Michael Roberts's Blog, page 17

November 28, 2023

Power and progress

Another in my series of book reviews.

Daren Acemoglu is a leading expert on the impact of technology on jobs, people and economies. I have referred to his work before in various posts.

Now in conjunction with a colleague, Simon Johnson, he has a new book out entitled ‘Power and Progress – a thousand- year struggle over technology and prosperity’. This book does not give us much chapter and verse in empirical evidence of the impact of technology on productivity growth or on the incomes of the many as opposed to the few. But the authors have done that in previous papers and works cited in my posts.

Instead, in Power and Progress we get a sweeping historical account of how technology has taken humanity forward in terms of living standards but also often created misery, poverty and increased inequality.

Acemoglu and Jonson ask the question: “Aren’t we more prosperous than earlier generations, who toiled for a pittance and often died hungry, thanks to improvements in how we produce goods and services?” They answer: “Yes, we are greatly better off than our ancestors. Even the poor in Western societies enjoy much higher living standards today than three centuries ago, and we live much healthier, longer lives, with comforts that those alive a few hundred years ago could not have even imagined. And, of course, scientific and technological progress is a vital part of that story and will have to be the bedrock of any future process of shared gains.”

But they argue that this was not an automatic (sic) result of technology, but rather “shared prosperity emerged because, and only when, the direction of technological advances and society’s approach to dividing the gains were pushed away from arrangements that primarily served a narrow elite. We are beneficiaries of progress, mainly because our predecessors made that progress work for more people. As the eighteenth-century writer and radical John Thelwall recognized, when workers congregated in factories and cities, it became easier for them to rally around common interests and make demands for more equitable participation in the gains from economic growth…. Most people around the globe today are better off than our ancestors because citizens and workers in early industrial societies organized, challenged elite-dominated choices about technology and work conditions, and forced ways of sharing the gains from technical improvements more equitably.”

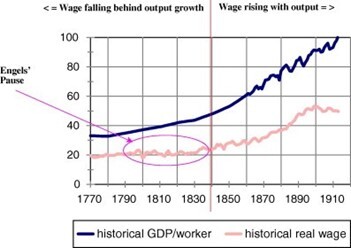

Acemoglu and Johnson point out the ‘industrial revolution’ in Britain and later in Europe and the United States did not lead to a rise in average real incomes for most workers until well into the second half of the 19th century.

They concur with the analysis of Friedrich Engels in his book, The condition of the working class in England, written in 1844, that as hand weavers and workers in other handcraft sectors lost their jobs to machines in the cities, they were pauperised while rural workers and their families coming to the cities to work in factories were paid a pittance.

It took the rise of labour organisations, government legislation and the beginnings of some welfare distribution to bring about a significant rise in comes, according to the authors.

They also point out that “The Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century was a period of rapid technological change and alarming inequalities in America, like today. The first people and companies to invest in new technologies and grab opportunities, especially in the most dynamic sectors of the economy, such as railways, steel, machinery, oil, and banking, prospered and made phenomenal profits…. Businesses of unprecedented size emerged during this era. Some companies employed more than a hundred thousand people, significantly more than did the US military at the time. Although real wages rose as the economy expanded, inequality skyrocketed, and working conditions were abysmal for millions who had no protection against their economically and politically powerful bosses. The robber barons, as the most famous and unscrupulous of these tycoons were known, made vast fortunes not only because of ingenuity in introducing new technologies but also from consolidation with rival businesses. Political connections were also important in the quest to dominate their sectors.”

This is all the same shades of the late 20th century and now.

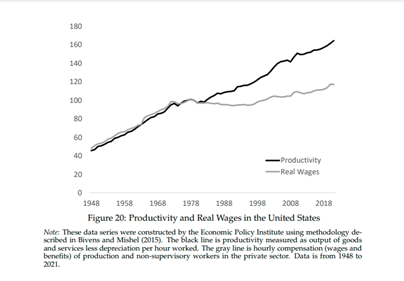

The book considers what can be done to ensure that the gains from the productivity ‘bandwagon’ of modern technology like robots, automation and AI can be spread among the many and not just garnered by the few.

Acemoglu and Johnson reckon that “technology advancements are usually seen by managers with business-school educations as opportunities to reduce wages and cut labor costs, because of the lingering influence of the Friedman doctrine—the idea that the only purpose and responsibility of business is to make profits.” This is naïve – surely capitalist businesses’ main aim is to make profits – that’s the point. It is not the ideology of Friedman that drives this, but the necessary drive for profits delivers the ideology of Friedman.

As the authors point out, contradictions arise under a mode of production for profit: “The problem is an unbalanced portfolio of innovations that excessively prioritize automation and surveillance, failing to create new tasks and opportunities for workers. Redirecting technology need not involve the blocking of automation or banning data collection; it can instead encourage the development of technologies that complement and help human capabilities.” But under capitalism, it does not do so.

How can we overcome this contradiction? The authors fall back on the usual ‘policy levers’ of taxation and subsidies to research; regulation; the breaking up of the big tech monopolies; and stronger trade unions. All these measures in one form or another have failed to achieve the spread of the gains of technology in the past and would for the current innovations – assuming they were even implemented.

The authors studiously avoid the obvious policy conclusion that if most of the gains from technology go to those with the power, then to spread those gains, technology needs to be owned and controlled not by tech oligarchs but by the many through common ownership. It won’t be enough just trying to regulate Elon Musk, or tax him more and insist that he allows trade unions. All these measures, if effective, might help but they would not end the power of capital over technology.

The authors do reject firmly the solution of universal basic income (UBI) as a form of compensation for technological unemployment. “UBI is not ideal for bolstering the social safety net, however, because it transfers resources not just to those who need them but to everybody. In contrast, many of the programs that have formed the basis of twentieth century welfare states around the world target transfers, including health spending and redistribution, to those in need. Because of this lack of targeting, UBI would be more expensive and less effective than the alternative proposals.”

UBI is also likely the wrong type of solution to our current predicament, especially compared to measures aimed at creating new opportunities for workers. There is considerable evidence suggesting that people are more satisfied and are more engaged with their community when they feel that they are contributing value to society. In studies, people not only report improved psychological well-being when they work, compared to just receiving transfers, but are even willing to forgo a considerable amount of money rather than give up work and accept pure transfers.”

In fact, UBI fully buys into the vision of the business and tech elite that they are the enlightened, talented people who should generously finance the rest. In this way, it pacifies the rest of the population and amplifies the status differences. Put differently, rather than addressing the emerging two-tiered nature of our society, it reaffirms these artificial divisions.

There is more to say with new empirical data on the impact of technology on our lives and I shall return to that in future posts. Meanwhile, what Power and Progress tells us about technology and its impact on our lives, for good or bad, is that whoever has the power gets the progress.

November 21, 2023

AI: open or closed?

The shock sacking of Sam Altman, the founder of OpenAI, by his own board reveals the contradictions emerging in the development of ChatGPT and other ‘generative artificial intelligence’ models driving the AI revolution.

Will AI and these language learning models (LLMs) bring wonderful new benefits to our lives, reducing hours of toil and raising our knowledge to new heights of human endeavour?; or will generative AI lead to the increased domination of humanity by machines and even greater inequality of wealth and income as the owners and controllers of AI become ‘winners take all’ while the rest of humanity is ‘left behind’?

It seems that the OpenAI board sacked their ‘guru’ leader Altman because he had ‘conflicts of interest’ ie Altman wanted to turn OpenAI into a huge money-making operation backed by big business (Microsoft is the current financial backer), while the rest of the board continued to see OpenAI as a non-profit operation aiming to spread the benefits of AI to all with proper safeguards on privacy, supervision and control.

The original aim of OpenAI was as a non-profit venture created to benefit humanity, not shareholders. But it seems that the carrot of huge profits was driving Altman to change that aim. Even before, Altman had built a separate AI chip business that made him rich. And under his direction, OpenAI had developed a ‘for-profit’ business arm, enabling the company to attract outside investment and commercialise its services.

As the FT put it: “this hybrid structure created tensions between the two “tribes” at OpenAI, as Altman called them. The safety tribe, led by chief scientist and board member Ilya Sutskever, argued that OpenAI must stick to its founding purpose and only roll out AI carefully. The commercial tribe seemed dazzled by the possibilities unleashed by ChatGPT’s success and wanted to accelerate (ie make money). The safety tribe appeared to have won out for now. “

Altman is not a scientist, but it seems he is a great ideas man, an entrepreneur in the Bill Gates tradition (with Microsoft). Under Altman, OpenAI has been transformed in eight years from a non-profit research outfit into a company reportedly generating $1bn of annual revenue. Customers range from Morgan Stanley to Estée Lauder, Carlyle and PwC.

The success has made Altman the de facto ambassador for the AI industry, despite his lack of a scientific background. Earlier this year, he embarked on a global tour, meeting world leaders, start-ups and regulators in multiple countries. Altman spoke at the Apec Asia-Pacific regional summit in San Francisco just a day before he was sacked.

Altman apparently has “a ferocious ambition and ability to corral support”. He has been described as “deeply, deeply competitive” and a “mastermind”, with one acquaintance saying there is no one better at knowing how to amass power. As a result, he has a ‘cult’ following among his 700-plus employees most of whom signed a letter demanding his re-instatement and the resignation of the safety tribe on the board.

OpenAI has lost half a billion dollars in developing ChatGPT, so it was about to launch a sale of shares worth $86bn before the split on the board. That would have continued the non-profit approach. Now with Altman and others joining Microsoft as employees, it seems that the OpenAI may be swallowed up by Microsoft for a pittance and so end the company’s ‘non-profit’ mission.

What all this shows is that those who think that the AI revolution and information technology will be developed by capitalist companies for the benefit of all are being deluded. Profit comes first and last – whatever the impact on safety, security and jobs that AI technology has on humanity over the next few decades.

