Naomi Clifford's Blog, page 6

May 30, 2018

The Murder of Mary Ashford: did footmarks point to her killer?

The men who pulled 20-year-old Mary Ashford out of a stagnant pond in Erdington near Birmingham early on 27 May 1817 were in no doubt. Blood and bruises on her body told them that foul play was involved in this young woman’s death. But there were other clues too – a series of footprints, clearly made by two people, in the newly turned earth in the next-door field, impressions in the dewey grass near a tree, a single imprint of a shoe at the top of the pond, and some of Mary’s belongings arranged neatly nearby.

Mary Ashford, from Cooper, J. (1818). A Report of the Proceedings Against Abraham Thornton at Warwick Summer Assizes, 1817, for the Murder of Mary Ashford; and, subsequently, In the Court of King’s Bench, in an Appeal of the Said Murder. Warwick: Heathcote and Foden.

A passing workman had raised the alarm after he found the belongings by the pond and rushed to the nearby wire-drawing factory. Among the men who ran down to the field were William Lavell and Joseph Bird, about whom we know little except that they were able to read and write and were skilled at their jobs. William Lavell was personally acquainted with Mary – he had danced with her the previous evening at a Whitsuntide party at a coaching inn – and it is likely Bird was too. This was a close-knit community, a few hundred souls living in a village outside Birmingham, and the families all knew each other.

Mary’s body was found in a stagnant pond early on the morning after she left a party in the company of Abraham Thornton, from Cooper, J. (1818).

Together Lavell and Bird took the initiative to look more closely at the footmarks in the neighbouring field. They were not trained investigators nor acting in any official capacity – and naturally they made what we would view as fundamental mistakes. They contaminated the evidence by making their own footprints in the field and failed to stop the many people, including members of Mary’s own family, who had joined them from the factory or rushed from Erdington village doing the same. And although they tried to protect the evidence from the rain by covering a section of the footprints with boards, no one, including their employer, Joseph Webster, and the magistrate William Bedford, who were both soon on the scene, thought to organise a sketch of the prints or to remove some of them en bloc for preservation.

What Lavell and Bird did manage to do was to work out a plausible narrative of events, and it was this: Mary had been waylaid in the field and had tried hard to dodge her attacker, running mostly around the edge of the field but, after being cornered, she was overcome and, judging from the person-shaped impressions in the grass, raped on the ground near the pond. The single footmark by the pond was made when the killer braced his foot against the steep incline of the pond to throw Mary’s body in. A line of his footmarks diagonally across the field towards a gate and on to private land showed the route he took to run from the scene.

Twenty-five-year-old Abraham Thornton was a thickset bricklayer working for his father. The family lived at Shard End, Castle Bromwich. This sketch is based on one done in court. From Cooper, J. (1818).

The unusual depth of the footmarks in the field led Lavell and Bird to believe that Mary’s killer was a heavily-built man. And so it seemed to transpire. Within hours, Abraham Thornton, a burly bricklayer from Castle Bromwich, was identified as the prime suspect. He had left a dance with Mary, her best friend Hannah Cox and her fiancé Benjamin Carter the previous evening, and after the others peeled off to their own homes, he and Mary were left alone together.

Not long before Mary was killed, there had been another murder in Warwickshire, less than 12 miles away, and the case bore astonishing similarities to Mary’s. The prosecution had relied on impressions made in mud and a woman retrieved from a pond, and possibly Lavell and Bird had these factors in mind when they saw the footmarks in the ploughed field. On the evening of 10 October 1815, Ann Smith, a servant at Over Whitacre, went missing. She was about to start a new job and had asked Isaac Brindley, a fellow servant, to carry her box to a friend’s house for safekeeping. She meanwhile would be taking a jug of barm (used in breadmaking) to a neighbour. She never arrived. The following morning a shoe was spotted near a water-filled pit in a field. The chaff and wheat nearby had been trodden down and the barm spilt into the ground. Ann’s body, bearing bruises and abrasions, was fished out of the pit. The identity of her killer was revealed in the impressions found in the mud: a patch set sideways on the knee of a man’s corduroy breeches and the heel of a shoe. Brindley was brought to the scene and made to kneel into the mud. At his trial at Warwick in April 1816 a local tailor gave his expert opinion that his breeches were an exact match. Brindley, who had no alibi, was convicted at Warwick and hanged.

Thornton’s fate, however, was very different and led to a series of events few could have predicted…

My book The Murder of Mary Ashford is now available. Published by Pen & Sword.

The post The Murder of Mary Ashford: did footmarks point to her killer? appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

May 29, 2018

Clocking on: Did ‘time’ help Abraham Thornton escape justice?

Warwick Assize court. August 1817. Abraham Thornton is on trial for his life, accused of the murder of Mary Ashford, whose body has been found in a stagnant pond just outside the village of Erdington, near Birmingham. Thornton’s defence is that he was not with her when she died – he was miles away, walking home after parting with Mary during the early hours. Several eyewitnesses have come forward to back up his story.

Abraham Thornton at the bar, from Cooper, J. (1818). A Report of the Proceedings Against Abraham Thornton… Warwick: Heathcote and Foden.

Thornton’s barrister asks a Birmingham man, who was milking cows on a farm on Thornton’s route home to Castle Bromwich, to confirm exactly when he saw the accused. The witness replies that it was ‘about half past four o’clock, as near as I could judge, having no watch.’

Q: How did you know what time it was?

A: My wife, who was with me, afterwards asked at Mr Holden, of Jane Heaton, the servant, what o’clock it was. She looked at the clock and told her.

Q: How long was it, after you saw the Prisoner, before your wife asked Jane Heaton what time it was?

A: Before she inquired, and after I saw the Prisoner, we had milked a cow a piece, in the yard, which might occupy us about ten minutes. The cows were not in the yard then, they were a field’s breadth from the house.

Q: And you think this time, in all, took up about ten minutes.

Clearly, estimating time from the number of cows you had milked is not an accurate way to tell the time and such testimony today would be almost worthless.

So how did people agree on exactly what the time was two hundred years ago? Before the Industrial Revolution, the position of the sun through the sky was enough to indicate sunrise, sunset and mid-day. If you lived within hearing of a church, the bells would signal services or key points in the day. The only people who really needed a more accurate idea of hourly time – the clergy, for instance – used measuring devices such as sand timers, burning candles or sundials (the latter only effective in sunshine of course). By the late 18th century, clocks and watches were proliferating, mostly amongst monied people, but even modest households might own a timepiece of one kind or another.

Essentially, however, people understood that there were three types of time: true time, calculated from a longitudinal position and the sun; conventional time, which might be signalled by a church clock or by a timepiece belonging to a trusted person; all the rest was estimated time.

Although there was no parish church in Erdington, meaning that witnesses in the Mary Ashford murder case had no way of knowing the conventional public time, some people did own clocks – but the accuracy of these depended on how the owner kept them. The victim’s best friend’s mother kept hers permanently about forty minutes fast in order to fool the household into getting up in plenty of time for work.

