Michael Roberts's Blog, page 32

February 7, 2022

The sugar runs out

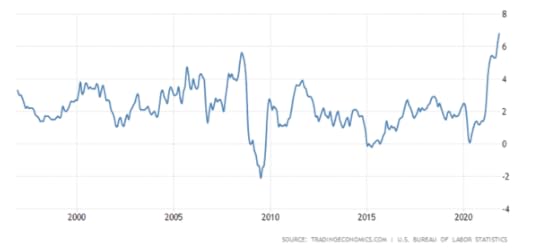

At the beginning of January, I posted my economic forecast for the world economy in 2022. I argued that, although the major capitalist economies were likely to expand during 2022, real GDP, investment and income growth was likely to be much slower than the fast rebound in 2021 from the global pandemic slump of 2020. Last year had seen a leap back, as economies reopened after the first and second COVID waves of 2020. In the major economies, especially the US, that rebound had been helped by a significant injection of easy credit, zero interest rates and considerable fiscal spending. This rebound was akin to the ‘sugar rush’ that we get if we ingest a large dollop of sweet things to get ourselves going. There is a big boost, but it does not last.

And that seems to be the case as we go into 2022. Much was made of US annualized 6.9% real GDP growth in Q4 2021, much higher than 2.3% in Q3 and well above forecasts of 5.5%. It was the strongest GDP growth in five quarters. But this headline figure hid some serious holes in the ‘growth story’. The biggest contribution to that 6.9% points came from inventory stocking (4.9% pts) – apparently car dealers restocking vehicles still to sell. Household spending contributed 2.2% points and business investment just 0.28% pts. Net exports (exports minus imports) contributed nothing; and government spending made a negative contribution of 0.5% pts (as taxes outstripped spending). Leaving out inventories, the US economy expanded by just 2% in Q4. Over the whole of 2021, the US economy jumped 5.7% after contracting 3.4% in 2020. US real GDP is now 3.1% higher than in pre-COVID 2019, but still 1.2% pts behind where GDP would have been if there had been no COVID slump.

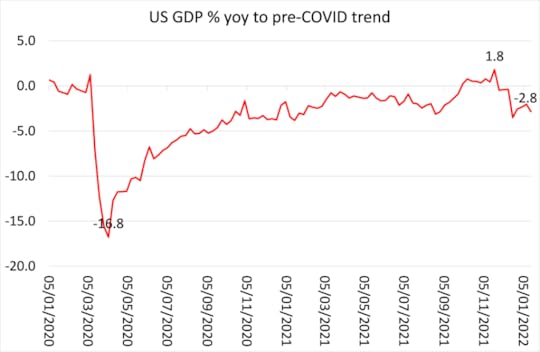

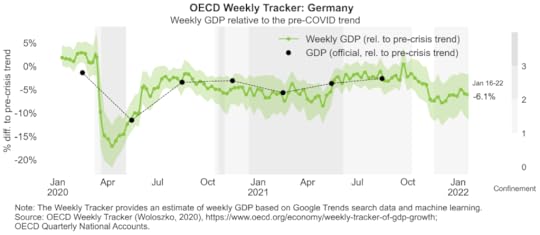

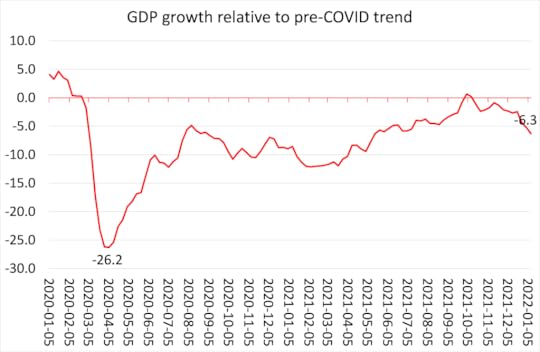

Indeed, if you consult the new OECD weekly GDP tracker based on Google activity indexes, US real GDP was falling back going into January and the gap between current growth and the pre-COVID trend was widening, to -2.8% below pre-COVID trend growth. And it’s been slipping back since November 2021 under the pressure of the Omicron wave.

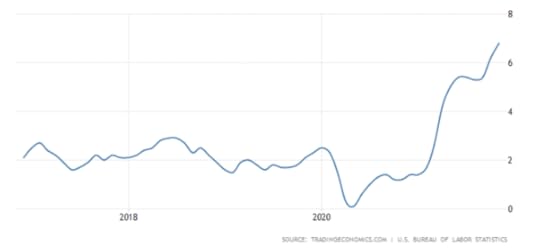

OECD weekly growth tracker

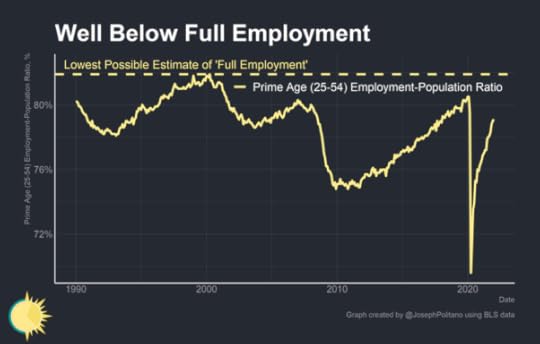

OECD weekly growth trackerLast week, the US jobs market rose by 467,000 more employees according to official estimates– much more than expected and completely in contrast with a survey of private sector employment (called the ADP) which fell 301,000. Again, the cry was that the US economy was making great strides in recovering from the pandemic slump. But again, the headline figure hid some of truth. The reason for the sharp jump in the official figure was a revision of the census data which had been underestimating the number of Americans already at work in 2021. That was adjusted for by upping the November and December estimates. After accounting for this one-off census adjustment, jobs in January actually fell by 272k, while the household survey (another measure of jobs) showed a fall of 90k – the worst drop since the beginning of the pandemic. The reality is that only 80% of those Americans in the prime working age group (25-54 years) who had jobs before COVID have them now.

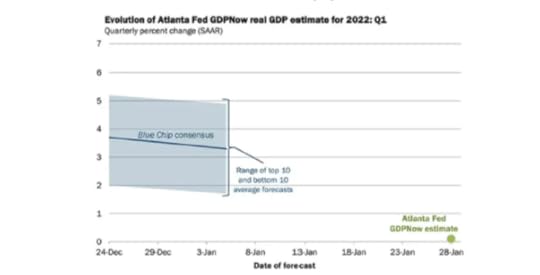

And consensus forecasts for US real GDP growth in this first quarter of 2022 have been drastically cut back. The Atlanta Fed GDPNow forecast currently stands at near zero for the current quarter (although that forecast will no doubt rise as more data come in) and the consensus forecast is just for 2.5%.

Leading investment bank Goldman Sachs reckons US economic growth will slow to just 0.5% yoy in Q1 2022. That’s down from its previous estimate of 2.2% and GS has also cut its forecast for the whole of 2022 from 3.8% to 3.2%.

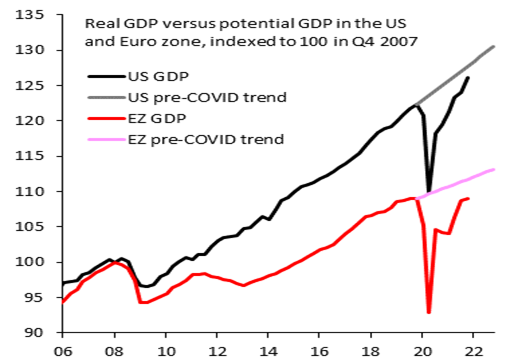

It’s similar but worse story for the Eurozone. Eurozone real GDP rose 0.3% in Q4 2021. This was the slowest quarterly growth in 2021 as the Omicron wave hit. That meant Q4 2021 real GDP rose 4.6% compared to Q4 2020. For the year as a whole, real GDP rose 5.2% after a 6.4% contraction in 2020. This was the fastest expansion since 1977 but still slower than the US rise of 5.7%. But as in the case of the US, the rise in Q4 GDP was mostly from inventory stocking and not from sales, so the rate of growth will drop sharply in Q1 2022. Eurozone growth continues to lag the US. The US is closer to its pre-COVID GDP trend (which was already a weak 2.2% annual growth). The Euro zone is 2.5% below a much weaker 1.2% trend.

For example, Germany is some 6% pts below its pre-COVID trend according to the OECD.

So the prospects for the recovery in 2022 now look worse than the IMF forecast last October: the main culprits, the IMF argues, being the Omicron Covid-19 variant, supply shortages and unexpectedly high inflation. The global economy remains 2.5% points below its pre-COVID trend and the IMF now expects global growth to be about 4.4%, with US at just 4% (but note GS forecast above) and China at 4.8%. Given the current data, these forecasts look optimistic.

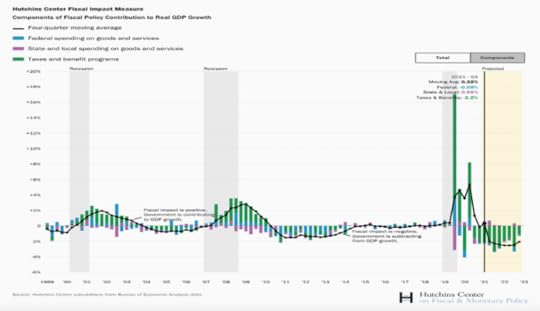

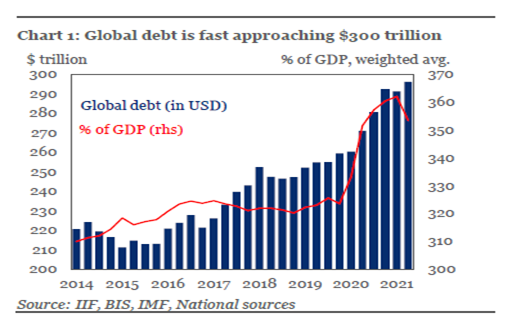

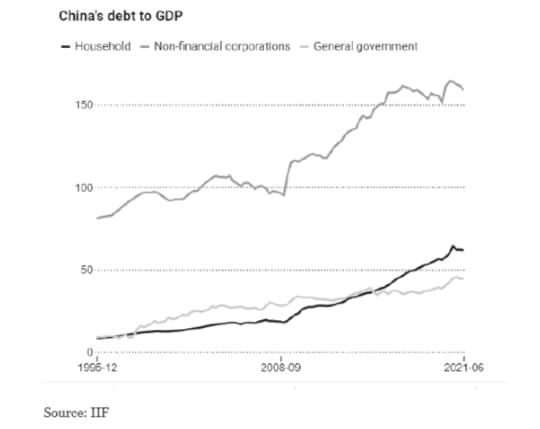

Why is the ‘sugar rush’ fading? It’s not just the impact of the Omicron wave. The main reasons I outlined in my January post. First, there had been a significant ‘scarring’ of the major economies from the COVID pandemic in jobs, investment and productivity of labour that can never be recovered. This was exhibited in a huge rise in debt, both public sector and private, that weighs down on the major economies like the permanent damage of ‘long COVID’ on millions of people.

