Naomi Clifford's Blog, page 4

July 10, 2019

Mary Linwood and the art of needle-painting

The ‘gifted and remarkable’ Mary Linwood. From the London Illustrated News, 22 March 1845.

Mary Linwood 1755–1845 (age 90) needlework artist and composer.Baptised at St Martin’s, Birmingham 18 July 1755.

The picture collection, steadily added to until Miss Linwood lost her eyesight when she was about seventy-five, eventually consisted of over sixty reproductions, in addition to a self-portrait she made when she was nineteen. … The catalogue appended to each title an appropriate excerpt from poetry, mostly from favorite eighteenth-century authors like Thomson.”–Altick, Richard D. The shows of London. Cambridge, Mass. : Belknap Press, 1978, p. 401.

Item 57 in the catalog is Linwood’s Tygress, after a painting by George Stubbs. The original needlework picture is now in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, Department of Rare Books and Manuscripts (see link provided herewith). Accompanying the catalog entry is an excerpt of verse from Milton’s Paradise Lost: “Then as a tiger, who by chance hath spy’d In some purlieu two gentle fawns at play, Strait couches close, then rising changes oft’ His couchant watch, as one who chose his ground, Whence rushing he might surest seize them both Griped in each paw.” This is followed by two lines from Thomson’s Seasons: “The Tyger darting fierce Impetuous on the prey his glance has doom’d.”

http://discover.odai.yale.edu/ydc/Rec...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Li...

https://www.meg-andrews.com/item-details/mary-linwood/6374

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=P...

http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/L...

Tiger: https://collections.britishart.yale.e...

https://www.thefreelibrary.com/How+a+...

Napoleon

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O7...

The technique of this portrait is known as needlepainting, a type of embroidery, in which oils or other paintings were faithfully copied, with the brush strokes rendered by stitches worked in crewel wool. Needlepainting was practised in the second half of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Mary Linwood (1756-1845) was the most renowned practitioner, through the exhibitions of her work held in London.

People & Places

Mary Linwood lived in Leicester, helping her mother to run, and eventually taking over, a boarding school for young ladies. In 1776 she exhibited needlework pictures at the Society of Artists in London. In 1787 she was introduced to Queen Charlotte (1744-1818), and this encouraged her to exhibit some of her pictures at the Pantheon, Oxford Street. In 1798 she opened an exhibition at the Hanover Square Concert Rooms in London, which toured to Scotland and Ireland. The collection, increased to 64 pieces, returned to London to be shown at Mary Linwood’s own gallery in Leicester Square, where it remained on display until Linwood’s death in 1845. Contemporary accounts suggest the gallery’s presentation was very elaborate, the main hall hung with ‘scarlet cloth, satin and silver’. The copy of a painting Lady Jane Grey Visited by the Abbot and Keeper of the Throne at Night was shown in a prison cell at the end of a dark passage. (Lady Jane Grey, the ‘nine days Queen’, was executed by Mary I for treason in 1554.) This portrait of Napoleon was displayed in the Leicester Square Gallery as number 52, in the ‘Gothic Room’.

Lady Mary Lowther, 1740–1824. Self-portrait. 1765. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Lowell Libson Ltd.

The post Mary Linwood and the art of needle-painting appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

June 30, 2019

Wild swimming in the Thames – Georgian style

In the summer of 1807 Byron, then aged 19, boasted of swimming from Lambeth Bridge to London Bridge. In a letter to his friend Elizabeth Pigot, he wrote: “Last week I swam from Lambeth through the 2 Bridges Westminster & Blackfriars, a distance including the different turns & tacks made on the way, of 3 miles!! You see I am in excellent training in case of a squall at Sea.”

In 1828 Byron’s frenemy Leigh Hunt remembered the first time he encountered Byron:

The first time I saw Lord Byron, he was rehearsing the part of Leander, under the auspices of Mr. Jackson the prize-fighter. It was in the river Thames, before he went to Greece. I had been bathing, and was standing on the floating machine adjusting my clothes, when I noticed a respectable-looking manly person, who was eyeing something at a distance. This was Mr. Jackson waiting for his pupil. The latter was swimming with somebody for a wager. I forget what his tutor said of him; but he spoke in terms of praise. I saw nothing in Lord Byron at that time […] so, contenting myself with seeing his Lordship’s head bob up and down in the water, like a buoy, I came away. Leigh Hunt, Lord Byron and Some of His Contemporaries: Recollections of the Author’s Life and of His Visit to Italy, 2 vols (London: Henry Colburn, 1828), 2, p. 1.1

Byron, who had a deformed foot, loved swimming, whether in the sea or river, as it was both an opportunity to demonstrate his physical strength and a symbol of personal freedom. He cannot have minded the filth he encountered in the water, which was a dumping ground for the many dwellings and manufactories on the banks.

In the 17th century swimming was popular with the noblemen whose palaces fronted the Thames and by the 18th was considered a sport, but for upper-class men only. It was not anything like bathing and was definitely not for ladies. Working men did not generally swim. They rarely had time for leisure activities, and those whose occupations were river-based saw the Thames primarily as a highway for transporting people or goods from one place to another.

With that in mind (as well as the recent warning to people considering wild swimming), I searched out these three Georgian-era images of men swimming in the Thames.

David Cox (1783–1859, Westminster From Lambeth (1813). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

David Cox’s watercolour Westminster From Lambeth features naked male swimmers on the Lambeth side of the Thames, attended by boatmen. The view shows the double spires of Westminster Abbey in the background, with St Margaret’s Church to the left and Westminster Hall in front. Cox’s artistic career was initially in the commercial sector: he was apprenticed to a miniature painter and later employed as a scene-painter at Astley’s Theatre (which was close to the spot where Cox sat to paint – on the walkway behind St Thomas’s Hospital), but by his mid-20s he was travelling around England and Wales painting watercolour landscapes. From 1805 he was exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy and hired himself out as a drawing-master to the aristocracy, eventually becoming a grand old man of the watercolour scene.

Samuel Scott (17701/2-1775). Arches of Westminster Bridge (c 1750). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Over sixty years before David Cox painted this, Samuel Scott chose to depict a couple of muscular swimmers in the water near a pier of Westminster Bridge. In the distance, approximately where Gordon’s Wine Bar in Villiers Street is now, stands the 21-metre-tall octagonal York Buildings Water Tower, which was built in the late 17th century (it was gone by the time Victoria Embankment was redeveloped in the 1860s).2 Scott, who started his career as a maritime artist painting ships, was sometimes called the ‘English Canaletto’; he often painted river scenes, especially Westminster Bridge.

View on the River Thames; illustration to the Picturesque Tour. 1796 Etching and aquatint. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

This print showing Somerset House on the left and St Paul’s in the background to the right of centre, with Blackfrairs Bridge on the right, has naked figures swimming off barges moored in foreground. As in the previous image, public nakedness – at least in males – seems to have been accepted.

For lively posts on Regency swimwear and bathing machines visit my friends Sarah Murden and Joanne Major at All Things Georgian blog.

The post Wild swimming in the Thames – Georgian style appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

April 27, 2019

No justice: The death of Isabella Young at Herrington, County Durham

Execution is, of course, irrevocable. Mistakes cannot be corrected. In the conviction in 1819 of two men for the murder of Isabella Young four years previously we see an example of how easy it was to arrive at the wrong verdict and what could be done about this afterwards.

The person who killed 20-year-old Isabella Young on the night of 28 August 1815 must have been armed with something heavy such as a hammer or poker. She was found with several deep head wounds, her skull was fractured and her jaw broken in several places.

Isabella had only been employed at Herrington Hall, which was situated close to the Sunderland road in East Herrington, County Durham, for four days before her 65-year-old mistress Miss Jane Smith left home to collect farm rents from her estates. Miss Smith planned to be away for 10 days, during which time Isabella was sent to lodge elsewhere in order to save her employer money on heating and lighting, but she was instructed to go back to sleep at Herrington Hall the night before her mistress was due to return.1

A Maid, Print made by James Bretherton, after Henry William Bunbury. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Every day while her mistress was away, Isabella came back the house to clean, sometimes alongside Hannah Crinson, an 80-year-old widow and domestic servant who had previously worked for Miss Smith but who was now retired. On Tuesday 22 August, they were in the kitchen cleaning the pewter when a tall, shabbily dressed man with a long pale face came to the door claiming that he wanted to talk to Miss Smith about renting one of her collieries. He made himself at home at the kitchen table and expounded on his plans, much to their surprise and annoyance, and after an hour went on his way. Although he seemed sober enough, they thought he was shifty.

