Michael Roberts's Blog, page 16

January 8, 2024

ASSA 2024 part one: the mainstream: growth uncertainty, inflation confusion, climate paralysis

ASSA, the Alliance of Social Science Associations, holds the biggest annual economic conference in the world. It is hosted by the American Economics Association and this year was held in San Antonio, New Mexico. Over 13,000 economics students and professors attend and hundreds of papers are presented in sessions over three days. And there are addresses by the ‘great and good’ of mainstream economics, attended by hundreds. But also, there are sessions organized by radical economics group, attended by handfuls.

Let us start by discussing some of the mainstream economics sessions. I reckon we can single out three main issues taken up at the big meetings: the state and future of the US economy; why there was an inflationary surge after COVID; and whether climate change and global warming can be curbed or stopped.

One session was entitled: Where is the economy headed? The panellists in this session expressed ‘uncertainty’ about the direction of the US economy over the next few years because of the ‘jolts’ from the COVID pandemic and its impact on commercial real estate (home working), possible banking crises and ‘geopolitical instabilities’. “These instabilities, in particular, make the path forward less predictable and less resilient to systemic shock.” said Janice Eberly of Northwestern University

What was surprising is that the panellists seemed most worried about the size of the public debt and fiscal deficits weakening the US economy. It seems that the mainstream is still obsessed with reducing the size of the public sector and spending, rather than addressing any faultlines in the dominant capitalist sector of the economy. James Hines of the University of Michigan forecast that by 2030 the cost of servicing the public debt (interest and bond repayments) would exceed all tax revenues and then there would have be cuts in public spending – even defence spending (shock!). And this was the real obstacle to growth in the US economy.

The comforting thought, however, Hines said was that the US “does capitalism” better than any other country, with strong entrepreneurial companies and well organised financial and public institutions to ensure that US capitalism works. “Most of the things that are going to be helpful are going to come from free markets—lots of trade, lots of investment,” said Hines. What about the high and rising inequality of income and wealth in the US?, a questioner asked. Yes, this was concerning was the reply, and economists needed to consider the problem carefully…. but no answer was offered.

Then there was the question of artificial intelligence – would this provide a new boost to productivity and take the US economy up and away? The panellists were cautious, pointing out that often technology innovations remain confined to their sectors and do not diffuse across the economy. However, sometimes, the current equilibrium can be ‘punctuated’ by a disruptive innovation that transforms the economy, said Eberly (by the way the use of the term ‘punctuated equilibrium’ comes from the paleontology work of Steven Jay Gould and Niles Eldridge, who argued that things don’t change just gradually, but sometimes can leap forward.

In another session on the US economy, Glenn Hubbard, former economic adviser to the Trump presidency, was hopeful that AI would be a big boost to US growth, but much depended on getting public finances under control and reducing unnecessary regulation of industry and finance. In the same session, the well-known ‘debt’ economist, Kenneth Rogoff reckoned the AI could overcome the productivity growth slowdown that the US and other major economies are suffering from but such a ‘turning point’ would also depend on avoiding a debt crisis especially in developing economies engendered by high interest rates imposed by central banks in the ‘fight against inflation’.

And indeed, the cause of the post-pandemic inflation burst dominated many mainstream sessions at ASSA 2024. In one big session, attendees were presented with every possible mainstream theory on the cause of inflation.

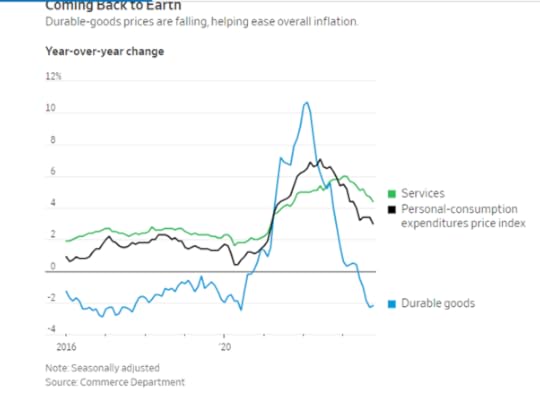

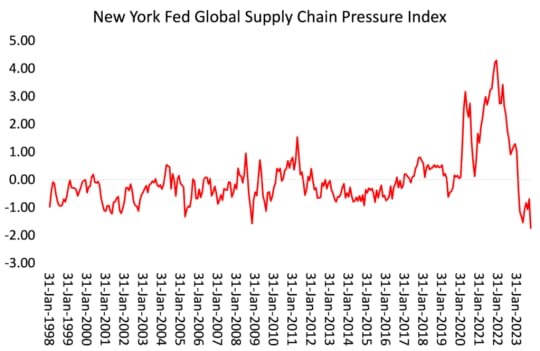

“We didn’t really understand why inflation spiked in the first place. So maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that it came down faster than we thought, too,” said Hines. There is now a wide body of evidence that the inflationary spiral from 2021-23 was mainly cause by supply blockages and the poor recovery of production and international trade in goods, as well as by companies in key sectors taking the opportunity to hike their prices in order to preserve profit margins.

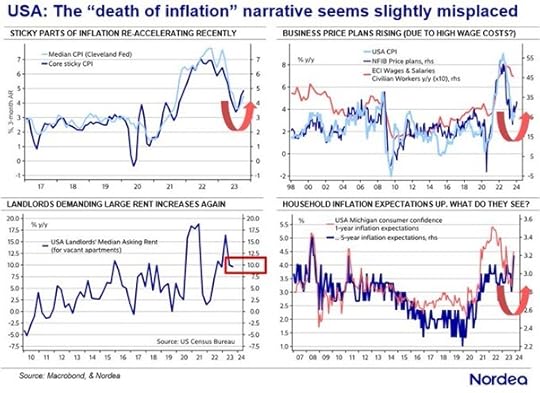

But nearly all the presenters in this session spent their time trying to find other reasons for the inflationary spiral, sticking to their old mainstream theories that inflation is caused by ‘excessive demand’ generated either by too much money being injected into the economy (monetarism) or by too much government spending (austerianism); or in the case of the Keynesians by tight labour markets driving up wages.

Take the Keynesian case. A leading Keynesian macroeconomist Gauti Eggertsson from Brown University did his best to revive the failed Phillips curve, namely that if unemployment falls towards full employment, this will push up wages and that will lead to increased inflation. Eggertsson agreed that the traditional Phillips curve did not apply to current inflation, BUT, you see, the curve has become ‘non-linear’ ie unemployment can fall straight down without any impact on inflation and then suddenly turn a corner and inflation jumps. That’s why you can get full employment and no inflation for much of the time – until now.

Eggertsson agreed that it was ‘supply-side shocks’ that caused inflation to rise and now that the supply-side blockages have receded, inflation rates have fallen. But he wants to save the Keynesian theory as well, by arguing that lower inflation has only been possible because of a ‘non-linear’ Phillips curve. Ironically, the reverse of the non-linear curve is that any new supply blockages could cause a sharp spike back up in inflation rates.

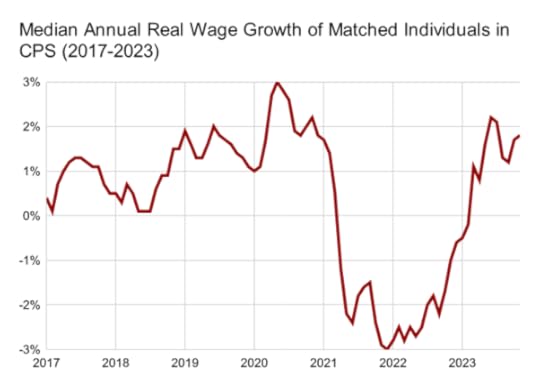

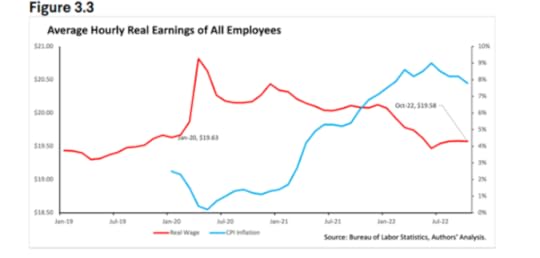

Whether you agree with the Keynesians’ attempt to preserve their labour market theory (and it is hard to do so, in my opinion), given that wage rises never kicked off inflation in the first place and always fell behind the inflation rate until recently, it is another argument against the monetarist view that the Federal Reserve adjustment of interest rates had any effect on reducing inflation in the last year.

Yet the monetarists were still present at ASSA. One of the most famous is John Taylor, author of the Taylor rule which supposedly sets limits on how to avoid inflation or unemployment by manipulating the ‘right’ interest rate to be set by the Fed. At ASSA, Taylor told his audience that the inflationary spiral was due to the Fed being too lax on hiking rates even before the pandemic and not following his Taylor rule. Then they hiked and now they should reverse.

Then there are the ‘Austerians’. They argue that the inflationary burst was caused by ‘too much’ government spending. Governments ran annual budget deficits and so drove up debt levels and this generated ‘excessive demand’ that was not productive for growth and also made Federal Reserve interest rate policy ineffective.

Robert Barro, a conservative economist from Harvard, who has always been obsessed with reducing government spending which he sees as ‘crowding out’ the private sector, presented evidence for 37 OECD countries that “fiscal expansion underlies the surge in inflation for 2020-2022.” In my view, this is a classic case of not recognizing the causal direction. Fiscal spending relative to output rose sharply during the pandemic because economies were closed down. When economies begin to recover, the size of budget deficits compared to GDP will fall (and they have). What Barro also argued was that the Fed’s high interest rates policy would not reduce inflation but just provoke banking crises as in last March and “a recession by 2024, likely mild unless the financial crisis turns out to be severe.”

Christopher Sims from Princeton University also promoted this ‘fiscal theory of inflation’ as against the Keynesians. He argued that since 1950 the US had suffered three bouts of high inflation and they were caused by ‘fiscal expansions’: it’s overspending by governments that causes high inflation, not lax monetary policy (a la Taylor above).

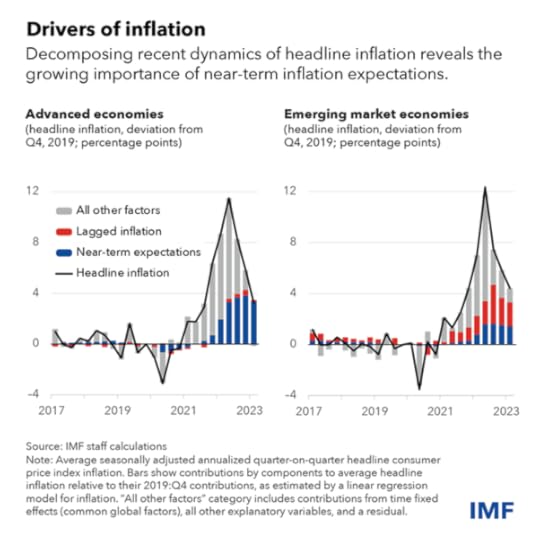

Finally, there was the ‘trendy’ theory of inflation expectations. The IMF under director Gita Gopinath, having seen that monetarist, fiscal and Phillips curves theories don’t explain the recent inflation, have turned to ‘inflation expectations’. The idea is that people think prices are going to rise and so buy more things, thus causing ‘excessive demand’ and thus rising prices. In a recent blog, the IMF economists claim that since 2020, ‘near-term inflation expectations’ have been the biggest driver of price increases in advanced economies and the second biggest factor in emerging markets.

