Michael Roberts's Blog, page 6

March 8, 2025

‘Two sessions’ China

The Chinese government is just completing its annual ‘two sessions’ or lianghui, where China’s political elite approve the economic policy agenda for the coming year. The ‘two sessions’ refers to two major political gatherings: the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a political advisory committee; and the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s top legislative body.

These are ostensibly not meetings of the Communist party but instead are meetings of the Chinese state. The consultative meeting is largely symbolic with leading business and local leaders appearing for pre-arranged discussions. The real focus is the NPC which officially decides economic policy. In reality, it merely approves what the leading CP elite have already decided in advance. With around two-thirds of its members belonging to the Communist Party, the NPC has never rejected a bill proposed by the party.

Premier Li Qiang presented the government work report, outlining key economic targets and strategies for the year ahead. This year’s NPC was also monitoring the final year of decade-long economc plan “Made in China 2025”, which aimed at making China self-reliant in key industrial sectors. 2025 is also the last year of the current (14th) five-year plan that state bodies and private industry are supposed to follow to meet economic objectives. The next plan (2026-30) will be outlined at next year’s NPC.

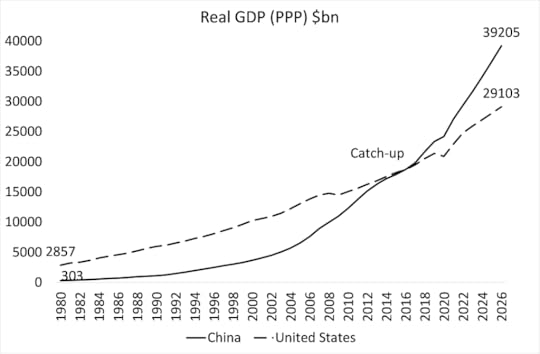

How has China been doing in meeting the targets set in Made in China and the 14th five-year plan? Well, according to the South China Morning Post, often a strong critic of China’s success, 86% of the 250 targets set have been met or exceeded. Measured in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, China’s aggregate real GDP surpassed that of the US back in 2018.

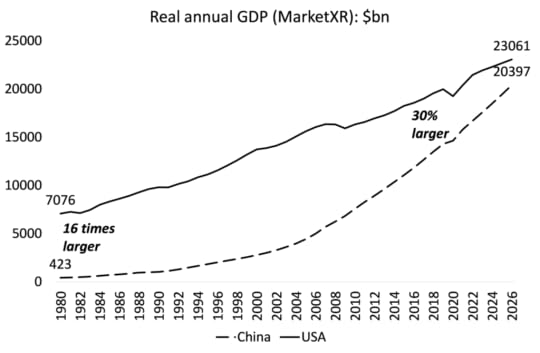

However, the PPP measure of GDP estimates the value of goods and services that can be purchased with dollars within China. If we measure real GDP in international market dollars, then China’s GDP is still behind that of the US – but the gap is closing.

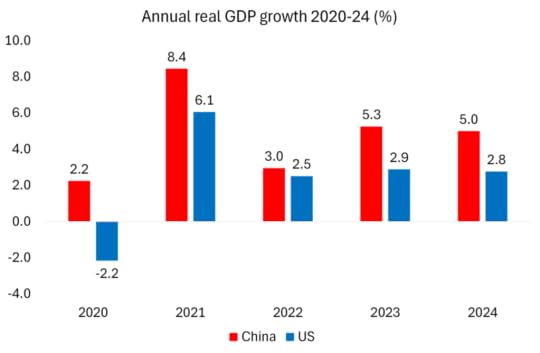

The gap with the US on GDP is closing because, although China’s annual real GDP growth is no longer in double-digits, it is still growing nearly twice as fast as the US economy.

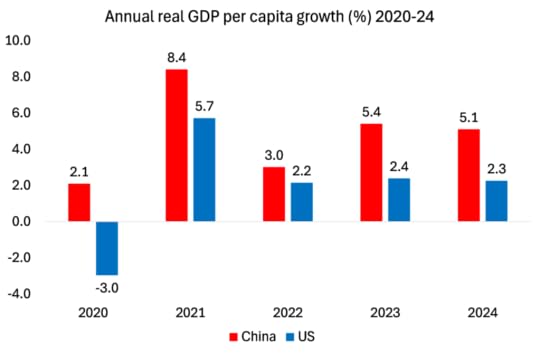

China was the only major economy that avoided a recession during the pandemic slump of 2020 and managed to grow by 5% last year compared to the US, the fastest growing G7 economy, at 2.8%. Moreover, US real GDP grew by as much as 2.8% last year partly because net immigration raised the size of the workforce – more people, more output. US real GDP growth per person was much less.

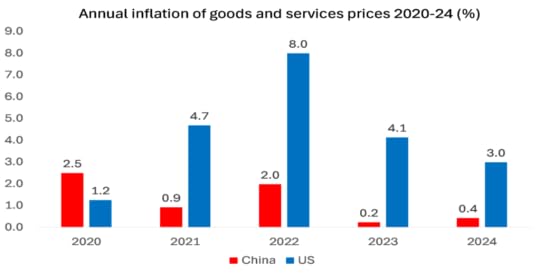

Ah, China’s Western critics say, but if you compare nominal GDP growth, which includes inflation, then US GDP rose 5.3% while China’s GDP rose only 4.2%. So in nominal terms China’s economy reached $18.6 trillion in 2024, compared to $29 trillion in the US, two-thirds below the US, compared to 75% in 2021. But this is a bogus comparison. The GDP gap in nominal terms widened partly because the dollar strengthened in world markets against the yuan and so boosted the US nominal GDP in dollar terms, but mainly because US inflation was much higher than in China.

Many Western mainstream economists argue that ‘moderate’ inflation is good for an economy. You see, if there is deflation (falling prices), then consumers may spend less on goods and services and save their money in the hope that prices will fall further and so economic growth will slow. Sure, hyper or accelerating inflation is bad news because people’s living standards will dive, the argument goes. But what is good is ‘moderate and steady’ inflation for capitalist enterprises to give them room to raise prices to maintain profits.

This is another ludicrous argument to justify the inability of Western monetary authorities to control price inflation. In no way is inflation good for working people. As one recent visitor to China put it: “Yes, it was absolutely horrible while I was in China – I only had to pay $13 for a meal for 2 people at a nice restaurant, $2.30 for 30 large eggs and $4 for a 30min taxi ride.” As another commented: “Everyone in the west is enjoying the rising cost of living. It’s a shame that the Chinese don’t have the chance to enjoy this.”

In reviewing China’s economy for the ‘two sessions’, Western economists bang on about the impending economic crisis in China from ‘deflation’, ‘rising debt’, ‘property market collapse’, ‘under-consumption and over-capacity’ etc. These supposed problems are not only lowering China’s growth prospects, but could even cause a crash and an outright slump. These arguments have been bandied about for decades and I have discussed their (in)validity in numerous posts.

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2024/04/10/chinas-unfair-overcapacity/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2025/01/14/the-exceptional-economy/

But let’s deal yet again with the argument that China’s growth success is totally dependent on investment in manufacturing for export and not on domestic consumption and unless China reduces its investment to avoid ‘over-capacity’ and instead develops a Western-style consumer economy, then it is destined for stagnation, so-called ‘Japanification’.

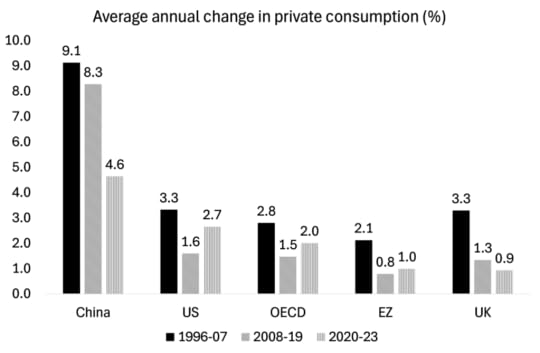

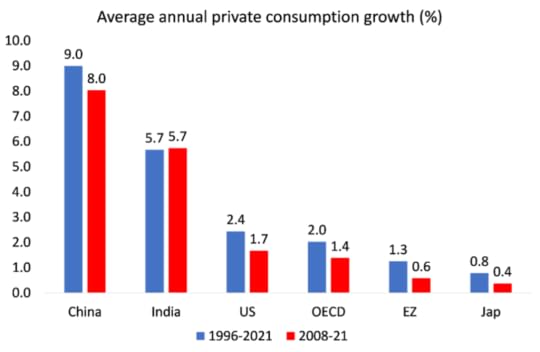

First, it is not true that China’s economy is growing at the expense of household consumption. Private consumption growth in China has been much faster than in the major economies. That’s because faster economic growth is driven by faster investment growth. I repeat from previous posts: investment leads consumption over time, not vice versa as mainstream economics thinks (here the mainstream is even going against Keynes).

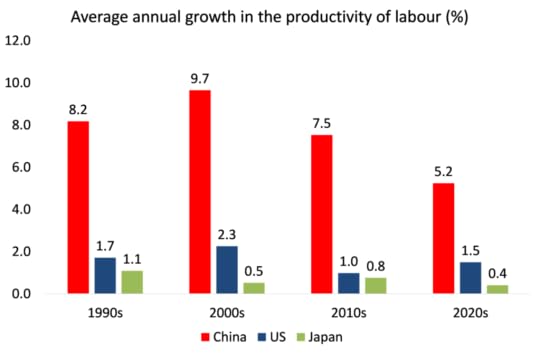

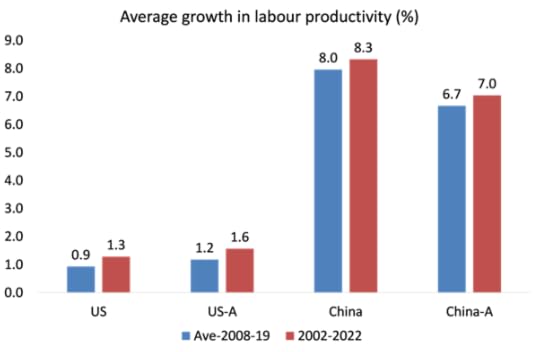

As for Japanification – China is not stagnating like Japan. Take productivity growth. Even though China’s growth in labour productivity has slowed in the last two decades, it is still more than four times higher than in the US and six times higher than in Japan.

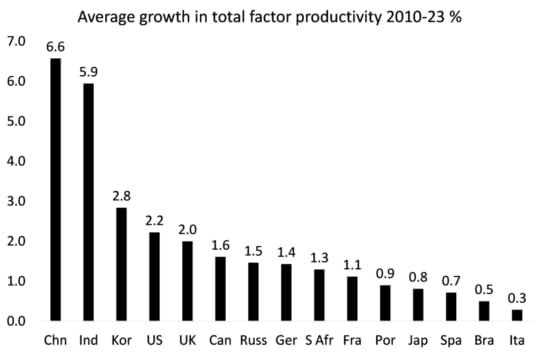

Total factor productivity (TFP) is a measure of how efficiently labour and capital are used to generate output. According to the US Conference Board, China’s TFP growth has been three times higher than the US and six times higher than Japan in the last decade or so.

Liu Qiao, dean of Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, reckons that China’s average annual TFP growth has declined from 4 per cent to 1.8 per cent between 2010 and 2019. But even on his measure, TFP growth is still higher than the US at 0.5 per cent per year for the past 20 years. If labour productivity growth stays at about 4-5% a year and TFP growth stays around 2-3% a year from hereon, then 5% real GDP growth is achievable over the rest of this decade and through the next five-year plan, even as the working population declines.

