Naomi Clifford's Blog, page 3

September 9, 2019

Sanditon Episode 3

CONTAINS SPOILERS

How is young speaks-as-she-finds Charlotte getting on in her new job doing the filing for Mr Tom Parker, entrepreneur of Sanditon? What is Georgiana Lambe’s secret? Will Sidney give himself a talking to? Have Edward and Esther got it on any further? And flint-hearted sex-minx and schemer Clara, what should we make of her?

What follows is a plot précis of what happened in Episode 3 but, in Eric Morecambe’s immortal words, not necessarily in the right order.

In an effort to save Sanditon from his creditors, Tom Parker hires Doktor Fuchs (I am not joking you) who specialises in hydrotherapy and sports a very Under The Top Tchermann accent and an Over The Top propensity to kiss ladies’ hands.

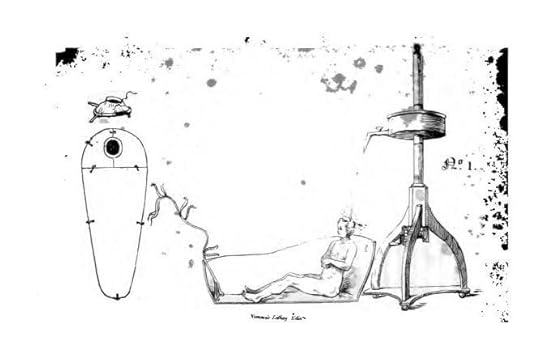

Clara offers to play guinea pig in Herr Doktor’s ground-breaking hot shower bath and deliberately scalds herself on the copper, thereby ruining Parker’s plans, and enticing Edward to step forward and carry her off from the nasty pipework wearing only her underfrillies (Clara that is, not Edward, and she was actually wearing a very plain undershift to denote how poor she is). Incidentally, some practitioners proposed hydrotherapy as a treatment for mental illness. No good for Clara, I think, as she is clearly a psychopath, for which there is no cure available.

Clara’s problems can probably not be fixed by a shower bath.

Clara’s problems can probably not be fixed by a shower bath.Sidders is being a Very Naughty Boy. Five bottles of wine with his mates and a shedload of fags, and ending up sleeping in the bar, growing grainy ‘moutarde de Dijon’ stubble, you get the picture. I think we are supposed to assume he is Troubled By Something. Personally, I am hoping it is his gayness, as I want Char to end up with Young Stringer – more of him anon.

In her efforts to see off Clara, Esther digs her considerable nails into the burn Clara has just gone to all that effort of acquiring. When Clara, who appears to be constructed out of asbestos, fails to emit even a tiny squeak of protest, Esther realises she has been bested and retreats in damp-eyed astonishment. We can only hope, for Esther’s sake, that the threat she made in Episode 1, to poison this monster, is part of her Plan B.

What else? Oh yes. Georgiana Lambe outrages public decency, including the creepy vicar, by painting a rude (or something) watercolour while on a school outing to the beach. I could only think of this:

The dangers of outdoor painting.

As we, sophisticated and worldly-wise as we are, are not even allowed to see what she did I can only assume it was Extremely Inappropriate.

Finally, the producers promised us an accident in this episode. I was just sitting there thinking that Clara’s altercation with the water heater did not really cut the mustard when what happens? An actual accident. Young Stringer’s Old Dad, Old Stringer (I assume), who, we are assured, is a master mason and only roughing it as a hod-carrier because Tom Parker is too tight to stump up for a proper workforce, falls off the scaffolding, or something, and gets covered in bricks. Result: a nasty open leg fracture and Char and Sidders doing first aid.

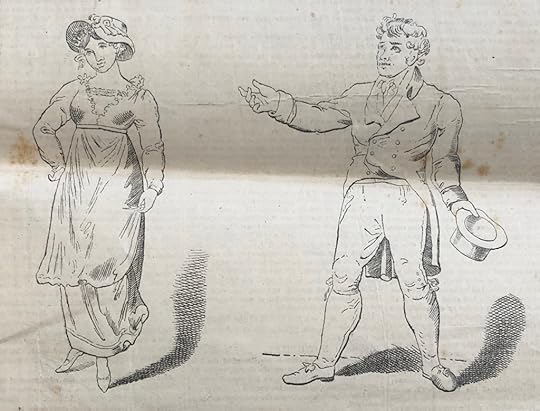

Sidney Parker (left) has had a shave and is ready for his turn as assistant surgeon.