At a special lunch session, MIT professor Ivan Werning gave a long presentation trying to show that inflation expectations played the most important role in boosting recent inflation. His conclusion was that rising inflation was caused by consumers ‘overshooting’ their expectation of price rises and so delivering the very thing they were trying to avoid. So rising inflation is the result of ‘irrational expectations’ by consumers. Thus the theory of inflation is reduced to psychology.

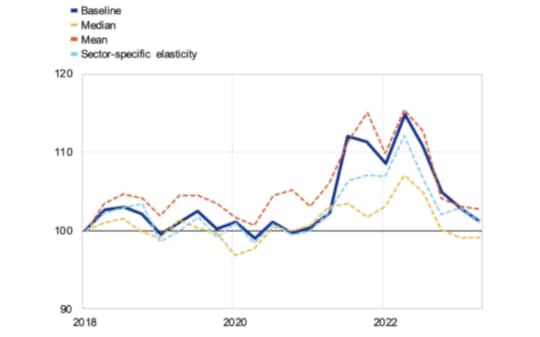

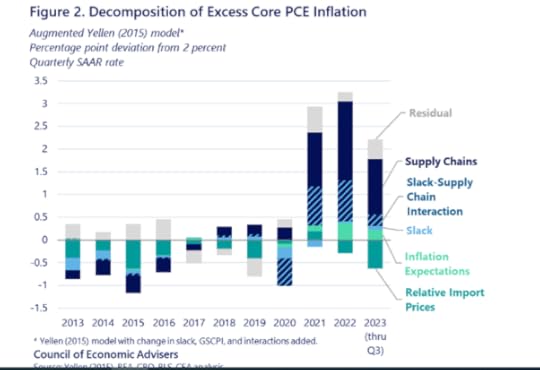

But if you look at the IMF graph above closely, you can see that ‘other factors (ie supply blockages) were the main factor kicking off rising inflation and ‘expectations’ only came later, once people realized that prices were going to continue to rise sharply. Expectations follow real causes. As Keynesian Larry Summers summed it up recently: “The theory to which many economists are gravitating to is that the Phillips curve is basically flat, inflation is set by inflation expectations, and inflation expectations are set by the people who form inflation expectations. And that’s a little bit like the theory that the planets go around the universe because of the orbital force. It’s kind of a naming theory rather than an actual theory. So I think inflation theory is in very substantial disarray, both because of the Phillips curve problems and because we don’t have a hugely convincing successor to monetarist-type theory.”

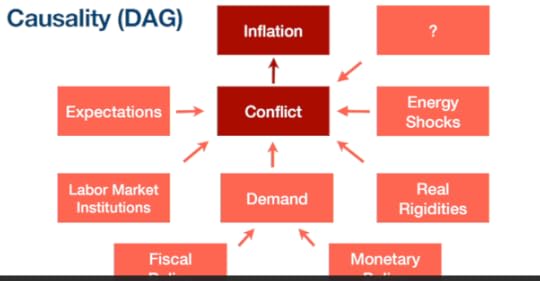

In his presentation, Werning attempted to come up with an inflation theory that covered all the bases. It all starts with too much demand caused by too much money injections from the central bank and by too much government spending. Then there are various rigidities (monopolies, trade unions etc) that push up prices and by energy price shocks; and finally inflationary expectations.

This cocktail of causes leaves with us with no explanation at all. No wonder Werning summed his address with the words: “that often we end up knowing less than we knew before” but that’s science for you.

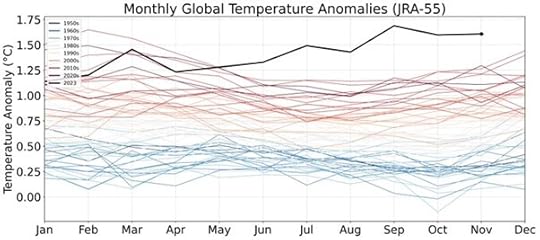

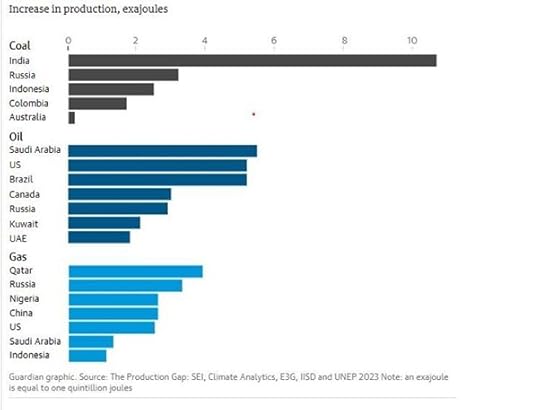

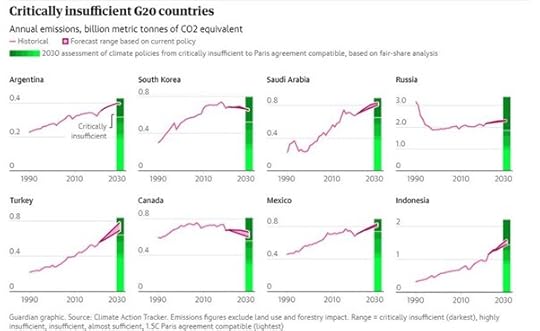

The other mainstream debate was around climate change and global warming. The main mainstream method of estimating the impact of global warming on economies has been by what are called Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), first developed by Nobel prize winner William Nordhaus. And the main policy answer is to introduce carbon pricing and taxes. I have discussed the merits (or not) of IAMs and policy solutions in previous posts. But nothing has changed among the mainstream at ASSA 2024. These are still the methods and policies advocated.

On the method, Steve Keen, a heterodox economist, has produced a blistering critique of IAMs and how they understate hugely the impact on global warming on economies and the planet. See this latest piece by him. For example, (from Steve Keen), the IAM “assumed that empirical relationships derived from data on change in temperature and GDP between 1960 and 2014 can be extrapolated out to 2100—thus assuming that 3.2°C more of global warming won’t alter the climate!: They have assumed that tipping points—critical features of the Earth’s climate such as the Greenland and West Antarctic icesheets, the Amazon rainforest, and the “Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation” which keeps Europe warm today—can be tipped with only minimal additional damage to GDP”.

As for policy, as we well know after COP28, nowhere near enough is being done by governments or companies to stop the accelerating rise in global warming and its impact on the planet. That’s because sustaining the fossil fuel industry is more important than sustaining species on the planet and living standards for the majority. of humanity. There was nothing at ASSA mainstream sessions that recognised this.

January 2, 2024

Forecast 2024: stagnation, elections and AI

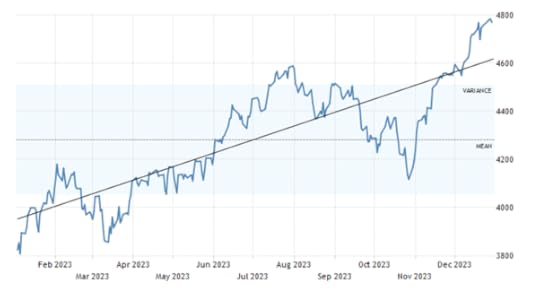

2023 ended with the US stock market hitting a record high.

US S&P-500 index

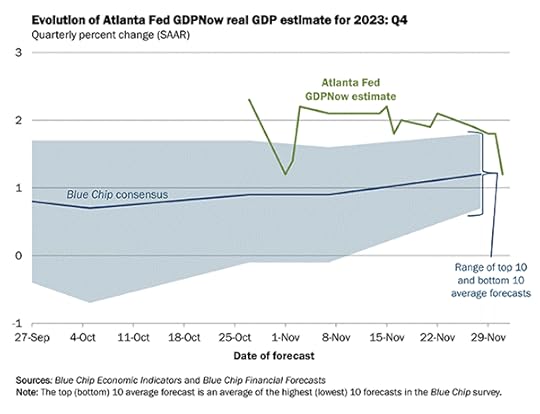

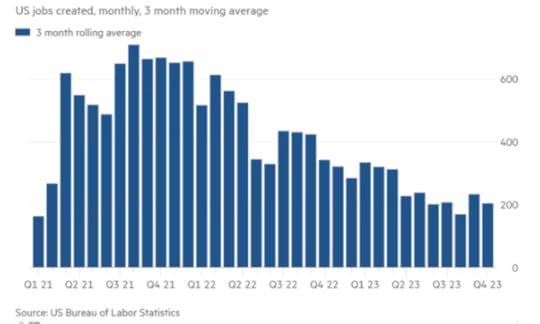

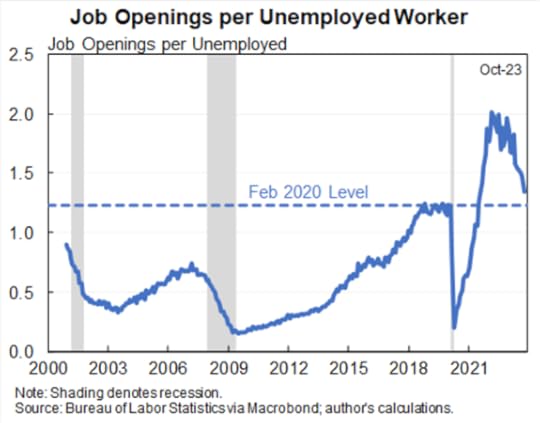

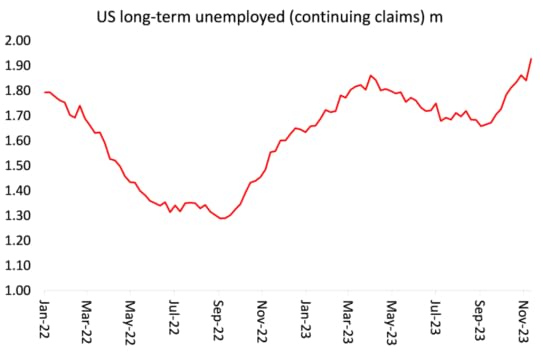

Financial markets and mainstream economists breathed a sigh of relief that the US economy had not dropped into a recession i.e. technically two consecutive quarters of contraction in real national output. Instead, despite the Federal Reserve hiking its policy rate to a 15-year high, US real GDP rose by about 2.0-2.5% in 2023, possibly slightly higher than in 2022. At the same time, the consumer inflation rate dropped from an average 8% in 2022 to 4.2% in 2023 with the latest figure at just 3.1%. Unemployment did not rise averaging 3.6%, the same as 2022, although there were signs of it ticking up in the last few months.

So the consensus of economic forecasts at the beginning of 2023 proved wrong. As I wrote in my 2023 forecast entitled ‘The impending slump’: “it seems most leading forecasters are agreed – a slump is coming in 2023, even if they hedge their bets on the depth and in which regions.”