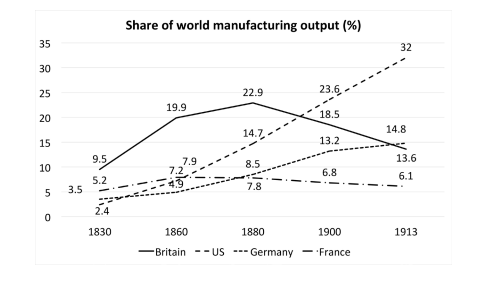

China has had the world’s largest manufacturing sector by output for 15 years running, reaching $5.58 trillion last year and contributing 36% of GDP. By contrast, US manufacturing accounts for just 10% of GDP, or $2.93 trillion. China’s economy is now driven by technological investments, no longer by unproductive investment in real estate, what the Chinese economic strategists call the “new quality productive forces”. More electric vehicles are on the road in China than in the US, and Beijing’s roll-out of 5G telecommunications networks has been much faster. China’s home-grown airliner, the C919, is on the cusp of mass production and appears ready to enter a market currently dominated by Boeing and Airbus. The BeiDou satellite navigation system is on par with GPS in coverage and precision.

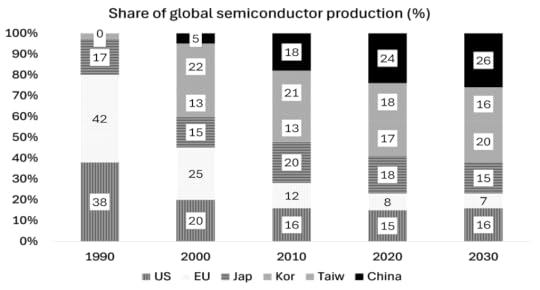

China also beats the US in industrial robot density, with 470 robots installed per 10,000 employees in 2023 compared with 295 in the US. China is also about to match the US in patents with its global share rising from 4% in 2000 to 26% in 2023, while the US share dropped by more than 8% points. And China’s semiconductor production is one-quarter of global output compared to 16% in the US and 7% in Europe.

Since 2012, the Chinese Academy of Engineering (CAE) has compiled rankings for nine major manufacturing economies – including China and the US – in terms of scale, quality, structural optimisation, innovation and sustainability. In 2012, China scored 89 points, lagging the US (156), Japan (126) and Germany (119). In 2023, China was still in fourth place but had significantly narrowed the gap; the US, Germany, Japan and China scored a respective 189, 136, 128 and 125. The US may still lead in new ideas but China is leading in applying them effectively, as the Deep Seek AI story shows.

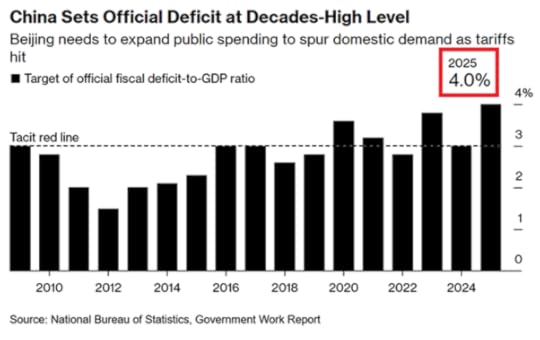

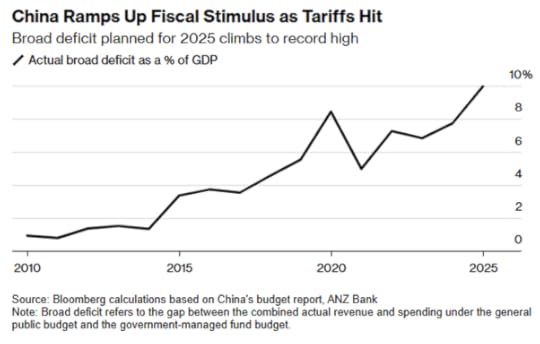

At the NPC, the Chinese leaders set the 2025 GDP growth target at “around 5%”, keeping the same pace as the prior year. Li Qiang announced plans to boost domestic demand by expanding fiscal spending. The central government will increase borrowing to do so, with the official government deficit rising to 4% of GDP, the highest ratio in 30 years.

Also defence spending will rise by 7.2%, matching last year’s growth. So the overall budget deficit will increase to near 10% of GDP. Regarding inflation, China is lowering its annual target to around 2% for the first time in over two decades. With wages rising at more than double that rate, average real incomes will continue to rise.

Why has China succeeded in avoiding slumps including the Great Recession and in the pandemic? Why has it motored ahead with unprecedented growth rates in such a large economy, while other large so-called emerging economies like Brazil or even India have failed to close the gap with the major advanced capitalist economies?

It’s because, although China has a large capitalist sector, mainly based in the consumer goods and services sectors, it also has the largest state sector in any major economy, covering finance and key manufacturing and industrial sectors, with a national plan guiding and directing both state enterprises and the private sector on where to invest and what to produce. Any slump in its private sector is compensated for by increased investment and production in the state sector – profit does not rule, social objectives do.

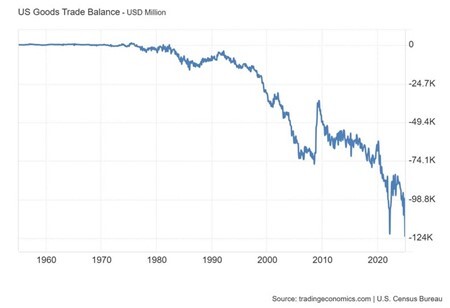

Now there is a new challenge for the Chinese economy. The government is gearing up for Trump’s trade war. Trump’s increased tariffs on Chinese exports to the US and sanctions on Chinese technology are major threats to China’s growth targets. China is diversifying its trading partners, but the US is still China’s largest export market (15%).

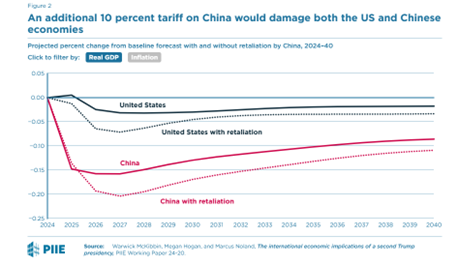

JPMorgan reckons that the contraction in China’s exports to the US from Trump’s tariffs will reduce GDP growth by 0.6 percentage points over 2025-27, with the majority of the impact being felt in 2026-27. As US companies look for domestic production to substitute for more costly imports, this could dampen China’s GDP growth further over 2028-29.

China could combat the rise in the prices of its goods sold to the US by devaluing the yuan, but that could lead to an inflation shock. So instead the NPC is going for fiscal and monetary stimulus worth about 3% of GDP. It remains to be seen if that will boost domestic production and consumption enough to compensate for any GDP losses from trade.

March 5, 2025

Trump’s ‘little disturbance’

Speaking to the US Congress yesterday after 100 days in office, President Donald Trump claimed that the new tariffs on imports from the US’s biggest trading partners would cause “a little disturbance”. But soon that would be over and “tariffs are about making America rich again and making America great again,” he said. “It’s happening, and it will happen rather quickly.”

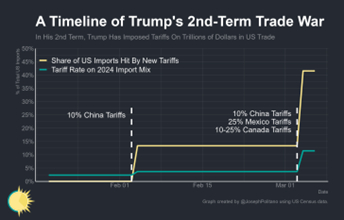

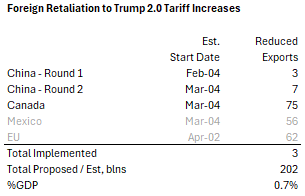

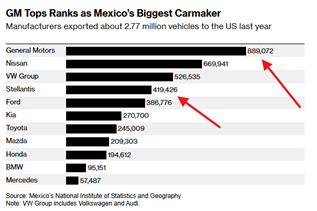

Indeed, very quickly. Yesterday, Trump imposed 25% tariffs on goods imported from Canada and Mexico into the US and an additional 10% tariff on Chinese imports, leaving all of America’s top three trade partners facing significantly higher barriers. The moves drew an immediate response from Beijing, which said it would levy a 10-15% tariff on US agricultural goods, ranging from soya beans and beef to corn and wheat from 10 March. Canada also unveiled tariffs on $107bn of US imports, starting with $21bn of imports immediately. “Canada will not let this unjustified decision go unanswered,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said. The levies against Ottawa are set at 25% except for Canadian oil and energy products, which face a 10% tariff. Canada accounts for about 60% of US crude imports.

China also targeted US companies, placing ten companies on a national security blacklist and slapping export controls on 15 others. It also banned US biotech company Illumina from exporting its gene-sequencing equipment to China. Beijing had added Illumina to its “unreliable entities” list last month in response to Trump’s initial barrage of tariffs.

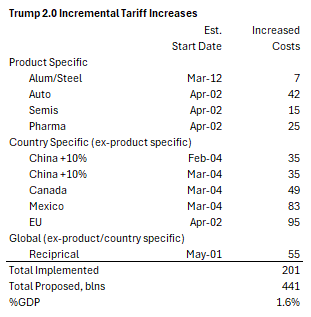

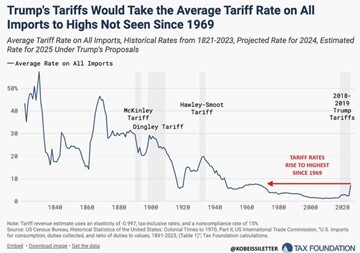

All the planned tariffs would take the US tariff rate to above 20% in just a few weeks, the highest since pre-WWI. As Joseph Politano points out, the costs of these actions are enormous, covering $1.3trn in US imports or roughly 42% of all goods brought into the United States, or the single-largest tariff hike since the infamous Smoot-Hawley Act of nearly a century ago.

The tariffs will drive up US prices for key raw materials like gasoline, fertilizers, steel, aluminum, wood, plastic, and more. Groceries, especially fresh fruits and vegetables from Mexico, will become harder to find. Manufacturing industries reliant on complex integrated North American supply chains—vehicles, computers, chemicals, airplanes, and more—could grind to a halt if those links are forcibly severed. Costs could spike for phones, laptops, and appliances where production is particularly concentrated in China and Mexico. Exporters will be hurt by increased costs for raw materials, currency appreciation, and upcoming retaliatory tariffs—all of which will cut into US economic activity.

The total costs of these tariffs would raise $160bn from US consumers and businesses paying more for their purchases of imported goods, with more to come. Trump’s Tuesday measures are only 40% of his proposed measures. If the next batch is implemented, it would raise the cost of imports to over $600bn, or 1.6% of GDP.

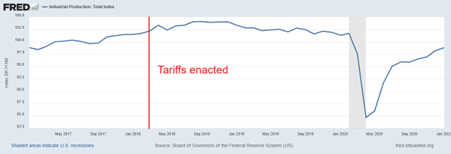

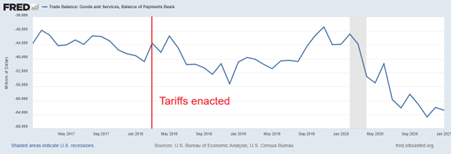

One economic argument for imposing tariffs on imported goods is to protect domestic firms from foreign competition. By taxing imports, domestic prices become relatively cheaper and citizens switch expenditure from foreign goods to domestic goods, thereby expanding the domestic industry. But this argument has little empirical support. The New York Fed recently analysed the impact of increased tariffs on domestic firms. It concluded that “extracting gains from imposing tariffs is difficult because global supply chains are complex and foreign countries retaliate. Using stock-market returns on trade war announcement days, our results show that firms experienced large losses in expected cash flows and real outcomes. These losses were broad-based, with firms exposed to China experiencing the largest losses.”