Some fear that AI will become ‘God-like’ ie a superintelligence developing autonomously, without human supervision and eventually controlling humanity. So far, AI and LLMs do not exhibit such ‘superintelligence’ and, as I have argued in previous posts, cannot replace the imaginative power of human thinking. But they can hugely increase productivity, lower hours of toil and develop new and better ways of solving problems if put to social use.

What is clear is that AI development should not be in the hands of ‘ambitious’ entrepreneurs like Altman or controlled by the mega tech giants like Microsoft. What is needed is an international, non-commercial research institute akin to Cern in nuclear physics. If anything requires public ownership and democratic control in the 21st century, it is AI.

November 18, 2023

HM 2023: value, profit, technology and value again

It’s been a week since the end of Historical Materialism conference in London and I have finally got round to doing my regular review of the proceedings. For those who don’t know, the HM conference brings together academics and students to present papers and discuss not just economics but all aspects of capitalist society – from a broadly Marxist viewpoint. This year, apparently up to 800 attended, with many papers presented and several plenaries. Obviously, I cannot cover all the papers presented and even more obviously that means I shall concentrate on the papers and discussions around Marxist economics.

So let’s start with my own presentation. This was a session on the themes and arguments presented in our latest book by myself and Guglielmo Carchedi, entitled Capitalism in the 21st century – through the prism of value.

The main approach of the book is to use Marx’s value theory to try and explain the main developments in global capitalism in the 23 years so far of this century. The chapters of the book follow some key themes: the degradation of nature, global warming and the impact of pandemics; changes in the role of money and credit, the return of inflation and a critique of new theories; what causes regular and recurring crises in capitalist accumulation – already two of the greatest slumps in capitalist history: 2008-9 and 2020; the economics of modern imperialism; the rise of mental labour, robots and AI; and last but not least, the features of transitional economies going from capitalism to socialism.

The book’s thread is based on what Marx called the “collision between production for profit on the one hand and the creation of wealth for the producers and their communities on the other.” We show the high correlation between the drive for profit by capital globally and the environmental destruction of the planet; and how it is the periodic fall in profitability that drives economic crises. We argue that imperialism is no longer defined as the direct military occupation and political control of a weaker country by the imperialist nations. Now imperialism operates mainly through trade and investment and the extraction of value (profit) in capitalist operations from the periphery to the core imperialist bloc – a bloc that has not changed since Lenin identified it in 1915. The new challenge to capital and labour in the 21st century is the rise of robots and more specifically, automation of work and the development of artificial intelligence – will AI replace human labour and even surpass human intelligence? In our final chapter, we discuss the class nature of the countries where capitalist power was overthrown, like the Soviet Union and China. Are these ‘socialist states’ or were they always capitalist, or if not, are they capitalist now?

There were two discussants on the book panel: the well-known Seongjin Jeong from Gyeongsang National University, South Korea, and Raquel Varela, a top Marxist labour historian from Portugal. While both panellists praised the book, both had significant criticisms.

SJ was pleased that we did not swallow the idea of capitalist stages ie. ‘monopoly capitalism’ or ‘state monopoly capitalism’, which have become popular again recently, but instead stuck to using value theory to explain changes in capitalism, as such. But SJ did not agree with the view in our book that China was not capitalist, let alone imperialist. RV also argued that China was capitalist – yes, the state played a big role, but so did it play such a role in countries like Japan and Korea in their development. Indeed, China’s economy was similar in some ways to Nazi Germany in fusing the state with big business to exploit wage labour. I do not agree that a fascist state has the same class character or economic foundation as the modern Chinese state, but there is no space to develop that argument here.

This critique was echoed from the floor in discussion. Indeed, I suspect that I was the only one in the session that did not accept that China was capitalist (or state capitalist?). My defence of that position has been outlined in many posts and papers. Simply, yes the law of value still operates in China, capitalists operate in China; workers are exploited and wage labour exists. But something happened in 1949: capitalists and landlords were expropriated and a new state machine was installed. Yes, there is no workers democracy in China; it’s a one-party dictatorship (says Biden!).

But when we consider the economic foundation of the Chinese economy, the size of the state sector is immense compared to any other (major) economy in the world; and the commanding heights of the economy are in the hands of the state and CPC. Capitalists operate in China and there are billionaires,but they do not control the state machine or its policies, and instead often they must do the state’s bidding.

And here is the theoretical rub: if China is capitalist like any other capitalist state, how can we explain China’s phenomenal economic growth and rise in prosperity? I thought capitalism could no longer develop the productive forces for the world’s periphery – are they not held back by imperialism and the contradictions of capitalist production? No other peripheral capitalist economy, not even India, has grown like China – none of the other BRICS have done so. So does China’s (capitalist?) success mean that we must revise Marxist theory on capitalism; or is China not capitalist after all?

Since 1949, there has been no slump in output or investment in China (on the contrary); while the major capitalist economies suffered slumps at regular intervals and the peripheral economies are in continual crisis. China did not have a contraction in the Great Recession or in the pandemic slump despite then applying a severe and long-lasting lockdown. So there is something different about China – in our view, it is the state-led economy with planned investment that curbs the operation of the law of value and the anarchic role of the market forces within the country and outside. For us, China is not socialist, but nor is it capitalist (yet) – it is neither black nor white, but in a transition – but a transitional economy that cannot proceed to socialism, surrounded as it is by imperialism and not having workers’ democratic control. So any transition cannot be resolved.

Does it matter what it is? Yes, because China’s economic rise is an indicator of the power of collective ownership and planning over the capitalist production system and the law of value (as expressed in the other BRICS), even with the distortions of the ‘Communist’ rule.

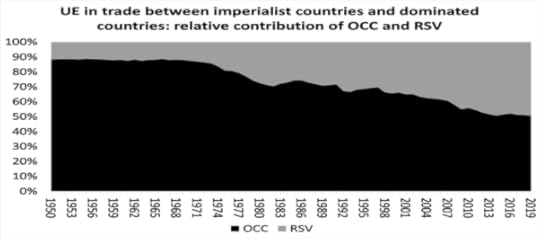

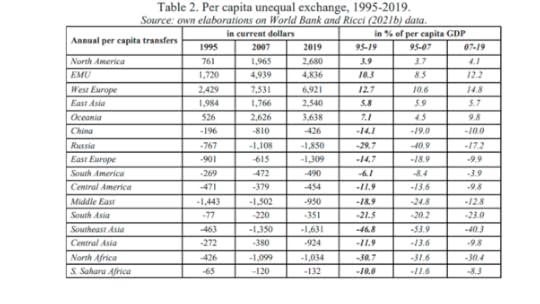

That’s a long response on this issue. So let’s move onto other criticisms of the book. Several speakers attacked the chapter on imperialism; first, because the book rejected the theory that the main cause of surplus value transfer from the peripheral counties to the imperialist bloc was through ‘super-exploitation’ ie where wages levels in poor countries are forced below even the basic needs of people ie below the value of the labour power. Our research on the economics of modern imperialism does not rule out super-exploitation, but we reckon value transfer takes place mainly because of the technological superiority of the imperialist companies over the periphery, not because of low wages. Through the process of what Marx called ‘unequal exchange’ in trade, the imperialist countries can gain extra surplus value from the periphery. So imperialist exploitation is not because wages are forced lower in the poor countries.

Our methods showing this process came under severe criticism on the grounds that using GDP and official money-based stats was full of holes, as it was not based on Marxist labour value measures ie labour hours. In our book, we argue that the official stats, although only approximate, can still show the general trends in profitability and labour value transfers. We can confirm this from those studies that are based on labour input-output tables. They show similar trends as our more dynamic study. Moreover, all show that the imperialist bloc extracts significant surplus value through trade from China and Russia – and in that sense, they are not imperialist countries.

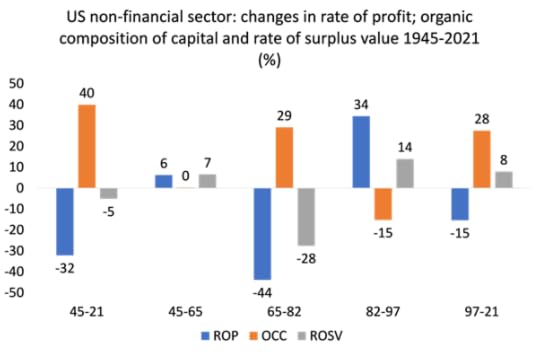

Our book argues that the underlying cause of crises comes from Marx’s law on the movement of profits, not from underconsumption, disproportion or financial instability – or some eclectic mix of all these alternatives. But our calculations showing the profitability of capital falling over time have been challenged at regular intervals. One of the latest challenges comes from Bill Jefferies at SOAS who published a paper last year arguing that using the official stats from the BEA for US profitability was bogus because the BEA like other official sources makes up its capital stock figures from false neoclassical assumptions, not from reality. At the session, BJ made these points, reckoning that if other proper measures are used, then the US rate of profit has been rising not falling. I think we can refute BJ’s assertions (and here I attach an unpublished response to BJ’s arguments).

BJ is just one challenger to the data on the US rate of profit. Recently, Jacobin editor Seth Ackerman delivered what he considers a decisive death blow to the law of the falling rate of profit with his adjustment of the US data. Again, I think I have answered this attempt in my recent reply in the Spectre journal.

Let me just add a recent study by Sergio Camera of the University of Mexico. He found “a prolonged stagnation” of the US rate of profit in the 21st century. The general rate of profit was 19.3% in the ‘golden age’ of US supremacy in the 1950s and 1960s; but then fell to an average 15.4% in the 1970s; the neoliberal recovery (coinciding with a new globalisation wave), pushed that rate back up to 16.2% in the 1990s. But in the two decades of this century the average rate dropped to just 14.3% – an historic low.