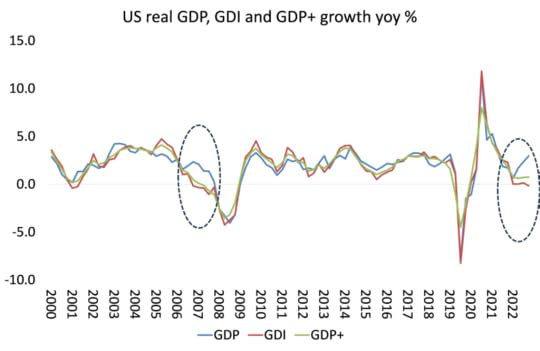

But as I have said in previous posts, the GDP measure seems a bit of an outlier compared to the measure of economic activity based on gross domestic income (GDI). There has been no growth at all in real national income (i.e. profits plus wages). If we average these two different rates, then US economic growth has been about half the GDP rate and considerably slower than in 2022.

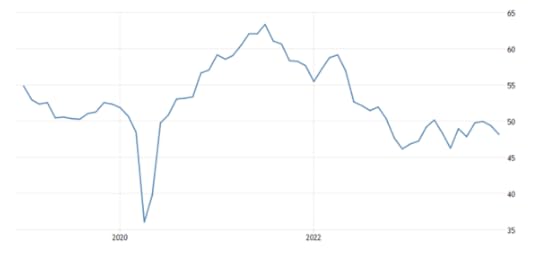

Why the significant difference in 2023? The main reason is that GDP growth has not been transformed into increased sales and revenue at the same rate. Stocks of goods produced have instead built up. US manufacturing industry is in fact mired in the longest slump in more than two decades. Activity in the manufacturing sector has weakened for 13 straight months, the longest stretch since 2002, according to surveys of purchasing managers (PMI) by the Institute for Supply Management.

US manufacturing PMI (below 50 = contraction)

Indeed, when price inflation of goods in the shops and online is accounted for, US retail sales volumes are down compared to 2022.

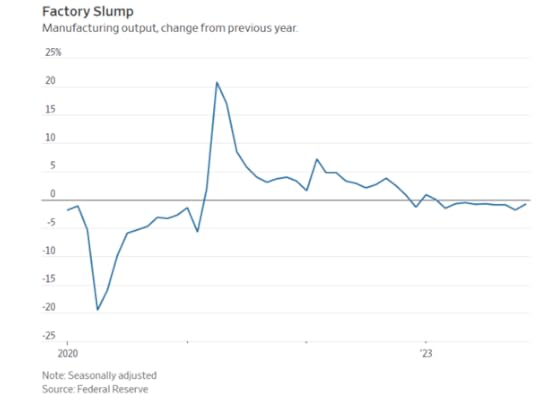

And manufacturing output is also falling.

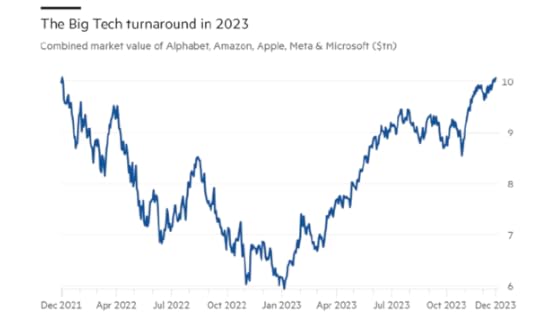

It’s only the large so-called services sector in the US that has expanded. And in that sector, the fastest growth has been in healthcare, education and, of course, technology. Technology boomed in 2023, as government subsidies for technology companies mushroomed. The Inflation Reduction Act offered tax incentives for renewable-energy equipment manufacturers and buyers of electric vehicles. The Chips and Science Act included $39 billion in subsidies for semiconductor makers.

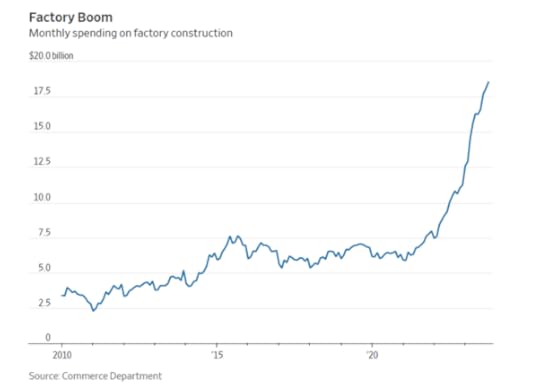

Spending on manufacturing construction (mainly IT) rose almost 40% in 2022 and is up a further 72% through the first 10 months of 2023 versus the same period the previous year.

“You’ve got these acyclical drivers that are really pushing up investment in manufacturing structures just in this one sector, but the broader sector is still struggling,” said Bernard Yaros, lead US economist at Oxford Economics. Investment in factories has occurred in the most high-tech sliver of the sector, while other industries struggle with a pandemic-induced inventory overhang and higher interest rates.

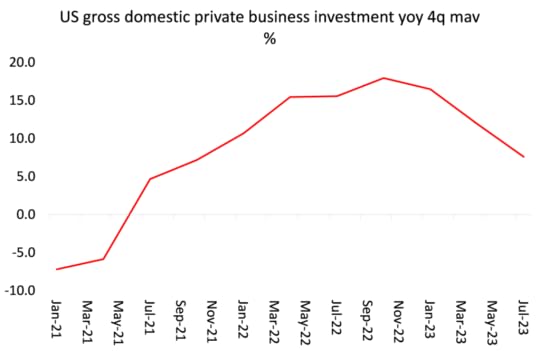

Business orders of capital goods, excluding aircraft and military goods, have been falling for about two years (after adjusting for inflation), according to the Commerce Department.

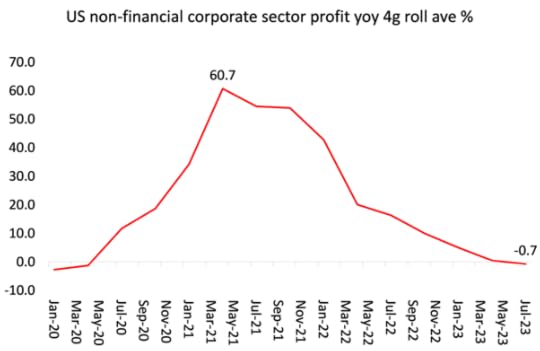

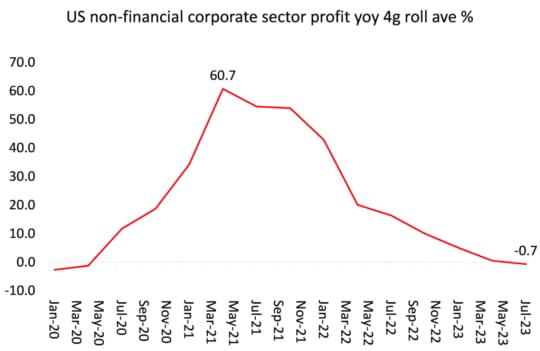

So even if the technology sector is growing and profitable, the rest of US business is not doing so well. Non-financial sector corporate profits are up only 3% on last year so far and are now falling.

And all this is in the US, the strongest of the G7 economies since the end of the pandemic.

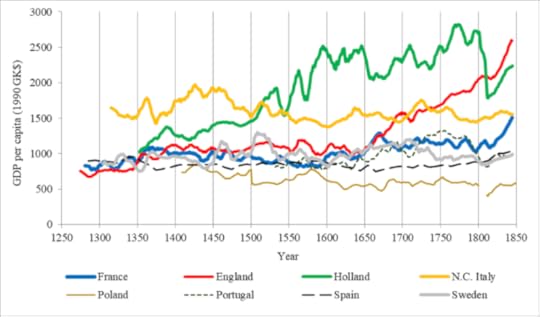

But note, even in the US, the trajectory of growth is lower than before the Great Recession of 2008-9 and is no better than during the average of the 2010s. Europe has performed poorly since the Great Recession and even worse since the end of the pandemic. In 2023, in Europe, Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany entered a recession, with the UK, Italy and France close to it. Canada is in recession and Japan close to it.

But what about 2024? This time, the consensus view is not for a recession in the US or globally. Douglas Porter, chief economist at BMO Capital Markets Economics sums the consensus up. “I expect most major economies to grow more slowly in 2024 than in 2023, but rate cuts, cooling energy and food prices, and normalized supply chains will stave off a global recession.”

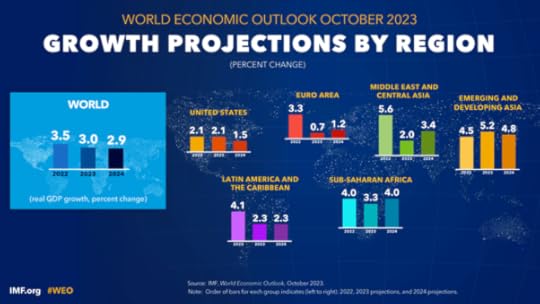

Let’s consider those claims. For a start, the consensus is still for even slower global growth than in 2023. I quote the IMF forecast made in October 2023: “The baseline forecast is for global growth to slow from 3.5 percent in 2022 to 3.0 percent in 2023 and 2.9 percent in 2024, well below the historical (2000–19) average of 3.8 percent. Advanced economies are expected to slow from 2.6 percent in 2022 to 1.5 percent in 2023 and 1.4 percent in 2024 as policy tightening starts to bite. Emerging market and developing economies are projected to have a modest decline in growth from 4.1 percent in 2022 to 4.0 percent in both 2023 and 2024.”

This does not look like a booming 2024 in the US or globally.

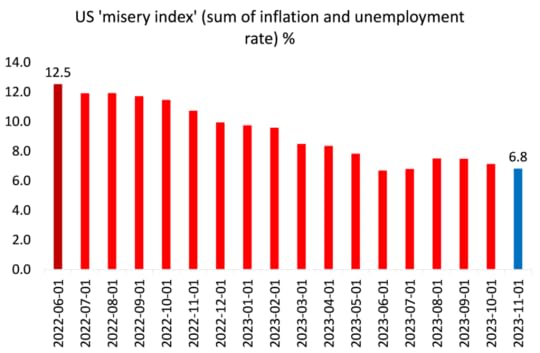

But there seems to be a peak in central bank policy interest rates. So financial markets are now expecting significant reductions during 2024, starting as early as March. Inflation rates are falling everywhere in the major economies and unemployment has not risen – as I showed above. Indeed, the so-called ‘misery index’ (the sum of inflation and unemployment rate) in the US and other major economies has halved 18 months.