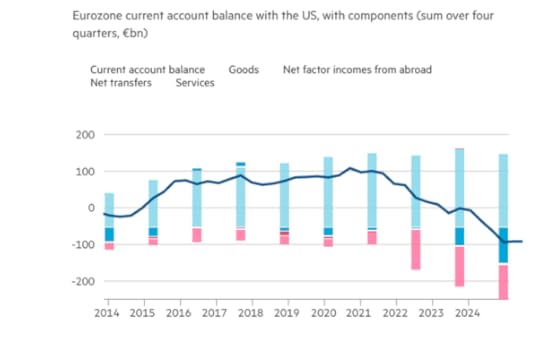

Moreover, as the Danish economist, Jesper Rangvid shows, Trump only looks only at bilateral trade in goods, ignoring trade in services and earnings from capital and labour. It so happens that the income the US derives from its exports of services at least to the Eurozone and the returns on capital and the wages of labour it has exported there offset its bilateral deficits in goods. The overall Eurozone bilateral current account balance with the US is close to zero.

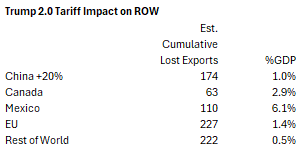

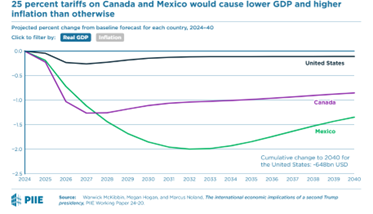

Far from Trump’s tariff barrage ‘making America great again’, it has every prospect of driving the US economy into a recession and the other major economies with it. The Kiel Institute reckons that EU exports to the US would drop by 15-17%, leading to “a significant” 0.4% contraction in the size of the EU economy, while US GDP would shrink by 0.17%. If there are tit-for-tat tariffs by the EU, that would double the economic damage and push inflation up by 1.5 percentage points. German manufacturing exports to the US would be the worst hit, dropping by almost 20%. While the exact magnitude of lost exports over time is unclear (given it will take time for supply chains to reset), if these levies persist it is likely to create a substantial drag on the GDPs of the major economies trading with the US.

The overall impact on US manufacturing could total nearly 1% of GDP in exports lost.

That’s one estimate. Yale University economists go further. They modelled the effect of the planned 25% Canada and Mexico tariffs and the 10% China tariffs, as well as the 10% China tariffs already in effect. They reckoned these tariffs would take the effective average tariff rate to its highest since 1943. Domestic prices would rise by over 1% pt from the current inflation rate, the equivalent of an average per household consumer loss of $1,600–2,000 in 2024$. They would lower US real GDP growth by 0.6% pt this year and take 03-0.4% pt off future annual growth rates, wiping out expected gains in productivity from AI infusion.

So worried is the International Chamber of Commerce in the US, that it reckoned that the world economy could face a crash similar to the Great Depression of the 1930s unless Trump rows back on his plans. “Our deep concern is that this could be the start of a downward spiral that puts us in 1930s trade-war territory,” said Andrew Wilson, deputy secretary-general of the ICC. So Trump’s measures may go well beyond “a little disturbance”.

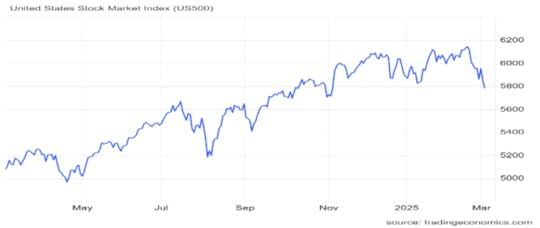

Even before the announcement of the new tariffs, there were significant signs that the US economy was slowing at some pace. The impact of increased import tariffs could be a tipping point for a recession. Wall Street thought so. When Trump announced the tariff measures, all the gains in the US stock market made since Trump’s election victory were wiped out.

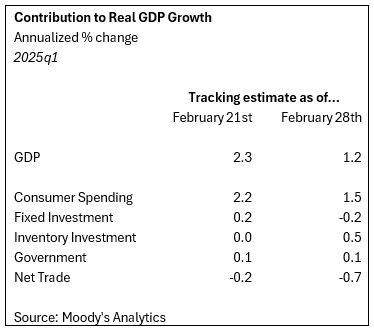

In a matter of weeks, the narrative over the US economy has shifted from the “exceptionalism” of the US economy to alarm about a sudden downturn in growth. Retail sales, manufacturing production, real consumer spending, home sales and consumer confidence indicators, are all down in the past month or two. Consensus forecasts for real GDP growth for Q1 2025 are now only an annualised 1.2%.

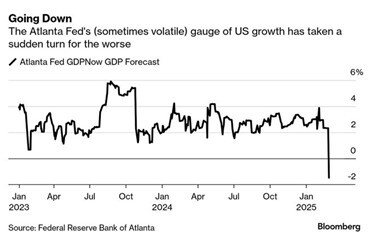

The closely followed Atlanta Fed’s GDP NOW tracker forecasts an outright contraction.

US manufacturing has been in recession for a year or more, but what is also worrying in the latest indicators of manufacturing activity was a significant rise in costs: “demand eased, production stabilized, and destaffing continued as companies experience the first operational shock of the new administration’s tariff policy. Prices growth accelerated due to tariffs, causing new order placement backlogs, supplier delivery stoppages and manufacturing inventory impacts”, Timothy Fiore, Chair of the ISM said. New orders fell the most since March 2022 into contraction territory and production slowed sharply. In addition, price pressures accelerated to the highest since June 2022.

But then the so-called exceptionalism of the US economy since the end of the pandemic was always a statistical illusion. One study reveals the real story for many American households on employment, wages and inflation. First, there is the near-record low unemployment on official figures, just 4.2%. But this figure includes as employed, homeless people doing occasional work. If the unemployed included those who can’t find anything but part-time work or who make a poverty wage (roughly $25,000), the percentage is actually 23.7%. In other words, nearly one of every four workers is functionally unemployed in America today. The official median wage is $61,900. But if you track everyone in the workforce — that is, if you include part-time workers and unemployed job seekers, the median wage is actually little more than $52,300 per year. “American workers on the median are making 16% less than the prevailing statistics would indicate.” In 2023, the official inflation rate was 4.1%. But the true cost of living rose more than twice as much — a full 9.4%. That means purchasing power fell at the median by 4.3% in 2023.

The European leaders’ answer to Trump’s tariff moves and his apparent withdrawal from supporting Ukraine in its war against Russia now appears to be preparations for more war. Global defence spending hit a record $2.2tn last year and in Europe it rose to $388bn, levels not seen since the ‘cold war,’ according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Martin Wolf, the liberal Keynesian economic guru of the Financial Times says “spending on defence will need to rise substantially. Note that it was 5 per cent of UK GDP, or more, in the 1970s and 1980s. It may not need to be at those levels in the long term: modern Russia is not the Soviet Union. Yet it may need to be as high as that during the build-up, especially if the US does withdraw.”

How to pay for this? “If defence spending is to be permanently higher, taxes must rise, unless the government can find sufficient spending cuts, which is doubtful.” But don’t worry, spending on tanks, troops and missiles is actually beneficial to an economy, says Wolf. “The UK can also realistically expect economic returns on its defence investments. Historically, wars have been the mother of innovation.” He then cites the wonderful examples of the gains that Israel and Ukraine have made from war: “Israel’s “start up economy” began in its army. The Ukrainians now have revolutionised drone warfare.” He does not mention the human cost involved in getting innovation by war. Wolf :“The crucial point, however, is that the need to spend significantly more on defence should be viewed as more than just a necessity and also more than just a cost, though both are true. If done in the right way, it is also an economic opportunity.” So war is the way out of economic stagnation.

Germany’s Chancellor-to-be Friedrich Merz (after winning the recent election) has adopted the same story. In a complete about-face from his election campaign, when he opposed any extra fiscal spending in order to ‘balance’ the government books, he is now promoting a plan to inject hundreds of billions in extra funding into Germany’s military and infrastructure, designed to revive and re-arm Europe’s largest economy. A new provision would exempt defence spending above 1 per cent of GDP from the “debt brake” that caps government borrowing, allowing Germany to raise an unlimited amount of debt to fund its armed forces and to provide military assistance to Ukraine. And he plans to introduce a constitutional amendment to set up a €500bn fund for infrastructure, which would run over ten years. Suddenly, there is plenty of cash and borrowing to be made available for arms and military ventures.

The UK’s plan is to double its ‘defence’ spending by cutting its aid programme to the poor countries of the world. Trump also has frozen US foreign aid. Global debt has hit $318trn with a rise of $7trn in 2024. Global debt to global GDP rose for the first time in four years – so debt rose faster than nominal GDP to reach 328% of GDP. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) warned that poor countries are under immense pressure as their debt loads continue to grow. Total debt in these economies jumped by $4.5 trillion in 2024, pushing total emerging market debt to an all-time high of 245% of GDP. Many of these poor economies now have to roll over a record $8.2 trillion in debt this year, with about 10% of it denominated in foreign currencies—a situation that could quickly turn dangerous if funding dries up. So more war and more poverty ahead.

March 2, 2025

Trump’s MAGA and deregulation

Trump sees the United States as just a big capitalist corporation of which he is chief executive. Just as he did when he was the boss in the TV show, the Apprentice, he thinks he is running a business and so can employ and fire people at his whim. He has a board of directors who advise and/or do his bidding (the American oligarchs and former TV presenters). But the institutions of the state are a hindrance. So Congress, courts, state governments etc are to be ignored and/or told to carry out the instructions of the CEO.

Like a good (sic) capitalist, Trump wants to free the US plc from any restraints on making profits. For Trump, the corporation and its shareholders, the sole objective is profits, not the needs of society in general, nor higher wages for the employees of Trump’s corporation. That means no more wasteful expenditure on mitigating global warming and avoiding damage to the environment. The US corporation should just make more profits and not be concerned with such ‘externalities’.

Like the real estate agent he is, Trump thinks the way to boost his corporation’s profits is make deals to take over other corporations or to make agreements on prices and costs to ensure maximum profits for his corporation. Like any big corporation, Trump does not want any competitors to gain market share at his expense. So he wants to increase costs for rival national corporations, like Europe, Canada and China. He is doing this by raising tariffs on their exports. He is also trying to get other less powerful corporations to agree terms on taking more of US corporations’ goods and services (health companies, GMO food etc) in trade agreements (eg the UK). And he aims to increase the US corporation’s investments in profit-making sectors like fossil fuel production (Alaska, fracking, drilling), proprietary technology (Nvidia, AI) and, above all, in real estate (Greenland, Panama, Canada Gaza).

Any corporation wants to pay less taxation on its income and profits, and Trump aims to deliver that for his US corporation. So he and his ‘adviser’ Musk have taken a wrecking ball to government departments, their employees and any spending on public services (even defence) to ‘save money’, so that Trump can cut costs ie reduce taxes on corporate profits and taxes on high-paid super-wealthy individuals who sit on his US corporation board and carry out his executive orders.

