Davey Davis's Blog, page 8

July 16, 2024

David Davis

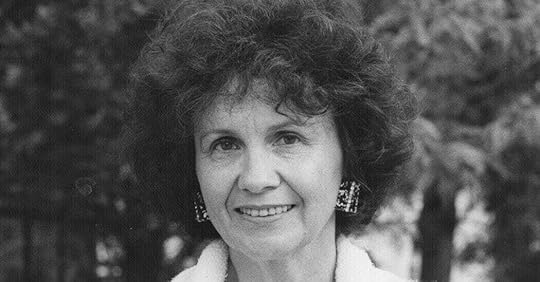

Only July 7, the Toronto Star published a statement by Andrea Robin Skinner on the subject of her mother, Canadian writer and Nobel Prize winner Alice Munro. Skinner details a long history of horrific neglect by Munro, including her abetting of Skinner’s sexual abuse by her stepfather—Munro’s husband until his death in 2013—the rapist Gerald Fremlin.

I don’t know why I read Skinner’s statement. I avoid reportage on this topic in general, and while I had certainly heard of Munro—who hasn’t?—if I had ever read anything by her before July 7, I didn’t remember it (I’m not a very good literary citizen). Skinner’s words pitched me into such a wrathful despair that I wasted a summer morning wishing I could disinter her mother’s ninety-two-year-old bones and stamp them into powder.

As Skinner’s statement went viral, my rage found more targets, particularly among those who felt the need to diminish or “reckon with” her disclosure: How could Munro, my favorite writer, do this (to me)? Am I allowed to go on enjoying her work, now that I know she chose a child predator over her daughter? And my personal favorite: How can I find a way to carve off pieces of Munro’s guilt and reassign them to the men she collaborated with—Fremlin and Skinner’s own father, who knowingly sent his daughter back to her mother’s home for the rest of her childhood—so as to maintain my fantasies about the maleness of violence?

Seeking some measure of your own moral goodness based on the art you respond to is to misunderstand art itself, but I can’t stop people from doing it. I don’t see the point in discontinuing to read or teach Munro simply because we now know that she was a covert abuser of children. Not even Skinner asked for this:

I also wanted this story, my story, to become part of the stories people tell about my mother. I never wanted to see another interview, biography or event that didn’t wrestle with the reality of what had happened to me, and with the fact that my mother, confronted with the truth of what had happened, chose to stay with, and protect, my abuser.

With Skinner’s brave revelation, her story is now Munro’s legacy, just as the sins and violations of other artists are theirs. That is the reckoning here, not anything that you or I can do with our phones, wallets, or bookshelves. There are some artists that I can no longer enjoy because I know what they have done; there are others that I continue to enjoy, despite knowing what they have done. This is not uncomplicated for me, nor do I think it should be. But while I believe we ought to consider the writer’s life alongside their work, to approach a situation like Skinner’s with a scale in hand, ready to weigh a human life against a work of art, is among the most depraved things I can imagine.

As Fiona’s mind and memory fail her, her husband, Grant, puts her in assisted living, only to begin losing her to another man. This is the plot of Munro’s 2001 short story The Bear Came Over the Mountain, which I read for the first time a few days ago. Exploring themes of marriage, desire, and fidelity—of all kinds—Mountain is at first unassuming, then unflinching. It’s beautiful, and terribly sad, and I understand why it’s considered one of Munro’s best1.

I read Mountain because I was curious, not because I was searching for a smoking gun or secret code. It’s just art, even if the artist was, as I maintain, a contemptible person. But I cried reading it, as I cried reading Skinner’s statement. For different reasons, I believed, until I thought about it some more. It’s not that I see myself in these stories, both the real and the fictional (although, for different reasons, I do). It’s that they allow me to see the people behind them. Oh, that’s me, is the beginning of, Oh, that’s you! That is art. At least I hope it is.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of the fundraisers featured on Gaza Funds.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Much of its sadness is, I think, is the unintended result of its being a portrait of straight, white, upper-middle-class monogamy, and the loneliness it creates.

July 14, 2024

David Davis 45, part 4

In Jean Giono’s The Song of the World, men live in rivers, women know the height of trees by their scent, avalanches are personalities, and bulls can speak to humans. There is nothing about this transcendent French novel that feels like fantasy, yet it embeds its characters in the textures of the world around them so deeply and beautifully that everything—the quickening of sap, the hunting of boar, the melting of glaciers, the burning of buildings—has an undeniably magical quality.

If magical rubs you the wrong way, some other words to orient you to this wonderful book might be pagan, primordial, or sybaritic1. To give you a better idea of what I’m talking about, here is part of Giono’s description of the “sparkling season” of winter in the fictional region of Rebeillard:

Daylight no longer came from the sun only, out of a corner of the sky, with each thing carrying its own shadow; light bounded from all parts of the glistening snow and ice, in every direction, and the shadows were thin and sickly, bestrewn with golden dots. It seemed as if the earth had swallowed the sun and was now the sole light-maker.

Or take this autumn rainstorm:

Now they were alone on the road. Flights of dead leaves were swept off by the rain. The woods were being stripped bare. Huge water-polished oaks emerged from the downpour with their gigantic black hands clenched in the rain. The muffled breath of the larch forests; the solemn chant of the fir-groves, whose dark corridors were stirred by the slightest wind; the hiccups of new springs gushing out amidst the pastures; the brooks licking the weeds with their greedy lapping tongues; the creaking of sick trees already bare and slowly cracking in two; the hollow rumbling the big river swelling down below in the shadows of the valley—all spoke of wilderness and solitude. The rain was strong and heavy.