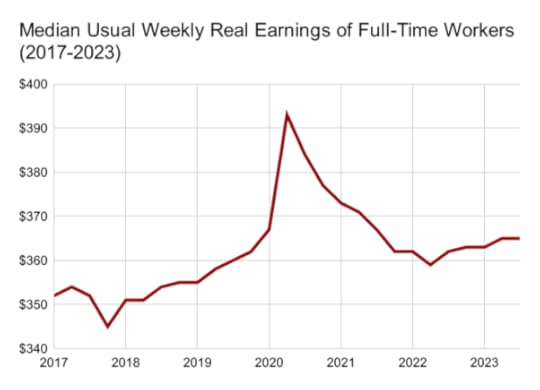

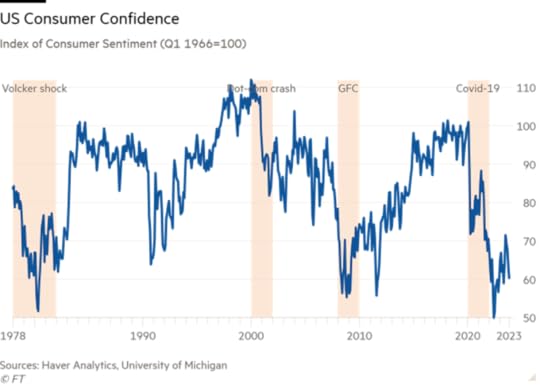

What is puzzling many is that the US economy at least is apparently achieving a ‘soft landing’ from the pandemic, with inflation down, unemployment low and average real incomes beginning to rise, but the American public still seems depressed and uncertain about the future.

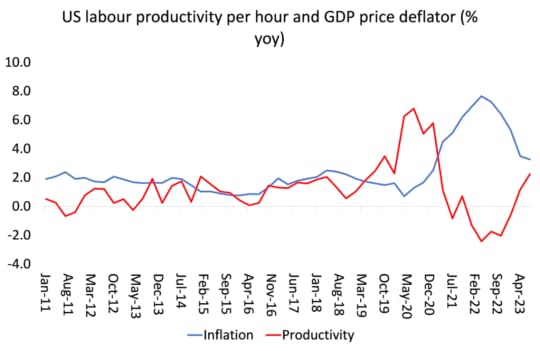

The problem is that inflation has only fallen by half and remains well above the pre-pandemic level of under 2%. And that fall is almost entirely due to the end of supply blockages caused by the pandemic and the eventual fall in energy and food prices. As many have explained, it has had little to do with the monetary policy of the central banks.

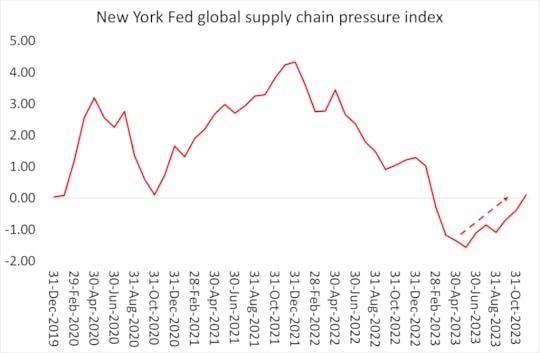

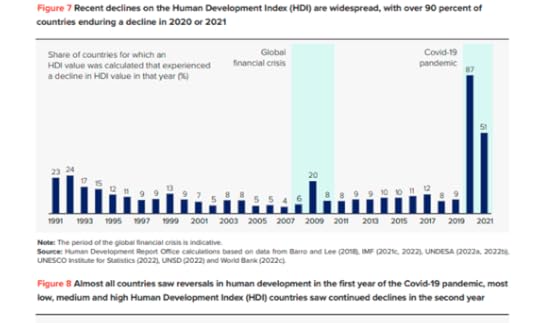

The misery index may be down, but most households in the US, Europe and Japan are still suffering the after-effects of the pandemic slump. Prices in Europe and the US are higher by about 17-20% compared to the end of the pandemic. Jobs may be plentiful, but in general they do not pay well and are often part-time or temporary. Moreover, the continuing war in Ukraine and now the horrendous decimation of Gaza could lead to a reversal of the past fall in global supply chain pressure – according to the New York Fed index.

And what is missing from all these optimistic forecasts is the state of so-called emerging or developing economies of the Global South. Take China, India and Indonesia out of the equation and the rest of these economies, particularly the poorest and often most populous, are facing a another year of a severe debt crisis, which has seen mounting defaults by poor country governments and companies on their debt.

I have discussed this in many previous posts and even though interest rates might eventually start falling later in 2024, the impact on the ability of many countries to meet their ‘obligations’ to the rich countries’ investment funds and banks and to the international agencies will be even weaker this year than last.

All this suggests that, although the US economy technically avoided a slump in 2023, which could have triggered a global contraction, the optimistic sounds of this year’s consensus could again prove wrong – this time in the opposite direction.

That’s the economy in 2024. But there is also politics. 2024 is the year of elections. There are 40 national elections slated, the effects of which will cover 41% of the world’s population, in countries representing 42% of global GDP.

The most important election will be the US presidential poll in November, the result of which has the potential to destabilise every economy and financial market. Donald Trump says that the stock market and the economy are only staying strong because everybody expects him to win in November. If he does not, “then there will be a new Great Depression.” Well, that prognosis does not seem likely – indeed the opposite might well be the case if he loses. But there is no certainty about who will win; or whether Biden will actually stand again; or whether either Trump or Biden would even serve another full term.

Russia too has a presidential election, but there the result is clear and guaranteed, not just because the levels of the media, election commissions and state control are entirely in the hands of Putin and any opposition is suppressed, but also because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has actually boosted his popular support. The Russian economy has avoided a slump and indeed has grown in the last year, driven by mainly military spending.

In Europe, there are the European Assembly elections in June which are expected to see a significant swing to the anti-immigrant, anti-EU integration rightist parties, which are also opposed to further support by the EU for Ukraine. But the current ‘centre’ right pro-Israel, pro Ukraine parties will probably maintain a majority. Portugal holds an election that will almost certainly throw out the Socialists who have been embroiled in a corruption scandal.

And here in the UK there will be a general election this year. The opposition Labour party, now controlled and run by a pro-business right-wing faction, looks set to win over an incompetent and corrupt Conservative government, no longer even supported by its increasingly crazed and aged party members. But a Labour government would merely continue with ‘business as usual’ in both domestic economic policy and in uncritical support for US global hegemony.

The other big election is in India, where again the incumbent ex-fascist president Modi, in power since 2014, looks set to walk the election, given India’s strong economic growth and the disarray of the opposition parties. Across the border, in Pakistan, things will be very tense as the current right-wing government backed by the military aims to defeat the party of former PM Imran Khan, who fell out with the military. In neighbouring Bangladesh, the incumbent autocratic government will win as the opposition is set to boycott the elections.

Votes in Indonesia and South Korea will probably lead to the status quo of pro-capitalist governments. The African National Congress is likely to hang on in South Africa at May elections as the opposition is split, but the ANC may dip below 50% of the vote for the first time since the end of apartheid.

Claudia Sheinbaum, incumbent President Andrés Manuel Lopez-Obrador’s preferred candidate, leads the polls by a huge margin in Mexico. Another key election is in Venezuela. Through an agreement reached with the US, sanctions against the country have been relaxed in return for holding general elections. The US aim is to bring about the end of the Maduro government through a popular vote.

It’s just a fortnight before the general election in Taiwan where the pro-independence governing party looks like retaining the presidency over the more pro-mainland China parties. This could ratchet up the tensions between the US and China.

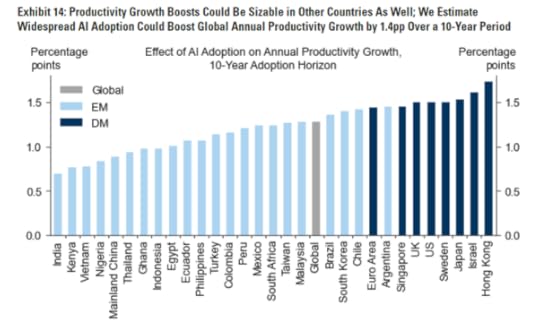

2024 could also be the year when the impact on productivity and jobs of the rise of generative AI becomes clearer. The techno-optimists like Goldman Sachs are drooling at the prospect of sharp increases in US productivity growth over the rest of this decade, mainly achieved by massive reductions of jobs in many service sectors.

In 2024, spending on generative AI next year will amount to little more than $20bn, or 0.5% of total global IT spending, says John-David Lovelock, chief forecaster at IT research firm Gartner. By comparison, IT buyers will spend five times as much on security, he adds. Yet Goldman Sachs estimates that investment in AI will jump in the latter part of this decade to reach more than 2.5% of GDP by 2032.

Even if that happens, that may not deliver a generalised increase in productivity growth. The great internet revolution of the late 1990s produced a stock market boom, bubble and bust, but it did little to boost growth in the overall productivity of labour in the 2000s onwards. As the recently deceased mainstream economic expert on the impact of technology on productivity, Robert Solow, commented at the time, “You can see the computer age everywhere, but in the productivity statistics.” Productivity growth has been slowing globally as a trend throughout the first two decades of this century.

The hope of the optimists is that AI and LLMs will kick-start a ‘roaring 20s’, similar to that experienced in the US after the end of the Spanish flu epidemic from 1918-20 and the subsequent slump of 1920-21. But some things are different now. In 1921, the US was fast-rising manufacturing power, sweeping past war-torn Europe and a declining Britain. Now the US economy is in relative decline, manufacturing is stagnating and the US faces the threat of the rise of China, forcing it to conduct proxy wars globally to preserve its hegemony.

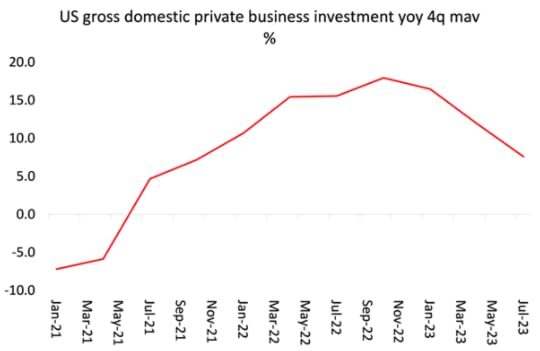

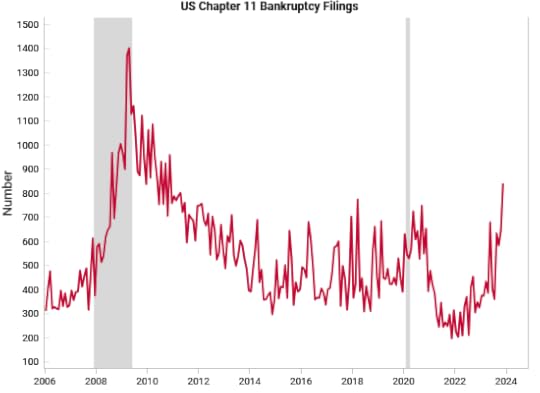

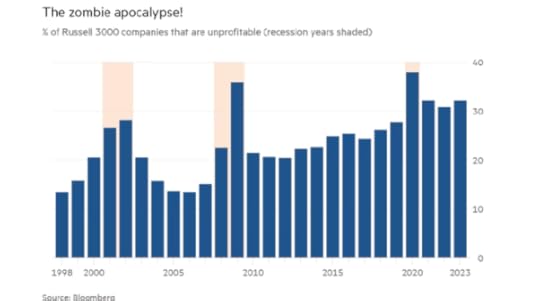

Much more likely is that 2024 will be another year of what I have called a Long Depression that began after the Great Recession of 2008-9, similar to the depression of the late 19th century from 1873-95 in most major economies then. Unless average profitability sharply rises, then business investment growth across the board will remain low even if AI boosts productivity in some sectors. To get a step-change in the profitability of global capital would require a major cleansing (slump) to remove the weak (zombies) and raise unemployment in low-value sectors. So far, such a ‘liquidation’ or ‘creative destruction’ policy has not gained support in the mainstream or in official policy circles. ‘Muddling through’ is better.

