Michael Roberts's Blog, page 37

June 6, 2021

Peru: a crunch election

Today, 25m Peruvians vote in the second round of a crucial Presidential election. The voters are being asked to choose between two candidates. The first and leading in the polls is ‘self-confessed’ socialist Pedro Castillo, 51 years old, a schoolteacher, based Cajamarca, one of the poorest regions of Peru and home to South America’s largest gold mine. A leader of a teachers’ union since 1995, he has been a schoolteacher in the village of Puña in the northern Chota province.

His opponent is Keiko Fujimori, daughter of former president Alberto Fujimori. Aged 45, she has spent most of the last two years in pre-trial detention, accused of money laundering and running a criminal organisation, which she denies. Her father, Alberto Fujimori, governed Peru in the 1990s and was convicted over death squad killings and rampant corruption.

In the central and southern regions of the country there is significant support for Castillo, while Fujimoro is relying on votes from the middle classes based in Lima, the capital, where according to polls, barely 5% of voters support Castillo. Lima is home to a quarter of Peru’s 32.5 million citizens, but in the country’s poorest regions, Castillo’s support is over 50%, and he is also backed by the country’s half a million public school teachers.

Castillo’s Perú Libre (Free Peru) party manifesto describes its politics as “socialist, Marxist, Leninist and mariáteguist” – after the founder of the Peruvian Communist party José Carlos Mariátegui – and has set out plans to expropriate foreign mining projects. Castillo has pledged to replace the reactionary 1993 Constitution with a ‘people’s constitution’ (as Chileans are similarly pushing for); to regulate the media to “put an end to junk TV”; and to raise budget allocations for education and healthcare. Castillo also advocates widespread nationalisation, higher taxes and import substitution policies.

But like other leftist leaders in South America, he is a ‘social conservative’: against abortion, same-sex marriage, euthanasia and ‘gender perspective’ in schools. Castillo considers these issues as secondary to what he reckons is a “a battle between the rich and the poor, the struggle between the master and the slave.”

Fujimoro’s political message is simple: stop the ‘Marxist-socialist’ from becoming president and destroying Peru’s economy. Her main political plank is to free her father from prison (it seems that Presidents like her can dispense with the rule of law if they so choose). Naturally the media campaign has been vicious against Castillo and Peru’s middle class intellectuals, who have quite a reputation internationally, have lined up their support for Fujimoro.

Despite a string of corruption scandals which saw three presidents come and go, and the shock of the continent’s biggest ever corruption scandal in which four former presidents were accused of taking bribes from the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht, many ‘intellectuals’ take the position of Nobel prize-winning Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, who had endorsed Fujimori’s opponents in elections in 2011 and 2016, but now backs her because “she represents the lesser of two evils”.

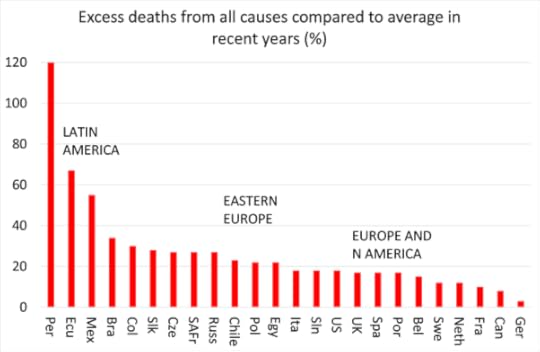

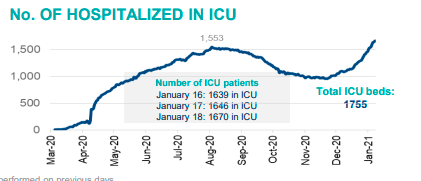

The election takes place in a country that has been the hardest hit of all from the COVID pandemic with 1.8m officially confirmed cases and more than 120,000 deaths, leaving a weak and mainly private healthcare system on its knees. Rising death rates have recently forced the return of the restrictions which made millions destitute at the outbreak of the pandemic.

Source: FT and author’s calculations

With the world’s worst per capita death toll from coronavirus and one of the biggest emerging market recessions last year, Peru is in crisis, with all the failings of weak capitalist economy that survives mainly on commodity exports controlled by foreign multi-nationals. Peru’s economy is highly dependent on its vast mineral resources, and its extractive sector is the main driver of growth. Peru is the world’s third-biggest producer of copper, its major export metal, and the country also attracts the world’s major mining companies to tap into its deposits of gold, silver, zinc and other minerals.

Peru in the decade leading up to the pandemic combined Latin America’s second highest annual growth rate of over 5% per cent with low inflation and modest debt. But as in the rest of the region, its pace of growth after the end of the commodity boom in 2012, coupled with the global economic slowdown, reduced economic expansion (dropping to an average 3% a year) and then the pandemic hit.

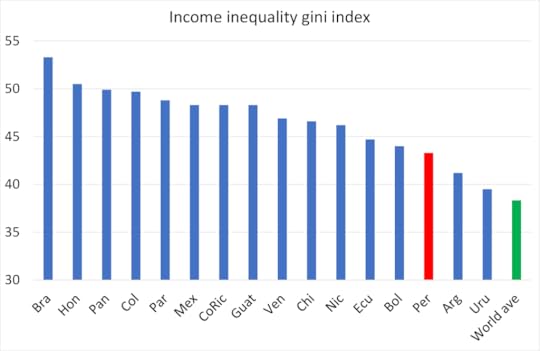

The economic success during the commodity boom hid deep problems endemic to all capitalist economies under the heel of imperialism. While income inequality in Peru is relatively low by Latin American standards, given that Latin America is the most unequal region in the world, that is not saying much. And when it comes to inequality of personal wealth, Peru is more unequal than Mexico and most of its close neighbours. The better-off in Peru had abandoned poor-quality health and education services for private alternatives and so would not pay for them in taxation. Many jobs that were created were low wage and informal.

Source: World Bank

Peru’s economy, like that of Bolivia and to some extent Chile, is almost a ‘one-trick pony’; its survival depends on the world price of metal materials, especially copper. Private investments in mining account for one-fifth of total private investment. Then there are agro exports like high-value fresh fruits and vegetables (mostly grapes, avocados, blueberries and asparagus) and fish meal. A boom in demand for these products in the ‘global north’ contributed to reducing poverty somewhat in rural areas.

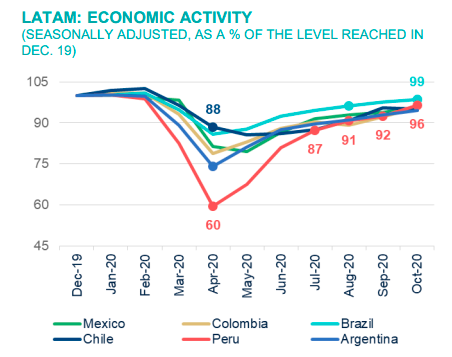

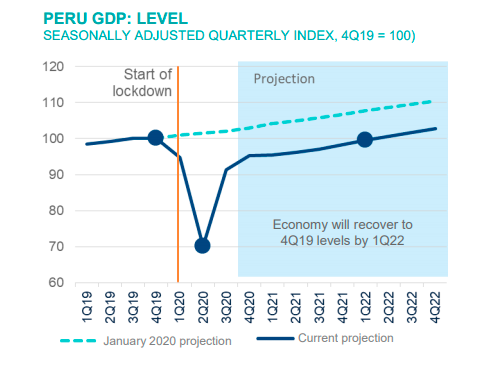

But the fall in commodity prices after 2012 up to the arrival of the pandemic ended this progress. And when coronavirus hit the country with full force last year, the economy was crippled, deaths soared and poverty worsened. A strict and prolonged quarantine led to a decline in GDP of 11.1 percent in 2020.

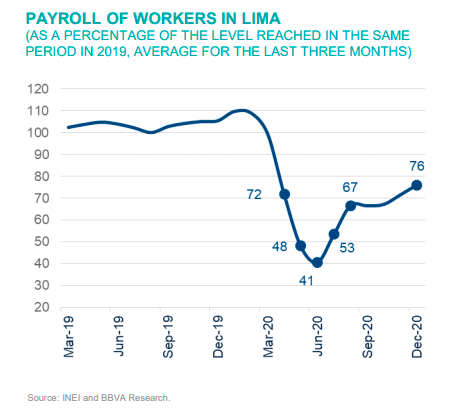

Employment fell 20 percent and wages even more.

What emerged was a picture of a state chronically unable to deliver. The health system proved hopelessly inadequate. Enforcement of the lockdown was patchy. Those who toiled in the informal economy had no choice but to continue working, risking death and illness.

At about 70 percent for labour outside of agriculture and half of all firms, informal working in Peru is among the highest in the LAC region, far above that of Mexico (60 percent) and Colombia (54 percent). Furthermore, about 13 percent of the country’s GDP originates in the informal sector, with limited access to credit from the formal financial system. This affects productivity significantly: productivity of informal enterprises is about one-third that of formal enterprises. Much of the welfare aid failed to reach its destination. Budgets were not fully spent. The government was slow to secure vaccines and became embroiled in a scandal after revelations that top officials were secretly inoculated first.

According to the latest data, 3.3 million Peruvians were thrown back into (official) poverty by the pandemic, while another 11m are on the brink. As Castillo says; “People don’t know there are thousands of children living in poverty and now, due to the pandemic, in extreme poverty.” Many Peruvians who considered themselves ‘middle-class’ and relatively better-off were also faced with impoverishment.

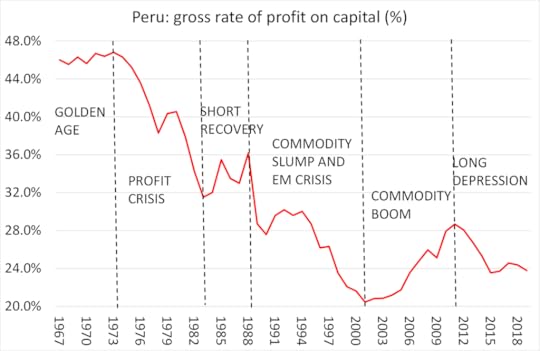

The profitability of Peruvian capital depends on the price of its commodity exports. In the graph below, you can see that the commodity price slump of the 1990s that led to the emerging market crisis of 1998 affected Peru just as much. In contrast, the commodity price boom of 2000-12 turned things up for Peruvian capital. The depression after that up to 2019 laid the basis for the current crunch.

Source: EWPT 2017, and Penn World Table 10.0, author’s calculations

These up and downs in profitability were more extreme in Peru compared to other Latin American economies. The level of profitability up to 2012 was higher in Peru than elsewhere in the region but dropped more in the commodity price slump afterwards.

Source: IMF

Indeed, there is a strong positive correlation between movements in world copper prices and profitability (0.26) and real GDP growth (0.32) in Peru.

The irony is that whoever wins today’s election may actually be able to preside over a relative recovery in Peru’s economic fortunes. Real GDP may recover to pre-pandemic levels by this time next year. And longer term, Peru’s commodity-based economy may sustain some new growth, if not at previous pandemic rates.

That’s because world copper prices are now at a ten-year high.

This price rise is being driven by global economic recovery, particularly in China, a major export destination, but also by long-term structural demand for copper as a key component in the fast expansion of electric vehicles and transport.

So perhaps the fear of Peru becoming Venezuela, if Castillo wins, as the ‘middle class’ believe and the capitalist media promote, will prove false. After all, “Castillo’s is not the Cuban or Venezuelan model,” said Pedro Francke, a university economics professor who is advising him. “He is much more in the image of [former Bolivian president] Evo Morales.”