Sidney Parker (left) has had a shave and is ready for his turn as assistant surgeon. The big strong men haul Old Stringer off to Parker’s beautiful shiny home and what do they do? Do they shoo out the cook and plonk him on the old oak kitchen table with its easy-to-clean surface? Do they heck. Or do they cart him off to the drawing room and let him bleed on the Chippendale? Of course! That’s how nice they are underneath it all. Then, Herr Doktor (who has not yet left town in ignominy after the shower bath incident) rushes in and proves he is not a quack but actually a skilled emergency surgeon and after roping in Sid and Char as nurses sets the broken leg in a trice. Char and new best friend Sid announce to Young Stringer that all is well with Old Stringer and ‘The leg is saved!’. If only someone would tell those doom and gloom merchants on 24 Hours in A&E how easy all this medicine really is. Of course, I might be a bit previous and will have to eat my words if Old Stringer later dies of scepticaemia, but I’m not expecting to.

What’s that at the back? Are we nearly there? Yes, actually we are. Char has what can only be described as a stroke of genius. And what is it? Only an idea to Save Sanditon, that’s all. What’s the idea? A regatta! With boats and things! Oh yah! I say, it’s briwwiant. So briwwiant that Tom Parker tries to pass it off as his own idea, and Sid, bless him, makes sure Char gets her due credit. (Yeah, right.) Anyway, she is given a new job of Events Coordinator and a salary of £20k in equivalent money (I made that bit up).

What does happen is that Tom Parker proves how nice he really is and promises to be a good employer to ‘the men’, pay full National Insurance and give them EU-style holidays. So Old Stringer’s leg has not been broken in vain.

I am hoping we’re off to the West Indies in the next episode, but fear we may only get as far as London. But as I am becoming a little claustrophobic in Sanditon, lovely as it is, even that will be a welcome change of air.

Oh, nearly forgot, Georgiana has promised Sid that she will be Good From Now On… but she’s been kissing a portrait of her secret boyf, so I am fairly sure she is telling porkies.

Scores

Historical context

Hydrotherapy contraption – I am guessing this is based on documented fact, so full marks.

A person belonging to the working classes being offered surgery in the drawing room. Doubtful.

Nudity quotient

After Sidney rising prettily from the sea last week, it’s a big fat zero this time.

Fidelity to the original

Can’t even see land.

I reviewed Episode 1 of Andrew Davies’ Sanditon (ITV) for the Historical Writers’ Association. I will try to keep you up-to-date with the remaining 7 episodes here.

Read my recap of Episode 2.

The post Sanditon Episode 3 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

Sanditon – Episode 3 recap

CONTAINS SPOILERS

How is young speaks-as-she-finds Charlotte getting on in her new job doing the filing for Mr Tom Parker, entrepreneur of Sanditon? What is Georgiana Lambe’s secret? Will Sidney give himself a talking to? Have Edward and Esther got it on any further? And flint-hearted sex-minx and schemer Clara, what should we make of her?

What follows is a plot précis of what happened in Episode 3 but, in Eric Morecambe’s immortal words, not necessarily in the right order.

In an effort to save Sanditon from his creditors, Tom Parker hires Doktor Fuchs (I am not joking you) who specialises in hydrotherapy and sports a very Under The Top Tchermann accent and an Over The Top propensity to kiss ladies’ hands.

Clara offers to play guinea pig in Herr Doktor’s ground-breaking hot shower bath and deliberately scalds herself on the copper, thereby ruining Parker’s plans, and enticing Edward to step forward and carry her off from the nasty pipework wearing only her underfrillies (Clara that is, not Edward, and she was actually wearing a very plain undershift to denote how poor she is). Incidentally, some practitioners proposed hydrotherapy as a treatment for mental illness. No good for Clara, I think, as she is clearly a psychopath, for which there is no cure available.

Clara’s problems can probably not be fixed by a shower bath.

Clara’s problems can probably not be fixed by a shower bath.Sidders is being a Very Naughty Boy. Five bottles of wine with his mates and a shedload of fags, and ending up sleeping in the bar, growing grainy ‘moutarde de Dijon’ stubble, you get the picture. I think we are supposed to assume he is Troubled By Something. Personally, I am hoping it is his gayness, as I want Char to end up with Young Stringer – more of him anon.

In her efforts to see off Clara, Esther digs her considerable nails into the burn Clara has just gone to all that effort of acquiring. When Clara, who appears to be constructed out of asbestos, fails to emit even a tiny squeak of protest, Esther realises she has been bested and retreats in damp-eyed astonishment. We can only hope, for Esther’s sake, that the threat she made in Episode 1, to poison this monster, is part of her Plan B.

What else? Oh yes. Georgiana Lambe outrages public decency, including the creepy vicar, by painting a rude (or something) watercolour while on a school outing to the beach. I could only think of this:

The dangers of outdoor painting.

As we, sophisticated and worldly-wise as we are, are not even allowed to see what she did I can only assume it was Extremely Inappropriate.