Phew! That’s my session over. What was going on elsewhere? Well, interestingly there were two other papers on profitability presented that tend to confirm Marx’s law of the rate of profit. In an excellent paper, Geoff McCormack from New Brunswick, analysed the changes in Canada’s economy since the 1990s. His result showed clearly a general decline in profitability and when the mass of profit also fell, Canada had a slump. Unfortunately, I cannot insert here McCormack’s explicitly revealing graphs.

In another session, Tomas Rotta from Goldsmiths, London and Rishabh Kumar from the University of Massachusetts presented a paper entitled, Was Marx right?. In the paper, they use labour input-output tables (no neoclassical stats or GDP here!) and found that Marx’s law was confirmed for at least the 21st century in the US and in the other major economies. Here are their conclusions: “If there is a tendency for the OCC (organic composition of capital) to rise over time then there should also be a tendency for the rate of exploitation to rise, otherwise the average profit rate will tend to decrease. Evidence at the global level from 2000 to 2014: OCC and the exploitation rate rise over time, but the average profit rate falls. The 2007-2008 crisis had a major negative impact: profits OCC, exploitation rate, and profit rate all fall with the level of development.”

The big issue of 21st century capitalism apart from global warming is the advent of AI and ‘generalised intelligence’, as expressed through language learning machines (LLMs) like ChatGPT and Bard. There was an excellent session on the tech ‘monopolies’ and how they would prosper over the next few decades. In his presentation, Harry Halpin from the American University of Beirut (and a top ‘techi’, I am told), quickly dismissed the nonsense promoted by the likes of Yanis Varoufakis that ‘ordinary capitalism’ is dead and been taken over by ‘feudal monopolies’ like the ‘famous seven’ media and tech monsters.

Halpin reckoned that the tech companies faced the same contradictions of other capitalist companies – over time, their profitability would fall and push them into crisis. Their bloated stock prices bore little relation to their underlying profitability and would prove to be so much fiction. As AI reduced marginal costs of production towards zero, it would lead to high average costs in infrastructure and facilities that had to be paid for by ever great profits. That wasn’t going to be found in the sectors each tech was in and so they would be forced to compete with each other and look for ‘unproductive’ but lucrative business such as military and corporate surveillance where government funding would be available.

In the same session. Jonas Valente from the University of Oxford) reckoned that digital platforms owned and controlled by companies in the global north outsourced the work of ‘intellectual’ (mental labour) to workers in the global south at low pay rates and so were able to profit. This “platform-mediated work” encompassed millions of workers from hundreds of countries in charge of crucial tasks in the development cycle.

There was a session on a new book by Matteo Pasquinelli called In the eye of the master, which I think argued that, whereas in the past, labour was supervised and controlled by the owners and their agents (the masters), now supervision will be increasingly automated. So instead of AI and automation being used collectively by us all, machines will rule our lives for the benefit of the master.

Another session on a new book, entitled, The rise and fall of American Finance by Stephen Maher and Scott Aquanno, was much easier to understand – and disagree with. There were many well-known panellists in this session to discuss the book. The authors argue that the ‘financialisation’ of capitalism since the 1980s has not weakened the mode of production but changed and strengthened its ability to exploit with the support of “an increasingly authoritarian state.” The authors claimed that they were arguing differently from “strict financialist theorists” by not claiming “a qualitatively new phase of capitalist development is emerging” but just the same interlocking of finance, industry and the state that has always existed in capitalism.

If so, I am not sure what new thoughts the book is offering. The author’s policy conclusions were also vague; namely that “reducing economic inequality and bringing investment in “Good Jobs” back to the United States requires challenging the competitive logic of global financial integration with state-imposed barriers on the movement of investment worldwide.” Or to be clearer: “establishing a greater public role in determining the allocation of investment”. That seems somewhat feebly short of taking over the banks and financial institutions and the strategic sectors of industry like the ‘feudal tech monopolies’.

I have left out a lot of other interesting sessions: on ecological unequal exchange between the imperialist bloc and the periphery ie. the extraction and transfer of natural resources. And then there were sessions on ‘state capitalism’ and super-exploitation (see above). And then there was the announcement of this year’s Isaac Deutscher book of the year prize. It went to Heide Gerstenberger with her book, Market and violence: to summarise: Gerstenberger does not contest the thesis that there has been, in many places, a decline in the use of violence in the pursuit of profit; but this has been achieved only by a “combination of energetic social contestation and political intervention” by labour, not by the kindness of capital.

But let me finish this long post with the exhumation of some Marxist theoretical dead bodies. At several sessions, yet again the question of what Marx precisely meant by his value theory was debated. It ain’t easy to summarise what was at issue here. But the basic argument (which has been going on for decades) is between those who reckon Marx said that value is created in production by human labour before the commodities produced are sold in the market; and those who say that Marx reckoned value was only created when it was turned into money on the sale of the commodity in the market. This, in my view, is the basic division, but of course, skilled academics can spin sophistry to make it not so simple and stark.

Let me try to explain. At HM, long standing American Marxist economist, Fred Moseley presented a new book entitled Marx’s theory value in, Chapter one of capital: a critique of Micheal Heinrich’s value form interpretation. That’s a mouthful, but Fred and Michael Henrich debated what was at stake in a well-attended session.

Fred argues that, in his interpretation, Marx saw the commodity as the most elementary form of capitalist production. And the commodity has a dual character in production. There is the use value of the things and services people need and produced by human labour; and then there is value, measured in labour time incorporated in the commodity sold on the market. The commodity needs to have a use for the buyer, but under capitalism, it also must have value to be realised by the seller. It’s an old saying: General Motors is not in business to make vehicles, but to make money. Vehicles have a use value for buyers, so GM makes them, but only if money (profit) is realized in selling. So the commodity, the form that products take under capitalism, has this dual character.

Moseley argues that this dual character exists before any commodity is sold. In contrast, the renowned scholar of Marx’s writings and biographer, Michael Heinrich, who is the main modern proponent of a ‘monetary theory of the commodity’, reckons that Marx did not mean this. The commodity is just one among many commodities and can only possess value once it has been exchanged for other commodities or for the universal commodity, money, on the market. Before that, a product has no value. Heinrich claims that only his interpretation can unite production and circulation and thus create value. Moseley argues that exchange on its own cannot create value; that requires the exertion of human labour in production before exchange.

I struggled with all this counting of how many angels were on the head of the commodity pin. Marx put it this way: “As the commodity is immediate unity of use value and exchange-value, so the process of production, which is the process of the production of a commodity, is the immediate unity of process of labour and process of valorisation.” So it’s the process of production, the exertion of human labour that creates value. As Marx once put it: “Every child knows that any nation that stopped working, not for a year, but let us say, just for a few weeks, would perish. And every child knows, too, that the amounts of products corresponding to the differing amounts of needs demand differing and quantitatively determined amounts of society’s aggregate labour.”

The value-form approach of Heinrich is implicitly a simultaneist approach. Its characteristic feature is the belief that value comes into existence only at the moment of realization on the market. Consequently, production and realisation are collapsed into each other and time is wiped out. But the process of production and circulation (exchange) is not simultaneous, but temporal. At the start of production there are inputs of raw materials and fixed assets from a previous production period. So there is value in the commodity already before exchange. Then production takes place to make a new commodity using human labour. This creates ‘potential’ value, which is realised later (in a modified quantity) when sold.

But why does all this matter? Let’s jump off the end of the commodity pin and stop counting the angels there and consider the point of this debate. For me, it’s about showing the fundamental contradiction in capitalism between production for social need (use-value) and production for profit (exchange value). Units of production (or commodities under capitalism) have that dual character which epitomises the contradiction.

For Marx, money is a representative of value, not value itself. If we think that value is only created when selling the commodity for money and not before, then the labour theory of value is devalued into a monetary theory. Then, as mainstream neoclassical economics argues, we don’t need a labour theory of value at all because the money price will do. Money prices are what mainstream economics looks at, ignoring or dismissing value by human labour power – and therefore the exploitation of labour by capital. It removes the basic contradiction of capitalist production (which by the way, our book tries to develop).

And also it leads to a failure to understand the causes of crises in capitalist production. It is no accident that Heinrich dismisses Marx law of profitability as illogical, ‘indeterminate’ and irrelevant to explaining crises and instead looks excessive credit and financial instability as causes. Heinrich even claims that Marx dropped his law of profitability – although the evidence for that is non-existent. If profits (surplus value) from human labour disappear from any analysis to be replaced by money, then we no longer have a Marxist theory of crisis or any theory of crisis at all.

November 16, 2023

Xi meets Biden

US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping met yesterday during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in San Francisco.

This was the only second face-to-face meeting during the Biden presidency. It seems the aim was to clarify just how close the US and China are to conflict over Taiwan and other security issues, as well as trying to establish some semblance of trade progress after years of US moves to reduce China’s rise in hi tech and other products (EVs) that threaten US hegemony. Indeed, Xi was also meeting US business leaders to try and reassure them that they can invest in China, despite recent moves by the Chinese CP leaders to tighten controls on the capitalist sector.

It does not appear much came out of the meeting apart from agreeing not to attack each other ‘by mistake’. But while the leaders ‘talked turkey’, the economic reality is that US efforts to strangle the Chinese economy are not working. Western ‘experts’ continue their never-ending message that China is close to a debt collapse; China’s property market is imploding; and above all, China’s previous phenomenal growth is now over and the economy since COVID is grinding to a halt and will end up like Japan, stagnating in a sea of debt.

