Naomi Clifford's Blog, page 8

December 19, 2017

12 scenes of Christmas

Ah Christmas. These days magic has clean gone out of it. It’s all about showing off, too many presents, getting drunk and bad sex at the office party. Hmmm. Actually, if you look at this selection of 12 depictions from the late 18th century to the early 19th, you might think nothing much has changed.

Note: I feel it’s such a shame we have lost the word ‘gambol’ which means to romp or cavort. Seems to have been a lot of it going on at Christmas.

Day 1

Francis Wheatley, 1747–1801, British, The Mistletoe Bough (c. 1790). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Francis Wheatley, 1747–1801, British, The Mistletoe Bough (c. 1790). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon CollectionIn this rustic scene London-born Francis Wheatley (1747-1801) titillates by showing behaviour on the wrong side of proper. Under the mistletoe a young man has a young woman around the waist, his hand dangerously close to her breast. To their right another young woman has collapsed to the floor. Has she had too much to drink? To their left a pregnant woman and her partner show, perhaps, what too much fun can lead to. Meanwhile, a basket of laundry is upset. The household is clearly going to rack and ruin. In the background the older generation look on. When a wild and dissipated young man Wheatley ran off to Ireland with a married woman but by the time he painted this scene he was in his forties and had settled down with his wife, Clara Maria Leigh, another artist.

Day 2

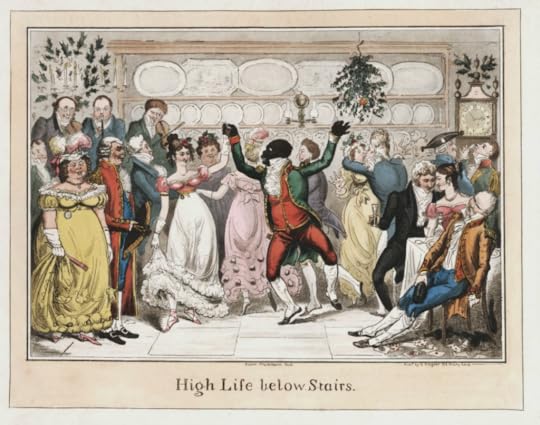

Robert Cruikshank, High Life Below Stairs (1825?). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library.

Robert Cruikshank, High Life Below Stairs (1825?). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library.Mistletoe features in this party in the basement of a grand house where a black footman (here in full minstrel-type caricature) dances with the ladies. It looks like the toffs have come downstairs to muscle in on the action – a particularly smooth specimen is canoodling with a woman on the right while a drunken footman, oblivious, falls off his chair.

Day 3

John Massey Wright, The Ghost – a Christmas Frolic (le revenant) (1814). Courtesy of Library of Congress

John Massey Wright, The Ghost – a Christmas Frolic (le revenant) (1814). Courtesy of Library of CongressA small boy interrupts the Christmas fun fools his family and their guests into believing that a ghost has risen from the grave. Again, a branch of mistletoe hangs from the ceiling but now it’s completely ignored. Centre stage is another black man who looks at the ‘ghost’ challengingly.

Day 4

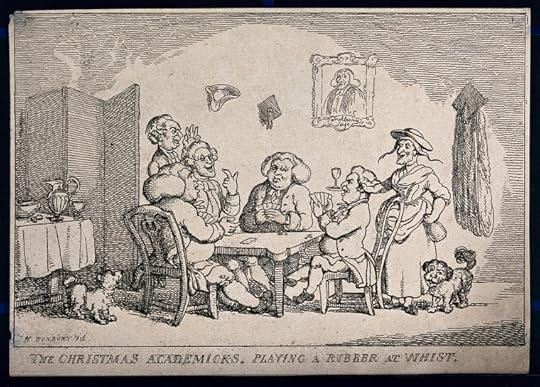

Henry William Bunbury, The Christmas academicks, playing a rubber at whist. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library

Henry William Bunbury, The Christmas academicks, playing a rubber at whist. Courtesy of the Wellcome LibraryThere’s no mistletoe in this etching showing scholars letting their hair down at Christmas. They’ve hung up their mortarboards and gowns and settled down to a friendly game of cards. An old crone helpfully offers a soothing libation, but but only one glass (perhaps they are sharing). Caricaturist Henry William Bunbury (1750–1811), the son of a baronet, was as famous as Rowlandson and Gillray but, unlike them, never produced political satire and so his reputation faded.

Day 5

Thomas Rowlandson, Christmas Gambols (1812). Courtesy of Princeton University Digital Library

Thomas Rowlandson, Christmas Gambols (1812). Courtesy of Princeton University Digital LibraryChristmas has got utterly out of control in this household. In the servants hall, everyone is under the influence of drink and mistletoe and is indulging in ill-advised sexual horseplay. There will be sore heads in the morning. Interestingly, it’s another Christmas scene featuring a black man, proof perhaps that life in Britain was more diverse than we have properly appreciated.

Day 6

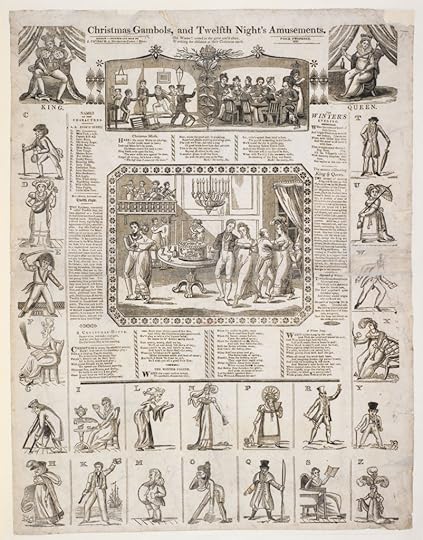

Broadside published by James Catnach, Christmas Gambols, and Twelfth Night Amusements (1823). Courtesy of the British Library Collection

Broadside published by James Catnach, Christmas Gambols, and Twelfth Night Amusements (1823). Courtesy of the British Library CollectionThis broadside sold for tuppence (2d), double or even quadruple the price of most sheets (and from this we can assume it was aimed at the middle-class market). It gives a mix of seasonal song lyrics and depictions of characters and games (such as blind man’s buff). Amazingly James Catnach, one of the most successful and prolific mass-market broadside publishers, produced his sheets on his father’s old wooden presses in the family home in Seven Dials, London.

