Exponent II's Blog, page 276

January 21, 2018

Prayer after a Faith Transition

[image error]I remember sitting in my Community of Congregation for the first time. We were a brand new group, all Mormons and former Mormons. There were a few familiar faces and a bunch of unknown ones. The question “Why am I here?” kept running through my I head. I played new hymns at the piano and we all sang awkwardly. Seth Bryant, my new pastor, stood up and explained the Prayer for Peace, rang a little chime three times, lit a candle (my husband was horrified by this detail when I told him later), and read the Prayer for Peace.

The reading of written prayers was a new experience for me, as few prayers are standardized in the LDS Church. I’ve always been comfortable with spontaneous prayer, but I have learned that a well written and planned prayer can encompass all of the things that you want to communicate in a moment, but often can’t quite execute. When you are in grief or otherwise at a loss for words, written prayers can walk you through comforting language without having to generate that in the moment.

I used to think that if I said a prayer in the morning and a prayer at night, plus three blessings on food, and other needed prayers throughout the day, God would put a marble in a jar of good deeds and obedience on my behalf. I liked to pray, but I also felt that it helped me accumulate eternal reward points. Prayer also had the possibility of causing God to intervene in someone’s life if they needed it. After my faith transition, my concept of God doesn’t include a collection of marble jars measuring each person’s goodness. I believe that God may move us to act, but I don’t think that God stages interventions in our lives in the same way that I did before. All of this leaves the question surrounding the purpose of prayer in an unclear and confusing place. Perhaps the most important part of prayer is the way in which it can inspire us to act, to move us to change, and to create moments when we feel that connection to God.

In thinking about prayer, change of LDS Church leadership, and peace this past week, I wrote this:

A Prayer for Peace

Dear God,

We seek to know you

And feel your presence with us.

In our choices and actions,

May we be drawn toward the work of justice and peace

For as long as we sojourn in this life.

Bless us with moral courage,

And lead us into integrity and authenticity.

Help us to hold ourselves and our communities

Accountable for our words and actions,

And consider the policies, procedures, and laws we support.

Guide us to grace for ourselves and each other

That we may always use the privileges we hold

To the benefit of those without.

Move us to build communities founded on

Mutual respect, inclusion, and equity.

Help us to grow into better ways

Of knowing and doing and moving through this life.

Be with us, O God

And help us to live out your peace.

Amen.

January 20, 2018

Unideal

[image error]

Our new prophet, President Nelson, in a Facebook post clarifying his press conference address, sorted living situations into two categories: unideal and other. Sure, he made up a new word for the one group, and didn’t actually name the other, but I guess that’s because it sounds better than less-than-ideal and normal.

And, sure, it’s not like we’re stuck in one group forever. Living situations change. Those pesky YSA can get married, widowers and divorcées can remarry, childless couples can get pregnant or adopt. Part-member families can convert the holdouts and get sealed properly. Gay people can put their feelings on hold until after the resurrection. President Nelson’s view seems to be that those whose lives are unideal will change and they will become normal. The problem with this is that the changes don’t only move in the more-ideal direction.

For example, the new temple policy states that young women now have the opportunity to offer towels to their newly-baptised peers – a privilege that was recently reserved for endowed women only. The letter from the first presidency doesn’t specifically state so, but I assume unendowed women over 18 are now also extended that privilege.

Those who live unideal lives aren’t specifically recognised in most policy or counsel. We have to fill in the gaps as best we can, all the while having the official narrative make clear that our lives are unsatisfactory to church leaders. Newly called First Counsellor Oaks has explained: “If you feel you are an exception to what I have said as as a general authority, it is my responsibility to preach general principles. When I do, I don’t try to define all the exceptions. […] I only teach the general rules. Whether an exception applies to you is your responsibility. You must work that individually between you and the Lord.” [1]

The saviour did tell us to be perfect, and that we would be sorted like sheep and goats or wheat and tares. He was generally pretty clear that this sorting would happen after everyone was dead, and implied that perfection was measured at the end of our mortal probation by not calling himself perfect until after he’d concluded his, but I can understand the impulse to get started on that work a little early. We all want the millennium to run smoothly and efficiently, and it would be so much easier if everyone could just follow the general rules.

One of the things that drew me so strongly to the scriptures as a child growing up in the unideal category (though my father was in the bishopric, so we seemed to fit the normal case, and follow the general rules) was the fact that every single family was unideal. There’s not a perfect family in the scriptures. (Unless you’re counting those we only see from the outside, and I know for a fact that you can’t assume much from how it looks to outsiders). The scriptures were written for me, in a way that the new First Presidency is saying that this church is not for me — or at least, not for me right now.

And, of course, we can find scripture stories where the families seem normal. We don’t hear the prayers of the mothers of the stripling warriors, we don’t see the actions of the boys as they prepare to leave, we aren’t privy to the exchanges between sisters and fathers and grandparents in those families. We have only one line from the young men, that they had been taught by their mothers, and that line is often used to categorise the entire community as full of other/normal/perfect/ideal families.