In sum, 2024 looks like being one of slowing economic growth for most countries and probably more slipping into recession in Europe, Latin America and Asia. The debt crisis in those countries in the so-called global south that don’t have energy or minerals to sell will worsen. So even if the US avoids an outright slump again this year, it wont feel like a ‘soft landing’ for most people in the world.

December 31, 2023

Top ten posts of 2023: AI, polycrisis, banking and inflation

2023 was the 13th year since I launched this blog. Over those years, I have posted 1194 times with over 5.23 million viewings and over 2m visitors. There are currently 7572 regular followers of the blog; and now 13670 followers of the Michael Roberts Facebook site, which I started eight years ago. On that Facebook site, I put short daily items of information or comment on economics and economic events. Please follow.

And at the beginning of 2020, I also launched the Michael Roberts You Tube channel, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCYM7I0m-I9EVB-5gaBqiqbg/. This now has 2960 subscribers. If you haven’t joined up yet, have a look at the channel, which includes presentations by me on a variety of economic subjects; interviews with other Marxist economists; and some zoom debates in which I participated.

My top three videos of 2023 were: Henryk Grossman with Rick Kuhn; Capitalism in the 21st century on our new book with Mino Carchedi; and what would Marx and Engels say about the 21st century capitalism. I hope to do some new videos very soon.

This year I also launched a Twitter site. https://twitter.com/BlogRoberts That has not taken off with only 129 followers. That’s partly because the blog and my Facebook site cover the same things and Twitter requires much more work on a daily basis. I’ll try and boost it this coming year, although it seems in general that Twitter is beginning to flag in social media. Watch that Twitter space.

As for the blog, 2023 saw 488,000 views, down from last year and the record COVID year when everybody was stuck at home online. But I did 83 posts this year, up from 77 last year and those that read them stayed on the site for more views with an average 2.76 views per visitor – a record.

Where do my blog viewers come from? From over 199 countries globally! Led by 114k yearly viewings in the US (or about 24%); 60k from UK (14%); then all the G20 and BRICs countries. Brazil and Spain are the next largest viewers followed by Canada, Argentina, Germany and Australia. Right at the other end of the spectrum, I have had viewings from Vanuatu, Greenland, Yemen, Mali, Timor, New Caledonia and Gabon.

So what was the top post of this year? It was my post on AI-GPT. The rise of generative AI was the big technology event of the year and so, not surprisingly, it attracted the interest of blog followers. In that post, I discussed the strength and faults in the new Language Learning Models LLMs) with some examples; the likely impact of LLMs of jobs in many occupations and whether new technology leads to a net loss or rise in jobs; and whether AI really will surpass and replace human intelligence.

A second post on ChatGPT and whether knowledge can have value in Marxist terms also got into the top ten. In this post, my close colleague in Marxist economics, Guglielmo Carchedi, discussed the production of knowledge and how it could be commodified under capitalism. This provoked a lot of debate in comments when he said: “to believe that computers are capable of human thinking is not only wrong; it is also a pro-capital ideology because that is being blind to the class content of the knowledge stored up in labour power and thus to the contradictions inherent in the generation of knowledge.”

What happens with AI is something for the future, but the next most popular post was for here and now. It was analysis of the current contradictions in 21st capitalism caused by the Long Depression in the world economy in the last decade and the coming together of a bunch of crises: climate change; rising inequality; the after-effects of the COVID pandemic on human development globally; the rising geopolitical conflicts; and the significant decline in confidence about the future of humanity.

The other big issue that absorbed blog readers was the policy of central banks to control inflation through hiking interest rates to post-2009 highs this year. In one post I argued that central bank interest rate hikes were not going to bring inflation down because the rise in inflation was not due to ‘excessive demand’ or ‘excessive wage increases’ but to supply blockages, poor recovery in manufacturing and falling international trade after the end of the pandemic.

By the end of this year, the evidence was overwhelming that inflation was a supply-side matter (including rising profit margins) and, in that sense, ‘transitory’ – although it remains to be seen if inflation rates ever get back to pre-pandemic levels.

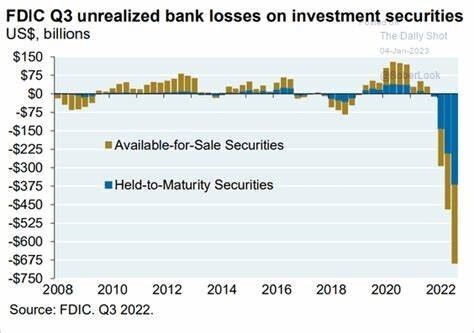

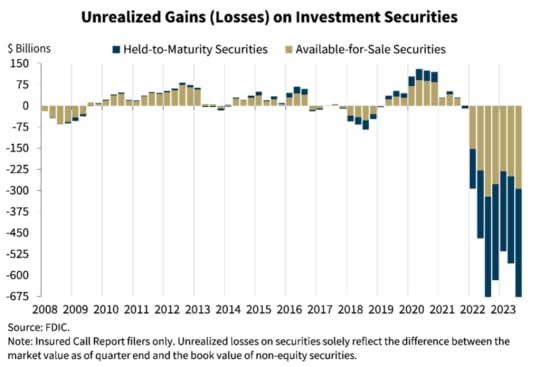

What rising interest rates did lead to were bank failures like SVB, the reasons for which I described in another popular post.

Indeed, there were a surge of failures in small US regional banks last March and the collapse of the huge Credit Suisse bank in Europe. That led to bailouts and central bank credit injections to stabilize the financial sector.

In another post, I again pointed out the uselessness of so-called regulation of the financial sector to stop such crashes. As David Kane at the New Institute for Economic Thinking put it, as “the instruments assigned to this task are too weak to work for long. With the connivance of regulators, US megabanks are already re-establishing their ability to use dividends and stock buybacks to rebuild their leverage back to dangerous levels.” Kane notes that “top regulators seem to believe that an important part of their job is to convince taxpayers that the next crash can be contained within the financial sector and won’t be allowed to hurt ordinary citizens in the ways that previous crises have.” But “these rosy claims are bullsh*t.”

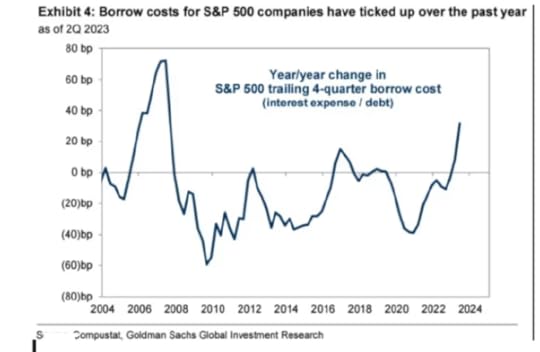

In another post I argued that the banking crisis last March could return because interest rates are set to stay high for some time and companies are stocking up sizeable debt servicing costs while profit growth is slowing.

‘Zombie’ companies are growing in number – companies where profits are not even sufficient to cover debt servicing costs so they have to borrow even more to survive. But the traditional process of ‘cleansing’ of the weak under capitalism through a slump has been avoided by yet more injections of credit (loans and bonds). The Federal Reserve balance sheet rose during banking crisis (graph). ‘Creative destruction’ has been replaced by ‘moral hazard’ as monetary policy.

Interestingly, my post on pensions got into the top ten. The story was built around the pension cut protests in France last March. Pensions are not just important to older people but also to young workers – with the knowledge that state pensions will never be adequate on retirement.

In the post I opposed the mainstream economic arguments that ‘we cannot afford proper state pensions’ any more unless we raise the retirement age and/or contributions from wages. I put it this way: “Does a country want to use its resources so that people can stop work at the age of 60 or 65 and have enough income to live on in reasonable comfort, or not? It can be done.” It depends on two things: first, that an economy creates enough resources and expands sufficiently to cater for its elderly population that may also be getting larger as a share of the population. And second, given finite resources, decent pensions can be provided by cutting out other calls on government revenues i.e. such as bailing out the banks; increased arms spending; more subsidies for private corporations to invest in fossil fuels; and lower taxes for top earners and corporations etc.

Indeed, just a 1% pt sustained rise in average real GDP per capita in the major economies could deliver enough extra revenue to governments to easily maintain current pension levels and terms with something to spare.

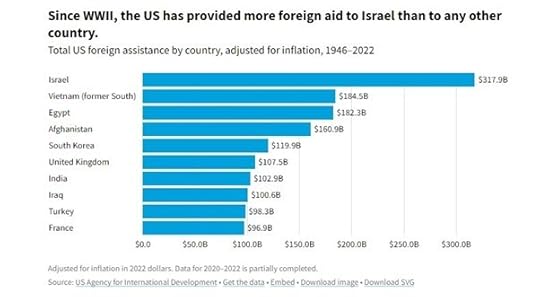

The Israeli horrendous decimation of Gaza starting last October compelled me to write something about the economic rise of the Israeli state. I called it ‘a shattering of a dream’ – I now think that was a wrong title because, even back in 1947, those who thought Israel would build a model democratic socialist state were a naïve minority. The driving force for Israel from the beginning was capitalist investment to establish a bulwark for imperialism in the Middle East. But I did outline the economic story of Israel for readers, particularly the huge inequalities or wealth and income within Israel.

The last post to make the top ten was the recent one of the debate between two Marxist scholars on Marx’s meaning of a ‘commodity’ and the implications for understanding the contradictions of within the capitalist mode of production. The comments on the blog continue.

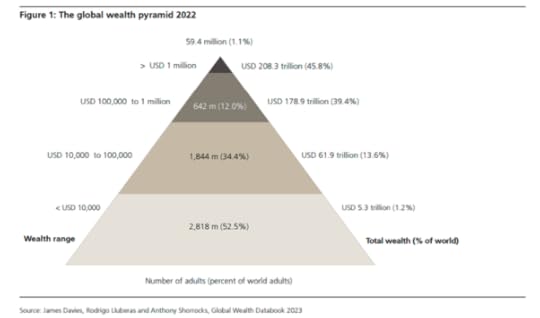

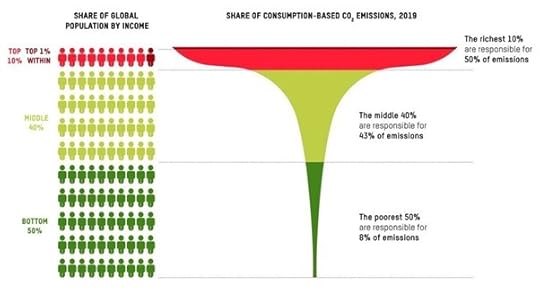

Just to finish, you might want to know what the top post of all time was on the blog. The winner was the post on global wealth inequality (repeated every year) showing a pyramid with the top 1% of wealth holders (about 50m) having 40-45% of all net personal wealth globally, while around 3bn adults in the world have next to nothing. Not far behind were my posts on the economics of the pandemic, a Marxist theory of inflation, the debate I had with David Harvey on Marx’s value theory, measurement of the rate of profit on capital and my critique of modern monetary theory.