May 30, 2021

The productivity crisis

It has been the historic mission of the capitalist mode of production to develop the “productive forces” (namely the technology and labour necessary to increase the output of things and services that human society needs or wants). Indeed, it is the main claim of supporters of capitalism that it is the best (even only) system of social organisation able to develop scientific knowledge, technology and human ‘capital’, all through ‘the market’.

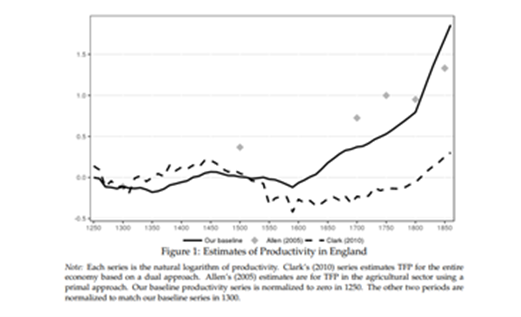

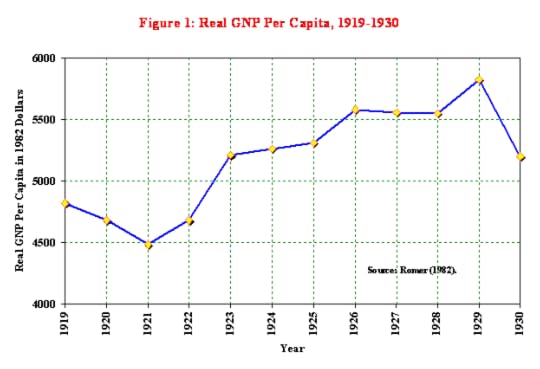

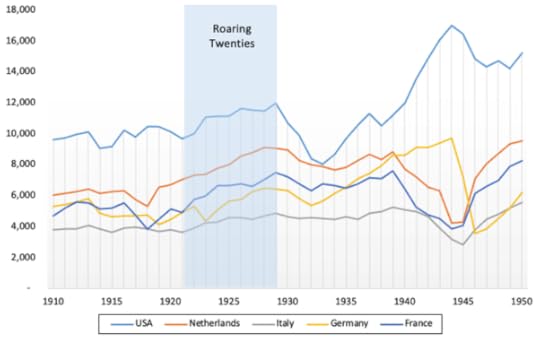

The development of the productive forces in human history is best measured by the level and pace of change in the productivity of labour. And there is no doubt, as Marx and Engels first argued in the Communist Manifesto, that capitalism has been the most successful system so far in raising the productivity of labour to produce more goods and services for humanity (indeed, see my recent post). In the graph below, we can see the accelerated rise in the productivity of labour from the 1800s onwards.

The rise of productivity under capitalism

The rise of productivity under capitalismBut Marx also argued that the underlying contradiction of the capitalist mode of production is between profit and productivity. Rising productivity of labour should lead to improved living standards for humanity including reducing the hours, weeks and years of toil in producing goods and services for all. But under capitalism, even with rising labour productivity, global poverty remains, inequalities of income and wealth are rising and the bulk of humanity has not been freed from daily toil.

Back in 1930, John Maynard Keynes was an esteemed proponent of the benefits of capitalism. He argued that if the capitalist economy was ‘managed’ well (by the likes of wise men like himself), then capitalism could eventually deliver, through science and technology, a world of leisure for the majority and the end of toil. This is what he told an audience of his Cambridge University students in a lecture during the depth of the Great Depression of the 1930s. He said: yes, things look bad for capitalism now in this depression, but don’t be seduced into opting for socialism or communism (as many students were thinking then), because by the time of your grandchildren, thanks to technology and the consequent rise in the productivity of labour, everybody will be working a 15-hour week and the economic problem will not be one of toil but leisure. (Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren, in his Essays in Persuasion)

Keynes concluded: “I draw the conclusion that, assuming no important wars and no important increase in population, the ‘economic problem’ may be solved, or be at least within sight of solution, within a hundred years. This means that the economic problem is not – if we look into the future – the permanent problem of the human race.” From this quote alone, we can see the failure of Keynes prognosis: no wars? (speaking just ten years before a second world war). And he never refers to the colonial world in his forecast, just the advanced capitalist economies; and he never refers to the inequalities of income and wealth that have risen sharply since the 1930s. And as we approach the 100 years set by Keynes, there is little sign that the ‘economic problem’ has been solved.

Keynes continued: “for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem – how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest (!MR) will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.” Keynes predicted superabundance and a three-hour day – the socialist dream, but under capitalism. Well, the average working week in the US in 1930 – if you had a job – was about 50 hours. It is still above 40 hours (including overtime) now for full-time permanent employment. Indeed, in 1980, the average hours worked in a year was about 1800 in the advanced economies. Currently, it is still about 1800 hours – so again, no change there.

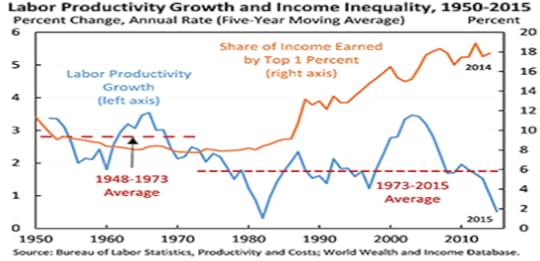

But even more disastrous for the capitalist mission and Keynes’ forecasts is that in the last 50 years from about the 1970s to now, growth in the productivity of labour has been slowing in all the major capitalist economies. Capitalism is not fulfilling its only claim to fame – expanding the productive forces. Instead it is showing serious signs of exhaustion. Indeed, as inequality rises, productivity growth falls.

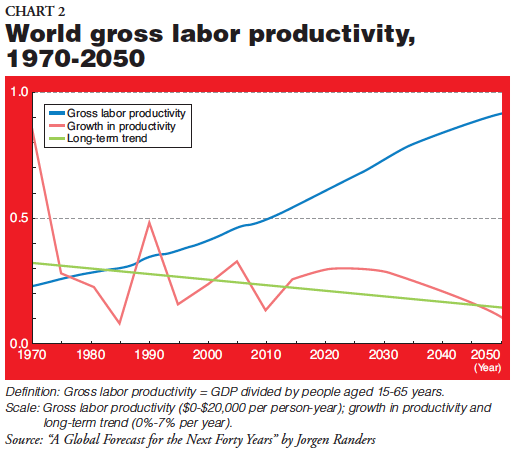

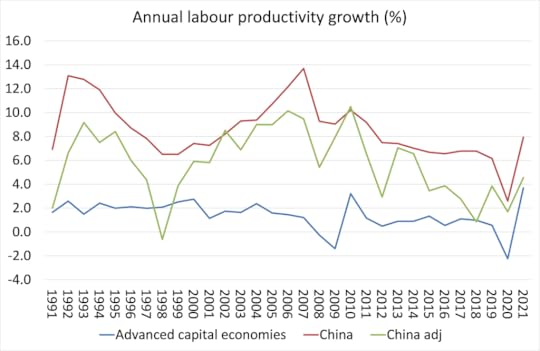

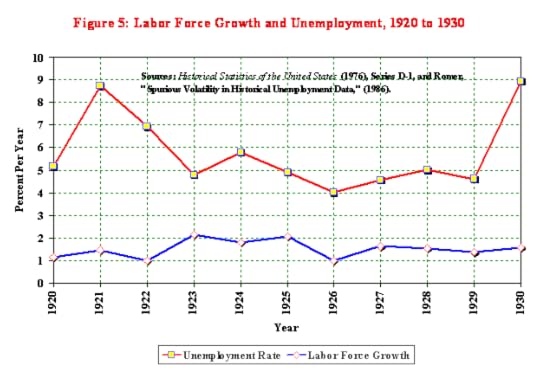

Economic growth depends on two factors: 1) the size of employed workforce and 2) the productivity of that workforce. On the first factor, the advanced capitalist economies are running out of more human labour power. But let’s concentrate on the second facto in this post: the productivity of labour. Labour productivity growth globally has been slowing for 50 years and looks like continuing to do so.

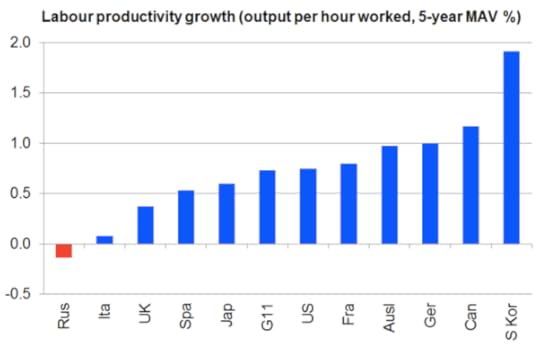

For the top eleven economies (this excludes China), productivity growth has dropped to a trend rate of just 0.7% p.a.

Why is productivity growth in the major economies falling? The ‘productivity puzzle’ (as the mainstream economists like to call it) has been debated about for some time now. The ‘demand pull’ Keynesian explanation that capitalism is in secular stagnation due to a lack of effective demand needed to encourage capitalists to invest in productivity-enhancing technology. Then there is the supply-side argument from others that there are not enough effective productivity-enhancing technologies to invest in anyway – the day of the computer, the internet etc, is nearly over and there is nothing new that will have the same impact.

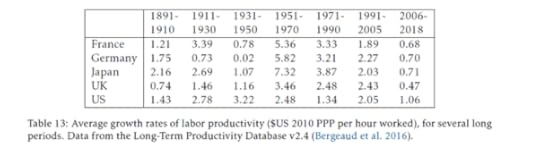

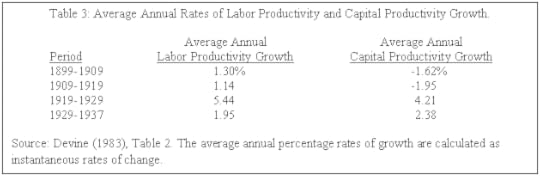

Look at the average growth rates of labour productivity in the most important capitalist economies since the 1890s. Note in every case, the rate of growth between 1890-1910 was higher than 2006-18. Broadly speaking, labour productivity growth peaked in the 1950s and fell back in succeeding decades to reach the lows we see in the last 20 years. The so-called Golden Age of 1950-60s marked the peak of the development of the ‘productive forces’ under global capital. Since then, it has been downhill at an accelerating pace. Annual average productivity growth in France is down 87% since the 1960s; Germany the same; in Japan it is down 90%; the UK down 80% and only the US is a little better, down only 60%.

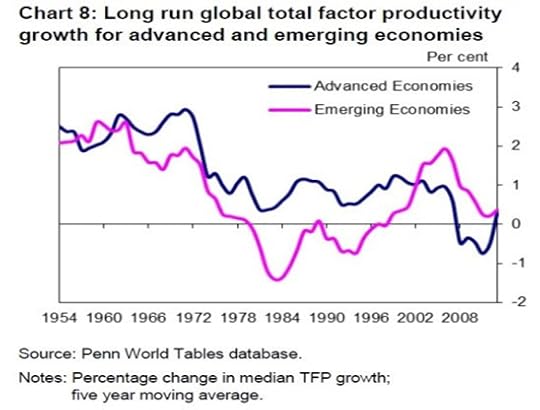

There are three factors behind productivity growth: the amount of labour employed; the amount invested in machinery and technology; and the X-factor of the quality and innovatory skill of the workforce. Mainstream growth accounting calls this last factor, total factor productivity (TFP), measured as the ‘unaccounted for’ contribution to productivity growth after capital invested and labour employed. This last factor is in secular decline.

