Michael Roberts's Blog, page 21

June 2, 2023

ECB: 25 years

The European Central Bank (ECB) turned 25 years yesterday on 1 June. The ECB is at the centre of the so-called euro experiment that established a single currency for (now) 20 countries in the Eurozone, covering nearly 350m people. The euro is the second-largest reserve currency as well as the second-most traded currency in the world after the United States dollar.

The euro is managed and administered by the European Central Bank (ECB, Frankfurt am Main) and the Eurosystem, composed of the central banks of the eurozone countries. As an independent central bank, the ECB has sole authority to set monetary policy. The Eurosystem participates in the printing, minting and distribution of notes and coins in all member states, and the operation of the eurozone payment systems. While some countries have exemptions, if a European country now wants to join the EU, it must also join the Eurozone and adopt the euro as its currency.

In celebrating the 25 years, current ECB president Christine Lagarde made a speech in which she argued for the success of the ECB in providing three things for Europe. “Stability, because the euro ensured that the Single Market could be insulated from currency fluctuations while making speculative attacks on euro area currencies impossible. Sovereignty, because adopting a single monetary policy at the European level would increase Europe’s policy independence vis-à-vis other large players. And solidarity, because the euro would become the most powerful and tangible symbol of European unity that people would encounter in their day-to-day lives.”

You could argue that the ECB had met these more ‘philosophical’ criteria. But what is missing from Lagarde’s list are other more real criteria for which the ECB is mainly tasked, namely controlling inflation across the EZ and ensuring that there are no banking and debt crises that threaten to split the Eurozone apart. Here the success story is seriously faulty.

On inflation, Lagarde claimed “For the ECB, our immediate and overriding priority is to bring inflation back down to our 2% medium-term target in a timely manner. And we will do so.” So she recognises that the ECB has failed so far in the current inflation spiral. And on debt, Lagarde admits “instability has arisen in other areas that were missing from the original design of the euro area, most painfully during the sovereign debt crisis.”

Back in 2019, when the Eurozone reached 20 years of existence, I published two posts: one on whether the euro had been a success; and another on its future prospects. On the former, I concluded that the real winners were the richer, more technologically advanced members in the northern ‘core’ and the losers were the more debt-ridden, weaker economies of southern Europe. And far from the euro and the ECB helping the latter to make strides towards convergence with the north, the opposite has been the case – the most serious moment being in the euro debt crisis of 2012-15.

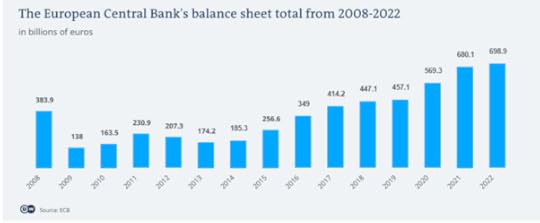

That led to a change of policy by the EZ leaders and ECB then headed up by former Goldman Sachs banker and head of the Italian central bank, Mario Draghi. He launched a new policy of supplying cheap credit with the ECB buying up EZ country government bonds in huge amounts to prop up the likes of Spain, Portugal and Italy (“whatever it takes” was the slogan). In the years between 2010 and 2016, the ECB’s balance sheet of credit rose from €163 billion ($151 billion) to almost €349 billion. Last year it stood at roughly €700 billion.

But that credit support came with harsh fiscal and monetary conditions policed by the ECB, so that any country that opposed them, like Greece in 2015, faced economic suppression by the ECB, the IMF and the EU Commission.

The ECB’s original mandate was to keep inflation in the EZ down to around 2% a year on average and to ensure the financial stability of the EZ banking system. Its success in meeting these mandates has not been great – despite all the supposed monetary powers of the ECB. In the first decade of the 21st century EZ inflation was stubbornly above 2%. Throughout the second decade leading up to the pandemic in 2020, EZ inflation remained well below 2% a year. And then of course, after the pandemic slump, there was the sharp hike in inflation to nearly 10%. The overall average inflation rate for the 25 years was 1.97% a year – so you could say that was close to the ECB target, but this outcome is more from luck than judgement, and certainly had little to do with ECB monetary policy.

Moreover, ECB inflation forecasts have been well out of line. Take the post-pandemic jump in prices. “Recent projections by Eurosystem and ECB staff have substantially underestimated the surge in inflation, largely due to exceptional developments such as unprecedented energy price dynamics and supply bottlenecks.” Forecasting is notoriously difficult, of course, but even so, it does not seem that the great minds and resources of the ECB (the number of employees at the ECB has doubled from around 1,600 in 2010 to around 3,500 today.) has achieved either control of inflation (how could that be possible in a capitalist economy?) or any clear idea of what causes inflation, so that proper forecasting models might be applied.

As for debt and banking crises, the ECB was unable to stop the euro debt crisis of 2012-15 – indeed its policies before that period of raising interest rates only accelerated it. It was a sovereign debt crisis caused by governments having to bail out the banking system in Europe with huge dollops of money and credits that left the public sector irreversibly in debt, squeezing public spending and raising taxes, and driving southern Europe into a debt depression. The ECB reacted with its own flood of credit, this time to governments. But in this sorry saga, the ECB reacted; it did not lead and it could not avoid the debt mess and ensuing slump.

Now in 2023, again it was a bystander to the current banking crisis caused by rising interest rates driven by central banks, including the ECB, attempting vainly to ‘control’ inflation. The collapse of the 167-year old Credit Suisse bank and its forced takeover by UBS with Swiss government funds took place with the ECB uninvolved.

What now for the ECB? Lagarde reckons: “with shifting geopolitics, digital transformations and the threat of a changing climate, there will be more challenges ahead which the ECB will need to address. We must continue to provide stability in a world that is anything but stable.”

In another recent speech Lagarde posed the risk of a fragmenting, multi-polar world: “the single most important factor influencing international currency usage is the “strength of fundamentals.” She meant economic fundamentals. And they are not good for the major economies and for the Eurozone; with poor productivity, investment and profitability. That’s a recipe for global fragmentation and conflict.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has apparently delivered more political unity within the region against ‘the enemy’, for now. But the economic fissures within the Eurozone between the richer and more advanced and the weaker and less advanced remain and will not be resolved. And if the global economy drops into a new slump in the next year, then those fault-lines will re-open yet again.

May 29, 2023

Acemoglu, AI and automation

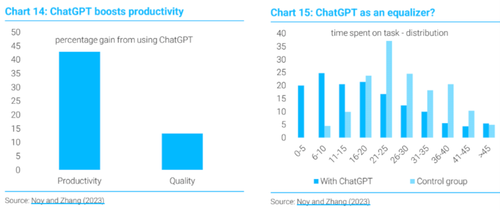

There is a new burst of techno-optimism emerging over the application of ChatGPT and LLMs. One analyst reckons that AI “has huge potential to boost economy-wide productivity” and cited a recent MIT study that showed a massive improvement in productivity while using ChatGPT. Also, much of the productivity gains were seen between 21 to 40-year-olds.

[image error]ChatGPT has gained 100 million users faster than any other application in history and these fast adoption rates are not confined to individual users. Major corporations, such as Bain & Company, have entered into deals with OpenAI to use generative AI in their strategy consulting business, while companies like Expedia have integrated ChatGPT through plug-ins.

So is ChatGPT etc a game changer for capitalism? MIT economics professor Daron Acemoglu is the expert on the economic and social effects of new technology, including the fast-burgeoning artificial intelligence (AI). He’s won the John Bates Clark Medal, often a precursor to the Nobel Prize.

But he is no techno-optimist. His research shows that major technological disruption — such as the Industrial Revolution — can flatten wages for an entire class of working people. In a recent interview in the Financial Times, Acemoglu said “capital takes what it will in the absence of constraints and technology is a tool that can be used for good or for ill.” Referring to the technology in the 19th century onwards, he went on: “Yes, you got progress, but you also had costs that were huge and very long-lasting. A hundred years of much harsher conditions for working people, lower real wages, much worse health and living conditions, less autonomy, greater hierarchy. And the reason that we came out of it wasn’t some law of economics, but rather a grass roots social struggle in which unions, more progressive politics and, ultimately, better institutions played a key role — and a redirection of technological change away from pure automation also contributed importantly.”

These comments echo the conclusions on the impact of technology that Friedrich Engels made during the height of industrial revolution in the mid-19th century. Back then, Engels argued that mechanisation shed jobs, but it also created new jobs in new sectors, see my book on Engels’ economics pp54-57. Marx also identified this in the 1850s: “The real facts, which are travestied by the optimism of the economists, are these: the workers, when driven out of the workshop by the machinery, are thrown onto the labour-market. Their presence in the labour-market increases the number of labour-powers which are at the disposal of capitalist exploitation…the effect of machinery, which has been represented as a compensation for the working class, is, on the contrary, a most frightful scourge. …. As soon as machinery has set free a part of the workers employed in a given branch of industry, the reserve men are also diverted into new channels of employment and become absorbed in other branches; meanwhile the original victims, during the period of transition, for the most part starve and perish.” (Grundrisse). The implication here is that automation means increased precarious jobs and rising inequality for long periods.

Acemoglu reaches similar conclusions to Engels and Marx. “I think one of the things you have to do as an economist is to hold two conflicting ideas in your mind at the same time,” he says. “That’s the fact that technology can create growth while also not enriching the masses (at least not for a long time). Technological progress is the most important driver of human flourishing but what we tend to forget is that the process is not automatic.” Under the capitalist mode of production for profit not social need, there is a contradiction, so “mathematically modelling and quantitatively understanding the struggle between capital — which benefits most from technological advancement —and labour isn’t an easy task.” Indeed.

Acemoglu’s own extensive research on inequality and automation shows that more than half of the increase in inequality in the U.S. since 1980 is at least related to automation, largely stemming from downward wage pressure on jobs that might just as easily be done by a robot. The result of automation in the last 30 years has been rising inequality of incomes. There are many factors that have driven up inequality of incomes: privatisation, the collapse of unions, deregulation and the transfer of manufacturing jobs to the global south. But automation is an important one. While trend GDP growth in the major economies has slowed, inequality has risen and many workers — particularly, men without college degrees — have seen their real earnings fall sharply.

