Naomi Clifford's Blog, page 10

June 27, 2017

1818: The murder of a gamekeeper at Crockingham Corner, Epsom

Footprints and their meaning played a central role in my latest writing project, a murder trial in 1817. The underlying issue at the trial was how much weight should be given to circumstantial evidence especially when balanced against an alibi. As I sniffed around the archives looking for other similar cases, I came across the murder of a young gamekeeper, probably by poachers, for which Thomas Osborne stood trial at Kingston. There was plenty of evidence against him – but would it strong enough?

On Sunday 2 August 1818 Elijah Cox, a gamekeeper employed on James Tessier’s estate in Epsom, Surrey, failed to appear for breakfast in the servants’ quarters of James Tessier’s estate in Epsom, Surrey. When he did not come to church, nor to dinner, 1 his fellow servants became increasingly concerned and two of them left the table to look for him. They knew that Eli, who was extremely conscientious, had spent the night at the farmhouse on the estate in order to get up in the small hours and look for poachers.

At the edge of the estate, at Crockingham Corner, they noticed a bent railing and soon afterwards discovered Eli’s body lying on his back on the other side, in Sir Gilbert Heathcote’s woodyard. 2

Woodcote Park, engraved by J.H. Kernot after a picture by T. Allom, published in A Topographical History of Surrey, 1850. With kind permission of ancestryimages.com.

He had been killed in a particularly horrible way: garrotted by inserting a stick through his silk neckkerchief and twisting, creating what seamen called a Spanish windlass. His right arm was broken and had a long, deep cut. There was a severe gash across the fingers, the little finger of the other hand was hanging by a thread and he had sustained a head wound. Eli’s pistol, the stock of which was broken, had been discharged.

There were plenty of clues. Lying a few yards from the body was an old sock made out of a hat. The marks of bloody fingers were found on a gate, and two knives were found nearby. The first assumption was that Eli was killed by a gang of poachers who had recently been plaguing the neighbourhood – the flick of a hare had been found strewn around the woodyard.

Eli’s body was carried to the laundry of his master’s house and where the surgeon, John Winslow Mayd performed a postmortem. 3

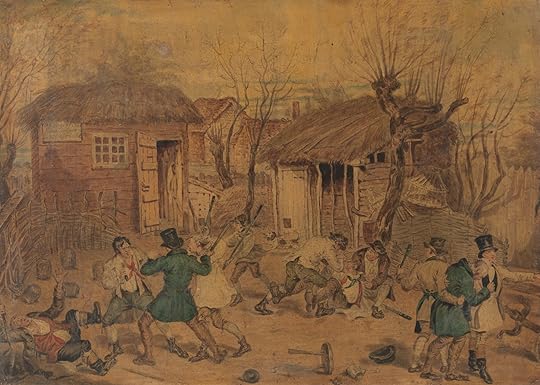

C. Blake, The Poacher’s Progress. c 1825. The poachers are scuffling with constables in a skittle ground. Courtesy Yale Center for British Art.

Soon after the murder, three men, Thomas and James Arnold and Thomas Osborne, were arrested on suspicion of murder. The next day, Sunday, an inquest was held at the Hare and Hounds in Epsom. A fruit gardener told the court that he had heard the report of a gun at about five in the morning and someone cry out ‘Oh Lord’ twice. Thomas Page, who lived fifty yards from the scene of the murder, also heard the gun. At six o’clock he and his wife looked out of the window and saw their neighbour Thomas Osborne, a journeyman gardener, go into his house. Some of the witnesses said he had seen Osborne with a clasp knife like the one found at the scene but could not swear it was the same. One of them said that on the day after the murder he used a case knife. The jury brought in a verdict of Wilful Murder by some person or persons unknown.

The three men were examined by magistrates. Thomas Arnold, a reaper, told the magistrates that he had been visiting John Halliday, a shoemaker, and had intended to sleep at his mother’s house but got drunk and slept outside on a stack of oats, after which he went to his brother’s for breakfast. He was unexpectedly uncooperative when the magistrates asked him where he was on Friday night. He told them to mind their own business, ‘stating that wherever he might have slept on Friday could not in any way be connected with the inquiry about the murder. He was willing to give an account of himself from Saturday to Sunday, beyond that time he did not conceive he had a right to be questioned.’ He had thought it was a joke when told he was suspected of murder and that he was being taken before the magistrates to punish him for being drunk. His brother James denied any knowledge of the crime and said he spent the night at Banstead. He said his brother was a ‘wild rackety chap…[but] he was as innocent as a new born child of the murder and he hoped his brother was.’

Thomas Osborne had a cut on his forehead and scratches on his face and a loaded gun in his house. Eli’s powder flask bearing bloodstains was found near Osborne’s garden fence.

Osborne claimed that he had been asleep in his house and although the gunshot had woken him, it was normal to hear shooting in the area so neither he nor his wife thought much of it. Mr Doherty, a local gentleman, had given him valuable linen to look after and lent him the gun to safeguard it. The damage to his face was from a fall from an apple tree into a gooseberry bush. He offered to strip to prove that he had no marks of violence on him (none were found). Various witnesses gave inconclusive evidence, including his neighbour Thomas Page, who said he had seen him in his garden between 6 and 7 on the morning of the murder.

After a long and thorough conversation, the magistrates dismissed all the suspects. A few days later, three other men were arrested: John Jones, William Borer and William Jeffreys, who were known poachers (‘very extensive and daring’) but they were also discharged for lack of evidence.

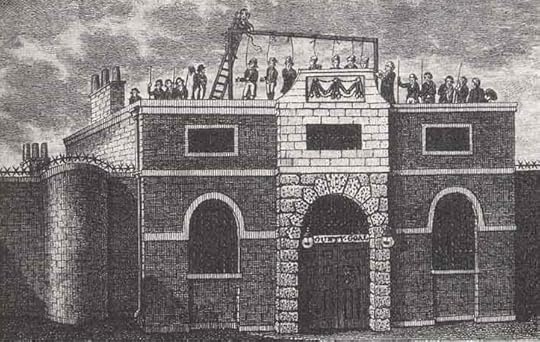

Horsemonger Gaol in Surrey, via capitalpunishmentuk.org

Thomas Osborne was taken up again. A bloody and torn apron, waistcoat and pantaloons and a freshly washed but ripped up shirt had been found hidden in his bed. He was carted off to Horsemonger Gaol in Surrey (south London). 4

In August Osborne appeared at the coffee house in Epsom in front of seven magistrates. Seasoned barrister Peter Alley and solicitor James Harmer 5, who appeared for him, told him not to speak. Some new evidence came to light. May, a police officer, said that Osborne was wearing socks similar to that found at the scene, and that one was more worn than the other. Osborne was a good-looking, fair-haired man, about 27. As a veteran of the navy, he would have been familiar with the knot used to make a Spanish windlass. The prisoner was sent for trial.

On 6 April 1819, Osborne appeared in front of Justice James Allan Park at the Kingston assizes. The trial excited ‘an uncommon degree of interest’ due to the barbarity of the murder. During the eight-hour trial, all the witnesses appeared again, including the neighbour, Thomas Page, now added some details to his evidence: on the morning of the murder, Osborne appeared to be sweating profusely and ‘in a great heat’. Later he fetched water and shut himself in his house; then he hung out his shirt and neckcloth to dry.

James Harmer (1777–1853)

John Gurney, William Bolland and John Adolphus, all heavyhitters, prosecuted but the defence was ‘extremely well drawn up’, in the opinion of The Times reporter, the brief probably prepared by Harmer. The defence case was that at six o’clock on the morning of the murder Osborne had gone into his garden to pick apples but had fallen from the tree and scratched his face in the gooseberry bush. Then he took the apples to his father’s house and stayed there half an hour, before returning home. He was vehement that he had had the ‘highest regard’ for Eli. The clothes under the bed had been there six or seven months – he had no use for them because he had put on weight. He admitted to wearing old hats as socks, but this was what many poor people did. He knew nothing of the bloody clasp knife or the powder flask.

Several witnesses gave Osborne a good character. It became clear that Page did not disclose the material part of his evidence until after a reward of £200 had been offered for detection and conviction of the murderer. That Osborne had been released after his first appearance in front of the magistrates but failed to flee was also in his favour.

The jury conferred for about five minutes and returned their verdict, Not Guilty.

With thanks to the Epsom and Ewell History Explorer site for the newspaper transcriptions of the case.

Notes:

During this period dinner was eaten mid-afternoon. ↩Heathcote was an MP for Rutland (and also its High Sheriff). ↩J.W. Mayd, 1761–1848. ↩Horsemonger Gaol (or the New Gaol) was near Newington Causeway in Southwark. ↩Harmer may have been the model for Charles Dickens’ creation Mr Jaggers in Bleak House. Dickens and Harmer were acquainted through the Newsvendors Benevolent Institution of which Harmer was the first president and Dickens the second. Harmer defended the Peterloo rioter John Lees in 1819. ↩The post 1818: The murder of a gamekeeper at Crockingham Corner, Epsom appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

June 24, 2017

A voyage to nowhere: On board the Justitia prison hulk at Woolwich

Research on my latest project looking into an unsolved murder in the 1810s has led me to the prison hulks in the Thames. Life on these obsolete, mastless ships was miserable, with no end in sight – it could be a few months or as long as two years. You could be on a hulk for years before your country compelled you to travel to New South Wales to begin your new life of indenture. The convicts dubbed it ‘a voyage to nowhere’.