If this were really so, then Biden and American capital would have nothing to worry about – but they do worry and rightly so. Yes, China’s property bubble has burst and some very large private sector property developers are going bust. In previous posts, I have argued that it was a big mistake by the Chinese CP leaders to adopt the Western capitalist model for urban development. Instead of putting housing construction into the public sector to build homes at reasonable rents for the hundreds of millions of Chinese who have moved into the cities to work, the government allowed private developers (with billionaire owners) to do the job and now the result is a classic debt-driven bubble that has burst.

And yes, overall debt in the capitalist sector has rocketed. Now the government will be forced to liquidate many of these developers and/or ‘restructure’ their operations with state money. But this does not mean China is about to have deflationary crash. China’s net debt to GDP ratio (debt burden) is only 12% of the average in the G7 economies. The state holds huge financial assets; so it can easily manage this property slump.

The government has just announced that its new Central Financial Commission will take over from the People’s Bank and the existing financial regulator, the control of China’s financial private sector. The ‘Western experts’ decry this move because they think the market can better allocate investment than the state. “The temptation to intervene in capital and credit allocation, whether arising from risk or management failure, or from political directive, is likely to be elevated,” said perennial China sceptic, George Magnus. He added. “These features do not augur well for China’s financial stability or economic prospects.”

The point is that the Xi leadership no longer trust the Western-educated economists in the People’s Bank to regulate the private sector – the bank is a fortress of neo-classical pro-market economics. The bank’s economists would support Magnus’ approach to free up the finance sector – something so successful in Western economies! But the CP leaders still stop short of bringing these speculative financial and real estate speculators into public ownership (no doubt some leaders have personal links). Until they do, financial speculation will continue to distort the economy much more than any arbitrary policies of the party leaders.

The Chinese economy is not diving into a recession. The IMF has just forecast that China’s real GDP will rise by 5.4% this year – and that’s an upgrade from its previous forecast. The housing market may be struggling, but productive industrial construction is booming. China has already built enough solar panel factories to meet all demand in the world. It has built enough auto factories to make every car sold in China, Europe and the US. By the end of next year, it will have built in just five years as many petrochemical factories that Europe and the rest of Asia have now.

And take hi-speed rail and infrastructure projects. Back in the US, Biden makes much of his infrastructure program after decades of decline and neglect in US transportation facilities. But that’s nothing to the rapid expansion of hi-speed rail and other transport projects that now have linked up the vast expanse of China’s regions. Compare this to the state of infrastructure in the San Francisco area as Xi visits.

Ah, but you see, China’s economy is seriously ‘imbalanced’. There is ‘too much’ investment in such projects and not enough handouts to the people to spend on consumer goods like I-phones or services like tourism and restaurants. China cannot grow any more unless it switches households from saving to spending and investment to consumption. The old state-led investment and export model is dying. China will now end up like Japan, stagnating with near zero growth and a falling population.

I have pointed out the nonsense of this view on several occasions. China’s growth has been based on a high rate of productive investment – at least until the unproductive capitalist property development sector came overloaded with debt.

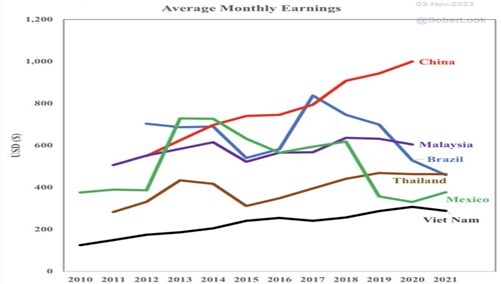

But high investment does not mean low consumption growth – on the contrary, investment leads to more production, more jobs and then more incomes and consumption. China’s supposedly low consumption ratio to GDP compared to the highly successful Western capitalist economies is accompanied by a much faster growth in household spending. Indeed, retail sales rose 7.6% yoy in October – not suggesting an entirely weak consumer. China’s workers may not have any say in what their government does, but nevertheless, their wages are still rising faster than anywhere else in Asia.

.

And those wage rises are not being eaten away by inflation as has happened in the last few years in the rest of the G20 economies. China’s inflation rate is near zero while inflation, despite recent falls, in the US and Europe is several times higher – indeed US workers have seen prices rise by 17% since COVID.

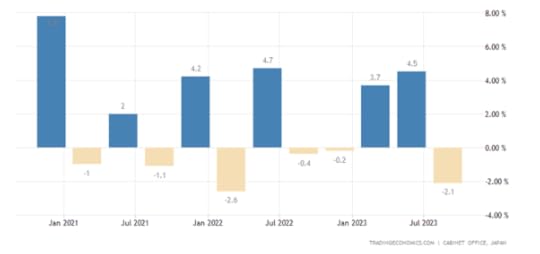

The Western mainstream economists proclaim China’s ‘disappointing’ economic slowdown (real GDP growth 5.4% and forecast 4.5% next year), but they say little about Japan. Japan is dropping into stagnation and even slump. In Q3 2203, real GDP fell 2.1% at an annualised rate (the measure US economists use to bolster the US rate); consumer spending is stagnating and business investment’s decline is accelerating.

Japan: real GDP growth (annualised rate) %

Japan is joining much of the Eurozone, the UK, Canada, Sweden, New Zealand etc in contraction this coming year.

And if Biden is hoping that the upcoming presidential election in Taiwan will lead to a victory for the pro-independence candidate from the Democrat party, then he could be in for a surprise. It seems that the two anti-independence, pro-China parties, the Kuomintang and People’s Party, are planning to run a single candidate for the presidency and current polls show that such a candidate would win. So that could mean a pro-China president in Taiwan next year.

November 12, 2023

From a Sahm recession to global downturn

After a relatively strong US real GDP figure for the third quarter of the year, the consensus is that the US will not have a recession this year or next. Indeed, on the contrary, investment bankers Goldman Sachs, not only forecast some economic growth in 2024 but an acceleration for the US economy and for the major economies.

I threw a little cold water on that forecast in a recent post. And not everybody is as confident about the US economy avoiding recession in the next 12 months. Take the view of William Dudley, former New York Fed chief. He commented in the FT: “My view for two years was that we were going to ave a recession at some point…. I’ve always thought that once the unemployment rate goes up by more than a certain amount, the chances of recession go up dramatically. That’s the key question right now: does the unemployment rate have to rise to 4.25-4.5 per cent for the Fed to achieve their “final mile” on getting inflation back down to 2 per cent? If you think it does, then a hard landing is highly likely.”

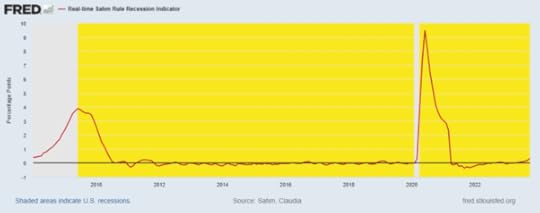

And on that issue, the work of Claudia Sham, another former Fed economist, has gained some prominence. Sahm reckons that if the unemployment rate runs some 0.5% pts above the bottom for three months, it is a very strong indicator of a recession in output. “I have said the whole time that we do not need a recession, but we may get one.” As she put it in the FT: “I developed the Sahm rule in 2019 as a trigger when a recession has started. It’s not a forecast, it’s an indicator. The rule has worked in every single recession since the 1970s and basically everything going back to the second world war — it doesn’t turn on outside of recessions and it doesn’t fail to turn on in a recession. And it shows up early, so it’s highly accurate.” She continued: “the reading on the Sahm Rule in October was 0.3 percentage points and while it has been moving up, particularly in the second half of the year, that level would not yet indicate we are in, or going into, a recession. …. But it is disconcerting — the unemployment rate is going up.”

Even if the US avoids an outright contraction in real GDP in the next few quarters, it is likely that the US will suffer a significant slowdown to almost stagnation next year, with inflation still well above the pre-pandemic average and the Fed’s own target of 2% a year.

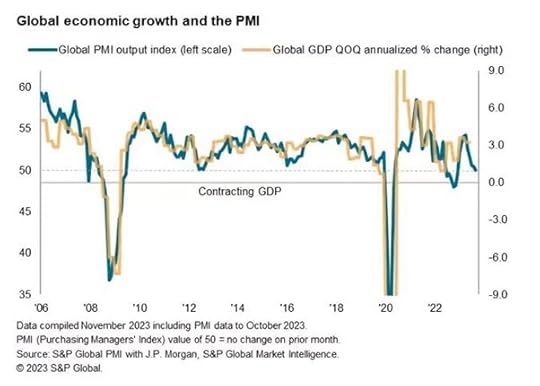

And as for the rest of the major economies, outright recession appears much more likely. Worldwide business activity stalled in October as global PMI hit 50.0. The global PMI is a reliable measure of economic activity in economies – and the 50 mark is the threshold between expansion and contraction. The global PMI has not fallen below 50 since the global financial crisis.

And as shown in my previous post on the US economy, the major developed capitalist economies continued to have a reading below 50 – indicating contraction. Indeed, many advanced capitalist economies are already in recession. The Eurozone economy contracted in Q3. Real GDP fell -0.1%, marking the first contraction since 2020 when the covid-19 pandemic weighed. A ‘technical’ recession looks likely – two consecutive quarterly declines, as Q4 could also show a contraction. Sweden is contracting, Canada is contracting and the latest figure for the UK showed the economy heading into recession. Real GDP was flat in Q3 and Q4 has started very weak. The Bank of England is now forecasting five quarters of zero growth at best. And real GDP growth is still well below pre-GFC growth trends.