On the evening before Miss Smith was expected home, Monday 28 August, Isabella told Elizabeth Clark, the wife of a waggoner in the village, that she had heard noises at the door, as if someone was trying to get in, and she asked Elizabeth’s daughter Ann Howe, who lived 50 yards from Herrington Hall, to come back to stay with her overnight. Ann agreed only to walk back to the house with Isabella, but waited outside while Isabella locked the door from the inside and called out from the upstairs window that she was safe in her room. This was at about 10pm.

Map of County Durham by Thomas Kitchin, c. 1750 (detail). Courtesy of Beineke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

At two in the morning, John Stonehouse, the village blacksmith woke up and lay in bed for ten or 15 minutes gazing the strange lights dancing on the ceiling. Belatedly he realised that there was a fire somewhere. When he looked out of the window he saw Herrington Hall blazing. Throwing on his clothes, he ran downstairs, raised the alarm in the village and raced towards Miss Smith’s house along with his brother James and a fellow blacksmith, Joseph Turnbull.

At the house they called out to Isabella, but there was no answer. When they tried the front door, which was closed but not locked, they saw her lying face down in the passage to the kitchen wearing only her shift and clutching her flannel petticoat in her left hand. John Ramsay, the village cartwright, managed to grab her arms, pull her out across the road and sit her up, but it was to no avail. She was dead. Someone was sent to inform Miss Smith.

After dawn broke, surgeon John Croudace was fetched from Bishopwearmouth to examine the body. Isabella had clearly been the victim of an astonishingly brutal attack. Her head was a bloody mess. There were several deep head wounds, her skull was fractured and her jaw broken in several places.2 She had no burns and she was not with child. When Croudace had finished, Isabella’s body was lifted into an old wooden box, carried out to an outhouse in the back yard and covered with a horse cloth. 3 The Durham coroner, Samuel Castle, was sent for. People in the village talked about seeing three strangers hanging about the village in the days before the fire, and concluded that they must have been responsible.

The shock for Miss Smith on her return must have been intense. As there was no source of water nearby, the fire had burned on until only the walls of the house remained. Everything, including all her valuables, legal documents, deeds, securities, and cash, which she stored in her bedroom above the kitchen, had been stolen by the intruder who had killed Isabella or had been destroyed in the fire. An inquest held in the village.

It was abundantly clear that the property, and not the fate of poor Isabella, was what was most important to Miss Smith. She began sifting the hot cinders looking for old nails, hoops, hinges, bolts and locks, anything salvageable, and a rumour went around that rather than pay for lodgings Miss Smith was sleeping in the same box that had been used to store Isabella’s corpse, which was now buried at St Michael’s Church in Houghton-le-Spring.

Robinson, W. R., St Michael and All Angels, Houghton-le-Spring.

After a few days, probably at the insistence of her solicitor Mr Gregson, Miss Smith offered a reward 100 guineas (£104). The authorities also promised to extend a ‘Prince Regent’s pardon’ to anyone who was tangentially involved (as long as they were definitely not involved in the murder or the arson), if they identified the perpetrators, and an additional cash reward was advertised by the Bow Street Runners, bring the total to £200. The Home Office ordered a Bow Street officer to go up to County Durham to investigate.4 Handbills were distributed and posters pasted up. The murder had shocked and terrified the county, if not the entire country. ‘A Citizen’ wrote to the editor of the Durham County Advertiser pleading for a coherent police force who could rid the area of ‘rogues, vagrants, and other disorderly persons.’5

Miss Smith posted a 100 guinea reward for information about the fire at Herrington Hall and the murder of Isabella Young. Tyne Mercury, 12 September 1815. © The British Library Board

Who was Miss Smith? An only child related to the Smythes of Esh, and distantly to George IV’s mistress Maria Fitzherbert), Miss Smith was from an old Catholic family and had inherited Herrington Hall and large and valuable estates, including farms and collieries, from her father Mathew. Newspaper accounts of the murder made no bones about her character, stating baldly that she was well known to be extremely wealthy but also miserly. In fact, she was parsimonious to the point of criminality. In 1786, aged about 35, she and her father Mathew became involved in an argument with the keeper of the turnpike gate at West Rainton. They claimed they did not need to pay the toll, having already passed through it that same morning, and rode off. The gatekeeper sued them because he knew they were lying, and won. The Smiths were fined £10 each. There were other incidents of a similar nature.

A View of Murton Colliery near Seaham, County Durham, John Wilson Carmichael (1843). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

After the fire, Miss Smith decamped to lodgings at Bishopwearmouth where her behaviour attracted attention and concern. At a furniture auction she was found to have stolen a woman’s valuable shawl; a grocer kept her talking by a fire after seeing her put a pound of butter in her pocket, so that it melted and ran down her petticoats. Soon William Reid Clanny,6 an Irish doctor living nearby, saw potential in her vulnerability and introduced her to his friend Sir Robert Peat, one of many chaplains to the Prince Regent (he never actually met his royal patron) and quite a character in his own right. The son of a respectable watchmaker and silversmith of Hamsterley, County Durham (24 miles from East Herrington), Peat was 20 years Miss Smith’s junior, small, dapper, intelligent (he was a Doctor of Divinity from Cambridge), and a prolific gambler with expensive tastes, such that he was now very much in need of a wealthy wife.

Miss Smith accepted Sir Robert’s proposal, married her beau on 6 November 1815 and became Lady Peat. Although the settlement ensured that his wife retained half of her income for her exclusive use, Sir Robert now had £1000 a year to play with. After an attempt to introduce his wife to society in London proved an embarassing failure, Lady Peat moved back to Sunderland, to Villiers Street, where her weird habits continued. She would call on neighbours at mealtimes, in order to be fed for free, and filched cheap household objects from them. Whenever she was threatened with prosecution she would be forced to make financial restitution, often for sums hundreds of times more than the value of the stolen items. She and Sir Robert lived more or less separate lives, seeing each other only once or twice a year.

Meanwhile, what was happening in the investigation into Isabella Young’s murder? Sadly, it was a good example of how difficult it was to detect crime without photography or real scientific proofs. In early October 1815 The Globe reported that two unnamed brothers, ‘sons of a respectable tenant of Miss Smith,’ had been arrested on the coast of France and were being taken to Durham.7 Nothing further appears to have come of this, and it was not until nearly three years after the crime, in early 1818, that a an impoverished itinerant named was arrested and brought before magistrates. But there was no real evidence against him and he was discharged. Later, he was discovered in Morpeth, Northumberland – probably trying to claim poor relief – and, as the Poor Law required, was returned to Sunderland, where he decided to accuse a man called James Wolfe, with whom he had once worked in a quarry, of the murder.

Wolfe, a former tenant farmer who in 1814 had been evicted by Lady Peat for not paying his rent, was arrested in October 1818 in Carlisle and taken to Sunderland on suspicion of being an accessory. 8 His son George, a furrier (he cut rabbit fur), was arrested in Edinburgh and taken off to Durham gaol. A pocket-book found on him was thought to belong to Lady Peat, but because she refused to come and identify it, the magistrate released him on bail.9

Another suspect was arrested, this time on the word of James Lincoln, an old mariner from Sunderland. On 13 August 1819 John Eden, a soldier in the Durham militia, James Wolfe and his son George appeared at Durham Summer Assizes at Durham Shire Hall in Old Elvet charged with burglary, murder and arson. Hundreds of people turned up to catch a sight of the accused men or to observe the trial and the courtroom was packed. Among those watching proceedings were George’s employers, two Sunderland Quakers, John Mounsey and Thomas Richardson, who listened intently to what went on.10

The trial, heard by Mr Baron Wood, lasted all day, starting at 8am and finishing 15 hours later. The evidence was entirely circumstantial. The principal witness against Eden was his friend of 20 years James Lincoln, who swore that on 28 August 1815 Eden had come to his lodgings in Sunderland and urged him to accompany him and James Wolfe to East Herrington to rob Herrington Hall, during which he would probably ‘have to make away with that poor lass’, meaning Isabella Young. Ann Howe, who had accompanied Isabella to her door on the fatal night, swore that she and Isabella had walked along the road with on the Sunday before in the company of Eden, who had seemed very familiar with Isabella, saying he would be up to see her ‘some night this week’, although Isabella did not seem keen. Lady Peat said that a pocket-book found on George Wolfe was the one she left on her desk (he said it had belonged to his wife’s father). James Shaw claimed that in 1814 James Wolfe threatened to rob Miss Smith after he was thrown off his farm.

