Exponent II's Blog, page 275

February 3, 2018

Mercia Second Ward: Part Deux

This is the second part in our ongoing series about a recently discovered set of documents that illuminate for us what life was like in a Medieval ward. Though many plain and precious truths were lost during the time of the Great Apostasy, faithful saints worked hard to live the Gospel according to the light and knowledge that they had.

The announcement said “bring your children to the Ward assignment at the Stake Welfare Garden. It is important that ward members of all ages engage in service.” This went about as well as one might expect.

[image error] Recently church leaders announced that, in addition to serving the ward in visible ways through blessing and passing the sacrament, serving as ushers and serving as home teachers, teenage boys would now also carry out sacred ordinances in the Temple. “By recognizing their maturity and unique potential for leadership, we honor these Sons of God for their dignity, reverence and spirituality” said President Odo of the Wessex Temple District. Sister Odo tried to comment but could not be heard over the sound of slapping towels against rocks by a rushing stream.

Burthred invited his Home Teachee Hildegarde to share his hymnal. She was on the point of accepting when she noticed the beady eyes of the bishopric and their wives fixed eagerly upon them. Another match in the making?! Knowing that sharing a hymnal could easily be mistaken for consent to the laying on of hands and the gift of tongues, she refused and hastened out the door.

[image error]President Aelf decided the Sisters would welcome a guest lecture in Relief Society about the Family Proclamation. He opened the floor to questions and was surprised to learn that some sisters felt it was impossible to be equal partners if one partner presided over the other. He chuckled warmly and began to explain how really the two terms were not only compatible but really it made perfect sense if you only took the time to study and understand that the true meaning of patriarchy isn’t the world’s definition of patriarchy. Twenty minutes later he found himself thoroughly contorted from his attempts to resolve incompatible assertions.

[image error]Having a 17 month old child could make church a thankless chore, but it had a few advantages. The minute President Aelf began his lesson with the question “How has the Family Proclamation blessed your life,” Sister Godgifu realized that little Alfred had to be taken out of class immediately. Did he need his diaper changed? Or a snack? Was he fussy? Did he need to nap? Doesn’t matter. Her duty as a Mother in Zion was clear, and she was not one to shirk it.

“Irrespective of Cause”: a Story about Jon Huntsman, Sr. and HPV Vaccine

Jon Huntsman Sr. and Karen Huntsman (Image courtesy of the Chronicle of Philanthropy)

Former LDS Area Seventy Jon Huntsman Sr., founder of the Huntsman Cancer Institute, passed away today. In his honor, I would like to share this bit of breakroom gossip from about a decade ago, when I was an employee at the Utah Department of Health.

The Food and Drug Administration had only recently approved the first vaccine protecting against Human Papillomavirus (HPV), a sexually-transmitted infection that is the leading cause of cervical cancer. Now that an effective vaccine was available, state lawmaker Karen Morgan sponsored a bill to fund vaccination of women and girls, with fervent support of local health advocates. The bill required a one million dollar appropriation, but in the end, the state legislature only appropriated $25,000, with a big caveat—none of the funds could be spent on vaccines. Instead, lawmakers wanted to direct the funds toward educating women about “abstinence before and fidelity after marriage being the surest prevention of sexually transmitted diseases including the human papillomavirus.”

About a month after the legislative session ended, I was eating lunch in the Health Department’s cafeteria when a coworker came running in, absolutely beaming.

“You will not believe what just happened,” she exclaimed. She had just finished a meeting about the new appropriation. Several stakeholders were there, including lawmakers and Jon Huntsman, Sr., representing the Huntsman Cancer Institute. As she described it, some of the people in attendance kept raising questions along the lines of, if you vaccinated girls against sexually transmitted diseases, what would stop them from having sex? Some even suggested that cervical cancer was an appropriate punishment for promiscuity.

