Naomi Clifford's Blog, page 11

January 18, 2017

Some early 19th-century prison escapes

In 2015 I wrote about the 1816 escape of six prisoners from Newgate in 1816 (they knotted blankets together) and also of the daring exploits of bank note forger Sarah Chandler, who was sprung from Presteigne gaol in 1814 after she was sentenced to death.

In 2015 I wrote about the 1816 escape of six prisoners from Newgate in 1816 (they knotted blankets together) and also of the daring exploits of bank note forger Sarah Chandler, who was sprung from Presteigne gaol in 1814 after she was sentenced to death.

I have it on good authority (my sister, who for many years was a prison officer) that while some guests of Her Majesty can’t stay out of prison and seem to prefer it to life outside, others will do almost anything to get out, and will attempt to do so even if legal release is imminent. Of course, the fact of being under (or expecting) sentence of death or of transportation would naturally increase the motivation to leave.

Plan for a County Gaol. From John Howard’s The state of the prisons in England and Wales, with preliminary observations, and an account of some foreign prisons and hospitals (1792) Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

The front page of The Newcastle Courant of 15 March 1800 details two escapes, the first from Newgate Prison in Newcastle Upon Tyne (there were several gaols named after the London one). Mr Gale, the keeper, offered five pounds, with the Corporation of Newcastle matching his reward, for the capture of Thomas Graham, who was charged with highway robbery, and for Richard Lowe or Lough, accused of forgery. Graham climbed up the chimney of the prison and consequently had a scratch on the bridge of his nose and grazes on his knees.

In the same paper, there’s a description of John M’Donald (alias Johnson), 22, who had a distinctive mark on the right side of his mouth “as if cut by fighting”, and John Allen (alias Winter), 39, a deserter from the 25th Regiment of Foot and formerly a travelling basket maker, who went missing from Morpeth gaol, both wearing fetters at the time, which might say something about the security, or lack of, at the prison. Five guineas was on offer for each of them.

The Old Tolbooth, Edinburgh. Via Wikipedia Commons.

A report in The Caledonian Mercury (25 May 1801) on the escape of seven convicted men from the Tolbooth in Edinburgh “by cutting the floors, and breaking through sundry divisions in the house” offers an opportunity to visualise the appearance of some of what was termed by the middle class as “the criminal classes”. I’ve picked out some details.

Andrew Holmes: A bookbinder under sentence of death for housebreaking. “Pitted with the small pox” and with a “small lisp” in his speech.

Lauchlan Love: A shoemaker likewise sentenced and also “very much pitted with the small pox”. He had “many blotches and scars on his head”.

Peter Anderson: A former militiaman, sentenced for shopbreaking. “Stout made, fair complexion.”

James Steven alias Douglas: A slater and former seaman. Wore a “blue jacket very much joined or pieced on the breast.”

John Hunter: Convicted of stealing rags. “Swarthy complexion, much pitted with the small-pox … has a large scar, as if with the scurvy, on the lower parts of his cheeks.”

William Maxwell: Former sergeant in the militia, found guilty of sedition, “swarthy complexion, much pitted with the small pox, speaks quick, and has a particular lisp, and has an uncommon rolling in his eyes when speaking.”

John Inglis: A labourer, convicted of horse stealing, six feet tall with a swarthy complexion and a round face.

They sound a rough bunch, but I suspect a good proportion of them were destitute.

Some escape attempts failed, of course. In Horsham in 1814, the would-be fugitives were betrayed by a fellow prisoner. Hannah Knight, who had been capitally convicted in 1813 at Lewes, Sussex for stealing four pound notes from a letter, was respited and her sentence commuted to transportation. During her journey to Newgate in London (from whence she was due to be taken to a ship bound for Botany Bay) she told Mr Smart, who was accompanying her, that that prisoners at Horsham had skeleton keys made of pewter and that they had nearly managed to saw through their leg irons. “The men and women by the help of these keys it seems, got together at their pleasure,” reported the Sussex Advertiser. 1 Hannah was rewarded with a free pardon. 2

The Prisoner, Joseph Wright of Derby (1787 to 1790). Courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

The report of a 1827 escape has a wealth of detail on the method used by prisoners to escape from a “flat” [a self-contained landing] in Glasgow gaol. Using a piece of iron, they cut through the stone around the bolts on their cells and filled the holes with putty. At a prearranged time, they all opened removed the bolts and got into the lobby, and from there into the water closet where they proceeded to cut the iron bar across the frame of a window, hoping to drop down into the yard and get over the perimeter wall. Unfortunately, sturdy iron gratings had been installed on the outside of windows to stop contraband alcohol being passed in and the plan was foiled. When the turnkey entered the flat at 5am the next morning he was alarmed to find all the prisoners in the lobby, but they told him not to be afraid as they knew the game was up. 3The Globe, 10, 13 April 1820.[/ref]

“Compter, Giltspur Street” engraved by R. Acon after a picture by T.H.Shepherd, published in London in the Nineteenth Century, 1831. Image courtesy of ancestryimages.com

Not all crims were lower class of course. In 1820 Lieutenant John Henry Davis (son of Sir John Davis), escaped from the Giltspur Steet Compter, a prison yards from Newgate, where he was awaiting examination on suspicion of a massive forgery of stocks. He simply changed into a suit of livery identical to those of his manservant and, head down, walked past the turnkey, who was ailing with arthritis at the time. Davis and his manservant Samuel Gooding had carefully planned the escape, even down to Gooding wrapping his face in a black silk handkerchief as if he had toothache so that Davis could similarly cover his face from the turnkey on exit, and arranging for a steed to be waiting in nearby Smithfield. On this Davis zoomed off to Croydon, jumped into a chaise and four and headed for Brighton where a boat took him to France. He is thought to have ended up in America. The servant got six months in prison and the turnkey was suspended from duty. 4

Not included here are the exploits of smuggler, adventurer and inveterate escaper Tom Johnson (or Johnstone), who deserves a post (or a biography) all of his own.

Notes:

10 January 1814 ↩Hampshire Chronicle, 28 February 1814 ↩Warwick and Warwickshire General Advertiser, 6 January 1827 ↩The Globe, 10. 13 April 1820. ↩The post Some early 19th-century prison escapes appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

January 12, 2017

The Neglected Daughter

The Neglected Daughter – An Affecting Tale (1804). Courtesy of Library of Congress

On 5 January, as temperatures dived, London Mayor Sadiq Khan opened emergency homeless shelters. That and the research I have recently completed on women who were abandoned by their lovers, cast out of their homes and ostracised by their families after falling pregnant put me in mind of this print from 1804.

