Michael Roberts's Blog, page 4

June 16, 2025

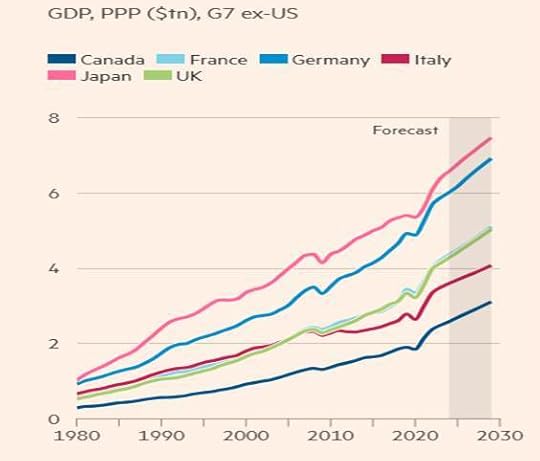

From the Rockies to Stockholm: ignoring the global crisis

As I write, the government leaders of the Group of Seven (G7) countries – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the US – are meeting in the remote town of Kananaskis, Alberta, in the foothills of the Canadian Rockies, for intense discussions. This will be the 51st summit meeting of the top seven capitalist economies. The G7 still represents 44% of world’s GDP, but now only 10% of the world’s population. Yet the G7 and some of its smaller partners constitute the imperialist core, the so-called Global North, that rules the world.

What are the G7 leaders discussing? Naturally, it is the accelerating Middle East crisis after the Israeli attack on Iran; the continued war in Ukraine and the need for more sanctions on Russia and arms for Ukraine; what to do about Trump’s trade tariffs; how to impose a range of cuts in international aid to poor countries by most G7 governments in order to make room for increased arms spending; and the need for a common policy against China.

At the same time as the G7 meeting of governments, in Sweden, a bunch of tech billionaires, prime ministers, corporate titans and the king of the Netherlands have convened in Sweden for the 71st Bilderberg meeting at the swanky Grand hotel in Stockholm, owned by Sweden’d longstanding oligarchs, the Wallenberg family.

The Bilderberg group is a secretive conclave where the movers and shakers of world capitalism can discuss privately the strategies and policies needed to preserve the system, ie imperialism. At this meeting will be the heads of Nato and MI6, and two of America’s most senior military officers in the room along with the CEOs of several major ‘defence’ suppliers such as Palantir, Thales and Anduril. The host of the conference, Marcus Wallenberg, runs his own arms company, Sweden’s largest defence contractor, Saab.

The main discussion for the Bilberberg participants is how to strangle economically, politically and militarily, China. As the American MAGA Republican Jason Smith put it: he was in Sweden to “continue fighting to combat the economic and national security threat China poses to our great nation”. Fellow Bilderberg attendee Robert Lighthizer, economic adviser close to Trump, echoed that sentiment: “China to me is an existential threat to the United States”.

But here is the rub. There are two great issues that it seems neither the G7 leaders nor the Bilderberg bruisers will be discussing, obsessed as they are with the perceived geopolitical threats posed by the ‘resistant’ powers of Russia, Iran and China. There will be little or no discussion of the deteriorating economic landscape of the global economy, including the major economies of the Global North; nor will there be much discussion about the existential threat to economies and peoples from global warming and climate change. In the latter’s case, it is increasingly clear that governments and Bilderbergs have given up; they prefer to make profits in a fossil fuelled world while the going is good.

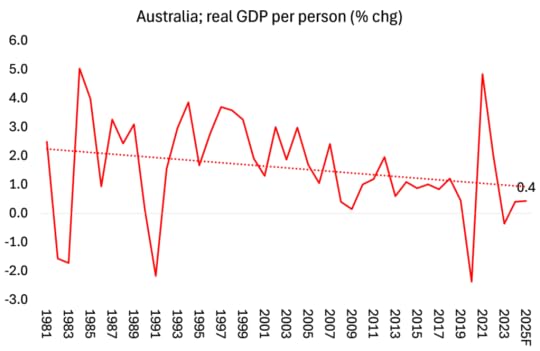

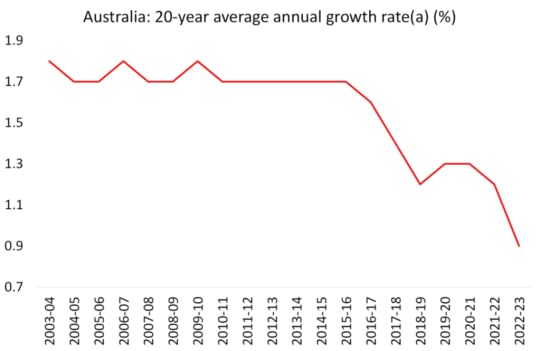

Yet these are the two issues that are likely to undermine all the efforts of the rulers of the Global North economies. The major economies are in increasingly deep trouble. This is made clear in the latest deeply dismal report from the World Bank on global economic prospects. As the report put it: “This year alone, our forecasts indicate the upheaval will slice nearly half a percentage point off the global GDP growth rate that had been expected at the start of the year, cutting it to 2.3 percent. That’s the weakest performance in 17 years, outside of outright global recessions… By 2027, global GDP growth is expected to average just 2.5 percent in the 2020s—the slowest pace of any decade since the 1960s.”

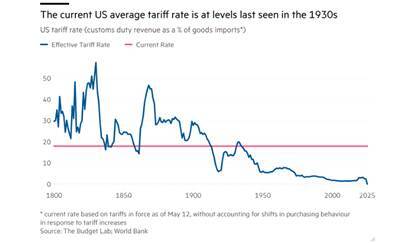

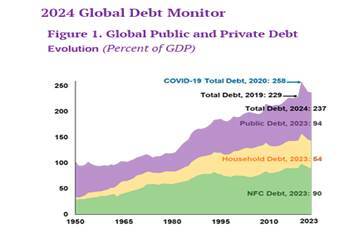

The World Bank makes the point that this slowdown is not new. “Growth in developing economies has now been ratcheting downward for three decades in a row—from an average of 5.9 percent in the 2000s to 5.1 percent in the 2010s to 3.7 percent in the 2020s. That happens to track the declining trajectory of growth in global trade—which has fallen from an average of 5.1 percent in the 2000s to 4.6 percent in the 2010s to 2.6 percent in the 2020s. Investment, meanwhile, has been growing at a progressively weaker pace. But debt is piling up.”

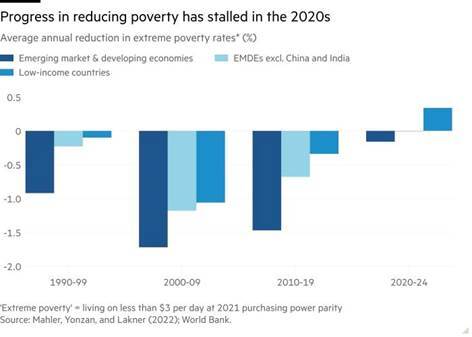

The World Bank goes on: “The poorest countries will suffer the most. By 2027, the per capita GDP of high-income economies will be roughly where it had been expected to be before the COVID-19 pandemic. (That’s not saying much – MR). But developing economies would be worse off, with per capita GDP levels 6 percent lower. Except for China, it could take these economies about two decades to recoup the economic losses of the 2020s.” In other words, far from the poorest countries making any progress in improving living standards for these most populated places, these countries are dropping further behind. Poverty rates (even those unrealistically set by the World Bank) are rising.

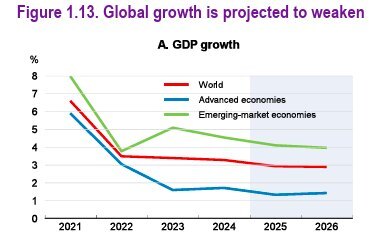

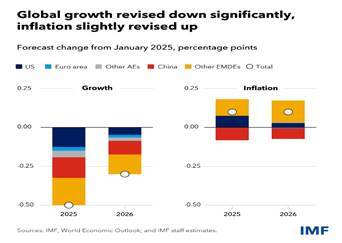

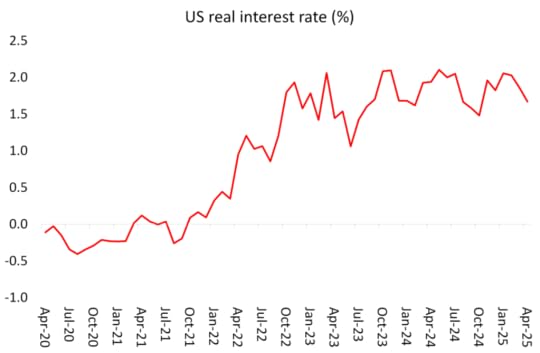

The OECD, the agency for the Global North economies, in a new report, echoes the World Bank’s depressing analysis. According the OECD’s latest economic outlook, the global economy is heading into its weakest growth spell since the Covid-19 slump. “Weakened economic prospects will be felt around the world, with almost no exception.” And that includes the leading imperialist power. The OECD forecasts that US growth will slow particularly sharply, from 2.8 per cent in 2024 to just 1.6 per cent in 2025 and 1.5 per cent in 2026, while US inflation is expected to rise to nearly 4 per cent by the end of 2025 and remain above the Fed’s target in 2026, meaning the US central bank will not cut rates to ease the debt burden on households and small companies.

Elsewhere, Chinese real GDP growth will slow from 5 per cent in 2024 to 4.7 per cent in 2025 (still some three times faster than the US) and 4.3 per cent in 2026, while the Eurozone will expand by just 1 per cent this year and 1.2 per cent in 2026. Japan’s economy will grow by just 0.7 per cent and 0.4 per cent this year and next respectively. The UK economy is predicted to expand by 1.3 per cent this year, but just 1 per cent in 2026. And all these forecasts exclude the long-term impact of Trump’s tariffs.

Global trade will expand by 2.8 per cent in 2025 and 2.2 per cent in 2026, sharply lower than OECD predictions in December. And fiscal risks are rising along with trade tensions, the OECD warned, with demands for more defence expenditure set to add to spending pressures.