Hulks at Plymouth (undated) by Samuel Prout, reproduced with kind permission of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

The hulks were first used as prisons in 1776 when the American War of Independence made transportation across the Atlantic impossible and although they were meant to be a temporary measure they were not withdrawn until 1857. Most were moored by the Thames but there were others around the country, including Plymouth, Portsmouth and Cork.

In 1809 Sir Samuel Romilly, speaking in the House of Commons, described the hulks as ‘miserable receptacles’ where ‘extreme depravity’ took place.Most hulks were acutely over-crowded, served poor food and the convicts often suffered serious health problems. Serious outbreaks of cholera and dysentery were not infrequent. In summer the air down below was stifling, while in winter it was freezing cold. The death toll was high.

John Capper, who had been Superintendent of Prisons and the Hulk Establishment since 1814, had tried to make improvements to the food and clothing and the chaplain had ensured the prisoners had their spiritual needs attended to by providing bibles and services, but the regime remained harsh and the conditions horrible. 1

Hulks in the Medway by Francis Swaine (1730–1782). With kind permission of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

The purpose of the hulks was to provide free labour for the Woolwich naval dockyards in order to earn back the cost of accommodating and feeding them. Around 1775 it was clear that the main channel of the Thames was drifting toward the centre of the river. At Woolwich major dredging was required to stop this. Convict labour was also needed for the development of the Arsenal and the nearby docks.

James Hardy Vaux, a prisoner on the Retribution in the early 1800s, described the routine:

‘Every morning, at seven o’clock, all the convicts capable of work, or, in fact, all who are capable of getting into the boats, are taken ashore to the Warren, in which the Royal Arsenal and other public buildings are situated, and there employed at various kinds of labour; some of them very fatiguing; and while so employed, each gang of sixteen or twenty men is watched and directed by a fellow called a guard. These guards are commonly of the lowest class of human beings; wretches devoid of feeling; ignorant in the extreme, brutal by nature, and rendered tyrannical and cruel by the consciousness of the power they possess.’ 2

The Woolwich Warren was a complex of workshops, warehouses, wood-yards, barracks, foundries and firing ranges.

The Discovery prison hulk at Deptford.

FURTHER READING

Wikipedia has a list of prison hulks.

Henry Mayhew described them in 1862.

The National Archives has a page of education resources for schools.

More detail at Old Police Cells Museum website.

Notes:

Capper, J. H. , Addington, H. (1816). Papers Relating to the Convict Establishment at Portsmouth, Sheerness, and Woolwich. London: House of Commons. In 1818 Capper reported to Lord Sidmouth that ‘the convicts [on board the Justitia]… are well supplied with good and wholesome food and proper clothing, and their labour on shore upon the Ordnance works… are considered by that department of great utility.’ The chaplain, Samuel Watson, was similarly upbeat: prisoners attended prayers and some took communion, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge had provided Bibles and tracts, and there was a school for prisoners who wished to learn to read and write. ↩Vaux, J. H. (1819). Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux. London: W. Clowes. ↩The post A voyage to nowhere: On board the Justitia prison hulk at Woolwich appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

June 1, 2017

The trial of John Motherhill for the rape of Catherine Wade: 1786

To state the obvious, rape trials in the Georgian era were stacked against the victim (plus ça change, I hear you murmur). The trial was all about her and what she did rather than what her assailant may have done. For any chance of success she had to offer the court specific proofs: that she tried to prevent the rape, that she cried out for help, that she fought back physically, that she tried to run away. The accused need not say anything, whereas any anomaly in her testimony could form a reason to acquit.

In law, whores were just as entitled to justice as the most spotless of virgins. In practice, the victim generally needed to show that she was a paragon of virtue.

Rape was a capital crime, and there was always a chance a convicted rapist would be executed (although this was more usual for the rapists of children), which gave juries a moral dilemma. They simply did not see rape as deserving of death, and were often reluctant to convict for that reason.

On 11 September 1785 20-year-old Catherine Wade was raped after being dropped off by a friend near her residence in Brighton. 1

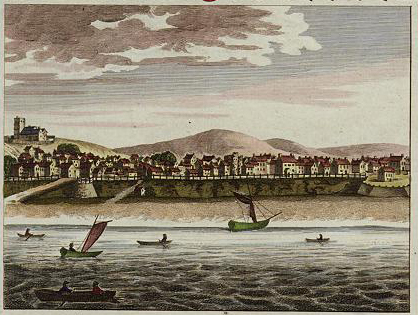

Brighton Beach Looking West, John Constable (unknown date). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection].

Catherine had spent the day with her friend Elizabeth Hart and Hart’s mother Lady Hart. During the evening, on a very wet and stormy night, she was taken home by another guest, Mr Griffiths, a surgeon, but the street where the Wades lived was inaccessible to carriages and she ended up walking up the steps and along the passage to the door alone. There she was seen by John Motherhill, a poor tailor, who started to engage her in conversation and then put his hand on her bosom and up her petticoats. He insisted that she go with him, walking down the passage behind her. It is difficult to know whether she tried to scream. If she did, no one came to her aid because the weather meant there was no one about.

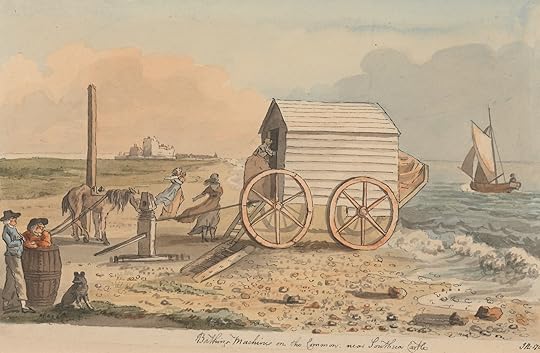

They went into a graveyard, where Motherhill raped her three times, afterwards dragging her to the beach and into a bathing machine where he raped her again. In the morning, as the water rose, she remarked that the women would soon be coming to use the machine, he led her out and let her go.

Detail: Brighton from ‘Brighthelmstone” and “Chichester’, anonymous, published in New and Complete English Traveller about 1784. Courtesy of ancestryimages.com.

Catherine’s father was frantic with worry and spent the night looking for her, joined at daylight by volunteers, one of whom arrested Motherhill after he was seen following Catherine. Motherhill more or less confessed – ‘I have been a very wicked wretch, and have deserved to be hanged a long time.’ – and was committed to Horsham Gaol. Catherine arrived home in a shocking state: bruised, dripping wet and filthy. She was put to bed and her life was thought to be in danger.

However, within hours, poor Catherine had to submit to an intimate examination by two male surgeons. At the trial on 21 March 1796 at East Grinstead in Surrey both surgeons gave evidence that she had been ‘violated’ and one suggested that if Motherhill had been suffering from a venereal infection, she was unlikely to catch it because she was in a ‘state of natural evacuation’. 2 In fact, he was found to have a ‘gleet’, a discharge caused by gonorrhoea.

Bathing Machine on the Common, near Southsea Castle, 1788, John Nixon. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Catherine gave evidence but became confused under cross-examination by Mr Rous, 3 who asked why she had not cried out when Motherhill forced her along the passage by her door (she said it was ‘fright’ – not an adequate reason in a rape trial), and did not run away or knock on doors and windows when they walked along North Street. Rous also pointed out that when they reached the bathing machine, Motherhill led Catherine up the stairs by the hand – proof that he did not force her. Motherhill’s defence was that he mistook Catherine for a woman of loose morals, of whom there were many about.

Despite Catherine’s mistakes, the jury was minded to convict. They conferred for half an hour, but then asked Judge Ashurst a question. Was there no alternative between death and acquittal? None, said the judge and so, after a further few minutes, they returned a verdict of Not Guilty.

Notes:

At that time known as Brighthelmstone. 4 She was a particularly vulnerable victim – as the prosecution barrister Thomas Erskine said at the trial of her attacker, ‘Nature had not endowed her with a strong understanding.’ She had been brought up in a convent in Calais, had only recently arrived back in England and was innocent about the world. In the words of her father, the master of ceremonies at Brighton, she was ‘unaccustomed to the deceits in the busy world.’ 5Anon. (1796). The Trial of John Motherhill, for the Rape on the Body of Catherine Wade. London: E. Macklew. ↩ It must have been so much fun to be a Georgian surgeon: you got to make stuff up for the hell of it. ↩Probably George Rous. ↩The post The trial of John Motherhill for the rape of Catherine Wade: 1786 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

May 29, 2017

Suspicious death of a female on Fulham Bridge: 28 September 1817

While researching my third book for Pen & Sword – which is about a rape-murder during the Regency period – I have been looking at other deaths and unsolved cases. The case I am investigating involves a possible sudden suicide so I was interested to find this sad tale of drunken violence and misadventure in The Observer of 28 September 1817.