But it’s not just taxes and the costs of government that must be dismantled. The US corporation must be freed of ‘petty’ regulations on business activities like: safety rules and working conditions in production; anti-corruption laws and laws against unfair trading measures; consumer protection from scams and theft; and controls on financial speculation and dangerous assets like bitcoin and cryptocurrencies. There should be no restraint on Trump’s US corporation to do what it wants. Deregulation is key to Making America Great Again (MAGA).

Trump has directed that the Department of Justice pause all enforcements under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (an anti-bribery and accounting practices legislation intended to maintain integrity in business dealings), for 180 days. Trump aims at eliminating ten regulations for each new regulation issued to “unleash prosperity through deregulation.” He has fired the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and directed all employees to “cease all supervision and examination activity”. The CFPB was created in the wake of the 2007-08 financial crisis and is tasked with writing and enforcing rules applicable to financial services companies and banks, prioritising consumer protection in lending practices.

Trump wants more speculative tokens, more crypto projects (as launched by his sons) and has started his own memecoin. Newly proposed changes to accounting guidance would make it much easier for banks and asset managers to hold crypto tokens — a move that pulls this highly volatile asset closer to the heart of the financial system.

Yet it’s only two years since the US was on the brink of its most serious set of bank failures since the financial storm of 2008. A clutch of regional banks, some the size of Europe’s larger lenders, hit the skids, including Silicon Valley Bank, whose demise came close to sparking a full-blown crisis. SVB’s crash had several immediate causes. Its bond holdings were crumbling in value as US interest rates pushed higher. With just a few taps on an app, the bank’s spooked and interconnected tech customer base yanked out deposits at an unsustainable pace, leaving multimillionaires crying out for federal assistance. This deregulation is “a huge mistake and will be dangerous”, said Ken Wilcox, who was chief executive of SVB for a decade up to 2011. “Without good banking regulators, banks will run amok,” he told the FT’s sister publication The Banker.

Trump’s deregulation mantra for his US corporation is now being echoed by the EU and UK corporate states. The EU and the UK have already dropped agreed new international capital requirements for banks under Basel III, following the US’s lead. Former ECB chief and Goldman Sachs banker Mario Draghi is now yelling for an end to regulations operated by EU member states, which according to him “are far more damaging for growth than any tariffs the US might impose — and their harmful effects are increasing over time. The EU has allowed regulation to track the most innovative part of services — digital — hindering the growth of European tech firms and preventing the economy from unlocking large productivity gains.”

In the UK, Chancellor (finance minister) Rachel Reeves asked that the financial regulators “tear down regulatory barriers” that hold back economic growth, suggesting that post-financial crash regulation has “gone too far”. The chair of the UK’s regulatory body for commercial trading, the Competition and Markets Authority, has been replaced with the former UK head for Amazon! The head of the UK financial ombudsman has also recently resigned, due to clashes over the government’s pro-business approach. Reeves wants a full audit of Britain’s 130 or so regulators to whether some should be scrapped. Reeves told senior bankers that “for too long, we have regulated for risk rather than growth, and that is why we are working with regulators to understand how reform across the board can kick-start economic growth.” That means de-regulate and risk-taking is the order of the day.

Now the EU’s Green Deal, policies supposedly aimed at decarbonising the economy, are being watered down to compete with Trump’s US corporation. The EU commissioner responsible, Ribera, has already ‘postponed’ an anti-deforestation law for a year. Now she wants to cut the number of small and medium companies affected by existing environmental regulations and reduce reporting requirements, thus saving apparently 20% of the cost of regulation. Brussels has estimated the cost of complying with EU rules at €150bn per year, an amount it wants to slash by €37.5bn by 2029. “What we need to avoid is using the word simplification to mean deregulation,” said Ribera. “I think that simplification may be very fair . . . to see how we can make things easier.” But as Heather Grabbe, senior fellow at economic think-tank Bruegel says, these proposed changes “seem to go far beyond simplification which would make reporting easier, and they seem to be moving away from transparency, which is what investors have been asking”.

As for controlling fossil fuel production, forget it. Karen McKee, head of oil and gas major ExxonMobil’s product solutions business, told the FT that future investments in Europe would depend on regulatory clarity from Brussels. “What we’re really looking for now is action” and for Brussels to strip its “well intended” regulation back and allow industry to innovate, she said. “Competitiveness is the focus right now because it’s simply a crisis. We are achieving decarbonisation in Europe through deindustrialisation,” McKee complained. Apparently, the failure of European capital to invest and grow is all down to regulations on fossil fuel production and hindering corporations from competing.

It seems that all the governments are swallowing Trump’s strategy for his US corporation. You can maximise profits if you remove all restraints and make deals. What Trump, the EU and the UK ignore is that de-regulation has never delivered economic growth and increased prosperity. On the contrary, it has merely increased the risk of chaos and collapse. And that means eventually, it damages profitability.

We only have to remember the ludicrous position taken by Britain’s Labour government before the global financial crash in the early 2000s to adopt what they called ‘light-touch regulation’ of the banks. Ed Balls, then the City Minister (now a talk show host) in his first speech to the City of London said “London’s success has been based on three great strengths – the skills, expertise and flexibility of the workforce; a clear commitment to global, open and competitive markets; and light-touch principle-based regulation.” The then chancellor and soon to be prime minister, Gordon Brown spoke to the bankers and said “Today our system of light-touch and risk-based regulation is regularly cited – alongside the City’s internationalism and the skills of those who work here – as one of our chief attractions. It has provided us with a huge competitive advantage and is regarded as the best in the world.” What happened next and where is Britain now?

Rachel Reeves has learnt nothing from the 2008 crash. In her first Mansion House speech as UK Chancellor last November she echoed the call for deregulation. But as Mariana Mazzucato pointed out, according to the OECD, the UK ranks second as the least regulated country in product regulation and fourth least for employment. And the World Bank continues to rate the UK one of the highest in terms of ‘ease to do business’.

But now it seems, in order to compete with Trump’s US corporation, Europe and the UK must not only engage in a ‘race to the bottom’ over taxes (Reeves refuses to finance public services with a wealth tax or corporate profits tax – on the contrary she wants to cut the latter), Europe and the UK must also engage in a race to the bottom on deregulation. Even the Bank of England’s economists are worried about ‘competitive deregulation’ as it would inevitably increase the risk of a financial meltdown.

Anybody who has read this blog over the years knows that I think regulation over capitalist enterprises does not work, as proven by the global financial crash in 2008, the US regional bank implosion in 2023 and many other examples in finance, business and services. There can be no real effective ‘regulation’ without public ownership controlled by democratic workers organisations. Deregulating may not increase the risk of financial crashes, or more industrial accidents or consumer scams or more corruption – these happen anyway. But it certainly won’t deliver more economic growth and better living standards and public services.

Indeed, that is why Trump’s corporate strategy is set to fail. Increased tariffs on other corporations may give Trump’s US corporation a temporary price advantage but that could soon be eaten away by higher costs for things and services provided by rival national corporations that Trump’s firm still needs and must buy. Accelerating inflation is the risk. And that won’t go down well with the corporation’s employees. Moreover, making deals on trade and real estate or cutting taxes on profits has never led to significant rises in economic growth. That depends on investment in productive sectors. Most of the cuts in taxes will more likely end up in financial speculation by corporations and the super-rich.

If a corporate strategy fails, the CEO normally has to take responsibility and the corporation’s directors and shareholders can turn against the CEO. And if the corporation cannot deliver better wages and conditions for its workers, but only higher inflation and collapsing public services, that could lead to serious problems within the corporation. Watch this space.

February 24, 2025

Russia-Ukraine war: three years on

Ukraine: a human disaster

Today marks the end of the third year of the Ukraine-Russia war. After three years of war, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused staggering losses to Ukraine’s people and economy. There are various estimates of the number of Ukrainian civilians and military casualties (deaths plus injuries): 46,000 civilians and maybe 500,000 soldiers. Russian military casualties are about the same. Millions have fled abroad and many more millions have been displaced from their homes within Ukraine. A confidential Ukrainian assessment earlier in 2024, reported by the Wall Street Journal, placed Ukrainian troop losses at 80,000 killed and 400,000 wounded. According to government figures, in the first half of 2024, three times as many people died in Ukraine as were born, the WSJ reported. In the last year, Ukrainian losses have been five times higher than Russia’s, with Kyiv losing at least 50,000 service personnel a month.

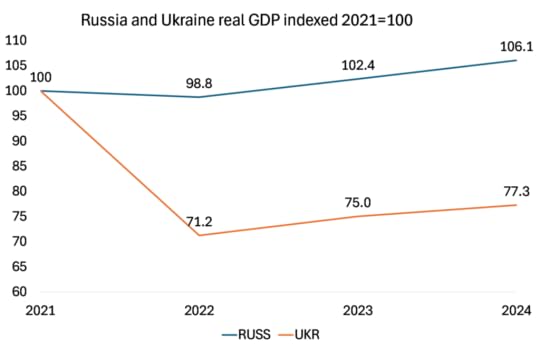

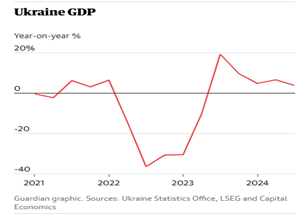

Ukraine’s GDP is down 25% and an additional 7.1 million Ukrainians now live in poverty.

The damage to those staying in Ukraine is immense. Learning losses by Ukrainian children are a particular worry: Ukraine will end up with lower quality additions to its workforce due to war-caused (and prior to that, Covid-caused) disruptions in the learning process. These losses are estimated to be in the order of $90 billion, or almost as much as the losses in physical capital to-date. Studies also show that a war during a person’s first five years of life is associated with about a 10% decline in mental health scores when they are in their 60s and 70s. It’s not just war casualties and the economy that’s the problem, but also the long-term damage to those Ukrainians staying.

Despite the war, there has been some modest economic recovery in the last year. Energy exports have jumped. Ukraine’s ports on the Black Sea are still functioning and trade is flowing west along the Danube, and to a lesser extent by train. Meanwhile, agriculture has staged a recovery. Even so, manufacturing of iron and steel still remains at a fraction of its prewar level; down from 1.5m tonnes a month before the war to just 0.6m a month.

But Ukraine badly lacks able-bodied people to produce or to go to war. Ukraine’s unemployment rate was 16.8% in January, but that still leaves a shortage of workers because skilled people have left the country and most others have been mobilised into the armed forces. So bad is the situation that there has been talk of mobilising 18-25 years olds who are currently exempt, but this is highly unpopular and would reduce civilian employment even more.

Ukraine is still totally dependent on support from the West. It needs at least $40bn a year in order to sustain government services, support its population and maintain production. It is relying on the EU for such civil funding, while relying on the US for all its military funding – a straight ‘division of labour’. In addition, the IMF and World Bank have offered monetary assistance but, in this case, Ukraine has to show it has ‘sustainability’, ie it is able at some point to pay back any loans. So if bilateral loans from the US and EU countries (and it is mainly loans, not outright aid) do not materialise, then the IMF cannot extend its lending programme.