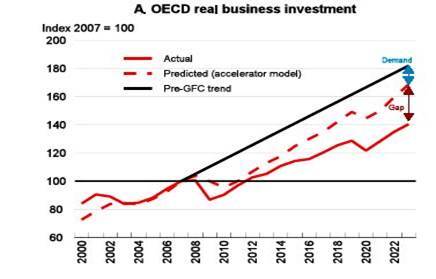

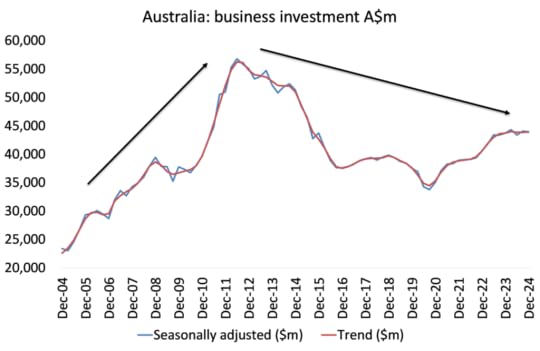

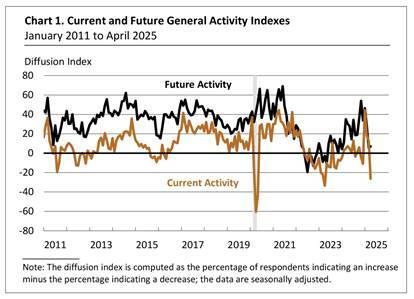

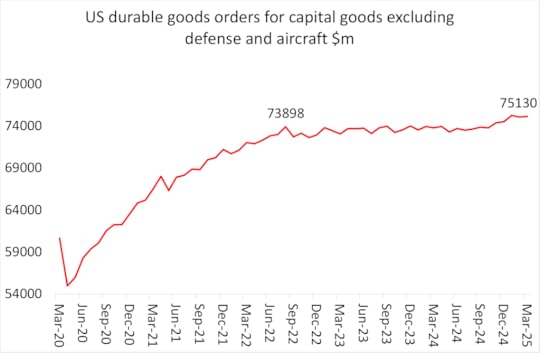

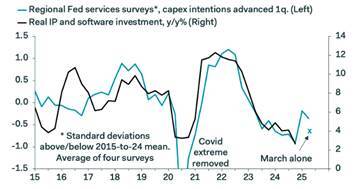

Behind the slowdown in national output growth is the further weakening of productive investment growth.

Those readers who have followed my thesis of a long depression in the world capitalist economy for the last 18 years will recognise the ‘inverted square root’ trajectory of investment since 2008. After each crunch or crisis in accumulation (2008 and 2020), the major economies have not restored the previous rate of business investment growth.

The OECD sums it all up. “Historically elevated” equity valuations are increasing vulnerabilities to negative shocks in financial markets. A long spell of weak investment has compounded the longer-term challenges facing OECD economies, and this is further sapping the growth outlook.” Meanwhile, “despite rising profits, firms have shied away from fixed-capital investment in favour of accumulating financial assets and returning funds to shareholders.”

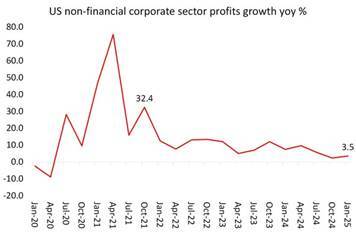

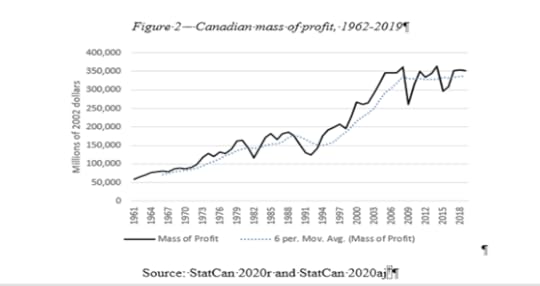

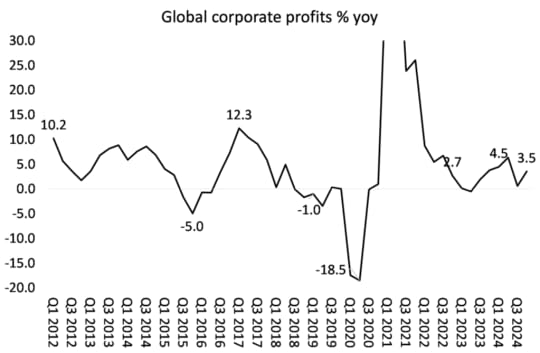

While the leaders and strategists of global capitalism meet in Canada and Sweden to discuss how to handle Russia, China and Iran, the immediate economic picture in their own economies is getting bleaker. According to the second estimate for the first quarter of 2025 US real GDP fell 0.2% compared to the last quarter of 2024. Most worrying, corporate profits fell 2.9% qoq, while non-financial corporate profits fell 3.5% on the quarter. Profits growth is slowing…

… and profit margins (sale price minus costs per unit) have now peaked.

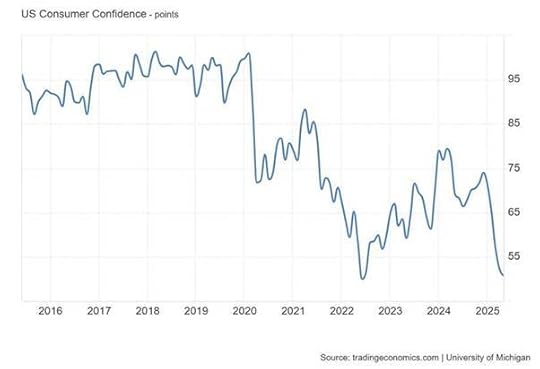

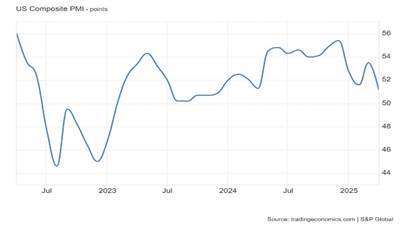

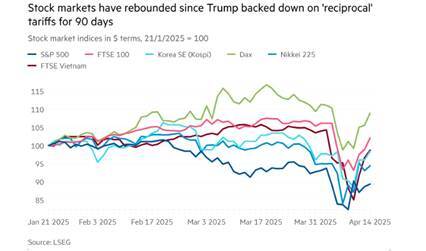

The US economy is not yet in a recession but if company profits slow further or fall, then investment will eventually follow. JP Morgan economists warn of stagflation ahead for the US economy. Stagflation, a term from the 1970s, is when national output is stagnant, but inflation stays high and even rises – the opposite of Keynesian theory. JPMorgan equity strategists wrote: “After the recent rebound, we believe weakness will follow, which may resemble the stagflation period, during which trade negotiations are expected to conclude.” Consumer confidence has remained weak: “The past practice of placing orders in advance on the eve of tariff hikes may have paid off, but with purchasing power being squeezed, consumers’ purchasing power will weaken. Even with a significant pullback, the current tariff situation is worse than what most people expected at the beginning of the year.”

In JPMorgan’s view, higher input costs and interest expenses will erode profit margins and so corporate earnings growth for S&P 500 companies may drop sharply and the US economy will stagnate. This is something I predicted in a post last February, a whiff of stagflation.

And the economic activity indicators for the other major G7 economies show that they are already either stagnating or in recession. May’s Eurozone composite PMI indicated that both the services and manufacturing sectors of the region were contracting, the latter at its lowest in three years. The region’s contraction was led by France (now nine months of decline) and Germany (where the services sector dropped at its fastest pace in over two years). The UK also continued to contract, driven by a manufacturing sector at its lowest in 19 months.

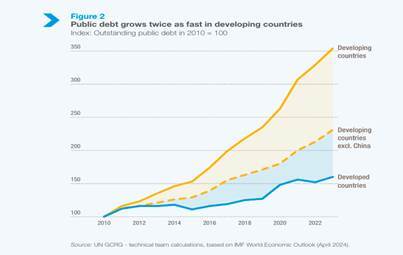

So the situation for the Global North economies is worsening. But it is nothing to the unending distress of the poorest economies in the world, where the bulk of humanity tries to make a living. The debt burden (the ratio of debt to GDP owed to banks and governments around the world) for these countries continues to rise.

Total debt in the so-called emerging markets (EMs) excluding China rose by 3 percentage points of GDP in 2023 to reach 126 percent of GDP. Debt in low-income developing countries (LIDCs) also increased and is above pre-pandemic levels. Debt repayments are now greater than new inflows of credit and capital. In 2023, low- and middle-income countries (excluding China) experienced a net outflow to the private sector of $30bn on long-term debt — a major drain on development. The total debt servicing costs (principal plus interest payments) of all LMICs reached an all-time high of US$1.4 trillion in 2023. Excluding China, debt servicing costs climbed to a record of US$971 billion in 2023, an increase of 19.7 percent over the previous year and more than double the amounts seen a decade ago. Total external debt stock of the poor countries hit at an all-time high of 8.8 trillion in 2023, up 2.4 percent from the previous year.

The World Bank in its latest international debt report does not shirk the reality. World Bank chief economist Indermit Gill put it starkly: “Large ongoing debt service burdens, especially in the public component of debt, accompanied by the expected fiscal tightening, could force some LMICs to spend less on other priorities, including social safety nets and public investment in physical and human capital.” Gill continues: “A decade ago, in an era when private capital was gushing into developing economies, governments and development institutions figured it was exactly what was needed to turbocharge progress on poverty reduction and other development goals. “The good news is that, globally, there are ample savings, amounting to US$17 trillion, and liquidity is at historical highs,” read a key World Bank strategy document of the time. That proved to be a fantasy. Since 2022, foreign private creditors have extracted nearly US$141 billion more in debt service payments from public sector borrowers in developing economies than they disbursed in new financing. For two years in a row now, the external creditors of developing economies have been pulling out more than they have been putting in.”

Gill sums up the state of foreign ‘aid’ and credits from the Global North’s banks and investment bodies to the governments and private sector of the Global South. “It reflects a broken financing system.” In 2023, developing countries spent a record $1.4 trillion just to service their debt. That amounted to nearly 4 percent of their GDPs. Ballooning interest payments accounted for most of the increase in overall debt service payments, surging by more than a third to about US$406 billion.

Recent data from the UN’s trade and development body, UNCTAD, reveal that 54 countries spend over 10 percent of their tax revenues on interest payments alone. The average interest burden for developing countries, as a share of tax revenues, has almost doubled since 2011. More than 3.3bn people live in countries that now spend more on debt service than on health, and 2.1bn in countries that spend more on debt than on education.

Gill again: “The result, for many developing countries, has been a devastating diversion of resources away from areas critical for long-term growth and development such as health and education. The squeeze on the poorest and most vulnerable countries has been especially fierce… more than half these countries are either in debt distress or at high risk of it. No wonder that private creditors have been retreating…. It is easy to kick the can down the road, to provide these countries just enough financing to help them meet their immediate repayment obligations. But that simply extends their purgatory.”

Gill: “These countries will need to grow at a faster clip if they are to shrink their debt burdens—and they will need much more investment if growth is to accelerate. Neither is likely, given the size of their debt burdens: their ability to repay will never be restored. It’s time to face the reality: the poorest countries facing debt distress need debt relief if they are to have a shot at lasting prosperity.” But no ‘debt relief’ is on the agenda of the Rockies or Bilderberg.