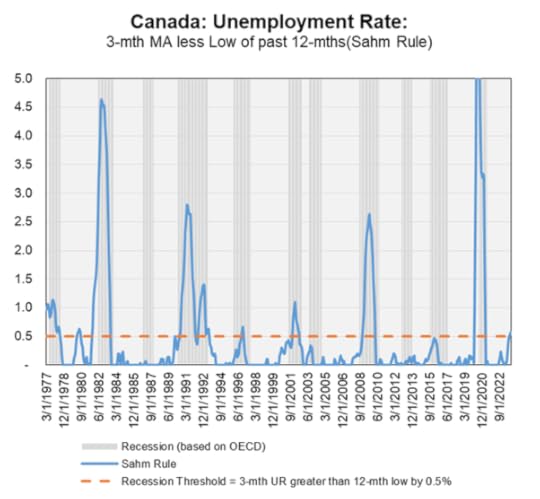

Indeed, Canada has already breached the Sahm rule.

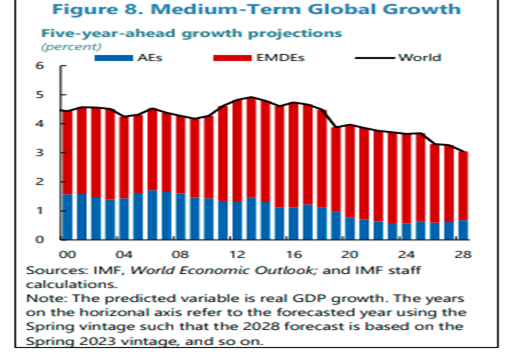

Even if the major economies do not suffer a contraction in output, investment and employment in 2024, the prospects for the rest of this decade are not good. In a report covering the G20 economies (that’s 19 top economies plus the Eurozone), the IMF projects that global growth will slow 3.0 percent in 2023 and 2.9 percent in 2024 from 3.5 percent in 2022 and this includes forecasts for faster growth in China and India next year. The slowdown is particularly pronounced in the European Union where growth is projected to decline from 3.6 percent in 2022 to 0.7 percent this year. Most G-20 emerging market economies other than Brazil, China, and Russia are also expected to experience a slowdown this year.

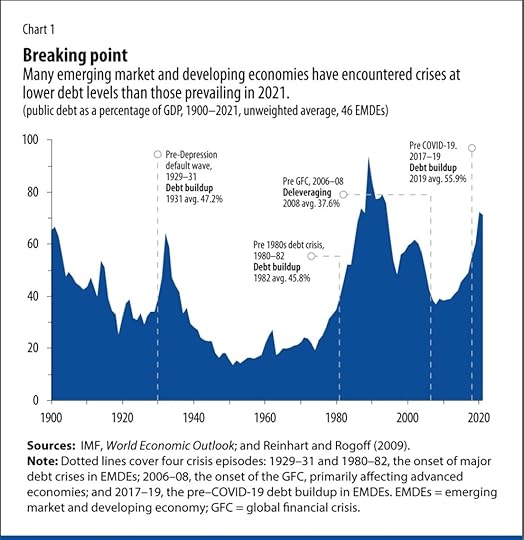

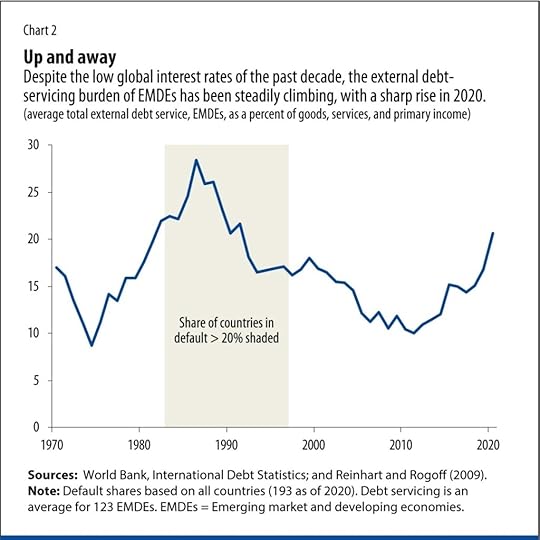

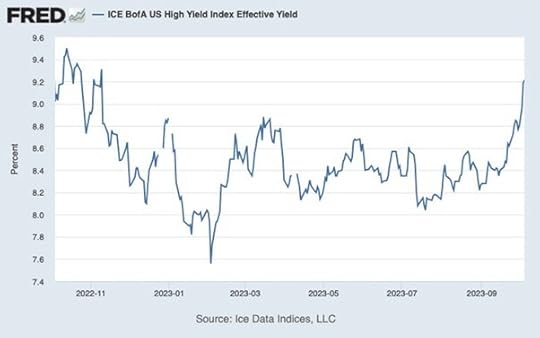

In previous posts, I have already reported on the debt crisis that many so-called emerging market economies are suffering. The IMF reckons that debt servicing costs are likely to rise sharply and with many poor economies rely substantially on foreign currency denominated borrowing, they are vulnerable to a currency crash.

Meanwhile, the World Food Program estimates that about 345 million people will be food insecure in 2023—almost 200 million more than in early 2020. “High energy prices, particularly natural gas, have contributed to higher food prices and have driven an increased reliance on higher-emission fuels, such as coal, setting back the green transition.” (IMF).

The IMF sums it up: “the medium-term outlook for global growth is at its lowest in decades. The IMF’s five-year ahead global growth projections have steadily declined from a peak of 4.9 percent in 2013 to just 3.1 percent in 2023, lowering the pace of convergence in living standards between emerging market and developing economies and advanced economies, while also posing challenges for debt sustainability and investment in the climate transition.”

What’s the problem? Well, the IMF refers to “monetary policy tightening to curb persistent inflation” (rising interest rates), “fiscal consolidation” (cuts in public spending and higher taxes), and the end of what I have called the ‘sugar rush’ in the post-pandemic recovery in 2021 and 2022.

But what’s underlying problem? Well, says the IMF it’s “the slowdown of rapidly growing emerging market economies like China, scarring from the pandemic, weak productivity growth, a slower pace of structural reforms, and the rising threat of geoeconomic fragmentation, while demographic challenges from aging are expected to contribute to a slowdown in labor force participation in advanced economies.”

I’m sure all of these are factors, but they are surface factors. The underlying cause of the slowdown in productivity and world trade, and the increased geopolitical rivalry is to be found in the slowing of productive investment growth in the major economies. What is has been keeping growth up so far has been unproductive investment in finance, real estate and now military spending. Investment in technology, education and manufacturing has dropped away. And the basic reason for that is the stagnating and even downward trend in the global profitability of productive capital in the 23 years of the 21st century.

The IMF reports that “developing economies face large financing needs to meet their development goals and invest in climate action—to the order of $3 trillion in additional annual spending by 2030 for emerging market economies excluding China—but many have limited policy space following multiple shocks.”

The IMF points out that “capital has generally not flowed freely from advanced economies to emerging market and developing economies where returns on capital tend to be relatively higher.” The imperialist bloc of countries have reduced capital exports; instead they are taking capital and profits out of the peripheral economies. “Despite some reversal after the GFC, uphill capital flows from emerging market and developing economies to advanced economies reemerged in 2022. Going forward, a prolonged tightening of global financial conditions could trigger broad-based capital outflows from vulnerable emerging market and developing economies.”

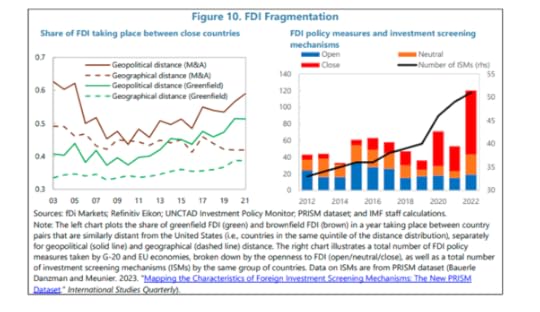

‘Friend-shoring’ is the name of game, where companies in the so-called global north switch their investment to “countries that share similar geopolitical views” and away from their supposed enemies like China or Russia or ‘non-aligned’ countries.

Capitalism is failing to deliver on its own objectives, namely faster real output growth, higher investment and above all higher profitability of capital. What can be done? The IMF wants ‘structural reforms’. What are these ‘supply-side’ measures? The IMF wants more ‘labor market flexibility. That might mean more women in jobs but it also means weaker trade unions and an end to protective labour laws and rights ie more exploitation.

The IMF wants “fiscal consolidation” That means higher taxes and lower public spending in order to restore ‘debt sustainability’. It wants more clean energy investment “to deliver on climate commitments”. And “increased multilateral cooperation to help address global challenges and prevent further fragmentation.” But these proposals are wild utopian hopes, given the increased spending on fossil fuel production and rising global temperatures. Multilateral cooperation on ‘debt resolution’ for indebted poor countries is not happening, let alone any cancelling of the ‘odious debt’ forced on such countries.

On the contrary, the IMF is still enamoured of what it calls ‘financial globalization’ which “by facilitating greater cross-border capital flows—has contributed to economic development around the world.” This is not only because foreign investment might help poor countries (and we have seen that this is dubious) but also “capital flows may bring indirect benefits by imposing discipline on macroeconomic policies” – in other words it can be used as blackmail to stop national governments introducing measures to stop ‘financial globalisation’.

Indeed, the IMF admits that “despite the crucial benefits of financial globalization, it also exposes countries to certain risks, particularly in times of crisis. Capital flows can fuel the buildup of systemic vulnerabilities in the form of currency and maturity mismatches. Excessive capital flow volatility and vulnerability to sudden stops and reversals can be particularly severe in countries with weak monetary policy credibility. Greater integration into global financial markets also exposes an economy to spillovers from the global financial cycle, which can dampen monetary policy effectiveness, as policymakers lose control over domestic interest rates.” Exactly! Ask Africa, Latin America and South Asia.

Another ‘reform’ advocated by the IMF to boost capitalist growth is to reduce “inefficiencies associated with state-owned enterprises” (ie privatise); “lower regulatory barriers to entry” (less regulation and trade barriers) and increase “access to finance to foster business dynamism” (let the banks rule).