The New York Times Book Review described the medievally modern Song, originally published in 1934, as an epic, “in the true sense of a much-abused word.” The inspiration he took from the Iliad and Walt Whitman is clear2. This gets at the ways in which setting and style provide the scaffolding for a Song’s riveting story: Antonio travels away from his beloved river, and the woman he can’t stop thinking about, to save a friend’s son from a powerful man’s vendetta3. It also gets at the ways in which Song is as much about Antonio as it is every other character, the rivers and forests and towns in which they find themselves, and the time before and after the action takes place.

I think it goes without saying that I recommend this book to you, but I’m writing about it for this series on the sex scene, specifically, because it doesn’t have any. The only lovemaking we see in in Song is brief, metaphorical, and not even entirely human, taking place during a fertility celebration in which a Wicker Man-style effigy is burned in the town square:

A drover had taken a lavender torch. He tucked up the skirts of the mother of wheat. He began to make love to her underneath with his blazing torch, and suddenly she took fire.

When they’re not tasked with advancing the plot, sex scenes are often relied upon to create eroticism, but Giono accomplishes this with a cast characters whose lives, while at times violent or precarious, foreground the sensuality of human (and interspecies) relations. Antonio enjoys stroking his own “velvety” body, feeling the muscles, bones, and scars under his fingers; women characters travel alone, breastfeed, give birth, have autonomy over their sex lives, and spend time with men without fearing for their safety—even while nude, as in a scene where Antonio and his friend come upon a barnful of men and women partaking in a kind of sauna situation; and violence, injury, illness, dying, and death are neither avoided nor fetishized, but experienced as natural and inevitable, if also terrible, confusing, and frightening.

I don’t mean to say that suffering or patriarchy are prerequisites for the sex scene. But I do mean to say that the sex scene is often rendered and understood as distinct from real life in literature and on the screen4. Song is different. Its sensual world of purpose, desire, and connection is so lush on the page that, as much as I love a good sex scene, I don’t miss it here at all.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of the fundraisers featured on Gaza Funds.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1I have not seen the Marcel Camus film on which The Song of the World is based (see image up top), but the screenshots I’m finding bring to mind Old/New Hollywood bridges Dr. Zhivago (1965) and Jeremiah Johnson (1972).

2Other comparisons I would make, some contemporary, some not: William Faulkner (/McCarthy), Isaac Bashevis Singer, Ernest Hemingway.

3In light of a very long and intense jacket quote from Giono, a famous pacifist who was twice imprisoned (though not charged) as a Nazi sympathizer, I found myself second-guessing that effect. Here’s some of the quote:

“I have tried to make a story of adventure in which there should be absolutely nothing ‘timely.’ The present time disgusts me, even to describe…At this very time when Paris flourishes—and that is nothing to be proud of—there are people in the world who know nothing of the horrible mediocrity into which civilization, philosophers, public speakers and gossips have plunged the human race. Men who are healthy, clean and strong. They live their lives of adventure. They alone know the world’s joy and sorrow.”

It’s giving reactionary! But I know little about this author, and his Wikipedia page is spare. An interesting complication, at any rate.

4And for this we can thank patriarchy, specifically censorship, but certainly in other expressions, too.

July 9, 2024

David Davis 45, part 3

Back in January, I began writing a series on the sex scene, which was promptly sidelined after I began another series on how to vet sadists, dominants, and tops. I don’t like to work out of order (though though two series did have some overlap), but hey—when the spirit calls, you gotta listen.

With my vetting guide finally complete, I can now return to writing about how sex onscreen and in literature is not just accomplished by the artists, but received by the audience. Which isn’t to say that the sex scene has ever lost my attention—I’m into it, famously! But my memory did have to be jogged, and by a surprising bit of media: Richard Linklater’s Hit Man, which came out last year to what Wikipedia is telling me was critical acclaim1.

Acclaimed or not, I agree with the reviewer for Bright Wall, Dark Room, who found Hit Man—the story of romantic loser falling in love with a suspect while on duty as a Mrs. Doubtfire-style sting operator for the NOPD—to be thematically noncommittal, poorly written (in terms of dialogue), and badly lit, a tragedy considering the extreme physical beauty of its stars. Though leading man Glen Powell is undeniably charismatic, he has yet to live up his dynamite turn as ur-bro Chad Radwell in Ryan Murphy’s Scream Queens, much less to the Tom Cruise comparisons, which I maintain are the collision of proximity with the lack of a clear heir to His Impossibleness, who turned 62 this week.

Indeed, Powell’s sexual chemistry with love interest Adria Arjona is one of Hit Man’s few strengths, which I bring up because—shocker—it’s on display in more than one halfway decent sex scene, which is all the more remarkable in a movie that’s too politically wishy-washy to even be called conservative.

Though it promised laughs, “Hit Man” was also not funny, except for the 15 seconds when Powell freaked this Tennesee Williams meets Andy Warhol meets Fassbender in Fincher’s “The Killer” (2023) persona, which sent me. Where is her movie!

