Michael Roberts's Blog, page 34

November 4, 2021

Poverty in the pandemic

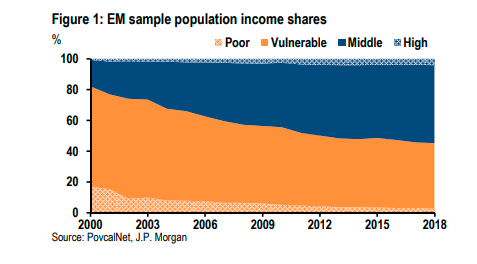

The COVID19 pandemic slump has raised poverty across the globe. JP Morgan economists have tried to measure the increase in poverty using household income and consumption survey data from the World Bank’s PovcalNet database. JPM define the poor (or those in deep poverty) as living on less than $2 per day (which is the ludicrously low World Bank level); ‘those vulnerable to slipping into poverty’ as living on $2-$10 per day (which is really a better measure of poverty); ‘middle income’ are those living on $10-50 a day (some leeway for a life); and then ‘high-income’ as living on more than $50 per day or about $18,000 a year.

Before COVID, about half of the 6.5bn people living in the so-called ‘emerging markets’ could be considered ‘middle income’. That means that at least 3bn are in dire poverty (‘economically vulnerable’ or worse).

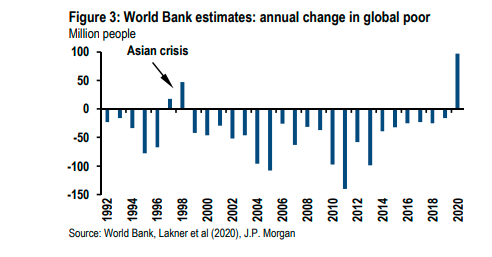

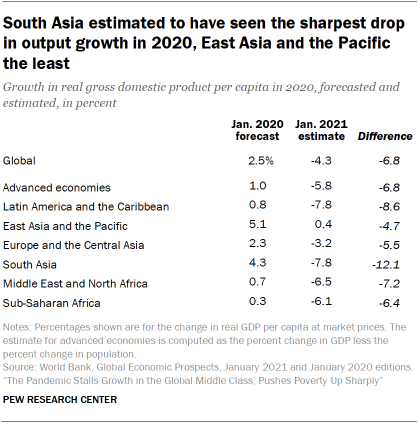

Using these definitions, JPM finds that, during the COVID slump, there was a sharp increase in global poverty. Using the World Bank data, the number in poverty (defined as living on less than US$1.90 per day) increased by 97 million in 2020—the first net increase in global poverty since the Asian Financial Crisis (Figure 3). A separate Pew Research Center study finds that the pandemic pushed 131 million people into poverty. And these poor are not rural peasants, but urban and often educated.

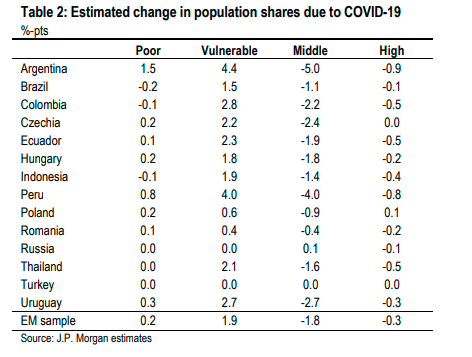

The increase in the poor and the corresponding fall in the ‘middle income’ population varied from country to country. Economies with the deepest contractions in 2020 (such as Peru and Argentina) experienced the greatest declines in the ‘middle income’ group. Overall, it was the ‘vulnerable’ that grew the most (1.9% pts) as a share of the population while middle income share was reduced the most (-1.8% pts).

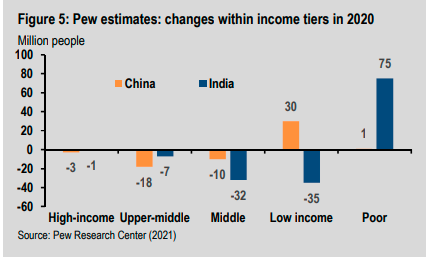

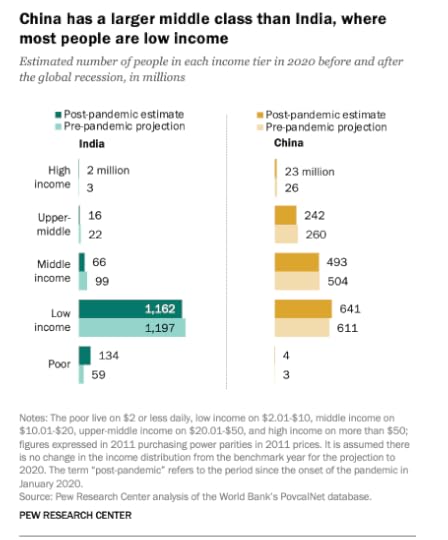

Some countries avoided the worst. China’s ‘first-in-first-out’ COVID-19 experience did not entirely shield the country from a contraction of the upper and middle classes, but there was only a small expansion of the poorest population, according to Pew estimates.

Before the pandemic, Pew estimated that almost 100 million people made up India’s middle-income population in 2020, with a further 22 million in the upper-middle ranks. But the pandemic hit India hard with real GDP contracting 7% in 2020, so the middle and upper-middle populations suffered dramatically (jointly declining by 39 million people—Figure 5). Meanwhile a staggering 75 million people were estimated to have fallen into poverty—accounting for almost 60% of the new global poor. Such was the contrast between the world’s two largest populated countries.

In China, there had been a sizable addition of 247 million people to the middle-income tier from 2011 to 2019. And the upper-middle income population had nearly quadrupled, from 60 million to 234 million. On both fronts, China alone had accounted for the majority of the increase in these tiers globally. Most people in India were in the global low-income tier before the pandemic. – some 1.2 billion people accounting for 30% of the world’s low-income population.

In China, there are now more people in the global middle- and upper-middle income tiers than in poverty and the low-income tier. Although about 10 million people in China are estimated to have fallen out of the middle class in the pandemic downturn, this is a small share of the 504 million who were in the middle class ahead of the pandemic. Likewise, the expansion of the low-income tier in China from 611 million to 641 million or the number of poor from 3 million to 4 million during the pandemic is comparatively modest in number.

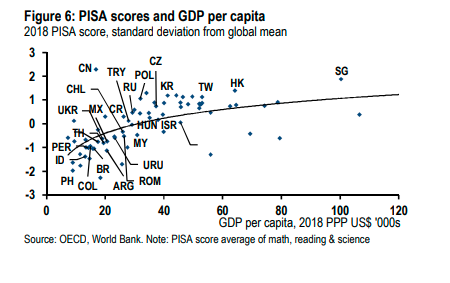

As people fall into deep poverty, they have no funds to support their education and keep them healthy. And that means, apart from suffering other obvious consequences, their productivity falls, damaging the economy as a whole. In Figure 6 we find that China’s investment in education and health per person (PISA score) is high at over 2 standard deviations from the global average and better than any other ‘emerging’ country (even those with higher per capita incomes like Singapore or Korea).

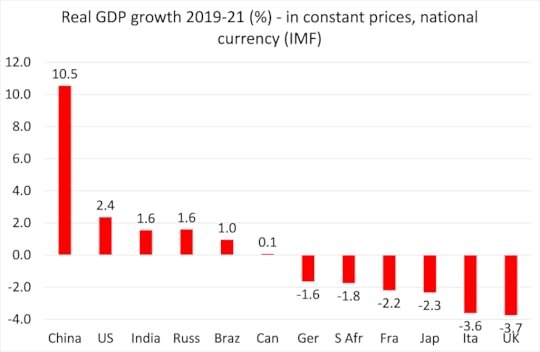

The pandemic has been a disaster for India’s people, driving millions into deep poverty, while the Chinese people have mostly avoided a dip into poverty. Indeed, the Chinese economy has expanded the most among the major economies in the two years since end-2019 and the start of the pandemic – more than four times the expansion in the US and six times that of India. Indeed, most major economies contracted.

October 30, 2021

Japan general election: the ‘new capitalism’

There is one G7 leader who won’t be at the Glasgow COP26 or G20 meeting in Rome this weekend. That is Japan’s new prime minister Fumio Kishida, who, after replacing the unpopular Yoshihide Suga as leader of the ruling Liberal Democrat party, has called a snap general election.

Kishida is putting at serious risk the majority for his party in the election. The LDP has lost support through its handling of the COVID crisis and because of the failure of the economy to make any significant recovery from the pandemic slump in 2020. Opinion polls suggest that the LDP’s representation could be reduced from 275 seats in the previous parliament to just 233 seats this time. The LDP would lose its outright majority and be forced into a coalition with its tame junior coalition party Komeito to sustain power.

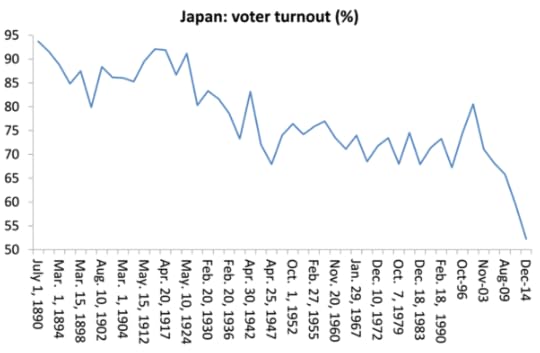

Voter turnout will be crucial. Higher turnouts tend to help the opposition parties, who have united tactically to reduce the LDP majority. But the disillusionment with party politics in Japan, which I have reported on before, looks like continuing, especially among the young. The overall turnout could be as low as the post-war low of 52.7% in 2014 and lower than the 2017 turnout of 54%, with only one-third of 18-24 year-olds bothering to vote.

Kishida is a former banker, no surprise there, and claims that he is going to revive the Japanese economy with what he calls a “new capitalism”, which is supposedly a rejection of ‘neoliberalism’ as operated by previous PMs like Abe, with his ‘three arrows’, and aims to reduce inequality, help small businesses over the large and ‘level up’ society. This would break with Abe’s emphasis on ‘structural reform’ ie reducing pensions, welfare spending and deregulating the economy.