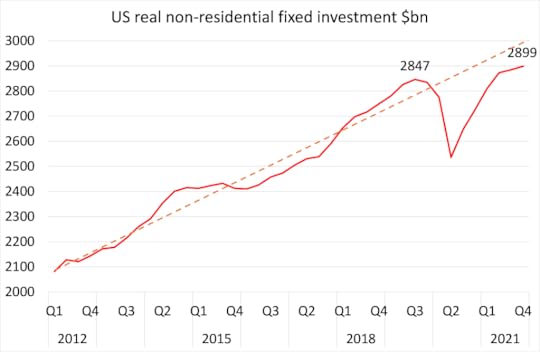

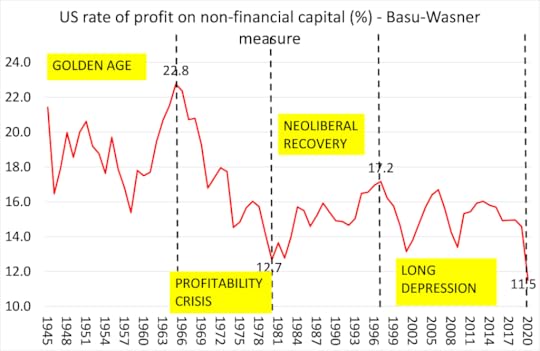

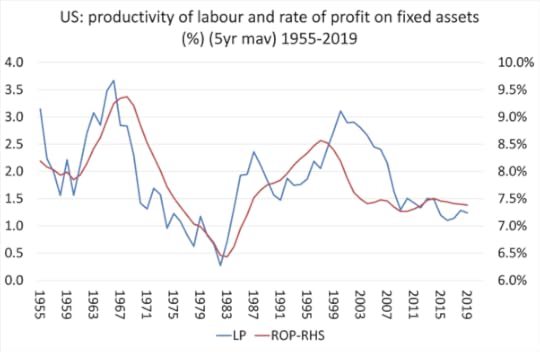

This ‘scarring’ was also exhibited in a fall in average profitability of capital in the major economies in 2020 to a new low, the revival of which in 2021 was not sufficient to restore profitability even to the level of 2019. With average profitability in the major economies at lows, there is no incentive to increase investment sufficiently to boost supply. US productive investment, although recovered from the pandemic slump is still below the pre-COVID trend.

BEA, author calcs

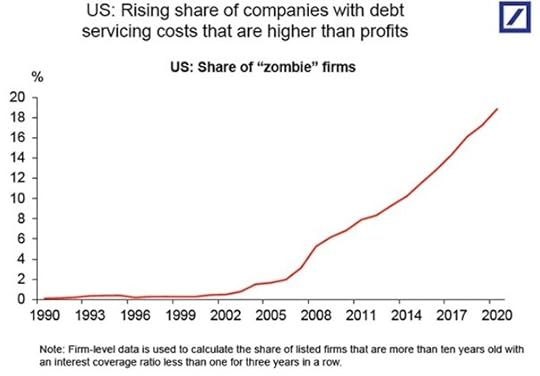

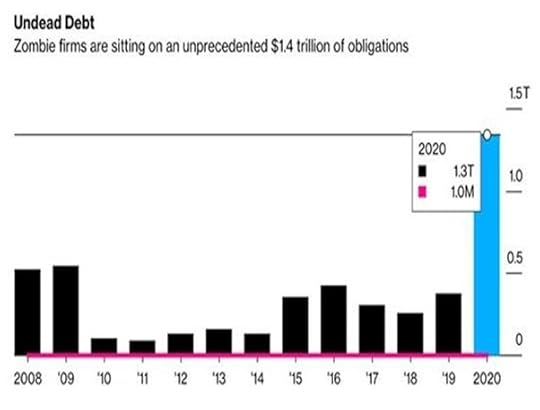

BEA, author calcsThis raises an increased risk of a debt crisis in 2022 that will implode the bubble in financial assets, fuelled by cheap credit for the last two years. Such is the size of corporate debt and the large number of so-called ‘zombie companies’ that were not even making enough profit to cover the servicing of their debts (despite very low interest rates), a financial crash could ensue.

Already in January the huge stock market boom has ‘corrected’. In particular, the tech and media stocks that have driven the boom: Facebook, Alphabet, Microsoft and Netflix have taken a tumble along with the electric car phenomenon of Tesla.

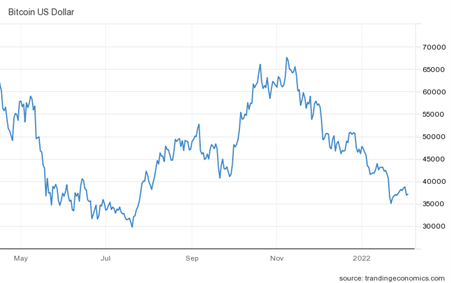

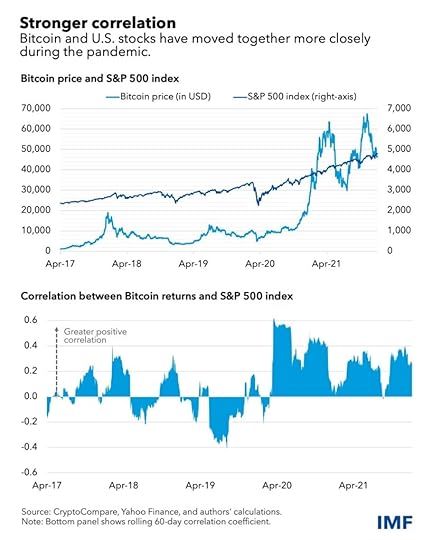

And that other crazy bubble of the COVID period, cryptocurrencies, has also taken a hit.

The IMF has pointed out that the correlation between crypto and equity markets has been trending up strongly. “Crypto is now very closely tied to what is happening in equities. We can’t just dismiss it,” said IMF director of monetary and capital markets, Tobias Adrian. What this shows is that cryptocurrencies are not a new form of money but merely another speculative financial asset that will go up and down with stocks and bonds.

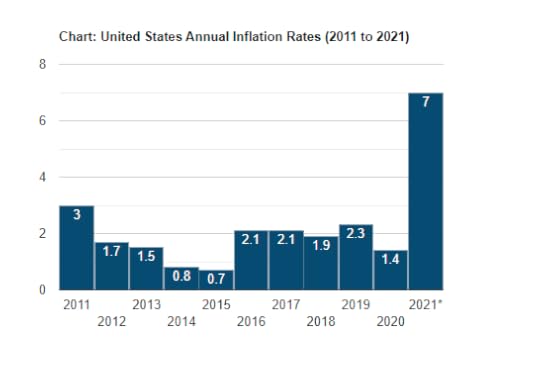

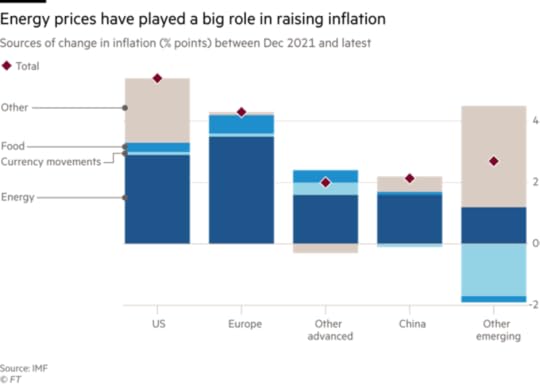

In my view, it’s the slowing down of the major economies and the continued supply bottlenecks in meeting consumer demand that has led to the huge spike in inflation rates.

That is revealed particularly in energy prices, the main driver of inflation.

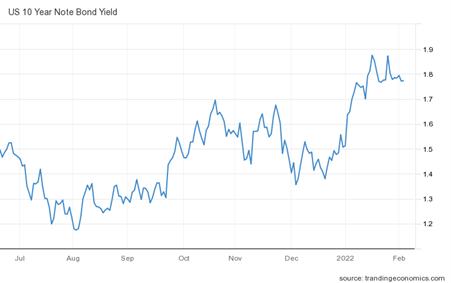

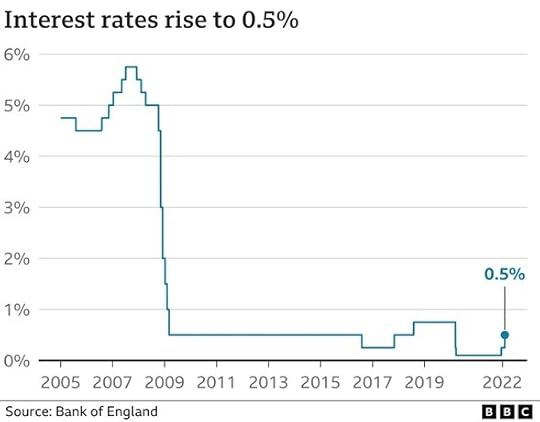

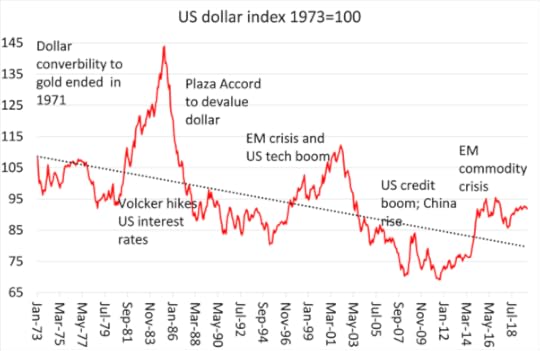

And as I have discussed before, this puts central banks in a dilemma. Do they hike their policy interest rates to try and control inflation but risk a financial market crash and a recession; or do they hope that inflation rates will subside during this year and they can avoid provoking a crisis? The answer is that they do not know. But with inflation rates still rising, the leading central banks are grudgingly reversing their easy money policies of the last ten years. The Fed is ‘tapering off’ its bond purchases and preparing to hike interest rates several times this year. The Bank of England has already raised its policy rate twice while forecasting inflation to reach well over 7%. And even the ECB is talking about ‘tightening’ policy later this year.

The reality is that central banks have no real control over inflation anyway. But even so, they are trying. As a result, already market interest rates are rising. The US treasury bond, the benchmark floor for corporate borrowing, is on the rise with yields up 50bp.

This increases the risk of a corporate debt crisis with such a large section of companies in the major economies already in a ‘zombie’ state (ie not making sufficient profits to ‘service’ their existing debts).

As for the so-called emerging economies – they are already in a dire state. According to the IMF, about half of Low Income Economies (LIEs) are now in danger of debt default. Global debt has now reached $300trn, or 355% of world GDP. It is estimated that a 1% point rise interest rates increases global interest payments from $10trn a year to $16trn, or 15% of world GDP. And with a 2% pt rise, interest costs of $20trn or 20% of GDP. Then not only will several poor countries being forced to default, so will many weaker companies in the advanced economies – causing a ricochet effect through the corporate sector.

