Naomi Clifford's Blog, page 5

October 12, 2018

15 October 1815: A fake fight results in catastrophe at Sadler’s Wells

Theatres have been much on my mind lately. When I have an odd moment, I transcribe 18th and 19th-century playbills for the LibCrowds project (there is something soothing about a repetitive task that requires accuracy) and I recently gave a talk on the first night of the Royal Coburg theatre, now known as the Old Vic, of course, as it features in my book The Murder of Mary Ashford.

Neptune and his horses: a spectacular at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London, 1808-1810. The pit had backless benches; the gallery was at the back and was standing.

On the night of Thursday 15 October 1807, John Dobson, his wife, young son and three or four friends were in the pit at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in Islington, north London. Although the theatre was exceptionally crowded – it was a benefit night and about 2,000 people were in the house – the audience was good natured and well behaved. Just before the closing scene, at about about ten o’clock, however, Dobson noticed a group of eight or ten people, two of them smartly dressed ‘vulgar women’, join the throng. Some of the men started to push each other about. Dobson, standing on a bench in order to see the stage thought there was something about their behaviour. It seemed to him that the quarrel was staged.

Perhaps a cry of ‘Fight! Fight!’ went up. Perhaps someone misheard it as ‘Fire! Fire!’ This is how many people later explained the panic that spread through the audience and the subsequent rush to leave the building. Seeing what was happening, one of the actors, George Smith, one of the actors, tried to shout to the audience that there was no fire. He was joined by Mr Reeves, one of the owners of the theatre, who got up on stage with a ‘speaking-trumpet’ to do the same, but no one could hear them above the shouting and screaming. The whole house was in chaos, with people jumping 30 feet down from the gallery to the pit to escape the non-existent flames and musicians lifting people over the orchestra onto the stage.

Outside in the yard, those who had escaped were discovering that there had been no fire and heading back inside to find their companions. But their way was blocked by a stream of people still coming down the stairs from the gallery. The result: a logjam. Then someone tripped on the stairs and people started falling on top of each other. It must have happened in moments: a pile of bodies at the foot of the stairs.

In the pit, Dobson, who had seen no fire and nor smelled smoke, had persuaded his party to stay put until the crowd had dispersed.

Sadler’s Wells (1804), John Greig after Samuel Prout. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

There is a terrible irony about the disaster, which arose from fear of flames: Sadler’s Wells’ name remembers the water source (thought to have healing powers) it was built over and in the winter of 1803 the manager, Charles Dibdin the Younger, installed a large water tank (80 by 30 feet) at stage level and filled it from the nearby New River. The following season he staged the astonishing spectacle The Siege of Gibraltar, during which scale models of ships were moved around the ‘sea’ by boys wearing ‘thick duffel trousers’ and encouraged with brandy.

A contemporary observer wrote:

It acted like electricity, a pause of breathless wonder was succeeded by stunning peals of constant accclaimation; and when the Ships sailed down, in regular succession, ‘rolling on their way’, their sails shifted in the wind; their colours and pennants flying; and their ordnance, as they passed the front of the stage, firing a grand salute to the Audience, the latter seemed in an extasy.

Sadler’s Wells came to be known as ‘the aquatic theatre’.

Charles Dibdin the Younger in 1819. Courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Dibdin was trying to improve Sadler’s Wells’ reputation for attracting drunken loutish audiences. Not only was he offering the escorts back into central London after dark (Islington was then still a rural suburb) but he started hiring famous performers such as the Shakespearian actor Edmund Kean and the clown Joseph Grimaldi.

After the panic was over, about 30 bodies were brought into the proprietor’s room, 18 of whom were obviously dead, killed by suffocation or crushing. Mr Sharpe, a surgeon from St Bartholomew’s who happened to be in the audience, worked hard to save the other 10 or 12 with other medics who had been sent for. One victim was ‘an athletic man’ who came round after he was bled, only to find his wife lying dead next to him. ‘The poor fellow became frantic, and was carried away in a state of desperation,’ according to some reports.

The injured were removed quickly: a sailor from The York, who had been severely bruised, to The London Hospital in Mile End Road; five others to Sir Hugh Middleton’s Head, opposite the theatre; and four to Islington Spa. Some had broken bones but all of them are thought to have recovered.

Four of the ‘ruffians’ who had started the fake fight were arrested. John and Vincent Pierce, Mary Vine and Elizabeth Luker were taken before the bar at Hatton Garden. Despite their apparent callousness (when they were informed that 18 people had died as a result of their ‘riot’, they were alleged to have said something along the lines of ‘Well, we don’t care. We can’t be hanged for it’) they could not be charged with a felony crime. Their actions were intended to distract the audience while they picked pockets, not to result in death.

The Sir Hugh Middleton’s Head, opposite Sadler’s Wells Theatre. Credit: Wellcome Collection

A mob gathered outside the theatre and the Clerkenwell Volunteers were called in to control them, while inside the theatre in three separate rooms the 18 bodies (‘horribly disfigured and contorted’) were being ‘decently laid out upon temporary tables’ and labelled with their names and addresses, ready for the Coroner. They were overwhelmingly young people and included at least five children aged 16 or under:

John Ward, 16, an errand boy, of Glasshouse Yard, Goswell Street, was identified by a 17-year-old friend Mary Ann Pede, who lived next door and who had gone with him to the performance. They became separated after the cry of ‘Fire!’ went up.

