Michael Roberts's Blog, page 38

April 15, 2021

IMF and debt: a new consensus?

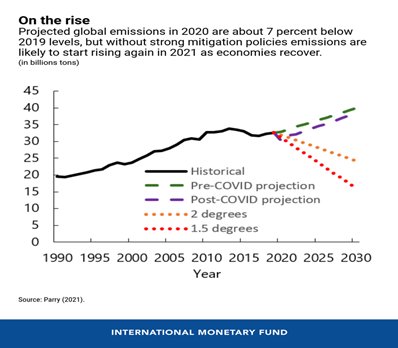

There is much talk among ‘progressive’ economists that the IMF and the World Bank have turned over a new leaf. Gone are the days of supporting fiscal austerity, demanding that national governments get public debt levels down and insisting on conditions for countries borrowing IMF-WB funds that their governments privatise their state assets, deregulate markets and reduce labour rights.

Now after the experience of the unprecedented COVID pandemic slump, the old ‘Washington Consensus’ is over and has been replaced by a new ‘consensus’. Whereas the “Washington Consensus” for international economic policies of the 1990s saw government failures as the reason for poor growth performance and advised governments ‘to get out of the way’ of market forces, now the IMF, the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation’s chiefs call for more fiscal spending, more funds for lending, and measures to reduce inequality between nations and within nations through higher taxes on the rich.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Washington_Consensus

Such ‘progressives’ like Martin Sandu in the Financial Times are excited by this change of heart and policy. “Back in the ‘90s, it was a truism the Washington consensus reflected the aligned priorities of two DCs: the international institutions based there and the US government — with the latter to a significant degree driving the former…but it is hard to argue today that the IMF and the World Bank simply parrot US preferences.”

https://www.ft.com/content/3d8d2270-1533-4c88-a6e3-cf14456b353b

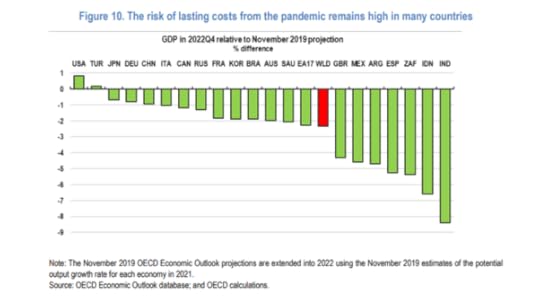

And the rhetoric of the IMF and World Bank as posed by the likes of IMF chief Georgieva certainly seems different. Throughout the virtual Spring meeting of the IMF-WB last week, and on the IMF blogs, the message was that more fiscal stimulus was acceptable and necessary, and rising public debt was tolerable while the COVID crisis is dealt with. This appears to be the opposite of the IMF-WB policy message after the Great Recession of 2008-9, when these international agencies called for balanced budgets and reduced debt levels. For example, the IMF backed the draconian conditions imposed on Greece during its debt crisis in 2012-15 that led to a 40% reduction in average living standards there.

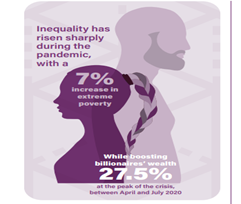

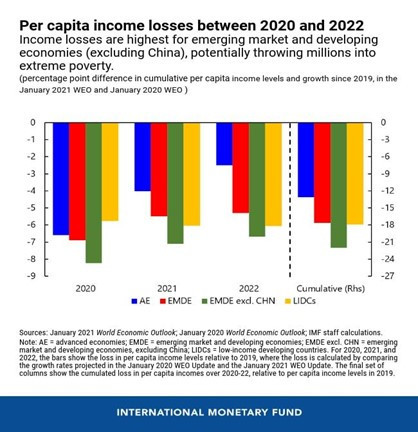

Now Georgieva’s IMF policy agenda sounds different. Global Policy Agenda “Policymakers must take the right actions now by giving everyone a fair shot. That includes a fair shot at accessing the vaccine, a fair shot at support during the recovery, and a fair shot at the future in terms of participating and benefitting from public investments in green, digital, health and education opportunities. “Economic fortunes are diverging dangerously. A small number of advanced and emerging market economies, led by the U.S. and China, are powering ahead—weaker and poorer countries are falling behind in this multi-speed recovery,” she said. “We also face extremely high uncertainty, especially over the impact of new virus strains and potential shifts in financial conditions. And there is the risk of further economic scarring from job losses, learning losses, bankruptcies, extreme poverty and hunger.”

What’s the answer now? The IMF proposes more debt relief, ie delaying repayments on existing loans made to poor countries and reducing interest costs through to 2022. At the Spring meeting, it was also announced that IMF funding based on Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) liquidity approved by the key member states would be increased by SDR500bn. So extra funding firepower.

But has the IMF-WB policy consensus really changed? Has the commitment to free market forces and fiscal stability in return to conditional loans to desperate countries really been dropped? The new consensus, if it really exists, is one of necessity, not change in ideology. Just as governments in the major capitalist economies have been forced to let the fiscal taps flow and inject humungous amounts of credit into the economy to avoid a total meltdown in the COVID slump, so the IMF-WB have seen the necessity to try and avoid a global debt disaster as governments of poor countries around the globe default on their debts to banks and other international financial institutions.

G20: the debt solution

Debt disaster with no escape

I have posted several times on the impending emerging market debt disaster and the IMF-WB is well aware of this. But when we dig down below the rhetoric and examine the terms that the IMF and the World Bank are still holding to on existing loans and future ones, little has changed. As a recent incisive report by the International Trade Union Confederation comments: “The “new” IMF says it has changed and supports a green and inclusive recovery but keeps acting a lot like the old IMF. …market fundamentalism still underpins the IMF’s growth narrative and advice”.

reforming_the_imf_for_a_resilient_recovery_v2.pdf (ituc-csi.org)

And the ITUC points out that the IMF ‘conditionalities’ were unsuccessful in helping poor countries out of the economic difficulties into sustained growth. On the contrary: “A close look at the IMF’s growth narrative shows that claims about the benefits of many preferred policies are overblown while the negative effects are well documented. Countries that have successfully moved up the income scale over the past decades did not follow the laissez-faire prescriptions of the IMF. Thus, it is not a track record of results but engrained market fundamentalism that underpins the IMF’s policy advice.”

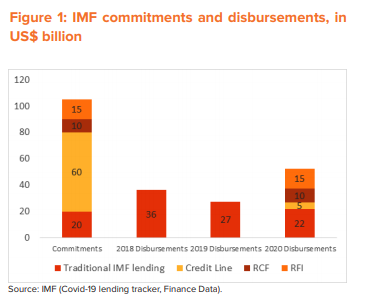

Indeed, emergency lending needed during the COVID slump has not really been significant in IMF largesse. “Out of the committed assistance, the largest part is in the form of pre-approved credit lines offered to Peru, Chile, and Colombia. Only Colombia has utilised its credit line thus far. The disbursements through rapid emergency lending, which comprise the support offered to almost 70 countries, only amount to about $30 billion. Combined with traditional lending arrangements, the IMF disbursed about $50 billion to 81 countries in 2020. Disbursements for 2020 are only slightly larger than in previous years, when IMF assistance went to a much smaller number of countries.”

When you look at the IMF reports on new lending the supposedly new calls for more public investment are only directed to countries that have “fiscal space” ie ones that can afford spending anyway. The ITUC comments “in general, the IMF continues to recommend fiscal consolidation as a pillar of a medium-term fiscal strategies once the crisis is over.” In a survey of IMF staff reports for 80 countries, the European Network for Debt and Development found that 72 countries forecast cuts to spending levels below their pre-pandemic baseline as early as 2021, with all 80 countries doing so by 2023. And these austerity plans were met with approval from Fund staff.

The ITUC analysis shows that the IMF still follows a ‘supply-side approach’ to economic growth that “focuses on creating ideal conditions to attract private sector investment. The Fund commonly states that the goal of its advice is to boost “confidence” and “competitiveness”, leaving the rest up to markets.” A study of conditionality in IMF loan agreements between 1985-2014 confirms this pattern and finds that while the number of conditions in loans fluctuated over time, their content was consistently in line with structural adjustment programmes comprised of structural reforms including labour market deregulation, along with fiscal consolidation.

IMF conditionality and development policy space, 1985-2014 (kentikelenis.net)

While the IMF and its advanced economy masters are allowing ‘debt relief’ and offering more funds, the cancelling of onerous debts already incurred by ‘global south’ economies engulfed in the pandemcic slump is not being offered. So if there is a new ‘consensus’ on international lending and economic support by multi-national agencies it sits on the surface of talking; when the walking begins, nothing has really changed.

April 10, 2021

Robert Mundell: nothing optimal

Noted neoclassical mainstream economist, Robert Mundell, has died at the age of 88 years. Mundell won a Nobel (Riksbank) prize in economics for his extension of general equilibrium theory as applied to Keynesian macroeconomics into the international arena. Whereas the neoclassical equilibrium version of Keynes’ macromodel (called ‘bastardised Keynesianism’ by Joan Robinson) described a ‘closed’ economy (i.e. no trade and cross border capital flows), Mundell and colleague Marcus Fleming developed an equilibrium model for an ‘open’ economy (that had international trade and cross-border money and capital flows).

Keynesian economics in the DSGE trap

The irony of the Mundell-Fleming equilibrium model is that it showed that there was no equilibrium possible! A capitalist economy cannot simultaneously maintain a stable or fixed exchange rate with other currencies, as well as free movement of capital across borders and then expect that monetary policy can be used to control the level of interest rates and the money supply in one economy. Mundell-Fleming found that an economy can only maintain two of the three options at the same time. This principle is frequently called the “Mundell–Fleming trilemma.”