Seemingly on impulse, Huntsman pulled out his weapon—a checkbook—and slammed it on the table. Moments later, he passed a check with lots of zeroes on it to my friend and said, “This is for vaccine.”

The next day, the Utah Department of Health announced that Jon and Karen Huntsman had donated $1 million to the Department for cervical cancer prevention, including HPV vaccination, thus paying out of their own pockets the full sum that had originally been requested of the Utah Legislature.

February 2, 2018

Pioneer Phil makes his 2018 Cumom Day Prediction

Photo by Aquistbe. Used under the CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license. No changes made.

HILL CUMORAH, Manchester, Ny – Mormonism’s most famous Cumom has made his prediction.

On Friday morning, as crowds gathered around, Pioneer Phil saw his shadow and predicted six more millennia of patriarchy.

Legend has it if a furry/scaly/feathery animal casts a shadow on Cumom Day, Feb. 2, expect six more millennia of patriarchy. If not, expect the Second Coming.

In reality, Phil’s prediction is decided ahead of time by the suits in the Church Office Building on Temple Square, a tall and spacious building in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Records dating to 1830 show Phil predicting more patriarchy 140 times while forecasting an early Millennium just 31 times. No records exist for the remaining years.

January 31, 2018

Exponent blogger Liz Layton Johnson interviewed by Salt Lake Tribune’s Mormon Land podcast

[image error]Liz talks about her popular (and sometimes controversial) ideas to improve the church inspired by Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. Listen here: ‘Mormon Land’: 95 ways to improve the Mormon church — from new hymns to padded pews and letting girls pass the sacrament

Read the original post here:

My Ninety-Five Theses for Today’s Mormon Church

The Exponent’s Religious Feminist Podcast featured on NBC News

[image error]The article quotes Exponent blogger and podcast host April Young Bennett and podcast guest Carol Lynn Pearson. Read it here:

Noted heart surgeon Russell Nelson unlikely to transform Mormon church as new president

Find the original podcast episode here:

Advocates for women react to the transition to a new Mormon prophet

January 28, 2018

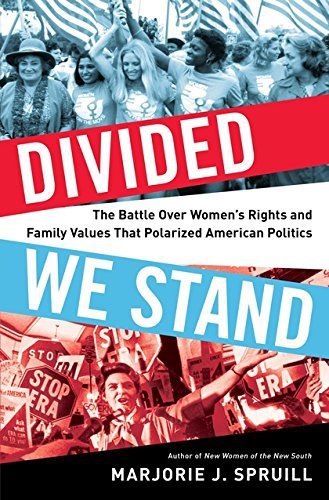

The Rise of 2nd Wave Feminism and the Religious Right in the 70s with Marjorie Spruill

Marjorie J. Spruill

In this episode of the Religious Feminism interview series, Marjorie Spruill, author of Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics tells us about two American women’s movements in the 1970s that shaped American politics today: 2nd wave feminism and the rise of the religious right, the part that Mormons, Catholics, Evangelical Christians and other religious groups played in the clash, and how this moment in history explains much of the polarization of American politics today. You can find episode notes for the Religious Feminism Podcast here at the Exponent website: http://www.the-exponent.com/tag/religious-feminism-podcast/

Links to Connect and Learn More:

Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics

Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics

Divided We Stand Facebook Page

New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States

One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Women’s Suffrage Movement

Additional Resources Discussed in the Podcast:

Pedestals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority, and Equal Rights by Martha Sonntag Bradley

Pedestals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority, and Equal Rights by Martha Sonntag Bradley

Mormon Feminism in 1977 and Today by April Young Bennett

We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics by Neil J. Young

Listen and subscribe below:

January 27, 2018

LDS Church statement on DACA calls for ‘hope and opportunity’

Milk Before Meat so Where’s the beef?

When my third child finally weaned at 15 months of age, he seemed to have the flu all-the-time. Diarrhea that would shoot out of the diaper and down his legs at times and smell particularly foul. I had to take him out of cloth diapers and splurge on disposables for a while (he needed a full-on bath after most diapers).

