Michael Roberts's Blog, page 20

July 18, 2023

Frying in France

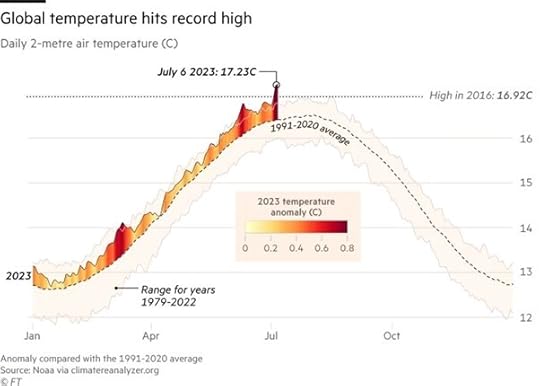

As I fry in record temperatures in the south of France, the concept of a short sunny vacation away from the vagaries of British weather has evaporated. The world endured the hottest week ever recorded between 3-10 July this year. And meteorologists say there is more to come – a lot more; indeed, a new global temperature record is still likely to be set before the end of next year.

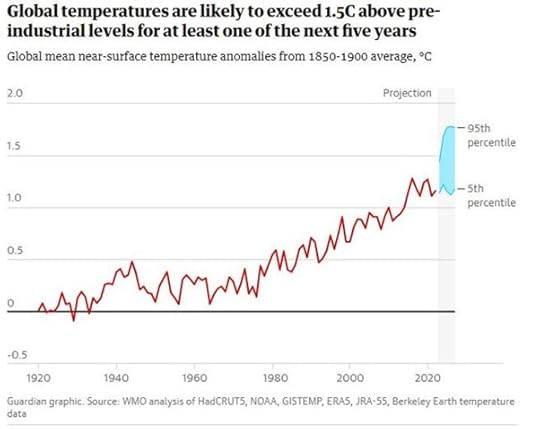

As a result, there are forecasts that this year or next could see world temperatures pass the 1.5C threshold that was set by the IPCC as being the upper limit for a rise in global warming that would avoid the planet passing through meteorological ‘tipping points’ that could bring irreversible changes to world weather patterns. Already last year, more than 61,000 people are estimated to have died prematurely as a result of the soaring temperatures that gripped Europe last summer.

The world is almost certain to experience new record temperatures in the next five years, and temperatures are likely to rise by more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) found there was a 66% likelihood of exceeding the 1.5C threshold in at least one year between 2023 and 2027.

https://public.wmo.int/…/global-temperatures-set-reach…;

Climate change is driving ever more extreme weather events, including changing rainfall patterns that caused fatal flooding in the US, South Korea, India and Japan over the past week at the same time as an extreme heatwave called Cerberus is forecast for southern Europe. These extreme weather events are another indication, together with stunningly hot ocean temperatures, dangerous heatwaves, and the rapid loss of polar icesheets, that fossil fuel production and use is massively disrupting the planet’s climate.

The 2021 landmark UN IPCC report signed off by 270 scientists from 67 countries around the world found that global warming would trigger changes to wetness and dryness, winds, snow and ice. Along with more intense rainfall and flooding in some areas, some regions would experience more intense drought. Precipitation is more likely to increase in high latitudes, while changes to monsoon precipitation are expected, the IPCC report said.

“What climate change is doing is supercharging weather events,” said Rachel Cleetus of the Union of Concerned Scientists. “Where there are dry periods, you are now getting megadroughts. This cycle is also very dangerous, because when you get very dry land that is denuded of vegetation, then when you get the rainfall you get mudslides.” She added: “I want to emphasise that this is human-caused climate change and this is happening because of the burning of fossil fuels.”

The immediate heat wave is a drastic combination of global warming and the arrival of El Nino, the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific. The ENSO is the cycle of warm and cold sea surface temperature (SST) of the tropical central and eastern Pacific Ocean. El Niño is accompanied by high air pressure in the western Pacific and low air pressure in the eastern Pacific. El Niño phases are known to last close to four years; however, records demonstrate that the cycles have lasted between two and seven years. Temperatures in the Pacific are then warmer than normal –by rising about 0.2C during El Niño. Together, carbon emissions and El Nino are creating accelerated temperatures in the northern hemisphere with all its consequences.

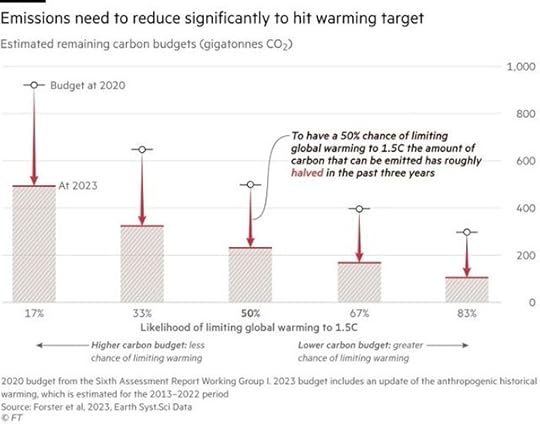

Indeed, the world’s remaining “carbon budget”, or the amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted to have a 50 per cent chance of limiting global warming to 1.5C, has halved in the past three years, a group of leading climate scientists have calculated. That budget would be exhausted in less than six years at current emissions levels from energy of about 38bn tonnes a year, as a result of the continued pollution and taking into account the latest data showing temperatures were rising faster than expected, they said. “This is the critical decade for climate change,” said Piers Forster, director of the Priestley Centre for Climate Futures at the University of Leeds.

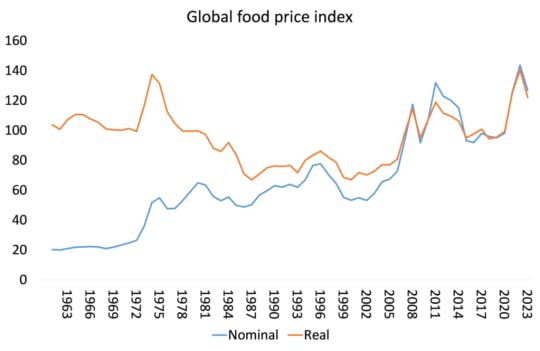

The longer-term impact will be on food security too. Since the COVID pandemic, global food prices hit new highs. Prices have fallen back a little since but now the damage to grain yields and other key food products from excessive temperatures is likely to drive prices up again.

The number of people affected by hunger globally rose to as many as 828 million in 2021, an increase of about 46 million since 2020 and 150 million since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a United Nations report that provides fresh evidence that the world is moving further away from its goal of ending hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms by 2030.

After remaining relatively unchanged since 2015, the proportion of people affected by hunger jumped in 2020 and continued to rise in 2021, to 9.8 percent of the world population. This compares with 8 percent in 2019 and 9.3 percent in 2020. Around 2.3 billion people in the world (29.3 percent) were moderately or severely food insecure in 2021 – 350 million more compared to before the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Nearly 924 million people (11.7 percent of the global population) faced food insecurity at severe levels, an increase of 207 million in two years.

Emissions must be cut by almost half by 2030 to limit the temperature rise to the1.5C level at which irreversible planetary changes are expected. But they continue to rise annually instead. Carlo Buontempo, director of Copernicus said: “We haven’t seen anything like this in our history. And for me this is a tangible example of what it means to be working in uncharted territory. Climate change is not something that is going to happen in 20 or 30 years’ time, it is happening now.” Sumant Sinha, head of India’s ReNew Power said of the Paris 1.5C target limit for global warming, “You can pretty much bury that target,” And even 2C is “looking a bit dicey”.

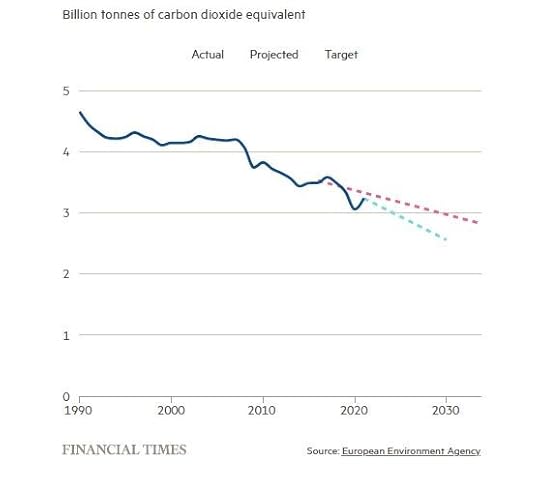

Europe is not meeting its climate mitigation targets. The European Climate Neutrality Observatory calculates that by 2021, the EU had cut its emissions by 30 per cent compared with 1990 levels. But to reach the 2030 goal it would need to make further cuts of 132 mega tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year, roughly the annual output of 332 gas-powered stations. https://www.ecologic.eu/19314

“The past five years of data offers a clear message: while emissions in Europe have continued to go down, a faster rate of reduction is required to meet both the 2030 target and climate neutrality by 2050,” it added. The World Meteorological Organization said this week that Europe was warming, with temperatures around 2.3C above pre-industrial levels in 2022. Fossil fuel subsidies are supposed to be phased out by 2025, but have increased over the past five years.

Energy firms have made record profits by increasing production of oil and gas, far from their promises of rolling back emissions. Exxon’s CEO, Darren Woods, told an industry conference last month that his company plans to double the amount of oil produced from its US shale holdings within the next five years. Wael Sawan, CEO of Shell, said curbing oil and gas production would be “dangerous and irresponsible”. “The reality is, the energy system of today continues to desperately need oil and gas. And before we are able to let go of that, we need to make sure that we have developed the energy systems of the future – and we are not yet, collectively ,moving at the pace [required for] that to happen.” Indeed!

COP28, the next UN summit on global warming, is being hosted by United Arab Emirates (UAE) who appointed oil executive, Sultan al-Jaber as president! The appointment was “a scandal” and a “perfect example of a conflict of interest,”says Michael Bloss, a German member of the European parliament with the Green Party. “It’s like putting the tobacco industry in charge of ending smoking.”

Meanwhile, Europe and many other parts of northern hemisphere fry. And the poorest parts of the world, already experiencing greater poverty from COVID and rocketing food and energy prices, will suffer even more, with many areas on the planet becoming uninhabitable for humans – other species have already been wiped out.