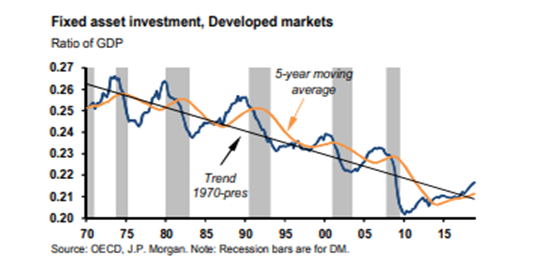

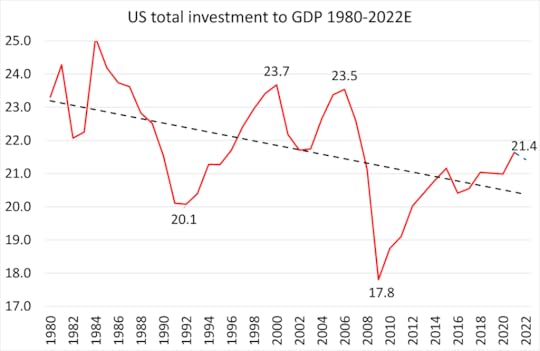

Corresponding to this slowing of labour productivity is the secular fall in the fixed asset investment to GDP in the advanced economies in the last 50 years ie starting from the 1970s.

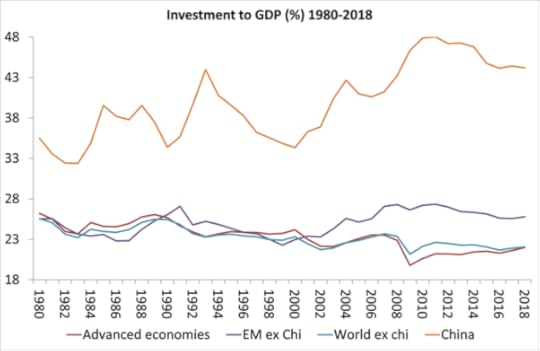

Investment to GDP has declined in all the major economies and since 2007 (with the exception of China). In 1980, both advanced capitalist economies and ‘emerging’ capitalist ones (ex-China) had investment rates around 25% of GDP. Now the rate averages around 22%, a more than 10% decline. The rate fell below 20% for advanced economies during the Great Recession.

The slowdown in both investment and productivity growth began in the 1970s. And this is no accident. The secular slowing of productivity growth is clearly linked to the secular slowing of more investment in productive value-creating assets. There is new evidence to show this. In a comprehensive study, four mainstream economists have decomposed the causal components of the fall in productivity growth.

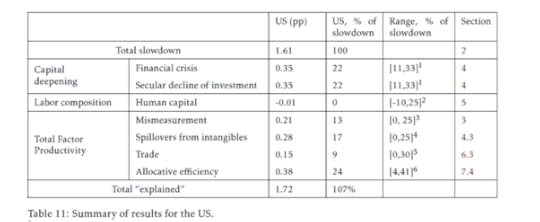

For the US, they find that, of a total slowdown of 1.6%pts in average annual productivity growth since the 1970s, 70bp or about 45% was due to slowing investment, either caused by recurring crises or by structural factors. Another 20bp of 13% was due to ‘mismeasurement’ (this is a recent argument trying to claim that there has been no fall in productivity growth). Another 17% was due to the rise of ‘intangibles’ (investment in ‘goodwill’) that does not show an increase in fixed assets (this begs the question of whether ‘intangibles’ like ”goodwill’’ are really value-creating). About 9% is due to the decline in global trade growth since the early 2000s; and finally near 25% is due to investment by capitalists into unproductive sectors like property and finance. The four economists sum up their conclusions: “Comparing the post-2005 period with the preceding decade for 5 advanced economies, we seek to explain a slowdown of 0.8 to 1.8pp. We trace most of this to lower contributions of TFP and capital deepening, with manufacturing accounting for the biggest sectoral share of the slowdown.”

In other words, if we exclude ‘intangibles’, mismeasurement and unproductive investment, the cause of lower productivity growth is lower investment growth in productive assets. The paper also notes that there has been no reduction in scientific research and development, on the contrary. It is just that new technical advances are not being applied by capitalists into investment. Now maybe, the rise of robots and AI is going to give a productivity boost in the major economies in the post-COVID world. But don’t count on it. As the great productivity theorist of the 1980s, Robert Solow, put it in a famous quip ‘you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics’ (Solow 1987).

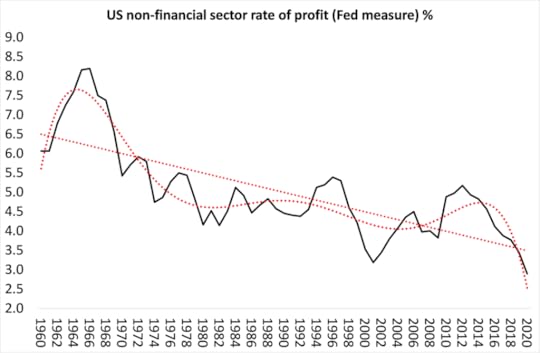

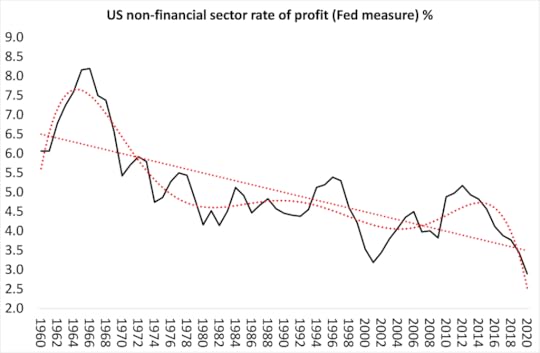

If investment is key to productivity growth, the next question follows: why did investment begin to drop off from the 1970s? Is it really a ‘lack of effective demand’ or a lack of productivity-generating technologies as the mainstream has argued? More likely it is the Marxist explanation. Since the 1960s businesses in the major economies have experienced a secular fall in the profitability of capital and so find it increasingly unprofitable to invest in heaps of new technology to replace labour.

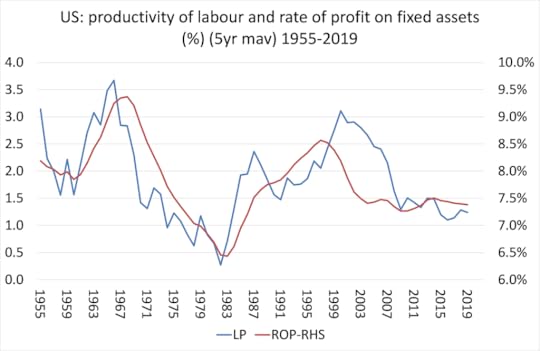

And when you compare the changes in the productivity of labour and the profitability of capital in the US, you find a close correlation.

Source: Penn World Tables 10.0 (IRR series), TED Conference Board output per employee series

I also find a positive correlation of 0.74 between changes in investment and labour productivity in the US from 1968 to 2014 (based on Extended Penn World Tables). And the correlation between changes in the rate of profit and investment is also strongly positive at 0.47, while the correlation between changes in profitability and labour productivity is even higher at 0.67.

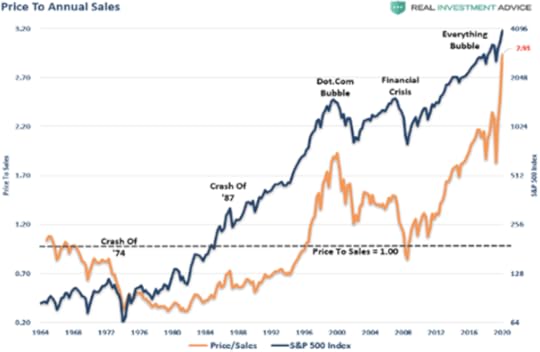

And as the new mainstream study also concludes, there is another key factor that has led to a decline in investment in productive labour: the switch by capitalists to speculating in ‘fictitious capital’ in the expectation that gains from buying and selling shares and bonds will deliver better returns than investment in technology to make things or deliver services. As profitability in productive investment fell, investment in financial assets became increasingly attractive and so there was a fall in what the new study calls “allocative efficiency” in investment. This has accelerated during the COVID slump.

There is a basic contradiction in capitalist production. Production is for profit, not social need. And increased investment in technology that replaces value-creating labour leads to a tendency for profitability to fall. And the falling profitability of capital accumulation eventually comes into conflict with developing the productive forces. The long-term decline in the profitability of capital globally has lowered growth in productive investment and thus labour productivity growth. Capitalism is finding it ever more difficult to expand the ‘productive forces’. It is failing in its ‘historic mission’ that Keynes was so confident of 90 years ago.

May 23, 2021

China: demographic crisis?

Much has been made recently of the slowdown in population growth in China. China’s population grew at its slowest rate in decades in the ten years to 2020, according to the latest census data, which also showed that births declined sharply last year. The nation’s once-in-a-decade census, which was completed in December, showed its population increased to 1.41bn in 2020 compared with 1.4bn a year earlier. The population grew just 5.4% from 1.34bn in 2010 — the lowest rate of increase between censuses since the People’s Republic of China began collecting data in 1953. Those over-65s now make up 13.5% of the population, compared with 8.9% in 2010 when the last census was completed.

This has led many China observers and Western economists to argue that China’s phenomenal growth rate that has taken over 850m Chinese out of poverty (as officially defined) is now over. The argument is that living standards have only risen for the average Chinese because China brought its huge workforce from the land and into the factories in the cities to produce goods for exports at low prices. Now with an ageing population and falling working-age population, China’s economy will flag. Given falling working population, along with an intensifying campaign by the US and its Western allies to isolate China economically and technically, China’s growth story is over.

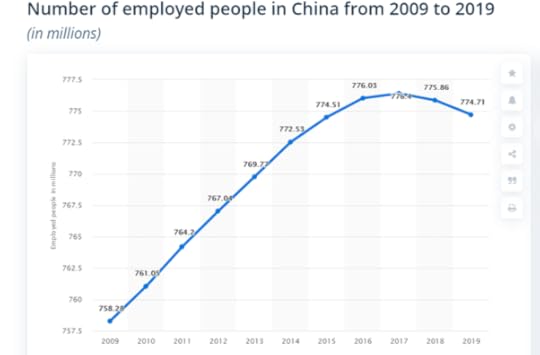

But is that true? Real GDP growth depends on two factors: more employment and more productivity per worker. If it is true that China’s workforce is not going to rise but even fall over the next decades, that means sustaining economic growth depends on raising the rate of productivity growth.

In a previous post, I have argued against the sceptics who reckon that China cannot achieve growth rates of say 5-6% a year over the remainder of this decade, or more than twice the rates forecast for the major capitalist economies (the US Congressional Budget Office forecasts just 1.8% a year for the US).

For a start, while China’s labour productivity growth rate has declined in the last decade, it was still averaging over 6% a year before the pandemic struck. That compares with just 0.9% a year in the advanced capitalist economies. Even if you accept the revisions made by The Conference Board to China’s productivity record (which I don’t: see – see the post above), China still achieved an over 4% a year productivity growth in the last decade, some four times faster than in the advanced capitalist economies.

So even if the labour force does not grow in this decade (or even decline by say 0.5% a year), real GDP growth in China is still going to be at a minimum of 3.5% a year, and much more likely to be between 5-6% a year, close to the Chinese government’s forecast in its latest five-year plan.

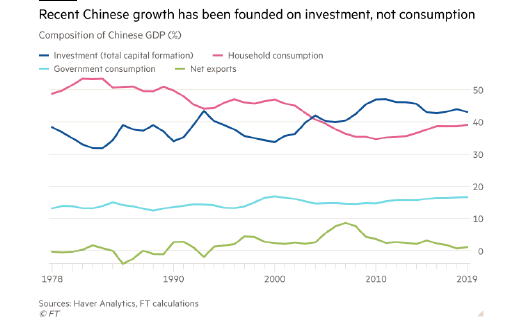

Ah, but you see, China cannot maintain previous productivity growth rates because its economy is badly imbalanced, so the latest argument of Western China ‘experts’ goes. What is this imbalance? Well, up to now China has grown fast partly because of its labour supply (which is no longer rising) and partly because of massive investment, led by the state sector, in industry, infrastructure and technology.