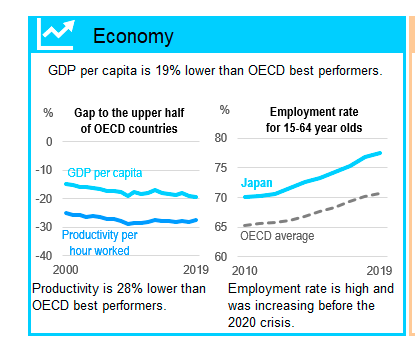

Japan remains over 30% less productive than the US and Kishida wants to cut ‘red tape’ and get more women and seniors into gainful employment, with efforts to raise social benefits for those in non-regular work up to the same level as Japan’s “salary men.” A new Public Price Evaluation Review Committee will aim to lift wages for carers and childcare staff, and Kishida has called for more support for schooling and housing costs for parents.

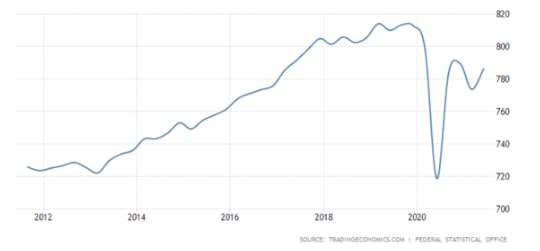

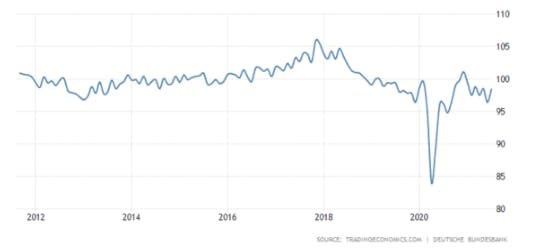

Action is certainly needed on the economy. After decades of slow real GDP growth (only compensated for by a falling population), the recovery from the pandemic slump (recording a 4.5% contraction) looks very weak. Japan has lagged behind other G7 economies.

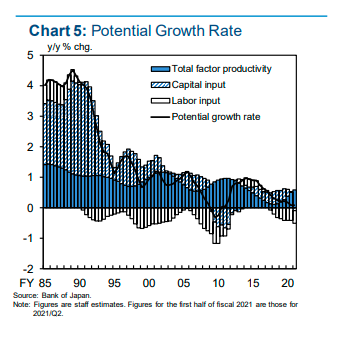

The overall economy has remained in recession until very recently. The au Jibun Bank Japan Composite PMI was up to 50.7 in October 2021 finally suggesting the first expansion in private sector activity in six months. Even so, GDP is projected to expand by only 2.6% in 2021 and 2% in 2022. Indeed, the BoJ reckons the long-term potential growth rate will be close to zero!

Business investment is expected to pick up as corporate profits improve (if still below pre-pandemic levels), but public sector investment is stagnant. Inflation is still running well below the Bank of Japan’s 2% target. Wage growth has been stagnant — total cash earnings were virtually no higher than they were a year earlier despite weakness last year.

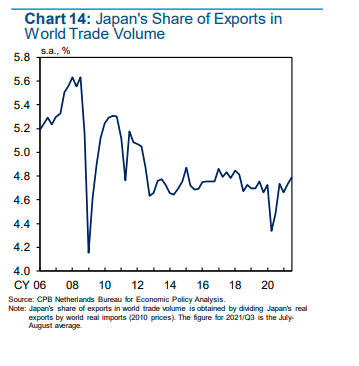

Japan was known as the major manufacturing economy of the 20th century but with the rise of China and rest of east Asia, Japan’s export share has fallen.

Japan is now putting its hopes on the new Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a Asian trade agreement including China that covers about 30% of the world’s population and output. The pandemic has delayed other countries’ ratification, which is a requirement for the multilateral agreement to become effective. Once it goes into effect, the RCEP could add $500 billion to global trade by 2030. The partnership is particularly important for Japan as it lowers tariffs for Japanese exports to China and South Korea, two of its three largest trading partners.

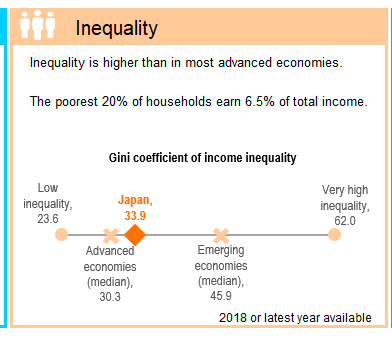

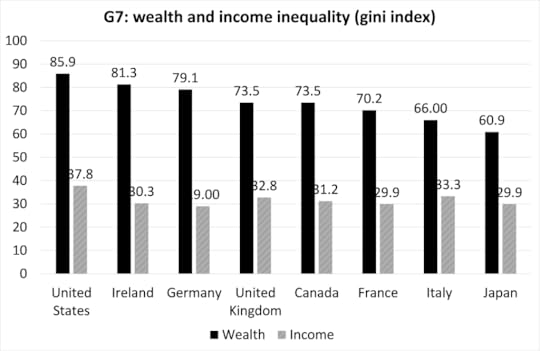

Kishida talks about reducing inequality and Japan’s inequality of income measures are higher than in most advanced capitalist economies.

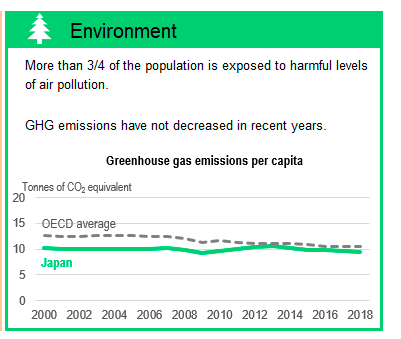

And when it comes to dealing with the environment, the LDP’s record is hardly successful.

After the failure of Abenomics in the decade after the Great Recession, Kishida has his work cut out to deliver his ‘new capitalism’ in the decade after the pandemic.

October 28, 2021

COP-out 26

This weekend, COP26 meets in Glasgow, Scotland. Every country in the world is supposed to be represented in meetings designed to achieve agreement on limiting and reducing greenhouse gas emissions so that the planet does not overheat and cause widespread damage to the environment, species and human livelihoods across the planet.

We are currently on track for at least a 2.7C hotter world by the end of the century – and that’s only if countries meet all the pledges that they have made. Currently they are nowhere near doing that. Governments are “seemingly light years away from reaching our climate action targets”, to quote UN chief Guterres.

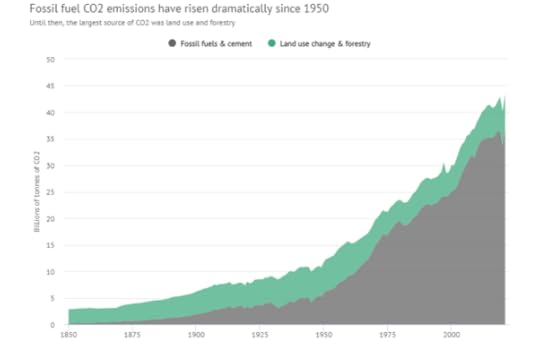

Global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions are on course to surge by 1.5 billion tonnes in 2021 – the second-largest increase in history – reversing most of last year’s decline caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Global emissions are expected to increase by 16%, not fall, by 2030 compared with 2010 levels.

COP stands for the Conference of the Parties to the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which set the stage for all international cooperation on climate. According to the UN, the top three priorities of the Glasgow COP26 are to: 1) keep the global temperature rise to no more than 1.5 degrees celsius through “rapid, bold emissions cuts” and net-zero commitments; 2) increase international finance for adaptation to at least half the total spent on climate action; 3) meet the existing commitment to provide $100 billion in international climate finance each year so that developing countries can invest in green technologies, and protect lives and livelihoods against worsening climate impacts. The reality is that even these modest priority targets are not going to be agreed in Glasgow and certainly not met in application, given the current make-up of governments and the plans of industry and finance around the world.

There is no longer any plausible scientific argument against the view that human human activities are having a profound effect on the climate. The dwindling band of ‘climate sceptics’ have been silenced (at least in the mainstream media) by the overwhelming and increasing evidence that fossil-fuel based industrial and energy production and transport is causing rising carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions and this is the the cause of global warming. Moreover, global warming since the industrial revolutions of the 19th century has now risen to the point where it is destroying the planet.

But what is not so understood is that this impending (and already beginning) disaster could still be averted and reversed and without a significant cost to governments. Indeed, the latest report from the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2021 shows that we know what to do about it, in substantial detail and at an affordable cost. But there is no political will to do so by governments, beholden are they to the fossil-fuel industry, to aviation and transport sectors and to the demands of finance and industrial capitalists as a whole to preserve profits at the expense of social need.

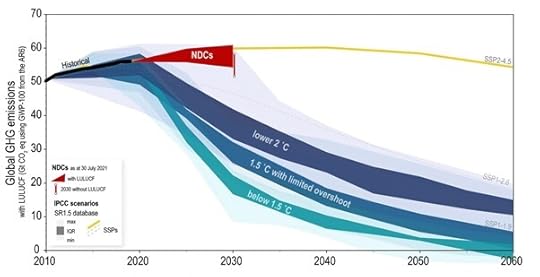

Already there is a yawning gap between government commitments to reduce emissions to be offered at COP26 and what is necessary. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that limiting global average temperature increases to 1.5C requires a reduction of CO2 emissions of 45% by 2030 or a 25% reduction by 2030 to limit warming to 2C. 113 governments have offered National Determined Contributions (NDCs), which will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by only 12% in 2030 compared to 2010.