Moreover, under capitalism, Acemoglu adds that not all automation technologies actually raise the productivity of labour. That’s because companies mainly introduce automation in areas that may boost profitability, like marketing, accounting or fossil fuel technology, but not raise productivity for the economy as a whole or meet social needs. “Big Tech has a particular approach to business and technology that is centered on the use of algorithms for replacing humans. It is no coincidence that companies such as Google are employing less than one tenth of the number of workers that large businesses, such as General Motors, used to do in the past. This is a consequence of Big Tech’s business model, which is based not on creating jobs but automating them.”

Acemoglu reckons modern automation, particularly since the Great Recession and the COVID slump, is even more deleterious to the future of work. “Put simply, the technological portfolio of the American economy has become much less balanced, and in a way that is highly detrimental to workers and especially low-education workers.” He reckoned that more than half, and perhaps as much as three quarters, of the surge in wage inequality in the US is related to automation. “For example, the direct effects of offshoring account for about 5-7% of changes in wage structure, compared to 50-70% by automation. The evidence does not support the most alarmist views that robots or AI are going to create a completely jobless future, but we should be worried about the ability of the US economy to create jobs, especially good jobs with high pay and career-building opportunities for workers with a high-school degree or less.” His analysis of automation’s effects in the US also applied to the rest of the major capitalist economies.

As Acemoglu once explained to the US Congress: “American and world technology is shaped by the decisions of a handful of very large and very successful tech companies, with tiny workforces and a business model built on automation.” And while government spending on research on AI has declined, AI research has switched to what can increase the profitability of a few multi-nationals, not social needs: “government spending on research has fallen as a fraction of GDP and its composition has shifted towards tax credits and support for corporations. The transformative technologies of the 20th century, such as antibiotics, sensors, modern engines, and the Internet, have the fingerprints of the government all over them. The government funded and purchased these technologies and often set the research agenda. This is much less true today.” That’s the business model for AI under capitalism.

Acemoglu baulks at conventional policy for dealing with tech-based inequality, such as universal basic income, because “it leaves the underlying power distribution the same. It elevates people who are earning and gives others the crumbs. It makes the system more hierarchical in some sense.”

Instead: “I think the skills of a carpenter or a gardener or an electrician or a writer, those are just the greatest achievements of humanity, and I think we should try to elevate those skills and elevate those contributions,” he says. “Technology could do that, but that means to use technology not to replace these people, not to automate those tasks, but to increase their productivity by giving them better tools, better information and better organisation.”

But he has a touching belief in the current US administration. “Biden is the most pro-worker president since Franklin D Roosevelt.” Acemoglu reckons “We need to create an environment in which workers have a voice” — though not necessarily the current union structure.” He looks to the ‘Germanic model’ in which the public and private sectors and labour ‘work together’, rather than the US’s neo-liberal regimen.

But Acemoglu hints at a better alternative: “You read evolutionary psychology or talk to many people who would say they want to be richer than you, more powerful than the other person and so on, and you think that’s the way it is. But then you talk to anthropologists, and they’ll tell you that for much of our humanity we lived in this egalitarian hunter-gatherer manner — so, what’s up with that?” An egalitarian society where automation is used to meet social need requires cooperative, commonly owned automated means of production. Rather than reduce jobs and the livelihoods of humans, AI under common ownership and planning could reduce the hours of human labour for all. That would be the real game changer.

May 27, 2023

The two Bs on inflation

A recent paper by mainstream heavyweights, Ben Bernanke (former Federal Reserve chief) and Olivier Blanchard (former chief economist at the IMF) has raised some eyebrows. Bernanke and Blanchard seek to argue that the inflationary spike in the US since the end of Covid pandemic slump was down to a sharp rise in ‘aggregate demand’ and not due primarily to supply blockages and weak productivity recovery in key sectors that I and others have argued – and certainly not due to ‘greedflation’, ‘price gouging’ or corporate profit mark-ups.

This is what they argue: “Ultimately, as many have recognized, the inflation reflected strong aggregate demand, the product of easy fiscal and monetary policies, excess savings accumulated during the pandemic, and the reopening of locked-down economies.” So the inflation burst was due to too much fiscal spending during the pandemic; too easy monetary policies (low interest rates) and a build-up of savings which were then spent in the recovery period.

So nothing to do with supply-side issues, then. But yet B&B go on to say that “initially, the inflation reflected primarily developments in product markets. To the extent that excessive aggregate demand set off the inflation, it did so primarily by raising prices given wages, through its contribution to higher commodity prices (which reflected other forces as well, including the war in Ukraine) and by increasing the demand for goods for which supply was constrained.” So inflation was kicked off by rising commodity prices, supply constraints and then the war in Ukraine – so supply-side issues after all!

Was it caused by excessive wage increases feeding through to prices? No, say B&B. “Our decomposition shows that, as of early 2023, tight labor market conditions still accounted for a minority share of excess inflation.”

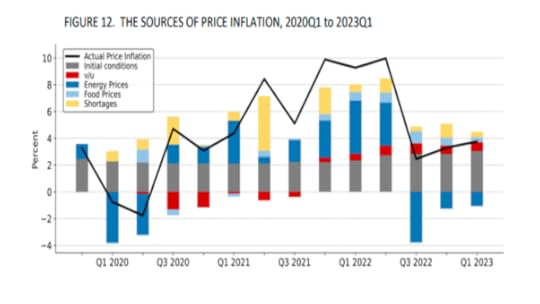

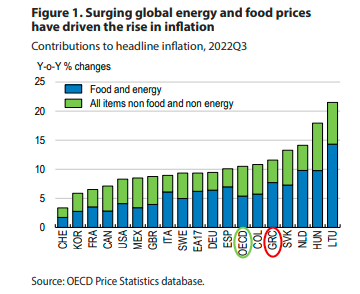

In particular, their decomposition of prices “yields several conclusions. First, the contributions of food and (especially) energy price shocks to the pandemic-era inflation were large. Energy price shocks in particular account for much of the rise of overall inflation in late 2021 and the first half of 2022, and the for the decline in inflation in the second half of 2022.” So again, it was commodity prices, not ‘aggregate demand’.

“Second, the combination of increased demand for durables and shortages associated with disrupted supply chains was the dominant source of inflation in 2021Q2, and the effects of supply chain problems, both direct and indirect, remained significant through the end of our sample period.” So it was also supply chain blockages.

“Third, and importantly, the contribution to inflation of tight labor-market conditions—the leading concern of many early critics of U.S. monetary and fiscal policies—was quite small early on, and indeed was negative in 2020 and early 2021 as labor markets suffered from the effects of the pandemic recession.” So ‘tight labor markets’ and excessive wage demands played no role in raising inflation – on the contrary.

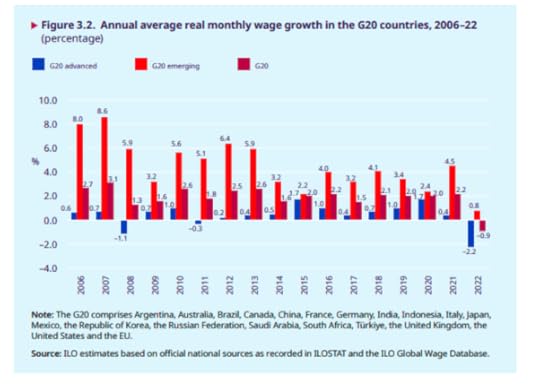

But B&B are concerned to ensure that the conventional mainstream theory is retained, namely that it is wage rises that cause inflation rises. They go on “over time, as the labor market has remained tight, the traditional Phillips curve effect has begun to assert itself, with the high vacancy-to-unemployment ratio becoming an increasingly important, though by no means dominant, source of inflation.” Even here, they temper their claim (“by no means dominant”). They must do so, because the graph above shows how small wage pressure has been (red block) compared to energy (dark blue) and food prices (light blue) and supply shortages (yellow).

What B&B want to push though is that now in 2023, attempts by workers to compensate for huge price rises hitting their real incomes by using their bargaining power in ‘tight labor markets’ will cause inflation to stay high. “according to our analysis, that share (wage share – MR) is likely to grow and will not subside on its own. The portion of inflation which traces its origin to overheating of labor markets can only be reversed by policy actions that bring labor demand and supply into better balance.”

So the tortuous policy to hiking interest rates by the Fed to ‘control inflation’ must be supported and maintained. “labor-market balance should ultimately be the primary concern for central banks attempting to maintain price stability”. In other words, weaken workers’ bargaining power by increasing unemployment through higher costs of borrowing to spend or invest.

Ironically, having advocated monetary tightening as the answer to inflation, apparently caused by excessive ‘aggregate demand’, they finish by saying that “Policymakers must be alert to the possibility that inflationary pressures can come from product markets as well as labor markets, for example, through unexpected changes in input costs or shifts in demand that collide with inelastic sectoral supply curves.”

Indeed. But don’t let that ‘possibility’ stand in the way of mainstream Keynesian theory on the causes of inflation and on the supposed efficacy of central banks hiking interest rates to ‘control inflation’ caused by factors beyond their control.

May 20, 2023

Greece: another chapter

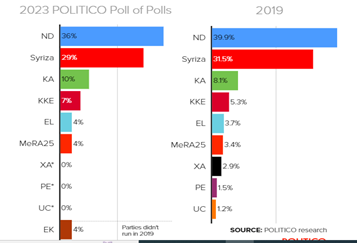

Greece has a general election today. The conservative New Democracy party under Kyriakos Mitsotakis currently forms the government, having defeated the leftist Syriza party under Alexia Tsipras in the 2019 election. In 2019, New Democracy took 39% of the vote to Syriza’s 32%. When Syriza took power in 2015 at the height of the euro debt crisis, Syriza polled 35% to ND’s 28%. Disillusionment with Syriza among previous strong working-class support was enough for the ND to gain a substantial victory in 2019. The former social democrat party PASOK, which had adopted neo-liberal policies during the debt crisis, polled only 10% and the Communists (who called for leaving the EU) fell to just 5%.