But now, continued expansion of investment can only be achieved by credit injections and rising debt. And that lays the basis for either poor productivity growth or a debt crisis, or both in the next decade. The answer, according to these experts, is that China should reduce its investment ratio (successful in boosting the economy) and switch to raising consumption and expanding service industries.

You might ask, how successful have capitalist economies been while their investment ratios have fallen back and consumption has dominated? Not at all. So this all smacks of the crude Keynesian view that it is consumption that drives investment and growth, not vice versa. And behind this is also the ideological aim to reduce China’s state sector domination and push for a service sector dominated by capitalist enterprises (including foreign ones), particularly in banking and finance.

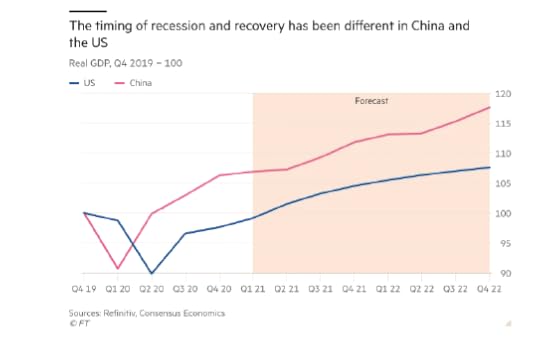

I have presented the arguments against this consumption model in a previous post on China, so I won’t repeat them here. Suffice it to say that they don’t hold water. Indeed, as Arthur Kroeber, head of research at Gavekal Dragonomics, has put it: “Is China fading? In a word, no. China’s economy is in good shape, and policymakers are exploiting this strength to tackle structural issues such as financial leverage, internet regulation and their desire to make technology the main driver of investment.” Kroeber echoes my view (as above) that: “On a two-year average basis, China is growing at about 5 per cent, while the US is well under 1 per cent. By the end of 2021 the US should be back around its pre-pandemic trend of 2.5 per cent annual growth. Over the next several years, China will probably keep growing at nearly twice the US rate.”

So there is no reason for China to abandon its growth model based on state-led investment in technology to compensate for the decline its workforce.

It has been the reason for its high productivity growth compared the West in the last few decades and will continue to be so, as long as the government does not buckle to the siren words of the Western experts. Those siren words have already led to the further opening-up of the financial sector to foreign companies and an increasing reliance of portfolio capital flows (namely financial investment) rather than productive investment. Since 2017, foreign investors have tripled their holdings of Chinese bonds and now own about 3.5 per cent of the market. Equity inflows have been comparable. That makes for an increased risk of a financial bust and damage to China’s productivity performance.

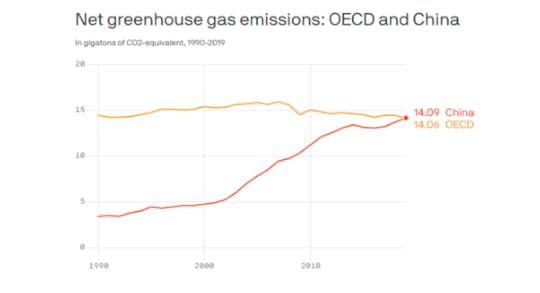

The move to investment in technology rather than heavy industry and infrastructure is key to China’s sustainable growth rate and to reducing the rise in greenhouse gas emissions, where China is now the world leader.

According to a recent report by Goldman Sachs, China’s digital economy is already large, accounting for almost 40% of GDP and fast growing, contributing more than 60% of GDP growth in recent years. “And there is ample room for China to further digitalize its traditional sectors”. China’s IT share of GDP climbed from 2.1% in 2011Q1 to 3.8% in 2021Q1. Although China still lags the US, Europe, Japan and South Korea in its IT share of GDP, the gap has been narrowing over time. No wonder, the US and other capitalist powers are intensifying their efforts to contain China’s technological expansion.

May 16, 2021

The unending nightmare of Gaza

The bombs rain down on Gaza city and the rest of the strip compounding the nightmare that Gaza is already for the people living there. Gaza, measuring 375 square kilometers (145 square miles) is home to around 2 million Palestinians, more than half of them refugees. Since 2007, the besieged enclave has been under a crippling Israeli and Egyptian blockade that has gutted its economy and deprived its inhabitants of many vital commodities, including food, fuel and medicine.

The people of Gaza have been confined to the enclave of the Strip and subject to a land, air and sea embargo. The entry of goods has been reduced to a minimum, while external trade and exports have been stopped. Meanwhile, the population has very limited access to safe water and lack regular electricity supply or even a proper sewage system.

The poverty rate in the Gaza Strip has reached 80% during the more than decade-long Israeli blockade, according to the Palestinian General Federation of Trade Unions. In addition, 77% of homes in Gaza have been destroyed and damaged by Israeli attacks leaving thousands of families homeless or displaced amid a crippled reconstruction process, according to Anne Jellema, head of Run4, a Netherlands-based relief foundation.

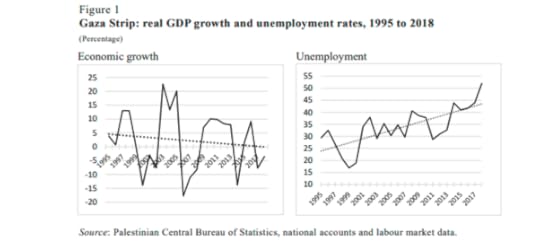

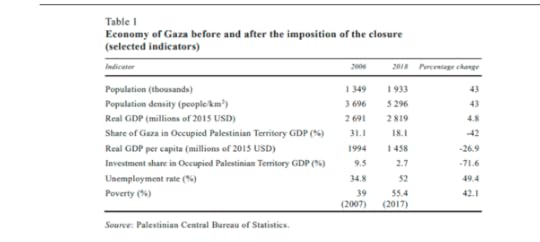

Unemployment and poverty is pretty bad in the whole of the West Bank but it is much worse in Gaza, where the poverty rate as defined by the World Bank (with a very low threshold) was 56% in 2018 compared to 19% in the West Bank and with two-thirds of young people unemployed. Moreover, people in Gaza suffer from much deeper poverty, with a “poverty gap”—the ratio between the average income of the poor and the poverty line—almost six times the level in the West Bank. These figures have been compiled by UNCTAD in a comprehensive report.

In addition to the prolonged blockade and restrictions by neighbouring Egypt, Gaza has endured three Israeli military operations in 2007, 2012 and 2014 that severely damaged civilian infrastructure and caused heavy casualties. At least 3,793 Palestinians were killed, some 18,000 were wounded and more than half of Gaza’s population was displaced, according to UNCTAD’s report. More than 1,500 commercial and industrial enterprises were damaged, along with some 150,000 household units and public infrastructure including energy, water, sanitation, health and educational facilities and government buildings.

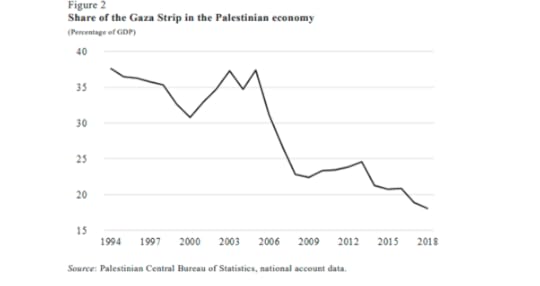

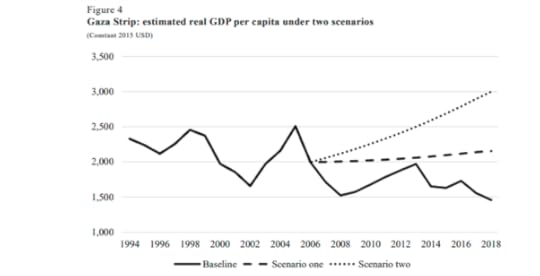

The Israel-led blockade of the Gaza Strip has cost the Palestinian enclave more than $16bn and pushed more than one million people below the poverty line in just more than 10 years, according to the report. UNCTAD analysis suggests that, had the pre-2007 trends continued (Scenario 1 in graph below), the poverty rate in Gaza would have been 15 per cent in 2017 instead of 56 per cent, while the poverty gap would have been 4.2 per cent instead of 20 per cent.

Instead, between 2007 and 2018, the economy in Gaza grew by less than 5 percent, and its share in the Palestinian economy decreased from 31 percent to 18 percent in 2018. As a result, GDP per capita shrank by 27 percent (baseline in graph above).

The Gaza economy has undergone a reversal in industrialization and agriculturalization. The share of agriculture and manufacturing in the regional Gaza economy declined from 34 per cent in 1995 to 23 per cent in 2018, while their contribution to employment fell from 26 to 12 per cent. This cripples any development of the Gaza economy and its capacity to expand employment.

And in 2020 the whole nightmare has been compounded by the coronavirus pandemic.

The UNCTAD report estimates that bringing Gaza’s people above the poverty line would require an injection of funds amounting to $838m, now four times the amount needed in 2007. But instead in 2018, the Trump administration withdrew its funding of UNRWA, the UN agency that supports five million Palestinian refugees in Gaza, the occupied West Bank, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan.

UNCTAD economist Richard Kozul-Wright commented that “The $200m cut was a huge hit to the Palestinian economy. …unless Palestinians in the Strip get access to the outside world, it is difficult to see anything but underdevelopment being the fate of the Gaza Palestinian society,” …It is really shocking that in the 21st century, two million people can be left in that kind of condition.”

May 14, 2021

Some notes on the world economy now

These notes were based on an interview with me by Swiss-based journalist Thomas Schneider in German in early May.

https://www.facebook.com/klaus.klamm.9235/

A sugar rush or economic recovery?

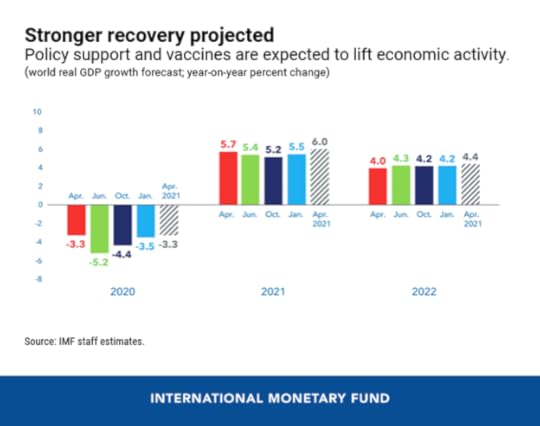

The IMF foresees a strong economic recovery. The assumption is that the virus can be controlled to such an extent that lockdowns and social distancing are no longer necessary. This is mainly due to the vaccination campaigns.