Though it promised laughs, “Hit Man” was also not funny, except for the 15 seconds when Powell freaked this Tennesee Williams meets Andy Warhol meets Fassbender in Fincher’s “The Killer” (2023) persona, which sent me. Where is her movie!Now, I don’t recall either actor revealing anything in the bathing-suit zone, and there’s definitely nothing sexually outré, other than the implication of cunnilingus, which depending on your moral panic can definitely pose a problem for us sex scene absolutists. But neither is Hit Man cutting away at the kiss, compartmentalizing sexual content to be cut for international markets (at least, I don’t think it is), or compensating for its relative sexual laxity by throwing in a real pervert for the shock value, though it certainly had the opportunity to, what with Powell’s extended dress-up scenes just begging for a read from one of these gender academics.

As dull as I found it, Hit Man is, or at least aspires to be, a movie for grown-ups, engaging with grown-up preoccupations—like workplace ethics and identity—and depicting grown-up activities—like police entrapment and extramarital sex. And I guess that’s something, isn’t it? Neither particularly reactionary nor aspiring to the vanguard, its refusal to say or do anything is almost refreshing in its nothingness. While failing to deliver on its marketing as a sexy, rompy, throwback to the action movies I grew up on, the ones that Trojan horsed romance with guns, titties, and light patriotism, Hit Man’s absence was so comforting that it almost pushed it over the finish line, anyway. There’s no there there, but isn’t that what we’re getting out of the elevated binge fodder of The Bear and Brat and whatever else we’re using to distract ourselves from everything?

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of the fundraisers featured on Gaza Funds.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Not to be confused with the Plasmatics song.

July 2, 2024

David Davis

Body scan

Body scanHair: I bleach it myself about two times per month. Professional bleaching is a luxury expense, but if you know how to do it, it’s really cheap and not so difficult. I don’t know what I would do if I wanted long hair, though—my process would absolutely wreck it, Olaplex or not. Luckily for me, I knew from the age of 18 that I would never grow it out again. Right now I’m getting it cut by either this dyke barber around the corner, or by my boyfriend, also about two times per month.

Head: After many years of daily cannabis use (primarily edibles, because I hate coughing), I stopped entirely about two weeks ago, save a puff off Jade’s joint to come down from some Pride drugs. I think it’s because my siblings came to visit me in New York last month, and while they were here I found myself wanting to use it it like I did when I visited them at my mom’s home, an experience that required complete dissociation for me to survive without committing assault. While I was happy to see them, I was also nervous; I wanted to eat so much weed that I wouldn’t have to hear or speak or think. But I resisted the impulse and enjoyed their company instead, and I’m glad I did. After that, stopping just sort of happened, though I miss it during certain transitional times: clocking off work, driving to Riis. But socializing without it is actually easier, and I’ve begun to dream again, every night.

Shoulders: After Charlotte Shane recommended Rolfing in one of her Instagram stories, I had an intake with a provider for my chronic shoulder pain, which has come and gone for several years. We talked about how scar tissue from top surgery (which I had twice, due to a botched procedure that was one of the most traumatizing events of my life) has likely affected the alignment of my body1 . Scar tissue is amazing, the provider said. It holds our body together for us after trauma. But it’s also rigid by design, so we often need help helping our bodies resettle. I haven’t gone yet, because after our intake, the current wave of pain suddenly went away, as it occasionally does. I guess I’ll wait for it to come back before I try again.

Stomach: I’ve only had coffee so far today, but I’ve been eating a lot big, beautiful salads on account of the hot weather, and plan on having another for lunch. Lately I’ve been making this vegan Caeser dressing, which really does just take five minutes. If I don’t have hummus on hand, I just use chickpeas, or some other canned white bean. Red cabbage and some greens or herbs (arugula or cilantro or dill, usually), carrots, cherry tomatoes, and pepitas or peanuts or walnuts if they’re handy. Since I didn’t eat breakfast today, I’ll probably throw some grilled tofu in there for protein.

Ass: I used to run. Now that I’ve accepted that it’s pretty bad for you—especially if you’ve been doing it for one hundred years, like I have—I’ve replaced it with yoga and calisthenics. Years ago, I read an interview with Dita Von Teese, who said her exercise routine was walking and jumping on a trampoline, and that’s kind of my vibe these days, tbh. That being said, though having a boy butt is endlessly pleasing to me, I’ve been trying to juice it up with squats. There’s no need for another essay on the pressures to be “fit,” in particular for people on the transmasculine side of things, but I no longer feel as if I must be buff or shredded to be okay. I don’t think we should look to cis people to feel at home in our bodies, but I don’t think we shouldn’t, either, if that makes sense; my working definition of gender is that it is the people you want to be like, and the gender I want to be includes both cis and trans people. I notice fem cis gay men whose proportions and muscle/fat distributions are similar to mine, thanks to testosterone, and that makes me feel good. I lost my entire family (other than three of my siblings) and blew up my life to look like a soyboy—and I fucking like it!

Feet: No body is symmetrical, but my right foot is significantly bigger than my left, which means buying shoes is a total bitch. All my digits are uncommonly long, which means my fingers have an elegant, Rachmaninovian wingspan, but it also means that my toes are freakish in length (you win some, you lose some), another annoying consideration. I’ve been wondering if I should just bite the bullet and become one of those people who buys their shoes in different sizes, but I just can’t bring myself to do it yet. Maybe someday.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of the fundraisers featured on Gaza Funds.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1I was raised Evangelical, so chiropractic was a big part of my life growing up. Don’t worry, I know it’s hooey.

