Michael Roberts's Blog, page 22

May 2, 2023

First Republic – the case for public ownership

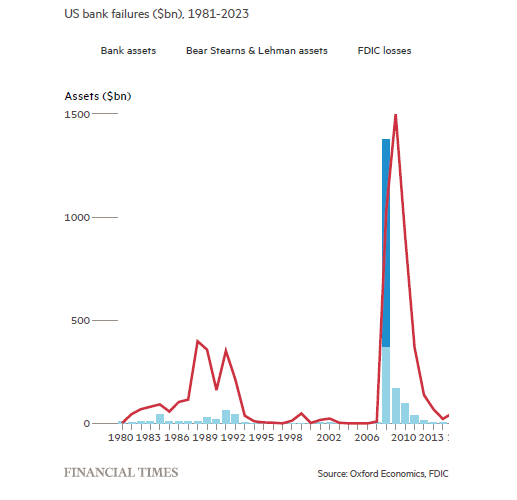

The collapse of First Republic Bank is the latest chapter in the rolling banking crisis in the US. This was the second largest banking collapse in US financial history. It demonstrates yet further the case for public ownership of the banking system.

First Republic is the third bank to fail after the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature. In total, $47bn in bank assets have disappeared into smoke, the losses being taken in part by the shareholders and holders of the bonds in these banks. But there has also been a cost to public funds. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is a public body financed by contributions from all the banks. The cost of arranging and financing the cost of these bankruptcies and takeovers is estimated at $20bn (for SVB), $13bn (for First Republic) and $2.5bn (Signature). So around three-quarters of the total losses are being taken by the FDIC. The FDIC will ask for new levies from the banks, so the burden will eventually be shared, but at the expense of reducing bank lending for households and business and at higher interest costs.

One bank that is not going to lose is JP Morgan. The takeover of First Republic looks like a great deal for JPM. JPM is paying the FDIC $10.6bn, for which it is getting $185bn in interest-bearing loans and securities. In turn, JPM is taking on the deposits of First Republic and First Republic’s outstanding borrowing from the Fed. But the FDIC is providing a $50bn credit line to JPM over five years so that any further fall in deposits or defaults on First Republic loans are covered. In other words, JPM will not have to get expensive borrowing from the Fed as it has a special FDIC loan on easier terms. Small banks may wonder why the largest bank in the US gets a special cheap loan facility.

JPM will now own First Republic assets for $10.6bn. JPM’s chief Dimon says it will make about $500m a year from these assets, which it deserves for taking on the risk of First Republic’s debts. But that is clearly an underestimate – it’s more likely to be a profit of $1bn a year at current loan rates to businesses and especially the low rate that the FDIC has arranged for JPM to borrow. That’s what First Republic earned in its last quarter. So that will add 2% to annual profits from JPM. Moreover, the FDIC has agreed to take 80% of any losses on loan defaults! JPM’s stock price went up by $11bn in one day on the news. So even JPM’s payment to the FDIC has been covered immediately.

These banking collapses offer yet another powerful argument for public ownership of banking. If the three banks had been nationalised, the $35bn being spent by the FDIC to hand over the assets of these banks to larger ones could instead have been used to restructure them into public banks that would have delivered over time sufficient income to make profits for the government (FDIC), not for the likes of JPM.

The other lesson of this crisis is the failure of regulation as the alternative to public ownership. In a special report commissioned by the Fed on the SVB debacle, the blame was laid on the reduction in regulation of smaller banks under the Trump administration. The Democrat administration likes that conclusion, but the report provided no evidence that the Trump changes made any difference to preventing the collapse of any of these banks. The history of regulation, whether applied to large or small banks, has shown to be a total failure.

So now we have had three banking busts, leaving JP Morgan in an even more dominant position in the banking sector, now with 12% of all customer deposits in the US. In the 2008 financial crash, the cry was there were many large banks that were ‘too big to fail’. Fifteen years later and the big banks are even bigger – but not too big to fail as the collapse and takeover of Swiss bank Credit Suisse last month proved. Indeed it is ludicrous that the now huge Swiss UBS bank remains in private ownership, subsidised by the state, instead being publicly owned.

And as long as the Federal Reserve and other central banks keep raising their ‘policy’ interest rates, driving up the cost of borrowing and tightening credit, there remains the increasing danger of further bank collapses down the road.

The case for public ownership is overwhelming, not only of middle-sized banks like First Republic that get into trouble, but also of the big mega banks like JP Morgan, increasingly becoming powerful monopolies. Public ownership, democratically run would end banking as a wasteful, corrupt and unstable money-making machine paying grotesque salries, bonuses and capital gains for a small clique of super-rich speculators (speculating with our deposits) and instead turn it into a public service for its customers, households and businesses, with any profits going to the country as a whole.

April 27, 2023

Inflation: causes and solutions

Last week, the Bank of England’s chief economist, Huw Pill, doubled-down on the argument that the current inflationary spiral affecting the major economies was the result of excessive wage demands. He said that workers should just accept that price rises will hit their living standards. “Somehow in the UK, someone needs to accept that they’re worse off and stop trying to maintain their real spending power by bidding up prices, whether through higher wages or passing energy costs on to customers etc.” Workers asking for more wages just made inflation worse. Pill echoed the previous comments of his boss, the Bank of England governor, Andrew Bailey, who said a year ago that: “I’m not saying nobody gets a pay rise, don’t get me wrong. But what I am saying is, we do need to see restraint in pay bargaining, otherwise it will get out of control”.”

At least this time, Pill vaguely mentioned that firms hiking prices to sustain (or even increase) profitability might also be contributing to inflation. But it remains the orthodox mainstream theory that accelerating inflation is being caused by ‘excessive’ money supply growth over output growth (the monetarist theory) and/or by ‘excessive’ wage demands forcing prices up (the Keynesian theory).

In a similar message, Ben Broadbent, BoE deputy governor, said there was “no getting round the impact on real incomes of . . . jumps in import prices”, which he said had “led to second-round effects on domestic wages and prices”. But how does hiking interest rates stop import price inflation from increased energy and food prices introduced by the multi-nationals that control these necessaries?

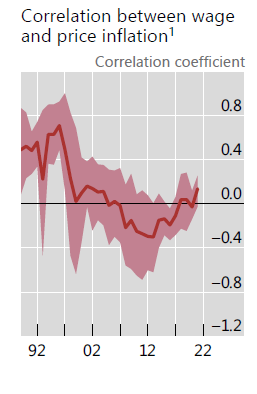

I and others have spent much ink in showing that both these theories do not explain inflation in prices, either now or in the past. And it’s not just leftists. For example, economists at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), hardly a leftist body, found that: “by some measures, the current environment does not look conducive to such a spiral. After all, the correlation between wage growth and inflation has declined over recent decades and is currently near historical lows.”

But central bankers and mainstream economists ignore the evidence and continue to promote monetarist or wage-push inflation theories. Why is this? Gavyn Davies, former chief economist at Goldman Sachs, once explained why the theory that inflation is caused by wage rises persists even though it has been discredited theoretically and empirically. Davies: “without the Phillips Curve, the whole complicated paraphernalia that underpins central bank policy suddenly looks very shaky. For this reason, the Phillips Curve will not be abandoned lightly by policy makers”. (Davies 2017). Another reason not mentioned, of course, is that the monetary authorities and mainstream economics resolutely refuse to recognize the role of profits in capitalist economies. Profits apparently play no role in investment or in firms hiking prices in order to sustain profitability. And above all, profits must be sustained.

Pill reiterated the policy solution of central banks to get inflation rates down: “Interest rate rises in the US and UK over the past year were designed to cool spending power and the ability of companies and people to pass on the pain of inflation to others”. Exactly who was taking on pain, he did not say; but it is clear that the pain is on workers’ real incomes, not on corporate profits (so far).

In a penetrating paper by Matías Vernengo and Esteban Ramon Perez Caldentey, entitled Price and Prejudice: A Note on the Return of Inflation and Ideology, the authors pose the issues at debate: “there is an ideological divide between those that blame inflation in an incompetent government and central bank reaction to the pandemic versus those that suggest that the real culprits are greedy corporations raising their mark up above their costs.” But “this has deviated the debate from the more important question, which is related to the question of whether the inflationary acceleration originated in temporary supply side disruptions caused by the pandemic or resulted from excess demand in an economy close to full employment.”

