Naomi Clifford's Blog, page 9

August 30, 2017

Lady Georgiana Lennox and her adventures with the 1st Duke of Wellington

Lady Georgiana Lennox. Image © Alice Achacheby Alice Marie Crossland

Lady Georgiana Lennox. Image © Alice Achacheby Alice Marie CrosslandLady Georgiana Lennox, or Georgy as she was known to her friends and family, was born in 1795, the third daughter of the 4th Duke and Duchess of Richmond. She was one of 14 children who made up the large and unruly Lennox family. The Lennoxes were plagued by money troubles but nonetheless enjoyed the aristocratic lifestyle of the day.

It was in 1806 in Dublin that Georgy was first introduced to Sir Arthur Wellesley (he was made Duke of Wellington in 1814), when he took up the position of Chief Secretary of Ireland under Georgy’s father, who was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. He had recently returned from fighting the French in southern India and had married his long-term love interest Kitty Pakenham, although the marriage was not turning out to be successful.

Georgy and her sisters were enthralled by the young and handsome army hero. The ‘Great Sir Arthur’, as they called him, spent only six months in Dublin – he was called to greater fame and fortune in the Iberian Peninsula – but while he was in Dublin he enjoyed getting to know the Lennox family. Every morning he would ride across Phoenix Park with Georgy on his way to his office. Despite their 26-year age gap, they developed a friendship that lasted until the Duke’s death in 1852.

In 1814, in an attempt to save money, the Lennox family moved to Brussels. With Napoleon languishing in exile on the island of Elba, Europe was no longer a theatre of war. Living was cheap and a strong expat community flourished. Little did anyone know that the following year Belgium would play host to the most important battles of the 19th century, the Battle of Waterloo.

The Duke of Wellington gave this miniature by Simon-Jacques Rochard to Georgy at a dinner held before the Battle of Waterloo. Image © Alice Achache

The Duke of Wellington gave this miniature by Simon-Jacques Rochard to Georgy at a dinner held before the Battle of Waterloo. Image © Alice AchacheIt was Georgy’s mother, the Duchess of Richmond, who threw the now legendary ball on 15 June 1815 while Brussels was in a state of high tension as Napoleon’s army was a mere 30 to 40 miles away. It was a glittering affair with around 200 people in their finest clothes or military uniforms. At dinner Georgy had the honour of sitting next to the Duke of Wellington, an indication of how close the two had become. He gave her a miniature portrait of himself, an object she treasured forever.

In the early hours of 16 June, shortly after dinner ended, Lt Harry Webster, mud-splattered after riding for hours, entered the ballroom bearing a note. The Duke soon afterwards began to give orders for the coming battle.

News spread quickly throughout the revellers. Georgy dashed up to the Duke to ask him about the rumours of an imminent battle. She later recounted in her memoirs:

‘He said very gravely “Yes, they are true; we are off tomorrow.” This terrible news was circulated directly, and while some of the officers hurried away, others remained at the ball, and actually had not time to change their clothes, and fought in evening costume.’

Soon after this, Wellington and Georgy’s father slipped away to the library to examine one of Richmond’s maps. Wellington marked a spot near the village of Waterloo and stated, ‘I must fight him here.’

Over the next three days Wellington led the Allied forces, aided by Blücher’s Prussian forces. During the battle Georgy and her sisters helped with the casualties coming in from the front. They made cherry water for convalescents and scraped lint (it was used to dress wounds). Those left behind waited anxiously to hear news. On the third day victory was declared, but it had been dearly bought. Both sides had seen a shocking loss of life with at least 23,000 Allied dead and 25,000 French killed or wounded. The Duke had lost many fine officers who had served him loyally throughout the Peninsular Wars. Georgy was lucky that her brothers and father were safe and that most of her close friends had survived.

After Waterloo Georgy and Wellington’s friendship continued. There has always been some conjecture as to the nature of their relationship, although no archival evidence has been discovered to indicate that it was anything more than a strong flirtation.

Somewhat unusually for the time, Georgy did not marry until she was 29. When she did, she married for love, falling for the kind and charming William Fitzgerald de Ros, who later inherited the title of Baron de Ros from his brother. Georgy and William went on to have three children and the de Ros and Wellington families continued on close terms until old age.

Until now, historians have not given Georgy’s connection to the Duke much as examination as his more famous female companions such as Harriet Arbuthnot or Angela Burdett-Coutts. I sought to rectify this five years ago when I was offered the chance to study the Duke’s unpublished letters to Georgy. They revealed thrilling new aspects to the Duke’s character and to his friendship with women in general and tell of a Duke far more familiar, relaxed and even flirtatious than he is now remembered. They also reveal Georgy’s personal journey, the story of an aristocratic Regency woman who lived a happy and adventurous life to the full.

Wellington’s Dearest Georgy is available online and in bookshops. The Kindle e-book is currently on sale for the next few weeks and is only £3.98!

Wellington’s Dearest Georgy is available online and in bookshops. The Kindle e-book is currently on sale for the next few weeks and is only £3.98!

Further information

Find out more about the life of Lady Georgiana Lennox at www.georgiana-deros.co.uk.

Alice Marie Crossland specialised in 19th Century British Art at University College London. She worked with the Wellington family on the catalogue of portraits Wellington Portrayed, which was published in 2014. She has since worked at the National Gallery London and Royal Academy of Arts and in 2016 published her first biography Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Love of Lady Georgiana Lennox. Find out more at www.alicemariecrossland.com.

Content of this post and all images © Alice Achache

The post Lady Georgiana Lennox and her adventures with the 1st Duke of Wellington appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

August 18, 2017

Indoor fun and games

With rain pouring outside today, my thoughts have turned to indoor games. A quadrille is a dance but it’s also a card game for four players (via French from Spanish cuadrilla, diminutive of cuadro (square), from Latin quadra). Given the flirtatious looks between these four and their friends, it’s clear there’s more than just cards in play. And it’s no surprise to learn that this image was used to decorate the supper boxes at that den of intrigue Vauxhall Gardens. I’m rather fond of the expressions on the maid’s and the enslaved boy’s faces, as if they have seen it all before.

A Game of Quadrille (c. 1740), Hubert-François Gravelot (French, active in Britain (1733–45). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund, in honor of Brian Allen, Director of Studies, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (1993-2012)

A Game of Quadrille (c. 1740), Hubert-François Gravelot (French, active in Britain (1733–45). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund, in honor of Brian Allen, Director of Studies, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (1993-2012)At the far end of the Georgian era is this 1837 depiction of a game of hazard, an all-male affair with complicated rules, involving the roll of 2 dice (or more accurately, as my English teacher used to insist, die). Several players have clearly run out of luck; one is leaving the room clutching his head and another sits, abject, in a corner. Crockford’s Club, in St James’s Street, was known for its hazard playing.