July 12, 2023

The cost of living and profits

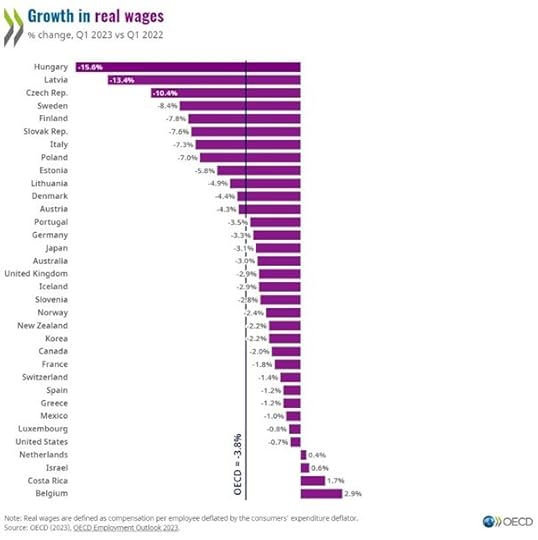

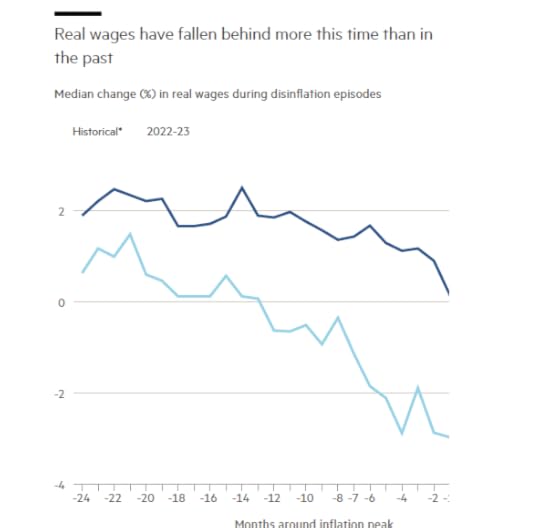

The latest employment report from the OECD is a real eye-opener on the cost of living crisis and whether wage rises or profit rises have been the biggest contributor to the rise in inflation. On wages, the OECD finds that real wages have fallen an average 3.8% in the last year in the OECD. “Labour markets have pushed up nominal wages, but less so than inflation, leading to a fall in real wages in almost all industries and OECD countries.”

The falls vary considerably for each OECD country. The biggest falls have been in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe, where energy prices rose the most from the loss of Russian oil and gas, while the US fall is one of the lowest as energy prices, although rising, have not shot up as much. Europe has had to switch from pipeline energy from Russia to much more expensive liquid natural gas (LNG) deliveries by shipping.

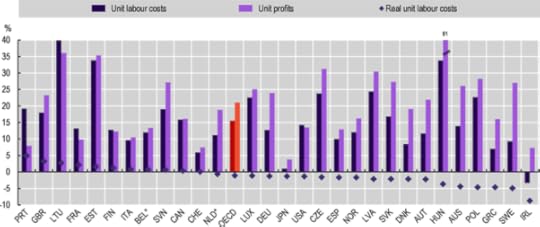

The OECD study also reveals in detail how much of the rise in inflation rates since the beginning of the COVID pandemic to now is due to wages and profits.

It seems that, on (unweighted) average throughout the OECD, profits per unit of output rose about 22% from end-2019 to Q1-2023, while wages per unit of output rose about 16%. In some countries, the role of profits in boosting prices was much greater compared to wages: Sweden 27% profits rise v 9% wages rise; Germany 24% v 10%; Austria 23% v 10%.

The largest rise in profits during the inflation spiral was in Hungary at over 60% followed by the Eastern European states at 30%-plus. Wage and profit increases per unit of output in the US were about equal at 14% each. Only Portugal saw a significantly higher contribution from wages per unit of output (18%) than profits (9%).

The OECD agrees with me and many others that the inflation spike was started by rising commodity and energy prices caused by supply chain blockages after the end of the pandemic and then accelerated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

As the OECD puts it: “The initial surge in inflation was largely imported in many OECD countries and driven by commodity and energy prices. However, over the course of 2022, inflation became more broad-based with higher costs increasingly being passed through into the prices of domestic goods and services.”

It was not caused by wage rises that never kept up with the inflation spiral. Again, the OECD says: “The evidence offers no indication of signs of a price-wage spiral so far. Nominal growth has picked up but it exhibits no clear signs of significant further acceleration across countries. The gap with inflation appears to be narrowing in recent months mostly because of a slow decline in inflation, but the erosion of real wages has not halted yet in the vast majority of OECD countries.”

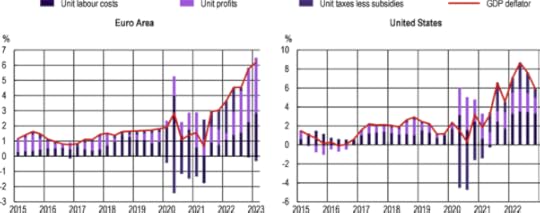

Indeed, profit rises were a much larger factor in sustaining the inflation rise. The conclusions from the report are clear: first, average real wages (ie after inflation) have fallen across the developed capitalist world over the last three years – indeed the largest and longest fall for at least 50 years. And second, the main contributor to higher prices of goods and services over this period has been increases in profits per unit of output, not wages – particularly in the Eurozone. “In the Euro Area, the contribution of profits has been particularly large, accounting for most of the increase in domestic prices in the second half of 2022 and first quarter of 2023.” As for the US, the OECD reckons that: “amid particularly tight labour markets, wages have generally contributed to increases in domestic prices more than profits in recent quarters.” But “the recent contribution of profit margins was much larger than in the years before the crisis but has decreased in the most recent quarters.”

Data from Europe and Australia show that the strong performance of profits in 2022 was not limited to the energy sector. In the year to Q1 2023, in Europe, unit profits increased more than unit labour costs in manufacturing, construction and finance, and grew at the same rate as unit labour cost in “accommodation food and transportation”. Similarly, unit profits increased more than unit labour costs in several sectors in Australia, including “accommodation and food”, manufacturing, trade, and transportation.

So is this answer to reducing inflation rates, that firms should reduce profit increases? Well, maybe not, says the OECD because “firm profitability may be undermined in the short term by a fall in the demand due to the tightening of monetary policy and the erosion of purchasing power. In this context, rising labour costs might be more likely to translate into a reduction in labour demand and potential employment losses. All in all, while the evidence suggests room for profits to absorb some adjustments in wages in several sectors and countries, the exact room of manoeuvre will likely vary across sectors and type of firms.”

In other words, trying to reduce price rises by restricting profit rises while allowing workers wage rises to catch up could cause a slump as employers reduce their workforces to stop increased labour costs. That would mean rising unemployment. Yes, that is what happens under a profit-driven system of production.

So what is the answer to economic growth without inflation accelerating? The OECD says: “In the long run, sustained real wage gains can only be ensured through sustained productivity growth.” OECD countries need to “make the most of the opportunities afforded by new technological developments, such as Artificial Intelligence.” So far, no sign of that.

July 10, 2023

The great divergence

Branco Milanovic, former chief economist at the World Bank, has become the leading analyst on global inequality. Starting with his book, Worlds Apart in 2005, he has documented trends in the global inequality of income (not so much wealth) since the industrial revolution and since capitalism becoming the dominant mode of production globally.

In that book, he calculated that the global inequality of income (and wealth), was ’20:80′ (i.e. that 80% of world’s then 6.6bn population could be classed as poor) and the situation was getting worse, not better, even if you take into account the then booming so-called BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China).

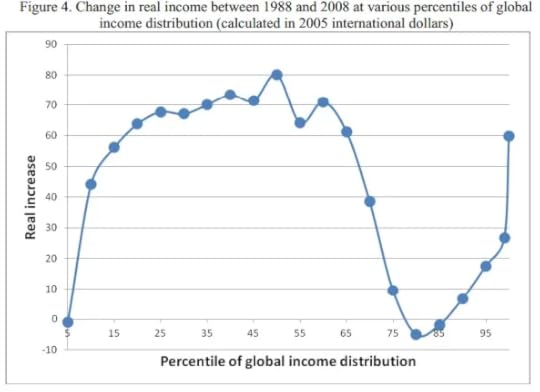

At that time he presented the changes in real income for people globally at various percentiles of income distribution and produced what became called the ‘elephant graph’ – namely that the big improvements in income levels were to be found in the middle range of incomes, while the very poor and those in upper income ranges (except for the extremely rich) actually lost ground.

That suggested to many that global inequality was falling because middle income earners around the world had gained. There was a great convergence, not divergence.

But the elephant graph hid the reality. This prospering middle-income group was almost entirely due to China. The Chinese economy has taken upwards of 900m Chinese out of dire poverty in just three decades and average incomes rocketed, particularly in the last two decades. If you strip out China, the elephant graph collapses. Neither the rest of Asia nor India have managed any such improvement in average incomes. There were also many other reasons to be sceptical of the elephant graph and the conclusions that you can draw from it – read my posts on this here.

But now Milanovic has updated his estimates of global inequality in a new study. Some journalists have headed the results as “The world is the most equal it has been in over a century.” Sounds great – but again, the devil is in the detail.

There are two factors in global inequality: inequality between national per capita incomes and inequality of income of people within nations. In previous work, Milanovic argued the the former is more important in overall global inequality for individuals than the latter. So where you live is more important than your income in that country compared to the richest there.

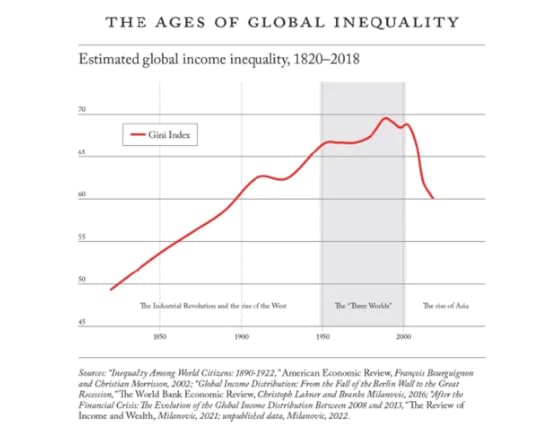

In his latest work, Milanovic re-estimates global inequality between 1820 and 1980, reappraises the results up to 2013, and presents new inequality estimates for 2018. He concludes that, historically, global inequality has followed three eras: the first, from 1820 until 1950, characterized by rising between country income differences and increasing within-country inequalities; the second, from 1950 to the last decade of the 20th century, with very high global and between-country inequality; and the current one of decreasing inequality thanks to the rise of Asian incomes, especially Chinese.