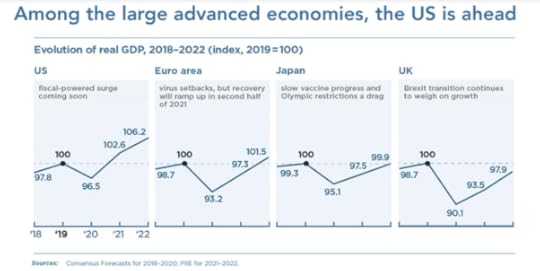

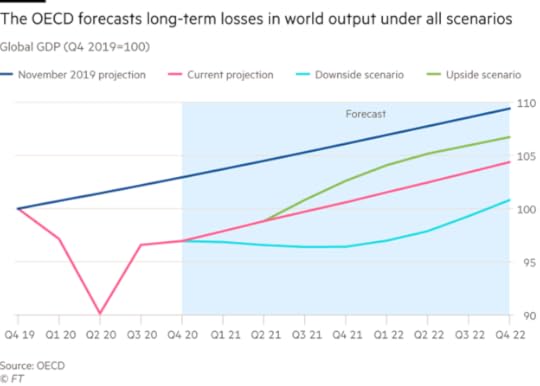

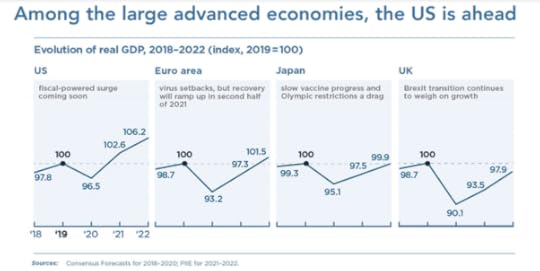

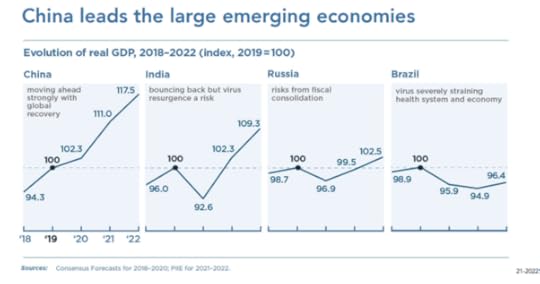

It looks like an upswing, at least in the G7 countries, this year most major economies, at least in advanced countries, are likely to (more or less) reach the real GDP level of the end of 2019 by the end of this year. Europe is forecast to lag slightly behind, while the US is developing more strongly. However, the situation in the so-called Global South, or ‘emerging economies’, is different. India and other countries are in a terrible situation.

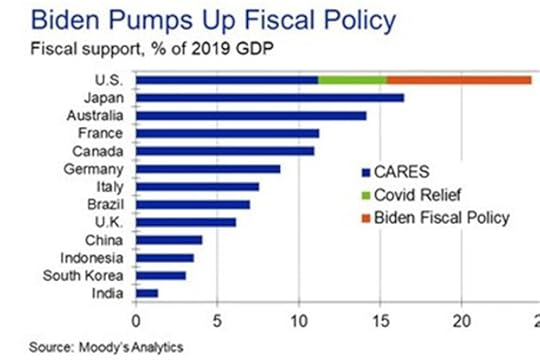

The US, along with China, is one of the countries that seems to be recovering most quickly. That’s partly because of the Biden administration’s big fiscal packages, which have reduced income losses and provided money to companies. The big question, however, is how effective and sustainable this will be.

If the IMF now says that we will have strong growth, it is mainly due to economies opening up. If a substantial part of an economy has been closed and can now reopen, there will obviously be a strong bounce back. But this pace will not be sustainable. It is really like a sugar rush and as you know, once the sugar is consumed, you feel a little sleepy and down afterwards.

The Biden administration is passing a huge infrastructure program through the US Congress to boost the economy and create jobs. Two trillion dollars sounds like a lot of money at first glance, but if you spread it over five to ten years, the stimulus then amounts to just half a percent of US economic output each year.

So Biden’s package will give the US economy an early rush, but it’s not enough to boost long-term growth. The low pre-pandemic growth rate will resume; and with it, productivity-boosting investment will be weak, wages will not grow much and jobs will remain precarious for a large part of wage-earners.

The scarring

The pandemic slump has been over two years in which there have been huge losses in production, resources, income and jobs, many gone forever. Globally, the slump has pushed some 150 million people further into the most abject poverty, who were otherwise seeing some improvement. These two years have been a huge disaster. The loss of the two years will never be made up again. It’s like an abyss, down one side and up the other, but the abyss is still left behind.

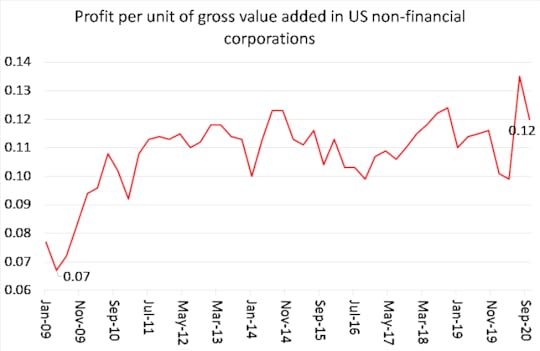

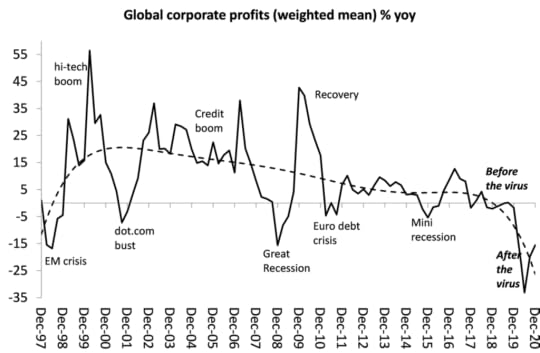

Profitability and growth

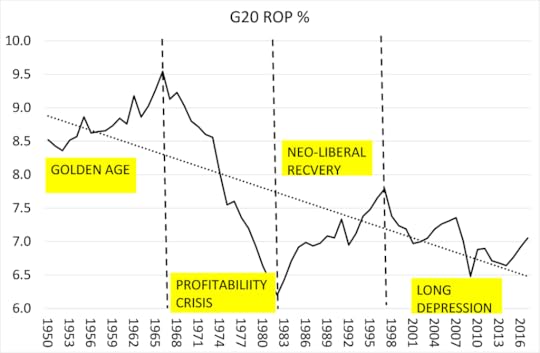

The global economy was already growing very weakly in 2019, which is likely to be the case again after the rapid recovery in 2021. That’s because capitalism grows sustainably and strongly only if profitability increases. However, average profitability was already very low before the pandemic, and in some countries, it was at the lowest level since the end of the Second World War.

The investments now being made to boost employment and income will not restore this profitability. Profitability will improve compared to the bottom of the pandemic, but it will not go above the rates of previous years. That means that investment and growth will not improve in the longer term. In capitalism, profitability determines economic development. Investments must pay off accordingly. If we had a different economy, we wouldn’t have to worry about that.

At the moment, we see in that around 15 percent of GDP is productively invested by the capitalist sector, ie not in property (4-5%) and financial speculation. By contrast, public investment is low: it contributes just 3 percent of GDP a year to productive investment, and Biden’s packages will increase that by only 0.5 percent, as above.

This will not be decisive for economic development over the long term. Indeed, even the U.S. Congressional Budget Office expects long-term average real GDP growth of only 1.8 percent per year in the US for the rest of this decade, based on its forecasts of productivity and employment growth. That rate is even lower than in the last decade.

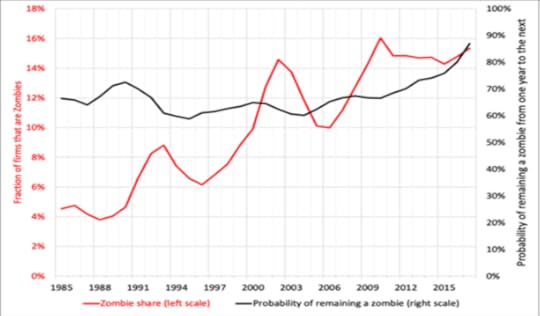

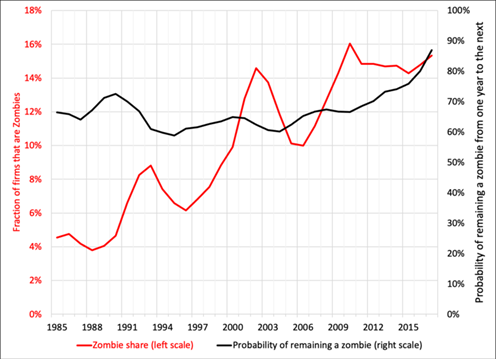

Zombie companies and debt

Profitability would only increase if some rotten layers of capital were removed. There are, for example, the so-called zombie companies, which make little profit and can only just cover their debts. In the advanced economies, we are now talking about 15 to 20 percent of the companies that are struggling in this situation. These companies keep overall productivity low, hindering the more efficient parts of the economy from expanding and growing.

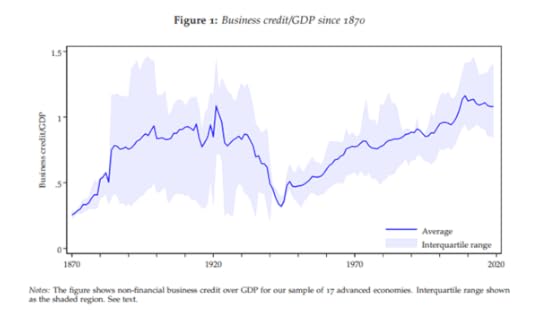

The zombies reflect in the enormous increase in debt, especially in corporate debt, globally. Debt levels are the highest since World War II in most developed economies. Interest rates are at historic lows, but the sheer mass of debt is still weighing on firms’ ability to invest productively.

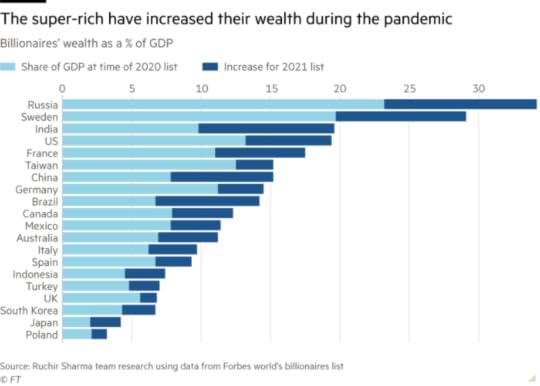

The immense debt also gnaws at profitability. When profitability falls in the productive sector, capital flees into financial speculation to make more profits. In the COVID slump, the super-rich have done so well!

When there is a financial crisis, there are defaults and devaluations, but there is no economic downturn if the productive sector is healthy. But the financial crisis can trigger a production crisis if it is combined with low profitability in the productive sector, as we saw in 2008.

Creative destruction

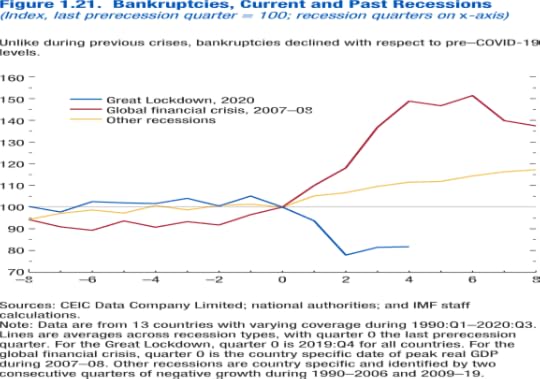

The burden of debt and low profitability can be overcome through so-called “creative destruction”, as Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called it. This is also the perspective of Marxian economic criticism, which Schumpeter had read very carefully. Through the devaluation (writing off) of capital and, in particular, the liquidation of inefficient, indebted companies, profitability can be raised. But that means a huge devaluation, in order to create the conditions for a new upswing.

So far, there has not yet been much destruction of capital because it is a grisly thought for governments and decision-makers – instead, bankruptcies of weak firms have been very low. Governments fear the political consequences and so are forced to continue with the big credit/money glut to keep companies running even if their productivity and profitability growth slows.