Day 7

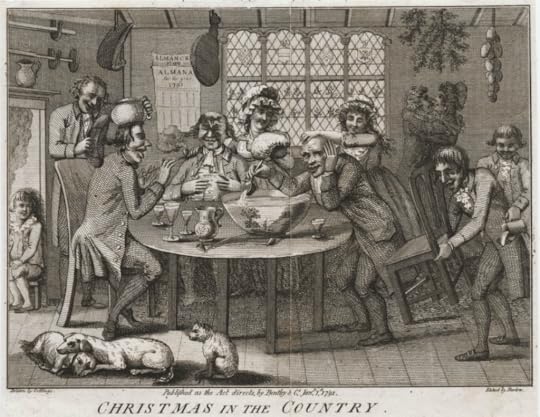

Samuel Collings, Christmas in the country (1791). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library

Samuel Collings, Christmas in the country (1791). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole LibraryA jolly country Christmas party but with not too much ribaldry. A couple in the back surreptitiously take advantage of the mistletoe while the others imbibe freely of the wassail bowl. A practical joker pours punch into a man’s pocket while the women tease the men about what lies under their wigs. It’s all pretty good-natured. Not much is known about Collings, who was a friend of Thomas Rowlandson.

Day 8

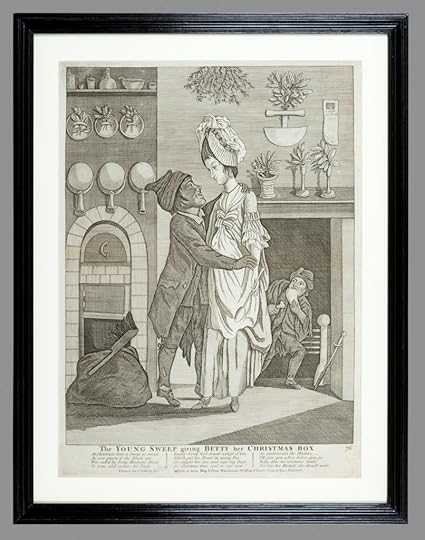

Anonymous, The Young Sweep Giving Betty Her Christmas Box (1770-1780). Courtesy of Winterthur Museum Collections

Anonymous, The Young Sweep Giving Betty Her Christmas Box (1770-1780). Courtesy of Winterthur Museum CollectionsVery depressing, this one. Housemaid Betty looks none too happy at the prospect of a ‘Christmas box’ from the sweep who, according to the rhyme printed below the image, has just had a glass of gin and has now ‘caught her fast’ under the mistletoe. Betty, apparently, is concerned that her mistress will be woken and therefore decides to make ‘no resistance’. I expect she would join in with the #MeToo campaign. The small, deformed climbing boy behind her devours some paltry Christmas fare.

Day 9

Edward Penny, Christmas Gambols (1796). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library

Edward Penny, Christmas Gambols (1796). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole LibraryBack to gambolling. Another genre scene of Christmas gambols and mistletoe, this time with a quote from Milton: ‘Whilst Romp loving Miss is haul’d about/ With gallantry robust’. Interestingly, the couple in the background seem to be minus feet. Edward Penny (1714–1791), a founder member of the Royal Academy of Arts, who was originally from Knutsford, Cheshire but moved on to London, was primarily known as a portrait and historical painter.

Day 10

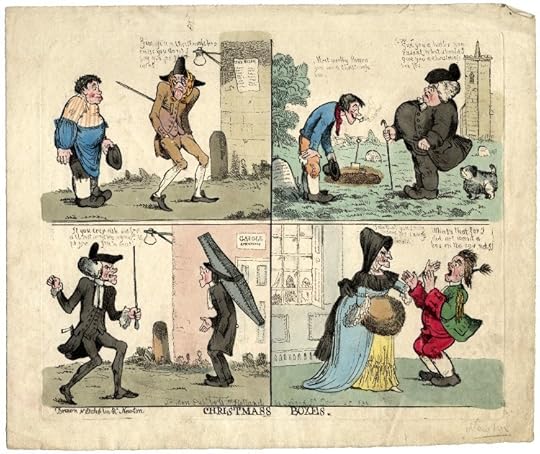

Christmas boxes (1794). Courtesy of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum

Christmas boxes (1794). Courtesy of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British MuseumSeveral grumpy bananas here. In this satirical print, four scenes show people trying to collect their Christmas boxes, only to be met with ill-temper and resistance. Unfortunately, I am unable to decipher the speech bubbles.

Day 11

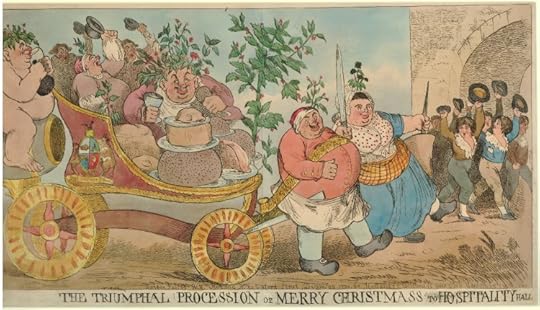

Richard Newton, The triumphal procession of Merry Christmas to Hospitality Hall (1794). Courtesy of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum

Richard Newton, The triumphal procession of Merry Christmas to Hospitality Hall (1794). Courtesy of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British MuseumRichard Newton (1777–1798) created this satirical print when he was only 17. His prodigious talent, alas, was snuffed out when he died of typhus at the tender age of 21. Newton’s depiction of the gluttony and excessive drinking during Christmas, in which gross men eating huge pieces of meat are pulled on a carriage by two fat people and followed by a naked man seated on a barrel, is original and rather bonkers. The scene is festooned with holly, which makes a change from mistletoe.

Day 12

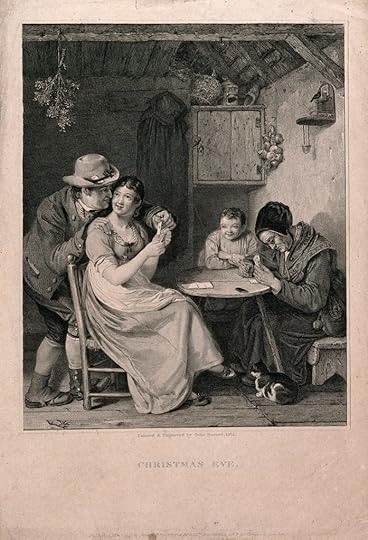

John Burnett, Christmas Eve (1815). Courtesy of the Wellcome Library

John Burnett, Christmas Eve (1815). Courtesy of the Wellcome LibraryFinally… A rural Christmas Eve genre scene, in which a woman plays cards with her weary mother or mother-in-law while her husband leans lovingly over her shoulder and her grinning child watches. A branch of hanging mistletoe ensures that the happy married couple are in the mood for later. John Burnett (c 1781–1860) was a Scottish-born engraver and painter.

And with that, I wish you all a fantastic Christmas and a Happy New Year!