According to Milanovic, from the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the early nineteenth century to about the middle of the twentieth century, global inequality rose as wealth became concentrated in Western industrialized countries. It peaked during the Cold War, when the globe was commonly divided into the “First World,” the “Second World,” and the “Third World,” denoting three levels of economic development. But then, around 20 years ago, global inequality began to fall, largely thanks to the economic rise of China, which until recently was the world’s most populous country. Global inequality reached its height on the Gini index of 69.4 in 1988. It dropped to 60.1 in 2018, a level not seen since the end of the nineteenth century.

The first era of global inequality stretched from roughly 1820 to 1950, a period characterized by the steady rise of inequality. Around the time of the Industrial Revolution (approximately 1820), global inequality was rather modest. The GDP of the richest country (the United Kingdom) was five times greater than that of the poorest country (Nepal) in1820. (The equivalent ratio between the GDPs of the richest and poorest countries today is more than 100 to 1.)

The growth of global inequality during the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century was driven both by widening gaps between various countries (measured by the differences in their per capita GDPs) and by greater inequalities within countries (measured by the differences in citizens’ incomes in a given country). The country-to-country differences reflected what economic historians have called the Great Divergence, the growing disparity between, on the one hand, the industrializing countries of western Europe, North America, and, later, Japan, and, on the other hand, China, India, the African subcontinent, the Middle East, and Latin America, where per capita incomes stagnated or even declined. In effect, this was a quantitative measure of the domination of a small bloc of imperialist countries over the rest.

But Milanovic finds that global inequality began to dip about two decades ago. It has dropped from 70 Gini points around the year 2000 to 60 Gini points two decades later. This decrease in global inequality, having occurred over the short span of 20 years, is more precipitous than was the increase in global inequality during the nineteenth century.

Does this mean that capitalism is succeeding in reducing inequality and there is now a great convergence? No, because the decrease is driven by really just one country’s income growth: China. And at the same time as China’s fast growth reduced the overall global inequality index; within economies, inequality has risen in just about all the major economies.

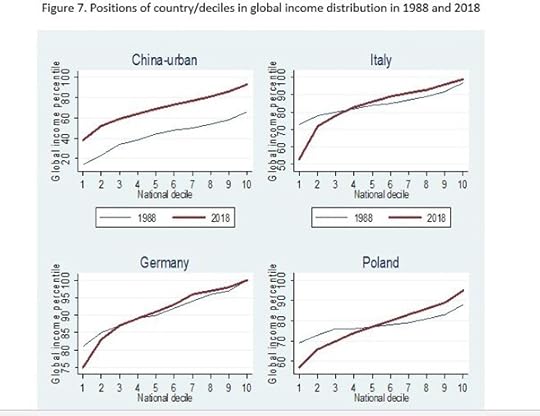

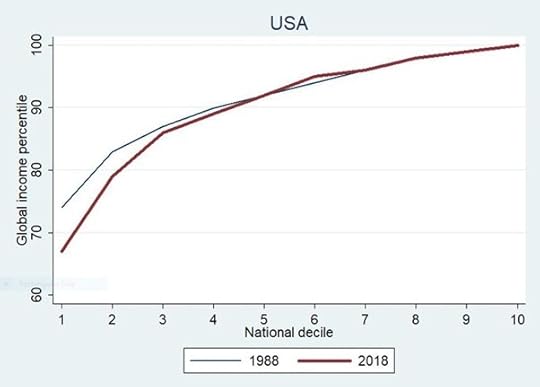

Moreover, the richest income earners in the world remain living in the imperialist bloc. In 1988, 207 million people made up the top five percent of earners in the world; in 2018, that number was 330 million, reflecting both the increase in the world population and the broadening of available data. Americans make up the plurality of this group. In both 1988 and 2018, over 40 percent of the globally affluent were U.S. citizens. British, Japanese, and German citizens come next. Overall, Westerners (including Japan) account for almost 80 percent of the group. Urban Chinese broke into the globally affluent only more recently. But their share is still small, up from 1.6 percent in 2008 to 5.0 percent in 2018.

Once you exclude China from the data, then there has been no global convergence at all. With China having vacated many of the slots at the bottom of the distribution, those are now filled mostly by poorer Indian households who now have lower living standards than their Chinese counterparts.

And in the imperialist bloc, the lower income groups have lost ground globally. The poorest Italian families were in the top 30 per cent of the world’s income distribution in 1988, but now only just make it into the top half. Importantly, the middle classes in all rich countries have now slipped down the global rankings. This is a positional reshuffling of major proportions; note the rise in position for lower income earners in China from 1988 to 2018 and the decline in the global position of the lower deciles in Italy and Germany, and even in Poland where Poland’s top 10% also went up significantly.

The decline affected the US as well, where about 30-40 percent of the distribution is now placed globally lower than in 1988. Of course, the US richest are still at the global top.

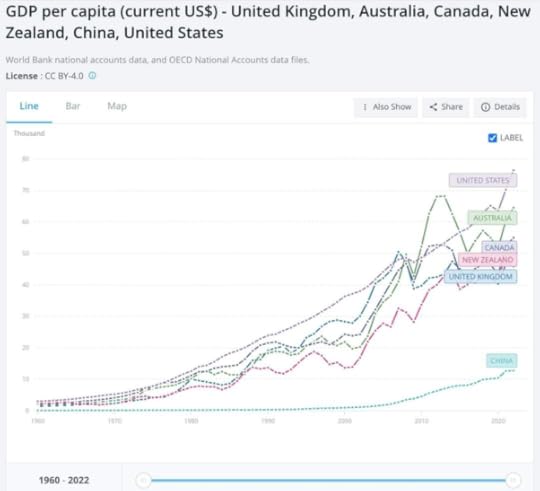

Global inequality will probably not decline any more from here. That’s because China’s phenomenal growth may have closed the income gap with the imperialist countries a little but it is still a long way behind.

And the income gap between China and most other poorer countries has widened because the latter are making little or no progress in reducing the gap with the imperialist bloc. As Milanovic puts it: “Once we take China out of the picture, the next engine of global inequality reduction is India, but India’s growth started sputtering even before the global financial crisis.”

Moreover, the fastest population growth in the world is in Africa. So if global inequality is to fall based on reducing the gap between rich and poor countries, then Africa must start to grow its per capita income at 6-7% a year. Africa has no chance of achieving such growth – on the contrary, its share of global GDP is the same as in 1980 and has lost ground in the 2010s.

If anything, the great divergence is likely to resume.

July 5, 2023

From greedflation to stagflation and then slumpflation

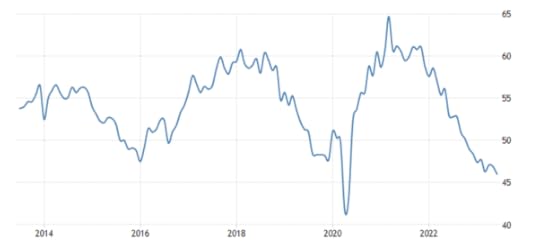

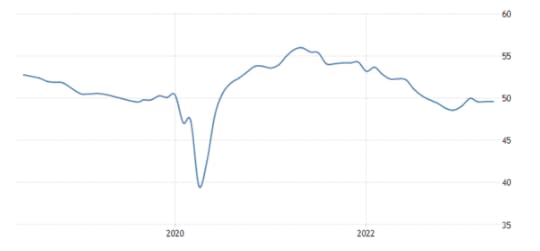

Global economic growth is slowing. There is a global manufacturing recession already in place: the latest surveys of economic activity in the major economies show that there is an outright contraction in manufacturing in all the major economies – and it is getting worse.

US ISM manufacturing index (score below 50 means contraction)

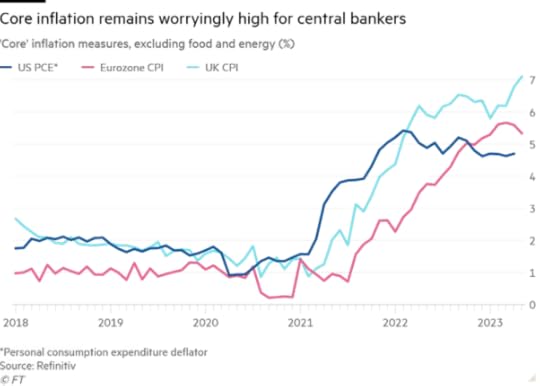

But inflation of prices outside of food and energy, the so-called core inflation rate, is not falling in the major economies.

Central bank chiefs continue to shout the mantra that interest rates must rise to reduce ‘excessive demand’ in order to get demand back in line with supply and so reduce inflation. But the risk is that ‘excessive’ interest rate hikes will accelerate economies into a slump before that happens and also engender a banking and financial crisis as indebted companies go bust and weak banks suffer runs on their deposits.

The stock markets of the world remain sanguine and head up to highs based on the view of investors that a ‘soft landing’ will be achieved ie a decline in inflation to the central bank targets without a substantial contraction in investment, output and employment.

Yet all the portents remain that the major economies face a new slump ahead. First, inflation remains ‘sticky’ not because wage rises (or spending) from labour have been ‘excessive’, contrary to view of central bankers and mainstream economic pundits. As I and others have argued before, it is the poor recovery in output and productivity coupled with a very slow return to international transport of raw materials and components that kicked off the inflationary spiral – not workers demanding higher wages.

If anything, it is ‘excessive profits’ that have driven up prices. Taking advantage of supply chain blockages after the COVID pandemic and shortages of key materials, multi-national companies in energy, food and communications raised prices to reap higher profits. The case for ‘sellers inflation’ was kicked off by analyses by Isabelle Weber and others that forced even the official monetary authorities to admit that it was capital and profits that gained while labour and nominal wages took the brunt of the cost of living rises.

The ECB and the IMF have since published reports admitting the role of profits in inflation. The IMF joined the growing chorus that inflation was really driven by rising raw material import prices and then by rising corporate profits, not wages.