The Hazard Room at Crockford’s, 1837. T. J. Rawlins. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

The Hazard Room at Crockford’s, 1837. T. J. Rawlins. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.More head-clutching in this depiction of chess, but it’s more of the thinking rather than despairing kind. Chess has always been more of an intellectual challenge than a chance to indulge in high-stakes gambling. I love the way Top Left Man looks out from the canvas, quietly inviting us to become part of the scene because he knows we might have something to contribute.

The Chess Players, James Lonsdale (d. 1839). Photo credit: Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

The Chess Players, James Lonsdale (d. 1839). Photo credit: Nottingham City Museums and GalleriesOf course, boardgames were not reserved for the middle-class. This unattributed work from the Scottish School shows middling folk (the one on the left wears a smock) having a jolly time playing drafts (confusing it’s titled the Chess Players), observed by the buxom wife of the house and her slightly odd-shaped baby. Yes, I know they’re not indoors, but perhaps the sun is shining (it’s a lovely autumn day) and they’ve taken advantage of the weather for an hour or two. The man on the right could be a publican and perhaps the woman is his wife.

British (Scottish) School; Chess Players; The National Trust for Scotland, Leith Hall Garden & Estate, c. 1820.

British (Scottish) School; Chess Players; The National Trust for Scotland, Leith Hall Garden & Estate, c. 1820.Finally, an example of the many family boardgames from the Regency era. This one, The Swan of Elegance, is from 1814 and tried to combine fun with moral instruction. There were 31 numbered pictorial compartments, each showing a child engaged in a moral or an immoral deed. The accompanying booklet has a four-line verse explanation for each. Hours of merriment, I’m sure.

The Swan of Elegance: A New Game Designed for the Instruction and Amusement of Youth, 1814 © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Swan of Elegance: A New Game Designed for the Instruction and Amusement of Youth, 1814 © The Trustees of the British MuseumThe post Indoor fun and games appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

August 14, 2017

A sure bet ��� cricket in the Georgian era

A Game of Cricket (The Royal Academy Club in Marylebone Fields, now Regent’s Park). Unknown artist, after Francis Hayman (between 1790 and 1799). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

A Game of Cricket (The Royal Academy Club in Marylebone Fields, now Regent’s Park). Unknown artist, after Francis Hayman (between 1790 and 1799). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.Cricket, whose rules were codified in 1744 (although its origins stretch back to the Middle Ages), only really became popular when its potential as another opportunity for aristocrats to bet became apparent.

Games at Vauxhall: Playing at Cricket (c. 1743), Print made by Guillaume Philippe Benoist. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Games at Vauxhall: Playing at Cricket (c. 1743), Print made by Guillaume Philippe Benoist. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.From time to time, perhaps to spice up the bets, unusual matches were organised. In 1766 at Blackheath, south-east of London, 11 Greenwich pensioners who had each lost an arm faced 11 who had lost a leg. The one-armed team won. Thirty years later, one-legged and one-armed teams of Greenwich pensioners played for bets of thousand guineas at Montpellier Gardens in Walworth (just south of the Elephant and Castle). The one-legs beat the one-arms by 103 runs. Afterwards, the winning team took part in hundred-yard ‘running’ races.

Aside: To anyone looking for a laugh I recommend The Pursuit of Cricket under Difficulties in Charles Dickens’ All the Year Round. 1

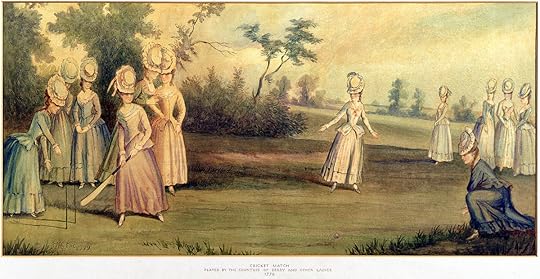

A 1779 cricket match played by the Countess of Derby and other ladies. English School 18th century, initials visible in bottom left hand corner, possibly JH. Public Domain.

A 1779 cricket match played by the Countess of Derby and other ladies. English School 18th century, initials visible in bottom left hand corner, possibly JH. Public Domain.A 1779 cricket match played by the Countess of Derby and other ladies. English School 18th century, initials visible in bottom left hand corner, possibly JH. – zoetakingthefield, originally from Bridgeman Art Library. Restored by Harrias (scratch removal, minor rotation). Public Domain, Link.

Women’s cricket was not unknown, the first recorded match being between Bramley and Hambleton in Surrey. In 1775 at Moulsey Hurst (near West Molesey, Surrey), there was a match between teams of six married and unmarried women, with the singletons winning. Betting was ‘great’. 2

Another notable women’s match took place in 1811 at Ball’s Bond, near Newington Green between teams from Hampshire and Surrey, arranged for a wager by ‘two noblemen’, each betting five hundred guineas. The players ranged from 14 to 60-year-old Ann Baker, who was ‘the best runner and bowler’ on the Surrey side. Hampshire won, after which the players went to the Angel, Islington for a slap-up entertainment. 3

Notes:

1866. Vol 6, p33. ↩Cricketing information from The Recreative Review, or Eccentricities of Literature and Life (1822). Vol 3. London: J. Wallis. Quoting Dodsley, 1774. ↩Pierce Egan’s Book of Sports, and Mirror of Life Embracing the Turf, And Mirror of Life (1836). London: Thomas Tegg and Sons ↩The post A sure bet – cricket in the Georgian era appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

August 7, 2017

In sickness and in health: a late Georgian aristocratic marriage ��� John Pitt, the Earl of Chatham, and Mary Elizabeth Townshend

I am thrilled to welcome Jacqueline Reiter to the blog today. Jacqueline has a PhD in late 18th-century political history from the University of Cambridge. A professional librarian, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children. She blogs at www.thelatelord.com and you can follow her on Facebook (www.facebook.com/latelordchatham) or Twitter (https://twitter.com/latelordchatham). Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was published by Pen & Sword Books in January 2017.

I am thrilled to welcome Jacqueline Reiter to the blog today. Jacqueline has a PhD in late 18th-century political history from the University of Cambridge. A professional librarian, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children. She blogs at www.thelatelord.com and you can follow her on Facebook (www.facebook.com/latelordchatham) or Twitter (https://twitter.com/latelordchatham). Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was published by Pen & Sword Books in January 2017.

Historical aristocratic marriages do not always come across positively, partly because most such marriages that are remembered today stick in the mind because of their disastrous nature. The late Georgian period alone is full of such tales, from the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire’s curious ménage-à-trois with Lady Elizabeth Foster, through public divorce sensations like Sir Richard and Lady Worsley, to the most infamous celebrity mismatch of the period, the Prince of Wales and Caroline of Brunswick.