If we instead turn to a story of a family where multiple viewpoints are shown, we’ll see that reality can’t follow general rules except for very short periods of time. Look at the relationships between Isaac and Rebekah and Jacob and Esau. None of those people were perfect. We call two of those guys prophets, and the woman went against the wishes of her husband (a prophet), because she listened to the spirit and did as the Lord wanted so that the right son was the next prophet. We recognise that, but don’t call her a prophetess, and we don’t think too long about whether or not their family is ideal (because they’re not, but it’s kind of tricky to suggest that people who lead the church might be capable of belonging in the unideal category).

The truth is that we all belong in the unideal category, unless we flatten normal or ideal until they don’t have anything to do with our hearts. If this church is mostly for people who can follow general rules perfectly, and the general rules mandate young marriage and large families and stay-at-home-mothers, this church is only for a very small minority of people. And many times, those rules are in tension with the first and second great commandments. Above all, we are to love God with all our heart, mind and spirit, and to love our neighbour as ourselves. Whether they’re normal or not.

I pray that our new prophet and his counsellors gain a witness of that truth, and help the church focus on those two most important general rules during their presidency.

[1] “The Dedication of a Lifetime,” May 1, 2005 (link goes to a video clip)

January 19, 2018

When the Questions Aren’t There (Thoughts on Tuesday’s Press Conference)

Photo by Bekah Russom on Unsplash

Two Sundays ago, my 3.5 year old daughter had her first day of primary and my 1.5 year old daughter started nursery.

They both loved it. My oldest chattered the whole ride home about her fun teachers and the silly snowman song she’d learned (we apparently have never given “Once There Was a Snowman” enough air time in our house). And except for one small breakdown when my youngest realized I’d left the room, my baby thought that nursery was a blast: from the singing to the slide (am I right that nursery toys so much cooler than they were when I was a toddler?) to the entire box of raisins she got to munch on as her teacher pointed to pictures of smiling kids and explained that all of us are children of God.

Both that Sunday and the one that followed were mostly easy and carefree mornings for my little Mormon girls. What they didn’t know is that our presence at church that first Sunday in January– all together and for all 3 hours of church for the first time in more than half a year—had come as a result of hours of difficult talks in the car over Christmas break, wherein their pragmatic father and ardent mother had tried their darndest to tackle the pressing questions that busy work schedules had made it easy to put off for so long:

Should we start going back to church as a family?

If so, should we start taking the girls to 2nd and 3rd hours? What would that look like exactly?

And if not, what then?

To answer these questions, a lot of other ones had to be taken out and discussed on that long car ride between my parents’ and his while our girls slept in the backseat: questions about temple ordinances and towel duty, about the beauty of a shared spiritual language, about the 2015 policy that still perplexes and pains us, about a history filled with both the inspiring and the disturbing, about how and where we could improve at reaching out and setting boundaries, and about what kinds of experiences and frameworks we want to give our girls.

Whenever my husband and I have these kinds of especially serious, long, and targeted discussions, we seem to take turns being the one ready to step up the effort and the one who is ready to throw in the towel. This time, I was the one on empty. But as we both did our best to listen and validate and articulate what we were feeling, we both finally agreed that, yes, we’d start going to church again.

Two days later, President Monson passed away.

And 12 days later, my husband and I listened closely as the newly instated First Presidency responded to Peggy Fletcher Stack’s question (starts at about 18:10):

“…What will you do in your presidency to bring women, people of color, and international members into decision-making for the church?”

I’ve felt a deep sense of urgency every time I’ve thought back on this question– and others, like the one posed by the AP’s Brady McCombs’—over the past couple of days.

They’re the kinds of difficult questions that my husband and I, thinking of our daughters, felt compelled to carefully examine in the car just two weeks earlier.

And they’re the kinds of questions that I had desperately hoped to find rooted within the consciousness and consideration of the First Presidency—men who will not only be directing the church that many families like mine are struggling to work out a sustainable connection to, but men who, like all of us, cannot possibly petition heaven for an answer to a question that was never planted in their hearts in the first place.

I readily admit that I have never had to answer tough questions in a highly-scrutinized press conference at any time in my life, let alone at the age of 93. I will also say that as many times as I’ve disagreed with them, I love and sustain those men. Their faces are familiar to me, and each of them at different times throughout my life has provided counsel that has strengthened and comforted me. Their words have mattered to me, and as a mom who wants to know whether and/or how to raise two daughters in this church, their words matter especially to me now.

Here is what I know:

That one day, when my girls ask what it is that they can do and become as daughters of God, that they will deserve better than a pedestalizing response that limits their influence to submissive and supporting roles.

That when they someday question the lack of representation they see in an institution that matters to them, that they will deserve better than to be dismissively told that labels like gender and race don’t matter by a man who has actively used his power to draw and enforce boundaries around those same categorizations.

And that one day, when they approach those in power with the kinds of sacred questions that result from wrestling with the implications of a God who sees people of every race, nation, sexual orientation, ability, and gender as having equal and infinite worth, that my daughters will deserve to sense that those same kinds of questions—and the lives they represent—are continually before their leaders, too.