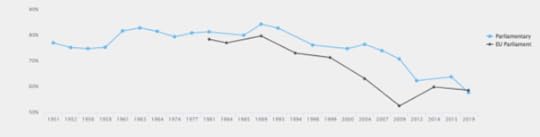

Although voting is formally compulsory, turnout was only 57% in 2019. Indeed, voter turnout has steadily fallen since Greece joined the EU in the early 1980s, but it did rise during the euro debt crisis between 2012 and 2015 of the euro debt crisis, which saw Syriza come to power and take on the Troika (the EU, the ECB and the IMF) against their attempt to impose huge austerity measures on the Greek people. Disillusionment with Syriza saw a drop in turnout in 2019.

The latest opinion poll puts ND on 36% and Syriza on 29%, with PASOK on 10% and the Communists on 7%. If that turns out to be accurate then, given that seats are distributed according to the proportion of votes for each party, no one party will get 151 seats in parliament and another election would follow in July. However, in that follow-up election, the leading party will receive a bonus of 50 extra seats (ensuring a ‘super-majority’ in parliament). So it seems likely that ND will be returned to office.

Why is the conservative New Democracy likely to win again? There is no great enthusiasm for either of the main parties and voter turnout is likely to be even lower than in 2019 (even though 17-year olds can vote for the first time). The ND government has lost some support because of its handling of the COVID pandemic; its secret spying (Watergate style) on Pasok’s private communications; and its admission that the terrible recent train crash, which led to the deaths of 57 people, was due to safety regulations being relaxed by the government.

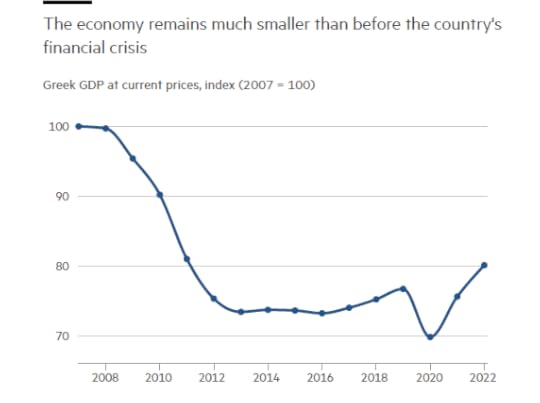

But that will not be enough for the ND to lose for two reasons. First, the ND government is riding on the relative recovery in the Greek economy (even in wages and employment for Greek workers). The Greek economy made one of the strongest recoveries from the Covid-19 pandemic, with real GDP up 8.4% in 2021 and another 5.9% last year. The average annual rate of change of Greece’s GDP has grown 3x during 2019-2022 as compared to the previous period in 2014-2018, from 0.5% to 1.8%. It is now even higher than the EU average rate of 1.3%, growing faster than many other advanced economies in Europe. A similar shift can be seen in GDP per capita.

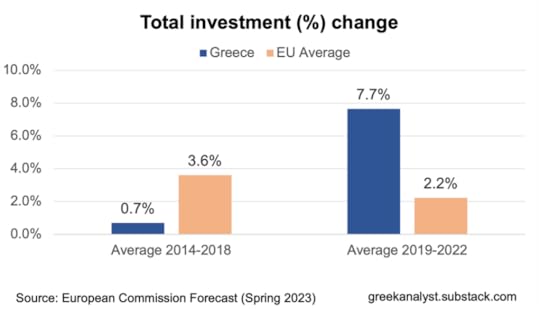

The amount of loans that are now non-performing on banks’ balance sheets has fallen from more than 50% in 2016 to close to 7%. Total investment in Greece has increased from an average annual rate of 0.7% during 2014-2018 to 7.7% between 2019-2022. At the same time, the EU average fell from 3.6% to 2.2%.

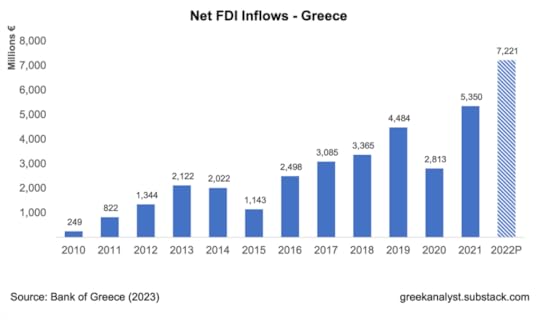

Foreign direct investment rose 50% last year to its highest level since records began in 2002. And the EU’s post-pandemic recovery fund is set to provide €30.5bn of grants and loans to Greece by 2026, equal to 18% of current GDP a long-term boost to the economy.

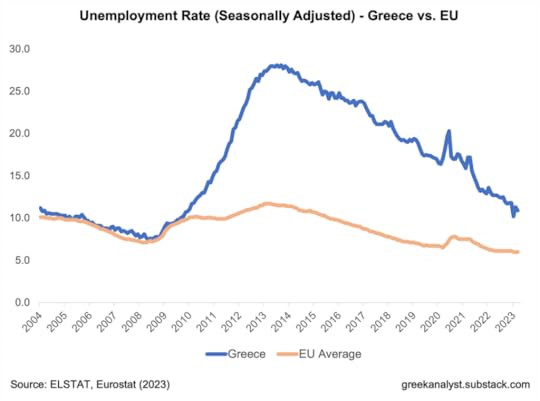

Tourism — the Greek economy’s largest sector, accounting for about one-fifth of GDP — last year rebounded to reach 97% of pre-pandemic levels. Foreigners are buying up Greek homes like there was no tomorrow (outpricing local Greeks). Unemployment in Greece has been steadily falling, inching closer to the EU average (although youth unemployment is still near 25%).

During the euro debt crisis, half a million Greeks (those educated and better-off) left the country. The ‘brain drain’ is now slowing. But with youth unemployment still nudging 25%, many young Greeks still say that, if they can, they will join the 500,000 who fled overseas during the debt crisis.

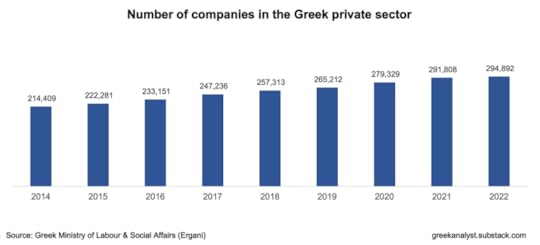

The number of companies in Greece has been steadily rising, increasing by almost 38% since 2014. Business activity has been booming.

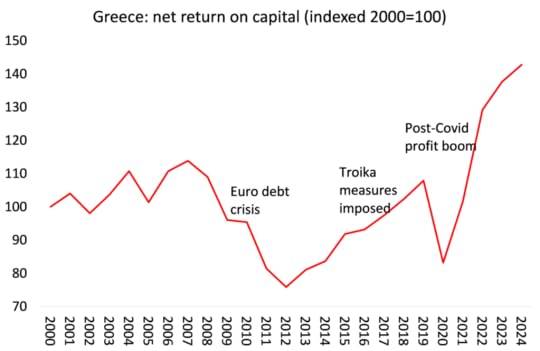

Investment is up and companies are expanding because the profitability of capital has risen sharply by: cutting wages and jobs; privatisations; and lower corporate taxes.

Source: AMECO, MR calcs

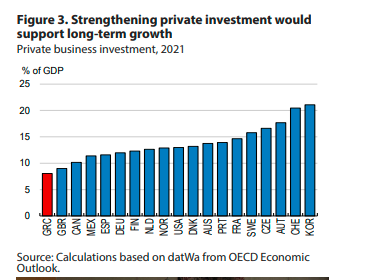

But there is a long way to go to turn Greek capitalism round. While profitability is up, productive investment in Greece remains among the lowest in the advanced capitalist world.

Nevertheless, this relative improvement in the economy is a key reason why the ND is likely to win. But the emphasis is on relative. The recent fast GDP growth since COVID is coming from a really low level of GDP. The Greek economy remains still some 20% smaller than before the Great Recession and euro debt crisis. And the recent investment rise is mostly in unproductive real estate investment.

Finally, a small capitalist economy like Greece, is dependent on what is happening globally. If the major economies enter a slump over the next year, then Greece will not escape. The relative improvement in the economy could be swept away by a new squall in the Aegean and Mitsotakis’ luck will run out. As the OECD puts it in its latest survey, “Greece’s strong recovery is facing mounting external headwinds”. Even without a slump, real GDP growth this year will slow to just 1.3% and reach only 1.8% next year – hardly a boom.

Surging energy prices, supply disruptions and renewed uncertainty, especially since Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, is sharply slowing the recovery.

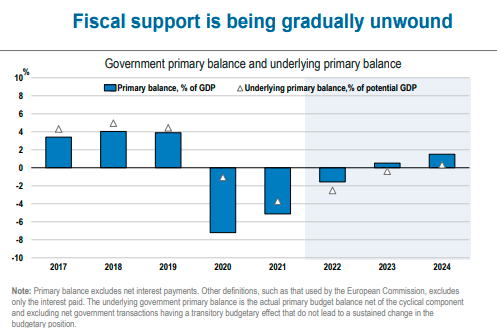

Also the Troika-set targets on fiscal spending were disrupted by COVID spending, so the new government must apply yet more severe spending cuts to restore those targets.