“Rising corporate profits account for almost half the increase in Europe’s inflation over the past two years as companies increased prices by more than spiking costs of imported energy.” This contradicted the claims of the heads of the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England that a ‘hot labour market’ and wages were the drivers of a wage-price spiral.

The trendy phrase in vogue is ‘greedflation’, implying that companies had greedily hiked the margin between costs and prices to boost profits. But the evidence for increased profit margins is dubious. Profit margins are high in the US, but after peaking at the end of 2022, they have been falling back since.

In a new study for France, Axelle Arquié & MalteThie found that price rises were greater where firms had ‘market power’ and this explained ‘sellers inflation’: “in sectors with higher markups, prices increase relatively more: in the least competitive sector, firms pass through up to 110% of the energy shock, implying an excess pass-through of 10 percentage points. In addition, we find that the association between markup and pass-through is even higher when markup dispersion is low, consistent with the argument that firms engage in price hikes when they expect their competitors to do the same.”

On the other hand, in the UK there appears to have been no increase in the profit share of corporate output value.

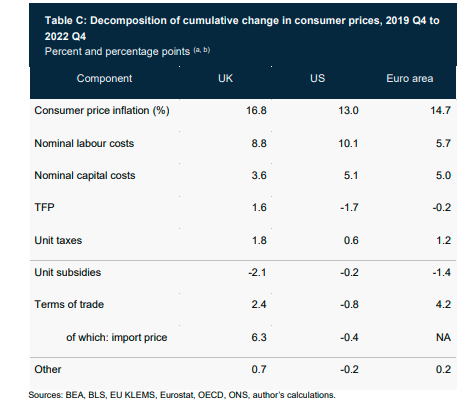

The Bank of England economist Jonathan Haskell also argued that there is little evidence that rising profit margins are the main cause of accelerating inflation. In the three years since 2019, average prices for consumption goods have increased 16.8% in the UK, 13% in the US and 14.7% in the Euro area. Of that increase, labour costs contributed about half the rise in the UK, 60% in the US and 40% in the Eurozone. The rise in profits contributed only around 30% in each area. What was interesting is that when productivity growth (TFP) fell (as in the UK) that raised prices much more.

So is it a profits-price spiral or a wage-price spiral? This question has led to an intense debate between mainstream economists and more heterodox ones, although the ideological division has been blurred with some on both sides of debate: is inflation a ‘sellers inflation’ or ‘greedflation’ from the corporations; or is it the result of ‘tight’ labour markets allowing workers to hike wages and force companies to raise prices; or is it, as the monetarists argue, just too much money supply chasing too few goods?

Whatever the case, the IMF is worried that as workers try for higher wages to compensate for rising prices, “companies may have to accept a smaller profit share if inflation is to remain on track .” Similarly, the Bank for International Settlements talks about this in its new Annual Economic Report. “The surprising inflation surge has substantially eroded the purchasing power of wages. It would be unreasonable to expect that wage earners would not try to catch up, not least since labor markets remain very tight. In a number of countries, wage demands have been rising, indexation clauses have been gaining ground and signs of more forceful bargaining, including strikes, have emerged. If wages do catch up, the key question will be whether firms absorb the higher costs or pass them on.”

Here the arch-monetarist BIS hints at the need for companies to “absorb higher costs” by accepting “lower profit margins.” But as it points out “Should wages increase more significantly—by, say, the 5.5 percent rate needed to guide real wages back to their pre-pandemic level by end-2024—the profit share would have to drop to the lowest level since the mid-1990s (barring any unexpected increase in productivity) for inflation to return to target.”

Either way, the debate has switched to whether the central banks should continue to increase interest rates to try and get inflation down to the arbitrary target of 2% or instead let inflation stay higher and for longer rather than provoke a slump.

Arch Keynesian, Martin Wolf in the Financial Times made it clear where he stood. As a true Keynesian, he wanted ‘demand’ driven down at all costs. “We are seeing a price-price and wage-price spiral radiating throughout the economy. The only way to halt this is to remove the accommodating demand. In other words, the question is not whether there will be a recession; it is rather whether there needs to be one, if the spiral is to be halted. The plausible view is that the answer to the latter part of this question is “yes”. Like it or not (I certainly do not), the economy will not get back to 2 percent inflation without a sharp slowdown and higher unemployment.”

Wolf concluded that “In sum, rates may have to rise again.” Should governments help households with the rising cost of borrowing and servicing debt? “The answer is: absolutely not. that this would defeat the object of the exercise, which is to tighten demand. If fiscal policy were to offset this, monetary policy would have to be still tighter than otherwise. If the desire is to moderate the monetary squeeze, fiscal policy should be tightened, not loosened.” So Wolf advocates both fiscal and monetary austerity.

You see, he said, we cannot accept a relaxation of the target for inflation because if “a country abandons its solemn promise to stabilise the value of the currency as soon as it becomes hard to deliver, other commitments must also be devalued.” Here Wolf repeats the view of Keynes himself on inflation: wrote (pdf): “Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency.” This expresses the fear of economies with weaker currencies compared to the dollar – not just the UK, but particularly all the ‘emerging’ economies currently deep in debt distress. Whichever is tougher on austerity can avoid a weak currency and inflation but instead get a deep slump. It’s trade-off for many countries.

The austerity option upset the maverick former Bank of England chief economist, Andy Haldane who wrote: “the textbook role of monetary policy is to tolerate, not offset, these temporary inflation misses provided inflation expectations remain anchored. Not to do so inflicts unnecessary further damage on growth”, he claimed in opposition to the central bank chiefs and Wolf. So what if there is higher inflation: “at 3-4 per cent, inflation no longer enters the public consciousness. there is essentially no evidence it would impose costs that are any greater than at 2per cent. But the costs of lowering inflation those extra few percentage points, measured in lost incomes and jobs, are larger at these levels of inflation. Squeezing the last drops, at speed, would mean sacrificing many thousands of jobs for negligible benefit.” So let’s tolerate higher inflation.

As he put it: “Imagine a doctor, uncertain about the nature and severity of a disease, who has administered a large medicinal dose which has yet to take effect. Prudence would cause them to pause to see how the patient responded before doubling the dosage. That principle is one central banks should heed now to avoid overdosing the economy.” So let’s wait and see and let inflation take its course, he argues. But that means a longer and higher cut into living standards for workers as inflation stays higher and longer.

Star liberal leftist economic historian, Adam Tooze was equally affronted by Wolf’s orthodox position. “The angst now is about inflation persistence. Getting it back down to 2 per cent is the battle-cry. As it was half a century ago, this is a profoundly conservative political argument dressed in the garb of economic necessity. So this is where we have arrived in 2023: to bring inflation back to 2 per cent while preserving the banks, common sense insists that we need higher interest rates for longer, plus austerity. And, at this point, you have to ask whether western elites have learnt anything from the last decade and a half.” The call for austerity was “the old neoliberal logic of “there is no alternative”. Tooze argued that “in pursuit of lower inflation, monetary austerity risks the same fate. It is time to steer the stampeding herd away from the cliff edge, for the sake of the financial security of millions of people and the credibility of our policy institutions.”

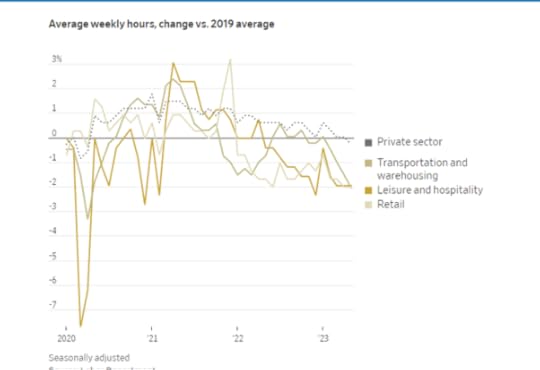

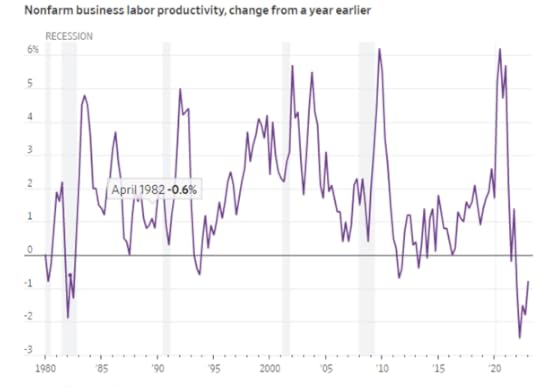

So argument goes on among central bankers and economists. But what is missing from all this is what caused inflation to rise in the first place and why it stays ’sticky’. The recovery in output globally has been weak since the end of the pandemic. Growth in the productivity of labour (output per worker) has been low. Indeed in value terms (ie hours of work) supply has been flat or falling.

As a result any increase in spending or credit has ended up adding to price inflation. But nobody mentions that it is the failure of capitalist accumulation to boost the productivity of labour (and value creation); instead the argument is about whether labour or capital should take the hit; or whether inflation should be allowed to stay high or be driven down despite the risk of slump.

The BoE data above reveal that the lower is productivity growth, the higher is the sticky’ core inflation rate. And as the BIS also said above, inflation won’t come down without a slump unless productivity growth rises sharply.

Let me remind readers of the state of US labour productivity – and remember the US is the best performing major capitalist economy.

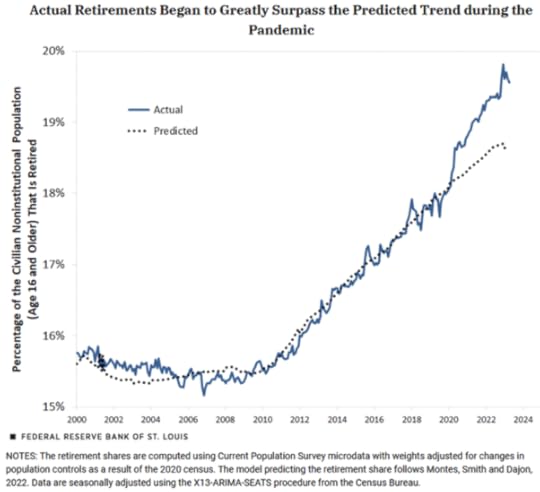

The reason the US labour market is ‘tight’ is not because the economy is expanding at a fast rate and delivering well-paid jobs for all. It is because so many skilled people of working age have left the labour market since the pandemic. Researchers at the St. Louis Fed estimate that the US has about 2.4 million “excess” retirees above the previously normal pace. If correct, that’s almost enough to explain the drop in participation rates.