Quakers’ Meeting (c 1810), Thomas Rowlandson. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

At the end of the proceedings, the jury retired to a private room and an hour and three-quarters later emerged with their verdict. John Eden and James Wolfe were guilty. George Wolfe was not. Eden’s wife uttered a dreadful shriek and was taken out of the courtroom in a ‘state of insensibility’. Baron Wood, as he was obliged to do by law, proceeded to pass sentence of death on the prisoners.

Baron Wood was not convinced that the correct verdict had been given and was not alone in his doubts. Mounsey and Richardson, sure that the men were innocent, went to see the judge, who respited (deferred) execution, which in normal circumstances would have been carried out on 16 August, three days after sentencing. There was a good deal of suspicion about the motives of the James Lincoln and James Shaw. Why had they waited three years to tell their stories? Were they corrupted by the prospect of reward money?

With the help of Mr Greenwood, a Durham solicitor, Mounsey and Richardson produced affidavits which gave cogent alibis for both men. Their evidence was solid, based on documentation: log books, paybooks, receipts. At the time of the murder Wolfe was working at a quarry near Cockermouth, nearly 100 miles from East Herrington. After drinking for two days in Newcastle, Eden had been incarcerated in the guardhouse in Newcastle, but crucially Lincoln’s claim that Eden had come to his lodgings in Sunderland on the evening of 28th suggesting he accompany him to East Herrington to commit the crime was disproved because Lincoln was not even in Sunderland. He had been working on a sloop called the William & Mary and was at Marsk-by-the-Sea on the Yorkshire coast, nearly 40 miles away.

Royal pardons were granted to Eden and Wolfe and Lincoln was indicted for perjury. He was found guilty at a trial in August the following year, but the case was referred to the 12 Judges who decided for procedural reasons that the conviction was wrong.11

And what of Sir Robert and Lady Peat? He died at Brentford in 1837, and she departed five years later, aged 91 or 92, leaving property worth around a quarter of a million pounds. Poor Isabella Young, who was reduced in so many newspaper reports merely to ‘Miss Smith’s maid’, was forgotten. In the coming decades the capital code, or the Bloody Code as it was dubbed by its detractors, was reformed, until only murder and attempted murder (and treason) remained. It was over a hundred year after that that the death penalty was finally abolished.

The post No justice: The death of Isabella Young at Herrington, County Durham appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

April 13, 2019

A visit to St Pancras Old Church: Mary Wollstonecraft, Sir John Soane and Edward Carpue

St Pancras Old Church

Although I visit the British Library from time to time I always find myself too exhausted or too worried about getting stuck with rush hour crowds to spend an hour or so at St Pancras Old Church. Luckily, I was meeting an American cousin at her hotel in King’s Cross and doubly luckily she was keen to come with me to take a look, so together we headed north through the regenerated splendour of Granary Square and up by the Regent’s Canal. It takes only about 15 minutes to walk there from Euston Road.

Charles Pye, 1777–1864, British after John Preston Neale, 1771/80–1847, British. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The church is one of the few dedicated to St Pancras, the patron saint of children.1 Its establishment dates back to the 4th century which makes it one of the oldest places of Christian worship in London.

Unfortunately, there is not much of the medieval church left, although the interior includes, on the north wall of the nave, a section of exposed Norman masonry. Most of the church is mid-Victorian. It was extensively rebuilt in 1847 by architects Roumieu and Gough who replaced the old tower and restored the exterior. By then the church had fallen into disuse and dereliction, having lost its status as a parish church when St Pancras New Church on Euston Road was built in 1819–22. Further changes were made in 1888, in 1925 and in 1948 following wartime bomb damage.

Mary Wollstonecraft c.1790-1 by John Opie 1761-180. Purchased 1884. Photo © Tate. Reproduced under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported).

In 1797 Mary Wollstonecraft, who died shortly after giving birth to her daughter Mary Godwin (later Shelley), was buried at St Pancras Old Church. Her grave was where 16-year-old Mary Godwin was said to have planned her elopement with Percy Bysshe Shelley (and maybe did did other less decorous things). After Mary Shelley died of a brain tumour in 1851, her son Sir Percy Florence Shelley had the bodies of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin disinterred and moved to Bournemouth because his mother had expressed a wish to be buried with her parents. Percy Shelley’s heart, which famously survived his funeral pyre2 and was for years preserved by Mary in a silken shroud, was also buried with her.

There is a memorial stone to Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin in the churchyard at St Pancras.

Near the Wollstonecraft-Godwin memorial is this memorial, built in 1816.

The mausoleum of Sir John Soane and his wife Eliza, built of Carrara marble and Portland stone.

I was quite surprised to find that it was designed by Sir John Soane (1753–1837) for his wife Elizabeth Smith (“Eliza”), who died in 1815. To me, it is an unattractive assemblage of shapes and quite unlike the home of the architect and antiquary in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which is the epitome of neoclassical elegance. One interesting thing, though, is that the central structure inspired Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s design for telephone boxes.

Elizabeth Soane, née Smith, by John Jackson (1778-1831). Public Domain

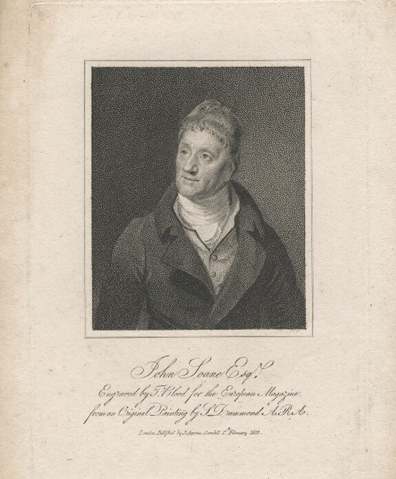

Sir John Soane by Thomas Blood, published by James Asperne, after Samuel Drummond, published 1813 © National Portrait Gallery, London.

The inscription on the memorial reads:

Sacred To The Memory of Elizabeth, The Wife of John Soane, Architect She Died the 22nd November, 1815.

With Distinguished Talents She United an Amiable and Affectionate Heart.

Her Piety was Unaffected, Her Integrity Undeviating, Her Manners Displayed Alike Decision and Energy, Kindness and Suavity.

These, the Peculiar Characteristics of Her Mind, Remained Untainted by an Extensive Intercourse With The World.

Neither of the Soanes’ two sons wanted to follow their father into architecture, which was a huge disappointment to Sir John. John, the elder of them, was lazy and uninspired, but the younger, George, was positively fizzing with animosity towards his parents. He married to spite them and when Eliza, then frail with gallstones, discovered that he was the author of an anonymous attack on the architectural work of his father, she fell ill and died soon afterwards. When Sir John found out that that George was living in a ménage à trois with his wife Agnes and her sister, and that he was abusing them and their children, he all but cut him out of his will. Both Soane, who died in 1837 and his son John, who died prematurely in 1823, joined Eliza in the mausoleum.

Many of the graves were removed in the 1860s (see below) but some have been retained, and a number of those are Catholic. On the north side of the church you will see the tomb of Edward Carpue (1740–1792) and his and wife Mary Carpue née Hodgson (1758–1806) and five of their children. The Carpue family was originally from Great Missenden in Buckinghamshire, and was also associated with the Lincoln’s Inn Fields area.

In 1760 Edward’s mother Anne Smallwood worked with Richard Challoner (d. 1781), a leading figure of English Catholicism, to set up a girls’ Catholic boarding school in Hammersmith. Edward and his brother Charles were Secretary and Treasurer of the Associated Catholic Charities, also set up by Dr Challoner.3 Joseph Constantine Carpue, a surgeon and anatomist who was said to have performed the first aesthetic “nose job” in 1814, was a second half-cousin.4 Despite his Catholicism, Edward Carpue, a vestryman at St Clement Danes and a juryman at the Old Bailey, who had a shoemaker business in Serle Lane, Holborn, was clearly respected and trusted. Sadly, his life was relatively short. In 1792, at the age of 52, he died of a stroke.

