariffs will bring in so much tax revenue ($1.8trn) and new business investment ($3-5trn extra) that the economy will boom (4% next year, they claim) and that will lead to hundreds of thousands of new jobs. But there is no evidence to support these claims.

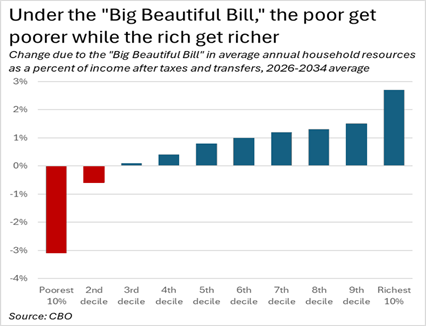

Actual tariff revenues total about $134 billion through August 2025. Meanwhile, the federal government budget deficit shows no signs of contracting – on the contrary. Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill Act passed in July promised deficit cuts, but current projections show ongoing deficits. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the federal budget deficit in fiscal year 2025 will be $1.9 trillion. Projected tariff revenues for this year are a tiny proportion of federal government revenues, just 2.4%.

And over the next few years of the Trump administration, corporate tax and income tax cuts for the higher earners will reduce potential revenue much more than increased tariffs will raise. Indeed, these tax cuts will constitute the largest transfer of income by a government from the poor to the rich in a single law in history.

Tariff revenues are not going to reduce the annual federal government deficit currently at over 5.5% of GDP (if slowing slightly). Indeed, projections are for the annual deficits to rise to 5.9% of GDP over the next ten years, with the public debt to GDP ratio heading towards 125% of GDP. The rising public debt ratio is another worry for investors in government bonds and so will drive up bond yields whatever the Federal Reserve does to reduce short-term rates.

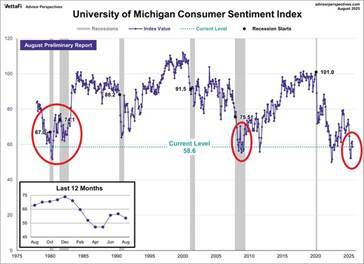

American households are feeling the pinch. Consumer sentiment about the economy has fallen to one of its lowest survey readings this century – in line with the Great Financial Crisis levels and the 1980s recession levels.

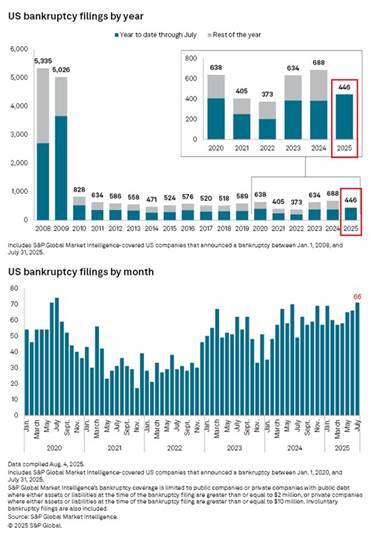

And the weakest parts of the corporate sector are struggling. There have been 446 corporate bankruptcies year-to-date, the most in 15 years.

I started off this post by arguing that the US economy is entering a period of ‘stagflation’ ie rising inflation and rising unemployment. Stagflation shows that both the Keynesian and monetarist theories of inflation are false. And that means whatever the Federal Reserve does on interest rates or monetary injections will have little or no effect on inflation or employment – the supposed objectives of the central bank.

Whether inflation and unemployment subsides or not depends on whether US real GDP and productivity growth revives or not. That depends on whether business investment continues to grow or not. And ultimately, that depends on whether business profitability and profits are sustained or fall. So far, there has been no fall, but the downward signs are becoming visible.

September 7, 2025

Norway: the fossil fuel capital of Europe

Norway has a general election today. In a country of 5.6m people, some 4m are entitled to vote and there is usually a high turnout by international standards – over 75%. Indeed, early voting has become increasingly popular, with up to 60% voting before the official day.