Also immigration, a key driver of labour supply has diminished as many countries apply yet more restrictions. And so far, AI technology is not delivering faster productivity growth from the existing workforce.

Why is productivity growth not appearing? It’s because investment in technology is not picking up; instead companies prefer to find cheap labour even from a ‘tight’ labour market. Why is investment not picking up? It ‘s because the profitability of capital is still low and has not seen any significant shift up – outside of the small group of mega companies in energy, food and tech.

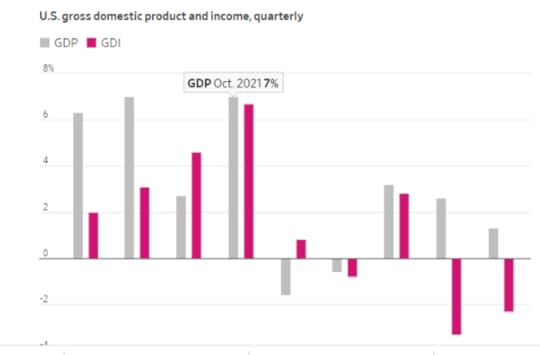

And while US real GDP has risen, that is not reflected in domestic income growth. There is a significant divergence between the gross domestic product (GDP) and gross domestic income (GDI). That divergence is due to both wages and profits (after inflation) falling. So, on a GDI basis, the US economy is already in recession.

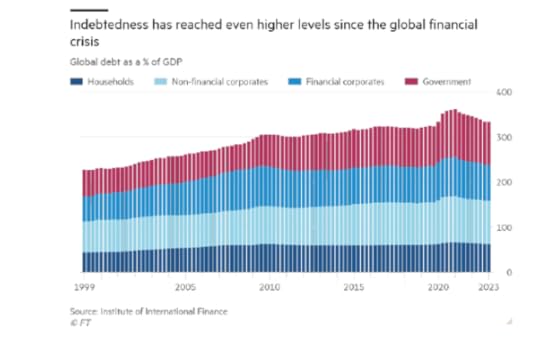

Way back, I reckoned that the next recession would not be triggered by a housing bust or a stock market bust, or even a financial crash, but by increasing corporate debt costs, driving sections of the corporate sector into bankruptcy – namely ‘fallen angels’ and ‘zombie companies’. Corporate debt is still at record highs and whereas the cost of servicing that debt was comfortable for most due to low interest rates, that Is no longer the case.

The squeeze between falling profits and rising interest rates is tightening. We have already seen the impact of rising interest rates on the weaker sections of the banking system in the US and Europe. A record amount of commercial mortgages expire in 2023 and are set to test the financial health of small and regional banks already under pressure following the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. This year will be critical because about $270 billion in commercial mortgages held by banks are set to expire, according to Trepp—the highest figure on record. Most of these loans are held by banks with less than $250 billion in assets. In a recent paper, a group of economists estimated that the value of loans and securities held by banks is around $2.2 trillion lower than the book value on their balance sheets. That drop in value puts 186 banks at risk of failure if half their uninsured depositors decide to pull their money.

US Treasury Secretary Yellen is not worried, as she says the recent Federal Reserve ‘stress tests’ on banks showed that all could take any hit to capital from rising rates. But the tests also showed that the three banks that went under last March would have passed those tests! Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee compared the potential coming impact of the Fed’s 5 percentage points in rate increases to the unseen hazards faced by Wile E. Coyote, the unlucky cartoon character. “If you raise 500 basis points in one year, is there a huge rock that’s just floating overhead…that’s going to drop on us.”

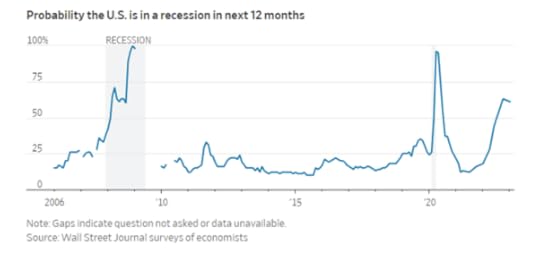

And the pundits remain worried. Their estimate of a probability of a recession in the next 12 months is at 61%, historically high outside actual recessions.

Whatever the cause of rising inflation and whatever the argument over whether to keep to inflation targets, the major economies continue to slide towards a slump; the Eurozone is already there; and the US is going there whatever the stock market thinks and whatever the authorities claim. Far from a soft landing, it will be from stagflation to slumpflation.

June 29, 2023

Adam Smith: free marketeer or moral philosopher?

It was the tercentenary of the birth of Adam Smith this month. Nobody is quite sure on what day Smith was born in June 1723, but economists at the University of Glasgow organized a series of events and debates on Smith’s ideas throughout the month.

Adam Smith has become the guru of ‘laisser-faire’, free market economics – the man that Chicago University economists like George Stigler and Milton Friedman turned to as their theoretical mentor for the ‘free market’. He was lauded by right-wing free market politicians like Margaret Thatcher as inspiring them to adopt policies to reduce the size of government and state and ‘let the market rule’ in all aspects of social organization. And the global free market economists like Friedrich Hayek and the Austrian school of free market economics looked to Smith for their basic approach. There is even a ‘think-tank’ based in the UK that claims to develop economic policy based clear ‘free market’ principles. Its slogan is “Using free markets to create a richer, freer, happier world.”

Smith wrote two great books. The first was The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759 and his second, the most famous, was The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. This made his name as “The Father of Economics.” And yet anybody who reads both these books closely will find that Smith was not some raging free market evangelist that denied the role of government or for that matter considered that human behaviour was driven by material self-interest and nothing else.

His most famous statement was about the so-called ‘invisible hand of the market from the Wealth of Nations: “(Each individual) generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it…He intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.”

Smith is arguing here that, as each individual pursues his or her own economic activity, the individual is unaware that the combination of all these individual actions produce a market for production and consumption that is not under his or her control but leads ‘invisibly’ to a better outcome for all. Behind this was Smith’s great insight that modern industry is based on a division of labour: when the production of commodity is broken down into discrete parts where human labour specializes instead of workers doing every part of the process, productivity rises and costs and prices fall. Marx tells us the dark side of the division of labour: the alienation of humanity turning creative work into toil and drudgery.

Similarly, for Smith, individuals competing on a market will deliver an outcome beneficial to all. And from this flowed the view that “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.” This is the classic basis of modern neoclassical economics: based on the myth that the consumer is ‘sovereign’.

Smith was strongly opposed to monopoly of which there were many in his time, often controlled by a corrupt monarchial state. These monopolies ruined industry and reduced entrepreneurial initiative and thus productivity and prosperity. He was in particular opposed to mercantilism, the doctrine of international trade where nations protected their industries and built up surpluses rather than expand trade. He explained why protectionism is always self-defeating. “By means of glasses, hotbeds, and hotwalls, very good grapes can be raised in Scotland, and very good wine too can be made of them at about thirty times the expense for which at least equally good can be brought from foreign countries. Would it be a reasonable law to prohibit the importation of all foreign wines, merely to encourage the making of claret and burgundy in Scotland?”

But it is a myth created by today’s free marketers that Smith was opposed to government and to moral behaviour over material interest. On the contrary. Chicago economist Jacob Viner of the 1920s summed it up:

“Adam Smith was not a doctrinaire advocate of laissez faire. He saw a wide and elastic range of activity for government, and he was prepared to extend it even farther if government, by improving its standards of competence, honesty, and public spirit, showed itself enticed to wider responsibilities. . . . He devoted more effort to the presentation of his case for individual freedom than to exploring the possibilities of service through government. . . . [but] Smith saw that self-interest and competition were sometimes treacherous to the public interest they were supposed to serve, and he was prepared. . . . to rely upon government for the performance of many tasks which individuals as such would not do, or could not do, or could do only badly. He did not believe that laissez faire was always good, or always bad. It depended on circumstances; and as best he could, Adam Smith took into account all of the circumstances he could find.”

He was strongly opposed to slavery. “There is not a negro from the coast of Africa who does not possess a degree of magnanimity which the soul of his sordid master is scarce capable of conceiving. Fortune never exerted more cruelly her empire over mankind, than when she subjected those nations of heroes to the refuse of the jails of Europe.”

Marx was a close reader of The Wealth of Nations. He recognized Smith’s contribution in attempting to develop of a theory of value based on labour. As Smith said: “Labor alone, therefore, never varying in its own value, is alone the ultimate and real standard by which the value of all commodities can at all times and places be estimated and compared. It is their real price; money is their nominal price.” But Marx went on to criticize Smith for inconsistency in his labour theory of value, as Smith reverted to a theory of value based of ‘factors of production’ ie rent from landlords, profits from capitalists and wages from labour, rather than all value being created by labour and then appropriated by landlord and capitalists.

Adam Smith was also not a hardline free trade supporter. His position was nuanced by the state of the British economy at the time. He supported the Navigation Acts – which regulated trade and shipping between England, its colonies, and other countries – despite the fact that they mandated that goods be transported on British ships even if other options were cheaper. “Defence,” he wrote in The Wealth of Nations, “is of much more importance than opulence.”

Denouncing desirable security policies as “protectionist” was beside the point then and now. After all, security of the capitalist state was more important than the free market in international trade. And the ‘free market’ is only lauded as long as it does not reduce the profitability of enterprise.

June 24, 2023

Reconstructing Ukraine

The 2023 Ukraine Recovery Conference (URC23) ended in London last Friday. It was a continuation of the cycle of meetings beginning in 2017.

The London URC aimed to build on the commitments agreed last year at Lugano, and the work of the Multi-Agency Donor Coordination Platform for Ukraine. It was attended by hundreds of corporate leaders and governments. The Lugano conference was the basis for the planned invasion of foreign capital and multi-nationals into Ukraine once the war was over.

However, as the war drags on, with many more thousands dying in battle and civilian infrastructure in Ukraine being decimated by Russian missiles (and parts of Russian territory now being hit), Western governments and multi-nationals are aiming to speed up the reconstruction of Ukraine as a bulwark within EU and NATO spheres even while the war continues.