It’s been a long time since I’ve expected perfection from the church or any human—prophet or not—who belongs to it. And I didn’t listen to the press conference the other day expecting this newly formed body to suddenly have polished and progressive answers to these kinds of questions. But if what matters most isn’t where we’ve been but where we are headed, then in a top-down organization like the LDS church, it matters a great deal that the questions troubling so many of its members are being carefully considered by those in command.

And nothing about the reactions or answers I saw and heard during that press conference gave me hope that that is the case.

My husband and I aren’t going to draw any sort of long-term conclusion based on one disappointing press conference. But this Sunday, my family isn’t going to be in an LDS church building—not because we want to make some kind of statement with our non-attendance, but because for the first time in a long time, we’re both on empty. Hauling your heavy questions with you each week to a place that doesn’t know what to do with the kinds of questions you bring gets old. And nothing saddens me more about it all than when I think back on how excited my 3 year old was last week when she woke up knowing that she’d be going back to Primary, and how happy my baby was after sacrament meeting to run out of my arms and into her nursery class.

I want this for them. I want them to experience the fun and quirky and beautiful things that I got to experience as a young girl growing up in the LDS church. But if Mormonism cannot feel and sit with with the kinds of God-given questions that I know my inquisitive girls will find growing within them someday, then they deserve better.

January 17, 2018

On Change

[image error] Change is sometimes the best. Change can bring new hope, new resources, and new vigor. I live in upstate New York where winters can be very rough. The change that comes with Spring brings neighbors outside and back to the community. Everything feels friendlier. Sometimes a change is what we need to renew. A change is as good as a rest, as my Grandma used to say. Sometimes change gets us out of unhealthy environments or relationships. If society never changed, I would not be able to vote or have my own credit card or own property.

Change is sometimes the worst. With change comes ambiguity, and the chance that things could be worse. Change can mean loss, even a change that is generally positive. When I moved across the country for professional opportunities, it was overall a good thing. I had chances to grow and learn and stretch myself in ways I wouldn’t have done otherwise. But it meant leaving my family behind. Positive change can also be followed by negative backlash. I would argue that a lot of the political climate in the US right now is due to backlash from the progress made under the previous administration.

The other thing about change is that it is continuous. It sounds cliche, but humans are literally always changing. As a developmental psychologist, it always strikes me how adaptive we are as a species. We react to changing contexts by changing our selves. This allows us to survive and flourish in the face of difficulty. This isn’t as Pollyanna as it may sound. Sometimes those changes lead to dysfunction – things like attachment disorders protect from the emotional devastation of rejection, but make healthy relationships difficult, for example. The goal of adaptation is survival, which is not necessarily the same as optimal development.

Recently, I’ve been through a lot of change personally, just as we all have been through a lot of change as a church and as a society in the last months and years. (I know many of us have strong feelings about changes made in the First Presidency this week.) And I don’t know about you, but I find myself reeling. It’s like I can’t adapt fast enough and so have just ended up confused and bewildered, and, if I’m being totally honest, a little bit paralyzed. All this big change can start to make one feel as though they do not have agency…things keep happening to us, things that are out of our direct control. One of my favorite things in Mormonism is the emphasis on agency – it comes from God, and he will not take our agency away. We have to make choices.

My new motto is from Kerry Washington, “You can be the lead in your own life.” There are certainly things happening that affect my life drastically that I cannot control. But I am resolving here and now not to relinquish my agency. I can still make choices. I can still. I can still influence my small little sphere. I can get up every day and do my best work. I can be kind and smile at the people in line at the grocery store. I can educate myself on perspectives I may not understand. I can love my husband. I can advocate for my students and help them be successful.

It is still frustrating to not be able to be able to influence things the way you want to, especially when things aren’t going the way you would choose for them to go. I’m not saying I am ready to settle, or that I’m not still frustrated. But my goal now, I think, is to try and stop wasting energy on things I can’t impact directly, and redirect that to things I can. I’ll let you know how it goes.

January 16, 2018

Advocates for women react to the transition to a new Mormon prophet

President Thomas S. Monson, Elder Russell M. Nelson and other Mormon leaders and their spouses at the Kyiv Ukraine temple dedication in 2010

In this episode of the Religious Feminism interview series, Mormon advocates for women reflect on the legacy of Mormon church president and prophet Thomas S. Monson, who recently passed away, and discuss their expectations, hopes and concerns about the transition to his successor, President Russell M. Nelson. You can find episode notes for the Religious Feminism Podcast here at the Exponent website: http://www.the-exponent.com/tag/religious-feminism-podcast/

Advocates who participated in this podcast:

[image error]

Carolina Allen

Carolina Allen is the founder of Big Ocean Women, which promotes maternal feminism, defined as having a voice in the the public square for faith, family, and motherhood. Carolina is a native of Brazil and an immigrant to the United States, and participates in international policy issues at the United Nations.

[image error]

Carol Lynn Pearson

Carol Lynn Pearson is a poet, playwright and author of several books about the concerns of Mormon women and the Mormon LGBTQ community. Her most recent book, The Ghost of Eternal Polygamy: Haunting the Hearts and Heaven of Mormon Women and Men, focuses on the need to address the remnants of polygamy theology and policy that still affect members of the LDS Church, even though the practice was abandoned over a century ago.