For Marxist economics, this result is no surprise because capitalist economies do not tend to equilibrium as the neoclassical mainstream religiously believes. Capitalist economies, as they accumulate, tend to disequilibrium because of the anarchy of capitalist competition and the uneven development of capitals seeking profit. So any attempt to control one aspect of that disequilbrium will only increase disequilbrium elsewhere. If you have a bucket with three holes and only two stoppers, it just leaks faster out of the hole without one.

No national economy is an island, so when governments opt to try and manage their own monetary and fiscal policies, and at the same time, allow free movement of capital across borders, Mundell-Fleming told them that they had to stop trying to fix their currency rates and allow ‘floating currencies’. Unfortunately, floating currencies, given the disequilibrium of capitalist accumulation only leads to regular and recurring devaluations in countries with weak investment and trade balances and huge cross-border capital flows.

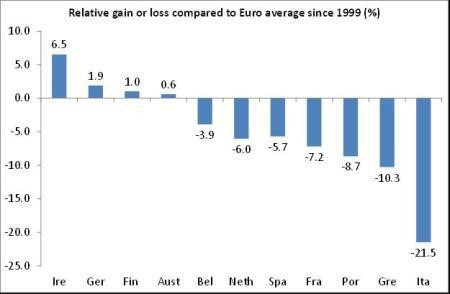

Canadian born Mundell also won his Nobel prize for his optimal currency union theory. This theory purported to show the conditions needed to ensure a stable currency union of several states that would allow the convergence in productivity levels and per capita income within a single currency union. Mundel was a great advocate of the setting-up of the euro, which he reckoned, with ‘free markets’ and ‘flexible labour’ alongside free capital movement, would mean that economies in the Eurozone could tend towards convergence and equilibrium. Also, the currency union would mean that rogue governments (like Greece) would no longer control monetary policy which would become the province of an ‘independent’ central bank (ECB).

Greece: crossing the red lines

Again ironically, the optimal currency union theory proved not be optimal at all! Instead of economies converging towards equilibrium with higher incomes per capita, capitalism operates unevenly and tends to disequilibrium and divergence. As a result, in the Euro single currency area, since 1999 productivity levels between the northern core and southern periphery have widened, not narrowed.

See my posts here. https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2018/03/08/unam-2-europes-single-currency/

20 years of the euro – part one: has it been a success?

Mundell’s equilibrium theories proved the opposite of his expectations. They show disequilibrium not equilibrium as the tendency; they show why national governments cannot manage their own economies successfully with fiscal and monetary policy; and why capitalist currency unions do not function ‘optimally’.

In a way, Mundell recognised this, by eventually advocating a return to ‘managed’ exchange rates, or the gold standard (fixing currency rates to the price of gold); and, of course, the ultimate solution: a world currency. He feared stagnation in capitalist economies and so advocated the classic ‘supply-side’ solution of cutting corporate and personal taxes to boost private investment and spending. Under capitalism, however, none of these ‘solutions’ can work or be achieved.

April 9, 2021

Financial fiction part two: the new ones (SPACs, NFTs, cryptocurrencies)

In my last post I discussed recent financial engineering and swindles that are traditional to the accumulation of and speculation in what Marx called fictitious capital, ie financial assets like bonds, stocks, property, credit and so-called derivatives of these.

Financial fictions: the old ones

Finance capital is ever-ingenious in inventing new ways of speculation and swindles. In the past we have had the dot.com boom when the stock prices of many internet start-ups exploded upwards, only to crash when the profits of these companies did not materialise and the cost of borrowing to speculate rose. That was in 2000 and followed by a mild recession in 2001.

Then we had the huge credit boom in house prices, mortgages and the securitised mortgage packages and their derivatives that fuelled a huge property and stock market boom that collapsed into the Global Financial Crash of 2008 and the subsequent Great Recession. That was followed by a massive injection of central bank money with low to zero interest rates and ‘quantitative easing’ leading to a further rise in stock and bond markets up to record highs. The COVID slump only led central banks to doubling-down on ‘quantitative easing’ to keep the prices of financial assets rising, while the ‘real economy’ based on the profitability and investment in productive assets stagnated.

In this 21st century world of easy money borrowing, there have been a spate of new fictions in the casino world of financial speculation.

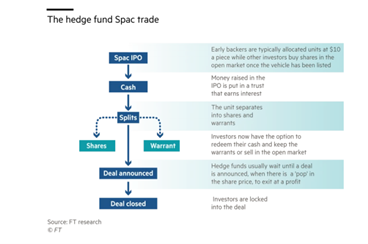

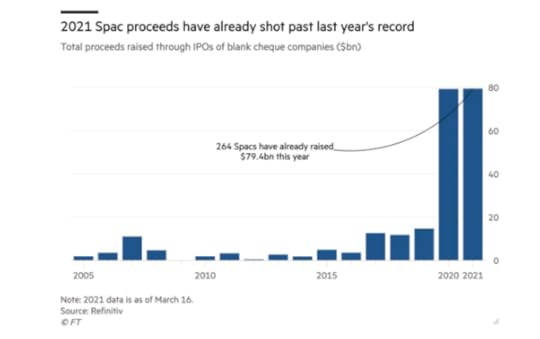

First, there are SPACS, Special Purpose Acquisition Vehicles. These are so-called “blank cheque” companies e. banks and other hedge funds invest in a SPAC, which owns nothing, but promises investors that the SPAC will buy a privately-owned company, then take it to the stock market in what is called an Initial Public Offering (selling shares to the public). If the IPO leads to higher price than the investment in the SPAC, everybody makes a profit.

SPACs have taken Wall Street by storm and become a favourite investment among hedge fund managers. As one SPAC explained, we have an “inherently investor-friendly structure” with little downside. In the US, which accounts for the bulk of SPAC activity, 235 vehicles have raised $72bn so far this year, according to Refinitiv. But is there ‘little downside’? Supposedly there is little risk of losing the original investment because cash is put into a trust that invests in US treasuries and shareholders can ask for their money back at any point. But there is a potential to make lofty returns come from a unique quirk in the SPAC, which splits into shares and ‘warrants’ (options to buy shares) shortly after the structure starts trading. And here there is substantial risk that things will go wrong.

A warrant, typically worth only a fraction of a share, acts as a sweetener for early backers, who can redeem their investment while keeping hold of the warrant. When the SPAC finds a company to acquire, the warrants convert to relatively inexpensive stakes in the new company. But those who who did not take warrants but opted for a stake in the merged company (mainly small investors), bear the risk of both a potentially bad deal and significant dilution compared to the free warrants handed out to early backers.

And quite often it is a bad deal. While the hedge funds buy the ‘warrants’ at a fraction of the SPAC share price and get out before the SPAC acquisition is completed, small ‘retail’ investors stay on the for the full deal and find that the acquisition IPO price drops very quickly, leaving them with significant losses. The result is that small investors provide the money for the rich wide boys to take. Nevertheless, while money is cheap and the stock market booms, the small-time better will go on hoping to make a killing.

Then there are NFTs, or ‘non-fungible tokens’. What the hell are these, you might say? NFTs are digital financial assets stored on blockchains (digital codes). You can convert anything into an NFT to try and sell it. Christies has already auctioned an NFT (digitally coded) artwork for $70m. An Oscar nominated movie has been released as an NFT (digital code) and so on. But what is being sold is just one unique, blockchained (digital coded) representation of the artwork, not the actual thing itself. It’s the ultimate derivative: a digital code derived from an object or even a person, but with no rights of ownership. So what’s the point? None really – it’s just a fad and the buyer of the NFT hopes that it can be sold on to another idiot for a profit.

A particular negative of the NFT craze is that encoding artwork or an idea onto a blockchain involves complex computations that are highly energy intensive. In six months, a single NFT by one crypto artist consumed electricity equivalent to an EU citizen’s average energy consumption over 77 years. This naturally results in a significant carbon footprint.

And this is an issue that applies to blockchain technology more generally. For example, the original cryptocurrency Bitcoin (BTC) has an estimated annual energy consumption in the range equivalent to about 0.45 percent of the world’s entire electricity production.

And that brings me to the saga of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin. I wrote on blockchains and crypto craze over three years ago. I argued then that Bitcoin aims at reducing transaction costs in internet payments and completely eliminating the need for financial intermediaries ie banks. But I doubted that such digital currencies could replace existing fiat currencies and become widely used in daily transactions.

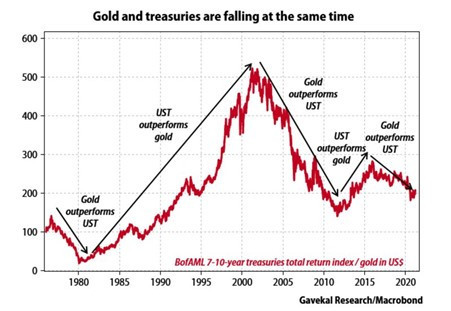

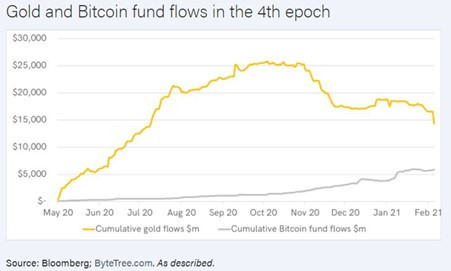

Since then, the price of bitcoin in fiat currencies like the dollar has violently fluctuated but more recently has rocketed to stratospheric heights as cheap money and low inflation have pushed down the value of the main reserve and store of currency, the US dollar. Whereas gold used to be the alternative store of value to the dollar, now it seems that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are taking over as the speculative money asset. Why? Well, most gold is the vaults of central banks and so the price is subject not only to the supply from gold mines but also the policy decisions of government-controlled banks. Instead, Bitcoin has a clearly defined amount to digital supply and through blockchains, it can be mined and transacted without government controls.