The EU has now announced a $50bn investment aid to Ukraine and the ubiquitous private equity company Blackrock and leading US bank JP Morgan have been drafted in to raise private capital for Ukraine’s reconstruction. They are ‘donating’ their services but will get first pick on any investment opportunities. “The fund is being set up to also give public and private sector investors the opportunity to invest into specific projects and sectors,” said Stefan Weiler, JPMorgan’s head of debt capital markets for central Europe, Middle East and Africa. “There will be different sectoral funds that the fund identified as priorities for Ukraine. The aim is maximise capital participation.” The banks aim to raise public concessional money from governments to absorb initial losses and then get private capital to invest for the profitable investments.

The World Bank estimates the cost of Ukrainian recovery and reconstruction after the first year of Russia’s war at $411bn or twice Ukraine’s prewar GDP. But that was before Kyiv’s counter-offensive even began, and before the disastrous destruction of the Kakhovka dam. With Russia still targeting infrastructure, final costs might top $1tn.

The aim of the Ukraine government, the EU, the US government, the multilateral agencies and the American financial institutions now in charge of raising funds and allocating them for reconstruction is to restore the Ukrainian economy as a form of special economic zone, with public money to cover any potential losses for private capital. Ukraine will also be made free of trade unions, severe business tax regimes and regulations and any other major obstacles to profitable investments by Western capital in alliance with former Ukrainian oligarchs. As the Financial Times put it; “International public-sector financing must be the bedrock of the reconstruction effort. But since the private sector is expected to play a central role not just in doing the work but helping to fund it, mobilisation of private investment will be required on a scale with few precedents.”

Nearly 500 global businesses from 42 countries worth more than $5.2 trillion and 21 sectors have already signed the Ukraine Business Compact, pledging to support Ukraine’s recovery and reconstruction. As the Ukraine government put it at URC23, “International partners will work between now and the URC24 in Germany to launch new business to business initiatives to build and grow private sector partnerships with Ukraine.”

Foreign businesses are demanding insurance cover for their projects (after all, a war is still going on) and they want governments to pay for this. Foreign aid and investment will also be subject to tight conditions supposedly to stop the chronic corruption that existed in Ukraine prior to the war. Unfortunately, there have been cases of such corruption since. For example, Ukraine’s National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO) found “large-scale corruption in the Supreme Court, in particular a scheme to obtain undue advantages by the leadership and judges of the Supreme Court”, with the head of the Supreme Court receiving a $2.7 million bribe.

The Ukraine government wants to create a capitalist free market economy within the EU and backed by NATO armoury. To do this, there is no role for public investment except as a ‘loss leader’; there will be a free reign for capitalist companies; and the interests of labour, social and public services will be relegated.

As one Ukrainian commentator put it: “Zelensky’s party has pushed through laws that have effectively destroyed the right to collective bargaining as well as other labor protections in Ukraine. It has also implemented pension law reforms billed as “decommunizing” the social welfare system but in fact amounting to radical cutbacks. Both plans were drafted well before the Russian invasion, but the wartime state of emergency has greatly aided the party’s ability to implement its agenda — whose anti-labor animus has even run afoul of the normally moderate International Labour Organization. Instead of labor rights and social welfare, Zelensky and his advisors promote “smartphone courts” (a joint venture with Amazon) and other public-private partnerships. In effect, they see postwar Ukraine as a gigantic special economic zone on the fringes of Europe, where weak labor protections and lack of tariff barriers will incentivize investment from European multinationals.”

What is significant is that during the war, the Ukrainian government has taken control of a vast range of large enterprises belonging to Ukraine’s oligarchs. There is every possibility that these enterprises will sold off to foreign companies with many in the military taking a cut.

Every party on Ukraine’s political left has been banned based on largely unproven claims of collaboration with Russia. Welfare state institutions inherited from the Soviet era have gone. There is supposed to be a general election in Ukraine in October. That is in doubt but even if it goes ahead, any opposition to the government’s current legislation and economic policy is unlikely to get a hearing.

The other issue facing Ukrainians in achieving reconstruction is that much of this aid from the West is made up of loans, not grants and so Ukraine’s debt will be sky high for a generations ahead. The loans are mostly long term e.g. for 25 years (before the war the average of long-term loans was 15 years). And Ukraine will not have to repay its debt before 2033, according to EU Council. This is an unprecedentedly long grace period. But even with preferential interest, servicing EU loans will be expensive. To solve this, Brussels came up with the mechanism of “interest subsidy”: the interest will be paid by EU countries instead of Ukraine. The “interest subsidy” was already applied to Ukrainian loans in 2022. However, in 2023, a new feature has been added to the conditions of the new EU €18 billion loan: The subsidy is activated only if there is “compliance with political prerequisites.” So if Ukraine steps out of line eg proposing labour rights, increased social spending or refusing to privatise state assets, it would lose the right to these interest-free loans. According to the memorandum, in that case, the EU should stop the “interest subsidy.”

URC23 is preparing for a free market economy, which to quote the Ukrainian government’s own words, “confirms its commitment to deliver IMF Programme conditions, including adopting reforms to enable fair and open competition, reduce barriers to entry to markets, and ensure fair judicial and regulatory procedures.” The new Ukraine Development Fund (UDF) to be run by BlackRock and JP Morgan “will focus on mobilizing additional private capital and increasing the pipeline of bankable projects; offer flexible, tailored financing to fill early stage or structural financing gaps and de-risk private capital.” The UDF aims “to help address a $50+bn1 universe for private capital targeted by the UDF and other institutions investing in Ukraine across five key economic sectors, including: tech, logistics and transport corridors, green energy, natural resources, infrastructure reconstruction, digitalization, agriculture and food, health and pharmaceutics .”

There are rich pickings to be had, particularly in agriculture. Ukraine has more arable land for grain production that the whole of the size of Italy! If this land can be taken out of the hands of the smaller Ukrainian farmers and local oligarchs and sold to Western multi-nationals, the profits from food production will be immense. As the FT put it: “there are already companies on the cusp of moving in — especially in the low-hanging-fruit industries of construction and materials, agricultural processing and logistics. One Ukrainian minister told me that these were ready to go if only war risk insurance got better. The government is also making plans for a public development fund, which would ‘crowd in’ private investor money by providing the cushion of a loss-absorbing public stake in commercial investments.”

Ukraine could become a hub for Europe’s ‘green transformation’, given the country’s natural advantages in becoming a big supplier of carbon-free energy, green metallurgy and hydrogen. It could become a world-leader in digital technology to boost transparency and good economic management. The URC saw the launch of “Dream”, a digitised system for tracking all Ukrainian reconstruction projects from inception to completion, so donors anywhere in the world can see whose money is spent how and where. And of course, it will remain a major buyer of military equipment for the likes of the US arms manufacturers and contractors.

You could argue that Putin’s invasion has driven the Ukrainian people into the hands of a pro free market, anti-labour government that will allow Western capital to take over Ukraine’s assets and exploit its diminished workforce. But maybe that was inevitable – from pro-Russian and pro-West oligarchs before the war – now to Western capital afterwards.

June 14, 2023

Developing debt disaster

Next week 300 international organisations and 100 heads of state meet in Paris to discuss how “to build a more responsive, fairer and more inclusive international financial system to fight inequalities, finance the climate transition, and bring us closer to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.” This meeting is in Paris because it is the so-called Paris Club that for over the last 60 years has monitored and managed loans and credit by governments and government-guaranteed private banks to the so-called developing countries – loosely called the Global South these days.

The meeting takes place when the situation for large sections of the Global South in the post-pandemic period is dire. There is much talk in the Global North of rising interest rates causing banking crises and threatening bankruptcies for so-called ‘zombie companies’ overloaded with debt. But this is nothing to the economic and social damage that low-income, high debt countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America are suffering.

It is more than a year since I wrote a post entitled The submerging debt crisis, in which I described the economic stress being placed on small, low-income economies around the world from food and energy inflation, rising interest rates and a strong dollar. Then I identified Ghana, Sri Lanka, Egypt and Argentina. Indeed, back as far as the middle of pandemic in 2020, I highlighted the growing debt disaster for over 30 ‘emerging’ economies, with many of the poorest people on the planet.

In the pandemic, the IMF and the World Bank agreed a limited moratorium on these countries servicing and repaying their debts. But this was not a cancellation and the moratorium is now over. And there was nothing done by the Paris Club debts or about the huge debts owed to private banks and other financial institutions, which continued to demand their pound of flesh. And since the end of the pandemic, the sharp rise in interest rates on global debt and a strong US dollar (much of global debt is in dollars) have forced yet more countries to the brink of default on payments and into further poverty.

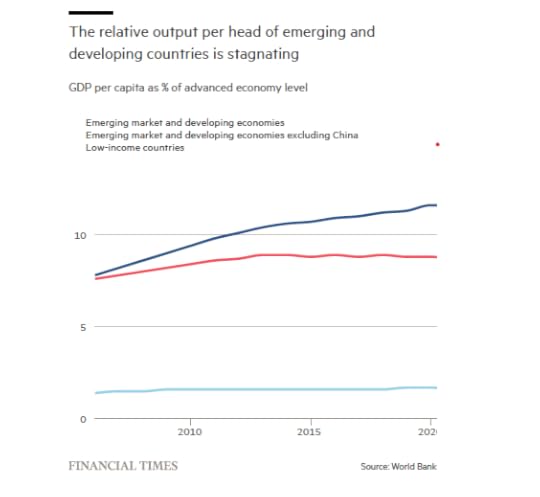

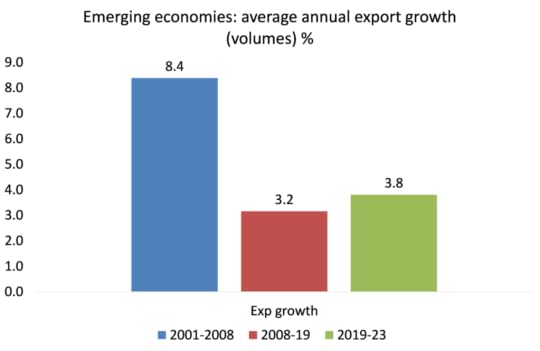

Most poor countries depend on selling raw materials and agricultural products or assembling manufacturing parts for the North. That means export revenues are vital to national income. But world trade growth has fallen away, particularly since the Great Recession of 2008-9 and even more since the pandemic. The volume of world trade grew at an average rate of 5.8% a year between 1970 to 2008, while GDP growth averaged 3.3%. But in the Long Depression of 2011 to 2023, average growth of world trade was a mere 3.4% a year, while global GDP growth averaged just 2.7%. Indeed, real GDP per head for the Global South, excluding China, has stagnated relative to advanced capitalist economies.