It was clear from the start that timings would play an important part in the case. One witness, a gentleman, told the court he habitually kept his pocket watch by ‘Birmingham time’, and that within hours of the discovery of Mary Ashford’s body had gone into the city to check that it was accurate.

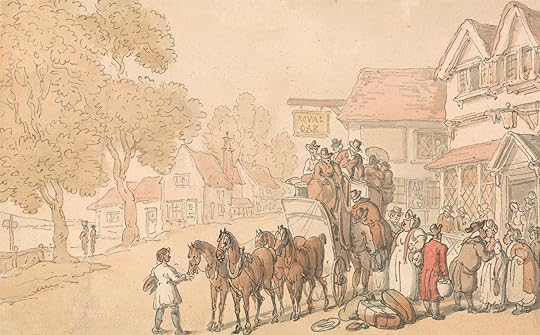

Thomas Rowlandson, Loading a Stage-Coach (The Royal Oak, Islington), undated. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

How did the transport system function if people across the country used different times? Stagecoaches advertised departure and arrival times and so needed a degree of standardisation. Guards carried timepieces that were adjusted to compensate for the local time differences arising from longitudinal position. They gained about 15 minutes in every 24 hours, when travelling west to east, and the reverse when coming back the other way.

‘A steam train on a line at a station with passengers travelling. Coloured aquatint by Havell after Calvert.’ Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

As the country became increasingly industrialised and workers found better wages in factories than on the land, keeping to specific and agreed times of arrival and departure became more important. ‘Clocking on’ became an accepted feature of working life.

However, it was the advent of the railways in the 1840s, along with the telegraph companies and the Post Office, that had the greatest impact on the standardisation of time. In 1840, the Great Western Railway was the first train company to order that London time be used in all its timetables and at all its stations. Over the next few years all the other companies followed suit but it took until 1880 for Greenwich Mean Time to be officially adopted as the standard throughout Great Britain.

The clock on the Corn Exchange has two minute hands: the black one shows ‘Bristol time’ while the red shows GMT. cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Rick Crowley

If the witnesses in the Mary Ashford murder case had kept accurate pocket watches all telling the same time, who knows, perhaps the outcome of the trial would have been different. As it was, after the trial, Thornton remained the prime suspect, and Mary’s family and their supporters were determined that he would not get away with his crime.

The post Clocking on: Did ‘time’ help Abraham Thornton escape justice? appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

May 8, 2018

Where was Mary Ashford’s spot at Birmingham market?

On 26 May 1817, Mary Ashford, a 20-year-old native of Erdington, walked in to Birmingham from her uncle’s farm at Langley Heath, stopping off at her best friend Hannah Cox’s house to leave clothes she would later change into to go to a Whitsuntide party at Tyburn House. She made this journey to the market in High Street, Birmingham twice a week and habitually stood near the Castle Inn to sell her eggs and butter.

Mary Ashford, from ‘A Report of the Proceedings Against Abraham Thornton at Warwick Summer Assizes, 1817, for the Murder of Mary Ashford; and, subsequently, In the Court of King’s Bench, in an Appeal of the Said Murder’. Warwick: Heathcote and Foden.

Mary was considerably older than the young girl shown in Henry Walton’s The Market Girl (first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1777), who looks to be only about ten or eleven. She was probably posed by Walton’s niece and that may account for a certain lack of authenticity about her. The scene is very peaceful and the town in the distance rather sleepy, quite unlike the bustling metropolis of Birmingham. Still, it emphasises that people often walked long distances in order to sell their produce at market.

Henry Walton, 1746–1813, A Market Girl. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

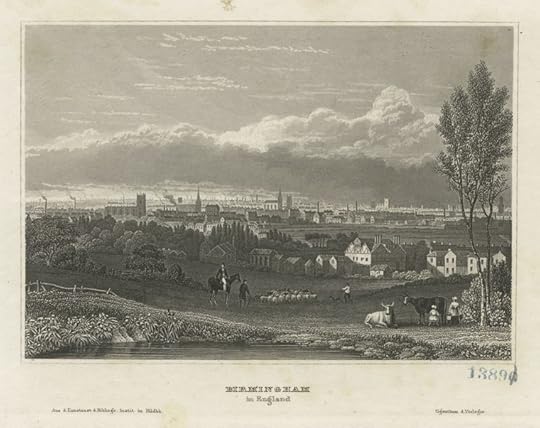

In contrast, Mary Ashford’s journey of six or seven miles was along a busy route towards a rapidly industrialising city, and she would have seen and greeted many working people along the way. After crossing Salford bridge over the Birmingham canal, passing a water mill on her right, and skirting the grounds of Aston Hall with its adjacent church, where she and her siblings were christened, she entered the city through Aston Street. 1

“Birmingham in England.” The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. By my reckoning St James’s is the second church from the left – but if you know better please correct me.

She would also have had to carry, very carefully, the eggs and butter the whole way, probably in a basket. She was a strong but slightly-built girl and it probably did not make it easier that she had a ‘natural condition upon her’ (this was a crucial issue in the terrible events that were to follow and how they were interpreted – but you will have to read the book to find out more about this).

What greeted her at Birmingham? Markets were known as rough, busy places, not for the faint-hearted. Mary Ashford, quite as much as her female customers, would have been well able to cope both with the press of crowds and over-familiar banter from her fellow hawkers, and at times she probably would have had to fend off outright sexual assault.

The Pretty Pedlar, portrayed by Thomas Rowlandson, fights off an assault on the way to market. Date unknown. Like Mary, she carries eggs to market.

In 1820 the Birmingham Journal carried this description of the market in Birmingham:

The most unpeopled streets of a former period were now busy with life and bustling activity. From morning to night continually swept along them a busy tide, and trains of heavy carts extending for more than a mile, loaded with coal and lime, and bars of iron from the district around, stretched from one street to another and far beyond them.

On market days there was great business and bustle. Crowds of country people gazing in at windows blocked up the narrow footway at the risk of being overturned or of danger to their limbs from handcarts and wheelbarrows rolling inside the kerbstone. Ballad singers and blind beggars swarmed at every corner. Here a brawl, the sequence of the sloppings from a trundled mop in the face of a passer-by. There a crowd round some baker’s horse with bread panniers occupying the breadth of the pathway and those within playing at pitch-loaf, to the danger of some unwary inhabitant. Heaps of coals lying upon the pavement from morning to night and mud heaps all around.

Not much of the noise and bustle of Birmingham market is conveyed in this 1827 engraving based on a watercolour by David Cox (1783–1859), but it does show the position of Nelson’s statue, which was unveiled on George III’s golden jubilee in 1809, in front of St Martin’s church (the statue has since been moved a couple of times, but is now sited close to its original position). Mary used to sell her butter and eggs by the Castle Inn (or Hotel) which was between the statue and the corner of Castle Street (the exact spot is marked as a green “10” on the map at Eighteenth Century Birmingham).