In the current fantasy world of casino financial investment, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies seem more attractive to currency speculators than even gold. And so the crypto boom continues. For example, Coinbase Global Inc, the largest US cryptocurrency exchange, is now valued at around $68 billion, compared to just $8 billion in October 2018. The company now has more than 43 million users in more than 100 countries.

But cryptocurrencies are no closer to achieving acceptance as a means of exchange. Bitcoin’s value is not backed by any government guarantees, by definition. It is backed just by ‘code’ and the consensus that exists among its key ‘miners’ and holders. As with fiat currencies, where there is no physical commodity that has intrinsic value in the labour time to produce it, the crypto currency depends on trust of the users. And actually that trust for cryptocurrencies varies with its price relative to the fiat currency, the dollar. Its price is measured in dollars or in what is called a ‘stable coin’ tied to the dollar.

Indeed, while the cryptocraze has exploded, the US dollar has entrenched itself ever more firmly as the world’s premier settlement currency (67% of all settlements, followed by the euro, the yen and yuan).

Bitcoin is no nearer universal acceptance than it was when it started. So while cryptocurrencies have increasingly become part of speculative digital finance, I still don’t think they will replace fiat currencies, where the supply is controlled by central banks and governments as the main means of exchange. They will remain on the micro-periphery of the spectrum of digital moneys, just as Esperanto has done as a universal global language against the might of imperialist English, Spanish and Chinese.

Moreover, there are already rivals to cryptocurrencies that carry the backing of governments: central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). CBDCs have been discussed for years as an alternative to cash as many economies have witnessed a slump in physical money being used in transactions. Cash accounted for only 20% of payments in China – the world’s second largest economy in 2018, according to research published by the Bundesbank in 2019. This week, China became the first major economy to create a blockchain-based digital version of its currency, the cyber yuan, to be used in transactions. Sweden’s central bank, the Riksbank revealed this week that its current pilot project will take at least one more year to be ready for the e-krona.

The US is more reluctant because American finance has the dollar as the world’s top currency. This week, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said “that there’s no hurry to develop a central bank digital currency.” Having trashed cryptocurrencies as “highly volatile and therefore not really useful stores of value and not backed by anything,” Powell went on “It’s more a speculative asset that’s essentially a substitute for gold rather than for the dollar.” Even so, the Boston Fed last year entered into a partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on a multiyear study into developing a central bank digital currency. But the work is expected to take two to three years.

These CBDCs in theory provide a seamless and trustworthy way of doing digital transactions more or less instantaneously and as they ar backed by government, they make them attractive compared to gold, fiat currencies and crypto coinage. But they also reduce the freedom of individuals to control their own ‘cash’ and they open the doors of personal financial activities to governments, supposedly reducing corruption, but also putting people’s livelihoods even more in the grip of governments.

In the last 20 years, financial fictions have been increasingly digitalised. High frequency financial transactions have been superseded by digital coding. But these technological developments have mainly been used to increase speculation in the financial casino, leaving regulators behind in the wash. When the financial markets go belly up, which they eventually will, the digital damage will be exposed.

Blockchains and the crypto craze

April 3, 2021

Financial fictions: the old ones

I must declare an interest. In days of old, many moons ago, I worked for an investment consultancy that advised Bill Hwang, the owner of Archegos, the ‘family office’ hedge fund that recently collapsed leaving $20bn owed to two big banks, Credit Suisse and Nomura.

Bill Hwang

Hwang was then a ‘Tiger cub’, someone that veteran hedge fund manager, Julian Robertson of the pioneering Tiger hedge fund showed favour on with ‘seed’ investment capital. After leaving Tiger, Hwang struck out on his own back in 2001 to great success. But then there was the first scandal when in 2013 Hwang was barred from the US investment business. Authorities alleged that, as part of an insider-trading scheme, his Tiger Asia Management hedge fund had violated promises it made to some of the world’s most powerful investment banks.

But no matter, Hwang, a pastor’s son and deeply religious, soon re-invented himself to do God’s work’ in financial speculation. Hwang has credited his faith with helping him get through the difficult times. After Tiger Asia’s demise, he said that he had listened to recordings of the Bible for hours.

Doing God’s work again

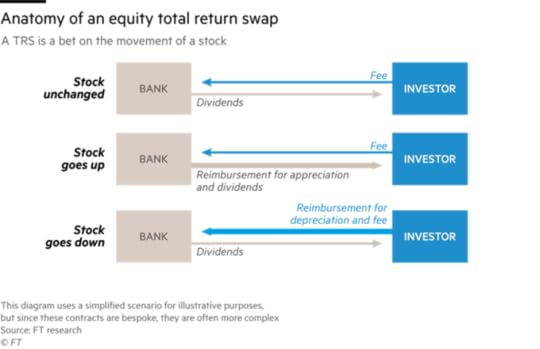

On getting God’s word, he set up what is called a ‘family office’, Archegos Capital Management, and eventually built up its trading positions running into the tens of billions of dollars with Wall Street banks, including some of the ones his old firm was accused of cheating. Hwang’s downfall came last week when he was unable to meet margin calls on derivatives trades, known as equity swaps, that he had struck with several investment banks. These instruments gave speculators the option to gain from stock positions without having to own the underlying shares himself. As Marx put it some 150 years ago in Capital, “Profit can be made purely from trading in a variety of financial claims existing only on paper…. Indeed, profit can be made by using only borrowed capital to engage in (speculative) trade, not backed up by any tangible asset.”

It seems that Hwang had borrowed billions of swaps from different banks to maximise his ‘leverage’ in betting on the stock market, without telling each bank how much he had borrowed. The Archegos Capital debacle has exposed the hidden risks of the lucrative but opaque equity derivatives business through which banks empower hedge funds to make outsize bets on stocks and related assets. “We have a fundamental problem in the reporting of holdings of synthetic equity that is not secret and is not new,” said Tyler Gellasch, a former SEC official and executive director of Healthy Markets, an advocacy group. “If there are five different banks providing financing to a single client, each bank may not know it, and may instead think it can sell its exposure to another bank if they run into trouble — but they can’t, because those banks are already exposed.”

When Archegos’ bets went south, Hwang could not meet his commitments to these banks and several were left holding the baby. As Marx said in Capital, “In every stock-jobbing swindle everyone knows that some time or other the crash must come, but everyone hopes that it may fall on the head of his neighbour, after he himself has caught the shower of gold and placed it in safety.” In this case, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley got out of Whang first and Credit Suisse and Nomura did not.

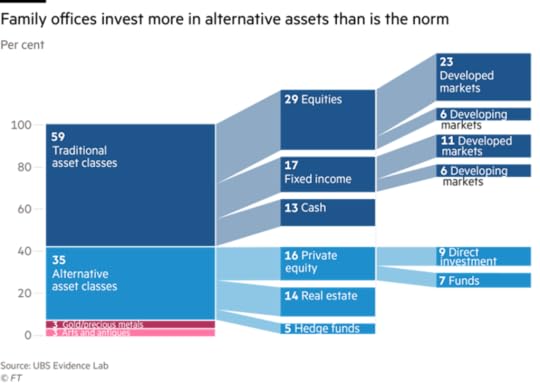

The Archegos story is an old-style financial meltdown. Yes, the financial instrument involved, equity swap derivatives, is a new form of financial asset (or what Marx called ‘fictitious capital’), invented in the last 25 years. And the setting up of a ‘family office’, which is not subject to the same financial regulations (such as they are) for modern hedge funds, has become a new way of avoiding scrutiny. Hedge funds are speculative financial vehicles basically for betting (with mostly borrowed money) on the movement in the prices of stocks, bonds, commodities, and on the ‘derivatives’ of these ad infinitum. Betting companies when advertising on TV must keep saying ‘please bet responsibly’, as the regulators demand (with little effect, of course). But with ‘family offices’, usually funded by mega-rich global family fortunes, it’s even worse. There are no controls or warnings at all.

In a report issued a year ago, business school Insead noted that the number of single family offices had grown by 38 per cent between 2017 and 2019, to reach more than 7,000. Assets under management stood at some $5.9tn in 2019, the report estimated. That compares with $3.6tn in the global hedge fund industry, according to HFR. These ‘family offices’ can do what they want with their assets, without regulation. Rich families place a growing share of their wealth in these types of structures. On average, they control assets worth $1.6bn apiece, according to another 2020 study by UBS, and a handful can stretch into hundreds of billions of dollars. Typically, each family office has two or three offices, often in hubs like Singapore, Luxembourg and London. Chief executives are paid something in the order of $335,000 a year, according to the Insead report.

In the Archegos example, it seems that only the mega investment banks have suffered and not the man and woman in the street. So we may have no sympathy for them. But indirectly, we all get hit because banks are using funds, also often borrowed, to speculate in this way rather than providing a proper banking service for people. Banks lend with strict conditions on mortgages or loans to small businesses, but it seems with no control at all to the likes of Archegos, where banks can make big money if all goes well. But as one equity derivatives trader put it, equity total return swaps are “a classic case of picking up nickels in front of a steamroller… You can pick up those nickels all day. That steamroller moves pretty slowly. But if you trip, boy, do you get run over.”