The reduction in world trade growth is particularly hard on ‘emerging’ economies. Export growth in the Global South economies has fallen by more than half the rate achieved prior to the Great Recession. And this measure includes China, the world’s largest exporting economy.

Source: CPD, MR calculations

World trade growth in the first quarter of 2023 now stands at -0.9%, following a decline of 2.0% in the final quarter of last year. Most regions showed a decline in merchandise trade during the most recent two quarters, signaling a further drop in goods trade, according to CPD. And now there is a global manufacturing recession.

Global manufacturing PMI (anything below 50 is recession).

Source: Trading Economics

The World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects paints a dire situation for many poorer economies. It says that the UN’s 2030 anti-poverty development goals are now “well off course”. The world’s poorest countries are expected to pay 35% more in debt interest bills this year to cover the extra cost of the Covid-19 pandemic and a dramatic rise in the price of food imports. More than an extra $100bn will be spent by the poorest 75 countries, many of them in sub-Saharan Africa, to cover loans taken out mostly over the past decade.

Debt payments are consuming more of government spending in poor countries when they were already struggling to provide education and health services. Wars and extreme weather events linked to the climate crisis are more likely to cause distress in low-income countries than elsewhere because of scanty social safety nets. On average, the poorest countries spend just 3% of GDP on their most vulnerable citizens – compared with an average of 26% for other economies.

Economic growth in developing economies other than China will fall from 4.1% in 2022 to 2.9% in 2023. World Bank chief economist Gill said: “By the end of 2024, per-capita income growth in about a third of EMDEs will be lower than it was on the eve of the pandemic. In low-income countries – especially the poorest – the damage is even larger: in about one-third of these countries, per capita incomes in 2024 will remain below 2019 levels by an average of 6%.” Fourteen low-income countries are already in, or at high risk of, debt distress, up from just six in 2015. As many as 21 countries are vulnerable.

Let’s just consider a few of those debt disasters.

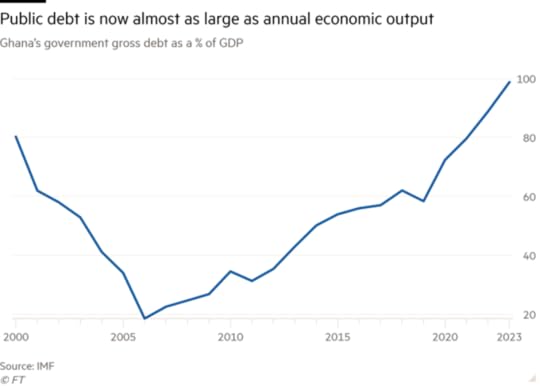

Ghana has long been considered a success story and a model for African development. It is a major producer of gold and cocoa and has one of the region’s highest GDP per head. But the government has now been forced into a $3bn IMF bailout when it defaulted on its debts last December. The government borrowed heavily to insulate the economy from the effects of the pandemic. As a result, public sector debt went from 62% of GDP in 2020 to more than 100% last year. Debt servicing now takes up about 70% of government revenues.

Ghana found itself shut out of international debt markets as concerns grew over its ability to repay what it owed. Now, in order to get the IMF funds, domestic lenders ie local banks, must accept a loss on their loans. But Ghana also has to get foreign lenders to take a ‘haircut’ on the $34bn in debt and that won’t be easy. Private lenders are responsible for 60% of the face value of Ghana’s external debt, but the high interest rates they charge mean they are responsible for 75% of debt payments. These lenders won’t take any haircuts without a fight. The Ghanian government has stopped borrowing any more and is imposing severe spending cuts on public services, such as they are. Taxes are being hiked – but this will only affect those in ‘formal’ employment. Most people work ‘informally’ with cash and many companies evade tax altogether. Corruption is rife.

Nearby Nigeria is also deep in trouble. Africa’s largest country is riven with internal wars, endemic corruption and waste of energy revenues. Foreign direct investment has dropped to its lowest levels in nine years: from $3bn in 2015 to $468mn. An extra 13m Nigerians are predicted to fall below the poverty line between 2019 and 2025.

Lebanon is a country that still has no government a year after national elections, with only a caretaker administration in place, and has been without a president for seven months. The former central bank governor is accused of corruption, money laundering and embezzlement. The Lebanese pound has lost more than 98% of its value against the dollar since 2019, while annual inflation climbed to 269% in April.

Over in Asia, a hugely populated country (230m), Pakistan, is in a deep political and economic crisis and is now turning to the IMF for a bailout. The country has $126bn in external debt and must repay $80bn of this over the next three years. The rupee has lost 50% of its value compared to the US dollar. FX reserves to cover payments are down to just $4.5bn. GDP is falling. The country has been hit by earthquakes and floods and is being run by the military, which sucks up much of government spending. Inflation is at an all-time of high of 38%.

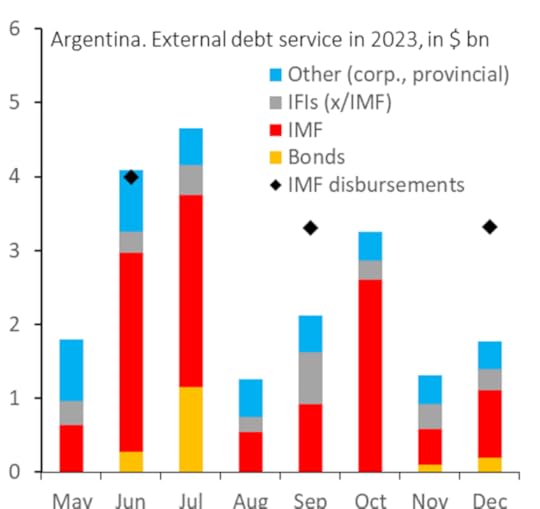

Then there is Argentina, one of the better-off ‘emerging’ economies. The economy is locked into chronic hyperinflation and debt. It has been forced yet again to go to the IMF for more funds to pay back what it already owes to it. The country faces big debt repayments this month and next.

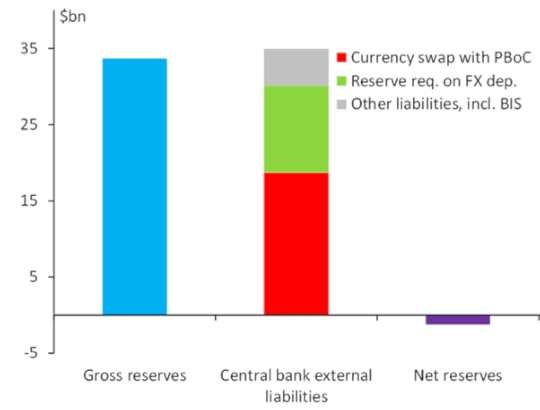

And FX reserves have run out. Argentina’s net reserves turned negative in May.

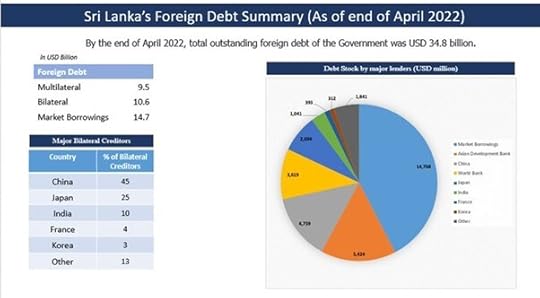

The Sri Lanka debt nightmare in 2021 culminated in mass protest and the fleeing of the then president from the country. But the debts remain. Much has been made of the debt owed to China, claiming that China is the problem by driving poor countries into a ‘debt trap’. But just 14% of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt is owed to China, while 43% is owed to private bondholders (largely Western vulture funds like BlackRock and banks like Britain’s HSBC and France’s Crédit Agricole). Another 16% is owed to the Asian Development Bank (over which the US has significant influence) and 10% is owed to the World Bank (dominated by the US as well). So “multilateral” debt really means debt owed to US-dominated institutions.

What is to be done? Clearly, the first immediate measure is to cancel the huge debts built up by these poor countries. The debts are the result of a weak world capitalist economy; corruption and mismanagement by local governments; and the rapacious squeeze on the resources and revenues by foreign lenders.

There is a significant concentration of holdings by a few major external creditors. Back in the 1990s the top-five external creditors accounted for 60% of total external credit to low-income countries and consisted mainly of multilateral and Paris Club creditors. As of end-2021, the concentration of the top-five external creditors had further increased, accounting for 75% of total external credit to LICs. And the share of debt owed to the private sector has approximately doubled from 8% to 19%. So if the IMF, World Bank and just a few key creditor countries agreed, the debts of the poor countries could be removed. Will the Paris meeting do anything about this? I doubt it.

Then there is the longer-term issue: the continual exploitation by the imperialist bloc, through their multi-national companies and financial institutions, of the labour of the Global South with the connivance of domestic corporations and governments of the local elite. Without a total restructuring of the world economy towards collective ownership and planning under workers governments, the debt misery will continue.

June 8, 2023

Modern supply-side economics and the New Washington Consensus

Last month, the US National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, outlined the international economic policy of the US administration. This was a pivotal speech, because Sullivan explained what is called the New Washington Consensus on US foreign policy.

The original Washington Consensus was a set of ten economic policy prescriptions considered to constitute the “standard” reform package promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, D.C.-based institutions such as the IMF, World Bank and the US Treasury. The term was first used in 1989 by English economist John Williamson. The prescriptions encompassed free-market promoting policies such as trade and finance ‘liberalisation’ and privatisation of state assets. They also entailed fiscal and monetary policies intended to minimise fiscal deficits and public spending. It was the neoclassical policy model applied to the world and imposed on poor countries by US imperialism and its allied institutions. The key was ‘free trade’ without tariffs and other barriers, free flow of capital and minimal regulation – a model that specifically benefited the hegemonic position of the US.