Inflation

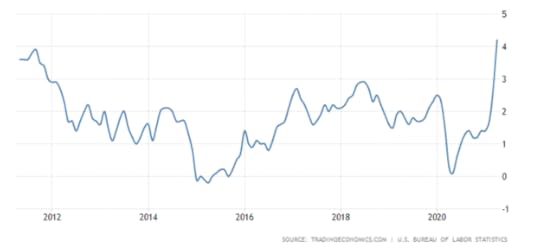

Many people have suffered severe hardship in the pandemic slump, but others have also saved money that could now be spent as economies open up. This will lead to a sharp increase in demand for all kinds of goods and services. Probably the supply side will not be able to keep up with that. So there could be stronger inflation over the next six to 12 months, especially in import prices, as international supply chains are still weakened. We could therefore see a rise in prices over a period of time.

Inflation in the late 1980s was immense. In most advanced countries, it was in the double-digit percentage range. Over the last two decades, inflation in these countries has, broadly speaking, been around 2%. But perhaps we will see inflation for the next 12 months until production can catch up with increased demand.

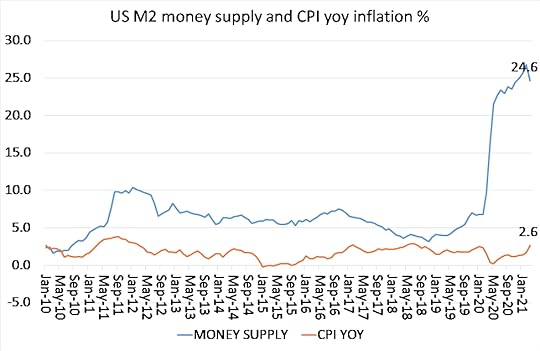

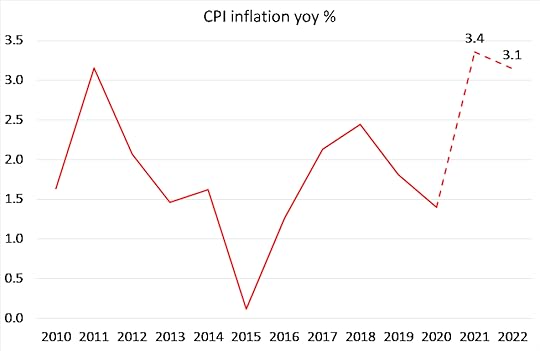

US CPI inflation yoy %

US CPI inflation yoy %The monetarist theory that an increased money supply must lead to inflation has been proven wrong. Central banks have spent vast amounts of money and supported banks and firms without prices rising. While the sum of money has increased, its orbital speed has decreased. Instead, it was parked at the banks, which did not lend it onto companies. The big firms often did not need the money, the smaller ones were cautious about borrowing even at low interest rates. So the banks put the money into financial speculation. There was also an unprecedented rise in the price of financial assets. But will it continue?

The answer is complex, but there are certainly two factors that are decisive. On the one hand, how much value is present in economies, how much flows to the capitalists as profit, and how much goes in wages to the workers. The development of these variables determines demand. The capitalists drive the demand for capital goods, the wage-earners for consumer goods. The level of wages and profits is therefore central, but the supply of money also plays a major role, because this is intended to compensate for weak profits and thus to stimulate demand.

In Marxist theory, there is a strong argument for a long-term decline in inflation. Rising productivity means that less investment is made in labour power and more in means of production, which also leads to an increasing organic composition of capital. As a result, both sources of demand are undermined: wages and profits (new value) growth slows. Capitalism therefore has a tendency towards disinflation when there are no counter-measures involved. Central banks have been trying to reverse the disinflation trend with money injections for about 30 years, but with little success.

The Keynesian notion that higher wages drive inflation is not supported by the evidence. Marx had once conducted a discussion with Thomas Weston, a trade union socialist of the Ricardian school. Weston claimed that the fight for higher wages must also lead to higher prices. Marx replied that this did not have to be the case, since the higher wages would likely come at the expense of profits. Inflation only needs to occur when wages and profits rise at the same time and then demand increases, while investment remains relatively low due to low profitability. It depends on the combination of these factors.

Golden Years and neoliberalism

The golden years of post-World War II capitalism were an exception, at least for the advanced economies: near full employment, rising living standards, high profits in advanced economies, and expansion of trade. If you look at the history of capitalism, you don’t find many such periods. The closest is probably the “Belle Epoque” from the 1890s to the 1910s. The big question is: why didn’t these phases last?

Neither mainstream economists nor most left-wing theories have an answer to this question. The latter claim that the post-World War II phase was over because of the departure from Keynesianism – because governments stopped spending enough money and stopped managing the economy. The follow-up question arises: why did they stop? The answer is found in economic development itself, the declining profitability of large capitals. This led to a decline in investment, to which Keynesian macro management did not find an answer. Thus the big capitals put pressure on governments to take a neoliberal path.

The law of value and profit

The central argument of Marxian criticism is based on the law of value. This roughly means that companies only invest if they can make a profit. Profit is the centre of their actions and not the needs of the people. These are only considered important so that the products can be purchased. Profit, however, comes from the exploitation of the labour force in the production process. Labour produces goods and services that can be sold but in constant competition with other capitalists. This means that companies are constantly looking for better methods of exploitation, new technologies and new methods.

For mainstream economists, profit simply does not matter. But even among the left-wing Keynesians, profit hardly appears. For them it is all about ‘demand’, about ‘speculation’ or about ‘financialisation’. These things all play a major role, but profit is the key category for understanding the capitalist process of production and accumulation. And it is important to put it in relation to a company’s investments: the rate of profit is the key to understanding how healthy an economy is. And profitability has tended to fall over the last 50 years, not linearly, but in a wave-like movement.

The high profits of tech companies such as Amazon, Apple or Alphabet are hiding the problem of profitability across the whole capitalist economy. There are a lot of unprofitable zombie companies and for most profit rates have fallen. We need to look at how this has affected investment. This is the central aspect that Marxian economic criticism can bring to the debate on the world economy.

Empirical evidence supports Marx’s law of the tendency to fall in the rate of profit. There are the counteracting factors to this law, but the law is the dominant factor. As far as we can measure the data, they suggest that there is a long-term trend towards falling rates of profit in the major economies. Every eight to ten years, capitalism plunges into crisis. We must continue to learn why these crises take place and what the political consequences.

May 9, 2021

Inflation and financial risk

Is inflation coming back in the major capitalist economies? As the US economy (in particular) and other major economies begin to rebound from the COVID slump of 2020, the talk among mainstream economists is whether inflation in the prices for goods and services in those economies is going to accelerate to the point where central banks have to tighten monetary policy (ie stop injecting credit into the banking system and raise interest rates). And if that were to happen, would it cause a collapse in the stock and bond markets and bankruptcies for many weaker companies as the cost of servicing corporate debt rises?

The current mainstream theory for explaining and measuring inflation is ‘inflation expectations’. Here is how one mainstream economic paper put it in relation to the US: “Over the longer-term, a key determinant of lasting price pressures is inflation expectations. When businesses, for example, expect long-run prices to stay around the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent inflation target, they may be less likely to adjust prices and wages due to the types of temporary factors discussed earlier. If, however, inflationary expectations become untethered from that target, prices may rise in a more lasting manner.”

But expectations must be based on something. People are not stupid; businesses and households’ expectations of whether prices are going rise (faster) depend on some guesses or estimates of how prices are moving and why. Moreover, expectations of price rises do not explain the price rises themselves.

There is a reason why mainstream economics has been driven into this ‘subjective’ corner in explaining and forecasting inflation. It’s because previous mainstream theories of inflation have been proven wrong. The main theory of the post-war period was the monetarist one, which I have discussed before. Its basic hypothesis is that price inflation in the ‘real’ economy occurs and accelerates if the money supply rises much faster than production in an economy. Inflation is essentially a monetary phenomenon (Milton Friedman) and is caused by central banks and monetary authorities interfering in the harmonious expansion of the capitalist economy.

But the monetarist theory has been proven wrong, particularly during the COVID slump. During 2020, money supply entering the banking system rose over 25% and yet consumer price inflation hardly budged and even slowed.

Monetarist theory has been proven wrong because it starts from the wrong hypothesis: that money supply drives prices of goods and services. But the opposite is the case: it is changes in prices and output that drives money supply.

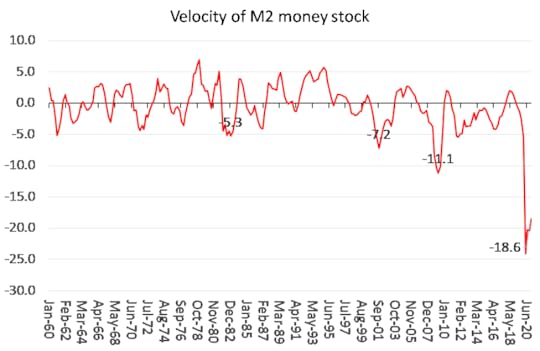

Take the monetarist formula: MV=PT, where M is the money supply; V is the velocity of money (the rate of turnover of money exchanges); P = prices of goods and services and T = transactions or actual real production activity.

Monetarist theory assumes that the velocity of money (V) is constant but this is just not true, especially during slumps and the COVID slump in particular.

The huge rise in money supply (M) has been dissipated by the unprecedented fall in the velocity of money (V). So MV, the left-hand side of the monetarist equation, has not moved up much at all. Contrary to monetarist theory, prices of goods and services have not been driven by the money credit injections.

But has this money disappeared then? No, it’s still there, but the money injections by the Federal Reserve and other central banks, mainly achieved by ‘printing money’ and purchasing huge quantities of government and corporate bonds, as well as making loans and grants, have ended up, on the whole, not in the hands of businesses and households to spend, but in the deposits of banks and other financial institutions. This money has been hoarded or used to fund speculation in financial assets (a booming stock market and investment in hedge funds etc). So the velocity of money (V) in goods and services transactions has plummeted.

The alternative mainstream theory of inflation is the Keynesian one. This is fundamentally a ‘cost-push’ theory, namely that companies push up their prices when their costs of production rise, particularly wages, the largest part of costs of production. In effect, Keynesian theory is a wage-push theory. Inflation depends on the relative demand for and supply of labour forcing up wages. So the argument goes: the lower the unemployment rate and the higher the demand for labour relative to the available supply, the more wages and then prices will be forced up. Keynesian theory sees inflation as being caused by workers getting too high wage increases (and eventually losing out in real terms as price rises eat into wage increases).

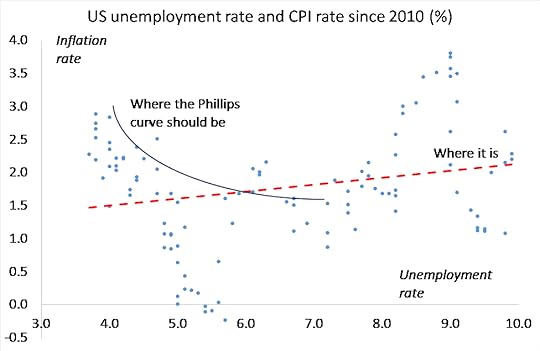

The usual Keynesian way to estimate likely changes in inflation is to use the so-called Phillips curve: the curve of the statistical relation between unemployment rate and the price inflation rate. Again, however, this theory has proven to be false. The ‘curve’ does not hold or is so ‘flat’ as to provide no guide to inflation. Indeed, since the Great Recession of 2008-9, unemployment rates in the major economies have dropped to near all-time lows and yet wage rises have been relatively moderate and inflation rates have slowed. This is the mirror image of the 1970s when unemployment rates rose to highs but so did inflation and we had what was called ‘stagflation’. Both examples show that the Keynesian cost push theory is false. In the Figure below, based on monthly data, the blue line shows where the Keynesian Phillips curve should be if it works; and the red line shows where it actually is. Indeed, the red line shows that falling unemployment leads to slowing inflation, at least since 2010!