SUSPICIOUS DEATH OF A FEMALE

An inquisition has been taken, before Thomas Stirling, Esq. Coroner for Middlesex, at the Swan, near Fulham-bridge, to investigate the cause of hte death of Maria Cooper, a young woman only twenty years of age, there lying dead, whom it was generally reported, was thrown off Fulham-bridge into the Thames, and drowned.

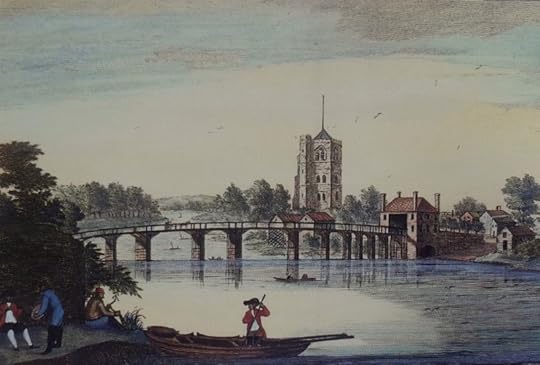

Fulham Bridge in 1742, with Fulham Church in the background (via https://lbhflibraries.wordpress.com/2...). The bridge was pulled down and replaced with Putney Bridge.

Thomas Gerrard, brush-maker, of Fulham, stated that he knew the deceased; she lived at Wandsworth; on Sunday last he was in company with a young man named Jones, at the Golden Lion, Putney; witness went to the door about nine o’clock at night, and saw the deceased come along the road; he took her to have som ebeer in the house with him and Jones; they drank several pints of beer, and she drank some spirits; he remained drinking with them till eleven o’clock at night, when he left the deceased with Jones; he went home to Fulham; the next morning he heard a report that the deceased had been pushed off Fulham-bridge by a young man.

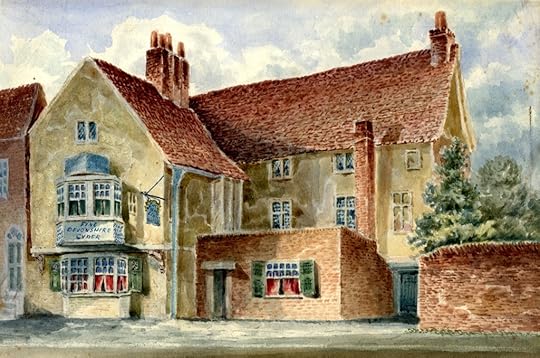

The old Golden Lion near Fulham Bridge, where Maria Cooper spent the evening drinking with Thomas Gerrard and William Jones. The pub was rebuilt in 1836. Via https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com

William Jones, tailor, at Putney, stated that he was in the company of Gerrard at the Golden Lion, Putney, on Sunday night; Gerrard went out of the room, and shortly after returned with the deceased, who sat down and drank some spirits; they remained drinking till eleven o’clock when Gerrard went home; witness sat drinking with the deceased until twelve o’clock and left the house with her; they walked together along Wandsworth-lane, and called at another public-house, and got a pint of beer and a glass of gin; they were both rather intoxicated; the deceased asked him to take a bed at a public-house; this he refused; she called him ill names; and being both tipsey, they began to quarrel; they had then got to the end of Fulham-bridge; he gave the deceased a shilling to pay for a bed for herself; he told her that he was resolved to go straight home; at that moment two gentlemen came up, and she informed them that he was ill-treating her; he denied it; they said that they would take her part; he paid the toll for her to pass over the bridge; he and the strangers walked together; the deceased kept behind about 10 yards; he heard one of the strangers call out “stop, stop;” he turned round and saw the deceased on the railings of the bridge, and before they could go to her, she had thrown herself into the water; they endeavoured to get a boat, but no one could be got; he saw her rise to the top of the water several times, and then sink; he went home immediately.

Coroner: “Do you think she drowned herself from your ill treatment?”

A: “I don’t know. I did not ill treat her.”

Coroner: “You refused to stay with her; what was your reason for that?”

A: “Because I had an idea she was pregnant, and thought she only wished that she might have an opportunity of swearing the child to me.”

Mr. Henry Gyde stated that he was walking towards Fulham-bridge on Sunday night, about twelve o’clock; a stranger was behind him a few yards, walking the same way, and overtook him close to the turnpike, at the end of Fulham-bridge; they heard two persons (the deceased and the last witness) quarrelling; they went up to them; the deceased said that Jones had struck her, but he denied it; they walked with the deceased, and promised her that they would prevent Jones from striking her again; Jones paid the toll for her, and walked over the bridge with them; the deceased purposely lagged behind; as witness, Jones, and the stranger got about twenty yards beyond the middle of the bridge: on a sudden he turned round to look for the deceased, and saw her in the act of getting on the railings of the bridge: he called out “stop, stop,” and ran towards her, but she had thrown herself into the Thames before he got to her; he went in search of a boat, but could not get one any where; it was high tide, and the force of the water carried her through the centre arch; he saw her struggling on the other side, and then sink; he went to the turnpike house and informed them of the circumstance; he was certain that she was not thrown in the water, but threw herself in, when no person was within twenty yards of her; it was a moonlight night.

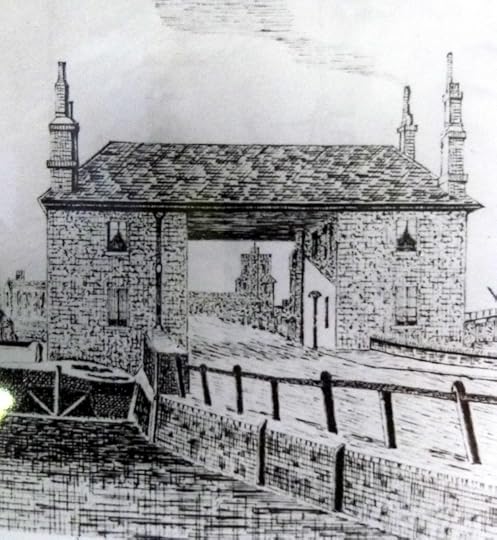

Fulham Bridge toll house. Via https://lbhflibraries.wordpress.com/2...

William Humphreys, toll-keeper, Fulham-bridge, said, that he saw the party go through the gate; they appeared to be quite intoxicated and quarrelling; he heard something fall into the water, and went towards the centre of the bridge; he met last witness & informed him that the deceased had jumped over the railings into the Thames.

The Garden of the Swan Inn, Fulham, by Thomas Rowlandson.

Thomas Phelps, waterman, Fulham, stated, that on Monday morning last, he was informed that a person had been thrown into the Thames off the bridge; he took his boat and rowed about, and at length found the body about twenty yards from the centre arch, covered with about two foot of water: he got her out and conveyed her to the Swan.

The Coroner said that there was not the remote grounds for supposing that she died from the act of any person: the only thing they had to consider was, whether she was sane or not at the time. Verdict: “Drowned herself, being at the time in a state of insanity.”

The post Suspicious death of a female on Fulham Bridge: 28 September 1817 appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

April 29, 2017

The eruption of La Soufri��re on the West Indian island of St Vincent

The young woman whose abduction is the subject of my book The Disappearance of Maria Glenn left St Vincent, and her beloved mother, as an eleven-year-old girl, just before the eruption of La Soufrière. No one understood the significance of the seismic changes that were rippling across the world…

At about noon on Monday 27 April 1812, the 28,000 inhabitants of St Vincent, both free and enslaved, witnessed the sudden and violent start of the eruption of La Soufrière, the huge volcano in the north of their tiny island. As great thunderous cracks split the air, the earth shook, a massive column of thick black smoke rose from the summit and volumes of red-hot sparks were spat into the atmosphere.

“In the afternoon the roaring of the mountain increased and at seven o’clock the flames burst forth, and the dreadful eruption began,” wrote barrister and plantation owner Hugh P. Keane. A hundred miles away on Barbados, Captain George Palmer Hawkins mistook the noise and smell for cannon fire and was convinced the French were attacking.

The volcano was not just a thing of terror — it was also sublimely beautiful, and three days after the volcano first stirred, Keane rose early to sketch the scene, with the volcano’s sulphurous vapours curling skyward and the air filled with layers of yellows, reds and rusts. His drawing, now lost, somehow made its way to an acquaintance, the artist J. M. W. Turner, who used it as inspiration for a work he showed at the Royal Academy in 1815. Turner’s painting is now in the collection of the University of Liverpool.

William Turner – The Eruption of the Soufrière Mountains (oil on canvas, 1815) © University of Liverpool

The anonymous writer of a letter to a merchant in Glasgow hired a sloop for a nighttime voyage of discovery along the coast. “We arrived in sight of it [the mountain] and about six miles distant from the crater, just as the sun went down, when the mountain appeared on fire for several miles, and vomited out streams of lava, which carried everything before it.. before we were at anchor twenty minutes, a heavy fall of stones and sand obliged us to put to sea; luckily for us we received no injury.”