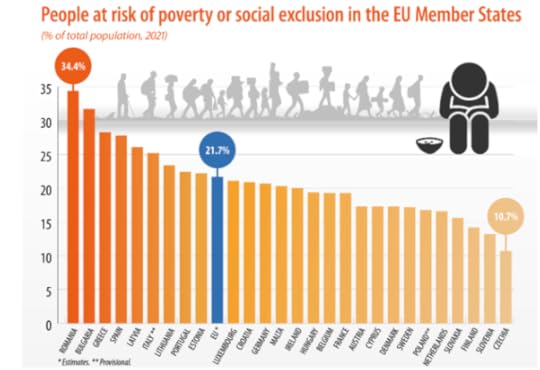

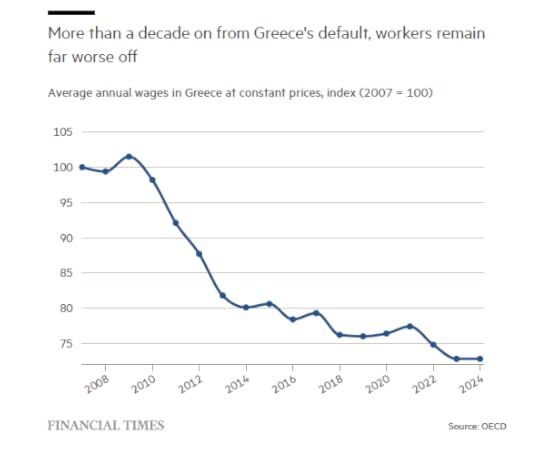

Above all, this recovery that pleases so much foreign investors, the banks and the corporate sector – and the Troika – has been at the expense of workers’ living standards. Profitability of Greek capital has risen, but Greek workers’ living standards have not. Painful austerity measures have left their mark on a country that now has one of the highest rates of poverty in Europe.

As Syriza leader Tsipras put it: “Greece has Bulgarian wages and British prices.” Real wages have fallen sharply since the debt crisis and the minimum wage is still lower than it was 12 years ago (and the minimum is the base for many wage settlements in Greece). Even Dimitris Malliaropulos, chief economist of the Greek central bank, admitted that Greek capitalism has recovered only by what he called “outright” cuts in wages.

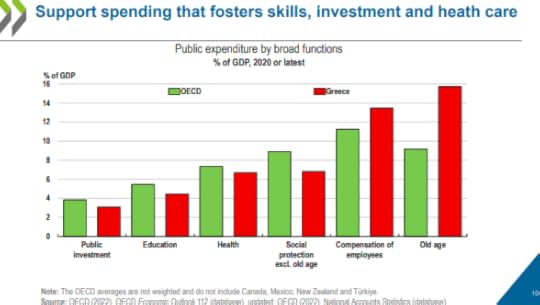

And even though the humungous public debt to GDP ratio, which reached 206% during the pandemic, is now down to 171%, the lowest level since the start of the euro debt crisis, that is still the highest in Europe by some distance – so fiscal austerity will be on the policy agenda for decades ahead. And on nearly every key indicator of public spending that matters, Greece is still way behind.

Only in defence spending is Greece ahead – at 3.5% of GDP, it’s the highest in NATO!

The other main reason that the ND is likely to win is that Syriza disillusioned its working-class support when it capitulated to the Troika in 2015. Back then, in the face of a massive media campaign and threats by the Troika leaders to vote yes to their terms, the Greek people voted 60-40 to reject the austerity measures in a referendum. But immediately afterwards, Syriza ignored the result and agreed to the Troika terms.

I related and discussed the momentous events of 2015 in many posts at the time. I won’t go over the arguments presented then by the mainstream and within the left over what policy to adopt and what mistakes were made. You can read my views here.

But also see this excellent account of the Greek debt crisis by Eric Toussaint. for which I wrote a preface. Syriza’s capitulation to the Troika despite the vote of the Greek people and its implementation of their demands in return for funding ensured victory for the ND in 2019. The legacy of that defeat in 2015 and the revival of Greek capitalism at the expense of Greek workers’ livelihoods since remains a black mark against the Syriza leaders.

May 19, 2023

G7: where is that recession?

The G7 leaders meet this weekend in Hiroshima, Japan, the site of the first atomic bomb holocaust dropped by American bombers on the city in August 1945, leading to the deaths of at least 100,000 citizens. But the G7 leaders’ main deliberations will not be about that, but instead on how to ‘contain’ China and ‘protect’ Taiwan from Chinese ‘aggression’ through further militarization of the island as a thorn in the side of Chinese leaders. It’s a form of what the British police call ‘kettling’, namely to surround and contain demonstrators in public protests. It is no accident that, with the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) is now expanding its role into Asia, that Ukrainian leader Zelensky has been invited to address the G7 leaders. As a counter, the Chinese are holding a conference of central Asian states in Xian. Such are the machinations of the intensifying geo-political conflict.

But this blog deals with economics and the G7 meeting is an opportunity to consider the state of world economy five months into 2023. My post last December on the economic prospects for 2023 was entitled “the impending slump”. And I said that “Never has an impending recession been so widely expected. Maybe that means it won’t happen – given the record of mainstream economic forecasters! But this time the consensus looks set to be right.”

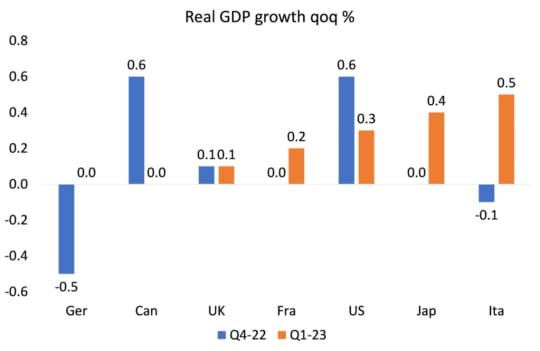

Well, five months in and there has been no slump – at least, not by the very crude definition of mainstream economics of a ‘technical’ recession, where an economy’s real GDP contracts for two successive quarters. Several G7 economies have been pretty close to meeting that criterion of a slump: Germany and Italy recorded a contraction in Q4-22; Germany and Canada stagnated in Q1-23 and the UK barely grew in both quarters. France was not much better and the US, the best performing G7 economy, halved its growth rate in Q1-23.

The US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the body usually referenced to decide whether there is a slump in the US – its criterion covers many more economic indicators. Here is how the NBER defines it:

“Because a recession must influence the economy broadly and not be confined to one sector, the committee emphasizes economy-wide measures of economic activity. The determination of the months of peaks and troughs is based on a range of monthly measures of aggregate real economic activity published by the federal statistical agencies. These include real personal income less transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, and industrial production. There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions. In recent decades, the two measures we have put the most weight on are real personal income less transfers and nonfarm payroll employment.”

So the NBER’s definition of a slump is more judgement than a rigid set of indicators. Most important of those is whether real personal incomes are rising or falling and whether employment is rising or falling. In the last two quarters, US real personal income rose 0.2% in Q4-22 and just 0.05% in Q1-23 (that is basically flat). So no contraction there yet, but slowing nearly to a halt.

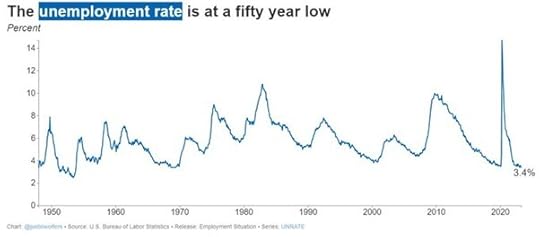

As for employment, although slowing in growth through much of 2022, employment rose by 0.6% in Q4-22 and at the same pace in Q1-23. Indeed, much is made of the low unemployment rates in the US and the rest of the G7. In the US, the rate is at a 50-year low. And it’s the same story in the other G7 economies, if at different levels.

However, both these key NBER indicators are lagging indicators of a slump. They are confirmations of a slump already in progress. Rising unemployment and falling incomes only happen when a slump is underway, which is why the NBER uses them. But these indicators are no guide to whether there is “an impending slump”. Under capitalist production, if companies are reducing investment and laying off their workforce and so reducing the overall wage bill, sales revenues will have been falling and profits declining well before that. So we must look elsewhere for leading indicators.

Marxist economic theory suggests that slumps will happen when the profitability of capital starts falling; eventually leading to a fall in total profits in an economy. Those profits can further be squeezed by increases in the cost of capital i.e interest costs on borrowing.

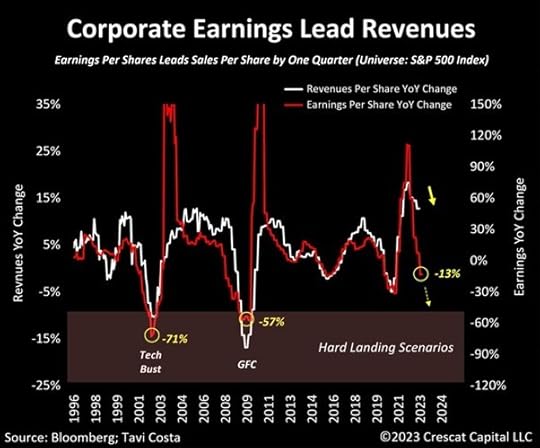

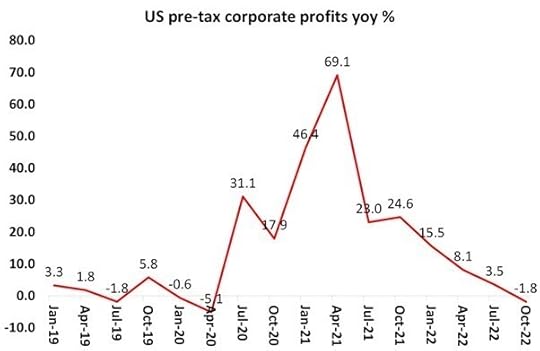

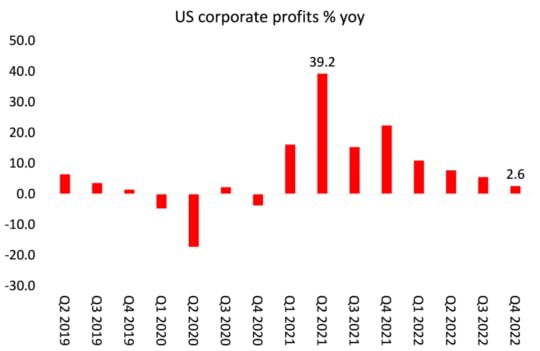

And on these criteria, the signs are rising of an impending slump. US corporate profits are suffering the biggest downturn in seven years. With the Q1-23 corporate earnings season over, the profits of S&P 500 companies are estimated to have dropped 3.7% on average compared to a year ago. This is the second straight quarter of earnings declines and forecasts for the current Q2-23 that we are now in is for a further fall of 7.3%, with no better in Q3-23. This suggests a longer profit recession than during the pandemic. An earnings drop of more than three quarters was last seen in 2015-16, when the Federal Reserve started its last interest-rate hiking cycle.