THE NEGLECTED DAUGHTER — AN AFFECTING TALE

1

‘Twas on a winter’s evening & fast came down the snow,

And keenly o’er the wide heath the bitter wind did blow,

When a damsel all forlorn, quite bewilder’d in her way,

Press’d her baby to her bosom, & sadly thus did say.

2

Ah! cruel was my father that shut his door on me,

And cruel was my mother that such a sight could see,

Cruel is the winter’s blast, that chills my heart with cold,

But crueller than all the lad that left my love for gold.

3

The hush my dearest baby & warm thee in my breast,

Ah! little thinks thy father how sadly we’re distress’d,

For cruel as he isdid he know but how we fare

He’s shield us in his arms from this bitter piercing air.

4

Hush! hush! my dearest baby, thy little life is gone,

Ah! let my tears revive thee, so warm they trickle down,

The tears that gush so warmly, they freeze before they fall,

Ah! wretched wretched mother, thou’rt now bereft of all.

5

The down she sunk dispairing upon the drifted snow,

And wrung with cruel anguish lamented thus her woe,

She kiss’d her baby’s pale lips, & laid it by her side,

Then cast her eyes to heav’n, & bow’d her head, & died.

Publish’d July 2 1804 by LAURIE & WHITTLE, 53 Fleet Street, London

The post The Neglected Daughter appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

January 7, 2017

A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden

Sarah Murden and Joanne Major, authors of the much-praised All Things Georgian website, have once again used their formidable genealogical and investigative skills to conjure an amazing tale out of the archives. In fact their new book, A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History, gives double value since it relates two scandalous stories.

Sarah Murden and Joanne Major, authors of the much-praised All Things Georgian website, have once again used their formidable genealogical and investigative skills to conjure an amazing tale out of the archives. In fact their new book, A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History, gives double value since it relates two scandalous stories.

The first concerns the elopement in 1815 of Lady Anne Abdy, the married niece of the Duke of Wellington, and her lover the widowed Lord Charles Bentinck. A divorce and swift remarriage (the bride was already pregnant) ensued. The second scandal concerned a son of that marriage. Charley, an Oxford student, defied convention and married an illiterate Gypsy girl, the daughter of an Oxfordshire horse dealer. As the late Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother was a direct descendant of Charley, who went on to be ordained, that means that all the current Royal family are related to Charley too.

As in their first book, An Infamous Mistress, which detailed the life of Lord Charles Bentinck’s first mother-in-law Grace Dalrymple, the authors dig out some fantastic nuggets of interest. For example, Georgiana, Grace Dalrymple’s granddaughter and Charley’s half-sister, was known in the family as Hippo, probably a reference to her obesity. By following her progress we learn of her sad spinsterhood and chaotic finances. It’s a vivid picture of the life of a high-born misfit.

This really is a case of ‘You couldn’t make it up’. The plots may seem to come straight out of the world of Regency Romance but they are all true, and carefully annotated and verified by Major and Murden. With An Infamous Mistress, this family saga would make an excellent historical drama series.

A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History

by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden

Publisher: Pen & Sword

£15.99

ISBN: 9781473863422

Follow @sarahmurden and @joannemajor3 on Twitter

The post A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

Book review: A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden

Sarah Murden and Joanne Major, authors of the much-praised All Things Georgian website, have once again used their formidable genealogical and investigative skills to conjure an amazing tale out of the archives. In fact their new book, A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History, gives double value since it relates two scandalous stories.

Sarah Murden and Joanne Major, authors of the much-praised All Things Georgian website, have once again used their formidable genealogical and investigative skills to conjure an amazing tale out of the archives. In fact their new book, A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History, gives double value since it relates two scandalous stories.

The first concerns the elopement in 1815 of Lady Anne Abdy, the married niece of the Duke of Wellington, and her lover the widowed Lord Charles Bentinck. A divorce and swift remarriage (the bride was already pregnant) ensued. The second scandal concerned a son of that marriage. Charley, an Oxford student, defied convention and married an illiterate Gypsy girl, the daughter of an Oxfordshire horse dealer. As the late Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother was a direct descendant of Charley, who went on to be ordained, that means that all the current Royal family are related to Charley too.

As in their first book, An Infamous Mistress, which detailed the life of Lord Charles Bentinck’s first mother-in-law Grace Dalrymple, the authors dig out some fantastic nuggets of interest. For example, Georgiana, Grace Dalrymple’s granddaughter and Charley’s half-sister, was known in the family as Hippo, probably a reference to her obesity. By following her progress we learn of her sad spinsterhood and chaotic finances. It’s a vivid picture of the life of a high-born misfit.

This really is a case of ‘You couldn’t make it up’. The plots may seem to come straight out of the world of Regency Romance but they are all true, and carefully annotated and verified by Major and Murden. With An Infamous Mistress, this family saga would make an excellent historical drama series.

A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History

by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden

Publisher: Pen & Sword

£15.99

ISBN: 9781473863422

Follow @sarahmurden and @joannemajor3 on Twitter

The post Book review: A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages that Changed History by Joanne Major and Sarah Murden appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

December 19, 2016

Happy Christmas and New Year to everyone

2016 was certainly big year and I’m just talking about moi here, let alone The World.

For me, the high point was the publication in May of the book I had worked on for four years. The Disappearance of Maria Glenn tells the story of the abduction (or was it?) of a 16-year-old heiress from her uncle’s house, and what happens to her afterwards. It’s a rollercoaster story of triumph followed by disappointment and bitterness, and it features some fantastic characters, not least the shy but steely young woman at the heart of the story. Maria’s dogged uncle, a vacillating nursemaid and some bigwigs bent on stopping the truth from coming out.

And it’s all true.

The Disappearance Maria Glenn is available in hardback and ebook from Pen & Sword, Amazon UK, Amazon USA (and all the other Amazons) and all the major online retailers. I notice that the US Kindle version is only $12.22.

Aside from this dream-come-true, I have been pleased and honoured this year by the wonderful contributors to the site by fellow writers. There have been some fantastic guest posts from Geri Walton, Sarah Murden and Joanne Major and Anna M. Thane. Next year, I hope to do more like this.

Unfortunate Wretches

My next book, Unfortunate Wretches, about women executed between 1797 and 1837, will be out in 2017. As I have been unearthing some of the pitful stories of these women, I have posted tasters of my research. Here is a reminder of some of them.