For months I tried elimination diets and allergy free foods. I tried keeping him off eggs, dairy, corn, gluten, etc. It was hard. Gradually a gastroenterologist confirmed that he likely had a dairy protein intolerance. Keeping him off milk, cheese, butter/margarine, and any whey or casein in any product was difficult, but gradually helped. I think I cried with relief when he had a normal poop.

And still my husband would sometimes forget and feed him ice cream or yogurt, because he wasn’t dealing with all this stuff all the time. Even a bite would trigger days of extra laundry and diaper rashes. For a few years I often had to give this child a different meal than the rest of the family because I hadn’t yet re-trained myself to cook with this new food issue in mind.

Then child number four came along and had the same problem. Then child number five. Now I have six children with a dairy protein intolerance; some of them had more food issues besides the milk thing as well. We gradually stopped eating dairy as a matter of course, and now rarely have it. We eat more beans and vegetables to get calcium and protein. Meat consumption also tapered off. The way I feed my family has completely changed as a result of our experience and on the whole I think we are eating much healthier than we ever would have otherwise – that’s the silver lining.

In the church I have often heard stressed the importance of ‘milk before meat’ (Cor 3:2). The church uses this phrase to reinforce hierarchical mysteries that are supposedly revealed only to the ‘worthy’ who have been sufficiently obedient through time and grown up the chain in church authority. Lay members are expected to ‘endure to the end’ in obedience and submission and not to seek for the hidden mysteries. Week after week we attend meeting after meeting and are fed milk and milk and milk. Here’s the thing–I have grown intolerant to milk. It makes me sick to my stomach and gives me diarrhea. Where is the ‘meat’? Where is the sustenance I need for growth and health? The church would have me stay and await this greater meal, but I am no longer convinced that it is there at all, or whether meat is actually the best thing for my health. The last 13 years I have had to bring special food for my children to ward dinners and activities because of their food issues. Now I would need to bring my own spiritual food to church on Sunday as well. And I find myself less inclined to come to the table.

Paul wrote “For when for the time ye ought to be teachers, ye have need that one teach you again which be the first principles of the oracles of God; and are become such as have need of milk, and not of strong meat. For every one that useth milk is unskilful in the word of righteousness: for he is a babe. But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age — even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil” (Hebrews 5:12-14). This seems to say that there is an appropriate time for teaching, or even re-teaching the fundamentals –this is, until experienced in discerning good and evil. Unfortunately, my experience in church has been that Relief Society lessons are not any richer in doctrine than the Gospel Principles manual. In the Doctrine and Covenants, we are told “And I command you that you preach naught but repentance, and show not these things unto the world until it is wisdom in me. For they cannot bear meat now, but milk they must receive; wherefore, they must not know these things, lest they perish” (19:21-22) So, perhaps we have not yet come to a place as a church where we are ready to eat meat? What then for those who have become intolerant of the diet available? Is it then time to graduate to independent research? What then if we are led to a diet that looks nothing like the “milk only” menu available at church?

I’m concerned that church members are being asked to live on a diet lacking in vital nutrients, being kept always on milk when our palates were made to mature and branch out into other food groups and experience a broader array of spiritual nourishment.

January 26, 2018

“Girls Can Be Leaders”: A Letter to My Daughter for Her 18th Birthday

[My daughter “H” holding her sign from the NYC Women’s March, 1/20/18]

Every so often my husband and I write future letters to our daughters, ages five and three. We email them to an account we set up in their names that we intend on gifting them on their 18th birthdays. This is a modified version of a letter I wrote my five-year-old daughter, whom I’ll call “H.”