That brings us back to what will happen to Ukraine’s economy, if and when the war with Russia comes to an end. According to the latest estimate of the World Bank, Ukraine will need $486bn over the next ten years to recover and rebuild – assuming the war ends this year. That’s nearly three times its current GDP. Direct damages from the war have now reached almost $152 billion, with about 2 million housing units – about 10% of the total housing stock of Ukraine – either damaged or destroyed, as well as 8,400 km (5,220 miles) of motorways, highways, and other national roads, and nearly 300 bridges. About 5.9 million Ukrainians remained displaced outside of the country and internally displaced persons were around 3.7 million.

What is left of Ukraine’s resources (those not annexed by Russia) have been sold off to Western companies. Overall, 28% of Ukraine’s arable land is now owned by a mixture of Ukrainian oligarchs, European and North American corporations, as well as the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia. Nestle has invested $46 million in a new facility in western Volyn region while German drugs-to-pesticides giant Bayer plans to invest 60 million euros in corn seed production in central Zhytomyr region. MHP, Ukraine’s biggest poultry company, is owned by a former adviser to Ukrainian president Poroshenko. MHP has received more than one-fifth of all the lending from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in the past two years. MHP employs 28,000 people and controls about 360,000 hectares of land in Ukraine — an area bigger than EU member Luxembourg.

The Ukrainian government is committed to a ‘free market’ solution for the post-war economy that would include further rounds of labour-market deregulation below even EU minimum labour standards i.e sweat shop conditions; and cuts in corporate and income taxes to the bone; along with full privatisation of remaining state assets. However, the pressures of a war economy have forced the government to put these policies on the back burner for now, with military demands dominating.

The aim of the Ukraine government, the EU, the US government, the multilateral agencies and the American financial institutions now in charge of raising funds and allocating them for reconstruction is to restore the Ukrainian economy as a form of special economic zone, with public money to cover any potential losses for private capital. Ukraine will also be made free of trade unions, severe business tax regimes and regulations and any other major obstacles to profitable investments by Western capital in alliance with former Ukrainian oligarchs.

Ukrainian sources estimate the cost of restoring infrastructure: financing the war effort (ammunition, weapons, etc.); losses of housing stock, commercial real estate, compensation for death and injury, resettlement costs, income support, etc.) and lost current and future income will reach $1trn, or six years of Ukraine’s previous annual GDP. That’s about 2.0% of EU GDP per year or 1.5% of G7 GDP for six years. By the end of this decade, even if reconstruction goes well and assuming that all the resources of pre-war Ukraine are restored (ie eastern Ukraine’s industry and minerals are in the hands of Russia), then the economy would still be 15% below its pre-war level. If not, recovery will be even longer.

Russia: the war economy

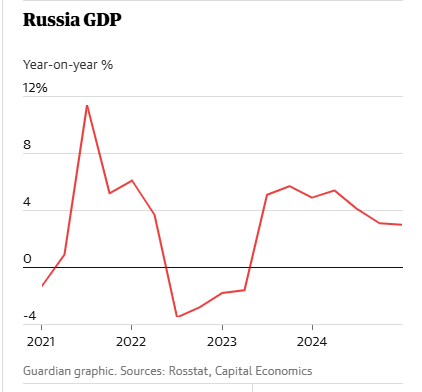

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 to take over the four Russian-speaking provinces in the Donbass in eastern Ukraine has ironically given a boost to the economy. In 2023, real GDP growth was 3.6% and over 3% in 2024. Russia’s war economy is holding up.

Over the past three years of war, Russia has managed to steer through sanctions, while investing nearly a third of its budget in defence spending. It’s also been able to increase trade with China and sell its oil to new markets, in part by using a shadow fleet of tankers to skirt the price cap that Western countries had hoped would reduce the country’s war chest. Half of its oil and petroleum was exported to China in 2023. It became China’s top oil supplier. Chinese imports into Russia have jumped more than 60% since the start of war, as the country has been able to supply Russia with a steady stream of goods including cars and electronic devices, filling the gap of lost Western goods imports. Trade between Russia and China hit $240 billion in 2023, an increase of over 64% since 2021, before the war.

However, the war has intensified an acute labour shortage. Like Ukraine, Russia is now desperately short of people – if for different reasons. Even before the war, Russia’s workforce was shrinking due to natural demographic causes. Then at the start of the war in 2022, about three-quarters of a million Russian and foreign workers, the middle class in IT, finance, and management, left the country. Meanwhile, the Russian army is recruiting tens of thousands of working-age men. Somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 workers join the army every month, about 0.5 percent of the total supply. That has benefited those Russian workers not in the armed forces with security of employment as managers are reluctant to let anyone go.

Wages have soared by double digits, poverty and unemployment are at record lows. For the country’s lowest earners, salaries over the last three quarters have risen faster than for any other segment of society, clocking an annual growth rate of about 20%. The government is spending massively on social support for families, pension increases, mortgage subsidies and compensation for the relatives of those serving in the military.

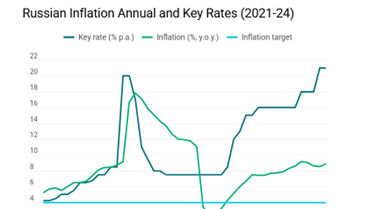

But inflation has spiralled and the ruble has depreciated significantly against the dollar, forcing the Russian central bank to hike its interest rate to over 20%.

A war economy means that the state intervenes and even overrides the decision-making of the capitalist sector for the national war effort. State investment replaces private investment. Ironically, in Russia’s case this has been accelerated by Western companies’ withdrawal from Russian markets and by the sanctions. The Russian state has taken over foreign entities and/or resold them to Russian capitalists committed to the war effort.

Spending on new construction, higher-tech equipment, new kit has hit a 12-year high of 14.4 trillion rubles ($136.4 bn), up 10 percent from the previous year. Investment growth rate topped the GDP growth rate by a wider margin than at any point over the previous 15 years, according to the Moscow-based Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-term Forecasting.

The main destinations for the country’s hitherto-unseen investment are import substitution, eastward infrastructure, and military production. Mechanical engineering, which includes manufacturing finished metal products (weapons), computers, optics and electronics, and electrical equipment, is one of the fastest-growing areas for investment.

Many Western economists are forecasting a collapse in the Russian economy – as they have been saying for the last three years. The acute labour shortage, persistent and rising inflation caused by soaring military expenditure and ever-tightening sanctions will – it is claimed – finally bring about an economic crisis that will force Moscow to abandon its aims in Ukraine and bring about an end to the war on terms more acceptable to Kyiv and its allies.

Many analysts have attributed these signs of overheating to elevated spending on the war in Ukraine, pointing to record-high military expenditure which is expected to have reached over 7% of GDP in 2024. With defence spending expected to rise by nearly 25% this year, accounting for around 40% of federal government expenditure, some have raised the prospect of Russia slipping into ‘stagflation’, combining high inflation with low to no growth.

But despite fighting the most intense war in Europe since 1945, Moscow has managed to fund the war with modest budget deficits of between 1.5–2.9% of GDP since 2022. As a result, the Kremlin has barely had to borrow to fund the war. Tax revenues generated by domestic activity have soared since the war began. At around 15% of GDP, Russia has the smallest state debt-to-GDP ratio of the G20 economies. So, despite being cut off from most external sources of capital, Russia remains more than capable of financing domestic investment and government expenditure with its own resources.

Over the past two years, Russia has recorded a surplus on its current account of around 2.5% of GDP. For as long as Russia can continue to export large volumes of oil, this is unlikely to change. Russia’s oil and gas revenues jumped by 26% last year to $108 billion even as daily oil and gas condensate production declined in 2024 by 2.8%, according to Russian government officials cited by Reuters. Despite remaining the world’s most-sanctioned country in 2024, Russia exported a record 33.6 million tons of liquefied natural gas (LNG) that year, which is a 4% increase from the previous year.

The Institute of International Finance (IIF) has forecast a decrease in Russia’s fiscal breakeven oil price (the amount to balance budget spending) to $77 per barrel by 2025, supported by a recovery in oil and gas revenues. At the same time, the external breakeven oil price (the price needed to balance the external current account), at $41 per barrel, is the second lowest among major hydrocarbon exporters. That means the current Urals oil price more than meets these breakeven points.

But none of this ‘war economy’ investment will support Russia’s long-term productivity growth. Russia’s war economy will revert to capitalist accumulation when the war ends. And the Russian economy remains fundamentally natural resource linked. It relies on extraction rather than manufacturing. War production is basically unproductive for capital accumulation over the long run. Russia remains technologically backward and dependent on high-tech imports. Even with massive fiscal stimuli, it has yet to produce technologies fit for a competitive export market beyond arms and nuclear energy, with the former already sanctioned and the latter on the brink of being so. Russia is not a substantial player in any of the cutting-edge technologies, from artificial intelligence to biotechnology.

The demographic trough, the declining quality of university education and severed ties with international schools and a brain drain exacerbate these problems. The technological gap will likely widen, with Russia increasingly relying on Chinese imports and reverse engineering (copying). Russia’s potential real GDP growth is probably no more than 1.5% a year as growth is restricted by an ageing and shrinking population and low investment and productivity rates.

The Russian war economy is well placed to continue the war for several years ahead if necessary. But when the war is over, Putin may face a significant slump in production and employment. The underlying message is that the weakness of investment, productivity and profitability of Russian capital, even excluding sanctions, means that Russia will remain feeble economically for the rest of this decade.

The peace

President Trump has declared that he is seeking a peace settlement through direct negotiations with Russia. That would mean the end of US financial and military support for Ukraine. The current Ukraine leadership is opposing any deal that means the loss of territory and any veto on future membership of NATO. European leaders have declared that they will back Ukraine and continue to finance the war and provide military support.

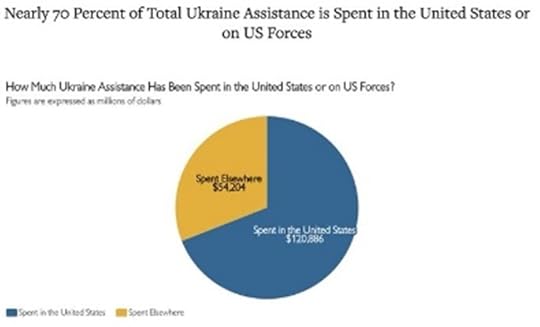

Trump wants back what the US government has spent on Ukraine up to now, as well collateral for future spending to reconstruct the economy. He has complained about the huge transfers of funds to Ukraine unaccounted for. This is misinformation. The majority of the funds the US allocated for Ukraine stayed at home to fund the domestic defence industrial base and replenish US stockpiles. US arms manufacturers are making huge profits from this war.

Now Trump is demanding that Ukraine sign over 50% of its ‘rare earth’ mineral rights to the US in return for delivering the $500bn needed for post-war reconstruction. Trump: “I want them to give us something for all of the money that we put up and I’m gonna try and get the war settled and I’m try and get all that death ended. We’re asking for rare earth and oil, anything we can get.” As US senator Lindsey Graham said: “This war’s about money…The richest country in all of Europe for rare earth minerals is Ukraine, two to seven trillion dollars worth…So Donald Trump’s going to do a deal to get our money back, to enrich ourselves with rare minerals…” The problem is that around half these deposits (worth some $10-12 trillion) are in Russian-controlled areas.