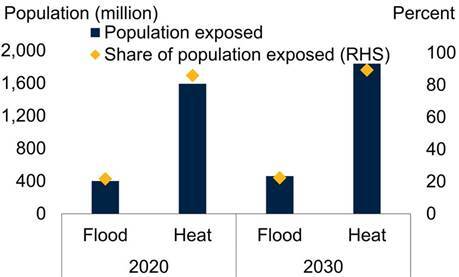

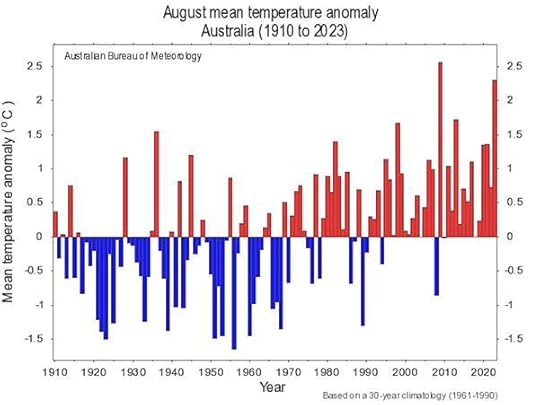

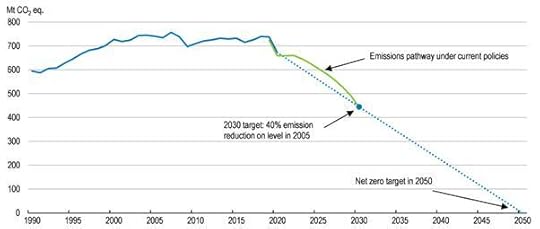

And then there is global warming and climate change. Global warming is accelerating. New climate predictions have found a 70% chance that global temperatures will exceed 1.5C above pre-industrial levels as average over the next five years. And there is an 80% chance that at least one year between 2025 and 2029 will set a new record for global temperatures, the analysis shows. And for the first time, climate models have shown there is a possibility that the world’s global average temperature could exceed 2C above pre-industrial levels before 2030.

US president Trump may consider that climate change is a myth. The World Bank does not think so. The World Bank warns of a climate emergency for 1.8 billion people in South Asia as the heat crisis looms. It has issued a stark warning on the growing threat of extreme heat in South Asia, projecting that nearly 1.8 billion people, roughly 89% of the region’s population, will be exposed to dangerous temperatures by 2030. “In 2021 alone, countries like Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka saw average daily conditions that were too hot for safe outdoor work for about six hours,” the report noted. That figure is expected to rise to seven or eight hours a day by 2050, threatening both livelihoods and health. According to the World Bank, over 60% of households and firms in the region have experienced extreme weather in the past five years and more than 75% expect such events to increase in the next decade.

A significant economic slowdown into stagnation, alongside still relatively high inflation; a crippling debt burden for the majority of the world’s population eking out a bare living; and an accelerating climate crisis – none of these issues will be discussed in the Rockies or in the Grand Hotel in Stockholm.

June 9, 2025

Bancor

US President Donald Trump’s trade war has forced the governments of the other major economies to reconsider the whole international trading and monetary regime. The international trading ‘rules’ built up over the last 40 years of so-called globalisation have been wrecked and the international institutions (the IMF, World Bank, UN) formed after WW2 by the US (with the support of the UK) at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, along with the World Trade Organization (WTO) have been sidelined.

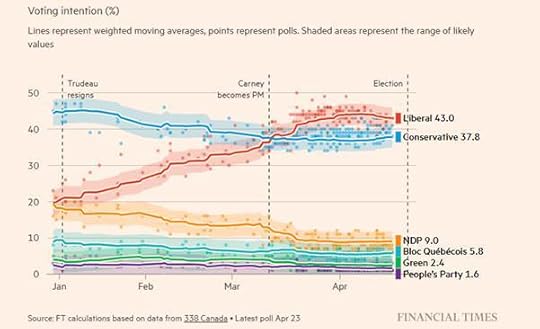

Last week, the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the think-tank of the top 30 advanced capitalist economies, met in Paris for its annual meeting. It was a sombre affair. Trump’s unilateral action on tariffs and his attempt to compel countries to cut trade deals had rattled the attendees. Trump is suggesting that the international trade does not require multilateral agreements or agencies to function or as a means to settle disputes. According to the Financial Times, the US message was unmistakable: ‘We’ve got a big trade deficit we need to deal with; what matters is unilateral power, which we have,” said a diplomat who attended meetings with the US trade representative Jamieson Greer. “This is the way the world is going to look, so you better get used to it.”

Interestingly, many leftist economists have increasingly begun to accept that Trump and the US have a point: international trade and financial ‘imbalances’ (ie surpluses and deficits, credits and debits) are bad news for capitalism and maybe it is time to end them. You see, crises in capitalism are not caused by falls in the profitability of capital or even by ‘excessive debt’ in any one country, but instead by international imbalances: some countries run too large surpluses on trade with others and some countries have too large deficits.

Robert Skidelsky, Keynes’ authorative biographer, writing just after the end of the Great Recession put it thus: “global imbalances played a part in causing the severe credit crunch of 2008-9. But they are also dangerous per se. They can lead to disorderly reversals triggered by large capital movements; and they can also provoke trade restrictions. It is a fair bet that a continuation of the global imbalances of 2006 would have led to a dollar crisis or a protectionist frenzy if the credit bubble had not imploded first. The imbalances have now decreased but could open up again when the world economy recovers. They thus continue to be a serious potential problem.”

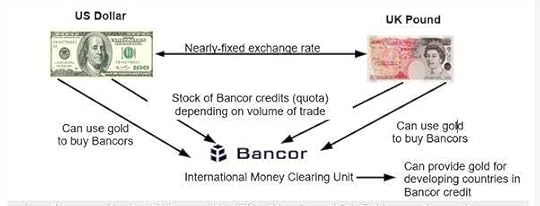

Now the Keynesian left have attempted to revive the long forgotten idea of Keynes made in 1941 that governments should establish an international ‘clearing house’ for countries where any trade surpluses or deficits are converted into credits and debits measured in a unit of international currency – named a ‘bancor’. Such a clearing house would enable global economic stability in contrast to Trump’s anarchic trade war. The “principal object” of the international clearing union, Keynes said, “can be explained in a single sentence: to provide that money earned by selling goods to one country can be spent on purchasing the products of any other country. In jargon, a system of multilateral clearing.” This would eliminate the need for bilateral clearing between countries. Instead, all national central banks would hold an account in bancors at this International Clearing Union (ICU) for their country’s surpluses or deficits.

The essential feature of Keynes’ plan was that creditor countries would not be allowed to hold on to the money from their outstanding trade surpluses, or charge punitive rates of interest for lending them out; rather these surpluses would be automatically available as cheap overdraft facilities to debtors through the mechanism of the ICU. Each national currency would have a fixed but adjustable relation to a unit of bancor, which itself would have a fixed relationship to gold as the internationally accepted measure of value.

Persistent trade surplus/creditor countries would be required to try and reduce their surpluses by revaluing their currencies and unblocking any foreign-owned investments. To force this, the ICU would charge them rising rates of interest on credits (surpluses) running above a certain level above an agreed quota. Any credit balance exceeding the quota at the end of a year would be confiscated and transferred to a Reserve Fund at the ICU. At the other side of the equation, persistent deficit countries would be required to depreciate their currencies and prohibit capital exports. They would also be charged interest on excessive debits (deficits) above a certain level. The target would be to achieve a perfect balance in trade for all countries at the year’s end with the sum of bancor balances (credits-debits) at exactly zero.

Keynes pointed out a problem with trying to achieve an international balance of trade. In ‘free markets’, any trade adjustment was “compulsory for the debtor but only voluntary for the creditor”. If the creditor does not choose to make, or allow, his share of the adjustment, he suffers no inconvenience: while a country’s reserves cannot fall below zero, there is no ceiling that sets an upper limit. The same is true if private capital flows are the means of adjustment. “The debtor must borrow; but the creditor is under no…compulsion [to lend]”.

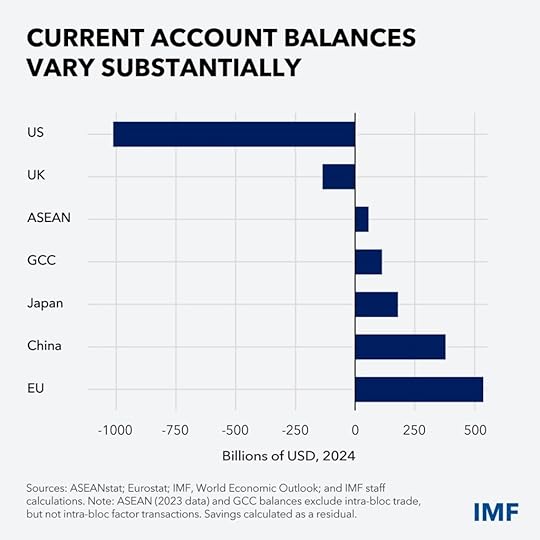

This is a problem indeed. Why should countries making trade surpluses in goods and services relinquish those monetary gains to some international clearing bank that will pass them onto those countries running deficits in order to reduce international capital flows that (apparently) are the cause of crises in production and investment globally? At Bretton Woods in 1944, the US was the major surplus creditor and the US representative Harry Dextor White vetoed Keynes’ Bancor plan. Now in 2025, it is China and Europe that are the surplus creditors and the US is the huge deficit nation. But would Trump or China support losing control over the distribution of the income from trade to an international bank run by some supposedly neutral group of bureaucrats?

At Bretton Woods, White meets Keynes

In 2025, both Trump and the Keynesians accept that imbalances in trade must be eliminated; Trump because he wants to sustain the global dominance of the American economy and its multi-national companies in world markets and the Keynesians because they think international trade and monetary imbalances are the cause of global economic instability.

Some Keynesians go so far as to accept the argument of Trump’s MAGA advisers that surplus trade countries, China in particular, are the culprits in this international instability. Michael Pettis argues that the likes of China have established trade surpluses because they have “suppressed domestic demand in order to subsidise its own manufacturing”, and so forcing the resulting the manufacturing trade surplus “to be absorbed by those of its partners who exert much less control over their trade and capital accounts.” So it is China’s (or until recently Germany’s) fault that there are trade imbalances, not the inability of US manufacturing to compete in world markets compared to Asia and even Europe.

Back in 2010, Skidelsky argued that “emerging countries (China – MR) that have discovered the advantages of export-led growth. This strategy has yielded many benefits for these countries but it suffers from a fallacy of composition; the export surpluses must have counterpart deficits elsewhere.” In other words, China’s surpluses have caused the US deficit and China’s high savings have caused too much consumption in the US. Skidelsky: “This is certainly a plausible description of events in the middle of this decade: the “glut” of savings in parts of the world evoked a Keynesian expansionary response in the US, which widened global imbalances. Of course, the day of reckoning has to come in the end and has the potential to be strongly deflationary for the world since the burden of adjustment would fall on the deficit countries.”