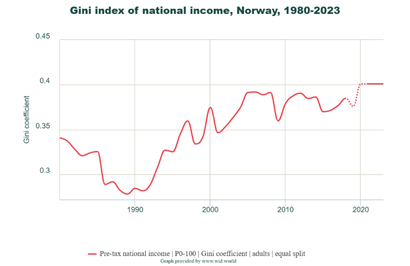

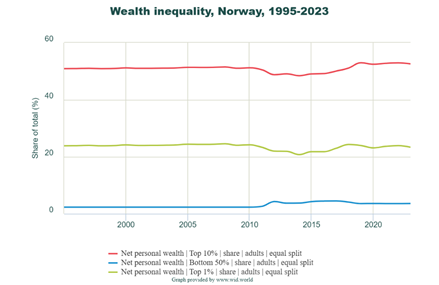

Norwegians are probably the richest nation in the world – if you measure that by average income per person . Per capita income is higher than any other major economy – only the tax havens of Switzerland, Luxembourg, Monaco etc are higher. But average income disguise the extremes of inequality. And as in every other capitalist economy, inequality of income and wealth is high in Norway. The Nordic and Scandinavian countries with their social democratic history are supposed to have the least inequality and lowest poverty in the modern world. But that reality has disappeared over the last 30 years. The gini index of income inequality (where 0 = equality and 1= one person has all) has risen from a modest 0.25 ratio in 1990 to near 0.40 in the 2020s, a ratio now higher than many advanced economies

And when it comes to personal wealth, inequality is even more extreme (as it is in all the Scandinavian countries). Just 1% of Norwegians own 22% of all personal wealth in the country, while the bottom 50% of adults have just 3.6%.

On these measures, Norway is no social democratic paradise. And this increasing inequality concerns Norwegian voters. Inequality tops voters’ list of concerns, according to an August 7-13 survey by Respons Analyse for daily Aftenposten. Norway has had a wealth tax (formuesskatt) since 1892, some years before securing full independence from Sweden. Along with Spain and Switzerland, it is one of only three European nations to still tax capital in this way. The current rate stands at 1% for those with assets of more than 1.7m kroner (£125,000) and 1.1% for those with more than 20.7m kroner.

The tax is collected annually, and is calculated by adding up the value of properties, savings, investments and shares, and deducting any debt. Private companies count as part of their owners’ wealth. There are discounts – for example, only 25% of the value of citizens’ primary residence is taxable. The tax raises about NKr32bn ($3bn) and affects about 725,000 Norwegians, most of whom pay little.

Norway’s billionaires are hit hardest and they are screaming. And Norway’s billionaires are getting richer. In 2024, the 400 wealthiest were worth 2.139tn kroner, up 14% in a year, according to the business magazine Kapital and half of this wealth was controlled by families relocated abroad. Thirty of them left Norway when Labour raised the tax. This election has led to yet another mighty campaign by the rich and right-wing politicians to ditch the tax. Labour, as you might expect, sits on the fence. It has promised to set up a cross-party commission ‘to review all taxes’.

But the wealth tax is not the issue that mainly worries Norway’s mainstream politicians; they are obsessed with the apparently impending invasion by Putin’s Russia and the need to increase ‘national security’ and raise defence spending. The current Labour-led government is committed to increasing defence spending to 5% of GDP in line with NATO targets. And that policy won’t change whichever party leads the next government after this weekend.

Norway’s economic success over the last 50 years has been based almost entirely on huge oil and gas production off the coast. Norway’s $2 trillion sovereign wealth fund, built on the vast oil and gas income, is equivalent to $340,000 per Norwegian citizen. The fund allows governments to spend much more freely on public services and welfare benefits than fellow European countries. And the Ukraine war has brought a bonanza to Norway’s energy giants. Norway is now Europe’s top gas supplier, replacing Gazprom after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. And its role is set to grow as the European Union plans to phase out use of Russian gas by 2027.

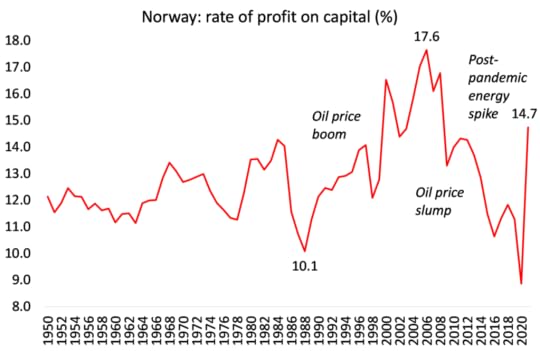

Exploiting new oil and gas reserves is critical to slowing down an expected production decline. But many Norwegians are worried about the impact of fossil fuel production on global warming and the climate. They have taken to buying electric cars, boats and trucks and adopting other ‘green’ policies, supported by government subsidies. Nevertheless, Norway’s economic success is still wedded to the energy giants and Norwegian capital depends on fossil fuel production. The profitability of Norwegian capital is founded on the global prices of oil and gas.