The world’s governments plan to produce more than twice the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than would be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. Governments are collectively projecting an increase in global oil and gas production, and only a modest decrease in coal production, over the next two decades. This leads to future production levels far above those consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2°C. In 2030, governments’ production plans and projections would lead to around 240% more coal, 57% more oil, and 71% more gas than would be consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

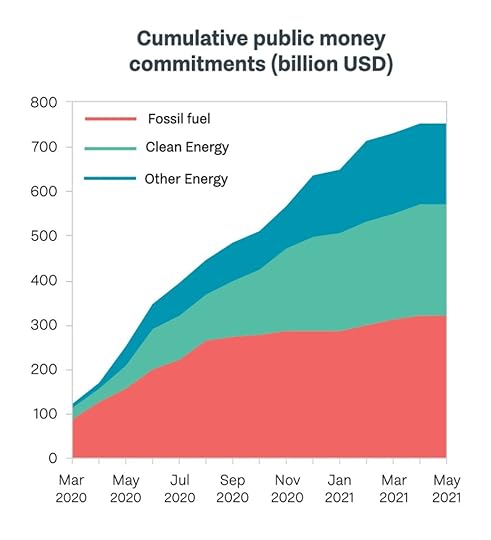

Indeed, G20 countries have directed around USD 300 billion in new funds towards fossil fuel activities since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic — more than they have toward clean energy. According to the International Energy Agency, only 2% of governments’ “build back better” recovery spending has been invested in clean energy, while at same time the production and burning of coal, oil and gas was subsidised by $5.9tn in 2020 alone.

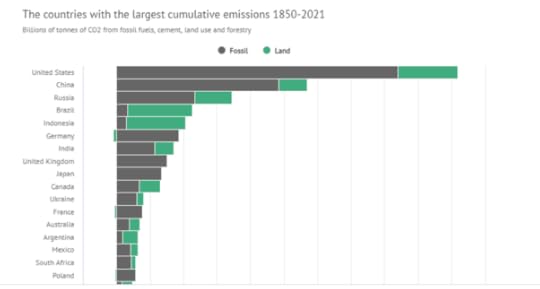

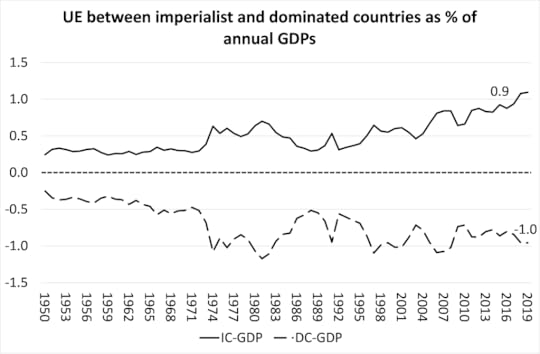

Which countries are to blame for this failure to do anything remotely close to avoiding the environmental disaster. China is usually picked out as the main culprit. It is currently by far the world’s biggest emitter of CO2 and is planning to build 43 new coal power plants on top of the 1,000 plants already in operation. But China has some excuses. It has the largest population in world and so its per capita emissions are much lower than most other major economies (although it’s the mass that counts). Second, it is the manufacturing centre of the world providing goods for all the rich countries of the Global North. As a result, its emissions are going to be huge because of the consumer demand for its products globally.

Moreover, historically, cumulative emissions built up in the atmosphere in the last 100 years come from the rich previously industrialised and now energy consuming North. There is a direct, linear relationship between the total amount of CO2 released by human activity and the level of warming at the Earth’s surface. Moreover, the timing of a tonne of CO2 being emitted has only a limited impact on the amount of warming it will ultimately cause. This means CO2 emissions from hundreds years ago continue to contribute to the heating of the planet – and current warming is determined by the cumulative total of CO2 emissions over time.

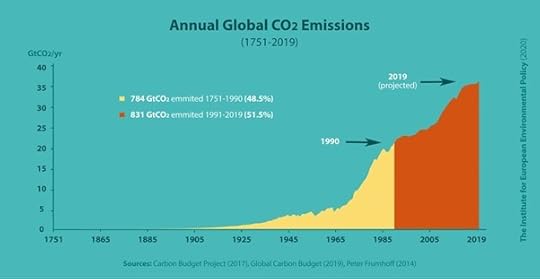

In total, humans have pumped around 2,500bn tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) into the atmosphere since 1850, leaving less than 500GtCO2 of remaining carbon budget to stay below 1.5C of warming. This means that, as the Glasgow COP26 takes place, the world will collectively have burned through 86% of the carbon budget for a 50-50 probability of staying below 1.5C, or 89% of the budget for a two-thirds likelihood. More than half of all CO2 emissions since 1751 were emitted in the last 30 years.

In first place on the historical rankings is the US, which has released more than 509GtCO2 since 1850 and is responsible for the largest share of historical emissions with some 20% of the global total. China is a relatively distant second, with 11%, followed by Russia (7%), Brazil (5%) and Indonesia (4%). The latter pair are among the top 10 largest historical emitters, due to CO2 from their land.

The biggest emitters or consumers of carbon apart from the fossil fuel industry are the richest wealth and income earners in the Global North who have excessive consumption and fly everywhere. It is the military (the biggest sector of carbon consumption). Then there is waste of capitalist production and consumption in autos, aircraft and airlines, shipping, chemicals, bottled water, processed foods, unnecessary pharmaceuticals and so on is directly linked to carbon emissions. Harmful industrial processes like industrial agriculture, industrial fishing, logging, mining and so on are also major global heaters, while the banking industry operates to underwrite and promote all this carbon emission.

And the US is really doing little to control or reduce the fossil fuel industry. On the contrary, crude oil and gas production is rising fast and exploration is being expanded. The Biden administration recently announced plans to open millions of acres for oil and gas that could ultimately result in production of up to 1.1bn barrels of crude oil and 4.4tn cubic feet of fossil gas. Being by far the biggest emitter in history, as well as the world’s number one oil producer, doesn’t seem to embarrass the US while it claims to be a climate leader.

Indeed, most major oil and gas producers are planning on increasing production out to 2030 or beyond, while several major coal producers are planning on continuing or increasing production.

No wonder the governments of the fossil fuel producers and consumers, like Saudi Arabia, Japan and Australia are among those countries asking the UN in Glasgow to play down the need to move rapidly away from fossil fuels; or for paying more to poorer states to move to greener technologies. China may be the world’s largest polluter but it is pledging to bring its emissions to a peak before 2030, and to make the country carbon neutral by 2060. And it is already a renewable energy leader, accounting for about 50% of the world’s growth in renewable energy capacity in 2020. The world’s most populous nation is also out in front on key green technologies such as electric vehicles, batteries and solar power.

Across 40 different areas spanning the power sector, heavy industry, agriculture, transportation, finance and technology, not one is changing quickly enough to avoid 1.5C in global heating beyond pre-industrial times, according to a report by the World Resources Institute.

And yet the cost of phasing out fossil fuel production and expanding renewables is not large. Decarbonizing the world economy is technically and financially feasible. It would require committing approximately 2.5 percent of global GDP per year to investment spending in areas designed to improve energy efficiency standards across the board (buildings, automobiles, transportation systems, industrial production processes) and to massively expand the availability of clean energy sources for zero emissions to be realized by 2050. The IEA reckons the annual cost has now risen to $4trn a year because of the failure to invest since the Paris COP five years ago. But even that cost is nothing compared to the loss of incomes, employment, lives and living conditions for millions ahead.

But it won’t happen because, to be really effective, the fossil fuel industry would have to be phased out and replaced by clean energy sources. Workers relying for their livelihoods on fossil fuel activity would have to be retrained and diverted into environmentally friendly industries and services. That requires significant public investment and planning on a global scale.

A global plan could steer investments into things society does need, like renewable energy, organic farming, public transportation, public water systems, ecological remediation, public health, quality schools and other currently unmet needs. And it could equalize development the world over by shifting resources out of useless and harmful production in the North and into developing the South, building basic infrastructure, sanitation systems, public schools, health care. At the same time, a global plan could aim to provide equivalent jobs for workers displaced by the retrenchment or closure of unnecessary or harmful industries.

All this would depend first on bringing the fossil fuel companies into public ownership and under democratic control of the people wherever there is fossil fuel production. The energy industry needs to be integrated into a global plan to reduce emissions and expand superior renewable energy technology. This means building renewable energy capacity of 10x the current utility base. That is only possible through planned public investment that transfers the jobs in fossil fuel companies to green technology and environmental companies.

None of this is on the agenda at COP26.

October 25, 2021

Stocks, profit margins and the economy

The US stock market went back to record highs last week. This was despite media talk that the recent rise in goods and services prices inflation in the major economies may continue for some time ahead. This led to further hints that not only would central bank injections of credit money (quantitative easing) be tapered back soon; but also central banks would soon start to hike their policy interest rates. The Bank of England chief economist, Huw Pill, a follower of the hard-line ‘orthodox’ German economist Otto Issing, emphasised that the central banks’ task was not to boost the economy but to control inflation. Financial markets took that to mean that the BoE would be hiking rates very soon – even at the next November meeting of the policy committee. As a result, bond yields (the rate of interest on government bonds purchased in the bond market) rose to levels not seen for some time.

A rise in the cost of borrowing should lead to a fall in stock market investment as most financial investors borrow to speculate. However, the US stock market seems impervious to the news on inflation and interest rates. Why is that?

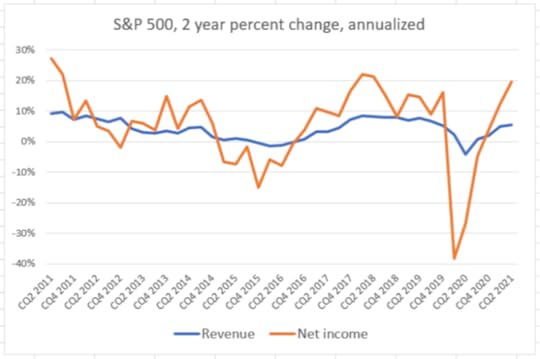

The reason seems to be that investors are still convinced that the global economy is recovering fast as the vaccines roll out and the fiscal stimulus plans of many governments, particularly the US, are to continue. As a result, forecasts of revenues and earnings being made by companies are very strong, with earnings rising at a 20% yoy pace.