Lydia Carr, of 23 Peerless Pool, City Road, identified by her brother John

Elizabeth Margaret Ward, 21, of 20 Plumtree Court, Bloomsbury, was identified by her mother. Elizabeth had gone to the theatre with her sister and ‘a young man’ who were too injured to attend the inquest.

Benjamin Price, 12, of 33 Lime Street, Leadenhall Street

Joseph Groves, a servant to Mr Taylor of Hoxton Square, identified by his brother John

Edward Clements, 13, of Paradise Court, Battlebridge, identified by his father John.

John Labdon, 20, of 7 Bell Yard, Temple Bar

John Greenwood, an apprentice, of King Street, Hoxton Square, identified by his employer, John Simmons

Sarah Chalkey, of 24 Oxford Road, identified by Mr Monk, a War Office messenger.

Rhoda Ward, 16, of The Crooked Bill, Hoxton, identified by her mother Martha, who had been in the gallery with her daughter.

Mary Evans, of Hoxton Market, identified by her son William and sister Sarah.

Caroline Terrell (sometimes given as Twitcher), an ‘unfortunate woman’, who was pregnant, of Plough Court, Whitechapel, identified by Class Jacobs, a Swedish sailor from The York, who had been with her for three days before they went to the theatre together.

James Philliston, 30, of White Lion Street, Pentonville

Rebecca Sanders, aged 9, a domestic servant, of 12 Drapers Buildings, London Wall, identified by her father. She had gone to the theatre with her mistress to help mind the baby.

Rebecca Ling, of 5 Bridge Court, Cannon Row, Westminster, identified by John Myers

Richard Bland, 28, of 13 Bear Street, Leicester Fields

Charles Judd, 20, of Artillery Lane, Bishopsgate Street

William Pincks, 17, of Hoxton Market, identified by his mother Mary Pincks

Most of the dead were found to have little money and no valuables on them. The coroner’s clerk retrieved only 20 shillings (£1) from them in total. As they were, in the main, people of slender means this was not perhaps surprising, but there remained a suspicion that the bodies had been robbed.

George Hodgson, the Middlesex Coroner, arrived at ten ‘clock and convened the inquest in Mr Dibdin’s drawing room. Then the jury viewed the bodies, the stage and the gallery stairs and were satisfied that no fire had occurred. The friends and relatives of the dead gave evidence as did actors and employees of the theatre. At the conclusion, Mr Hodgson instructed the Jury, who duly declared that the dead had been killed ‘casually, accidentally and by misfortune’. Hodgson praised the management of Sadler’s Wells who had acted ‘most becomingly’ and had done everything they could to prevent the panic.

The four prisoners appeared at Middlesex Magistrates Court. Mary Vine was remanded to Clerkenwell prison and the others were bailed.

The following day, Sunday, the bodies were taken away for burial. Dibdin, who paid the funeral expenses of the ‘unfortunate’ Caroline Terrell as no relatives came forward to claim her body, was plagued with false claims for expenses.

On 2 November the theatre reopened for a two-night benefit for the relations of the victims.

In December, John and Vincent Pierce and Elizabeth Luker were sentenced for exciting a riot and disturbance at Sadler’s Wells Theatre. After Mr Mainwaring lamented their ‘outrageous conduct’ and the terrible consequences of it – ‘whole families plunged in irremediable ruin, by the loss and protection of those who were their natural protectors and guardians – he gave John six months, Vincent four and Elizabeth 14 days imprisonment.

Acting magistrates committing themselves being their first appearance on this stage as performed at the National Theatre Covent Garden. Sepr 18 1809. © British Museum, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The danger of fire in theatres was real. Ideas for improved safety, suggested by journalists rather than by the authorities, included having ready-made banners at hand to tell people that the theatre was not on fire, and making sure that there was enough space for fleeing people to congregate without blocking exits for other people. However, nothing changed and nearly a year after the Sadler’s Wells tragedy, Covent Garden Theatre was destroyed by fire with the loss of 30 lives, and Drury Lane Theatre burnt down in March 1809.

Commotions among theatre audiences were a regular occurrence. When Covent Garden Theatre reopened in 1809 the audience took the management’s decision to raise ticket prices as an outrageous infringement of their rights and three months of riots ensued, during which, it is said, 20 lives were lost. The violence only ended with the manager, John Philip Kemble, reverting prices and apologising.

Sources

The Annual Register for the year 1807 (1809). London: W. Otridge and Son et al.

McPherson, H. (2002). Theatrical Riots and Cultural Politics in Eighteenth-Century London. The Eighteenth Century, 43(3), 236-252. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41467906

Remington, S. (1982). Three Centuries of Sadler’s Wells. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 130 (5312), 472-481. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41373417

Morning Chronicle, 26 October 1807, 3B.

Morning Post, 17 October 1807, 3C; 19 October, 3D; 24 October 1807, 4B; 9 December, 4B.

Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 17 October 1807, 3B; 19 October, 3B.

The post 15 October 1815: A fake fight results in catastrophe at Sadler’s Wells appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

September 10, 2018

Mademoiselle Parisot’s shocking pirouettes put London in a spin

A confluence of thoughts, about how women are always criticised for whatever they wear and how incomers are always blamed for rises in bad behaviour, prompted this look at the career of Mademoiselle (or Madame) Parisot, a dancer who shocked and enthralled a generation of London theatre-goers. It also chimes nicely with my earlier blog on 18th-century caricatures of female fashion.