Another anonymous witness provided more detail: “Although Kingston is at the distance of about twelve miles form the volcano, the inhabitants were so much alarmed, that many of them went on board of the vessels in the bay for protection, and it was not until past eight o’clock that one person could distinguish another, in consequence of the atmosphere being darkened by the quantity of ashes.” 1

The next morning, the island was in darkness. A thick haze hung over the sea and the sky filled with yellowish black clouds. The island was covered with ash and fragments of lava—and the volcano was still rumbling. Gradually it settled back into silence. 2 Two of the rivers had been completely dried up. The crops were ruined, and food had to be bought in from neighbouring islands. In all, about eighty people died, relatively few for an eruption of such force, although there were many injuries. Most of the dead and injured were enslaved people working in the sugar fields, killed in the rain of pumice.

Unknown to the inhabitants of St Vincent, the eruption of La Soufrière was only one episode of a wave of huge seismic and tectonic disturbance stretching from one side of the world to the other. In December 1811 the Mississippi River valley had been convulsed by an earthquake so severe that it woke sleepers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Norfolk, Virginia. It was followed by intermittent strong shaking which lasted until March 1812 and the aftershocks continued for five years. 3 Only thirty-five days before La Soufrière erupted, the city of Caracas in Venezuela had been almost completely flattened by two huge seismic shocks. Ten, possibly twenty, thousand people died. And the instability was not over. There was worse to come. In Indonesia, Mount Tambora began to stir and rumble and a dark cloud appeared over its summit.

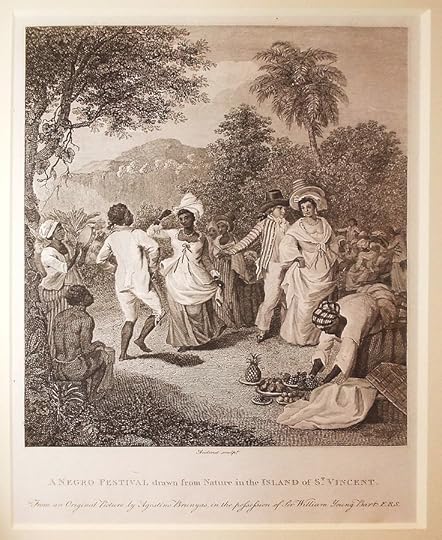

“A Negro Festival drawn from Nature in the Island of St Vincent”, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

The British press showed some interest in the eruption on St Vincent but the country was more preoccupied with the imminent naval war with the United States. The eruption, in any case, could be dismissed as just another episode in the island’s turbulent history. The French had handed St Vincent over to the British in 1763 as a result of the Treaty of Paris but took it back in 1779. The British did not regain control until 1783. The Caribbean was the most important theatre of the Anglo-French War, which did not end until 1815, and the island of St Vincent was centre stage.

Hull Packet, 7 July 1812. Image © The British Library Board.

There was also internal strife on the island. French agents had fomented the rebellion of the so-called Black Caribs, 4 the numerous racially mixed (and not enslaved) descendants of shipwrecked Africans and the indigenous islanders. The British crushed the uprising, known as the Brigands War, with force, killed the Black Carib leader and deported most of the black non-slave population to an island off Honduras. Only half of the five thousand making this involuntary exodus survived the voyage. 5

St Vincent itself was regarded as one of the jewels of the Empire. The volcano’s eruptions (there had been a major eruption in 1718) had rendered the earth richly fertile, ideal for growing the dominant crop—sugar. Between 1807 and 1834 the island was the leading producer of sugar in the Windward Islands, with the highest ratio of sugar to slave. 6 Not only that, the island was exceptionally beautiful. On 10 September 1829 James Williamson, a ship’s surgeon, made a brief visit. He regretted not getting up early enough to catch the most spectacular view of the volcano, which was “still smoking”. All the same, he was entranced. “I have seldom seen so lovely a scene,” he wrote in his diary. “There were presented to you hills and slopes covered with the most beautiful clothing of nature you can conceive. Here were deep ravines—there gently declining plains—and the tout ensemble was such that I was perfectly enraptured. …St Vincent’s is of small extent, but is indeed a gem which tho’ insignificant in size shines with a brilliancy which raises its beauty and its value far beyond others of greater pretensions, in point of size.” 7

After 1812 a string of eruptions brought disruption to the global climate. In 1813 Mount Awu in the Dutch East Indies exploded, followed by Suwanosejima in Japan and by Mayon in the Philippines in 1814. The climax of this litany of earthly disturbance was the world’s largest documented historic eruption. In April 1815, after rumbling and smoking for three years, Mount Tambora in the East Indies spewed thousands of tonnes of volcanic ash, gas and dust into the upper atmosphere.

The island of Tambora was nearly sheared in half. In the aftermath, a tsunami ripped the coastlines and for days the area was covered in darkness. The ash clouds and sulphur aerosols from the eruption, estimated as six times that of Mount Pinatubo in 1991—chilled the climate by blocking sunlight with gases and particles. The human cost was enormous. It is impossible to get accurate figures for the initial death toll but it has been estimated that ten thousand people were killed during the eruption, probably by pyroclastic flows, and a further thirty-eight thousand died from starvation on Sumbawa and ten thousand on Lombok. 8

By spring 1816 a persistent “dry fog”, which reddened and dimmed the sun, was affecting northeastern America. In Albany, New York now fell in June and did not melt, and in July and August there was lake and river ice as far south as Pennsylvania. Parts of Ireland suffered near famine conditions. Typhus, the disease of associated with cold and damp, poor hygiene and louse infestations, swept through the country. Crops failed and there were violent protests in grain markets. In May 1816, riots broke out in Norfolk, Suffolk, Huntingdon and Cambridge. Threshing machines, barns and grain sheds were destroyed. Groups of rioters armed with heavy sticks studded with iron spikes and carrying flags proclaiming “Bread or Blood” roamed the countryside. In Europe, already suffering from the destruction wrought by the Napoleonic Wars, the devastation was appalling.

This was the Year Without a Summer, sometimes known as the Poverty Year.

In Switzerland the continuous summer rainfall forced Mary Shelley, John William Polidori, Byron and their friends to stay indoors and compete to write scary stories. Shelley came up with Frankenstein and Byron with the bones of a story Polidori later wrote as The Vampyre, a precursor to Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

The abnormal weather conditions continued through the winter and into the summer of 1817, when Maria Glenn went to live with a yeoman farming family in Taunton. How much did the weather affect her fate…?

Notes:

The Times, 24 June 1812 ↩Martin, R. Montgomery (1838), History of the West Indies (Vol 5). London: Gilbert and Rivington. This account appears to rely on the uncredited diaries of Hugh P. Keane, now in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society. ↩Nuttli, Otto W. Earthquake Information Bulletin, 6 (2), March–April 1974. ↩The British colonial powers used this term to distinguish this group from the Yellow Carib and Red Carib people, who had not intermixed with Africans. ↩Hulme, P. Travel, Ethnography, Transculturation: St Vincent in the 1790s. Paper presented at the conference Contextualizing the Caribbean: New Approaches in an Era of Globalization. University of Miami, Coral Gables, September 2000. ↩Higman, B. W. (1997). Slave Populations of the British Caribbean, 1807–1834. University of the West Indies Press. ↩The diaries of James Williamson have been transcripted and are available on the National Maritime Museum Cornwall website. ↩Oppenheimer, Clive (2003). Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815. Progress in Physical Geography, 27 (2), pp. 230–259. ↩The post The eruption of La Soufrière on the West Indian island of St Vincent appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

April 10, 2017

The Bloody Countess: A guest post by Catherine Curzon

Catherine Curzon is a royal historian who writes on all matters 18th century at www.madamegilflurt.com. Her work has been featured on HistoryExtra.com, the official website of BBC History Magazine and in publications such as Explore History, All About History, History of Royals and Jane Austen’s Regency World. She has provided additional research for An Evening with Jane Austen at the V&A and spoken at venues including the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, Lichfield Guildhall, the National Maritime Museum and Dr Johnson’s House. Catherine holds a Master’s degree in Film and when not dodging the furies of the guillotine, she lives in Yorkshire atop a ludicrously steep hill. Read about Catherine’s exciting new book, The Kings of Georgian Britain, below.

You can follow Catherine on social media: Facebook, Twitter, Google Plus, Pinterest and Instagram

Read about Catherine’s exciting new book, The Kings of Georgian Britain, below.

We welcome Catherine, who has graciously provided this story of Clara von Platten, a ruthless player at the Hanoverian court, to our humble abode. Now read on…

The man who would one day reign as King George I and his wife, Sophia Dorothea of Celle, did not get on. They were cousins forced into an arranged marriage that neither wanted and from the first day they met, it was clear that their union would not be happy one. Sophia Dorothea fainted at the sight of her fiancé whilst George sidelined her in favour of his mistresses and, when she complained, attempted to throttle her. It’s hardly surprising, therefore, that Sophia Dorothea fought fire with fire and took a lover, throwing in her lot with Count Philip Christoph von Königsmarck, a Swedish soldier who had been a treasured childhood friend.