Ann Mead: The life and death of a nursemaid (plus there’s more about Maria Glenn’s untrustworthy nursemaid here)

Ann Hurle: The execution of a young woman of education

A spate of arsenic deaths within a small area of North Norfolk.

Eliza Fenning (on AllThingsGeorgian)

Eliza Fenning (on AllThingsGeorgian)

It has not been all murder and death, however, and I’m pleased to say some lighter subjects crept in, including the scandalous triangle of Maria Foote and her two suitors (of varying degrees of ardour), a database of Georgian image databases and social climbing via boarding schools (for Geri Walton).

The post Happy Christmas and New Year to everyone appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

November 27, 2016

The scandalous love triangle of Maria Foote, William Berkeley and Joseph ���Pea Green��� Hayne

‘The Double Dealers, Two Strings to Your Bow, or, Who’s the Dupe’, a satire on the broken engagement between Maria Foote and Joseph Hayne. Published by S.W. Fores, 1825. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A tale of broken promises, scandal and lies. The whole sorry story points up the way women living outside respectability were passed, literally like chattels, from the ‘protection’ of one man to another. Even Maria’s own father appears to ‘pimped’ her out.

In about 1816, actress Maria Foote, then aged about 17 or 18, was invited to perform at Cheltenham Theatre. She had already played Juliet and Miranda as well as many other roles, at her father’s theatre in Plymouth and in Paris, but she was popular with audiences for her beauty rather than her talent.

Maria Foote, by Charles Picart, after George Clint, 1822. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

During the season, the manager of the theatre told her that she had attracted the interest of Colonel William Fitzhardinge Berkeley, the eldest son of the Earl of Berkeley, who wanted to take part in her ‘benefit’. 1 Before long, Berkeley and Foote had become lovers, with Berkeley promising marriage. There were obstacles to this: first and foremost, he was a notorious rake and liar; second, he was in the process of laying claim to his inheritance by trying to prove that his parents’ marriage was legitimate.

By this time, Maria was appearing regularly at the Covent Garden Theatre and living with her family at Keppel Street. According to the barrister John Singleton Copley in 1824: ‘The connection was no secret, but it was carried on with so much of decency and decorum, that Miss Foote never passed a night out of her father’s house in Keppel Street during the whole five years that she was under the protection of Colonel Berkeley, nor did the Colonel, in all that time, ever pass a night in that house.’ Despite this, they managed to find opportunities to conceive two children, the first born in 1821 and the second in 1823. On each occasion, Berkeley convinced Maria that she must conceal the births by retreating to the country for her confinement. If she failed to comply ‘he could never … make her his wife’. Within three months of each delivery, she returned to Covent Garden to resume her career. The children remained with wet-nurses and foster families.

After this, Maria decided that this situation could not continue and insisted that Berkeley should marry her, but he continued to fob her off and eventually, she had to accep that he was lying. Luckily, in early 1823, while pregnant with her second child, she made the acquaintance of a young man about town called Joseph Hayne, who had seen her on stage and been overcome with passion for her. 2

In order further his suit, Hayne invited Maria’s father Samuel Foote to his ancestral seat at Kitson Hall in Staffordshire, where Foote told him explicitly that for many years his daughter had been engaged to Colonel Berkeley, but if and when this relationship was finally broken off, he was in with a chance. Mr Foote did not mention that his daughter was pregnant with another of Berkeley’s children.

In early June Maria went to Barnard Castle in Durham, 250 miles from London, to give birth to the baby (her father told Hayne she had a ‘pulmonary complaint’ brought on by the smell of gas in theatres) and on her return, Hayne made a firm offer of marriage, Maria having finally given Berkeley the push. Berkeley, who had spies in the Foote household, took it upon himself to tell Hayne about the children, adding that Maria should now choose between the two men. When Hayne said he would break off his relationship with Maria, Berkeley leeringly said he would go immediately and ‘console’ Maria. Berkeley thought the whole thing highly amusing and was said to have given Hayne the nickname ‘Pea Green’.

Joseph ‘Pea Green’ Hayne. © Trustees of the British Museum

Maria wrote to Hayne telling him that she released him from his obligations towards her but wished to explain the situation to him in person; they met up in Marlborough. However, rather than ending it, they renewed their relationship. By now, Maria had the children living with her, but Berkeley was laying claim to them. Hayne was happy to let them go and they were subsequently handed over. Hayne again asked Maria to marry him. By 31 July, she had a firm proposal of marriage in writing.

Meanwhile, a marriage contract was drawn up, in which £40,000 would be settled on Maria, but now Hayne started prevaricating. His friends were not happy about his plans and on the morning of 6 September, the date set for the wedding, his solicitor arrived at Keppel Street with a message that ‘Mr Hayne would never see Miss Foote again.’ The next day, Hayne told Maria that to prevent the marriage someone had plied him with liquor and locked him in a room, from which he had only just managed to escape, and that the marriage would proceed the next day at 9am.

Everything was ready but Hayne never made his appearance. A servant was sent to Hayne at Long’s Hotel and, after a long delay, was informed that Hayne had ‘gone into the country’. After hearing nothing for six days, Maria wrote to her erstwhile fiancé and received a letter in reply in which Hayne claimed he was ‘divided’ between his friends and herself and had resolved to give up his friends. Later, he called on her in Keppel Street and they reconciled. They fixed another day for their marriage: 28 September.

This time, Mr Foote went with Hayne to Doctor’s Commons to obtain a marriage licence, which Hayne himself gave to Maria, saying that he would wait on her the next day. However, it was not Hayne who called but a Mr Manning, who had a message for Maria’s father – to the effect that the engagement was finally and irrevocably broken off. Again, Maria wrote to her suitor, and again Hayne replied that his love was unabated. He asked for another interview, which she agreed to as long as it was in the presence of her family, to which he replied that her last letter to him was couched in terms of ‘inveterate hatred’ and the marriage was off.

In this, Hayne (or more likely his friends) was anticipating a suit for breach of promise and he was trying to push the responsibility for ending the engagement onto Maria. He had letters published in newspapers asserting that he had not known of Maria’s previous liaison with Berkeley, nor of the children, even though he had renewed his offer of marriage after he was fully apprised of their existence.