David Cox, High Street Market, Birmingham, 1827 © Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

In 1801, the Birmingham authorities started to clear the higgledy piggledy shops and dwellings in the area beyond St James’s Church known as the Bull Ring and moved the main market there. The High Street market remained, perhaps smaller than it once was, but still busy thriving by the time Mary sold her goods there.

Mary was a well-known and well-liked in her home village of Erdington and also in Birmingham. After her death, numerous broadsides and songsheets about her murder were published and sold throughout Warwickshire and a three-act play by George Ludlam, titled The Mysterious Murder: Or, What’s the Clock?, was performed to appreciative crowds at markets and fairs even before the legal process involving her alleged rapist and murderer was exhausted. The audiences would have been made up of people of the same rank and class as Mary – farm labourers, domestic servants, carters, small businesspeople. These people were the frequenters of the markets and were her natural supporters, whether they knew her personally or not. Naturally, they were outraged and dismayed at the subsequent failure to punish her killer and the cynical tarnishing of her reputation that followed.

The Murder of Mary Ashford is published on 31 May 2018 by Pen & Sword. It is available for pre-order.

The Murder of Mary Ashford is published on 31 May 2018 by Pen & Sword. It is available for pre-order.

Notes:

Pye, Charles, A Description of Modern Birmingham, Whereunto Are Annexed, Observations Made during an Excursion round the Town In the Summer of 1818, Including Warwick and Leamington (1819). Birmingham: J. Lowe. ↩According to Eighteenth Century Birmingham the name is from the traditional spot where bulls were tethered before slaughter rather than because it was the site of bull-baiting. ↩The post Where was Mary Ashford’s spot at Birmingham market? appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

May 2, 2018

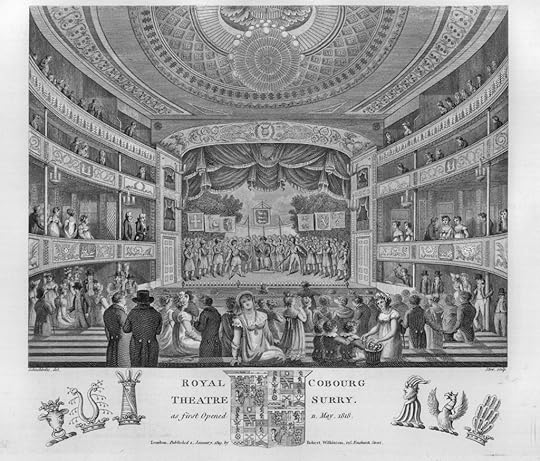

The opening night of the Royal Coburg Theatre, 11 May 1818

‘The last scene of Trial by Battle’ shows the interior of the Royal Coburg, with Geralda (centre, front) looking appealingly out of the frame and a cast of medieval-style soldiers on stage, Baron Falconbridge and the honourable smuggler Henrie facing each other off on either side of an adjudicator. From Wilkinson, R. (1819). Londina Illustrata. Vol. 2. London: Robert Wilkinson. Courtesy of Tufts University Digital Collections & Archives.

My article about the extraordinary first performance at the Royal Coburg (now known as the Old Vic) has been published on Vauxhall History.

Trial by Battle by William Barrymore used the story of Mary Ashford and Abraham Thornton (the subject of my next book – published on 31 May 2018) as the basis for a medieval-style melodrama.

The post The opening night of the Royal Coburg Theatre, 11 May 1818 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

April 17, 2018

Six images of schools in the Georgian era

Education was not compulsory in Britain until 1880. Until then, there were many options, of varying quality: Dame schools, Sunday Schools, National schools, British Schools, ragged schools… And in parallel, the endowed schools such as Eton, cathedral schools, grammar schools, and commercial establishments such as the plethora of boarding schools. In accordance, here are six fairly random portrayals of school life. How far they reflect the truth, I cannot say.

Londoner Thomas Webster (1800–1886), known as a painter of genre scenes and especially of ‘schoolboy life’, produced this study when he was about 20, before he was admitted to the Royal Academy. He showed an astonishing talent for capturing, in impressionistic brushstrokes (aren’t the jackets on the wall wonderful!), the chaos of a one-room village school full of mischievous boys: on the right, a desk is upset, someone sports a dunce hat in the centre, while the rather aloof schoolmaster, complete with hat and spectacles, calmly peruses a newspaper, probably while admonishing the boy called up to ‘see me’.

Attributed to Thomas Webster, 1800–1886, British, A Study of ‘The Schoolroom’, ca. 1820. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

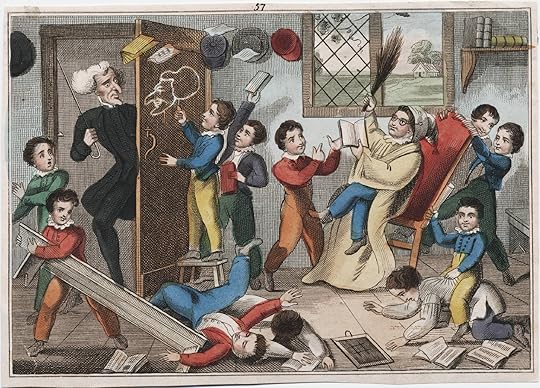

I’m not sure exactly what kind of school is depicted in the next image, a cartoon by an unknown artist – possibly a grammar school as it looks well equipped (note the tomes in the top right and the exercise books on the floor) and the master and pupils do not look particularly underfed or impoverished. The boys start a riot the minute the master is out of the room. Then he’s back, cane at the ready. One boy is apeing him by wearing his glasses and brandishing a switch, another chalks a cruel caricature. Through the window, lies nature and freedom, a contrast with the confines of the classroom. Eton famously erupted into riot in 1818.

Anonymous, The schoolmaster’s Return, 1825. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection. Note the similarity of the schoolmaster to Dr Syntax in Rowlandson’s print below.

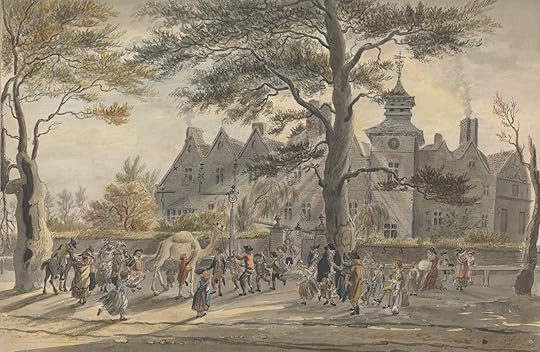

James Miller’s 1780 watercolour of Dr Fountain’s Boarding School in Marylebone’s Old Manor House (it stood opposite the Old Church, which is still there), appears to show a real event. The commotion caused by the arrival of a camel, perhaps in the possession of a travelling circus, outside the school gate. The boys coming running out to take a look, as other members of the community also congregate including two beautifully drawn ragged girls. Boarding schools were for-profit businesses (as the Yorkshire schools scandal showed so clearly). They were set up and failed regularly, much like restaurants do in our economy.