Sophie Dorothea Princess-of Hanover by Henry Gascard

The couple exchanged heated love letters and soon they were the talk of the court. Königsmarck was a libertine though, and when he enjoyed a short liaison with Countess Clara von Platen, it was to prove a fatal mistake. Clara, influential, spiteful and feared by her fellow courtiers, was the long-time mistress of George’s father, Ernest Augustus, and she liked nothing so much as trouble. When Königsmarck rejected Clara in favour of Sophia Dorothea, hell truly had no fury like her. She knew better than to show her anger though and instead bided her time, gathering evidence, smiling sweetly at Sophia Dorothea and waiting for the moment to strike.

Philipp Christoph von Königsmarck (unknown artist)

That moment came when Sophia Dorothea and Königsmarck hatched a plan to flee Hanover forever and begin life anew in Wolfenbüttel. On the eve of their flight, Königsmarck received a note purporting to be from his lover that summoned him to her chambers. He obeyed, heading straight to Sophia Dorothea’s rooms and providing whoever had penned the note with the evidence they needed that the two were indeed a couple.

Faced with the proof that his daughter-in-law was betraying her husband, Ernest Augustus agreed that Königsmarck should be arrested and Clara, in the company of four courtiers, went along, supposedly to ensure that he was. In fact, Clara had no intention that Königsmarck would leave the Leineschloss alive.

Clara Elisabeth von Platen

When he left his lover’s rooms, Königsmarck found the door he usually used locked and it was then that the four men attacked him. The count stood no chance against his assailants and was soon subdued. Grievously injured by a blow to the head, he summoned the breath to beg for the life of the princess before losing consciousness. The insensible soldier was dragged into the presence of the countess as he regained his senses. Seeing who had masterminded his fate, he swore a bitter oath. Clara’s reply was to kick Königsmarck hard in the face and it was the last thing he ever knew; moments later, he was dead.

Many versions of Königsmarck’s fate exist, but all involve Clara, and her rumoured involvement in his disappearance followed her to the grave. What became of Königsmarck’s body, however, remains a mystery.

Perhaps Clara and her comrades fell into a panic once the cold truth of their deeds sank in. After all, the elector had given his permission for her to have Königsmarck arrested, not killed, and the future for the courtiers involved might be very bleak indeed if Ernest Augustus discovered what they had done. In Memoirs of Sophia Dorothea, Consort of George I, the corpse is concealed beneath quicklime, whilst Horace Walpole suggested that he was strangled, his body hidden beneath the floorboards of the Leineschloss and still more have suggested that it was hurled into the river Leine or even burned on a bonfire.

We will never know for sure what became of Königsmarck, and the victim and killers took the secret to their respective graves if, indeed, Königsmarck even had a grave to call his own.

Bibliography

Belsham, W. Memoirs of the Kings of Great Britain of the House of Brunswic-Luneburg, Vol I. London: C Dilly, 1793.

Belsham, William. Memoirs of the Reign of George III to the Session of Parliament Ending AD 1793, Vol III. London: GG and J Robinson, 1801.

Benjamin, Lewis Saul. The First George in Hanover and England, Volume I. London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909.

Black, Jeremy. The Hanoverians: The History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon and London, 2007.

Hatton, Ragnhild. George I. London: Thames and Hudson. 1978.

Morand, Paul. The Captive Princess: Sophia Dorothea of Celle. Florida: American Heritage Press, 1972.

Ward, Adolphus William. The Electress Sophia and Hanoverian Succession. London: Longmans, Green and Co, 1909.

Wilkins, William Henry. The Love of an Uncrowned Queen. London: Hutchinson & Co, 1900.

Wilkins, William Henry. A Queen of Tears. London: Longmans, Green & Co, 1904.

Williams, Robert Folkestone. Memoirs of Sophia Dorothea, Consort of George I, Vol I. London: Henry Colburn, 1845.

Williams, Robert Folkestone. Memoirs of Sophia Dorothea, Consort of George I, Vol II. London: Henry Colburn, 1845.

The Kings of Georgian Britain

The Kings of Georgian Britain

For over a century of turmoil, upheaval and scandal, Great Britain was a Georgian land.

From the day the German-speaking George I stepped off the boat from Hanover, to the night that George IV, bloated and diseased, breathed his last at Windsor, the four kings presided over a changing nation.

Kings of Georgian Britain offers a fresh perspective on the lives of the four Georges and the events that shaped their characters and reigns. From love affairs to family feuds, political wrangling and beyond, peer behind the pomp and follow these iconic figures from cradle to grave. After all, being a king isn’t always grand parties and jaw-dropping jewels, and sometimes following in a father’s footsteps can be the hardest job around.

Take a trip back in time to meet the wives, mistresses, friends and foes of the men who shaped the nation, and find out what really went on behind closed palace doors. Whether dodging assassins, marrying for money, digging up their ancestors or sparking domestic disputes that echoed down the generations, the kings of Georgian Britain were never short on drama.

Available from

Pen & Sword, Amazon UK, Amazon US

The post The Bloody Countess: A guest post by Catherine Curzon appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

March 16, 2017

The death of Lavinia Robinson, the Manchester Ophelia

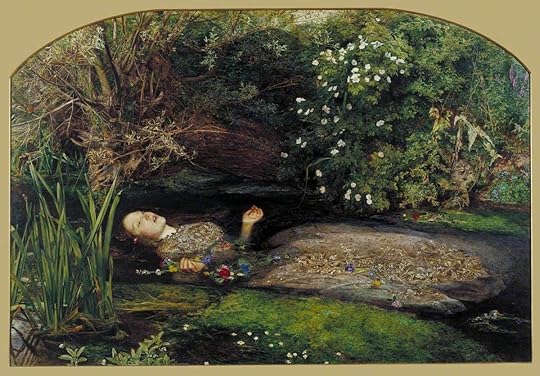

Ophelia by John Everett Millais, painted in 1851-2 © The Tate

The body of 20-year-old Lavinia Robinson was found in the River Irwell on 7 February 1814, over seven weeks after she went missing from her home in Manchester. Had she done away with herself or, as some suspected, was she pushed into the water? And what was the nature of the furious argument she had with her fiancé on the night before she disappeared?

After her parents’ premature deaths, only a few years before her own, Lavinia Robinson and her five sisters supported themselves and their three teenage brothers by converting their home into a seminary. Their resourcefulness enabled them to “keep within the circle of the acquaintance they enjoyed during their father’s life, and to protect the younger branches of the family.” 1

Lavinia was described as “a young lady possessing superior mental accomplishments, with a person lovely as her mind, and of the most fascinating manners,” whose compositions “in prose and in verse, breathe throughout the purest sentiments of religion and virtue, and prove her to have had a warm and affectionate heart, great vivacity, and an uncommon playfulness of disposition.” A paragon, in other words.

John Holroyd worked as an accoucheur at the Lying In Hospital (seen on the left). From Lancashire Illustrated by Thomas Allen.

But perhaps not to her fiancé. On the night Lavinia abruptly left her sister’s house in Bridge Street, she and John Holroyd, who was an accoucheur (man-midwife) at Manchester’s Lying-In Hospital, had argued bitterly at the Robinson family home. One of Lavinia’s brothers overheard part of their quarrel.

Holroyd: All’s ready. All’s prepared.

Lavinia: No, don’t. It’s shameful, you shan’t.

Lavinia’s sister Esther, having a cold, had gone to bed early but at 2am was startled awake as if by a loud noise. She could find nothing amiss and went back to sleep but at 3.45 got up to prepare for the chimney sweeps who were coming early in the morning. She noticed that the front door was unlocked. A short time later she discovered that Lavinia was not in the house.

A note was found:

“With my last dying breath, I attest myself innocent of the crime laid to my charge. God bless you all, I cannot outlive his suspicion.”

A few hours after Lavinia was missed, Esther sent for Holroyd, who lived almost opposite the Robinsons’ house, and asked him if he knew where Lavinia was.

“Good God, is she not here?” he replied. He told Esther that he and Lavinia had had a “very serious quarrel” the previous night and that he had left the house just before 12. Later that day, Lavinia’s brother-in-law James Bentley, a cotton manufacturer married to her sister Frances, called on him.

Bentley: Well, Mr Holroyd, what is this business of Lavinia?

Holroyd: Indeed, Sir, I can’t tell. I am miserable. I can’t tell what to do.

Bentley: Esther mentioned a quarrel you had. I should be glad to know the particulars, and what you fell out about.

Holroyd: Why, Mr Bentley, all delicacy in this business must now be laid aside. I discovered—”.

The exact details of Holroyd’s accusations were not published in the newspaper accounts, but later, at the inquest on Lavinia’s death he submitted a written account, in which he stated that he had accused Lavinia of “a want of chastity.”

“I ventured upon the desperate alternative of being convinced of her virtue before marriage. On Thursday evening, Dec 16th., I discovered with horror that my fears were realised. I immediately taxed her with it, in answer to which, she asserted her innocence with considerable vehemence.”