Source: EWPT, AMECO, author

No wonder the right-wing, anti-immigrant, climate sceptic Progress Party, which is doing well in the opinion polls, campaigns for more oil production and exploration. “Norway should be the last country in the world to stop production . . . We want to pump oil for another 100 years,” said Sylvi Listhaug, the Progress Party leader. This is music to the ears of the energy giants.

Equinor, Aker BP and Shell are some of the most active companies on the Norwegian continental shelf and they are still both exploring and investing heavily in existing fields in the North and Norwegian Seas. Shell recently unveiled new technology to boost recovery to 75% from the Ormen Lange field, which is Norway’s second-largest for gas. The profit from that field alone will cover the extra cost of recovery within a year. Oil and gas companies are set to invest a record NKr275bn ($27bn) this year. One of Norway’s leading non-oil business people says: “This has been a phenomenally successful industry for the country. It’s not going to stop by itself.” Despite all the fine words on the environment, the current Labour-led government does not resist. Espen Barth Eide, Norway’s foreign minister, argues that the EU will need Norwegian gas in particular for a long time because there is still “a long way down to the level where you need Norwegian supplies, because you want to get rid of the Russian and other non-western sources of petroleum first.”

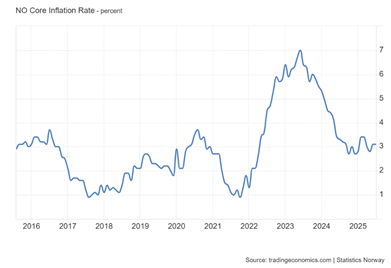

However, huge profits for the energy companies are not being matched by improved prosperity for Norwegians – rich as they are. Since the end of the pandemic, the cost of living has rocketed (as it did in all countries); food prices are up near 6% in the last 12 months. Overall inflation stays well above the central bank target of 2% a year and is now rising.

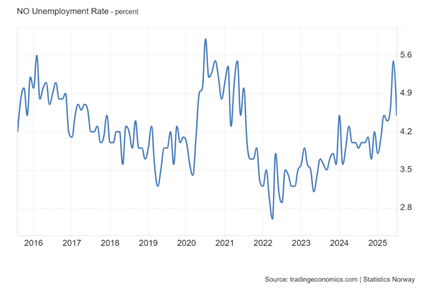

At the same time, unemployment is turning up.

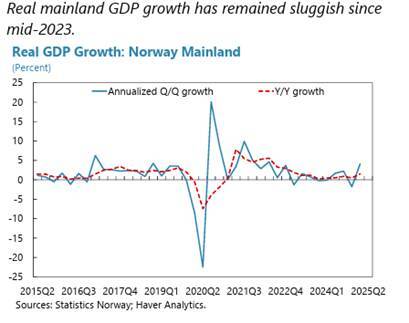

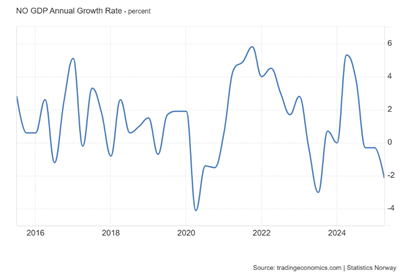

So signs of a stagflationary economy (as in the rest of Europe) are appearing, even in rich Norway. Excluding the energy sector, Norway’s real GDP growth has been sluggish at best, so that government spending depends almost exclusively on energy revenues.

House prices have rocketed along with household debt (now at a record 200% of income).

Indeed, the overall economy is slipping into recession,

as energy prices slip back.

As elsewhere, Norwegians are divided on why the economy is deteriorating. The anti-immigrant Progress Party has loudly blamed this on immigration. With one-fifth of Norway’s residents now being immigrants or children of immigrants, and record-high immigration in recent years (particularly influenced by Ukrainian refugees), local councils have expressed concerns about ‘capacity overload’ due to high immigration rates. The PP is gaining support in the opinion polls, but mainly at the expense of the traditional Conservatives.