Finally, the producers promised us an accident in this episode. I was just sitting there thinking that Clara’s altercation with the water heater did not really cut the mustard when what happens? An actual accident. Young Stringer’s Old Dad, Old Stringer (I assume), who, we are assured, is a master mason and only roughing it as a hod-carrier because Tom Parker is too tight to stump up for a proper workforce, falls off the scaffolding, or something, and gets covered in bricks. Result: a nasty open leg fracture and Char and Sidders doing first aid.

Sidney Parker (left) has had a shave and is ready for his turn as assistant surgeon.

Sidney Parker (left) has had a shave and is ready for his turn as assistant surgeon. The big strong men haul Old Stringer off to Parker’s beautiful shiny home and what do they do? Do they shoo out the cook and plonk him on the old oak kitchen table with its easy-to-clean surface? Do they heck. Or do they cart him off to the drawing room and let him bleed on the Chippendale? Of course! That’s how nice they are underneath it all. Then, Herr Doktor (who has not yet left town in ignominy after the shower bath incident) rushes in and proves he is not a quack but actually a skilled emergency surgeon and after roping in Sid and Char as nurses sets the broken leg in a trice. Char and new best friend Sid announce to Young Stringer that all is well with Old Stringer and ‘The leg is saved!’. If only someone would tell those doom and gloom merchants on 24 Hours in A&E how easy all this medicine really is. Of course, I might be a bit previous and will have to eat my words if Old Stringer later dies of scepticaemia, but I’m not expecting to.

What’s that at the back? Are we nearly there? Yes, actually we are. Char has what can only be described as a stroke of genius. And what is it? Only an idea to Save Sanditon, that’s all. What’s the idea? A regatta! With boats and things! Oh yah! I say, it’s briwwiant. So briwwiant that Tom Parker tries to pass it off as his own idea, and Sid, bless him, makes sure Char gets her due credit. (Yeah, right.) Anyway, she is given a new job of Events Coordinator and a salary of £20k in equivalent money (I made that bit up).

What does happen is that Tom Parker proves how nice he really is and promises to be a good employer to ‘the men’, pay full National Insurance and give them EU-style holidays. So Old Stringer’s leg has not been broken in vain.

I am hoping we’re off to the West Indies in the next episode, but fear we may only get as far as London. But as I am becoming a little claustrophobic in Sanditon, lovely as it is, even that will be a welcome change of air.

Oh, nearly forgot, Georgiana has promised Sid that she will be Good From Now On… but she’s been kissing a portrait of her secret boyf, so I am fairly sure she is telling porkies.

Scores

Historical context

Hydrotherapy contraption – I am guessing this is based on documented fact, so full marks.

A person belonging to the working classes being offered surgery in the drawing room. Doubtful.

Nudity quotient

After Sidney rising prettily from the sea last week, it’s a big fat zero this time.

Fidelity to the original

Can’t even see land.

I reviewed Episode 1 of Andrew Davies’ Sanditon (ITV) for the Historical Writers’ Association. I will try to keep you up-to-date with the remaining 7 episodes here.

Read my recap of Episode 2.

The post Sanditon – Episode 3 recap appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

September 2, 2019

Sanditon Episode 2

The post Sanditon Episode 2 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

Sanditon Episode 2 recap

The post Sanditon Episode 2 recap appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

August 30, 2019

TV review: Sanditon Episode 1

Read my review of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon, for the Historical Writers’ Association.

Read my review of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon, for the Historical Writers’ Association.

The post TV review: Sanditon Episode 1 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

TV review: Sanditon

Read my review of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon, for the Historical Writers’ Association.

Read my review of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon, for the Historical Writers’ Association.

The post TV review: Sanditon appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

August 23, 2019

Women and the Needle: Part 3 – Artists

In my previous two posts, I looked at women who sewed and embroidered for a living or because it was part of their domestic duties or as a genteel pastime. Here I explore female artists who used stitchery to create art. Needlework used in this way brings up the whole art versus craft debate. Generally, men were inclined to see art made by men as art and art made by women, especially if they used unconventional media, as craft. But what choice did they have? Women were largely excluded from the male art world, with their lack of presence blamed on their innate lack of genius.

The alternative media – wax, shells, pottery, china painting and shell work – used by women showed their superb creativity. Often these artists were also imaginative businesswomen who undertook the promotion of their work and made a good living for themselves.