Morning Post, 16 October 1824 © British Library

As is often the case, when love wanes, the bitterness turns on money. Maria Foote had called a halt to her professional career, sold her theatrical wardrobe and ordered a carriage. She had lost the chance of a financial settlement from the marriage. She decided to sue for breach of promise to marry, and her case was heard in the Court of King’s Bench in December 1824, where Hayne was represented by the silver-tongued James Scarlet, who made it clear that Maria was little different to a prostitute practised in the arts of seduction, referring to her ‘witchery’ and ‘fascinations’. The jury retired for 15 minutes and came back with a verdict in Maria’s favour and awarded her damages of £3,000, considerably less than her suit but still a sop to her hurt feelings.

Maria’s stage career resumed. When she returned to the Covent Garden Theatre in February 1825, her reception was rapturous. Someone placed a placard with ‘Miss Foote for ever’ on it in front of one of the boxes 3. She continued to tour until 1831 when, at the age of about 34 or 35, she married 51-year-old Charles Stanhope, 4th Earl of Harrington, otherwise known as Viscount Petersham, a man of fashion who loved to design his own clothes (he gave his name to the Petersham overcoat and the Harrington hat). They went on to have two children.

Lord Harrington Leaving Mother Matthew’s, by Thomas Rowlandson, undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

In 1827 Joseph Hayne, born in Jamaica, married Frances Jane Carter in Millbrook, Hampshire. Maria died in 1867, having outlived her husband by 16 years and the notorious William Fitzhardinge Berkeley by 10.

Notes:

A supplemental performance by an actor or actress, who kept all or part of the proceeds. ↩Hayne, from a wealthy plantation-owning family, was born in Jamaica in 1802 ↩Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 10 February 1825 ↩The post The scandalous love triangle of Maria Foote, William Berkeley and Joseph ‘Pea Green’ Hayne appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

November 22, 2016

Horace Cotton: The extraordinary Ordinary of Newgate

During the research for my forthcoming book Unfortunate Wretches one name kept coming up: The Reverend Horace (sometimes Horatio) Salusbury Cotton, the Ordinary (chaplain) of Newgate from 1814 to 1837. There are conflicting opinions of this man. Some described him as “humane”, others saw him as insensitive and slimy with a ghoulish enjoyment of his responsibility for giving convicted felons the news on whether they had been reprieved or would hang.

Horace Salusbury Cotton was born in about 1774, the son of Robert Salusbury Cotton and Frances Stapleton, of Reigate. At the age of 17 he matriculated at Wadham College, Oxford, and graduated four years later. By 1800 he was the vicar at Desborough in Northamptonshire 1 and by 1805 curate and schoolmaster at Cuckfield Grammar School in West Sussex. By the time he had moved to Hornsey in 1810 he was married to Caroline Amelia Merriman (1803) and had started a family. 2

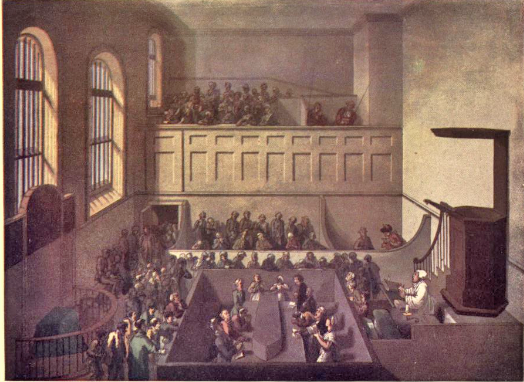

The Condemned Service at Newgate Chapel, by Thomas Rowlandson, from Microcosm of London; or, London in miniature

On 29 July 1814 the Court of Aldermen in the City of London appointed Cotton Ordinary (resident Chaplain) of Newgate Prison, replacing the Rev Dr Forde, who had shown such a disinclination to engage with the pastoral responsibilities of his job that he was forced to resign. This was a time of growing disquiet at the appalling suffering produced by the overcrowding, dirt, disease and destitution in Newgate and at the moral degeneration of the inmates. Perhaps the Aldermen felt that the religious fervour of Horace Cotton would improve things.

Within nine months of his appointment, Cotton was called to give detailed evidence about his duties as Ordinary of Newgate to the Committee on the King’s Bench, Fleet and Marshalsea Prisons. His answers to the MP Henry Grey Bennet reveal much about his job. He described his routine: visiting the sick, instructing prisoners in their moral duties and administering religious consolation. He gave two services every Sunday and organised a school for boys aged under 15. Tellingly, he felt the prisoners revered him: ‘I always treat them [the prisoners] as reasonable beings; I always take off my hat when I go into the ward, and while I treat them thus, they will treat me with respect.’ Bennet asked him if he kept a journal. ‘No,’ he said. This was a lie. Cotton kept a personal diary, quite apart from his official one, listing all the executed prisoners he encountered in Newgate, and against each name he wrote notes on their crime and their demeanours. Three sketches are included, probably done by a prisoner, each showing Cotton in action in the gaol. The notebook came to light in 2012 during a house sale. The BBC ran a feature on it (video). 3

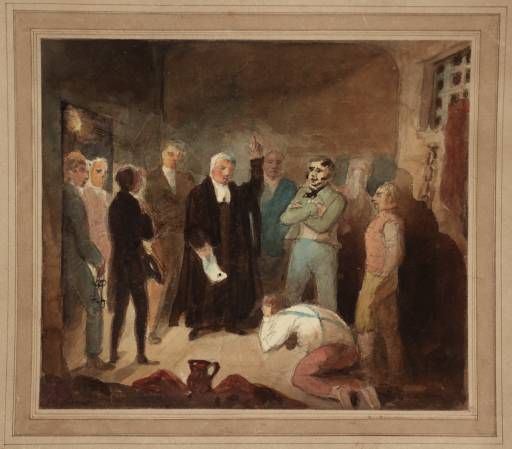

Condemned Criminals Receiving the Sacrament, by Newgate prisoner W. Thompson (c 1826). From the Convicts executed since the Year 1812 (inclusive) at Newgate. Manuscript record kept by the Rev. H. S. Cotton, Ordinary of Newgate. Via Peter Harrington

Cotton has been described as a ‘fire and brimstone’ preacher 4 and certainly his treatment of the condemned could not be described as in any way ‘nuanced’. He preferred a sledgehammer approach. In his Hangmen of England Horace Bleackley describes Cotton as a ‘robust, rosy, well-fed, unctuous individual, whose … condemned sermons were more terrific than any of his predecessors’. 5 Eliza Fenning, a young cook-maid condemned to death in 1815 for the attempted murder of her employer and his family was deeply distressed by Cotton’s address during the condemned sermon. A friend of her alleged victims, Cotton had chosen Romans 6: ‘What fruit had ye then in those things whereof ye are now ashamed? For the end of those things is death.’ He alluded directly to her, saying that she had been persuaded by Satan that revenge was sweet and that he would protect her, but had then abandoned her. Fenning was almost certainly innocent.