Sometimes, of course, aristocratic marriages were successful, as I had the pleasure of discovering while researching my biography of the 2nd Earl of Chatham, the elder brother of British prime minister William Pitt the Younger. In a period so apparently full of failure, Lord and Lady Chatham’s 38-year marriage was a model of tranquility. Unfortunately, in this case, a happy marriage did not automatically mean a happy ending.

John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, married Mary Elizabeth Townshend on 10 July 1783. Their courtship was long and rather drawn-out on Lord Chatham’s part, but probably due to bashfulness rather than reluctance. Their fathers had been close friends and neighbours, and John and Mary had known each other since they were children. Their names had been paired up as early as 1779, when Mary was 16 and John 22.

John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, studio of John Hoppner (1799, courtesy of the Commando Forces Officers’ Mess, Royal Marines Barracks, Plymouth)

John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, studio of John Hoppner (1799, courtesy of the Commando Forces Officers’ Mess, Royal Marines Barracks, Plymouth)The Pitt and Townshend families were both delighted with the match. Mary’s father, Lord Sydney, wrote to John’s mother of his “Satisfaction & Pride in placing a Part of my Family, which deserves & possesses my warmest & most tender Affection, under the Protection of those, whose Alliance, I can truly say, I prefer to that of any Family in England”. 1 Twelve years later, John’s mother still had no doubt her son had made the right choice. She told Lord Sydney: “I have been always proud of the Prize obtain’d by my Son Chatham, from your Family.” 2

John and Mary’s feelings are less easy to work out, as no letters between them survive. This itself, however, testifies to their closeness, as for the first 24 years of their marriage they seem to have been rarely apart. Even when Chatham, a soldier by profession, went off on campaign, Lady Chatham followed him as far as she could. She took her duties as a soldier’s wife seriously: she regularly accompanied her husband on the parade ground, watching manoeuvres from an open carriage, and she was by his side throughout his military district postings, moving from barrack to barrack in Winchester, Chatham, Eastbourne and Colchester. This did not mean she enjoyed watching her husband march off to war. “As to his fighting again, I believe I had better not answer that at all, for fear of being a little warm,” she wrote during the brief Peace of Amiens in 1802. “…I believe I may as sincerely wish the Peace to last, as a friend to my Country, as I do as a Wife.” 3

Seal of Lord Chatham, showing his arms impaling those of his wife (private collection)

Seal of Lord Chatham, showing his arms impaling those of his wife (private collection)The strength of their marriage, however, was far more obvious when things were going wrong than when they were going right. Tragically for the Chathams, things often went very wrong right from the start. For two years from April 1784 Mary was almost completely crippled by some sort of rheumatic disorder in her knee and hip, and she walked with a limp for the rest of her life. She remained reasonably healthy for the next 20 years, but in 1806 her health again collapsed. For several weeks she was afflicted by a “delirious fever” and unable to leave her bed. 4 Physically she was back to normal by the end of the year, but her mental health continued to decline.

By 1807, Mary Chatham was what we would now describe as clinically depressed. She continued appearing in public life – her husband was, after all, a cabinet minister – but the strain of keeping up a pretence of normality was distressingly obvious to her family. Her unmarried sister Georgiana kept Mary’s doctor, Henry Vaughan (later Sir Henry Halford), updated on her outbursts of violence, shocking language and threats of suicide. Following what was probably an unsuccessful attempt to end her life in October 1807, Mary at last disappeared from public life. She did not return to it for two years.

Sir Henry Halford (Wikipedia Commons)

Sir Henry Halford (Wikipedia Commons)The impact of Lady Chatham’s illness on her marriage was worse than anything she and her husband had ever experienced. At first, Chatham refused to believe what was happening. He was always inclined to pretend that tremendous personal crises did not exist, and it took him months to realise his wife was extremely ill. “Nobody thinks her well, but him,” Georgiana Townshend remarked sadly. 5 Eventually, of course, Chatham could no longer hide from the truth, and he and Mary spent much of the following two years apart as she recovered and he tried to focus on his public career.

Remarkably, their marriage survived. When Mary recovered in 1809, the pair returned to public life together as though nothing had happened. This is not to say Mary’s illness did not leave deep scars. Hints that their relationship was overshadowed by the fear of relapse appeared in Chatham’s private correspondence. He kept bad news from her, made decisions alone, and admitted he tried his best to “make everything appear to the best”. 6

Chatham was right to be worried, although for nine years Lady Chatham was perfectly healthy. In March 1818, however, she relapsed. The symptoms of violence, self-harm and deep depression were almost exactly the same. This time Chatham, by now out of office, nursed his wife more or less alone. He was now in his mid-sixties himself, and friends noticed the effects of the strain on his health: “He cannot much longer support such a scene of suffering.” 7 Chatham was eventually persuaded to hire a “companion” skilled in cases of insanity to allow himself a few days of relief, but to his credit he strongly resisted his doctor’s suggestions of straitjacketing, and never failed to add Lady Chatham’s remembrances to his letters, even when she was at her worst. (This was in stark contrast to Lady Chatham’s doctor, who referred to her as a “poor Creature”.) 8

The end came on 21 May 1821, and it was just as tragic as the rest of the story. At five in the evening Lady Chatham, who had been ill, took a glass of barley water and brandy mixed with laudanum and went early to bed. She never woke up. Chatham was at dinner with a guest at the time; it was his guest who found Mary lying as though in a deep sleep, “without a feature altered”. 9

Friends and family expressed relief that she was at last relieved from her suffering, but Chatham was devastated. He did not recover from losing his wife for at least a year, and displayed signs of profound depression far beyond that. Despite her mental problems, Mary had still been the only family he had left.

Mary Elizabeth, Countess of Chatham, possibly by Edward Miles, 1789 (private collection)

Mary Elizabeth, Countess of Chatham, possibly by Edward Miles, 1789 (private collection)On Chatham’s death in 1835, one of the heirlooms passed down to his executors – his great-nephews, as he and his wife never managed to have any children of their own – was a portrait miniature of Mary Chatham from 1789. The miniature is still in the family’s possession today. It depicts a fresh-faced, 26-year-old girl dressed to the height of fashion, peering coyly at the viewer from under an enormous hat. To Chatham, the miniature must have been memories of happy times.