Skidelsky is really saying is that capitalist market economies do not grow in any harmonious and balanced way – on the contrary, there is continual competition between ‘hostile brothers’ in global markets. Just as in domestic markets, the stronger, the better organised, and those with more productive technology, gain at the expense of the weaker. Imbalances are the stuff of capitalist accumulation. The idea that ‘imbalances’ can be ironed out through some macro-management organised by a central bank has not worked within countries; and it is even less likely in international markets. International imbalances are the symptom or result of the uneven development of many capitals competing against each other; they are not the cause of economic crises

Indeed, Skidelsky hinted at this. “There are both “good” and “bad” imbalances. On the one hand, the advantage of globalisation is that it allows savings to flow to where the rate of return on new investment is highest. On the other hand, imbalances can be a symptom of distortions to the price signals in the economy, leading to unsustainable patterns of capital flows and spending that are costly to correct.” That sums up the uneven basis of capitalist economic development. That uneven development in profitability would not disappear even if each country’s trade in goods and services was in balance with all others. There would still be an unequal exchange of value in trade, as the higher technology economies and companies extracted surplus value from lower technology countries and companies. The value dimension of international imbalances is totally missing from Keynesian theory.

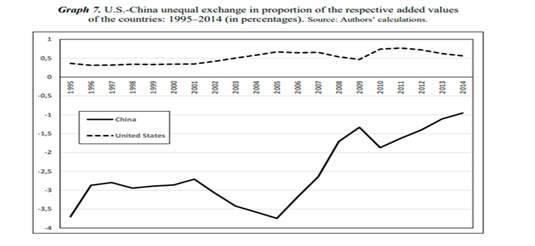

Under capitalism, there are always value imbalances among economies, not because the more efficient producer is ‘forcing’ a trade deficit on the less efficient, but because capitalism is a system of uneven and combined development, where national economies with lower costs can gain value in international trade from those less efficient. What really worries the US capitalists (and Trump in his own way) is not that surplus countries are forcing the US to issue dollars to pay for its deficits; it is that China is closing the gap on productivity and technology with the US and so reducing the transfer of profit to the US and threatening the economic dominance of the US (see this value transfer graph below).

See: https://hal.science/hal-04367750/document

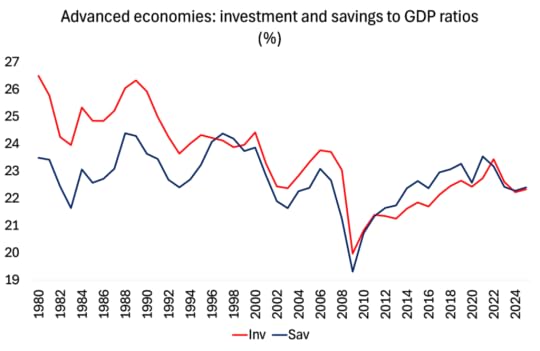

It is the same thing with the ludicrous but continually repeated argument that the slowdown in economic growth in the major economies is caused by the surplus countries ‘saving too much’. If their households, companies and governments only spent more (consume, not save), the argument goes, then the imbalances would disappear and the world economy would grow faster. But it is not excessive saving by the emerging economies that is the cause of slowing economic growth in the major economies, but too little investment in the latter.

There has not been a global savings ‘glut’, but a dearth of investment. There is not too much profit (surplus savings), but too little investment. Since the 1980s, the capitalist sector in the advanced capitalist economies (OECD) has reduced its investment relative to GDP by 4%pts, and particularly since the late 1990s and after the end of the Great Recession. Savings to GDP in the advanced economies fell only 1%pt over the same period.

Source: IMF

As profitability fell in the late 1990s, investment declined and growth had to be boosted by an expansion of fictitious capital (credit or debt) to drive consumption and unproductive financial and property speculation. The reason for the Great Recession and the subsequent weak recovery was not a lack of consumption or a savings glut, but a collapse in investment.

Back in 2011, just after the end of the Great Recession, the then governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, argued that “there is no world government to impose “rules of the game” to internalise the externalities” (ie remove the imbalances – MR). So the solution can be found only in cooperation between nations. ….Will we create a more stable world economy? The next few years will provide the answer. And they will, as our Chinese friends say, be interesting.”

Well, we now know the answer to that question. What country is going to agree to be fined or have its hard earned export money confiscated because it has succeeded ‘too well’ in world markets? The Chinese? And what country is going to accept that it will be fined or forced to devalue its currency because it is running too larger a trade deficit? The US?

Far from international cooperation looking to end trade imbalances, the major economies are facing an all-out trade war (to go along with their increasing preparations for a military war). How did the OECD annual meeting conclude on the chances of such international cooperation? “We’re really where we were before the meeting, which is nowhere,” said the head of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The utopian idea of Bancor was vetoed in 1941; and if raised again by Keynesians now, it will suffer the same fate.

June 1, 2025

South Korea: under pressure

South Korea goes to the polls on Tuesday to elect a new president after some tumultuous months following the attempted coup by the right-wing president Yoon Suk-yeol to arrest opposition leaders and close down parliament, where Yoon did not have a majority. Eventually, Yoon was impeached and arrested and is awaiting trial, despite vigorous efforts by his party to keep him in office.

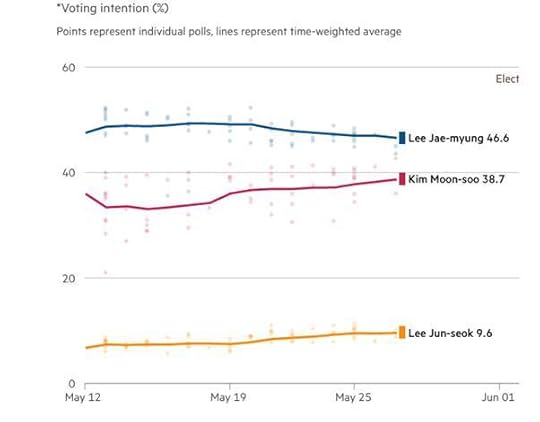

The opposition Democratic party leader Lee Jae-myung is ahead in the polls over the new conservative candidate replacing Yoon, Kim Moon-soo. Having lost narrowly to Yoon in the 2022 presidential election (by just 0.7 per cent of the vote), Lee has since survived an assassination attempt when he was stabbed in the neck in 2024. Lee originally positioned himself as an anti-elitist, working-class hero aiming to create jobs and a ‘fair society’. Lee grew up in poverty and suffered permanent injury at the age of 13 when his arm was crushed in a machine at the baseball glove factory where he worked. In the 2022 election campaign, he declared his ambition to be a “successful Bernie Sanders”. Subsequently, the ruling elite tried to suppress his rise. Lee now has convictions for drink driving and there is a long-running investigation into a controversial property development during his time as a city mayor. Current cases against him include indictments for misuse of public funds, making false statements during an election campaign, and involvement in an alleged scheme to siphon money to North Korea through an underwear manufacturer in order to win an invitation to Pyongyang!

Complicating the vote somewhat is the rise of a neo-liberal conservative candidate Lee Jun-seok, 40. He is a Harvard graduate who once served as the youngest ever chair of Yoon’s party, but broke away and is now polling in third place. This Lee wants to deregulate the economy and reduce government to boost businesses.

During the election campaign leftist Lee has muted his firebrand image and moved to the centre, even describing himself as a “conservative” to appeal to ‘moderate’ voters. He has emphasised “corporate growth” and conceded that longer working hours may be necessary in some sectors. As a result, his lead in the polls has narrowed, although he still looks set to win.

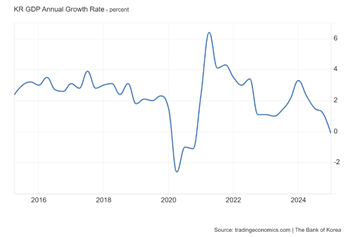

If Lee Jae-myung wins the presidency, as seems likely, his administration faces serious economic challenges. Korea is Asia’s fourth-largest economy, but real GDP contracted in the first quarter of this year as exports and consumption stalled, amid fears over the impact of Washington’s aggressive tariffs as well as the political turmoil at home. Korea has been in trade talks with the US and is seeking a waiver from Trump’s tariffs, as Trump pressures Seoul to resolve the large trade imbalance with the US.

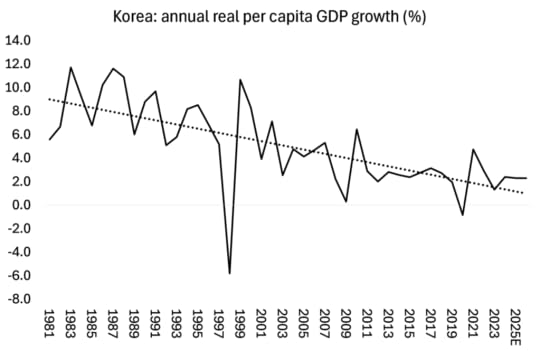

The recent political crisis is the consequence of the demise of Korean capitalism in the 21st century. Korea is supposedly an economic success story for capitalism, with economic growth averaging 5.5% since 1988, led by annual export growth of 9.3% a year. Korea’s GDP per person has risen from just US$67 in the early 1950s to $34,000 in 2019. But the slowdown in investment and productivity since the Great Recession has been visible. Labour productivity rose at an average annual rate of 5.5% in 1990-2011, but it has stagnated since then. Labour productivity is particularly low in the service sector—half that of manufacturing and much lower in smaller companies.

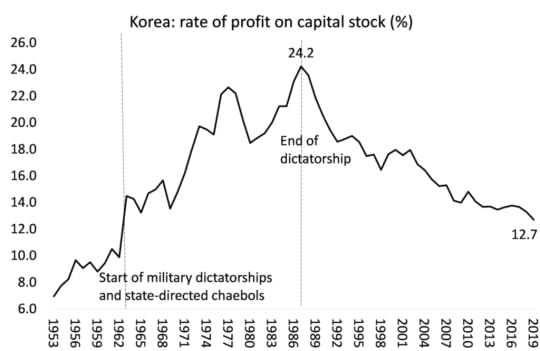

Behind the productivity and investment growth slowdown in the 21st century is the secular fall in the profitability of capital. Since the end of the military dictatorship in the mid-1980s which suppressed labour organisations and wages, the profitability of Korean capital has steadily fallen as Korean capital was forced into concessions. Korea’s past economic success had depended on a state-directed industrialisation and export strategy through close connections between the state and the chaebols (Korea’s version of family owned companies like Samsung etc).