[image error]

Bryndis Roberts

Bryndis Roberts is Chair of the Executive Board of Ordain Women, an activist organization seeking equality and ordination to the priesthood for Mormon women, and one of the founders of FEMWOC: Feminist Women of Color, a forum for feminists, womanists and Mormons of color.

Links to Connect and Learn More:

Carol Lynn Pearson on Facebook

Additional Resources Discussed in the Podcast:

The Ghost of Eternal Polygamy: Haunting the Hearts and Heaven of Mormon Women and Men

A Plea to My Sisters by Russell M. Nelson, 2015

Listen and subscribe below:

January 14, 2018

Guest Post: Currently Between Last Names

[image error]by Lesley Butterfield Harrop

What’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet. Those words of Shakespeare seem empty in the midst of an identity crisis. Names are everything. They are everywhere. They are how we determine who we are, what we do, what and how we believe. Names are important. So important, in fact, that to change them takes an act of government, both literally and figuratively.

I am going through a divorce. Hence, the issue of my name has recently come under scrutiny. It has even risen to be the subject of spirited debates in circles of friends, family, but mostly within myself. Not by the fault of anyone else, but by the self-awareness of my soul. Going through a divorce in the same ward is nothing short of a living nightmare, as one can imagine. Regardless, I hold my head high and steer clear of those who would repeat rumors and believe untruths. This leaves me reaching out to new people, who are unaware of the juiciness of my personal life. I found the typical self-introduction goes something like this:

“Hello, I’m Sister [insert awkward pause as I try to figure out who I even am.]”

My air of outer confidence is a poor match for the identity crisis I’m feeling inside. I try again,

“Hello, I’m Sister [insert married last name.] I mean, Sister [insert maiden last name.] But you can call me Sister [insert botched hybrid of married and maiden last names.]”

No, that doesn’t work either.

Who am I? I may not even know. To embrace my married name, feels too victimizing. It hurts too much. I took that name upon myself as a symbol of hope, faith, loyalty, sacrifice, and love in my marriage. Sadly, the marriage has ended because those same qualities were not reciprocated. That name was part of my promise, which I kept. But now I am releasing myself of that promise. To release myself of that name is fitting. I can feel the empowering cleanse of shedding that name. It feels like I imagine a snake must feel as she sheds her skin: renewed, refreshed, revived.

But taking back my maiden name? That’s highly problematic in its own right. I fail to recognize that young girl with that shiny maiden name who was full of innocence, bright-eyed, thinking her life would be set, after finding a returned missionary and getting a temple marriage to boot. A lifetime has passed since that girl even existed. She is gone. Surely she is, but in her place, a woman. Wise, grown, mature, with a wrinkle……or seven.

I realize that the wise woman with one (or seven) wrinkles came about in this space. The space between married and maiden. The space between separated and single. This space is her birthplace, the ambiguity her peace. She was grown from the weeds and sparked from the ashes. This space birthed a strong woman who leads her family with fierce independence. This space made way for her wings to spread. I can honor this space. I cherish this space. It made me her.

I try one more time, with my outstretched hand and a friendly smile without a trace of shame,

“Hello, I’m Sister Currently-Between-Last-Names.”

Yes, that’s me.

Lesley is an RN with ambitions to develop programs to teach emotional intelligence in the community. She freelances as a photographer and writer, along with raising her four young children who happen to love dance parties in the kitchen.

January 13, 2018

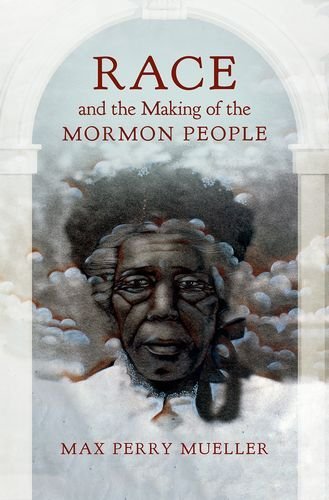

Overcoming Racist Religious Teachings with Max Perry Mueller

Max Perry Mueller

In this episode of the Religious Feminism interview series, Max Perry Mueller, author of Race and the Making of the Mormon People and an assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, discusses the history of racism within Mormonism’s policies and theology and how advocates can work toward racial justice within their religious communities. He also tells us about his Fundamentalist Christian/Episcopalian/Wiccan upbringing and why he recently decided to join a church with more conservative views than those he personally holds. You can find episode notes for the Religious Feminism Podcast here at the Exponent website: http://www.the-exponent.com/tag/religious-feminism-podcast/

Links to Connect and Learn More:

Race and the Making of the Mormon People

Race and the Making of the Mormon People

History Lessons: Race and the LDS Church

What’s coming for religion in 2018?