Notes:

Lord Sydney to Lady Chatham, 5 June 1783, TNA Chatham Papers PRO 30/8/60 f 205. ↩Dowager Lady Chatham to Lord Sydney, 2 February 1795, Huntington Library Townshend Family Papers TD 284. ↩Lady Chatham to Mrs Stapleton, undated, National Army Museum Combermere MSS 8408-114. ↩The Bishop of Lincoln to his wife, 31 January 1806, Suffolk Record Office Pretyman-Tomline MSS HA 119/T99/26. ↩[Georgiana Townshend] to Dr Vaughan, 14 April [1807], Leicestershire Record Office Halford MSS DG 24/819/1. ↩Chatham to Mrs Stapleton, 2 December 1810, National Army Museum Combermere MSS 8408-114. ↩Elizabeth Tomline to Sir Henry Halford, [September 1819], Suffolk Record Office Pretyman-Tomline MSS HA 119/562/716. ↩Sir Henry Halford to Elizabeth Tomline, 10 September 1819, Suffolk Record Office Pretyman-Tomline MSS HA 119/562/716. ↩William Sloane to the Duke of Rutland, 22 May 1821, Belvoir Castle Manuscripts. ↩The post In sickness and in health: a late Georgian aristocratic marriage – John Pitt, the Earl of Chatham, and Mary Elizabeth Townshend appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

August 2, 2017

The buildings of Georgian Whitehall and Westminster: Houses of Parliament

Before the fire of 1834, members of the House of Commons sat in the secularised Royal Chapel of St Stephen, a two-storey building with high turrets at each corner, which had been extensively remodelled by Sir Christopher Wren in 1692. Facilities were notoriously cramped and inconvenient.

Thompson, The Houses of Parliament with the Royal Procession (1804). The Chapel of St Stephen, where the Commons sat, is on the left. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

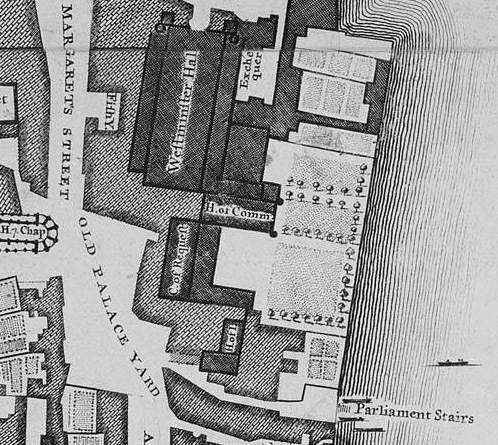

Thompson, The Houses of Parliament with the Royal Procession (1804). The Chapel of St Stephen, where the Commons sat, is on the left. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon CollectionIn the early 19th century, as part of a redevelopment programme, James Wyatt moved the Lords into the Court of Requests. John Rocque’s map shows the positions of the Houses of Commons and Lords in 1746.

Detail of John Rocque’s map of London (1746). Courtesy of MOTCO via Wikimedia

Detail of John Rocque’s map of London (1746). Courtesy of MOTCO via WikimediaThe Palace of Westminster was a firetrap and MPs and architects, including Soane, had been predicting disaster since at least the late 18th century. In 1828, Soane warned that ‘the want of security from fire, the narrow, gloomy and unhealthy passages, and the insufficiency of the accommodations in this building are important objections which call loudly for revision and speedy amendment.’ He was ignored.

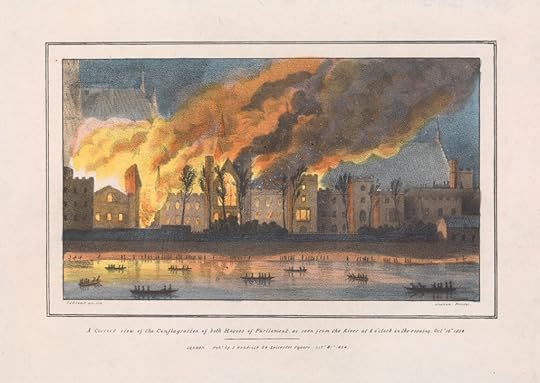

The catastrophic fire of 16 October 1834 arose, bizarrely, from an archaic way of accounting used by the Court of Exchequer. Until 1826, when the Court was abolished, it had kept records of payments using a system of tallies, elm or willow wood sticks split in half (one half was retained by the Exchequer, the other half acted as a receipt). A decision was made to burn the now redundant sticks, two cartloads full, in furnaces directly under the House of Lords.

Charles Jameson Grant, A Correct View of the Conflagration of Parliament as Seen from the River at 8 o’clock in the Evening Oct. 16th 1834 (1834). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Charles Jameson Grant, A Correct View of the Conflagration of Parliament as Seen from the River at 8 o’clock in the Evening Oct. 16th 1834 (1834). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.The fire was first spotted at around 6 o’clock that evening and half an hour later there was a massive flashover, followed by an explosion. At 7pm James Braidwood, 1 who had been appointed the first Superintendent of the London Fire Engine Establishment only 18 months previously, was alerted and arrived at the scene 25 minutes later with 14 or 15 engines and 66 firefighters, just as the roof of the House of Lords crashed in.

James Braidwood, via Wikimedia Commons

James Braidwood, via Wikimedia CommonsThe fire, which was the largest in London since 1666, lit up the skyline of London and could be seen by the Royal family at Windsor. It burned all night and the damage was extensive. St Stephen’s Chapel, the Lords, the Painted Chamber and the official residences of the Speaker and the Clerk of the House of Commons were destroyed. Braidwood’s decision to focus efforts on saving as much as possible from the relatively unaffected areas while abandoning the buildings obviously beyond salvation meant that St Mary Undercroft, Westminster Hall, the Cloisters and the Jewel Tower survived.

The 1834 destruction of both Houses of Parliament by fire via Wikimedia Commons.

The 1834 destruction of both Houses of Parliament by fire via Wikimedia Commons.Recommended reading: Shenton, C., (2012). The Day Parliament Burned Down. Oxford: OUP.

Notes:

Braidwood (b. 1800) died on active service on 22 June 1861 near Tooley Street in south-east London. ↩The post The buildings of Georgian Whitehall and Westminster: Houses of Parliament appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

July 31, 2017

The buildings of Georgian Whitehall and Westminster: Horse Guards, Dover House

This morning I was on the 88 bus heading south down Whitehall. Despite the braying of a Westminster policy wonk sitting behind me, as always I loved seeing the wonderful buildings (my favourites are Georgian, of course). To lighten the gloom of current times, here are some views of the area made in earlier (though not necessarily more tranquil) times.