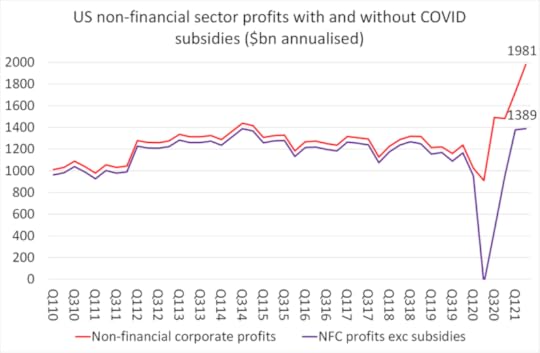

Indeed, if we look at profit margins ie profits per unit of output, then margins appear very high indeed, at around 14%, up sharply from the pre-pandemic. Corporations in the US and Europe have been registering huge profits this year that comfortably compensate for any reductions during the pandemic slump.

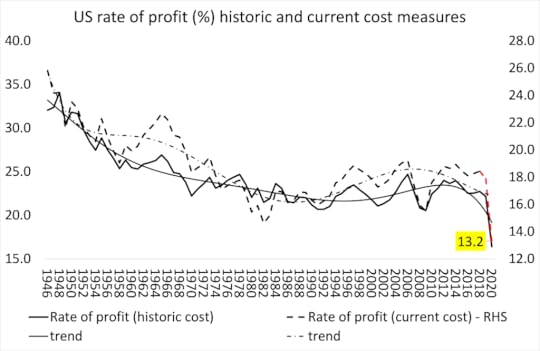

How does that square with the data which show that the profitability of capital in the US is near record lows?

Well first, both the stock market jump and the profits being recorded are heavily concentrated in the information technology sector and within that, the so-called FAANGS. This was something I and others pointed out before the pandemic struck in 2019. But it is even more so in 2021. The IT sector contributes 25% of all US non-financial corporate sector profits. And the other large contributor to profits is the consumer media sector, where Amazon dominates (50% of profits in the sector). So if you strip out these sectors from the stock market and the profits data, then the rest of the corporate sector is not doing so well, at all. Moreover, US corporate profits have been heavily subsidised in the last year from government handouts.

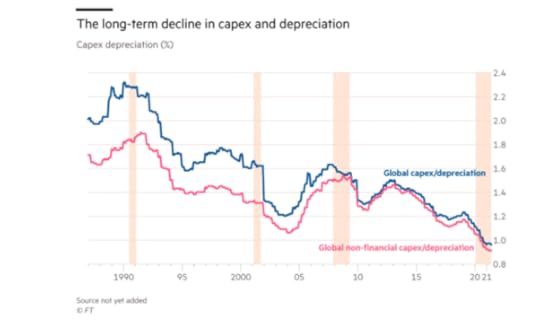

This explains the numerator in the measure of average profitability of capital in the US. Then there is the denominator. Profit margins measure profits against output. But profitability of capital measures profits against the cost of fixed assets (plant, machinery, technology) and the wage bill. And investment in fixed assets has been weak, in the sense of delivering productivity-increasing technology outside the tech sector itself. Vast swathes of industry and services in the US, Europe and Japan are barely making enough profits to cover the depreciation of existing assets and the cost of debt incurred. Investment (capex) relative to depreciation, which measures investment in new technology, has been declining over the long term, and especially in the pandemic slump, with little sign of recovery in 2021.

So while the tech sector holds up the stock markets and gives the impression of a widespread leap forward in profits, the rest of the capitalist economy is in the doldrums and has been throughout the ‘long depression’ of the 2010s. While the ‘old economy’ only represents about 35% of global gross domestic product, it generated at least twice the amount of corporate losses; and had about 90% of non-financial debt.

What is noticeable when we get to the so-called ‘real economy’ and away from the fantasy world of the stock and bond markets (the markets for what Marx called ‘fictitious capital’) is that the recovery from the pandemic slump of 2020 is beginning to falter.

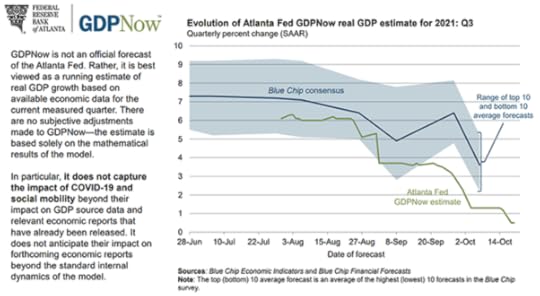

The Atlanta Fed GDP Now forecast model tracks the data coming out of the US economy and then makes a forecast for real GDP growth. As of 19 October, the model forecast that the US economy grew by only 0.5% (on annualised basis) in the third quarter of 2021 that ended in September.

Now this is well below the consensus forecasts which are more like a 3-4% pace. But even the consensus reckons the US economic recovery slowed sharply in the third quarter. We shall get official preliminary estimates this week. JP Morgan economists have noted the slowdown in Chinese growth, caused by continued COVID issues, weak growth in Asia, lack of raw materials and the impending residential property crisis. And they now forecast just 3% growth in the US in Q3. But they expect continued robust expansion in Europe, so that global growth was likely around 3.4% in Q3.

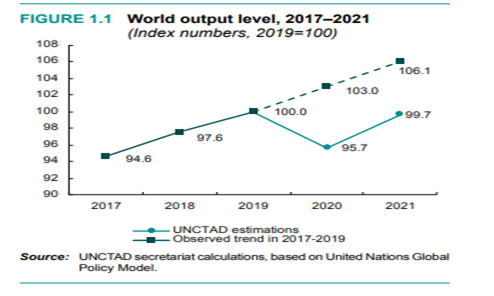

However, JPM reports that “this outcome would represent a substantial step back in the speed of the recovery. Relative to our forecast at the start of last quarter, the 3Q21 global GDP shortfall from its pre-pandemic pace has deepened by over a percentage point and now points to a 2.7% journey back to a complete recovery”. Indeed, by the end of 2022, JPM still expects world GDP to be below the pre-pandemic level – and well below where world GDP would have been without a pandemic slump. The recovery is not V-shaped but a reverse square root – see my 2021 forecast back in January.

The fantasy world of rising stock market prices can continue further, but the market is based on foundations of shifting sand. Sure, profit margins in the tech sectors in the major economies are still strong but outside of that sector, margins are tight. With inflation rising, central banks are increasingly having to consider ‘normalising’ monetary policy and hiking rates. If that happens, then the costs of debt servicing will rise. And if the shortage of labour in key sectors continues, then wages could also move up. Profit margins will then contract and the great stock market pandemic rally will reverse in 2022.

October 19, 2021

Shutdown

Adam Tooze has a new book out, Shutdown. Tooze is the liberal left’s current favourite historian. His previous book, The Wages of Destruction, won the Wolfson Prize for History and the Longman-History Today Book of the Year Prize. He has taught at Cambridge and Yale and is now Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Professor of History at Columbia University. He is a prolific writer of articles in the elite press; a mine of information and data on his Twitter account and his Chartbook site. And of course, he is on SubStack.

I reviewed his last best-selling book, Crashed. After singing the praises of Tooze’s account of the global financial crash and the ensuing Great Recession, I made the point that “Crashed provides us with the most granular and fascinating account of the crash and its aftermath. It powerfully shows what happened and how, but in my view does not adequately show why it happened. But maybe that is not the job of economic history, but that of political economy.”

There are two critiques there. The first is Tooze’s historical method: he decries ‘historicism’ as such and aims to provide a history of ‘the moment’, as it happens. That can offer an excellent survey of who does what and when, but it does not serve well to understand why. And second, although Tooze is an historian of events ‘as they happen’ (or immediately after), this approach has a false ‘neutrality’ in its analysis. For Tooze is not ‘neutral’ or ‘objective’ at all – and after all, nobody can be where social interests and viewpoints are often contradictory.

So beneath the ‘history of the moment’ lies an analysis of events that is really based on what Tooze calls ‘liberal democratic’ ideals, politically and on Keynesian theory and policy, economically. Tooze sees himself as offering a viewpoint “of a left-liberal historian whose personal loyalties are divided among England, Germany, the “island of Manhattan” and the EU.” (Tooze, ‘Tempestuous Seasons’, London Review of Books, 13 September 2018, p. 20.) Also: “the political intellectual tradition, which I personally feel attached to, which is left liberalism of the British variety.” And more:“I’m a confirmed liberal Keynesian in my broad politics, and my understanding of politics and the way expertise ought to relate to it, and the operations of modern democracy.”

On the whole, Tooze sees, for all her faults, that the US is on the side of the angels along with Western Europe, in defending the ideals of ‘democracy’ against the forces of authoritarian rule from the likes of Russia, China, Turkey etc. Perry Anderson points out that Tooze’s book, Wages of Destruction argues that Hitler saw America as the main enemy of Nazi Germany ie the US was the force for democracy against fascism. And yet all the evidence suggests that Hitler’s main ambition was to crush the Jewish Bolshevik conspiracy and, from the start, looked to invade and defeat Stalin’s Russia.

When it comes to the economics, in Crashed, we are asked to accept that, even though the actions of the US administration and the EU were full of holes, in the end they delivered in shoring up the system and avoiding a meltdown into a deep depression. Yes, the draconian measures imposed by the Troika on Greece were terrible, but Tooze says nothing about Syriza’s capitulation to the Troika. For him, there was no alternative but to ensure the survival of the EU as part of the liberal democratic order. As he wrote: “Left-wing hostility to the pro-market character of the EU and nationalist hostility to Brussels’ united to deliver a profound shock to Europe’s elite. ‘Whatever the rights and wrongs of the constitution, popular democracy had asserted itself’. Really? Have the ECB and the EU Council mended their ways?

In Shutdown, Tooze examines the unprecedented decision of governments around the world to shutter their economies in the face of pandemic. “The virus was the trigger,” writes the author. But other elements were at play, including a serious slowing of global economic growth, a rise in nationalist and authoritarian regimes around the world, and what, in effect, was a new cold war with China. In other words, the agents for destabilization were myriad well before Covid-19 arrived. Tooze calls this ‘polycrisis’, to describe this multipronged series of failures of imagination and governance.

Tooze moves fluidly from the impact of currency fluctuations to the decimation of institutions–such as health-care systems, schools, and social services–in the name of efficiency. And he shows how no unilateral declaration of ‘independence” or isolation can extricate any modern country from the global web of travel, goods, services, and finance. No country is an island when it comes to a virus, trade and supply chains – as we currently see.