The problem with Keynesian inflation theory is that it assumes that profits comes from investment and not from the exploitation of labour power. Keynesian theory says that S (surplus value) is the result of C (capital stock) and not V (labour power). So if C is steady, then S is steady and any price rises must come from V (wages rises). Marx’s view was different. In his speech to trade unionists in 1865, he argued against the view that wage rises cause inflation. In his view, a rise in V will generally lead to a fall in S (profits), not a price rise. That is why capitalists oppose wage rises vehemently.

And there is no wage push inflation. Indeed, over the last 20 years until the year of the COVID, real weekly wages rose just 0.4% a year on average, less even that the average annual real GDP growth of around 2%+. It’s the share of GDP growth going to profits that rose (as Marx argued in 1865).

If there is going to be any ‘cost-push’ this year, it’s going to come from companies hiking prices as the cost of raw materials, commodities and other inputs rise, partly due to ‘supply-chain’ disruption from COVID. The FT reports that “price rises have emerged as a dominant theme in the quarterly earnings season which kicked off in the US this month. Executives at Coca-Cola, Chipotle and appliance maker Whirlpool, as well as household brand behemoths Procter & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark, all told analysts in earnings calls last week that they were preparing to raise prices to offset rising input costs, particularly of commodities.”

To really get a grip on what causes inflation and whether it is coming back after COVID, we must return to Marx’s value theory. The demand for goods and services in a capitalist economy depends on the new value created by labour and appropriated by capital. Capital appropriates surplus value from exploiting labour power and buys capital goods with that surplus value. Labour gets wages and buys necessities with those wages. Thus it is wages PLUS profits that determines demand (investment and consumption).

Going back to the monetarist formula MV=PT, let’s switch it around, so that P = MV-T. Now if MV is unchanged as it broadly was in the COVID slump, then any change in P (prices) will depend on any change in T (the new value of goods and services produced).

Over the longer term, growth in T tends to slow. Why? Because T is based on capitalist production for profit and as capitalists tend to try and raise profits through mechanisation and the replacement of labour, there is a relative decline in new value produced (because only labour can create value, not machines). If the growth of T slows, then there is a tendency for price inflation to slow. And that is proven empirically. As the rate of profit began to fall in most major economies after the late 1990s and growth in new value dropped, particularly in the last decade, so price rises have ebbed.

Now workers don’t want inflation as it eats into real living standards. But capital does like some inflation, as price rises enable companies to expand production and increase profits at the expense of wages. Thus central banks and monetary authorities try to combat the long-term tendency for price inflation to ebb by injecting money and credit (more M). Money supply acts as a countertendency to slowing value creation. Thus the rate of inflation (P) depends on both M<>T. Of course, in practice the Fed and other central banks cannot ‘manage’ inflation as it depends on what is happening in capitalist production. Indeed, for the last 20 years, central banks have failed to achieve their target rate of inflation of around 2% a year with monetary zig zags on interest rates and monetary controls.

A Marxist model of inflation, which I have outlined before in a previous post, suggests that it is the movement of profits and investment demand along with money supply growth that will drive price inflation this year and next. So assuming sharp rises in profits and continued injections of money supply (if at a slower pace), this model forecasts US consumer inflation will go over 3% this year and next.

In the short term, inflation of goods and services could rise anyway because of ‘base effects’ (statistical blips), ‘supply chain’ disruption from COVID or so-called ‘pent-up demand’. But these factors are probably transitory, as the Fed Chair Jay Powell argues. But if inflation does go well above the Fed’s 2% annual target rate for some time, that could lead to a significant rise in yields (interest rates) on bonds, which are not under the control of the Fed. US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen, the former Fed chief, hinted that if inflation did pick up more than expected, the Fed would act to control it through ‘tighter’ monetary policy which would also drive up yields.

This raises the odds that weaker parts of the corporate sector in the major economies will get into difficulties and invoke a debt crisis. Remember: business debt relative to output is at its highest ever in the major economies.

In its recent Financial Stability Report, the US Federal Reserve warned that existing measures of hedge fund leverage “may not be capturing important risks”, pointing to the collapse of Archegos Capital as an example of hidden vulnerabilities in the global financial system. The Fed found that some asset valuations are “elevated relative to historical norms” and “may be vulnerable to significant declines should risk appetite fall”. In other words, a stock and bond market collapse is possible.

Borrowing cheap money hoarded by the banks to speculate on financial markets is called ‘margin debt’. According to the US Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, margin debt hit $822bn by the end of March — just after Archegos had failed. That was almost double the $479bn level of March 2020, when the pandemic lockdowns started and the Fed pumped in credit. And it’s far more than the around $400bn peak that margin debt reached in 2007, just before the financial crisis.

So any significant return of inflation in goods and services may bring down the house of cards that is the financial sector. What happens in the productive sectors of the capitalist economy still remains decisive.

May 2, 2021

Wealth inequality

I have written before about the fact that, both in advanced and so-called ’emerging economies’, wealth is significantly more unequally distributed than income. Moreover, the pro-capitalist World Economic Forum has reported that: “This problem has improved little in recent years, with wealth inequality rising in 49 economies.”

The usual index used for measuring inequality in an economy is the gini index. A Gini coefficient of zero expresses perfect equality, where all values are the same (for example, where everyone has the same income). A Gini coefficient of one (or 100%) expresses maximal inequality among values (e.g., for a large number of people where only one person has all the income or consumption and all others have none, the Gini coefficient will be nearly one).

For the US, the current gini index for income is 37.8 (pretty high by international levels), but the gini index for wealth distribution is 85.9! Or take supposedly egalitarian Scandinavia. The gini index for income in Norway is just 24.9 but the wealth gini is 80.5! It’s the same story in the other Nordic countries. The Nordic countries may have lower than the global average inequality of income but they have higher than average inequality of wealth.

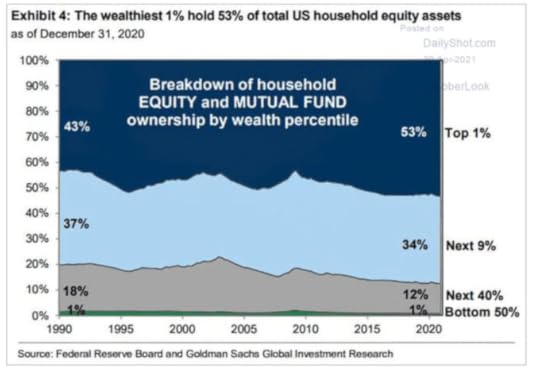

Another way of measuring inequality is to consider the share of wealth or income that the top 10% or top 1% etc have. And we can break personal wealth down into two main categories: property wealth and financial wealth. A larger section of the population has property wealth, although this is very unequally distributed. But financial wealth (stocks and shares, bonds, pension funds, cash etc) is the province of a tiny number of people and so is even more unequally distributed. The latest figure for the US for financial wealth inequality is truly staggering on this measure. The richest 1% of US households now own 53% of all equities and mutual funds held by American households. The richest 10% own 87%! Half of America’s households have little of no financial assets at all – indeed they ar in debt. And that inequality has been rising in the last 30 years.

And as the WEF says, after the huge rise in the prices of property and financial assets over the last 20 years, fuelled by cheap credit and reduced taxation, this concentration of personal wealth has increased sharply – something that Thomas Piketty in his book, Capital in the 21st century, highlighted several years ago.

The latest data for Italy, one of the top G7 economies, confirms this increased inequality of wealth. In a new study of Italian inheritance tax records, researchers found that the wealth share of the top 1% (half a million individuals) increased from 16% in 1995 to 22% in 2016, and the share accruing to the top 0.01% (the richest 5,000 adults) almost tripled from 1.8% to 5%. In contrast, the poorest 50% saw an 80% drop in their average net wealth over the same period. The data also revealed the growing role of inheritance and life-time gifts as a share of national income, as well as their increasing concentration at the top. The huge wealth of a few individuals is getting larger because it can be passed onto relatives with little or no taxation.

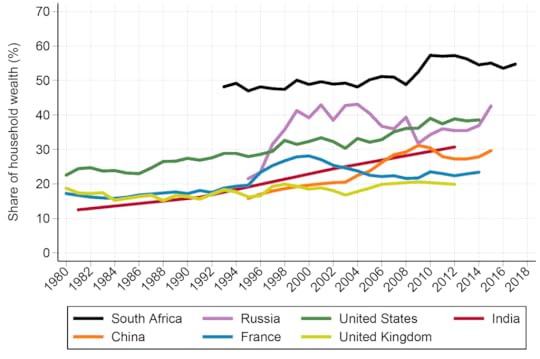

But the concentration of personal wealth in the advanced capitalist economies is nothing compared to what is happening in the poorer nations of the world. A new study compared the inequality of wealth in South Africa against similar ’emerging economies’ and also historically since the end of apartheid. Extreme wealth inequalities in South Africa have got worse, not better, since the end of the apartheid regime. Today, the top 10% own about 85% of total wealth and the top 0.1% own close to one-third. South Africa continues to hold the dubious honour of having the worst wealth inequality among the major economies of the world. The South African top 1% share has fluctuated between 50% and 55% since 1993, while it has remained below 45% in Russia and the US and below 30% in China, France, and the UK.

Top 1% wealth shares

But as I have argued before, real wealth concentration id about the ownership of productive capital, the means of production and finance. It’s big capital (finance and business) that controls the investment, employment and financial decisions of the world. A dominant core of 147 firms through interlocking stakes in others together control 40% of the wealth in the global network according to the Swiss Institute of Technology. A total of 737 companies control 80% of it all.

This is the inequality that matters for the functioning of capitalism – the concentrated power of capital. And because inequality of wealth stems from the concentration of the means of production and finance in the hands of a few; and because that ownership structure remains untouched, any increased taxes on wealth will fall short of irreversibly changing the distribution of wealth and income in modern societies.

April 26, 2021

Post-Keynesianism: the principles

Like Marxist or mainstream economics, Keynesian economics has several strands. There is Keynesian economics seen within the parameters of general equilibrium economics, where changes in income and expenditure, consumption and investment, interest rates and employment will tend to an equilibrium between employment and inflation, as long as there are no exogenous ‘shocks’ to the market economy. If wages and interest rates fall enough, then full employment and investment growth will be achieved.

This is what Joan Robinson, a follower of Keynes, called ‘bastardised Keynesianism’. It removed all the radical features of Keynesian economics, which, to Robinson, politically a quasi-Maoist, were that full employment could not be automatically achieved in modern ‘market’ economies. More likely there would be an equilibrium of underemployment; and that this would be due to uncertainty about the future for capitalists in making investment decisions and irrationality among economic ‘agents’ like consumers and capitalists.

This radical view of Keynesian economics has come to be called post-Keynesianism (PK), with the main proponents being contemporaries of Keynes like Robinson and Michal Kalecki, the Marxian-Keynesian; and later Hyman Minsky, the socialist-Keynesian. Now there is a whole school of post-Keynesian economics, with journals, conferences and think-tanks.

PK economics dominates and influences the views and policies of the left-wing in the labour movements of the major economies (Corbynomics, Sanders etc) – it is the radical wing of Keynesian economics in general, which in turn has dominated the labour movement since Keynes (except for periods since the 1980s when neo-liberal mainstream ‘free market’ theories influenced labour leaders for some decades).

On my blog I have spent much ink explaining where Marxist economics differs from Keynesian economics in all its strands. For me, a Marxist approach to theory and policy better explains the nature of capitalism and what are the right policies for the labour movement to adopt in its struggle against capital and for a better society for all. Indeed, I think that Keynesian economics is a diversion from achieving that, mainly because its analysis of capitalism is wrong. Moreover, its policy conclusion is that capitalism can be fixed or managed to work for all with a few clever policy adjustments.