Dear H,

I will never forget last Saturday, the day our family participated in the NYC Women’s March with a group of Mormon feminists. My favorite memory from that day is how boldly and proudly you held up your sign (pictured above). You were MAGNIFICENT! Every few minutes marchers would stop to ask us if they could take your photo. Your small but mighty frame clearly exuded your enthusiasm. You never turned down a request to be photoed despite how tired you were. You immediately stopped in your tracks, turned toward the cameras, met the gaze of the marchers, and with a fierce smile and radiant eyes squinted through the sun until they got their shot.

You have been a strong advocate for gender equity in our church ever since I started a dialogue with you about what you were observing in the exclusive male leadership at our church. At age three, you started looking up intently during the sacrament and carefully observing the boys who were blessing and passing the bread and water to the congregation. I saw you quietly observing the boys’ movements throughout the room and I didn’t want you to internalize that our Heavenly Parents think only men and boys are important, given the lack of female representation during this weekly church ritual.

So I started a conversation with you by simply saying that your dad and I believe girls and women will someday be leaders at church too, but that for now only boys and men can be leaders. I told you that your dad and I don’t believe this restriction is of God and that we believe it will change someday. To which your three-year-old self replied, “You mean how all the people on the stand are boys?” I said, “Yes.” Since that day I have tried to protect your believing heart by honoring your desire to learn about spiritual things and how to develop a relationship with the divine with the knowledge that the very place we bring you on Sundays discriminates against you, the LGBTQIA+ community, and is a long way from righting our history of racism in the church. But this is the church that your dad and I were raised in. The church our ancestors sacrificed their lives for. The church that we love. And yet the same church that also hurts us and so many others.

For the Women’s March last weekend you authored a sign that read, “GIRLS CAN BE LEADERS.” A couple of years ago when we were talking about women being leaders, you explained to me that despite the fact that the prophets don’t believe women can be leaders in the church, you matter-of-factly announced, “Someday I’m going to be a leader!” I believe you.

I love how strongly you stand up for injustice and oppression and are fearless in proclaiming your belief in gender equality. Because of our family’s values, your dad and I are struggling with whether or not to consent to your being baptized into the LDS Church at age eight when most of your peers at church will be. We think it is much too young to fully understand the shadow side of the church and how it will impact you; how it discriminates against children who are living with parents in same-sex marriages (there was a recent policy change forbidding them to be baptized until age 18, and only if they disavowed their parents’ marriage); and so many other aspects of church history and church policies that are troubling. Just weeks ago a policy change was made regarding baptisms for the dead in Mormon temples that allows teenage boys to baptize teenage girls as proxies for the dead. This added priesthood and leadership responsibility for young boys is another example of maleness being privileged and femaleness being subordinated. Meanwhile, teenage girls are still excluded from officiating in the ordinance of baptisms for the dead in the temple in any meaningful way, but were offered the same responsibilities as women currently hold in the temple baptistry. This includes tasks that are tangential to the baptisms, including handing out towels.

There are other shadow sides of the LDS Church that concern us deeply: regular “worthiness” interviews (every 6 months) beginning at age 12 involving questions about chastity (sex, and often masturbation) by male Bishops required for young women and men to go to the temple. We don’t want you or your sister to feel it’s appropriate for an adult man to ask you questions about your sexuality. Even if a parent is permitted to be present in the room. And we don’t want you to be put in physically compromising or uncomfortable situations with your male peers—or to make you feel like it’s okay for a male peer to physically dominate you (by holding you underwater even for a second during baptisms by immersion for the dead in the temple). And we especially don’t want you to feel like you were deceived or didn’t have all the information necessary to make an educated decision about whether or not you want to join a church that discriminates against you because of your assigned sex at birth. And that excludes other children from baptism until age 18 because of who their parents love and married. And the harmful doctrine forbidding the queer community to love who they love and be in full fellowship in the church. And people of color continuing to be marginalized despite official church statements to the contrary.