The post 12 scenes of Christmas appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

December 12, 2017

1814: Murder or manslaughter? The trial of Mary Ann Adlam

After researching so many women who were sent to the gallows, 1 sometimes for non-violent crimes or for murders that arisen out of years of abuse, it was heartening to read this story about Mary Ann Adlam who stabbed her husband during an altercation at their premises in Bath Street, Bath, in 1814.

Sarah Ellis did not see the knife in her mistress’s hand, but when her master called her over, saying ‘Sarah, she has cut my coat.’

‘Yes, Mr Adlam, she has cut your coat,’ she replied.

He stretched out his arm and it was only then that she saw it was not just Mr Adlam’s coat that was cut.

‘Oh, Mr Adlam, there is blood!’

Mrs Adlam, who had fled the room after she stabbed her husband, now returned and tried to persuade him to go downstairs where she could tend to him, out of sight of any customers who might visit the shop. Eventually, he consented and she helped him down to the kitchen but he was in such a bad way that he lost his balance and together they fell down almost the entire flight of stairs onto the flagstones.

Mrs Adlam got him into a chair, and he began to lose consciousness. Sarah fetched a surgeon.

The Adlams lived on the premises of their straw hat shop in Bath Street, Bath. cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Graeme Smith – geograph.org.uk/p/718126

The Adlams lived on the premises of their straw hat shop in Bath Street, Bath. cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Graeme Smith – geograph.org.uk/p/718126Elizabeth Ann Gardner, a neighbour who had come in to help, witnessed an extraordinary scene: rather than berate his wife for mortally wounding him, Adlam was begging her for forgiveness. ‘Come to me, kiss me, forgive me and make it up,’ he was saying. Elizabeth Ann asked Adlam if he thought his wife had harmed him on purpose. He was adamant that she had not.

It was clear Adlam would not survive and indeed, shortly before eight o’clock that evening, two and a half hours after he was stabbed, he expired.

Sir Vicary Gibbs by an unknown artist. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Sir Vicary Gibbs by an unknown artist. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)On 20 August 1814 Mary Ann Adlam appeared at Wells Assizes before Sir Vicary Gibbs 2, the famously acerbic judge – he was nicknamed Vinegar Gibbs for his acid tongue. The courtroom was packed.

Wells Town Hall housed the assizes. cc-by-sa/2.0 – © David Dixon – geograph.org.uk/p/3781054

Wells Town Hall housed the assizes. cc-by-sa/2.0 – © David Dixon – geograph.org.uk/p/3781054Mary Ann was charged with murder and petty treason, the latter applicable only to wives for killing their lord and master (that is, for having the effrontery to upend the heaven-ordained hierarchy of society). 3

Mary Ann Allen and Henry Adlam were married at St James, Bath on 3 April 1808

Mary Ann Allen and Henry Adlam were married at St James, Bath on 3 April 1808Mary Ann Allen, a widow, and Henry Allen Adlam had been married six years but the relationship had turned sour. On the morning of Henry’s death, there was a violent scene between them, during which Henry had banged Mary Ann’s head against a wall. He left the house but when he came back several hours later, he was drunk.

Tea had already been served and the things had been taken off the table. Adlam insisted he should take his tea upstairs rather than in the kitchen, and rang the bell for the kitchen maid. Mary Ann wanted to use the table to line some bonnets and when she said so he struck her to the floor, called her a whore and beat her as she tried to get up.

Then he rushed next door to the shop and stood behind the counter. Mary Ann followed, saying ‘Can you prove me such [a whore]? Why do you live with me and let me support you?’ until Betty the maid dragged her away fearing that Mr Adlam would hit her again.

When Adlam came out from behind the counter towards Mary Ann, she went into the parlour and came back armed with a bread knife from the tea tray.

‘Will you call me that name again?’ she asked.

He did.

In court Sarah, who was now herself behind the counter, swore that she was momentarily distracted at the moment her mistress stabbed her master and did not see it happen – it was only when Mr Adlam said, ‘She has cut my coat’ that she looked up.

Witnesses were called to defend Mary Ann’s character. Mr Southey, a paper stainer of Philip Street, said she was ‘as human, good-hearted a creature as ever was born,’ Elizabeth Ann Gardner, the neighbour who came in to help, said she was ‘very virtuous, humane; a good sort of woman, very affectionate to her husband.’

The jury deliberated for a few minutes and returned a verdict of manslaughter. Mary Ann collapsed. Then Vicary Gibbs pronounced sentence: six months imprisonment. He added that he ‘should not add to her distress by enlarging upon her offence.’

Featured image: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Notes:

For my book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches. ↩Recorder of Bristol and Chief Justice of the Common Pleas ↩A servant who killed his or her employer or a cleric his ecclesiastical superior could also be charged with petty treason. Petty treason was abolished in 1828. ↩I have not been able to trace Mary Ann’s birth name and the fact that Henry’s middle name was Allen suggests that there may have been a family connection between Henry and Mary Ann’s first husband. ↩The post 1814: Murder or manslaughter? The trial of Mary Ann Adlam appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

November 28, 2017

Abduction and Rape in 18th-Century London: The Multiple Misfortunes of Charlotte Williams by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden

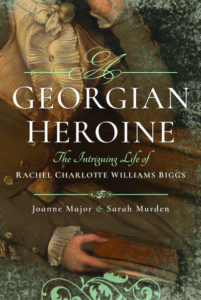

I am thrilled to host a post by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden, two stars of the Georgian Era blogging cosmos, whose supersleuthing on myriad fascinating subjects at All Things Georgian have earned them thousands of fans. Here they tell us about appalling crimes committed against Charlotte Williams, the subject of their third book, A Georgian Heroine: The Intriguing Life of Rachel Charlotte Williams Biggs, which is published this month by Pen & Sword.

I am thrilled to host a post by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden, two stars of the Georgian Era blogging cosmos, whose supersleuthing on myriad fascinating subjects at All Things Georgian have earned them thousands of fans. Here they tell us about appalling crimes committed against Charlotte Williams, the subject of their third book, A Georgian Heroine: The Intriguing Life of Rachel Charlotte Williams Biggs, which is published this month by Pen & Sword.

Some say whatever does not kill you makes you stronger, and that may have been the case with Charlotte.

Just how much misfortune could one girl suffer? Rachel Charlotte Williams, known as Charlotte and from a ‘middling’ but well-connected family who lived on Narrow Wall in Lambeth, 1 was abducted and raped not once, but twice! And both times it was by the same man, a wealthy neighbour who owned one of the timber yards which dotted the Lambeth shoreline.

Westminster Bridge and Whitehall from the Lambeth Shore, London, British School, 1775, Museum of London.