Other residents of the churchyard include the criminal thief-taker Jonathan Wild (d. 1725), composer Johann Christian Bach (d. 1782), John William Polidori (d. 1821), the young doctor and writer of The Vampyre, who accompanied Lord Byron on his European journey in 1816, the Chevalier d’Eon (d. 1810), a French transgender diplomat and spy. There is also the ‘Hardy tree’, an ash encircled with numerous overlapping gravestones, supposedly placed there in the mid 1860s by novelist Thomas Hardy when he was a lowly draughtsman given the task of exhuming and reburying human remains to make way for the railway lines.

The churchyard certainly has plenty to interest fans of the Long 18th Century like myself. The Church is Grade II listed and has a thriving performance programme.

The post A visit to St Pancras Old Church: Mary Wollstonecraft, Sir John Soane and Edward Carpue appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

January 27, 2019

Infatuation, bigamy and retribution: The trial of Ann and Eleanor Weston (1812)

After 16-year-old Maria Glenn was taken from her home in 1816 and narrowly escaped forcible marriage to a local farmer, her uncle claimed that those involved had tried to destroy her reputation by impersonating her doing disreputable things. The case of Ann and Eleanor Weston has some similar themes – committing perjury on the marriage licence and ‘personation’, the crime of fraud through pretending to be someone you are not – although the circumstances are very different. My book about the Maria Glenn case is available from Pen & Sword (hardback and ebook).

After 16-year-old Maria Glenn was taken from her home in 1816 and narrowly escaped forcible marriage to a local farmer, her uncle claimed that those involved had tried to destroy her reputation by impersonating her doing disreputable things. The case of Ann and Eleanor Weston has some similar themes – committing perjury on the marriage licence and ‘personation’, the crime of fraud through pretending to be someone you are not – although the circumstances are very different. My book about the Maria Glenn case is available from Pen & Sword (hardback and ebook).

One Sunday in April 1810 John Thompson, a middle-aged jeweller, decided to visit St Paul’s Cathedral. He had not come to attend a service but to see Lord Nelson’s tomb in the crypt.

Nelson’s Sarcophagus in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, from Thomas Allen, The history and antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark and parts adjacent (1827). London: Cowie & Strange.

During his visit he noticed an attractive young woman and, instantly infatuated, stalked her to her home half a mile away at 12 Fetter Lane, where he more or less barged through the door in order to make her acquaintance. From then on set he laid siege to Eleanor Weston, desperate to persuade her to have sex with him. A few weeks later she did and he promptly moved in with her and her sister Ann. He told them he was a widower.

It was not happy ever after. There were pressures on the relationship. Thompson was often away in Birmingham where he owned a factory producing paste (fake) diamonds and Eleanor’s friends were beginning to shun her: cohabiting was not respectable. She begged Thompson to marry her and he agreed.

Old Mitre Court, off Fleet Street. Eleanor Weston and her sister Ann lived here in 1810. © Copyright Martin Addison and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

In July the banns were read at St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street and on the morning of 9 August Thompson married Eleanor there. The sexton gave Eleanor away and Ann signed the register as a witness. Afterwards, there was a wedding dinner at Mitre Court, Fleet Street in the home of Susannah Currie, who ran a fruit and oyster shop and later that day, one of Thompson’s friends, Thomas Evans, dropped by on the couple at their home in St John Street to congratulate him.

The register shows that Eleanor Weston and John Thompson were married by the Curate on 9 August 1810 at St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, witnessed by John Wightman, the parish clerk, and Ann Weston, Eleanor’s sister.

In October Thompson went with Eleanor to meet the in-laws who lived in Portsea, Hampshire. Eleanor’s other sister and mother were much relieved that Eleanor’s situation had been regularised, even if her new husband, at 46, was on the elderly side. Then Eleanor became pregnant and soon afterwards, in March 1811, Thompson abruptly left London and disappeared for 12 weeks. When he returned he had something to confess to his wife: Margaret Jeffs, his wife of 23 years, was not dead but still living in Birmingham, although very ill and not expected to be around for much longer. He would he happy to marry Eleanor (properly) again once Margaret had departed this world. Then he left again, probably going off to Birmingham to see Margaret, who duly died in June.

Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin, A trial at the Old Bailey in London from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London (1808–11).

The revelation left Eleanor in a terrible pass. Her child would be a bastard and her relationship with Thompson was bad and getting worse, so much so that he withdrew his offer to re-marry her. The best she could do after the baby was born was to ask him for maintenance of the child and money for the rent, and this she did.

Meanwhile, Thompson was mulling things over. Clearly Eleanor and Ann could ruin him. They could prove he had committed a bigamy and perjury, so he had them arrested and prosecuted for conspiracy, claiming that they had hatched a plot to make it look like he had married Eleanor at St Bride’s by paying an ‘unknown man’ £2 to ‘personate’ him and sign the register. He said that Eleanor had told him that she was angry at her loss of reputation and that she and Ann had dressed as washerwomen for the wedding so that no one would recognise them.

While Eleanor and Ann were in prison awaiting trial, Thompson sent his attorney, Mr Draper, to see their mother, Eleanor Weston senior. He made her an offer: Drop the demands for maintenance for the child and Thompson would drop the prosecution. Mrs Weston gave him short shrift.

Baron Gurney, after Unknown artist, print, 1832 or after. Credit: National Portrait Gallery.

The trial of the Weston sisters at the Old Bailey started on 19 February 1812, at about 5pm, with Thompson represented by John Gurney and Peter Alley defending the Westons. Thompson’s lies caught him out. He swore it was not his signature on the register but two solicitors proved that he had tried to disguise his signature as he wrote it, that he had deliberately made it look like a forgery so that he could later deny it. He claimed he had an alibi for the wedding. On the afternoon of 7 August 1810, he said, two days before the ceremony, he boarded a coach to Birmingham, arriving at 11am the next morning and stayed for the next 10 days tending to his wife and his business. But the only witness who swore to this was housekeeper.

By midnight it was all over. The jury acquitted the sisters without hesitation. Thompson slunk out of the court and before long the tables turned. In December the Weston sisters brought an action for malicious prosecution. Their case was heard at the Court of Common Pleas and after an hour’s deliberation the jury awarded them the sum of £2000 with damages of £5000.

They probably never saw the money, as in early 1813 Thompson was declared bankrupt.

I can find no trace of a prosecution of Thompson for perjury or bigamy.

References

The Extraordinary Trial, at Length, of the Two Misses Eleanor and Ann Weston

The post Infatuation, bigamy and retribution: The trial of Ann and Eleanor Weston (1812) appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

December 21, 2018

Exhibition: Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill

To anyone who loves the Georgian era and has not yet visited Strawberry Hill House, the summer villa of collector, designer, author, MP, letter-writer and wit Horace Walpole (1717–1797), get yourself over to Twickenham, in south-west London before 24 February 2019.

It is a wondrous place, built as a fake Gothic castle, and well worth a visit at any time of year. For this exhibition, however, the Strawberry Hill Trust has borrowed a selection of Walpole’s collection of paintings, statues, artefacts, curios and relics and placed them in their original positions in the house. Not only that, they have briefed an army of volunteers who can explain the provenance and significance of the objects PLUS they’ve developed an app that gives you a tour of the building.

Horace Walpole (1795) by Henry Hoppner Meyer. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

As you navigate through the house, you get a strong sense of the personality of its erstwhile owner. Playful, waspish, intelligent, kind, generous, empathetic, witty, with a liking for what he called ‘gloomth’ (warmth+gloom).

A damp December Sunday afternoon was ‘perfick’ for the Gothic immersive experience. Horace would have stoked up the library fire, lit the lamps and cuddled his beloved dog Patapan. Such is the imprint of his personality on the house, as I navigated the extraordinary rooms I felt as if a ghostly Horace (officially Horatio, and ‘Horry’ to his friends) might just be waiting for me in the next room.

There were so many high points of the exhibition that I have chosen to talk about five of them.