The authors go on to say that the dominant view in the profession, and among policy makers is that inflation is caused by excess demand. The main argument against this view is that corporations have taken advantage of supply-side problems during the pandemic to obtain unjustifiable extra gains in an already unequal society.

It’s true that over the past forty years of neoliberal ascendancy, deregulation has allowed corporations to amass pricing power. And it is also the case that that profit margins have increased during the recent inflationary acceleration. And the financial sector has made significant profits during and after the pandemic. But Vernengo and Ramon counter that “it would be wrong to claim as some do on the left that current inflation is ‘greedflation’ ie caused by price-gouging; or that it is the result of monopolistic pricing.”

The empirical evidence shows that it was the sharp rise in the prices of non-labor inputs that were “the likely culprits for the acceleration in inflation”. They rose because of the shutdown of key suppliers during COVID in China and other developing countries and from the loss of electronic components supply that went into the production of consumers goods and because the supply chain system was broken with the collapse of the just in time inventory methods over the last four decades.

Sure, prices in oligopolistic markets are likely to be higher than in more competitive markets “but it is not the case that this can explain the continuous rise in prices; that would require a change in the competitive conditions, something that is not clearly taken place in the last two years.” Higher inflation can occur both with fairly competitive or oligopolistic market structures. In the late 19th century, the so-called Gilded Age Era was characterized by the rise of cartels, but with deflation in prices; and the 1990s, often seen as a second Gilded Age with increasing market concentration, experienced a so-called Great Moderation in price inflation ie disinflation. Indeed, in the last big inflationary spiral of the 1970s, profits actually fell. According to Sylos-Labini, wiring then: “the decline of the share of profits in several capitalist countries can be attributed primarily to the persistent increase of direct costs in labor, raw materials, and energy”. This contradicts views according to which: “Companies with enough market power can also unilaterally raise prices in a quest for greater and greater profits” as MMT economist, Stephanie Kelton has argued.

In a recently widely acclaimed paper, Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner, Sellers’ inflation, profits and conflict: why can large firms hike prices in an emergency? argue that “To link market power to the sudden increases in profits, it is necessary to examine why large firms have raised prices in the context of the pandemic but kept prices stable in the preceding decades. This implies that market power is not constant but can change dynamically in a changing supply environment.” They point out that that, before the pandemic, there was a long period of relative macroeconomic price stability, with low inflation and generally shared growth in nominal value added between wages and profits.

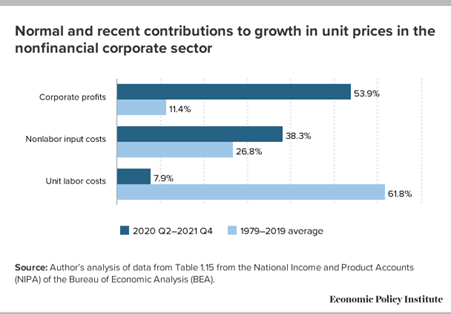

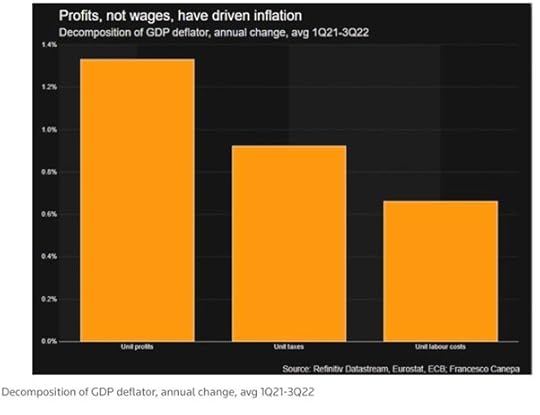

It was only in the post-pandemic period of the last two years that profits have usurped a greater share of the value in price increases per unit of output. But as their table shows, in the first part of 2020, it was wages that gained most from price rises as profits dived in the pandemic slump. Through 2021 those relative shares were gradually reversed and profits reaped the lion’s share. But in 2022, the wage-profit share in the value of price rises was pretty even. Indeed, in Q3 2022, labor’s share in price rises was greater.

So it all depends on the point in the cycle of expansion and contraction that a capitalist economy is undergoing, not on the ability of monopolies to ‘price gouge’ as such. The data suggest that, in the period of supply chain blockages and sharply rising basic commodity prices (food, energy), firms with pricing power hiked prices to sustain and even increase profits (2020-21). But as supply blockages subsided and production picked up in 2021-22, competition increased and further profit mark-ups could not be sustained.

As Vernengo and Ramon conclude: “The persistence of contractionary demand, mostly monetary, policy as the main tool to contain inflation seems to respond more to the prevailing prejudices and the ideological biases of the profession, than to the analysis of the real causes of inflation.” On the other hand,“It is not helpful that the main challenge to this consensus has been to blame corporations for increasing their profit margins, since this view also provides an incorrect explanation for the recent acceleration of inflation. The main culprit for the inflationary acceleration in the U.S. and most advanced economies is related to the supply side snags, and the shock to energy and food prices resulting from the pandemic and the war in the Ukraine.”

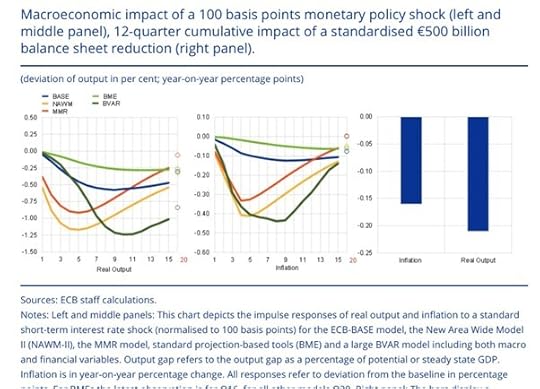

Central bankers and the mainstream ignore all this debate and continue with their claims that it is excessive money, or excessive aggregate demand and wage rises that is causing the inflationary spiral. Their policy answer is to raise interest rates and reduce money supply to restrict demand and, as unemployment rises, weaken wage bargaining power.

What should be the policy against accelerating inflation? Weber and other leftists have argued for the introduction of price controls as the alternative to central bank policies. I have argued against price controls as an effective policy to control generalized inflation, especially as current inflation,is being driven by international energy and food prices. Controlling energy prices at the domestic consumer end would not solve price rises at the producer end, but simply drive private energy supplies into bankruptcy. That would force governments to reverse controls or take over companies. Indeed, that poses the best policy answer: public ownership of the international energy and food companies that operate throughout the global supply chain.

In the meantime, price controls or not, the reality is that, as economies go into 2023, headline inflation rates are falling, as energy and food prices fall back. And so are profit margins as the major economies slip into a slump.

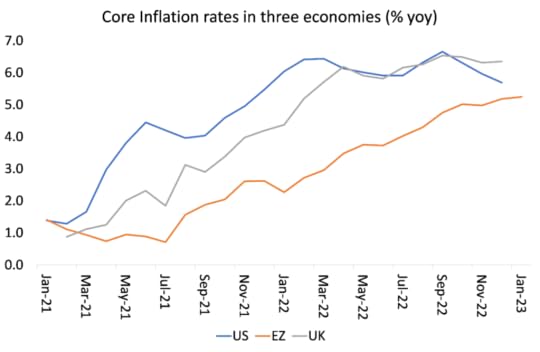

Sure, so-called ‘core inflation’ (excluding food and energy) remains ‘sticky’, so that even in a slump, inflation rates are likely to stay above the average rates prior to the pandemic slump. But it’s the slump that will end high inflation (as it did in the early 1980s), not interest-rate hikes or price controls.

April 22, 2023

A multipolar world and the dollar

Christine Lagarde, the head of the European Central bank (ECB), made an important ‘keynote’ speech last week to the US Council of Foreign Relations in New York.

It was important because she analysed recent developments in global trade and investment and assessed the implications of the apparent move away from the hegemonic dominance of the US economy and the dollar in the world economy and the move towards a ‘fragmented’, ‘multipolar’ world economy – where no one economic power or even the current imperialist bloc of the G7-plus will dominate global trade, investment and currencies.

Lagarde explained: “The global economy has been undergoing a period of transformative change. Following the pandemic, Russia’s unjustified war against Ukraine, the weaponisation of energy, the sudden acceleration of inflation, as well as a growing rivalry between the United States and China, the tectonic plates of geopolitics are shifting faster.”

You may not agree with the causes that Lagarde offers, but she concluded that “We are witnessing a fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, with each bloc trying to pull as much of the rest of the world closer to its respective strategic interests and shared values. And this fragmentation may well coalesce around two blocs led respectively by the two largest economies in the world.”