Max’s blog (where he will be writing about his “Agnostic Christian” project throughout 2018): maxperrymueller.com

Max on Twitter: @maxperrymueller

Additional Resources Discussed in the Podcast:

A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835-1870 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835-1870 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

The Trek Continues! by M. Russell Ballard, 2017

Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness by W. Paul Reeve

If There Is No Struggle, There Is No Progress by Frederick Douglass, 1857

Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (SNAP)

Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics (Library of Theological Ethics)

Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics (Library of Theological Ethics)

Letter From Birmingham Jail by Martin Luther King Jr., 1963

Mormon women march for entry into priesthood

Listen and subscribe below:

January 12, 2018

Guest Post — Made in Her Image: The Body Image Lesson My Heavenly Mother Taught Me

[image error]

I recently had a powerful experience with Heavenly Mother – more personal and pivotal than anything I’ve experienced with Her before. I’ve hesitated to share it, and then was prompted to share it during a Relief Society lesson I was teaching last week. It felt right to share it there, and it feels right to share it here. My Mother in Heaven taught me something about my body that I’ve been teaching girls and women for years, and I’ll never forget it.

I have a Ph.D. in body image resilience and run a nonprofit dedicated to promoting positive body image, but that doesn’t mean I’m immune to the anxiety, shame, and fixation on appearance so many women bear. As a woman with a body, no number of advanced degrees or years of activism could ever fully free me from the stifling objectification of our world and the body-monitoring self-objectification that our world encourages.

This work in body image activism is something I feel called to do, and have felt the guiding hand of my Heavenly Parents throughout my 10 years of college, and especially as I wrote and researched my dissertation, and during my dissertation defense where I had the surprising opportunity to bear testimony of the church’s feminist foremothers and our Heavenly Mother herself. It was powerful. The four male professors and one female professor in that University of Utah room cried with me and told me the experience was transformative. It was transformative.

I’m a relatively new mom – at the time of my writing I have a 20-month-old daughter. My expertise is in body image resilience, or becoming stronger because of difficult feelings and experiences in my body, not in spite of those things. This summer, I experienced one of those difficult things I teach about.

I love swimming. I love the water. I’ve committed for years to never miss an opportunity to swim because of body shame that tells me I’m unfit to be seen in a swimsuit. And because of this, swimming has brought me great joy and a constant reminder of my favorite Beauty Redefined mantra: My body is an instrument, not an ornament! But one day this summer, as my husband and I drove home from a fun day at the lake with our baby, I was suddenly drowning in body shame as I scrolled through pictures my husband had taken of me and my baby. I was caught off guard at how ashamed I was of my body, and I quickly went against all my own teachings and deleted the photos.

When we got home, I laid on my bed alone and prayed aloud while my husband was showering. I needed my Mother, and I asked for Her help. I told Her I was overcome with body shame (and guilt because of the shame) and I asked for Her to comfort me. And as soon as I asked, the warmest feeling of love and pride washed over me. I saw myself walking somewhere – I was looking at my body from behind. As I looked at myself, I felt the same kind of pride I feel about my baby girl. I love every inch of her – her belly, her legs, the fuzzy hair on the back of her head. I am so proud of her. I felt that for me, from my Mother. I felt how She feels about me, and it extended beyond my body. As I watched myself walk, I felt this pride for who I was and what I was doing. I can only describe it as absolute, unconditional pride and love.

I laid there and cried tears of joy. My shame washed away. I grabbed my phone and wrote down what happened so I wouldn’t forget. The note in my phone ended with, “She doesn’t want me to feel ashamed. She wants me to be happy and proud and continue on. I felt Her. I felt Her love.”

And I did. And that love – love that I can only compare to the love I feel for my baby, which doesn’t do it justice – is the love She has for all of us. I know this is true. Women, who bear the burden of so much pain in our bodies, physically, mentally, and emotionally, are designed in the image of a Mother in Heaven who loves us and we love Her. She is so proud of the ways we rise with resilience in the face of so much pain. And She reminded me that day that She is there to lift us up.

Lexie Kite, Ph.D., is the co-director of the Beauty Redefined Foundation (www.beautyredefined.org) alongside her twin sister, Lindsay Kite. Since establishing Beauty Redefined in 2009, Lexie and Lindsay have become leading experts in the work of body image resilience through research-backed online education available on their website, social media, and through speaking events to tens of thousands across the US.

January 10, 2018

A Personalized Assembly Line Baptism

[image error]When my oldest daughter was baptized, we had permission to hold a family baptism in order to accommodate her grandmother’s travel from out-of-state, separate from the stake baptism where all the other primary kids were baptized that month. I planned and conducted the baptismal service, making sure that the people who are important to my daughter’s life had a part in the proceedings. I was particularly careful to give spiritually meaningful assignments to the women in her life since church policy excludes women from officiating the baptism, officially witnessing the baptism, officiating the confirmation, or standing in a circle while she is confirmed. I balanced these male-only tasks with speaking assignments, prayers and musical numbers by women.

But I did note with a bit of guilt that it took three hours to fill the baptismal font with water that would only be used once for a few minutes—quite wasteful in the desert where I live. As long as we continue to baptize by immersion, it makes sense to baptize multiple people on the same day.

[image error]When my second child was baptized, Grandma was able to arrange her travel to attend a stake baptism—an event that is often referred to ruefully as an “assembly line Utah baptism”.