Bentley said that just now he was more interested in Lavinia’s whereabouts than in Holroyd’s suspicions but Holroyd had nothing more to say, except to remark, rather unnecessarily, that “If I marry her, I shall never live long and be always miserable and unhappy” but he did agree to go to the canal with Bentley to look for her. They had no success.

Lavinia’s family reported her missing at the police office and advertised a reward of 30 guineas for her return “live or dead.” During their agonising wait, in the middle of a particularly cold winter, the River Irwell froze over. Their hopes may have been raised when a young woman arrived in distress at the home of a magistrate in Thatcham. 2 He suspected that she might be Lavinia Robinson and, when questioned, she said she was – but it turned out that she was lying.

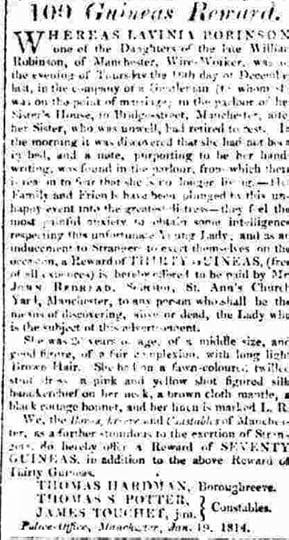

The Robinsons’ advertisement of a reward for the discover of Lavinia Manchester Mercury, Tuesday 1 February 1814.

Finally, at the beginning of February, the ice on the Irwell began to break up and on 7th Mr Goodier, a millworker, came across Lavinia’s body on a sandbank at Barton. She was still in the fawn-coloured gown she was wearing on the night she left her home, a pink and yellow silk handkerchief around her neck. She had lost a shoe, her mantle and a black beaver hat.

The next day a two-day inquest opened at the Star Inn, under the Coroner Nathaniel Milne. One of Lavinia’s brothers described hearing snatches of the argument between the lovers, her sister Esther spoke of being woken suddenly in the night, and James Bentley detailed his dealings with Holroyd after Lavinia disappeared. Perhaps the most sensational evidence, given what happened to Holroyd afterwards, was from Mr Barlow, who swore he saw a couple matching the description of Holroyd and Lavinia arguing near the western wall of the New Bailey, a stone’s throw from Bridge Street, and that the man struck the woman to the ground. Barlow heard the woman say, “Believe me – but you won’t. I don’t care if you murder me, if you’ll only believe me,” to which the man replied, “Who was it? If you don’t tell me, I’ll never forgive you.”

Mr Ainsworth, the surgeon who performed the autopsy on Lavinia’s body, said her right temple had a crack of two inches, possibly the result of crushing in the ice, and that there was bruising around the neck. Furthermore, there was “nothing to shake their conviction that she had passed a strictly unimpeachable and virtuous course of life.” That is, she was a virgin, and Holroyd’s suspicions were groundless.

Holroyd’s reputation was in tatters, not helped by the fact that two of Lavinia’s sisters and one of her brothers said on oath that they did not believe that the suicide note was in her handwriting. A friend of Holroyd’s said he did not think it was his either, but the damage was done.

Holroyd, who declined to give evidence in person but submitted a written statement, left the court before the verdict was returned.

“That she said Lavinia Robinson was FOUND DROWNED in the river Irwell… but how or by what means she came into the water of the said river no evidence thereof appears to the said jurors.”

That is, an open verdict. There was not enough evidence for a murder charge, nor for the certainty that Lavinia had committed suicide.

After Lavinia’s body was returned to her home, local feeling against Holroyd intensified. Crowds gathered around his residence and grafitti was scrawled on the door and walls. Stones were thrown at the windows. “A kind of fury seemed to hang on the minds of the lower classes of society, which threatened most serious consequences to Mr. Holroyd,” reported Bell’s Weekly Messenger. His employers, the trustees of the Lying-In Hospital, were also disgusted at his behaviour, and sacked him. Fearful for his safety, Holroyd was forced to seek protection at the police office and later, on their advice, left town.

Lavinia’s funeral, attended by hundreds and at which her siblings were said to have been “overwhelmed” with grief, took place on Tuesday 8 February at St John’s Church, Manchester. 3 Books of subscription were opened at various places around the city to raise money to defray the expenses of the search and reward. The reward itself became a matter of contention. The Manchester Mercury expressed surprise that “something that occurred when scores of people were employed to break up the ice and which caused him [Goodier, who had found Lavinia’s body] no personal expense could feel that he deserves it.” Goodier gave the 30 guineas back to Lavinia’s sisters, but kept the 70 put up by the city authorities.

In the following month there were rumours that Holroyd had committed suicide at Stafford, but this was a case of mistaken identity, and he was later said to be working as surgeon in his native village of Middlestown near Thornhill in Yorkshire.

The inscription on her gravestone included the following lines:

More lasting than in lines of art

Thy spotless character’s imprest;

Thy worth engraved on every heart,

Thy loss bewail’d in every breast. 4

In time, Lavinia became mythologised as the Manchester Ophelia.

Notes:

Sources for this story are Manchester Mercury, 15 February 1814; Leeds Mercury, 19 February 1814; Bury and Norwich Post, 2 March 1814; London Courier and Evening Gazette, 19 February 1814; Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 27 February 1814; Saunders’s News-Letter, 7 March 1814; Lancaster Gazette, 23 April 1814. ↩It is unclear from the report in the Kentish Weekly Post, 8 February 1814, whether this is Thatcham Green, Staffordshire, 40 miles from Manchester, or Thatcham, Berkshire (170 miles). ↩Lavinia’s parents, William (a wire-worker) and Frances, were Dissenters, members of the the Mosley Street Independent Chapel in Manchester. Perhaps Lavinia moved across to the Church of England at the suggestion of her fiancé. Bentley was also an Anglican. ↩Quoted in Procter, R. W. (1880). Memorials of Bygone Manchester with Glimpses of the Environs. Manchester: Palmer and Howe. ↩The post The death of Lavinia Robinson, the Manchester Ophelia appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

March 12, 2017

Catherine Tylney-Long: A quadruple-barrelled surname was never going to work

A guest post by Mike Rendell, whose recently published In Bed with the Georgians: Sex, Scandal and Satire in the 18th Century (Pen & Sword), is a handsomely produced large format paperback, packed with colour illustrations and fascinating information. I’ll be reviewing it on the site soon.

A guest post by Mike Rendell, whose recently published In Bed with the Georgians: Sex, Scandal and Satire in the 18th Century (Pen & Sword), is a handsomely produced large format paperback, packed with colour illustrations and fascinating information. I’ll be reviewing it on the site soon.

Mike’s blog grew out the work he did for his first book, The Journal of a Georgian Gentleman, which drew on the huge volume of 18th-century papers he inherited from his 4 x great-grandfather, who had a haberdashery shop on London Bridge and later retired to the Cotswolds to become a farmer.

Follow Mike on Twitter @GeorgianGent

So, without further delay, here is Mike on the rollercoaster fortunes of the heiress Catherine Tylney-Long, who made a catastrophic decision which affected her whole life thereafter.

One of the things which amazed me when doing the research for In Bed with the Georgians was the incredible wealth – and naïvety – of some of the 18th-century heiresses. Catherine Tylney-Long was a case in point.

Catherine Tylney-Long and William Pole-Tylney-Long-Wellesley

She first came to my attention because when this double-barrelled young lady married a scion of the famous Anglo-Irish Wellesley family, and her husband adopted her surname in addition to his own, becoming known as the Rt. Hon. William Pole-Tylney-Long-Wellesley.

A handy little moniker if ever there was one! At 21, Catherine was attractive, lively and petite, but above all, she was loaded. She had inherited a vast fortune at the age of 16, estimated at giving her an income of £40,000 a year – and had spent five years trying to avoid fortune hunters. She then made the biggest mistake of her life, by marrying a man who would turn out to be one of the most profligate and odious men of the century. He was a nephew of the Duke of Wellington, and was reputed to have been turned down on the six previous occasions when he had proposed marriage to her.

The Duke of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence

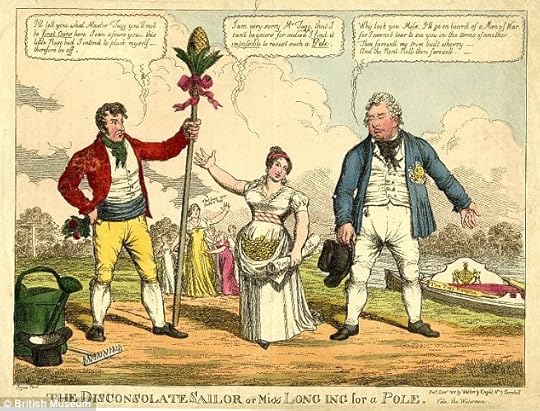

Unfortunately for her, her resilience failed her and she finally consented at the seventh time of asking. She had other suitors – notably the Duke of Clarence (later to become William IV) and cartoonists revelled in the Duke’s embarrassment at being spurned in favour of the Irish ne’er-do-well.