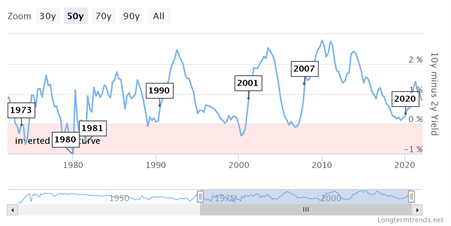

In the last 70 years, whenever the US inflation rate rose above 5% a year, a recession was necessary to get it down. And financial investors are taking note. That is revealed in what is called the ‘yield curve’ in government bonds, ie the gap between the interest rate on long-term bonds (10yr) and short-term ones (3m or 2yr). That ‘curve’ has been flattening.

Historically, whenever the curve completely flattens or even ‘inverts’ ie the interest rate on long-term bonds is lower than that on short-term bonds, a recession usually follows. The curve is flattening now because investors are expecting the Federal Reserve to hike interest rates sharply this year. If investors start to think that the economy is also slowing towards stagnation, they will then buy safe long-term bonds and the interest rate will fall on those. The yield curve will invert. It will be an indicator of a slump coming.

February 4, 2022

The UK’s ‘economygate’

The UK prime minister Boris Johnson is currently in danger of losing his job because of the blatant flouting by him and his staff of the COVID restriction rules imposed by his own government on the rest of the British people. But rather than ‘partygate’, the rocky road ahead for the economy and its impact on living standards for the many is much more likely to destroy the fortunes of this right-wing Conservative government at the next election (probably in 2024).

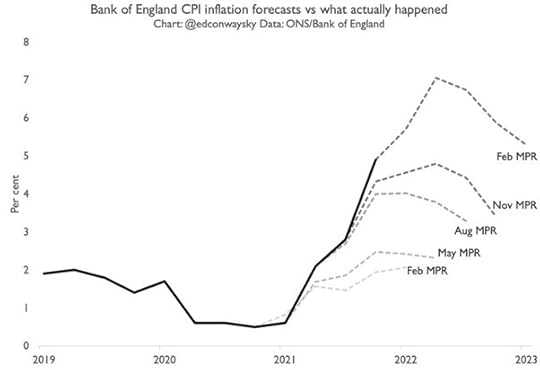

What a mess the UK economy is in. At its monetary policy meeting yesterday, the Bank of England (BoE) forecast the year-on-year rate of inflation in prices would reach 7.25% this spring. This is after forecasting just 4% at its last meeting. Indeed, the BoE’s forecasts have been wildly short of reality for the last year.

BoE

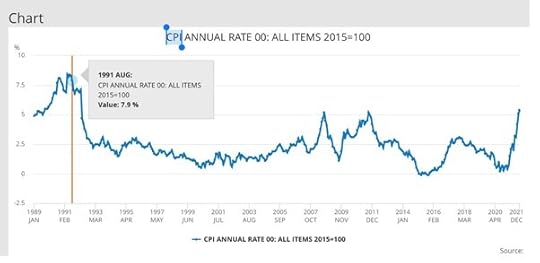

BoEIf inflation hits 7.25% in April, that would be the highest CPI figure since August 1991, just after the first Iraq War oil shock. It hasn’t risen to this level since Saddam invaded Kuwait in August 1990.

The BoE announced another hike in its policy rate with the belated aim of getting inflation “before it gets even worse.”

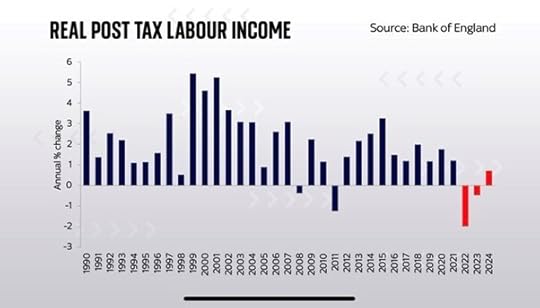

Of course, inflation rates are rising in all the major economies, driven partly by increased consumer demand, but mostly by supply chain bottlenecks, particularly in fossil fuel energy and food commodities. But the British inflation rate is considerably higher than even in the US or the Eurozone and the hit to living standards of the average British household is going to be much greater. The BoE admits that real post tax household income will fall by 2% in 2022, with a further fall in 2023.

This is five times worse than the fall in income that in the financial crisis of 2008-9, worse than the Black Wednesday of 1992 when the British pound broke with tracking the ECU (pre-euro currency). Indeed, this is the biggest fall in disposable income on record. And remember this is after a strangulation of real household incomes for nearly 30 years in the UK – the longest wage squeeze in 200 years!

Ben Broadbent, one of the BoE deputy governors, said that “extraordinary” rises in global energy prices are a key factor beyond the Bank’s control, with even bigger increases than during the oil price shock 50 years ago. He said: “I think this represents the steepest rise in energy costs for households as a share of income in a year than we have seen ever, including the 1970s.”

Energy bills to British households are capped in the UK by a regulation authority, as in many countries. However, because of the rise in global energy prices, the authority is raising the cap by 50% from April.

The government has panicked and is introducing a price rebate or discount to reduce the bill. But this is no handout. Instead, it is only a loan to reduce energy bills and will be clawed back in higher bills “when energy prices are lower”. The government wants to maintain the profits of the privatised energy monopolies rather than bring them under public control and is not putting public funds into providing energy to people at reasonable cost. So much for targeted price controls as a solution to inflation, as advocated by some on the left.

Price controls don’t work. But the authorities still expect wages to be controlled. BoE governor Bailey said that while it would be “painful” for workers to accept that prices would rise faster than their wages, he added that some “moderation of wage rises” was needed to prevent inflation becoming entrenched. “In the sense of saying, we do need to see a moderation of wage rises, now that’s painful. I don’t want to in any sense sugar that, it is painful. But we need to see that in order to get through this problem more quickly,” he added. So, with inflation rocketing, energy and food prices spiralling, the Bank of England tells British workers not to ask for more wages. This advice comes from a Bank governor who gets £575,538 including pension a year, more than 18 times higher than the median annual pay for full-time employees in Britain of £31,285.

The BoE claims that if workers ask for more wages, firms will be forced to raise prices and then there is a ‘wage-price’ spiral. There are two points here. Workers have not caused this price inflation – an important fact when mainstream economists (particularly Keynesians) argue that inflation is caused by ‘tight’ labour markets and ‘wage-cost push’. Second, there is no evidence that rising wages lead to price rises – indeed, there is much more evidence (as I have shown in previous posts) that it generally leads to falling profit share. And that is what really worries the government and the BoE – the profitability of British capital.

That is already weak enough.

World Penn Tables 10.0

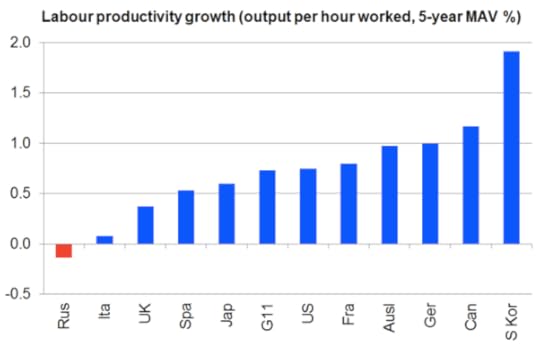

World Penn Tables 10.0And this low profitability leads to very poor productive investment and productivity growth.

Conference Board

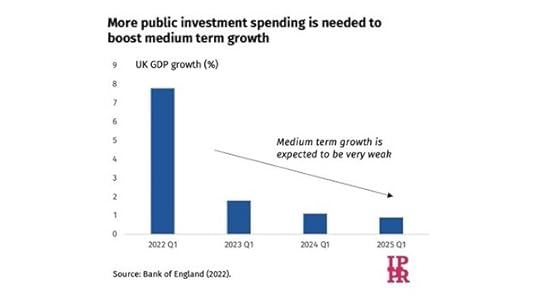

Conference BoardThe government boasts that the British economy is recovering fast from the disastrous pandemic slump. But this is nonsense. Inflation rates may eventually subside in the UK and the major economies – mainly because economic growth will slow fast. But Britain is in the worst position relative to other G7 economies. The UK is second from the bottom of the G7 league table when comparing the overall recovery from Covid with the pre-pandemic GDP level. And now the BoE has reduced its economic forecast significantly, saying that UK economic growth would soon “slow to subdued rates” of around only 1 per cent a year, lower than any other G7 economy.

Worse, the current UK growth rate is artificially boosted by £25bn of corporate tax incentives this year and next, but investment remains weak. In the third quarter of 2021, it was still 4 per cent below pre-pandemic levels, again lower than any other economy in the G7. And the government plans to raise corporation tax rates from 19 per cent to 25 per cent in 2023. The IMF reckons the UK economy will slide to near stagnation in 2023 (one year before the next election), with GDP only 0.5 per cent larger than at the start of the pandemic, the lowest in the G7. That’s not a great scenario for another Conservative election victory in 2024.

January 31, 2022

Portugal: Socialists on their own

Portugal’s ruling socialists under prime minister, António Costa, achieved a surprising victory in parliamentary elections on Sunday. The Socialists gained an outright majority in the new parliament over all other parties and will be able to rule without a coalition. The previous so-called gerigonca (contraption) coalition broke down last October when the leftist parties (Communists and Left Bloc) left the coalition over what they saw as an austerity budget being proposed by the Socialists.

Costa called a snap election expecting to have to form a new coalition. However, the Socialists took 41.7% of those Portuguese who voted, up 5.4% pts from the 2019 election, while the Leftist parties lost 6.9% pts. So the total left vote share actually dropped from 52.3% to 50.6%. The main right-wing party, PSD, did better too, rising from a 27.8% share to 29.3%. But the small ‘centre-right’ parties lost ground, so the Socialist victory was secured.

In effect, there was a consolidation towards the main traditional left and right parties. Except for one thing: there was a sharp rise in the far-right Chega (Enough!) party, which took 7.2% of the vote to become the third largest party in parliament. That’s a sign of things to come if the Socialists cannot deliver on improving living conditions and prospects for the Portuguese people, the poorest in Western Europe.

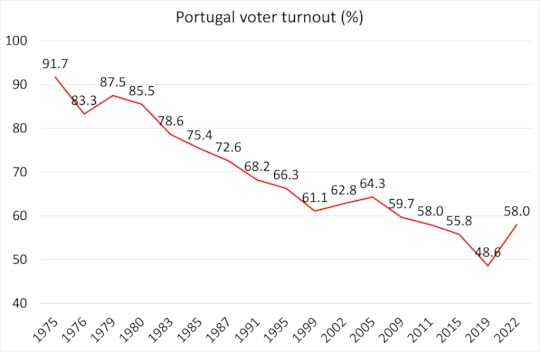

Voter turnout has been steadily falling since the first democratic election in 1975 after the revolution to overthrow the military dictatorship under Salazar. Then the turnout was 91.7%. In the 2019 election it had fallen to just 48.6%. Sunday’s turnout jumped to 58.0%, the best since 2009. Even so, the ‘no vote’ share of 42% easily outstripped those who voted Socialist (one in five) by some way. Disillusionment in parliamentary democracy remains.