In the case of the Woodford financial scandal in the UK, there has been a direct hit to people in the ‘real world’. It is more than 18 months since the implosion of Neil Woodford’s investment fund business sparked the biggest British investment scandal for a decade. More than 300,000 individuals who entrusted their hard-earned savings to the famed ‘stock picker’ are still waiting to recoup the money. Many have had to delay retirement after nursing tens of thousands of pounds of losses. The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority, the supposed financial regulator, failed miserably to spot the Woodford crash. Woodford was once lauded as “the man who can’t stop making money” and “Britain’s Warren Buffett”. But great stock speculator was forced to suspend trading in his £3.7bn flagship Equity Income fund after failing to cope with a surge of investors reclaiming their cash. Investors stand to lose up to £1bn — more than a quarter of the fund’s value at suspension.

Neil Woodford

Then there is Greensill. This was a ‘fintech’ bank set up by former Morgan Stanley and Citibank executive, Lex Greensill. It specialised in ‘supply-chain financing”, ie ‘reverse factoring’ where the buyer chooses invoices that the financing ‘factor’ (Greensill) will pay for them early – that’s the opposite of factoring where the supplier chooses the invoices that it wants paid early by the factor. Supply chain financing speeds up transactions in a fast moving global market. But ti puts the burden of payment on the factor. Lex Greensill’s revolutionary innovation was to go one step realise and package these invoices into investment funds to be sold to banks — much as the big investment banks turned subprime mortgages into securities before the 2008 financial crisis.

Greensill also took deposits to invest in its apparently lucrative operation from companies and local councils, offering high rates and finding funds and loans for clients when big banks would not lend. It sprouted fast and took on exposure in loans worth $143bn by 2019 with ten million customers. In particular, it provided funding for metals magnate Sanjeev Gupta, who owns the third biggest steel compnay in the UK.

Sanjeev Gupta

But Greenshill went bust because it could no longer find sufficient financing for its ever-expanding loan commitments and high deposit rates. Gupta’s steel workers could now lose their jobs and German local councils could take a $500m hit.

The scandal is still unfolding as it seems Greensill never had sufficient funding to take on the huge liabilities (debts) that the likes of Gupta’s steel companies had. Worse, it also seems that Gupta’s companies were using invoices to raise loans from Greensill that were issued by other parts of the corporate complex – in other words, claiming potential receipts as collateral to Greensill that were really debts owed by other parts of the company! Meanwhile Gupta’s group company was receiving state-backed emergency Covid loans to tide its businesses over during the pandemic. Thus Gupta completed the purchase of a £42m London townhouse. Gupta is now believed to be in Dubai. The UK government under Boris Johnson may well be forced to ‘nationalise’ Gupta’s Liberty Steel to save the business. It has drawn up a contingency plan to run Liberty Steel using public money while searching for a buyer. So this financial meltdown will be resolved with the British public paying up, similar to how the Treasury supported British Steel in 2019 at a cost to taxpayers of nearly £600m.

So nothing has changed from when Marx wrote about “a new financial aristocracy, a new variety of parasites in the shape of promoters, speculators and simply nominal directors; a whole system of swindling and cheating by means of corporation promotion, stock issuance, and stock speculation.”

In the rise of finance, “All standards of measurement, all excuses more or less still justified under capitalist production, disappear.” …. since property here exists in the form of stock, its movement and transfer become purely a result of gambling on the stock exchange, where the little fish are swallowed by the sharks and the lambs by the stock-exchange wolves.

What is new are the forms of these swindles. There has been a huge rise in what is called ‘shadow banking’, ie lending and funding by non-banks (NBFI), which has expanded hugely since the end of the GFC and is now nearly half of all financial ‘assets’. Our new financial moralist, former Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, warns that : “more than £20 trillion of assets are held in funds that promise daily liquidity to investors despite investing in potentially illiquid underlying assets.” Carney reckons that funds like those run by the disgraced manager Neil Woodford “are built on a lie and could pose a threat to the global economy. These funds are holding assets that are hard to sell in a hurry – while allowing investors to take their money out on demand – are a mounting risk to the financial system.”

Mark Carney: value or price?

https://www.fsb.org/…/global-monitoring-report-on-non…/

Back to Marx here. “The two characteristics immanent in the credit system are, on the one hand, to develop the incentive of capitalist production, from enrichment through exploitation of the labour of others, to the purest and most colossal form of gambling and swindling.” So the finance sector carries on just as before, engaging in speculation and regulators cannot and do not stop them.

Regulation does not work

As global stock markets hit new all-time highs and central banks continue to provide almost unlimited supplies of credit money into the financial sector, in the second part of this discussion of financial meltdowns, I shall review some new financial fictions and their inevitable meltdowns.

March 28, 2021

The rise of capitalism and the productivity of labour

In my view, there are two great scientific discoveries made by Marx and Engels: the materialist conception of history and the law of value under capitalism; in particular, the existence of surplus value in capitalist accumulation. The materialist conception of history asserts that the material conditions of a society’s mode of production and the social classes that emerge in that mode of production ultimately determine a society’s relations and ideology. As Marx said in the preface to his 1859 book A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy: “The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.”

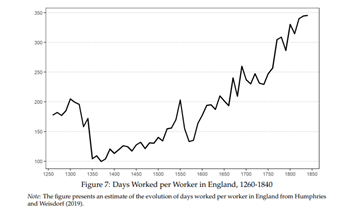

That general view has been vindicated many times in studies of the economic and political history of human organisation. That is particularly the case in explaining the rise of capitalism to become the dominant mode of production. Now there is new study that adds yet more support for the materialist conception of history. Three scholars at Berkeley and Columbia Universities have published a paper, When Did Growth Begin? New Estimates of Productivity Growth in England from 1250 to 1870. https://eml.berkeley.edu/~jsteinsson/papers/malthus.pdf

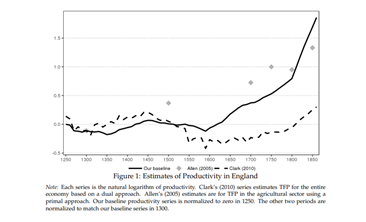

They attempt to measure when productivity growth (output per worker or worker hours) really took off in England, one of the first countries where the capitalist mode production became dominant. They find that there was hardly any growth in productivity before 1600. But productivity started to take off well before the so-called ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 when England became a ‘constitutional monarchy’ and the political rule of the merchants and capitalist landowners was established. These scholars find that, from about 1600 to 1810, there was a modest rise of the productivity of the labour force in England of about 4% in each decade (so 0.4% a year), but after 1810 with the industrialisation of Britain, there was a rapid acceleration of productivity growth to about 18% every decade (or 1.8% a year). The move from agricultural capitalism of the 17th century to industrial capitalism transformed the productivity of labour.

The authors comment: “our evidence helps distinguish between theories of why growth began. In particular, our findings support the idea that broad-based economic change preceded the bourgeois institutional reforms of 17th century England and may have contributed to causing them.” In other words, it was the change in the mode of production and the social classes that came first; the political changes came later.

As the authors go on to say, “an important debate regarding the onset of growth is whether economic change drove political and institutional change as Marx famously argued or whether political and institutional change kick-started economic growth”. The authors don’t want to accept Marx’s conception outright and seek to argue that “reality is likely more complex than either polar view.” But they cannot escape their own results: that productivity growth began almost a century before the Glorious Revolution and well before the English Civil War. And “this supports the Marxist view that economic change contributed importantly to 17th century institutional change in England.”

The other interesting aspect of the paper is that the authors try to measure the impact of population growth on productivity and wages. In the early 19th century, Thomas Malthus argued that it was impossible for productivity growth to rise sufficiently to enable workers to increase their real incomes, because higher incomes would lead to increased births and eventually over-population, scarcity of food and famines etc, then reducing the population and incomes again.

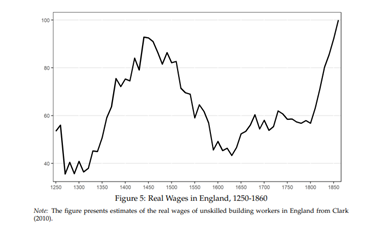

The authors note that before 1600, there is evidence to support the Malthusian case. The period from 1300 to 1450 was a period of frequent plagues — the most famous being the Black Death of 1348. Over this period, the population of England fell by a factor of two resulting in a sharp drop in labour supply. Over this same period, real wages rose substantially. Then from 1450 to 1600, the population (and labour supply) recovered and real wages fell. In 1630, the English economy was back to almost exactly the same point it was at in 1300.

The reason that the Malthusian argument has validity before 1600 is that there was little or no productivity growth; so livelihoods were determined by labour supply and wages alone. Pre-capitalist England was a stagnant, stationary economy in terms of the productivity of labour. But so was the impact of the Malthusian over-population theory. The authors found that Malthusian population dynamics were very slow: a doubling of real incomes led to a 6 percentage point per decade (0.6% a year) increase in population growth. That implied that it took 150 years for a rise in real incomes to drive up population sufficiently to cause a reversal in income growth.

But once capitalism appears on the scene, the drive for profit by capitalist landowners and trading merchants encourages the use of new agricultural techniques and technology and the expansion of trade. Then productivity growth takes off at a rate increasingly fast enough to overcome the slow impact of Malthusian ‘overpopulation’. Indeed, with industrial capitalism after 1800, the growth in productivity is 28 times higher than the very slow negative impact of rising population on real incomes.

Thomas Malthus

This confirms the view of Engels when he wrote: “For us the matter is easy to explain. The productive power at mankind’s disposal is immeasurable. The productivity of the soil can be increased ad infinitum by the application of capital, labour and science.” Umrisse 1842

https://www.lulu.com/en/gb/shop/michael-roberts/engels-200/paperback/product-y9pzdr.html?page=1&pageSize=4Before capitalism, feudal societies stumbled along with their economies ravaged by plagues and climate. For example, the Black Death of 1348 engulfed English society for more than a year, claiming about 25% of the population. For three centuries after the Black Death, the plague would reappear every few decades and wipe out a significant share of the population each time. So real wages in England were mainly affected by these population changes and the consequent size of the labour force (if, as argued above, at a very slow rate).