Korea weathered the COVID-19 pandemic comparatively well, supported by a reasonably effective public health response. As a result, Korea’s economic contraction in 2020 was smaller than in most other advanced economies, with real GDP declining only by 1%. But the economy has slowed to an average of just 2.3% a year since, as the pandemic left economic scarring, namely weakened corporate profitability weighing on investment and job creation; subdued employment due to the high number of labour force exits; and poor productivity growth.

Source: IMF

Korea’s oligarchs remain at the top of the economic structure. The World Inequality Database shows that the top 10% of Koreans by income have increased their share of income and sharply raised their share of household wealth (property and financial assets). In the last five years, that story has not really altered – indeed things have got worse. In 2024, the top ten percent of households in South Korea owned about 44.4 percent of total household net worth, while households in the lowest wealth decile owned minus 0.1 percent. South Korea’s poverty rate and its income inequality are among the worst among wealthy countries, with youths facing some of the steepest challenges. Nearly one in every five South Koreans between the ages of 15 and 29 are effectively jobless.

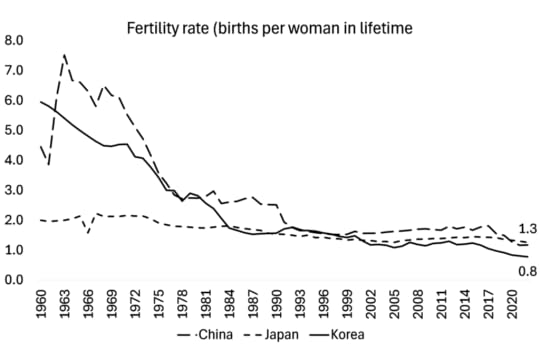

The real issue in the future is the decline in the population. With the world’s lowest fertility rate, the Korean workforce could halve over the next 40 years. Korea has become a “super-aged” society, which the UN defines as an economy with more than 20% of the population 65 years old or over. If the size of South Korea’s working population continues to decline, the economy could begin contracting by 2040.

Source: World Bank

The Korean economy is now close to an outright recession. The Korean economy is projected to grow by just 0.8% in 2025, weighed down by a contraction in construction and deteriorating trade conditions.

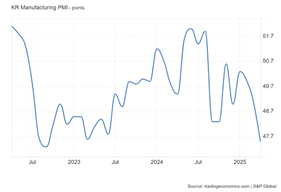

The Composite Consumer Sentiment Index, a critical gauge of consumer confidence, plummeted to 88.4 in December, reflecting a steep decline of 12.3 points—the sharpest drop since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. The manufacturing sector is a serious slump (the manufacturing activity index is well below the 50 benchmark for expansion).

What’s Lee’s answer to this economic stagnation? He says he wants to expand government spending and investment. But this ‘fiscal approach’ has been widely attacked by the right-wing and the financial sector. The interim government wants to cut ‘discretionary spending’ by more than 10% and is even considering ‘adjustments’ in mandatory government expenditures, such as the basic pension and grant-in-aid for educational finance. The current government said: “In the past, we focused on short-term ‘sound fiscal policy,’ but now we mean to consider medium and long-term ‘fiscal sustainability.”

Lee will probably not reverse these moves to fiscal austerity in civil expenditures because of the growing demand for more spending on ‘defence’ . Lee talks of better relations with China, but Trump is demanding more Korean contribution to ‘defence’ against China. And there are growing calls among the elite to have nuclear weapons, given the supposed threat of North Korea and uncertainty about Trump’s commitment to South Korea’s defence. According to recent polls, 66 percent of South Koreans support their country going nuclear. Prominent Korean political leaders in both the conservative and progressive camps have not ruled out such policies, with some openly supporting them. From welfare to warfare.

May 24, 2025

Donald Trump’s ‘big, beautiful’ tax bill

The US House of Representatives, the lower house of Congress, in which the Republican party has a slender majority, has passed President Donald Trump’s government budget proposals. Trump calls this “The Big, Beautiful Bill”. It would extend sweeping tax cuts for the better-off and rich that were passed in 2017 during Trump’s first presidential term. The beautiful bill would also make big reductions to the Medicaid insurance scheme for low-income individuals and to a food aid programme. And of course, there are cuts in tax subsidies for renewable energy (‘drill baby, drill’).

Trump had called for $163bn in cuts to federal spending. Non-defence spending is to be slashed by 22.6% to its lowest level since 2017, alongside a sharp increase in the defence budget. While non-defence government services are to be drastically cut, government outlays will rise 13% for ‘defence’ and 65% for ‘homeland security’, with the aim to clamp down on so-called ‘illegal immigration’.

The planned cuts in Medicaid are particularly brutal. America is the only advanced economy without a system of universal health coverage. The US spends more than $4.5tn annually on healthcare. Healthcare is the largest component of US consumer spending on services (well above expenditure on recreation, eating out and hotels). Safety net programs like Medicaid lift 45% of Americans who would be below the poverty line out of poverty. Substantial cuts to Medicaid would result in millions without health insurance. And these programs don’t only serve those below the poverty line, but millions more paycheck-to-paycheck, near-poor families.

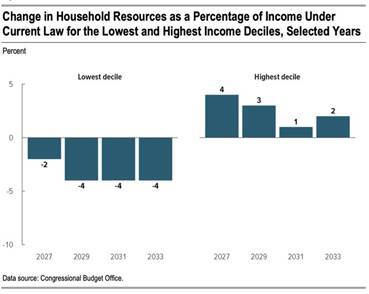

The tax cuts will primarily benefit high-income households and corporations, while the spending cuts will disproportionately affect low- and middle-income households. These include reductions to Medicaid, nutritional assistance programs, the layoff of hundreds of thousands of federal employees, and the dismantling of entire government agencies.

According to recent estimates by the Yale Budget Lab, the average after-tax-and-transfer income of households in the bottom quintile and second-to-bottom quintile is expected to decrease by 5% and 1.4%, respectively. On the other hand, households in the fourth and top quintile will see their incomes increase by 1.4% and 2.5% respectively. These losses are on top of the estimated reduction in median household income by 2.8% due to Trump’s tariffs. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reckons these estimated losses of the bottom quintiles are likely conservative, as they do not account for cuts overseen by the House Education and Workforce Committee, which are expected to affect student loan repayment conditions.

What this tells you is that all the talk of Trump changing America’s previous neo-liberal pro-free market policies towards some ‘industrial strategy’ based on protectionism applies only to international trade. Trump’s domestic policies are neo-liberal on steroids – more for the rich and less for the rest; more spending for the arms industry and less on public services for the rest of us; and more for big business and less for labour and small businesses. Trump’s budget will only increase the already grotesque rise in inequality of wealth and income in the US seen in the last 40 years.

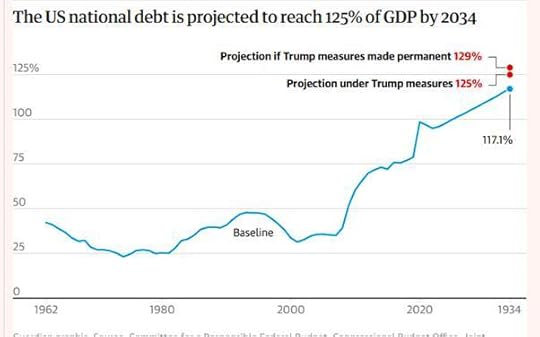

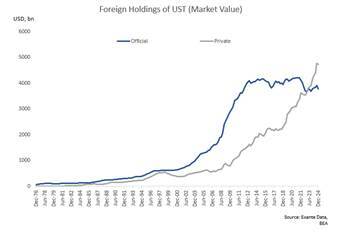

But this is not what worries America’s ruling elite. What is not beautiful but ugly to them is not rising inequality, but the sharp rise in the government budget deficit and overall public sector debt that will follow the implementation of this budget. The non-partisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates Trump’s budget would increase the public debt by at least $3.3tn through to the end of 2034. It would also increase the government debt-to-GDP ratio from 100% today to a record 125%. That would exceed the rise to 117% projected over that period under current law. Meanwhile, annual deficits would rise to 6.9% of GDP from about 6.4% in 2024.

Does this matter? After all, the US authorities can borrow more dollars from the banks and financial institutions by issuing government bonds. But the government must pay interest on those extra bonds for a decade or more ahead. And can the US government under Trump be trusted to control spending and meet its obligations? Moody’s, the largest US credit agency that monitors the likelihood of default on debts by companies, is not so sure as it was. It announced a downgrade in the credit-worthiness of US government debt. As a result, almost immediately, the interest demanded by financial institutions on buying US government debt rose. The 30-year Treasury yield rose to a peak of 5.04%, its highest level since 2023. That will add to the cost of interest on the government’s debt. According to Moody’s, interest payments in the US are on a path to consume 30% of the federal government’s revenue by 2035, compared with 9% in 2021. But most important, this will also feed through to the interest charged on all borrowing by companies and household mortgages. If businesses can’t get access to credit, that can halt investment and lead to job losses over time. First-time buyers and those wishing to move home could also face higher costs.

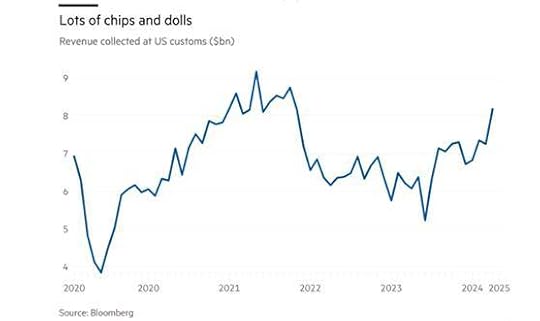

Trump’s MAGA advisers say the budget will pay for itself with higher growth from tax cuts and deregulation. This is the classic ‘trickle down’ theory that tax cuts for the rich will boost economic growth, continually claimed by free market economists and refuted time and again as effective. The MAGA boys and girls argue that revenues from the tariff increases proposed on foreign imports will compensate for the loss of revenue from the proposed tax cuts. This, of course, is nonsense. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reckons that Trump’s tariff increases will collect $245bn more in tax revenues than in fiscal year 2024. But that is a tiny sum against the $5.2tn in total tax receipts that the CBO expects this year and the $1.8trn budget deficit.

The Maga advisers in the Trump administration want the Federal Reserve to deregulate the financial sector to remove restrictions on the leverage ratio (ie asset buying limits) on banks so that they can buy more US treasuries. It seems that the lesson of the March 2023 banking crisis is to be ignored. That’s when some regional banks went bust because they held too many US government bonds that suddenly dropped in value.