Westminster Bridge and Whitehall from the Lambeth Shore, London, British School, 1775, Museum of London.The timber merchant, named by Charlotte only as Mr H—, was obsessed by Charlotte who, at around 16 or 17 years of age, was a decade younger than her tormentor. The first abduction took place in the late 1770s, after Charlotte had been lured across Westminster Bridge to Mr H—’s lodgings in New Palace Yard, Westminster. There she was given coffee laced with laudanum before Mr H— burst into the room. During a brief struggle, Charlotte fainted, banging her head as she fell only to come to with her white dress covered in blood and the realisation that her body had been violated. Mr H—, alternately penitent or a madman, held her for several days until she was able to smuggle a message to her friends who came to her rescue.

New Palace Yard, Westminster by an unknown artist c.1793-1799, Government Art Collection. Mr H__’s house can be seen on the left hand side, just before the bow windows of the King’s Arms Tavern.

New Palace Yard, Westminster by an unknown artist c.1793-1799, Government Art Collection. Mr H__’s house can be seen on the left hand side, just before the bow windows of the King’s Arms Tavern.Charlotte’s father challenged Mr H— to a duel and the case was almost tried in a court of law but, at the last minute, a settlement was reached and Mr H— promised never to contact Charlotte again. He was no gentleman, however, and his word was clearly not his bond as he was soon pestering Charlotte, sending her letters promising the world if she would only consent to be his.

Fishing Boat at Fulham by John Thomas Serres, 1780, Brodie Castle.

Fishing Boat at Fulham by John Thomas Serres, 1780, Brodie Castle.Realising his words were falling on deaf ears, Mr H— hatched a plot to kidnap Charlotte from her home: she was lured, under false pretences, to the river, bundled into a boat and rowed up river to Parson’s Green, Fulham to be delivered into Mr H—’s clutches. He had taken the lease on Peterborough House, a mansion formerly owned by the Earl of Peterborough and there Charlotte was imprisoned for more than a year and repeatedly raped.

The novelist Samuel Richardson by Joseph Highmore, National Portrait Gallery. National Portrait Gallery, London.

The novelist Samuel Richardson by Joseph Highmore, National Portrait Gallery. National Portrait Gallery, London.The novelist Samuel Richardson had lived at Parson’s Green and one can be forgiven for thinking that Charlotte’s story sounds like one of his plotlines, for her experiences conjure those of the fictional Clarissa who was hounded by the rake Robert Lovelace and tricked into leaving her home with him. Lovelace believed that once Clarissa had lost her virtue, then she would have no option but to marry him; Mr H— held exactly the same premise, thinking that once Charlotte had submitted then she would become seduced not only by him but also by the luxuries he could offer and that she would willingly remain with him.

Robert Lovelace preparing to abduct Clarissa by Francis Hayman, Southampton City Art Gallery.

Robert Lovelace preparing to abduct Clarissa by Francis Hayman, Southampton City Art Gallery.While Clarissa lost the will to live and died a tragic heroine, Charlotte gathered her wits and triumphed over adversity. She escaped twice from Peterborough House only to later be held a prisoner in France during the revolution but then reinvented herself with remarkable aplomb. She would go on to be a memoirist, political pamphleteer, playwright and spy before instigating the nationwide celebrations for George III’s jubilee in 1809.

The identity of Mr H— together with the rest of Charlotte’s remarkable exploits are revealed in A Georgian Heroine: The Intriguing Life of Rachel Charlotte Williams Biggs, the bizarre but true story of an astounding woman persevering in a man’s world.

Notes:

On the south side of the Thames. ↩The post Abduction and Rape in 18th-Century London: The Multiple Misfortunes of Charlotte Williams by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

November 19, 2017

Five scenes of children playing

Our children are grown up and have left home but I keep out some of their toys just in case a child visits us. I miss shopping for children’s playthings. Perhaps, as we head for Christmas, that is why my thoughts turned to images of children playing in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

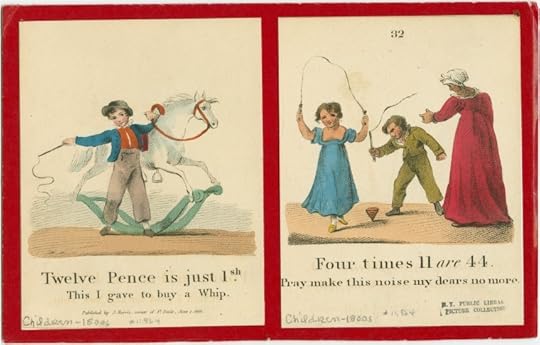

Health and safety standards have changed since this image from 1818: no one would let their child buy a whip. Skipping ropes and hobby horses still have their place, though. The children look lively and real, and on page 32 are clearly being quite naughty. It was published by John Harris (1756–1856), who operated out of 21 Ludgate Street, in the corner of St Paul’s Churchyard between 1805 and 1843.

Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Four times 11 are 44.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1818. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/it...

Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Four times 11 are 44.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1818. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/it...By contrast, a high society scene by Johann Zoffany, who introduced this genre of relaxed group portraits to England. John Peyto-Verney, 14th Lord Willoughby de Broke, his wife Lady Louisa North and three children. The toddler standing on the table taking her first step while one brother sneaks some bread and butter from the table and another rushes about with a toy horse.

Johann Zoffany, John, 14th Lord Willoughby de Broke and his Family (c. 1766). Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum.

Johann Zoffany, John, 14th Lord Willoughby de Broke and his Family (c. 1766). Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum.There are scant details about this next image, catalogued in the Wellcome Library only as ‘Children are playing a game with a bat and ball, others are skipping in the background’ (looks like early 18th century to me). The game is obviously cricket. Before the 18th century bats bats were often the shape of a modern hockey stick. One theory is that the game was first played using shepherds’ crooks.

Children are playing a game with a bat and ball, others are skipping in the background. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library

Children are playing a game with a bat and ball, others are skipping in the background. Courtesy of the Wellcome LibraryAh, the joys of a summers day: naked bathing in the river (boys only). This peaceful scene, of the banks of the Wensum in Norfolk was painted by John Crome (1768–1821), the son of a Norfolk weaver and, apart from fleeting visits to London, was based in Norfolk for his working life. He was employed as drawing master at Norwich grammar school.

John Crome, Boys Bathing on the River Wensum, Norwich (1817). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

John Crome, Boys Bathing on the River Wensum, Norwich (1817). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon CollectionFinally, my favourite, by Benjamin West (1738–1820). Families at the seaside on a blustery day at Margate, complete with children playing or paddling in the water, a toddler in the arms of its stalwart dad, bathing machines and aloft a mother looking (anxiously?) down at the scene.