We’ll start with this 18th-century view looking south, with Banqueting House on the left and the Tudor Holbein Gate ahead. 1

Whitehall, London (British School, early 18th century) looking south, showing Banqueting House on the left. Courtesy of National Trust Collections. Photo credit: National Trust Images

Whitehall, London (British School, early 18th century) looking south, showing Banqueting House on the left. Courtesy of National Trust Collections. Photo credit: National Trust ImagesHere is Holbein Gate, this time, depicted from the south looking north, in a print by Thomas Sandby, 2 which the Yale Center for British Art dates as 1760 but is possibly earlier. The Gate was demolished in 1759. 3

Thomas Sandby, Whitehall Showing Holbein’s Gate and Banqueting Hall (1760). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Thomas Sandby, Whitehall Showing Holbein’s Gate and Banqueting Hall (1760). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.Still looking north, perhaps from about the spot where Holbein Gate once stood, here is William Marlow’s 1775 view. In the distance is King’s Mews, 4 where Trafalgar Square is now. Banqueting House is on the right and you can see Horse Guards (built 1750-1753) on the left – note the sentry boxes. The spire of St Martin in the Fields rises above the buildings.

William Marlow, Whitehall (c. 1775). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

William Marlow, Whitehall (c. 1775). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.This print, showing a detailed view of Horse Guards, by Thomas Malton the Younger, probably from the late 18th century or early 19th, is my favourite. Note the genteel lady on the left conversing with or giving alms to the beggar woman.

Horse Guards, Whitehall, Thomas Malton the Younger (1748-1804), undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

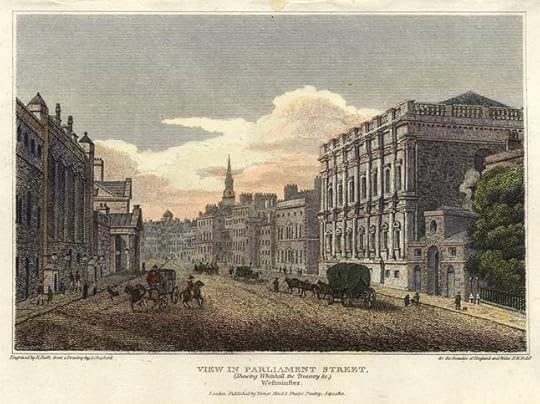

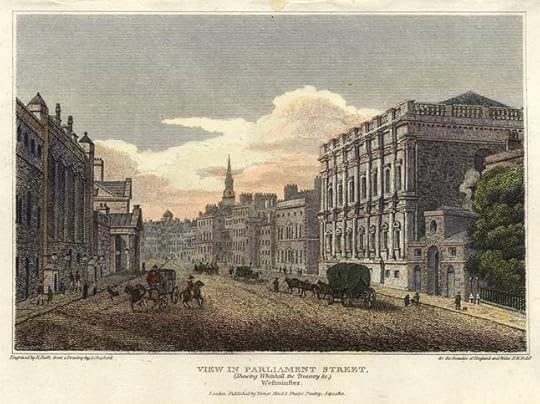

Horse Guards, Whitehall, Thomas Malton the Younger (1748-1804), undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.A print from 1810 from The Beauties of England offers a roughly similar aspect to the William Marlow.

Parliament Street, (Showing Whitehall, Treasury &c.) Westminster, published in The Beauties of England and Wales (1810). Courtesy of ancestryimages.com

Parliament Street, (Showing Whitehall, Treasury &c.) Westminster, published in The Beauties of England and Wales (1810). Courtesy of ancestryimages.comBanqueting House has not changed a great deal since it was completed in 1622. Inigo Jones’s building replaced an earlier one, which was destroyed when workmen decided to burn rubbish inside. Here is a relatively recent view.

Banqueting House, Whitehall, 2004 (ChrisO, 2004), Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license.

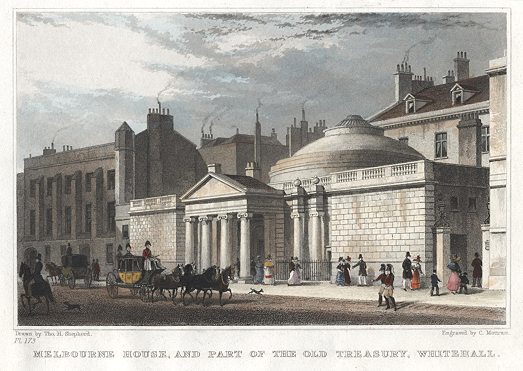

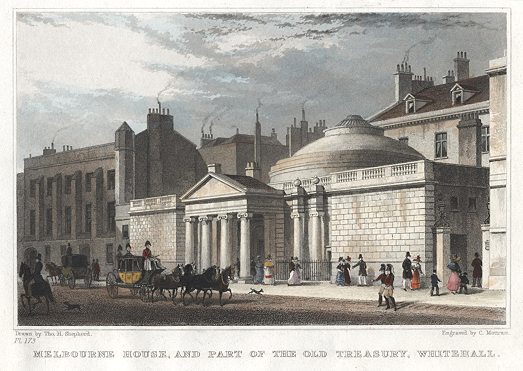

Banqueting House, Whitehall, 2004 (ChrisO, 2004), Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license.Melbourne House, on the right as you look south, is now called Dover House and accommodates the Scotland Office. Originally designed as a private residence, it was occupied by, among others, the 1st Duke of Montagu, Prince Frederick, Duke of York, and Lady Caroline Lamb. 5 Note the smoking chimneys.

Melbourne House, and part of the Old Treasury, Whitehall, engraved by C. Motram after T.H. Shepherd, published in London in the Nineteenth Century, (1831).

Melbourne House, and part of the Old Treasury, Whitehall, engraved by C. Motram after T.H. Shepherd, published in London in the Nineteenth Century, (1831).An up-to-date view (no smoking chimneys).

Dover House, Whitehall by Steve Cadman. CC BY-SA 2.0

Dover House, Whitehall by Steve Cadman. CC BY-SA 2.0Notes:

Holbein Gate (also known as the King’s Gate or the Cockpit Gate) was built by Henry VIII and survived until its demolition in 1759. ↩Brother of Paul Sandby. ↩Brother of Paul Sandby. ↩This was an area where the royal hawks were once kept; the mews were rebuilt as stables in the 16th century, but these were moved to Buckingham Palace by George IV. The construction of Trafalgar Square finished in 1844. ↩Lady Caroline Lamb was obsessed with Lord Byron during her marriage to William Lamb, who later became Lord Melbourne ↩The post The buildings of Georgian Whitehall and Westminster: Horse Guards, Dover House appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

Georgian Whitehall and Westminster

This morning I was on the 88 bus heading south down Whitehall. Despite the braying of a Westminster policy wonk sitting behind me, as always, I loved seeing the wonderful buildings (my favourites are Georgian, of course). To lighten the gloom of current times, here are some views of the area made in earlier (though not necessarily more tranquil) times.