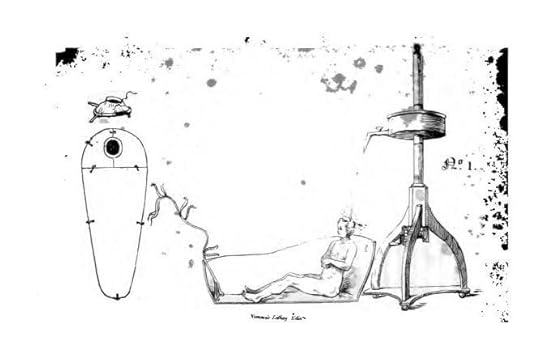

MARY DELANY (1700–1788)

Portrait of Mary Delany as an old woman, after J. Opie (1861). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Mary Delany “wrote and illustrated a novel, designed furniture, painted, spun wool, made shellwork, featherwork, silhouettes, invented the entirely new art of paper collage, and was an embroiderer of great artistry, designing her own compositions and relishing painterly effects in embroidery silks.”1 Numerous examples of her work are in the British Museum. She was also a superb plantswoman and botanist.

Although best known for her botanical découpage, which she called ‘paper-mosaics’, she also produced intricate silk-embroidered flower designs such as the satin panel from a mantua (below). The garden historian Mark Laird has said that her embroidery showed “the most accurate horticultural detailing of any work I’ve seen from this period.” It is likely that paid professional embroiderers carried out the highly specialist work (the flowers have a 3D quality not easy for an amateur to achieve), working to her designs.

Delany, née Granville, was born in 1700 at Coulsdon in Wiltshire into a well-connected but not wealthy aristocratic family. At 17 she was married off to 60-year-old Alexander Pendarves, who died seven years later, after which she was free to pursue her interests, despite not inheriting his estate. She was friends with many of the intellectual elite, including Georg Frederick Handel and Hester Thrale, and was acquainted with Robert Hooke, Joseph Banks, Jonathan Swift and Daniel Solander. In 1743 she married a widowed Irish clergyman Dr Patrick Delany with whom she shared an interest in botany and gardening. After being widowed a second time, George III and Queen Charlotte gave her a small house at Windsor and a £300 annual pension. Delany taught the royal children botany and sewing.

Detail from the front panel of the petticoat c.1740. The Gardens Trust has a good post on Mrs Delany’s Petticoat. The dress was of satin with silk embroidery.

Mrs Delany also used a black background for her papercuts, onto which she stuck – using eggwhite or flour and water – tiny pieces of paper building up each part and sometimes using as many as 200 paper petals per flower. To create shading and depth she layered smaller pieces over larger ones, and sometimes added watercolours.

Mary Delany is remembered at St James’s Church, Piccadilly.2

A memorial to Mary Delaney in St James’s Church, Piccadilly. By Tedster007 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

MARY LINWOOD (1755–1845)

On Miss Linwood’s Exhibition.

A FRIEND who witness’d Linwood’s art,

Said, ‘Painting is quite ousted.’

I cried out, ‘no,’ with all my heart,

But own’d it might be worsted.3

John Hoppner, Mary Linwood (c. 1800). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Mary Linwood produced about a hundred works of what was called ‘worsted embroidery’, rendering in unique and intricate sloping stitches versions of old master paintings, a technique known as needle-painting. She was highly celebrated in her long life (she died at the age of 90), met numerous heads of state and her art was exhibited across the Western world. Her works were on display at the Linwood Gallery in Savile House, Leicester Square from 1800 to 1844.

Mary Linwood’s Exhibition in Leicester Square. From Chambers Book of Days, Vol 1.

Mary Linwood was born in Birmingham in 1755, the daughter of a wine merchant; when she was nine her father became bankrupt and the family moved to Leicester, where her mother opened a private school for girls. At the age of 13 she began making embroidered pictures and by 20 was established as a needlework artist (she also had a long parallel career as the head of the girls’ boarding school she inherited from her mother).

In 1786 Linwood was awarded a silver medal by the Society of Artists “for submitting to the inspection of the Society, as examples of works of art, and of useful and elegant employment, three pieces of needlework, representing a hare, still life, and a head of King Lear.”4 After this she came to the attention of Queen Charlotte. The upper-class set, who viewed her works in a private exhibition at the Pantheon in Oxford Street, were highly enthusiastic. She also attracted the attention of the Empress Catherine of Russia and, later, Napoleon gave her a Freedom of Paris award.

Mary Linwood’s 1825 portrait of Napoleon was displayed in the Leicester Square Gallery as number 52, in the ‘Gothic Room’. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

In 1798 she opened an exhibition at the Hanover Square Concert Rooms, which toured Scotland and Ireland; two years later it moved permanently to Leicester Square. Here her works were displayed to best advantage, in large rooms hung with scarlet cloth trimmed with gold. Some were shown in dramatic settings: ‘Lady Jane Grey Visited by the Abbot and Keeper of the Tower at Night’ was viewed down a long passage, as if going to a prison cell, and Thomas Gainsborough’s ‘Cottage Children With an Ass’ was hung as if in a cottage, with visitors peeping through the window.5

Linwood steadily added to the collection. She did all the work herself, from the initial sketches to the embroidery and she personally supervised the dyeing of the fine crewel wool she used. Eventually 64 ‘paintings’ were shown, as well as a self-portrait she did when she was 19. Until she lost her sight in her mid-seventies, she produced over 300 works.