The crux of Tooze’s message is that at the onset of the Covid-19 crisis, governments found themselves ‘flying blind’: none of the economic and political theories that purported to be guides for public policy proved to be of any use and were rapidly abandoned. Instead, driven by the need to “do something”, and be seen to “do something”, governments innovated.

Tooze recounts what public figures said in the very early stages of the pandemic. On February 3rd 2020, Boris Johnson, Britain’s prime minister, warned of the danger that “new diseases such as coronavirus will trigger a panic”, leading to measures that “go beyond what is medically rational, to the point of doing real and unnecessary economic damage”. Within two months, he had locked down the British economy. On February 25th 2020, Larry Kudlow, an adviser to President Donald Trump, said that “we have contained this”, cheerfully adding: “I don’t think it’s going to be an economic tragedy at all.”

Tooze confirms what this blog and other analyses both from health and economics have shown: that decisive government action, such as lockdowns and prudent and socially responsible behaviour by citizens, reduced mortality and economic damage, the behavioural balance between these being roughly one-third governmental and two-thirds at the level of citizens.

The politicians may have been disastrous, but the institutions of the liberal democratic order compensated. Whereas the financial crisis of 2008 showed the weakness of the world banking system, Tooze writes, the shock of the pandemic spoke to the weakness of asset markets as a whole, requiring entities such as the US Treasury to assemble “a patchwork of interventions that effectively backstopped a large part of the private credit system.” Apparently it helped that Steven Mnuchin, “the least ‘Trumpy’ of the Trump loyalists,” led those Treasury efforts. It is strange that Tooze has a good word for this hedge fund multi-millionaire, who said in April 2020: “This is a short-term issue. It may be a couple of months, but we’re going to get through this, and the economy will be stronger than ever,”

Tooze also has kind words for the central bankers. They were quick to grasp the implications of the disease. “In 2008 there had still been a note of hesitancy about central-bank interventions. In 2020 that was gone,” he writes. “Governments ended up backing this monetary stimulus with fiscal policy. The $14trn-worth of support they had provided by the end of 2020 was much larger than the stimulus they had offered in the wake of the global financial crisis.”

The business community also responded to the central bankers by apparently rejecting the policies of austerity. So when Joe Biden assumed the presidency, he pushed for big-dollar measures, which corporations supported, to jump-start the economy —with the proviso, Tooze notes, that Biden dropped his push for a $15 minimum wage.

It is an odd conclusion to reach about the policy response to the pandemic. Did central banks act to save people’s jobs or to shore up financial markets just as in 2008?; will the supposed fiscal largesse introduced in the 2020 slump be sustained in the rest of this decade?: are austerity policies really over? In the UK, the current Chancellor has already cut back subsidies to workers and businesses and is preparing regressive new taxes to fund government spending. In the US, Biden’s supposedly large infrastructure programme has been cut back by Congress and anyway will be financed by significant tax rises over the next five years. Keynesianism is not really making a comeback.

Yet Tooze’s instant history goes through the prism of Keynesian theory. Tooze is explicit about this. In a review of Geoff Mann’s excellent demolition of Keynesianism, In the Long Run We Are All Dead: Keynesianism, Political Economy and Revolution (2017), Tooze defines the distinctive virtue of Keynes’s outlook as a “situational and tactical awareness’ of the problems for liberal democracy inherent in the operations of the business cycle in a capitalist economy, requiring pragmatic crisis management in the form of punctual adjustments without illusion of permanency.”

He even argues that China’s huge state-led investment during the Great Recession, amounting to over 19% of China’s GDP, was an example of Keynesian policies in action and commands Tooze’s unstinting admiration. “This was the largest Keynesian operation in history, a mobilization of resources on a scale that Western economies had only ever achieved under the pressure of war. Its global impact was decisive. ‘In 2009, for the first time in the modern era, it was the movement of the Chinese economy that carried the entire world economy”.

I have argued elsewhere that this claim for Keynes is not supported by the evidence: China’s state investment, run and operated by state banks and state enterprises, bears no relation to Keynesian macro policies. Moreover, China’s avoidance of a slump did not ‘save capitalism’ in 2008-9; the Great Recession remained the widest and deepest slump in capitalism since the 1930s – until the pandemic slump of 2020.

In Crashed, the global financial crash was the result of the deregulation of the banking system, financial greed and incompetent authorities. For me, all these were just symptoms or immediate catalysts of the underlying causes in the capitalist economy. In Shutdown, we are again offered same Keynesian solutions to the pandemic slump: fiscal and monetary largesse.

As Tooze says in an interview with Tyler Cowan, the neoclasscial mainstream economist, “Keynesianism, classically, of course, is a liberal economic politics. It believes in a multiplier, and the multiplier’s the be-all and end-all really of Keynesian economics because what it suggests is that small, intermittent, discretionary interventions by the state — relatively small — will generate outside reactions from the economy, which will enable the state to serve a very positive role in stabilizing the economy but doesn’t require the state to permanently intrude and take over the economy”.

Thus, there is nothing in Shutdown about needing to end the failure of markets in the pandemic. The banks and the tech and social media giants that have made trillions out of the pandemic slump are to remain as they are, while hundreds of millions globally have been driven into poverty. It is not part of Tooze’s instant history agenda to “take over the economy”.

October 11, 2021

Stagflation: a demand or supply side story?

The semi-annual meetings of the IMF and World Bank start today where finance ministers and central bankers will meet in a slimmed-down but in-person gatherings in Washington. This meeting is likely to be overshadowed by the scandal involving the IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva, who may well have been forced to resign as I write after a devastating report on the machinations of senior World Bank officials several years ago. Georgieva has been accused of manipulating data on ‘Doing Business’ to favour China, Saudi Arabia and other states while she was at the World Bank several years ago. The scandal has divided IMF members, with the US pushing for her to go and European powers wanting her to stay.

But more important than even whether we can ever rely on the scientific honesty of the World Bank and the IMF is what is happening to the world economy as these international agencies meet to review progress on the recovery from the pandemic slump in 2020.

Earlier in the year, most mainstream forecasts for growth, employment, investment and inflation were bullish, with hopes for a V-shaped recovery based on the COVID vaccination rollout, the ebbing of the virus cases and the boost to many economies from fiscal spending by governments and injections of credit by central banks. But in recent months, that unabashed optimism has begun to fade. Just before IMF-World Bank meeting, Georgieva reported that “We face a global recovery that remains “hobbled” by the pandemic and its impact. We are unable to walk forward properly—it is like walking with stones in our shoes!”

She outlined the three stones in her shoes. The first was growth. At the meeting, the IMF is set to lower its forecasts for global growth in 2021 and expects the divergence between the richer Global North and the poorer Global South to widen. The second was inflation: “One particular concern with inflation is the rise in global food prices—up by more than 30 percent over the past year.” And the third was debt: “we estimate that global public debt has increased to almost 100 percent of GDP.” (No mention of private sector debt, which is much more important and at historic highs).

Georgieva posed the risk of what is called ‘stagflation’, ie low or zero growth alongside high or rising inflation. This is the ultimate nightmare for the major capitalist economies – and of course, the worst possible scenario for working people who would bear the brunt of rising prices for household while income growth remains weak; leading a fall in real incomes.

This was the story of the 1970s. So is stagflation coming back in 2022? Let’s look at the GDP growth side first. The evidence is building up that the ‘sugar rush’ recovery in the major economies after the end of the pandemic lockdowns and after the impact of fiscal spending and easy money is flagging. For example, in Q3 2021 just ended, the Atlanta Fed GDP Now! forecast for the US economy suggests a sharp slowdown (compared to consensus calls) to just 1.3% annual rate. And Q4 is likely to be worse. After the ‘sugar rush’ comes the fatigue.

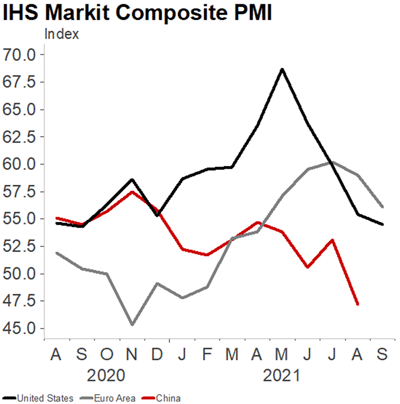

The ‘high frequency’ business activity surveys called the Purchasing Manager’s Indexes (PMIs) are also showing a distinct slowdown in most regions from the peaks of the summer.

And in the US, the latest official data showed the jobs recovery stalled for a second consecutive month in September. Coupled with lower business and consumer confidence, this suggests the ‘sugar rush’ there is also over. In China, the government is grappling with sporadic outbreaks of the Delta coronavirus variant and the risk of a property debt implosion along with an energy shortage. Strong growth over the summer appears to have slowed sharply in the eurozone and UK.

Also, there is the Brookings-FT Tracking Index for the Global Economic Recovery (Tiger) which compares indicators of real activity, financial markets and confidence with their historical averages, both for the global economy and individual countries, capturing the extent to which data in the current period is normal. The latest twice-yearly update shows a sharp snapback in growth since March across advanced and emerging economies.

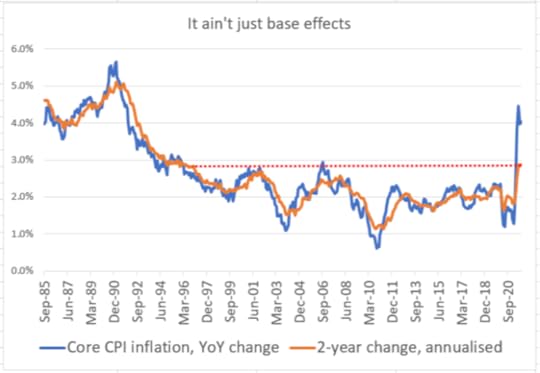

On the other side of the stagflation scenario, inflation rates are rising everywhere. Back in December last year the US Fed’s median forecast for inflation in 2021 was 1.8%. In March that was nudged up to 2.4% and then in June up to 3.4%. It is now 4.2%. Over the same period their median forecast for 2022 has risen from 1.9% to 2.2%. The Bank of England’s and the ECB’s numbers have followed a similar path.