We’ll start with this 18th-century view looking south, with Banqueting House on the left and the Tudor Holbein Gate ahead. 1

Whitehall, London (British School, early 18th century) looking west, showing Banqueting House on the left. Courtesy of National Trust Collections. Photo credit: National Trust Images

Whitehall, London (British School, early 18th century) looking west, showing Banqueting House on the left. Courtesy of National Trust Collections. Photo credit: National Trust ImagesHere is Holbein Gate, this time, depicted from the south looking north, in a print by Thomas Sandby, 2 which the Yale Center for British Art dates as 1760 but is possibly earlier. The Gate was demolished in 1759. 3

Thomas Sandby, Whitehall Showing Holbein’s Gate and Banqueting Hall (1760). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Thomas Sandby, Whitehall Showing Holbein’s Gate and Banqueting Hall (1760). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.Still looking north, perhaps from about the spot where Holbein Gate once stood, here is William Marlow’s 1775 view. In the distance is King’s Mews, 4 where Trafalgar Square is now. Banqueting House is on the right and you can see Horse Guards (built 1750-1753) on the left – note the sentry boxes. The spire of St Martin in the Fields rises above the buildings.

William Marlow, Whitehall (c. 1775). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

William Marlow, Whitehall (c. 1775). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.This print, showing a detailed view of Horse Guards, by Thomas Malton the Younger, probably from the late 18th century or early 19th, is my favourite. Note the genteel lady on the left conversing with or giving alms to the beggar woman.

Horse Guards, Whitehall, Thomas Malton the Younger (1748-1804), undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Horse Guards, Whitehall, Thomas Malton the Younger (1748-1804), undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.A print from 1810 from The Beauties of England offers a roughly similar aspect to the William Marlow.

Parliament Street, (Showing Whitehall, Treasury &c.) Westminster, published in The Beauties of England and Wales (1810). Courtesy of ancestryimages.com

Parliament Street, (Showing Whitehall, Treasury &c.) Westminster, published in The Beauties of England and Wales (1810). Courtesy of ancestryimages.comBanqueting House has not changed a great deal since it was completed in 1622. Inigo Jones’s building replaced an earlier one, which was destroyed when workmen decided to burn rubbish inside. Here is a relatively recent view.

Banqueting House, Whitehall, 2004 (ChrisO, 2004), Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license.

Banqueting House, Whitehall, 2004 (ChrisO, 2004), Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license.Melbourne House, on the right as you look south, is now called Dover House and accommodates the Scotland Office. Originally designed as a private residence, it was occupied by, among others, the 1st Duke of Montagu, Prince Frederick, Duke of York, and Lady Caroline Lamb. 5 Note the smoking chimneys.

Melbourne House, and part of the Old Treasury, Whitehall, engraved by C. Motram after T.H. Shepherd, published in London in the Nineteenth Century, (1831).

Melbourne House, and part of the Old Treasury, Whitehall, engraved by C. Motram after T.H. Shepherd, published in London in the Nineteenth Century, (1831).An up-to-date view (no smoking chimneys).

Dover House, Whitehall by Steve Cadman. CC BY-SA 2.0

Dover House, Whitehall by Steve Cadman. CC BY-SA 2.0Notes:

Holbein Gate (also known as the King’s Gate or the Cockpit Gate) was built by Henry VIII and survived until its demolition in 1759. ↩Brother of Paul Sandby. ↩Brother of Paul Sandby. ↩This was an area where the royal hawks were once kept; the mews were rebuilt as stables in the 16th century, but these were moved to Buckingham Palace by George IV. The construction of Trafalgar Square finished in 1844. ↩Lady Caroline Lamb was obsessed with Lord Byron during her marriage to William Lamb, who later became Lord Melbourne ↩The post Georgian Whitehall and Westminster appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

July 24, 2017

Summer scenes from the Georgian era

It’s July, it’s raining for days and I’m shivering. So, to cheer us all up and in hommage to the joys of the British summer, here are five images from the long 18th century related to the season.

Let’s start with an idealised bucolic scene (undated) by the London-born painter and illustrator Richard Corbould (1757–1831), illustrating a line from the poet James Thomson’s The Seasons:

and by turns relieves

The ruddy milkmaid with her brimming pail;

Richard Corbould, 1. Summer. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Richard Corbould, 1. Summer. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon CollectionThomas Rowlandson was more knowing. He has to be my favourite Georgian artist: so vital and and (often) so naughty. Even when the participants in the scene look as if they are behaving respectably, he manages to suggest that that will change the minute you look away. I’ve got a feeling this Shakespearian-y group (note the flute and the leggings) will shortly be very much inspired by the nature around them.

Thomas Rowlandson, 1. (18101815). A Summer Idyll. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Thomas Rowlandson, 1. (18101815). A Summer Idyll. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.In his early career, James Ward painted anecdotal genre scenes, such as this 1800 work titled The Reapers (but also known as The Gleaners). I am not sure how to interpret the story, but note the tension between the players and the lowering sky. The elevation of the genteel woman on her horse is in direct opposition to the poor woman working on the wheat sheaves. Despite the difference in their dress, they look as if they could be related (did Ward use the same model?). I am very fond of the sleeping baby in the bottom left. The summer harvest was a busy time and women had to squeeze in work around family duties.

James Ward, 1. (1800). The Reapers.

James Ward, 1. (1800). The Reapers.I love The Summer Room in the Artist’s House at Patna by Sir Charles D’Oyly (1781-1845), created in 1824 for D’Oyly’s sister Mrs Snow. The warmth and light in the scene show clearly that we are not England, but it’s only the tigerskin rug and the hookah that suggest it is India. D’Oyly was born there and spent 40 years of his life in the service of the East India Company. His various roles included Opium Agent of Bihar, perhaps appropriately enough.

Sir Charles D’Oyly, 1. (1824). The Summer Room in the Artist’s House at Patna. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

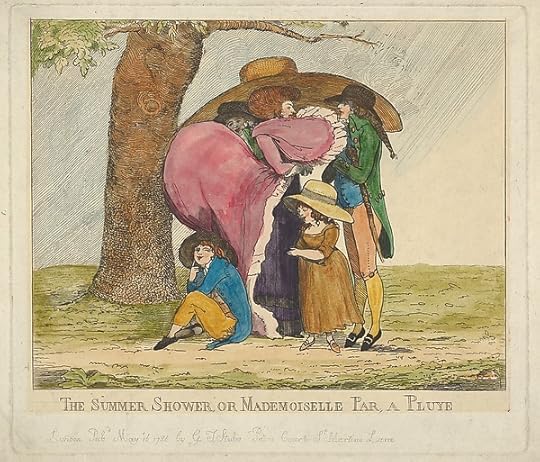

Sir Charles D’Oyly, 1. (1824). The Summer Room in the Artist’s House at Patna. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.And finally, back to the summer rain… This cartoon pokes fun at contemporary fashion extremes (for caricaturists an age-old butt, if you excuse the pun) but also perhaps (well, for me at least) it’s an illustration of how women provide physical and metaphorical protection against the vicissitudes of life.