So it’s fragmentation and a coalescence into a battle between a US-led bloc and a China-led bloc. This is the worry for Lagarde and the US-led imperialist bloc – a loss of global control and a fragmentation of global economic power not seen since the inter-war period of the 1920s and 1930s.

Lagarde talked nostalgically of the post-1990 period after the collapse of the Soviet Union, supposedly heralding a period of global dominance by the US and its ‘alliance of the willing’. “In the time after the Cold War, the world benefited from a remarkably favourable geopolitical environment. Under the hegemonic leadership of the United States, rules-based international institutions flourished and global trade expanded. This led to a deepening of global value chains and, as China joined the world economy, a massive increase in the global labour supply.”

Yes, these were the days of the globalization wave of rising trade and capital flows; the domination of Bretton Woods institutions like the IMF and the World Bank dictating the terms of credit; and above all, the expectation that China would be brought under the imperialist bloc after it joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001.

However, it did not work out as expected. The globalization wave came to an abrupt end after the Great Recession and China did not play ball in opening up its economy to the West’s multi-nationals. That forced the US to switch its policy on China from ‘engagement’ to ‘containment’ – and with increasing intensity in the last few years. And then came the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the renewed determination of the US and its European satellites to expand its control eastwards and so ensure that Russia fails in its attempt to exert control over its border countries and permanently weaken Russia as an opposition force to the imperialist bloc.

Lagarde comments on the economic implications of this: “But that period of relative stability may now be giving way to one of lasting instability resulting in lower growth, higher costs and more uncertain trade partnerships. Instead of more elastic global supply, we could face the risk of repeated supply shocks.” In other words, globalization and the easy movement of supply, trade and capital flows that benefited the imperialist bloc so much (see our paper The economics of modern imperialism) had come to an end.

The response has been an intensification of protectionist measures (rising tariffs etc); control of trade, particularly in technology and attempts to reverse globalization into ‘reshoring’ or ‘friendshoring’ capital that previously went to all parts of the globe.

As Lagarde put it: “governments are legislating to increase supply security, notably through the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States and the strategic autonomy agenda in Europe. But that could, in turn, accelerate fragmentation as firms also adjust in anticipation. Indeed, in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the share of global firms planning to regionalise their supply chain almost doubled – to around 45% – compared with a year earlier.”

Do these developments mean that the imperialist bloc is losing control of the extraction of surplus value from the working people of the world? In particular, is the US dollar’s role as the emperor of currencies under threat from other currencies in trade and investment? Lagarde commented: “Anecdotal evidence, including official statements, suggests that some countries intend to increase their use of alternatives to major traditional currencies for invoicing international trade, such as the Chinese renminbi or the Indian rupee. We are also seeing increased accumulation of gold as an alternative reserve asset, possibly driven by countries with closer geopolitical ties to China and Russia.”

It’s undoubtedly true that the imposition of economic sanctions on Russia employed by the imperialist governments – banning of energy imports; seizing FX reserves; closing international banking settlement systems – has accelerated the move away from holding the dollar and euro. However, Lagarde added the caveat that this trend is still way short of dramatically changing the global financial order. “These developments do not point to any imminent loss of dominance for the US dollar or the euro. So far, the data do not show substantial changes in the use of international currencies. But they do suggest that international currency status should no longer be taken for granted.”

Lagarde is right. As I have shown in previous posts, that although the US and the EU have lost ground in the share of world production, trade and even currency transactions and reserves, there is still a long way to go before declaring a ‘fragmented’ world economy in that sense.

The US dollar (and to a lesser extent the euro) remains dominant in international payments. The US dollar is not being gradually replaced by the euro, or the yen, or even the Chinese renminbi, but by a batch of minor currencies.

According to the IMF, the share of reserves held in US dollars by central banks has dropped by 12 percentage points since the turn of the century, from 71 percent in 1999 to 59 percent in 2021. But this fall has been matched by a rise in the share of what the IMF calls ‘non-traditional reserve currencies’, defined as currencies other than the ‘big four’ of the US dollar, euro, Japanese yen and British pound sterling, namely such as the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, Chinese renminbi, Korean won, Singapore dollar, and Swedish krona. All this suggests is that the shift in international currency strength after the Ukraine war will not be into some West-East bloc, as most argue, but instead towards a fragmentation of currency reserves.

This fragmentation worries Lagarde, as a key representative of the US-EU global hegemony. She proposed: “insofar as geopolitics leads to a fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, this calls for greater policy cohesion. Not compromising independence, but recognizing interdependence between policies, and how each can best achieve their objective if aligned behind a strategic goal.” What does she mean? She means that the major powers must work together with similar fiscal and monetary measures to ensure that ‘fragmentation’ fails and the existing order is sustained. But that is going to be very difficult in a world economy that is slowing in real GDP and investment growth, and above all, where the profitability of capital remains around all-time lows.

The US dollar and its hegemony is not under threat yet because “50-60% of foreign-held US short-term assets are in the hands of governments with strong ties to the United States – meaning they are unlikely to be divested for geopolitical reasons.” (Lagarde). And it’s even the case that ‘anti-US’ China remains heavily committed in its FX reserves to the US dollar. China publicly reported that it reduced the dollar share of its reserves from 79% to 58% between 2005 and 2014. But China doesn’t appear to have changed the dollar share of its reserves in the last ten years.

Moreover, multilateral institutions that could be an alternative to the existing IMF and World Bank (controlled by the imperialist economies) are still tiny and weak. For example, there is the New Development Bank set up in 2015 by the so-called BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). The NDB has now appointed Brazil’s former leftist President Dilma Roussef as head, based in Shanghai.

There is much noise that the NDB can provide an opposite pole of credit to the imperialist institutions of the IMF and World Bank. But there is a long way to go in doing that. One ex-official of South African Reserve bank (SARB) commented: “the idea that Brics initiatives, of which the most prominent thus far has been the NDB, will supplant Western-dominated multilateral financial institutions is a pipe dream.” For a start, the BRICS are very diverse in population, GDP per head, geographically and in trade composition. And the ruling elites in these countries are often at loggerheads (China v India; Brazil v Russia).

As Patrick Bond put it recently: “The “talk left, walk right” of BRICS’ role in global finance is seen not only in its vigorous financial support for the International Monetary Fund during the 2010s, but more recently in the decision by the BRICS New Development Bank – supposedly an alternative to the World Bank – to declare a freeze on its Russian portfolio in early March, since otherwise it would not have retained its Western credit rating of AA+. ” And Russia is a 20% equity holder in NDB.

But back to Lagarde: “the single most important factor influencing international currency usage is the “strength of fundamentals.” In other words, on the one hand, the trend of weakening economies in the imperialist bloc facing very slow growth and slumps during the rest of his decade; and on the other, continued expansion of China and even India. This means that the heavy military and financial dominance of the US and its allies stands on the chicken legs of relatively poor productivity, investment and profitability. That’s a recipe for global fragmentation and conflict.

April 14, 2023

Well founded pessimism

Only last February, I posted that there had been a burst of optimism about the state of the world economy in 2023. The consensus view then was that the G7 economies (with the sorry exception of the UK) would avoid a slump this year. Sure, there will be a slowdown compared to 2022, but the major economies were going to achieve a ‘soft landing’ or even no landing at all, but just motor on, if at a low rate of growth. The international agencies like the World Bank, the OECD and the IMF upgraded their forecasts for global growth.

However, all that optimism has proven “unfounded” as I suggested then. Even in the best performing G7 economy, the US, a recession (ie ‘technically’ two consecutive quarters of contraction in real GDP) now seems probable. Even the US Federal Reserve accepts that a recession is unavoidable. At its last meeting, its economists agreed that there would be a ‘mild recession’ in US economic activity this year.

And according to economists at the Bank of America, there are plenty of signals that suggest a recession in the US has not been avoided and they provide several charts to back that up. First, there was the significant decline in manufacturing activity. “March ISM was 46.3, lowest since May 2020. In past 70 years whenever manufacturing ISM dropped below 45, recession occurred on 11 out of 12 occasions (exception was 1967),” BofA said. Indeed, globally there appears to be a manufacturing recession.

Second, the current ‘buoyant’ jobs market won’t last because it often follows manufacturing activity downwards – it’s a lagging indicator.

“Weak ISM manufacturing PMI suggests US labor market will weaken next few months,” BofA said, adding that it viewed the February and March jobs report as “the last strong payroll reports of 2023.”