According to historical data, changes in earnings tend to precede changes in sales revenue by approximately one quarter. As corporate earnings have fallen 13% in the last two quarters, we can expect sales revenues to follow.

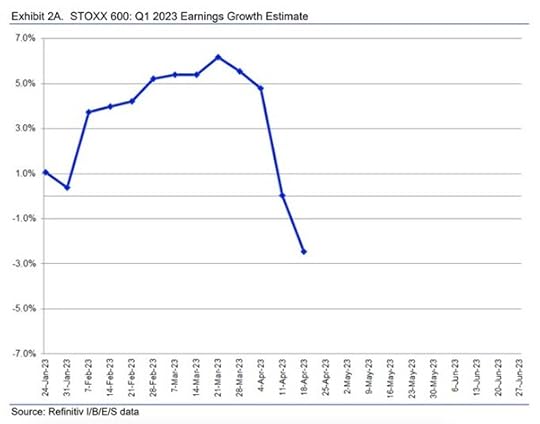

The corporate profit drop is not confined to the US. In Europe, estimates for corporate earnings are for a fall of 2.5% yoy in Q1-23, 5.4% in Q2-23 and 7.4% in Q3-23.

In previous posts I have pointed out that all the recent talk (understandable) of record high corporate profits and the hiking of margins as the main cause of rising inflation is now out of date. If the current cost of living crisis starting in 2022 was caused by ‘greedflation’, as some argue, it won’t be the case during 2023.

Profit margins (profit per unit of production), having reached historic highs last year, are falling back and total corporate profits are now going south. In Q4-22 non-financial corporate profits fell 5.4%.

Then there is the rising cost of borrowing to fund production and investment as the Fed and other central banks hike interest rates and tighten credit at an unprecedented pace, supposedly to ‘control’ inflation in prices. US money supply is contracting for the first time in 90 years.

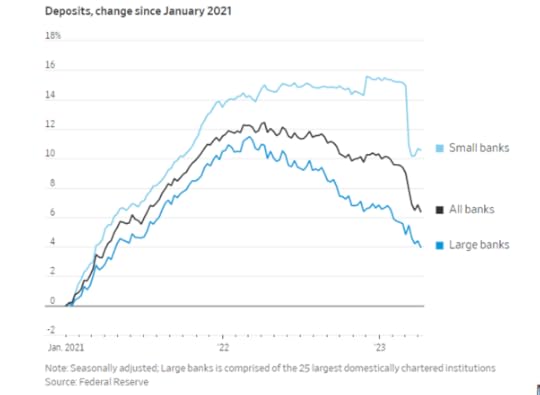

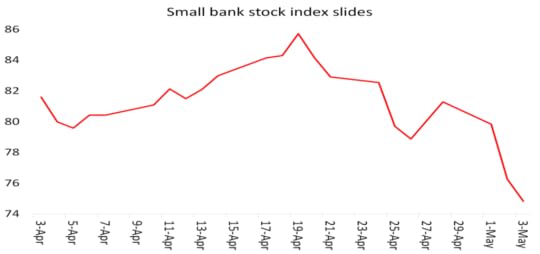

The result of these interest-rate rises has been a smouldering banking crisis in the US and Europe, as smaller and weaker banks become insolvent because the value of their assets in bonds have dropped sharply and depositors have fled to better yielding institutions or because companies and households need to spend their savings to meet rising bills.

Higher funding costs for banks will squeeze profits. Economists at Goldman Sachs estimate every 10% decline in bank profitability reduces lending by 2%. If the share of Fed interest-rate changes that are passed on to bank deposit rates, sometimes called “deposit betas,” reach levels seen in 2007—the last time the Fed raised rates close to current levels—that could lead to a 3-6% decline in lending in the US. Goldman expects that could reduce economic output by 0.3-0.5 percentage points this year, pushing the economy into recession.

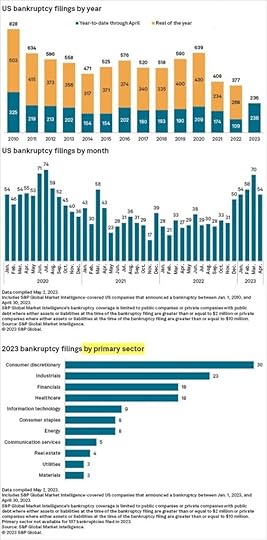

That’s the banks. Behind them is the growing crisis in non-financial companies. Since 2000, non-financial corporate debt across America and Europe has grown from $12.7trn to $38.1trn, rising from 68% to 90% of their combined GDP. The rising costs of servicing this debt is pushing the weaker corporate ‘zombies’ and ‘fallen angels’ into bankruptcy.

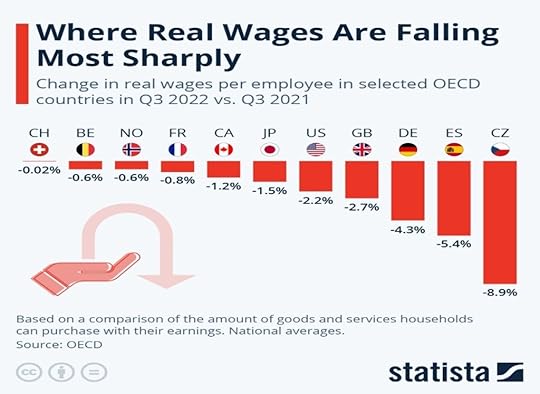

Whether the major economies go into an outright slump in 2023 is a moot point. Economic growth will be feeble at best, while ‘sticky’ inflation rates reduce real wage growth to very low rates (or into continued falls). In the US, the average decline in real wages was just over 2% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2022. In Europe, Germany and Spain saw even more pronounced declines in purchasing power, with real incomes falling by just over 4% and 5% respectively. Real wages in the Eurozone have fallen by 8% since the end of the pandemic slump in 2020. In Germany, real earnings have plunged by 5.7% in the last year, the largest real wage loss since statistics began.

And there are signs too that the ‘hot’ labour market is cooling. The post-Covid expansion of jobs (if mainly low paid and part-time) saw high vacancy and quit rates in the US. They are now dropping, if still above pre-pandemic levels.

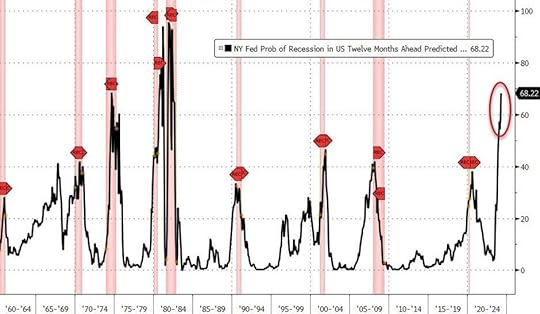

The odds that the US will fall into a recession at some point over the next 12 months have risen to a 40-year high, according to a probability model from the New York Federal Reserve. The probability that the country will enter a recession within the next year has risen to 68.2 percent, which is the highest level since 1982. Indeed, the Fed’s recession risk indicator is now greater than it was in November 2007, not long before the subprime crisis, when it stood at 40 percent.

What won’t be discussed at the G7 meeting this weekend is the accelerating debt and currency crises in the Global South. I have reported on this before and will return to the issue in another post. But that debt disaster will ensure that any slump in the G7 economies will spread quickly to the rest of the world.

May 16, 2023

Robert Lucas: the rationality of capitalism

Robert Lucas has died at the age of 85. Lucas was a leading mainstream neoclassical economist at the University of Chicago – the bastion of neoclassical equilibrium economic theory. In 1995, Lucas received a ‘Nobel prize’ for his theory of ‘rational expectations’. He was regarded by Greg Mankiw, the author of the main mainstream economics textbook used in universities, as “the most influential macroeconomist of the last quarter of the 20th century.”

It is an irony, given the body of his work, that when Lucas started studying economics, he considered himself a “quasi-Marxist” because he reckoned that it was the economic foundation of society that was the driver of history, not the ideas of individuals. The irony is that his main contribution to mainstream economics was eventually to present a theory that economic change was driven by the ‘rational’ action of ‘agents’ i.e, individuals as consumers.

What is ‘rational expectations’ theory? Apparently, economic changes are the product of agents who make ‘rational’ decisions on the basis of available information to maximise the ‘utility’ for each agent over their lifetime. Individual agent expectations thus drive output and prices in an economy, not some aggregated forces like class or exploitation. As economies are driven by individual expectations, markets tend towards some equilibrium state that ensures supply and demand are balanced – and are only disturbed by ‘shocks’ or by wrong decisions by monetary and fiscal authorities.

Lucas was widely acclaimed because he furthered mainstream theory that markets could work without crises or distortions as long as individuals has sufficient information to make ‘rational decisions’ on their own interests. So the reality of crises and inequalities was due not to capitalist markets but to ‘irrational’ decisions by authorities or unions interfering with markets.

In particular, Lucas attacked the Keynesian ‘aggregate demand’ theory of economies, namely the Keynesian conclusion that total demand could fall below total supply in an economy, leading to periods of high unemployment. Lucas argued that if governments intervened to increase money supply or increase spending to boost aggregate demand, they would distort the ‘rational expectations’ of individuals and only make things worse.