I am pleased to report that my local stake primary presidency balanced the need to baptize many children on the same day with personal attention to each child and their family. A member of the stake primary presidency visited me and my child to discuss the program that would take place in the chapel prior to the baptism. Each child to be baptized would have the opportunity to go to the stand and share their testimony or their favorite scripture story. The stake also gave each child one place on the program to insert a family member or friend of their choice. Our family had the opening prayer and we chose Grandma. Each child chose a favorite primary song or hymn for the congregation to sing immediately before his or her baptism.

After the child’s favorite song, their family and guests were excused to the baptismal font to see the child baptized and then each child was sent to a separate room for their confirmation, where we had the option to immediately proceed with the confirmation or personalize the event with our own program. I created a 10-minute program for the confirmation room including a talk by me, a song by me and a sibling, and brief remarks by each grandparent. I appreciated this sacred family time separate from the rest of the stake. I am grateful that my stake facilitated such a thoughtful baptismal experience for my son and my family.

The only hiccups resulted from churchwide policies that give the roles of presiding over and conducting baptisms to men after women do the behind-the-scenes work. Not only did putting men in charge on the day of the baptism serve to make the women who had actually planned the event invisible, it also resulted in some minor glitches to the program. When it was my son’s turn to go to the stand, the man conducting, probably unaware of the exact instructions my son had received the stake primary presidency, asked him if he would like to bear his testimony. Startled because he had prepared to tell his favorite scripture story instead, he just shook his head no, and was almost sent back to the audience without sharing what he had planned. I had to run up to the stand to intervene. Inside our family’s confirmation room, the man conducting instructed the other men to go ahead and start the ordinance, either forgetting or unaware that the stake primary presidency had given us the option of holding a family program there. Again, I had to assert myself to ensure that the program proceeded as planned.

Overall, both baptisms were good experiences. My stake’s methods for conducting a group baptism demonstrate that group baptisms don’t have to be impersonal. Now, if only general church policies were more inclusive of women!

January 6, 2018

Relief Society Lesson Plan “The Eternal Everyday” by Elder Quentin L. Cook

by Erika M.

As a teacher, both at church and at the university, I find that the best lessons allow students to discuss ideas deeply and consider their own experience from a new light. This requires me to be in a place where I have myself thought deeply about the ideas while also not being so wedded to my own way of thinking that I am closed off to listening to the perspective of my students. I feel most successful when I spend as much time listening, not merely hearing, to the ideas of my students as I do “teaching.” For this reason, I often find that many of my lesson plans involve preparing open-ended questions, often more that I might realistically need. That way if a question just isn’t the right one for the audience, I have other questions prepared waiting in the wings. My understudies, if you will. It also allows me to quickly change the tenor of the conversation by asking another question if I feel that we have entered a space that will not work for the audience, will bring the spirit of contention, or is too one-sided.

Additionally, I have learned not to be afraid of silence. People often need more time to think than we might realize; especially during those frightening moments when we hope that our question hasn’t just flopped, and time is going by at a snail’s pace.

I would probably start this lesson by reading the following quote that comes at the beginning of Elder Cook’s talk:

Sometimes man’s purpose and very existence are also described in very humble terms. The prophet Moses was raised in what some today might call a privileged background. As recorded in the Pearl of Great Price, the Lord, preparing Moses for his prophetic assignment, gives him an overview of the world and all the children of men which are and were created.

Moses’s somewhat surprising reaction was, “Now … I know that man is nothing, which thing I never had supposed.”

Subsequently, God, in what amounts to a rebuttal to any feelings of unimportance that Moses may have felt, proclaimed His true purpose: “For behold, this is my work and my glory—to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.”

I would then suggest that, as both things cannot be true and, yet, they are, that the truth of the matter lies in the paradox. Some discussion question I might use would include: How might both things be true? How can we live in the paradox between these two truths? How might holding on to this slippery space, this idea between ideas, change the way that we behave? How might this set of concepts help us find humility without being self-deprecating? How might Moses’ privileged upbringing have caused him to place greater value on his position? Why was it important, given his own history, that he first acknowledge his own insignificance to fully understand his true position as a child of God? Why do you think that it was so important to God that Moses be corrected? What does that tell us about our relationship to the Divine? (Depending on your inclination, questions such as the following might be asked; however, they might open up an entirely different lesson. Are there other paradoxes you feel the gospel teaches? If God so often chooses to teach us in paradoxes, what does this tell us about truth? About the importance of balance?)

After sufficient discussion, I would use the comment made by sisters to take us to the next portion of Elder Cook’s talk. He writes/says:

We are all equal before God. His doctrine is clear. In the Book of Mormon, we read, “All are alike unto God,” including “black and white, bond and free, male and female.” Accordingly, all are invited to come to the Lord. Anyone who claims superiority under the Father’s plan because of characteristics like race, sex, nationality, language, or economic circumstances is morally wrong and does not understand the Lord’s true purpose for all of our Father’s children.