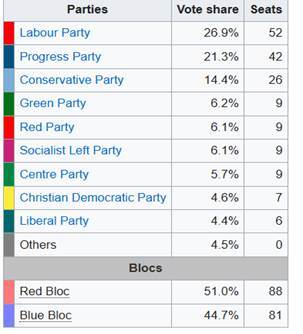

Norway has a system of proportional representation whereby 169 lawmakers are elected from 19 geographical districts for a fixed, four-year term. Any party scoring above 4% support nationwide is guaranteed representation, although a strong showing in individual districts can also yield one or more seats. No party is expected to win the 85 seats required for an outright majority, but the latest polls show that the incumbent Labour-led ‘red bloc’ will get the most votes, so minority rule under Labour or the formation of another coalition are the likeliest outcomes.

But the ‘left’ coalition is split. Labour Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Stoere’s previous coalition broke up when the rural-based Centre Party opposed adopting EU regulations on climate controls. And the Socialist Left said it would only support a future Labour government if it divested from all companies involved in what it called “Israel’s illegal warfare in Gaza”. But Labour, led by Stoere and the recently returned NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenburg, are determined to maintain their support for Israel and for the ‘coalition of the willing’ in Europe to pursue the war in Ukraine.

Norwegian capitalism has been highly successful based on fossil fuel production. But ever-increasing inequality and global warming are intensifying the contradictions in Norwegian capitalism. Can the Norwegian economy continue to grow based on fossil fuel capital? Should Norway’s billionaires continue to take the lion’s share of fossil fuel profits? What is the alternative? Norway’s voters are uncertain.

September 1, 2025

Gopinath, the IMF and ‘good policies’

In 2019, economics professor Gita Gopinath left the halls of Harvard University to become the chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Three years later, she made an unprecedented jump from economic analysis to policy management, becoming the first ever ‘deputy managing director’ — or the IMF’s effective number two – the right-hand (woman) of IMF managing director, Kristalina Georgieva. Last Friday, she left to return to academia at Harvard.

Gopinath is the epitomy of a modern mainstream economist (here is her CV). A firm believer in the capitalist system ie. economies owned and controlled by privately owned companies (mainly large but also small) that produce,invest and employ to the degree that profits are made by the owners (directors and shareholders). But within the arena of capitalism, Gopinath naturally wants to make capitalism work for all globally. She is aware of capitalism’s ‘imperfections’ and sees her role as analysing those to develop policies that can keep the ship of capitalism stable as it moves through dangerous waters.

She was interviewed by the Financial Times on the storms facing capitalism during her six years at the IMF. When Gopinath looks back, she told the FT: “2019 feels like the calm before the storm. We’ve had now multiple years of big tectonic shifts – the pandemic, war in Ukraine, the energy and cost-of-living crises, and a rise in geo-economic fragmentation.”

But Gopinath remains confident in the system: “what has been very surprising in a good way is that despite these major shocks, the global economy has been resilient.” And why is that? “In my view, the number one reason for that is that there have been good policies that have helped. The fact that they prevented a financial crisis has been critical. Because if we look at history and you see downturns or crises that have very long-lasting effects and large amounts of scarring, they’ve usually come after a big financial crisis. The fact that we’ve gone through a pandemic, war, the Federal Reserve raising interest rates sharply to fight inflation, geo-economic fragmentation, but we still haven’t seen a financial crisis, is very important to why we have not had much bigger hits to the global economy.”

Hmm… the global capitalist economy may have been ‘resilient’, in so far that there has been no financial crisis since the global financial crash of 2008, but hardly in any other criteria. The pandemic slump was the deepest (if short-lived) and widest in global impact in the history of capitalism, with virtually all the world’s economies suffering a significant downturn in national output. Gopinath sees the pandemic slump and the subsequent post-pandemic inflationary spike as ‘shocks’ that had to be ‘managed’, not as endemic recurring crises generated by capitalism itself. But there is plenty of evidence that the major economies were heading into a slump in 2019 even before the COVID pandemic erupted (and that pandemic could have been avoided if big pharma had not been deciding what vaccinations and medicines were profitable to develop and if governments had not decimated health systems with the policies of fiscal austerity).

There were permanent scars from the pandemic left on economies and on the living standards of most people globally. The pandemic slump increased global poverty levels (already high) to new heights – as another 700m fell below the World Bank’s miserably low poverty benchmark. And then the IMF and major central banks failed to spot the huge inflationary spike after the end of the pandemic caused by the disruption of global supply chains, energy company price hikes and the loss of workers in key industries. The answer of the IMF and the central banks was to hike interest rates because they (and Gopinath) thought that inflation is caused by ‘excessive demand’ or ‘excessive wage increases’. The result was a 25% rise in average prices in the major economies over the next three years to 2023, a rise that remains locked into the cost of living for most households.