Some have even suggested that Trump’s fiscal largesse will actually lead to a financial crisis – just as it did for Liz Truss in the UK. Truss was (very briefly, just 47 days) UK prime minister in the Conservative government in 2022. She introduced a ‘budget for growth’ which slashed taxes for the rich in true ‘trickle-down’ mode. The projected rise in the UK budget deficit and public debt so frightened holders of UK bonds, particularly pension funds that held a huge share, that the value of UK ‘gilts’ plummeted and the Bank of England was forced to intervene and buy bonds to stop interest rates spiralling out of control. Also, the UK pound slumped to its lowest level ever in FX markets. Within weeks, Truss was removed as leader by her party, under pressure from the financial institutions that bankrolled the Conservatives, and former hedge fund manager and Goldman Sachs executive Rishi Sunak took over. The markets ruled.

Liz Truss with her MAGA cap for the Trump inauguration

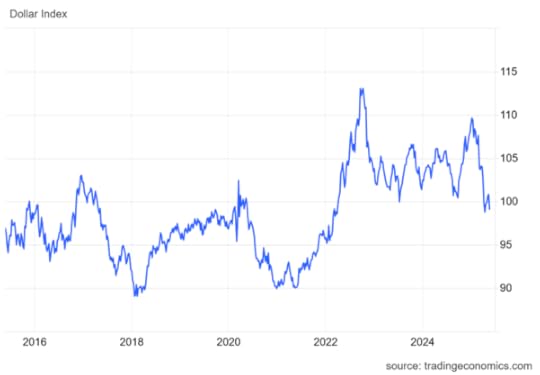

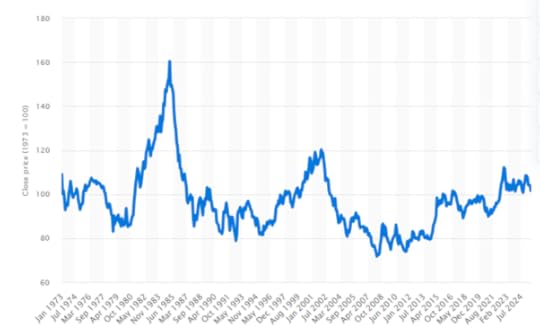

Still, a ‘Liz Truss moment’ is not going to happen in the US. The UK runs twin trade and budget deficits like the US, but it depends much more on what current Canadian PM and former Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, called ‘the kindness of strangers’. In other words, the deficits must be financed by foreign investment, either investment in UK industry or in its bonds and currency. That ‘kindness’ disappeared overnight under Truss. But that won’t happen under Trump because the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency and main trading and investment currency and will remain so. It’s true that the dollar has slipped in recent months under Trump following his tariff war and after his budget plans. But it is still at relative highs historically.

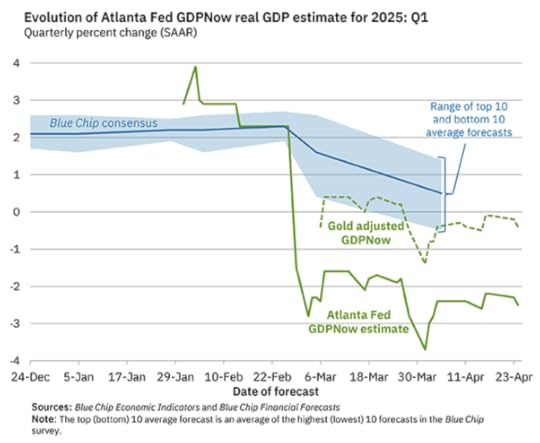

The real issue is not the trade and government deficits or the swings and turns of Trump’s tariff war – the latest being the decision to impose a 50% tariff on all imports from Europe next week unless there is a trade deal. Financial markets and investment bank economists yo yo up and down with each Trump tantrum, because they are not sure if the ‘Taco’ factor is operating – namely the notion that Trump Always Chickens Out on his threats in the end. No, the real issue is whether the US economy is heading towards a recession ie an outright decline in national output and investment and a significant rise in unemployment; or alternatively ‘stagflation’ where the economy stands still in output and income terms, but inflation and interest rates stay high.

In the first quarter of 2025, US GDP fell 0.3% on the first estimate – that may be revised upwards in the next estimate. And if you strip out exports and imports and government spending, the domestic private sector is still growing modestly. But the US economy is standing on a precipice, with Trump’s tariffs, which remain in place at some 15% higher on average than before, ready to knock it over the cliff.

One highly used indicator of recession is the so-called Sahm measure. The statistic, named after former Federal Reserve economist Claudia Sahm, compares the most recent three-month average unemployment rate with the minimum three-month average over the previous year. If the difference is greater than 0.5% pt, then a recession has started. The Sahm measure currently sits at close to 0.3% pt and would require monthly unemployment rate increases of 0.1 percentage points until September 2025 to reach the threshold. So on this indicator, the US economy is not in a recession and even another quarter of negative growth is unlikely to generate one.

But for me, unemployment is a lagging indicator for the economy. A Marxist theory of crises starts with profits, goes on to investment, and then to income and employment. So the key leading indicator will be profits. For now, corporate profits are still rising, if at a slowing pace. But if profits start falling, it won’t be too long after before investment in the productive sectors of the economy (industry, information, transport, fossil fuel production etc) start to fall. That will signal the beginning of an outright slump.

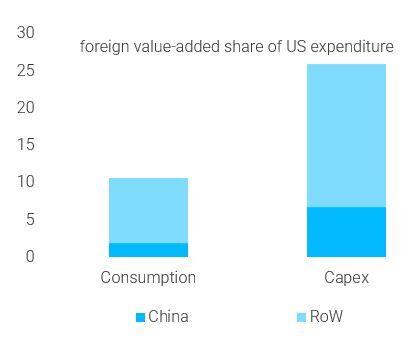

US corporations are now facing slowing demand for their goods and services, particularly for exports, and tariffs will drive up production costs that firms will have to absorb by reducing profits or laying off workers or that they will pass onto households in higher prices – or both. Add in rising and relatively high interest rates on new borrowing and on servicing existing debt and the profits squeeze will intensify. Citibank reckons that average corporate earnings growth will drop to just 1% this year. And a recent Fed study found that a “sudden stop” on Chinese imports would affect 7% of US corporate investment.

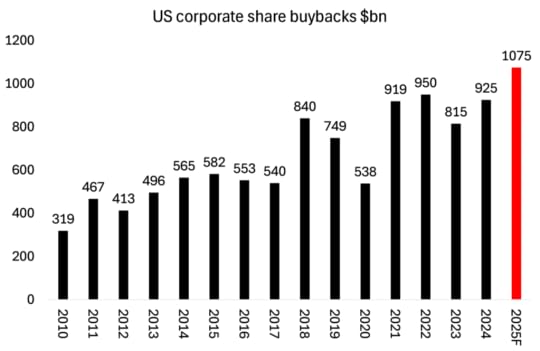

Moreover, companies that have made profits in the last year are not re-investing into new capacity, but instead buying back their own shares to boost their share prices (to the tune of $500bn over the past three months).

American households are also not as confident about the economy as the Maga advisers or the investment bank economists. Consumer confidence has dropped to the second-lowest level on record.

And that’s not surprising when the gap between what Americans earn and how much they need to bring in to achieve a decent standard of living is growing. According to the Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity (LISEP), for the bottom 60% of US households by incomes, a “minimal quality of life” is out of reach. The US official unemployment rate of 4.2% greatly understates the level of economic distress. LISEP factor-in workers who are stuck in poverty-wage jobs and people who are unable to find full-time employment, and that takes the US jobless rate to over 24%. American households, which in 2023 earned an average of $38,000 per year, would need to make $67,000 to afford things and services a household needs to have a decent life. Housing and health care costs have surged, while the amount of savings required to attend an in-state, public university has soared 122%. Meanwhile, median earnings for the bottom 60% of income earners have fallen 4% between 2001 and 2023.

And now they are to receive Trump’s ‘big, beautiful’ tax bill.

May 18, 2025

Progressive Economics and progressive capitalism

Last week I attended a one day conference organised by the Progressive Economy Forum (PEF). PEF is a British leftist economic think tank that advised the Corbyn-McDonnell Labour leadership when they were in charge of the British Labour Party. PEF’s aim is to “bring together a Council of eminent economists and academics to develop a new macroeconomic programme for the UK.” The PEF council wants to “advance macroeconomic policies that address the modern challenges of environmental breakdown, economic insecurity, social and economic inequalities, and technological change and encourage the implementation of these policies by working with progressive policymakers and improving public understanding of economics.” The only specific policy proposal that I could find in its mission statement was that the PEF “opposes austerity and the current ideology and narrative of neoliberalism, campaigns to bring austerity to an end and ensure that austerity is never used again as an instrument of economic policy.”

Former lawyer Patrick Allen is the founder, chair and principal funder of the PEF. He sees its task as to “bring together the finest progressive economists and like-minded academics in the country to join with progressive politicians to show the failure of neoliberalism, the futility of austerity and provide credible, Keynesian-inspired policies to achieve a stable, equitable , green, sustainable economy free of poverty.”

The specific mention of Keynesian economics does identify where the PEF is coming from. It is ‘progressive’ economics, not socialist economics, and definitely not Marxist economics. That was clear from the many eminent speakers at the PEF conference entitled ‘Economic Policy in the Age of Trump’. All the speakers were well-known Keynesian or post-Keynesian economists. The only whiff of Marxism came from a pre-recorded video opening the conference by Yanis Varoufakis from his home in Greece. Former Greek finance minister for the leftist Syriza government during the debt crisis of 2014-15, Varoufakis is a self-confessed ‘erratic Marxist’ as he called himself once.

In his short address, he outlined his well-known thesis that the fault-lines in capitalism are due to global imbalances in trade and capital flows and the crumbling of American imperialism in trying sustain its hegemonic position as the ‘global minotaur’, the consumer of all that is produced. He also briefly mentioned his latest thesis that capitalism as we have known it, is now ‘dead’ and has been replaced by ‘techno-feudalism’ in the shape of the mega media and tech companies in the US, known as the Magnificent Seven, who extract ‘cloud rents’ from the rest of capitalism. Varoufakis’ policy alternatives to this perceived new feudalism was to push for: a ‘green’ bank to provide credit for investment to stop global warming etc; introduce more democracy in the corporate workplace; and provide universal basic income for all. Taking over the Magnificent Seven, or the major global banks, of the fossil fuel companies was not mentioned.

But that fitted in with the theme of the PEF conference. This started from the premise that capitalism had to ‘re-purposed’, not replaced and that ‘rentierism’ should be constrained and social protection revised. A succession of speakers followed, talking about the failures and inequalities of ‘rentier’ capitalism (PEF); or ‘extractive’ capitalism (Stewart Lansley) or ‘dystopian’ capitalism (Ozlem Onaran), as though these variations had replaced some original ‘productive’ capitalism, as we knew back in the years of the 1950s and 1960s, which worked for all then – or at least did so if managed by governments using Keynesian macro policies. All was well under the global management of the ‘Bretton Wood institutions’ of the post-war period (the IMF, World Bank, WTO etc). It was only when neoliberalism and rentierism took over from the 1980s onwards that capitalism became destructive and no longer ‘progressive’; with crises, rising inequalities, global warming and emerging global conflicts.