Moreover, Keynesian theory had no theoretical model that justified its conclusion of inadequate aggregate demand. And all empirical results must have a foundation in theory, in particular, a theory of individual agent decisions. Without that any policy conclusions drawn from Keynesian analysis would be wrong. This was called the Lucas critique, which came to dominate the application of macroeconomic analysis.

One example that Lucas presented was the failure of the Keynesian Phillips curve, namely that there was a trade-off between unemployment and inflation. Lucas argued that the apparent inverse relation between the two had been proven wrong in the 1970s when inflation rose with unemployment. That showed you cannot base policy on a statistical correlation without a theoretical base.

Lucas was right on both counts – in the sense that the Phillips curve has been proven empirically false as a guide to the relation between employment and inflation – see the body of work on this in several posts. But also, it must be right that any empirical evidence must be weighed and used to confirm or falsify a theory.

But the question is: what theoretical model? One of Lucas’s students, Paul Romer agreed with Lucas that Keynesian economic models “relied on identifying assumptions that were not credible.” And that the “predictions of those Keynesian models, the prediction that an increase in the inflation rate would cause a reduction in the unemployment rate, have proved to be wrong”. But that did not make Lucas’ own ‘rational expectations’ theory correct.

Nevertheless, Keynesian economists capitulated to the Lucas critique. During the Great Moderation (when inflation and unemployment were falling in the 1990s – and profitability was rising), mainstream Keynesian economics concentrated on explaining ‘business cycles’ or ‘fluctuations’ in an economy using ‘modern’ techniques of modelling from what it called ‘microfoundations’. Econometric analysis like the Phillips curve were ditched because such ‘correlations’ between employment and inflation had been proved wrong. The job now was not to look at macro or aggregate data but to work out some ‘model’ that started with some premises of ‘rational’ agent (consumer) behaviour or preferences and then incorporate some possible ‘shocks’ to the general equilibrium of the market and consider the number and probability of possible outcomes.

Thus were born the Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models. They had equilibrium because they started from the premise that supply would equal demand ideally; they were dynamic because the models incorporated changing behaviour by individuals or firms (agents); and they were stochastic as ‘shocks’ to the system (trade union wage push, government spending action) were considered as random with a range of outcomes, unless confirmed otherwise).

This was a ‘bastardisation’ of the radical aspects of Keynesian theory,namely that capitalism did not grow smoothly and could not without periods of slump and depression. But now these only happened as ‘shocks’ to the harmony of the market. Lucas had succeeded in his critique in reducing Keynesian macro economics to a weak and feeble beast. No wonder he got a Nobel prize at the height of the neoclassical, neoliberal ascendancy in 1995.

Given his victory over the Keynesians; given the apparent success of the advanced capitalist economies in the 1990s; and given the neoliberal policies of reduced government ‘interference’ and ‘independent’ central banks, Lucas was confident that harmonious capitalist development was here to stay. In 2003, he made the now infamous statement that “macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.” As Romer remarked it “Using the worldwide loss of output as a metric, the financial crisis of 2008-9 shows that Lucas’s prediction is far more serious failure than the prediction that the Keynesian models got wrong.”

The reality of ‘irrational’ capitalist markets eventually exposed Lucas’ rational expectations theory.

May 13, 2023

Erdogan’s Turkey: end of an era?

Turkey holds a very important general election tomorrow. Incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been in office for more than 20 years. In the election out of an 86m population, there will be over 50m voting with 5.3m new young voters; including Kurds who make up about 18% the population and could be decisive in the result.

For the first time, Erdogan is in danger of losing the election. The latest opinion polls put the opposition alliance slightly ahead of Erdogan’s grouping, but neither side looks like obtaining 50%, necessary to avoid a run-off in two weeks. The election for the parliamentary seats also looks like resulting in neither side having a majority.

The opposition is composed of an alliance of several disparate parties led by Kemal Kilicdaroglu, a retired civil servant, who has vowed to “restore Turkish democracy” and improve ties with the West. Kılıçdaroğlu has led CHP, the secularist party of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey’s founding father, since 2010. At the last minute, the opposition gained a boost when an independent candidate, Muharrem Ince, pulled out of the race, with his support likely to go to the opposition.

Turkey is the 19th largest economy in the world and a member of the G20. During the first decade of Erdogan’s presidency, Turkey’s economy had a degree of expansion, if very much based on a myriad of infrastructure projects and funded by foreign loans. But when people protested over many reckless developments, in particular, in the months-long Gezi park protests in 2013 over a planned urban development in central Istanbul, Erdoğan responded with a violent crackdown.

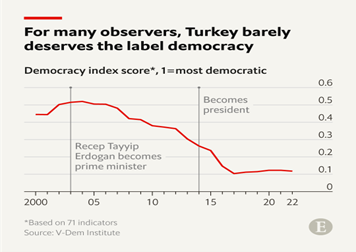

Erdogan changed the constitution from a parliamentary system to one where the president held most powers. The slide towards authoritarianism gathered pace after a 2016 coup attempt by sections of the military. Erdogan launched a sweeping purge of the security services and the civil service, while imposing a state of emergency that remained in place when elections were held two years later. Since then, he has spent much of the past decade locking up opponents, cowing the media and deposing elected officials and university professors. There are now more journalists in prison than in any other country. Selahattin Demirtaş, the former Kurdish leader, has been in jail for seven years on charges of ‘supporting terrorism’ and Istanbul mayor Imamoğlu from the opposition faces a possible ban from politics after a court convicted him in December of “insulting” electoral officials.

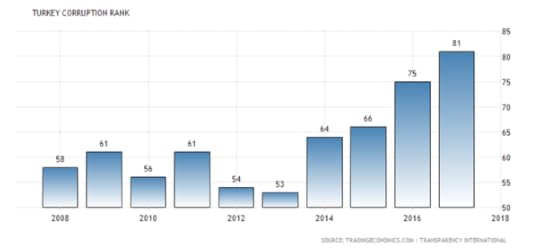

Corruption in the government has increased and Turkey moved further up the corruption ladder under Erdogan.

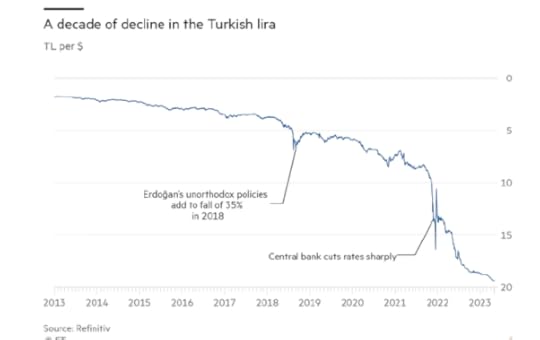

But since the COVID pandemic slump, things have turned for the worse for Erdogan. His electoral support (based mainly on rural voters with religious beliefs) has dropped – already all the major cities are run by opposition administrations. Now he faces a possible defeat for the presidency. The main reason for his loss of support is the state of the Turkish economy with inflation near 50% a year; economic growth stuttering; the trade deficit widening; the currency diving and foreign debt at record levels.

The economic situation was exacerbated by the horrendous earthquake that devastated southern Turkey in February, killing more than 50,000 people and displacing another 3m. Erdogan’s handling of the disaster has been heavily criticised. At the same time, runaway inflation under Erdoğan’s watch has hurt every household. The price of a kilo of onions, vital for Turkish cuisine, has increased around five-fold in the capital city of Ankara over the past 18 months.

Erdogan has refused to follow orthodox capitalist policies to control inflation, namely to raise interest rates, as most central banks have done globally. Describing interest rates as “the mother and father of all evil”, he has sacked central bank governors if they adopted conventional inflation policy i.e raising rates. But with interest rates kept well below inflation, the lira currency has weakened sharply against the dollar and the euro and so the cost of servicing foreign loans for industry has rocketed.

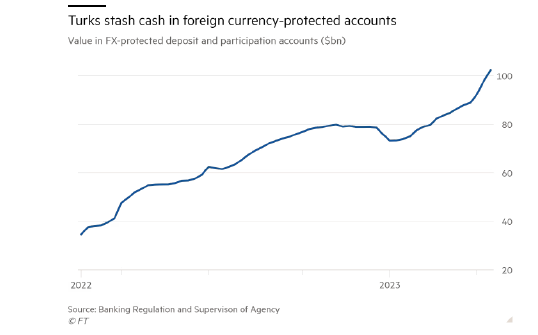

The government introduced special savings accounts in 2021 to reimburse depositors if the lira weakened. These accounts now hold the equivalent of $102bn. So they pose a big liability to the government budget, forcing the central bank to ‘print’ money to fund government spending, further increasing the downward pressure on the lira.

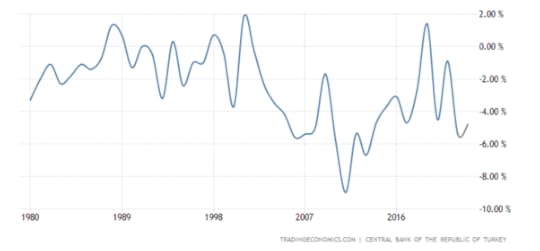

The trade deficit continues to widen sharply as imports paid for in foreign currency have risen. The overall current account deficit relative to GDP has more than doubled during the Erdogan years.

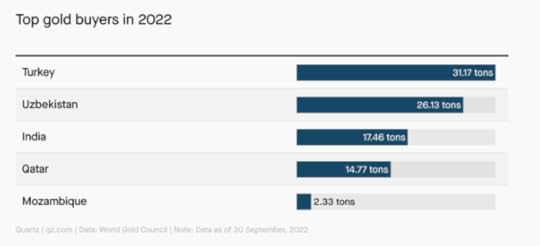

And there has been a massive increase in speculative gold imports (now one-third of all imports) to use instead of lira to make foreign transactions. Erdogan has called people to buy gold to avoid using dollars or euros: “Those who keep dollar or Euro currency under their mattresses should come and turn them into Liras or gold.” These imports come from Russia which is selling gold for its war effort and to evade sanctions.