James Miller, active 1773–1814, Fountain’s Boarding School, Marylebone, 1780, Watercolor, pen and black ink, and graphite on moderately thick, slightly textured, cream wove paper, laid down on a contemporary mount, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Dr Fountain’s later became a boarding school for girls. I have previously blogged on the role of girls’ boarding school establishments, 1 which provided a route up the social ladder for aspirational families. James Gillray’s satirical print in which Farmer Giles and his wife attempt to use their daughter’s faultering piano playing to impress their rather uninterested neighbours in the drawing room at Cheese Farm. You can practically hear the sneers echoing across time.

Gillray, James, 1756-1815, Farmer Giles & his wife shewing off their daughter Betty to their neighbours on her return from school drawn by an amateur ; etch’d by Js. Gillray. Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library.

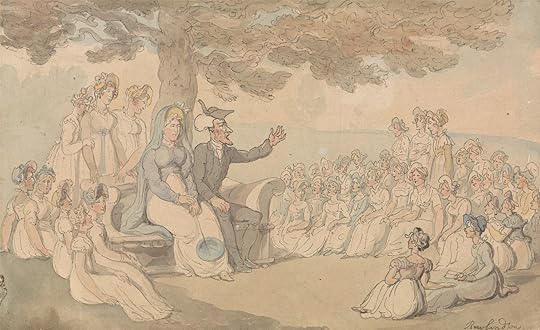

Thomas Rowlandson’s watercolour sketch of Dr. Syntax lecturing the pupils of a boarding school for young ladies, overseen by a demure mistress, portrays an ideal of compliant female innocence. They sit in rapt attention, hanging on ‘the wisdom of his [Dr. Syntax’s] tongue.’ Rowlandson’s illustrations accompany a text by William Coombe 2 in which he describes the girls:

Some were rosebuds of the day,

Some did their op’ning leaves display

Thomas Rowlandson, Dr. Syntax Visits a Boarding School for Young Ladies, 1821. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Thomas Rowlandson was rather more concerned with the ‘op’ning leaves’ in his earlier print of a nubile (and probably naive) young woman eloping from a boarding school to join her soldier lover, who upskirts her leeringly while she stands on his shoulders. A servant loads her trunk into the coach, symbolising the transfer of all her worldly, not to mention her bodily, goods to her husband.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Elopement, 1792.

Notes:

On Geri Walton’s website. ↩The Second Tour of Doctor Syntax: In Search of Consolation, a Poem. ↩The post Six images of schools in the Georgian era appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

April 3, 2018

Five views of the countryside at dawn

My thoughts lately have turned to how dawn was captured in art in the Long 18th Century, no doubt influenced by my research for my third book, The Murder of Mary Ashford (to be published by Pen & Sword on 31 May 2018).

My thoughts lately have turned to how dawn was captured in art in the Long 18th Century, no doubt influenced by my research for my third book, The Murder of Mary Ashford (to be published by Pen & Sword on 31 May 2018).

Mary Ashford, a farm servant from a poor family, was murdered in the early hours of 27 May 1817 after leaving a party after midnight with a local bad lad and walking about the country lanes with him. He was tried for the crime but acquitted. My challenge was to work out whether he was indeed guilty or, as many believed, whether Mary had died through accident or suicide. One theme that emerges from the story is the number of people who were going about their business in the early hours: farm workers, dairymen and women, road builders.

So, in memory of Mary, here are five images of dawn. In keeping with the reality of Mary’s existence and terrible end, all of them depictions of real scenes (albeit some of them idealised) rather than classical landscapes.

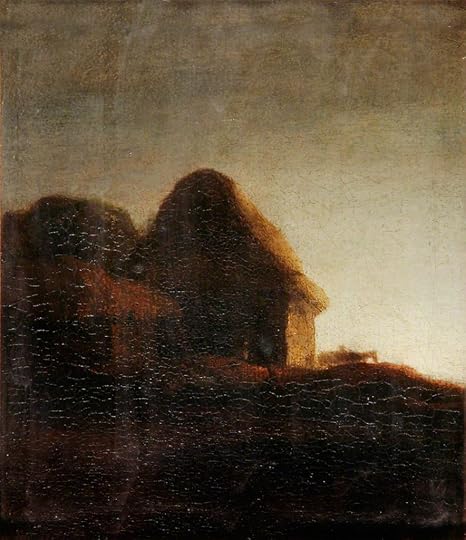

John Crome (attributed), Early Dawn (1821 or before). Norfolk Museums Service, via ArtUK.

Norfolk artist and teacher John Crome (1768–1821), the son of a weaver, was the founder of the Norwich School of Painters, who mainly concentrated on landscape. He studied Dutch 17th-century painters, but his later work, including this painting, shows an increasing naturalism and an interest in atmospheric effects. The sun coming round the edge of the cottage here makes it look almost on fire.

Peter de Wint, A Drover at the Edge of a Wood, Lincoln in the Distance; The Collection: Art & Archaeology in Lincolnshire (Usher Gallery) via Art UK.

Born in Staffordshire the son of an English doctor of Dutch extraction, Peter de Wint (1784–1849) was a prolific painter of landscapes throughout Britain. He first visited Lincoln in 1806 and visited it many times subsequently (his wife was from the city). The image is so dark I am not sure exactly where the drover is in this picture.

John Laporte, Morning – River Scene With Figures Near a Cottage (undated). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

This is one of my favourites and shows a landscape not too different from the one Mary Ashford moved through near Birmingham. There is plenty of activity: a couple with a child greet a woman on the path, boats are on the move on the river, and on the left a cottager and a journeyman converse. The painting has a pleasingly naive quality that makes you believe that it is true to life. John Laport (1761–1839), who was French Huguenot heritage, is thought to have lived in London and Ireland. In 1798 he published Characters of Trees. His interest in them is obvious here.

John Constable, Cloud Study, Early Morning, Looking East from Hampstead (1821). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

When his wife started showing symptoms of tuberculosis, John Constable rented a house in Hampstead, then a country village, almost every summer between 1819 and 1826 and in 1827 leased a house in Well Walk. He made many oil sketches of Hampstead views, of which this is one.

Francis Wheatley, Morning (1799). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Finally, we have Francis Wheatley’s late summer or autumn-set ‘Morning’ in which women and children start the day as the sun rises beyond the trees. The women churn butter and wash cloths while the youngsters assist by bringing firewood or holding the buttermilk. Mary Ashford, who was a servant on her uncle’s farm at Langley Heath, would have recognised this scene. She regularly took butter and eggs into Birmingham to sell at the market there, and did so on the morning before she died.