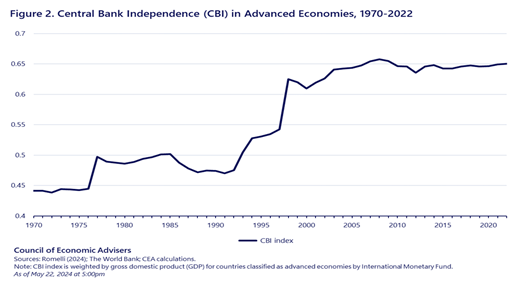

In the interview, Gopinath claims that central bank independence generally “is one of the crown jewels of good economic policy” because “independent monetary policymaking has been critical to ensuring price stability. It was critical to bringing inflation down after the post-pandemic surge without a big sacrifice in employment. The anchoring of inflation expectations was absolutely critical to that. And so I think that is a lesson we have to take away.” Here, Gopinath repeats the mainstream mantra of central bank independence (CBI) as the reason for controlling inflation and yet there is little compelling evidence for this – CBI is really protection for the financial sector from interference by governments.

Again there is no evidence that central bank ‘anchoring of inflation expectations’ brought inflation under control. Inflation rocketed post-pandemic under Gopinath’s watch and slowed later when global supply and employment recovered, not because of central banks ‘anchoring inflation expectations’. As a paper by Jeremy Rudd at the Federal Reserve concluded: “Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and firms’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors.”

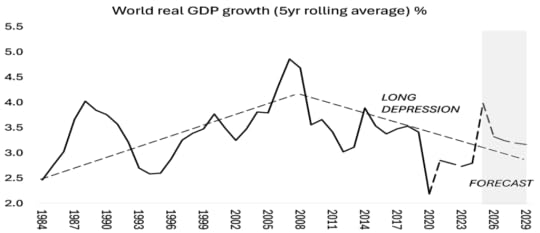

If ‘resilience’ means more than avoiding a financial crash, then the major economies have not been resllient at all. The rate of real GDP expansion since 2021 has been pathetic. The US economy is growing at about 2% a year in real terms, even lower than in the long depression years of the 2010s, but even that is better than the rest of the top G7 economies, which have stagnated with average growth rates of less than 1% a year at best. Even world economic growth (including the fast-growing large economies of India and China and non-Japan east Asia) is dropping.

Here is the World Bank view. “This year alone, our forecasts indicate the upheaval will slice nearly half a percentage point off the global GDP growth rate that had been expected at the start of the year, cutting it to 2.3 percent. That’s the weakest performance in 17 years, outside of outright global recessions… By 2027, global GDP growth is expected to average just 2.5 percent in the 2020s—the slowest pace of any decade since the 1960s.” The World Bank continues: “By 2027, the per capita GDP of high-income economies will be roughly where it had been expected to be before the COVID-19 pandemic,” (some seven years since the pandemic). “But developing economies would be worse off, with per capita GDP levels still 6 percent lower. Except for China, it could take these economies about two decades to recoup the economic losses of the 2020s.”

Gopinath says in the interview that “good policies avoided a financial crisis”. Presumably she refers here to central bank monetary injections and fiscal spending by governments during the pandemic to sustain businesses and households. However, the result of all these ‘good policies’ that staved off a financial crisis by bailing out the banks (again) and large companies is that “global [public debt] levels are now incredibly high. In 2024, they were around 92 per cent of global GDP. And as a reference, that number was 65 per cent in 2000. So there has been a very substantial increase in global debt. But even more concerning, the projection is for it to continue to increase and hit 100 per cent of global GDP in 2030.” (Gopinath). Gopinath fails to tell the FT that, in the advanced economies, the public debt ratio is even higher, at 110% of GDP this year (with the US at 125%). But she admits that the IMF’s own forecasts of the rise in public debt to GDP were too optimistic. “Ultimately debt-to-GDP is about 10 percentage points or more higher than what we projected. So this is a serious issue countries will have to grapple with.”