The previous coalition government had supposedly done better than most in response to the pandemic, with one of the highest vaccination rates; but the death rate was still high and only kept within bounds because the Portuguese people showed great solidarity in following restrictions to protect health.

The pandemic was a disaster for an already weak Portuguese economy. Portugal has been called ‘sardine capitalism’ after its famous connection to the production of that fish. But this is misleading: agriculture and fisheries contributes less than 2% of annual GDP and only thousands in employment. Much more important in an economy where manufacturing output and investment is relatively low is tourism. Like Greece, tourism contributes a massive 20% to annual GDP and that has been decimated by the pandemic slump. Portugal’s economy is still well below the trend level before pre-pandemic.

https://www.oecd.org/economy/weekly-tracker-of-gdp-growth/

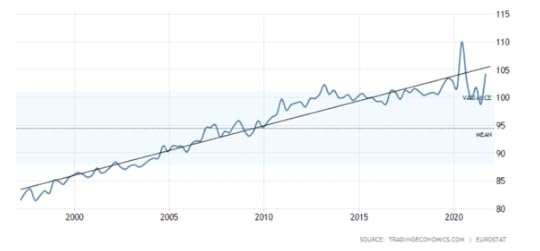

https://www.oecd.org/economy/weekly-tracker-of-gdp-growth/The Costa government came to power pledged to reverse the post 2008 slump austerity policies imposed by the Eurozone. Like other governments in southern Europe in the last decade, it made little progress on growth, productivity and investment, even if it avoided even worse austerity measures. Productivity has been flat for the last eight years.

Productivity level (index = 100)

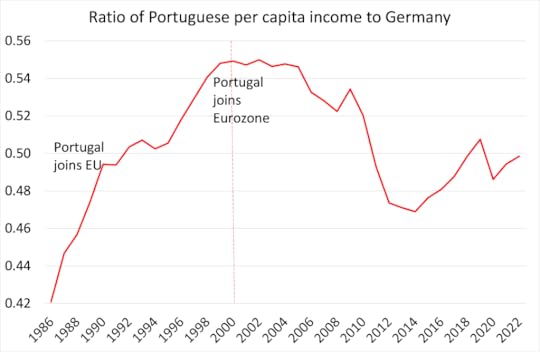

Portugal’s economy has been falling behind the rest of the EU since 2000, when its real annual GDP per capita was 16,230 euros (18,300 US dollars) compared with an EU average of 22,460 (25,330 US dollars). By 2020, Portugal had edged higher to 17,070 euros (19,250 US dollars) while the bloc’s average surged to 26,380 euros (29,750 US dollars).

IMF WEO database

IMF WEO databaseThe European Union supposedly aimed to ‘level up’ the weaker capitalist economies with the richer core. The opening of trade and investment after Portugal became a member in 1986 appeared to work, as it did for other weaker EU countries. But the introduction of the euro changed all that. Whereas before the weaker EU countries could let their currencies depreciate against the deutschemark to try and remain competitive. That was no longer an option in the Eurozone. Without higher investment and productivity, the weaker capitalist members could not compete. Convergence turned into divergence. Portugal like other weaker members was reliant on FDI from Germany and France. External debt rose sharply and the Euro debt crisis in 2012 in the wake of the global financial crash pushed the country into penury and austerity.

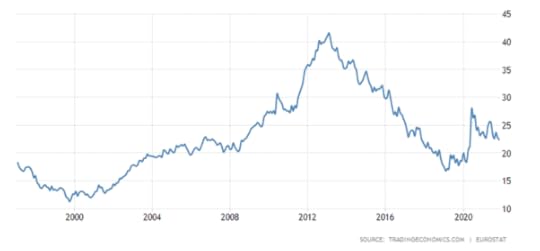

Meanwhile low wages and high unemployment spurred emigration – a feature really since the 1960s. Over the past ten years – a period that includes governments run by both the Socialists and the ‘centre-right’ Social Democrats – some 20,000 Portuguese nurses have gone to work abroad, in an unprecedented drain of medical talent. The youth unemployment rate is still 25%.

Youth unemployment rate (%)

Average pay is just 1,300 euros (1,466 US dollars) a month. Among all OECD countries, Portugal has the sixth-lowest average salary but the highest rise in housing prices. Portugal saw the lowest public investment across the European Union in 2020 and 2021. That was part of the reason the leftist parties pulled out of the coalition.

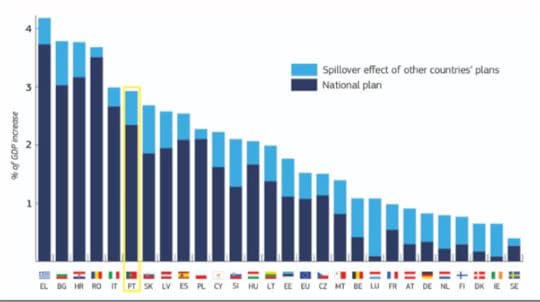

The Socialist government now takes full responsibility for improving conditions for the 99% in Portugal. It is putting all its hopes in the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Plan, which pools funds from the richer members to help out the weaker economies – the first time such a fiscal package has been employed across the EU. The government reckons that the European pandemic recovery plan will have an economic impact of E22 billion ($25 billion) through 2025, and as a result Portugal’s GDP in 2025 will be 3% higher than it would be without that plan.

EU Plan impact

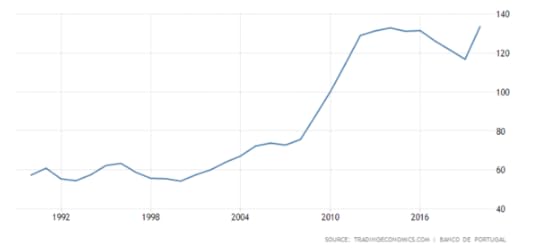

That’s the hope. But the money still comes with strings: namely that the government is supposed to maintain a tight fiscal policy and keep budget deficits down and above all start to reduce its huge public debt ratio.

Public debt to GDP (%)

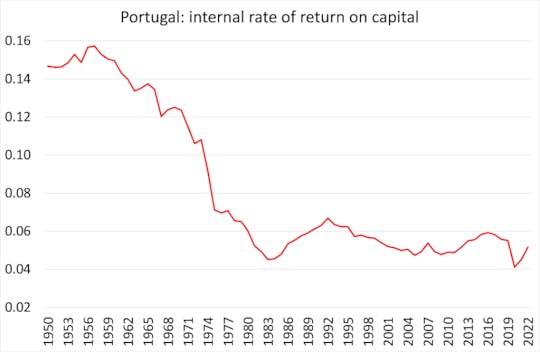

Even though the Socialist government will be getting funds from the EU to spend on infrastructure and services, it is likely to do little to get a very weak capitalist sector to invest and expand employment and raise wages. That’s because the profitability of capital in Portugal is miserable. It has been flat and low for 40 years. The EU has done nothing for Portuguese capital up to now.

Penn World Table 10.0 IRR series

Penn World Table 10.0 IRR seriesPortugal is a tiny country with just 10m population and a $200bn economy. Under capitalism, it is subject to the ‘kindness’ or otherwise of ‘strangers’ (ie German and French capital). And the new Socialist government has no intention of changing that.

January 22, 2022

A world rate of profit: important new evidence

Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (LTRPF) has either been heavily criticised or ignored as being an irrelevant explanation of crises under capitalism, both theoretically and empirically. The critics are not from mainstream economics, who generally ignore the role of profit in crises altogether. They partly come from post-Keynesian economists who look to ‘aggregate demand’ as the driver of capitalist economies, not profit. But the biggest sceptics come from Marxian economists.

Even though Marx considered the LTRPF as ‘the most important law of political economy’ (Grundrisse) and the underlying cause of recurrent cycles of crises (Capital Volume 3 Chapter 13), the sceptics argue that Marx’s LTRPF is illogical and ‘indeterminate’ as a theory (Michael Heinrich). And the empirical support for the law is non-existent or impossible to ascertain. Instead, we must look elsewhere for a theory of crisis either by turning to Keynes or amalgamating various eclectic theories like ‘overproduction’ or ‘underconsumption’ or ‘financialisation’ – or just accepting that there is no Marxist theory of crises. In my view, these critics have been answered effectively by several authors, including myself.

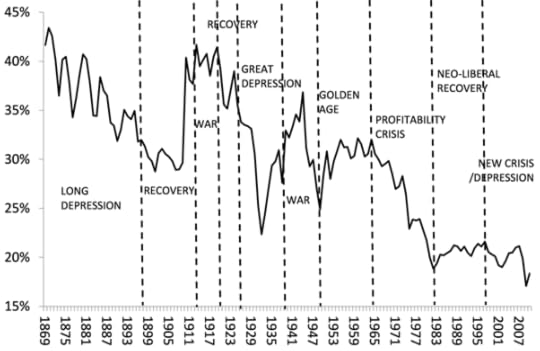

But let’s leave aside the logical validity of the law and consider here just the empirical evidence to support Marx’s formula for the rate of profit on capital in an economy is s/C+v, when s = surplus value; C= stock of fixed and circulating means of production and v = value of labour power (wage costs). Marx’s two key points on the LTRPF are 1) there will be a long-term secular decline in the average rate of profit on capital stock as capitalism develops and 2) the balance of tendential and counter-tendential factors in the law explains the regular booms and slumps in capitalist production.

Thanks to better data and also determined work by various Marxist economists too numerous to name all here, perhaps starting with Shane Mage back in 1963, there is now overwhelming empirical evidence to back Marx’s law. To begin with, this evidence was exclusively confined to US data, which was the most comprehensive. However, in the first decade of the 21st century some Marxist economists began to compile evidence to calculate a world rate of profit. As I argued in my own first attempt to calculate a world rate of profit, this was necessary because capitalism is a ‘closed economy’ at a global level and capitalism had spread its tentacles to all parts of the world through the 20th century. So to find better empirical support for the law required calculating a world rate.

As early as 2007, Minqi et al made the first attempt that I know of to calculate the world rate of profit, followed by David Zachariah in 2010. My first crude attempt was in 2012 (which I revised in 2017). Then came along a much more comprehensive calculation going back to 1855 for 14 countries by Esteban Maito (2014). Some Marxist economists were vehement in their scepticism in calculating a world rate of profit (Gerard Dumenil). But some of us did not desist. Given new data from the Penn World Tables 10.0 database available for the components of the law (s/C+v) going back to 1950 for economies, I made a much better calculation in 2020.

But now Marxist economists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst led by Deepankur Basu have delivered new evidence using data compiled by Brazilian Marxist economist Adalmir Marquetti. Marquetti has expanded and modified the Penn World Tables developed by the Groningen Growth and Development Centre into what he calls the Extended Penn World Tables (EPWT). The EPWT was first developed by Marquetti back in 2004 and I have used that database since then for my world rate of profit calculations. But now Marquetti has issued an updated series EPWT 7.0. And this series can be used to calculate a world rate of profit-based a large number of countries going back to 1960.