The post Five views of the countryside at dawn appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

April 1, 2018

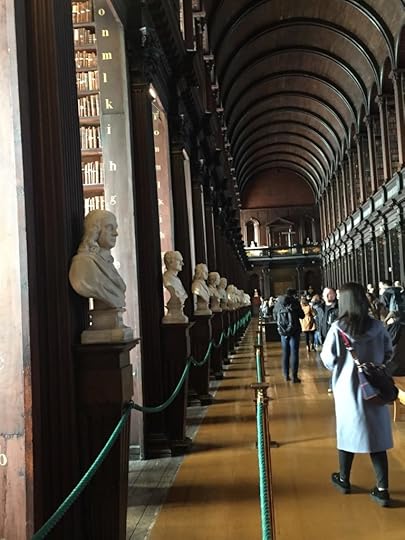

The Long Room at Trinity College Library, Dublin

With libraries under pressure – in my home borough they are being closed, reduced to unstaffed stacks, and, bizarrely, reconfigured as gyms (it’s not a pretty story) – my feelings around libraries are heightened. So when, earlier this month, I was in Dublin I made sure to revisit the Long Room at Trinity College, if nothing else to see a beloved book collection being cared for and celebrated and also to breathe in that unique perfume than emanates from a combination of ancient paper, calfskin, string and glue.

With libraries under pressure – in my home borough they are being closed, reduced to unstaffed stacks, and, bizarrely, reconfigured as gyms (it’s not a pretty story) – my feelings around libraries are heightened. So when, earlier this month, I was in Dublin I made sure to revisit the Long Room at Trinity College, if nothing else to see a beloved book collection being cared for and celebrated and also to breathe in that unique perfume than emanates from a combination of ancient paper, calfskin, string and glue.

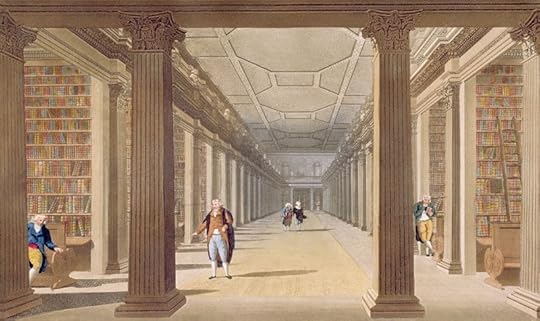

Long Room at Trinity College by James Malton (18th century)

The Long Room is indeed long: 65 metres (200 feet). Originally it had only one level and a flat roof, but it was extended upwards in 1860 and is now two storeys with wooden barrel-vaulting.

A central index gives the exact location of individual volumes on the shelves, which are identified by upper and lower case letters. Any member of staff will explain the system to you.

The expansion was necessary because the library was full. Since 1801 Act of Union Ireland was part of the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and its national library could claim the right to a copy of every book published.

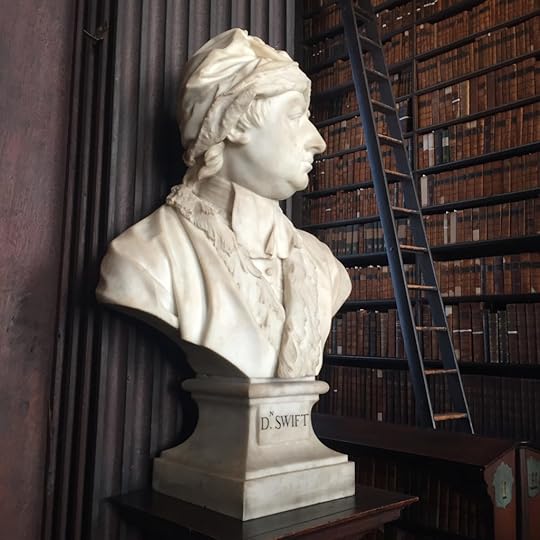

Lining both sides of the room are marble busts of famous philosophers and men connected with Trinity (there are no women, it’s superfluous to say), a collection started in 1743 with 14 by Peter Scheemakers. That of writer Jonathan Swift, Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, by Louis François Roubiliac is considered to be the best.

Lining both sides of the room are marble busts of famous philosophers and men connected with Trinity (there are no women, it’s superfluous to say), a collection started in 1743 with 14 by Peter Scheemakers. That of writer Jonathan Swift, Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, by Louis François Roubiliac is considered to be the best.

Dean Swift, Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, poet, political satirist, author of Gulliver’s Travels, is commemorated in Roubiliac’s marble bust.

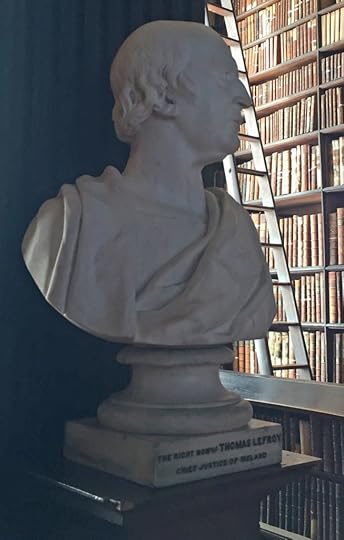

Tom Langlois Lefroy is also in represented in the collection. Aged 76, and after a long career in the law, he was appointed Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, but as a young man he had danced and flirted with Jane Austen. However, their relationship came to nothing.

Friday. — At length the day is come on which I am to flirt my last with Tom Lefroy, and when you receive this it will be over. My tears flow as I write at the melancholy idea. Letter, 14 January 1796

Marble bust of Thomas Lefroy

Lefroy eventually returned to Ireland to practise at the bar.

Dublin is noted for another ancient library. Marsh’s was established by Narcissus Marsh (1638-1813) in 1707 and was the first public lending library in Ireland. It is currently undergoing renovations so I did not get to visit it and I will try to do so when I am next in Dublin.

The post The Long Room at Trinity College Library, Dublin appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

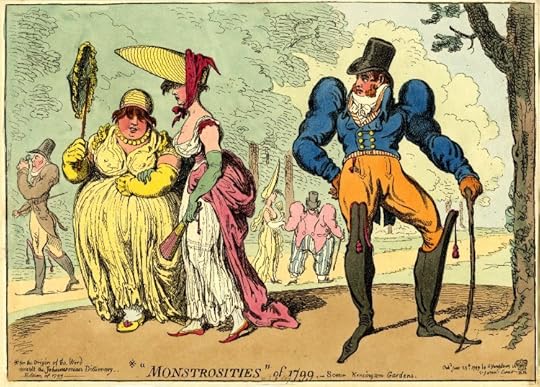

James Gillray: Part 1 – Monstrosities of 1799, Kensington Gardens

For a recent landmark birthday some kind and generous friends clubbed together to give me a hand-coloured print by James Gillray. As you can imagine, I was – and am – utterly thrilled with it. It set me off on a bit of a mission to find out more about Gillray and Hannah Humphrey, the woman who published it and who provided a home for Gillray for much of his adult life.