PK theory, because it appears much more radical (in that it reckons capitalism cannot be easily managed to benefit all) and because many of its exponents would consider themselves socialists (even Marxists), is in these ways even more misleading as it relies on a radical view of Keynesianism, and yet Keynes was hardly the radical that PK followers think he was.

So let me once again, examine the basic ideas of post-Keynesian economics.

To do this, I shall draw on a recent post called “The Post-Keynesian World View in Five Principles”, based on a talk that an ‘Alex’ gave to the Berggruen Institute on zoom.

Alex first tells us about the rising popularity of ‘post-Keynesianism’ after the global financial crash and the COVID slump. Alex reckons it has become popular because “financial markets love it, because it does a good job explaining how the economy runs, which is helpful if your paycheck depends on understanding the economy.”

I’m not sure that because financial analysts apparently ‘love it’ that this a good reason to agree with PK. But Alex goes on to explain that PK “gives good causal heuristics for understanding the impact of financial flows on production, and on the economy at large. It also counsels realism about the impact of government policy on economic outcomes. Public debt and private debt are different, the money supply doesn’t cause inflation, private debt does eventually have to roll over and will have real impacts if it doesn’t.”

So, according to Alex, PK tells us better about how the modern economy works and why debt (particularly private debt) matters. One strand of PK, Modern Monetary Theory, has recently enlightened us all on the workings of money in capitalism, Alex reckons, and as he says “MMT originally grew out of the post-keynesian research agenda, and much of its underlying economic model is still very post-keynesian in structure.” My critique of MMT thus also applies to PK.

Alex now makes an interesting statement. “In a capitalist economy, production is undertaken for profit and not for use. As such, value is usually measured using the social convention of accounting. Production happens in anticipation of flows of money, just the same as investment and consumption. On this view, things are worth their book value, more or less, and economic actors act based on these book values. What the post-keynesians think is that this represents a good starting point for economic theorizing, to use the quantities that the actors themselves use.”

What does this mean? Alex seems to adopt the basic point of Marx’s law of value: namely that capitalist production is for profit not social use. And we should measure value in money terms as capitalists do. This sounds promising. But then Alex moves straight on to talk about flows of money and investment and consumption. There is no further mention of the role of profit, after having told us that capitalist production is for profit, not investment or consumption. In my view, this is typical of PK followers. They very quickly dispense with profit in their theoretical explanations, as we shall see below.

Having dispensed with the role of profit, Alex tells us that we should instead consider modern economies from a “balance sheet-based view of the economy as a whole. Individual actors have assets and liabilities, incomes and expenditures. Someone’s asset is someone else’s liability, and vice versa. Everything is interrelated through the use of these conventions.”

Thus we move from the underlying driver of capitalist economies: profit and what is happening to profits and profitability to “studying the flow of payments and the accumulation of assets, not the allocation of scarce resources to their most efficient ends. One of the main benefits this approach has is that it rules out some impossible outcomes: not everyone can run a trade surplus, if there’s a trade deficit, either the private sector or the public sector has to run a deficit to finance it.”

So we are rapidly reduced to macro-identities in analysing economies ie Income = Expenditure; public and private sector deficits and surpluses; trade balances etc. But not profit or the origins of profit.

“Our next principle is that everything is expectation.” Alex tells us a key principle of PK is to look at ‘expectations’. “Expectations inform actions, and these actions in turn create reality. Maybe the simplest model of the Keynesian causal cycle is to say that expected demand drives investment, investment drives employment, employment drives wages, wages drive consumption, consumption drives demand, and demand validates investment. Expected demand drives investment, because businesses only invest in added capacity or hiring more workers when they think that more people will want to buy their product in the future than do at the present moment. If they expected the same demand, or less, there would be no need to invest at all. They could keep running the same equipment.”

So here we have it. Investment under capitalism is not driven by profit or profitability after all, but by ‘expectations’, and not even by future profit, but by ‘expected demand’. This drives investment which in turn leads to employment and wages.

But is this the causal sequence in capitalist production and accumulation? In many previous posts, I have highlighted the key macro equation in post Keynesian identities. Here it is again.

National Income = National Expenditure

National Income = Profits + Wages

National Expenditure = Investment + Consumption.

So Profits + Wages = Investment + Consumption

If we assume workers spend all their wages on consumption and capitalists invest all their profits, we get:

Profits = Investment

According to PK theory, it is Investment that drives Profits, not vice versa. And ‘Expected Demand’ drives Investment (says Alex) and Investment drives Wages and Profits.

Or as Michel Kalecki, whose equation this is, said: ‘workers spend (Consumption) what they get (Wages); and capitalists get (Profits) what they spend (Investment)’.

In my view, this is manifestly a wrong view about the capitalist economy. Instead of Investment driving Profits as above, the reality is that Profits drive Investment. Thus, capitalist investment is not result of the level of ‘expected demand’, or some entirely subjective psychological view of investors having what Keynes called ‘animal spirits’, but the result of an objective measure of previous (and likely profitability) of investment. But as with Keynes, PK does not want to put profits up front, but reduce it to a consequence of investment (or, in reality, to hide it from analysis altogether). For further on this, read the excellent chapter 3 by Jose Tapia in World in Crisis.

Alex refers to the work of Hyman Minsky, a PK theorist who relied heavily on ‘expectations’ to explain investment decisions. “Hyman Minsky talks about this extensively: if you think an asset’s price is going to skyrocket, you start buying it to make a profit. You can even borrow money against it and use that money to buy more. As the price goes up, the amount you can borrow against goes up as well, and the price starts flying. The whole Gamestop episode last month was a version of this that used call options rather than margin loans, but the principle is similar. The problem comes for Minsky when the borrowing gets cut off: there’s nothing to support the prices and everything crashes down. Sometimes the operation of extreme expectations can create wackiness in financial markets that can have dire consequences for the economy at large.”

So according to Alex (and Minsky) ‘extreme expectations’ create a “wackiness in financial markets” that brings the whole economy crashing down as in the global financial crash of 2008. But why does the whole thing crash after going so well – apparently because of ‘extreme expectations’? But this is an answer that only poses the question of why are expectations fine at one moment and then ‘extreme’ at another. What makes them extreme?

No doubt Minskyites will quote Minsky’s famous phrase that “stability breeds instability’. But again, this is just a clever phrase to cover the fact that PK theory does not have a theory of financial crises except that they happen when things get ‘extreme’.

In my view, Marxist economic theory does have an answer. It relies on an objective view of the laws of motion under capitalism, in particular, changes in the profitability of productive (value-creating) capital. If profitability is low in productive sectors, capitalists try to counteract this in several ways, one of which is to invest in what Marx called fictitious capital. But financial profits still depend on the profitability of the productive sectors and if profitability falls to the point that the mass of profits or new value (wages and profits) falls, then a crisis ensues in the productive sector that flows into the financial sector. I and other Marxist scholars have provided much empirical evidence to explain recessions and, in particular, the global financial crash and the ensuing Great Recession, not as a ‘Minsky moment’ when financial stability turns into instability suddenly, but as ‘Marx moment’; when profits drop to the point where the value of means of production and labour must be devalued, including fictitious assets.

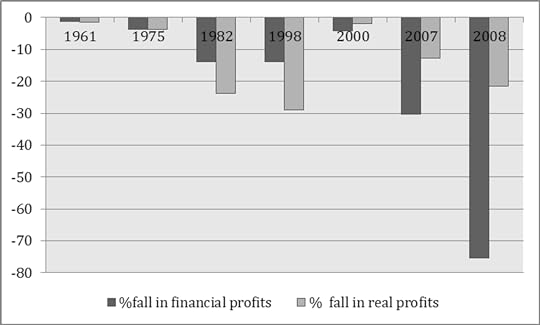

Indeed, as G Carchedi has shown (see graph below), when both financial profits and profits in the productive sector start to fall, an economic slump ensues. That’s the evidence from the post-war slumps in the US. But a financial crisis on its own (as measured by falling financial profits) does not lead to a slump if productive sector profits are still rising. see Carchedi, pages 59-62 Chapter 2 of World in Crisis.

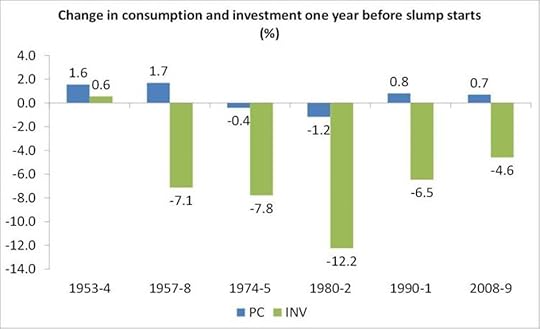

Nevertheless, Alex ploughs on with the PK view that “Demand creates supply, by driving investment. Investment then creates both savings and the capital stock while the capital stock in turn creates resources.” Again, there is no explanation of why demand slows or falls, leading to an investment collapse. “Consumption, not savings, drives investment and helps society prepare for the future” says Alex. But the empirical evidence is the opposite. In nearly every single recession in the US since 1945, it has been investment that has dived before while consumption has hardly dropped. And decisively, it is profits has led investment into slumps and out of them, not vice versa.

Alex quotes “Keynes very famously cites the “Fable of the Bees” in the General Theory. As quickly as possible, the fable tells the story of a community that outlaws luxury and finds itself much poorer now that everyone who used to work in luxury production is out of work.” Here we have the ludicrous argument offered by Keynes and the early 19th century reactionary parson Thomas Malthus before him that without rich people spending, there would be a ‘lack of demand’ and economies would go into slumps. These are soothing words to the ears of the billionaires owning the FAANGs, (apart from being empirically incorrect as many studies show the rich tend to save more than the poor, as they have done in the COVID slump).

According to Alex, what’s wrong with alternative theories of crises is that they assume investment must come from savings so that consumption must be curtailed in order to allow for investment. “In the Ricardian story, which is still used today by Marxists and Austrians, the main fund for investment is savings. The assumption is that the economy has a maximum capacity that it is usually running at, and that whatever is not consumed in a given period is saved. In order to invest, savings have to come first, so ipso facto consumption has to be curtailed in order to increase investment.”

Alex reckons that Keynes trashed this view with his idea of the Paradox of Thrift. “If everyone tries to increase their savings rate, that means they are cutting their consumption rate. If their consumption rate declines, then the incomes of the people selling things to consume falls. Problem is, total output is set by consumption and investment. If investment stays constant and consumption falls, total output falls. The savings rate goes up, but only because everyone is now saving the same amount in dollar terms out of a lower income in dollar terms.”

As Alex says, PK’s Kalecki “looks at the same idea from the firm side, rather than the household side. If employers minimize costs by minimizing wages in aggregate, they wind up cannibalizing the consumption base of the economy as a whole, which eats into profits. If you go the other way, and let wages rise, the rate of profit rises right alongside.”

There are two things here. It may be the view of the Austrian school that savings are needed for investment, but it is not that of Marxist economics. It is not ‘savings’ that is required for investment, but profits, or capitalist savings. Household savings are not required to kick off the capitalist accumulation process. What follows is that profits then lead investment which in turn leads to employment, incomes and finally consumption – the reverse of the PK view. Which is correct? I have already cited the evidence.

Indeed, there is not so much a ‘paradox of thrift’ Keynesian-style but a ‘paradox of profitability’, namely as capitalists strive to raise their individual profitability through investments in means of production and shed labour, they actually reduce the overall profitability of the capitalist economy and eventually provoke a crisis.

The second point is that the Kalecki theory leads to an eclectic view of crises. Sometimes they are ‘wage-led’, ie wages and consumption are too low to sustain growth and sometimes they are ‘profit-led’, ie wages are too high and profits too low to sustain growth. But neither shall the twain meet. There is no coherent theory of the causes of regular and recurring crises every 8-10 years; sometimes it is one thing and sometimes the other.