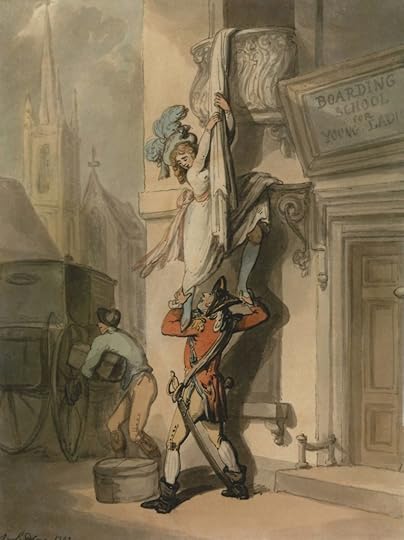

Isaac Cruikshank, A peep at the Parisot with Q in the corner (1796). Mademoiselle Parisot displays her risqué style of dancing. ‘Q’ in the top right is the Duke of Queensberry (1725-1810), whose mistresses included several opera singers. Parisot is shown wearing pink undergarments.

The bishop took the present occasion to observe, that the French rulers, while they despaired of making any impression on us, by the force of arms, attempted a more subtle and alarming warfare, by endeavouring to enforce the influence of their example, in order to taint and undermine the morals of our youth.’ 1

Shute Barrington, Bishop of Durham, speaking in the House of Lords, told the assembled that he knew who posed the greatest threat to British culture — ‘[French] female dancers, who, by the allurements of the most indecent attitudes, and most wanton theatrical exhibitions, succeeded by too effectually loosening and corrupting the morals of the people.’

The ‘wanton theatrical exhibitions’ Bishop Barrington had in mind were those where the dancer pivoted en pointe, one leg extended and raised just over 90 degrees, a position affording obvious opportunities for voyeurism and made possible only by the invention of the pointe shoe, a flat ballet pump with a block of wood in the toe, tied on the foot with ribbons, by Charles Didelot in 1795. 2

Mademoiselle Parisot, who worked frequently with Didelot and his wife Rose, not only pirouetted beautifully but also wore flimsy revealing dresses with extremely decolletée necklines. She was sometimes depicted in cartoons with one breast exposed; whether this was by design or by accident is not known.

Bishop Barrington was not the only one to be outraged by Parisot’s style. George Hanger, 4th Baron Coleraine, a reformed roué who was now content to be a mere eccentric, went one step further. He wrote about her — somewhat alarmingly — in his memoirs: 3

I most sincerely wish that Satan would renew his frolics, and appear once more, in propria persona, on our stages; but particularly at the opera-house, amongst those wicked and immodest dancers, that they might be seized with distraction; for I much fear, nothing else will prevent a continuation of their immoral and indecent gestures: and that wicked jade, Mademoiselle Parisot, would meet with no more than her just deserts, if he were to give her ten or a dozen hearty smacks with his tail, to make her remember those attitudes, so repugnant to modesty, which she so wantonly displays. This is my most devout wish…

Robert Newton, A Peep at the Parisot! (1796). The figures on the left are probably Shute Barrington, the Bishop of Durham, and the Duke of Queensberry. Parisot is shown wearing shoes with heels. In reality, standing en pointe required pointe shoes, which were flat.

Parisot made her London debut aged 18 or 19 on 1 February 1796 at the King’s Theatre in a production of Piramo e Tisbe and immediately caused a sensation. Critics praised her for her ‘face full of expression’ and ‘beautiful figure’, but it was her balance (‘positively magical’) and the one-leg-up pose that entranced them. It meant that she could turn ‘her person… almost horizontal while turning as on a pivot on her toe. From the specimen of last night, she is a great acquisition to the Theatre; and if her talent for acting be equal to her dancing and figure, they will be able to give us ballets in good stile.’ The caricaturists were quick to seize on the comic and erotic possibilities of Parisot’s performances. Robert Newton, Isaac Cruikshank and James Gillray produced scurrilous prints poking fun at both her provocative display and her lascivious observers.

But Parisot was not just about dirty dancing. She also developed a series of dances that she made her own. One style was to strike a series of attitudes similar to Emma Hamilton’s famous poses resembling those seen in classical artworks and old paintings, and representing famous mythical and historical stories and characters. The dancer’s skill was to transform from one figure into another.

Pietro Antonio Novelli, The Attitudes of Lady Hamilton. National Gallery of Art (USA). Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund 1988.

Madame Parisot is not one of those elegant dancers who captivate by neatness of step; … her merit consists in the astonishing display of attitude, of which nothing more various and ingenious has even been exhibited; her figure, which is tall, and finely proportioned, seems exactly suited to her style of dancing. She possesses considerable taste, and, by singular adjustment of her arms, which are to her what a rope-dancer’s balance is to him, she indulges in all the fantastic positions which art and fancy can suggest. The Morning Chronicle, 10 February 1796

There was also her famous ‘shawl dance’. In 1838 William Gardiner reminisced that ‘The ballet of La Belle Laitière, by Steibelt, drew crowds to the theatre through a whole season. In this piece are the celebrated shawl dance, then so inimitably performed by Parisot, and the buffo dance, which has not been equalled for spirit and sportive humour.’ In 1805 The Monthly Mirror noted that ‘The Parisot dances a serpentine hornpipe in her usual style of sportive neatness.’ Sheet music for Parisot’s shawl dance and Parisot’s hornpipe were in print long after her departure from the stage.