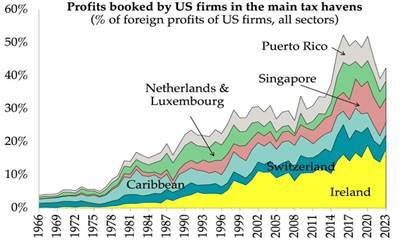

In the FT interview, Gopinath does not say why public debt has risen so much. And yet there are some obvious causes. “There is an imbalance between what is expected of the state in terms of spending and what is actually possible given the revenues being collected.” No kidding, but which is the problem: revenues or spending? The main reasons were the bailouts of the banking system in the global financial crash of 2008; the slump in the Great Recession reducing tax revenues and increasing social spending; and a similar repeat in the pandemic slump of 2020. So the public debt ratio has risen because governments borrowed more and national output growth slowed. But government borrowing also increased despite years of fiscal austerity (spending cuts) in the 2010s because tax revenues did not rise sufficiently. Governments reduced corporate profit tax rates, companies shifted their profits into tax havens, and companies and rich individuals used various tax avoidance schemes or just did not pay (huge amounts of taxes remain unpaid and uncollected).

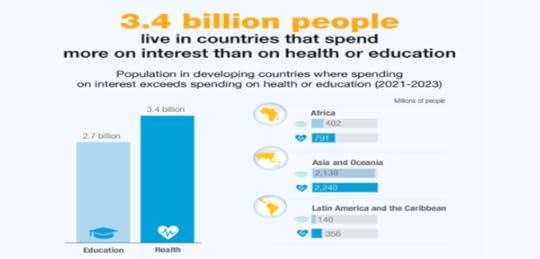

The IMF, the World Bank, the OECD and governments talk about closing down tax havens and avoidance schemes – but nothing ever happens. Meanwhile, the World Bank has presented a dismal picture of the situation for most people in the world. In 2024,“Global extreme poverty reduction has slowed to a near standstill, with 2020-30 set to be a lost decade.” Around 3.5 billion people live on less than $6.85 a day, the poverty line more relevant for middle-income countries, which are home to three-quarters of the world’s population. “Without drastic action, it could take decades to eradicate extreme poverty and more than a century to eliminate poverty as it is defined for nearly half of the world.”

The other striking omission in the interview is that Gopinath makes no mention of global warming and climate change. When she joined the IMF in 2019, there were many IMF studies on emissions mitigation, funding for renewables, and carbon pricing and taxes. Now as multi-nationals and banks have ditched all their climate policies to boost profits, the IMF is more or less silent. It is no accident that Gopinath ignores this literally burning issue for the world.

In the interview, Gopinath is more worried about the rise in public debt ratios (she seems to see this as the major problem, not what is happening with inequality, poverty or the climate). She is worried that the cost of borrowing by governments (in the West) and for companies and households will rise. Everywhere the interest costs on government debt are rising and many poor countries pay more in interest on their debts than they spend on health and education). The US government is facing a massive increase in interest costs on its burgeoning debt, especially if interest rates stay above inflation rates.

Gopinath says the problem is that “We do not have a global savings glut anymore. We do not have central banks buying large amounts of government debt. And we are seeing long-term yields . . . now back to pre-global financial crisis levels, and term premia have gone up. So that’s a second area where I think, compared to 2019.” But there never was a ‘global savings glut’. I and others have refuted this theory on several occasions. The problem was not too much savings, but too little productive investment to drive economic growth.

What Gopinath really means is that countries like the US and the UK are running twin deficits on government budgets and trade which have to be financed. Foreigners are less willing to buy the US or UK debt and their central banks are selling their holdings (quantitative tightening) and no longer buying the debt (quantitative easing). Given that inflation rates remain stubbornly higher than forecast, everywhere government bond yields are rising. So according to Gopinath, “We are certainly at a moment where, given the large amounts of government debt, the growth of non-bank financial institutions and questions about central bank independence, we could certainly push ourselves into . . . a global financial crisis. That would be something that would not be easy to recover from for the world.” It seems that the previous ‘resilience’ of capitalism in the last six years is about to crack, after all.

So what’s Gopinath’s policy answer after six years at the IMF: fiscal austerity and ‘structural reform’. Governments need to “rebuild fiscal buffers” which “will involve less spending and taking a very close look at entitlement spending, including on healthcare and social security” (!) (Even the FT interviewer recognised that Gopinath was advocating that spending “demands have to be brought into alignment with revenues rather than the other way round.”)