Then there is the inverted bond yield curve that always presages a recession.

Also, global house prices are falling, creating a slump in construction and real estate development.

Another reliable indicator is the Leading Economic Index (LEI) published by the Conference Board. The LEI for the US fell for the 11th straight month in February, which is the longest slump since the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. “While the rate of month-over-month declines in the LEI have moderated in recent months, the leading economic index still points to risk of recession in the US economy,” said Justyna Zabinska-La Monica, senior manager at the Conference Board.

These are some indicators of a forthcoming recession, but they are not the causes. I have argued that there are two principal drivers of a slump: falling profits and profitability; and rising interest costs. These are the two closing scissors that cut off the accumulation of capital and force companies to stop investing, reduce employment and, among the weaker brethren, go bust.

The BoA economists also recognise these factors. They note that a decline in manufacturing often coincides with lower earnings.

And their global earnings model also suggests imminent decline in corporate earnings.

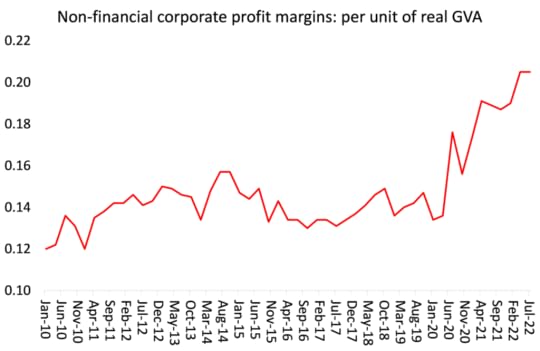

Much has been made on the left about the huge rise in corporate profit margins after the end of the pandemic. And this is undoubtedly the main contributor to the inflationary spiral experienced in all the major economies in the last 18 months – not any wage-cost push as the Keynesians argue; or too much money supply as the monetarists argue. A January study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City found that “markup growth”—the increase in the ratio between the price a firm charges and its cost of production—was a far more important factor in driving inflation in 2021 than it had been throughout economic history.

University of Massachusetts Amherst economists Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner published a paper that has been widely taken up entitled, “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why Can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?”. It found that corporations engaged in “price gouging” during the pandemic. The authors went on to argue that price controls may be the only way to prevent the “inflationary spirals” that could come as a result of this gouging.

Albert Edwards, a global strategist at the 159-year-old bank Société Générale, has now followed up on this thesis that has come to be called ‘Greedflation’. Corporations, particularly in developed economies like the US and UK, have used rising raw material costs amid the pandemic and the war in Ukraine as an “excuse” to raise prices and expand profit margins to new heights, Edwards said.

There is no doubt that corporate margins have been at record highs. Both in the US and in Europe. But I have thrown some doubt on the explanation that current high inflation has been caused mainly by ‘price-gouging’ from monopolistic corporations.

And the Kansas Fed paper cited above agrees. The authors reckon that “although our estimate suggests that markup growth was a major contributor to annual inflation in 2021, it does not tell us why markups grew so rapidly. We present evidence that the timing and cross-industry patterns of markup growth are more consistent with firms raising prices in anticipation of future cost increases, rather than an increase in monopoly power or higher demand. First, the timing of markup growth in 2021, as well as earlier in the pandemic, does not line up neatly with the spike in inflation during the second half of 2021. Instead, the largest growth in markups occurred in 2020 and the first quarter of 2021; in the second half of 2021, markups actually declined. Therefore, inflation cannot be explained by a persistent increase in market power after the pandemic. Second, if monopolists raising prices in the face of higher demand were driving markup growth, we would expect firms with larger increases in current demand to have accordingly larger markups. Instead, markup growth was similar across industries that experienced very different levels of demand (and inflation) in 2021.“

The authors cast doubt on the simple explanation of “greedflation,” understood as either an increase in monopoly power or firms using existing power to take advantage of high demand. So the post-Keynesian mark-up theory of inflation and the policy conclusion of price controls looks faulty.

I wrote a post last September that, anyway, profit margins were beginning to fall. The average profit margin for the top 500 US companies 2022 is estimated at 12.0%, down from 12.6% in 2021, if still well above the ten-year average margin of 10.3%. And as overall economic growth in the US slows – corporate sales revenue growth is slowing too.

Indeed, I found that the final data on US pre-tax corporate profits in Q4 2022, show a 5-6% fall in each of the last two quarters of 2022, or a 12% fall from the peak in mid-2022. Profits fell year-on-year for the first time since the pandemic slump. The post-pandemic corporate profits boom is over.

The slowdown in US corporate profits is replicated in all the major economies. Here is my latest estimate of global corporate profits based on five key economies. The pandemic slump recorded a 20% fall in global corporate profits in 2020, followed by a 50% recovery in 2021, but now profits growth has slowed to just 0.5% in Q4 2022. And note, as I have done before, that profits had stopped rising through 2019 even before the pandemic, suggesting that the major economies were heading for a slump before COVID emerged.

Then there is the credit squeeze from rising interest rates and monetary tightening (ie a fall in money supply growth). This is happening because the major central banks are still determined to try and ‘control inflation’ with high interest rates (even though this has been shown to misunderstand the causes of current inflation).

In its minutes, the Fed put it this way: “With inflation remaining unacceptably high, participants expected that a period of below-trend growth in real GDP would be needed to bring aggregate demand into better balance with aggregate supply and thereby reduce inflationary pressures.” So even a recession will be needed to bring inflation down. In that, the Fed is right – indeed inflation rates will stay well above pre-pandemic elevls unless there is a slump.

After the pandemic, central banks tried to return to the easy money policy adopted during the long depression of the 2010s in order to boost economic recovery. A tremendous credit boom took place in 2022, which led to a surge in US bank lending of $1.5trn.

Alongside bank loans there was an explosion in what is called low-quality lending that brought debt loads in corporate America to record highs. The total US stock of “subprime” corporate debt (junk bonds, leveraged loans, direct lending) has reached $5tn. Total non-financial corporate debt (bonds and loans) stands at $12.7tn, making low-quality debt as much 40% of the total.

This debt financed very speculative or highly indebted companies either in the form of a loan (“leveraged loans”) or non-investment grade bonds (“junk bonds”) and includes corporate loans sold into securitizations called Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) as well as loans extended privately by non-banks that are completely unregulated. Years of growth, evolution, and financial engineering have spawned a complex, highly fragmented, and under-regulated bond market.

And this was replicated globally. The annual report from the Global Financial Stability Board on the so-called Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFI) found that the “NBFI sector grew by 8.9% in 2021, higher than its five-year average growth of 6.6%, reaching $239.3 trillion. […] The total NBFI sector increased its relative share of total global financial assets from 48.6% to 49.2% in 2021.”

Central banks have no idea of what is causing inflation and how to control it, but they go on hiking rates even if it causes bank failures, corporate bankruptcies and a slump. Fed governor Kocherlakota noted that “central bankers have expressed concerns that above-target inflation could lead “inflation to become unmoored” (Bernanke 2011) or “inflation to become entrenched” (Powell 2022).” That could give rise to the follow-up need to bring down “inflation expectations” through a severe recession. As Bernanke (2011) saids, “the cost of that in terms of employment loss in the future, as we had to respond to that, would be quite significant… To the best of my knowledge, there are no macroeconomic models in the academic world that integrate possibilities of this kind. “ So not a clue.

The recent US banking crisis was a result of the growing credit squeeze on banks, mainly smaller ones, and on companies. And it is not over – either in the US or Europe. As interest rates rise, depositors are switching their money from weak banks into better yielding accounts such as money market funds, fleeing those banks that put their customer deposits into loss-making assets like government bonds. This has led to a sharp decline in bank lending to companies across the US.

and in Europe.

So there are less funds for investment and survival and at higher interest rates. Up to now, because corporate profits had risen so much, even though corporate debt to GDP had risen to all-time highs, most US firms have been able to cover the debt servicing costs comfortably. But that is over. The infamous zombie companies (up to 20% of all firms in the US and Europe) are facing bankruptcy.