You can find these posts through the search tab on the blog.

December 28, 2023

Books of the year

Every year at this time, I look back at the books that I have reviewed during the year on this blog.

Let me start with the The Big Con: How the Consulting Industry Weakens our Businesses, Infantilises our Governments and Warps our Economies. by Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington.

Mazzucato has built up a big reputation for espousing the benefits of public investment and the public sector over the private. scanning her popularity from the left in the labour movement through to mainstream governments in Europe and Latin America. In this new book, Mazzucato and Collington expose the scam that the management consultancy business is.

Their premise is that consulting is really a confidence trick. “A consultant’s job is to convince anxious customers that they have the answers, whether or not that’s true”. The authors point out that governments and companies everywhere rely on consultancies, companies that ‘talk the talk’ but know little about the problems they claim to solve. Billions are parted everywhere to the likes of McKinsey and other ‘management consultancies’ with little resulting benefit. The ‘management consultancy con’ is really a product of neo-liberal ideology that the private sector knows best and will be more efficient than public sector workers doing the job. Mazzucato and Collington expose the scam but are vague about what to do about it. Still an eye-opening book on the myth that work for profit is more ‘efficient’ than work for need.

Branco Milanovic is the world’s greatest expert on global inequality of wealth and income. In 2023 he published yet another book, Visions of Inequality.

This takes a different approach from analysing the stats on inequality. Instead Milanovic discusses those he considers provide the most important explanations of why inequality of wealth and income is so great between humans. As Milanovic puts it: “The objective of this book is to trace the evolution of thinking about economic inequality over the past two centuries, based on the works of some influential economists whose writings can be interpreted to deal, directly or indirectly, with income distribution and income inequality. They are François Quesnay, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx, Vilfredo Pareto, Simon Kuznets, and a group of economists from the second half of the twentieth century (the latter collectively influential even as they individually lack the iconic status of the prior six).” The latter includes Thomas Piketty.

In my review, I concentrated on Milanovic’s account of Marx’s view. Milanovic unfortunately accepts many misconceptions about Marx’s value theory and the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, which I think leads him to conclude that a falling rate of profit will mean reduced inequality because it is the rise in real wages that lowers profitability. I think this confuses the rate of surplus value with the rate of profit.

Nevertheless, Milanovic correctly argues that Marx considered that any distribution of income and consumption was only a consequence of the distribution of the conditions of production. The capitalist mode of production rests on the fact that the material conditions of production are in the hands of non-workers in the form of property in capital and land, while the masses are only owners of their personal condition of production, of labor power. Thus, the distribution of income and wealth cannot be changed in any material way until the system is changed. “To clamor for equal or even equitable remuneration on the basis of the wages system,” Marx writes, “is the same as to clamor for freedom on the basis of the slavery system.”

“For all that we are told we live in an increasingly dematerialised world where ever more value lies in intangible items – apps and networks and online services – the physical world continues to underpin everything else.” So starts Ed Conway, economics editor at the British Sky TV channel, in his fascinating little book, Material World.

The vast bulk of the world economy is still built on the production of things, ‘stuff’ that can be commodified from the labour of billions. The material world, as Conway calls it, is still the basis of the global economy. Conway singles out just six key materials that drive the world economy in the 21st century: sand, salt, iron, copper, oil and lithium. They are the most widely used and the very hardest to replace. In the book, Conway takes us on a journey of history and technology surrounding these key resources.

Conway notes two things that Marx’s value theory predicts – of course, unknowingly. “As the amount of stuff we remove from the ground and turn into extraordinary products continues to increase, the proportion of people needed to make this happen decreases.” Thus there is a continual rise in what Marx called the organic composition of capital.

And the other is that capitalist production takes no account of what mainstream economics calls ‘externalities’, the ‘collateral damage’ to the environment for humans and the rest of the planet. “There are no environmental accounts or material flow analysis, which count only the refined metal. When it comes to even the United Nations’ measures of how much humans are affecting the planet, this waste rock doesn’t count.” Conway ends his book with the great contradiction of the 21st century: global warming and climate change. How can the world get to ‘net zero’ when it needs so many raw material resources?

Can technology do the trick? This is the issue that Daren Acemoglu poses in his book, Power and Progress – a thousand- year struggle over technology and prosperity’, jointly authored with Simon Johnson. Acemoglu is a leading economist on the impact of technology on jobs, people and economies. I have referred to his work before in various posts.

In Power and Progress, we get a sweeping historical account of how technology has taken humanity forward in terms of living standards but also often created misery, poverty and increased inequality. The book considers what can be done to ensure that the gains from the productivity ‘bandwagon’ of modern technology like robots, automation and AI can be spread among the many and not just garnered by the few.

The authors fall back on the ‘policy levers’ of taxation and subsidies to research; regulation of markets; the breaking up of the big tech monopolies; and stronger trade unions. All these measures in one form or another have failed sufficiently to achieve the spread of the gains of technology in the past and would for the current innovations – assuming these policies were ever to be implemented. What Power and Progress tells us about technology and its impact on our lives, for good or bad, is that whoever has the power gets the benefit.

On the same theme of the impact of technology, Matteo Pasquinelli authors a book called In the eye of the master, which argues that, whereas in the past labour was supervised and controlled by the masters ( the owners and their agents, the managers), now supervision will be increasingly automated. So, instead of AI and automation being used collectively by us all, machines will rule our lives for the benefit of the master.

The theme of an increasingly authoritarian state is raised in a new book, entitled, The rise and fall of American Finance by Stephen Maher and Scott Aquanno.

The authors argue that the ‘financialisation’ of capitalism since the 1980s has not weakened the capitalist mode of production but changed and strengthened its ability to exploit with the support of “an increasingly authoritarian state.” The authors claimed that they were arguing differently from “strict financialist theorists” by not claiming “a qualitatively new phase of capitalist development is emerging” but just the same interlocking of finance, industry and the state that has always existed in capitalism.

What to do about this authoritarian state? The authors’ policy conclusions are vague, namely that: “reducing economic inequality and bringing investment in “Good Jobs” back to the United States requires challenging the competitive logic of global financial integration with state-imposed barriers on the movement of investment worldwide.” Or to be clearer: “establishing a greater public role in determining the allocation of investment”. That seems somewhat feeble if capitalism is taking a more repressive formation.

Two of my book reviews have caused some controversy among readers and others. The first is Dependency theory after 50 years, by Claudio Katz. Katzo delivers a comprehensive account of dependency theory as expounded mainly in Latin America over the last 50 years.

Dependency theory is really a theory of imperialism. Dependency’ can take different meanings but in essence it identifies two main groups of countries in the global economic system: the core and the periphery. The core countries are wealthy countries that control the global economy. The periphery countries are poor countries that are dependent on the core countries for trade, investment and technology. ie prosperity.

Katz concentrates his account of dependency theory on its Marxist variant, which argues that these countries will remain ‘dependent’ because of the huge extraction of value from labour in their economies to the imperialist bloc through trade, finance and technology. What Katz does show is that Marx’s value theory of “productive globalization based on the exploitation of workers remodels the cleavages between center and periphery through transfers of surplus value.” And it is “the omission of that mechanism prevents the critics of dependency from understanding the logic of underdevelopment.”

I have got some stick from supporters of the theory because of my criticism in my review of Argentine Marxist economist Mario Marini who developed a theory of ‘super-exploitation’ and the idea of ‘sub imperialism’, ie small imperialist countries. Even though I have doubts about the validity of these two concepts in explaining modern imperialism, Katz does show how Marini seemed close to a classic Marxist view that imperialist gains are a product of ‘unequal exchange’ in international trade and the general extraction of surplus value from the periphery.

Long standing Marxist scholar, Fred Moseley presented a new book entitled Marx’s theory value in, Chapter one of capital: a critique of Michael Heinrich’s value form interpretation. The book discussed the debate over the meaning of the value form of commodities under capitalism.

Moseley interprets Marx to argue that there is a common property of all commodities that determines their value, namely the objectified abstract human labour contained in commodity production. Leading Marxist scholar Michael Heinrich argues, on the other hand, that labour in production is only concrete labour and abstract labour comes to exist only in exchange.

It’s a complicated plot but the debate does have important implications for our understanding of capitalism. For me, Marx’s analysis of the value in a commodity is about showing the fundamental contradiction in capitalism between production for social need (use-value) and production for profit (exchange value). Units of production (or commodities under capitalism) have that dual character which epitomises that contradiction. In my view, Heinrich loses that contradiction by arguing that Marx meant a commodity only has value when it is sold for money on the market and not before in production through the exploitation of human labour.

It is no accident that Heinrich dismisses Marx law of profitability as illogical, ‘indeterminate’ and irrelevant to explaining crises and instead looks excessive credit and financial instability as causes. Heinrich even claims that Marx dropped his law of profitability – although the evidence for that is non-existent. If profits (surplus value) from production by human labour disappear from any analysis to be replaced by profits from exchange for money, then we no longer have a Marxist theory of crisis or any theory of crisis at all.

December 23, 2023

Marx’s value theory and the value form interpretation

This post is long but something well worth reading during the festive break.

As I mentioned in a recent blog, at the Historical Materialism conference in London in November, there was a book launch for Fred Moseley’s new book Marx’s Theory of Value in Chapter 1 of Capital: A Critique of Heinrich’s Value-Form Interpretation. Michael Heinrich and Winfried Schwarz (a German Marxist who is also critical of Heinrich’s interpretation) participated in the book launch.

Moseley’s book is an examination of Marx’s theory of value in Chapter 1 of Capital, almost paragraph by paragraph in Sections 1 and 2, and a detailed critique of Heinrich’s value-form interpretation of Chapter 1, as presented in his 2021 book How to Read Marx’s Capital, which is a translation of his 2018 book Wie das Marxsche Kapital Lesen?

Heinrich is a well-known German Marxist who has published widely on his value-form interpretation of Marx’s theory of value, and his work is influential not only in Germany, but also in the UK and other countries in Europe and around the world. He criticises the traditional interpretation of the labour theory of value, according to which the value of commodities is determined solely in production, and he argues that value is created only when it is converted into money through the sale of commodities on the market.

Moseley is one of the foremost scholars in the world today on Marxian economic theory. He has written or edited many books on Marxist theory. He reckons instead that Marx presented a labour theory of value according to which the value of commodities is determined solely in production by the socially necessary labor time required to produce the commodities. And Moseley argues in his book that the textual evidence in Chapter 1 overwhelmingly supports the labour theory of value interpretation of Marx’s theory of value.

The relevance and importance of this debate may seem obscure to many readers of Marx. So Fred Moseley kindly agreed to be interviewed on his new book and the controversy with Heinrich.

MR: How did this book come about?

FM: ”First of all, I want to thank you for the opportunity to discuss my book with you and your many readers.

Heinrich’s book cited above is a detailed textual study of the first seven chapters of Capital. Heinrich is not very well known in the US, but he is very influential in Germany and other European countries. He is something like a David Harvey of Europe. But I am convinced that Heinrich’s book is a fundamental misinterpretation of Marx’s theory, so I decided to engage critically with Heinrich’s book.