Benjamin West, The Bathing Place at Ramsgate (c. 1788). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Benjamin West, The Bathing Place at Ramsgate (c. 1788). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.The post Five scenes of children playing appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

November 14, 2017

Benjamin Jesty: Pioneer vaccinator

The Church of St Nicholas of Myra at Worth Matravers, Dorset

The Church of St Nicholas of Myra at Worth Matravers, DorsetRecently I spent a weekend in Dorset with friends. On Saturday, while they were off yomping along the coastal path I took the opportunity to explore the Church of St Nicholas in Worth Matravers, a village perched near the cliffs, about four miles from Swanage. A famous pub, the Square and Compass, sits at high in the village and attracts most of the attention, for its award-winning beer and cider and fantastic live music and also for its eccentric little private museum of ammonites (this is the area known as the Jurassic Coast), coins, old buttons and clay pipes.

St Nicholas of Myra is one of the oldest churches in Dorset, with a Saxon entrance and Norman nave, tower, and windows. It is simple and beautiful, and it has that unmistakeable and – to me at least – nostalgic aroma of ancient stone and wood suffused with damp.

On sale in the church is a little green A5-sized booklet, The First Vaccinator: Benjamin Jesty of Yetminster and Worth Matravers and his Family by E. Marjorie Wallace, for £3 (proceeds to the church materials fund). 1 Ever on the lookout for Georgian stories, I snapped up a copy.

On sale in the church is a little green A5-sized booklet, The First Vaccinator: Benjamin Jesty of Yetminster and Worth Matravers and his Family by E. Marjorie Wallace, for £3 (proceeds to the church materials fund). 1 Ever on the lookout for Georgian stories, I snapped up a copy.

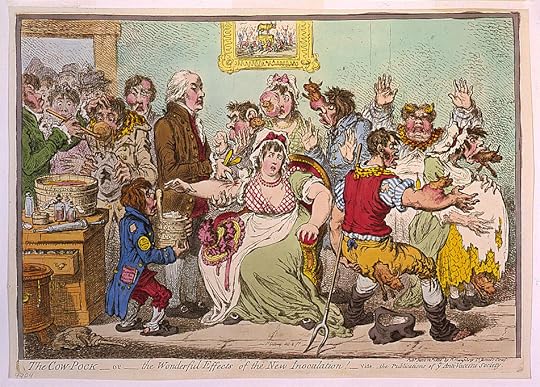

Wallace tells the story of farmer Benjamin Jesty (born circa 1736), who is buried with his wife in the churchyard and who performed the first documented vaccination, by applying pus from an infected blister on the udder of a cow in Chetnole to the arm of his wife Elizabeth (Jesty scratched her skin above the elbow). He also vaccinated his two toddler sons. The boys suffered no ill effects; Elizabeth ran a high fever but recovered. Unfortunately, the neighbours were horrified and Jesty was widely derided and insulted. Some people appeared to believe that people infected this way would grow horns and resemble cows.

The cow-pock – or – the wonderful effects of the new inoculation, James Gillray, 1802. Library of Congress LC-USZC4-3147

The cow-pock – or – the wonderful effects of the new inoculation, James Gillray, 1802. Library of Congress LC-USZC4-3147Jesty, who lived at Upbury in Yetminster 2 knew, as did many country people, that milkmaids never got smallpox because they contracted cowpox, a mild infection in humans, in the normal course of their work. Indeed, milkmaids were traditionally described as ‘fair’, not for their blonde colouring but because they were generally free of the pitted scars that many people were left with if they were lucky enough to survive the illness, which had a mortality rate of about a third. At the time Jesty vaccinated his family smallpox was raging in Yetminster and many villagers had died.

Unknown artist (early 19th century), Evening Milking. Courtesy of Bridport Museum Trust via Art UK

Unknown artist (early 19th century), Evening Milking. Courtesy of Bridport Museum Trust via Art UKThe practice of inoculation – using matter from a smallpox blister from an infected person to provoke a mild version of the disease in a healthy person – was well established in many countries, including Britain. It had some celebrity champions: smallpox to smallpox inoculation was given to George III and other Royal Family members and before that, in the early 18th century, it was supported by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu who witnessed its use in Turkey. It was a risky procedure, however, and sometimes resulted in serious illness, and even death.

Edward Jenner, a doctor, had been inoculated as a child of eight and had suffered greatly afterwards. He was convinced that cowpox held the answer to better inoculation, and in 1796, 22 years after Jesty’s experiment, he made a breakthrough. He infected eight-year-old James Phipps with matter from a dairymaid who had cowpox. It was the first human-to-human vaccination. Jenner tested the success of his procedure by attempting to infect James with smallpox (luckily the boy was indeed immune).

Benjamin Jesty, M.W. Sharp, 1805. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Courtesy of Wellcome Images. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

Benjamin Jesty, M.W. Sharp, 1805. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Courtesy of Wellcome Images. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0In 1805 Benjamin Jesty, who had since departed Yetminster and taken a larger farm at Downshay near Worth Matravers, was invited to London by the Vaccine Pock Institute for the purpose of having his portrait painted, his courageousness at last recognised. He was given 15 guineas and expenses and presented with a pair of gold-mounted lancets and a testimonial.

He died aged 79 on 16 April 1816 and was buried in the graveyard at St Nicholas. The family moved away to Woolbridge and when Elizabeth died, she was buried in Worth next to her husband.

Notes:

You can do no better than visit Worth Matravers to get a copy, but if that is not possible, Amazon has one at the time of writing. ↩The Rev Blakely Cooper, who features in my true-crime book The Disappearance of Maria Glenn, lived at Yetminster. ↩The post Benjamin Jesty: Pioneer vaccinator appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

October 15, 2017

Baby love: 6 Georgian infants

Following on from last month’s blog on breastfeeding, I have compiled a short visual tour of the lives of very young Georgians by way of sketches, paintings and cartoons. The depictions offer sharp contrasts in the fates of babies. All babies are vulnerable, in generations past much more so than now, but some were more vulnerable than others. No prizes for guessing what determined their life chances. All of these depictions are by men. Just saying. Genuinely, no more than that.

Let’s start at the top end of the social scale with this 1799 scene by William Redmore Bigg entitled Birth of the Heir showing the presentation of a newborn baby boy to his father and sisters. The older woman is probably the children’s grandmother. Here is not the place to debate the relative social positions of female and male children in genteel families but it’s probably enough to say that the father looks both misty-eyed and relieved (he’s been up half the night, as evidenced by his brandy, soup and sandwiches, and he has a son at last). For me there is an air of concern about the scene, leaving me to wonder whether all is well with the mother. The maid about to leave the room looks caringly on the new baby’s sisters and the grandmother seems a mite serious.