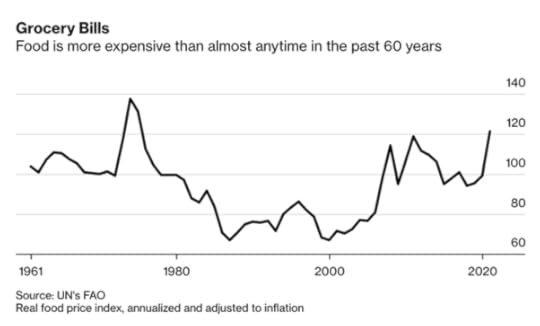

Global grocery bills are rocketing.

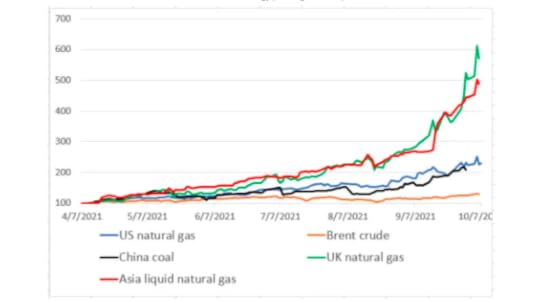

And energy prices have taken off.

What is causing this rise in inflation generally and in food and energy, in particular? The standard macroeconomics view is that there ‘excess demand’. During COVID, consumers built up huge stashes of savings that they could not spend. But now that economies are opening up again, households are spending heavily at a time when global supply chains have been disrupted by the COVID pandemic.

This is the view of financial analysts, Jefferies: “the $2.5tn in excess household cash is an important buffer against stagflation, and we show that excess savings are distributed across the entire income distribution. To date, there has been very little evidence of demand destruction. Real spending is still close to cycle highs for most discretionary spending categories, despite significant price increases…A more rigorous analysis of price and volume changes by the San Francisco Fed shows that demand effects are the dominant driver of inflation at the moment, contributing 1.1% to y/y core PCE as of August. In contrast, supply-side effects contributed only 0.2%. This flies in the face of the prevailing narrative which attributes most of the price increases to supply chain disruptions. Yes, product shortages and supply bottlenecks are real, but they are largely a function of excess demand, rather than supply outages.”

So the Jefferies view is that this situation is just temporary or ‘transitional’, to use Fed Chair Powell’s expression. Once production, employment and investment get going and international supply chain blockages ease, then inflation pressure will also ease and things will get back to ‘normal’.

There are serious doubts about this rosy scenario. First on the demand side, is it really true that released pent up demand is the cause of rising prices? The idea that ‘excess cash’ will simply ‘sop up’ the extra costs of gas and food prices seems unlikely. After all, in the major economies this ‘excess cash’ is mostly in the pockets of the rich, who tend to save rather than spend. Higher prices are more likely to lead to reductions in spending in so-called ‘discretionary items’ as working-class households try to meet the rising costs of food and energy.

Moreover, accelerating inflation in essential goods and services is more likely to be the result of a ‘supply-side’ shock rather than excess demand. “We are not dealing with demand-push inflation. What we are really going through right now is a massive supply shock,” said Jean Boivin, a former Bank of Canada deputy governor now at the BlackRock Investment Institute. “The way to deal with this is not as straightforward as just dealing with inflation.”

On the supply side, there are those who argue that the 2020s are not like the 1970s with its stagflation, but more like the 1950s, when inflation incurred from the disruption and spending during the Korean war gave way to rising investment and profitability, so that industrial output and real GDP growth rates rose and inflation subsided. “With supply shortages set to persist for the next 6 to 12 months, the current period of “stagflation-lite” will persist a while longer. But it is likely to remain a pale imitation of the 1970s stagflation episode. Meanwhile, we do not share the pessimism of those who think that the current supply shortages are just one of a series of stagflationary shocks likely to hit the economy in the coming years.”

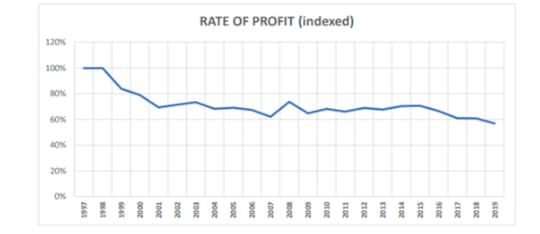

But are the 2020s going to be a new ‘golden age’ for capitalism like the 1950s with high profit rates and investment, real wage rises, full employment and low inflation? I doubt it; first, because the current supply-side ‘shock’ is really a continuation of the slowdown in industrial output, international trade, business investment and real GDP growth that was setting in in 2019 before the pandemic broke. That was happening because the profitability of capitalist investment in the major economies had dropped to near historic lows, and as readers of this blog know, it is profitability that ultimately drives investment and growth in capitalist economies.

In previous posts, I have provided the evidence of the decline in profitability in the US and elsewhere. Brian Green has a new analysis of UK business profitability which gets a similar result “before the UK entered the pandemic, the rate of profit had fallen sharply to stand 20% below the last mini peak in 2015.”

Again, you could even argue that the supply-side shock will remain not just because of low profitability and investment, but also because of the hugely increasing costs of dealing with climate change. This has led to sharp cutbacks in investment in fossil fuel energy exploration and production, putting many economies at risk of an energy supply crisis. This is the irony of market solutions to the global warming problem: driving up carbon emission prices and taxes merely causes a severe reduction in energy production because planning for the replacement of fossil fuel production with alternatives is non-existent.

If rising inflation is being driven by the weak supply-side rather than an excessively strong demand side, monetary policy won’t work. Monetary policy works by trying to raise or lower demand. If spending is growing too fast and generating inflation, higher interest rates supposedly dampen the willingness of companies and households to consume or invest by increasing the cost of borrowing. But even if this theory were correct, it does not apply when prices are rising because supply chains have broken, energy prices are increasing or there are labour shortages. As Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, has said: “Monetary policy will not increase the supply of semiconductor chips, it will not increase the amount of wind (no, really), and nor will it produce more HGV drivers.”

Indeed, as I have argued ad nauseum on this blog, pumping cash or credit into the financial system with ‘quantitative easing’ does not work to boost the economy if the ‘supply-side’ is not growing through lack of profitability. You can take a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink. That disconnection applies just as much when central banks tighten policy (ie withdraw credit and raise policy interest rates). Reducing demand will do little if supply is stagnant for other reasons.

Nevertheless, central banks are starting to tighten. Interest rates have already risen in Norway and in many emerging economies, while the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have made moves to tighten monetary policy. This won’t get inflation rates down, but merely increase the risk of a recession as debt servicing costs rise for companies already low on profits. That’s the dilemma for central banks and governments as they debate the issue of stagflation this week in Washington.

But let me finish this long post by reminding readers that mainstream economics has no coherent theory of inflation. As Charles Goodhart, a professor at the LSE and former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee, remarked: “the world at the moment is in a really a rather extraordinary state because we have no general theory of inflation”. The two main theories offered: the monetarist theory that money supply drives inflation; and the Keynesian theory that inflation is caused by tight labour markets driving up wage costs, have been debunked by the evidence.

So the mainstream has fallen back on a theory of inflation based on ‘expectations’. As Goodhart remarks, this is “a bootstrap theory of inflation”; that as long as inflation expectations remain anchored, inflation itself will remain anchored. But expectations depend on where inflation already is and so provide no predictive power. Indeed, a new paper by Jeremy Rudd at the Federal Reserve concludes; “Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and firms’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors.”

As regular readers of this blog may know, G Carchedi and I have been developing an alternative Marxian theory of inflation. The gist of our theory is that inflation in modern capitalist economies has a long-term tendency to fall because wages decline as a share of total value-added; and profits are squeezed by a rising organic composition of capital (ie more investment in machinery and technology relative to employees). But this tendency can be countered by the monetary authorities boosting money supply so that money price of goods and services rise, even though there is a tendency for the growth in the value of goods and services to fall.

We have tested this theory during the COVID pandemic slump for US inflation. During the year of the COVID, corporate profitability and profits fell sharply. Wage bills also fell. As our theory predicted, the results were deflationary. But the Fed pumped in more money. US M2 money supply was up 40% in 2020. So US inflation, after dropping nearly to zero in the first half of 2020, moved back up to 1.5% by year end.

In slumps, the velocity of money, which is the pace of turnover of the existing money supply in an economy, falls. People and businesses make fewer transactions and instead tend to ‘hoard’ money. That was certainly the case in 2020, where the velocity fell to a 60-year low. Such a fall is hugely deflationary. But in 2021, the velocity of money stopped falling.

In 2021, all the factors that led to a near zero inflation rate in the US in mid-2020 began to reverse. At that time last year, we made a forecast that if profits and wages began to rise (wages, say by 5-10%; money supply by about 10%, then our model suggested that US inflation of goods and services would rise, perhaps to about 3.0-3.5% by end 2021. Actually, money supply has continued to rise faster than we forecast. And so US inflation is now over 4%, not 3.0-3.5% as we forecast.

What our theory of inflation suggests that the US economy over the next few years is more likely to suffer from stagflation ie 3%-plus inflation with less than 2% growth, than from either deflation or inflationary ‘overheating’ (4%-plus).

October 5, 2021

China at a turning point?

The debt problems afflicting China’s real estate market deepened this week after another property developer defaulted on its bonds and the world’s most heavily indebted property group Evergrande extended a suspension of its shares into a second day without explanation. Fantasia Holdings, a mid-sized developer, that just weeks ago assured investors it had “no liquidity issue”, said in a stock exchange filing that it “did not make the payment” on Monday of a $206m bond maturing that day, triggering a formal default. The default adds to fears that a crisis at Evergrande will spread to include more of China’s property developers, which account for a large portion of the Asian high-yield bond market.