Basu et al use the new EPWT data to construct a world rate of profit as a weighted average of country-level profit rates, where a country’s share in the world capital stock is used as the weighting. Of course, this world rate is only an approximate world average. A proper world average would involve aggregating all the s, C and v in the world. Basu et al make the point that it is incorrect to aggregate country-level profit rates using the gross domestic product (GDP) as weights. So previous studies like Maito’s and mine have used an incorrect weighting scheme when country capital stock should be used. I agree and in my latest version of the world rate of profit I went further and aggregated the s, the C and the v for the G20 countries using the Penn World Tables 10.0 going to back to 1950. So no country weighting was necessary.

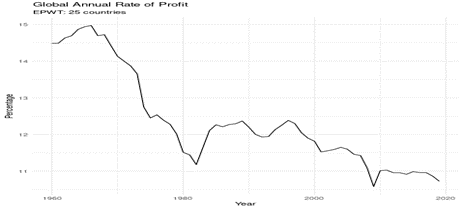

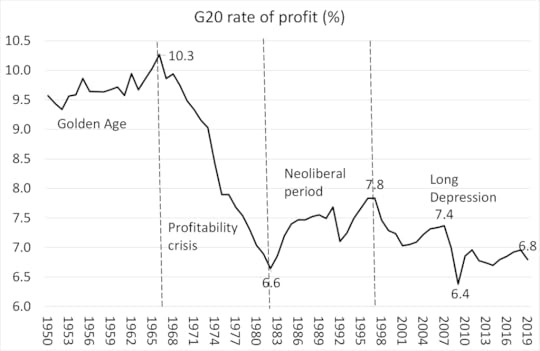

So much for method. Let’s look at Basu et al’s results. They are compelling in support of Marx’s law. Here is the key graphic using all the countries with data going back to 1960.

Basu et al conclude that: “The country-aggregated world profit rate series displays a strong negative linear trend for the period 1960-1980 and a weaker negative linear trend from 1980 to 2019. A medium run decomposition analysis reveals that the decline in the world profit rate is driven by a decline in the output-capital ratio. The industry-aggregated world profit rate shows a negative linear trend for the period 2000-2014, which, once again, is driven by a fall in the output-capital ratio.”

So Marx’s law is emphatically vindicated empirically at a world level. On the Amherst figures there has been a secular decline in the world rate of profit over the last 80 years of -25%, starting with the huge profitability crisis from 1966, leading to the major global slump of 1980-82. That was followed by the so-called ‘neoliberal’ revival in profitability up to 1996 (+11%). After that, the world economy entered what I have called ‘a long depression’ when profitability slipped back, turning up briefly in the credit boom of the 2000s until 2004, before slipping again into the Great Recession of 2008-9. Since then, the world rate of profit has stagnated and was near its all-time low in 2019, before the global pandemic slump of 2020. Each post-war global slump has revived profitability, but not for long.

How does the Basu calculation compare with my own made in 2020? Bearing in mind that my last calculation was only for the top 19 economies in the world (the EU is a separate G20 member) and my method of calculation is somewhat different, my results show a striking similarity. There is the same secular decline and the same turning points. Perhaps this is not too surprising as both Basu et al and I are using the same underlying database.

Marx’s LTRPF argues that the rate of profit will fall if the organic composition of capital (OCC) rises faster than the rate of surplus value or exploitation of labour. That is the underlying reason for the fall. Basu et al have decomposed the components of the world rate of profit to ascertain whether that is correct. They find that the world rate of profit declined at a rate of about 0.5% a year from 1960 to 2019, while the output-capital ratio declined by 0.8% a year (this is a reciprocal proxy for the OCC), and the profit share (a proxy for rate of surplus value) rose about 0.25% a year. So this supports Marx’s law that the OCC will outstrip the rate of exploitation of labour most of the time and so lead to a fall in the rate of profit. I found a similar result in my 2020 paper.

Ahmet Tonak, the world’s greatest Marxist expert on national accounts, had some concerns on using the Penn Tables as the raw data source for calculation because it does not distinguish between productive (value creating) labour and unproductive (value using) labour in an economy. And that can lead to diverging results on the rate of profit in national economies – which he found for Turkey.

We can go some way to dealing with this possible divergence by considering the rate of profit in the non-financial, non-residential property sectors of an economy. It does not solve the problem of delineating unproductive and productive labour within a sector, but it does provide some greater precision. For more on this issue, see the excellent work by Tsoulifis and Paitaridis.

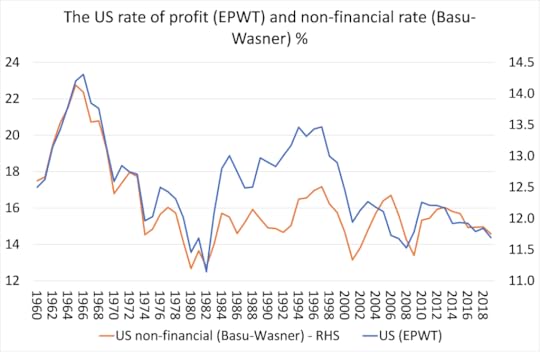

Basu and Wasner have also produced a profitability dashboard for the rate of profit in the US which distinguishes non-financial corporate profitability from corporate profitability. I compared the Basu et al (global) results for the US rate of profit against their results for the US non-financial corporate rate of profit. Both series follow the same trend and turning points so the divergence at this level is not a significant problem.

However, during the neo-liberal period, the US rate of profit based on the global data (which does not distinguish productive and unproductive sectors) rises much more than the rate of profit on just the non-financial sector using the Basu-Wasner calculations. That suggests that the neo-liberal recovery in profitability was mostly based on a switch into the financial sector by capital – another explanation for the fall in productive investment exhibited in the US in that period.

In sum, the Basu et al study has added yet more empirical evidence in support of Marx’s law on a world level. The evidence is overwhelming and yet the sceptics continue to ignore it and deny its relevance. The sceptics of Marx’s law of profitability are increasingly becoming like the climate change sceptics.

The profitability dashboard for the US economy can be found here https://dbasu.shinyapps.io/Profitability/ and the dashboard for the world rate and various countries can be found here. https://dbasu.shinyapps.io/World-Profitability/

January 14, 2022

ASSA 2022: part two – the heterodox

In this second post on the annual ASSA economics conference, I look at the papers and presentations made by radical and heterodox economists. These presentations are mostly under the auspices of the Union of Radical Political Economics (URPE) sessions, but the Association of Evolutionary Economics also provided an umbrella for some sessions.

The mainstream was focused on whether the US and world economy were set to recover strongly or not after COVID; whether the hike in inflation would eventually subside or not and what to do about it. The heterodox sessions were more focused, as you would expect, on the fault-lines in modern capitalist economies and why inequality of wealth and income has risen.

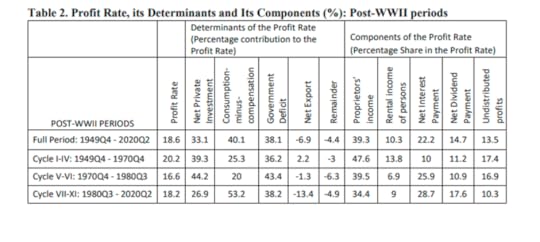

Interestingly, this year most heterodox presentations came from the post-Keynesian framework and not from Marxist political economy. The most interesting paper came from Al Campbell of Utah University and Erdogan Bakir of Bucknell University. Bakir looked at the dynamics of US recessions since 1945 through the prism of the Kaleckian profit model (Bakir and Campbell (AFEE 2022).pdf )

Now I have discussed the difference between the profit models of Kalecki and Marx on many occasions on my blog. Bakir and Campbell’s paper outlines the macro identities in the Kalecki model. But put simply, both aggregate models can be reduced to this simple formula:

Profit = Investment + Capitalist Consumption

But this an identity: total profit must match total spending by capitalists (investing and consuming) by definition. It is assumed that workers spend and do not save their wages. As Kalecki put it: ‘workers spend all they earn, while capitalists earn all they spend’.

This sums up the difference with Marx. Kalecki argues the direction of causation in the identity is from investment to profit, while Marx argues that the direction of causation is from profit to investment. Kalecki starts with investment as given and capitalists invest to ‘realise’ profits. Marx starts with profits as given and capitalists invest or consume those profits. Kalecki in true Keynesian style reckons capitalist economies are driven by aggregate demand and capitalist investment is part of that demand, so profits are merely the ‘residual’ or result of investment. In contrast, Marx reckons capitalist economies are driven by profit, which comes from the exploitation of labour power, providing the profits for investment. Kalecki removes any semblance of Marx’s law of value and exploitation from his model; for Marx it is paramount.

In my view, this makes a fundamental difference because the Marxist theory of crises under capitalism depends on what is happening to profit, in particular, the rate of profit. For Marx, crises are caused by a lack of surplus value extracted from labour; for Kalecki, they are caused by a lack of demand for investment goods from capitalists and consumer goods from workers.

But it is still the case that the macro identity of both models is the same. The Bakir-Campbell paper starts from there and “analyzes the components of the Kaleckian profit, as distinct from its determinants.” Using US national income accounts Bakir and Campbell delineate how much goes to different sectors of the capitalist class ie how much to bankers, shareholders and to capitalists and in interest, dividends and capitalist consumption.

Table 2 from their paper shows that the share of the proprietor’s income in profit was, on average, 47.6% during the Golden Age (I-IV) and dropped to 34.4% under the period of neoliberalism (VII-XI). The share of undistributed profits also dropped rather substantially from 17.4% during the Golden Age to 10.3% in the neoliberal period. The share of rental income also declined from 13.8% to 9% between these two periods. The share of net interest payments and net dividend payments in profit, however, increased substantially in the neoliberal period compared to the Golden Age: from 10% to 28.7% for net interest payments and 11.2% to 17.6% for net dividend payment. “The data confirm that neoliberalism has involved a substantial redistribution of income from enterprises to rentiers and shareholders. To the extent that this redistribution reduces the savings of enterprises, it discourages investment.”

In other words, there is good evidence that capitalists switched more of their profits out of productive investment to make more profits from financial speculation in the neoliberal period. This explains the decline in productive investment growth and the expansion of finance. Unfortunately, using the Kalecki model, Bakir-Campbell hide the Marxist cause for this switch; namely a falling rate of profit in productive sectors. But as they say, the determinants of profitability was not the purpose of the paper.

In another paper by Bakir and Campbell, the authors consider the role of increased debt in promoting and supporting that increased rate of profit. In this presentation, Al Campbell argued that finance was not a parasite on the productive sector as economists like Michael Hudson argue; it was worse than that! That’s because it slows productive accumulation. If it were just parasitic, why did the strategists of capital let debt in all its forms expand during the neo-liberal period? Neoliberalism cannot be reduced to so-called ‘financialisation’; neoliberalism had many different features, all aimed at raising profitability at which increasing credit/debt play an important role, but at the expense of productive investment. So it is a reformist illusion that capitalism can return to the Golden Age of fast growth in investment and production by controlling or curbing debt.