June 23, 2024

David Davis 46, part 9

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, and Part 8.

As leathersexuals, nonverbal communication is one of our legacies. Like other subcultures, leather and its littermate, queerness—both formulations that predate postwar America, but hit their modern strides in the decades following WWII—have relied upon this kind of discretion for many years. Hankies, uniforms, materials (like leather), and other high signs were technologies of safety, and not just on the street: communication when words are not available, or even possible, is highly normalized in leather, particularly during scenes1.

Nevertheless, most of us rely heavily on verbal communication to get the job done. Prior to playing, we negotiate with our words to identify when we have consent and when we don’t, a practice that protects us, our play partners, and our community. Because I don’t want to smother, drown, or find myself chained to the bed when the apartment catches fire, my SDATs and I talk about how we can both get what we want out of our scene while minimizing the risks our desires present to all involved (and even to those who aren’t).

I know many players who seem to be able to speak about what they want with ease. While I don’t share this ease, I do think it lends itself to the act of bottoming, the role often interpreted and textured as wanting [more], needing [correction], or requiring [discipline]. It’s our bodies, after all, that are being used, experimented on, and even transformed, and our active participation in that is normalized erotically and practically. While I know many SDATs who have no problem speaking about what they want to do to their bottoms, I have noticed that the proposition of speaking about what they want done to or for themselves can be challenging for some of them.

While I’ll be focusing on SDATs for the purposes of this post, whether top, bottom, or switch, many of us share this aversion to admitting: I want this. I aspire to that. I crave the other. This is no moral failing, but it can complicate things, and complications at our level of play can often open us up to risk. Not just risk of harm, but of dissatisfaction. We flout norms, laws, decency, and even safety to do what we do—shouldn’t we at least be getting what we want in the process?

I mentioned above that verbal negotiation is how we, as leathersexuals, commonly give and gain consent for play—how we as a community exercise our own agency without violating that of other people. In Sexuality Beyond Consent: Risk, Race, Traumatophilia, Avgi Saketopoulou makes a provocative case for a new way of understanding and approaching this process2. Affirmative consent (also known as enthusiastic consent), writes Saketopoulou, “understands consent as issuing from a subject who is fully transparent to themselves and who, in thinking consciously and deciding rationally, can anticipate the probable effects of their consent.” We engage with affirmative consent with the goal of “fostering mutually satisfying experiences in adult sexual encounters.” For example: during our sober, undistracted, power-neutral negotiation, I grant consent to my SDAT to beat me with a cane until I cry, with the expectation that we both come away from the egalitarian experience with some degree of satisfaction.

But as Saketopoulou points out, “One never knows what one signs up for and what one will get until after the fact, however carefully, dutifully, or earnestly one communicates.” Viewed in this way, affirmative consent is a kind of wishful thinking: the idea that we can guarantee the future by virtue of knowing our desires in the present. She proposes an alternative with what she calls “limit consent,”3 which does not “center on (re)producing an experience of satisfaction but, instead, works to facilitate novelty and surprise.” Limit consent does not presume to know how we will leave any encounter or experience; rather, it “hinges on not respecting limits but on their ethical transgression.” And what is consensual sadomasochism but the ethical transgression of limits? What if we are looking for something more interesting than the assurance of satisfaction? What if we are willing to acknowledge that power exchange between equals does not exist, and attempt it anyway? What if we are looking to take some fucking risks with and for each other?

One of the things I love about Saketopoulou’s limit consent is that it takes into account the risks undertaken by the SDAT in any scenario of power exchange. Readers may already be familiar with my evergreen rant about “where” the power goes during these exchanges. Is it “really” with the SDAT, the person running the fuck (a common misapprehension, especially among those outside the community)? Or is it “really” with the masochist, submissive, or bottom, the person with whom the buck is supposed to stop (the reactionary stance of thoughtless perverts everywhere)? Both make my blood boil. We share the power while fetishizing the unavoidable disparities inherent to our connection! I shriek from the rooftops. Enter limit consent, which “centers, rather, on surrendering to another,” on both sides: on the part of the bottom, who offers up their body and cedes their control, and on the part of the SDAT, too, who not only assumes responsibility for that body, but “allows [themself] to be taken over by an internal force that [they] cannot fully control.” There is risk in controlled suffering, just as there is risk in controlling that suffering. Sketching out a hypothetical rape roleplay scenario, Saketopoulou writes that the top will have to “engage with the rousing of her sadism to let it flow, while also keeping some relative check on it.”

I’m not recommending throwing away the baby with the bathwater by dropping negotiation as we know it, but rather augmenting your process with deeper consideration of what you want, what outcomes might be acceptable, and what could be gained from a more holistic conception of risk. In any case, Saketopoulou’s recognition of the “complex,” rather than “dichotomous,” distribution of power and responsibility in any dynamic resonated with me tremendously. And while I don’t know for sure, I suspect she would agree with me that safer play happens because all parties work toward it by building intimacy in and out of scene, something which only happens when we are both brave enough to be vulnerable and wise enough to be aware that true vulnerability requires the support of our lovers, friends, play partners, and community.