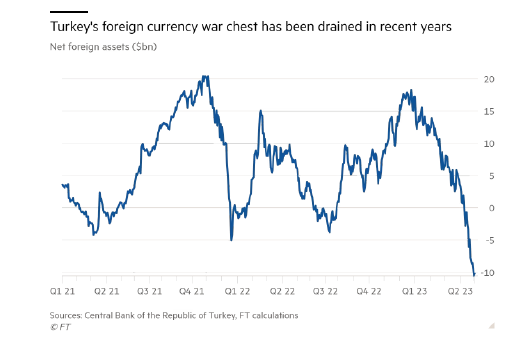

Even so, Turkey has run out of foreign currency to pay its debts, increasingly resorting to swapping agreements (in effect short-term loans) with friendly Gulf nations like the United Arab Emirates, from which Turkey has borrowed Emirati dirhams in exchange for lira. But as the election starts, Turkey’s net foreign currency reserves are down to a negative $67billion.

Foreign investors are avoiding Turkey like the plague. Foreign ownership of Turkish government bonds has fallen from 25% in May 2013 to below 1% in 2023. Similarly, investors have pulled out more than $7 billion from the Turkish stock market. Turkey banks and corporations are now in dire trouble. Turkey’s non-financial companies’ foreign currency liabilities now outstrip their foreign exchange assets by more than $200bn.

What the Turkish economy shows is that trying to run economic and monetary policy in the opposite direction to that of the major advanced capitalist economies cannot work unless capital controls are introduced and domestic investment is directed through a plan towards productive sectors. Instead, Erdogan is trying to have a successful capitalist economy completely exposed to international capital flows and based on credit-fuelled investment in real estate and other unproductive sectors.

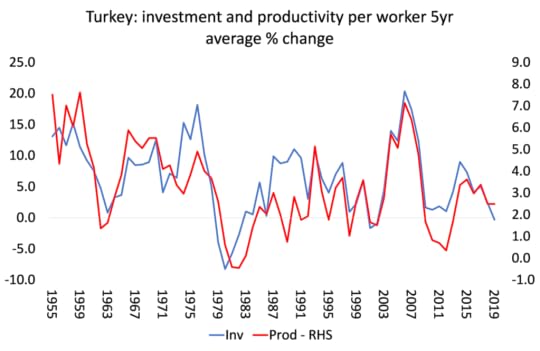

A key measure of economic success is growth in the productivity of labour. That has been heading south. The reason is that investment growth in productive sectors per worker has been slowing fast. In the first decade of Erdogan’s rule, there was double-digit growth in both investment and productivity. But since the end of the Great Recession of 2009, growth in the second decade has been less than 3% a year on average.

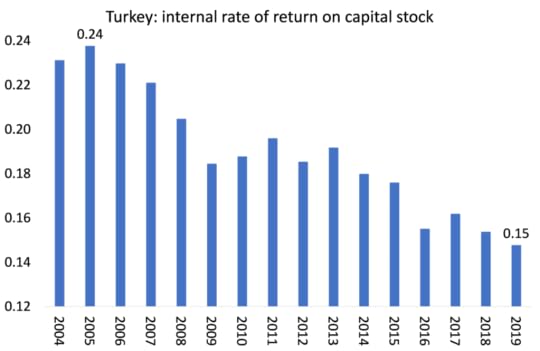

And behind this slowing investment and productivity growth is the steep decline in the profitability of Turkish capital since the end of the Great Recession.

Source: Penn World Tables 10.0

If the opposition wins, they are not offering a socialist alternative to Erdogan’s maverick economics. Opposition leader Kılıçdaroğlu told the Financial Times last month that one of his priorities would be establishing an independent central bank so that it could set interest-rate policy without government interference! That would mean a sharp rise in interest rates as conventional policy was adopted and probably more fiscal austerity. Some supporters of the opposition have argued that “interest rates might need to rise to 30% to break inflation. This would maximise foreign investment, boosting economic growth while alleviating the pressure on the lira.” But this assumes that hiking interest rates would work to lower inflation – a recession is more likely to result.

Under Kılıçdaroğlu there would be a swing back towards the European Union and support for NATO in Ukraine. Reviving Turkey-EU relations would be high on the agenda should he win the presidency. Here the policy of the opposition becomes clear: orthodox economic policy and a reliance on foreign capital.

But will foreign capital deliver? Turkey has massive investment needs. The US$50 billion cost of building new homes in regions hit by the two recent earthquakes is just one example. There is deep poverty and inequality. Since the coronavirus pandemic, Turkey’s poverty rate has reached 21.3% of the population, according Turkish Statistical Institute’s annual survey, just released . The severe material deprivation rate — defined as the rate of people unable to afford at least four of key necessaries — is 16.6%. According to the 2022 results, 33.6% of the non-institutional population had heating problems due to isolation and problems in their dwellings such as leaking roof, damp walls/floors/foundation, rot in window frames/floors etc.

According to the survey, Turkey’s gini coefficient, a statistical measure used to gauge economic inequality, worsened by 0.015 points to 0.41 in 2020 — a level comparable to those of Brazil, Mexico and South Africa. It’s the largest gap between rich and poor in eleven years under Erdogan. The ratio of the income of the richest 20% of the population to that of the poorest 20% increased to 8 in 2020 from 7.4 the previous year. The richest 20% received 47.5% of the total income, while the poorest quintile got only about 6%. In terms of deciles, the top 10% of the population received 32.5% of the total income, while the share of the bottom decile was 2.2%, with the ratio increasing to 14.6 from 13 over a year.

The election outcome is not certain. Even if Kılıçdaroğlu were to get 50% of the vote and win in the first round, there is no guarantee that Erdogan would accept the result, just Trump did not in the US 2020 election. He may find ways to block the result and demand a new vote. That could push the county into a major convulsion. If nobody gets 50%, a second round would take place at the end of May.

May 6, 2023

Britain’s royal rip-off

Today in Britain King Charles III will be crowned in a ‘coronation’. All the other remaining monarchies in Europe (Scandinavia, Netherlands, Belgium, Spain) don’t bother with a coronation, but the British monarchy has had a much more prominent role in helping British state build its huge global empire in the 19th century. A coronation is part of the rituals developed to cement this feudal relic into the state machine.

The cost of the coronation to public funds is estimated at £100m. The British royal family could easily afford to pay for this jamboree itself. Recent calculations put the personal wealth of Charles at £1.8bn. Some estimates put that even higher. The British monarch is “one of the world’s wealthiest individuals” according to the Financial Times, owning property worth £15.6 billion as well as the £1.8 billion held in lands called the Duchies of Cornwall and Lancaster. Brand Finance, a brand valuation consultancy, puts the whole family’s wealth at £44 billion!

A key part of the monarch’s wealth is the land that they claim to own. The royal family owns more than 1% of all the land in the UK – by comparison, the top 10 landowners in the United States collectively hold 0.7 percent of the land.

The family’s right to these lands and the income earned from them is dubious. Surely, these lands should be part of the national estate, not owned by one family. Indeed, after the civil war in England in the mid-1640s, when England had a republic for ten years under Cromwell, these lands were nationalised. With the restoration of the monarchy under the last King Charles, the Stuart royal family regained them. It was the policy of the Labour Party in the 1930s to bring them into public ownership – but the Labour government after WW2 failed to implement that.

The Duchy of Cornwall estate has grown to more than 130,000 acres in 20 counties in southern England and Wales. The assets include farmland and woodlands, as well as the Oval cricket ground in London, offices, vacation rentals and residential developments. The family also benefits from the Crown Estate — yet another collection of land holdings, this one originating from the Norman Conquest in the 11th century. Today, this £15.6 billion ($19.4 billion) portfolio includes marquee properties such as London’s Regent Street, the Windsor Estate, shopping malls, much of the coastline and even the seabed out to 12 nautical miles offshore. Wind farm leases on the seabed are contributing to soaring profits.

Different from the duchies, the Crown Estate is managed by the government and its profits go to the state treasury. But a set percentage then goes to the royals in the form of the “Sovereign Grant,” earmarked for official travel and entertainment, property upkeep and staff salaries. A “golden ratchet” clause means the yearly grant can’t go down even if profits do. The latest Sovereign Grant amounted to £86.3 million — or £1.29 per person in Britain (roughly $1.60). In addition, security for the royal family is paid for separately out of the Metropolitan Police’s budget, and this is estimated to be considerably greater than the sovereign grant.

Other parts of the British monarch’s huge wealth are in obscure possessions like the royal philatelic collection, considered the best stamp collection in the world, containing hundreds of thousands of stamps, some of which were harvested by Charles’s great-grandfather, George V, from the British Post Office and colonies, worth at least £100m. Also, Charles’ father Philip and the king’s grandmother, the queen mother, were avid collectors of art and purchased many pieces at bargain prices that would, if sold today, realise many times the original price tag. They include a Monet bought by the queen mother in Paris shortly after the second world war, when prices were low, for £2,000. An art valuer estimated it could now be worth £20m. In addition, almost 400 pieces of art that known (there may be more) in the “private” or “personal” royal collections are valued at £24m. Many of these were ‘gifts’ from foreign potentates.

The crown that King Charles III will wear at today’s coronation is five pounds in weight of solid gold, velvet, ermine and gems. Another crown is adorned with 2,868 diamonds. Charles will also be handed bejewelled scepters, swords, rings and an orb. Afterwards, he will travel through the streets of London in a golden carriage. Indeed, the value of all the 54 privately owned jewels ‘owned’ by the monarch is estimated at £533m.

And there are some other bizarre private rights. The new king will technically own all the swans in England and Wales, and a number of sea creatures, including all the whales, dolphins and porpoises in the waters around the United Kingdom.