A modestly attired Mademoiselle Parisot doing her famous shawl dance. From The New York Public Library

But who was Mademoiselle Parisot? Where did she come from?

No one really knows. Some sources say her first name may have been Rose or Céline and that her father may have been a sculptor in Paris or a journalist guillotined in the Revolution. 4

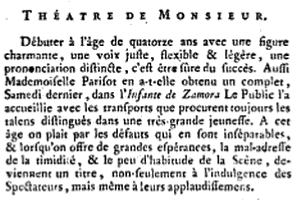

‘On 20 December, Mademoiselle Parisot, aged 14, made her debut in the role of Juliette in L’Infante de Zamora.’ From Les spectacles de Paris, ou calendrier historique & chronologique des théâtres, Vol 40 (1791).

Wherever she sprang from, she landed, aged 14, on 20 December 1789 at the Théàtre de Monsieur in Paris in a production of L’Infante de Zamora. At this stage the Revolution was only just over seven months old and Louis XVI was still nominally on the throne (although he had been demoted to ‘King of the French’) and martial law had been declared. Perhaps the horrors of the Terror, including the guillotining of her father, prompted her to decamp later to London.

In Paris, it was not her dancing skill that attracted attention so much as her youth and rather engaging gaucheness that the Gazette National 5 remarked on.

From Gazette Nationale, out Le Moniteur universal, Vol 1. Translation: Making a debut at the age of 14, with a charming figure; honest, flexible and light voice, and distinct enunciation is the way to ensure success. In this way, Mademoiselle Parisot was a great success on Saturday in L’Infante de Zamora. The public received her with transports of joy reserved only for those with distinguished talents at a young age. The faults that accompany that age are pleasing to all, and whilst we have high hopes for her, gauche shyness, and uncertainty on stage might become headline-worthy, not only for the indulgence of the spectator but also for their applause.

James Gillray, Modern grace, or the operatical finale to the ballet of Alonzo e Caro [sic] (1796) London:, Hannah Humphrey. NYPL catalog ID (B-number): b19758839. The three dancers are Fanny Elssler (or possibly Rose Didelot), Charles Louis Didelot and Mademoiselle Parisot.

Although Parisot was much in demand and made good money, the moralists had not given up the fight. In 1805 the Bishop of London ordered that theatres must drop their curtains before midnight on Saturday nights or they would lose their licence. To comply with this, at midnight on 15 June 1805 at the Opera House, Mr Kelly, the stage manager, brought down the curtain in the middle of a pas de deux danced by Mademoiselles Deshayes and Parisot. The audience were furious and ‘screamed, hooted, yelled, threw all the chairs out of the boxes into the pit, tore up the benches, broke the chandeliers, jumped into the orchestra, and smashed all the instruments of the unlucky musicians.’ 6By 1807 Parisot’s dancing career was over. Aged 32 she married ‘Mr J. Hughes’, an ’eminent florist-worker’ of Golden Square and never again appeared on the stage. In 1827, the Morning Chronicle reported that she was running a business at 324 Oxford Street in London selling French perfume and flowers and ten years later The Musical World 7 said she was living in Paris. The date of her death is unknown.

Notes:

The Annual Register, Or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year 1798. (1800) London: Dodsley’s. p. 230. The Bishop was speaking in the House of Lords. ↩Didelot also developed a ‘flying machine’ which lifted dancers up, allowing them to be supported as they left the ground. ↩George Coleraine, The Life, Adventures and Opinions of Col. George Hanger, written by himself (1801). New York: Johnson & Stryker for J. W. Fenno. Why the Devil would beat Mademoiselle Parisot for doing his work, Coleraine did not explain. ↩Two men known to have been executed during the Terror and to be either of an appropriate age or of indeterminate age may have been Mademoiselle Parisot’s father: François Parisot, on 3 May 1794; P. H. Pariseau, a 41-year-old journalist, on 10 July 1794 (Genéalogie60, comp. Les 13 045 Guillotines Pendant la Terreur. Compiègne, France: Genéalogie60, 2006-2009). ↩Gazette nationale, ou Le Moniteur universel, 1791, Vol 1. ↩London Society, an Illustrated Magazine of Light and Amusing Literature. Vol VIII (1862). The theatre manager (and part-owner) Francis Goold later tried to prosecute some of the ringleaders but had to settle for an apology and compensation for those who had been injured. ↩The Musical World, A Weekly Record of Musical Science, Literature and Intelligence, Vol VII (1837). p. 126 ↩The post Mademoiselle Parisot’s shocking pirouettes put London in a spin appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

September 6, 2018

BBC Radio 4 – In Our Time: Index of episodes on 18th-century subjects

The post BBC Radio 4 – In Our Time: Index of episodes on 18th-century subjects appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

August 7, 2018

Five Georgian kitchens

A recent tour of Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk took us into the Victorian kitchens. As we explored the coppers and the ranges and perused the ledger of servants which recorded their employment and reasons for leaving it occurred to me that when I visit these grand houses I always come away thinking that the kitchen and the library are my favourite rooms. The artefacts speak of years of hard labour through endless seasons: lifting, chopping, boiling, scrubbing. I long to see them in action, with all the heat, pain and inevitable hellish kitchen conflict as well as the fun and joshing with your colleagues, the sneaky tastes of interesting dishes and and the scoffing of delicious leftovers.

For artists, kitchens offer rich inspiration: interesting structures and objects – ranges, shelves, baskets, bottles, pans – and informal, real poses – people at work, engrossed in their task. These two images by John Atkinson, about whom I have found out nothing, were clearly intended as a pair.