Back to our SDATs. As I wrote last time, safer sadists, dominants, and tops talk about what they want. Why does this matter? To answer this question, we’ll first need to interrogate wanting, starting with this: why would anyone conceal their desires, especially within leather, with our watchwords of fantasy and freedom and fuck?

Desire is inextricable not only from the unrealized, and even the unimagined, but from that which is excruciatingly known. In permitting us to indulge in what we don’t or shouldn’t want, leather shows us, with great tenderness, that we can never hide from what we do want. I’m a germaphobe who licks dirty boots. I’m a prude who wants to get fucked. I’m a masochist who is terrified of pain. Admitting my desires reveals my weaknesses, shortcomings, fears, failures, and needs4. (I have found it helpful to conceive of desire as a field of preoccupations, including things that I both do and don’t want.) As much as they’d like to think of themselves as vampires, SDATs aren’t immune to this mirror: they, too, have a reflection.

What do you want? I feel a deep empathy for anyone who, when confronted with this simple question, responds with irritability, confusion, anger, numbness, or nothing; whose first instinct is to turn away, fight, change the subject, or cause a distraction. To admit what you want is to expose yourself, which is to say that it builds intimacy with a receptive audience: it is worthwhile, but challenging, especially if you’re not in the habit of doing it because of your upbringing, trauma history, or lack of experience, in that you haven’t yet learned that the benefits of connection far outweigh the risks.

I don’t know that concealing desire is easier for SDATs than for anyone else in leather, but those of us in community know that SDATs are often caretakers in and outside of scene, accustomed to and skilled at putting others before themselves, sometimes to their own detriment. At its best, leather corrects for this by creating an alternative infrastructure for vulnerability—a means to give and to accept care that may not be readily apparent to outsiders. Service bottoms provide their tops with a safer framework for accepting help; pain sluts allow their sadists to exercise (and exorcise) genuine feelings otherwise repressed for the happiness, safety, and agency of others; fetishists of dehumanization offer their dominants new opportunities for connection when eye contact, physical touch, or “normal” sex are unpleasant or even impossible.

Little story for you: an elder femdom friend of mine used to go off when people at play parties would degrade or harm her submissives without first asking for their permission, let alone hers5. Their violation of etiquette betrayed an entitled ignorance of what we’re all doing here, which she corrected immediately and without mercy6. “I treasure my subs,” the femdom would tell the rube in question, towering in her heels. “I am here to protect their happiness and safety.” Even if parenting, nurturing, or “care” is not part of the dynamic, SDATs assume a sacred responsibility for their bottoms, even if it’s just for the space of a scene, no matter how challenging the activity or cruel the pageantry.

Unfortunately, not every SDAT is like my femdom friend. Some hide behind our shared fetishes for violence and degradation, perverting perversion to express a very real malevolence or disregard for other people; one of these assholes is why I started writing this series in the first place. Others—more common, in my experience—hide behind their own propensity for caretaking: my bottoms have needs, not me. If I fulfill those needs, then I have fulfilled my responsibility as a top. They abandon themselves in leather as they were trained to do in their vanilla relationships, a tragic turn of events that all too many of us can relate to on some level.

If we’re not intentional in how we build our leather communities, we enable SDATs who harm others or themselves in these ways and others. But this is not inevitable! My advice to you, as I end the final post of this long series, is to add this question to your vetting toolkit, one you can utilize throughout your relationships, and not just at the beginning: Is your SDAT using play to connect with you, or using you to dissociate from themself?

I can’t believe this series is done! Thank you for joining me on this journey. Many of the other posts are locked, so I’ll remind you that I’ll give you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of the fundraisers featured on Gaza Funds.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1I don’t personally know any leatherfolk who are Deaf, have mutism, or don’t speak for other reasons. If anyone has any articles or books to share about these experiences (written by those who experience them), I’d love for you to send them my way.

2Yes, I know I keep mentioning this book!

3Saketopoulou calls it “limit consent” because, “unlike affirmative consent, [it] is predicated not on setting and observing limits but on…initiating—and…responding to—an invitation to transgress them.”

4Isn’t it interesting that I include needs in this list of negatives without a second thought?

5Obviously they were usually straight.

6“Kinky” and “in leather” are not synonyms! My culture is not your costume, Mary!

June 9, 2024

David Davis

My life as a fan began with Will Smith, the first non-cartoon celebrity I was conscious of. His early-nineties breakout, Fresh Prince, was perfect TV for a young child: sitcom-silly, family-friendly, and a little surreal for a 5-year-old, in the sense that the goofy, ebullient, and handsome Smith shared his name with his character (though the character’s Christian name was William, not Willard). When a teacher prompted my class to name a town other than our own, my hand shot up. “Bel-Air!” I didn’t know that Uncle Phil and Aunt Viv’s mansion was actually located in a neighborhood, in one of the biggest cities in the world.

Smith’s rise was, as they say, meteoric, with his music and movie careers swiftly gaining steam throughout the decade, much of it in similarly child- and family-friendly projects, from his starring turn in Men in Black (1997) to his debut solo album, Big Willie Style, that same year1. Though he’d already been a lead, along with Martin Lawrence, in Bad Boys (1995) and in the ensemble alien shoot-em-up, Independence Day (1996), he made his transition to serious leading man fare with Enemy of the State (1998), a movie that I joke was one of the first to radicalize me2.