This quote is, in my mind, one of the gems of the lesson. It has the potential to ask people to do some real soul searching if given time to pause and think rather than glossing over it with a “of course, this is true.” In order to facilitate this deeper soul searching, I might ask the following: How might our actions change if we lived this truth? It is interesting the Lord chooses the word alike here. What do you make of this word choice rather than either equal or the same? Are there ways in which we inadvertently create a culture in which some might not feel invited to the Lord’s table? How can we work to create a community where all feel welcome and valued? In our wards? In our neighborhoods? In our larger communities? Are there ways in which we internalize these differences ourselves and then use them to undermine our own place in the God’s plan? Do we ever not sit down to the spiritual feast provided by our Heavenly Parents because of we have internalized a misguided view of our own worth?

This might also be a place to discuss an anti-racist perspective of the Book of Mormon. While there are racist verses in the Book of Mormon and the Church’s own history with race is wrought to say the least, there are some interesting cases to be made for an anti-racist reading of the Book of Mormon. In an article on Medium by Kwaku El (a member of African heritage), he writes the following, in response to the question, “why are there black Mormons? How could any self-respecting African American subscribe to the doctrine of the Latter-day Saint movement?”:

The Holy Bible has a severe lack of verses condemning racism. The clearest the Bible gets in regards to the sin of racism is arguably Romans 10:12 and Galatians 3:28. “There is no difference between the Jew and the Greek: for the same Lord over all is rich unto all that call upon him.” (R10:12) “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.” (G3:28) For a people who view religious truth on a close par with racial justice, there is a serious lack of clarity among racism in The Holy Bible. These verses preach unity in the savior through grace and salvation, however not in social status or political protection. For the slaves of the ancient biblical period could have salvation in the next life, but not equality in their current. The Apostle Paul never condemns the actual teaching of slavery, or condemns racism itself. He seems to be preaching of an inclusive gospel spiritually, but not doctrinally preaching the importance of inclusivity in all societal measures, which would follow the law of Christ more accurately. The Book of Mormon however condemns racism and prejudices in a much more specific way, 2 Nephi 26:33… “…he inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness; and he denieth none to come unto him, black or white, bond and free, male and female; and he remebereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile.” (2N26:33) The words “all are alike unto God” is a very powerful phrase. Not only are we all one in Christ Jesus, but in general all are alike. We become equals without any debate when we are in the body of Christ, yet even without such, we are created the same, and are alike.

I think that it is really important to emphasize that this doesn’t mean that we should pat ourselves on our back and avoid confronting our own racisms. Nor does it mean that we don’t need to look closely at our own history but, rather, that we should hold ourselves to this higher standard and repeatedly ask ourselves, “What lack I yet?”

Elder Cook then goes on to say: “When we really contemplate God…, and Christ the Son, who They are, and what They have accomplished on our behalf, it fills us with reverence, awe, gratitude, and humility.” It would be interesting to use this statement to help sisters consider the ways in which considering their relationship to the Divine, their gratitude for the plan, and the sacrifice of our Heavenly Parents and Jesus Christ fill them with reverence and awe. You might ask: When you consider the Plan of Salvation, how does it fill you with reverence and awe? What about it do you find especially miraculous, beautiful, or compelling? How does this knowledge help you reverence God? The Savior? Ourselves? Those around us? I think too often we skip over this kind of reflection because we feel like we will just get Sunday School answers but if we, with our questions, ask the sisters to dig deeper into their own experiences with the Divine, I find, we are often rewarded with some of the richest discussion, the most powerful spiritual feasts.

Once Elder Cook has spent time establishing who we are and our relationship to God, he uses the lives of both ancient and modern members (Alma, Heber C. Kimball, Orson Hyde) to discuss the importance of humility in our pursuit of righteousness. He exhorts:

Sometimes humility is accepting callings when we do not feel adequate. Sometimes humility is serving faithfully when we feel capable of a more high profile assignment. Humble leaders have verbally and by example established that it is not where we serve but how we faithfully serve. Sometimes humility to overcoming hurt feelings when we feel that leaders or others have mistreated us.

Here again is a paradox. We are humble when we accept callings that we feel are “too big” for us but we are also humble when we serve in callings we feel don’t fully utilize our skill sets. What is Elder Cook really trying to say here? What is he trying to teach about service? What is he attempting to demonstrate regarding our relationships to our assignments in the Church?

I would also open up a conversation about how we can humbly forgive those who have hurt us without humiliating ourselves. Elder Cook asks us to be humble in our forgiveness not to allow ourselves to be humiliated. When we talk about humility in the scriptures, we are talking about humility before God. He also says that it is important that we overcome hurt feelings but not that we place ourselves in a position to continue to be hurt. With that clearly articulated, I would ask the sisters: How does one find peace when they have been hurt by another? How are humility and the ability to forgive related? How might humbling ourselves before God help us to find the strength to forgive? If appropriate, I might share an experience where I found strength to forgive through turning to the Lord.