John Atkinson, A girl bundling asparagus for market (1771). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

John Atkinson, Kitchen scene (1771). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

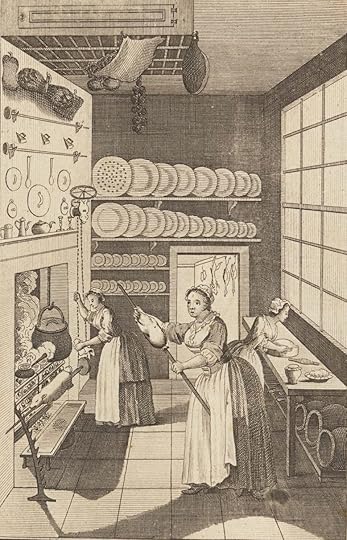

Of course, illustration has a different purpose, so this frontispiece to Martha Bradley’s The British Housewife: or the Cook, Housekeeper’s, and Gardiner’s Companion from about 1760 is more of a diagram of a typical kitchen. The head cook is preparing pork for roasting while one of her two assistants turns the spit and the other makes pies. The room is clean, well-ordered and well-lit by a large window. As many Georgian kitchens were in the basement of the house, this was probably not the reality for most households, which was probably more like the kitchen at Dennis Severs house.

Frontispiece from Mrs Martha Bradley, The British housewife: or the cook, housekeeper’s, and gardiner’s companion. Calculated for the service both of London and the country : and directing what is necessary to be done in the providing for, conducting, and managing a family throughout the year… Courtesy of Wellcome Images

The warmth and fun of family life based in the kitchen is captured beautifully in this rare and humourous domestic genre scene by Maria Spilsbury (1777–1820), one of the few woman artists of the early 19th century. Four children and a cat cause havoc in a large country kitchen. Employers (including what looks like a mother-in-law on the right) and servants happily occupy the same space, with pie-making at one end and what looks like sewing on the right. The household is of some standing, as a manservant is employed.

Maria Spilsbury, Confusion (The Nursery in the Kitchen); Williamson Art Gallery & Museum; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/confusi...

Finally, High Life Below Stairs was a common theme for printmakers and the title of a two-act farce by James Townley (published 1759). In this print by James Caldwell (1739-1819) servants party in a basement kitchen. One has her hair done, watched approvingly by the cook (note the child doing her doll’s hair), a couple enjoy a beer and a song (accompanied by the dog) and an old crone scrubs clothes in a tub. The scene is chaotic, with discarded household implements. The proper order of society has been upset: anarchy threatens.

James Caldwell, High Life Below Stairs (1772), after a painting by John Collet. Lewis Walpole Library

The post Five Georgian kitchens appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

July 30, 2018

Five portraits of women reading

When I was a child in the late 1960s, my mother told me that the man upstairs had forbidden his wife to read books. Since I spent nearly every waking moment with my nose in a book, I was both incredulous and mystified. How did this poor woman put up with such a thing? Did she defy her husband?

Alas, women’s reading is frequently of interest to men, and not necessarily in a good way. In individual households they might be forbidden to read specific books or pages of the newspapers. Female education was often dominated by domestic skills and a bit of foreign language – enough to ensure women could converse intelligently with their husbands but not to get above themselves in areas that should not concern them. But women have always managed to circumvent the restrictions imposed by men, and reading is no different.

It’s worth bearing in mind that of these five depictions of women reading three are known to be by men and two are probably by men.

We’ll start proceedings with this stipple engraving by an unknown artist, in which a rather earnest-looking young woman seated next to a writing table and engrossed in her book fails to notice that Cupid hovers nearby and is about to brush the back of her head with the feather of his arrow. Possibly she is reading the type of racy romance that was thought to overstimulate the emotions of females. The cherub looks knowingly out of the picture at us.

Unknown, The reader tickled by Cupid (c. 1800). Lewis Walpole Collection

The next, by George Morland (1763–1804), is an intimate portrait of his wife Anne (1765–1804) who is dressed informally and seated on a sofa in her bedroom or boudoir. She holds a small book but is not actively reading. Rather, her gaze is cast sideways, and although the hint of a smile plays on her lips she has a weary, long-suffering expression, possibly because at the time this was painted she and Morland had separated, their marriage foundering under the stress of his drinking and profligate spending. Morland died in a sponging house nine years later, followed within four days by Anne, who had suffered chronic ill health for years as the result of a disastrous birth.

George Morland (1795). A Woman Called Anne, the Artist’s Wife. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Third is this Thomas Gainsborough. The young woman, shown in a landscape full of classical structures, is not actively reading but looks out of the frame questioningly. Perhaps she is perusing a female conduct manual. The sitter is unidentified but is similar in appearance to the woman in Portrait of a Woman, Possibly of the Lloyd Family.

Thomas Gainsborough (1750). Portrait of a Woman. (Girl with a Book Seated in a Park). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

By way of contrast the fourth image is a print by the satirical cartoonist James Gillray in which three women sit at a table while a fourth reads out loud from the Gothic novel The Monk. The print is inscribed “This attempt to describe the effects of the sublime & wonderful is dedicated to M.G. Lewis Esqr. M.P”, Lewis (1775–1818) being Matthew Gregory Lewis, the author who wrote and published the work in about 1795 when he was barely 20. Six years later, the novel, which went through several editions, came in for some heavy criticism from Scots Magazine 1 The Monk, usually thought of as a “male gothic” novel, was heavily influenced by Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, which Jane Austen satirised in Northanger Abbey.