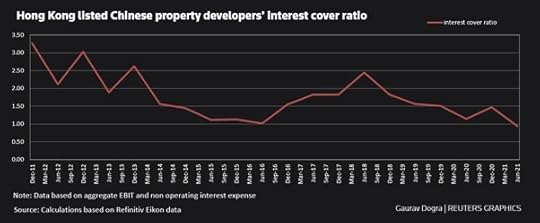

Evergrande missed an interest payment on an offshore bond on September 23, triggering a 30-day grace period before a formal default, and has yet to provide any announcement on the matter. But even before China Evergrande Group’s debt crisis sent the country’s property sector into a tailspin, Chinese property firms were struggling to earn enough to make interest payments on their debt. At the end of June, the aggregate interest coverage ratio of 21 big Hong Kong-listed Chinese real estate developers fell to 0.94, the worst in at least a decade, according to Reuters calculations based on Refinitiv data.

Hong Kong listed Chinese property developers’ interest cover ratio

In other words, China’s private property sector are now composed of ‘zombie’ companies just like 15-20% of companies in the major capitalist economies. The question now is whether the Chinese authorities are going to allow these firms to go bust. Shares in Huarong, China’s biggest bad debt manager, were suspended for months earlier this year after the company delayed its financial reports before finally unveiling a record loss in August. The delays sparked a debate over the extent to which Beijing will step in to help distressed companies.

The real estate sector faces pressure from Beijing to reduce leverage after decades of debt-driven expansion that helped fuel the country’s rapid economic growth. The government’s financial authorities have set three ‘red lines’ that financial and property companies cannot cross. Back in 2020, the People’s Bank of China and the Ministry of Housing announced that they’d drafted new financing rules for real estate companies. Developers wanting to refinance are being assessed against three thresholds: 1. a 70% ceiling on liabilities to assets, excluding advance proceeds from projects sold on contract; 2. a 100% cap on net debt to equity; 3. a cash to short-term borrowing ratio of at least one. Developers will be categorized based on how many limits they breach and their debt growth will be capped accordingly. There are now several large property companies in that situation.

The government is faced with a dilemma. If it allows Evergrande and other property companies to go bust, then millions of homes for people may not be built and the losses incurred by lenders to, and investors in, these companies could have a cascading effect across the economy. On the other hand, if the authorities bail out the companies, then the speculation could continue as the real estate sector could assume that they had government backing for all their speculative projects and they were ‘too big to fail’ – that’s so-called ‘moral hazard’; the same dilemma that faced the US authorities in 2008 when the property markets went belly up and the mortgage lenders and banks hit the dirt.

Most likely, the government will do something in between. It will ensure that the homes promised by the likes of Evergrande to 1.8m Chinese will be built by taking over the projects; already local authorities have moved in to take over local projects from Evergrande. At the same time, central government and the PBoC will allow Evergrande to default on investors and bond holders (to a degree). If those losses spill over into the financial sector, the Chinese government has plenty of financial slack to absorb the hit, as it has done in the past. For example, Evergrande’s debt of $300bn should be compared to total credit outstanding in China of $50trn, ie not very large. Moreover, if the final bill falls on the state and the state banks, reserves there can easily digest the losses.

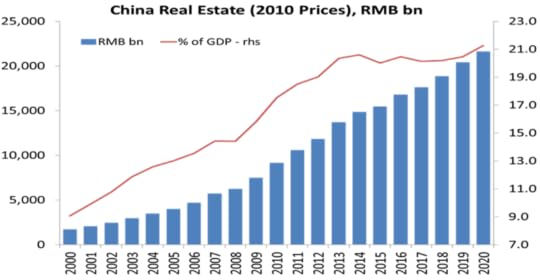

The real problem is that in the last ten years (and even before) the Chinese leaders have allowed a massive expansion of unproductive and speculative investment by the capitalist sector of the economy. In the drive to build enough houses and infrastructure for the sharply rising urban population, the central and local governments left the job to private developers. Instead of building houses for rent, they opted for the ‘free market’ solution of private developers building for sale. Evergrande-like development in China wasn’t just capitalism doing its thing. It was capitalism facilitated by government officials for their own purposes. Beijing wanted houses and local officials wanted revenue. The housing projects helped deliver both. The result was a huge rise in house prices in the major cities and a massive expansion of debt. Indeed, the real estate sector has now reached over 20% of China’s GDP.

This growth in real estate and other unproductive activities in finance and consumer media has been driving China’s official annual growth rate. As the productive sector of industry, manufacturing, hi-tech communications, etc grew more slowly, the authorities fooled themselves into claiming that real GDP growth targets of 6-8% a year were being met but this was increasingly because of the real estate market. Of course, homes need to be built, but as President Xi put it belatedly, “homes are for living in, not for speculation.”

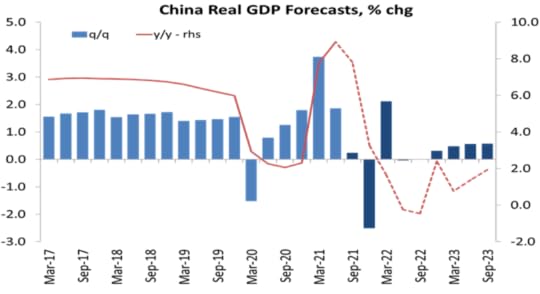

There is no getting away from the fact that there will be an immediate hit to growth from Evergrande and the associated spill-overs. China’s recovery from the pandemic slump had already been faltering, partly because of new COVID variant eruptions that caused mini lockdowns, but mainly because investment and trade growth is being limited by the patchy recovery in the major capitalist economies. So China will be lucky to hit a 2% rate for the remainder of this year.

More worryingly, even if a more disorderly spiral across the property market can be averted, the end of the credit-fuelled real estate model (or even a tempering of it) will mean lower growth. That’s the issue. The ‘Western China experts’ are convinced, either that China is finally going to have a financial implosion (something forecast nearly every year for the last 20 years); or that the economy will fall into a low growth path of 2-3% a year, hardly higher than the ‘mature’ capitalist economies.

One reason presented is that the working population is declining (indeed, it is reported that China’s fertility rate is now below that of Japan) to the point where the population could be halved by the end of the century. Another reason popular with the experts is that China’s investment-driven, export-led model for growth is over. Instead of investment, China should now rely on boosting consumption for the masses, as in the US and most of the G7 – and that means reducing the size of the state through privatisations and opening up the economy to even more ‘consumer markets’. Moreover, exports may no longer make much of a contribution to China’s growth rate because of the trade and technology barriers being erected by the US and its allies to isolate and curb China’s progress. The Chinese government is aware of this. That is why the Xi leadership talks of a ‘dual circulation’ development model, where trade and investment abroad is combined with production for the huge domestic market.

As I argued in a previous post: “Gross investment has averaged over 47% of GDP since 2009. But real GDP growth has been slowing. So China’s productivity return on new investment (or the productivity of capital input) is declining. Back in 2006, before the global crisis, it took 2.9 units of investment to increase real GDP by 1 unit. In 2014, it now takes 6.6 units. China needs to return to its long-term average TFP [total factor productivity] rate of over 2.5% a year to sustain 7% real GDP growth.” In previous posts, I have attacked the arguments of the Western experts that China is about to have a financial crash like the 2008 one in the major capitalist economies; or that its growth rate will shrink to near nothing because of the failings of its state-led economic model.

Growth in real GDP depends on two factors: growth in the size of the workforce; and growth in the productivity of existing workforce. If the former slows or even falls, then a fast enough growth in productivity can compensate or even overcome the former. Productivity growth depends primarily on more capital investment in technology; better technology that saves labour time and a better trained workforce that can deliver more in less time. The problem for China from hereon is that its capitalist sector has been allowed to expand (in a “disorderly” fashion, says Xi) to the point where the contradictions of capitalist production are beginning to damage China’s formerly spectacular rise.

Indeed Xi’s call for ‘common prosperity’ is a recognition that the capitalist sector so fostered by the Chinese leaders (and from which they obtain much personal gain) has got so out of hand that it threatens the stability of Communist Party control. Take billionaire Jack Ma’s comment before he was ‘re-educated’ by the authorities: “‘Chinese consumption is not driven by the government but by entrepreneurship, and the market,’… In the past 20 years, the government was so strong. Now, they are getting weak. It’s our opportunity; it’s our show time, to see how the market economy, entrepreneurship, can develop real consumption.’”

—The Guardian, 25 July 2019

The profitability of the capitalist sector has been falling for some time, just as it has the major capitalist economies. So Chinese capitalists have looked for higher profits in unproductive sectors like real estate, consumer finance and media – that’s where the billionaires are found. These sectors are now blowing up in the faces of the Chinese leaders.

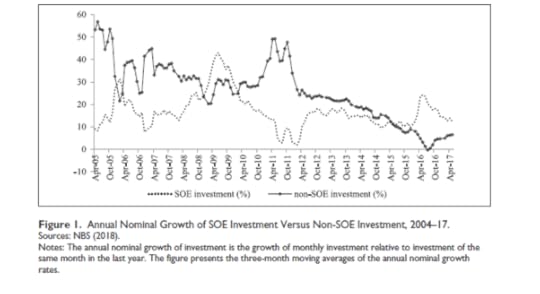

State sector investment has always been more stable than private investment in China. China survived, even thrived, during the Great Recession, not because of a Keynesian-style government spending boost to the private sector as some economists, both in the West and in China argued, but because of direct state investment. This played a crucial role in maintaining aggregate demand, preventing recessions, and reducing uncertainty for all investors. When investment in the capitalist sector slows down as it does as profit growth slows or falls, in China the state sector steps in. SOE investment grew particularly fast over 2008–09 and 2015–16 when the growth of non-SOE investment slowed down. As David Kotz showed in a recent paper: “Most of the current studies ignore the role of SOEs in stabilizing economic growth and promoting technical progress. We argue that SOEs are playing a pro-growth role in several ways. SOEs stabilize growth in economic downturns by carrying out massive investments. SOEs promote major technical innovations by investing in riskier areas of technical progress. Also, SOEs adopt a high-road approach to treating workers, which will be favorable to the transition toward a more sustainable economic model. Our empirical analysis indicates that SOEs in China have promoted long-run growth and offset the adverse effect of economic downturns.”