Cotton’s treatment in 1824 of the banker Henry Fauntleroy, who was convicted of a monumental financial deception, attracted more serious censure. He felt it appropriate to take his text from Corinthians: ‘Let him that thinketh that he standeth take heed lest he fall.’ Perhaps he did not see the irony of the text for a man about to endure the New Drop within hours. After Fauntleroy’s death, the Aldermen decided that the public were no longer to be admitted to the condemned service 6 and reminded Cotton that his job was to console convicted felons, not to harass or distress them in their remaining time on earth.

Dr Cotton, Ordinary of Newgate, Announcing the Death Warrant, by W. Thomson (c 1826). Courtesy tate.org.uk via London Street Views

Cotton took a callous, almost sadistic relish in his role with condemned prisoners. The prisoner artist W. Thomson’s portrayal of him announcing the Report (the death warrant) to a convicted felon, standing fully upright, his hand raised, conveys this. This coldness is also seen in the terse conclusions about executed prisoners he recorded in his secret execution diary. Of John Ashton, convicted of highway robbery in 1814, he wrote: ‘This man sprung up on the scaffold after he was turned off [dropped] and distinctly cried out “Am I not Lord Wellington”! He was pushed off again by the Executioner.’

There were rumours that Cotton was venal. The Freethinkers (atheists) who were imprisoned for blasphemy in Newgate were his implacable enemies and in the pages of their journal, The Newgate Monthly Magazine, alleged that Cotton intervened directly in justice. According to William Haley in a detailed account, a prisoner named Boniface managed to persuade Cotton to help his cause by telling him that he was due to come into the sum of £300 from his father but could not get access to it. ‘Out of pure Christian charity,’ wrote Haley, ‘our old parson provided him with counsel, who by some legal quirk, got rid of the capital part of the charge, and the worthy burglar was only found guilty of the minor charge.’ Haley, who had regular and close contact with Cotton, described him as ‘panting for gain’ and alleged that he conspired with the Recorder, Newman Knollys, ‘that infamous, tyrannical villain’, to bring about a sentence of 14 days. Boniface’s promises were empty and when he realised he would not be paid Cotton quite illegally arranged to have Boniface detained in Newgate beyond his sentence. 7

Most prisoners had no money to buy their way out, and Cotton does not appear to have profited particularly from his position. His living was comfortable, earning him £400 a year and free accommodation at a time when a male servant might make £16-20. 8 According The Morning Post, when he died in Reigate in 1846 at the age of 72, he left ‘few worldly goods’. 9

With thanks for pointers in Cotton’s story to Baldwin Hamey of London Street Views.

Notes:

Foster, J. (188-1892). Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886 and Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, 1500-1714. Oxford: Parker and Co. ↩The Clergy Database http://db.theclergydatabase.org.uk/ ↩Other personal diaries of Cotton’s were confiscated by the Aldermen, but this one seems to have escaped detection ↩Gatrell, V. A. C. (1994). The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770-1868. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩Bleackley, H. (1929). Hangmen of England. London: Chapman and Hall. ↩This was later rescinded. ↩Haley, W. (1825). Life in Newgate. The Newgate Monthly Magazines, or Calendar of Men, Things and Opinions. 1 (September 1824-August 1825). London: R. Carlile. I have not traced Boniface, but Haley’s accusations are so detailed and describe his conversations with Cotton about the case that it is difficult to disbelieve him. ↩Sussex Advertiser, 30 Mar 1835. ↩1 Sep 1848. ↩The post Horace Cotton: The extraordinary Ordinary of Newgate appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

November 11, 2016

Three women hanged for poisoning their husbands in 1836: Betty Rowland

The second in a series looking at the three women hanged in England in 1836.

Read about Harriet Tarver, executed on the same day as Betty Rowland, at Gloucester.

BETTY ROWLAND

Hanged at Liverpool on 9 April 1836, for the poisoning murder of her husband William. Aged 46.

Dr. Syntax Attends the Execution, by Thomas Rowlandson (1820). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

William Rowland, a 50-year-old weaver, who lived with his wife Betty in a cellar in Butler Street, Oldham Road, Manchester was taken ill on 18 December 1835 and died the next day. No doctor attended him. Betty Rowland set about arranging his funeral, which was to take place on 22 December, with a burial at Mr Schofield’s Chapel Yard in Every Street.

In the meantime, Jeremiah Cawley, a neighbour who suspected foul play, had a word in the ear of the local beadle, James Sawley, who made it his business to look in at the cellar on the afternoon of the funeral. There he encountered a lot of drunk guests who did not appreciate his efforts to halt the funeral in order to allow the coroner to view William’s corpse. Betty was indignant and insisted that her husband would be buried. Sawley attempted to arrest her, at which a ‘tall, stout man’ jumped up, and it was only by promising the company that he merely wanted to ask her a few questions that they let him take her.

Samuel Bowstead, Parish Beadle by an unknown artist (1846). © Fulham Palace Art Collection

As they walked to Shudehill lockups Betty said:

‘Oh dear. I never gave him anything but a drop of brandy, and that I borrowed money to pay for. I am as innocent as a child, whether I suffer for it or not.’

And later she said:

‘Oh yes, I gave him three pennyworth of whiskey on Tuesday afternoon.’

The coroner and the deputy constable were informed but as there was no evidence against Betty, she was released. William was buried, but within days he was dug up again because Sawley had made more inquiries. Betty decided to leave the neighbourhood. William’s stomach was sent for analysis by Mr Ollier, a surgeon, whose tests for arsenic were positive.

At a coroner’s inquest on 30 December Ann Eaton, a neighbouring cellar dweller, told the court that she found William’s body upright in a chair and helped Betty lay it out. Betty had produced a jug from a cupboard and said he’d had a gill of beer and a pennyworth of rum from it before he died. Ann said the Rowlands quarrelled frequently. Another neighbour, Francis Rochford, said that the deceased was very low spirited and that the Rowlands seem to have recently separated but had been reconciled.