The climate change reform for the IMF is carbon pricing, a market solution to reduce emissions that so far has been a total failure. The IMF hopes for “careful international coordination, and consideration of international spillovers.” But don’t hold your breath for anything coming out of the upcoming COP28 international climate conference.

November 9, 2023

Visions of inequality

In this next of a series of reviews of some important books published this year, I look at Branco Milanovic’s Visions of Inequality.

Branco Milanovic, former senior economist at the World Bank, has written yet another intriguing book on global inequality. Over the years, Milanovic has established his reputation as the expert on global inequality through papers and books that accumulate detailed and revealing statistics on the inequality of wealth and income within nations, between nations; and between rich individuals in the West and poor people in the periphery; also showing the changing trends in inequality over the last century or more.

But Visions of Inequality takes a different approach from the stats. Milanovic identifies those authors that he considers have the most important explanations of why inequality of wealth and income is so great between humans. As Milanovic puts it: “The objective of this book is to trace the evolution of thinking about economic inequality over the past two centuries, based on the works of some influential economists whose writings can be interpreted to deal, directly or indirectly, with income distribution and income inequality. They are François Quesnay, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx, Vilfredo Pareto, Simon Kuznets, and a group of economists from the second half of the twentieth century (the latter collectively influential even as they individually lack the iconic status of the prior six).” The latter includes Thomas Piketty.

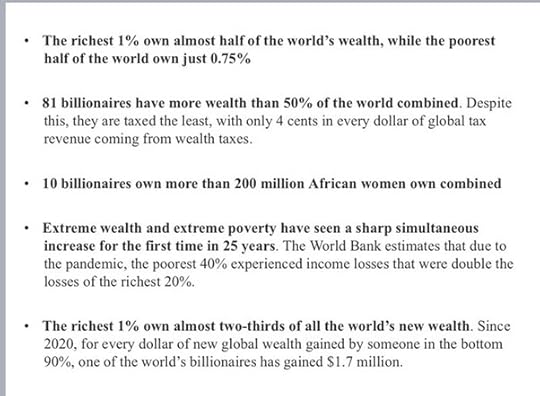

Before we consider Milanovic’s discussion of these economists views on inequality, let us remind ourselves of just how unequal the world is in terms of wealth in 2023.

And in the richest large country in the world, the latest data show that the top 0.01% of American households have 5.5% of all personal wealth; the top 0.01% have 14.7%, the top 1% have staggering 35.1% and the top 10% have 73.4%, according to the latest Fed survey on consumer finances.

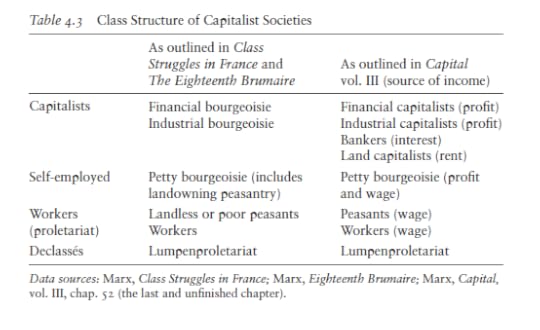

It is not possible to go through all the ‘visions’ of inequality described by Milanovic, so unsurprisingly, I shall concentrate on Milanovic’s analysis of Marx on inequality. Milanovic reckons that Marx’s “theory of value can be treated entirely distinctly (that is, left out) from the discussion of forces that, according to Marx, affect income distribution between classes.” That is an interesting observation that I am not sure is correct – as I shall attempt to explain below.

Milanovic goes on that “it should be noted that Marx was generally uninterested in questions of inequality in the way that we pose them now. His view, shared by most Marxists, was that unless the background institutions of capitalism—namely, private ownership of means of production and hired labor— were swept away, any political struggles to reduce inequality could at best lead to reformism, trade unionism, and what Lenin later called “opportunism.” Inequality was thus a derivative, secondary issue, barely addressed in Marx’s writings.”

Again, I am not sure that it is correct that Marx was not interested in inequality, although Milanovic correctly identifies that Marx saw inequality and poverty under capitalism as the result of the private ownership of the means of production and the exploitation of labour power, not due to regressive taxation, low wages or monopoly, as such. Milanovic points out that “descriptions of poverty and inequality fill the pages of Capital, especially its first volume. But they are there to show the reality of capitalist society and the need to end the system of wage-labor. They are not there to advocate reductions of inequality and poverty within the existing system.”

Milanovic makes the currently usual view that Marx’s view of capitalism and thus inequality was ‘unfinished’. He accepts that “some important parts (like the discussion of the tendency of the profit rate to fall) are clearly unfinished.” For Milanovic, Marx wrote in a chaotic way, but even so there were “true diamonds in the rough”. And Marx was no dry theorist. Despite the dearth of empirical data in the mid-19th century, he diligently tried to dig up evidence to back his vision of capitalism. “Marx’s use of data and facts marked a dramatic improvement upon Ricardo and Smith. Pareto would take this to a new level because of his access to the fiscal data on income distribution. …Marx, too, cited fiscal data on English and Irish income distributions—the same type of data that three decades later would provide the empirical core of Pareto’s claims.”

Milanovic provides the reader with an interesting review of Marx’s own place in the distribution of wealth. He was born into the top 5% tier of households in Trier, now in west Germany. Of course, as it panned out for Marx and his family in their refugee travels across Europe to England, that wealthy start was not to be sustained during his life – at least not until near the end.

Milanovic reveals just how wealth inequality in the UK increased throughout most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries before peaking just on the eve of the First World War. At the time that Marx was writing Capital, wealth inequality in the UK was not only rising but exceptionally high: the top one percent of wealth-holders owned around 60 percent of the country’s wealth. As the data above shows, the top 1% in the US now have about 35%.

Income inequality was very high too and most likely increasing until around the 1870s. At the time of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776), the average income of capitalists was eleven times and that of landlords thirty-three times greater than the average income of workers. At the time of Capital—about a century later— the workers’ position was even worse vis-à-vis the capitalists (who now made fifteen times more).

Back in the 1840s, Engels wrote about the low real wages experienced by labour during the industrial revolution in his seminal work, the Condition of the Working Class in England (1845). But after what has been called ‘Engel’s pause’, real wages started to rise, partly due to workers obtaining a share of increased productivity of labour, but also from transfers of profits from the huge colonial empires that England had accrued by the mid-19th century.

But Marx noted that there was “simultaneously an increase in the real wage and a declining labor share.” This, I will argue below, is key to Marx’s view on inequality. Milanovic explains that Marx considered that any distribution of the means of consumption was only a consequence of the distribution of the conditions of production. And the latter was a feature of the mode of production. The capitalist mode of production rests on the fact that the material conditions of production are in the hands of non-workers in the form of property in capital and land, while the masses are only owners of their personal condition of production, of labor power. Thus, the distribution of income and wealth cannot be changed in any material way until the system is changed. The issue is the abolition of classes, not marginal alteration of income inequality. “To clamor for equal or even equitable remuneration on the basis of the wages system,” Marx writes, “is the same as to clamor for freedom on the basis of the slavery system.”

This is where I find it strange for Milanovic to claim (as above) that Marx’s theory of value has no connection to his explanation of inequality. Indeed, Milanovic says that Marx’s theory of exploitation is of commodity “exchange that is based fully on the law of value: the workers are not treated unfairly, nor are they paid less than the value of their labor-power. Exploitation comes from this specific feature of labor: its ability to produce value greater than the value of goods and services expended in that effort and therefore necessary to compensate it. From the theory of exploitation comes also the conclusion that profit is the surplus value in another guise.”

From Marx’s value theory, we can derive a theory of classes in capitalist society. And Milanovic outlines its features from Marx’s works.

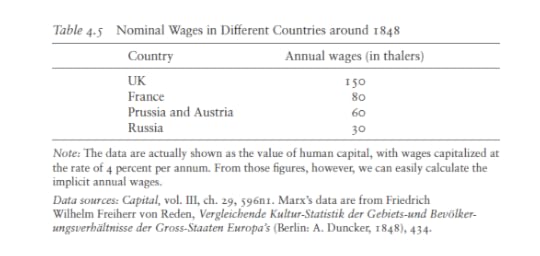

Also, what flows from Marx’s value theory is that wage differences among countries are generated by the rise in the technical composition of capital and productivity differentials. Milanovic: “the more productive is one country relative to another in the world market, the higher will be its wages, compared to another.” In a note in Capital volume III, Marx shows the difference in the nominal wages between the UK, France, Prussia, Austria, and Russia.

The ratio of nominal wages in the UK is at the top, with Russia at the bottom, at 5 to 1, matching the pecking order in technical development.

Marx argues that the very concept of what is the minimal acceptable wage is historical; “indeed, it would be hard to imagine Marx, for whom all economic categories are historical, not applying the same logic to labor-power.” (Milanovic). As Marx says in volume III of Capital: “The actual value of labour-power diverges from the physical minimum; it differs according to climate and the level of social development; it depends not only on the physical needs but also on historically-developed social needs.” I think this observation is important in the debate about whether the exploitation of the Global South by the rich imperialist bloc is mainly due to very low wages in the former rather than mainly due to the productive power of the imperialist bloc to grab the lion’s share of profit through international trade and investment.