William Redmore Bigg, 1755–1828, Birth of the Heir, ca. 1799, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

William Redmore Bigg, 1755–1828, Birth of the Heir, ca. 1799, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon CollectionThis portrait of the West family, by Benjamin West, is much more formal. Betsy West, who has just given birth to her second child, wears a shimmering white gown matching the robes her baby wears, and gazes calmly on her child. The father of the child, Benjamin West, wearing lilac robes to balance his son’s outfit on the left, looks on from the right, while his father John and brother Thomas, both Quakers, sit in stolid homage. The painting was described by the Morning Chronicle as a ‘neat little scene of domestic happiness’ 1 but for me it’s curiously unfamilial: unnaturally silent and still, staged like a medieval nativity.

Benjamin West, 1738–1820, The Artist and His Family, ca. 1772, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

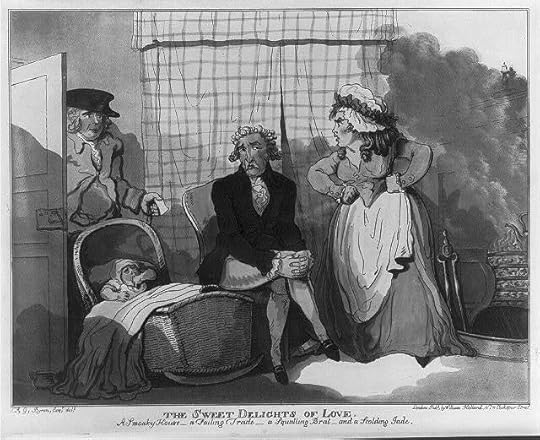

Benjamin West, 1738–1820, The Artist and His Family, ca. 1772, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon CollectionThere is no celebration of birth in Frederick George Byron satirical scene, entitled The Sweet Delights of Love and published at some time between 1788 and 1792. The baby here is decidedly unattractive, the mother is a termagant and the father’s trade is failing. Everything is going up in smoke.

F.G. Byron, The sweet delights of love. Courtesy of Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003675436/

F.G. Byron, The sweet delights of love. Courtesy of Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003675436/This next couple are much happier. In Thomas Rowlandson’s Four O’Clock in the Country a chubby child sleeps soundly and contentedly as his excessively déshabillée mother helps his father get ready to leave on a pre-dawn hunt. The baby’s relaxed pose and rounded limbs are of a piece with its parents’ obvious pleasure in the delights of conjugal love.

Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827), Four O’Clock in the Country, (c 1788-90), Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827), Four O’Clock in the Country, (c 1788-90), Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon CollectionMoving down to the bottom of the social scale now, here is George Romney’s sketch of a prison scene, which is like something out of Hell, which indeed was Romney’s point. Unnoticed in the mêlée is a child curled up in the uncertain protection of its mother’s armpit. Extremely stylised, almost 20th-century in its reduction of the human objects to geometric shapes, it vividly conveys the pain and degradation of incarceration. A baby who can be only be utterly innocent of any crime is not exempt from punishment for its parents’ crimes. 2

George Romney, 1734–1802, British, Prison Scene, undated, Brown wash and graphite with pen and brown ink on medium, moderately textured, cream laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Yale Art Gallery Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Richardson Dilworth, B.A. 1938

George Romney, 1734–1802, British, Prison Scene, undated, Brown wash and graphite with pen and brown ink on medium, moderately textured, cream laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Yale Art Gallery Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Richardson Dilworth, B.A. 1938To finish, I give you Joseph Highmore’s Angel of Mercy, currently on display at The Foundling Museum in London as part of their Basic Instincts exhibition 3. The painting, in which a desperate mother is averted from strangling her newborn child is averted from committing murder by an angel, is probably a study for a larger work intended for the Foundling Hospital but never created. According to Jacqueline Riding, who curated the exhibition of Joseph Highmore’s work, the subject matter was probably too shocking for contemporary audiences.

Joseph Highmore (1692–1780), The Angel of Mercy, ca. 1746. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Joseph Highmore (1692–1780), The Angel of Mercy, ca. 1746. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection The punishment of women who kill their babies is one of the subjects I cover in my new book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches, which will be published next month and is available for pre-order here.

The punishment of women who kill their babies is one of the subjects I cover in my new book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches, which will be published next month and is available for pre-order here.

Notes:

25 April 1777. ↩The sketch is one of a series of studies celebrating the work of the philanthropist and social reformer John Howard (1726-90) against the disease and desperation that was rife in prisons during the 18th century. ↩Ends 7 January 2018. ↩The post Baby love: 6 Georgian infants appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

October 12, 2017

Exhibition: Pablo Bronstein: Conservatism, or The Long Reign of Pseudo Georgian Architecture

One of my aspirations is to live in a Georgian house. Perhaps my love of the 18th century stems from an early experience. Aged 11, I went with my mother to visit one of her work colleagues in her tiny flat in a Georgian terrace in King’s Cross. It was probably not authentically “Georgian”. The walls and ceiling were white and the floorboards painted. On a small, elegant sofa were placed one or two colourful cushions. It was extremely minimalist. Nevertheless, I fell in love. It was the proportions – of the rooms and particularly of the windows – that sealed the deal.

One of my aspirations is to live in a Georgian house. Perhaps my love of the 18th century stems from an early experience. Aged 11, I went with my mother to visit one of her work colleagues in her tiny flat in a Georgian terrace in King’s Cross. It was probably not authentically “Georgian”. The walls and ceiling were white and the floorboards painted. On a small, elegant sofa were placed one or two colourful cushions. It was extremely minimalist. Nevertheless, I fell in love. It was the proportions – of the rooms and particularly of the windows – that sealed the deal.

Clearly, I am not the only one who feels this way. For an exhibition at RIBA in London, Pablo Bronstein, a British-Argentinian artist, has explored our love of Georgian architectural style, its lines and flourishes executed with varying degrees of success. Fifty of Bronstein’s drawings of faux Georgian or Georgian-influenced buildings, fetchingly and rather wittily presented in faux Georgian frames are juxtaposed with rarely-seen Georgian plans and drawings (yes, actual ones) of buildings, cuttings from the Architects Journal and pages from 18th-century architects reference works.

What I loved about this understated display was that the information boards are sober and informative, if a little high-faluting at times, entirely consistent with its serious architectural setting. Bronstein’s occasional captions (he has not annotated all the works), however, are something else. I wish I had photographed them (a security person was looking at me rather sternly so I didn’t dare). You cannot say they are not serious or sincere but often they are wonderfully droll, ironic and dry. I couldn’t help but laugh out loud at some of them.