These inequities weigh on my heart heavily as your mom. I worry nearly daily about the possibility of your internalizing negative ideas about your worth, value, and potential because of how the church that brings you so much joy also limits your opportunities for spiritual growth. It denies you the ability to receive ordination to the priesthood as every male peer of yours will starting at age 12; it prohibits you from ever being a full ecclesiastical or administrative leader in the church; it forbids you from publicly praying to your Mother in Heaven (although I model that for you at home); it bars you from your spiritual birthright to give and receive healing blessings as your Mormon foremothers did; and it sets up unequal marital relationships in temple ordinances and sealings (marriage ceremonies) by setting up a male dominating hierarchy in marriage including the possibility of eternal polygamy (a man can be sealed to two women if his first marriage is dissolved through divorce or death, but a woman can only be sealed to one man while she is alive).

Your dad and I work every day to make our marriage more equitable. We are working hard to teach you and your sister that one’s sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation should not limit one’s private or public dreams. We want you to be free of the trappings of patriarchy, but we know that isn’t possible given the society we live in. I often justify continuing to bring you to the LDS Church—my spiritual home—by telling myself that if my daughters can learn to navigate and take a stand against sexism, homophobia, and racism in this church, then dealing with those things in society will be easier. But I don’t know if that is true. Mormonism is your religious heritage on both sides of your family. I want you to understand where you came from, but I don’t want to harm your powerful, intelligent, beautiful soul.

I will continue to fight for equality for all, in and out of the LDS Church, for you my dear H, for your sister, and for all who are marginalized.

I can’t wait to see what the future holds for you. You are determined and unstoppable already at age five. I can only imagine how phenomenal you will be at 25 and beyond.

I dream of a world where the sky is the limit for you.

All my love,

Your Mama

January 24, 2018

“Because I said so!”

[image error]

Are you familiar with the old story about the newlywed and the pot roast? Surely you’ve heard it at the beginning of some sacrament meeting talk, somewhere. The newlywed bride is making a roast for her new husband. She cuts the end of the roast off before placing it in the pan. When asked why she did that, she replies that her mother always did it that way. The bewildered husband asks his mother-in-law about the roast amputation, and she explains that her mother always did it that way. Finally, the grandmother is asked about the mysterious technique. Her answer? “My pan was too small for the roast!”

Usually this story is met with chuckles about the silliness of the bride and how such silliness gets passed on until someone–the smarter one, the man–asks, “Why?”

I am in a place in my life where I ask “Why?”

Growing up, I really hated when my mom answered my never-ending “Why’s” with “because I said so.” I vowed that I wouldn’t do that when I was a mom. (Just one of the many, many words I’ve eaten). “Because I said so” is actually sometimes appropriate, especially with a toddler that cannot understand the rationale for every rule. But toddlers grow up, and by the time they are teens, “because I said so” often yields the opposite of the desired effect.

How many aspects of our religious observance answer “why?” with “because I said so!”?

Studying church history last year really impressed upon me the very human, imperfect, bumbling processes and opinions that led to so many things that are considered absolutes today. The variations of the Word of Wisdom, the varieties of dress standards, the hair/beard/piercing fluctuations (why in the world were men required to wear socks at BYU?), sabbath day observance, and the list goes on. So many points of contention and grief come down to “because I said so” even if it’s called something else. “That’s the way we do things.” “The unwritten order of things.” “Just because.” “We need to have faith.” “Line upon line.” “We’ll understand when we are on the other side of the veil.” Those answers kind of worked for me for a rather long time.

But now I am a grown up. And when I ask “why?” I want an answer.

I am not quite sure how to get my answers, but study and pondering and prayer seem to help.

I am looking at the fruits of various practices and traditions. If the fruits are good, that’s a good answer to “why.” If the fruits are not good, maybe the way things have always been done is not a good way. I haven’t figured everything out yet. Not even close. The fruit test is working pretty well. It is streamlining the gospel for me. Love one another, show that love through kindness, and respect each person’s autonomy is what I am going on at the moment.

How do you answer your “whys?”