All this is just another indication that Ukraine’s assets are going to be carved up by the Western powers. Last month, Ukraine President Zelenskyy signed a new law expanding the privatisation of state-owned banks in the country. It follows the Ukrainian government’s announcement in July of its ‘Large-Scale Privatisation 2024’ programme that is intended to drive foreign investment into the country and raise money for Ukraine’s struggling national budget. Large assets slated for privatisation currently include the country’s biggest producer of titanium ore, a leading producer of concrete products and a mining and processing plant. Ukraine envisaged privatising the country’s roughly 3,500 state-owned enterprises in a law of 2018, which said foreign citizens and companies could become owners. Hundreds of smaller-scale enterprises are now being privatised, bringing in revenues of UAH 9.6bn (£181m) in the past two years. This involves a seven-year sub-programme called SOERA (state-owned enterprises reform activity in Ukraine), which is funded by USAID with the UK Foreign Office as a junior partner. SOERA works to “advance privatization of selected SOEs [state-owned enterprises], and develop a strategic management model for SOEs remaining in state ownership.”

British capital is also licking its lips. Recently-published UK Foreign Office documents noted that the war provides “opportunities” for Ukraine delivering on “some hugely important reforms”. “The UK is hoping to reap benefits for UK firms from Ukraine’s reconstruction”, observes a report on British aid to Ukraine earlier this year by the aid watchdog, ICAI.

Putin’s invasion has driven the Ukrainian people into the hands of a pro free market, anti-labour government that will allow Western capital to take over Ukraine’s assets and exploit its diminished workforce. Maybe that was inevitable – from pro-Russian and pro-West oligarchs before the war, now to Western capital afterwards.

The war has not only destroyed Ukraine; it has seriously weakened the European economy as the costs of production have rocketed with the loss of cheap energy imports from Russia. But it seems that the European leaders want to continue the war even if Trump pulls out. They are desperately scrambling for funds to do that and to provide more military aid to the beleaguered Ukrainian government. Some leaders are proposing to send troops to Ukraine. So ‘war not peace’.

Just as bad is the decision of NATO and Europe’s mainstream leaders to double defence spending from about an average 1.9% of GDP by the end of the decade, supposedly to resist imminent Russian attacks if Putin gets a winning peace this year. This is ludicrously justified on the grounds that spending on ‘defence’ “is the greatest public benefit of all” (Bronwen Maddox, director of Chatham House, the international relations ‘think-tank’, which mainly presents the views of the British military state). Maddox concluded that: “the UK may have to borrow more to pay for the defence spending it so urgently needs. In the next year and beyond, politicians will have to brace themselves to reclaim money through cuts to sickness benefits, pensions and healthcare…In the end, politicians will have to persuade voters to surrender some of their benefits to pay for defence.” We get the same message from the leader of the winning party in the German election.

This will mean a huge diversion of investment from badly needed public services and benefits and from technological investment into unproductive and destructive arms production. That puts a huge uncertainty about Europe’s future as a leading economic entity through the rest of this decade and beyond.

February 22, 2025

Germany: drained of power; der Kraft beraubt

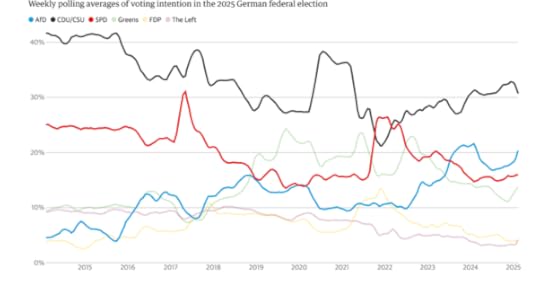

Germany holds a snap election on Sunday and the current coalition government of Social Democrats (SPD), Greens and the Free Democrats (FDP) is heading for a heavy defeat. The main opposition conservative Christian Democrat-Christian Social Union alliance is polling about 30% in voting intentions, while the SPD is down to 16% (from 26% last time) and the Greens at 13% (from 15%), with the FDP likely unable to muster even the 5% share required to get seats in the Bundestag (parliament).

However, the CDU-CSU share of the vote is well down from its usual 35-40% that it gets in elections. That’s because the anti-immigrant, anti-EU, racist Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) party has doubled its previous electoral support in the opinion polls to 20%. There are now two left parties – the traditional Die Linke, mainly supported in the old eastern Germany and the breakaway Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW), named after its leader. The latter gained a sizeable share of votes in recent state (Lander) elections, but has since faded in the polls and seems unlikely to get federal parliament seats in this election; Der Linke could just sneak in.

CDU leader Friedrich Merz will probably become chancellor with his alliance taking the largest number of seats, but with not a majority. So he will need at least one coalition partner. The CDU has said it will maintain the Brandmauer – firewall – policy of not going into alliance with the AfD. So he will look to bring in the Greens, or have a “grand coalition” with the Social Democrats.

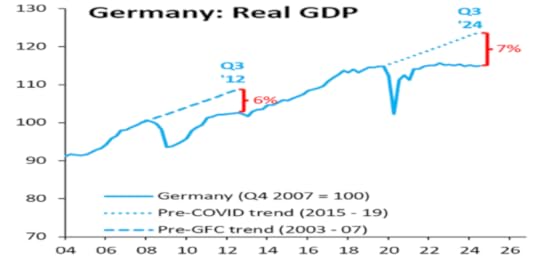

The new government faces a major challenge because Germany’s economy is tanking. The economy shrank in 2023 and again in 2024; it seems likely to stay in recession again this year. It adds up to the longest period of economic stagnation since the fall of Hitler in 1945.

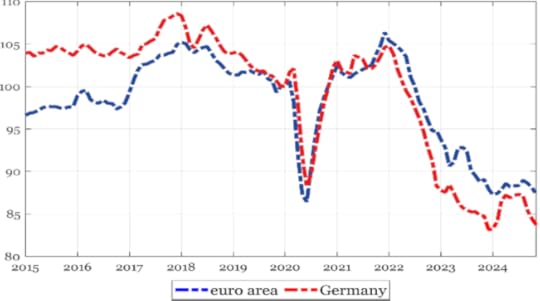

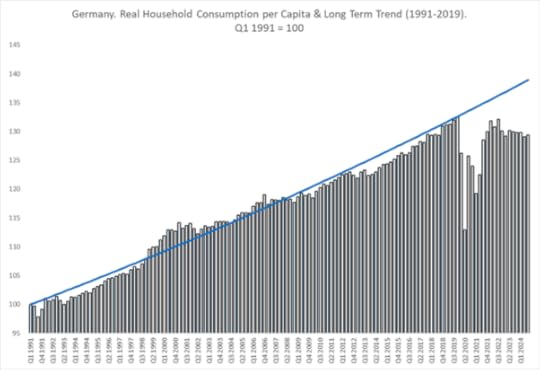

The great manufacturing powerhouse of Europe, Germany, has ground to a halt since the pandemic. German real GDP has stagnated for the last five years. Real business investment in Germany is severely depressed, more so than in the Eurozone overall. Real household consumption in Germany has been hammered.

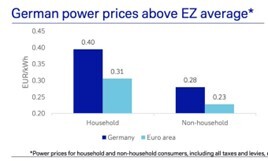

The German government has followed slavishly the policies of the Western NATO alliance and ended its reliance on cheap energy from Russia – it even went along with the blowing-up of the vital Nordstream gas pipeline. As a result, energy costs have rocketed for German households.

But more important for German capital are the rising energy costs for manufacturers. The power has gone out of the economy. Cheap fossil fuel imported from Russia has gone as part of the sanctions and the break with Russia over the Ukraine war. It has been replaced by expensive LNG from America, so that electricity costs have rocketed. The German Chamber of Industry and Commerce (DIHK) commented: “The high energy prices also affect companies’ investment activities and thus their ability to innovate. More than a third of industrial companies say that they are currently able to invest less in core operational processes due to the high energy prices.”

Energy intensive sector production (indexed)

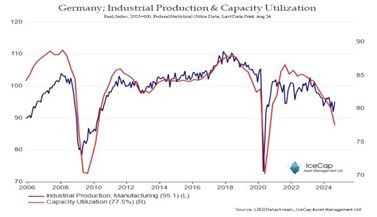

Achim Dercks (DIHK). “If companies themselves no longer invest in their core processes, this will amount to a gradual dismantling.” As a result, manufacturing output and capacity has plummeted.

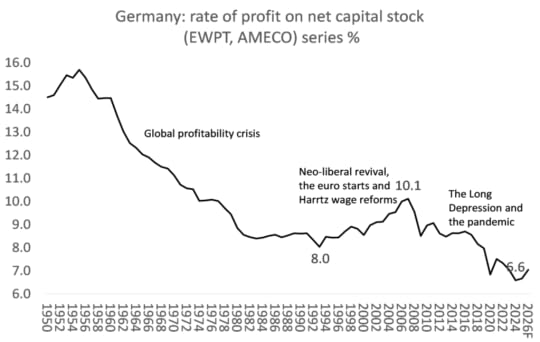

The profitability revival for German capital from the beginning of the euro and the relocation of industrial capacity into the east of the EU and low wages for a large part of the labour force is over. Profitability began to fall in the Great Recession and through the Long Depression of the 2010s. The biggest drop came in the pandemic and profitability is now at an historic low.

Worse, the mass of profits has also started to fall as the rising costs of production (energy, transport, components) eat into revenues. Real gross capital formation (a proxy for investment) is contracting.

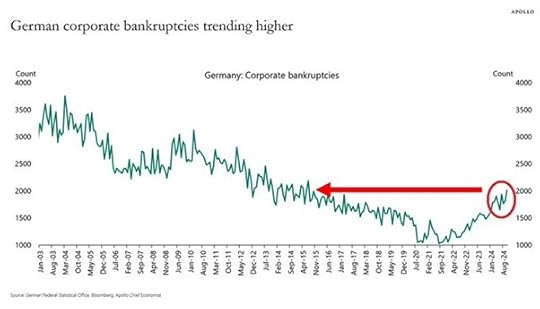

German corporate bankruptcies have jumped 2,000, the highest in ten years. That’s a doubling in the last three years reaching 4215 at the end of 2024.

Real wages in Germany remain below pre-pandemic levels. A quarter of Germans have incomes that are insufficient to make ends meet, according to the German Economic Institute in its”Distribution Report 2024″ citing household survey data.

No wonder consumer spending has fallen off a cliff.

It’s just a matter of months until the number of unemployed people in Germany hits 3 million for the first time in a decade, as companies either go bankrupt or give up waiting for a turnaround that just refuses to arrive. After a wave of plant closures in energy-intensive industries such as chemicals in 2022, the key automotive sector succumbed last year, with Volkswagen and others announcing thousands of job cuts. The jobless rate is now at its highest level in more than four years, only just below where it peaked during the pandemic. Klaus Wohlrabe, Ifo’s head of surveys, said he expects the jobless rolls to hit the 3-million mark by the middle of the year.

The demise of the German economy has exposed the underlying issue of a ‘dual labour’ market with a whole layer of part-time temporary employees for German businesses on very low wages. About one-quarter of the German workforce now receive a ‘low income’ wage, using a common definition of one that is less than two-thirds of the median, which is a higher proportion than in all 17 European countries, except Lithuania. This cheap labour, concentrated in the eastern part of Germany, is in direct competition with the huge numbers of refugees arriving in the last two years. So many voters in eastern Germany think that their problems are due to immigration, providing traction for the AfD. But while immigration does come out on top in voters’ most important issues, the economic situation, energy, and inflation also get a combined 58%.