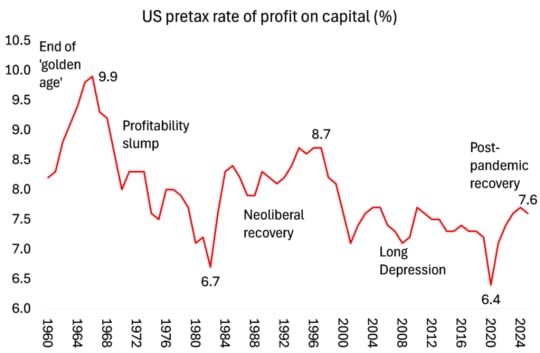

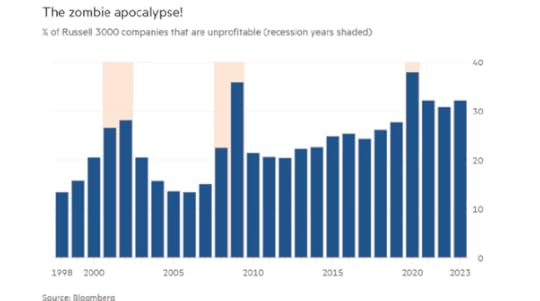

Actually the emphasis by Gopinath on rising public debt as the potential cause of a future financial crash is misguided. Public debt ratios have only risen because of the failure of the private sector to sustain sufficient economic growth and avoid too much borrowing. The average profitability of capital has fallen since its peak at the end of the 20th century and has stayed at low levels since 2019. Yes, a small number of huge tech and energy companies have made mega profits, but most companies in the US, UK and Europe have struggled – indeed, as mentioned many times before, some 20% or more companies in the major economies make no profit and are forced to borrow more to keep going. Behind the scenes, behind the banks, ‘shadow’ banks (private lenders) are propping up swathes of ‘zombie’ companies. This is where the risk of a financial crash is highest – not in public sector debt.

Gopinath is also worried about ‘global fragmentation’ – this is IMF-speak for the end of globalisation and ‘free trade’ that the world economy has experienced in the last six years (and before). She is concerned that the “the US will want to decouple from the rest of the world as that would be very costly. It is simply not possible to stop trading with the world without also ending [inflows of] finance from the rest of the world, or ending dollar dominance.” So we need to sustain all the good things of the last 40 years: free trade, free flows of capital and US dollar hegemony. “I take it as a positive sign that there is still, in many international discussions and platforms, strong support for open trade. I would expect trade to continue, but a lot will depend on making sure that domestic sentiment also aligns with keeping borders open.”

Gopinath says she has spent some time and research into the impact of AI. She reckons that about 40 per cent of the global labour force is exposed to AI. In a paper last year she argued AI could worsen any future slumps by expanding the range of jobs subject to automation, “which businesses are more keen on when times are tough.” But don’t worry, “on the positive side: good policies that were championed by the economics profession and policy institutions — independent monitoring, financial supervision and regulation, timely fiscal support — all of that has delivered a global economy that is resilient to big shocks.”

Really? If so, then the general public seems ungrateful for the ‘good policies’ suggested by the IMF and the mainstream economics profession – and followed slavishly by centrist and social democratic governments for decades . As Gopinath admits, these “good policies of trade integration, central bank independence and fiscal prudence” of which “there was broad consensus in the profession” seem to “have generated some kind of a trust deficit with the economics profession.” There“have been blind spots” in economic analysis, so trust in mainstream economics is “not something we can take for granted, as we might have done in the past.” Indeed. Anyway, Gita Gopinath is going back to academia to train a new generation of economists in those ‘good policies’.

August 27, 2025

Should central banks be ‘independent’?

US President Donald Trump announced that he had fired Lisa Cook, a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Trump says that she committed mortgage fraud by taking out two mortgages, claiming both properties as her primary residence, back when she was a professor at Michigan State, before joining the Fed. Naturally, Cook dismissed these charges, and as Keynesian economist Paul Krugman said on his blog, “Even if true, this accusation wouldn’t meet the standard for immediate dismissal from the Fed.”

What’s behind all this? Trump and his MAGA advisers are determined to take control of the Federal Reserve and end its relative ‘independence’ from politicians. Trump wants the Fed to cut its ‘policy interest rate’ to at least 1% from its current level of 4%-plus and he wants the Fed to be at his beck and call over monetary policy and financial deregulation. Trump has called Fed chair Powell a “numbskull” and “stubborn mule” for refusing (so far) to accede to his demands to slash rates. Trump’s treasury secretary Scott Bessent likened Fed staffers to beneficiaries of “universal basic income for academic economists”. All these PhDs over there, I don’t know what they do.” Trump has already got one of his MAGA supporters on the Fed board (former White House chief adviser, Stephen Miran) and replacing Cook would get him closer to controlling the Fed – especially as Powell ends his term next year. Bessent is favourite to replace him.