I started by writing a paper on Chapter 1, the foundation of Marx’s theory and Heinrich’s interpretation. I presented this paper in a Zoom conference in June 2021 sponsored by Gyeongsang National University in South Korea. An assistant editor of Palgrave’s Marx, Engels and Marxism series, Paula Rauhala, watched the my presentation and she contacted me and suggested that I write a longer version of my paper as a Palgrave Pivot book. A Pivot book is a new initiative by Palgrave of short books, with a limit of 50,000 words (which I exceeded by 10,000 words!). I am grateful to Paula for that suggestion and this little book is the result.”

MR: Please give us an overview of your book

FM: “My little book is a detailed textual study of Marx’s Chapter 1 and Heinrich’s interpretation of Chapter 1. The book consists of only 4 chapters.

Chapter 1 of this book presents my interpretation of Marx’s theory of value in Chapter 1 of Capital, including a section on each of the four sections of Marx’s Chapter 1. Chapter 2 presents Heinrich’s interpretation of Chapter 1 of Capital and my detailed critique of Heinrich’s interpretation 1, with the same four sections.

Chapter 3 is about a 55-page manuscript that Marx wrote in 1872 in preparation for the 2nd German Edition of Volume 1, which is mainly about Section 3 of Chapter 1, entitled ‘Additions and Changes to the First Volume of Capital’, which Heinrich has emphasised in his book and in previous works to provide textual support for his ‘value-form interpretation’ of Chapter 1. This important manuscript has not yet been translated into English. A translation of a 4-page excerpt of this manuscript is included in Heinrich’s book as an appendix. So Chapter 3 of my book presents my interpretation of this manuscript and a critique of Heinrich’s interpretation. A translation of this entire manuscript should be a high priority of Marxian scholarship.

My book is very abstract theory, about the most abstract part of Marx’s theory, the beginning of Marx’s theory in which he presents the foundation of his labour theory of value. Marx said in the Preface to the 1st edition of Volume 1 of Capital that “beginnings are always difficult in all sciences”, and that is certainly true of Marx’s theory. The best way to read my book is to have Heinrich’s book and Volume 1 of Capital close at hand.”

MR: How would you summarise the main conclusions of your book?

FM: “The main conclusions of my book are the following:

1. The subject of analysis of Chapter 1 is the commodity, not a separate, isolated commodity, but a representative commodity, a commodity that represents all commodities and the properties that all commodities have in common (use-value and exchange-value). In the Preface to the 1st edition, Marx described the commodity as the “elementary form” or the “cell form” of capitalist production. So Marx analyses the properties of a representative commodity similar to the way cellular biology analyses the properties of a representative cell. It’s like putting a commodity under a microscope and analysing its main properties.

Marx’s representative commodity in Chapter 1 is assumed to have been produced, but not yet exchanged. This is crucial for the critique of Heinrich’s interpretation. According to Heinrich, the subject of analysis of Chapter 1 is not the properties of a representative commodity, but instead is what he calls an “exchange relation” between two commodities, which he argues is the end result of two actual exchanges between the two commodities and money on the market.

2. The value of commodities is derived in Section 1 of Chapter 1 from the property of the exchange-value of the representative commodity (i.e. from the property that each commodity is equal to all other commodities in definite proportions). And this general relation of equality between each commodity and all commodities requires a common property that is possessed by all commodities and that determines the proportions in which different commodities are equal.

Marx argued that this common property of all commodities that determines their exchange-values is the objectified abstract human labour contained in commodities. And this is the result of the abstract human labour expended in production to produce the commodities.

According to Heinrich, on the other hand, the value of commodities is not derived from a relation of equality between all commodities, but instead is derived from an analysis of an “exchange relation” between two commodities, which he argues presupposes actual exchanges of the two commodities with money on the market.

3. The magnitude of the value of each commodity is “exclusively determined” (p. 129) by the quantity of socially necessary labour-time expended in production to produce each commodity. Heinrich argues, on the other hand, that the magnitude of value of a commodity depends in part on the relation between supply and demand for the commodity on the market. This is the best-known assumption of the value-form interpretation of Marx’s theory of value.

4. The labour that produces commodities has a dual character in production: both concrete labour and abstract labour are characteristics of the same labour process in production. Section 2 of Chapter 1 in particular presents very strong textual evidence to support this interpretation of the dual character in production of labour that produces commodities.

Weaving and tailoring are Marx’s two examples in Section 2. The labour process of weaving produces the use-value of linen, its dual character also being abstract human labour that produces the value of the linen. The same dual character is true of the labour process of tailoring (and all other particular labour activities). The values of the linen and the coat are compared by comparing the labour-time required to produce each one of them and nothing is said in this about exchange in this section.

Heinrich argues, on the other hand, that labour in production is only concrete labour and is not yet abstract labour. Abstract labour comes to exist only in exchange, and thus the dual character of the labour that produces commodities comes to exist only in exchange. According to Heinrich’s interpretation, tailoring and weaving (and any other labour process) possess only a single character in production, not a dual character. This interpretation is clearly contradicted by Section 2.”

MR: Please say more about Heinrich’s interpretation of “exchange relation”. That seems to be a central concept in Heinrich’s interpretation.

FM: “Heinrich’s concept of “exchange relation” is completely original with him. No one else puts so much emphasis on this term and defines it the way he does. And it is a new concept in his interpretation; it was not included in his 2012 book Introduction to Marx’s Capital. And unfortunately, he does not explain this very well in this book, especially for such a fundamental concept. There is nothing in his Introduction about this concept; there are only 1½ pages in an appendix in the back of the book on the abstractions that result in this concept (which he doesn’t refer to once in the rest of the book) and 1½ pages in his first discussion of this concept on pp. 53-54. And from then on, he just presumes his interpretation of exchange relation and applies it to different passages in Marx’s text.

I am pretty sure that most readers of Marx (especially beginning readers) will not understand the meaning and significance of Heinrich’s concept of exchange relation in his interpretation. A young Marx scholar from Australia wrote a 2000-word review of Heinrich’s book for Marx and Philosophy and she didn’t mention the concept of exchange relation at all. I myself had to work pretty hard to understand it because it is so poorly presented.

Heinrich defines exchange relation as an exchange between two commodities. To take one of his examples that is borrowed from Marx:

1 quarter of wheat is exchanged for x boot-polish.

Heinrich comments that this definition seems like direct barter exchange between the two commodities, but he states that this is not so, because direct barter seldom actually happens in capitalism. Instead, Heinrich interprets the exchange relation between two commodities as the end result of two actual acts of exchange between the two commodities and money on the market. Thus…

1 qtr. of wheat is sold for 10 shillings and 10 shillings is used to purchase x book-polish

The important point is that Heinrich’s concept of exchange relation between two commodities presupposes actual exchanges between these two commodities and money on the market. Heinrich does not clearly specify whether these acts of exchange that are presupposed in his interpretation of the exchange relation are assumed to be actual acts of exchange on the market. However, they must be actual acts of exchange in order to be consistent with Heinrich’s general value-form interpretation, according to which commodities possess value only if they have been actually exchanged on the market.

Before actual exchange, according the Heinrich’s interpretation, commodities do not possess value (indeed, products are not even commodities) before exchange. Products of labour become commodities and commodities come to possess value only as a result of actual exchanges on the market. Therefore, since the commodities that Marx analyses in Section 1 (e.g. wheat and boot-polish) are assumed to possess value, in order to be consistent with Heinrich’s general value-form interpretation, he must also assume that these commodities have been actually sold and bought on the market. If the commodities have not been actually exchanged on the market, then these commodities would not possess value, according to Heinrich’s general value-form interpretation.

However, there is absolutely no textual evidence in any of Marx’s several drafts of Chapter 1 to support Heinrich’s idiosyncratic interpretation of the exchange relation between two commodities – that it presupposes actual acts of exchange between these two commodities and money on the market. This interpretation is Heinrich’s invention. He does not cite any other authors with a similar interpretation of exchange relation, because there are none. And the exchange relation is the most important concept in Heinrich’s interpretation of Chapter 1. If his fundamental concept of exchange relation is a misinterpretation of Marx’s theory, then the rest of Heinrich’s interpretation of Chapter 1 is a misinterpretation and is unacceptable.

I think it is clear that the subject of analysis of Chapter 1 is the commodity, a representative commodity that is used to analyse the properties that all commodities have in common – use-value and value. Chapter 1 is not about exchange at all. The commodity that is analysed in Chapter 1 has been produced, but not yet exchanged. Exchange is not considered until Chapter 2 (“The Process of Exchange”).

In recent weeks, while preparing for the HM conference and for this interview, I have come to realise more clearly that there is a fundamental contradiction in what Heinrich is trying to accomplish in his recent book. In his previous works, he has presented (many times and all over the world) a strong value-form interpretation of Marx’s theory of value, according to which the value of a commodity exists only as a result of an actual exchange on the market. Before exchange, a commodity does not possess value (it only possesses use-value). For the textual evidence to support this interpretation, he has used a handful of key passages that are taken from various texts in isolation and out of context. As we know, one can always find passages that seem to support almost any interpretation of Marx’s theory. And Heinrich is very good at this quotation game.

However, his most recent book is different; it is an attempt to interpret the first seven chapters of Volume 1, especially Chapter 1, as a value-form theory – and that Marx was the original value-theorist! Heinrich goes from page to page in Chapter 1 and consistently tries to interpret key passages in a value-form way. This is a very difficult task because there are so many passages in these chapters, especially Chapter 1, that contradict a value-form interpretation. Indeed, in my view, Heinrich’s task is an impossible task. My book follows his detailed commentaries point by point and exposes the errors in his value-form interpretation.”

MR: What was the main disagreement between you and Heinrich in your book launch at the recent Historical Materialism conference?

FM: “Not surprisingly, the main disagreement in the session was over the meaning of exchange relation in two paragraphs in Section 1. He argued that I misinterpreted Marx’s concept of exchange relation, not as an act of exchange between two commodities, but as a relation of equality between two commodities, and that I just substituted my meaning of exchange relation for Marx’s meaning in the two passages. And he argued that these two passages are proof that that Section 1 analyses individual commodities as part of an exchange relation.

But that is not true. I did not just substitute my meaning of exchange relation for Marx’s meaning in these paragraphs. Rather, I argued that the exchange relation in these paragraphs is a synonym for exchange-value. The exchange-value of each commodity is defined in the preceding paragraphs in Section 1 as the property of each commodity that is equal to all other commodities in definite proportions that are mutually consistent. That implies that all commodities possess a common property that determines the proportions in which different commodities are equal. Therefore, the exchange relation between two commodities in these paragraphs is also a relation of equality between two commodities, which implies the necessity of a common property possessed by each one of them.

Instead I argued that Heinrich is the one who misinterprets Marx’s concept of exchange relation with his strange definition as the end result of actual exchanges between the two commodities and money on the market,. There is absolutely no textual evidence to support this interpretation of actual market exchanges presupposed in Chapter 1. My interpretation of exchange relation as a relation of equality between commodities is much more reasonable and plausible than Heinrich’s complicated and idiosyncratic interpretation of the end result of actual exchanges between commodities and money on the market. “

MR: Are there other points that you would like to emphasise?