CDU leader Friedrich Merz’s solution to this crisis are the usual neo-liberal policies: reductions in government spending (benefit cuts) and ending business ‘red tape’. Under the SPD coalition there were heavy social spending cuts in order to pay for more military purchases, ‘Project Ukraine’ and rising energy costs. Ironically, Merz says there must still be room to raise defence spending – Merz even mooted that Germany should get nuclear weapons.

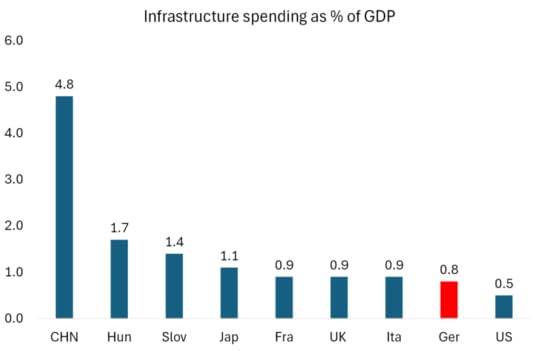

Merz promises that his government will right the ship by attracting more private investment in the economy. Meanwhile, Germany’s infrastructure spending on rail, bridges etc is at an all-time low. Germany’s reputation for efficiency no longer holds true, critics contend — trains do not run on time, internet and mobile phone coverage is often patchy, and roads and bridges are in a state of disrepair. Elsewhere there are concerns about the state of the country’s bridges — in a 2022 paper, the transport ministry identified 4,000 of them in need of modernisation. Just 11 percent of Germany’s fixed broadband connections are of the faster fiber-optic variety, one of the lowest rates among countries in the OECD.

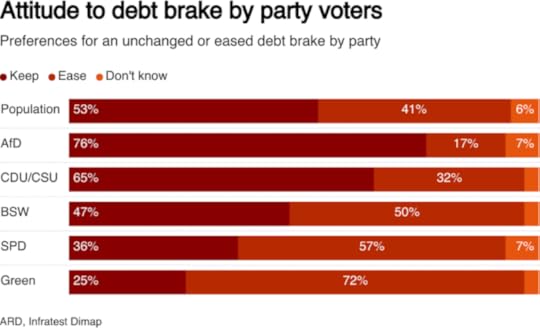

Germany’s failure to increase public sector investment is partly down to the so-called “debt brake”, a constitutional limit on government spending. Agreed in 2009, this requires that the country’s budget deficit does not exceed 0.35% of structural GDP. This rule has reduced the government’s ability to invest. However, the German constitutional court would most likely want to put a limit on any attempts to end the rule and so even if modifications to the debt brake do pass judicial review, they would likely be too small to materially expand Germany’s fiscal space. Moreover, two out of three CDU/CSU and three-quarters of AfD voters oppose any easing of the debt brake. Indeed, the SPD-led coalition fell precisely because the FDP finance minister refused to consider more borrowing and demanded tax and spending cuts.

The AfD claims the answer to Germany’s demise is to end immigration, leave the euro altogether and reduce its payments to the EU. The EU’s €115bn (£95.60) contributions to Ukrainian defence are only exceeded by the US’s €119bn. The BSW wants an end to support for Ukraine and an end to sanctions against Russia.

What all this shows is that even German capitalism, the most successful advanced capitalist economy in Europe, cannot escape the divisive forces of the Long Depression. But it also shows that the German coalition government’s slavish following of the interests of US imperialism in the name of ‘Western democracy’ over Ukraine and Israel has destroyed the hegemony of German capital in Europe and the living standards of its poorest citizens. No wonder the voices of nationalism and reaction have gained traction. The irony now is that the Trump administration seems intent on reaching a peace deal with Russia over the heads of European leaders.

German capitalism may have been a success story over the years since reunification with East Germany. But its long-term prospects do not look so good from hereon. It has a declining and aging workforce and fewer areas for exploitation of new labour outside Germany, while competition from China and Asia will mount. And Merz will have to get ready for Trump’s tariff increases on German exports to the US.

February 17, 2025

A whiff of stagflation

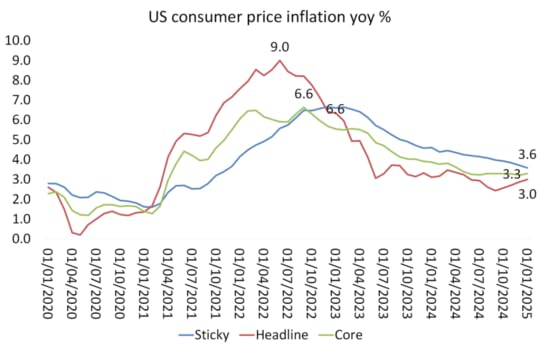

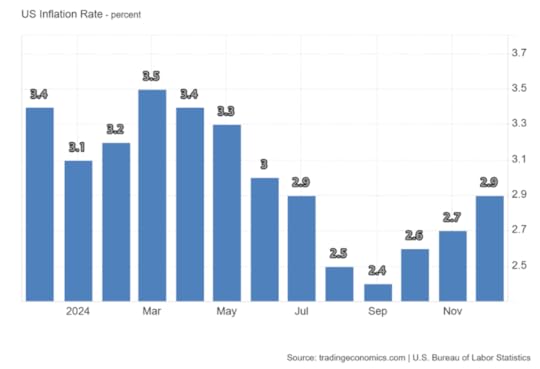

US consumer price inflation reached 3% year-on-year in January 2025. Energy prices rose for the first time in five months and food price inflation stood at its highest rate in a year. Food prices have leapt back up, as the cost of eggs rose 15.2%, the largest increase since June 2015, driven by an avian flu outbreak that caused a shortage of eggs; and cocoa and coffee prices have rocketed due to bad harvests in the global south, as global warming and climate change causes unpredictable and extreme weather events in growing areas.

So-called ‘core inflation’ (which excludes supposedly volatile food and energy prices) rose even more, to 3.3%, as insurance, rents and medical care costs continued to rise for American households. Used car prices rose sharply as Americans looked to find cheaper cars than expensive new electric vehicles. And mortgage rates remained at highs not seen since the 1980s. So as the headline inflation has fallen, the core rate has stayed higher.

Then there is the Sticky Price Consumer Price Index (CPI). This is calculated from a subset of goods and services included in the CPI that change price relatively infrequently. So they are thought to incorporate expectations about future inflation to a greater degree than prices that change on a more frequent basis. This measure has remained even higher.

What is clear is that US inflation is not moving any further towards the 2% a year target that the Federal Reserve has set for claiming that the ‘war against inflation’ is won. That’s why the Fed is holding on any further reductions in its policy interest rate, which sets the floor for all borrowing rates.

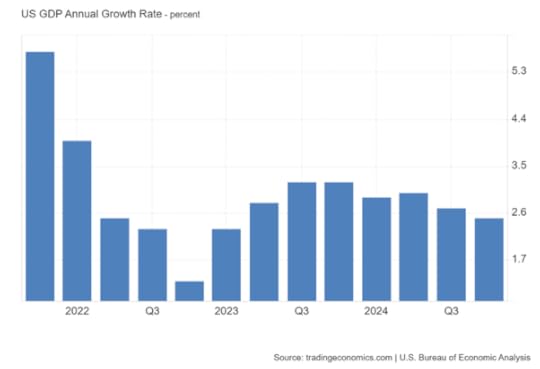

Unfortunately for the Fed, US economic growth is beginning to falter. The US economy expanded at an annualized 2.3% in Q4 2024, the slowest growth in three quarters, down from 3.1% in Q3. And the economic activity index for the US fell to its lowest level since last April. What was most worrying was the fall in business fixed investment, both in structures and equipment. Fixed investment contracted for the first time since Q1 2023 (-0.6% vs 2.1%), due to equipment (7.8% vs 10.8%) and structures (-1.1% vs -5%).

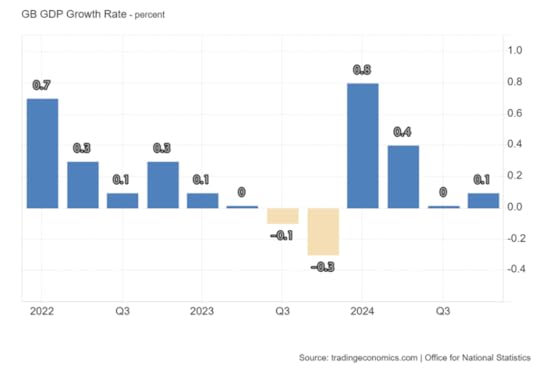

It was much worse in the UK, where, although the inflation rate dropped a touch to 2.5% a year in December, it is expected to have hit 2.8% yoy in January. Indeed, the Bank of England is now forecasting that inflation will rise to 3.7% yoy by year-end! The BoE will probably still cut its base rate again as it has no alternative but to try and help the UK’s very weak economy from continuing to stagnate. The BoE now predicts that the British economy will only grow by 0.75% this year, down from its previous forecast of 1.5% just three months ago.

As for the Eurozone, the annual inflation rate rose to 2.5% yoy in January, the highest rate since July 2024, driven primarily by a sharp acceleration in energy costs. The core rate stayed at 2.7% yoy. So EZ inflation is still above the ECB target and rising. Nevertheless, the ECB still hopes that its 2% a year target will be met by “the end of the year”.

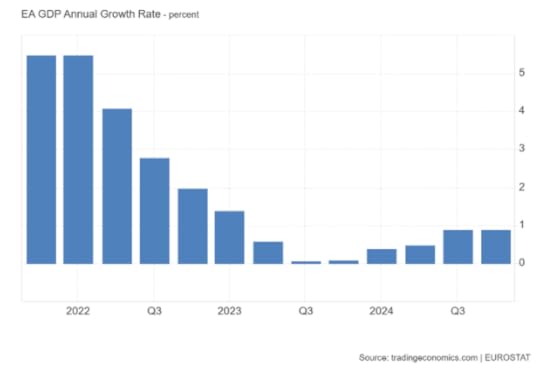

In the meantime, the Eurozone is stagnating ie little real GDP growth.

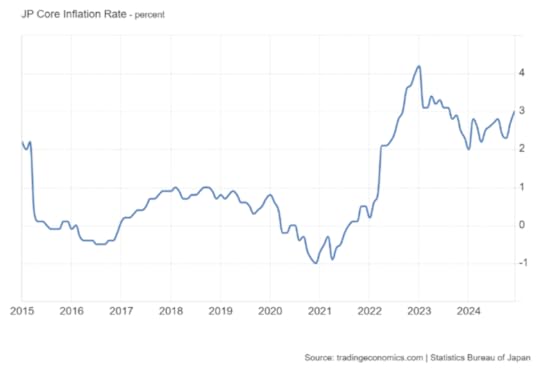

The annual inflation rate in Japan jumped to 3.6% in December 2024 from 2.9% in the prior month, marking the highest reading since January 2023. Food prices rose at the steepest pace in a year. The core rate also hit 3%, the highest rate since August 2023. Japan has been noted in the past for non-existent inflation. That’s all changed.

Japan’s monetary authorities have been trying to get inflation up on the grounds that this will boost economic growth (a weird theory). Yet Japan’s real GDP in 2024 was up only 0.1% compared to 1.9% in 2023, although the economy did pick up a little in the last quarter, driven mainly by exports.

So in the major economies, there is an increasing whiff of stagflation ie low or zero growth alongside rising price inflation. And this is before the inflationary and growth hit that could come if Trump implements his import tariffs and government spending cuts measures over this year.