What is needed is not a further expansion of consumer sectors by opening them up to ‘free markets’, but instead state-led investment into technology to boost productivity growth. And that state sector investment can be directed towards environmental goals and away from uncontrolled expansion in carbon-emitting fossil fuel industries. As Richard Smith has put it: “The Chinese don’t need a higher standard of living based on endless consumerism. They need a better mode of life: clean unpolluted air, water and soil, safe and nutritious food, comprehensive public health care, safe, quality housing, a public transportation system centred on urban bicycles and public transit instead of cars and ring roads.”Rising personal consumption and wage growth will follow such investment, as it always does.

But that means it is time for the Chinese government to make a turn back towards state investment and planning of housing, technology and public services and involve China’s highly educated industrial and urbanised workers in that planning. Unfortunately, China’s leaders do not want any shift towards the latter, so the danger of long-term economic slowdown will remain.

October 2, 2021

MMT and Marxist monetary theory – a reply to Bill Mitchell by a man with no name

Bill Mitchell is a Professor in Economics and Director of the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE), at the University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia. Professor Mitchell is one of the world’s leading exponents of what is called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). MMT has gained traction in the labour movement in recent years on the grounds that it provides powerful new arguments to refute the claims of mainstream economics that governments need to balance their books ie keep spending in line with tax revenues and not allow government debt to spiral. In order to balance the books, so the mainstream argument goes, government spending must be cut, taxes raised and debt levels reduced, even if that means more poverty and worse public services. There is no alternative – as Margaret Thatcher once said.

However, MMT is supposed to offer the answers to the Austerians, both theoretically and in alternative policies. Professor Mitchell, among other MMT supporters, has tirelessly campaigned for the adoption of MMT measures in the labour movement as the key answer to ending unemployment and austerity as policies that must be accepted by the labour movement.

Now I have spent much ink on my blog and in papers discussing and debating the merits of MMT as the answer to capitalist policies of austerity and unemployment. In my humble opinion, MMT falls short of achieving its claims and objectives because it ignores the social structure of a capitalist economy and argues that the recognition and manipulation of the monetary system can solve the problems without ending capitalism.

At a recent fringe meeting at the UK Labour party conference, I was invited to debate the merits of MMT with Professor Mitchell contributing by zoom from Australia. Shortly after the debate, Professor Mitchell posted on his blog, the following:

“I gave a talk at the Resist Event in Brighton UK last Sunday evening. On the panel was a person who dismissed Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) as irrelevant to the real challenges that arose under capitalism and he invoked Marx a lot. It was not a very illuminating interchange because not only did he misrepresent what MMT was but, in my view, he also seemed to think that we could extrapolate Marx’s scant ideas of money directly into the situation faced by nations today.”

Well guess what? This ‘a person’ was me, but I shall remain nameless as far as Professor Mitchell was concerned. And it was not strictly true that Professor Mitchell “gave a talk” to which we all listened. It was a discussion or debate with three speakers: Mitchell, myself (suitably named at the event) and Carlos Gonzales of ‘fiat socialism’ fame.

In his posts, Professor Mitchell seeks to dismiss my arguments that MMT does not take us very far in explaining the nature of a capitalist economy or providing decisive economic policies that will help labour. Professor Mitchell thinks that I have not only “misunderstood MMT but also have a scant understanding of Marx’s monetary theory”. He says Marx would never have agreed that government spending could not end unemployment or that capitalists would not increase production and employment if government spending orders came in.

In the debate I said that Marx attacked the idea that, just by manipulating money, governments could solve unemployment and poverty. This was the view of Pierre Proudhon, the leading socialist of the mid-19th century. Marx responded: “Can the existing relations of production and the relations of distribution which correspond to them be revolutionized by a change in the instrument of circulation, in the organization of circulation? Further question: Can such a transformation of circulation be undertaken without touching the existing relations of production and the social relations which rest on them?”

In his post, Professor Mitchell refers to Professor Duncan Foley (at least he gets named!) who asserts that for Marx, “the movement of commodities is largely determined outside the monetary sphere, and that movements of money in most cases are determined by those commodity movements…..The theoretical question then arises as to which is the determining factor. Does the movement of money determine the movement of commodities or the movement of commodities determine the movement of money?” Mitchell rejects Foley’s approach to money and reckons that Marx is out of date with this critique of Proudhon because back then money was gold or backed by gold, which meant its value was anchored to the production cost of gold mining. Now, in the modern world of ‘fiat currencies’, the state can create money that is not tied to the value or price of gold and therefore the state can increase the amount of money at will.

I do not agree that this makes Marx out of date. Contrary to the view of MMT, fiat money does not change the role or nature of money in a capitalist economy. Its value is still tied to the labour time taken in capitalist accumulation. Commodity money (gold) contains value while non-commodity money represents/reflects value, and because of this, both can measure the value of any other commodities and express it in price-form. Modern states are clearly crucial to the reproduction of money and the system in which it circulates. But their power over money is quite limited – and as Marx would have said, the limits are clearest in determining the ‘value’ of money. The state mint can print any numbers on its bills and coins, or the central bank add any number of digits to the government’s bank account, but that cannot decide what those numbers refer to. That is determined in countless price-setting decisions by mainly private firms, reacting strategically to the structure of costs and demand they face, in competition with other firms.

The MMT supporters, in effect, reckon that any reduction in private sector investment can be replaced or added to by government investment ‘paid for’ by the ‘creation of money out of thin air’. But this money will lose its value (ie purchasing power) if it does not bear any relation to value created by the productive sectors of the capitalist economy, which determine the amount to value generated and still dominate the economy. Instead, the result will be rising prices and/or falling profitability that will eventually choke off production in the private sector. Unless the MMT proponents are then prepared to move to a Marxist policy conclusion: namely the appropriation of the finance sector and the ‘commanding heights’ of the productive sector through public ownership and a plan of production, thus curbing or ending the law of value in the economy, the policy of government spending through unlimited money creation will fail.

As far as I can tell, MMT exponents studiously avoid and ignore such a policy conclusion – perhaps because like Proudhon they misunderstand the reality of capitalism, preferring ‘tricks of circulation’; or perhaps because they actually oppose the abolition of the capitalist mode of production (indeed, that is the view of most MMT exponents, although not Professor Mitchell). You see, MMT is not relevant to a social transformation of society, Professor Mitchell argued in the debate – that is a separate question. Right-wing, pro-capitalists can and do accept MMT.

Professor Mitchell goes on to highlight something in a post by this unnamed “critic on the panel”. Yes, it’s me again – at least I am now on the panel. In one of my blog posts on MMT HERE, I had a plotted figure that shows that there is no inverse correlation between increased government spending and unemployment. On the contrary, among OECD countries, the higher the level of government spending, the higher unemployment!

Professor Mitchell now applied his superior understanding of statistics to this result. “In Statistics 101 or Econometrics 101, one of the first things students learn is to be careful in attributing causality. Correlation is not causality.” Indeed, how could I be so stupid! But I’m not. Of course, this correlation does not prove causation. Indeed, that is what I conclude in the post: namely that there must be other reasons than the amount of state spending to explain unemployment rates. As Mitchell says: “We would expect government spending to be higher in nations that had higher unemployment because of increases in welfare outlays and other non-discretionary responses to declining non-government spending (that was driving up unemployment).” Exactly, because what drives unemployment rates in a capitalist economy is the rate of investment and employment made by the capitalist sector. When there is a slump in investment and people are laid off to join what Marx called “the reserve of army of labour”, government spending rises as benefit spending increases. Having said that, the graph suggests that there is no evidence that unemployment falls when government spending rises, because there are much more compelling causes that affect employment.

In his second post dealing the views of the unnamed ‘critic’ of MMT, Professor Mitchell claims that he can show “how nonsensical it is to claim that capitalist firms will not expand production if they have idle capacity and can increase profits by responding to increased sales orders.” And that “the government sector is not bound by the so-called dynamics of private capital accumulation and under certain conditions can typically command productive resources from the non-government sector through increased spending without introducing inflationary pressures.”

In this post, Professor Mitchell takes us through a short course on the history of crisis theory, from Say and Ricardo’s views that general overproduction was impossible, to the underconsumption theories of Sismondi, Luxemburg and others. And then he says: “Marx considered the accumulation process would lead to an excessive build-up of capital which would suppress the rate of profit and it was this dynamic that generated the crisis.” Well yes, that was Marx’s theory of crises, more or less in a nutshell.

But having said this, Mitchell quickly takes a step back: “But, we need to be careful in unpicking the logic here. Yes, the owners of capital control production and employment and their expectations of future returns dictate the rate at which the capital stock accumulates over time. But equally, when considering the causes of crises, we cannot avoid focusing on the realisation issue because it was through market exchange that capitalists were able to realise the surplus value they had expropriated in the production process by exploiting their workers into the monetary form of profit.” Mitchell then claims Marx for his own theory of crises “As we move through history, the scholars that followed Marx clearly understood that effective demand was a causal factor in determining unemployment and recession.” So there we have it. Forget Marx’s profitability theory as the driver of accumulation and thus investment demand. Let’s revert to the same position as orthodox Keynesians: that crises are due to a lack of ‘effective demand’.

Now I have spent much print and digital inputs from my computer showing that the Keynesian-Mitchell lack of effective demand theory is an inadequate explanation of regular and recurring crises in capitalist production. You can read my arguments here. https://thenextrecession.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/the-profit-investment-nexus-michael-roberts-hmny-april-2017.pdf

But in this post let me mention just one point. Why does capitalist production seem to have enough effective demand for years or even a decade, and then suddenly investment and production collapses, unemployment rockets and there is a ‘lack of effective demand’? The Keynesian/MMT has no answer to this question. The answer lies in the contradictions within the capitalist mode of production, specifically in the tendency for the profitability of capital to fall over time and eventually lead to a fall in total profits and value creation. Then investment demand collapses, leading to a lack of aggregate demand so that capitalist production cannot be ‘realised’. This is the causal sequence in crises.

Mitchell invokes the post-Keynesian arguments of Michel Kalecki to justify his view that it is aggregate demand that drives sales, production and profits. Professor Mitchell quotes Kalecki: “to offset any tendency for the rate of profit on the expanded capital stock to fall and thus offset the possibility of a crises (so very Marxian – really MR?), Kalecki wrote (page 87): “… if effective demand adequate to secure full employment is created by stimulating private investment the devices which we use for it must cumulatively increase to offset the influence of the falling rate of profit.”