But under capitalism, productivity rose sharply and the level of real wages was no longer determined by the weather or pandemics but by the class struggle over the production and distribution of the value and surplus value created in capitalist production in agriculture and industry. One of the features of the rise of capitalism from 1600 that the authors point out is the increase in the working day and working year – another confirmation of Marx’s analysis of exploitation under capitalism.

The authors note that as capitalism started to move from agricultural production to industry, in the latter half of the 18th century, real wages in England fell slightly despite substantial productivity growth. They cite one potential explanation, namely “Engel’s Pause,” i.e., the idea that the lion’s share of the gains from early industrialization went to capitalists as opposed to labourers.

Engels’ pause and the condition of the working class in England

The authors are reluctant to accept that Engels was right, preferring a Malthusian explanation in the late 18th century (having just rejected it). Moreover, they think real wages started to grow as early as 1810, before the period of the 1820-1840 cited by Engels as a ‘pause’. But anyway, we can see that the gap between productivity and real wages widened sharply from the beginning of industrial capitalism to now. Surplus value (the value of unpaid labour) rocketed through the early 19th century.

Most important, the study refutes the ‘Whig interpretation of history’, namely human ‘civilisation’ is one of gradual progress with changes coming from wiser ideas and political forms constructed by clever people. Instead, the evidence of productivity growth in England shows “sharp and sizable shifts in average growth” supporting the notion that “something changed.” i.e., that the transition from stagnation to growth was more than a steady process of very gradually increased growth.” On the gradual Whig interpretation, the authors conclude that “the results do not support this view of history.”

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334831075_The_Whig_interpretation_of_history

Also, the study shows that, as sustained productivity growth began in England substantially before the Glorious Revolution of 1688, it was not the change in political institutions that led to economic growth. On the contrary, it was the change in economic relations that led to productivity growth and then political change. “While the institutional changes associated with the Glorious Revolution may well have been important for growth, our results contradict the view that these events preceded the onset of growth in England.”

As Engels put it succinctly: “The materialist conception of history starts from the proposition that the production of the means to support human life and, next to production, the exchange of things produced, is the basis of all social structure; that in every society that has appeared in history, the manner in which wealth is distributed and society divided into classes or orders is dependent upon what is produced, how it is produced, and how the products are exchanged. From this point of view, the final causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men’s brains, not in men’s better insights into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange.”

The authors cannot avoid reaching a similar conclusion. As they say: “Marx stressed the transition from feudalism to capitalism. He argued that after the disappearance of serfdom in the 14th century, English peasants were expelled from their land through the enclosure movement. That spoliation inaugurated a new mode of production: one where workers did not own the means of production, and could only subsist on wage labour. This proletariat was ripe for exploitation by a new class of capitalist farmers and industrialists. In that process, political revolutions were a decisive step in securing the rise of the bourgeoisie. To triumph, capitalism needed to break the remaining shackles of feudalism…. Our findings lend some support to the Marxist view in that we estimate that the onset of growth preceded both the Glorious Revolution and the English Civil War (1642-1651). This timing of the onset of growth supports the view that economic change propelled history forward and drove political and ideological change.”

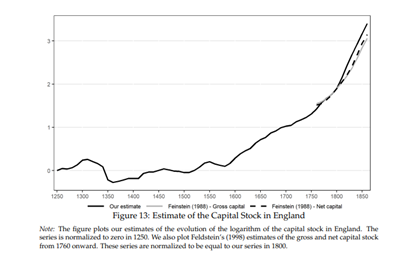

The development of capitalism in agriculture and in trade laid the basis for the introduction of industrial technology that led to the so-called industrial revolution and industrial capitalism. The Industrial Revolution occurred in Britain around 1800 because “innovation was uniquely profitable then and there”. As real wages rose, there was an incentive to exploit the raw materials necessary for labour saving technologies in textiles such as the spinning jenny, water frame, and mule, as well as coal burning technologies such as the steam engine and coke smelting furnace. Labour productivity exploded upwards. There was staggering rise in investment in means of production relative to labour. According to the authors, from 1600 to 1860, the capital stock in England grew by a factor of five, or 8% per decade.

Industrial capitalism had arrived, and along with rising productivity came increased exploitation of labour and the ideology of ‘political economy’ and bourgeois institutions of rule.

March 21, 2021

The sugar rush economy

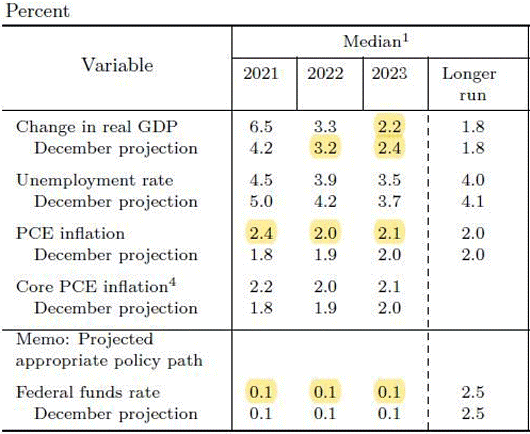

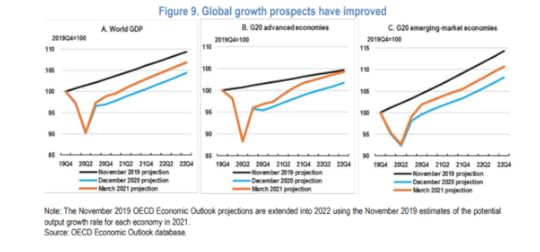

Last week the US Federal Reserve raised its growth forecasts for the US economy for this year and next. Fed officials now reckon the US economy with expand in real terms by 6.5%, the fastest pace since 1984, a few years after the slump of 1980-2. This is a significant rise from the Fed’s previous forecast. Also, the unemployment rate is expected to drop to just 4.5% by year-end, while the inflation rate ticks up to 2.2%, above the official target rate set by the Fed.

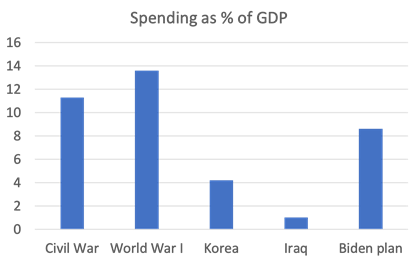

Driving this new optimism on growth is the fast roll-out of vaccines to protect Americans from COVID-19 plus the huge fiscal stimulus package put through Congress that most mainstream forecasters expect to add at least 1% point to economic growth and bring down unemployment.

But Fed chair Jay Powell made it clear that the Fed had no intention of raising its target interest rate until 2023 at the earliest even if inflation accelerates. He wants to see the unemployment rate drop to 3.5% and inflation averaging 2% or so. He would tolerate the economy “running hot” until that happens because he reckons that any rise in inflation would be transitory.

The implication of Powell’s view was that the US economy was going to have a ‘sugar rush’ from the fiscal stimulus and from the ‘pent-up’ demand of consumers with cash savings ready to spend on restaurants, leisure, travel etc once the pandemic restrictions were relaxed. But as every parent knows, giving a child too much sugar leads to a rush of energy. And then comes the letdown and sleep. That is what Powell worries about, namely that after this burst of energy on the ‘sugar high’ of government paychecks and restaurants meals, the US economy will slip back into the low growth trajectory that applied before the pandemic slump.

Powell is also concerned about a potential relapse in the fight against the virus and expects fiscal support from the stimulus starting to fade next year and worries that the labour market will continue to struggle. So he expects ‘core inflation’ (excluding food and energy prices) will fall back to 2 per cent next year and 2.1 per cent in 2023. So no inflationary spiral.

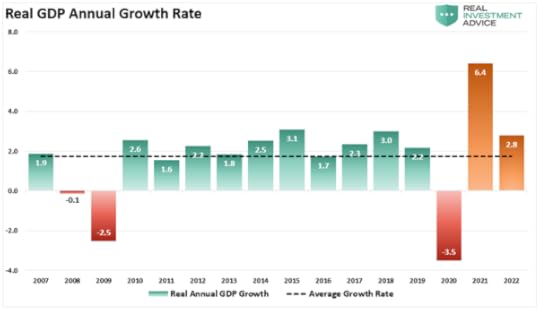

It is significant that the long-term growth forecast by the Fed is just 1.8% a year, which is hardly any higher than average real GDP growth of 1.7% since the end of the Great Recession and before the pandemic.

This implies that the Fed reckons the US economy is going to drop back to the rate of growth experienced in the Long Depression since 2009, and the ‘sugar rush’ is just that.

What this also implies is that contrary to the views of the Keynesians, the multiplier effect of the fiscal stimulus will soon dissipate and then the US economy will depend, not on consumers’ pent-up demand but on the willingness and ability of the capitalist sector to invest. It’s investment not consumer demand that will matter in sustaining any significant recovery; not sugar treats but on new energy in the form of new surplus value (to use Marx’s term for profits).

Financial investors are less convinced that Powell is right. After all, getting the US economy to achieve a 3.5% unemployment rate and 2% inflation has been achieved only twice since 1960! So ‘inflation expectations’ among investors have been rising, suggesting an inflation rate of 2.6% on a five-year view. As a result, US government bond yields have also risen significantly, as bond yields suffer in real terms if inflation rises.