Financial investors and mainstream economists like Krugman are shocked at Trump threatening ‘central bank independence’. This has been the mainstream mantra of the last 40 years. David Wessel, director of the Hutchins Center for Fiscal and Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution, warned: “President Trump seems determined to control the Fed — and will use any lever he has to get a majority on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors,” he said. “This is one more way in which the president is undermining the foundations of our democracy.”

But are the Federal Reserve and all the other ‘independent’ central banks globally part of “the foundations of our democracy”? Actually, the Fed is a very undemocratic institution. American households have no say in who is appointed and what the board members decide. So why the strong support for central bank independence (CBI) among mainstream economists, financial investors, banks and politicians? Apparently, CBI provides an objective ‘neutral’ base for monetary policy uninfluenced by dangerous political forces (like democratically elected officials?) with appointees who have unparelled ‘expertise’ in monetary economics and policy. As neoliberal economist John Cochrane put it: “The veneration of independence also has intellectual roots in an era when people distrusted “politicians” despite their democratic accountability, and instead trusted disinterested technocrats.”

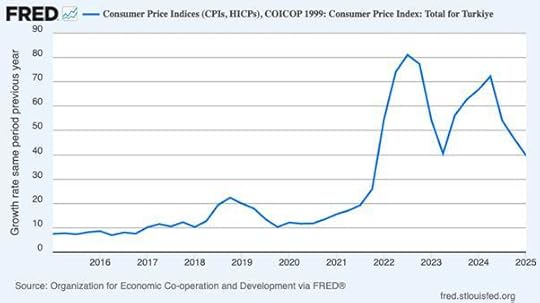

The usual contemporary example of what happens when a central bank comes under the control of an elected president is Turkey, where President Erdogan continually sacked central bank governors until they did his bidding to cut interest rates. The result, according to the mainstream economists was rampant inflation. Krugman gives us Turkey’s inflation rate under Erdogan.

But was Turkey’s 40-50% a year inflation due to low interest rates or due to its chronically huge current account deficits that drove down the Turkish lira against the euro and the dollar -and also Erdogan’s political moves to suppress opposition forces in the country, Trump style? Turkey’s current account and trade deficit relative to GDP more than doubled during the Erdogan years.

Central bank independence (CBI) mushroomed in the neo-liberal period after the stagflationary 1970s. CBI was a part of neo-liberal economic policy, which aimed to get government out of the ‘managing the economy’ Keynesian style and instead allow free markets and deregulation of finance, in particular. Since the 1990s, in particular, CBI has become “accepted wisdom of modern economics” (Cochrane).

All the great and good of financial institutions now praise the need for CBI. Take the IMF. The IMF’s Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said it clearly earlier this year, when she noted that “independence is critical to winning the fights against inflation and achieving stable long-term economic growth.” She claimed: “Just consider what independent central banks have achieved in recent years. Central bankers steered effectively through the pandemic, unleashing aggressive monetary easing that helped prevent a global financial meltdown and speed recovery.” And “central bank actions have brought inflation down to much more manageable levels and reduced the risks of a hard landing.”

Georgieva cited one IMF study, looking at dozens of central banks from 2007 to 2021, which showed that those with strong independence scores were more successful in keeping people’s inflation expectations in check, which helps keep inflation low. Another IMF study tracking 17 Latin American central banks over the past 100 years examined factors including: decision-making independence, clarity of mandate, and whether they could be forced to lend to the government. It also found that greater independence was associated with much better inflation outcomes. “The bottom line is clear: central bank independence matters for price stability—and price stability matters for consistent long-term growth.”

But are these claims valid? Correlation is not causation, as we know. The period from the 1990s through the 2010s was one of falling global inflation anyway as economies grew more slowly. Global consumer price inflation fell from a peak of 16.9 percent in 1974 to 2.5 percent in 2020. As the World Bank explains: “Global inflation fell sharply (on average by 0.9 percentage points) in the year to the trough of global recessions and continued to decline even as recoveries got underway. Conversely, persistently below-target inflation has accompanied weak growth in advanced economies since the 2007–09 global financial crisis.”