At this stage there was no evidence that Betty had poisoned her husband, only that he had been poisoned by someone. The inquest was adjourned while a search was made for Betty. During this interval, it became known that Betty had bought arsenic from Mr Goodman, a chemist in Oldham Road. Soon after, she was apprehended in Mark Lane by William Booth, the beadle of Chorlton-upon-Medlock, who accused her of poisoning her husband. She denied it and then began to cry, saying, ‘I am guilty, and I don’t care how soon I die.’ She told Booth that she had taken her cousin Alice Tinker to buy a pennyworth of arsenic, saying it was to poison rats. The poisoning had been an accident: ‘I put it into his gruel and thought it was sugar,’ she said. She had failed to call a doctor because she did not think William would die.

Jeremiah Cawley told the magistrate’s court that he had called at the house after William died, and there accused Betty, who was drunk, of murder. He clearly knew a lot about her. ‘How have you disposed of this man?’ he said. She did not reply and he added, ‘You have disposed of him as you did of your other husbands [she had been married twice before]. You have poisoned him, and it is the common report of the neighbourhood.’ He took his suspicions to the police.

Betty claimed throughout that the poisoning was accidental. In the gloom of the cellar she had mistaken the arsenic for sugar and mixed it in the gruel. When she realised what she had done, she threw the remainder into the fire. She also claimed that her husband was violent from the beginning of their three-year marriage.

Betty was committed to Kirkdale for trial at the next assizes. Newspaper reports described her as ‘a woman of low stature and very forbidding appearance’.

County House of Correction, Kirkdale (Liverpool) engraved by W. Watkins after a picture by C.Pyne, published in Lancashire Illustrated, 1831. Image courtesy of Ancestry Images.

She was found guilty at the trial on 30 March and sentenced to death. Her execution, in front of the House of Correction at Kirkdale, was a riotous scene. To get a good view spectators started arriving from five in the morning, although the event was not due to go ahead until three in the afternoon. They became bored and started pelting each other with missiles. Police attended but after they left gangs of thieves started stealing tippets, bonnets and shawls from the women, who were forced to take refuge in the gaol and to escape through the court house.

At two thirty the under sheriff arrive, delivered the warrant and Betty,’the unhappy culprit’, was led out to the press room, attended by the chaplain, the Reverend Mr Horner. Wearing a “Lancashire bedgown, a linsey-wolsey petticoat and a frilled cap”, and with her arms were pinioned and her clothes wrapped around her, she emerged from the building. She stood without assistance on the platform and after a portion of the burial service was read, the signal was given, the bolt was withdrawn, and she dropped. 1

Notes:

Manchester Courier, 5 Dec 1835, 9 Jan 1836; Kendal Mercury, 16 Apr 1836. ↩The post Three women hanged for poisoning their husbands in 1836: Betty Rowland appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

October 22, 2016

36 cases of fraud committed by women, tried at the Old Bailey 1797 to 1837

During my research on some capital fraud cases for my next book, Unfortunate Wretches: Women and the Gallows 1797-1837 I ran a search on the Old Bailey online database on all trials of women in that 40-year period.

The results showed that charges of fraud against women were fairly patchy. Years went by with apparently no women being charged with fraud; for instance, there were none between 1819 and 1826, although we can be sure the women of London continued to carry out these petty crimes. Only a few were felony charges.

In this instance, I queried only fraud. Other similar crimes are categorised under forgery and still others under perjury and coining, which makes it all quite confusing. Still, a summary of what I found for ‘fraud’ provides a useful snapshot of some of the methods women used to get by, from passing bad sixpences in a public house, to falsely begging for clothes from the parish officers, to ordering goods on the account of a non-existent or former employer. Fraud on this scale was a misdemeanour. It only became a felony when the value of goods exceeded 40 shillings (£2).

In 1836 all forgery and counterfeiting felonies were no longer punished with death.

Accused of trying to cheat Philip Sewel out of butter, cheese, and eggs. NOT GUILTY.

Leadenhall Market by T. H. Shepherd. Copyright London Metropolitan Archives, City of London

Accused of uttering false money (2 sixpences) while buying 3 shillings worth of mackerel in Billingsgate market. GUILTY: Six months in Newgate and sureties for good behaviour.

Mary Welchford, 10 January 1798

Accused of obtaining three guineas (£3.15) under false pretences. Went into a public house and asked to borrow £5 on behalf of a customer known to the publican. She spent the money on clothes and drink. GUILTY: Privately whipped.

Elizabeth Finch, 4 December 1799

Accused of obtaining muslin and handkerchiefs to the value of 14 shillings. No evidence. ACQUITTED.

Mary-Ann Goodman, 9 January 1805

A baker alleged that Goodman falsely claimed to have come on behalf of a customer and asked for bread and flour. GUILTY: One week in Newgate.

Elizabeth Forster, 10 July 1805

Accused of obtaining under false pretences a coat, waistcoat, breeches, worth 9 shillings. No evidence. ACQUITTED.

Esther-Jane Jenner, 30 October 1805

Accused of falsely obtaining a cruet stand of the value of £1 2 shillings (£1.10) from a glass and china seller, by saying that she was sent by a regular customer. Previously worked as a servant for the customer. GUILTY: One month in Newgate and fined 1 shilling. Aged 19.

Accused of obtaining a tin box and two 7 shilling pieces, valued at 7 shillings and 1 penny, the property of Thomas Male, who was killed when a house collapsed in Skinner Street, Bishopsgate. GUILTY: Transported for 7 years. Aged 34.

Mary Pilkington, 29 October 1806 (felony charge)

Accused of attempting to obtain letters of administration of John Jacob Dyson, deceased, in order to obtain prize money due to him for serving on the Eurus. Error in the indictment (wrong name). NOT GUILTY.

Indicted for making and uttering a counterfeit seven shilling piece. GUILTY: Six months in Newgate and sureties for good behaviour. Aged 48.

Charlotte Wade (alias Bumstead), 6 April 1808 (felony charge)

Obtaining 75 silk handkerchiefs, 6 pairs of silk stockings, 109 yards of lace (total value over £35) from a warehouse in Newgate Street, by claiming to have been sent by a regular customer (she had previously been her servant). She subsequently pawned the goods. GUILTY: Transported for seven years. Aged 23.

Henry Walton, Plucking the Turkey. Courtesy of The Tate

Margeret Laidler, 13 January 1813

Accused of pretending to be sent by her master to collect a turkey from a poulterer in Leadenhall Market. ACQUITTED.

Mary Parkins, 17 February 1813 (felony charge)

Fraudulently acquired 12 yards of bombazeen valued at £2 13 shillings (£2.65). She came into a haberdashers with a counterfeit note. GUILTY: Transported for seven years. Aged 35.