These are the physical assets, but also the royals get free services eg they live in palaces and other homes funded by the state but for their own exclusive personal use. Indeed, there is a real difficulty in disentangling the family’s private wealth from public ownership. The Royal family has a fleet of luxury cars for their use in public activities and events. But these “state cars” are often used privately, such as when Princess Eugenie, who has never been a working royal, arrived at her wedding in a “state” 1977 Rolls-Royce Phantom VI worth £1.3m.

A recent policy states that gifts received in an “official capacity” are “not the private property” of the royal family. Still, the ambiguity of “official” allowed the late Queen Elizabeth to claim horses from world leaders as personal gifts that didn’t need to be declared.

And then there is tax. Or the lack of it. Charles did not pay a single penny of inheritance tax on the fortune the late Queen left him last year. The £1bn Duchy of Cornwall estate – previously inherited by Charles and recently passed on to his heir Prince William – is not liable for either corporation tax or capital gains tax. The Duchy of Lancaster provides whoever sits on the throne with lucrative annual payments of around £20m a year. Again, no tax. Charles has “volunteered” to pay income tax. As the Guardian newspaper put it: “Volunteering to pay tax feels a little like a wanted criminal volunteering to hand himself over to the authorities. It doesn’t seem to be something the rest of use typically get a choice in.” It is compulsory for the rest of us as part of a social contract that does not apply to this royal family.

The usual response to these points is that the British monarch is doing the country a ‘public service’. And King Charles is apparently keen to ensure that he is seen to do this. And even more that we should all do our bit. Charles has urged everybody to celebrate his kingship by helping out at the local food bank.

The British monarchy is a particular example of an archaic feudal institution that has been converted into a capitalist one for the purpose of representing and enhancing the idea of empire. The British empire, built up from the mid-18th century until the end of the 19th century, was one of the greatest imperialist projects ever. Sustaining an inherited family monarchy on top was a vital ingredient in sustaining the empire.

The current British royal family are called the Windsors. They had only a tenuous claim to being the current royal family. The royal website admits there were 52 candidates with a better claim to the throne than the Windsors’ ancestor, Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover, when he became George I in 1714. So they are German in origin and were originally called ‘Saxe-Coburg and Gotha’ – until the first word war with Germany forced a name change in 1917. The family were closely related to both the German and Russian absolute monarchies.

Many in the family have had extreme political views. A book by the US biographer Kitty Kelley, which was banned from sale in Britain, recounts that Princess Margaret, Elizabeth II’s sister, walking out of the film Schindler’s List complaining of “tiresome movies about the Holocaust”: Kelley: “What she resented was the lingering stench of the wartime German connection that continued to hang over her family. Their secrets of alcoholism, drug addiction, epilepsy, homosexuality, bisexuality, adultery, infidelity and illegitimacy paled alongside their relationship with the Third Reich.”

Few remember King Edward VIII (Margaret’s uncle) who was forced to abdicate in 1936 and who then backed Nazi Germany as Europe’s saviour. There are photographs of the future Queen Elizabeth giving the Hitler salute as a child in 1933, coached by her Nazi-supporting uncle. Elizabeth’s husband, Prince Philip of Greece, had his own Nazi links. His sisters married German noblemen, one of whom, Prince Christoph of Hesse, was an SS colonel on Heinrich Himmler’s personal staff. They named their son Karl Adolf in honour of the Führer.

The royal “traditions” being acted today supposedly stretch back deep into the history of Britain. But the rituals of coronations, royal weddings, state openings of parliament and state funerals are actually an artificial product developed in the 19th century to sustain the British empire. Back in 1952, when Elizabeth II started her reign, over 70 countries and territories were part of ‘her’ empire. But that empire was already disappearing. At her death, Elizabeth remained head of state in only 14 countries beyond Britain. And now six Caribbean countries have indicated they plan to go the same way as Barbados and end the connection with the British monarchial state and its exploitation of slavery in those islands.

As long ago as 1844, Engels noted that: “This loathsome cult of the King…the veneration of an empty idea…is the culmination of monarchy”. Yet the new monarch’s coronation will be widely celebrated and watched. The British monarchy retains a majority of support. According to the latest poll, of those asked, 62% of Britons favoured keeping the monarchy. But that’s down from 75% only ten years ago. And 25% want the monarchy replaced by an elected head of state. Moreover, among the youngest Britons (18-24 years) only 36% want to maintain the monarchy. And a majority of Britons do not want the government to pay for Charles’ coronation.

May 5, 2023

Comments pause in May

I have decided to pause approval on all comments during May, except for those who have not commented before and/or those who want to ask a question. Regular commentators can now take a break for a few weeks.

Rates up, economy down

The two main central banks in the advanced capitalist economies, the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB), raised their ‘policy’ interest rates again this week. The policy rate sets the floor for all borrowing rates in these economies. Both central banks hiked their rates by another 0.25%, so the Fed’s rate now stands at 5.25% and the ECB’s at 3.7%. This compares with just 0.25% and 0% respectively two years ago.

The professed aim of these hikes is to ‘control’ inflation and drive the currently high rates back to the so-called target rate that both central banks have of 2%. I and others have argued firmly, with evidence, that this monetary tightening policy will have little effect on getting inflation down because the causes of inflation do not lie in excessive money supply (the monetarist theory) or in excessive wages driving up prices (the Keynesian theory). Neither of these theories is backed up empirically.

The reason for the accelerating inflation of the last two years is to be found in the restriction of supply, both in production and transportation, partly from supply-chain blockages after the COVID slump, partly from the Russia-Ukraine war and partly from very low productivity growth in the major goods sectors of the world economy. The shortage of supply has enabled the multi-national energy and food producers to raise prices to extremes –see the huge profits made by the oil majors. These raw material costs have then been fed through by corporations in price rises to the ‘end consumer’ – mostly households. It’s been profits that have gained the most from the inflationary spiral, not wages. Real wages (ie after deducting inflation) in just about every economy have fallen in the last two years.

Over the last two years there has been an average rise in prices of around 15% (and much higher in energy and food). The headline inflation rate in the major economies has only just started to subside because of the end of supply-side blockages and because the major economies are slowing fast towards a recession and real incomes are falling. The monetary policies of the Fed and the ECB have not been the drivers of inflation reduction. And yet, the central bank leaders continue to parrot the story that this painful process of interest rate increases cannot be avoided and is the only way to get inflation down. Remember the comments of Bank of England chief economist: Huw Pill: “Somehow in the UK, someone needs to accept that they’re worse off and stop trying to maintain their real spending power by bidding up prices, whether through higher wages or passing energy costs on to customers etc.”

If you strip out the falling prices of energy and food, the underlying inflation rates in the US and Europe remain ‘sticky’. Indeed, ‘core’ inflation is still close to 6% yoy in both areas, more than three times the central banks’ target of 2% inflation.

The impact of central bank rate hikes has not been so much on driving down inflation as on accelerating economies into a slump; and on generating a banking crisis as weaker banks collapse in the face of rising borrowing costs and falling prices of the bond assets they hold. In Europe, the big drop in the demand for loans by both households and companies is a telling sign of the impact of monetary tightening – while the liquidation of the historic Swiss bank, Credit Suisse, is an indicator that the banking crisis is not confined to the US.

Eurozone loan demand dives

In the US, it is a similar story. There the banking crisis rolls on, first with the collapse of First Republic Bank last week, swallowed up by JP Morgan with sweeteners from the government; and then immediately after the latest hike by the Fed, the news that another Californian bank PacWest had called for extra finance in order to survive. The small banks stock index has dived as investors fear further busts ahead.

Despite this, Jay Powell, head of the Fed, argues that the banking crisis is under control (like inflation) and that recession in the US economy will also be avoided – even though the Fed’s own economists are forecasting a “mild recession” in the next two quarters of this year, before any recovery. Indeed, despite the banking debacle, the Fed has returned to reducing its bond holdings (ie tightening credit).

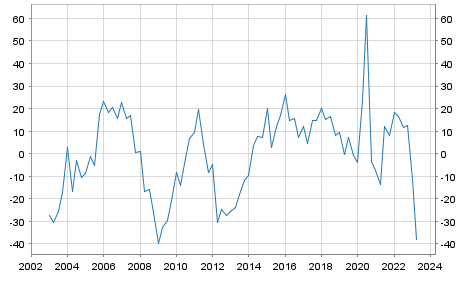

Federal Reserve balance sheet $bn

But behind the confident tone of Powell lies uncertainty. The Fed appears likely to hold off further hikes and hope that inflation will fall without any further measures. In the Fed’s press conference, Powell commented: “I mean there is a sense that, you know, we’re much closer to the end of this than to the beginning. That, you know, as I mentioned, if you add up all the tightening that’s going on through various channels, we feel like we’re getting close or maybe even there.” But he also made clear that there was no prospect of any reduction in the policy rate either. So the pain will continue.

The ECB was even more hawkish. ECB President Lagarde said in her press conference that “We are not pausing and have further to go. We are continuing the hiking process. We are on a journey and have not got there yet.” She was explicit that the aim of the ECB was to drive down the economy. “Headline inflation is coming down and credit lending is slowing. But this tighter monetary policy has not affected the ‘real economy’ yet. We need to see that leg of the process happen.”

Workers, particularly in Europe, are fighting hard to restore their losses in real incomes by obtaining increased wages. But that can only mean lower profits if there is no increased productivity out of the workforce. And productivity growth is falling in the US, down 2.7% in the first quarter of this year and more or less flat in the Eurozone.

Profit margins (profit per unit of production), having reached historic highs last year, are falling back and total corporate profit growth is slowing fast.

This will lead eventually to falls in productive investment and bankruptcies among the smaller and weaker corporations. Inflation rates will then fall (even though they will still be higher than before COVID), but only at the expense of rising unemployment and recession.

Michael Roberts's Blog

- Michael Roberts's profile

- 35 followers