Another theme in several papers on the slowing pace of investment and productivity in modern capitalist economies was the Keynes-Kalecki view that it was due to the reduction in labour’s share of national income, so that aggregate demand growth slowed. Thomas Michl of Colgate University reckoned that the wage share regulates labor-saving technical change and employment regulates its capital using bias. So secular stagnation under neoliberal capitalism has been driven by a combination of diminished investment and reduced worker bargaining power more than by slower technical change and population growth. This increases the profit share and so reduces the rates of technical change, capital accumulation, and population growth. Again, this is a theory that is the opposite of Marx’s.

Similarly, Carlos Aguiar de Medeiros and Nicholas Trebat argue, ‘based on classical political economy and the power resources approach’ that “the key factor behind the increasing wage and income inequality of this period was the decline in workers’ bargaining power., rather than globalization or technical change. It is surely correct that the demolition of trade union power in the neoliberal period had an important effect on reducing labour’s share in national incomes. But it does not follow that reduced labour share was the cause of crises in capitalist production post-1980 as post-Keynesians argue when they refer to ‘wage-led economies’.

Another variant of this post-Keynesian analysis of capitalist crises was presented by John Komlos of Munich University. Starting from accepting Keynes’ view that “I think that capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight.”, Komlos reckoned that the pandemic slump was so severe because the capitalist economy was already fragile. So it took just a ‘black swan’ event like the pandemic to tip it over. The idea of black swans, or ‘unknown unknowns’ on the extreme of the probability spectrum was offered as an explanation of the Great Recession by some back in 2008-9 following the view of financial analyst Nassim Taleb that chance rules. At that time I argued that the black swan explanation of slumps (ie chance) could not explain regular and recurring crises (each time were they by chance?).

But what to do about avoiding or ameliorating slumps under capitalism. A very popular policy alternative has been taken up in heterodox circles, namely more government spending and even permanent budget deficits financed by money creation as per Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). MMT found some support in the heterodox sessions. Devin Rafferty of St Peters University reckoned that the heterodox economist Karl Polanyi and MMT would agree on the process by which money is created as well as on the mechanisms that regulate its value. Polanyi would have embraced the MMT policy measures of a ‘job guarantee’ and ‘functional finance’ —the two staples of the MMT approach–which he believed would foster international peace, national liberty, and individual freedom. I think this tells us something about Polanyi’s form of Marxism and MMT.

Much more critical of MMT was Brian Lin of National Chenghi University. Lin argued that public investment by state enterprises would much more effective in avoiding slumps than MMT. State investment “is more a timely creation of advanced institutions for sustaining worldwide economies than a politico-economic phenomenon like the MMT”. It would be far better for a country to adopt a decisive policy of nationalizing private companies with financial difficulties instead of issuing more money for the unemployed. Lin’s view came in for heavy criticism by some attendees who reckoned state companies were bureaucratic and inefficient compared to the private sector and could not be relied on. Lin did not respond with the Chinese model as the success story for public investment but, of all countries, state enterprises in Sweden!

However, when it came to investment solutions for so-called Global South, the idea of expanding public development banks was supported. Gaëlle Despierre Corporon of the University of Grenoble reckoned such institutions “can give a positive impulse to the global relations between the South and the North and become dynamic institutions able to provide new perspectives for long-term development financing and ensure the coherence of the global system.” So apparently, the public sector can work globally but not nationally.

That brings us to the rising global inequality of wealth and income – an important subject, ignored at this year’s ASSA by the mainstream, but taken up in a paper by Victor Manuel Isidro Luna of the University of the Sea. He pointed out that the majority of the countries of the world are not catching up consistently with the affluent countries. So ‘between country’ inequality has surged. In particular, between the richer and poorer Latin countries, there remains “an unbridgeable gulf”. The poorer countries globally were handicapped by a reliance on short-term foreign portfolio investment and longer term by FDI which were controlled by the richer countries. This left poorer countries in the grip of the richer. So open markets cannot be the development model for the poorer countries.

‘Within country’ inequality was also discussed in some sessions. Some Norwegian economists reckoned that labour income is the most important determinant of wealth, except among the top 1%, where capital income and capital gains on financial assets were more important – pretty much as you would expect in a capitalist economy. Alicia Girón on UNAM Mexico also confirmed that the recent rise in inequality is associated with rising asset valuation as opposed to capital accumulation both globally and within countries and is not driven by potentially spurious factors such as demographic changes and growth. In other words, for the top 1% gain mostly from rising property and financial asset prices.

One of the major new financial assets for the rich has been the emergence of crypto currencies. Using the Marxist conceptualization of money, Juan Huato of St Francis College argued that the buyers of crypto currencies were not getting some great decentralised money asset but still dependent on the state “which they imagine to have escaped.” Edemilson Parana of the Federal University of Ceara reckoned that Bitcoin would be unable to establish itself as an alternative to the current monetary system as it does not meet elementary requirements of money. Despite its declared search for a substitution of world money, for monetary stability against the supposedly ‘inflationary’ state money and for ‘depoliticization’, decentralization and deconcentration of monetary power, what is empirically observed is precisely the opposite: low volume and range of circulation, great instability against state money, transactional (economic, ecological etc.) inefficiency and greater relative concentration of political and economic power among its users. In the end, the non-fulfilment of the radical neoliberal aspirations of Bitcoin shows that the attempt by its creators and enthusiasts of emptying money of its social content, i.e., to ‘neutralize’ it, in capitalism, is not feasible.

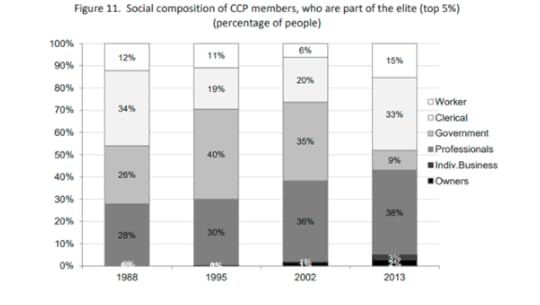

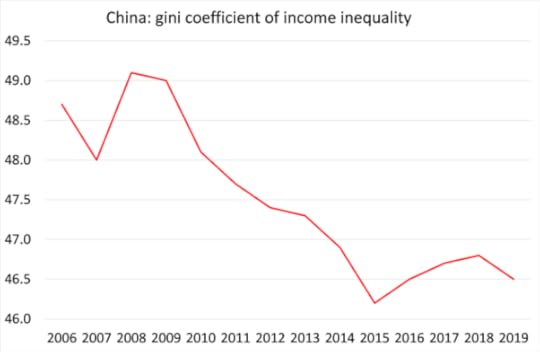

Finally, there was the elephant in the room – China. Surprisingly, there was not much on China in the heterodox sessions except on the inequality of income. To be more exact, in one study it was found that China’s ‘global middle class’ (ie equivalent in income to Europe’s middle class) had grown very rapidly, from 2% of the population in 2007 to 14% in 2013, and further to 25% of the population in 2018. This middle class was predominately urban, largely resides in China’s eastern region, and mainly depends on wage employment for income. A distinct ‘business’ middle class exists, but is relatively small.

Financialisation in the advanced capitalist economies through the Kalecki paradigm, doubts about MMT and cryptocurrencies, studies on rising inequality – these were themes of heterodox sessions.

January 12, 2022

ASSA 2022: part one – the mainstream

The annual conference of the American Economics Association (ASSA 2022) took place last weekend. This year it was a virtual conference, but there was still a myriad of presentations and sessions in the largest academic economics conference in the world, with many of the big hitters of mainstream economics on the webinars.

I usually divide the conference sessions into two sections; first, the sessions based on the paradigms of mainstream economics ie. neoclassical, marginalist general equilibrium models; and second, the sessions based on radical heterodox economics (post-Keynesians, institutionalists and even Marxist models). The former sessions are multi-fold and well attended; the latter, usually run by the Union of Radical Political Economics (URPE) are small and poorly attended. But of course, the latter usually provide the richest addition to our understanding of political economy.

This year’s mainstream sessions were naturally dominated by what is happening and going to happen to the US economy, the world economy and the Global South as economies recover from the COVID pandemic. Surprisingly, in one session former OECD chief economist, Catherine Mann was decidedly pessimistic about the long-term future of the US economy. She saw the US as a chronically a low investment and low productivity economy with high inequality and with little prospect of post-COVID of becoming one that is more equal and characterized by higher investment, strong labour markets and better productivity. “What if the boom from policy choices does not catalyze sustained private sector activity, will inflation spiral? If so, policies will need to retrench, leading to a bust.”, she warned.

Mann asked herself the question, how do we get investment up? Apparently, in surveys, more CEOs of major companies expect a continuance of low annual economic growth of 1.5-2.0% rather than more optimistic official expectations of 4%-plus. And forecasts for increasing investment would only take capex levels back to that of 2019. US companies are hoarding up to $3.17trn in cash and preparing to buy back even more of their own shares, while doubling mergers, rather than invest productively. More mergers would reduce the very competition necessary for innovation in capitalist economies. So Mann reckoned that US economic growth during the rest of the 2020s would be even lower than in the decade before (which I have called the Long Depression).

In contrast, it was liberal left economist Joseph Stiglitz who sounded a note of optimism. Lauding the boost to the US economy made by Bidenonomics ie fiscal spending on infrastructure, Stiglitz saw post-COVID as a possible “turning point for the US economy” to get out its rut of low growth before COVID. Stiglitz reckoned there were clear signs of a change in government economic policy towards Keynesian macro-management and also more action to reduce the huge rise in inequality of wealth and income over the last 40 years. His evidence for this optimistic turning point was scant compared to the harsh reality of the data presented by Mann.

Neoclassical anti-Keynesian John Taylor had no time for Stiglitz’s optimistic view of Bidenomics, arguing the limitations of fiscal spending. His econometric models, Taylor said, showed increased economic growth after the pandemic would depend more on ‘structural policies’—reducing taxes, regulation, and liberalising financial markets and trade –rather than on Keynesian counter cyclical policies. Indeed, in another session, in a similar vein, economists argued that capacity to increase fiscal deficits was limited. The real way to avoid spiralling public sector debt from permanent budget deficits was to increase real GDP growth but if that stays low then budget surpluses will be required i.e fiscal austerity to stabilise runaway debt. The Austerians were alive and well at this year’s ASSA.

Finally, Larry Summers, former Treasury secretary under Clinton and another Keynesian guru, summed up the confusion among the mainstream American economists, by arguing while Bidenomics with increased fiscal boosts were “the boldest policy experiment of the last 40 years”, they “could lead to rapid growth, stagflation, or recession – each with more or less equal probability.” And as Jason Furman, the former economic adviser to Barack Obama, put it in another session, “it is impossible to work out when crises happen; as they could be just chance, like COVID was.” Well, that was helpful. What none mentioned was that the so-called fiscal boost by Biden was falling away anyway and would be reversed within a few years. So the ‘bold experiment’ was not really so bold, while deeper ‘structural measures’ were not on the agenda at all.