Hanging Partridge, after Moses Haughton. By Mary Linwood (1755-1845) – Bonhams.

In 1838, ill and financially ruined, she offered a hundred works to the British Museum, which rejected them. They raised only £300 at auction. The exhibition closed in 1844, at a time when Linwood’s oeuvre seems to have fallen sharply out of favour. An offer of 3,000 guineas (£3,150) had at one time been refused for ‘Salvatore Mundi’ after Carlo Dolci (Linwood bequeathed it to Queen Victoria) but after her death the remaining collection raised less than £1,000. She died, much loved for her generosity to the poor, the following year.

The post Women and the Needle: Part 3 – Artists appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

Women and the Needle – Part 2: Working women

Typing was not offered at my secondary school so twice a week, in the dark and rain, I caught a bus to North Kensington to bash out pretend invoices on a huge manual machine. Typing turned out to be my most directly useful qualification and meant I could always earn a living. For girls in the Long 18th Century sewing had the same function. It was a transportable skill that would always guarantee you work of some kind and keep the wolf from the door. Like many working-class girls, female orphans and children abandoned to the Foundling Hospital were taught plain sewing, spinning and knitting, in order to ensure they had an income.

In the first post of this series, I looked at genteel and aristocratic women who sewed. Here I cover needlework for payment. Women earning their living from sewing were mostly, but not exclusively, working-class.

But how did most women experience life as a seamstress? Women sewed both within and without the home, of course. Sometimes they were independent providers – dressmakers, mantua makers and milliners benefitting from the intense interest in fashion amongst the rich by helping women achieve the fashion looks they aspired to. It was not always plain sailing and they had to learn to be diplomatic. As the author of The English Book of Trades archly put it, “the Ladies’ Dress-maker’s customers are not always easily pleased; they frequently expect more from their dress than it is capable of giving.” It also helped your brand if you acquired a French name.

And, behind the scenes, the work was arduous:

The business of a Ladies Dress-Maker and Milliner, when conducted upon a large scale and in a fashionable situation, is very profitable; but the mere work-women do not get any thing at all adequate to their labour. They are frequently obliged to sit up very late, and the recompense for extra work is, in general, a poor remuneration for the time spent. From The Book of English Trades (1818).

The Ladies Dress Maker, from The Book of English Trades and Library of the Useful Arts (1818).

The illustration shows an elegant salon but James Gillray’s cramped milliner’s/dressmaker’s workshop was probably more typical. In his ribald political cartoon from 1800, the exiled stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange, tries to recover his ‘indispensibles’ by thrusting his hand up the flimsy skirts of two seamstresses. It’s a reference to the Dutch colonies he gave away to the British but it also makes the point that such women are seen as sexually available. Notice that they look surprised but don’t resist.

James Gillray, The man of feeling, in search of indispensibles; a scene at the Little French Milleners A number of disputes having arisen in the Beau Monde, respecting the exact situation of the ladies’ indispensibles (or new invented pockets) whether they were placed at the ancle [i.e. ankle], or in a more eligible situation, the above search took place, in order to determine precisely the longitude of these inestimable conveniences (1800), published by Hannah Humphrey, During his exile in Britain after the Batavian Revolution, William V, Prince of Orange instructed the governors of the Dutch colonies to hand them over to the British for ‘safe-keeping’ and in 1799 he ‘sold’ a fleet of captured ships to the Royal Navy. Library of Congress LC-DIG-ds-07296.

Millinery and mantua-making were often seen as covers for prostitution. Rictor Norton has a good essay on this. Charles Dickens’s fictional creation Kate Nickleby was aware of this reputation when she was apprenticed by her evil uncle to the establishment of Madame Mantalini and her predatory husband.

William Holl Jr, after William Powell Frith, Kate Nickleby (1848). Although set after the Georgian period, the situation of dressmakers and milliners in Dickens’ novel Nicholas Nickleby had not substantially changed. They were subject to sexual predation and economic exploitation. NPG D38965 © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Heilmann’s idealised portrait, a well-dressed seamstress in a domestic setting and wearing a mob cap casts her eyes down demurely, seemingly intent on her work, but she is showing s just enough bosom to be interesting and the cloth she is working on falls between her parted knees. Subservient, poorly paid, sedentary, passive, the seamstress offers the perfect male fantasy.