There was no explanation of why this ‘progressive’ capitalism of the 1960s came to be replaced by neoliberal, extractive, rentier capitalism now. Why did capitalists and their policy strategists change things that were working so well for them? No mention of the global decline in the profitability of productive capital in the 1970s and thus the switch to financial investment and speculation; and the move of investment from the Global North by the multinationals to exploitation of labour in the Global South. Stewart Lansley presented some startling facts about inequality of wealth since the 1980s with the rise of the billionaires and finance. “In the post-war years financial and economic elites acquiesced, with reluctance, in the politics of equalisation and pre-war levels of extraction fell. With capital’s patience exhausted, extraction is back.” So it was a ‘lack of patience’ that led to the switch, not a lack of profitability.

Several speakers highlighted the way that American capital had now taken over large chunks of the British economy, turning it into what Angus Hanton called a ‘vassal state’ and what Will Hutton, the economist and author, reckoned has destroyed the technical development of British industry. Europe and the UK was falling further and further behind American productivity levels. But what was the answer to this American takeover? It was nationalism, not nationalisation, apparently. Hanton: “buy British”; Hutton develop a “British business bank” – but don’t take into public ownership the utilities, the banks and big companies now owned and controlled by foreign capital (mainly American).

In another session, speakers outlined the huge imbalances in trade and capital flows globally, the signs of the weakening of US hegemony and the dollar as the international currency, and the rise of China as the rival economic power. What was the answer to this; well, the hope that maybe the BRICS+ grouping can reduce imbalances and restore multilateralism in the face of Trump’s tariff-driven nationalism.

In this session, Ann Pettifor argued that crises in capitalism were the result of excessive debt (trends in profits or investment were not mentioned) and that we should look to the work of American leftist economist and Nobel prize winner, Joseph Stiglitz, and his recent book, ‘The road to freedom’, where Stiglitz reiterated his call for the creation of a “progressive capitalism”. “Things don’t have to be that way. There is an alternative: progressive capitalism. Progressive capitalism is not an oxymoron; we can indeed channel the power of the market to serve society.” (Stiglitz). You see, it is not capitalism that is the problem but ‘vested interests’, especially among monopolists and bankers. The answer is to return to the days of ‘managed capitalism’ that Stiglitz believes existed in the golden age of the 1950s and 1960s. Stiglitz: “the form of capitalism that we’ve seen over the last 40 years has not been working for most people. We have to have progressive capitalism. We have to tame capitalism and redirect capitalism so it serves our society. You know, people are not supposed to serve the economy; the economy is supposed to serve our people”.

In another session, the shocking inequalities of income and wealth were discussed. Interestingly, some speakers like Ben Tippett argued that introducing a wealth tax in Britain would do little to reduce inequality or provide much in the way of government revenue. A wealth tax was no ‘silver bullet’. Tippett was right. A wealth tax would not solve inequality or provide enough funds for public investment. But nobody asked the question: why do we have billionaires and high inequality in the first place? Inequality is the result of the exploitation of labour by capital before redistribution. Taxation attempts redistribution of wealth or income after the event, with limited success.

In similar vein, we were told by Josh Ryan-Collins that building more homes would not solve the housing crisis in Britain because that was driven by low mortgage rates (cheap loans) that just drove up demand. His answer: encourage older people with big houses to ‘downsize’ and free up the existing housing stock for younger buyers. Apparently, a state-funded programme to build publicly owned homes for rent, as was done in the 1950s and 1960s with great success, was not the way forward now.

Jo Michell attacked the ludicrous self-imposed fiscal rules that the Labour government is applying in order to ‘balance the government books’. But he opposed them only because they were too ‘short-term’ in their casting. The implication was that there were no radical alternatives to raise revenue that could avoid the Starmer government going ahead with imposing fiscal austerity through planned cuts in benefits to the aged, disabled and families.

The Bank of England was criticised for its mismanagement of quantitative easing and now tightening, which was running up costs equivalent to £20bn on the government finances (Frances Coppola). But it seemed nobody was in favour of ending the BoE’s subservience to the City of London by reversing its so-called ‘independence’. You see, the BoE’s job was to ‘preserve price stability’ (France Coppola) – a strange view given the total failure of central banks to handle the post-COVID inflationary spike. Apparently, keeping central banks out of democratic control by elected governments ensured that no ‘profligate’ government (even if democratically elected) could play with interest rates etc and so cause a financial crisis with markets. After all, markets rule and nothing can be done about that, apparently. Taking the major banks and financial institutions into public ownership was not on the agenda of any speaker.

In the final sessions, a broader alternative to ‘rentier’, ‘extractive’, or ‘dystopian’ capitalism was considered. PEF council member Guy Standing, author of the Precariat, raised the growing risk of fascism and its threat to the ‘progressive agenda’. In his theory, the traditional working class is being replaced globally and in Britain by a ‘precarious’ class who have no permanent work or decent wages and conditions and are being ‘left behind’. This growing class is open to reactionary ideas that the ‘plutocracy’ aims to encourage and promote; and there is a real danger of class collaboration between the extreme rich and the precariat against the ‘salariat’ (a term I took to mean, the traditional working class). What’s the answer?: embrace the precariat, says Standing , instead of the working class; and dismantle ‘extractive capitalism’, replacing it with the ‘commons’. Standing did not really explain what the commons meant, apart from its historic term of ‘common land’. Did he mean socialism? I am not sure because throughout the conference, the word ‘socialism’ (I think the real meaning of the ‘commons’) was not uttered once.

John McDonnell and Nadia Whittome are two of Britain’s best leftist Labour politicians. McDonnell told the conference that he has never been so depressed about the situation in Britain and globally in his 50 years in politics. What to do? We must try to get the Starmer government ‘back on track’ to adopt policies to help working people. A vain hope, in my view. Whittome also outlined the horrendous impact of capitalism at home and abroad. But what was the answer? Surely not better management of capitalism? It was perhaps provided by the very slogan from William Beveridge in 1942 used by the PEF on its conference literature: “A revolutionary moment in the world’s history is a time for revolutions, not for patching”. Indeed! But for now, the PEF advocates patching.

May 13, 2025

Geonomics, nationalism and trade

Geonomics is a new term for international economic theories and policies. According to Gillian Tett at the FT, in the past, “it was generally assumed that rational economic self interest ruled the roost, not grubby politics. Politics seemed to be derivative of economics — not the other way around. No longer. The trade war unleashed by US President Donald Trump has shocked many investors, since it seems so irrational by the standards of neoliberal economics. But “rational” or not, it reflects a shift to a world where economics has taken second place to political games, not just in America, but many other places too.”

Lenin once said that “Politics is the most concentrated expression of economics.” He was arguing that policies of states and war (politics by other means) were driven in the last analysis by economic interests ie the class interests of capital and the rivalries between ‘many capitals’. But apparently, Lenin’s view has now been turned upside down by Donald Trump. Now economics is to be ruled by political games; the class interests of capital have been replaced by the separate political interests of cliques. So apparently, we need economic theories that can model this ie geonomics.

Now apparently, geonomics has surfaced to make this hegemonic power politics respectable and ‘realistic’. Liberal democracy and ‘internationalism’ along with liberal economics ie free trade and free markets, is no longer relevant for economists, trained before to promote an economic world of equilibrium, equality, competition and ‘comparative advantage’ for all. That’s out of the window: now economics is about power struggles conducted by states furthering their own national interests.

A recent paper argued that economists must now consider that power politics will rule over economic advantage; in particular, a hegemonic power like the US will try to improve its economic advantage not by better productivity growth or investment at home, but by intimidation and force over other countries: “Hegemonic countries, however, often seek to influence foreign entities over which they have no direct control. They do so either by threatening negative consequences if the target does not undertake the desired actions, thus lowering the outside option of the participation constraint; or by promising positive benefits if the target does undertake the desired actions.”

According to these World Bank authors, this ‘power economics’ can actually be beneficial to both the hegemonic power and to the target of its threats: “hegemony can be modelled in a macroeconomist-friendly way.” Really? Tell that to China which faces the strangulation of its economy by sanctions, bans, huge tariffs on its exports and the blocking of its investments and companies globally – all initiated by the current hegemonic power, the US, fearful of losing its status, and determined to weaken and cripple any opposition through politics by any means (including war). Tell that to the poor countries of the world facing significant tariffs on their exports to the US.

Of course, international cooperation among equals to increase trade and markets was always an illusion. There never has been trade among equals; there never has been ‘fair’ competition among capitals of broadly equal size within economies or between national economies in the international arena. The large and strong have always eaten the weak and the small, especially in economic crises. And the imperialist core in the Global North has extracted value and resources in the trillions out of the peripheral economies over two centuries.

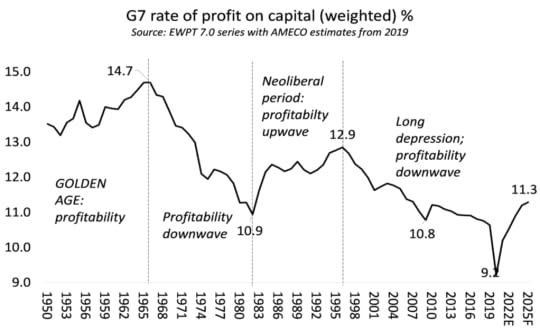

Nevertheless, it is true that there is a change in view among part of the elite on economic policy, particularly since the Global Financial Crash of 2008 and ensuing Long Depression in economic growth, investment and productivity. In the immediate post-WW2 period, international trade and financial agencies were formed under the control primarily of the US. Profitability of capital in the major economies was high and this allowed international trade to expand along with the revival of European and Japanese industrial power. This was also the period when Keynesian economics dominated ie. the state acted to ‘manage’ the economic cycle and support industry with incentives and even some industrial strategy.

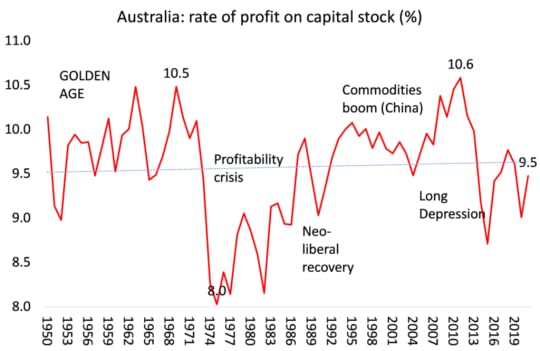

This ‘golden era’ came to an end in the 1970s, when the profitability of capital fell sharply (according to Marx’s law) and the major economies suffered the first simultaneous slump in 1974-75, followed in 1980-2 with a deep manufacturing slump. Keynesian economics was exposed as a failure and economics returned to the neoclassical idea of free markets, free flow of trade and capital, deregulation of state interference and ownership of industry and finance, and the crushing of labour organisations. Profitability was (modestly) restored in the major economies and globalisation became the mantra; in effect the expansion of imperialist exploitation of the periphery under the guise of international trade and capital flows.