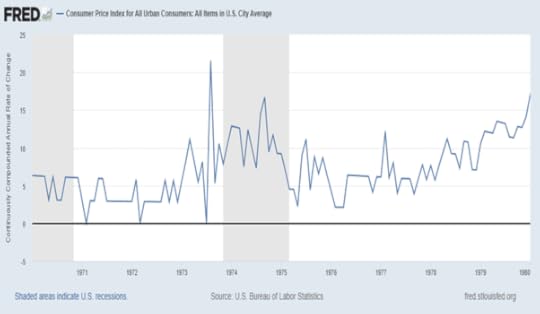

The immediate topical issue for mainstream macro economists at ASSA was rising inflation. With the US annual inflation rate hitting 6%-plus, the highest rate in 40 years, the question at debate was whether the US Fed should move quicker in its monetary policy to douse the flames with interest rate hikes and/or reductions in bond purchases during 2022. Depending on whether these economists thought rising inflation was the result of short-term supply bottlenecks or the result of excessive demand from low interest rates and fiscal boost, they took different sides on whether the Fed should speed up monetary ‘tightening’ or not.

The debate rolled on in various sessions – but interestingly, one thing was agreed, that rising inflation was not caused by wage rises. The data showed only modest wage rises and indeed less than price inflation, so real wages were falling. So it’s not the workers’ fault. The worry for the mainstream was that workers might react to price rises by trying to compensate through strikes etc to get higher wages. That would be disastrous for the profitability of capital and could return the US economy to the wage-price spiral of 1970s that led to ‘stagflation’ and eventually sharp rises in the cost of borrowing and a huge recession. So both the Keynesians and neoclassicals were agreed on avoiding ‘excessive’ wage rises.

But does monetary policy work anyway in controlling ‘aggregate demand’ and inflation. The evidence in boosting growth in the Great Depression of the 1930s was no – and even Keynes agreed back then. And the evidence of the last 30 years of slowing inflation below central bank targets suggests that monetary easing had little effect then. So the idea that tighter monetary policy will control inflation is very dubious. Nevertheless, some post-Keynesians apparently think that central bank policy rates can control interest rates across the economy and so control inflation.

While the mainstream was divided on whether the US economy was likely to recover on a faster footing or just sink back into the low growth depression pre-COVID, there was pretty much agreement on the weak prospects for the rest of the world, particularly in the Global South. Deficits will fall, but debt will rise. Current World Bank chief economist, Carmen Reinhart reminded attendees at another session that the pandemic slump had been truly global, with 90% of world’s nations in slump. Things were much worse than in the Great Recession of 2008-9 especially for emerging economies and even for China and India, two economies which avoided a major recession back then. Indeed, 60% of low-income economies, the poorest, are in ‘debt distress’ ie they cannot ‘service’ their debts.

In another session on emerging economies after COVID, leading international economist, Barry Eichengreen noted that “the relative dearth of bank failures and financial accidents speaks to stronger macro- and micro-prudential policies that will similarly serve emerging markets well going forward.” But debt has risen sharply and there is the interruption to schooling and human capital formation. So “changes in global supply chains and a faster pace of automation will make the traditional pathway to higher incomes more difficult for many middle-income countries.” Economist Franziska Ohnsorge did a study of the impact of deep recessions on potential growth. Recessions leave a legacy of lower potential growth four to five years after their onset. So the ‘scarring’ of economies has a lasting impact of recessions. She concluded that the pandemic “will steepen the already-expected slowdown in potential growth over the coming decade.”

But what about the longer-term for the advanced economies? Can the major capitalist economies turn round their low productivity growth rate and open up a new era of life? Again, in a session on the future of the world economy, Catherin Mann doubted it. As she put it: “Many people talk about ‘returning to normal’ after the pandemic finally is under control. We have to hope that the global economy does not return to the pre-pandemic ‘normal’. Productivity has been too low, inequality too high, globalization in retreat, and climate change unchecked.” She did not expect much change.

Again, in contrast, liberal left Joseph Stiglitz was more confident that productivity could rise because of better global agreements on cooperation (!). And other mainstream presenters argued that the pandemic slump had “accelerated the development and adoption of digital technology solutions in pursuit of business and economic continuity and resilience.” So “there is a reasonable chance that the post-pandemic global economy will experience a surge in productivity and growth, even as it moves into and through an energy transition in pursuit of sustainability.” Mary Amiti reckons that productivity ‘spillovers’ from innovating multinational enterprises can increase productivity in smaller firms in the same sector by about 10% after five years.

That optimism was not repeated by the leading economist studying the impact on productivity from the digital AI technologies. Daron Acemoglu reckoned that AI had so far had little impact on improving productivity in economies. Diffusion had not spread from tech sectors to other sectors or any boost in profits. His answer was that businesses should not just aim to make profits as their target but aim for better production! It seems that the great story of innovation out of COVID is still what veteran neoclassical economist Robert Solow (now 97 years old) famously said in 1987 about the computer age: “I see innovation everywhere, except in the statistics.”

There were two other big themes in the mainstream section of ASSA: climate change and carbon emissions; and China. The mainstream deals with global warming and climate change purely from the aspect of the market ie what should the carbon price be to encompass the ‘social costs’ of carbon emissions. Economists in the Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis session discussed the latest estimates for carbon market prices to mitigate carbon emissions. They all concluded that carbon pricing was still way too low in carbon markets that existed. Prices needed to be at least $100/t and that estimate had been rising all the time since such estimates were made.

Subsidies to renewables energy and other carbon mitigating technologies would not do the trick either, because they were too small and too targeted. A key factor in getting the price right was the discount rate used to reflect the costs to GDP now of pricing carbon emissions against the future. Gernot Wagner of New York University showed that the discount rate was set too high by most studies (4%), leading to an estimate of the social price of carbon emissions that was way too low. Half that rate was required and maybe lower.

And as for regulating fossil fuel output, that also was inadequate if not actually making things worse. US economist Ashley Langer reckoned that “regulated U.S. electricity markets have transitioned from coal to natural gas more slowly than restructured markets.” In the long-run, “utilities decide which plants to retire and in which new technologies to invest. So regulation slowed the energy transition from coal to natural gas.”

As for China, all the mainstream sessions appeared to be designed to show China as failing economically and conducting nefarious economic policies abroad, especially with other poorer countries. Panle Jia Barwick said that if the Chinese authorities deregulated firm entry into markets, productivity would rise across the board. ie more freedom for capitalist firms would benefit the economy. And Jun Pan reckoned that favourable credit terms to state enterprises by state banks meant that non-state firms were losing their long-standing advantage over SOEs in profitability and efficiency. Presumably, this was bad news.

But another study by Zheng Michael Song showed that those private companies that worked closely with state enterprises had increased the “aggregate output of the private sector by 1.5 to 2% a year between 2000 and 2019.” So the state sector was an essential positive factor for the capitalist sector. On a wider note, Meg Rithmire characterised China as ‘state capitalist’ but in a special sense, namely that a resurgent ‘party-state’ model has emerged, “motivated by a logic of political survival”, rather than the ‘familiar conceptualizations of state capitalism’.

On foreign policy and activity, China came in for a hammering by mainstream analysis. China’s loans and FDI outflows to other countries, mainly to the global South, have come under scrutiny in recent years. Carmen Reinhart noted that outflows are not just through state financial institutions but increasingly from China’s capitalist sector, which constituted the main channel for foreign portfolio investment outflows. Christoph Trebesch made a systematic analysis of the legal terms of China’s foreign lending through 100 contracts between Chinese state-owned entities and government borrowers in 24 developing countries in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Oceania, and compared them with those of other bilateral, multilateral, and commercial creditors. He concluded that the contracts showed China “as a muscular and commercially-savvy lender to the developing world.” Can this be bad?

Well, in another session, presenters claimed that China hid the amount of debt that borrowers had got themselves into. Apparently, 50% of China’s lending to developing countries is not reported to the IMF or the World Bank. “These “hidden debts” distort policy surveillance, risk pricing, and debt sustainability analyses.” But do they put the borrowing emerging economy states into a ‘debt trap’ any more than do the IMF and World Bank and other private sector lenders in the Global North? Actually, the evidence shows that China’s loans are much more manageable to service than the IMF’s. It’s just that emerging economies are so poor and already heavily in in debt, that debt distress has risen sharply during COVID.

My next post will cover the sessions of the heterodox and radical presentations.

January 6, 2022

Price controls: do they work?

“We have a powerful weapon to fight inflation: price controls. It’s time we consider it.” So said Isabelle Weber, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the author of How China Escaped Shock Therapy, writing in the UK Guardian newspaper. Weber’s piece was just 800 words long, but it provoked a squall of debate between radical post-Keynesian economists and more orthodox Keynesians over the effectiveness of price controls to control rising inflation of prices in general and to deal with the current inflation spike in the major economies.

Weber is author of the highly acclaimed book on the zigs and zags in the economic policy of the Communist leaders in China during the period of the country’s unprecedented economic rise. My review of her book can be found here. Weber comes from one of the more radical departments of economics in the US and is apparently a big fan of post-Keynesian authors like Minsky and Kalecki (but not it seems Marx). She also is a supporter of Modern Monetary Theory.

Inflation rates have been rising in most of the major economies to levels not seen since the 1970s. Some mainstream economists have been arguing this spike in inflation is due to excessive demand by consumers who have huge piles of money given to them by governments during COVID (ie ‘quantitative easing’) and by fiscal stimulus programmes designed to spark an economic recovery. Much of these measures have been financed increasingly by central bank credit injections, MMT style. The mainstream view is that it is time to rein in these monetary injections with interest rate hikes and by tapering off quantitative easing. Post-Keynesians and MMT promoters oppose this and want to continue with fiscal boosts and monetary easing. So Weber offers an alternative policy to tighter monetary measures and fiscal austerity (ie more taxes and less spending to control rising inflation). It is price controls.

In her piece, Weber likens the current inflation spiral to just after WW2. Then even mainstream economists advocated price controls. Weber argues that: “Price controls would buy time to deal with bottlenecks that will continue as long as the pandemic prevails.” She quotes the much-revered post-war Keynesian economist JK Galbraith: He explained that “the role of price controls” would be “strategic”. “No more than the economist ever supposed will it stop inflation,” he added. “But it both establishes the base and gains the time for the measures that do.” So just a short-term measure then. But Weber then adds that “Strategic price controls could also contribute to the monetary stability needed to mobilize public investments towards economic resilience, climate change mitigation and carbon-neutrality.” In other words, not a short-term measure after all, but a key policy that would control inflation indefinitely so that public investment financed by central banks a la MMT does not have to be curtailed.