In Enemy of the State, Smith plays Robert Clayton Dean, a labor lawyer who comes into unwitting possession of proof of a murder by an NSA operative greasing the wheels on Patriot Act-style “counterterrorism” legislation3. Dean’s life is summarily destroyed: his bank accounts are frozen and he’s framed as a cheater (his wife, played by Regina King, throws him out) and a money launderer, causing him to lose his job as well as his home. When he finally figures out what’s going on with the help of Brill (Gene Hackman), a rogue NSA comms expert, the situation only gets worse: the NSA murders one of Brill’s contacts and pins that on Dean, too.

A lot of stuff happens after that, but (spoiler alert), with the help of Brill, Dean finally exposes the conspiracy and clears his name (although the NSA is able to conceal its role in the snafu). The counterterrorism bill is scrapped, Dean reconciles with his wife, and Brill sends his regards from his retirement on a tropical island. All’s well that ends well, unless the government decides to come after Dean (or anyone else) ever again.

It’s probably for this reason that the “happy ending” of Enemy didn’t stick with me. What I do remember is Dean’s horrified realization that his bank accounts aren’t his anymore, that his wife hates him, that anything bearing his name—from his birth certificate to his driver’s license—is an implication, not a guarantor of his rights as an American citizen4.

As an adult, I’ve had the pleasure of seeing Gene Hackman5 in a role considered by some to be the origin of the Enemy universe: Harry, the “soul-sick, uneasy” surveillance expert of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974). Though his tough-guy mein makes him a great republican congressman (The Bird Cage [1996]), hard-nosed military man (Crimson Tide [1995]), or sleazy confidence man (The French Connection [1971]), Hackman is also capable of a professional disquiet that puts him at a compelling remove from his ordained authority; sanctioned yet straddling criminality, he’s shines in doubtful roles, like the queasy PI (Night Moves [1975]), or, in the case of Harry, the paranoid wiretapper.

One star in a constellation of New Hollywood’s paranoid cinema—Klute (1971), The Parallax View (1974), and All the President’s Men (1976) among them—The Conversation scratched an itch first initiated by its descendent, with its mistrust in and cynicism regarding institutions (particularly the government), all equipped with technology that not only allows them to eavesdrop on me with impunity, but to infiltrate, and even eliminate, my connection to other people. As Dean, Smith’s profound vulnerability, perhaps best encapsulated by the nightmare-like image of him running through rush-hour traffic in his open bathrobe, was a wake-up call to a younger version of myself, one for whom the reasons for being unable to access, for example, one’s bank account were still divided into fair and unfair.

Enemy isn’t why I’m a paranoid person, but I think about it more than I should because I’m a paranoid person, of which I was reminded after spending this past week in isolation when someone I love got COVID. An obsessive-compulsive germaphobe can get in their head about these things, and not just for their own sake; if the wind’s blowing in the right direction, I can decide that Jade is dying or dead ten times in a single hour. Given a chance to stew, the paranoia soon becomes despair, descending like a cloud of toxic pollen over my jellied brain. What’s the point, of anything? This risk is too much. Everything is too much. Everything is doomed. Why live? Why write?

When done well, paranoid cinema makes you feel as if your world has been shrunk to the size of a microchip. But if we travel back up the cylinder, the tube, the wire; back through Al Pacino’s mic in Serpico (1973) and John Travolta’s boom in Blow Out (1981); back out of whatever machine of surveillance we’re inside, we find ourselves in the moviehouse itself. Do you ever feel surrounded by art, but unable to see the project? Perhaps a reparative reading of paranoid cinema requires an expansion into other genres and histories, a look at the big picture—or multiplex, as it were.

Which brings me to something written this week by Maya Cade. Film-lovers should be paying attention to Cade’s work with the Black Film Archive generally, but this week she published a meditation on “the role the artist in Black cinema, life, and Palestine” that I think everyone should read. As Maya writes:

Artmaking, as Toni Cade Bambara said clearly, has been put in bondage to an industry that demands artists' silence in exchange for the will to continue practicing freely. The task ahead of us—filmmakers, writers, spectators, painters, cultural workers, and everyone in between—is to have the courage to act. We must ask ourselves: is our artmaking, our lives, our creative practice dedicated to justice or what is right for only us as an individual?

This piece is a reminder that art, as one of the highest expressions of humanity, is for serving people. I needed it this week, and am sharing it here because I feel certain that others do, too.

Gaza Funds aggregates fundraisers for people fleeing the violence of the Zionist entity, so if you’re looking to share some cash, please do. If you donate to any of the fundraisers featured there, send me a screenshot for a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram if you’re nasty.

1To say Big Willie Style was more child- and family-friendly because of Smith’s refusal to use profanity while rapping is to capitulate to my white mom’s racist assumptions about what constituted “child- and family-friendly” music, rap or otherwise (the only other rap my mom would listen to was Eminem. Great stuff for a gay kid to hear their mom sing along to, but hey, he was white!). But I think it’s also safe to say that this was a function of Smith’s sanitized image, key to attaining his stated goal of becoming “the biggest movie star in the world,” which he pretty much crushed.

2Michael Mann’s Ali (2001), one of the only Manns I haven’t seen because I don’t go for biopics, was when Smith got his Best Acting Oscar.

3Released a little under three years before 9/11, Enemy of the State has since been acknowledged for anticipating the repressive surveillance expansion authored by the Bush administration.