1 ‘Eagle, on an altar base’ in the Great Parlour

Walpole did the usual things boys of his rank did – Eton, Cambridge and in 1739 to 1741 the Grand Tour, accompanied by his friend Thomas Gray, the poet who went on to write ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’. Gray was quite an earnest fellow and conscious of the marked difference between him, the son of a clerk and a milliner, and Walpole, the son of the Prime Minister. They fell out during their travels and Gray stomped home on his own. Horace later blamed the rift on his own immaturity and they were reconciled some years later.

While they were in Rome Horace bought ‘Eagle, on an altar base’, a Greek 1st-century marble sculpture, 77.5cm tall. For the exhibition, it has been borrowed from the Earl of Wemyss & March and placed in the Great Parlour, where it stood until 1763, when it was moved upstairs to the Gallery.

Eagle found in the gardens of Boccapadugli, Rome, mounted on a Roman altar.

Just as my companion was remarking that it was a miracle that the beak of the eagle was still attached after all these centuries, our room guide disabused us. The beak was broken off and stolen but was restored by Walpole’s cousin Anne Seymour Damer, an accomplished sculptor. They were close friends, so close that Horace left Strawberry Hill to her in his will. Damer was one of a number of female artists patronised by Walpole. Another reason to love him. He also opposed slavery.

Damer has been claimed by some as a lesbian and Horace’s own sexuality has also been a subject for speculation. There is not much firm evidence that he was gay but his on-off friendship with Henry Pelham-Clinton, 2nd Duke of Newcastle, lifelong lack of inclination to marry and a handful of luke-warm flirtations with women might point to it.

2 ‘Portrait of Sarah Malcolm in Prison’ in the Green Closet

In 1764 Walpole wrote The Castle of Otranto, A Story. Translated by William Marshal, Gent. From the Original Italian of Onuphrio Muralto, Canon of the Church of St. Nicholas at Otranto, which is generally accepted as the first Gothic novel. Purporting to be translated from a manuscript recovered by an ‘ancient Catholic family in the north of England’, it told a lurid tale of supernatural happenings, ancient prophecies, illicit marriages, kindly priests, endangered heroines, long-lost sons and bloody murder.

Throughout Strawberry Hill House you can see indications of Walpole’s fascination with the heavy mysteries of Catholicism. He was not himself a religious man. Quite the contrary. From his days at Cambridge, he was sceptical of the tenets of Christianity and hated superstition and bigotry. However, it is easy to see why William Hogarth’s painting of the 22-year-old ‘Irish laundress’ and convicted murderer Sarah Malcolm would have appealed to him. She sits, apparently calm, her rosary in front of her, the Newgate prison door to her right. Its dark drama is entirely Gothic.

Twenty-three-year-old Malcolm, a laundress to residents of the Inns of Court in the Temple, acted as lookout while her friends carried out a robbery in the home of one of her customers. The gang took £300 worth of cash, silverware and other items and murdered the three inhabitants, two elderly women and their servant. Sarah denied murder but after a five-hour trial on 23 January 1733 the jury took 15 minutes to convict her. She was the only one of the gang to suffer punishment. The others were arrested but not charged. William Hogarth obtained permission to sketch her on the day before her execution in Fleet Street. His work was engraved and sold as prints many times over.

William Hogarth, Portrait of Sarah Malcolm in Prison (1733). National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh.

3 ‘Horace Walpole in his Library’ in the Library

As we went through the house, almost every room became my new favourite. Each had something so amazing, cute or unique that it superseded all we had seen before. The Library, with its Gothic-arched bookcases and view over the fields to the river (now obscured from view by buildings, but one can imagine) was my most favourite (can I say that?).

The books are not Walpole’s collection but on loan from a library without a home. The originals were dispersed after the sale of his entire collection in a 24-day sale by his heirs in 1842.

Horace Walpole in His Library (detail) (1759) by J. H. Muntz (1755-59).

The stand-out artwork displayed here is a pen and ink and wash work by Johann Heinrich Muntz showing Horace Walpole in his library, standing to the right of the Library window, in the exact spot Walpole is shown in the drawing. This was a present to his cousin Henry Seymour Conway, who joked that Walpole looked too fat. He was famously spare of figure and ate little. The wan complexion he had as a sickly child never left him.

4 Cardinal Wolsey’s Hat in the Holbein Chamber

The Holbein Chamber, built as a bedchamber and with walls painted in royal purple (a greyish lilac), was designed to evoke the reign of Henry VIII and to house Walpole’s collection of 33 copies by George Vertue of famous Holbein portraits in the Royal Collection.

Unknown artist, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (1475-1530). Photo credit: Trinity College, University of Cambridge.

The Cardinal’s hat, for which there is no sure provenance, is wide and round-brimmed, not like that shown in portraits of Wolsey. To my untrained eye it does not look 500 years old but it does show Walpole’s whimsical side. He probably knew he’d been ‘sold a pup’ but didn’t care. He just wanted the hat for its Gothicky associations: a fall from grace, dangerous religion, tyranny. The Hair of Mary Tudor (Mary I) in a gold locket is displayed in a case in the Tribune. Same applies.

The confection of Strawberry Hill itself, built out with turrets and matriculations by Walpole, with its papier mâché fan ceilings and painted stone hallway, with paintings of his ancestors (and other people’s ancestors) is entirely a pretence. The hat could have been Wolsey’s. Why not just pretend it is!

5 Portrait of Frances Bridges, Countess of Exeter in the Gallery

Walpole hung this portrait by Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) of the widowed Countess of Exeter in the magnificent Gallery as if Frances Bridges were one of his own forebears. It was part of his playful take on the meaning of his pretend ancestral castle. Portraits of his father, mother (to whom he was devoted) and stepmother hang in the Great Parlour. The Walpoles were an old family but not grand and his father Robert was expected to become a sheep-farmer but became PM and the 1st Earl of Orford instead. Here, in the Gallery, are Medicis (more Gothic characters!), Sheffields, Marguerite de Valois. Altogether more exciting.

The Duchess of Exeter had her own Gothic past. The daughter of Lord Chandos, she was married first to Sir Thomas Smith of Abington, the Latin secretary to James I. After his death, she married Thomas Cecil, the first earl of Exeter, who died in 1622. Soon after she was accused of incest (with her step-son), witchcraft and attempting poisoning. James I got personally involved and issued fines to the accusers (her step-son’s wife and mother-in-law). She famously refused to be entombed next to her deceased husband in Westminster Abbey.

Suggested read: Art historian and provenance researcher Silvia Davoli’s account of her extraordinary discovery of an original Van Dyck (where you can also see the portrait).

The 1842 sale catalogue

Walpole’s own catalogue of his collection is online here: http://images.library.yale.edu/strawberryhill/index.html

Long Reads: Carrie Frye on The Gothic Life and Times of Horace Walpole

Strawberry Hill House & Garden

268 Waldegrave Road

Twickenham

TW1 4ST

Telephone: +44 (0)20 8744 1241

The post Exhibition: Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

December 7, 2018

Thomas Gainsborough: two exhibitions and two murders

Two, yes, two Gainsborough exhibitions in the space of a week. Who knew that I liked Gainsborough that much? I, for one, didn’t… But I do now. After seeing his early work at a special exhibition at Gainsborough’s House museum in Sudbury and his portraits of his family at the National Portrait Gallery, I am a convert. His light touch, his rapid, fluid brushstrokes, his sense of humour, his ability to animate his subjects, all are a revelation to me. Famously, he preferred to paint his beloved Suffolk countryside to the endless boring Suffolk worthies commissioning portraits, but for me his family subjects, which included the family dogs, surpass all.

Thomas Gainsborough, a print after a self-portrait by Thomas Gainsborough. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Thomas Gainsborough, born in Sudbury in 1727, was one of nine children of John Gainsborough and Mary Borrough. He was educated at the local grammar school, which was run by Mary’s brother, the Reverend Humphry Burroughs, but was not a particularly good student, preferring to roam the countryside, sketchbook in hand. Although it was seemingly an ideal childhood, perhaps he was also keen to escape home. John Gainsborough went bankrupt in 1733, when Thomas was six, but was helped out financially by his brother, Thomas. To make things a bit clearer I’ll call this Thomas, the artist’s uncle, Thomas senior; senior had a son, Thomas junior, the artist’s cousin.

A few years after John’s bankruptcy Thomas senior became embroiled in events that were to lead to his son’s murder and his own. And, ironically, it was these murders that allowed Thomas Gainsborough to build his career as an artist.