Print after Johann Kaspar Heilmann, Domestic Amusement: The fair seamstress (1764) Lewis Walpole Library .

Possibly the most exploited group of needleworkers was the parish apprentices, in many cases indentured into virtual slavery for unscrupulous employers. In my book Women and the Gallows 1797-1837 I tell the story of 61-year-old Esther Hibner, who was hanged in 1829 for murdering 10-year-old tambour-maker Frances Colpitts. Frances was forced to stand for hours in Hibner’s King’s Cross workshop embellishing and embroidering Brussels or Nottingham net. The notorious case exposed the dreadful conditions young tambour-makers suffered in order to supply highly fashionable fabrics to a competitive market, but did not lead directly to improvements in their treatment.

Tambour embroidery frame, from Embroidery and Lace by Ernest Lefébure and Alan S. Cole. London: H. Grevel (1888).

Needlework as a money-making occupation was not confined to the working-class. Mary Wollstonecraft thought the repetitive and pointless nature of domestic needlework performed by middle-class women affected their thinking power, turning them into frivolous drones. Mary Lamb, writing in 1815,1 agreed, asserting that “Needlework and intellectual improvement are naturally in a state of warfare,” and proposing that needlework is never done except in return for money.

Mary, who was mentally unstable throughout her life, had a particular reason to be suspicious of needlework, even when it was done for profit. In 1796, aged 31, she was working at home as a seamstress making ladies riding coats when she killed her mother with a carving knife after an altercation with their apprentice. Although the family was middle-class, they were relatively poor and Mary worked to supplement their income. In the reported opinion of the Magistrate who sent her to an private asylum rather than charge her with murder:

It seems the young Lady had been once before, in her earlier years, deranged, from the harassing fatigues of too much business. —As her carriage towards her mother was ever affectionate in the extreme, it is believed that in the increased attentiveness, which her parents’ infirmities called for by day and night, is to be attributed the present insanity of this ill-fated young woman. Morning Chronicle, 26 September 1796

“Too much business” implies that the pressure of work in circumstances tipped Mary, who was held in high affection by her family, even after the killing of her mother, over the edge. When Mary recovered she was released and was free to pursue, with her brother Charles, her literary interests. When her mental condition deteriorated she was returned to the asylum.

Mary Lamb (1764-1847)

As we think of those women toiling in poor light to meet gruelling deadlines, for poor pay and little appreciation, perhaps we should also consider the people who make our clothes now, wherever in the world they are, and try to ensure that we are not replicating the terrible lives of Georgian needlewomen.

In the final part of this series I look at the work of women who used needlework to produce art.

The post Women and the Needle – Part 2: Working women appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

August 20, 2019

Women and the Needle – Part 1: Ladies’ work

As we all know, there’s work and then there’s ‘work’. Working-class women in the Long 18th Century worked, that is they laboured, to earn money, and sometimes that included needlework – sewing clothes, household items and industrial items, or making lace and embroidery, such as tambour. ‘Work’ was the occupation of many genteel women and girls. This could be mending or it could be fancy decorative work: embroidering a tablecloth or a screen, for instance. There was also something else: sewing as art. Women, largely excluded from the male-dominated art world, found many ways to create and to earn their keep doing so, but often they had to use their ingenuity to do so. Wax, shells, needlework, often derided as mere craft, are part of that tradition.

The type of needlework women did was determined by her social rank and her circumstances. Here I look at sewing for pleasure by aristocrats and genteel women. Part 2 looks at sewing as a job and Part 3 covers how women used needlework to create art.

Unknown artist, Lady Jane Mathew and Her Daughters, c. 1790. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Lady Jane Mathew (née Bertie) – shown on the left in the painting – was the wife of General Edward Mathew, Governor of Grenada. The sewing shown is a pastime rather than a duty, and the portrait is an advertisement for the qualities of these unmarried women, as they display gentility of nature, competence in domestic matters and patient application. Note the serious environment (no smiling is going on) and the classical relief on the wall. One of the women shown in the portrait may be Anne Mathew, who married Jane Austen’s brother James in 1792, and who was described through Austen’s comment on Anne’s nieces: “Both prettyish; very like Anne; with brown skins, large dark eyes and a good deal of nose.”1

Paul Sandby, Woman Seated by a Window (c. 1760-80). Royal Collection Trust.

Upper-class women tended to do crewel embroidery, using heavy wool threads on durable fabrics to create decorative floral designs to enhance clothing, bedding, draperies. There was also flat silk stichery, using silk threads on silk fabric, often made on a tambour (two hoops over which the fabric is stretched – more on tambour work done by parish apprentices in Part 2).