James Gillray’s satirical prints are among the most biting, bitchy and cruel of the cartoons produced in the long 18th century. No one, whether humble or high-born, escaped his scorn. His work has been described as ‘corrosive acid poured relentlessly on mankind’ 1.

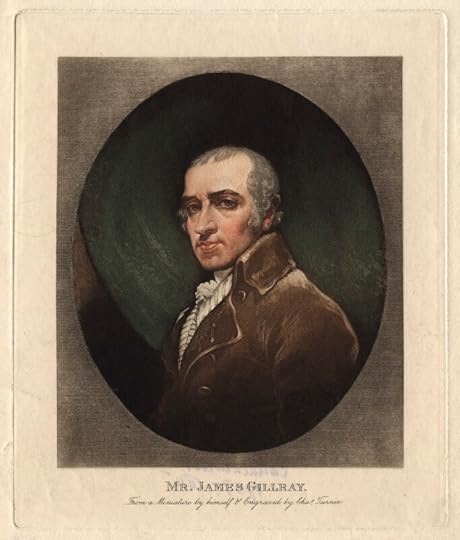

James Gillray, by Charles Turner, after James Gillray, mezzotint (circa 1800) © National Portrait Gallery, London

Born in 1756 or 1757 in Chelsea, where his Scottish soldier father was a pensioner, Gillray first trained as a letter engraver but was soon bored and went off with a band of strolling performers instead. On his return to London he enrolled at the Royal Academy, where he started to produce etched caricatures heavily influenced by Hogarth under several pseudonyms.

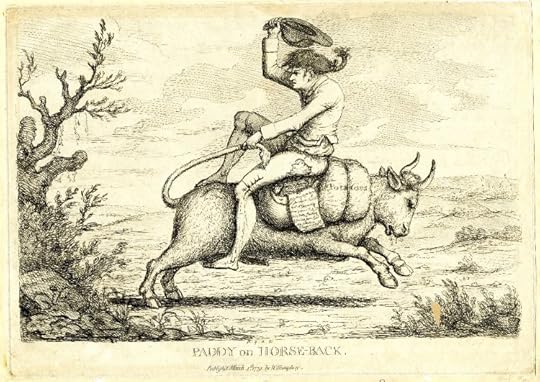

James Gillray, Paddy on horse-back (1779). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Gillray’s first attributable etching, produced when he was in his early twenties, was Paddy on Horse-back (1779), which shows an uncouth Irishman seated backwards on a bull galloping across open country towards London (St. Paul’s is visible on the right) where he hopes to make his fortune. The print was published by William Humphrey, whose sister Hannah later inherited his business and continued to publish Gillray (more about her in Part 2).

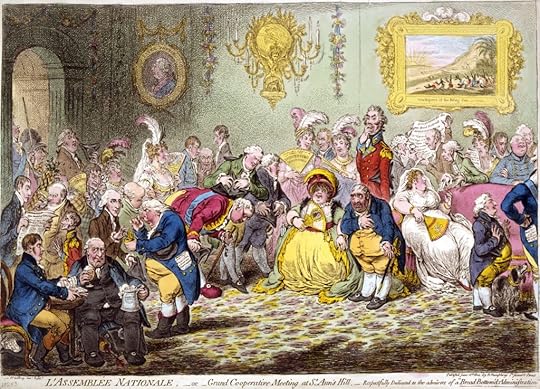

Despite receiving a government pension, Gillray’s soul was not for sale – he targeted politicians of all stripes and, of course, the Royals, who provided plenty of inspiration. Although George III did not really ‘get’ the humour, his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, did and was sometimes deeply upset by it. He was known to have acquired in 1804, secretly, through a chosen third party, the copper plate of L’Assemblée Nationale purely in order to destroy it and halt further circulation. The portraits were, it appears, too near the knuckle.

James Gillray, L’Assemblée Nationale ; —or — Grand Co-operative Meeting at St. Ann’s Hill. — Respectfully Dedicated to the admirers of “A Broad-Bottom’s Administration.” (1804). A reception given by Charles James Fox and his wife (centre) for various groups and friends of the Prince of Wales (bisected on the far right), all opposed to the government. British Political Cartoon Collection (Library of Congress)

The print I was given is “Monstrosities” of 1799, shown below, a satire on the extremes of fashion. The print is all about titillation and cheap allure. The impressive gentleman on the right is thought by some sources to be Thomas Johnes (1748–1816), a gentleman farmer and M.P., of Hafod in Cardiganshire – which presents us with a problem.

James Gillray, Monstrosities of 1799. Scene Kensington Gardens, published by Hannah Humphrey © The Trustees of the British Museum

Johnes was cultured and kind and, if his commissioned portrait is anything to go by, not particularly vain or style-conscious. He was notable for his attempts to upgrade the estate he inherited and to transform the lives of his poverty-stricken tenants. There is nothing about the dandyish figure in Monstrosities, who sports ridiculous over-the-knee tasselled boots, fullsome sideburns, soaring shoulder pads and a boldly sexually declaratory expression, that screams Welsh farmer.

Welsh gentleman farmer Thomas Johnes, who may or may not have been the model for the man on the right of Gillray’s etching.

However, there is a passing facial resemblance between him and Johnes, although Johnes would have been over 50 when the print was published. Perhaps Gillray was being ironic and the print was an in-joke whose meaning is now obscure. 2 Further evidence of Johnes is in the note in the bottom left corner, asking us to consult the ‘Johnnesonian [sic] Dictionary Edition of 1799’. One possibility is that it is not Thomas Johnes who is referenced but some other member of the family. If anyone can solve the mystery, please get in touch.

The women’s attire is just as extreme as the men’s. The taller of the two in the foreground wears an over-sized ‘poke’ bonnet and her gauzy, translucent gown is, like her companion’s, obscenely revealing. She sports a cork rump (for more on these read All Things Georgian’s wonderful post False Rumps!) and they both have hair cut short in back with a long frizzed fringe.

Seven years after this print was published, Gillray’s eyesight began to fail and his output dropped. Depressed, he turned to drink. In 1811 he suffered a bout of severe mental illness and attempted suicide. Mrs Humphrey took care of him until he died in 1815, aged only 58. He was interred in St James’s churchyard in Piccadilly. His work was hugely influential. In 1818, Cruikshank produced the first of a series of satirical prints titled Monstrosities. His take on absurd contemporary fashions harked back to Gillray’s.