What I loved about this understated display was that the information boards are sober and informative, if a little high-faluting at times, entirely consistent with its serious architectural setting. Bronstein’s occasional captions (he has not annotated all the works), however, are something else. I wish I had photographed them (a security person was looking at me rather sternly so I didn’t dare). You cannot say they are not serious or sincere but often they are wonderfully droll, ironic and dry. I couldn’t help but laugh out loud at some of them.

It took me about 40 minutes to get round the rooms (there are 5 or 6). The refined cool atmosphere of the building is ideal for respite from the frenzy of West End shopping.

Pablo Bronstein: Conservatism, or The Long Reign of Pseudo Georgian Architecture

RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects)

66 Portland Place

London W1A 1AD

FREE

Monday – Sunday 10am to 5pm and every Tuesday 10am to 8pm

Closes 11 February 2018

The post Exhibition: Pablo Bronstein: Conservatism, or The Long Reign of Pseudo Georgian Architecture appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

October 7, 2017

Pre-order your copy of Women and the Gallows 1797-1837

With only six weeks or so to publication date, here is your timely reminder to get your pre-orders in for Women and the Gallows, a unique look at the 131 ‘unfortunate wretches’ in En gland and Wales who were hanged for crimes as wide-ranging as stealing sheep, burning hayricks, fraud, infanticide and husband murder.

With only six weeks or so to publication date, here is your timely reminder to get your pre-orders in for Women and the Gallows, a unique look at the 131 ‘unfortunate wretches’ in En gland and Wales who were hanged for crimes as wide-ranging as stealing sheep, burning hayricks, fraud, infanticide and husband murder.

Most of these women were extremely poor and living in desperate situations. Some were mentally ill. A few were innocent. And almost all are now forgotten, their voices unheard for generations.

Including

Mary Morgan – a teenager hanged as an example to others.

Mary Bateman – a ‘witch’ who duped her neighbours out of their savings and went on to murder.

Harriet Skelton – hanged for passing counterfeit pound notes in spite of efforts by Elizabeth Fry and the Duke of Gloucester to save her.

Eliza Ross – the last ‘burker’.

Charlotte Long – executed for setting fire to a hayrick.

Plus a unique chronology of all 131 women and their crimes.

ORDER NOW

Introductory offer £15.99

The post Pre-order your copy of Women and the Gallows 1797-1837 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

September 26, 2017

Breast is best but what were the alternatives in the long 18th century?

Paul Sandby (1731-1809), The wife of Bob Nunn, Keeper at Sandpit Gate, circa 1755. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

Paul Sandby (1731-1809), The wife of Bob Nunn, Keeper at Sandpit Gate, circa 1755. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017Breastfeeding, that most natural of processes, was not always encouraged in the 18th and early 19th centuries, nor indeed was it always possible. Genteel women were told it was harmful to eyesight and that it ruined their figures. In any case, for much of the 18th century, elaborate and impenetrable fashions might make the breast inaccessible to a baby at dinner or when socialising at the theatre. The later ’empire style’ was more suitable, and by then breastfeeding was being actively promoted to the middle classes.

The fashionable mamma, – or – the convenience of modern dress, James Gillray, 1796. © The Trustees of the British Museum

The fashionable mamma, – or – the convenience of modern dress, James Gillray, 1796. © The Trustees of the British MuseumWhen a woman could not or would not breastfeed, the most obvious solution was to find a surrogate or wet nurse, a woman who had either recently given birth, who could supply enough milk for two babies or who was still in milk after weaning her own child.

A wet nurse breast feeding the Duke of Burgundy, grandson of Louis XIV. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

A wet nurse breast feeding the Duke of Burgundy, grandson of Louis XIV. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0It was standard practice to hand royal or high-born babies straight to a nurse, who often had special status within the household. In 1766, after careful vetting, Mrs Muttlebury, a mother of four, was employed by Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, to feed her first daughter, Princess Charlotte. Mrs Muttlebury’s reward was substantial: £200 per annum for life. Apart from the salary, she would also have benefited from the contraceptive effect of prolonged suckling. Queen Charlotte, on the other hand, had to return to the task of producing more royal progeny as quickly as possible. She had 15. Queen Victoria, who bore nine without much enthusiasm for pregnancy or indeed children, famously did not breastfeed, thinking it a repulsive and animalistic practice suitable only for the lower classes.

Middle-class women who assisted their spouses in their businesses, the wives of wives of merchants, lawyers, and doctors for example, also may not have breastfed because it was less expensive to employ a wet nurse than to hire someone to run their husband’s affairs in their stead. However, there was a growing feeling towards the end of the 18th century, partly driven by the involvement of doctors, invariably men, in pregnancy, birth and babies, areas of life traditionally dominated by women, that it was preferable for children to be fed by their natural mother.

A woman breast feeding her child, 1810. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

A woman breast feeding her child, 1810. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0Hugh Smith, Physician to the Middlesex Hospital, wrote that ‘nothing but a strange perversion of human nature could first deprive children of their mother’s milk… milk is a natural support which the great Author of our being has provided for our infant state.’ He bemoaned the feeling against women suckling their own babies. He warned that failure to breastfeed could produce tumours and other cancers. He was not keen on wet nursing and warned against the dangers of allowing ‘a strange woman’ to suckle a child, fearing that diseases – the king’s evil, watery gripes, rickets – could be imbibed at the breast and that a wet nurse might be tempted to abandon or farm out her own child in order to take wet nursing employment. 1

In general wet nurses did not have a good reputation and were distrusted by people like Dr Smith for their ignorance and their tendency to administer dangerous opiates such as Godfrey’s Cordial (nicknamed Quietness for obvious reasons).

A drunken wet-nurse about to give the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) a drop of alcohol as a horrified Queen Victoria and Prince Albert burst in on the scene. Circa 1842. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

A drunken wet-nurse about to give the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) a drop of alcohol as a horrified Queen Victoria and Prince Albert burst in on the scene. Circa 1842. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0Of course, no matter the rank of a family, if the mother died around the time of birth, feeding the newborn became an immediate problem. If a wet nurse was not available or not desirable what could you do? Smith felt the best substitute was artificial or hand feeding with cow’s milk, which should be boiled and sweetened with sugar.

Silver pap boat made by William Sheer. London, England, 1767. Credit: Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

Silver pap boat made by William Sheer. London, England, 1767. Credit: Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0Some care-givers supplemented artificial feed with pap, which consisted of bread soaked in water or milk, delivered using a pap boat with a hollow stem which allowed the pap (or pananda which was cereal cooked in broth) to be blown down the child’s throat. Along with linen pouches, horns, clay jugs, pickled cow nipples and other vessels used to feed babies, these objects, difficult to clean and never sterilised, were the frequent source of infection. About a third of infants who were artificially fed died during their first year. The forces of the Industrial Revolution, pushing rural families to the cities, affected breastfeeding. Casual and reciprocal wet nursing between friends and neighbours had existed for centuries, allowing women to work away from home in the fields. Now urban women, who were more likely to have to work outside the home to supplement their families’ incomes, found that it was difficult, if not impossible, to breastfeed on demand. Babies were often farmed out in the countryside to impoverished women where they would either be wet nursed or fed with cow’s milk or pap. Unsurprisingly they suffered a high rate of mortality.