Anonymous, British, 18th century

Anonymous, British, 18th centuryThe Summer Shower, or Mademoiselle Par, a Pluye, May 16, 1786.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1971 (1971.564.190-)

The post Summer scenes from the Georgian era appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

July 16, 2017

The Yorkshire schools in court: 1816

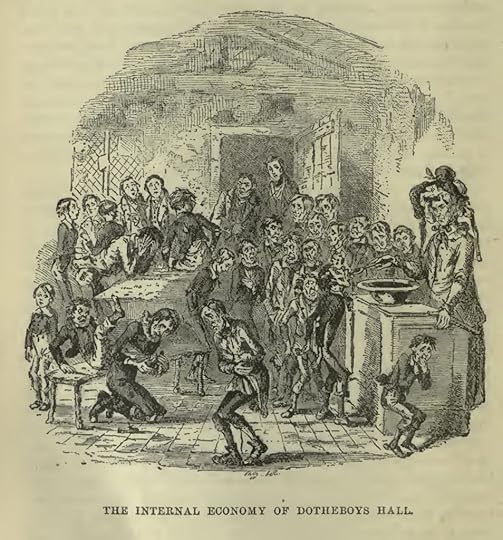

The Internal Economy of Dotheboys Hall, by “Phiz”, for Nicholas Nickleby (1838-9), which was set in the mid 1820s.

Pale and haggard faces, lank and bony figures, children with the countenances of old men, deformities with irons upon their limbs, boys of stunted growth, and others whose long meagre legs would hardly bear their stooping bodies, all crowded on the view together; there were the bleared eye, the hare-lip, the crooked foot, and every ugliness or distortion that told of unnatural aversion conceived by parents for their offspring, or of young lives which, from the earliest dawn of infancy, had been one horrible endurance of cruelty and neglect.

Charles Dickens describes the Dotheboys pupils, Nicholas Nickleby, 1838-9

The flying visit Charles Dickens and his illustrator Hablot “Phiz” Browne paid in 1838 to Greta Bridge, a newspaper cutting about ‘The Cruelty of a Headmaster’ in his pocket, is well known. Dickens was on a mission to investigate the business of the ‘prison schools’ of Yorkshire and Teesside and wanted to meet William Shaw who had been prosecuted in 1823 for causing some of his pupils to go blind. Shaw was fined the huge sum of £600,but seemed to shrug it off and merely returned home to continue to run his business.

Pretending to acting for a widow hoping to place her son at the school and looking for guidance, Dickens introduced himself to a local solicitor, Richard Barnes, who outlined the local options. Later, Barnes appeared at the inn where Dickens was staying to warn him off.

‘I’m dom’d if ar can gang to bed and not telee, for the weedur’s sak, to keep the lattle boy from our schoolmeasthers,’ he said. Dickens used him as the model for the hero John Browdie in Nicholas Nickleby.

During his trip, Dickens tried to visit Shaw’s academy at Bowes but was refused at the door, Shaw having been forewarned that a writer was nosing around the area. In their brief encounter, however, Dickens noted that Shaw had lost an eye and used this as a characteristic of Wackford Squeers, the hilariously corrupt and ignorant proprietor of Dotheboys Hall. He found another character while at Bowes: while walking in the churchyard he saw, among the many graves of schoolchildren, a headstone for George Ashton Taylor, who had died at Shaw’s Academy in 1822, aged 19. He was the inspiration for Smike.

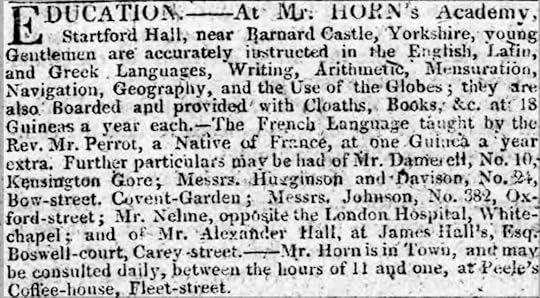

Many well-meaning but impecunious parents (widows on small incomes for instance or widowers suddenly in charge of large numbers of children) placed their children in what were called the Yorkshire Schools. After all, the advertisements promised great things:

Mr Horn’s Academy at Startford Hall near Barnards Castle, North Yorkshire, Morning Advertiser, 18 July 1809 1C.

Some parents were more keen on the convenience offered by the schools, which were perfect for people whose offspring were in some way inconvenient, usually because of their illegitimacy or disability. The cost was relatively low: each child could be lodged permanently for around £20 a year, often all year round. Dickens included this feature in his fictional ad for Dotheboys Hall which was almost a verbatim copy of one for Bowes Academy printed in The Times in 1817. The school at Cotherstone in the North Riding of Yorkshire run by Joseph Watson and Charles Atkinson, who had bought it from the Reverend Joseph Adamthwaite, also offered this option.

[image error]

Watson and Atkinson advertise the school in the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 28 June 1814 1A.

In 1814, Joseph Death, of Shoreditch, the father of ten children, met Mr Watson’s son, also called Joseph, in London and agreed terms for two of his sons, Jeremiah, who was about seven, and Francis, six. They were to bring their own clothes but the school would provide great coats, the cost of which would be charged back to Mr Death. Death no doubt assumed that the boys would thrive in the country air in a spartan but caring environment.

William Garrow in 1810, courtesy of Harvard University Library, olvwork178120

The reality was quite different. The house was freezing cold; its one schoolroom was equipped only with one tiny stove and no chairs. The boys’ clothes were appropriated and they were made to wear thin rags and wooden clogs. The food was cheap and poor quality. The boys soon became were infested with vermin and covered in sores. A local cobbler, Watson’s brother-in-law, taught reading and writing. There was no instruction in Latin or Greek.

A Mr Smith, whose own son Thomas was at the Cotherstone school, learned about the appalling conditions from some former pupils. Alarmed, he went to see Joseph Watson Jr when he was next in London and and demanded Thomas’s immediate return. In January, when Thomas failed to appear, he decided to travel to Cotherstone to collect him, first informing other parents of his acquaintance, including Mr Death and others, who asked him to collect his boys at the same time.

Smith found the boys in a shocking state. They were all undernourished, wearing rags and freezing cold. The great coats had failed to materialise. Francis Death’s feet were covered in infected sores. In all, Smith removed seven boys and travelled back to London with them.