James Gillray, Tales of Wonder! (1802). Courtesy of Princeton University Digital Library

Finally, in this 1778 print entitled The Studious Beauty, we can be confident the fashionable young lady seated by a table is not reading a tome of sermons or a manual on how to improve her conduct. Everything about her pose and appearance – the legs clearly delineated beneath her skirt, her hand lying suggestively in her lap – points to her being immersed in a racy romance or a sexy gothic novel.

Unknown, The Studious Beauty (1778). Printed for and sold by Carington Bowles, St. Pauls Church Yard, London. Lewis Walpole Collection.

Further reading

Kathryn Sutherland, Female education, reading and Jane Austen, British Library.

Conduct book for women, British Library

Notes:

“It is surely to be regretted, that youth should be exposed to the baneful influence of such works…” Scots Magazine, Vol 64, p548. Lewis came to regret some aspects of the novel. ↩The post Five portraits of women reading appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

June 27, 2018

1815: The fate of US prisoners of war at Dartmoor Prison

The post 1815: The fate of US prisoners of war at Dartmoor Prison appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

June 19, 2018

Q&A on Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches

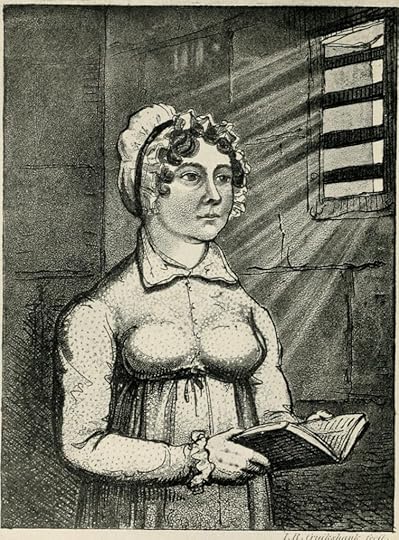

In 1815 cook-maid Eliza Fenning was accused of trying to murder her employer and his family. She went to the gallows in front of a crowd who largely believed she was innocent.

A Q&A session with Catherine Curzon (aka Madame Gilflurt) about my book Women and the Gallows has been published.

Here’s a taster…

What inspired you to choose executed women to write about?

It started when I became interested in Eliza Fenning, a kitchen maid who was executed in London in 1815 for attempting to poison her employer and his family – and who was most probably innocent. She was hanged at a time of great civil unrest and disruption, probably as a warning to the servant class not to challenge the social order. The circumstantial evidence against her was poor and the judge was warned there were serious doubts about her guilt, but he subjected her to a highly biased trial full of irregularities. Generally I’ve always been fascinated by the ‘down and dirty’ end of Georgian history and found that not much had been published recently specifically about the capital punishment of women.

The post Q&A on Women and the Gallows 1797-1837: Unfortunate Wretches appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

June 14, 2018

Titillation and contempt: the meaning of 18th-century caricatures of female fashion

Having previously posted on Monstrosities of 1799 by James Gillray, I thought I would return to the subject of fashion, but this time looking specifically at how caricaturists portrayed women. It seems to me that the artists explored three main themes: the comical impracticality of particular styles, the over-revealing nature of women’s clothes and the absurd and dishonest lengths women went to to disguise their natural appearance.

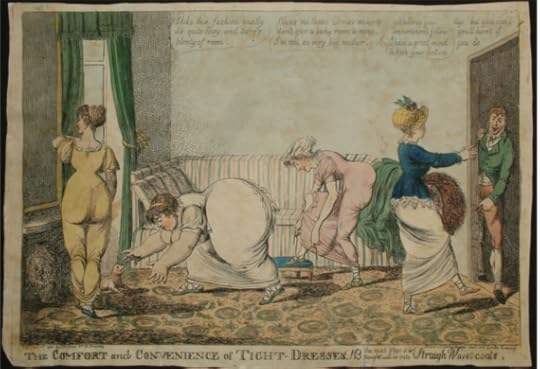

Charles Ansell Williams, The Comfort and Convenience of Tight Dresses (1805). The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

In ‘The Comfort and Convenience of Tight Dresses’ (1805) by Charles Williams (1797–1830), who sometimes worked under the name ‘Ansell’ or ‘Argus’ and was employed between 1799 and 1815 by the prominent print publisher S. W. Fores, a woman puts her knee through her flimsy dress as she ties her shoelaces; a fat woman bursts the seam of her dress while she bends to pet a dog. The meaning is obvious: the fashion for narrow skirts is an affectation and the women wearing them almost insanely stupid. Indeed, ‘The next step it is thought will be into straigh [sic] waistcoats,’ appears in the bottom right-hand corner.

Caricaturists routinely presented images of fashion-following women for general derision and male titillation and sometimes both (note in Williams’ cartoon the woman on the left with her large and peachy backside, the fat woman’s bust generously overspilling her dress), so the late 18th-century thin gauzy white gowns, often worn with few undergarments, were a gift. Thomas Rowlandson was very fond of nipples showing through tight dresses.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Elopement, 1792.

In ‘A Peep into Brest with a navel review!’ by Richard Newton (1777–1798), two women wear gowns split to the waist, their pert bosoms and rounded bellies on full display while a man holding an eyeglass views them with appreciatively. Although not overtly violent, the punning title uses military terms that carry with them an implicit reference to strategy, assault, conquest and victory. The women are prizes to be captured and plundered.