Caricature of the Regent and William – courtesy of the British Museum

The newspapers had a field day when the marriage took place in Piccadilly on 14 March 1812, reporting that after the ceremony ‘the happy couple retired by the southern gate… where a new and magnificent equipage was waiting to receive them. It was a singularly elegant chariot, painted bright yellow, and highly emblazoned, and drawn by four beautiful Arabian grey horses, attended by two postilions in brown jackets, with superb emblazoned badges in gold, emblematic of the united arms of the Wellesley and Tylney families. The newly married pair drove off, with great speed, for Blackheath, intending to pass the night at the tasteful chateau belonging to the bridegroom’s father, and from thence proceed to Wanstead House, in Essex, on the following day.’

Newspapers then, as now, seemed to concentrate as much on what everything cost as on what the bride wore. The same report advised that ‘The dress… consisted of a robe of real Brussels point lace… placed over white satin. Her head was ornamented with a cottage bonnet of the same material, being Brussels lace with two ostrich feathers. She likewise wore a deep lace veil and a white satin pelisse trimmed with swansdown. The dress cost seven hundred guineas, the bonnet one hundred and fifty, and the veil two hundred, and she wore a necklace which cost £25,000.’

If the day was the happiest of her life, things started to go downhill with ominous speed. No sooner had he had got his hands on his wife’s money than William spent it with extravagant zeal. There were ostentatious parties at the family home at Wanstead which cost a fortune – and from which Catherine was excluded. And then there was the constant and unbelievably reckless gambling, on top of which vast sums were laid out in bribes to get William elected to Parliament. It was also decided to refurbish Wanstead, a magnificent Palladian mansion, at an estimated cost of £360,000. The papers reported that the couple were ‘fitting up Wanstead House in a style of magnificence exceeding even Carlton House.’

Assembly at Wanstead House by Hogarth

In the course of a decade Catherine had to suffer in silence as her husband spent her entire fortune, forcing the couple to flee abroad to avoid their creditors – humiliating for a woman who had been given the accolade of being the richest woman in the land just ten years earlier. Worse humiliation followed when they reached Italy – William openly conducted an affair with one Helena Bligh, the wife of a captain of the Coldstream Guards. Catherine tried, unsuccessfully, to buy off her rival but, realising the futility of the exercise returned to Britain with her three children, determined to obtain a legal separation from her husband. Meanwhile Wanstead house had been put up for auction – the entire contents were sold but the house failed to attract a buyer and had to be sold ‘one stone at a time.’ The proceeds amounted to a miserable £10,000. William accepted no blame at all for the extravagance which cost his wife her entire fortune, always claiming that it was ‘someone else’s fault.’

Her health broken, Catherine died at the age of 35, entrusting the care of her children to her two sisters. Her death may well have been attributable to a nasty dose of the clap which her husband gave her, as there were indications that she developed an inflammation of the bowels caused by a venereal disease. A letter to one of her sisters hints at this. Her death triggered a series of legal battles in which William tried to recover legal custody of his children.

Astonishingly for the time (when, as the natural father, he would always expect to be supported by the courts) his case in Chancery failed – over and over again. Each case brought further salacious details of William’s private life into the public domain. In particular he openly lived with Helena, his mistress, and when she came to live in London her husband Thomas Bligh decided that enough was enough, and he brought a suit of ‘crim.con.’ against William. The public revelled in the gossip, and cheered tumultuously when the court awarded damages of £6,000 to the cuckolded husband. William retaliated by publishing accounts which sought to defend his adulterous behaviour, and heaping accusations of immorality on to the two Long sisters who had been given legal custody of the children.

In November 1828 William married Helena, who by then had, in the minds of the general public, been exposed as a whore. It was a disastrous second marriage, and before long she was reduced to claiming poor relief from the parish. William eked out the last 30 years of his life in considerable poverty, dying in July 1857 while eating a boiled egg. The Morning Chronicle published an obituary which described him as ‘A spendthrift, a profligate, and gambler in his youth, he became a debauchée in his manhood… Redeemed by no single virtue, adorned by no single grace, his life has gone out even without a flicker of repentance…’

It has to be said: the boiled egg did the world a favour!

The post Catherine Tylney-Long: A quadruple-barrelled surname was never going to work appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

February 25, 2017

The rape of Hannah Whitehorn (1819)

For my forthcoming book Unfortunate Wretches, about women hanged in the early 19th century, I have been looking at the relationships between servants and employers. Quite separately, for my next project, I am also researching issues around rape. And, of course, I am always interested in how teenagers, particularly female teenagers, are disparaged and disbelieved.

As was so often the case, the voice of the victim in this story was – and is – almost completely unheard. Her allegations were reported second hand, and events were related, in court and in print, entirely through the words of men, most of whom were both unsympathetic and biased against her. Nevertheless, the story gives some comfort. One man, at least, appeared to understand the situation Hannah Whitehorn found herself in shortly after she entered the household of Captain Samuel Mills.

On Friday 13 August 1819, 15-year-old Hannah Whitehorn, a live-in servant for Captain Samuel Mills (or Milne or Milnes) in Smith Street, Chelsea, was dismissed by her master and sent home to her parents, who lived in Charing Cross. Later that evening, Mills left the house and spent the night and much of the following morning enjoying himself at Vauxhall Gardens on the south side of the Thames.

Smith Street, London

Hannah, who had only the day before written to her mother in distress, had an appalling tale to tell about her experiences at the hands of Captain Mills. At midnight on the day after she arrived at Mills’ house, the Captain had “pulled her into the parlour and gave her some noyeau [nut liqueur], which made her sick and obliged her to go into the garden. After she came in, he again called her into the parlour, gave her the candle, and pushed her up stairs, notwithstanding all the resistance, she could make. He prevented her from going into her own room, and pulled her into his.” Then he raped her.

Diligence and Dissipation: The Modest Girl rejects the Illicit Addresses of her Master (1797). After James Northcote. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund.

Mr. Whitehorn, who was later described as “almost deranged” with grief at the treatment of his daughter, and Mrs. Whitehorn, who was “lame and helpless”, went straight to Mr. Price, who had found Hannah the job with Mills. Price immediately dispatched a letter to the Captain informing him of Hannah’s allegations. Mills, a 48-year-old former Army captain who described himself as a “magistrate and housekeeper [householder]”, found it waiting for him when he returned from Vauxhall. Incensed, he wrote to Price to deny Hannah’s story and on the Monday presented himself at Mr. Price’s abode to discuss the matter. There Price told him that Hannah was now also claiming that he had given her “a certain complaint” (sexually transmitted disease). At this he went to see the famous surgeon and anatomist Mr Astley Cooper, who gave him a clean bill of health.

What had been going on? And how did Hannah contract such a disease if not from him?

At Price’s house, Mills demanded a meeting with Hannah’s mother, who arrived with a police constable. Mills was arrested and taken before a magistrate; Hannah related her story and the Captain was committed to prison. Hannah was examined by medical men, the well known George Fincham of Spring Gardens, and Hugh Campbell, who described himself as a former lieutenant (whether in the army or navy is not clear), and a non-practising medic. Campbell found the girl in “a wretched condition”, was instantly struck by her plight and decided to do all he could to support her.

On 15 September Mills’s case came up at the Old Bailey, where he was defended by top barristers John Adolphus and John Barry. Saunders’s News-letter 1 described Mills in court as “a middle-aged man [who] was fashionably dressed in black.” Under an arduous cross-examination Hannah gave evidence concerning her life in the Mills household. She admitted that she had sat talking with her master in the parlour each night, sometimes to 12midnight or later, but she faltered so much in her replies (“glaringly inconsistent”) that the judge, Robert Graham, asked her counsel whether the case should be pursued. It transpired that she may have had a disease, but perhaps not a sexually transmitted one as the diagnosis was not certain. Unsurprisingly, the jury conferred briefly and acquitted Mills. 2

At this point, the court became chaotic. As the verdict was being recorded, Hugh Campbell, the medic who had examined Hannah, furious that Mills was getting away with his crime, leapt up and from the witness box declared that he had come to do justice to Hannah’s cause. Hannah had a good character, he said, and had arrived at Mills’s house as a virgin but emerged “polluted.” Not a word was said about the pistols lying on the table in the parlour, he said (the inference was that they threatened Hannah into compliance). Hannah had been treated shamefully and cruelly.

“Who are you, or what are you? Are you a professional man?,” asked the judge.

“I have been in the service of my country: I have studied and I understand surgery and medicine, though I don’t practise as a professional man,” replied Campbell and continued his declamations, despite the objections of Adolphus and Barry. He was dragged from the witness box and only reluctantly left the court itself, still expounding on the injustice of the verdict.

His campaign did not stop there. First he wrote to the judge. Their correspondence was published in the newspapers. 3 Next he published the correspondence in a pamphlet 4 which he had prefaced with the following motto:

“——multi

Committunt eadem diverso crimina fato;

Ille crucem pretium sceleris tulit hic diadema” —Juvenal

“Ev’ry age relates that equal crimes unequal fate have found;

While one villain swings, another villain’s crown’d.”

Captain Mills, perhaps encouraged by his legal advisors, now planned to rehabilitate his damaged reputation by pursuing his enemies. He launched a prosecution of Hannah for perjury in her account 5 and sued Campbell for libelling him in the pamphlet.