Understandably, Mr Death refused to settle his bill with the school. In March 1816 Watson and Atkinson sued him, little thinking that even a successful prosecution might not do them much good in the long run. The case was heard by Lord Ellenborough, the reactionary Lord Chief Justice, prosecuted by Charles Williams and defended by William Garrow, at that time Attorney General. 1

In court, the conditions of the school were exposed – and disputed. Joseph Watson Jr claimed that the Death boys were given greatcoats and pocket money and various other witnesses testified to good food and reasonable care, but the French teacher (it’s somewhat surprising that they did have one) said ‘he would not expose a dog’ to the treatment the boys had to endure, that ‘there was no more knowledge of geometry and geography in the school than an ass had of astronomy’. There were ‘no books, no fire, and he still felt the effects of the frost’. He was forced to lend Watson and Atkinson money, which was not returned, and had been paid wages in linen and calico rather than cash. Unlike the former owner, neither Watson nor Atkinson were ordained ministers of the church. In fact, it transpired that Mr Watson had previously been a butcher. His brother-in-law, a local cobbler, was employed to teach the boys and his 70-year-old wife, whose job it was to care for the boys, spent the days sitting about with another old woman smoking a pipe.

Despite this, and the evidence of Mr Moorhead, a London surgeon, who testified that the Death boys were weak and in bad health from ‘want of nourishment’, the jury found for the plaintiffs, awarding them damages of £17 18s and costs of 40s (£2).

The case hinged on the food. Jeremiah Death said he breakfast, dinner and supper were provided and ‘sometimes’ this included meat, broth, vegetables and ‘brown cake’. Thomas Smith, now aged 14, said that he was given porridge for breakfast and dinners of meat and potatoes. Lord Ellenborough said objections to such food ‘arose out of the foolish luxury of the metropolis’ and asked the jury whether this could really be described as ‘starving’. In his opinion, the breakfast sounded very wholesome.

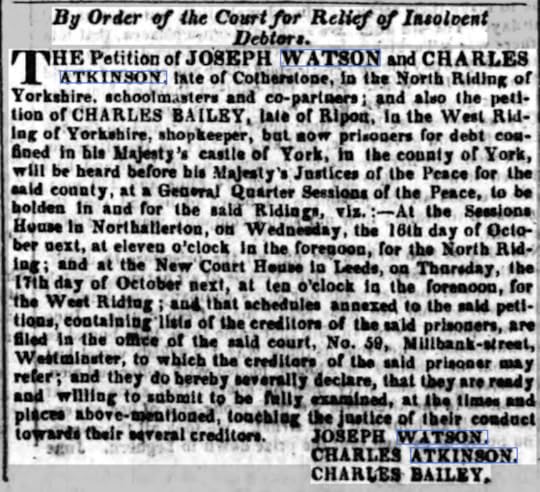

It was a pyrrhic victory for Watson and Atkinson because the case killed off their business. By September of 1816 they were imprisoned in York Castle for debt and petitioning for insolvency relief.

Durham County Advertiser, 21 September 1816 3C.

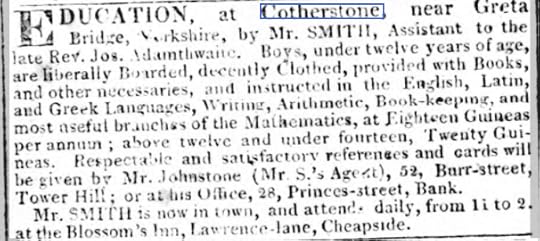

The school itself continued under new management, run by a Mr Smith (no relation to the man who retrieved his son from the school). His ad made no mention of Watson and Atkinson but emphasised his credentials as a protégé of Mr Adamthwaite. The boys were ‘liberally’ boarded.

Morning Advertiser, 4 January 1819 1B.

Shaw’s Academy closed, along with many others, in 1840.

Further reading

John Sutherland, Nicholas Nickleby and the Yorkshire schools (British Library)

Notes:

The Observer, 3 March 1816. ↩The post The Yorkshire schools in court: 1816 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

July 9, 2017

Silk: From Spitalfields to Sudbury at Gainsborough���s House

This small but exquisite exhibition tracing the history of silk in England from the 18th century to the present day is on until 8 October 2017 at Gainsborough’s House in Sudbury, Suffolk. It focuses on the diaspora of silk manufacture from Spitalfields in east London to Sudbury and draws together artworks and textiles from national and local collections.

This small but exquisite exhibition tracing the history of silk in England from the 18th century to the present day is on until 8 October 2017 at Gainsborough’s House in Sudbury, Suffolk. It focuses on the diaspora of silk manufacture from Spitalfields in east London to Sudbury and draws together artworks and textiles from national and local collections.

A page from the Wilson Album from Vanners Silk Mill via gainsborough.org

The objects include silk pattern books and historic costume, and paintings and drawings featuring silk fashions of the era but my favourites were examples of the astonishingly beautiful designs of Anna Maria Garthwaite.

Little-known fact: Sudbury is still a centre of silk production. Nearly 95 per cent of the UK’s woven silk textiles is produced by three working mills: Vanners Silk Weavers, Stephen Walters & Sons and Gainsborough Silks.

The silk trade was dominated by Huguenot (Protestant) emigrés fleeing the persecution in France and their descendants. Quite coincidentally, I happened to come across a sweet chapter about the last of Spitalfields Huguenot weavers in Ghosts of London by the journalist V. H. Morton (published in 1939), a book left to me by my father. The life of the elderly brother and sister (whose surname is Poyton) probably has not changed much since that of their ancestors in the 18th century. Morton says that they are among only 16 to 18 remaining weavers:

The silk trade was dominated by Huguenot (Protestant) emigrés fleeing the persecution in France and their descendants. Quite coincidentally, I happened to come across a sweet chapter about the last of Spitalfields Huguenot weavers in Ghosts of London by the journalist V. H. Morton (published in 1939), a book left to me by my father. The life of the elderly brother and sister (whose surname is Poyton) probably has not changed much since that of their ancestors in the 18th century. Morton says that they are among only 16 to 18 remaining weavers:

‘In a neat little house in a dreary street on the boundary of Spitalfields an old man and his sister work all day at two hand looms. Those complicated structures, which even science has not been able to simplify, occupy the entire bedroom space in the house and, as you go in, you must press yourself into a narrow space between the looms.’

The Poytons worked from 8am to 8pm and continued after dark, their work lit by oil lamps. They knew that silkweaving was in steep decline in Spitalfields (their trade was reduced to piece work, and they were then weaving silk for Old Etonian ties) and complained that young people refused to toil from dawn to dark, preferring jobs that allowed them to ‘get off to the cinema and to the dance hall’.

The post Silk: From Spitalfields to Sudbury at Gainsborough’s House appeared first on Naomi Clifford.