The view that the US economy may ‘overheat’ has been argued by Larry Summers, the arch-Keynesian of several administrations. He fears that the fiscal and monetary stimulus will lead to ‘excess demand’ and so drive up prices across the board, eventually forcing the Fed to raise interest rates. Summers argues this, because this time last year, he was telling the world that the COVID pandemic would have little long-lasting impact and the economy would bounce back once it was over, just like seaside towns go to sleep in the winter and then wake up when the tourist season starts. He seems to think that the US economy will revive of its own accord and fiscal stimulus is unnecessary. But the experience of the last year has been much longer and more damaging than a ‘winter break’.

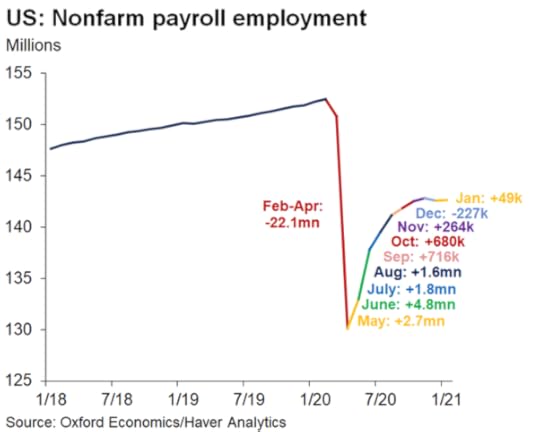

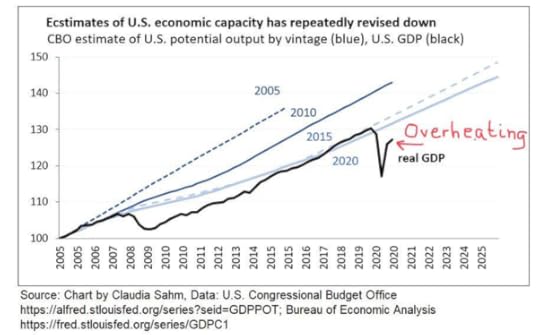

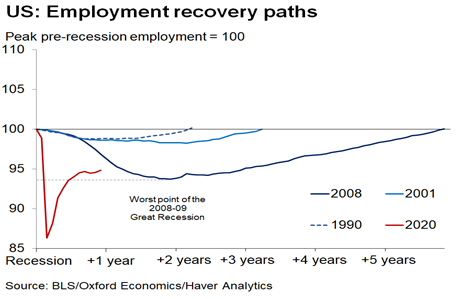

At the other end of the argument, Summers has been scathingly attacked by post-Keynesians and leftists who reckon there is no danger of ‘overheating’ and rising inflation, because there is plenty of ‘slack’ in the economy ie workers needing jobs and businesses needing to start up. But what this view ignores is the ‘hysteresis’ effect on the economy from the pandemic slump; namely that many workers have been forced to leave the workforce for good over the last year and many small to medium businesses will never return. The Long Depression has seen a steady reduction in estimates of US productive capacity.

That means the room for economic recovery is reduced unless investment in new means of production and employment rises significantly. So there could be ‘overheating’ and higher inflation, not because of pent-up consumer demand but because of weak productive capacity – not ‘too much demand’ but ‘not enough supply’.

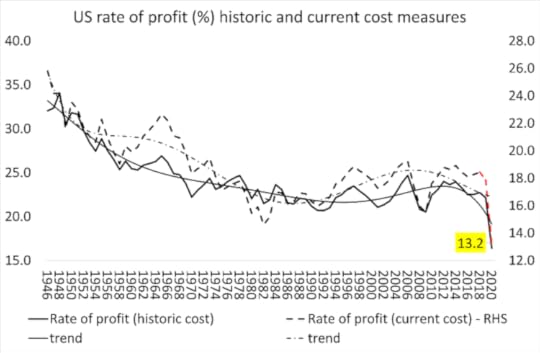

What the last ten years has shown is that business investment growth has slowed as the profitability of productive capital has fallen in the US. Cash-rich companies and investors, borrowing at record-low interest rates, have preferred to speculate in financial assets. The huge tally of bailouts by central banks and cuts in corporate taxation have been spent on driving the stock and bond markets to all-time highs while the ‘real economy’ has stagnated. The bottom 80% of American households, who drive the bulk of personal consumption expenditures (PCE), continue to struggle to make ends meet.

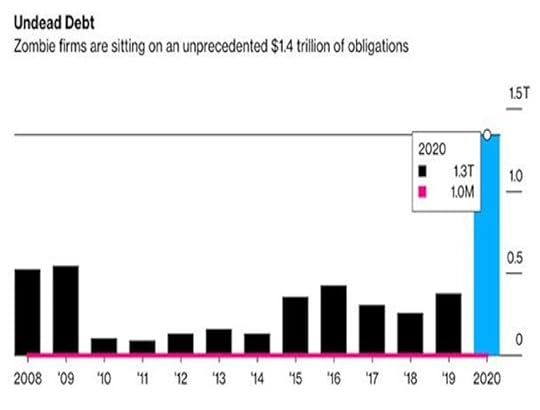

And down the road, rising debt cannot be ignored. And it is not so much public sector debt, which in the US is now well above 100% of GDP; more important is corporate debt. If interest rates for firms do start to rise because of increased inflation, then debt servicing costs for a whole swathe of so-called ‘zombie’ companies will become an excessive burden and bankruptcies will ensue.

According to Bloomberg, In the US, almost 200 big corporations have joined the ranks of so-called zombie firms since the onset of the pandemic and now account for 20% of top 3000 largest publicly-traded companies. With debts of $1.36 trillion. That’s 527 of the 3000 companies didn’t earn enough to meet their interest payments!

As before, the Fed is caught. If it does not end the monetary largesse at some point, then inflation could rise which will eat into real incomes and drive up corporate debt costs. But if it acts to curb inflation, it could provoke a stock market crash and corporate bankruptcies. That is what happens when an economy is in ‘stagflation’: namely rising inflation and low growth.

A stock market crash caused by rising interest rates does not always lead to an economic recession. Mainstream economist Paul Samuelson used to joke that the stock market has predicted 12 out of the last 9 recessions. Indeed, as Marx argued, financial crashes have a law of their own and do not always coincide with ‘commercial crises’.

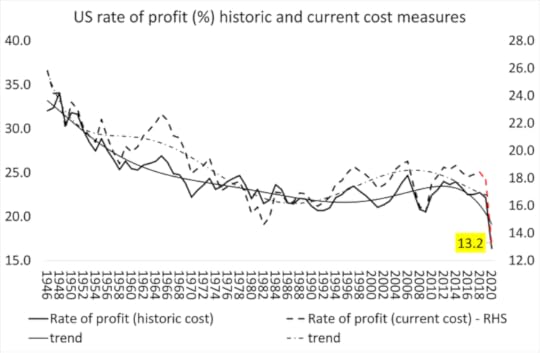

For example, the very sharp fall in stock prices in 1987 did not lead to economic recession and prices recovered quickly. The reason then was that the profitability of capital in the major economies had been rising for over five years and was at a relatively high level in 1987 and profitability continued to rise for another decade. But that is not the situation now. The profitability of capital is near all-time lows and even a recovery in 2021 and 2022 will not put levels back to that before 1997 or 2006. And corporate debt has never been higher historically.

These underlying forces suggest that the ‘sugar rush’ will be just that – a short burst followed by slumber at best.

March 18, 2021

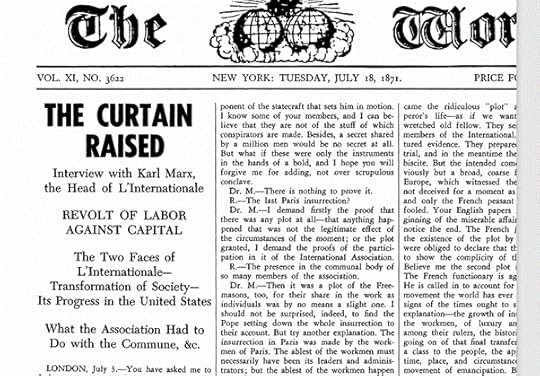

Paris Commune 150: the economics

Today is the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the Paris Commune. The Commune (Council) was formed as result of what should be considered the first uprising and revolution led by the working class in history. This new class was the product of the industrial revolution in the capitalist mode of production that Marx and Engels first spoke of most prominently in the Manifesto of the Communist Party published in March 1848.

Before the Paris Commune, revolutions in Europe and North America had been to overthrow feudal monarchs and eventually put the capitalist class into political power. While socialism as an idea and objective was already gaining credence among the radical intelligentsia, it was Marx and Engels who first identified the agency of revolutionary change for socialism as the working class, namely those who owned no means of production but their own labour power.

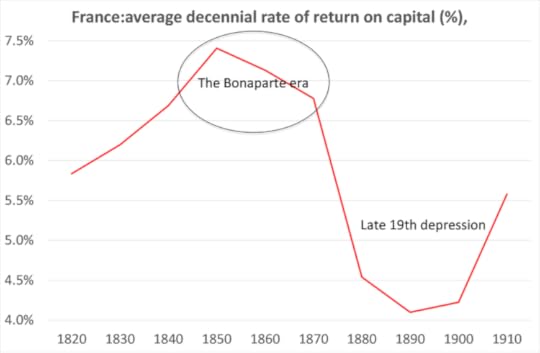

The Paris Commune came into fruition as the immediate result of the Franco-Prussian war. That war had been launched by Louis Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon, who had seized power in a coup in the aftermath of the defeat of the 1848 revolution. He autocratically ruled France for the next two decades. Those decades were ones of exceptional economic boom for capitalism in Europe and America. Economic recessions were few and far between (1859 and 1864), and relatively mild. Indeed, profitability rose to highs in the 1850s (up 11%), but then slid back by 4% in the 1860s.