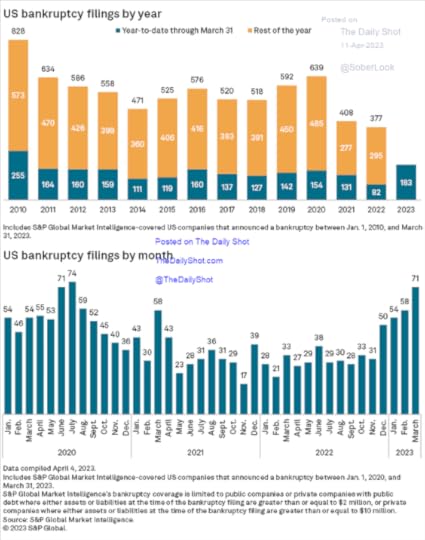

Bankruptcy filings have spiked across major industries. In March, 42,368 new bankruptcies were filed, up 17% from a year back. It was also the third straight month of bankruptcy increases. Meanwhile, venture capital funding for start-ups declined by 55% in the first quarter of 2023 compared to the same period a year ago. This is the lowest level in over five years.

And here is how John Plender of the FT put it: “the most draconian tightening in four decades in the advanced economies with the notable exception of Japan, will wipe out much of the zombie population, thereby restricting supply and adding to inflationary impetus. Note that the total number of company insolvencies registered in the UK in 2022 was the highest since 2009 and 57 per cent higher than 2021.”

In its latest economic report, the IMF says the world economy is experiencing “a rocky recovery”. It forecasts that global growth (which remember, includes China, India and other large ‘developing’ economies) will slow this year to 2.8%. And that’s the base forecast. If credit tightens further and interest rates stay high, global growth could drop to just 1%. The G7 economies will grow little more than 1% this year and, after accounting for population growth, hardly at all. The UK and Germany will contract.

UNCTAD follows the IMF with an even more pessimistic forecast for global growth this year – just 2.1%. It concludes that “This could set the world onto a recessionary track…. With the era of cheap credit coming to an end at a time of “polycrisis” and growing geopolitical tensions, the risk of systemic calamities cannot be ruled out. The damage to developing countries from unforeseen shocks, particularly where indebtedness is already a source of distress, will be heavy and lasting.”

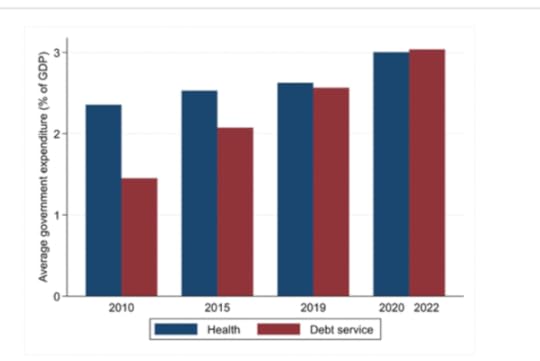

UNCTAD points out that debt servicing costs have consistently increased relative to public expenditure on essential services. The number of countries spending more on external public debt service than healthcare increased from 34 to 62 during this period.

Vítor Gaspar, head of fiscal policy at the IMF, said that by 2028, the world’s public debt burden was on course to match the value of goods and services produced in the world. “By the end of our projection horizon — 2028, public debt in the world is expected to reach almost 100 per cent of GDP back to the record levels set in the year of the pandemic”.

His answer was a new bout of ‘austerity’ (ie cutting public spending and raising taxes). “Fiscal tightening can help by moderating the growth of aggregate demand and therefore contributing to more moderate increases in policy rates,” he said, adding that this in turn would “ease the pressures on the financial system” triggered by the surge in borrowing costs over the course of 2022.

According to Fitch Rating, national debt defaults are at a record high. There have been 14 separate default events since 2020, across nine different sovereigns, a marked increase compared with 19 defaults across 13 different countries between 2000 and 2019.

The long depression of the 2010s is continuing into the 2020s. The World Bank’s latest economic report makes dismal reading for the world economy. “The global economy’s “speed limit”—the maximum long-term rate at which it can grow without sparking inflation—is set to slump to a three-decade low by 2030.” Between 2022 and 2030 average global potential GDP growth is expected to decline by roughly a third from the rate that prevailed in the first decade of this century—to 2.2% a year. For developing economies, the decline will be equally steep: from 6% a year between 2000 and 2010 to 4% a year over the remainder of this decade. These declines would be much steeper in the event of a global financial crisis or a recession.

“A lost decade could be in the making for the global economy,” said Indermit Gill, the World Bank’s Chief Economist. Unless, of course, Generalised Artificial Intelligence with ChatGPT saves the day for capitalism.

April 8, 2023

AI-GPT: a game changer?

ChatGPT is being heralded as a revolution in ‘artificial intelligence’ (AI) and has been taking the media and tech world by storm since launching in late 2022.

According to OpenAI, ChatGPT is “an artificial intelligence trained to assist with a variety of tasks.” More specifically, it is a large language model (LLM) designed to produce human-like text and converse with people, hence the “Chat” in ChatGPT.

GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer. The GPT models are pre-trained by human developers and then are left to learn for themselves and generate ever increasing amounts of knowledge, delivering that knowledge in an acceptable way to humans (chat).

Practically, this means you present the model with a query or request by entering it into a text box. The AI then processes this request and responds based on the information that it has available. It can do many tasks, from holding a conversation to writing an entire exam paper; from making a brand logo to composing music and more. So much more than a simple Google-type search engine or Wikipedia, it is claimed.

Human developers are working to raise the ‘intelligence’ of GPTs. The current version of GPT is 3.5 with 4.0 coming out by the end of this year. And it is rumoured that ChatGPT-5 could achieve ‘artificial general intelligence’ (AGI). This means it could pass the Turing test, which is a test that determines if a computer can communicate in a manner that is indistinguishable from a human.

Will LLMs be a game changer for capitalism in this decade? Will these self-learning machines be able to increase the productivity of labour at an unprecedented rate and so take the major economies out of their current ‘long depression’ of low real GDP, investment and income growth; and then enable the world to take new strides out of poverty? This is the claim by some of the ‘techno-optimists’ that occupy the media.

Let’s consider the answers to those questions.

First, just how good and accurate are the current versions of ChatGPT? Well, not very, just yet. There are plenty of “facts” about the world which humans disagree on. Regular search lets you compare those versions and consider their sources. A language model might instead attempt to calculate some kind of average of every opinion it’s been trained on—which is sometimes what you want, but often is not. ChatGPT sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers. Let me give you some examples.

I asked ChatGPT 3.5: who is Michael Roberts, Marxist economist? This was the reply.

This is mostly right but it is also wrong in parts (I won’t say which).

Then I asked it to review my book, The Long Depression. This is what it said:

This gives a very ‘general’ review or synopsis of my book, but leaves out the kernel of the book’s thesis: the role of profitability in crises under capitalism. Why, I don’t know.

So I asked this question about Marx’s law of profitability:

Again, this is broadly right – but just broadly. The answer does not really take you very far in understanding the law. Indeed, it is no better than Wikipedia. Of course, you can dig (prompt) further to get more detailed answers. But there seems to be some way to go in replacing human research and analysis.

Then there is the question of the productivity of labour and jobs. Goldman Sachs economists reckon that if the technology lived up to its promise, it would bring “significant disruption” to the labour market, exposing the equivalent of 300m full-time workers across the major economies to automation of their jobs. Lawyers and administrative staff would be among those at greatest risk of becoming redundant (and probably economists). They calculate that roughly two-thirds of jobs in the US and Europe are exposed to some degree of AI automation, based on data on the tasks typically performed in thousands of occupations.

Most people would see less than half of their workload automated and would probably continue in their jobs, with some of their time freed up for more productive activities. In the US, this would apply to 63% of the workforce, they calculated. A further 30% working in physical or outdoor jobs would be unaffected, although their work might be susceptible to other forms of automation.

The GS economists concluded: “Our findings reveal that around 80% of the US workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of workers may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted.”

With access to an LLM, about 15% of all worker tasks in the US could be completed significantly faster at the same level of quality. When incorporating software and tooling built on top of LLMs, this share increases to 47-56% of all tasks. About 7% of US workers are in jobs where at least half of their tasks could be done by generative AI and are vulnerable to replacement. At a global level, since manual jobs are a bigger share of employment in the developing world, GS estimates about a fifth of work could be done by AI — or about 300m full-time jobs across big economies.

These job loss forecasts are nothing new. In previous posts, I have outlined several forecasts on the number of jobs that will be lost to robots and AI over the next decade or more. It appears to be huge; and not just in manual work in factories but also in so-called white-collar work.

It is in the essence of capitalist accumulation that the workers will continually face the loss of their work from capitalist investment in machines. The replacement of human labour by machines started at the beginning of the British Industrial Revolution in the textile industry, and automation played a major role in American industrialization during the 19th century. The rapid mechanization of agriculture starting in the middle of the 19th century is another example of automation.