George Cruikshank, Monstrosities of 1818. British Cartoon Collection (Library of Congress)

Notes:

Frédéric Ogée, James Gillray, London. The Burlington Magazine, Vol 143, No 1183 (Oct. 2001), pp. 644–645. ↩R. J. Moore-Colyer described Johnes as ‘an exceptionally cultured squire’ in his 1992 A Land of Pure Delight: Selections from the Letters of Thomas Johnes of Hafod, Cardiganshire, 1748-1816. Lladysul: Gomer Press. ↩The post James Gillray: Part 1 – Monstrosities of 1799, Kensington Gardens appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

James Gillray – Part 2: Hannah Humphrey and the print shops of London

James Gillray, Monstrosities of Kensington Gardens, 1799. Published by Hannah Humphrey © The Trustees of the British Museum

In my previous post on James Gillray, I looked at “Monstrosities” of 1799 – Kensington Gardens, a copy of which was given to me for a recent birthday. One of my kind benefactors asked how people would have bought copies of such prints. Here I outline some of the aspects of the satirical print business, including information about Hannah Humphrey, who published Gillray for most of his life.

It is not a long journey from the satirical prints of Hogarth, Gillray, Rowlandson, Cruikshank to the cartoons of Steve Bell, Martin Rowson, Ben Jennings and others. But while the work of the latter is published in newspapers (and online of course), this distribution channel was not available in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Instead, prints were usually sold singly in dedicated print shops in the West End of London. There were also dealers in the area around St Paul’s in the City, but I will confine this post to those in the West End. Not all print shops dealt exclusively in engravings – books and maps were often also sold.

Among the most important dealers was Samuel William Fores, a Scotsman initially based in Piccadilly and from 1795 at the corner of 50 Piccadilly 1 and Sackville Street, where windows on two sides of his premises allowed him plenty of space to advertise his wares. Although Fores sold the work of many artists, his most significant client was Isaac Cruikshank. Fun fact: For a while, Louis Philippe, duc d’Orléans, who went on to become King Louis Philippe I, lodged on the first floor, above Fores’ shop.

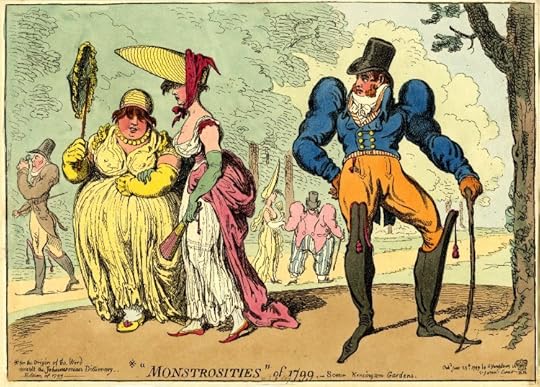

Attributed to Isaac & George Cruikshank, Folkstone Strawberries or more carraway comfits for Mary Ann, 1810, shows the front of S.W. Fores’ shop at the corner of Sackville Street and Piccadilly. Note that the majority of the items shown in the window are books rather than prints. Credit: The Print Shop Window

One of Fores’ direct rivals was William Holland, whose shop was located from 1782 at 66 Drury Lane and from 1788 at 50 Oxford Street. Gillray was initially among Holland’s artists until he was aligned exclusively with Hannah Humphrey. In 1793 Holland was imprisoned for selling a work by the radical Thomas Paine.

Richard Newton, William Holland’s Print shop c. 1794. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Unlike Fores and Holland, and later Rudolph Ackermann in the Strand, Hannah Humphrey (1745–1818) specialised in satirical prints – that is all she sold. She had inherited the business from her brother William when it was based in St Martin’s Lane and moved it first to Old Bond Street and subsequently to New Bond Street and then to 27 St James’s Street. Humphrey was that rare beast: the Georgian independent businesswoman.

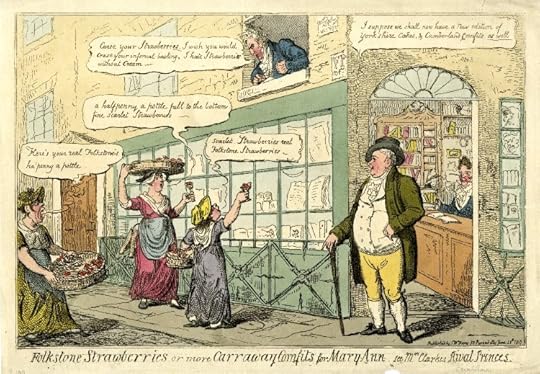

James Gillray, Two-penny whist (1796). Published by Hannah Humphrey, who is portrayed on the left. © National Portrait Gallery

Gillray lodged with Humphrey for twenty years and although some suspected an illicit relationship between these two single people it was in all probability platonic. They were clearly friends. When Gillray developed poor sight and descended into mental illness and alcoholism at the end of his career and was no longer able to work, Humphrey cared for him until his death.

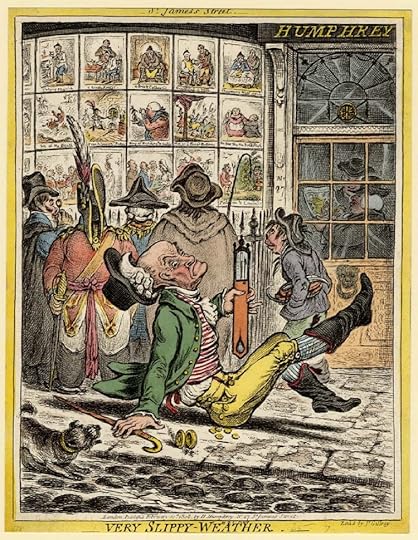

James Gillray, Very Slippy-Weather, showing Humphrey’s shop front in detail (1808) © The Trustees of the British Museum

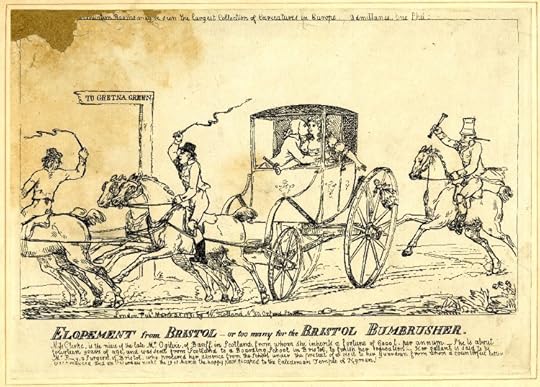

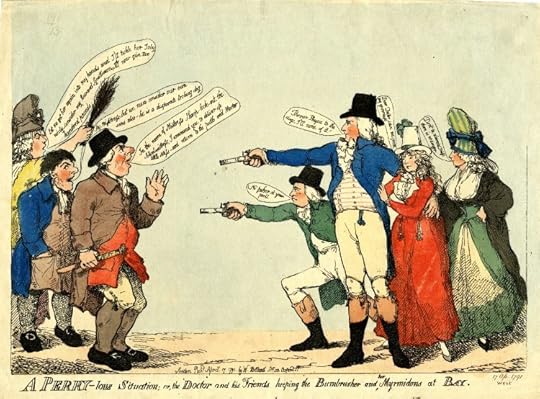

Although Gillray’s prints were pricey, neither he nor Humphrey made a fortune. There was simply not much money in the sector. To boost income print sellers occasionally put on exhibitions and charged the public for entrance. Sometimes a particular print would attract a crowd, which was good for business. This was the case with Elopement from Bristol– or too many for the Bristol bumbrusher and A Perry-lous situation; or, the doctor and his friends keeping the bumbrusher and her myrmidons at bay satirising the tragic case of the abduction and forced marriage of a 14-year-old heiress Clementina Clerke by Richard Vining Perry in 1791 and the frenzied efforts of Clerke’s former schoolteachers to bring Perry to justice for doing so. 2

Anon., Elopement from Bristol- or too many for the Bristol bumbrusher (1791), published by William Holland © The Trustees of the British Museum

Anon., A Perry-lous situation; or, the doctor and his friends keeping the bumbrusher and her myrmidons at bay (1791). Published by William Holland.