Richard Newton, A peep into Brest with a navel review! London : Pub. by R. Newton, No. 26, Walbrook, 1794 July 1. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The outfits in the cartoon is so extreme that we naturally wonder whether fashionable women really walked around with their breasts out. Apparently yes, they did, although it is unlikely that they did this anywhere other than private London soirées and parties given by the ton. Sir Gilbert Elliot’s account of Lady Anstruther’s ball in 1793 included a description of women wearing ‘an imitation of the drapery of statues and pictures, which fastens the dress immediately below the bosom, and leaves no waist… This dress is accompanied by a complete display of the bosom – which is uncovered, and supported and stuck out by the sash immediately below it.’ 1 Thomas Rowlandson showed women completely décolletées, but these were scenes either of intimacy as in ‘The Sailor’s Return’, in which the woman is possibly a prostitute, or drunken poverty, as in ‘Angry Scene in a Street’.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Sailor’s Return (undated); Angry Scene in a Street (between 1805 and 1810) Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Exposed bosoms apart, the late 18th century was generally a period when women could be more comfortable in their fashionable gowns. Thin white dresses had been worn in Europe since around 1780, a fashion driven in part by the new availability of chlorine bleach but also inspired by the aims of the French Republicanism – simple, pared down, ‘peasanty’ flowing designs reflected the values of the Revolution in a way that hot, costly, elaborate, multi-layered gowns did not.

Robert Dighton, A fashionable lady in dress & undress (1807). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Finally, we turn to the creation of an elegant fashionable woman from a shrunken husk. ‘A Fashionable Lady in Dress & Undress’ is a before-and-after showing a bald scrawny middle-aged woman at her toilette. Only with the help of cosmetics and creams, and a stylish wig and gown, not to mention a high-necked under-dress, is she changed into an acceptable version of herself: younger, smoother, prettier. The messages are clear: women’s value lies in their appearance, age certainly does not equal beauty, and women, being the deceivers they are, will do everything they can to trick the beholder into thinking them better-looking than they really are. As a side note, it is interesting to note that the caricaturist, Robert Dighton (1751–1814), had an additional career as a concert singer, so perhaps he was used to seeing female artists transform themselves before performing for an audience.

Nearly every example of caricature showing women and fashion displays a troubling misogynistic attitude. Whether women took exception to their portrayal as vain, shallow creatures too stupid to make rational choices even about the clothes they wore, or just sighed and got on with life while men chortled over their print collections, we don’t know.

Certainly caricaturists also targeted men for their fashion choices – there are plenty of effete ‘macaronis’ and dandies preening and prancing in fashionable garb – but arguably women’s bodies, their non-standard shapes and sizes, always seemingly encased in some ill-advised costume, were more often sneered at, and in more ways, than were men’s. There is little gentle ribbing. The comedy is usually sharp and vicious. And surely the pens of the caricaturists captured the male gaze in the way that later seaside postcard artists would: behind the façade of jeering, bold and unapologetic machismo was a malevolent mix of desire, contempt and sexual anxiety. At times, while perusing the archives, the centuries seem to melt away.

Notes:

Quoted in Vic Gatrell (2007), City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London. London: Atlantic Books. ↩The post Titillation and contempt: the meaning of 18th-century caricatures of female fashion appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

June 12, 2018

A new life in America: Guest post for All Things Georgian

My guest post on All Things Georgian looks at the fate of Abraham Thornton, the prime suspect in the murder of Mary Ashford, in the final months of 1818.

My guest post on All Things Georgian looks at the fate of Abraham Thornton, the prime suspect in the murder of Mary Ashford, in the final months of 1818.

The post A new life in America: Guest post for All Things Georgian appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

June 11, 2018

Mapping murder: Rowland Hill’s early career

The polymath Rowland Hill is best known for ‘inventing’ the penny post, but his many other talents included art, mathematics and pedagogy.

Rowland Hill’s 1837 Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability resulted in the creation of the revolutionary penny post, by which a letter weighing less than half an ounce could be sent anywhere in the United Kingdom. The sender was responsible for payment. Previously, the recipient would be liable, making the system not only highly inefficient socially inequitable. To receive a letter would cost a labourer about a day’s wage.

Hill, who was born into a liberal-thinking, nonconformist family, was driven by a desire to improve society. He felt that his post office reforms, which would increase the circulation of letters, would would encourage industry, restore divided families and promote literacy. They may have done all those things and certainly his achievements earned him widespread praise, an honorary degree from Oxford and a knighthood, as well as a lasting legacy: his system was replicated across the world.

But there are other less well-known aspects of this talented man, and in one particular project, in which he documented the movements of a young woman and her alleged murderer on the night of 26 May 1817, he combined several of them, notably his skills as a land-surveyor, cartographer and educator.

Rowland Hill’s father, Thomas Wright Hill, was a former brassfounder who set up Hill Top School in Birmingham. It was later renamed Hazelwood School. His sons Rowland and Matthew took over the running of the school in 1819. The school later moved to Tottenham in north London.

Rowland Hill’s mother, Sarah Lea,was from St James’s, Birmingham. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, she was a woman of ‘strong character’ who made up for her husband’s deficiency in common sense. It was her suggestion to set up Hill Top school.