François-Hubert Drouais, Portrait of Madame de Pompadour at her Tambour Frame, c. 1763. Courtesy of The National Gallery, London.

By the middle of the 18th century, upper-class women were using a variety of techniques to embellish clothes and household items. Knotting (or tatting), a way of creating a durable lace using knots and loops, on long strips of fabric, was a relatively easy technique. It did not need good light and could even be done on the move, in a carriage, for instance. In this portrait of Queen Charlotte and her daughter by Benjamin West, Charlotte the Princess Royal holds up some finished knotting sewn on to a coverlet. Again, the artist has been at pains to emphasise the serious, scholarly credentials of the subjects by showing books, classical busts, sheet music and papers.

Engraving after Benjamin West, Queen Charlotte with Charlotte, Princess Royal, 1778. Courtesy of Naomi Clifford.

July 10, 2019

Abraham Thornton’s gauntlet sold for £6,875

One of the leather gauntlets used in the last-ever legal challenge to trial by battle in an English court has been sold at Christie’s in London for £6,875 two hundred years after its pair was dramatically thrown down in Westminster Hall.

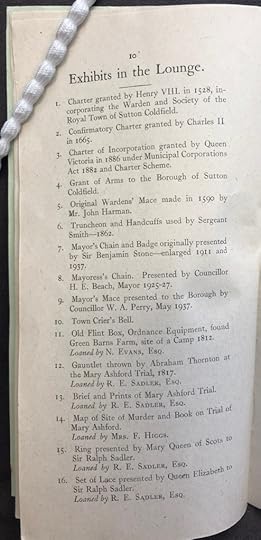

One gauntlet was thrown down in Westminster Hall. The other, shown here, was kept in the family of Thornton’s solicitor Edward Sadler until it was sold at Christie’s on 10 July 2019.

The last time the gauntlet was seen in public was in 1942, when it was displayed at Sutton Coldfield town hall, as part of an exhibition of local artefacts.

The documents sold with the gauntlet in the lot include the original of Edward Sadler’s brief to Thornton’s barristers for the Warwick trial for murder and rape.

The gauntlet was preserved by Thornton’s solicitor, Edward Sadler, whose offices were in the High Street, Sutton Coldfield, and remained in his family, passing down through the generations to his great-great-great-great grandson Magnus Bowles, a specialist bookseller, who put it, and associated documents, up for sale at Christie’s.

As a family we are very hopeful that the gauntlet will find a new home in an institution where it can be on display for all. It is testament to a remarkable human story – the tragic murder of Mary Ashford – and a dramatic and historic legal one.

Magnus Bowles, a descendant of Edward Sadler

In a case that made legal history, Abraham Thornton, a bricklayer from Castle Bromwich, who was accused of murdering Mary Ashford in the village of Erdington near Birmingham, threw down one of two gauntlets in the middle of a packed Court of King’s Bench in Westminster Hall, London on 17 November 1817, crying, “Not guilty and I am ready to defend the same with my body.” Thornton demanded a ‘Wager of Battel’ with his prosecutor. The whereabouts of this gauntlet—rumoured to have been given to the British Museum—is currently unknown. The second gauntlet had been kept in family of Thornton’s solicitor Edward Sadler for 200 years.

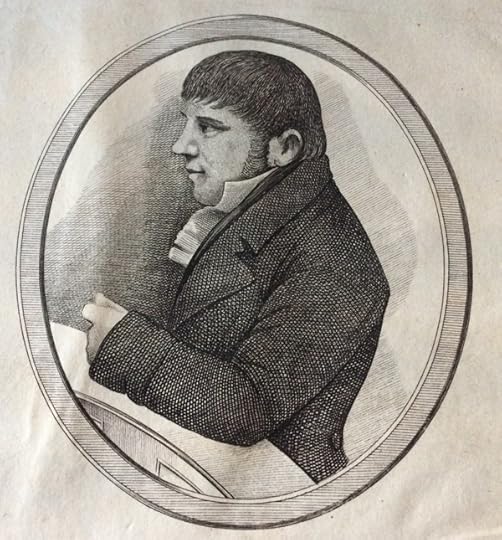

Strong evidence against Abraham Thornton was presented in court at Warwick but all of it was circumstantial. After the verdict a prison snitch came forward with additional information that lay in the archives for 200 years. Image from the Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 24 January 1885.

Three months before the challenge, Thornton was acquitted at Warwick Assizes, but Mary’s brother William Ashford dragged him back to court in London for a private prosecution using an archaic law known as Appeal of Murder. Abraham Thornton’s lawyers decided to use an equally outmoded law asserting his right to decide the case in a one-to-one duel in which the protagonists would fight each other equipped only with cudgels and shields.

Not guilty and I am ready to defend the same with my body.