But things have changed since the 1990s – in particular, the rise of China as a rival economic power globally; and the failure of the neoliberal, neoclassical international economic model to deliver economic growth and reduce inequality among nations and within nations. Particularly since the end of the Great Recession in 2009 and the Long Depression of the 2010s, the US and other leading advanced capitalist economies have been stuttering. ‘Globalisation’, based on fast rising trade and capital flows, has stagnated and even reversed. Global warming has increased the risk of environmental and economic catastrophe. The threat to the hegemony of the US dollar has grown. A new ‘consensus’ was needed.

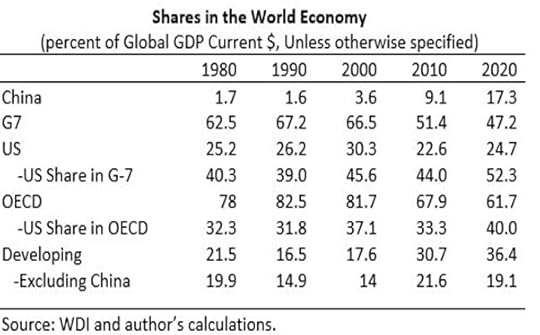

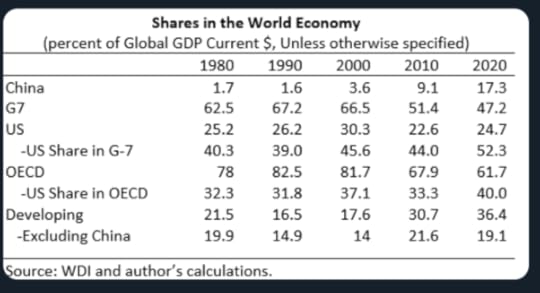

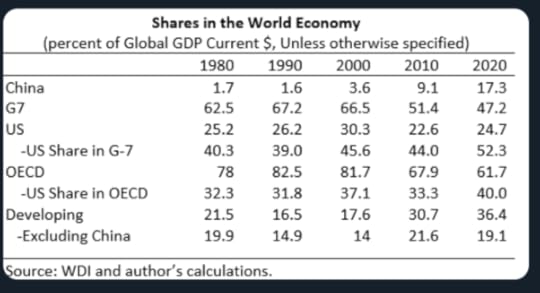

The rise of China with a government and economy not bowing to the wishes of the US is a red flag for US strategists. The World Bank figures below speak for themselves. The US share of global GDP rose from 25% to 30% between 1980 and 2000, but in the first two decades of the 21st century it fell back to below 25%. In those two decades, China’s share rose from under 4% to over 17% – ie quadrupling. The share for other G7 countries—Japan, Italy, UK, Germany, France, Canada—fell sharply, while developing countries (excluding China) have stagnated as a share of global GDP, their share changing with commodity prices and debt crises.

Source: Bert Hofman, World Bank data

The New Washington Consensus aims to sustain the hegemony of US capital and its junior allies with a new approach. Sullivan: “In the face of compounding crises—economic stagnation, political polarization, and the climate emergency—a new reconstruction agenda is required.” The US must sustain its hegemony, said Sullivan, but “hegemony, however, is not the ability to prevail—that’s dominance—but the willingness of others to follow (under constraint), and the capacity to set agendas.” In other words, the US will set the new agenda and its junior partners will follow – an alliance of the willing. Those who don’t follow can face the consequences.

But what is this new consensus? Free trade and capital flows and no government intervention is to be replaced with an ‘industrial strategy’ where governments intervene to subsidise and tax capitalist companies so that national objectives are met. There will be more trade and capital controls, more public investment and more taxation of the rich. Underneath these themes is that, in 2020s and beyond, it will be every nation for itself – no global pacts, but regional and bilateral agreements; no free movement, but nationally controlled capital and labour. And around that, new military alliances to impose this new consensus.

This change is not new in the history of capitalism. Whenever a country becomes dominant economically on an international scale, it wants free trade and free markets for its goods and services; but when it starts to lose its relative position, it wants to change to more protectionist and nationalist solutions.

In the mid-19th century, the UK was the dominant economic power and stood for free trade and international export of its capital, while the emerging economic powers of Europe and America (after the civil war) relied on protectionist measures and ‘industrial strategy’ to build their industrial base. By the late 19th century, the UK had lost its dominance and its policy switched to protectionism. Then by 1945, after the US ‘won’ WW2, the Bretton Woods- Washington consensus came into play, and it was back to ‘globalisation’ (for the US). Now it’s the US’ turn to move from free markets to government-guided protectionist strategies – but with a difference. The US expects its allies to follow its path too and its enemies to be crushed as a result.

Within the New Washington Consensus is an attempt by mainstream economics to introduce what is being called ‘modern supply-side economics’ (MSSE). ‘Supply-side economics’ was a neoclassical approach put up as opposition to Keynesian economics, which argued that all that was needed for growth was the macroeconomic fiscal and monetary measures to ensure sufficient ‘aggregate demand’ in an economy and all would be well. The supply-siders disliked the implication that governments should intervene in the economy, arguing that macro-management would not work but merely ‘distort’ market forces. In this they were right, as the 1970s onwards experience showed.

The supply-side alternative was to concentrate on boosting productivity and trade, ie supply, not demand. However, the supply-siders were totally opposed to government intervention in supply as well. The market, corporations and banks could do the job of sustaining economic growth and real incomes, if left alone. That too has proved false.

So now, within the New Washington Consensus, we have ‘modern supply-side economics’. This was outlined by the current US Treasury Secretary and former Federal Reserve chair, Janet Yellen in a speech to the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Yellen is the ultimate New Keynesian, arguing for both aggregate demand policies and supply-side measures.

Yellen explained: “the term “modern supply side economics” describes the Biden Administration’s economic growth strategy, and I’ll contrast it with Keynesian and traditional supply-side approaches.” She continued: “What we are really comparing our new approach against is traditional “supply side economics,” which also seeks to expand the economy’s potential output, but through aggressive deregulation paired with tax cuts designed to promote private capital investment.”

So what’s different? “Modern supply side economics, in contrast, prioritizes labor supply, human capital, public infrastructure, R&D, and investments in a sustainable environment. These focus areas are all aimed at increasing economic growth and addressing longer-term structural problems, particularly inequality”

Yellen dismisses the old approach: “Our new approach is far more promising than the old supply side economics, which I see as having been a failed strategy for increasing growth. Significant tax cuts on capital have not achieved their promised gains. And deregulation has a similarly poor track record in general and with respect to environmental policies—especially so with respect to curbing CO2 emissions.” Indeed.

And Yellen notes what we have discussed on this blog many times. “Over the last decade, U.S. labor productivity growth averaged a mere 1.1 percent—roughly half that during the previous fifty years. This has contributed to slow growth in wages and compensation, with especially slow historical gains for workers at the bottom of the wage distribution.”

Yellen directs her audience of mainstream economists to the nature of modern supply side economics. “A country’s long-term growth potential depends on the size of its labor force, the productivity of its workers, the renewability of its resources, and the stability of its political systems. Modern supply side economics seeks to spur economic growth by both boosting labor supply and raising productivity, while reducing inequality and environmental damage. Essentially, we aren’t just focused on achieving a high top-line growth number that is unsustainable—we are instead aiming for growth that is inclusive and green.” So MSSE-side economics aims to solve the fault-lines in capitalism in the 21st century.

How is this to be done? Basically, by government subsidies to industry, not by owning and controlling key supply-side sectors. As she put it: “the Biden Administration’s economic strategy embraces, rather than rejects, collaboration with the private sector through a combination of improved market-based incentives and direct spending based on empirically proven strategies. For example, a package of incentives and rebates for clean energy, electric vehicles, and decarbonization will incentivize companies to make these critical investments.” And by taxing corporations both nationally and through international agreements to stop tax-haven avoidance and other corporate tax avoidance tricks.

In my view, ‘incentives’ and ‘tax regulations’ will not deliver supply-side success any more than the neoclassical SSE version, because the existing structure of capitalist production and investment will remain broadly untouched. Modern supply-side economics looks to private investment to solve economic problems with government to ‘steer’ such investment in the right direction. But the existing structure depends on the profitability of capital. Indeed, taxing corporations and government regulation is more likely to lower profitability more than any incentives and government subsidies will raise it.

Modern supply economics and the New Washington Consensus combine both domestic and international economic policy for the major capitalist economies in an alliance of the willing. But this new economic model offers nothing to those countries facing rising debt levels and servicing costs that are driving many into default and depression.

The World Bank has reported just this week that, economic growth in the Global South outside of China will fall from 4.1% in 2022 to 2.9% in 2023. Battered by high inflation, rising interest rates and record debt levels many countries were growing poorer. Fourteen low-income countries are already at high risk of, debt distress, up from just six in 2015. “By the end of 2024, per-capita income growth in about a third of EMDEs will be lower than it was on the eve of the pandemic. In low-income countries – especially the poorest – the damage is even larger: in about one-third of these countries, per capita incomes in 2024 will remain below 2019 levels by an average of 6%.”

And there is no change in the lending conditions of the IMF, the OECD or the World Bank: indebted countries are expected to impose austere fiscal measures on government spending and to privatise remaining state entities. Debt cancellation is not on the agenda of the New Washington Consensus. Moreover, as Adam Tooze put it recently that “Yellen sought to demarcate boundaries for healthy competition and co-operation, but left no doubt that national security trumps every other consideration in Washington today.” Modern supply-side economics and the New Washington Consensus are models, not for better economies and environment for the world, but for a new global strategy to sustain US capitalism at home and US imperialism abroad.

Modern supply economics and the New Washington Consensus

Last month, the US National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, outlined the international economic policy of the US administration. This was a pivotal speech, because Sullivan explained what is called the New Washington Consensus on US foreign policy.

The original Washington Consensus was a set of ten economic policy prescriptions considered to constitute the “standard” reform package promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, D.C.-based institutions such as the IMF, World Bank and the US Treasury. The term was first used in 1989 by English economist John Williamson. The prescriptions encompassed free-market promoting policies such as trade and finance ‘liberalisation’ and privatisation of state assets. They also entailed fiscal and monetary policies intended to minimise fiscal deficits and public spending. It was the neoclassical policy model applied to the world and imposed on poor countries by US imperialism and its allied institutions. The key was ‘free trade’ without tariffs and other barriers, free flow of capital and minimal regulation – a model that specifically benefited the hegemonic position of the US.