As Engels explained, whereas mechanisation not only shed jobs, often it also created new jobs in new sectors, as Engels noted in his book, The condition of the working class in England (1844) – see my book on Engels’ economics pp54-57. But as Marx identified this in the 1850s: “The real facts, which are travestied by the optimism of the economists, are these: the workers, when driven out of the workshop by the machinery, are thrown onto the labour-market. Their presence in the labour-market increases the number of labour-powers which are at the disposal of capitalist exploitation…the effect of machinery, which has been represented as a compensation for the working class, is, on the contrary, a most frightful scourge. …. As soon as machinery has set free a part of the workers employed in a given branch of industry, the reserve men are also diverted into new channels of employment and become absorbed in other branches; meanwhile the original victims, during the period of transition, for the most part starve and perish.” Grundrisse. The implication here is that automation means increased precarious jobs and rising inequality.

Up to now, mechanisation has still required human labour to start and maintain it. But are we now moving towards the takeover of all tasks, and especially those requiring complexity and ideas with LLMs? And will this mean a dramatic rise in the productivity of labour so that capitalism will have a new lease of life?

If LLMs can replace human labour and thus raise the rate of surplus value dramatically, but without a sharp rise in investment costs of physical machinery (what Marx called a rising organic composition of capital), then perhaps the average profitability of capital will jump back from its current lows.

Goldman Sachs claims that these “generative” AI systems such as ChatGPT could spark a productivity boom that would eventually raise annual global GDP by 7% over a decade. If corporate investment in AI continued to grow at a similar pace to software investment in the 1990s, US AI investment alone could approach 1% of US GDP by 2030.

I won’t go into how GS calculates these outcomes, because the results are conjectures. But even if we accept the results, are they such an exponential leap? According to the latest forecasts by the World Bank, global growth is set to decline by roughly a third from the rate that prevailed in the first decade of this century—to just 2.2% a year. And the IMF puts the average growth rate at 3% a year for the rest of this decade.

If we add in the GS forecast of the impact of LLMs, we get about 3.0-3.5% a year for global real GDP growth, maybe – and this does not account for population growth. In other words, the likely impact would be no better than the average seen since the 1990s. That reminds us of what Economist Robert Solow famously said in 1987 that the “computer age was everywhere except for the productivity statistics.”

US economist Daren Acemoglu adds that not all automation technologies actually raise the productivity of labour. That’s because companies mainly introduce automation in areas that may boost profitability, like marketing, accounting or fossil fuel technology, but not raise productivity for the economy as a whole or meet social needs. Big Tech has a particular approach to business and technology that is centered on the use of algorithms for replacing humans. It is no coincidence that companies such as Google are employing less than one tenth of the number of workers that large businesses, such as General Motors, used to do in the past. This is a consequence of Big Tech’s business model, which is based not on creating jobs but automating them.

That’s the business model for AI under capitalism. But under cooperative commonly owned automated means of production, there are many applications of AI that instead could augment human capabilities and create new tasks in education, health care, and even in manufacturing. Acemoglu suggested that “rather than using AI for automated grading, homework help, and increasingly for substitution of algorithms for teachers, we can invest in using AI for developing more individualized, student-centric teaching methods that are calibrated to the specific strengths and weaknesses of different groups of pupils. Such technologies would lead to the employment of more teachers, as well as increasing the demand for new teacher skills — thus exactly going in the direction of creating new jobs centered on new tasks.” And rather than reduce jobs and the livelihoods of humans, AI under common ownership and planning could reduce the hours of human labour for all.

And then there is the issue of the profitability boost provided by AI technology. Even if LLM investment requires less physical means of production and lowers costs of such capital, the loss of human labour power could be even greater. So Marx’s law of profitability would still apply. It’s the great contradiction of capitalism that increasing the productivity of labour through more machines (AI) reduces the profitability of capital. That leads to regular and recurring crises of production, investment and employment – of increasing intensity and duration.

Finally, there is the question of intelligence. Microsoft argues that intelligence is a “very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience.” Microsoft hints that LLMs could soon obtain this ‘generalised intelligence’ and surpass all human ability to think.

But even here, there is scepticism. “The ChatGPT model is huge, but it’s not huge enough to retain every exact fact it’s encountered in its training set. It can produce a convincing answer to anything, but that doesn’t mean it’s reflecting actual facts in its answers. You always have to stay sceptical and fact check what it tells you. Language models are also famous for “hallucinating”—for inventing new facts that fit the sentence structure despite having no basis in the underlying data.” That’s not very encouraging.

But Guglielmo Carchedi has a more fundamental reason to deny that AI can replace human ‘intelligence’. Carchedi and Roberts: “machines behave according only to the rules of formal logic. Contrary to humans, machines are structurally unable to behave according to the rules of dialectical thinking. Only humans do that.” (Capitalism in the 21st century, p167). Here is the ChatGPT answer to the dialectical question: “Can A be equal to A and at the same time be different from A?” “No, it is not possible for A to be equal to A and at the same time be different from A. This would be a contradiction in terms, as the statement “A is equal to A” is a tautology and always true, while the statement “A is different from A” is a contradiction and always false. Therefore, these two statements cannot both be true at the same time.”

Machines cannot think of potential and qualitative changes. New knowledge comes from such transformations (human), not from the extension of existing knowledge (machines). Only human intelligence is social and can see the potential for change, in particular social change, that leads to a better life for humanity and nature.

March 31, 2023

What’s the problem with pensions?

The recent massive demonstrations against the Macron administration in France forcing through so-called pension reforms reveals the determined attempts of pro-capitalist governments in all the major economies to cut real wages when we are old and can no longer work.

The Macron government has forced by decree a ‘reform’ that raises the pension age to 64 years from 62 years. In Spain, where the retirement age has been fixed at 65 years for decades, the government is opting for an alternative solution to the so-called pensions problem. It is going to increase contributions from the incomes of younger higher earners to pay for older retirees.

Pensions are really deferred wages, deductions from income from work to pay for a decent income when people retire. After decades of work (and exploitation), workers, male and female, should be entitled to stop and enjoy the last decade or so of life without toil without being poverty. Literally, they will have earned it. But capitalism in the 21st century cannot ‘afford’ to pay decent living incomes as state pensions when workers retire. Why? Well, the mainstream arguments are several-fold.

First, the demographic trends, particularly in the advanced capitalist economies, mean more people are reaching retirement age and fewer people are at working age. So the argument goes, higher ‘age dependency rates’ mean that those at work have to pay more in taxes for those who are not working. For example, in Spain there are three people of working age for every single pensioner; by 2050 that dependency ratio will be just 1.7 to one.

The second argument is that life expectancy has risen so much and people are much healthier, that the ‘gap years’ between stopping work and dying have risen far too much. For example, Spain’s life expectancy is 83 — one of the world’s highest. So people should work longer to reduce that gap to where it was before.

The cruel irony is that the pensions cuts that the French and Spanish governments seek to impose for reasons of demography are taking place when life expectancy in the major economies has started to fall. In the first decade of this century, life expectancy increased by nearly three years every decade. But now life expectancy at retirement is two years less than previously expected.

World average life expectancy (years at birth)

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/padr.12477

And what is ignored is the huge disparity in life expectancy between lower income people retiring and very dependent on state pensions and better-off people with additional company pensions. For example, almost eight years separates the life expectancy of retirees living in exclusive parts of London like Kensington and Chelsea to those living in Glasgow. A 60-year old man in the Scottish city might live a further 19 years. For his London contemporary that rises to 27 years. In both places women live almost three years longer than men. Indeed, the fall in life expectancy in the UK has forced the government to delay until 2026 raising the retirement age (already at 67 years) to 68 years.

And the third argument is the cost to the public purse. The argument is that too much public money goes to pensioners, thus reducing available funds for other important public services and benefits. Governments are forced into running budget deficits that increase public debt and so raise interest costs that eat into public spending. It’s true that pensions in France are higher than most other EU countries. And Spain’s net pre-retirement income average at 80% is actually ahead of France’s 74 per cent and an average of 62 per cent in the OECD.

But does that mean the aim should be to ‘level down’ pensions to those of the UK, for example, which has one of the lowest state pensions relative to average earnings in the OECD? Surely, the aim should be to ‘level up’ to the best?