One of eight children, Rowland Hill was both sickly and prodigiously precocious. At five he constructed a watermill; at 12 he was working as an instructor at Hill Top, the school his father established at Lionel Street, 1 Birmingham, primarily to educate his six sons. With other pupils at the school young Rowland set up a common-stock theatre company for which he wrote plays, painted scenery, built sets and put on hot-air balloon displays. In addition, tutored by Samuel Lines, the school’s drawing master, Rowland developed an interest in painting and sketching, and won a prize for one of his works.

There seemed to be nothing Rowland could not turn his hand to. He built a flat-bottomed boat, constructed a water clock and assisted at his father’s demonstrations of electricity at the Birmingham Philosophical Society. A project to draw up maps for a school atlas, started when he was 16, was one of the few that defeated him. Although he produced a map of Spain and Portugal he got no further. ‘It was, he wrote later, ‘a much greater undertaking than I at first imagined, owing to the great difference that exists in the works which it was necessary to consult.’ Despite failing to complete the project, the exercise must have been valuable experience for him and introduced him to some of the difficulties and questions involved in map-making.

No doubt, he would have preferred to have started from scratch and done the land-surveying, another of his hobbies, himself. In his journal, he recalled how he taught himself the principles: ‘I learned the art [of lands-surveying] as best I could; I might almost say I found it out, for I had then no book on the subject, and my father had no special knowledge of the matter.’

Once he had become sufficiently proficient, he sought to pass on his knowledge to his pupils. The ethos of Hill Top was to encourage practical knowledge, so together they mapped their playground and some of the local area.

A crude map showing significant places in the murder of Mary Ashford, created using printers glyphs, printed in the Chester Chronicle on 17 November 1817 but probably copied from one published earlier in the Lichfield Gazette. © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD

On the morning of 27 May 1817 the body of 20-year-old farm servant Mary Ashford was found in a stagnant pool near the village of Erdington outside Birmingham. The crime shocked the neighbourhood. A prime suspect, Abraham Thornton, a local bricklayer, was quickly identified and charged, and soon afterwards a local paper published a crude map of the area where the murder took place. Hill wrote in his journal:

My drawing-master [Samuel Lines] published a portrait of the poor girl – taken, I suppose, after death – with a view of the pond in which the body was found; and one of the Birmingham newspapers (the Midland Chronicle 2) gave a rude plan of the ground on which the chief incidents occurred. This, however, being apparently done without measurements, and not engraved either on wood or copper, but made up as best could be done with ordinary types, was of course but a very imperfect representation.

As Thornton’s defence at his trial in August rested on alibi evidence, maps were a crucial part of his trial and both prosecution and defence commissioned their own versions. But, despite widespread feeling that Thornton was guilty, he was acquitted.

Mary Ashford, by Samuel Lines, a drawing master at Rowland Hill’s father’s school. Hill thought that Lines had viewed Mary’s body in order to produce a likeness, but no evidence of this exists. Published by Craddock & Joy in Birmingham. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

In November, interest in the case was reignited with the news that a civil suit (‘appeal of murder’) by Mary’s brother would give another chance of justice. Rowland Hill, aged 23 and still working at the school, wanted not only to contribute to a better understanding of the case. He was convinced that he could produce something better than the newspaper effort, and was also sure that he could make money while doing so (the Hill family was not wealthy). He roped in his pupils and a man to whom he was teaching land-surveying to walk to Erdington to survey the area.

The copperplate scale map that resulted included detail of the area around the so-called ‘fatal field’ and a diagram of the position of Mary’s body in the pond, and was published in November 1817 in Birmingham and London (it was also printed in John Cooper’s report on the trial of Abraham Thornton and the subsequent court hearings in London).

Rowland Hill’s map sold for a penny a copy and was also printed in John Cooper’s account of the Warwick trial of Thornton and subsequent legal action in London (reproduced here). Soon after publication it was plagiarised. Hill’s brother Matthew suggested that he add a date at the foot of the map to establish copyright.

Hill made £15 from sales but unfortunately his work was so impressive it was soon plagiarised. He was incensed by this and wanted to sue but his brother Matthew thought this would be a waste of money and suggested instead that reprints include a date of publication.

Ten years after Rowland and his team created their map, the body of Mary Ann Lane was found in a pit 30 miles from Erdington. The case had horrible similarities to Mary Ashford’s. Perhaps it was those similarities that prompted newspapers to publish a map for the greater edification of their readers. The influence of Rowland Hill’s style is obvious.

After the murder of Mary Ann Lane, Bell’s London Life published a copperplate map of the Harbury area. 26 August 1827. © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD

My book The Murder of Mary Ashford is now available from Pen and Sword and all online outlets, and can be ordered from your local UK bookshop. The US edition will be available in September.

Sources

Hill, Sir Rowland and Hill, George Birkbeck (1880). The Life of Sir Rowland Hill and the History of Penny Postage. London: Thomas de la Rue & Co.

Bartrip, P. W. J., ‘A Thoroughly Good School’: An Examination of the Hazelwood Experiment in Progressive Education. British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Feb., 1980), pp.46-59.

Golden, Catherine J., ‘Rowland Hill (1795–1879). Victorian Review, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Spring 2011), pp. 9-13.

Smyth, Eleanor C. (1907). Sir Rowland Hill: The Story of a Great Reform. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

Notes:

On the edge of Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter. ↩I think he means the Lichfield Gazette. ↩The post Mapping murder: Rowland Hill’s early career appeared first on Naomi Clifford.