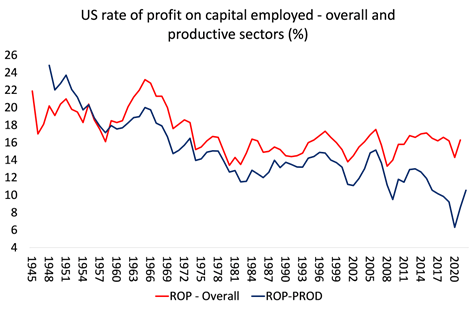

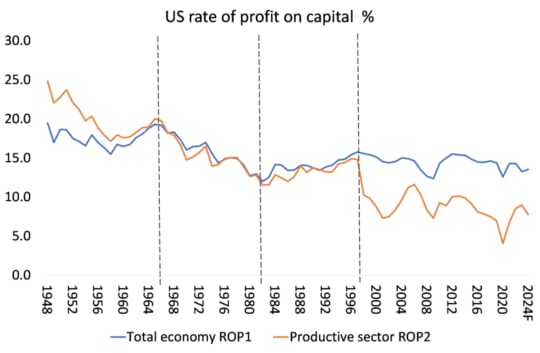

But again, Marx’s law of profitability exerted its gravitational pull and from the turn of the millennium, the major economies experienced a fall in the profitability of their productive sectors. Only a credit-fuelled boom in finance, real estate and other unproductive sectors disguised that underlying crisis of profitability for a while (the blue line below shows the profitability of US productive sectors and the red line, the overall profitability).

Source: BEA NIPA tables, author calculation

But eventually this culminated in the global financial collapse, the Euro debt crisis and the Long Depression; further enhanced by the impact of the pandemic slump of 2020. European capital has been left in tatters. And US hegemony now faced a new economic rival, China, after its stupendous rise in manufacturing, trade, and more recently technology, unaffected by economic crises in the West.

So in the 2020s, as Gillian Tett put it: “the intellectual pendulum is now swinging again, towards more nationalist protectionism (with a dose of military Keynesianism), thus fits a historical pattern. In America, Trumpism is an extreme and unstable form of nationalism, now apparently to be studied seriously by the new school of ‘geonomics’. Government intervention/support Keynesian style to protect and revive America’s weakened productive sectors was launched by Biden with an ‘industrial strategy’ of government incentives and funding for the US technology giants, coupled with tariffs and sanctions on rivals, ie China. Trump has now doubled down on that ‘strategy’. “

Protectionism internationally is being combined with government intervention domestically in decimating government services, ending climate change mitigation spending, deregulating finance and the environment and boosting the military and homeland security forces (particularly to increase deportations and intimidation).

This hegemonic crude power politics is now being made logical and even advantageous to all Americans by right-wing economists. In a new book called Industrial Policy for the United States, Marc Fasteau and Ian Fletcher, two economists beloved by the Maga crowd. They are part of the so-called Council for a Prosperous America, which is funded by a bunch of smallish companies mainly engaged in domestic production and trade. “We are an unrivaled coalition of manufacturers, workers, farmers, and ranchers working together to rebuild America for ourselves, our children, and our grandchildren. We value quality employment, national security, and domestic self-sufficiency over cheap consumption.” It’s a body based on class unity between capital and labour to ‘make America great again’.

Fasteau and Fletcher argue that America has lost its hegemonic position in global manufacturing and technology because of neo-classical free market liberal economics: “laissez-faire ideas have failed and that a robust industrial policy is the best way for America to remain prosperous and secure. Trump and Biden have enacted some elem ents, yet America now needs something systematic and comprehensive, including tariffs, a competitive exchange rate, and federal support for commercialization—not just invention—of new technologies.”

F&F’s ‘industrial policy’ has three ‘pillars’: re-build key domestic industries; protect these industries from foreign competition through import tariffs and sanctions on foreign economies where government place obstacles in the way of US exports; and ‘manage’ the dollar exchange to the point that the US trade deficit disappears ie devaluation of the dollar.

F&F reject the Ricardian trade theory of comparative advantage, a theory that is still the basis for mainstream economics to argue that ‘free’ international trade will benefit all countries, ceteris paribus. They consider that ‘free trade’ can actually reduce output and incomes for a country like the US because of cheap imports from low-wage countries destroying domestic producers and weakening the ability of home producers to gain export market share globally. Instead, they argue that protectionist policies of import tariffs can boost productivity and incomes in the home economy. “America’s free trade policy, forged in a long-vanished era of global economic dominance, has failed in both theory and practice. Innovative economic modeling has shown how well-designed tariffs, to give only one example of industrial policy, could give us better jobs, higher incomes, and GDP growth.” Yes, according to the authors, tariffs will deliver higher incomes for all.

F&F express the interests of American capital based at home, no longer able to compete in many world markets. As Engels argued back in the 19th century, free trade is supported by the hegemonic economic power as long as it dominates international markets with its products; but when it loses dominance, it will adopt protectionist policies. (see my book, Engels pp 125-127). This is what happened in the late 19th century to UK policy. Now it is the turn of the US.

Ricardo (and the neoclassical economists of today) are wrong in claiming that all countries gain from international trade if they specialise in exporting products where they have ‘comparative advantage’. Free trade and specialization based on comparative advantage does not produce a tendency towards mutual benefit. It creates further disequilibrium and conflict. This is because the nature of the capitalist production processes creates a tendency toward increasing centralization and concentration of production, which leads to uneven development and crises.

On the other hand, the protectionists are wrong to claim that import tariffs and other measures will restore a country’s previous market share. But F&F do not rely on tariffs alone for their industrial strategy. They define industrial policy as “deliberate governmental support of industries, with such support falling into two categories. First are broad policies that assist all industries, such as exchange rate management and tax breaks for R&D. Second are policies that target particular industries or technologies, such as tariffs, subsidies, government procurement, export controls, and technological research done or funded by government.”

F&F’s industrial strategy will not work. In economies, productivity growth and lower costs depend on increased investment in productivity-enhancing sectors. But in capitalist economies that depends on the willingness of profit-driven companies to invest more. If profitability is low and/or falling, they will not do so. That’s the experience of the last two decades, in particular. F&F want a return to war-time policies and cold war strategy to build domestic industry, science and military forces. But that would only work if there was a massive switch to direct public investment through publicly owned companies with a national industrial plan. F&F don’t want that and neither does Trump.

F&F say that their economic policy is neither left nor right. And in one sense, that’s true. Industrial strategy is proclaimed by left Keynesians in Britain, by Elizabeth Warren and Sanders in America and even by Mario Draghi in Europe. And ‘industrial strategy’ was adopted as economic policy in most East Asian economies in the latter half of the 20th century (although increasingly no longer).

But of course, F&F’s apparently ‘neutral’ industrial strategy is no such thing when it comes to China because as they say, China is “the first combined military and economic threat America has faced in more than 200 years.” They put it bluntly: “An increasing number of Chinese industries are in acute rivalry with high-value American industries, and China’s gains are our losses. The US cannot remain a military superpower without being an industrial superpower.” This sums up the motivation for the switch from neoclassical laisser faire, free trade economics that has dominated the academic ivory towers of economic departments and international economic agencies up to now. America’s (and Europe’s) economic domination has been weakened to the point that there is a significant risk that China will rule globally within a generation. So the gloves are off.

Away with the concept of free competition, markets and trade – which never really existed anyway. Bring in the realism of winning the battle for political and economic power by all means necessary. This is the nature of the new geonomics, presumably soon to be in the economic departments of universities in the Global North, despite the rearguard opposition of the currently dominant neo-classical, neo-liberal professors.

May 6, 2025

150 years since the Critique of the Gotha Programme

The Critique was a document based on a letter by Marx written in early May 1875 to the Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Germany (SDAP), with whom Marx and Friedrich Engels were in close association. The letter is named after the Gotha Programme, a proposed manifesto for a forthcoming party congress that was to take place in the town of Gotha. At that congress, the SDAP planned to merge with the General German Workers’ Association (ADAV), who were followers of Ferdinand Lassalle, to form a unified party.

Karl Marx’s ‘Critique of the Gotha Programme’ was written 150 years ago this week. It provides us with Marx’s most detailed pronouncements on revolutionary strategy, the meaning of the term ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat’, the nature of the period of transition from capitalism to communism, and the importance of internationalism.

Gotha Conference: May 1875

A socialist activist and politician, Lassalle viewed the state as the expression of ‘the people’, not as a construct of any social class. He adopted a form of state socialism and rejected class struggle by the workers through trade unions. Instead he had a Malthusian theory of the”iron law of wages“, which argued that if wages rose above the subsistence level in an economy, the population would grow and more workers would compete, forcing wages down again. Marx and Engels had long rejected this theory of wages (see my book, Engels 200 pp40-42).

Ferdinand Lassalle

The Eisenachers sent the draft programme for a united party to Marx for comment. He found the programme significantly influenced by Lassalle and so responded with his Critique. However, at the congress held in Gotha in late May 1875 to set up the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the programme was accepted with only minor alterations, Marx’s critical letter was published by Engels only much later in 1891, when the SPD declared its intention of adopting a new programme, the result being the Erfurt Programme of 1891. Drafted by Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein, this program superseded the Gotha Program and was closer to Marx and Engels’ views.

In the Critique, among other things, Marx attacked the Lassallean proposal for “state aid” rather than public ownership and the abolition of commodity production. Marx also noted that there was no mention of the organisation of the working class as a class: “and that is a point of the utmost importance, this being the proletariat’s true class organisation in which it fights its daily battles with capital”.

Marx objected to the program’s reference to a ‘free people’s state’. For Marx, “the state is merely a transitional institution of which use is made in the struggle, in the revolution, to keep down one’s enemies by force” so “it is utter nonsense to speak of a free people’s state; …as soon as there can be any question of freedom, the state as such ceases to exist.” This was (and is) a vital distinction between the views of Marx and Engels on the state in a post-capitalist society and the views of social democracy and Stalinism, which talks of ‘state socialism’.

Two stages of communism

Both Marx and Engels always referred to themselves as communists to make the distinction with earlier forms of socialism. They defined communism simply as the ‘dissolution of the mode of production and form of society based on exchange value.’ The most basic feature of communism in Marx’s critique is the overcoming of capitalism’s separation of the producers (labour) from the control of production. To reverse this entails a complete decommodification of labour power. Communist or ‘associated’ production would be planned and carried out by the producers and communities themselves, without the class-based intermediaries of wage labour, market and state.