And the pensions deficit in France is tiny compared with the cost of measures introduced in response to the pandemic (€165bn) and the energy shock (around €100bn), as well as President Macron’s commitments to invest more in nuclear power (€50bn) and defence (€100bn by 2030).

Nevertheless, mainstream economists continue to see the ‘problem of pensions’ as causing excessive government spending and deficits. Here is what one such analysis put it in vigorously supporting Macrons’ attack on French state pensions. “France’s pension reform, centred on prolonging the age of retirement to 64 from 62, should ensure the progressive rebalancing of the pension system by 2030, given unfavourable demographic trends and a widening deficit. The reform sends a strong signal to European partners and international institutions of France’s intent to preserve medium-term fiscal sustainability and introduce supply-side reforms.” So it’s to encourage the others to level down.

Similarly, that paper for capitalist strategy, the UK’s Financial Times, called Macron’s move ‘indispensable’. “Plugging a hole in the pension system is a gauge of credibility for Brussels and for financial markets which are again penalising ill discipline.” The FT went on: “If unchanged, the (French) pension system will run annual deficits of between 0.4 per cent and 0.8 per cent of gross domestic product over the next quarter-century; (there are more benign scenarios of break-even, but these suppose a productivity miracle). It is not a catastrophic hole: the minimum contribution for a full pension is already quite exacting at 41.5 years — and it is climbing to 43 — even if a pension age of 62 looks generous. Yet it is a hole that needs to be filled.”

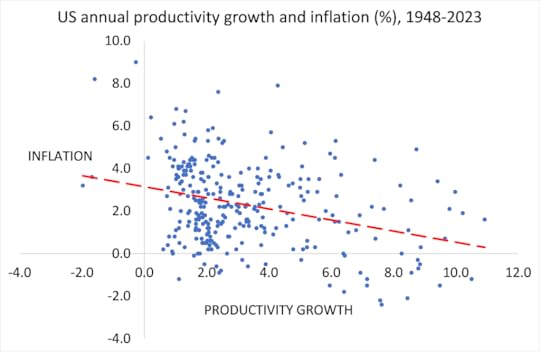

Two things here. So this (not so large) deficit hole has to be filled? Even if we accept that it does, why does it have to be filled by forcing people to work longer or make higher contributions from their wages now to pay for pensions later? And also, note that “there are more benign scenarios, but they suppose a productivity miracle’. And this is the crux of the ‘pensions problem’. Without recognizing it, the FT exposes the mainstream arguments as bogus.

Ten years ago, I called the ‘pensions crisis’ (yes, it was doing the rounds then) a myth. Then I put it this way: “There are enough resources if they are properly organised and fully used. It’s both a political choice and question of economic organisation. Does a country want to use its resources so that people can stop work at the age of 60 or 65 and have enough income to live on in reasonable comfort, or not? It can be done.”

It depends on two things: first, that an economy creates enough resources and expands sufficiently to cater for its elderly population that may also be getting larger as a share of the population. And second, given finite resources, decent pensions can be provided by cutting out other calls on government revenues i.e. such as bailing out the banks; increased arms spending; more subsidies for private corporations to invest in fossil fuels; and lower taxes for top earners and corporations etc.

It is not a choice between good pensions or a good health service or education system. Ten years ago, I showed that just a 1% pt sustained rise in average real GDP per capita in the major economies could deliver enough extra revenue to governments to easily maintain current pension levels and terms with something to spare. And that would be without changing the allocation of public money to defence (now set to increase in all EU economies to at least 2% of GDP each year) or chasing down the tax havens and avoidance schemes by which companies and rich individuals lose revenues for governments by up to 10% a year.

And I emphasise the word a ‘sustained’ increase in real GDP growth. Every 8-10 years, capitalist economies have slumps in output and investment which significantly hit government revenues and often lead to substantial bailouts of banks and multi-nationals, further reducing revenues to pay for public services and pensions. A planned economy, where production is not based on profitability and not subject to regular and recurring crises, could soon ‘afford’ decent pensions.

Instead, in the 21st century, capitalist economies are experiencing slowing economic growth and already three slumps, with the prospect of another right now. The World Bank has just published a truly shocking report on the prospects for the world economy for the rest of this decade. The Bank reckons that the world’s maximum long-term growth rate is set to slump to a three-decade low by 2030. Between 2022 and 2030 average global potential GDP growth is expected to decline by roughly a third from the rate that prevailed in the first decade of this century—to 2.2% a year. For countries like France, the growth rate will be well below 2% – indeed just 1.2% a year.

Given that the working age population in France, like many other advanced economies in the Global North, is set to fall further in the rest of this decade, growth depends higher productivity from a shrinking labour force (unless governments force people to stay in work longer or work longer hours). But productivity growth is slowing to almost a trickle as investment in value-creating sectors of economies stagnates. So increased productivity is unlikely to compensate for a declining labour force.

And there is no answer to be found in privatising pensions. Already, corporate pension schemes are failing to meet workers needs. First, private pension managers take a sizeable cut in fees for managing pension funds.

Second, these investment managers cannot deliver sufficient returns on investing in stocks and bonds, so that private pension funds often go into deficit. And pension fund managers resort to risky investments to try and boost returns. That can lead to crises and losses – for example, the meltdown in UK pension funds in so-called “liability driven investment” schemes (LDI) last year when bond yields rocketed, forcing the Bank of England to provide emergency credit of £65bn.

And third, most private schemes are no longer ‘final salary’ ie pensions based on your wage when you retire, but on the amount of contributions you make from your wages as you go, and so relying on pension fund managers to invest wisely. Private pension schemes are a con – and anyway, most workers do not have one.

The French option for state pensions is to raise the retirement age so that people have to work longer. And that includes those who do tough, physically or mentally, stressful work that cannot be continued for more than a few decades, if that. Some might say that even 64 years is ok because in many countries the retirement age is way higher (at 67 years in the UK now). But the majority of French people do not agree. For them, the pension age was a hard fought right, along with better social services that people do not want to lose.

As one French sociologist put it: “For 40 years, successive governments have been asking the French people to accept ‘reforms’ reducing social rights. These have degraded public services in health, education, transport and so on, while eroding purchasing power and worsening working conditions … The French are fed up.”

March 27, 2023

Banking crisis: is it all over?

Bank stock prices have stabilized at the start of this week. And all the key officials at the Federal Reserve, the US Treasury and the European Central Bank are reassuring investors that the crisis is over. Last week, Fed Chair Jerome Powell called the U.S. banking system “strong and resilient” and there was no risk of a banking meltdown as in 2008-9. US treasury secretary Janet Yellen said that the US banking sector was “stabilizing”. The US banking system was strong. Over the pond, ECB president Lagarde has repeatedly told investors and analysts that there was “no trade-off” between fighting inflation by raising interest rates and preserving financial stability.

So all is well, or at least soon will be, given the massive liquidity support that the Fed and other US government lending bodies are offering. Also the stronger banks have stepped in to buy up the collapsing banks (SVB or Credit Suisse) or plough cash into failing ones (First Republic).

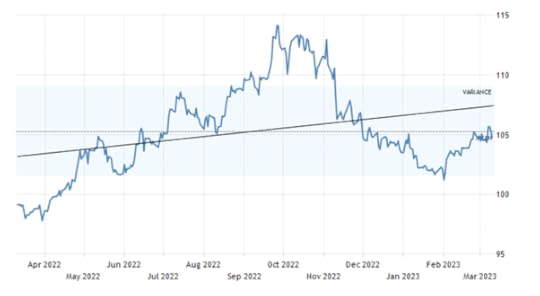

So is it all over? Well, it ain’t over til it’s over. The latest Fed data from show that US banks lost $100bn in deposits in one week. Since the crisis started three weeks ago, while the large US banks have added $67bn, the small banks have lost $120bn and foreign-owned banks $45bn.

To cover these outflows and to prepare for more, US banks have borrowed $475bn from the Fed; split evenly between large and small banks, although relative to their size, small banks borrowed twice as much as the large ones.

The weakest banks in the US have been losing deposits for over two years to the stronger banks, but $500 billion has been withdrawn since the collapse of SVB on 10 March and $600bn since the Fed started raising interest rates. That’s a record.

Where are all these deposits going? Half of the $500bn in the last three weeks has gone into the bigger, stronger banks and half into money market funds. What is happening is that depositors (mainly rich individuals and small companies) are panicking that their bank might go bust like SVB and so are switching to ‘safer’ big banks. And also depositors see that, with rising interest rates across the board driven by central banks raising rates to ‘fight inflation’, there are better savings rates to be found in money market funds.