4It goes without saying that these supposed rights are not assured for any citizen, something that Dean is already aware of as a Black man and labor lawyer.

5Goin’ strong at 94, baby. Jade is always like, Why do you think THAT man is hot? And it’s true that I’m drawn to the cornfed linebacker daddy thing. But it’s also a certain soulfulness that’s best on display when he’s playing a character doing his damnedest to repress it.

June 4, 2024

David Davis 46, part 8

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, and Part 7.

He was looking at me. Leaving the laughter and the red cups, I followed him into an empty bedroom—I don’t think it was his—where for a long time, including the five seconds he spent removing and halving his brown leather belt, he held me down, fucked me, and beat me, all without saying a word.

As we slid back into our clothes, I became aware of the party again, still humming on the other side of the door. We finally spoke, but I don’t remember what we said. If we kissed, I don’t remember that, either. I do remember, very well, knowing that I had fallen in love. But even that sensation, being in love, is gone. Only its certainty has been able to outlast the years between now and then.

June 3, 2024

David Davis

When I was in elementary school, my report cards always came back with the same caveats: smart, but doesn’t speak up/participate/socialize enough. My teachers saw that I preferred to spend my time either reading or with the wrong kids (bad homes, behavioral problems, etc.). The solution was clear: I needed to learn how to win friends and influence people—the right people—if my academic promise wasn’t to be wasted.

Not every teacher regarded my shyness as a problem. Anticipating the kind of women I would gravitate toward as an adult, the motherly, no-nonsense Mrs. Evans would permit me to spend recess under her yard-duty umbrella, blithely tolerating my data-dumping about medieval England. But others were on the hunt for the upwardly mobile extrovert within, like tough-loving Mr. Crandall, who cast me as the lead in the fifth-grade play to scare me out of my stage fright. From leadership programs for at-risk girls to Toastmasters-style speech contests, years of interventions never made a dent in my introversion, let alone the mumbling, shaking, and full-body sweats that still show up at my readings today.

Now in my mid-thirties, I’m still better able to articulate myself on paper than in person. Listening to my recent interview for the NYC Oral History Project, to which I was invited to participate by Jay Graham, I’m exasperated—but not surprised—by my ums and whatevers, my inability to stay on topic, and the limitations of my verbal vocabulary. But I’m also a little pleased to recognize the natural ellipticallity of my reasoning animated by my speech. As I wrote last year, “I speak, which is to say that I circle, with the hope that the person listening has the patience to wait for the final descent, if it’s even worth making; that whatever’s down there is animated by flesh and blood, and not a trick of the sunlight or my own hunger.” I’m not pithy or parsimonious, but I’m learning to appreciate that about myself.

If you’d like to hear me circle about my books, my politics, and leather in Oakland and NYC, you can listen to my interview here. I also recommend checking out other NYCTOHP interviews, including those by the recently departed Cecilia Gentili, the foundational Bryn Kelly, and local leatherman Santos Arce.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

If you have a few dollars to spare, please help the al Baqi family, including baby Sami, escape the Israeli assault on Gaza. “The most important thing is, I don't want to die,” writes Ahmed, Sami’s father. If you do make a donation of any amount, send me a screenshot for a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content.

May 29, 2024

David Davis: Members Only (unlocked)

Will you wait for me here? he asked.

Yes, I said.

He laughed and said goodbye. The front door closed and clicked. For the next hour (though I didn’t know, at the moment, how long my friend would be gone), I tried not to move. If I did, I would be confronted with the limits of my ability, and if so confronted, I would struggle. I didn’t want to struggle, because it’s humiliating, and because I wanted to pretend that I was there of my own volition. Which, I reminded myself, I was.

The air conditioner hummed in the window, but otherwise my friend’s bedroom was silent. I wondered if he hadn’t really left. If he was still there, watching from the doorway. But I soon decided he wasn’t. For one thing, I would have heard him—his shifting weight on the hardwood, a heedless breath. Something. For another, staying here with me wasn’t what he wanted. What he wanted was to go somewhere else, to the park or a nearby bar, and think about me waiting for him naked, hooded, bound hand and foot to the bed frame, and slowly realizing that while Jade knew where I was, I had no way of contacting her if he didn’t come back.

I’ve heard that people in bondage lose time. Maybe I would have myself if sunlight, enough to grey the black vinyl, couldn’t filter through the drawstring of the military-style hood. Or maybe not. I don’t think of myself as into bondage, though I’ve been in close proximity with it for many years. I used to date a dominatrix who specialized in it, with an emphasis on abandonment. Her sleepsacked clients were forsaken in shower stalls overnight, while she slept in a queen bed in the other room. Want to try it? she asked me once. Fuck no. I like attention with my discomfort, thank you very much.

No, I wasn’t enjoying it, what was happening to me. But I was there for reasons other than pleasure. And what were those, exactly? I pushed the question away. In the ten minutes since my friend had left, I had discovered that all speculation led to panic. I began box breathing, intending to do it until I heard the key in the door (When would that be? An hour? Longer?). Since I was lying on my back, the handcuffs had begun slipping down my wrists toward my elbows, a lemniscate of steel digging into my forearms. How long until nerve damage? I pictured my friend ordering a beer, then another, then another, until he forgot all about me.