Source: T Piketty, https://www.quandl.com/data/PIKETTY/TS6_2-Capital-labor-split-in-France-1820-2010

France was transformed from a backward agricultural economy into a fast-growing industrial one. Bonaparte launched a series of public works and infrastructure projects designed to modernise France’s cities. Paris emerged as an international centre of finance in the mid-19th century second only to London. It had a strong national bank and numerous aggressive private banks that financed projects all across Europe and the expanding French Empire. The Banque de France, founded in 1796, emerged as a powerful central bank.

Under Bonaparte, the French government coordinated several financial institutions to fund large projects, including Crédit Mobilier which became a powerful and dynamic funding agency for major projects in France including a transatlantic steamship line, urban gas lighting, a newspaper and the Paris metro system. France increased its rail lines by eight times and doubled its iron ore production. The population rose 10% and much more in the cities that now became urban centres of the new industrial working class. In 1855 and again in 1867 a world exhibition was staged in Paris to rival that of the previous Great Exhibition of British industrial might in 1851. And Ferdinand de Lesseps organized the construction of the Suez Canal.

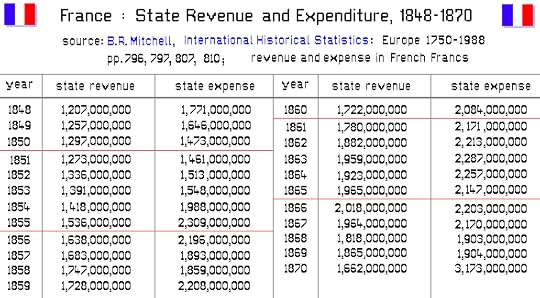

But Bonaparte’s war policy and the project to redesign Paris using the architect Haussmann proved expensive; France’s national debt increased considerably. And France’s industry found herself under increased international (i.e. mainly British) competition. Between 1848 and 1870, the public sector deficit tripled. What David Harvey has called ‘primitive Keynesianism’ began to run out of steam. The government resorted to monetarising the debt, MMT-style in the hope that this would continue to stimulate investment and growth. Marx called this the “Catholicism” of the monetary base, turning the banking system into “the papacy of production” and embraced what Marx called the “protestantism of faith and credit.”

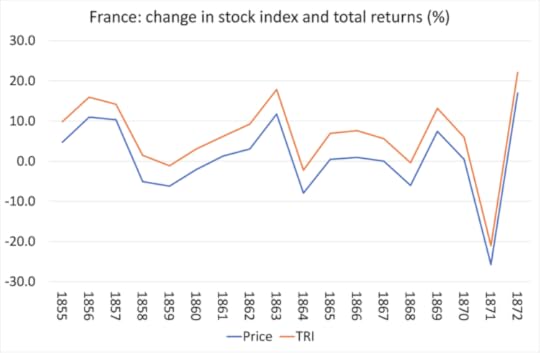

Financial crashes ensued as profit growth began to slide. Indeed, we can get an idea of the growing problems for the French capitalist boom in the movement of stock prices and equity returns. There was a fall in profits in the 1859 recession, and in 1864 and 1868 before the calamity of the Franco-Prussian war.

Source: A challenge to triumphant optimists? A blue chips index for the Paris stock exchange, 1854–2007, my calculations

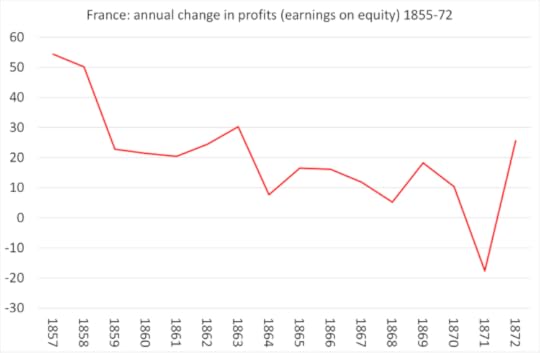

As the rate of profit fell during the 1860s, if from historically high levels, annual profits growth also declined, with significant drops in 1859 and 1864.

Inequality of wealth and income soared just as the working class expanded in numbers dramatically. Social tensions began to intensify. You could say it was a similar situation in May 1968 after two decades of economic boom under the rule of the Gaullist presidency – except that in 1870, war intervened and became the catalyst for the rise of the Commune.

It could be argued that Bonaparte, in his hubris, needed a war to divert the class struggle at home and he needed to restore France’ economic hegemony in continental Europe. Bonaparte thought the French army was superior to Bismarck’s Prussia. But he badly underestimated Prussian-led German economic and military power. The French were quickly defeated and humiliated. Bonaparte was captured, abdicated and fled. The bourgeois Republican government tried to fight on but eventually negotiated a terrible peace deal while the Prussian army laid siege to the starving populace in Paris. It was then that the Paris Commune – a council of workers delegates from the districts – emerged to seize political power in the interests of the populace.

This post cannot possibly cover all the events and themes in the short 72 days that the working class of Paris ruled through their own democratic structures, while the bourgeois government fled to Versailles and urged the Prussians to crush the Commune. The Commune did not survive long. It remained broadly isolated within France and was eventually bloodily suppressed by the forces of the Versailles government.

The best accounts of the Pars Commune are that of Communard Lissagaray, the History of the Paris Commune, translated by Eleanor Marx and published in 1876. https://www.marxists.org/history/france/archive/lissagaray/index.htm, and of course the Civil War in France, Marx’s own account written right after the Commune was crushed. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/. And Belgian Marxist, Eric Toussaint has given an excellent modern account of the economic machinations of the Banque de France and the Commune here. http://www.cadtm.org/The-Paris-Commun...

So in this short post, I shall just offer a few observations on the Commune’s economic policies. The most important was the failure to take over the financial levers of capital, in particular, the Banque de France. Ten years after the crushing of the Commune, Marx argued the Commune may well have survived if the Banque de France had been taken over. “Besides being simply the uprising of a town under exceptional circumstances, the majority of the Commune was by no means socialist and could not be. With a little bit of common sense, however, she could have obtained from Versailles a compromise favourable to the whole mass of the people – the only objective achievable at the time.”

Indeed, the biggest fear that the Versailles government had about the Commune was the loss of the Banque’s funds. Lissagaray notes, ” All serious insurrections began by seizing the nerve of the enemy, the cash register. The Commune is the only one that refused. It remained in ecstasy before the cash of the upper bourgeoisie which it had on hand.”

And Engels in his introduction to the re-edition of The Civil War in France in 1891: “many things [were] neglected that, according to our conception today, the Commune should have done. The most difficult to grasp is certainly the holy respect with which one stopped in front of the doors of the Banque de France. It was, moreover, a serious political mistake. The Bank in the hands of the Commune was worth more than ten thousand hostages. This meant the entire French bourgeoisie putting pressure on the government of Versailles to make peace with the Commune.”

Why didn’t the Commune leaders take the Bank over? Well, the majority of the Commune delegates were not socialist, but republican democrats. The socialist wing was a minority. And within that socialist minority, the Marxists were an even smaller minority. Most of the socialists were Proudhonists. They saw socialism coming from monetary control, namely through the use of credit. The man put in charge of Commune finances, Charles Beslay, a friend of Proudhon, had a blind faith in banking and finance more generally. He had been a member of the First International since 1866 and had a great influence in the Commune. Beslay had a background as a capitalist, as he had been the owner of a workshop employing 200 employees.

The Banque’s deputy governor and monarchist De Ploeuc commented: “Mr Beslay is one of those men whose imagination is unbalanced and who delights in Utopia; he dreams of reconciling all the antagonisms that are in society, the bosses and the workers, the masters and the servants.” Beslay confirmed his Proudhonism in action: “A bank must be seen from a double aspect; if it presents itself to us under its material side by its cash and its notes, it is also imposed by a moral side which is confidence. Take away the trust, and the banknote is just an assignat.” Beslay attacked the Marxists: “The Commune’s system and mine translate into this sacred word: ‘respect for property, until its transformation’. Citizen Lissagaray’s system results in this repulsive word: spoliation “.

Moreover, financial mechanisms are too complicated to be understood by ordinary citizens, or even by politicians, and should therefore be reserved for specialists or even experts. The attitude of the main Commune leader Rigault, was that “questions of business, credit, finance, banking […] needed the help of special men, who were only to be found in very small numbers. at the Municipality. […] Moreover, financial matters […] are not […] seen as the essential problems of the moment. In the immediate future, all that matters is that the money comes in.”

Instead of removing the very frightened governor of the Bank, Rouland, and taking over control of the huge funds that the bank held, Beslay allowed Rouland to stay in place and merely asked for sufficient funds to pay the National Guards defending Paris. Rouland kindly allowed Beslay to join the board of the bank as “Commune delegate”, where Beslay acted to ensure its independence from Commune control and demands.

Banque de France Governor Rouland

Banque de France Governor Rouland

Instead of wanting to take control, Beslay did everything to maintain the integrity of the Banque de France and to guarantee its independence. The result was that during the seventy-two days of its existence, the Commune received just 16.7 million francs for its needs: the 9.4 million assets that the Commune already had on account and 7.3 million loaned by the Bank. At the same time, the Banque sent the Versailles government 315 million francs from its network of 74 branches!

The money that the Commune did get was generally put to good use. About 80% went on defence of Paris, but there was also income distributed to the poorest parts of the city. The Commune introduced a progressive tax system, lowering the city tax for the poorest by 50% and introducing higher business taxes. Landlords were force to repay that the last nine months of rents and rents were suspended. There was a moratorium on all debts, which could now be repaid over three years without interest.