“I also want to mention Heinrich’s unusual interpretation of the word “common” in Marx’s derivation of value in Section 1 – that value is the common property of commodities that determines their exchange-values – because it is an important point in his interpretation that he has emphasised in all his writings, including in the book I am criticising.

Take the concluding paragraph of Marx’s derivation of value on p. 128: “All these things now tell us is that human labour-power is expended to produce them, human labour is accumulated in them. As crystals of this social substance, which is common to them all, they are values – commodity values. ” I argue that Marx’s meaning of “common to them all” in this passage is the usual meaning of “common” , namely that the same property is possessed by each individual commodity by itself, on its own.

Heinrich argues, on the other hand, that the meaning of “common” in this passage and in other passages is ambiguous – i.e. it could also mean a property that each individual commodity possesses, not by itself, but only together with another commodity in an exchange relation (exchange relation again!), and this is what Marx means here and elsewhere when he says that value is a common property of commodities. According to Heinrich, outside of an exchange relation, an individual commodity does not possess the ‘common property’ of value.

However, I don’t think Marx’s meaning of “common to them all” is ambiguous at all; Marx states that the common property of commodities is the human labour accumulated in them as a result of the labour expended to produce them (each one of them), prior to and independent of its exchange with another commodity. Nothing is said about exchange and exchange relation in this key concluding passage.

Three paragraphs before the passage just quoted, Marx presents a geometric example of area as a common property of different geometric figures. Area is a ‘”common property” of each figure, independent of its comparison to the area of another figure. The similarity between the area of geometric figures and the value of commodities is that, in both cases, the objects possess a common property independently of a quantitative comparison between them. Heinrich does not comment on this illuminating geometric example which contradicts his interpretation that the common element of value is created in the exchange itself. Clearly, the area of geometric figures is not created by a comparison of their areas.

One other point I want to mention. In working on this book, I noticed for the first time that Marx repeatedly used the phrase the “own value” of an individual commodity in Section 3 of Chapter 1 (seven times); for example, the “own value” of 10 yards of linen or the “own value” of a coat (see pp. 100 and 104-06 of my book). The own values of the linen and the coat are compared and equated, but nothing is said about exchange. These passages are clear and unambiguous textual evidence that each individual commodity possess its “own value”, independent of acts of exchange between commodities and money on the market. This directly contradicts Heinrich’s interpretation that an individual commodity possesses value only if it has been actually exchanged with money on the market. Heinrich quotes only 3 of these 7 ‘own value’ passages and presents little or no commentary on any of them. Twice he quotes the adjoining sentences, but not these revealing sentences.”

MR: What difference does this debate over the details of Marx’s value theory make in the bigger picture?

FM: “I think it is important to get the details of Marx’s theory of value straight, because it is the foundation for Marx’s theory of surplus-value as a theory of exploitation in Volume 1. And the theory of value is also the foundation of his theory of the falling rate of profit and crises that you have presented so well in your own work. In the Preface to the 1st edition of Capital, Marx stated: “To the superficial observer, the analysis of these forms [the commodity-form of the product of labor and the value-form of the commodity] seems to turn upon minutiae. It does in fact deal with minutiae, but so does microscopic anatomy.” Microscopic anatomy is necessary for the understanding of organic bodies, and similarly Marx’s theory of value is necessary for an understanding of the capitalist economy.

My book is specifically about Heinrich’s book, but it applies to the value-form interpretation of Marx’s theory in general. And my conclusion is that Marx’s theory of value cannot be reasonably be interpreted as a value-form theory. I think that is an important conclusion. We should move on from the value-form interpretation of Marx’s theory.

I worry about Heinrich’s influence on the understanding of Marx’s theory. His interpretation is very influential in Germany and elsewhere in the world, especially among young people. And I am convinced that it is a fundamental misinterpretation of Marx’s theory. So I think it is important to engage with his popular but mistaken interpretation. I hope that my book will be read especially by young people and it will encourage them to make a deeper study of Marx’s theory of value in Chapter 1 of Capital and beyond.

Let me add my pennyworth to what I think are the wider issues arising from this debate between Heinrich and Moseley (MR).

Marx put it this way: “As the commodity is immediate unity of use value and exchange-value, so the process of production, which is the process of the production of a commodity, is the immediate unity of process of labour and process of valorisation.” So, for Marx, it’s the process of production, the exertion of human labour that creates value. As Marx once put it: “Every child knows that any nation that stopped working, not for a year, but let us say, just for a few weeks, would perish. And every child knows, too, that the amounts of products corresponding to the differing amounts of needs demand differing and quantitatively determined amounts of society’s aggregate labour.”

The value-form approach of Heinrich is implicitly a simultaneist approach. Its characteristic feature is the belief that value comes into existence only at the moment of realisation on the market. Consequently, production and realisation are collapsed into each other and time is wiped out. But the process of production and circulation (exchange) is not simultaneous, but temporal. At the start of production there are inputs of raw materials and fixed assets from a previous production period. So there is already (constant or ‘dead labour’) value in the commodity before exchange. Then production takes place to make a new commodity using human labour. This creates ‘potential’ new value, which is realised later (in a modified quantity) when sold.

But why does all this matter? For me, Marx’s value theory is about showing the fundamental contradiction in capitalism between production for social need (use-value) and production for profit (exchange value). Under capitalism, units of production are commodities that have a dual character which epitomises this contradiction.

For Marx, money is a representative of value, not value itself. If we think that value is only created when selling the commodity for money and not before, then the labour theory of value is devalued into a theory of money. Then, as mainstream neoclassical economics argues, we don’t need a labour theory of value at all because the money price will do. Money prices are what mainstream economics looks at, ignoring or dismissing value by human labour power – and therefore the exploitation of labour by capital for profit. It removes the basic contradiction of capitalist production.

Also, it leads to a failure to understand the causes of crises in capitalist production. It is no accident that Heinrich dismisses Marx law of profitability as illogical, ‘indeterminate’ and irrelevant to explaining crises and instead looks to excessive credit and financial instability as the causes. Heinrich even claims that in later years, Marx dropped his law of profitability although the evidence for that is non-existent.

If profits (surplus value) from human labour disappear from any analysis to be replaced by money, then we no longer have a Marxist theory of crisis or any theory of crisis at all.

December 21, 2023

Prices, profits and debt again

Apparently 85% of economists forecast a recession in the US in 2023 – and they were wrong. My own forecast post for 2023 was headed, “the impending slump”. So I must join the bad forecasting majority.

The US economy looks set to finish the year with an increase in real GDP of about 2%, although, as I explained in a previous post, when measured by gross domestic income (GDI), ie adding up the income accrued in profits, rent and wages in real terms, there has been no growth at all.

But if we stick to GDP as the measure of expansion in the US economy, then 2% is a lot more than forecast by the majority at the beginning of 2023. Also, the US official unemployment rate of about 4% and headline inflation of about 3% is way better than most forecasts at the beginning of 2023.

Thus, the cry now is for a ‘soft landing’ or no landing at all. No wonder investment bank economists at Goldman Sachs are having a ‘victory lap’ in having predicted no recession and a ‘return to normal’ for the US economy – while the stock market is having a record ‘Santa’ rally up to Xmas.

But remember this is the US. The situation in the rest of the G7 is pretty much as forecast at the beginning of 2023. The Eurozone is clearly in recession with real GDP flat at best. The same applies to the UK and Sweden, while Canada has suffered a contraction over several quarters. Japan is basically stagnant. Australia and New Zealand are similarly placed.

In a previous report I discussed why the US economy has done better: it’s partly due to significant fiscal stimulus under Biden in 2022; partly due to increased military spending on all America’s proxy wars (now leading to sizeable government deficits and rising public debt); but mostly due to profits in the corporate sector holding up and thus enabling at least a section of the corporate sector to invest. The other large factor has been better consumer spending in the US, as households run down savings built up during the COVID pandemic lockdowns and now through fast-rising consumer debt. None of these spending forces have been visible in the rest of the G7, particularly Europe, hit hard by the loss of cheap Russian energy imports.

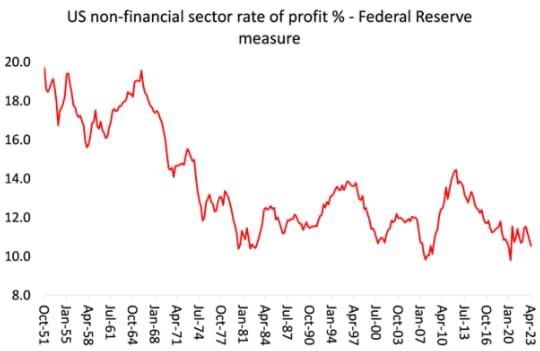

But 2024 may not be so rosy for the US. As I said in a previous post, capitalist economies are, in the last analysis, driven by profits and the profitability of capital.

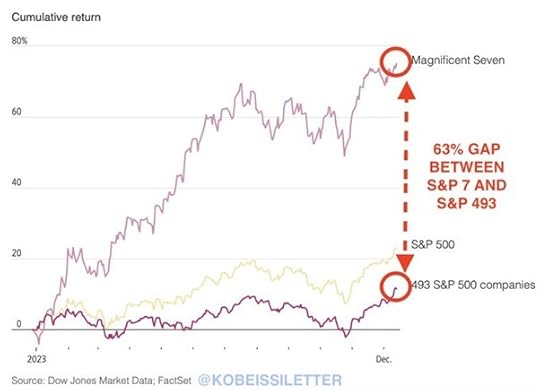

Outside of the ‘magnificent seven’ of mega tech and social media corporations and the energy companies, the rest of the US corporations are experiencing low profitability on their capital.

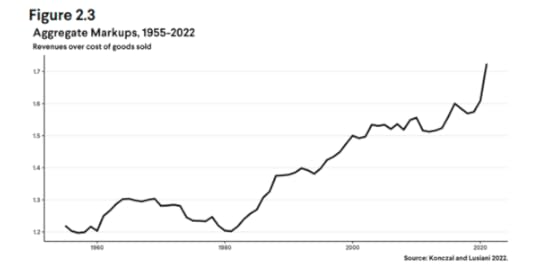

Profit margins rose sharply after the pandemic slump. The supply chains were broken, the production of manufactured goods faltered and international trade fell. So those companies that had some ‘pricing power’ i.e. with not many competitors and interrupted supply sources, were able to hike margins and boost profits.

Inflation rose sharply and the contribution from profit was considerable. But recent research has confirmed that the rise in corporate profit margins “appears mostly driven by a subset of high-markup firms.” In my view, this is different from what some have called ‘greedflation’ – a rather nebulous term. Markups increased for other reasons than firm ‘greediness’, such as firms recouping pandemic losses or because of the uncertainty about future cost increases. So firms that could hike prices were just being capitalist’ i.e. maximising profits.

The now well-known Weber-Wasner thesis on profit-driven inflation was more nuanced. They suggested that supply chain bottlenecks crimped competition by leaving some firms unable to service demand. And that enabled some firms to hike margins and prices. Other studies were even more doubtful about ‘greedflation’ or ‘price gouging’. Bernardino Palazzo of the Federal Reserve board found that American profits as measured in the national accounts were boosted by plunging interest rate costs during the pandemic, as well as government support for businesses. That muddies any other analysis of whether market power mattered.