Abraham Thornton’s response in Westminster Hall, when asked if he was guilty of the murder of Mary Ashford, as he threw down the gauntlet.

The legal fraternity was horrified that such a barbaric event could take place in the modern age but after a protracted series of legal arguments, the judges sitting on the case conceded that a trial by battle was legal and could proceed. The case collapsed when William was forced to withdraw—Thornton was a beefy bricklayer and William, who was small and slight, stood no chance. Appeal of Murder and Trial by Battle were removed from the statute the following year. After his return to Castle Bromwich Abraham Thornton was ostracised by his neighbours and emigrated to America.

Abraham Thornton, from a sketch taken in court. From J. Cooper’s A Report on the Proceedings Against Abraham Thornton at Warwick Summer Assizes, 1817…

Mary Ashford was buried in the churchyard at Holy Trinity in Sutton Coldfield. The inscription on her gravestone, paid for by public donations, calls her murderer ‘a wretch’ whom ‘avenging wrath’ will pursue. Every year a local resident lays flowers on her grave. The case attracted huge attention across the country and inspired several popular plays. Crowds flocked to Westminster Hall to catch a glimpse of Thornton as he arrived for the hearings. It was said to have inspired Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe.

Mary Ashford’s gravestone at Holy Trinity Church, Sutton Coldfield. Very little of the inscription is legible.

Unknown to the public, a convicted felon called Omar Hall who had shared a cell with Thornton came forward with additional evidence against him but William Ashford’s lawyers decided not to pursue this course: to do so meant they would have had to obtain a royal pardon for Hall, and they also felt that his testimony, as a prison snitch, would have been distrusted. There are more details about this evidence in my book The Murder of Mary Ashford.

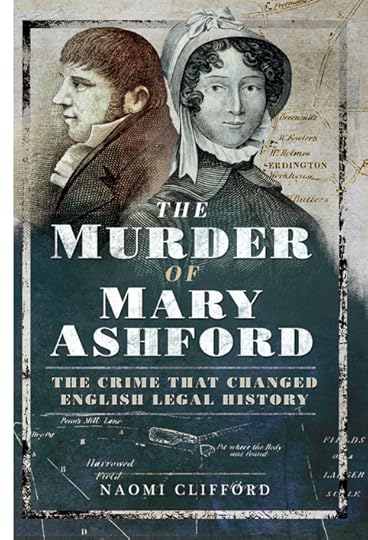

The Murder of Mary Ashford: The Crime That Changed English Legal History, published by Pen and Sword.

The gauntlet, of white kidskin, is in excellent condition. It is decorated with green silk embroidery, a ribbon of red leather and a green silk fringe. The missing pair is said to have ended up in the British Museum but has not so far been traced.

The gauntlets were not “a pair”—that is, right and left—but were both alike; one pouch, without separate fingers or thumbs, as ordinary gloves have. The size of the glove is ten inches long, and nine in circumference round the middle of the palm; so that, although large enough to contain a man’s hand, the width is too narrow to admit of the hand being so placed as to grasp anything, as the thumb must underlie the fingers in the middle of the palm. From the wrist it expands considerably, as ordinary gauntlets do in a slight degree. Round the wrist is a sprayed ornament of dark and lighter green silk, embroidered with the crewel stitch now called “crewel work”; below that and nearer to the edge is a narrow band of red leather, three-eighths of an inch wide, with a small ornamentation of green silk cross stitches at the inner edge, and a narrow green silk fringe at the extreme edge next the arm. From the wrist depend three leathern tags, having four holes in each, through which, doubtless, were to be threaded the ten white leather thongs, each sixteen inches long, to fasten the gauntlet round the wrist. The gauntlet is made of white tanned sheep-skin, without a seam of any kind in it. It has long been a source of perplexity as to what it could have been made of; but from an examination of it the other day by two eminent Birmingham surgeons, it was decided that it was formed of a ram’s scrotum, as on it are to be seen the marks of the two rudimentary teats situated near to such a formation.

John Rabone, Notes & Queries, Series 6, xi (1885), p.462-3.

The last time the gauntlet was seen in public was in September 1942, when a great-grandson of Edward Sadler, Richard E. Sadler, lent it to the Sutton Coldfield Photographic Society for an exhibition along with other items.

The last time the gauntlet was seen in public was in September 1942, when a great-grandson of Edward Sadler, Richard E. Sadler, lent it to the Sutton Coldfield Photographic Society for an exhibition along with other items. The catalogue states that the gauntlet shown was the one thrown down in Westminster Hall (item 12), which is unlikely to have been the case.

The murder of Mary Ashford: related posts.

The post Abraham Thornton’s gauntlet sold for £6,875 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.