Amelia Jarvis, 21 June 1815 (felony charge)

Feloniously uttering a forged will with intent to defraud the widow and sister of James Campbell. ACQUITTED (signature not proved).

Elizabeth Hazelton, 10 January 1816 (felony charge)

Possessing 3 counterfeit notes of the Bank of England. Elizabeth was arrested in Bethnal Green as she left her lodgings in Wards Row, by John Foy, a police officer from Marlborough Street. Once in custody she was discovered to have numerous banknotes, both good and bad, secreted in her clothes. There were more in her room. The charge was possession rather than uttering, a capital crime. GUILTY: Transported for 14 years. Aged 34.

Mary Ann walked into a shoemakers shop, was fitted for walking shoes, claimed that she was about to be married to a nephew of Sir John Thomas of Bath and that her fiancé would pay for them, and marched out with a pair worth 14 shillings. NOT GUILTY.

Accused of pretending to the parish officers of St Giles, Cripplegate to be the widow of Thomas Footman, with two children and another on the way to support. They relieved her with 21 shillings (£1.05). She had been receiving money from the parish of St Sepulchre since 1809. Her defence was that she ‘was in distress’ and had five children. GUILTY: Fined 1 shilling. Aged 30.

Charlotte Lewis, 21 April 1819

Charlotte used a fraudulent letter to obtain 2 petticoats, a pair of shoes and stockings and a shawl and 20 shillings to convince the clerk of St Margaret’s in Fisher Street that she was leaving the workhouse and moving to her uncle’s place in Manchester. Her defence was that she needed the clothes in order to ‘do better’. GUILTY: Confined 3 months. Aged 23.

Mary walked into the wine vaults in Fore Street and asked for a bottle of gin for her employer. She had previously left his employment. Her employer told the court that he believed her husband had ‘misled her’. GUILTY: Confined 1 month. Aged 24.

No details. NOT GUILTY.

Bridget ran a scam on Mary Edmonds, an unemployed servant. She pretended to find a purse containing a ring in Bishopsgate Street and told Mary, who was passing at the time, it was gold and that she could buy it from her for 6 shillings. It turned out to be worthless. GUILTY: Transported 7 years. Aged 30.

Mary Ann Pendrill, 11 May 1835 (felony charge)

Pleaded guilty to obtaining goods worth over £22 under false pretences. GUILTY. Aged 20. Judgment respited. Various petitions were submitted on her behalf. Convict records show that Mary Ann was transported on 14 December 1835.

Margaret Taylor, 1 February 1836

On two separate occasions, Margaret paid for alcohol at the Globe Tavern, Moorgate with bad sixpences. GUILTY: Confined 1 month. Recommended to mercy by the jury. Aged 29.

A policeman, acting on information, arrested Eliza in Dean Street, near St Margaret’s Church in Westminster. She quickly threw the 2 counterfeit shilling pieces and 2 sixpences in her hand into an ‘area’ (the basement well in front of a house) and told him that she had been given them by a young man on the south side of the Thames. GUILTY: Confined 6 months. Aged 18.

Ann Smith (aka Betsy Waters), 1 February 1836

Ann Smith passed a bad shilling to a tobacconist and an apothecary in Lambeth. GUILTY: Confined 12 months. Aged 18.

Ellen pretended to be in the service of Mr Clements when she went into a baker and asked for two loaves. She had just been dismissed by her master. GUILTY (punishment not given). Aged 15.

Charged with trying to pass off a counterfeit sixpence while buying coal and wood in Richmond Street, St James’s. She was later arrested by the shopkeeper’s wife, who recognised her and took her to the police station. Another counterfeit coin was later found in her mouth. GUILTY: Confined 1 year. Aged 49.

Catherine tried to run away when challenged by Ann Crabtree, the wife of a baker, after she gave him bad shillings at least twice in a row while buying bread. GUILTY: Judgment respited. Aged 36.

Margaret Callaghan, 24 October 1836

Margaret Callaghan, a servant to Elizabeth Mortimer, a laundress, asked to borrow money from a customer, widow Elizabeth Scare, saying it was on behalf of her mistress, who was ‘in want’. In court her defence consisted of slander; she claimed that Mrs Mortimer ‘had another woman’s husband in the house’. GUILTY: Confined six months, three of them in solitary. Aged 19.

Ann twice paid for sugar and a candle in the shop of Anselmo Chiarizia in Johnson Street, Somers Town, with bad shillings. GUILTY: Confined 6 months. Aged 21.

Buying a candle. Published 1805, London. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection

Charged with paying for gin with a bad shilling. GUILTY: Confined 1 year. Aged 55.

Catherine Taylor, 27 February 1837

Catherine tried to pay for three mutton chops with a bad half-crown. After she was arrested she tried to discard another half-crown but was caught. She struggled during the arrest and assaulted the police constable. GUILTY: Confined 1 year. Aged 24.

Note: William Hibner, a butcher’s assistant, gave evidence. He may be the son of Esther Hibner, hanged for murder in 1829.

Margaret Carroll, 27 February 1837

Charged with passing off a bad sixpence to buy a candle. GUILTY: Confined 6 months. Aged 14.

Multiple witnesses from pubs gave evidence that Ann Dukes had given them counterfeit coins in exchange for beer. GUILTY: Confined 1 year. Aged 25.

Mary Lyons and Catherine Murphy, 14 August 1837 (felony charge)

Charged with John Scannell with uttering a forged £10 with intent to defraud John Jupp, a silversmith and salesman, in Borough High Street. Jupp claimed that Lyons and Scannell came to his shop with a young boy to buy a suit of clothes worth 19 shillings, eliciting his sympathy by telling him the child was motherless. They offered an old £10 and he was suspicious of it but eventually agreed to take it. Murphy immediately pawned the suit. A Bank of England inspector said that an illiterate person might mistake the note for a good one; the jury may have accepted that the accused did not realise it was bad. NOT GUILTY.

Perry, a servant, borrowed £3 from Clara Denton, a pub landlady, claiming to act on behalf of her employer. GUILTY: Confined 4 days (recommended to mercy by the jury and the prosecutor). Aged 20.