Mainstream economists erupted nastily to Weber’s argument. Orthodox Keynesian guru Paul Krugman was particularly scathing. That’s because it is a law of neoclassical economics that governments cannot buck markets and if controls on market prices are imposed by government, that will lead to significant imbalances of ‘supply and demand’ ie either shortages of supply and even outright recession. Let the market rule prices because you cannot stop the sun rising in the east, or if you do, there will be permanent darkness.

On one level this dispute is misleading. That’s because in many sectors of capitalist economies, price controls are already in operation. There are rent controls; transport fare price increase caps, and price caps on utilities like gas, water and electricity in many countries. Price regulation on private ‘monopolies’ and state industries can be found everywhere.

But this is not what Weber means by ‘strategic price controls’. Instead, price controls are offered as a policy alternative to control inflation compared to monetary tightening and fiscal austerity as the mainstream advocates. But price controls to control rising or high inflation in capitalist economies will not work precisely because inflation is determined by the laws of motion in a capitalist economy that are more powerful and controls. Sure, price controls on drugs or transport fares can play a role for specific sectors where perhaps just a few companies dominate the price, but because such controls just cover a sector and not a whole economy, they won’t be effective overall. Targeted price controls may not distort overall supply and demand movements in an economy but for that reason, they have little effect on overall inflation of prices, which is being driven by other factors.

The historical evidence of overall price controls in a capitalist economy is that they either work at the expense of production by creating shortages or even provoking a recession. Take the 1971-4 price controls introduced under the Nixon presidency in the US. It is argued that they worked to control price rises for a while, but as soon as they were lifted in 1974, price inflation rose again. A paper by Blinder and Newton concluded that “According to the estimates, by February 1974 controls had lowered the non-food non-energy price level by 3-4 percent. After that point, and especially after controls ended in April 1974, a period of rapid ‘catch up’ inflation eroded the gains that had been achieved, leaving the price level from zero to 2 percent below what it would have been in the absence of controls. The dismantling of controls can thus account for most of the burst of ‘double digit’ inflation in non-food and non-energy prices during 1974.” Actually, during the period of price controls, inflation started to accelerate in 1973 as the US economy reached a peak of expansion alongside falling profitability and slowing investment growth. What lowered inflation in the end was the deep recession of 1974-5, not price controls.

Recently economists at the White House Council of Economic Advisors issued a paper suggesting that price controls could work just as they did after WW2. The White House economists reckon that “the inflationary period after World War II is likely a better comparison for the current economic situation than the 1970s and suggests that inflation could quickly decline once supply chains are fully online and pent-up demand levels off.” Yes, but exactly, if the ‘sugar rush’ of pent-up consumer demand falls back and supply bottlenecks are resolved, then inflation rates will probably subside. So how would price controls help at all?

Like the White House, Weber says controls could be used in the short-term to get a ‘breathing space’ on inflation; but she is really advocating controls as a necessary long-term policy alternative to fiscal and monetary restraint, which is not the same. That price controls are seen as a long-term, even permanent, policy by Weber and the post-Keynesians is revealed by the other big bugbear of post-Keynesianism after fiscal ‘austerity’, namely monopolies.

As Weber says, “a critical factor that is driving up prices remains largely overlooked: an explosion in profits. In 2021, US non-financial profit margins have reached levels not seen since the aftermath of the second world war. This is no coincidence…. Now large corporations with market power have used supply problems as an opportunity to increase prices and scoop windfall profits.” So, you see, rising inflation is the result of ‘price gouging’ by monopolies. We need price controls on monopoly pricing power.

But it’s just not true that rising profits (margins) lead to inflation. As a study by Joseph Politano finds : “The rise in corporate profits is largely attributable to this increase in spending: money first went from the government to households in aggregate, and now those households are spending money and sending it to corporations in aggregate. The jump in aggregate corporate profits is no more responsible for the rise in inflation than the prior jump in household income.” Politano adds: “there is no causal analysis here. One could just as easily repeat this exercise by ascribing all inflation to the increase in income caused by the stimulus checks, because without good causal inference the whole thing is just conjecture about what “actually” caused inflation”.

Indeed, we could also claim, as mainstream economists do, that wage rises cause rising inflation because companies have to raise prices to sustain profitability. But there is no causal or empirical validity for this. A dose of Marxist theory on inflation shows that prices are fundamentally set by the value of labour time going into commodities on average and not by the components of that value in profits and wages. If wages rise, then profits fall and vice versa, at least on average, not prices. And the major capitalist economies are not dominated by ‘monopolies’ that can jack up prices as they wish. If that were the case, inflation rates would be continually rising, whereas from the 1990s to pre-pandemic 2019, inflation rates in the major economies were falling!

Monopoly capital is a term that does not really describe modern capitalist economies, just as ‘competitive capital’ did not really describe 19th century capitalism. Most sectors in capitalist economies have a small group of ‘oligopolies’ and a large group of small companies. Depending on the various weights of these two groups, prices will be driven by ‘regulating capitals’ (see Shaikh Chapter 7), which are usually in fierce competition with each other, within countries and internationally. Monopoly profits are not the cause of movements in overall inflation rates; only in some sectors where ‘natural’ monopolies exist and even there, competition and technical change can undermine monopoly control of prices over time.

The White House and Weber argument that price controls during and just after WW2 worked is really misleading. Then governments were in full control of the major sectors of the economy in order to direct them to the war effort. A war economy with the major companies and financial institutions working to a plan is nothing like the free-for all for the capitalist sector in profits and investment as in the current pandemic. Total price control in an economy would require total control by the state of the oligopolies over investment and production. And total control would only be possible by taking the oligopolies into public ownership with a plan for investment and production.

So when Weber (and it seems MMT-guru Stephanie Kelton) cite the example of successful price controls in Communist China in its early years, they are comparing apples with pears. Price controls won’t work to get inflation down without causing a recession in an economy dominated by the capitalist mode of production. Squeezing profits across the board by such measures will only lead lower investment and production growth.

Weber ended her article with this: “We need a systematic consideration of strategic price controls as a tool in the broader policy response to the enormous macroeconomic challenges instead of pretending there is no alternative beyond wait-and-see or austerity.” Weber and Kelton and other post-Keynesians are raising price controls as an alternative to ‘austerity’ as advocated by the mainstream. And they are right to worry that ‘austerity’ is coming back. See this piece by Chicago economist, John Cochrane that blames inflation on excessive government spending.

Already even under ‘profligate’ Biden, the government is set to take more out of the economy than it is injecting into it. According to the Congressional Budget Office, federal government spending is set to decline by 7% on average up to 2026 compared with 2021 levels while tax revenues are expected to rise by 25%. The US federal budget deficit will be halved in 2022 and kept down for the following years. So no Keynesian-style fiscal stimulus is planned – on the contrary. The graph below shows that US fiscal policy is no longer stimulating aggregate demand.

In my view, price controls cannot be an alternative policy to fiscal austerity in controlling inflation when the causes of inflation lie in the laws of motion of capitalist accumulation ie. changes in profitability, investment and output, not in monopoly power or monetary injections? In my view, the current high inflation rates are likely to be ‘transitory’ because during 2022 growth in output, investment and productivity will probably start to drop back to ‘long depression’ rates. That will mean that inflation will also subside, although still be higher than pre-pandemic. Price controls will be ignored.

January 1, 2022

Forecast for 2022

At the beginning of each year, I make an attempt to forecast what will happen in the world economy for the year ahead. The point of making any forecast at all is often ridiculed. After all, surely there are just too many factors to feed into any economic forecast to get even close to what eventually happens. Moreover, mainstream economic forecasts have been notable in their failure. In particular, they never forecast a slump in production and investment even a year ahead. In my view, that shows an ideological commitment to the promotion of the capitalist mode of production. Although, it is a confirmed feature of capitalism that there are regular and recurring slumps in production, investment and employment, these slumps are never forecast by the mainstream or official agencies until they have happened.

That does not mean making a forecast is a waste of time, in my view. In scientific analysis, theory must have predictive power and that applies as well to economics if it is to be considered a science and not just an apology for capitalism. So if Marx’s theory of crises is to be validated, it must have some predictive power – namely that slumps in capitalist production will happen at regular recurring intervals, primarily due to changes in the rate of profit on capital and resulting movements in the mass of profits in a capitalist economy.

But as I have argued in previous posts, predictions and forecasts are different. From their models, climate scientists predict a dangerous rise in global temperatures; and virologists have also been predicting an increase in deadly pathogens reaching humans in a series of pandemics. But forecasting when exactly these predictions become reality is much more difficult. On the other hand, climatologists are not yet able to forecast well what the weather in a country is likely to be over a whole year, but their models are now pretty accurate for the weather over the next three days. So forecasts for output, investment, prices and employment one year ahead are not so impossible.

Anyway, let’s bite the bullet and make some forecasts for 2022. Last year’s forecast was relatively easy. It was clear that all the major economies were going to make a recovery from the slump of 2020. I wrote: “Real GDPs will grow, unemployment rates will start to decline and consumer spending will pick up.” With the rollout of vaccines, the “G7 economies should be recovering significantly by mid-year”. But I added that “this will be no V-shaped recovery, which means a return to previous levels of national output, employment and investment. By the end of 2021, most major economies (China excepted) will still have levels of output etc below that at the beginning of 2020.” These forecasts have been borne out.

There were two main reasons why I expected the economic recovery would not restore global output to 2019 levels by the end of 2021. First, there had been a significant ‘scarring’ of the major economies from the COVID pandemic in jobs, investment and productivity of labour that can never be recovered. This was exhibited in a huge rise in debt, both public sector and private, that weighs down on the major economies like the permanent damage of ‘long COVID’ on millions of people.

This ‘scarring’ was also exhibited in a fall in average profitability of capital in the major economies in 2020 to a new low, the revival of which in 2021 was not sufficient to restore profitability even to the level of 2019.

Nevertheless, as expected, global real GDP growth in 2021 was probably around 5%, after falling an unprecedented 3.5% in the 2020 slump. According to the IMF, in the advanced capitalist economies, real GDP per person fell 4.9% in 2020 but rose 5.0% in 2021. That meant real GDP per person in these economies was still slightly below the level reached at end-2019. So two years of scarring.

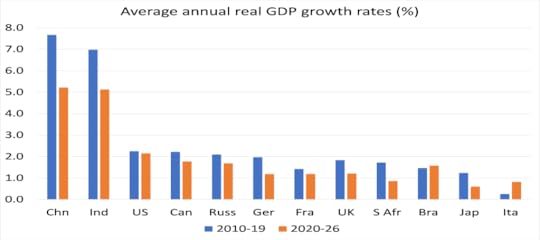

Most forecasts for this year, 2022, are more (or less) of the same as in 2021. The world economy is expected to grow around 3.5-4.0% in real terms – a significant slowing compared to 2021 (down 25% on the rate). Moreover, the advanced capitalist economies are forecast to grow at less than 4% in 2022 and at less than 2.5% in 2023.

Forecast for real GDP growth (%) by the Conference Board.