Sir Robert Graham (1744-1836) by William Daniell, after George Dance, soft-ground etching, published 1854?

Hannah’s case came up in the Court of King’s Bench at Westminster Hall in May 1820. This time, Mills employed James Scarlett, one of the most successful and expensive lawyers around, to prosecute. It did not go well – for Mills. In the witness box he claimed that he had dismissed Hannah because he was disgusted by her personal offensiveness (“extreme dirtiness”) 6 and said that he dined out constantly, during which time she was free to leave the house herself, the imputation being that she must have picked up a disease on those occasions.

However, under cross-examination he could not adequately explain why so many domestic servants had left his employ (eight women in five months, one of them very suddenly) nor why two of them had lodged complaints against him at the police office in Queens Square (although none of them alleged rape). While it became clear that Hannah had told no one of the attacks on her for the 16 days she lived in the household, an 11-year-old fellow servant remembered that she had been ill the day before she was sacked and had written to her mother. Hannah’s friends stood up for her, including two respectable gentlemen and the Rev. John Day, whose day-school in Orange Court, Leicester Square, Hannah had attended. Despite the direction of the Lord Chief Justice, the jury declined to find Hannah guilty and the case was dismissed.

The following month Hugh Campbell appeared in the same court to answer charges of libel brought by Mills, who once more employed the services of James Scarlett. Campbell, defending himself, presented an eccentric argument. His motivation was to encourage “purity and virtuous feeling among women in the inferior walks of society” he declared, and invoked “a Royal proclamation for the encouragement of religion and morality: in the spirit of which proclamation he contended he had acted, and upon the letter of which he was entitled to reward rather than to punishment.” He declared himself confident that the jury would acquit him – which they did.

The Gourmand, by Thomas Rowlandson. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

At this point, our protagonists – Hannah, a girl from a humble family who had courageously alleged that her employer had attacked her and endured scepticism, denigration and insult, and Campbell, her condescending but valiant defender – fade into history 7. Not so Captain Mills. He pops up again ten years later, in circumstances that leave many questions while also indicating that his behaviour towards Hannah was part of a pattern.

In 1830, Captain Mills described to a magistrate at Marlborough Street how he had noticed people lurking outside his home in Down Street, Piccadilly. “From circumstances which had already occurred,” he knew they were there for him. He had managed to avoid these people until one morning, while out in his tilbury, 8 he was soundly horsewhipped by Lieutenant William Burt, who only stopped when a passing police officer intervened and arrested him.

In the magistrates court, Burt did not bother to deny the charge, and his manner was triumphant rather than repentant. When Mills claimed that the only reason he did not challenge him to a duel was that Burt was not a true gentleman, having been excluded from the United Service Club, he announced that he “considered himself fully respectable, at least in every sense of the term, as Captain Mills, although he could not boast of having so much notoriety in Bow-street police-reports as the Captain had.”

I have transcribed the newspaper reports of this story.

Notes:

22 September 1819. ↩OBPO t18190915-70. As Mills was acquitted, details of the case were not given. ↩Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 25 September 1819. ↩“A Letter to Mr. Justice Graham” cited in Evening Mail, 26 June 1820. ↩There are parallels here with the case of Maria Glenn, whose rollercoaster ride through the courts of England landed her in a similar situation. ↩Evening Mail, 31 May 1820. ↩If you can help me with identifying what happened to them please leave a comment. ↩An open, two-wheeled carriage. ↩The post The rape of Hannah Whitehorn (1819) appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

February 6, 2017

An altercation in Taunton between Tom Woodforde and Don Whiskerandos

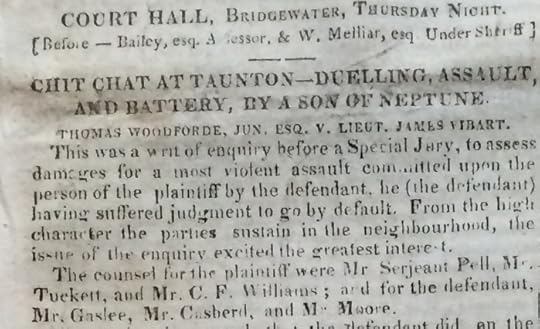

It is well known that Master Vibart, Don Whiskerandos, has been seen coming out the house of — between three and four in the morning.”

After Tom Woodforde uttered those words loudly in Savage’s Reading Room in Taunton, Somerset in front of a group of other gentlemen, a report found its way back to James Vibart, a half-pay Lieutenant from a prominent family in the town. Outraged that Woodforde had traduced the character of a respectable married lady and, as his lawyer later put it, “attempted to destroy the honour and happiness of a whole family,” Vibart called on him one evening, bludgeon in hand.

A violent altercation ensued as the two men, both now armed with sticks (Woodforde must have grabbed one or been given it), beat each other all the way up Taunton high street, attracting a crowd of spectators. It must have been excellent entertainment for the ordinary townsfolk: seemingly respectable gentlemen did not often fight in public screaming “Murderer!” and “Midnight assassin!” at each other.

Hammet Street, Taunton via rareoldprints.com. The high street can be seen at the end of Hammet Street.

John Fitch saw Woodforde on his hands and knees outside his house.

“Curse your soul, you scoundrel, get up!” shouted Vibart, and, as Woodforde did so, brought his bludgeon down on his arm.

“What do you mean to do?” asked Woodforde.

“You rascal, I will tell you what I will do for you, by and by.”

“You mean to kill me with that stick,” said Woodforde.

“No, it’s just to give you a drubbing!” replied Vibart.

Woodforde received blows on his head, head, face, back and body. Two hours of fighting left him covered in blood, but he managed to get home. His arm was in a sling for a week afterwards.

“A great deal of abusive language passed on both sides,” reported The Observer 2 coolly four months later when Woodforde brought a case against Vibart at Bridgwater’s Court Hall, 12 miles from Taunton, heard by Judge John Bailey. Vibart’s lawyers did not dispute that he was at fault for the assault but tried to mitigate damages awarded against him by detailing the outrageous slur Woodforde had cast. In the end, the jury awarded him a hundred pounds.

For the prosecution (representing Woodforde)

Albert Pell

George Lowman Tuckett

Charles Frederick Williams

For the defence (representing James Vibart)

Stephen Gaselee

Robert Casberd

Abraham Moore

The Observer, 17 Augusut 1817, page 3

Abraham Moore (1766-1822) was from a Devon family of clergymen. Having been called to the bar, he went on the Western Circuit, worked as a special pleader and held other legal offices in Kent and London. At the general election of 1820 he was returned as as member for Shaftesbury, his patron being the first Earl Grosvenor. At the beginning of August 1821, Moore fled to America having, as Grosvenor put it, “turned one of the greatest scoundrels in existence” by leaving his patron in debt for the “frightful amount” of £80,000. He and his wife died of yellow fever in New York in late 1822, leaving six young sons.

Robert Matthew Casberd (1772-1842) was the son of a Bristol doctor. Educated at St John’s College, Oxford, he became MP for Milbourne Port, a “Scot and Lot” constituency of about a hundred voters, from 1812 to 1820.

Albert Pell graduated from St John’s College (he was a contemporary of Tuckett’s). He had arisen from humble beginnings in the East End of London and was known for his work ethic and intelligence. As a young barrister on the Western Circuit, unable to afford transport between Assize towns, he had opted instead to walk. He was a serjeant-at-law.

Stephen Gaselee (1762–1839), son of a Portsmouth surgeon, was known for his encyclopaedic knowledge of the law. Like Tuckett, he had trained under the acerbic Sir Vicary Gibbs. He was appointed KC in 1819 and was later made a judge in the Court of Common Pleas.

The case will be of interest to those who have read my book The Disappearance of Maria Glenn, as it featured so many of the people who played a major role in her story. Maria’s uncle, George Lowman Tuckett, was on the prosecution team. A year or so after this case, he and Woodforde were sworn enemies, with Woodforde actively trying to destroy Tuckett’s niece Maria’s reputation. In fact, all six lawyers in the Woodforde v Vibart case were involved in legal actions concerning Maria.

In August 1818 at Dorchester Pell, Williams, Moore and Gaselee represented Tuckett in his case against the Bowditch family, and Casberd, Moore and two others defended them. In addition, John Bailey was on a panel of four judges who later handed down a decision on whether the Bowditches should be retried.

My research into Tom Woodforde revealed him as an unscrupulous and aggressive operator, his support of liberal and progressive causes notwithstanding. It is interesting that his barrister Charles Frederick Williams described him as having “filled judicial and other high situations” in India. In fact he was sacked by the East India Company for disrespectful behaviour at a Muslim funeral, something his lawyers and the people of Taunton were probably unaware of. The Taunton Courier did not carry this story – its editor was a friend of Tom Woodforde’s father – and I have not found it anywhere else so far.

Notes:

The name of the woman involved is unknown ↩17 August 1817 ↩The post An altercation in Taunton between Tom Woodforde and Don Whiskerandos appeared first on Naomi Clifford.