But the failure to take over the Banque was the Achilles heel of the Commune’s progress. And the Banque board knew it. They were terrified that there would be an “occupation of the Bank by the Central Committee, which can install a Government of its choice there, have banknotes produced without measure or limit and thus bring about the ruin of the establishment and of the country. ” And another industrialist board member claimed that “the Council cannot […] expose the Bank to being sacked. The evil would be irremediable and the destruction of the values of the wallet and the greenhouse of the deposits would constitute a terrible calamity, because it is a large part of the public fortune.”

If the Bank had been taken over, Versailles would have been denuded of funds to defeat the Commune as it held a portfolio of extended amounts to 899 million francs, of 120 million francs in securities. deposited as security for advances and 900 million francs in securities on deposit. Instead Beslay followed the Banque governor’s instructions and allowed the Banque to send money to Versailles while the deputy governor gave the order to lower all the securities into the cellars and then to silt the access staircase.

Two years after the crushing of the Commune, Beslay summed up his action in a letter to the right-wing daily Le Figaro, published on 13 March 1873: “I went to the Bank with the intention of protecting it from any violence of the exaggerated party of the Commune, and I am convinced that I have kept in my country the establishment, which was our last financial resource.” The Commune was eventually crushed in May 1871 with about 20,000 Communards being killed 38,000 were arrested and more than 7,000 deported. Beslay was allowed to go free and moved to Switzerland.

Some 45 years later, after another revolution sparked by war and defeat for the ruling class, Lenin recalled this lesson of the defeat of the Paris Commune: “The banks, as we know, are centres of modern economic life, the principal nerve centres of the whole capitalist economic system. To talk about “regulating economic life” and yet evade the question of the nationalisation of the banks means either betraying the most profound ignorance or deceiving the “common people” by florid words and grandiloquent promises with the deliberate intention of not fulfilling these promises.”

March 15, 2021

Mark Carney: value or price?

Mark Carney has a book out. It is called Value(s): Building A Better World For All. Canadian born Carney was formerly the governor of the Bank of England – the best paid governor ever at £680,000 a year plus £250,000 housing expenses. Carney recently commented that “You don’t get rich in public service.”!

Before that Carney was governor of the Bank of Canada, becoming the youngest central bank governor in the G20 nations. And before that he was 13 years at, guess where, Goldman Sachs, where he played a prominent role in advising the black majority government of South Africa on issuing international bonds and he was active for the company during the Russian debt crisis of 1998. Goldman Sachs made billions from these activities as the South African and Russian economies dived. And Carney made a fortune at Goldman Sachs. When asked recently whether he considered working for this investment bank ‘built a better world for all’, given its reputation as the ‘vampire squid of finance’, he responded “It’s an interesting question. When I worked for Goldman Sachs it wasn’t the most toxic brand in global finance, it was the best brand in world finance.” So he left just in time, it seems.

Recently he was asked what he thought was his greatest achievement at the Bank of England. His answer: “A more inclusive decision-making process with a more diverse staff.” So more diverse bankers – a great achievement. No wonder Carney has had many accolades bestowed on him by the great and good: he was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine in 2010, the world’s most trusted Canadian in 2011, and hailed as Britain’s most influential Catholic (by The Tablet) in 2015. And he has hinted that he might want to become the leader of the governing Canadian Liberal Party if and when Trudeau steps down.

After finishing at the BoE, he took a job with Brookfield Asset Management to advise them on environmental investment strategy and he is now to advise the UN and Conservative Johnson government on ‘financial strategy’ at the upcoming international UN Climate Change conference, Cop26, taking place in Glasgow, Scotland this November.

Now while he carries out his duties on the ‘environment’, he has written a book that outlines his philosophy on the nature of markets. As he tells us, modestly, that “I led global reforms to fix the faultlines that caused the financial crisis, worked to heal the malignant culture at the heart of financial capitalism and began to address both the fundamental challenges of the fourth industrial revolution and the existential risks from climate change.” But in doing these ground-breaking tasks to his usual brilliance he has become somewhat disillusioned with ‘markets’: “I felt the collapse in public trust in elites, globalisation and technology. And I became convinced that these challenges reflect a common crisis in values and that radical changes are required to build an economy that works for all.”

It’s not the first time that Carney has criticised ‘market’ economies and mainstream economics. He did so back in 2016 in a lecture in Liverpool. And again, in his book, he notes that, in this world of market economies, global poverty and inequality remains and most important for him, the environment is being destroyed. In his book, Carney asks why many of nature’s resources are not valued unless they can be priced. He gives the example of the Amazon rainforest only appearing as valuable when it has become a cattle farm. So price was not always a good measure of value. During the COVID crisis, Carney notes that it is the relatively low paid jobs that are high value, but they are not priced as such.

The problem, for Carney is that with markets “We are living Oscar Wilde’s aphorism – knowing the price of everything but the value of nothing – at incalculable costs to our society”. You see once we get beyond buying and selling goods and get into delivering services that people need, ‘the market’ falls short. As we move from a market economy to a market society, both value and values change. “Increasingly, the value of something, of some act or of someone is equated with their monetary value, a monetary value that is determined by the market. The logic of buying and selling no longer applies only to material goods, but increasingly governs the whole of life from the allocation of healthcare to education, public safety and environmental protection.”

Markets commodify people’s needs and that’s the problem because “Commodification, putting a good up for sale, can corrode the value of what is being priced. As the political philosopher Michael Sandel argues, “When we decide that certain goods and services can be bought and sold, we decide, at least implicitly, that it is appropriate to treat them as commodities, as instruments of profit and use.”

Turning away from the free-market libertarian philosophy of Milton Friedman and Ayn Rand, Carney appeals to moral philosophy of his hero, Adam Smith. “Putting a price on every human activity erodes certain moral and civic goods. It is a moral question how far we should take mutually advantageous exchanges for efficiency gains. Should sex be up for sale? Should there be a market in the right to have children? Why not auction the right to opt out of military service?”

You see, the apparently great proponent of ‘the invisible hand’ of free markets, Adam Smith was no such thing in all circumstances. Smith opposed monopolies and corruption in favour of free trade, but he also tempered that with a moral counterweight in support of the weak and exploited. Carney quotes Smith from his less famous book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, where Smith said: “However selfish man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

Thus Carney reaches a dilemma: price or value?; or to use Marxist terms: exchange value or use value?; profit or social need? Economics should be about increasing social well-being, but it is obsessed with market pricing instead. “This underscores the moral error of many mainstream economists, which is to treat civic and social virtues as scarce commodities, despite there being extensive evidence that public-spiritedness increases with its practice.” Carney’s answer is to restore ‘a balance’ between markets and morals; between price and value.

Carney is not the first of the great and good of the financial elite to ‘moralise’ about the failures of capitalism, once they have retired from carrying out its duties in a high priced but low value series of jobs. Another Christian and fellow central banker, Mario Draghi, now recently appointed (not elected) prime minister of Italy, and before that head of the European Central bank and, guess what, yet another senior employee of Goldman Sachs, has also professed a moral philosophy that is supposed to direct his good intentions in carrying out the strategies of finance capital.

Back in the middle of Greek debt crisis that saw the Greek people lose jobs and livelihoods in order to pay back debts to French and German banks, Draghi commented: “the crisis has dented people’s confidence in the capacity of markets to generate prosperity for all. It has strained Europe’s social model. Alongside the accumulation of staggering wealth by some, there is widespread economic hardship. Entire countries have been suffering from the consequences of misguided past actions – but also from market forces that are sometimes beyond their control.” Like Carney now, Draghi then asked the question of himself: “what is the right framework for reconciling free enterprise and individual profit motives with concerns for the common good and solidarity with the weak?” And he answered just as Carney does now: “Ultimately, we must be guided by a higher moral standard and a profound belief in creating an economic order that serves every person.”

Draghi went on to explain that: “I find myself in the company of Marx. Not Karl, but Reinhard. Cardinal Reinhard Marx has rightly insisted that “the economy is not an end in itself, but is in the service of all mankind.” Cardinal Reinhart Marx is the Archbishop of Munich who wrote a book at the depth of the Great Recession entitled “Das Kapital: A Plea for Man”, named after Karl’s work, but designed to reject Karl’s ideas. Reinhart Marx wants a market economy that is “kinder to the weak and downtrodden” instead of “heaping even more rewards on those who behave immorally.” That should appeal to Carney as well.

It seems that the appeal to ‘moral values’ over ‘market forces’ was also emitted by the former head of Goldman Sachs, Lloyd Blankfein, when Carney was there. Just after the end of the global financial crash, in 2010, Blankfein was interviewed and asked what ‘moral’ responsibility did Goldman Sachs and other investment banks have for the financial collapse that triggered the worst global economic slump (until COVID) since WW2. He replied that he thought his job as a prominent banker was to do “God’s work”.

Indeed, Blankfein continued his moral crusade in heading the bank during the multi-billion-dollar 1MDB state fund scandal, where former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak and his family corruptly siphoned off billions – it seems with the connivance of Goldman Sachs. God’s work in this case appears to be having Goldmans arranging bond issues worth $6.5 billion for 1MDB, with large amounts of state funds ($2.7bn) misappropriated in the process.

What is Carney’s practical solution to the contradiction between price and value created by the market? It is the classic mainstream one of trying to account for social needs in pricing by pressing and persuading capitalist enterprises to do things ethically and for ‘a better world for all’. In working for his latest asset management company he aims to get investors to make ethical and ‘green ‘ investments.