Thomas Gainsborough was born at the house in Sudbury Suffolk that was acquired in 1958 by Gainsborough’s House Society and turned into Gainsborough’s House museum.

In 1732 one of Thomas senior’s creditors, John Barnard, a mercer of Sudbury, went bankrupt. This meant that Thomas senior was allowed to claim the debts due to Barnard. Among those he pursued was Richard Brock, but all attempts to recover monies from Brock were unsuccessful. After Thomas senior started to prosecute Brock, his attorney, Richard Sabine, received an anonymous letter including the words:

I understand that you have ruined my friend Brock to all intents and purposes, which you must expect to suffer, for ruining a family so basely as you have done; that is, I mean in the next world you must expect to suffer for, in this I know your wealth will protect you. 1

Later, another letter was received, specifically targeting Thomas junior:

Mr. Gainsborough, fail not of acquitting Brock directly of his trouble; if you don’t by G— revenged of him your son we certainly will be. I am your friend, to acquaint you of the real design, for as sure as ever he was born, he will be put to an ominous end…

There was a deadline of 10 September and five days later Thomas junior was dead and buried. This did not deter Thomas senior, to whom the next threatening letter was addressed.

By god you shall never come to London safe; for, damn you, you will have no more mercy than the devil will have of you; and your rogue of a lawyer shall certainly drink out of the same cup.

Six months later, in March 1739, Thomas senior was murdered at the Golden Fleece in Cornhill, London. No one was charged or convicted for either of the murders.

Mr and Mrs Carter by Thomas Gainsborough (1747-8). John Gainsborough died in debt to Mr Carter. Was the unflattering appearance of his subjects Thomas’s subtle punishment? Photo credit: Tate.

Like his siblings, Thomas Gainsborough, who was then aged 12, was left £10 in Thomas senior’s will, but a note singled him out, asking the executors to ‘take care of Thomas Gainsborough… that he may be brought up to some light handicraft trade likely to get a comfortable maintenance.’ He was granted an additional £10, which paid for him to go to London to work with engraver Hubert-François Gravelot and then with painter Francis Hayman. The bequest set him up for life. (You can read more about the murders and how Mark Bills, director of Gainsborough’s House, researched them at The Art Newspaper.)

Thomas Gainsborough, Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape (c. 1750). Credit: Tate.

The Sudbury exhibition is small – displayed in two rooms in the museum, which is Gainsborough’s birthplace – and focuses on the artist’s early life and art. It takes Gainsborough’s story up to to 1748, when he returned to Suffolk from London, and includes paintings, drawings and ephemera from the collection, new acquisitions and loans. Gainsborough’s paintings during this era show his great love of landscape – to my eye, at this stage he had more skill here than in the human form, which is much more naive, verging on the naive. His subjects are often awkwardly positioned and the faces have a uniform, almost caricatured, look: big eyes set in a wide face, heads atop narrow necks. The early works were often portraits of people in a landscape, a format he continued throughout life, and one which allowed him to combine lucrative portrait-painting with his passion for outdoor scenes.

Ironically, portraits of his family, many of whom did look similar to each other, are more nuanced, even the early ones. The NPG exhibition, Gainsborough’s Family Album, features 50 works and takes us through Gainsborough’s entire life, to his death, aged 61, from cancer. The most painted were his wife Margaret Burr, an illegitimate daughter of the third Duke of Beaufort (who brought money to the marriage in the form of a £200 annuity from her father’s estate), and his daughters Margaret and Mary. The portraits, often executed at speed, were used to demonstrate Gainsborough’s virtuosity to paying customers but they have an animation and intimacy missing from many of his commercial commissions.

The Gainsboroughs’ marriage was long-lived but difficult. They married in 1746 when Margaret was only 18 (and pregnant) and Thomas a year older. Thomas had many affairs, which may account for the rather resigned expression on Margaret’s face in several of the ‘anniversary portraits’ (they were painted, it is said, on their wedding anniversary). Among my favourites were the paintings of Gainsborough’s daughters as children. Margaret and Mary Gainsborough, the Artist’s Daughters, Chasing a Butterfly (c 1756)

In 1759 the Gainsboroughs moved to Bath where Thomas built up a following and began to attract fashionable clients. He exhibited at the Society of Arts and the Royal Academy. Gradually he acquired a national reputation and was invited to become a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1769. His family portraits played a central role in his fortunes: they were painted as show pieces, to advertise his virtuosity. Although he preferred painting landscapes, these did not sell, but portraits (‘this curs’d face business’ in Gainsborough’s words) was another matter.

Among the most moving of them is ‘The Artist’s Daughters Chasing a Butterfly’ (c 1765), the symbolism of which perfectly combines the fleeting nature of childhood and the enthusiasms of youth, and it captures the dynamics of the relationship between Margaret and Mary. The elder daughter gently restrains the younger, who has reached for the butterfly that has landed on a thistle. Life was indeed a delicate balance for the girls. As young women they fell for the same man. Mary married him but the marriage lasted only a few months after which she returned to the family, showed signs of mental illness, and was cared for by Margaret, who never married.

The Gainsboroughs’ move to 80 Pall Mall (Schomberg House) in 1774 represented a significant social step up. Photo © N Chadwick. Available for reuse under this Creative Commons licence

In 1774 the family moved to Schomberg House in Pall Mall, where Gainsborough set up his studio. He had arrived. The great and the good beat a path to his door, keen to have their portrait painted by this most fashionable of artists: William Pitt, Johann Christian Bach, Mary Darby, lords and ladies without number, even George III and his family (he was the Royal family’s favourite portrait painter). In 1788 Gainsborough died of cancer at the age of 61 and was buried at St Anne’s Church, Kew.

Decades earlier, his talent had been spotted by his uncle, who left him a special bequest. Gainsborough used it to travel to London and train with the best and then he worked assiduously to improve his natural abilities. There can be few ten pounds in history that were better spent. The portraits of his family, full of light, love, warmth and movement, show his true delight, in them and in the images of them he created.

Gainsborough’s Family Album

National Portrait Gallery, London

Ends 3 February 2019

Early Gainsborough: ‘From the Obscurity of a Country Town’

Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, Suffolk

Ends 17 February 2019

Notes:

I have updated the original spelling. ↩The post Thomas Gainsborough: two exhibitions and two murders appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

November 30, 2018

Mike Leigh’s ‘Peterloo’: a review

Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt wearing his trademark white hat on the hustings in St Peter’s Field, Manchester. From Mike Leigh’s Peterloo (2018).

On 16 August, 60,000 men, women and children, most of them working people, from Manchester and surrounding towns and villages, assembled in St Peter’s Field, an urban square edged with buildings and fed by narrow streets. They were unarmed and dressed in their best clothes. Earlier, the men had practised marching, all the better to keep discipline. Some firebrands among them had wanted to bring arms — cudgels, pikes, knives — but were persuaded to leave them behind. The star speaker, Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, threatened to pull out if the protestors had weapons.

They were understandably nervous, although there was something of a celebratory atmosphere. It was a lovely summer’s day, a Monday, and that was usually a working day. They had abandoned mills, factories and workshops to make their points: that Manchester was without parliamentary representation of any kind and that the franchise should be widened to all men. As the crowd strained to hear Hunt’s words, delivered from the hustings, a magistrate read the riot act. This meant that if the crowd failed to disperse they were liable to be charged with riot, a capital charge. 1

Massacre at St. Peter’s or “Britons strike home”!!! by Isaac or George Cruikshank. The Yeomanry attack the crowd with butchers’ steels and blood-stained axes, shouting ‘Down with ’em! Chop ’em down! My brave boys’. © The Trustees of the British Museum

No one in the crowd heard the magistrate’s words. He called in the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, drunk and itching for a fight, and after them the Hussars. The resulting bloodbath left an estimated 18 dead, their number including four women and a child, killed by sabre cuts and trampling. Hundreds were injured.

Mike Leigh’s film tells the story of that day by painting in the background: the aftermath of 20 years of war with France and the trauma of Waterloo; the Corn Laws that inflated the cost of bread, the staple diet of the poor; the inbuilt inequity of a political system that hands over £750,000 in thanks to the Duke of Wellington but begrudges ordinary people an extra shilling in their wages; the corruption of the ruling class, which happily exploits the poor and punishes them for objecting; their nervousness that calls for political rights would lead to a French-style revolution.