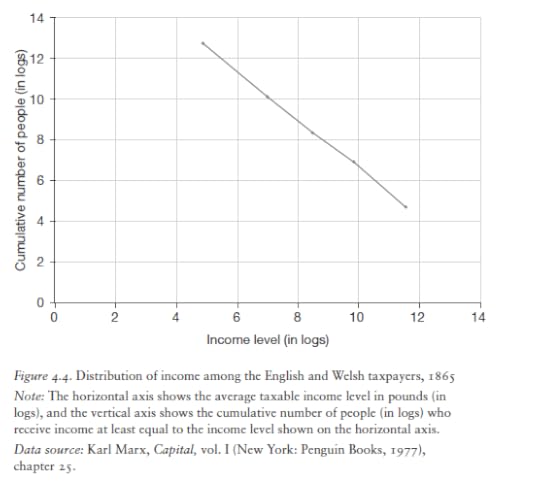

Marx looked for empirical evidence on inequality of income in his time. In Volume One of Capital, he illustrates inequality using the 1865 income tax data from England and Wales. Indeed, Milanovic makes the interesting observation that if Marx had transformed the tax data that he shows in Capital in the same way that Pareto would soon do, he would have obtained a graph showing a Pareto coefficient of 1.2, which is implies a very thick right-end tail of income distribution or a very high ‘Gini coefficient’ (in modern terms).

On inequality, Milanovic refers to Marx’s view that it is a relative concept: “A house may be large or small; as long as the neighboring houses are likewise small, it satisfies all social requirement for a residence. But let there arise next to the little house a palace, and the little house shrinks to a hut. The little house now makes it clear that its inmate has no social position at all to maintain, or but a very insignificant one.”

And on needs, Marx explains: “Our wants and pleasures have their origin in society; we therefore measure them in relation to society; we do not measure them in relation to the objects which serve for their gratification. Since they are of a social nature, they are of a relative nature.” Most Americans are rich in income or wealth compared to those living in sub-Saharan Africa or India, but that is not the benchmark for Americans – the benchmark is their wealth and income compared to those ruling their country.

Milanovic takes us through Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall in a broadly accurate manner. However, he accepts the distortion of that law propounded by Michael Heinrich and others that the law is ‘indeterminate’. “Heinrich is right to state that the increase in s / v is not a force that counteracts the law”. But Milanovic ‘saves’ the law with various arguments that a rising rate of surplus value will not sufficiently counteract a rising organic composition of capital and “We are thus back to Marx’s original, and crucial, contention that the profit rate will decline with greater capital intensity of production unless the effect of that change is offset by greater exploitation of labor.“

Milanovic picks up a point that many Marxists miss about the law, namely that it is both the explanation of regular and recurring cycles of crises (booms and slumps) and also a secular law indicating the ultimate failure of capitalist production to develop the productive forces for humanity. “It is the joint or rather simultaneous action of the two—the coincidence of the secular low profits and economic crises—that will spell the end of capitalism.”

Milanovic goes into a detailed account of the counteracting forces that deter or slow the fall in the rate profit to be found in Volume 3 of Capital chapter 14. Then he reaches this conclusion. “The tendency of the profit rate to fall must reduce inequality because capitalists (together with landlords who are treated just as a subgroup of capitalists) are the richest class. Clearly, if the top class’s incomes do not rise, or even decline, we may expect an improvement in distribution. This may be true even if there is an increased concentration of capitalists’ incomes and some capitalists become very rich while others go bankrupt and join workers.”

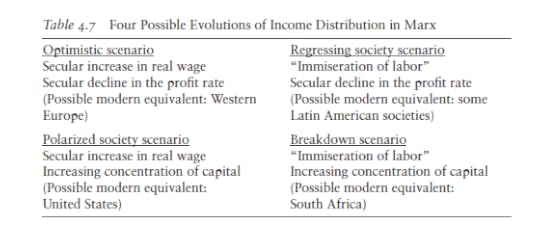

And he presents us with four possible income distributions from Marx’s law of profitability.

These are based on his assertion that a falling rate of profit will mean reduced inequality because real wages rise. But this does not work for me. I think it confuses the rate of surplus value with the rate of profit. Milanovic’s four possibilities arise from his acceptance that Marx’s law is indeterminate and that it is the rate of profit that decides changes in inequality, not the rate of exploitation. Inequality can rise when the rate of profit is falling because the rate of surplus value and the mass of profit are rising. A rising s/v can mean more s for an ever smaller group of capitalists and a rising v for an ever greater group of workers.

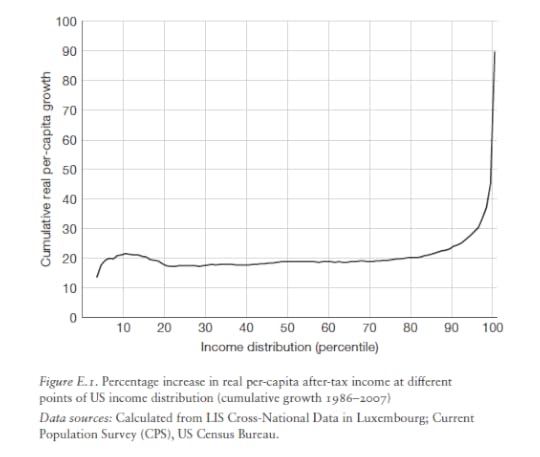

Take the major capitalist economies in the post-war period. Inequality of income and wealth was relatively stable in the Golden Age of 1946-64 when the rate of profit was high and even rising. Inequality rose sharply from the 1980s to the end of the 20th century when the rate of profit was rising mainly due to a rising rate of surplus value a la Milanovic.

But since 2000, the rate of profit has stagnated or fallen but inequality continued to rise along with a rising rate of surplus value – as Milanovic himself shows.

Milanovic also claims that the development of ‘homoploutia’, the supposed trend among the richest income groups to be both labor-income and capital-income rich “by receiving high wages in return for their high-skill labor as well as profits from their ownership of assets” weakens Marx’s theory of exploitation. I don’t think so, particularly as there is strong evidence that the top earners still get their income from capital rather than wages.

The idea that a rising rate of profit is necessary to increase inequality is not Marx’s, but that of Thomas Piketty, in his acclaimed book, Capital in the 21st century. Indeed, as Milanovic contrasts Piketty’s theory of inequality with that of Marx. “Piketty has thus proposed an entirely new and compelling argument that peaceful development of capitalism leads to the breakdown of the system—not because the profit rate crashes to zero and capitalists give up investing (as Marx would have it), but for the very opposite reason that capitalists tend to end up in possession of a society’s entire output and that is a socially unsustainable situation. In Marx’s view, capitalists (as a class) fail because they are not too successful; in Piketty’s view, they fail because they are too successful.”

To sum up, Milanovic says that “we have on offer three theories of income distribution in capitalism. First, there is Marx’s theory, by which increasing concentration of ownership of capital and decreasing rate of profit ultimately lead to the death of capitalism through zero investments. Second, we have Kuznets’s hypothesis of a wave of rising and then decreasing inequality— or as I have argued, successive waves. And third, now, there is Piketty’s theory of unfettered capitalism that, left to its own devices, maintains an unchanged rate of return and sees the top earners’ share of capital income increasing to the point that it threatens to swallow the entire output of the society, and only a political response can prevent such an outcome.”

Given Marx’s compelling explanation of inequality of income and wealth derived from his theory of value and exploitation, Milanovic asks “why do we tend to ignore his views on equality? The answer, I suspect, is that after the cataclysmic failures of socialism and ideological ascendance of neoliberal ideology, we have tacitly accepted the permanence of capitalism. If one has such a view, then indeed it makes sense to refashion Marx as a pro-equality thinker who cared about trade union activity, equal opportunity, higher workers’ wages and the like. In other words, if we have given up on the idea of ending capitalism, we can try to repurpose Marx into the apostle of equality under capitalism. But it may not be easy. After all, if the Left tosses out the idea of transcending capitalism, can it be said to be Left-wing at all?”

Indeed. But I would remind the reader of what Milanovic concluded in another book of his, Capitalism Alone. “Capitalism gets much wrong, but also much right—and it is not going anywhere. Our task is to improve it.” Milanovic does not like capitalism and its inequalities, but to use Margaret Thatcher’s phrase in referring to her neoliberal policies for capitalism: he reckons there is no alternative (TINA). So the aim must be, just as Keynes argued in the 1930s: “to make capitalism more sustainable. And that’s exactly what I think we should do now”.

That’s not Marx’s vision of inequality and how to end it. I put it this way in another paper: “Policies aimed at reducing inequality of income by taxation and regulation, or even by boosting workers’ wages, will not achieve much impact while there is such a high level of inequality of wealth. And when that inequality of wealth stems from the concentration of the means of production and finance in the hands of a few.“

November 6, 2023

Sri Lanka’s debt trap

Last week a US district court granted Sri Lanka’s request for a six-month pause on a creditor lawsuit against the country. Hamilton Reserve Bank holds a big chunk of one of Sri Lanka’s now-defaulted bonds and had been suing it for immediate repayment.

The court decided that there should be a pause in Hamilton’s demand for immediate repayment so that Sri Lanka could arrange a deal with other private sector creditors and bilateral lenders, as well as obtaining new funds from the IMF. The IMF has been unwilling to cough up money as long as it considered Sri Lanka unable to pay back its debt obligations. It is insisting that all creditors agree to a ‘restructuring’ of existing debt before agreeing to new IMF funding (which would also be accompanied by strong ‘conditionalities’ ie fiscal austerity, privatisations etc).