Stevens, E. E., Patrick, T. E., & Pickler, R. (2009). A History of Infant Feeding. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 18 (2), 32–39. http://doi.org/10.1624/105812409X426314

Wickes, I. G. (1953). A History of Infant Feeding: Part III: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Writers. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 28 (140), 332–340.

Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches

In the last four decades of the Georgian era, 131 women in England and Wales were hanged at the gallows. What were their crimes? And why, unlike most convicted felons, were they not reprieved?

Available to pre-order now at Pen & Sword (introductory price £15.99), Amazon US

Notes:

Smith, H. (1796). Letters to Married Women, on Nursing and the Management of Children. Philadelphia: Mathew Carey (‘2nd American edition’) ↩The post Breast is best but what were the alternatives in the long 18th century? appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

September 23, 2017

What happened during the Georgian harvest?

After an indifferent and short summer, autumn, my favourite season, has arrived. Usually I am looking forward to all the mists and mellow fruitfulness but this year I am troubled by talk of shortages of food through a lack of workers to bring in the harvest – farming still relies on workers.

My thoughts turned to farming in the 18th and 19th centuries and specifically to the business of bringing in the corn.

The harvest was not only an important festival in the religious calendar but it was an opportunity for a major end-of-season celebrations, a time for the community to come together and work together. Activities need not always meet approval. Charles Vancouver, who surveyed Devon for the General View series in 1808 (an initiative of the Board of Agriculture), complained that the harvest encouraged ‘practices of so disorderly a nature, as to call for the strongest mark of disapprobation, or at least a modification of their pastime after the labours of the day.’ 1

‘Labour’, Engraving by J. Cousen after J. Linnell. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

‘Labour’, Engraving by J. Cousen after J. Linnell. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0In Devon, Vancouver wrote, ale and cider is provided to the reapers at eleven o’clock in the morning. There was more drink at dinner time, along with ‘the best meat and vegetables’ (presumably to keep the strength of the reapers up). At five there was a tea of buns and cakes set out under the trees, and the day ended with a game. A small sheaf was set up as a target at which the workers aimed their reap-hooks. The farmer provided supper in a barn, with more ale and cider. The carousing went on until the small hours. The following day, the reapers resumed or moved on to the next farm.

The harvesters would work in rows, with an advance team (of men) scything the wheat, followed by men and women gathering it into sheaves with a sickle or reap-hook. The sheaves were stacked and left to dry.

According to Vancouver reapers in parts of Devon were not paid except in kind: food, drink and the opportunity for a party as well as a standing invitation to the farmer’s house at Christmas for more hospitality. He sniffily described the behaviour of the reapers during this time as ‘assimilated to the frolics of a bear-garden.’

For the same General View series of agricultural surveys, Thomas Batchelor looked at Bedfordshire where the reaping was done by ‘acre-men’, who could earn £6 5s in five weeks. 2

Unsurprisingly, autumn was seen as a time of romance, an opportunity for intimacy between men and women who worked together closely in the fields.

‘Hence from the busy joy resounding fields…’ Richard Corbould, Autumn, (undated). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

‘Hence from the busy joy resounding fields…’ Richard Corbould, Autumn, (undated). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.Before the ripened field the reapers stand

In fair array; each by the lass he loves

Thomson’s Seasons – ‘Autumn’

After the reaping, the sheaves were brought into the barn, opened and laid out to be threshed with a flail to separate the grain (edible) from the chaff (used for animal feed). This was an exhausting process requiring intense physical strength. The contemporary spelling thrashing gives an idea of the force involved. Vancouver says that in Devon, unlike the reapers, the threshers were paid.

The process of threshing was considerably speeded up with the introduction of mechanisation. Vancouver described what he called a ‘very good’ water-powered threshing machine belonging to Mr Vinn at Payhembury, which could thresh, winnow, grind and could be adapted to crush apples and shell clover seeds. There were horse-powered versions and, later, steam.

Two threshing machines (1810). Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. http://wellcomeimages.org. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

Two threshing machines (1810). Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. http://wellcomeimages.org. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0Naturally, the machines required less physical strength than manual threshing, which meant that women and children could be employed in greater numbers. Some saw this as an advantage because the men could be directed to more arduous tasks. In Vancouver’s opinion there was actually more employment rather than less and everyone, from the workers to the parish authorities, would benefit.

Unsurprisingly, the workers did not agree with this. They knew that their role overall would be diminished and reacted with anger and threats, and sometimes with riot and machine-breaking. The introduction of threshing machines was a contributory factor in the rural disturbances known as the Swing Riots of the 1830s.

After threshing, the reeds were gathered up and the corn and chaff swept into a pile to be winnowed. Winnowing could be done manually using a ‘fan’.

Le vanneur (The Winnower), Jean-François Millet – The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH., Public Domain, Link

Le vanneur (The Winnower), Jean-François Millet – The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH., Public Domain, LinkSometimes a machine was used. This was placed in the middle of the barn whose the doors were kept open to create a draught. The grain and chaff were poured into the machine, which ejected the chaff into the farmyard and grain dropped into a bucket at the side, to be packed into sacks and sent to the miller.

Winnowing machine, by Rasbak – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Winnowing machine, by Rasbak – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, LinkThe last stage was combing the reed. The loose straw and chaff were removed with a large wooden framed comb with iron teeth and the reed dried and used for thatching the roofs of barns and houses and also for protective covers for hayricks.

The ancient celebration of the harvest took place during the Harvest Moon, originally a pagan celebration (the earliest church service for harvest has been traced to 1843 at Morwenstow in Cornwall).

Samuel Palmer (1833). The Harvest Moon. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Samuel Palmer (1833). The Harvest Moon. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Notes:

Vancouver, C. (1808). General View of the Agriculture of the County of Devon; with Observations on the Means of Its Improvement. Drawn Up for the Consideration of the Board of Agriculture, and Internal Improvement. London: Richard Phillips. Vancouver, a land valuer, wrote several volumes for the General View series. ↩Thomas Batchelor (1808). General view of the agriculture of the county of Bedford: Drawn up for the consideration of the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement. London: Richard Phillips. Batchelor was a farmer. ↩The post What happened during the Georgian harvest? appeared first on Naomi Clifford.