Leigh thinks Peterloo should be taught in school and I agree. Peterloo was a watershed, although it may not have felt so at the time. It joins other demonstrations of democratic aspiration, the Spa Field riots, the Blanketeers’ march and others, on the path to the Great Reform Act and ultimately universal suffrage.

Anonymous print titled ‘To Henry Hunt, Esqr. as chairman of the meeting assembled on St. Peter’s Field, Manchester on the 16th.. of August, 1819’. In 1819, women in and around Manchester had begun to form their own reform societies. Many appeared at the meeting at St Peter’s Fields dressed in white as a symbol of their virtue. © Trustees of the British Museum

I saw the film yesterday afternoon, in a chilly screen in Greenwich. Three hours is a long time to endure over-efficient air conditioning. Added to that, the projectionist had failed to turn off some of the overhead lights. Was Peterloo engaging enough to get me to ignore these distractions and immerse myself in 1819 Manchester?

Oh, how I wish I could say yes. There is so much to love in Peterloo. The locations are authentic. All that industrial red brick! those amazing weaving machines in perfect working order! the black interiors of the magistrates court! the rugged moors! the muted colours! The acting is great. The cast is brilliant but take a bow Maxine Peake, Rory Kinnear, Tom Gill. The clothes are realistic. There’s no we-just-got-this-back-from-the-dry-cleaners look I’m relieved to report. The music is superb. The role of women is not ignored. But…

But… There’s a lot of polemic. Speeches that are clearly taken from primary sources. Why would I object to that, I ask myself? It’s historical accuracy after all. But it sounds like preaching and it sits alongside the overdone explication (watch out for the potted rationale for the Corn Laws). I found myself thinking that I might prefer a straight-up documentary or a handout.

The ‘attack’ on the Prince Regent in 1817 was the perfect pretext for suspending Habeus Corpus. In this satirical print attributed to Isaac Cruikshank, a large man representing John Bull is hung upside down by his feet between two pillars labelled Lords and Commons, with Lord Sidmouth on the left and Castlereagh on the right. © The Trustees of the British Museum

To my shame, I also found myself worrying about some of the details of the production. Would poor weavers really light candles – two candles, actually, and in the summer! think of the expense – so that they could chat to each other about politics at bedtime? Wouldn’t Joseph’s soldier’s jacket have fallen to pieces after four years of non-stop wear? Could magistrates really recommend to a higher court that unconvicted defendants be executed? Do we know that it was definitely a potato thrown at the Prince Regent’s carriage in 1817?

However… This is all pointless nit-picking. The problem with Peterloo was the script. Real events rarely fit neatly into a three-act story arc. Leigh tried to overcome this by bookending the film with the fate of Joseph, a bugler traumatised at the Battle of Waterloo, and unable to find work when he returned home (he was possibly based on real-life John Lees, who was sabred during the charge and who died of his wounds some days later). Joseph had given his soul to fight for his country, which callously cast him and thousands like him aside. But the film’s broad canvas means that individuals are painted in broad brushstrokes and poor Joseph never feels like a real person. It’s the same with the ‘baddies’, who are reduced to a bunch of pantomime villains.

Also, why did no one spot the spies lurking around the illicit Reformist meetings? They were wearing totally suspicious hats and gurned away like mad (cf Joseph Nadin, the wicked Deputy Constable of Manchester, and ‘Oliver the Spy’). At times, the film felt like melodrama.

Still, to tell the story of Peterloo in under three hours and to make its politics understandable to people who never have heard of it is a huge achievement. Ignore my petty peeves. It is an excellent, brave, ambitious film, flawed just as all excellent, brave, ambitious films are flawed. Go and see it on a big screen if you can. It is superbly photographed and beautifully produced, and it is very good at helping you understand what was going on in Britain 200 years ago. As it happens, there’s quite a lot of synergy with what is going on now… but that is an angle I’ll leave for another day.

Notes:

This was no idle threat. In 1812, Hannah Smith, one of the women in my book Women and the Gallows, was hanged at Lancaster Castle for riot and highway robbery alongside seven men found guilty of riot, arson, housebreaking and stealing food in the Manchester food riots. ↩The post Mike Leigh’s ‘Peterloo’: a review appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

November 8, 2018

Gauntlet, Gilmore & Roberts’ song about Mary Ashford

The footprints matched the town’s suspicion

Mary Ashford, the poor girl drowned

They locked him up in the local prison

Abraham Thornton must go down

Abraham Thornton must go

Down with the jury who cut him loose

Down ’til his neck’s in the hangman’s noose

Down with the evidence he hid away

For my sister’s life he’ll pay

He threw down the gauntlet

Settle it with a fight

He threw down the gauntlet

Whoever wins is right

But I’m no match for a brute like Thornton

That much I know

So he threw down the gauntlet

And I let him go

In October 2018 Gilmore & Roberts, three times nominees at the Radio 2 Folk Awards, released a new album A Problem of Our Kind. It opens with their single ‘Gauntlet’ which tells the story of the murder of Mary Ashford, which is also the subject of my latest book.

Gilmore & Roberts have had some great reviews for the album, including this from Folk Radio UK :

The album’s opening track, Gauntlet, is a brawny folk-rock masterstroke. Spare but heavy, full of the fiddle screech and forceful drums that characterised the best bits of mid-seventies Steeleye Span, it is nonetheless very much the duo’s own song. Because where Gilmore and Roberts really excel is in their songwriting. They split the job roughly half and half, and Gauntlet is one of Gilmore’s songs. It is an emotional and eloquent account of one of the strangest and most influential court cases in British legal history, the Ashford v Thornton case of 1818. Gilmore writes herself into the mind of William Ashford, brother of Mary, whom he was certain had been murdered by Abraham Thornton. Ashford appealed against the ‘not guilty’ verdict, causing Thornton to invoke the arcane right of trial by battle – the proverbial throwing down of the gauntlet. In a few swift strokes, Gilmore paints a vivid picture of Ashford as a righteous, principled man stymied by physical meekness. Like many true stories, there is no happy ending, and the song raises more questions than it answers. It is a subtle and highly entertaining way of shedding fresh light on a small but important corner of our shared past.

You can order A Problem of Our Kind from Gilmore & Roberts’ website.

The post Gauntlet, Gilmore & Roberts’ song about Mary Ashford appeared first on Naomi Clifford.

October 12, 2018

15 October 1807: A fake fight results in catastrophe at Sadler’s Wells

Theatres have been much on my mind lately. When I have an odd moment, I transcribe 18th and 19th-century playbills for the LibCrowds project (there is something soothing about a repetitive task that requires accuracy) and I recently gave a talk on the first night of the Royal Coburg theatre, now known as the Old Vic, of course, as it features in my book The Murder of Mary Ashford.

Neptune and his horses: a spectacular at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London, 1808-1810. The pit had backless benches; the gallery was at the back and was standing.

On the night of Thursday 15 October 1807, John Dobson, his wife, young son and three or four friends were in the pit at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in Islington, north London. Although the theatre was exceptionally crowded – it was a benefit night and about 2,000 people were in the house – the audience was good natured and well behaved. Just before the closing scene, at about about ten o’clock, however, Dobson noticed a group of eight or ten people, two of them smartly dressed ‘vulgar women’, join the throng. Some of the men started to push each other about. Dobson, standing on a bench in order to see the stage thought there was something about their behaviour. It seemed to him that the quarrel was staged.

Perhaps a cry of ‘Fight! Fight!’ went up. Perhaps someone misheard it as ‘Fire! Fire!’ This is how many people later explained the panic that spread through the audience and the subsequent rush to leave the building. Seeing what was happening, one of the actors, George Smith, one of the actors, tried to shout to the audience that there was no fire. He was joined by Mr Reeves, one of the owners of the theatre, who got up on stage with a ‘speaking-trumpet’ to do the same, but no one could hear them above the shouting and screaming. The whole house was in chaos, with people jumping 30 feet down from the gallery to the pit to escape the non-existent flames and musicians lifting people over the orchestra onto the stage.

Outside in the yard, those who had escaped were discovering that there had been no fire and heading back inside to find their companions. But their way was blocked by a stream of people still coming down the stairs from the gallery. The result: a logjam. Then someone tripped on the stairs and people started falling on top of each other. It must have happened in moments: a pile of bodies at the foot of the stairs.