What are money market funds? These are not banks but financial institutions that offer a better rate than banks. How do they do this? They offer no banking services at all; MMFs are just investment vehicles that pay higher rates on cash. They can do this by in turn buying very short-term bonds like Treasury bills that offer just a slightly higher rate of return. Thus, the MMFs make a small interest gain but with huge amounts. More than $286bn has flooded into money market funds so far in March, making it the biggest month of inflows since the depths of the Covid-19 crisis. While that is not a massive shift relative to the size of the US banking system (it is less than 2% of the $17.5tn of bank deposits) it shows that nerves remain on edge.

And let’s remind ourselves how this all started. It started out with Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) closing its doors. Then the cryptocurrency Signature Bank. Then another bank First Republic had to be bailed out by a batch of large banks. Then over in Europe, Credit Suisse bank collapsed in less than 48 hours.

The immediate cause of these recent bank failures, as always, was a loss of liquidity. What do we mean by that? Depositors at the SVB, First Republic and Signature started to withdraw their cash big time, and these banks did not have the liquid cash to meet depositor demands.

Why was that? Two key reasons. First, much of the cash that had been deposited at these banks had been reinvested in assets by the bank boards that have hugely lost value in the last year or so. Second, many of the depositors at these banks, mainly small companies, had found that they were no longer making profits or getting extra funding from investors, but they still needed to pay their bills and staff. So, they started withdrawing cash rather than building it up.

Why did the assets of the banks lose value? It comes down to the rise in interest rates across the board in the financial sector, driven up by the actions of the Federal Reserve to raise its basic policy rate sharply and quickly supposedly to control inflation. How does that work?

Well, to make money, say banks offer depositors 2% a year interest on their deposits. They must cover that interest, either by making loans at a higher rate to customers, or by investing the depositors’ cash in other assets that earn a higher rate of interest. Banks can get that higher rate if they purchase financial assets that pay more interest or that they could sell at a profit (but might be riskier), like corporate, mortgage bonds, or stocks.

Banks can buy bonds, which are safer because banks get their money back in full at the end of maturity of the bond – say five years. And each year the bank receives a higher fixed rate of interest than the 2% its depositors are getting. It gets a higher rate because it cannot have its money back instantly but must wait, even for years.

The safest bonds to buy are government bonds because Uncle Sam is (probably) not going to default on redeeming the bond after five years. So SVB managers thought they were being very prudent by purchasing government bonds. But here is the problem.

If you buy a government bond for $1000 that “matures” in five years (i.e., you get your investment back in full in five years), which pays interest at, say, 4% a year, then if your deposit customers get only 2% a year, you are making money. But if the Federal Reserve hikes its policy rate by 1%, the banks must also raise their deposit rates accordingly or lose customers. The bank’s profit is reduced. But worse, the price of your existing £1000 bond in the secondary bond market (which is like a second-hand car market) falls. Why? Because, although your government bond still pays 4% every year, the differential between your bond interest and the going interest for cash or other short-term assets has narrowed.

Now if you need to sell your bond in the secondary market to get cash, any potential purchaser of your bond will not be willing to pay $1000 for it but say only $900. That’s because the purchaser, by paying only $900 and still getting the 4%, can now get an interest yield of 4/900 or 4.4%, making it more worthwhile to buy. SVB had a load of bonds that it bought “at par” ($1000) but worth less in the secondary market ($900). So it had “unrealized losses” on its books.

But why does that matter if it does not have to sell them? SVB could wait until the bonds mature, and then it gets all its investment money back plus interest over five years. But here is the second part of the problem for SVB. With the Fed hiking rates and the economy slowing down towards recession, particularly in the start-up tech sector in which SVB specialized, its customers were losing profits and so were forced to burn more cash and run down their deposits at SVB.

Eventually, SVB did not have enough liquid cash to meet withdrawals; instead, it had a lot of bonds that had not matured. When this became obvious to depositors, those that were not covered by state deposit insurance (anything over $250,000) panicked and there was a run on the bank. This became obvious when SVB announced that it would have to sell much of its bond holdings at a loss to cover withdrawals. The losses appeared to be so great that nobody would put new money into the bank and SVB declared bankruptcy.

So a lack of liquidity turned into insolvency – as it always does. How many small businesses find that if only they had got a little more from their bank or an investor, they could have ridden out a shortage of liquidity to stay in business? Instead, if they get no further help, they must fold. That is basically what happened at these banks.

But the argument goes that these are one-offs and the monetary authorities have acted quickly to stabilize the situation and stop depositor panic. There are two things that the government, the Fed, and the large banks have done. First, they have offered funds in order to meet depositors demand for their cash. Although in the US, any cash deposits over $250,000 are not covered by the government, the government has waived that threshold and said that it will cover all deposits (for these banks only) as an emergency measure.

Second, the Fed has set up a special lending instrument called the Bank Term Funding Program where banks can obtain loans for one year, using the bonds as collateral at par to get cash to meet depositor withdrawals. So, they don’t have to sell their bonds below par. These measures are aimed at stopping the “panic” run on banks.

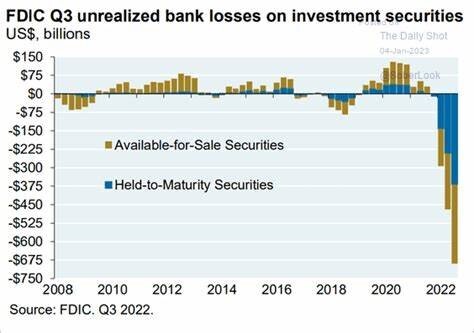

But here is the rub. Some argue that SVB and the other banks are small fry and rather specialist. So they do not reflect wider systemic problems. But that is to be doubted. First, SVB was not a small bank, even it specialized in the tech sector – it was the 16th largest in the US and its downfall was the second biggest in US financial history. Moreover, a recent Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation report shows that SVB is not alone in have huge “unrealized losses” on its books. The total for all banks is currently $620 billion, or 2.7% of US GDP. That’s the potential hit to the banks or the economy if these losses are realized.

Indeed, 10% of banks have larger unrecognized losses than those at SVB. Nor was SVB the worst capitalized bank, with 10% of banks having lower capitalization than SVB. A recent study found that the banking system’s market value of assets is $2 trillion lower than suggested by their book value of assets (accounting for loan portfolios held to maturity). Marked-to-market bank assets have declined by an average of 10% across all the banks, with the bottom 5th percentile experiencing a decline of 20%. Worse, if the Fed continues to raise interest rates, bond prices will fall further, and the unrealized losses will increase, and more banks will face a lack of liquidity.

So, the current emergency measures may well not be enough. The current claim is that extra liquidity can be financed by larger and stronger banks taking over the weak and restoring financial stability with no hit to working people. This is the market solution where the big vultures cannibalize the dead carrion – for example, the UK’s SVB arm has been bought by HSBC for £1. In the case of Credit Suisse, the Swiss authorities forced a takeover by the larger UBS bank for a price one-fifth of CS’s current market value.

And that is not the end of the coming problems. US banks are heavily into commercial real estate (CRE) assets ie offices, plants, supermarket malls etc. When interest rates were very low or even near zero before the pandemic, small banks loaded up on real estate development lending and CRE bonds issued by developers. Borrowing as a share of bank reserves accelerated from 25% a year to 95% a year in early 2023 in small banks and 35% for big banks.

But commercial premises prices have been diving since the end of the pandemic, with many standing empty earning no rents. And now with commercial mortgage rates rising from the Fed and ECB hikes, many banks face the possibility of more defaults on their loans. Already in the last two weeks $3bn of loans have defaulted as developers collapse. In February, the largest office owner in Los Angeles, Brookfield, defaulted on $784m; in March Pacific Investment Co. defaulted on $1.7bn of mortgage notes and Blackstone defaulted on $562m bonds. And there are $270bn more of these CRE loans due for repayment. Moreover, these CRE loans are highly concentrated. Small banks hold 80% of total CRE loans worth $2.3trn.

The CRE loan risk is yet to hit. But it will hit the regional banks, already reeling, the hardest. And it’s a vicious spiral. CRE defaults hurt regional banks as falling office occupancy and rising interest rates depress property valuations, creating losses. In turn, regional banks hurt the real estate developers as they impose stricter lending standards post-SVB. This deprives commercial property borrowers of reasonably priced credit, crimping their profit margins and pushing up defaults.