The post 36 cases of fraud committed by women, tried at the Old Bailey 1797 to 1837 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

October 20, 2016

Elopement in high life: Anne Wellesley and Lord Charles Bentinck

Sarah Murden and Joanne Major’s site All Things Georgian is a mine of wonderful 18th- and early 19th-century information. The duo have already published An Infamous Mistress, an acclaimed biography of Grace Dalrymple, which is stuffed not only with original research but also with hitherto little-known tales of Georgian era love, politics and adventure.

We now eagerly anticipate the publication of their next book, A Right Royal Scandal (keep reading for details), which you can pre-order from Pen & Sword.

Here they give us a taster on the scandalous elopement of Anne Wellesley and Lord Charles Bentinck in 1815.

On the 5th September 1815, just weeks after the Battle of Waterloo, the married niece of the Duke of Wellington stepped into her lover’s gig, which was waiting for her near Hyde Park, and drove away into a new life. It was a fateful decision which was, over the ensuing years, to have consequences on families as diverse as British royalty and Romany gypsy.

Lady Abdy as a Bacchante by Mrs Joseph Mee, 1813, painted for George IV when Prince Regent. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

Anne Wellesley, beautiful, spoilt, impulsive and quick-tempered, was the eldest daughter of the 1st Marquess Wellesley, Richard Colley Wellesley, and his Parisian wife who had reputedly enjoyed a former career as an opera dancer. Like her brothers and sister, Anne had been born illegitimately as her mother, Hyacinthe Gabrielle Rolland, had been for many years Richard’s mistress until, after she had borne him five children, he made her his wife. A tenure in India as Governor General caused a rupture in the marriage between the Marquess and Marchioness Wellesley and they separated in 1810, the marquess going on to cohabit with various mistresses in his ‘seraglio’ at Ramsgate.

Blessed with good looks, aristocratic connections and a small fortune, if not legitimacy of birth, Anne made what was considered a good marriage to Sir William Abdy, Baronet, often described as the ‘richest commoner in England’. 1 But Sir William was dull, and possibly impotent, and a fine house, grand carriage and the latest fashions did not prove enough of a distraction for his bored young wife.

Lord Charles Bentinck was brother to the Duke of Portland; he had been an officer in the army but, when he met Anne, was a widowed gentleman with little more than a talent for gracing a dance floor and the good favour of the Prince Regent. Charles’s first wife was Georgiana Seymour, daughter of the notorious 18th-century courtesan Grace Dalrymple Elliott and, so it was claimed, the prince himself. Georgiana died tragically young, leaving her bereft husband with a young daughter to care for. The prince, Charles’s putative father-in-law, was also his friend and found employment in his household.

Portrait of Lady Charles Bentinck (née Wellesley) by Sir Thomas Lawrence c.1825. Philip Mould Historical Portraits.

Lady Abdy resembled the late Lady Charles Bentinck and it was probably this similarity in appearance that drew the widowed man, like a moth to the flame, into her orbit. He was permitted to visit the Abdy’s house and Lady Abdy fussed over Lord Charles’s daughter. In the words of Anne’s own sister, ‘no lady would have suspected [Lord Charles] of being in the least dangerous.’ Certainly, Sir William Abdy did not realise the danger until it was too late.

Crooms Hill overlooking Hyde Vale, Blackheath by Thomas Christopher Hofland. English Heritage, Rangers House.

On that fateful September day, the amorous couple sped off across London in their gig, heading for Greenwich where Lord Charles had taken lodgings on Crooms Hill. Hoping to avoid detection, he passed as Captain Charles Brown and Anne pretended to be his wife but it wasn’t long before the newspapers picked up on the gossip.

ELOPEMENT IN HIGH LIFE! – A young married Lady of rank, and highly distinguished in the fashionable circles by her personal attractions, is said to have absconded from the neighbourhood of Berkeley-square a few days since, in order to throw herself into the arms of the brother of an English Duke. 2

The affair, somewhat predictably, ended in the courts with a Criminal Conversation case brought by Sir William and a divorce was ultimately granted after the Wellesley family pulled rank and called in favours. Anne became the second Lady Charles Bentinck just in time as she was, by that stage, expecting her first child by Lord Charles.

You can find out more about the elopement and the drama caused by an equally scandalous union made by Charles and Anne’s eldest son in A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages That Changed History.

Almost two books in one, A Right Royal Scandal recounts the fascinating history of the irregular love matches contracted by two successive generations of the Cavendish-Bentinck family, ancestors of the British Royal Family. The first part of this intriguing book looks at the scandal that erupted in Regency London, just months after the Battle of Waterloo, when the widowed Lord Charles Bentinck eloped with the Duke of Wellington’s married niece. A messy divorce and a swift marriage followed, complicated by an unseemly tug-of-war over Lord Charles’s infant daughter from his first union. Over two decades later and while at Oxford University, Lord Charles’s eldest son, known to his family as Charley, fell in love with a beautiful gypsy girl, and secretly married her. He kept this union hidden from his family, in particular his uncle, William Henry Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, 4th Duke of Portland, upon whose patronage he relied. When his alliance was discovered, Charley was cast adrift by his family, with devastating consequences.

Almost two books in one, A Right Royal Scandal recounts the fascinating history of the irregular love matches contracted by two successive generations of the Cavendish-Bentinck family, ancestors of the British Royal Family. The first part of this intriguing book looks at the scandal that erupted in Regency London, just months after the Battle of Waterloo, when the widowed Lord Charles Bentinck eloped with the Duke of Wellington’s married niece. A messy divorce and a swift marriage followed, complicated by an unseemly tug-of-war over Lord Charles’s infant daughter from his first union. Over two decades later and while at Oxford University, Lord Charles’s eldest son, known to his family as Charley, fell in love with a beautiful gypsy girl, and secretly married her. He kept this union hidden from his family, in particular his uncle, William Henry Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, 4th Duke of Portland, upon whose patronage he relied. When his alliance was discovered, Charley was cast adrift by his family, with devastating consequences.

A love story as well as a brilliantly researched historical biography, this is a continuation of Joanne and Sarah’s first biography, An Infamous Mistress, about the 18th-century courtesan Grace Dalrymple Elliott, whose daughter was the first wife of Lord Charles Bentinck. The book ends by showing how, if not for a young gypsy and her tragic life, the British monarchy would look very different today.

Notes:

Sir William Abdy’s baronetcy was a hereditary title of honour reserved for commoners and not in the peerage, hence he was a ‘commoner’ even though he held a title. ↩Morning Chronicle, 13 September 1815 ↩The post Elopement in high life: Anne Wellesley and Lord Charles Bentinck appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

The Norfolk Poisonings

The Norfolk Poisonings