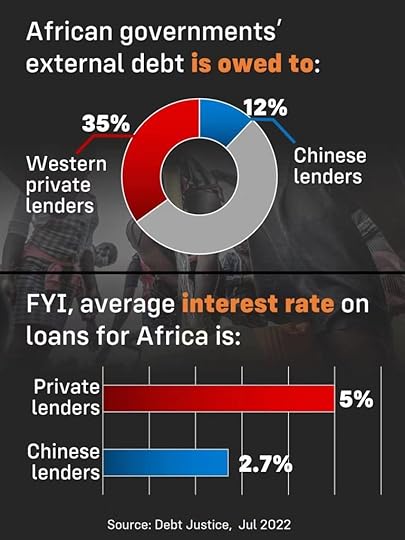

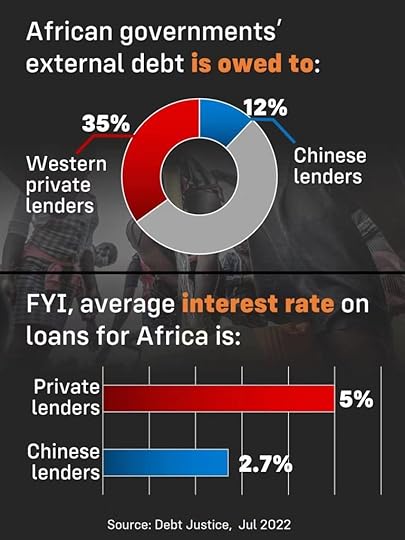

The IMF, World Bank and other Western creditors have claimed that what is holding up a rescheduling is China. In turn, China is refusing to agree to a deal unless all other parties are agreed on the terms, and it does not like the terms currently proposed.

In the case of Sri Lanka and many other poor peripheral countries in serious debt distress, it is regularly argued that they are in a ‘debt trap’ caused by taking loans from China to such an extent that they cannot repay them and then China insists on taking over the country’s assets to meet the bill. Indeed, US President Biden reiterated this charge only this week in a speech claiming that the West was ready to help poor countries expand their infrastructure.

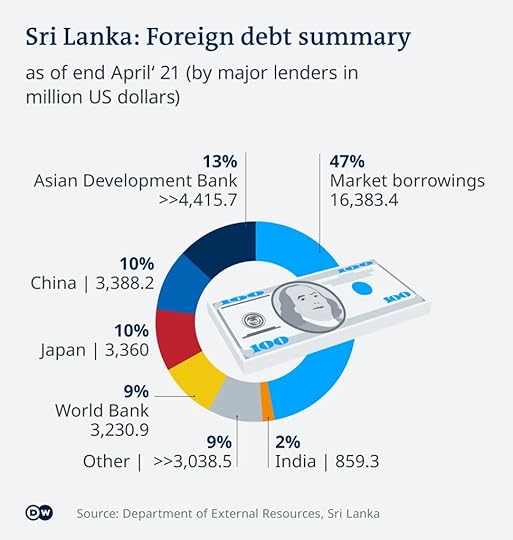

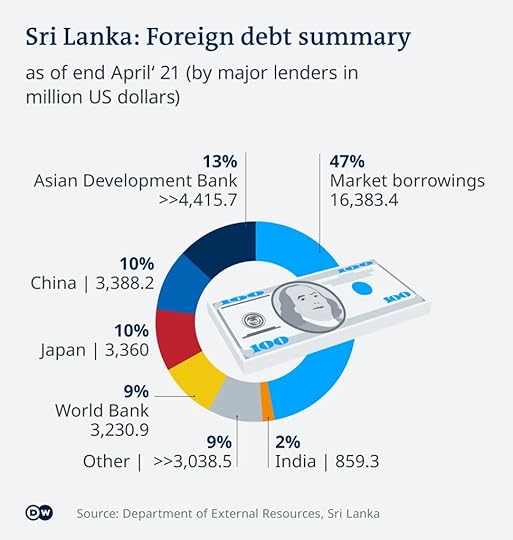

This widespread charge does not hold much water. It leaks badly. First, China is not a particularly large lender to poor countries like Sri Lanka compared to Western creditors and the multi-national agencies.

In the case of Sri Lanka, Japan and the World Bank remained significant lenders at 9-10% share, China has 10% too and the IMF’s proportion has shrunk to just 4%, with the UK and Germany accounting for around 1% each. All these official lenders have been replaced mainly by commercial lenders at nearly 50%.

Second, the rise in Sri Lanka’s debt burden was not the result of China’s ‘imperialist’ debt trap, but was caused by the desperate need of the corrupt and autocratic Sri Lankan government. After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, interest rates fell globally, and Sri Lanka’s government looked to international sovereign bonds to further finance spending. But then COVID-19 hit, ravaging the tourism sector, a major source of income. COVID-19 required increased spending and increased imports of health and other products, exacerbating the trade deficit. Foreign currency reserves dropped by 70 percent, meaning less dollars to purchase essential yet increasingly expensive imports including fuel and commodities. To solve this, the government started to ‘print money’ to cover its deficits. . Inflation rocketed to 60 percent by June 2022. As the right-wing Chatham House study shows, “Sri Lanka’s debt crisis was made, not in China, but in Colombo, and in the international (i.e. Western-dominated) financial markets.”

By 2016, 61 per cent of the government’s sustained budget deficit was financed by foreign borrowing, with total government debt increasing by 52 per cent between 2009 and 2016. Three-quarters of external government debt was owed to private financial institutions, not to foreign governments. Despite ample warnings about the Sri Lankan economy, foreign creditors kept lending, while the government refused to change course for political reasons. This was the real nature of the ‘debt trap’.

That brings us to the Sri Lankan port project, the usual issue raised about China’s supposed ‘debt trap’. China did not propose the port; the project was overwhelmingly driven by the Sri Lankan government with the aim of reducing trade costs. To quote Chatham House, “Sri Lanka’s debt trap was thus primarily created as a result of domestic policy decisions and was facilitated by Western lending and monetary policy, and not by the policies of the Chinese government. China’s aid to Sri Lanka involved facilitating investment, not a debt-for-asset swap. The story of Hambantota Port is, in reality, a narrative of political and economic incompetence, facilitated by lax governance and inadequate risk management on both sides.”

In 2022, Rajapaksa was forced out of office after major popular protests but was only replaced by his close supporter, Ranil Wickremesinghe, who despite agreeing to fiscal measures with the IMF, has failed to get its approval to release funds while the debt rescheduling agreement has not been achieved.

And it is the obscure Hamilton Bank that is opposed to any agreement and instead is demanding full repayment on its holding of Sri Lankan bonds. Hamilton is not waiting patiently for a broader restructuring to take place, but holding out for full repayment once a country has secured debt relief from other creditors.

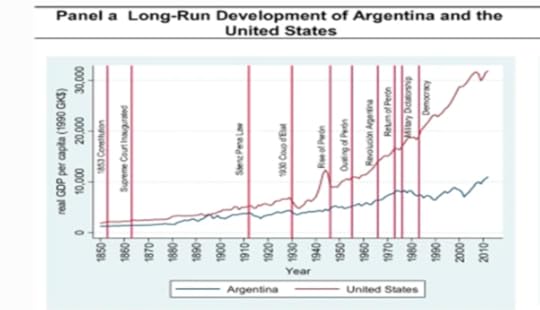

The most infamous and successful example of this strategy was by Paul Singer’s Elliott Management which managed to extract $2.4bn out of Argentina in 2016 from the right-wing Macri government. In paying Elliott off, Macri was then able to get the biggest ever IMF fund deal in history, designed to ensure that government’s position in office for a long time – although that payout was squandered and the Macri government fell. The debt crisis goes on in Argentina.

Hamilton wants to follow in Elliott’s footsteps. In a bank presentation, the bank says “suing a sovereign for non-debt payment can be a justified and lucrative business”. The shareholder is a company called Fintech Holdings based, guess where, Puerto Rico. And behind Fintech is a Benjamin Wey, a Chinese-American, who describes himself as a “philanthropist and global financier”. In 2015, he was arrested for fraud, but charges were eventually dropped in 2017 after a federal judge threw out evidence that prosecutors had obtained in a search of his apartment and office. The New York Post dubbed Wey the “Horndog CEO” after he had to pay $18mn to an intern he had sexually harassed (later reduced to $5.65mn).

Hamilton Bank’s directors are not Wey, but Sir Tony Baldry, a former MP and aide to Margaret Thatcher, who is now chair. (For my sins I was at university with Baldry!). The CEO is Prabhakar Kaza, who is a British Conservative councillor. Hamilton is now registered in the tiny Caribbean island of St Kitts and Nevis. And Hamilton is demanding $250m in bond repayment and interest from the Sri Lankan government. The US court has intervened on behalf of the US government and other creditors to stop Hamilton getting its pound of flesh, at least until there is a general restructuring deal that Hamilton will be forced to go along with.

Even if Hamilton is thwarted and a deal with creditors is reached, Sri Lanka will still be burdened by a huge debt liability that can only be ‘serviced’ by cuts in the already low living standards of 22m Sri Lankans. The IMF has already indicated it will encourage austerity in Sri Lanka – reducing spending and increasing taxes. Sri Lanka did not seek IMF debt relief in the 1990s or early 2000s for that reason. But now it is either Hamilton or the IMF.

Sri Lanka’s debt trap and the vultures

Last week a US district court granted Sri Lanka’s request for a six-month pause on a creditor lawsuit against the country. Hamilton Reserve Bank holds a big chunk of one of Sri Lanka’s now-defaulted bonds and had been suing it for immediate repayment.

The court decided that there should be a pause in Hamilton’s demand for immediate repayment so that Sri Lanka could arrange a deal with other private sector creditors and bilateral lenders, as well as obtaining new funds from the IMF. The IMF has been unwilling to cough up money as long as it considered Sri Lanka unable to pay back its debt obligations. It is insisting that all creditors agree to a ‘restructuring’ of existing debt before agreeing to new IMF funding (which would also be accompanied by strong ‘conditionalities’ ie fiscal austerity, privatisations etc).

The IMF, World Bank and other Western creditors have claimed that what is holding up a rescheduling is China. In turn, China is refusing to agree to a deal unless all other parties are agreed on the terms, and it does not like the terms currently proposed.