In the pit, Dobson, who had seen no fire and nor smelled smoke, had persuaded his party to stay put until the crowd had dispersed.

Sadler’s Wells (1804), John Greig after Samuel Prout. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

There is a terrible irony about the disaster, which arose from fear of flames: Sadler’s Wells’ name remembers the water source (thought to have healing powers) it was built over and in the winter of 1803 the manager, Charles Dibdin the Younger, installed a large water tank (80 by 30 feet) at stage level and filled it from the nearby New River. The following season he staged the astonishing spectacle The Siege of Gibraltar, during which scale models of ships were moved around the ‘sea’ by boys wearing ‘thick duffel trousers’ and encouraged with brandy.

A contemporary observer wrote:

It acted like electricity, a pause of breathless wonder was succeeded by stunning peals of constant accclaimation; and when the Ships sailed down, in regular succession, ‘rolling on their way’, their sails shifted in the wind; their colours and pennants flying; and their ordnance, as they passed the front of the stage, firing a grand salute to the Audience, the latter seemed in an extasy.

Sadler’s Wells came to be known as ‘the aquatic theatre’.

Charles Dibdin the Younger in 1819. Courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Dibdin was trying to improve Sadler’s Wells’ reputation for attracting drunken loutish audiences. Not only was he offering the escorts back into central London after dark (Islington was then still a rural suburb) but he started hiring famous performers such as the Shakespearian actor Edmund Kean and the clown Joseph Grimaldi.

After the panic was over, about 30 bodies were brought into the proprietor’s room, 18 of whom were obviously dead, killed by suffocation or crushing. Mr Sharpe, a surgeon from St Bartholomew’s who happened to be in the audience, worked hard to save the other 10 or 12 with other medics who had been sent for. One victim was ‘an athletic man’ who came round after he was bled, only to find his wife lying dead next to him. ‘The poor fellow became frantic, and was carried away in a state of desperation,’ according to some reports.

The injured were removed quickly: a sailor from The York, who had been severely bruised, to The London Hospital in Mile End Road; five others to Sir Hugh Middleton’s Head, opposite the theatre; and four to Islington Spa. Some had broken bones but all of them are thought to have recovered.

Four of the ‘ruffians’ who had started the fake fight were arrested. John and Vincent Pierce, Mary Vine and Elizabeth Luker were taken before the bar at Hatton Garden. Despite their apparent callousness (when they were informed that 18 people had died as a result of their ‘riot’, they were alleged to have said something along the lines of ‘Well, we don’t care. We can’t be hanged for it’) they could not be charged with a felony crime. Their actions were intended to distract the audience while they picked pockets, not to result in death.

The Sir Hugh Middleton’s Head, opposite Sadler’s Wells Theatre. Credit: Wellcome Collection

A mob gathered outside the theatre and the Clerkenwell Volunteers were called in to control them, while inside the theatre in three separate rooms the 18 bodies (‘horribly disfigured and contorted’) were being ‘decently laid out upon temporary tables’ and labelled with their names and addresses, ready for the Coroner. They were overwhelmingly young people and included at least five children aged 16 or under:

John Ward, 16, an errand boy, of Glasshouse Yard, Goswell Street, was identified by a 17-year-old friend Mary Ann Pede, who lived next door and who had gone with him to the performance. They became separated after the cry of ‘Fire!’ went up.

Lydia Carr, of 23 Peerless Pool, City Road, identified by her brother John

Elizabeth Margaret Ward, 21, of 20 Plumtree Court, Bloomsbury, was identified by her mother. Elizabeth had gone to the theatre with her sister and ‘a young man’ who were too injured to attend the inquest.

Benjamin Price, 12, of 33 Lime Street, Leadenhall Street

Joseph Groves, a servant to Mr Taylor of Hoxton Square, identified by his brother John

Edward Clements, 13, of Paradise Court, Battlebridge, identified by his father John.

John Labdon, 20, of 7 Bell Yard, Temple Bar

John Greenwood, an apprentice, of King Street, Hoxton Square, identified by his employer, John Simmons

Sarah Chalkey, of 24 Oxford Road, identified by Mr Monk, a War Office messenger.

Rhoda Ward, 16, of The Crooked Bill, Hoxton, identified by her mother Martha, who had been in the gallery with her daughter.

Mary Evans, of Hoxton Market, identified by her son William and sister Sarah.

Caroline Terrell (sometimes given as Twitcher), an ‘unfortunate woman’, who was pregnant, of Plough Court, Whitechapel, identified by Class Jacobs, a Swedish sailor from The York, who had been with her for three days before they went to the theatre together.

James Philliston, 30, of White Lion Street, Pentonville

Rebecca Sanders, aged 9, a domestic servant, of 12 Drapers Buildings, London Wall, identified by her father. She had gone to the theatre with her mistress to help mind the baby.

Rebecca Ling, of 5 Bridge Court, Cannon Row, Westminster, identified by John Myers

Richard Bland, 28, of 13 Bear Street, Leicester Fields

Charles Judd, 20, of Artillery Lane, Bishopsgate Street

William Pincks, 17, of Hoxton Market, identified by his mother Mary Pincks

Most of the dead were found to have little money and no valuables on them. The coroner’s clerk retrieved only 20 shillings (£1) from them in total. As they were, in the main, people of slender means this was not perhaps surprising, but there remained a suspicion that the bodies had been robbed.

George Hodgson, the Middlesex Coroner, arrived at ten ‘clock and convened the inquest in Mr Dibdin’s drawing room. Then the jury viewed the bodies, the stage and the gallery stairs and were satisfied that no fire had occurred. The friends and relatives of the dead gave evidence as did actors and employees of the theatre. At the conclusion, Mr Hodgson instructed the Jury, who duly declared that the dead had been killed ‘casually, accidentally and by misfortune’. Hodgson praised the management of Sadler’s Wells who had acted ‘most becomingly’ and had done everything they could to prevent the panic.

The four prisoners appeared at Middlesex Magistrates Court. Mary Vine was remanded to Clerkenwell prison and the others were bailed.

The following day, Sunday, the bodies were taken away for burial. Dibdin, who paid the funeral expenses of the ‘unfortunate’ Caroline Terrell as no relatives came forward to claim her body, was plagued with false claims for expenses.

On 2 November the theatre reopened for a two-night benefit for the relations of the victims.

In December, John and Vincent Pierce and Elizabeth Luker were sentenced for exciting a riot and disturbance at Sadler’s Wells Theatre. After Mr Mainwaring lamented their ‘outrageous conduct’ and the terrible consequences of it – ‘whole families plunged in irremediable ruin, by the loss and protection of those who were their natural protectors and guardians – he gave John six months, Vincent four and Elizabeth 14 days imprisonment.

Acting magistrates committing themselves being their first appearance on this stage as performed at the National Theatre Covent Garden. Sepr 18 1809. © British Museum, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The danger of fire in theatres was real. Ideas for improved safety, suggested by journalists rather than by the authorities, included having ready-made banners at hand to tell people that the theatre was not on fire, and making sure that there was enough space for fleeing people to congregate without blocking exits for other people. However, nothing changed and nearly a year after the Sadler’s Wells tragedy, Covent Garden Theatre was destroyed by fire with the loss of 30 lives, and Drury Lane Theatre burnt down in March 1809.

Commotions among theatre audiences were a regular occurrence. When Covent Garden Theatre reopened in 1809 the audience took the management’s decision to raise ticket prices as an outrageous infringement of their rights and three months of riots ensued, during which, it is said, 20 lives were lost. The violence only ended with the manager, John Philip Kemble, reverting prices and apologising.

Sources

The Annual Register for the year 1807 (1809). London: W. Otridge and Son et al.

McPherson, H. (2002). Theatrical Riots and Cultural Politics in Eighteenth-Century London. The Eighteenth Century, 43(3), 236-252. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41467906

Remington, S. (1982). Three Centuries of Sadler’s Wells. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 130 (5312), 472-481. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41373417

Morning Chronicle, 26 October 1807, 3B.

Morning Post, 17 October 1807, 3C; 19 October, 3D; 24 October 1807, 4B; 9 December, 4B.

Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 17 October 1807, 3B; 19 October, 3B.

The post 15 October 1807: A fake fight results in catastrophe at Sadler’s Wells appeared first on Naomi Clifford.