In a related matter, I would also turn to a talk given by Virginia H. Pearce. In the talk, “Prayer: A Small and Simple Thing,” Sister Pearce shares an experience she had while visiting the BYU Museum of Art. She describes the following while examining Christus Consolator by Carl Block:

( Consolador Carl Heinrich Bloch 1882. Palacio de Frederiksborg, Copenhague, Dinamarca)

I love to look at each individual who seeks consolation from Christ. You can see the troubles of mortality on their faces. These are they who know they cannot do it alone. Bloch described the joy we can take in adversity when we know it brings us to Christ. He said: “When things are at their worst they can then become their absolute best. I think then that I have so much to thank God for, and it would be foolish to demand that one should be happy in this life. By that I mean always sparking, always seeing the ideal under the light sky.”“No, grey skies and rain splashing are part of it – one must be washed off thoroughly before one goes in to God.” I like that artist’s image – being washed off thoroughly by the grey skies and rains of life as we kneel in humility, in our fragileness, asking for God’s help. “Be thou humble; and the Lord thy God shall lead thee by the hand, and give thee answer to thy prayers.”

How can being humble help us to use the trials we face as a refreshing, or, at least, cleansing rain?

Looking at other ways in which humility helps us to develop, Elder Cook also emphasizes the importance of humility in doing missionary work. How does humility help us do missionary work? Why does God think it is such a key trait in having success teaching the gospel to others?

Finally, Cook looks outside of the church to the ways in which a lack of humility has harmed communities and nations. He exclaims:

The widespread deterioration of civil discourse is also a concern. The eternal principle is also a concern. The eternal principle of agency requires that we respect many choices with which we do not agree. Conflict and contention now often breach “the boundaries of common decency.” We need more modesty and humility.

I would pair this statement with one of these from Gandhi – “It is unwise to be too sure of one’s own wisdom. It is healthy to be reminded that the strongest might weaken and the wisest might err” or “the first condition of humaneness is a little humility and a little diffidence about the correctness of one’s conduct and a little receptiveness.” And then I would ask: How do humility and modesty breathe life into discourse? What are their benefits? What are their limits?

Elder Cook ends by again linking humility and forgiveness. He directs that we must be cautious of “any form of arrogance.” This would be a good place to then discuss the distinction between arrogance and self-worth. In an Ensign article from January 2005 entitled “Confidence and Self-Worth,” Elder Glenn L. Pace writes:

To be humble is to recognize our utter dependence upon the Lord. We are conscious of our strengths, but we do not exalt ourselves and become prideful, for we know that all good things ultimately come from God. We are conscious of our weaknesses, but we know the Lord can use those very weaknesses to bless our lives and that through Him, as we learn from the book of Ether, our weaknesses can become strengths. To lack confidence is to have feelings of low self-worth. We are preoccupied with our weaknesses, and we lack faith in the Lord’s ability to use those weaknesses for our good. We do not understand our inestimable worth in the eyes of God, nor do we appreciate our divine potential. Ironically, both pride and a lack of self-confidence cause us to focus excessively on ourselves and to deny the power of God in our lives.

How might do we develop self-worth while avoiding the sin of arrogance? How might humility, paradoxically, help us to develop greater self-worth.

Finally, Elder Cook bears his testimony of the Savior. He “bears a sure witness of the Savior and His atonement and the overwhelming opportunity of humbly serving Him each and every day.” This turn of phrase “humbling serving” the Savior creates a wonderful space to both connect the ideas shared by class members and bear testimony of Jesus Christ.

Depending on your ward, it is important to note that the historical context for this statement is a rebuttal of Ayla Stewart, the rise of the Alt-Right in certain Mormon circles, and the gathering of Neo-Nazi’s that took place in Charlottesville.

This article goes into great detail regarding the Book of Mormon’s references to dark skin and the Lord’s rebuke of members who engaged in racism because of this “curse.” It is an interesting read – by no means complete – but interesting nonetheless. https://medium.com/@kwakuel/perhaps-a...

He does not say it here but I would have no problem adding – Sometime humility is accepting that we have inadvertently (or, perhaps, advertently) hurt someone else.

In case it isn’t obvious, I love unpacking paradoxes.

Eugene England writes, in his article “Healing and Making Peace,” that Christ’s solution to violence is “contained in the Sermon on the Mount…; in Christ’s maledictions against the Pharisees (Matt. 23:13-29), which required Jews to recognize the violence in themselves – that they have always killed the prophets who bring the message of peace and will kill him also; and supremely and finally in Christ’s death. Christ does not die as a tradition, guilty scapegoat, who hides the sins and violence of the community. Rather, Christ insists upon being recognized as an innocent victim, a sacrifice whose perfect forgiving love clearly reveals the cost of our violence and the only way to stop it. He lived out his teachings and sealed his testimony with the divine authority of his perfectly innocent blood” (Making Peace: Personal Essays, 8) England also goes into great detail on the true meaning of turning the other cheek in his essay “The Prince of Peace” – also in Making Peace: Personal Essays. It makes a good anecdote to the idea that, in order to be forgiving or to work for peace, we must allow ourselves to be a doormat.

This quote might open up an interesting conversation about the paradox of “Man (and woman) is that (s)he might have joy” and the importance of trials to our individual development. But, again, with the paradoxes.

Taken from At the Pulpit: 185 Years of Discourses by Latter-Day Saint Women

There is that word again.