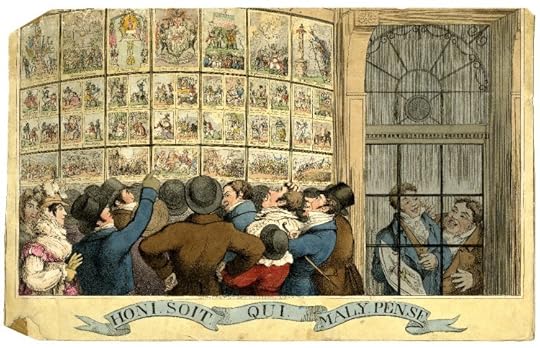

The popularity of Gillray’s work fell off as the 19th century progressed. Humphrey’s business was inherited by her nephew George, who sold it at auction in 1835. 3

An 1821 caricature of Humphrey’s shop on St James’s Street. The figures seen through the door on the right are thought to include George Humphrey.

Notes:

Later renumbered as 41 Piccadilly. ↩I wrote about this notorious case in 2013. ↩Acknowledgement: The work of Mathew Crowther at The Print Shop Window, Heather Carroll at The Duchess of Devonshire’s Gossip Guide to the 18th Century and Robert L. Patten, Conventions of Georgian Caricature. Art Journal, Vol 43, Winter 1983, pp. 331-338 has been helpful in writing this post. ↩The post James Gillray – Part 2: Hannah Humphrey and the print shops of London appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

Five breeds of dog in the Georgian era

The children have left home… (almost). I need to do more exercise… (too inclined to be at my desk). Our dear cat has ascended to feline heaven… All this means we are now, apparently, contemplating Getting a Dog. I am a dog virgin so this is a whole new world for me.

Naturally, this topic set me to thinking about the depiction of dogs in the Georgian era.

I’ve chosen five breeds to look at, starting with the Labrador and the Poodle, only because should we acquire The Aforementioned Dog, it will likely be a Labradoodle, bred, I am assured, to combine the Lab’s good nature and the Poodle’s intelligence.

Despite its name the Labrador is not from Labrador but from Newfoundland. One school of thought says that before the arrival of Europeans, there were probably no dogs in the area and that the first settlers, most of whom were fishermen from south-west England, brought their own dogs with them. These dogs had short oily coats and were ancestors of the Newfoundland, a large dog interbred with the Mastiff in order to haul carts in the inhospitable climate, and the St. John’s Water Dog, the forebear of the Labrador. The St John’s was adept at retrieving nets, lines and ropes and diving underwater to get fish that had slipped from their hooks. The breed has died out but traces of its white chest, feet, chin, and muzzle can be seen in the occasional white patches on modern Labs.

Charles Joseph Hullmandel, after Edwin Landseer, Cora, A Labrador Bitch (1823). Five Colleges and Historic Deerfield Museum Consortium. Note the white on the tail, paws, chest and chin.

The poodle is thought to have originated in Germany and been introduced to France by German soldiers. Prized for its elegance and therefore much favoured in the royal courts of Europe, appearing to Louis XVI as his pampered companion, it was also a working dog of high intelligence and with a strong hunting instinct. The oldest variation, the Standard, was used as a water retriever and, from the 17th century, a military dog.

Charles Towne, Chestnut Hunter and a Dog in a Park. Photo credit: Walker Art Gallery

Hogarth’s Pug looks rather stringy and long-limbed compared to modern, compact versions and does not display the characteristic three winkles and a vertical bar on the forehead that resemble the Chinese character for ‘prince’. The breed originated in China and came to Britain through trade links.

William Hogarth, The Painter and his Pug (1745). Photo credit: Tate

The Pug’s small size made it popular as a lapdog for genteel ladies. Hogarth owned several Pugs, of which Trump was probably the most well known. Possibly the Pug was not popular with Jane Austen, who assigned one to the appalling Mrs Norris in Mansfield Park.

Henry Bernard Chalon, A favourite Pug bitch; A Pug dog (one of a pair). Sold at Bonhams

J. Scott after Philipp Reinagle, A small and a large pug are standing outside the gate of a walled garden (1804). Wellcome Images, London.

The English Bulldog, whose tenaciousness is viewed by some as an embodiment of the spirit of the nation, was originally used by butchers to hold wild bulls, its powerful jaws able to lock on to the bull’s nose long enough to allow a rope to be put round its neck. The Bulldog was also used for ‘sport’ – to bait bulls and to fights other bulldogs. After the 1835 Cruelty to Animals Act outlawed bull- and bear-baiting the Bulldog developed into a shorter, squatter dog with a notably kind nature.

Unknown artist, Bulldog Facing Left (early 19th century). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

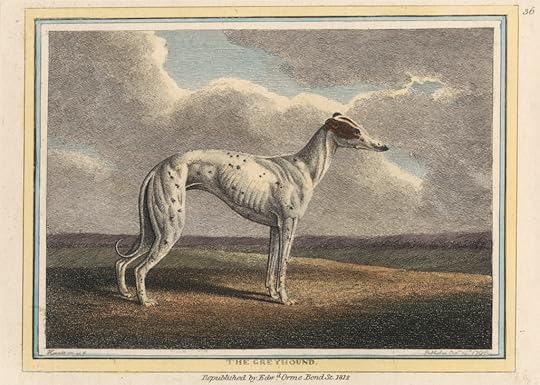

Finally, the Greyhound, whose origins stretch back 4,000 years to Egypt where its ancestors were depicted on the walls of a tomb. The Greyhound has long been associated with royalty and aristocracy and was traditionally used in the hunting of game and in coursing (two hounds chasing a flushed rabbit or hare in an open field).

Peter Casteels, Three Greyhounds in a Room (undated – Casteels active in Britain from 1708). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Samuel Howitt, The Greyhound (1812). Yale Center for British Art; Yale University Art Gallery Collection.

The post Five breeds of dog in the Georgian era appeared first on Naomi Clifford.