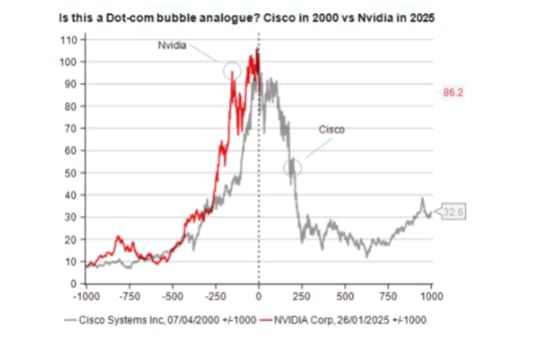

So far, financial investors in the US stock market seem unworried. Even the recent Deepseek launch that undermined the value of AI investments made by the US tech giants has been seen through. After an initial fall, the US stock market price index is again close to a new high. It seems that financial investors are not convinced that Trump will implement all his threats on tariffs and they like Musk’s trashing of government departments to get a ‘smaller state’. And they are confident that Trump will go through with more tax cuts on corporate profits and high-income earners.

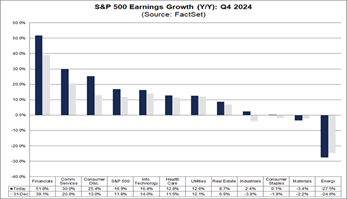

Most relevant is that corporate earnings are still growing. S&P 500 earnings growth for the fourth quarter of 2024 is estimated to have risen 15.1% from a year earlier, based on data compiled by LSEG. FactSet reckons that earnings growth could be even higher at 16.9%, the highest year-over-year earnings growth rate reported by the index since Q4 2021. It will also mark the sixth consecutive quarter of year-over-year earnings growth for the index.

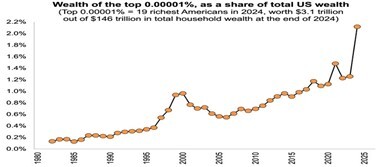

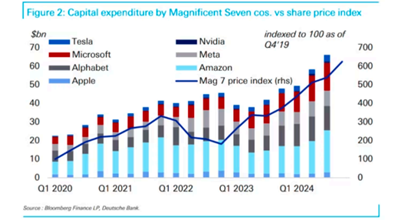

This earnings boom is driven by the banking sector which is making good profits from high interest rates and corporate borrowing deals. And of course, the other sectoral winner is communications, with the media tech giants accounting for about 75% of S&P 500 earnings growth in 2024. The so-called Magnificent Seven drive US stock market prices, and the US stock market drives world markets.

But earnings growth for these titans will likely fall back this year, given the huge spending on AI capacity that they have committed to. And most important, for the vast majority of US companies, those outside the burgeoning banking, social media and tech, things are not so great. S&P 500 free cash flow per share hasn’t grown at all in three years. Some 43% of the Russell 2000 companies are unprofitable. At the same time, interest expense as a % of total debt of these firms hit 7.1%, the highest since 2003. US corporate bankruptcies have hit their highest level since the aftermath of the global financial crisis as elevated interest rates punish struggling groups. At least 686 US companies filed for bankruptcy in 2024, up about 8 per cent from 2023 and higher than any year since the 828 filings in 2010, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

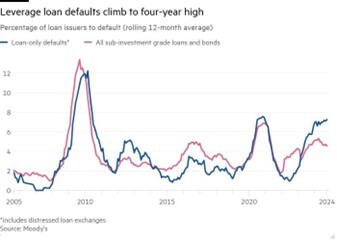

US companies are defaulting on junk loans at the fastest rate in four years, as they struggle to refinance a wave of cheap borrowing that followed the Covid pandemic. Because leveraged loans — high yield bank loans that have been sold on to other investors — have floating interest rates, many of those companies that took on debt when rates were ultra low during the pandemic and have since struggled under high borrowing costs in recent years.

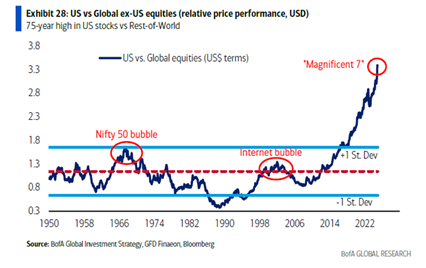

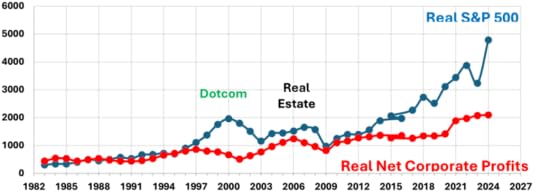

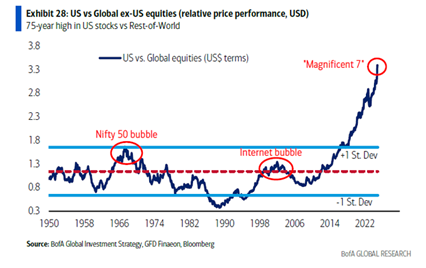

And when you strip out inflation from stock market prices and US corporate earnings, it reveals how far out of line the US stock market is compared to the real profits being made in the productive sectors of the US economy (that’s excluding financial profits). This is a graph compiled by Marxist economist, Lefteris Tsoulfidis.

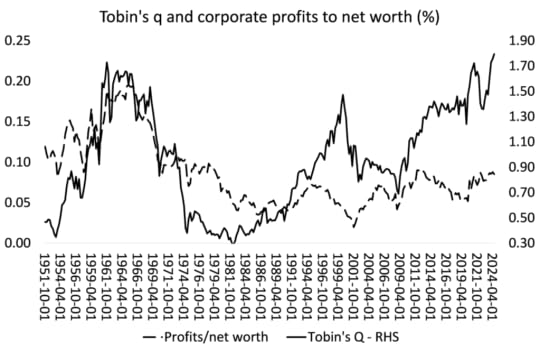

I have also compiled a similar measure to compare the stock market value compared to profits in the US corporate sector. Tobin’s Q is the ratio of stock market value divided by the book value (ie the value of their assets as recorded in the accounts of the companies quoted on the stock market). Then I have measured corporate profits relative to the net worth of company assets. Tobin’s Q is at a record high ie the stock market value is way out of line with corporate assets. And corporate profits relative to company assets are relatively low.

To repeat what Ruchir Sharma, chair of Rockefeller International, said recently. He called the US stock market boom “the mother of all bubbles”. Let me quote: “Talk of bubbles in tech or AI, or in investment strategies focused on growth and momentum, obscures the mother of all bubbles in US markets. Thoroughly dominating the mind space of global investors, America is over-owned, overvalued and overhyped to a degree never seen before. As with all bubbles, it is hard to know when this one will deflate, or what will trigger its decline.”

The major economies are exhibiting signs of stagflation. That means interest rates could stay high, while economic growth goes missing. That is a recipe for an eventual crash in financial markets.

February 11, 2025

What’s up with capitalism?

In an important new development, the University of Tulsa, Oklahoma has launched a new Center for Heterodox Economics (CHE). Led by Clara Mattei as Director of the Center for Heterodox Economics, its mission statement says: “The CHE has the ambitious goal of becoming a hub for achieving economic justice and a more humane society. We aim to organically combine the expertise of lived experience and the expertise of academic rigor. To counter dominant narratives, the CHE seeks to provide sturdy theoretical tools that empower and sharpen common sense. Our Center endeavors to train young scholars in the broad tradition of heterodox economics, encouraging them to learn from real life problems and engage in the world around them.”

To launch the new center, the CHE held an inaugural conference last weekend in Tulsa with the theme: ‘what’s up with capitalism?’ Many well-known radical economists participated. The sessions were livestreamed, so I was able to follow some of the discussions. But I did not follow all the sessions and missed the contributions of many, so I shall just concentrate on some presentations.

I missed the first session (online) but I noted that James Galbraith was one of the speakers. Galbraith, son of the well-known JK Galbraith, one of the most important leftist American economists of the 20th century, has always been a strong critic of neoclassical general equilibrium economics, the school that dominates mainstream economics in the universities and public institutions.

James Galbraith with Jing Chen has a new book out, called Entropy Economics, which attacks general equilibrium economics from the angle of the laws of physics and biology, which is “an unequal world of unceasing change in which boundaries, plans, and regulations are essential.” As Galbraith says in an interview: “It’s not a complicated idea, but it’s fundamentally opposed to the notion that the world tends to a balance between the great forces of supply and demand, or however you want to characterize the textbook vision of things.” Instead, capitalism is really subject to entropy, namely a state of disorder, randomness or uncertainty.

The blurb for the book says that “Galbraith and Chen’s theory of value is based on scarcity, and it accounts for the power of monopoly.” That signals to me that Galbraith does not support Marx’s value theory which argues all value comes from human labour power; and capital through the ownership of the means of production can appropriate surplus value from the exploitation of labour. Galbraith instead looks to ‘imperfect competition’ and ‘monopoly’ and ‘imbalances’ in supply and demand in a market economy as the cause of capitalism’s ‘entropy’. This sums up the difference between the Marxist economic analysis of capitalism and ‘heterodox’ theory, both of which are included by CHE in its courses.

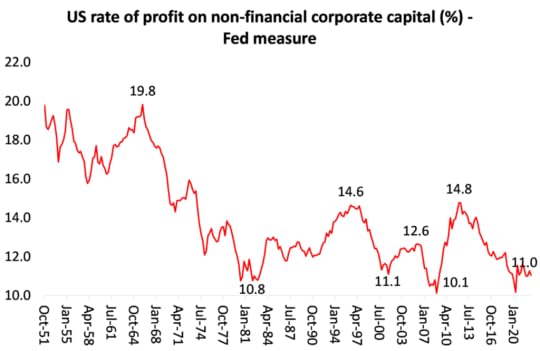

In the session on Marx, there was a surprising (to me) presentation by Deepankar Basu, Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Basu and his colleagues have done important work on measuring the profitability of capital. In particular, they have set up a fantastic interactive database that measures the rate of profit in many countries and globally.

Marx’s law of profitability argues that a rising organic composition of capital (ie capital stock C divided by the value of labour power v) will lead to a fall in the rate of profit, if the rate of surplus value (ie profit divided by wages) is constant or does not rise as much. You can see this from the formula: s/(C+v). If C/v rises and s/v is constant or rises less than C/v, then the rate of profit must fall. But in his presentation, Professor Basu appeared to support the thesis presented in the 1960s by the Japanese Marxist Nobuo Okshio, who argued that Marx was wrong because no capitalist would invest in new machinery (C) unless it raised profitability. The only way profitability would fall is if wages rose to squeeze profits.

Now the Okishio thesis has been refuted by many Marxist scholars since and even Okishio drew back from it later. I won’t go into the arguments against Okishio here, but what was interesting is that Professor Basu sought to prove Okishio right empirically. With the help of a graduate student, he presented evidence to show that if capitalists invest in new technology that increases the productivity of labour, profitability will only fall if the wage share or wage bill rises. If the wage share falls, then profitability will rise.

If true, this does away with Marx’s general law of accumulation (namely a rising organic composition of capital over time) as being the driver of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Instead, the causes of falling profitability revolve around the changes in the share of profits and wages in production. This was originally the theory of David Ricardo in the early 19th century to explain falling profits (ie it was due to rising wages). That’s why in the modern era, this profit share theory has been called ‘neo-Ricardian’.