Stillness, of the body and of the mind, is the greatest challenge. I began doing yoga as preparation for a complete meditation practice without movement, and five years later, I’m nowhere close. Breathing through my nose, I counted to four over and over again, building a new world within the one made by my friend’s dark web torture toys. This, I believed, was the solution to all my fears, which I wanted to transcend. I would hide within the four walls of breath-and-no-breath until he returned.

I wanted. That was the problem, if all suffering is caused by desire. It wasn’t long before my fears infiltrated the counting, the breath, the awareness of my diaphragm. The discomfort from the cuffs reminded me of my hands, which reminded me not of my body, but of everything bad that my body was subject to.

Though I knew my friend was gone, I moved my body as if he wasn’t. Just my fingers and wrists, subtle and sly. I like watching you decide if you’re going to red or not, he told me once. Slowly, slowly; stillness was impossible, but I knew if I moved too much or too fast, I would lose control. With my index finger, I stroked the lock that held the cuffs to the velcro restraint around my waist. The metal was smooth and, I knew without being able to see, shiny. Kind of cute. I imagined that the lock was a locket, which became tattoo on my left pec, like Richard Gere's in Breathless (1983). I thought about putting it in my mouth. My hands could have reached that high, but the lock wouldn’t have gotten under the hood. Moving a little more boldly, I found that I had enough freedom to reach down and touch myself, if I wanted (I didn’t). But that was as far as my hands could go.

Afterward, I told my friend that I thought about him the entire time he was gone, but that wasn’t true. Though powerfully shaped by his absence, my thoughts were almost entirely self-centered. The risk I was taking; the discomfort I was feeling; the panic hovering in my solar plexus, still bruised purple by his knuckles. I yearned for other circumstances, not ones in which I was free, but in which my restrictions were more tolerable1. What if I hadn’t been wearing the hood? I would feel less calm, I suspected, but also less powerless. What if my friend were standing outside the building, or even at the bottom of the stairs, absent but nearby? I desperately wanted this to be true, but every time I forced myself to see the fantasy for what it was, my breath became hotter and louder on the inside of the hood, the drawstring tighter around my throat, my ankles more firmly secured.

As I write, I can’t feel that fear anymore; it’s as if someone else was in that hood, those chains. But while in the moment it was inescapable—by design, of course—I also found it impossible to believe. Every nightmare provoked another, every attempt to regain control surfacing a horrifying new way to suffer. In attempting to think my way out of my fear, to manufacture reasons why it wasn’t really happening the way it was, it grew heavier, more ingenious. How long would he make me sweat it out? When would I know that it was time to panic, that he wasn’t coming back? Four hours? More? And what did panic mean? Was it any different from what I was doing right now?

Through the slit below my chin, I noticed that the sunlight had begun to fail. How long before I pissed myself? How long before I felt the torture of thirst? Of course, all of that would only possibly happen if something tragic befell my friend, like a car accident. I imagined him standing on the sidewalk in front of his apartment, unable to enter because of a police barricade or clouds of smoke. How selfish I am, I thought, worrying about his misfortune, not for his own sake, but for mine.

Fearful, uncomfortable, resentful, ashamed, helpless. A brutal caning, with my friend’s warm body touching mine, talking to me and kissing me while he hurt me, was heaven in comparison. Why was I doing this? I was all alone. No one cared about me. I was nothing. If he came back, I was never doing this again.

And I really believed that, before I heard the key in the lock.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1As if I had a choice but to tolerate them.

May 24, 2024

David Davis 46, part 7 ½

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, and Part 7.

Though I’ll soon be attending a local screening of Hellraiser (1987), the first film in the franchise based on Clive Barker’s The Hellbound Heart, the series is one I mostly enjoy in theory1. I’m squeamish in the cinema, and B-ish horror tends to disturb me far more than the higher-production stuff, retaining as it does the scrappy anti-authoritarianism that defines the best of the genre. Though I’ve seen Hellraiser before, there’s a strong chance I will still cover my eyes as Barker’s Cenobites, the S&M-inspired beings who transcend sensation and dimension, pursue the pleasures of eternal torture.

It will come as no surprise that the Cenobites were inspired by Barker’s visits to 1970s S&M clubs, which were aesthetic and “emotional” inspirations, as the writer relays:

There was an underground club called Cellblock 28 in New York that had a very hard S&M night. No drink, no drugs, they played it very straight. It was the first time I ever saw people pierced for fun. It was the first time I saw blood spilt. The austere atmosphere definitely informed Pinhead: “No tears, please. It’s a waste of good suffering!” 2

I invoke the dreadful Order of the Gash for a reason. In warning you away from the sadists, dominants, and tops who prioritize the “optimization” of skill and technique over safer, more connected play, I see the Cenobites as inspiration for us all: they’re doing it for the love of the game, and isn’t that the spirit of leather? These sexualized yet sexless adrenaline freaks have been playing for so long that they no longer differentiate between pain and pleasure (let alone consent and violation3). There’s no profit-driven perversion of “health,” “community,” or “intimacy” here, just good, clean fun!

While last time I wrote that the SDATs that you and I are after aren’t optimizers, I’d like to expand the premise of this post so we can talk about what they do instead: safer sadists, dominants, and tops don’t optimize. They do build skill individually and collectively out of a desire to engage in more risk-aware and pleasurable play.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 55 followers